Abstract

Selected dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates were prepared by carbo-bromination of alkyl azulenemonocarboxylates and subsequent alcoholysis or by alkoxycarbonylcarbene insertion of ethyl indane-2-carboxylate. The electrochemical behavior of the diesters was studied by means of differential pulse polarography and cyclovoltammetry. In-situ electroreduction of the azulenedicarboxylic esters led to the corresponding radical anions, the EPR spectra of which were recorded. For certain radical anions a rearrangement under migration of the functional group from the 5- into the 6-position was observed. The spin density distribution in these non-alternant π-electron systems as determined from the proton hyperfine structure (hfs) coupling constants was compared with the results of MO calculations and discussed with respect to the influence of substituents.

1 Introduction

Recently, we described the EPR spectra of alkyl azulenecarboxylate radical anions [1]. Our aim was to compare the spin density distribution in these non-alternant π-electron systems with their alternant counterparts, the alkyl naphthalenecarboxylate radical anions [2]. In particular, we were interested in the changes which would occur after an electronic disturbance by substitution with electron-withdrawing ester groups in certain positions. Radical ions of arenes with a non-alternating π-electron system exhibit very different spin density distributions as compared with the alternating isomers because the pairing theorem is not valid for these systems [3] which has been clearly demonstrated experimentally by Gerson’s group for the EPR spectra of azulene and alkylazulene radical anions [4] and radical cations [5].

We now present the results of new EPR spectroscopic measurements and MO calculations on azulenedicarboxylic diester radical anions which we have performed in order to study the interactions of two electron-withdrawing substituents with each other and with the azulene skeleton.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Preparations

In order to facilitate the interpretation of the EPR spectra and the assignment of the proton hyperfine structure (hfs) coupling constants to specific positions in the azulene system and in the side chain, we prepared tert-butyl azulenedicarboxylates possibly with additional tert-butyl substituents in the ring, besides the corresponding ethyl esters.

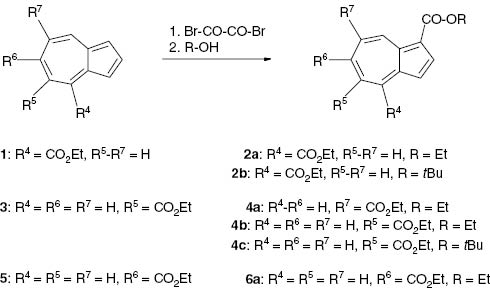

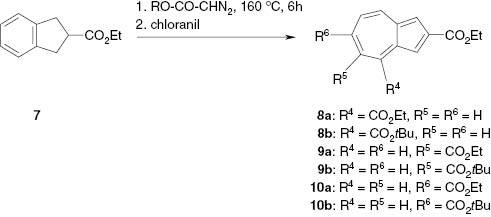

Mainly the two methods which we had used previously [1] were also applied for the preparation of the dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates, i.e., carbo-bromination of the monoesters 1, 3 and 5 with subsequent direct alcoholysis [6] (Scheme 1), and ring enlargement (alkoxycarbonylcarbene insertion) of ethyl indole-2-carboxylate (7) [1] with alkyl diazoacetates [7] (Scheme 2).

Preparation of dialkyl azulene-1,x-dicarboxylates by carbo-bromination.

Preparation of dialkyl azulene-2,x-dicarboxylates by ring enlargement.

Carbo-bromination of the monoesters expectedly occurred in the electron-rich 1- or 3-position of the unsubstituted five-membered ring. Thus, we obtained dialkyl azulene-1,4-dicarboxylates (2) from ethyl azulene-4-carboxylate (1). Starting with ethyl azulene-5-carboxylate (3) gave diethyl azulene-1,7-dicarboxylate (4a), diethyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4b) and the mixed dialkyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4c). Starting with ethyl azulene-6-carboxylate (5) led to diethyl azulene-1,6-dicarboxylate (6a) (Scheme 1).

The structure of the products was proved by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. Diethyl azulene-1,4-dicarboxylate (2a) exhibited a pronounced down-field shift of the signal at δ = 9.75 ppm for 8-H (d, 3J = 9.7 Hz), which compares with δ = 9.64 ppm for 8-H of ethyl azulene-1-carboxylate [1] but cannot be assigned to any proton of the isomeric azulene-1,8-dicarboxylate ester. Apparently, due to steric hindrance neither dialkyl azulene-1,8-dicarboxylates nor 1-tert-butyl 7-ethyl azulene-1,7-dicarboxylate were formed from the corresponding starting esters 1 and 3.

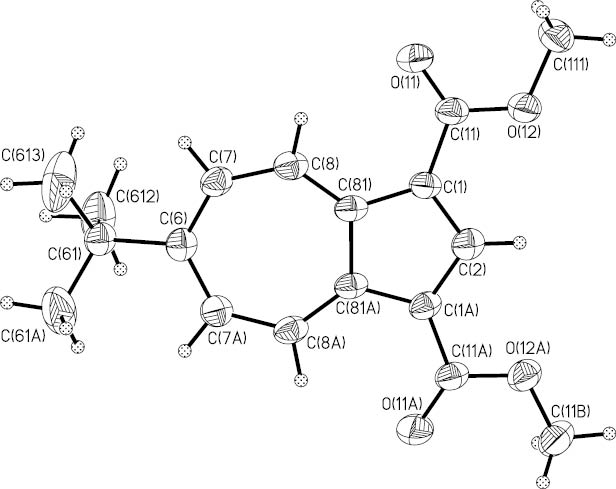

Separation of the isomers 4a and 4b, which were produced as a mixture, was achieved by column chromatography. The pure isomers could be discriminated on account of the splitting pattern of their 1H signals. The shielding effect of each ethoxycarbonyl group causes down-field shifts to δ = 9.24 ppm for 4-H (d, 4J = 1.5 Hz) and δ = 9.63 ppm for 8-H (d, 3J = 10.2 Hz) in 4b whereas the 8-H signal (d, 4J = 1.6 Hz) of 4a is extremely shifted to δ = 10.42 ppm due to the two neighboring ethoxycarbonyl groups in the 1- and the 7-position. The structure of 4a was also corroborated by an X-ray structure analysis (Fig. 1). Selected bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles of 4a are compiled in Table 1.

Ortep-style plot of diethyl azulene-1,7-dicarboxylate (4a). Non-H atoms are drawn as spheres with radii relative to their Uequiv values, H atoms as spheres with arbitrary radii.

Selected bond lengths (Å), angles (deg) and dihedral angles (deg) for 4a and 12b with estimated standard deviations in parentheses.

| 4a | 12b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond lengths | Bond lengths | ||

| C1–C2 | 1.402(4) | C1–C2 | 1.389(5) |

| C2–C3 | 1.372(4) | ||

| C3–C3A | 1.404(4) | ||

| C3A–C4 | 1.375(6) | ||

| C4–C5 | 1.383(5) | ||

| C5–C6 | 1.383(4) | ||

| C6–C7 | 1.388(4) | C6–C7 | 1.394(6) |

| C7–C8 | 1.464(4) | C7–C8 | 1.402(5) |

| C8–C8A | 1.378(5) | C8–C81 | 1.379(5) |

| C1–C8A | 1.396(4) | C1–C81 | 1.423(5) |

| C3A–C8A | 1.491(6) | C81–C81A | 1.467(7) |

| C1–C11 | 1.469(3) | C1–C11 | 1.464(5) |

| C11–O1 | 1.206(3) | C11–O11 | 1.215(5) |

| C11–O2 | 1.342(3) | C11–O12 | 1.338(5) |

| C7–C71 | 1.482(3) | C6–C61 | 1.542(7) |

| C71–O3 | 1.204(3) | ||

| C71–O4 | 1.339(3) | ||

| Bond angles | Bond angles | ||

| C1–C2–C3 | 115.01(24) | C1–C2–C1A | 110.5(5) |

| C2–C1–C8A | 103.69(26) | C2–C1–C81 | 108.0(2) |

| C2–C3–C3A | 105.99(28) | ||

| C3A–C4–C5 | 129.82(46) | ||

| C4–C5–C6 | 131.56(30) | ||

| C5–C6–C7 | 125.60(25) | C7–C6–C7A | 123.8(5) |

| C6–C7–C8 | 131.31(26) | C6–C7–C8 | 131.4(4) |

| C7–C8–C8A | 126.77(36) | C7–C8–C81 | 129.3(4) |

| C1–C8A–C3A | 109.16(30) | C1–C81–C81A | 106.7(2) |

| C3–C3A–C8A | 106.14(30) | ||

| C3A–C8A–C8 | 127.71(33) | C8–C81–C81A | 126.7(2) |

| C4–C3A–C8A | 127.21(40) | ||

| Dihedral angles | Dihedral angles | ||

| O1–C11–C1–C2 | 2.2(2) | O11–C11–C1–C81 | 2.0(7) |

| O3–C71–C7–C5 | 3.2(2) | ||

| C61A–C61–C6–C7 | 87.9(4) | ||

Insertion of alkoxycarbonylcarbenes into different bonds of the benzene ring of ethyl indane-2-carboxylate (7) led to mixtures of the regioisomers 8, 9 and 10 (Scheme 2), which could be separated by column chromatography and characterized by NMR spectroscopy.

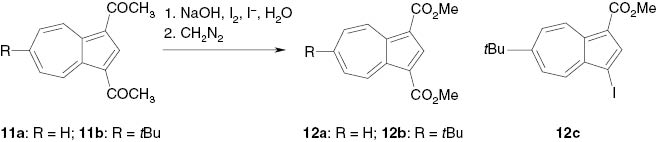

Dimethyl azulene-1,3-dicarboxylate (12a) [8] and its 6-tert-butyl derivative 12b were obtained via cleavage of the acetyl groups of the 1,3-diacetylazulenes 11a and 11b by in-situ-generated sodium hypoiodite accompanied by iodoform extrusion and subsequent methylation with diazomethane (Scheme 3). A small amount of methyl 6-tert-butyl-3-iodoazulene-1-carboxylate (12c) was formed as by-product.

Preparation of dimethyl azulene-1,3-carboxylates by iodoform splitting.

The ester 12b crystallized in beautiful red needles which were suitable for an X-ray structure analysis. The Ortep plot (Fig. 2) demonstrates the high symmetry of this molecule with a perpendicular crystallographic mirror plane through C2 and C6. Selected bond lengths, bond angles and dihedral angles are compiled in Table 1.

Ortep plot of dimethyl 6-tert-butylazulene-1,3-dicarboxylate (12b). Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50 % probability level, H atoms as spheres with arbitrary radii. The atoms are numbered according to the symmetry of the molecule and do not agree with the IUPAC rules which are applied for 12b in the text.

The perimeter bond lengths of the two esters 4a and 12b show only minor alternation except the bonds next to the ester substituents which are slightly longer [4a: d(C7–C8) = 1.464(4) Å; 12b: d(C1–C81) = 1.423(5) Å]. Also, the central C–C bonds exhibit the typical elongation (4a: d(C3A–C8A) = 1.491(6) Å; 12b: d(C81–C81A) = 1.467(7) Å); see Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2. This is in agreement with the structures of azulene itself (1) [9, 10] and related derivatives such as 6-tert-butyl 2-ethyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate, the isomer of 10b, [11, 12], azulene-1,3- and -5,7-dicarboxamides [13, 14], and -5,7-dicarbothioamides [13, 14]. The planes of the ester groups of 4a and 12b are nearly coplanar with the azulene ring plane (see Table 1) just as in the isomer 10b [12] but contrary to the significant torsion angles in N,N’-dibutyl-azulene-1,3-dicarboxamide (21°/35.7°) [13], N,N’-dibutyl-azulene-5,7-dicarboxamide (34.9°/30.3°) [13, 14] and N,N′-dibutyl-azulene-5,7-dicarbothioamide (−148.8°/−138.1°) [13, 14].

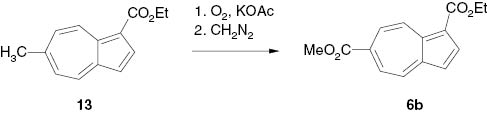

Reaction of ethyl 6-methylazulene-1-carboxylate (7) with oxygen in the presence of potassium acetate and subsequent methylation with diazomethane [15] yielded the mixed diester 1-ethyl 6-methyl azulene-1,6-dicarboxylate (6b) (Scheme 4).

Preparation of 1-ethyl 6-methyl azulene-1,6-dicarboxylate by air oxidation.

2.2 Electroanalytical results

Reduction potentials Ered of the diesters (Table 2) in aprotic medium (dry DMF) were measured by use of the differential pulse polarographic (DPP) method [16, 17]. The peaks with the lowest cathodic reduction potential Ered(1) are assigned to a single electron transfer (SET) step, i.e. the formation of a radical anion. Thus it is most important in view of the EPR measurements. Another reduction peak Ered(2) at a more negative reduction potential (see Table 2) is observed if one ester substituent is located in the seven-membered ring of the azulene moiety. It can be assigned to the formation of a diamagnetic dianion. Most dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates exhibit a third peak Ered(3) at even more shifted potentials (see Table 2) which should be due to the formation of a radical trianion. We have not studied these latter sensitive species by EPR spectroscopy.

Polarographic reduction potentials Ered (V) [16, 17] and cyclovoltammetric peak current ratios ipa/ipca of alkyl azulenecarboxylates [1] and dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates.

| Compound | Ered(1) | Ered(2) | Ered(3) | ipa/ipc(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | −0.73 | −1.70 | 0.45 | |

| c | −0.68 | −1.54 | 0.62 | |

| 1 | −0.54 | −1.25 | 0.93 | |

| 3 | −0.79 | −1.78 | 0.70 | |

| 5 | −0.69 | −1.40 | 1.00 | |

| 12a | −0.51 | − | 0.40 | |

| 12b | −0.63 | − | 0.73 | |

| 4b | −0.68 | −1.54 | −2.09 | 0.37 |

| 4c | −0.73 | −1.53 | −2.13 | 0.38 |

| 4a | −0.72 | −2.11 | −2.31 | 0.07 |

| 8a | −0.37 | −1.08 | −2.11 | 1.00 |

| 9a | −0.38 | −1.10 | −2.09 | 1.20 |

| 9b | −0.58 | −2.24 | 0.35 | |

| 10a | −0.27 | −0.79 | −2.00 | 0.96 |

aipa/ipc represents the current of the anodic (i.e., the oxidation) peak divided by the current of the cathodic (i.e., the reduction) peak; bethyl azulene-1-carboxylate [1]; cethyl azulene-2-carboxylate [1].

The reduction potentials Ered of the first SET of the diesters are less negative by 10–30 mV than those of related azulenemonoesters (see Table 2); compare, e.g., diethyl azulene-1,3-dicarboxylate (12a, Ered = –0.51 V) with ethyl azulene-1-carboxylate (Ered = –0.73 [1]); diethyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4b) (Ered = –0.68 V) with ethyl azulene-5-carboxylate (3, Ered = –0.79 V [1]) or diethyl azulene-2,4-dicarboxylate (8a, Ered = –0.37 V) with ethyl azulene-2-carboxylate (Ered = –0.68 V [1]). Diethyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate (10a) exhibits the least negative half-wave reduction potential of all compounds studied for the first SET [Ered(1) = −0.27 V] and even for the second SET [Ered(2) = −0.79 V]. This may be due to the high symmetry of 10a and the longest distance between the two ester groups and hence the best separation of the negative charges in the anions of all isomeric azulenedicarboxylate esters. This effect, which is also observed for dimethyl naphthalene-2,6-dicarboxylate [2], is illustrated by the resonance formulae in Scheme 5.

Resonance formulae of dialkyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate and naphthalene-2,6-dicarboxylate, and their anions.

Inspection of Table 2 reveals that the reduction potentials Ered of azulenes with ester substituents in the 2,4- (8a), 2,5-, (9a) and 2,6-position (10a) are significantly less negative than those of derivatives with ester substituents in the 1,3- (12a), 1,5- (21b), and 1,7-position (21a). This thermodynamic effect does not mean that the corresponding radical anions are more persistent. Cyclovoltammetric measurements showed, that the radical anions formed at the first SET step in most cases should be stable enough to allow EPR spectra to be recorded successfully after in-situ electroreduction, since peak current ratios of ipa/ipc(1) ≥ 0.4 (Table 2) are observed. But there are deviations from that rule. For example, 12a·– with ipa/ipc(1) = 0.40 could not be detected by EPR spectroscopy. The corresponding 6-tert-butyl derivative 12b·–, on the other hand, with ipa/ipc(1) = 0.73 is obviously stabilized because the bulky substituent inhibits decomposition reactions via the high-spin-density 6-position. Hence, its EPR spectrum can be observed although the SET reduction potential is more negative. Unexpectedly and inexplicably, an EPR spectrum of 21a·– was obtained although its ipa/ipc(1) is only 0.07 (see below).

2.3 Electron paramagnetic resonance results

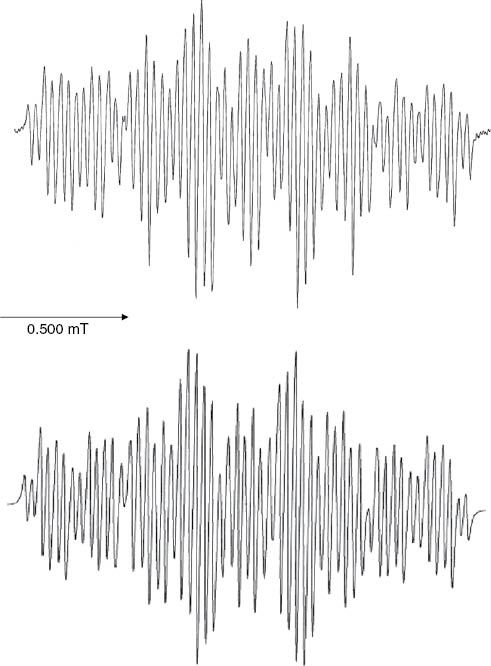

Radical anions of the diesters were generated by internal electroreduction as previously described [1] for the monoesters. In most cases the recorded EPR spectra exhibit large numbers of lines (see Figs. 3 and 4), since the symmetry of the azulene derivatives is low. Nevertheless, valid sets of proton hfs coupling constants aH could be determined by simulation of the spectra. The EPR spectroscopic data obtained for the dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates are compiled in Table 3.

Experimental (top) and simulated (bottom) EPR spectra of the diethyl azulene-1,4-dicarboxylate radical anion (2a·–).

Experimental EPR spectra observed after in-situ electroreduction of diethyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4b, top), diethyl azulene-1,6-dicarboxylate (6a, middle), and simulated EPR spectrum (bottom) as calculated with the proton hfs coupling constants of 6a·–: aH2 = 0.407 mT, aH3 = 0.063 mT, aH4 = 0.413 mT, aH5 = 0.030 mT, aH8 = 0.472 mT, aHOCH2 = 0.059 mT (2 H), see Table 3.

EPR-spectroscopic proton hfs coupling constants aHμ (mT) of dialkyl azulenedicarboxylate radical anions.

| Radical anion | aH1 | aH2 | aH3 | aH4 | aH5 | aH6 | aH7 | aH8 | aHOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12b·– | – | 0.401 | – | 0.684 | 0.171 | 0.020a | 0.171 | 0.684 | b |

| 2a·– | – | 0.342 | 0.185 | – | 0.028 | 0.587 | 0.062 | 0.380 | 0.059c |

| 2b·– | – | 0.345 | 0.181 | – | 0.028 | 0.586 | 0.073 | 0.367 | 0.061c |

| 6a·– | – | 0.407 | 0.063 | 0.413 | 0.030 | – | b | 0.472 | 0.059c |

| 6b·– | – | 0.410 | 0.063 | 0.413 | 0.030 | – | b | 0.472 | 0.066d |

| 6c·– e | − | 0.420 | 0.059 | 0.420 | 0.025 | − | b | 0.471 | 0.059c |

| 4a·– | – | 0.207 | 0.266 | 0.974 | b | 0.876 | – | 0.343 | b |

| 8a·– | 0.034 | – | 0.030 | – | 0.199 | 0.683 | 0.028 | 0.415 | 0.030c 0.060c |

| 8b·– | 0.034 | – | 0.030 | – | 0.199 | 0.683 | 0.028 | 0.415 | 0.030c |

| 10a·– | 0.024 | – | 0.024 | 0.450 | 0.065 | – | 0.065 | 0.450 | 0.043c 0.065c |

| 10b·– | 0.020 | – | 0.020 | 0.473 | 0.073 | – | 0.073 | 0.473 | 0.040c |

aSplitting due to the nine tert-butyl protons; bno splitting observed; csplitting due to one OCH2 group; dsplitting due to one OCH3 group; ethe EPR spectrum of 6c·– was observed after in-situ electroreduction of 1-tert-butyl 5-ethyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4c); see Scheme 6.

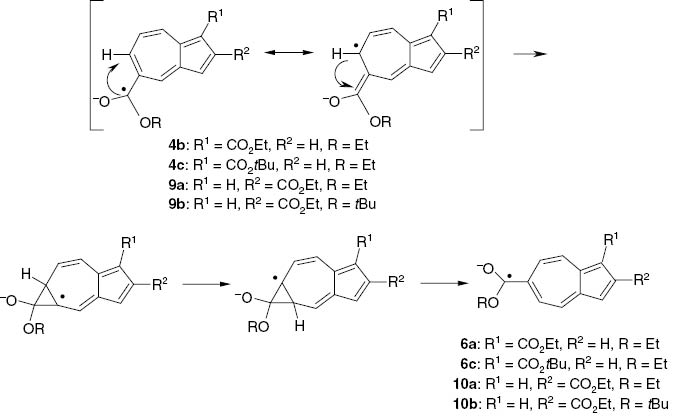

Rearrangement of alkyl azulene-1,5- and azulene-2,5-dicarboxylate radical anions to alkyl azulene-1,6- and azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate radical anions.

The assignment of the proton hfs coupling constants, in particular of the asymmetric diesters, was not always straightforward. In most cases, however, a satisfying result was obtained by comparison with tert-butyl substituted derivatives and with values calculated from MO spin densities by use of the McConnell equation aHμ = Qρπμ (see below).

Like ethyl azulene-1-carboxylate, the radical anions of dimethyl azulene-1,3-dicarboxylate (12a·–) were not persistent enough to give an EPR spectrum. However, its 6-tert-butyl derivative 12b·– provided a well-resolved spectrum. The high spin density in the 6-position which is presumably responsible for the low stability, i.e., the follow-up reactions of 12a·–, consequently leads to a measurable splitting (0.02 mT) due to the γ-protons of the tert-butyl substituent in 12b·–. Spin coupling with the OCH3 protons in the 1,3-positions is not observed.

The proton hfs coupling constants of the azulene-1,4-carboxylate radical anions 2a·– and 2b·– resemble those of 12b·–. Expectedly, the EPR spectra exhibit a large doublet splitting of 0.59 mT for the proton in the 6-position. Also, spin coupling with the two OCH2 protons probably of the ester group in the 4-position, but not in the 1-position, is observed (Fig. 3).

In-situ electroreduction of 1,5-diethyl (4b) and 1-tert-butyl 5-ethyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4c) did not yield the corresponding radical anions. Instead, EPR spectra were recorded which were identical with the spectra of the 1,6-isomers 6a·– and 6c·– (see Fig. 4). The same was observed for the 2,5-isomers 9a·– and 9b·– which rearranged to the 2,6-isomers 10a·– and 10b·– and gave rise to the corresponding EPR spectra. We have of course scrutinized the esters 4 and 9 by high-amplification 1H NMR spectroscopy in order to exclude any contamination with the isomers 6 and 10.

We assume a 5 → 6 rearrangement to take place but we cannot put forward a fully convincing reason for the observed rearrangement. Apparently, the azulene-1,6- and -2,6-dicarboxylate radical anions are considerably more stable and persistent compared with the 1,5- and 2,5-isomer which effect may be associated with the maximum spin density in the 6-position of azulene radical anions. Scheme 6 shows a proposed rearrangement mechanism.

The in-situ electroreduction of the diesters 6a, 6b, 4a, 8a, 8b, 10a and 10b, on the other hand, was very straightforward and led to the respective radical anions and the corresponding EPR spectra (see Table 3). Similarly as for the 1,4-diester radical anions 2·–, the protons of only one of the two ester groups in the 1,6-diesters, i.e., the two 6-OCH2 protons of 6a·– and the three 6-OCH3 protons of 6b·−, led to splitting whereas the 2,6-isomers exhibited splitting due to the four OCH2 protons in 10a·– and the two 2-OCH2 protons in 10b·–.

The radical anions exhibit g-factors of 2.0051 ± 0.0001 if one ester substituent is located at the seven-membered ring. A lower value of 2.00475 is found for the 1,3-diester radical anion 12b·–. This range is significantly higher than the g-factors of the related naphthalene esters which are found at 2.0032−2.0035 [2]. This effect may be due to a more pronounced transfer of spin density from the azulene hydrocarbon skeleton into the oxygen containing ester substituents.

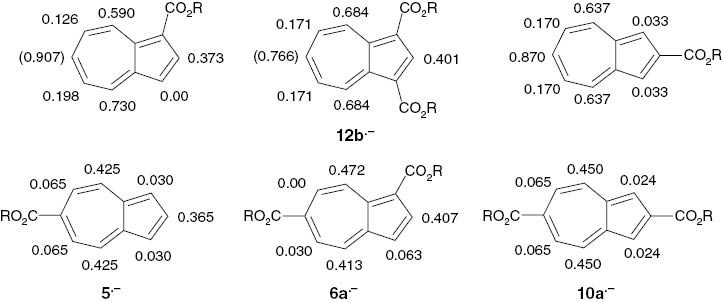

2.4 Spin density distributions

In our recent publication on alkyl azulenemonocarboxylate radical anions, we have pointed out that an influence of an electron-withdrawing ester substituent on the spin density distribution does exist [1], although it is not as pronounced as in the naphthalene series. We present here corresponding results on the spin density distribution of related dialkyl azulenedicarboxylate radical anions.

Table 4 shows the spin densities ρπμ obtained from the experimentally observed proton hfs coupling constants aHμ by use of the McConnell relationship ρπμ = aHμ/Q, together with theoretical values determined by McLachlan type as well as by more elaborate MO calculations. Due to significant deviations of all bond angles from 120° the choice of one suitable spin attenuation factor Q, which is valid for both the seven- and the five-membered ring of the azulene skeleton is not possible [18]. The agreement between the experimental and the theoretical spin densities is thus only moderate. In most cases, it is more satisfying for the McLachlan type results compared with the sophisticated semi-empirical (PM3) or ab-initio (DFT, B3LYP 1 STO 3-G21) calculations – just as in the case of the azulenemonoester radical anions [1], see Table 4.

Experimental (Exp: aHμ/–2.3) and MO theoreticala spin densities ρπμ.

| Radical anion | ρπ1 | ρπ2 | ρπ3 | ρπ4 | ρπ5 | ρπ6 | ρπ7 | ρπ8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1·– | ||||||||

| Expb | 0.012 | 0.172 | 0.012 | 0.270 | 0.058 | 0.384 | 0.058 | 0.270 |

| McL | –0.027 | 0.120 | –0.027 | 0.292 | –0.081 | 0.368 | –0.081 | 0.292 |

| PM3 | 0.001 | 0.113 | 0.001 | 0.168 | 0.018 | 0.286 | 0.018 | 0.168 |

| B3L | 0.003 | 0.113 | 0.003 | 0.173 | 0.020 | 0.277 | 0.020 | 0.173 |

| 12b·– | ||||||||

| Exp | 0.174 | 0.297 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.297 | |||

| McL | –0.022 | 0.216 | –0.022 | 0.272 | –0.078 | 0.333 | –0.078 | 0.272 |

| PM3 | 0.000 | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.178 | 0.018 | 0.311 | 0.016 | 0.181 |

| B3L | 0.002 | 0.088 | 0.002 | 0.184 | 0.019 | 0.299 | 0.018 | 0.183 |

| 2a·– | ||||||||

| Exp | 0.149 | 0.080 | 0.012 | 0.255 | 0.027 | 0.165 | ||

| McL | –0.022 | 0.104 | –0.026 | 0.211 | –0.022 | 0.184 | 0.024 | 0.126 |

| PM3 | 0.009 | 0.086 | 0.008 | 0.243 | 0.010 | 0.163 | 0.071 | 0.056 |

| B3L | 0.007 | 0.083 | 0.004 | 0.212 | 0.015 | 0.143 | 0.066 | 0.066 |

| 6a·– | ||||||||

| Exp | 0.177 | 0.027 | 0.180 | 0.013 | <0.015 | 0.205 | ||

| McL | –0.021 | 0.110 | –0.032 | 0.158 | 0.018 | 0.203 | 0.005 | 0.163 |

| PM3 | 0.000 | 0.097 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.048 | 0.232 | 0.040 | 0.129 |

| PM6 | 0.000 | 0.111 | 0.000 | 0.097 | 0.058 | 0.198 | 0.047 | 0.114 |

| B3L | 0.002 | 0.100 | 0.002 | 0.111 | 0.044 | 0.198 | 0.049 | 0.116 |

| 4a·– | ||||||||

| Exp | 0.090 | 0.116 | 0.423 | <0.01 | 0.381 | 0.149 | ||

| McL | 0.022 | –0.032 | 0.040 | 0.290 | –0.009 | 0.195 | 0.113 | –0.019 |

| PM3 | 0.041 | 0.020 | 0.050 | 0.313 | 0.017 | 0.186 | 0.133 | 0.131 |

| B3L | 0.019 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.324 | 0.010 | 0.263 | 0.066 | 0.015 |

| 8a·– | ||||||||

| Exp | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.087 | 0.297 | 0.012 | 0.180 | ||

| McL | –0.009 | 0.063 | 0.009 | 0.216 | –0.033 | 0.204 | –0.008 | 0.167 |

| PM3 | 0.005 | 0.110 | 0.018 | 0.224 | 0.085 | 0.240 | 0.028 | 0.129 |

| B3L | 0.010 | 0.088 | 0.015 | 0.178 | 0.013 | 0.220 | 0.028 | 0.139 |

| 10a·– | ||||||||

| Exp | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.196 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.196 | ||

| McL | –0.002 | 0.061 | –0.002 | 0.188 | –0.011 | 0.212 | –0.011 | 0.188 |

| PM3 | 0.008 | 0.105 | 0.006 | 0.128 | 0.035 | 0.232 | 0.037 | 0.133 |

| B3L | 0.008 | 0.093 | 0.007 | 0.121 | 0.037 | 0.194 | 0.036 | 0.123 |

aMcL, McLachlan approximation; PM3 see text; B3L, DFT calculation with Becke-3-LYP basis functions; bρπμ (Exp) were taken from Ref. [18].

Particularly the high spin densities which are generally observed at the even-numbered centers ρπ2, ρπ4, ρπ6 and ρπ8 [1, 4, 18, 19] are calculated significantly too low compared with the experimental values. The influence of ester substituents at the five-membered ring on the spin density distribution of azulene radical anions is only slight. Azulene (1·–) itself, the 1-ester, the 2-ester and the 1,3-diester (12b·–) closely resemble each other except for a minor perturbation of the symmetry in the 1-ester radical anions (see Scheme 7). This is somewhat unexpected since the electron distribution in azulene should be markedly influenced by strongly electron-withdrawing ester substituents. It may be due to the fact that the ester substituents of 12b·– are located at positions with very low spin densities. The change is more pronounced if ester substituents are located at the seven-membered ring. The spin density distribution in the 1,6- (6a·–) and the 2,6-diester (10a·–) radical anions are similar to each other and to the 6-monoester (5·–) but not to the 1-monoester or 2-monoester (Scheme 7). Ester substituents in the 1,4- (2·–), the 2,4- (8·–) and, most noticeable, in the 1,7-position (4·–) lead to significant effects on the spin density distribution. Apparently, the deviation of these esters from the symmetry of the azulene system causes a marked disturbance of the spin density distribution. For instance, diethyl azulene-1,7-dicarboxylate radical anions (4a·–) exhibit the largest proton hfs coupling constant (0.974 mT) in the 4-position, i.e. opposite to the ester substituent.

Proton hfs coupling constants aHμ (mT) in alkyl azulenemono- and -dicarboxylate radical anions. aH6 = (0.907) was measured for the ethyl 3-tert-butylazulenecarboxylate radical anion, and aH6 = (0.766) for 12b·– was calculated from the corresponding theoretical spin density ρπ6 = 0.333.

3 Conclusions

A variety of novel dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates was prepared by suitable methods.

The study of their electrochemical behavior revealed a reversible single electron transfer step. In-situ electroreduction of the esters led to the formation of persistent radical anions, the EPR spectra of which were recorded. Assignment of the proton hfs coupling constant was achieved by use of suitably substituted derivatives and theoretical calculations.

In certain cases an interesting rearrangement under migration of the functional group from the 5- into the 6-position was observed (Scheme 6). We tentatively explain this rearrangement with the high spin density and/or negative charge, respectively, in the 6-position of the radical anions.

The spin density distribution in the radical anions as determined experimentally from the proton hfs coupling constants by use of the McConnell relationship and calculated MO theoretically is discussed. The influence of electron-withdrawing ester substituents at the five-membered ring is rather slight (see Scheme 7) whereas ester substituents at the seven-membered ring, in particular in the 4- and 7-position, produce significant changes of the spin density distribution.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General

Melting points (corrected): Electrothermal. Boiling points were determined during distillation. UV/Vis spectra (solvent EtOH): Hitachi 200 spectrophotometer. NMR spectra (δ in ppm vs. Me4Si) were recorded on a WM 400 spectrometer (Bruker) at 400 MHz (1H) and 100 MHz (13C) in CDCl3. The NMR data are compiled in Tables 5 and 6. Assignments of the 1H NMR signals were performed by the DEPT method and consideration of the coupling patterns. The 13C NMR spectra of 2a, 4a, 4b, 6b, 8a, 9a, 10a, 12a, 12b, and 12c were calculated by use of the DFT method as described recently [1]. The effect of the iodo substituent in the 3-position of 12c was not properly captured [δ(C3) found: 73.7 ppm vs. calcd.: 110.5 ppm] since the smaller basis set LanL2D2 had to be used instead of the 6-311+G(2d,p) basis set. The 13C NMR signals of the other compounds were assigned with reference to the related derivatives. IR spectra (films for liquids, KBr pellets for solids, ν in cm–1): FT-IR 1720X (Perkin-Elmer) and Genesis-FT-IR (ATI-Mattson). MS: CH 7 (EI, 70 eV, Varian). HRMS: 70-250S (VG-Analytical). Thin layer chromatography (TLC): Al-foils coated with Kieselgel 60F254 (Merck). Column chromatography (CC): Kieselgel 60 (70–230 mesh, Merck).

Proton chemical shifts δ (in ppm), multiplicities and coupling constants J (in Hz) of dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates, 1,3-diacetylazulene (11a) and methyl 6-tert-butyl-3-iodoazulene-1-carboxylate (12c).

| Compound | 1-H | 2-H | 3-H | 4-H | 5-H | 6-H | 7-H | 8-H | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | – | 8.45 | 7.61 | – | 7.70 | 7.80 | 7.59 | 9.75 | 1.43, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (4.6) | d (4.6) | d (9.7) | t (9.9) | t (9.9) | d (9.7) | 1.47, t (7.1), 3H | |||

| 4.41, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4.53, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 2b | – | 8.39 | 7.60 | – | 7.67 | 7.78 | 7.55 | 9.73 | 1.47, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (4.1) | d (4.1) | d (9.7) | t (9.7) | t (9.9) | d (9.6) | 1.64, s, 9H | |||

| 4.53, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4b | – | 8.36 | 7.49 | 9.24 | – | 8.60 | 7.52 | 9.63 | 1.43, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (4.3) | d (4.3) | d (1.5) | d (10.7) | t (10.2) | d (10.2) | 1.44, t (7.1), 3H | |||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4.45, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4c | – | 8.32 | 7.48 | 9.24 | – | 8.60 | 7.50 | 9.62 | 1.44, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (4.3) | d (4.3) | d (2.0) | d (10.7) | t (10.2) | d (9.7) | 1.64, s, 9H | |||

| 4.44, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4a | – | 8.41 | 7.39 | 8.67 | 7.45 | 8.49 | – | 10.42 | 1.47, t (7.1), 6H |

| d (4.1) | d (4.1) | d (10.6) | t (10.3) | d (9.7) | d (1.6) | 4.45, q (7.1), 2H | |||

| 4.49, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 6a | – | 8.45 | 7.33 | 8.50 | 8.25 | – | 8.35 | 9.67 | 1.29, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (4.1) | d (4.1) | d (10.2) | dd (10.2/1.5) | dd (10.7/1.5) | d (10.7) | 1.51, t (7.1), 3H | |||

| 4.32, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4.53, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 6b | – | 8.47 | 7.32 | 8.49 | 8.24 | – | 8.36 | 9.66 | 1.43, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (4.1) | d (4.1) | d (10.2) | dd (10.2/1.5) | dd (10.2/1.5) | d (10.7) | 4.00, s, 3H | |||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 8a | 7.85 | – | 8.09 | – | 7.48 | 7.68 | 7.25 | 8.44 | 1.42, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (1.5) | d (1.5) | d (10.2) | td (10.2/1.0) | d (9.7) | d (9.2) | 1.47, t (7.1), 3H | |||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4.54, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 8b | 7.83 | – | 8.06 | – | 7.39 | 7.67 | 7.22 | 8.42 | 1.42, t (7.1), 3H |

| d (1.5) | d (1.5) | d (10.2) | td (10.2/1.0) | t (9.6) | d (9.7) | 1.69, s, 9H | |||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 9a | 7.88 | – | 8.00 | 9.22 | – | 8.44 | 7.20 | 8.53 | 1.42, t (7.1), 3H |

| s | s | d (1.5) | dd (9.7) | t (9.9) | dd (10.2/1.5) | 1.43, t (7.1), 3H | |||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4.43, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 9b | 7.86 | – | 7.97 | 9.17 | – | 8.42 | 7.19 | 8.48 | 1.42, t (7.1), 3H |

| s | s | s | d (9.6) | t (10.2) | d (10.6) | 1.63, s, 9H | |||

| 4.41, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 10a | 7.79 | – | 7.79 | 8.44 | 8.00 | – | 8.00 | 8.44 | 1.41, t (7.1), 3H |

| s | s | d (10.4) | d (10.4) | d (10.4) | d (10.4) | 1.42, t (7.1), 3H | |||

| 4.41, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 10b | 7.80 | – | 7.80 | 8.45 | 7.96 | – | 7.96 | 8.45 | 1.42, t (7.1), 3H |

| s | s | d (10.7) | d (10.7) | d (10.7) | d (10.7) | 1.63, s, 9H | |||

| 4.42, q (7.1), 2H | |||||||||

| 11a | – | 8.64 | – | 10.03 | 7.82 | 8.01 | 7.82 | 10.03 | 2.72, s, 6H |

| s | d (9.7) | t (10.2) | t (9.7) | t (10.2) | d (9.7) | ||||

| 12a | – | 8.81 | – | 9.76 | 7.73 | 7.94 | 7.73 | 9.76 | 3.93, s, 6H |

| s | d (10.2) | t (10.2) | t (9.6) | t (10.2) | d (10.2) | ||||

| 12b | – | 8.74 | – | 9.67 | 7.93 | – | 7.93 | 9.67 | 1.49, s, 9H |

| s | d (10.2) | d (9.7) | d (9.7) | d (10.2) | 3.93, s, 6H | ||||

| 12c | – | 8.34 | – | 8.31 | 7.74 | – | 7.76 | 9.48 | 1.40, s, 9H |

| s | d (11.0) | dd (11.0/2.0) | d (11.0/2.0) | d (11.0) | 3.85, s, 3H |

13C NMR Chemical shifts δ (ppm) of dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates and the related compounds 11aa and 12cb.

| Compound | C1 | C2 | C3 | C3a | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C8a | CO c | R-C, O-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 117.6 | 141.7 | 116.5 | 139.5 | 138.9 | 125.8 | 137.2 | 128.2 | 137.4 | 142.3 | 164.7 | 13.9; 14.1 CH3 |

| 168.5 | 59.5; 61.8 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 2b | 119.2 | 141.9 | 116.2 | 139.8 | 138.8 | 125.5 | 137.6 | 127.9 | 137.2 | 142.2 | d | 13.9; 28.1 CH3 |

| 61.8 OCH2; 79.8 OCq | ||||||||||||

| 4b | 120.0 | 138.4 | 121.8 | 141.6 | 138.7 | 126.2 | 140.1 | 125.5 | 139.8 | 139.2 | 164.6 | 14.0; 14.1 CH3 |

| 167.0 | 59.8; 61.7 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 4c | 120.0 | 138.4 | 121.6 | 141.4 | 138.6 | 126.0 | 140.3 | 125.1 | 139.8 | 138.9 | 164.2 | 14.0; 27.3 CH3 |

| 167.1 | 61.6 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 80.1 OCq | ||||||||||||

| 4a | 121.2 | 139.2 | 120.2 | 143.3 | 137.7 | 124.5 | 140.3 | 127.2 | 140.5 | 137.2 | 164.0 | 13.9; 14.1 CH3 |

| 167.4 | 59.7; 61.1 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 6b | 117.9 | 142.7 | 117.8 | 145.3 | 135.7 | 126.2 | 137.1 | 127.1 | 136.0 | 141.2 | 164.6 | 14.1; 14.7 CH3 |

| 167.6 | 52.1; 52.8 OCH3 | |||||||||||

| 59.6; 61.4 OCH2 | ||||||||||||

| 8a | 120.3 | 139.6 | 118.0 | 134.4 | 142.2 | 123.3 | 138.8 | 124.8 | 140.6 | 140.8 | 165.0 | 13.9; 14.0 CH3 |

| 168.4 | 60.4; 61.8 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 8b | 120.0 | 139.3 | 117.8 | 134.3 | 142.5 | 123.0 | 139.0 | 124.4 | 140.5 | 142.5 | 165.1 | 14.0; 27.8 CH3 |

| 167.6 | 60.4 OCH2; 83.0 OCq | |||||||||||

| 9a | 122.11 | 138.8 | 123.8 | 137.2 | 140.3 | 124.1 | 140.7 | 122.14 | 142.5 | 139.0 | 164.8 | 13.9; 14.0 CH3 |

| 167.1 | 60.5; 61.5 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 9b | 121.8 | 138.8 | 123.5 | 137.2 | 140.3 | 125.7 | 140.7 | 122.0 | 142.3 | 138.9 | 164.9 | 14.0; 27.8 CH3 |

| 166.2 | 60.4 OCH2; 81.6 Cq | |||||||||||

| 10a | 119.0 | 142.5 | 119.0 | 140.8 | 138.3 | 123.5 | 138.5 | 123.5 | 138.3 | 140.8 | 164.9 | 13.8; 14.0 CH3 |

| 167.2 | 60.5; 61.9 OCH2 | |||||||||||

| 10b | 118.2 | 140.2 | 118.2 | 140.8 | 137.7 | 122.9 | 139.9 | 122.9 | 137.7 | 140.8 | 164.5 | 13.3; 27.0 CH3 |

| 165.5 | 59.8 OCH2; 81.6 OCq | |||||||||||

| 11a | 123.4 | 140.8 | 123.4 | 143.3 | 143.4 | 132.3 | 141.4 | 132.3 | 143.4 | 143.3 | 194.9 | 28.6 CH3 |

| 12a | 115.5 | 143.2 | 115.5 | 143.6 | 138.8 | 130.3 | 140.3 | 130.3 | 138.8 | 143.6 | 164.9 | 50.8 OCH3 |

| 12b | 115.0 | 142.4 | 115.0 | 142.5 | 137.8 | 128.5 | 165.0 | 128.5 | 137.8 | 142.5 | 165.3 | 31.4 CH3 |

| 38.6 Cq; 50.8 OCH3 | ||||||||||||

| 12c | 117.3 | 138.9 | 73.7 | 142.1 | 139.3 | 125.4 | 164.3 | 126.3 | 136.2 | 145.5 | 164.5 | 31.4 CH3 |

| 38.6 Cq; 50.7 OCH3 |

a11a: 1,3-Diacetylazulene; b12c: methyl 6-tert-butyl-3-iodoazulene-1-carboxylate; cthe signals of C=O substituents at the five-membered ring are shifted up-field as compared to the signals of C=O substituents at the seven-membered ring; dnot detected.

Differential pulse polarograms were measured with the VA 663/Polarecord 626 (Metrohm), cyclic voltamograms: VA-Scanner E 612 (Metrohm) with plotter Servotec 7040 A (Hewlett Packard). Potentials were measured in DMF/0.1 n tetrapropylammonium bromide (TPAB) by use of a HMDE working cathode vs. an internal Ag wire as reference electrode, which corresponds to the Ag/AgBr couple in the TEAB solution [16, 17].

The in-situ generation of the radical anions in dry DMF at suitable temperatures by use of a Bank Electronic (Wenking type) potentiostat MP 31 and the measurement of the EPR spectra in quartz flat cells has been described earlier [1]. A Bruker ESP 300 E spectrometer was used. The spectra were processed by use of the WIN-EPR 9212101 software (Bruker). Simulation of the spectra was carried out with the Simfonia program (Bruker).

4.2 X-ray structure determinations

The crystal data of 4a and 12b and a summary of experimental details are given in Table 7. The structures were solved by Direct Methods (Multan) [20], and differential Fourier synthesis [21]. Refinement was performed by full-matrix least-squares methods. Crystallographic data of 4a and 12b have been deposited [22].

Crystal data and parameters pertinent to data collection and structure refinement for 4a and 12b.

| 4a | 12b | |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C16H16O4 | C18H20O4 |

| Formula weight, Mr | 272.29 | 300.34 |

| Crystal color and size, mm3 | Red-violet block | Violet block |

| Size not determined | 0.6 × 0.4 × 0.3 | |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | P21/n | Pnma |

| a, pm | 1226.9(2) | 1651.1(2) |

| b, pm | 804(1) | 1625.9(2) |

| c, pm | 1433.5(2) | 584.5(1) |

| β, deg | 104.55(2) | 90. |

| Cell volume, V, pm3 | 1367.8 × 106 | 1569.1 × 106 |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Temperature, K | 173 | 173 |

| Density ρcalcd., g cm−3 | 1.322 | 1.271 |

| μ(CuKα), cm–1 | 7.90 | 7.26 |

| F(000), e | 576 | 640 |

| Diffractometer | CAD4-SDP | CAD4-SDP |

| (Enraf Nonius) | (Enraf Nonius) | |

| Radiation; monochromator | CuKα; graphite | CuKα; graphite |

| Wave length λ, Å | 1.54059 | 1.54178 |

| Scan mode | θ−2θ | θ−2θ |

| θ-range, deg | 4.3–76.5 | 5.4–76.8 |

| hkl range | 0 ≤ h ≤ +15 | −20 ≤ h ≤ +20 |

| −3 ≤ k ≤ +10 | −20 ≤ k ≤ 0 | |

| −18 ≤ l ≤ +17 | −7 ≤ l ≤ +7 | |

| Refl. measured/unique/Rint | 3046/2878/– | 6442/1718/0.0565 |

| Refl. observed [I > 2 σ(I)] | 2850 | 965 |

| Refined parameters | 226 | 125 |

| R [I > 2 σ(I)] | 0.0365 | 0.0803 |

| wR [I > 2 σ(I)] | 0.0983 | 0.1954 |

| wR (all data) | 0.2132 | 0.2756 |

| Δρfin | Not determined | 0.71/–0.36 |

4.3 Preparations

4.3.1 Alkyl azulenecarboxylates by carbobromination and alkoholysis [1], [6]. General protocol

Caution! CCl4is carcinogenic! CO is toxic!

An ethyl azulenecarboxylate (1, 3 or 5) was heated to reflux in CCl4 under an atmosphere of dry N2. A solution of oxalyl dibromide (30 % excess) in dry CCl4 was injected into the boiling solution. Refluxing was continued for 20 min while the color turned from blue to dark red, and CO evolved. EtOH or t-BuOH (6 mL per mmol azulene) was dropped into the warm reaction mixture which was then stirred for another 30 min. The solvents were removed under vacuum. The residue was extracted with hexane and the extract was pre-purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, AcOEt-hexane 1:50).

4.3.1.1 Diethyl azulene-1,4-dicarboxylate (2a)

Ethyl azulene-4-carboxylate (1) or a mixture of 1 and ethyl azulene-5-carboxylate (3) [1] (112.6 mg, 0.56 mmol) gave 2a as a semisolid, blue oil (8.6 mg, 5.5 %) after CC (AcOEt-hexane 1:40, Rf = 0.11). – UV/Vis: λmax (lg εmax) = 191 (4.32), 226 (4.15), 283 (4.54), 350 (3.61), 537 (2.52) nm. – MS: m/z (%) = 273 (18), 272 (98) [M]+, 244 (8) [M–C2H4]+, 228 (8), 227 (66) [M–OEt]+, 216 (13), 200 (56) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (100) [M–CO2Et]+, 172 (32), 171 (16), 155 (16), 153 (18), 128 (22) [C10H8]+, 127 (25) [C10H7]+, 126 (52), 125 (21), 115 (45) [C9H7]+, 77 (12) [C6H5]+, 76 (10). – HRMS: m/z = 272.1060 (calcd. 272.1049 for C16H16O4).

4.3.1.2 1-tert-butyl 4-ethyl azulene-1, 4-dicarboxylate (2b)

Ethyl azulene-4-carboxylate (1) [1] (70.2 mg, 0.34 mmol) gave 2b as a blue oil (3.1 mg, 3.1 %) after alcoholysis with t-BuOH and CC (AcOEt-hexane 1:40, Rf = 0.60). – MS: m/z (%) = 300 (10) [M]+, 245 (17), 244 (100) [M–C4H8]+, 227 (11) [M–OtBu]+, 218 (63), 200 (15) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (66), 172 (12), 127 (16) [C10H7]+, 126 (26) [C10H6]+, 115 (58) [C9H7]+, 77 (8) [C6H5]+, 69 (10), 58 (27), 57 (26) [C4H9]+, 56 (18) [C4H8]+.

4.3.1.3 Diethyl azulene-1,5-dicarboxylate (4b) and diethyl azulene-1,7-dicarboxylate (4a)

Ethyl azulene-5-carboxylate (1) [1] (250 mg, 1.20 mmol) gave 4b as violet crystals (63 mg, 19.5 %) after CC (3 × AcOEt-hexane 1:40, Rf = 0.15). M. p. 95–96 °C (EtOH). – UV/Vis: λmax (lg εmax) = 193 (4.50), 224 (4.32), 280 (4.66), 301 (3.91), 355 (4.07), 368 (4.41), 481 (2.72), 513 (2.78), 548 (2.78), 599 (2.39) nm. – IR: 1706 (C=O), 1688 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 272 (98) [M]+, 244 (16) [M–C2H4]+, 228 (16), 227 (86) [M–OEt]+, 216 (19), 200 (52) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (100) [M–CO2Et]+, 172 (22), 153 (16), 127 (12) [C10H8]+, 126 (34) [C10H7]+, 125 (18), 115 (58) [C9H7]+, 84 (10). – HRMS: m/z = 272.1046 (calcd. 272.1049 for C16H16O4).

4a (14.7 mg, 4.3 %) was obtained by prolonged CC (3 × AcOEt/hexane 1:40, Rf = 0.08) as red-violet crystals. M. p. 107–108 °C (hexane). – UV/Vis: λmax (lg εmax) = 204 (4.56), 224 (4.66), 289 (4.60), 295 (4.63), 316 (4.14), 376 (3.92), 385 (4.06), 524 (2.53), 559 (2.46), 587 (2.14), 614 (2.02) nm. – IR: 1707 (C=O), 1682 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 272 (100) [M]+, 244 (16) [M–C2H4]+, 227 (78) [M–OEt]+, 216 (12), 200 (53) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (99) [C10H6CO2Et]+, 172 (23), 154 (14), 153 (16), 128 (16) [C10H8]+, 127 (37) [C10H7]+, 115 (65) [C9H7]+, 77 (10) [C6H5]+. – HRMS: m/z 272.1050 (calcd. 272.1049 for C16H16O4).

4.3.1.4 1-tert-butyl 5-ethyl azulene-1, 5-dicarboxylate (4c)

Ethyl azulene-5-carboxylate (3) [1] (187 mg, 0.93 mmol) gave 4c as violet crystals (31.5 mg, 11.1 %) after alcoholysis with t-BuOH and CC (AcOEt-hexane 1:20, Rf = 0.60). – MS: m/z (%) = 300 (2) [M]+, 245 (12), 244 (60) [M–C4H8]+, 227 (8) [M–OtBu]+, 216 (44), 200 (12) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (46) [C10H6CO2Et]+, 172 (12), 127 (16) [C10H7]+, 126 (22) [C10H6]+, 115 (48) [C9H7]+, 83 (33), 71 (44) [C6H5]+, 69 (63), 57 (100) [C4H9]+.

4.3.1.5 Diethyl azulene-1,6-dicarboxylate (6a)

Ethyl azulene-6-carboxylate (5) [1] (65.8 mg, 0.33 mmol) gave 6a as blue-green needles (6.4 mg, 7.2 %) after CC (AcOEt-hexane 1:40).

4.3.2 Dialkyl azulenecarboxylates by ring enlargement of ethyl indane-2-carboxylate [23]

Caution! Alkyl diazoacetates are toxic, carcinogenic and explosive! All reactions with these reagents must therefore be performed behind a protective shield under a well-ventilated hood [24].

Ethyl diazoacetate [25] or tert-butyl diazoacetate [26] was dropped into an excess of ethyl indane-2-carboxylate (7) with stirring under N2 at 20 °C. The mixture was heated to 140 °C for 6 h. The excessive indane was distilled off under vacuum. The residue (hydroazulene) was dissolved in a tenfold amount of benzene and refluxed with an equimolar amount of chloranil for 2 h. The color changed from yellow to green-blue. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was extracted with hexane in a Soxhlet apparatus. Flash-CC (toluene-hexane 1:1) of the extract yielded the deeply blue colored azulene (mixture), which was purified by CC.

Reaction of 7 [1] (15.55 g, 82 mmol) with ethyl diazoacetate (4.90 g, 43 mmol) led to a mixture of diethyl azulene-2, 4-dicarboxylate (8a), diethyl azulene-2,5-dicarboxylate (9a) and diethyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate (10a). The components were separated by CC (AcOEt-hexane 1:20).

4.3.2.1 Diethyl azulene-2,4-dicarboxylate (8a)

Rf = 0.33, blue oil (254 mg, 2.2 %). – IR: 1723 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 273 (18), 272 (100) [M]+, 244 (9) [M–C2H4]+, 228 (16), 227 (40) [M–OEt]+, 200 (88) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (42) [C10H6CO2Et]+, 172 (46), 171 (28), 155 (34), 129 (28) [C10H9]+, 128 (42) [C10H8]+, 127 (45) [C10H7]+, 126 (45) [C10H7]+, 115 (92) [C9H7]+, 77 (14) [C6H5]+. – HRMS: m/z 272.1046 (calcd. 272.1049 for C16H16O4).

4.3.2.2 Diethyl azulene-2,5-dicarboxylate (9a)

Rf = 0.41, blue violet crystals (337 mg, 1.5 %). M. p. 56–60 °C. – MS: m/z (%) = 273 (20), 272 (100) [M]+, 244 (12) [M–C2H4]+, 228 (13), 227 (40) [M–OEt]+, 216 (21), 200 (58) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (44) [C10H6CO2Et]+, 172 (60), 128 (39) [C10H8]+, 127 (49) [C10H7]+, 117 (25), 115 (70) [C9H7]+, 91 (8) [C7H7]+, 77 (16) [C6H5]+.

4.3.2.3 Diethyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate (10a)

Rf = 0.48, blue-green needles (171 mg, 0.8 %). M. p. 77–80 °C. – UV/Vis: λmax (lg εmax) = 275 (4.38), 278 (4.34), 318 (3.74), 329 (3.88), 344 (4.12), 584 (2.56), 620 (2.69), 678 (2.65), 760 (2.24), 871 (2.89) nm. – IR: 1732 (C=O), 1710 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 272 (17) [M]+, 248 (6), 231 (6), 227 (7), 200 (10) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 172 (8), 149 (15), 145 (10), 129 (18), 128 (18), 117 (50), 116 (100) [C9H8]+, 115 (32) [C9H7]+, 91 (9) [C7H7]+. – HRMS: m/z = 272.1034 (calcd. 272.1049 for C16H16O4).

Reaction of 7 [1] (17.76 g, 95 mmol) with tert-butyldiazoacetate (4.85 g, 34 mmol) led to a mixture of 2-ethyl 4-tert-butyl azulene-2,4-dicarboxylate (8b), 2-ethyl 5-tert-butyl azulene-2,5-dicarboxylate (9b) and 2-ethyl 6-tert-butyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate (10b). The components were separated by repeated CC.

4.3.2.4 2-Ethyl 4-tert-butyl azulene-2,4-dicarboxylate (8b)

Rf = 0.12 (2 × AcOEt-hexane 1:30, then toluene-hexane 1:1), blue oil (765 mg, 2.7 %). – IR: 1722 (C=O), 1688 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 300 (9) [M]+, 245 (12), 244 (70) [M–C4H8]+, 227 (8), 200 (22) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (28) [C10H6CO2Et]+, 174 (10), 172 (50), 171 (14), 129 (14) [C10H8]+, 126 (18) [C10H7]+, 117 (32), 116 (42), 115 (54) [C9H7]+, 77 (10) [C6H5]+, 57 (100) [C4H9]+. – HRMS: m/z = 300.1369 (calcd. 300.1360 for C18H20O4).

4.3.2.5 2-Ethyl 5-tert-butyl azulene-2,5-dicarboxylate (9b)

Rf = 0.15 (2 × AcOEt-hexane 1:30, then toluene-hexane 1:1), slowly crystallizing blue oil (1.39 g, 4.9 %). – IR: 1710 (C=O), 1688 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 300 (22) [M]+, 245 (16), 244 (100) [M–C4H8]+, 227 (12), 216 (14), 200 (17) [C10H7CO2Et]+, 199 (32) [C10H6CO2Et]+, 172 (50), 127 (13) [C10H7]+, 126 (16), 115 (22) [C9H7]+, 57 (14) [C4H9]+.

4.3.2.6 2-Ethyl 6-tert-butyl azulene-2,6-dicarboxylate (10b)

Rf = 0.12 (1st: 2 × AcOEt-hexane 1:30, 2nd: toluene-hexane 1:1), blue oil (345 mg, 1.2 %).

4.3.2.7 1,3-Diacetylazulene (11a)

Friedel-Crafts-acylation of azulene (500 mg, 3.90 mmol) with acetyl chloride in nitromethane in the presence of AlCl3 according to the standard laboratory procedure [27] and purification by CC (CH2Cl2) gave 11a (367 mg, 44.4 %) as red-orange needles, m. p. 188–190 °C (AcOEt); lit. [28]: 185–187 °C; lit. [8]: 186–188 °C. IR: 1639 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 212 (32) [M]+, 198 (10), 197 (100) [M–CH3]+, 139 (5), 126 (12), 115 (13) [C9H7]+, 91 (8) [C7H7]+.

4.3.2.8 Dimethyl azulene-1,3-dicarboxylate (12a)

Was prepared by iodoform splitting of 11a according to the literature procedure [8]. Flash CC (CH2Cl2, Rf = 0.50) yielded pure 12a (31.9 mg, 8.0 %) as red needles, m. p. 168–170 °C (lit. [8]: 171 °C). UV/Vis: λmax (lg εmax) = 285 (4.44), 321 (3.82), 340 (4.06), 351 (4.09), 477 (2.08), 496 (2.76), 545 (2.34) nm. IR: 1703 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 244 (45) [M]+, 214 (15), 213 (100) [M–OCH3]+, 170 (8), 168 (6), 127 (11) [C10H7]+, 126 (12), 91 (12) [C7H7]+.

4.3.2.9 Dimethyl 6-tert-butylazulene-1,3-dicarboxylate (12b)

Iodoform splitting of 11b [29] (191 mg, 0.71 mmol) as described for the preparation of 12a, and CC (CH2Cl2-hexane 3:1, Rf = 0.40) gave 12b (67 mg, 31.5 %) as red needles, m. p. 144–145 °C. – IR: 1703 (C=O), 1681 (C=O). – MS: m/z (%) = 301 (14), 300 (100) [M]+, 285 (7) [M–CH3]+, 270 (9), 269 (67) [M–OCH3]+, 253 (7), 241 (7), 239 (9), 181 (9), 167 (7), 165 (11), 152 (6), 127 (5) [C10H7]+, 57 (13), [C4H9]+. – HRMS: m/z = 300.1377 (calcd. 300.1362 for C18H20O4).

4.3.2.10 Methyl 6-tert-butyl-3-iodoazulene- 1-carboxylate (12c)

Lilac oil (Rf = 0.77), was isolated as by-product (19 mg, 7.3 %). – MS: m/z (%) = 369 (18) [M]+, 368 (100) [M]+, 353 (10) [M–CH3]+, 337 (18), 254 (9), 241 (4) [M–I]+, 167 (18), 165 (16), 152 (12), 127 (12) [C10H7]+, 57 (12), [C4H9]+.

4.3.2.11 1-Ethyl 6-methyl azulene-1,6-dicarboxylate (6b)

Ethyl 6-methylazulene-1-carboxylate (13) [1] (80 mg, 0.37 mmol) was oxidized with O2 in DMF in the presence of KOAc as catalyst, and methylated with CH2N2 analogously to the lit. [15]. CC (AcOEt-hexane 1:20 Rf = 0.25) gave 6b as blue-green crystals (35 mg, 36.6 %), m. p. 86–87 °C (hexane). – MS: m/z (%) = 259 (8), 258 (58) [M]+, 230 (16) [M–C2H4]+, 214 (15), 213 (100) [M–OEt]+, 186 (34) [M–C2H4–CO]+, 154 (14), 153 (9), 127 (9) [C10H7]+, 126 (25) [C10H6]+, 115 (14) [C9H7]+.

4.4 Quantum chemical calculations

DFT calculations of the NMR spectra [30] were performed at the Taito supercluster of the Finnish IT Center for Science (CSC), cf. http://www.csc.fi.

McLachlan-type MO calculations were performed by use of an unpublished Fortran-77 program Hueckel 88 [31, 32]. The Qcpe software Mopac 6.0 was used for the AM1 calculations. Semi-empirical PM6-type MO calculations were performed by use of the program package Mopac 2009 [33]. DFT-based geometry optimizations and spin density calculations were performed by the B3LYP method [34, 35] with 6-31G(p,d) basis sets. The program Firefly [36, 37] was used for the DFT calculations. The Qcpe programs Draw and Jmol (Open Project; http://sourceforge.net/projects/jmol/) were used for the graphical presentation of the results. A conventional PC (Pentium Dual Core CPU E5200, 2.5 GHz; 3.25 GB RAM) was applied for the calculations.

Acknowledgments

Support of this work by the Universität Hamburg, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. U. Behrens, Universität Hamburg (X-ray), Dr. D. Abeln, Universität Hamburg (X-ray) and Mr. M. Krasmann, Universität Hamburg (technical assistance) for their valuable help.

References

[1] Part 22: J. Voss, T. Pesel, D. Buddensiek, J. Lehtivarjo, Z. Naturforsch. 2014, 69b, 466.10.5560/znb.2014-3303Search in Google Scholar

[2] K. Strey, J. Voss, J. Chem. Res. 1998, (S) 110; (M) 648.10.1039/a706189gSearch in Google Scholar

[3] F. Gerson, W. Huber, Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy for Chemists, Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 2003.10.1002/3527601627Search in Google Scholar

[4] R. Bachmann, C. Burda, F. Gerson, M. Scholz, H.-J. Hansen, Helv. Chim. Acta1994, 77, 1458.10.1002/hlca.19940770523Search in Google Scholar

[5] F. Gerson, M. Scholz, H.-J. Hansen, P. Uebelhart, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1995, 2, 215.10.1039/p29950000215Search in Google Scholar

[6] W. Treibs, H. Orttmann, R. Schlimper, C. Lindig, Chem. Ber. 1959, 92, 2152.10.1002/cber.19590920930Search in Google Scholar

[7] W. Treibs, H. J. Neupert, J. Hiebsch, Chem. Ber. 1959, 92, 1216.10.1002/cber.19590920534Search in Google Scholar

[8] A. G. Anderson jr., R. Scotoni jr., E. J. Cowles, C. G. Fritz, J. Org. Chem. 1957, 22, 1193.10.1021/jo01361a017Search in Google Scholar

[9] A. W. Hanson, Acta Crytallogr. 1965, 19, 19.10.1107/S0365110X65002700Search in Google Scholar

[10] O. Bastiansen, J. L. Derissen, Acta Chem. Scand. 1966, 20, 1319.10.3891/acta.chem.scand.20-1319Search in Google Scholar

[11] J. Zindel, S. Maitra, D. A. Lightner, Synthesis1996, 1217.10.1055/s-1996-4370Search in Google Scholar

[12] M. V. Barybin, M. H. Chisholm, N. S. Dalal, T. H. Holovics, N. J. Patmore, R. E. Robinson, D. J. Zipse, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15182.10.1021/ja0541884Search in Google Scholar

[13] T. Zieliński, M.Kędziorek, J. Jurczak, Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 838.Search in Google Scholar

[14] T. Zieliński, M. Kędziorek, J. Jurczak, Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 6231.10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.07.061Search in Google Scholar

[15] M. Yokota, R. Koyama, H. Hayashi, S. Uchibori, T. Tomiyama, H. Miyazaki, Synthesis1994, 1418.10.1055/s-1994-25706Search in Google Scholar

[16] ∆E = −520 mV vs. the SCE. J. Voss, R. Edler, J. Chem. Res. 2007, 226.10.3184/030823407X209660Search in Google Scholar

[17] H. Günther, J. Voss, J. Chem. Res. 1987, (S) 68, (M) 775.Search in Google Scholar

[18] I. Bernal, P. H. Rieger, G. K. Fraenkel, J. Chem. Phys. 1962, 37, 1489.10.1063/1.1733313Search in Google Scholar

[19] R. J. Waltman, J. Bargon, Magn. Reson. Chem. 1995, 33, 679.10.1002/mrc.1260330811Search in Google Scholar

[20] G. Germain, P. Main, M. M. Woolfson, Acta Crystallogr. 1971, A27, 368.10.1107/S0567739471000822Search in Google Scholar

[21] A. C. T. North, D. C. Phillips, F. S. Mathews, Acta Crystallogr. 1968, A24, 351.10.1107/S0567739468000707Search in Google Scholar

[22] CCDC 839375 (4a) and CCDC 805056 (12b) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre viawww.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data.request/cif.Search in Google Scholar

[23] W. Treibs, A. Schmidt, P. Stoss, Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1957, 603, 145.10.1002/jlac.19576030115Search in Google Scholar

[24] S. T. R. Müller, D. Smith, P. Hellier, T. Wirth, Synlett2014, 25, 871.10.1055/s-0033-1340835Search in Google Scholar

[25] N. E. Searle, M. Newman, G. Ottmann, C. Grundmann, Org. Synth. Coll. 1963, IV, 424.Search in Google Scholar

[26] M. Regitz, J. Hocker, A. Liedhegener, Org. Synth. Coll. 1973, V, 179.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Autorenkollektiv, Organikum, 19th ed., Johann Ambrosius Batrth Verlag, Leipzig, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[28] K. Hafner, A. Stephan, C. Bernhard, Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1961, 650, 42. The authors prepared 26a by Friedel-Crafts tert-butylation of 1 and subsequent aceto-de-tert-butylation. No NMR and MS data are given.10.1002/jlac.19616500105Search in Google Scholar

[29] T. Shoji, S. Ito, T. Okujima, J. Higashi, R. Yokoyama, K. Toyota, M. Yasunami, N. Morita, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 1554.10.1002/ejoc.200801078Search in Google Scholar

[30] M. W. Lodewyk, M. R. Siebert, D. J. Tantillo, Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1838.Search in Google Scholar

[31] D. Buddensiek, Dissertation, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, 1985, pp. 64, 200.Search in Google Scholar

[32] D. Buddensiek, B. Köpke, J. Voss, Chem. Ber. 1987, 120, 575.10.1002/cber.19871200418Search in Google Scholar

[33] J. J. P. Stewart, J. Mol. Mod. 2007, 13, 1173. URL: http://www.springerlink.com/content/ar33482301010477/fulltext.pdf. We thank Prof. Stewart for providing us with the newest versions MOPAC 2009 and MOPAC 2012 for our calculations.Search in Google Scholar

[34] A. D. Becke, Phys. Rev. 1988, A38, 3098.10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098Search in Google Scholar

[35] A. D. Becke, J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 9173.10.1063/1.463343Search in Google Scholar

[36] A. A. Granovsky, Firefly Project, Moscow (Russia). We kindly thank Dr. Granovsky for providing us with the latest version of Firefly.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Firefly is based on Gamess from Iowa State University: M. W. Schmidt, K. K. Baldridge, J. A. Boatz. S. T. Elbert, M. S. Gordon, J. H. Jensen, S. Koseki, N. Matsunaga, K. A. Nguyen, S. J. Su, T. L. Windus, M. Dupuis, J. A. Montgomery, J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 1347.10.1002/jcc.540141112Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- EPR studies on carboxylic esters, 23 [1]. Preparation of new dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates and EPR-spectroscopic study of their radical anions

- Synthesis and crystal structure of a 3D copper(II)–silver(I) coordination polymer assembled through hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking and metal–π interactions, {[Cu(phen)2(CN)][Ag(CN)2] · 3H2O}n (phen = 1,10-phenanthroline)

- A polyoxometalate-based inorganic–organic hybrid material: synthesis, characterization structure and photocatalytic study

- Hydrogen-bonded assemblies of two organically templated borates: syntheses and crystal structures of [(1,10-phen)(H3BO3)2] and [2-EtpyH][(B5O6(OH)4]

- Catalytic activity of the nanoporous MCM-41 surface for the Paal–Knorr pyrrole cyclocondensation

- A new route for the synthesis of 4-arylacetamido-2-aminothiazoles and their biological evaluation

- Structural and spectroscopic characterization of isotypic sodium, rubidium and cesium acesulfamates

- Nd39Ir10.98In36.02 – A complex intergrowth structure with CsCl- and AlB2-related slabs

- Syntheses, structures and magnetic properties of two mononuclear nickel(II) complexes based on bicarboxylate ligands

- Synthesis and characterization of some new fluoroquinolone-barbiturate hybrid systems

- Synthesis of pyrazoles containing benzofuran and trifluoromethyl moieties as possible anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- EPR studies on carboxylic esters, 23 [1]. Preparation of new dialkyl azulenedicarboxylates and EPR-spectroscopic study of their radical anions

- Synthesis and crystal structure of a 3D copper(II)–silver(I) coordination polymer assembled through hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking and metal–π interactions, {[Cu(phen)2(CN)][Ag(CN)2] · 3H2O}n (phen = 1,10-phenanthroline)

- A polyoxometalate-based inorganic–organic hybrid material: synthesis, characterization structure and photocatalytic study

- Hydrogen-bonded assemblies of two organically templated borates: syntheses and crystal structures of [(1,10-phen)(H3BO3)2] and [2-EtpyH][(B5O6(OH)4]

- Catalytic activity of the nanoporous MCM-41 surface for the Paal–Knorr pyrrole cyclocondensation

- A new route for the synthesis of 4-arylacetamido-2-aminothiazoles and their biological evaluation

- Structural and spectroscopic characterization of isotypic sodium, rubidium and cesium acesulfamates

- Nd39Ir10.98In36.02 – A complex intergrowth structure with CsCl- and AlB2-related slabs

- Syntheses, structures and magnetic properties of two mononuclear nickel(II) complexes based on bicarboxylate ligands

- Synthesis and characterization of some new fluoroquinolone-barbiturate hybrid systems

- Synthesis of pyrazoles containing benzofuran and trifluoromethyl moieties as possible anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents