Abstract

The bandgap was tuned to investigate the electronic and optical aspects using first-principle calculations for solar cells and other optical applications. The bandgap range varies from 1.6 to 2.1 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs and from 0.8 to 1.5 eV for Ga1−xAlxSb (x = 0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0). The dispersion, polarisation, and attenuation have been illustrated in terms of transparency and maximum absorption of light. The inversion of polarised atomic planes near the resonance allows the maximum absorption in ultraviolet to visible region. The Penn’s model (ε1(0) ≈ 1 + (ℏωp/Eg)2) and optical relation

1 Introduction

The semiconductor alloys have very interesting properties and are used to manufacture a variety of optoelectronic devices such as solar cells, infrared light emitting diodes, semiconducting lasers, and so on [1], [2], [3], [4]. The existing literature is insufficient about the computational studies of electronic and optical properties of GaAlAs and GaAlSb compounds. However, ternary GaAs:Bi alloy are studied for their electronic and optical properties by first principle [5]. It was found that GaAsBi alloy is promising for use as saturable absorber [6] highlights the optoelectronic properties of Al1−xGaxN using density functional theory (DFT)–based full-potential linearised augmented plane wave method. This study forecasts that the material has capability for its use in optical device manufacturing. The first-principle computations based on full potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) with modified Becke–Johnson potential were carried out to obtain optoelectronic properties of InxGa1xN/GaN (001) superlattices (SLs) with short periodicity [7]. The computational results suggest that these SLs may be used for optoelectronic device applications by controlling their bandgap [7]. The optical and electronic properties of (InxGa1xN)n/(GaN)n (001) zinc-blende SLs (where x = 0.5 and n = 3–4) were obtained by using the first-principle method based on FP-LAPW with modified Becke–Johnson potential within generalised gradient approximation (GGA) [8]. It was found that these materials are useful for solar cell and optical device applications. They reported optoelectronic properties of hexagonally structured GaN1−xPx alloys and predict these materials to be potential candidate for solar cell applications [9].

The studied alloys Ga1−xAlxAs/Sb are potential candidates for optoelectronic and solar cell applications. The tuning of bandgap from 1.6 to 2.1 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs and from 0.8 to 1.5 eV for Ga1−xAlxSb shows the maximum absorption of light is in the visible region of electromagnetic spectrum. Moreover, the results show in the visible region that the reflection and optical loss are negligible with maximum absorption of light, which increases the importance of the studied materials for optical applications. We have used most versatile, accurate approach of Backe and Johnson (mBJ) to calculate the results. The mBJ potential improves the electronic states and gives accurate value of bandgap.

In this article, the bandgap of GaAlAs and GaAlSb is tuned by using first-principle studies, i.e. DFT-based full-potential linearised augmented plane wave method. The purpose of these calculations is to investigate the electronic and optical properties of Al-doped GaAs and GaSb for solar cell design and optical applications. The electronic structures and optical properties are studied by computing the electronic bandgap, density of states (total as well as partial), dielectric constant, and lattice constant, as well as static dielectric constant. Also, the static refractive index and extinction coefficient, absorption coefficient, optical conductivity, reflectivity, and optical loss factor are computed. The calculated parameters make the studied materials potential candidates for the energy storage purposes.

2 Method of Calculations

The electronic and optical characteristics of Al-doped GaAs and GaSb alloys are depicted by DFT-dependent full-potential linearised augmented plane wave method that simulated in Wein2k code [10]. The zinc-blende structures of studied compounds are optimised and relaxed by PBEsol approximations because it calculates ground states parameter more exact than local density approximation (LDA) and GGA [11], [12]. The optimised structures are converged by self-consistent field to find the Hamiltonian of the system. The exchange-correlation energy (Exc) term in the Hamiltonian is usually approximated by well-known LDA, GGA, PBEsol, or hybrid approximations [13], [14]. The ground state parameters are accurately found from these approximations, while excited state properties are underestimated. For example, the bandgap reports through these approximations are sturdily underestimated. The problem associated with aforementioned approximations to underestimate the bandgap is self-interaction error that restricts derivative discontinuity that is important when we compare the Kohn–Sham and experimental bandgaps. On the other hand, the hybrid functional is more expensive and LDA + U/GGA + U are limited to localised states (3d and 4f electrons) [15]. Consequently, to solve the above difficulties, Tran and Blaha [16] and Koller [17] improved the Backe-Johnson potential (TB-mBJ) that exactly calculates the electronic structures of semiconductors, insulators, and metal oxides. This potential is successfully implemented in the present calculations to elaborate the electronic structure and bandgap-dependent optical properties. Moreover, the wave function splits into two regions; the core electrons are confined in the muffin-tin region having spherical harmonic-type solution, and the rest of the region has plane wave-like wave function. However, the potential in both regions kept the same through the FP-LAPW method. The basic set of inputs is adjusted as the Kmax × RMT = 8.0 and Gmax = 16, respectively. Furthermore, the k-mesh grid of 4000 k-points has been used for the accurate convergence through iteration process up to 10−4 Ry. We have chosen the k-mesh grid of 4000 k-points because at and above this value the energy release from the alloys during charge/energy convergence becomes constant.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Electronic Properties

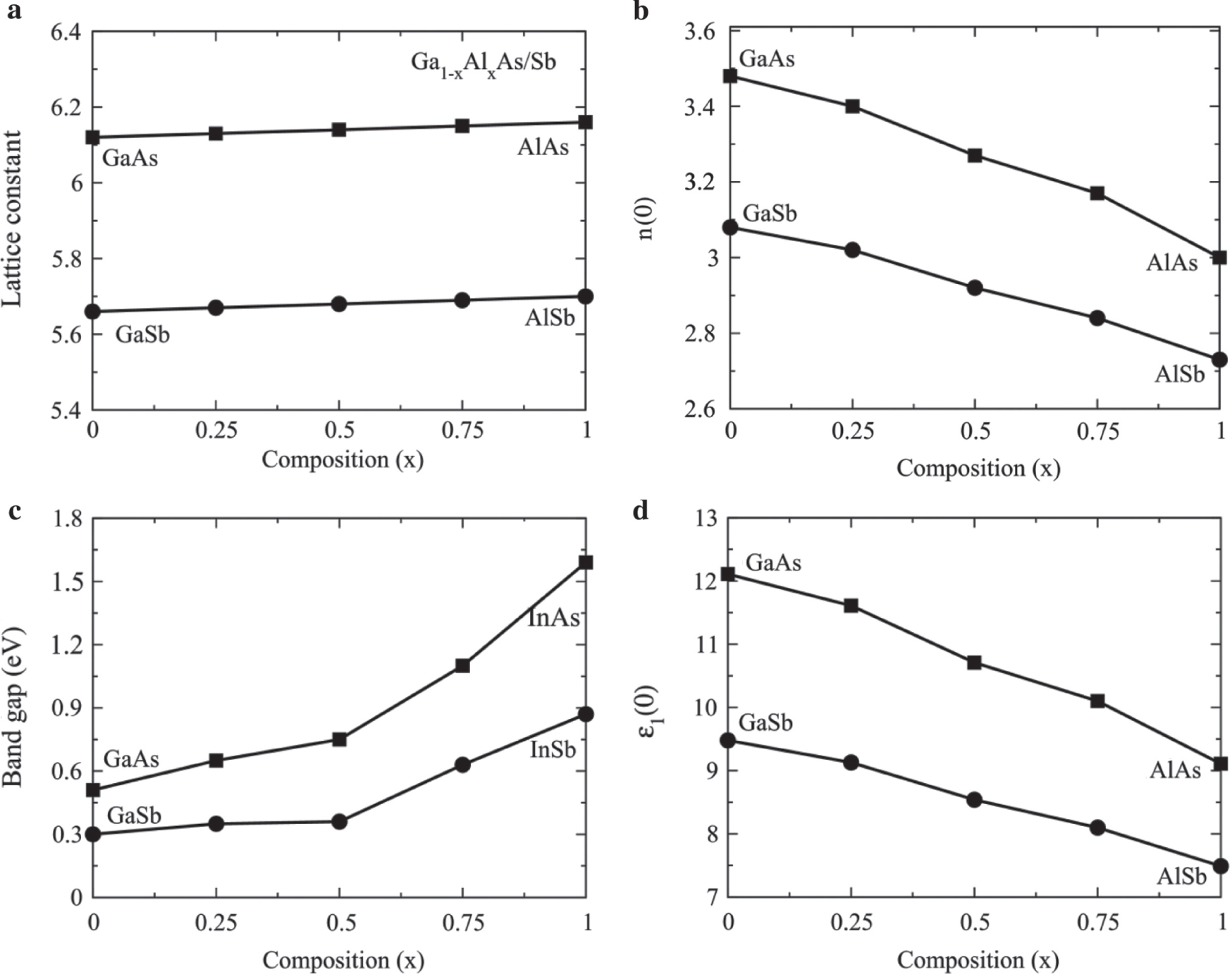

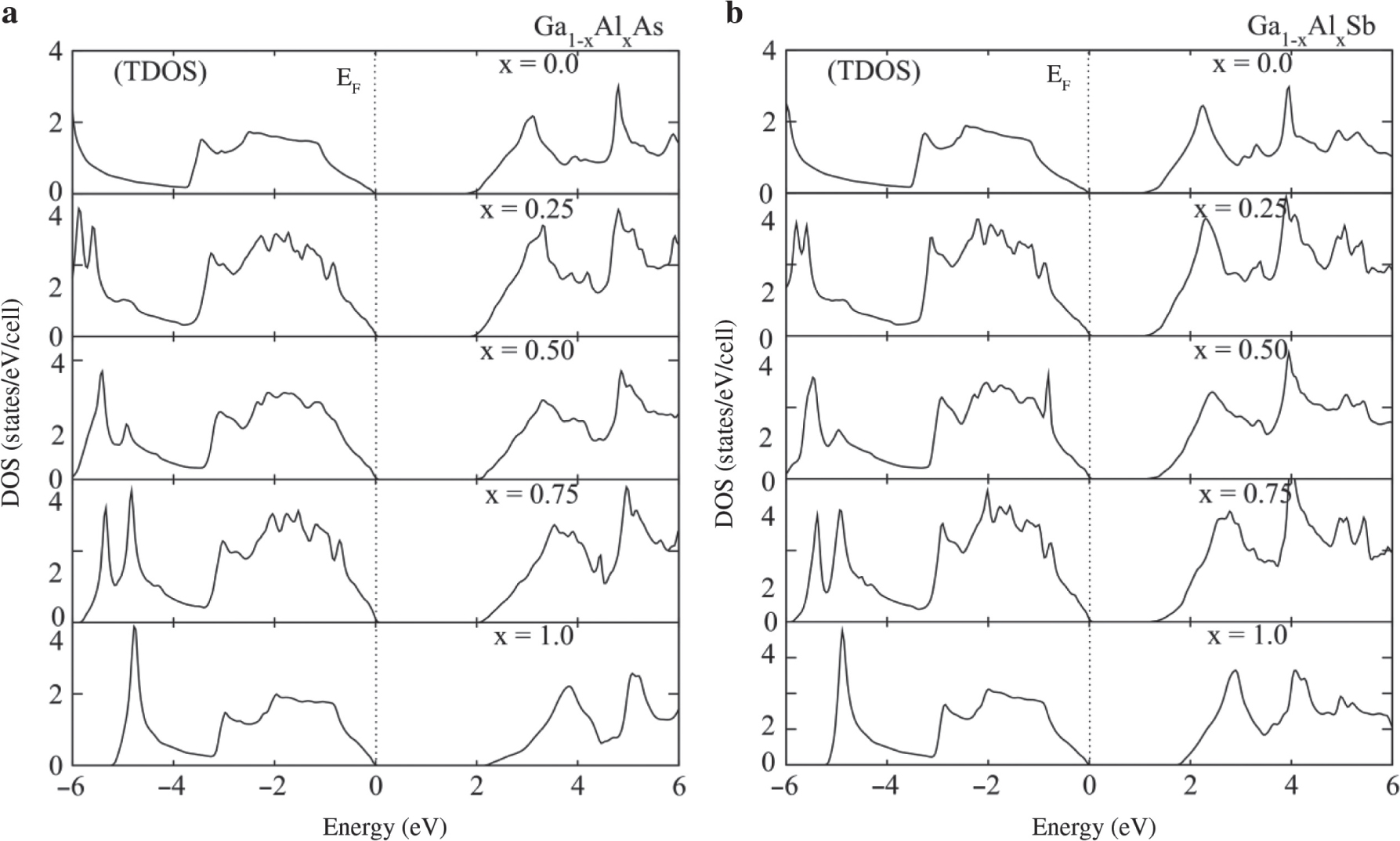

The studied structures are optimised in the cubic phase with space group F43m (216) for binary compounds and Pm3m (215) for doped alloys. The optimised lattice constant for Al-doped GaAs/Sb has been plotted in Figure 1a, which shows the minor increases in lattice constant because of replacement of Al ions by Ga. Further, the increase in the lattice constant has a direct effect on the bandgap as the dopant concentration increases, as shown in Figure 1c. The cutoff values ε1(0) and refractive index n(0) at zero frequency decrease with increasing the composition of Al concentration from GaAs/Sb to AlAs/Sb as shown in Figure 1b and d, which decreases the bandgap, as plotted in Figure 1c. The states are depleted from the Fermi energy as Al contents increases, as shown in Figure 2a,b showing that we can tune the bandgap of the studied materials for solar cells, functional in visible and ultraviolet (UV) regions.

(a) Lattice constant, (b) static refractive index, (c) electronic bandgap, and (d) static dielectric constant of Ga1−xAlxAs and Ga1−xAlxSb plotted against composition range 0.0–1.0.

Total density of states (TDOS) and partial density of states (PDOS) of (a) Ga1−xAlxAs and (b) Ga1−xAlxSb plotted against composition range 0.0–1.0.

For optical device fabrications, the materials should be stable thermodynamically. The thermodynamic stability has been ensured from the enthalpy of formation (ΔHf) and specific heat capacity (Cv), whereas mechanical stability has been ensured from the elastic tensor matrix. The enthalpy of formation has been calculated from the relation [18]. The negative value of enthalpy shows the stability of the studied materials. Moreover, the enthalpy of formation varies from −0.34 to −0.48 eV for GaAs and AlAs, while it is −0.158 to −0.622 eV for GaSb and AlSb. Therefore, the stability increases by increasing the Al contents in GaAs/Sb.

Moreover, the specific heat capacity at constant sampling volume has been calculated by the relation mentioned in [19]. The value of specific heat capacity (calculated at room temperature) increases from 43 to 46 J/Kmol for GaAs to AlAs and from 42 to 45 J/Kmol for GaSb to AlSb. This shows that Al doping increases the thermal stability as calculated by the formation energy.

3.2 Optical Properties

The optical properties of semiconductor materials depend on the light–matter interaction, transition recombination rate, and bandgap of the semiconductor materials. The symmetry directions in the first Brillion zone at which the valence band maxima and conduction band minima lie are very important to decide the nature in which the bandgap exists. For different symmetry directions, the bandgap is indirect, and phonons (energy of lattice vibration) are involved in the lattice that reduces the performance and reliability of the optoelectronic devices. On the other hand, the same symmetry points of the valence band maxima and conduction band minima form the direct band that make easy transition from valence band to conduction, and loss of energy reduces. It also increases the recombination rate that enhances the efficiency of light-emitting devices [20], [21]. The real and imaginary parts of frequency-dependent dielectric constant are associated with each other through the Kramer–Kronig relation [22] and formulated as follows:

where P is the principal integer, and k is the wave vector that is integrated in the boundary of first Brillion zone. The relation between the imaginary and real constituents of dielectric tensor has been solved by the Kramer–Kronig relation to illustrate the light–matter interaction. The related prospects of photon energy–matter interaction like refraction (sum of refractive index n(ω) and extinction coefficient k(ω)), reflection R(ω), absorption α(ω), optical conduction σ(ω), and energy loss function L(ω) have been dragged through following mathematical expressions:

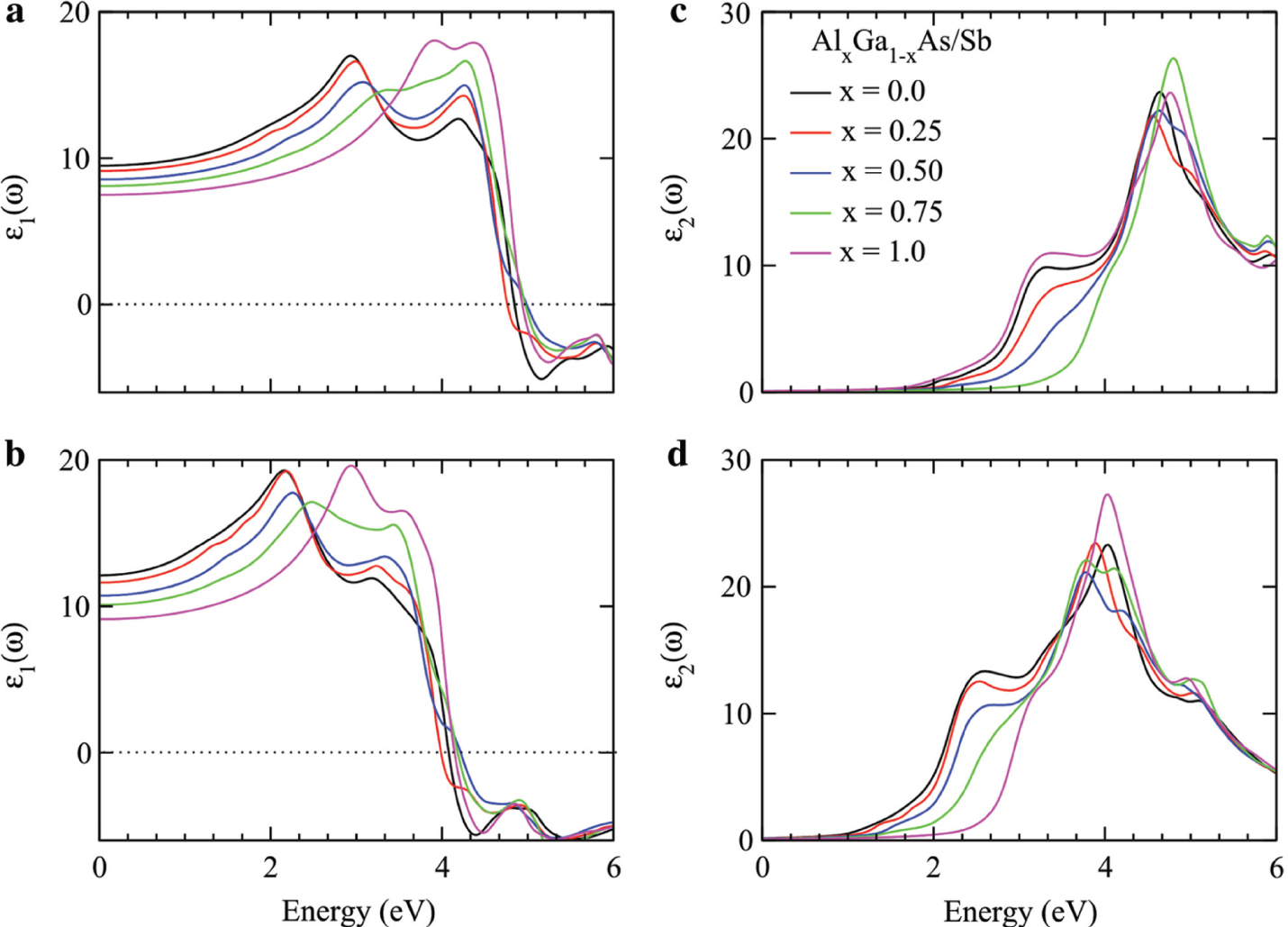

where Wcv is the transition probability per unit time. All the above calculated parameters are plotted in Figures 3–6. The Re ε(ω) elucidates the distribution of light (polarisation) and its divergence (polarisation) when photons interact with material of irregular refractive index. The calculated results of Re ε(ω) for Ga1−xAlxAs are plotted in Figure 3a and for Ga1−xAlxSb in Figure 3c. The distribution of light energy in the materials depends on the frequency because the phase velocity of quantum oscillations of electron in the material medium varies with frequency. For particular incident photon energy, the electronic oscillation frequency and photon frequency match with each that produces resonance. At resonance frequency, the dispersion of light is maximum, and light is linearly polarised to a single plane [23]. The Re ε(ω) increases with increasing the photon energy that creates a resonance effect at 3 and 4 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs, while for Ga1−xAlxSb at 2 and 3 eV because electrons are less bound in Sb than As. A minor increase in energy from resonance sharply decreases the Re ε(ω) to negative value at 5 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs and at 4 eV for Ga1−xAlxSb, which exceeds the group velocity than speed of light. Moreover, the material characteristic changes and becomes opaque for light similar to metals. The cutoff values Re ε(0) at zero frequency decrease with increasing the composition of Al contents from GaAs/Sb to AlAs/Sb, which decreases the bandgap as plotted in Figure 1c and d. Therefore, Re ε(0) and Eg (eV) are according to Penn’s model Re ε(0) ≈ 1 + (ℏωp/Eg), which confirms the reliability and accuracy of the calculated results [24], [25].

Real part of dielectric constant and imaginary parts of dielectric constant for Ga1−xAlxAs (a, c) and Ga1−xAlxSb (b, d) plotted against the energy range 0–6 eV.

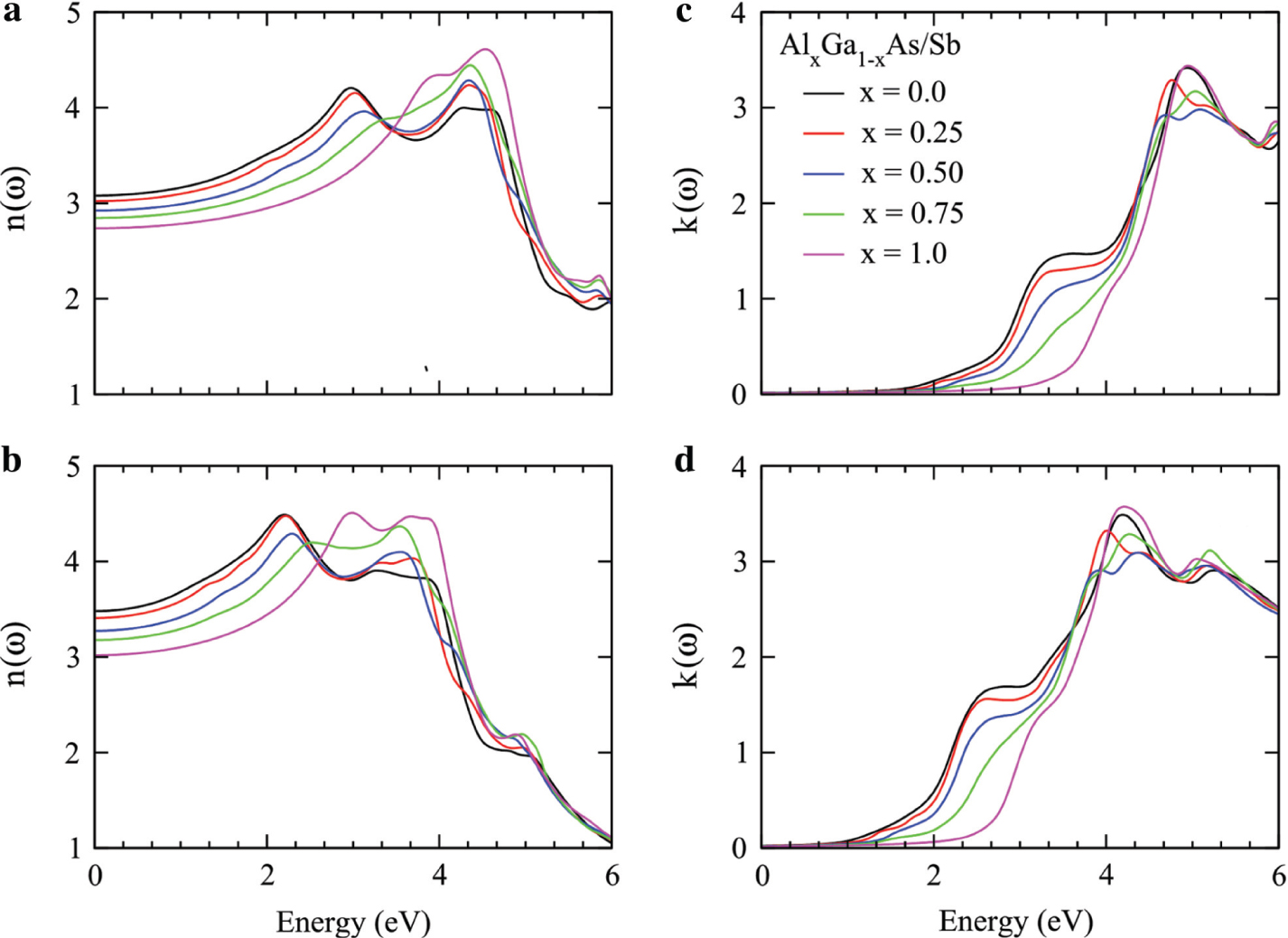

Refractive index and extinction coefficient for Ga1−xAlxAs (a, c) and Ga1−xAlxSb (b, d) plotted against the energy range 0–6 eV.

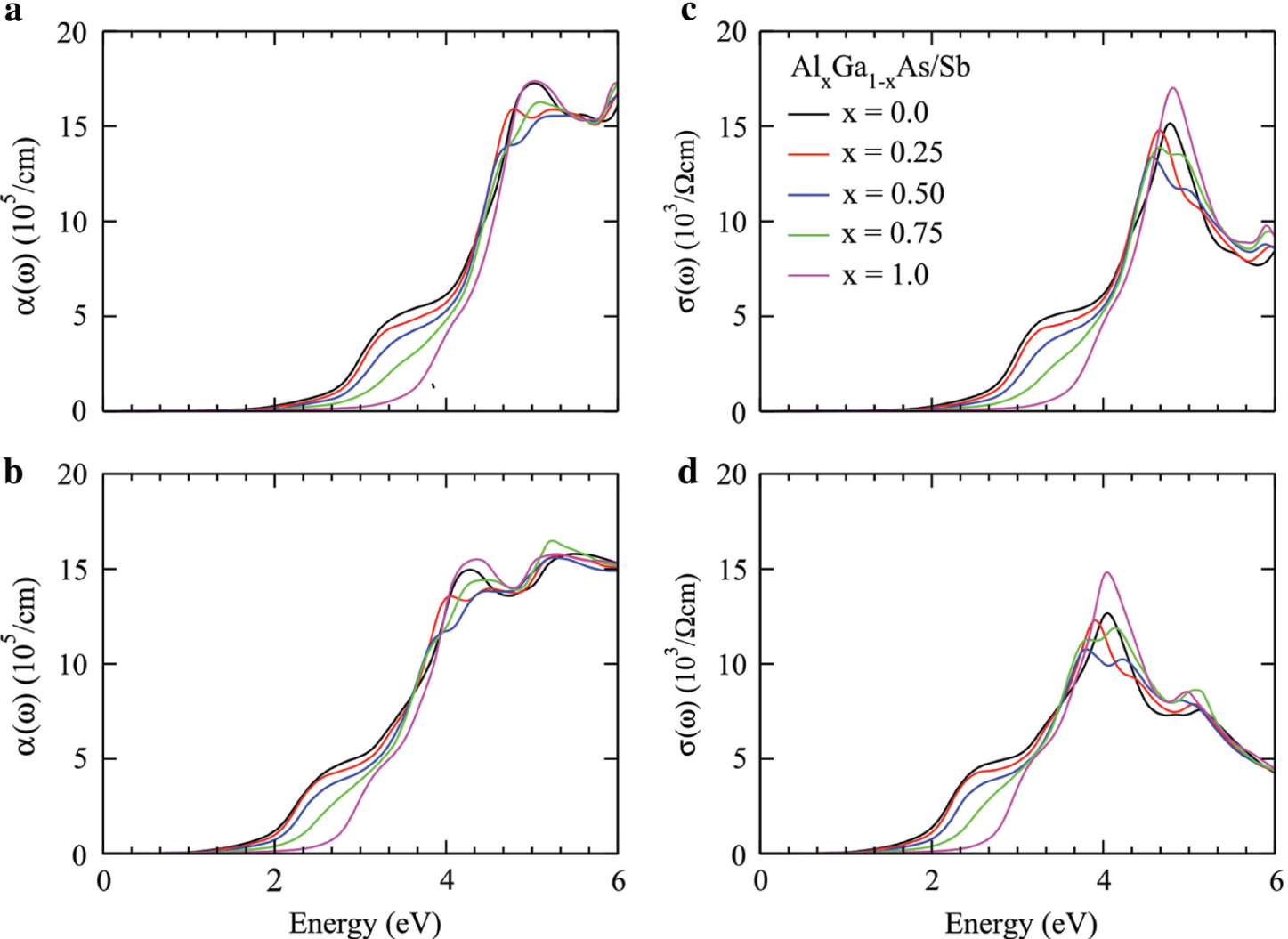

Absorption coefficient and optical conductivity for Ga1−xAlxAs (a, c) and Ga1−xAlxSb (b, d) plotted against the energy range 0–6 eV.

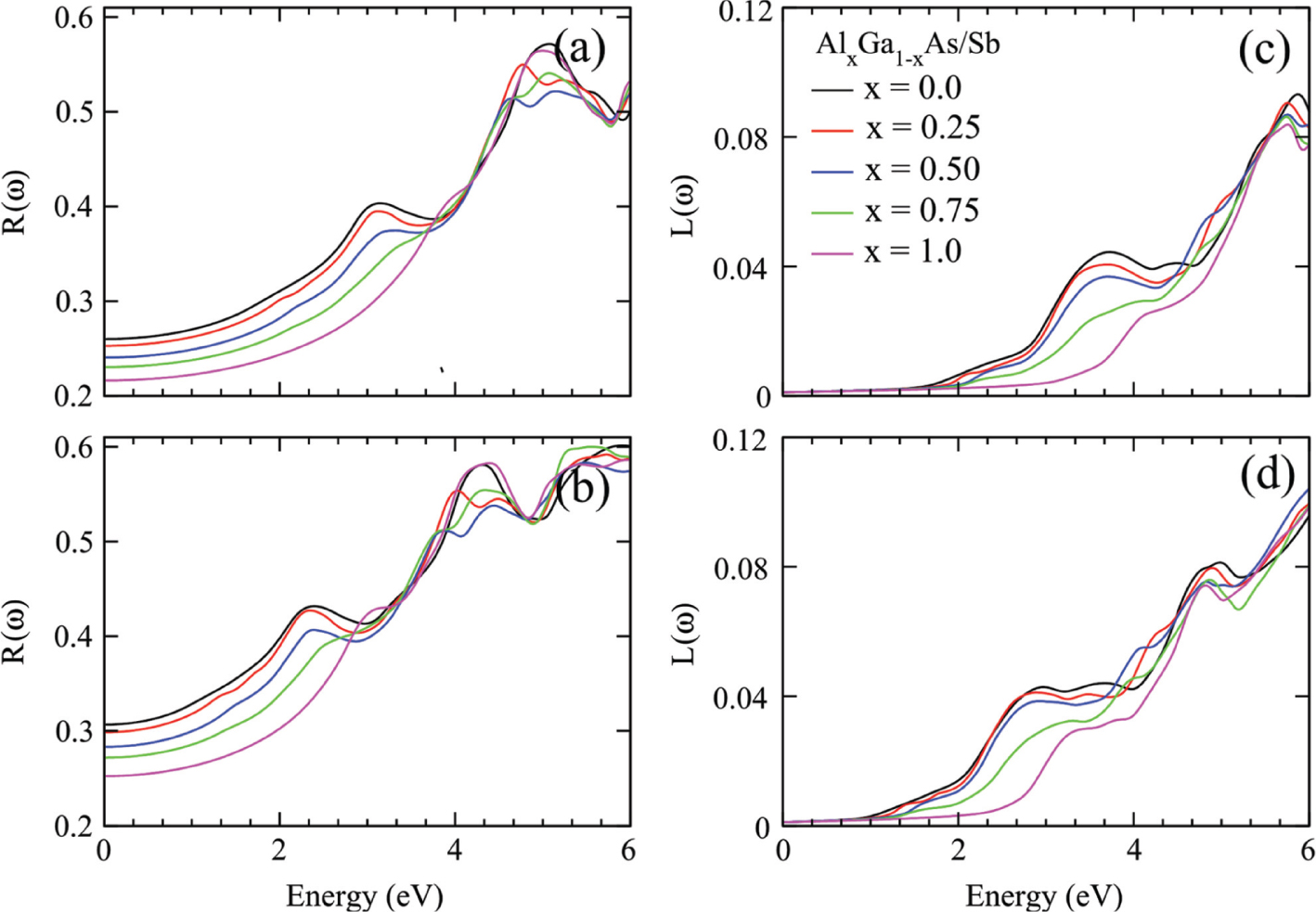

Reflectivity and optical loss factor for Ga1−xAlxAs (a, c) and Ga1−xAlxSb (b, d) plotted against energy range 0–6 eV.

The Im ε(ω) count part of energy is absorbed by the material when light passed through it. The calculated values of energy reduction of the incident photon are plotted in Figure 3b for Ga1−xAlxAs and Figure 3d for Ga1−xAlxSb. The Im ε(ω) at zero frequency represents the optical bandgap of the studied materials that forced the condition on materials; light cannot be absorbed below this threshold limit of the bandgap. The energy of the incident photons below the bandgap limit of the materials may be used to release the electrons from the influence of the nuclei forces [26], [27]. The calculated values of bandgap calculated from the Im ε(ω) threshold limit are slightly overestimated as reported from band structure treatment because of theoretical limitations and approximations in the DFT analysis as shown in in Figure 1c and Figure 3b and d. By increasing the incident photon energy from optical bandgap, the light starts to be absorbed. The absorption increases as the frequency of incident photon changes from resonance because the polarised plane of atoms rotates from linear position. The absorption is maximum at energy where the plane of polarised atoms rotates completely from one direction to another (parallel to perpendicular direction) [28], [29], [30]. The absorption has peak values at 4.6 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs and at 4 eV for Ga1−xAlxSb, as seen in Figure 3b and d. After it, absorption decreases because of the metallic behaviour of the materials in the high-energy region that reflects incident light. The doping of Al in GaAs moves the absorption peaks to high-energy region. Furthermore, the replacement of Sb with As has a great impact on the optical behaviour of the studied materials. The maximum absorption regions decide that Ga1−xAlxAs is suitable for UV light absorption and Ga1−xAlxSb is suitable for visible edge (mean near UV region) light-absorbing materials. Therefore, for solar cell applications, Ga1−xAlxSb is a more potential candidate than Ga1−xAlxAs. In addition, the doping of Al shifts the absorption region from large wavelength to short wavelength, which depicts that the studied materials are blue shifted.

The complex refraction is the combination of refractive index n(ω) (real part) and extinction coefficient k(ω) (imaginary part). The refractive index n(ω) measures how fast light travels in the material medium as compared to vacuum and dispersion of light, while extinction coefficient k(ω) measures the attenuation of light. Therefore, the refractive index n(ω) and extinction coefficient k(ω) seem to be the replica of Re ε(ω) and Im ε(ω), as presented in Figures 3 and 4.

The refractive index n(ω) and extinction coefficient k(ω) are related through the mathematical relations

The absorption coefficient α(ω) measures the reduction of light intensity per unit centimetre when it passed through the material, as plotted in Figure 5a and c. The critical value of photon energy at which the absorption of material is zero is nominated as optical bandgap. The calculated optical bandgap from absorption coefficient, Re ε(ω), and extinction coefficient k(ω) is consistent with the bandgap calculated from the band structures. The little bit variation is involved because of mathematical treatment of simulation coding and approximations. The maximum absorption region is located in the periphery of 5 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs and 4.2 eV for Ga1−xAlxSb. Therefore, the absorption regions clarify the solar cell applications of Ga1−xAlxAs for UV region and Ga1−xAlxSb for visible edge to near-UV region [36]. The GaAs/Sb edge is closer to the visible region than the AlAs/Sb edge. The variation of dopant composition tunes the bandgap of the studied materials for desire energy range to increase the efficiency of the solar cell.

The optical conductivity σ(ω) measures the flow of carriers per unit centimetre when light of suitable frequency falls on the materials. The calculated results of optical conductivity σ(ω) are presented in Figure 5c and d. The electrons in the orbits absorb photon energy and move to conduction band to induce the forward current. The optical conductivity has peak values at 5 and 4.2 eV for Ga1−xAlxAs and Ga1−xAlxSb similar to the absorption coefficient because maximum energy absorption increases the kinetic energy of electrons. The peak values of optical conductivity increase with increasing the dopant concentration of Al into GaAs/Sb because of increase in the free electrons.

The light radiations fall on the material surface consumed energy in absorption, reflection, and transmission. The reflected part of the light provides information about the material surface morphology, photon electron interaction, and scattering of light from material planes. The calculated plots of reflectivity R(ω) for the studied materials are presented in Figure 6a and c. The response of materials Ga1−xAlxAs/Sb at 5 and 4.2 eV for reflection is maximum. The doping concentration of Al in GaAs/Sb reduces the reflectivity peaks intensity because of maximum absorption of light in the region. The loss of optical energy due to scattering and heating is also a major change for the optical device fabrication. The calculated values of optical loss function L(ω) are plotted in Figure 6b and d. The value of L(ω) increases with increasing the photon energy range, but its quantity is very few. The comprehensive analysis of optical properties of the studied materials reveals the maximum absorption of light in UV, and for the visible region, minimum loss of energy and reflection in functional regions (UV and visible) increases the potential of the studied alloys for solar applications.

4 Conclusion

In this article, the electronic and optical properties of Ga1−xAlxAs and Ga1−xAlxSb are simulated by means of first principle based on full-potential linearised augmented plane wave method using the Wein2k code. The lattice constant is optimised for Al-doped GaAs/Sb and found that the increase in lattice constant due to increase in dopant concentration (i.e. replacement of Al ions by Ga) increases the bandgap of the studied materials. This shows that the bandgap of the studied materials can be tuned by varying the dopant composition to obtain the desired energy range for increased solar cell efficiency. The calculated negative value of enthalpy shows that the studied materials are thermodynamically stable, and the stability increases with increase in Al contents in GaAs/Sb. The bandgap values calculated from Im ε(ω) threshold limit are slightly overestimated because of the approximations in the DFT computations. However, the detailed analysis of optical properties shows that there is maximum absorption of light in UV and visible region and also minimum loss of energy and reflection in functional (UV and visible) regions. This predicts the strong potential of the studied alloys for solar cell applications.

Acknowledgement

This research project was supported by a grant from the Research Centre of Female Scientific and Medical Colleges, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University.

References

[1] Z. Zhang, L. Qian, D. Fan, and X. Deng, Appl. Phys. Lett. 60, 419 (1992).10.1063/1.106621Search in Google Scholar

[2] S. Adachi, Properties of Semiconductor Alloys: Group-IV, III-V and II-VI Semiconductors, 1st Edition, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA 2009.10.1002/9780470744383Search in Google Scholar

[3] P. R. Sharps, A. Comfeld, and M. Stan, in: Proceedings of the Photovoltaic Specialists Conference PVSC 08 33 rd IEEE, San Diego, CA, USA 11–16 May 2008 (2008).Search in Google Scholar

[4] A. Luque, A. Marti, and C. Stanley, J. Appl. Phys. 96, 903 (2004).10.1063/1.1760836Search in Google Scholar

[5] L. Yu, D. Li, S. Zhao, G. Li, and K. Yang, Materials 5, 2486 (2012)10.3390/ma5122486Search in Google Scholar

[6] B. Amin, A. Iftikhar, M. Maqbool, S. Goumri-Said, and R. Ahmad, J. Appl. Phys. 109, 023109 (2011).10.1063/1.3531996Search in Google Scholar

[7] A. Laref, A. Altujar, and S. J. Luo, Appl. Phys. A 117, 1451 (2014).10.1007/s00339-014-8573-2Search in Google Scholar

[8] A. Laref, A. Altujar, and S. J. Luo, Sol. Energy 142, 231 (2017).10.1016/j.solener.2016.12.009Search in Google Scholar

[9] A. Laref, Z. Hussain, S. Laref, J. T. Yang, and Y. C. Xiong, J. Phys. Chem. Solids 115, 355 (2018).10.1016/j.jpcs.2017.12.002Search in Google Scholar

[10] P. Blaha, K. Schwarz, G. K. H. Madsen, D. Kvasnicka, and J. Luitz, WIEN2 K: An Augmented Plane Wave and Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties, Vienna University of Technology, Austria 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[11] W. Kohn and L. J. Sham, Phys. Rev. 140, 1133 (1965).10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133Search in Google Scholar

[12] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] A. D. Becke, J. Chem. Phys. 98, 1372 (1993).10.1063/1.464304Search in Google Scholar

[14] M. Ropo, K. Kokko, and L. Vitos, Phys. Rev. B 77, 195445 (2008).10.1103/PhysRevB.77.195445Search in Google Scholar

[15] V. I. Anisimov, J. Zaanen, and O. K. Andersen, Phys. Rev. B 44, 943 (1991).10.1103/PhysRevB.44.943Search in Google Scholar

[16] F. Tran and P. Blaha, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 226401 (2009).10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.226401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] D. Koller, F. Tran, and P. Blaha, Phys. Rev. B 85, 155109 (2012).10.1103/PhysRevB.85.155109Search in Google Scholar

[18] Q. Mahmood and M. Hassan, J. Alloys Comp. 704, 659 (2017).10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.02.097Search in Google Scholar

[19] A. S. Pashinkin and A. S. Malkova, J. Phys. Chem. 77, 1889 (2003).Search in Google Scholar

[20] B. U. Haq, R. Ahmed, A. Shaari, F. E. H. Hassan, and M. B. Kanounc, Sol. Energy 107, 543 (2014).10.1016/j.solener.2014.05.013Search in Google Scholar

[21] H. A. Reshak, Y. S. Mikhail, Y. Saeed, I. V. Kityk, and S. Auluck, J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 2836 (2011).10.1021/jp111382hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] F. Wooten, Optical Properties of Solids, Academic, New York 1972.Search in Google Scholar

[23] N. A. Noor, Q. Mahmood, M. Rashid, U. H. Bakhtiar, and A. Laref, Ceram. Int. 44, 13750 (2018).10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.04.217Search in Google Scholar

[24] D. R. Penn, Phys. Rev. 128, 2093 (1962).10.1103/PhysRev.128.2093Search in Google Scholar

[25] M. M. Cai, Z. Yin, and M. S. Zhang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 2805 (2003).10.1063/1.1616631Search in Google Scholar

[26] K. C. Bhamu, A. Soni, and J. Sahariya, Sol. Energy 162, 336 (2018).10.1016/j.solener.2018.01.059Search in Google Scholar

[27] B. U. Haq, R. Ahmed, and S. Goumri-Said, Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C. 130, 6 (2014).10.1016/j.solmat.2014.06.014Search in Google Scholar

[28] N. Ali, R. Ahmed, B. U. Haq, A. Shaari, and R. Hussain, Sol. Energy 113, 25 (2015).10.1016/j.solener.2014.12.021Search in Google Scholar

[29] S. U. Rehman, F. K. Butt, B. U. Haq, S. AlFaify, and W. S. Khan, Sol. Energy 169, 648 (2018).10.1016/j.solener.2018.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[30] B. U. Haq, R. Ahmed, F. E. H. Hassan, R. Khenata, and M. K. Kasmin, Sol. Energy 100, 1 (2014).10.1016/j.solener.2013.11.020Search in Google Scholar

[31] H. Yao, P. G. Snyder, and J. A. Woollam, J. Appl. Phys. 70, 3261 (1991).10.1063/1.349285Search in Google Scholar

[32] M. Garriga, P. Lautenschlager, M. Cardona, and K. Ploog, Solid State Comm. 61, 157 (1987).10.1016/0038-1098(87)90021-4Search in Google Scholar

[33] G. F. Karavaev, V. N. Chernyshov, and R. M. Egunov, Semiconductors 37, 573 (2003).10.1134/1.1575364Search in Google Scholar

[34] R. L. Sarkar and S. Chatterjee, Phys. Stat. Sol. B 94, 641 (1979).10.1002/pssb.2220940236Search in Google Scholar

[35] L. Yue, X. Chen, Y. Zhang, J. Kopaczek, and J. Shao, Opt. Mater. Express 8, 893 (2018).10.1364/OME.8.000893Search in Google Scholar

[36] N. V. Pavlov and G. G. Zegrya, Semiconductors 48, 1185 (2014).10.1134/S1063782614090188Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Atomic, Molecular & Chemical Physics

- Selenium Zinc Oxide (Se/ZnO) Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity

- Dynamical Systems & Nonlinear Phenomena

- Fluid Flow and Solute Transfer in a Tube with Variable Wall Permeability

- Gravitation & Cosmology

- Gauge Fixing and the Semiclassical Interpretation of Quantum Cosmology

- Hydrodynamics

- Formation of the Capillary Ridge on the Free Surface Dynamics of Second-Grade Fluid Over an Inclined Locally Heated Plate

- Solid State Physics & Materials Science

- Green Zn3Al2Ge2O10: Mn2+ Phosphors: Solid-Phase Synthesis, Structure, and Luminescent Properties

- First Principles Study of Thermodynamic Properties of CdxZn1−xO (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Ternary Alloys

- Elastic and Ultrasonic Studies on RM (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm; M = Zn, Cu) Compounds

- Tailoring of Bandgap to Tune the Optical Properties of Ga1−xAlxY (Y = As, Sb) for Solar Cell Applications by Density Functional Theory Approach

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Atomic, Molecular & Chemical Physics

- Selenium Zinc Oxide (Se/ZnO) Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity

- Dynamical Systems & Nonlinear Phenomena

- Fluid Flow and Solute Transfer in a Tube with Variable Wall Permeability

- Gravitation & Cosmology

- Gauge Fixing and the Semiclassical Interpretation of Quantum Cosmology

- Hydrodynamics

- Formation of the Capillary Ridge on the Free Surface Dynamics of Second-Grade Fluid Over an Inclined Locally Heated Plate

- Solid State Physics & Materials Science

- Green Zn3Al2Ge2O10: Mn2+ Phosphors: Solid-Phase Synthesis, Structure, and Luminescent Properties

- First Principles Study of Thermodynamic Properties of CdxZn1−xO (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Ternary Alloys

- Elastic and Ultrasonic Studies on RM (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm; M = Zn, Cu) Compounds

- Tailoring of Bandgap to Tune the Optical Properties of Ga1−xAlxY (Y = As, Sb) for Solar Cell Applications by Density Functional Theory Approach