Abstract

The present article comprises computation of elastic, ultrasonic, and thermo-physical properties of RM (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm; M = Zn, Cu) compounds at 300 K. The second-order elastic constants (SOECs) and elastic moduli are evaluated initially, using potential model approach considering interaction up to second nearest neighbours. The ultrasonic velocities are obtained for wave propagation along <100>, <110>, and <111> crystallographic directions using evaluated SOECs. The Debye temperature, specific heat at constant volume, thermal energy density, thermal conductivity, and thermal relaxation time are also calculated. The obtained results are compared and analysed for justification and application of materials.

1 Introduction

The intermetallics are homogeneous and composite materials comprising two or more types of metal atoms that differ in structure in comparison to the constituent metals. The binary rare-earth intermetallic compounds (RM; R: rare-earth element, M: transition metal) have many practical applications due to their superior mechanical, thermodynamical, electrical, and magnetic properties in comparison to ordinary metals. These materials possess high strength, ductility, melting point, good corrosion resistance, and low specific heat, which make them important for aerospace and commercial aircraft turbines applications. Most of the rare-earth intermetallic compounds exhibit B2/CsCl-type structure [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. The rare-earth elements have electron occupancy in f-shell with a regular change in atomic dimension and electronegativity on moving along rare-earth group.

The study of binary rare-earth intermetallics represents an important part of the metallic phases [6], [7]. The elastic and mechanical behaviours of rare-earth intermetallic compounds TbCu and TbZn, using first principle calculation have already been reported in literature [1]. Similarly, elastic and mechanical behaviours of Cu- and Zn-based rare-earth binary intermetallic compounds have also been studied using the full-potential augmented plane waves plus local orbital within density-functional theory [3]. The experimental studies of Au-, Ag-, Cu-, and Al-based rare-earth intermetallic compounds are reported elsewhere [2], [6], [7]. The survey of literatures indicates that, despite the technological importance of these rare-earth intermetallics, a systematic theoretical study of structural, elastic, ultrasonic, and thermophysical properties of these materials is still needed for futuristic applications. Therefore, the present work is focused on characterisation of elastic, ultrasonic, and thermophysical properties of RM (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm; M = Zn, Cu) compounds. The second-order elastic constants (SOECs) and elastic moduli (bulk modulus, B; Young’s modulus, Y; shear modulus, G; Lame moduli, λ&μ; B/G ratio; and Poisson ratio, σ) of chosen binary intermetallics have initially been determined using potential model approach considering interaction up to second nearest neighbours. Subsequently, the ultrasonic velocities along three crystallographic directions (<100>, <110>, and <111>) and thermophysical properties (Debye temperature, specific heat at constant volume, thermal energy density, thermal conductivity, and thermal relaxation time) are determined.

2 Theory

2.1 Theory of Elastic Constants

The elastic energy density (F) of undeformed crystal is function of the components of strain tensor (

The elastic energy density (F) can be expanded in terms of strain (η) using Taylor’s series expansion as

The strain derivative of elastic energy density provides the elastic constant of the material. Therefore, the second-order stiffness/elastic constant is defined as

The crystal symmetry of CsCl structured material leads three SOECs (C11,C12, and C44). Using (2) and (3), the free-energy density in square terms of strain can be written as

The elastic energy density (F) at finite temperature (T) is sum of energy density at 0 K and increases in energy (vibrational part of energy density) with enhancement in temperature by amount T [9].

where F0 is the internal energy of unit volume of the crystal when all atoms (ions) are at rest on their lattice points. FVib is the vibrational free-energy density. Thus, SOECs can be separated into two parts.

Here,

where

where e is the electronic charge. The constant Z0 is equal to negative of lattice sum

Here,

Here, y1 and y2 have value equal to r1/b and r2/b, respectively. The SOECs at constant temperature T can be estimated using (6), (7), and (9).

2.2 Mechanical Properties

The compressibility, hardness, brittleness, ductileness, toughness, and bonding nature of the material are well correlated with the elastic constants. Therefore, the mechanical behaviour of a material can be described on the basis of elastic constants. The wave propagation study through solid medium provides a clear relationship between elastic modulus and the SOECs. The SOECs can be utilised in evaluation of bulk modulus (B), shear modulus (G), Young’s modulus (Y), Lame moduli (λ & μ), and Poisson ratio (σ) as they are related as follows [13], [14]:

2.3 Theory of Ultrasonic Velocity

There are three types of ultrasonic velocities for each direction of propagation in cubic crystals; one is longitudinal velocity (VL), and other two are shear velocities (VS1 and VS2) [15], [16]. The expressions for velocities are as follows:

Along <100> crystallographic direction

Along <111> crystallographic direction

Along <110> crystallographic direction

The density of CsCl structured material can be determined by the following expression [17]:

where Mw, NA, a, and n are molecular weight, Avogadro number, lattice parameter, and number of atoms per unit cell, respectively. The Debye average velocity is an important parameter in the low-temperature physics because it is related to SOECs through ultrasonic velocities. The Debye average velocity (VD) is defined as given in literature [18].

The Debye temperature (TD) is indirectly related to elastic constants through the Debye average velocity [19].

Here, h is Planck’s constant, and na is atom concentration. On the propagation of ultrasonic wave, the thermal distribution of phonon will be disturbed. The time taken for re-establishment of equilibrium of the thermal phonons is called the thermal relaxation time (τ) and is given by the following equation:

The quantities κ and CV are the thermal conductivity and specific heat per unit volume of the material, respectively. The specific heat per unit volume is function of TD/T and can be borrowed from literature [19], [20]. The thermal conductivity of CsCl structured material can be determined by the following expression [21]:

where A′ is a constant; δ3 is volume per atom, and γ is Grüneisen parameter. The constant A′ is function of Grüneisen parameter and is given by the following expression:

3 Results and Discussion

The evaluation of SOECs of R–Zn and R–Cu at 300 K has been performed by taking two basic physical quantities (a: lattice parameters and b: nonlinearity parameters). The lattice parameters of chosen materials are taken from the literature [22], and non-linear parameter “b” is determined under equilibrium condition. Both “a” and “b” are shown in Table 1. The density is function of lattice parameters [17]. The densities of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds are calculated using (18) and are given in Table 1. The elastic moduli B, G, Y, σ, λ, and μ are calculated using evaluated SOECs with (11–16). These values are presented in Table 2.

Molecular weight (Mw), lattice parameters (a), nonlinear parameters (b), and density (d) of RM compounds at 300 K.

| Parameters→ Compounds↓ | Mw (g) | a (Å) Ref. [22] | b (Å) | d (103 kg m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TbZn | 224.310 | 3.480 | 0.446 | 8.144 |

| DyZn | 227.890 | 3.460 | 0.428 | 8.358 |

| HoZn | 229.320 | 3.445 | 0.412 | 8.525 |

| ErZn | 232.650 | 3.432 | 0.374 | 8.767 |

| TmZn | 234.320 | 3.414 | 0.336 | 8.957 |

| TbCu | 222.466 | 3.576 | 0.264 | 8.765 |

| DyCu | 226.050 | 3.563 | 0.258 | 9.061 |

| HoCu | 227.466 | 3.547 | 0.254 | 9.229 |

| ErCu | 230.800 | 3.532 | 0.242 | 9.479 |

| TmCu | 232.476 | 3.516 | 0.230 | 9.700 |

Second-order elastic constants, bulk modulus (B), Young’s modulus (Y), shear modulus (G), Lame modulus (λ), B/G ratio, and Poisson ratio (σ) of RM compounds at 300 K.

| Parameters→ Compounds↓ | C11 (GPa) | C12 (GPa) | C44 (GPa) | Y (GPa) | B (GPa) | G or μ (GPa) | λ (GPa) | B/G | σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TbZn | 81.9 | 47.2 | 48.6 | 78.1 | 58.2 | 30.6 | 37.7 | 1.90 | 0.276 |

| [1] | 79.71 | 47.45 | 36.31 | 58.20 | |||||

| DyZn | 84.5 | 47.8 | 49.3 | 80.6 | 59.4 | 31.7 | 38.3 | 1.88 | 0.274 |

| [3] | 84.39 | 38.75 | 33.37 | 73.03 | 53.96 | 28.65 | 1.88 | 0.270 | |

| [26] | 43.38 | ||||||||

| HoZn | 87.5 | 48.7 | 50.3 | 83.4 | 61.0 | 32.3 | 39.1 | 1.89 | 0.272 |

| [3] | 87.97 | 43.73 | 39.58 | 79.76 | 58.47 | 31.33 | 1.87 | 0.270 | |

| [26] | 47.52 | ||||||||

| ErZn | 93.2 | 49.4 | 51.4 | 88.7 | 63.3 | 35.0 | 40.0 | 1.81 | 0.266 |

| [3] | 93.81 | 45.03 | 41.34 | 61.29 | 33.40 | 1.83 | 0.260 | ||

| TmZn | 99.9 | 49.8 | 52.4 | 94.7 | 65.8 | 37.6 | 40.8 | 1.75 | 0.260 |

| TbCu | 117.5 | 49.8 | 54.1 | 109.1 | 71.7 | 43.8 | 42.5 | 1.64 | 0.246 |

| [1] | 113.31 | 46.67 | 36.28 | 69.59 | |||||

| DyCu | 121.3 | 50.8 | 55.3 | 112.5 | 73.6 | 45.2 | 43.5 | 1.63 | 0.245 |

| [3] | 122.61 | 52.08 | 33.91 | 89.71 | 75.59 | 34.44 | |||

| [26] | 39.1 | ||||||||

| [27] | 38.66 | 72.7 | |||||||

| HoCu | 124.1 | 51.5 | 56.2 | 114.9 | 74.9 | 46.2 | 44.2 | 1.62 | 0.244 |

| [3] | 124.2 | 55.36 | 36.58 | 92.96 | 78.30 | 35.69 | |||

| ErCu | 129.3 | 51.7 | 56.9 | 118.9 | 76.8 | 47.9 | 44.9 | 1.60 | 0.242 |

| [3] | 129.71 | 61.77 | 38.54 | 96.03 | 84.41 | 36.64 | |||

| TmCu | 135.4 | 52.1 | 57.9 | 123.7 | 79.1 | 49.9 | 45.8 | 1.59 | 0.239 |

A perusal of Table 2 indicates that our evaluated SOECs, bulk modulus, Young’s modulus, shear modulus, Lame moduli, B/G, Poisson ratio of R–Zn and R–Cu at 300 K is approximately the same as given in literature [1], [3]. The Born structural stability criterion for a crystal lattice is

If toughness/fracture ratio (G/B) ≤ 0.57 or fracture/toughness ratio (B/G) ≥ 1.75, then the material will have ductile character [26]. The B/G ratio of R–Zn intermetallics compounds is found greater than 1.75 (Tab. 2) and is received to decrease as R varies from Tb to Tm. Therefore, R–Zn intermetallic compounds will have ductile/covalent character. The reduction in B/G ratio with variation of R from Tb to Tm reveals an increase in ionic/brittleness nature. As intermetallics R–Cu possess a slightly lower value of B/G to the transition/critical value of fracture/toughness ratio, these intermetallics will have least ductility and high ionic character in comparison to R–Zn intermetallic compounds. The nature of bonding among the atoms of a material (ionic, covalent and metallic) can also be understood on the basis of Poisson’s ratio. The bonding forces among atoms are non-central for σ ∼ 0–0.25 and are central for σ ∼ 0.25–0.50 [28]. The Poisson ratio of R–Zn is received greater than 0.25, while slightly lower value of σ is obtained for R–Cu intermetallics (Tab. 2). Thus, the bonding in R–Zn intermetallics will be more central and covalent in nature, while bonding in R–Cu intermetallics will be comparatively ionic or non-central in nature.

The ultrasonic velocities are evaluated with the help of SOECs and densities of the chosen materials using (17–19) for ultrasonic for wave propagation along <100>, <110>, and <111> crystallographic directions. The calculated ultrasonic velocities are shown in Table 3. As C11 is found to be greater than C12 or C44 for all materials under study, the longitudinal ultrasonic velocities are obtained large than that of shear ultrasonic velocity for each direction of propagation (Tab. 3). The ultrasonic velocities of R–Cu compounds are found large in comparison to R–Zn compounds in all crystallographic directions. This is due to the relatively high elastic constants of R–Cu compounds in comparison to R–Zn compounds. As the elastic constants of RM compounds increase with variation of R from Tb to Tm, the velocities in RM compounds are found to increase as R varies from Tb to Tm and are given in Table 3. Due to very small variation in densities of RM compounds (Tab. 1), they do not predominantly affect the ultrasonic velocities. The large ultrasonic velocity for propagation of ultrasonic wave along <111> direction in comparison to propagation along <100> and <110> directions shows that the direction of symmetry in such compounds is <111>. The longitudinal ultrasonic velocities of RM compounds have been compared with literature for wave propagation along <100> crystallographic direction [3], which are found very close to each other. However, a slight variation in shear ultrasonic wave velocity is obtained with respect to reported values [3]. The reason behind it is that the shear wave velocity is predominantly affected by C44, which was underestimated in literature [3] in comparison to present (Tab. 2) and experimental values [26], [27]. Thus, our evaluated velocities are justified.

The ultrasonic velocities (103 ms−1) and thermal relaxation time (τ in ps) of RM compounds along <100>, <110>, and <111> at 300 K.

| Compounds→ Parameters↓ | Direction | TbZn | DyZn | HoZn | ErZn | TmZn | TbCu | DyCu | HoCu | ErCu | TmCu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VL | <100> | 3.171 | 3.180 | 3.203 | 3.259 | 3.339 | 3.661 | 3.659 | 3.667 | 3.693 | 3.737 |

| [3] | 3.249 | 3.350 | 3.415 | 3.670 | 3.682 | 3.749 | |||||

| VS | 2.442 | 2.429 | 2.430 | 2.421 | 2.419 | 2.485 | 2.470 | 2.466 | 2.449 | 2.442 | |

| [3] | 1.812 | 1.873 | 1.919 | 1.954 | 1.961 | 1.966 | |||||

| VD | 2.557 | 2.568 | 2.572 | 2.573 | 2.580 | 2.676 | 2.663 | 2.660 | 2.646 | 2.643 | |

| [3] | 2.017 | 2.085 | 2.136 | 2.183 | 2.191 | 2.199 | |||||

| τ | 17.960 | 17.148 | 16.23 | 13.762 | 10.970 | 5.975 | 5.742 | 5.579 | 5.017 | 4.392 | |

| VL | <110> | 3.726 | 3.717 | 3.726 | 3.741 | 3.769 | 3.964 | 3.950 | 3.949 | 3.943 | 3.954 |

| VS1 | 2.442 | 2.429 | 2.430 | 2.422 | 2.419 | 2.485 | 2.470 | 2.466 | 2.449 | 2.442 | |

| VS2 | 1.460 | 1.482 | 1.509 | 1.581 | 1.672 | 1.964 | 1.973 | 1.983 | 2.022 | 2.072 | |

| VD | 1.919 | 1.939 | 1.966 | 2.036 | 2.120 | 2.384 | 2.386 | 2.393 | 2.415 | 2.447 | |

| τ | 32.393 | 30.699 | 27.83 | 21.983 | 16.252 | 7.527 | 7.152 | 6.894 | 6.024 | 5.124 | |

| VL | <111> | 3.894 | 3.878 | 3.885 | 3.888 | 3.902 | 4.061 | 4.042 | 4.039 | 4.023 | 4.024 |

| VS | 1.846 | 1.852 | 1.867 | 1.903 | 1.953 | 2.151 | 2.151 | 2.156 | 2.174 | 2.203 | |

| VD | 2.052 | 2.058 | 2.073 | 2.111 | 2.164 | 2.375 | 2.374 | 2.379 | 2.397 | 2.426 | |

| τ | 28.340 | 26.706 | 25.04 | 20.442 | 15.604 | 7.585 | 7.222 | 6.972 | 6.116 | 5.216 |

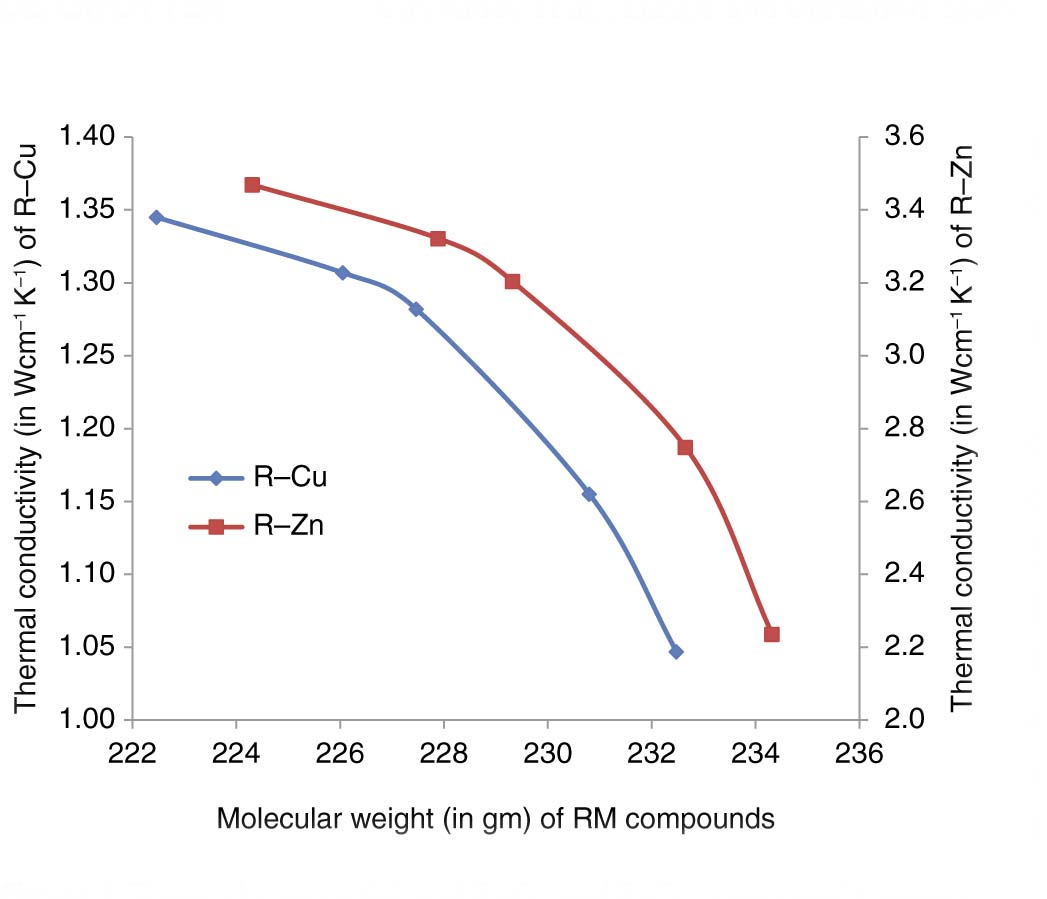

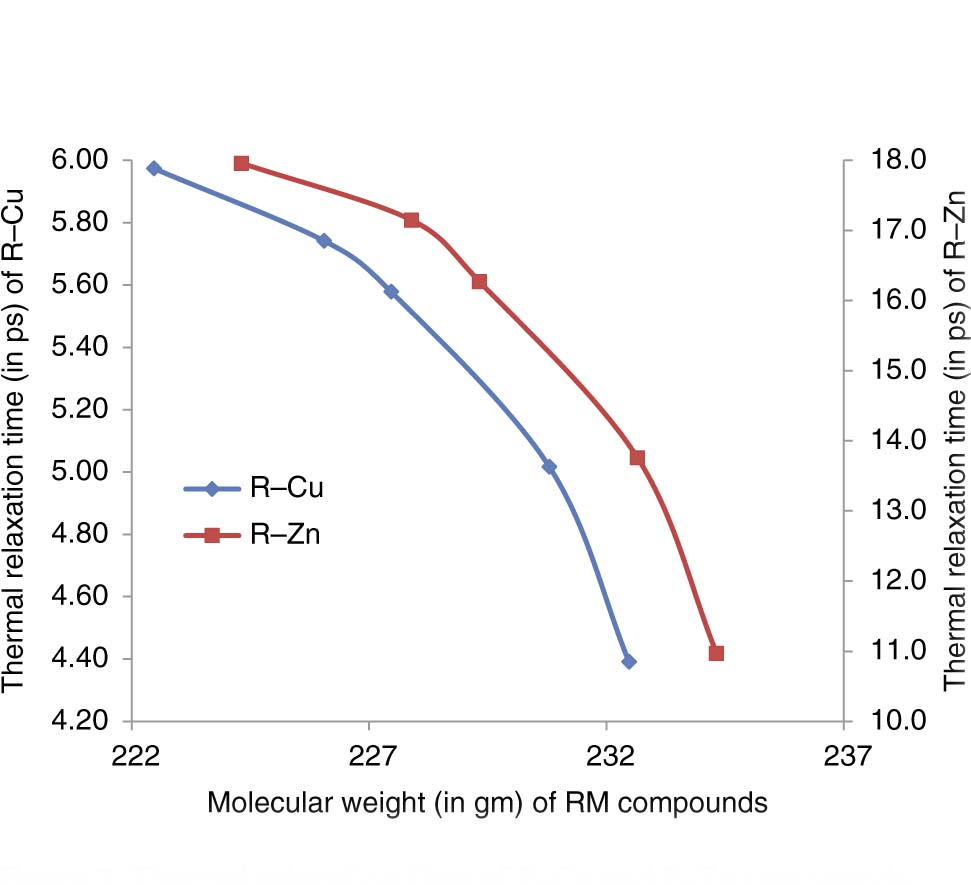

The Debye average velocity (VD) and Debye temperature (TD) are calculated using (19, 20). The specific heat at constant volume (CV) and thermal energy density (E0) are evaluated with the TD/T table given in the AIP Handbook [20]. Thermal relaxation time (τ), thermal conductivity (k), and Grüneisen parameter (γ) are calculated using (19–22). The obtained values of TD, CV, E0, k, and γ are depicted in Table 4. The variations of the thermal conductivity and thermal relaxation time of R–Zn and R–Cu with molecular weights are also shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The Debye temperature (TD) in (K), specific heat at constant volume (CV) in (105 Jm−3 K−1), thermal energy density (E0) in (108 Jm−3), Grüneisen parameter (γ), and thermal conductivity (κ) in (Wcm−1 K−1) of RM compounds at 300 K.

| Compounds→ Parameters ↓ | TbZn | DyZn | HoZn | ErZn | TmZn | TbCu | DyCu | HoCu | ErCu | TmCu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD | 273.9 | 273.8 | 275.5 | 276.8 | 279.0 | 292.2 | 292.4 | 293.3 | 293.0 | 294.2 |

| Cv | 8.722 | 8.811 | 8.931 | 9.053 | 9.183 | 9.465 | 9.629 | 9.747 | 9.867 | 10.24 |

| E0 | 1.915 | 1.934 | 1.961 | 1.988 | 2.016 | 2.078 | 2.114 | 2.14 | 2.166 | 2.201 |

| γ | 0.432 | 0.461 | 0.487 | 0.487 | 0.660 | 0.903 | 0.924 | 0.937 | 0.989 | 1.044 |

| κ | 3.469 | 3.322 | 3.204 | 2.749 | 2.236 | 1.345 | 1.307 | 1.282 | 1.155 | 1.047 |

Thermal conductivity of R–Cu and R–Zn compounds versus molecular weight.

Thermal relaxation time of R–Cu and R–Zn compounds versus molecular weight.

A perusal of Table 3 indicates that our estimated Debye average velocity of chosen compounds for wave propagation along <100> direction is found very close to reported values in literature [3]. A small difference between present and reported Debye average velocity is evinced by less estimation of shear velocity or C44 in literature [3] in comparison to present and experimental values [26], [27]. Therefore, our computation for VD has been justified in these materials. The ultrasonic wave will propagate with low hindrance and highest speed in R–Zn/Cu along axial direction as the Debye average velocity is obtained maximum along <100> direction (Tab. 3). As the number of atoms involved in the momentum transfer for wave propagation along axial direction is less than that in the nonaxial direction (<110>, <111>) in B2 structured materials, due to low energy dissipation and high stiffness along axial direction, the phonon of maximum frequency will propagate with maximum speed. The Debye average velocities of chosen intermetallic compounds are found to increase from TbZn to TmCu, and TD is proportional to VD. Hence, the Debye temperature has been found to increase from TbZn to TmCu, given in Table 4. The Debye temperatures of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds change by 1.9 % and 0.6 %, respectively, as R varies from Tb to Tm. As the specific heat at constant volume and thermal energy density is function of TD/T, they are also found to increase in the same manner. The variations in specific heat at constant volume and thermal energy density of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds have been found between 5 % and 9 % as R varies from Tb to Tm. The Grüneisen parameters are directly related to square of SOECs [18], and SOECs are found to increase in chosen compounds from TbZn to TmCu (Tab. 4); thus, the Grüneisen parameters are found to increase. The Grüneisen parameters of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds change by 52.8 % and 15.6 %, respectively, as R varies from Tb to Tm in chosen compounds. This indicates that there will be decrease in phonon frequency with volume and increase in nonlinearity of restoring force among the atoms of compounds R–Zn and R–Cu as R varies from Tb to Tm in RM compounds.

The thermal conductivity of chosen compounds is found to decrease from TbZn to TmCu in Table 3, and its variation with molecular weight for R–Zn and R–Cu compounds decreases as R varies from Tb to Tm, as shown in Figure 1. The change in the thermal conductivity of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds is received to be 35.6 % and 22.2 %, respectively, as R varies from Tb to Tm. The value of A′/γ2 is more effective in the decreasing of the thermal conductivity than

The thermal relaxation time in R–Zn and R–Cu has been decreased as R varies from Tb to Tm in RM compounds, and it resembles the similar variation with molecular weight as followed by thermal conductivity shown in Figure 2. The re-establishment (τ) of thermal phonon for R–Cu is found comparatively smaller than that for R–Zn compounds. The thermal relaxation time is well correlated with the thermal conductivity, Debye average velocity, and specific heat of material (τ ∝

4 Conclusion

On the basis of the above discussion, we conclude that our potential model approach theory for evaluation of SOECs is justified for RM compounds. These intermetallics have stable B2-type crystal structure as they follow the Born stability criterion. The elastic moduli, density, Debye average velocity, Debye temperature, specific heat per unit volume, thermal energy density, and the Grüneisen parameters of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds are found to increase as R varies from Tb to Tm in RM compounds. As the elastic moduli of R–Cu are larger than R–Zn compounds, the elastic and ultrasonic behaviour of R–Cu compounds is found to be better than R–Zn compounds. The direction of symmetry in these intermetallics is <111> as the longitudinal velocity is found maximum along this direction for all these intermetallics. Yet, the bonding between the atoms of R–Cu compounds is not found more covalent in nature as found for R–Zn, but the application of R–Cu compounds will be better than R–Zn due to their high elastic strength, low density, and high average sound speed in axial direction. The thermal conductivity and thermal relaxation time of R–Zn and R–Cu compounds decrease with the increase in their molecular weight and also as R varies from Tb to Tm in RM compounds. The thermal conductivity of chosen intermetallic compounds is found to be predominantly affected by the Grüneisen parameter, while thermal relaxation time is mainly influenced by the thermal conductivity. Hence, the obtained results provide a good understanding of the elastic, mechanical, thermal, and ultrasonic properties of chosen rare-earth intermetallic compounds that may be used for further investigation and also in material manufacturing industries. In addition, the model established here can also be utilised for the elastic and ultrasonic study of other CsCl structured materials.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their high gratitude to Prof. R. R. Yadav, Vice Chancellor, V. B. S. Purvanchal University, Jaunpur and Dr. Satish Chandra, P.P.N. (P.G.) College, Kanpur for their valuable discussion and support during the course of manuscript preparation. The authors are highly thankful to Dr. Suman Singh, Department of English, P.P.N. (P.G.) College, Kanpur for her support regarding language improvement of the manuscript. The authors are highly thankful to reviewers for their valuable comments to enhance the quality of the article.

References

[1] R. Wang, S. Wang, and X. Wu, Intermetallics 43, 65 (2013).10.1016/j.intermet.2013.07.008Search in Google Scholar

[2] K. A. Gschneidner Jr, A. M. Russell, A. O. Pecharsky, J. R. Morris, Z. Zhang, et al., Nat. Mater. 2, 587 (2003).10.1038/nmat958Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] R. P. Singh, V. K. Singh, R. K. Singh, and M. Rajagopalan, Am. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 3, 123 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[4] A. M. Russell, Adv. Engg. Mat. 5, 629 (2003).10.1002/adem.200310074Search in Google Scholar

[5] A. M. Russell, Z. Zhang, T. A. Lograsso, C. H. C. Lo, A. O. Pecharsky, et al., Acta Mater. 52, 4033 (2004).10.1016/j.actamat.2004.05.019Search in Google Scholar

[6] K. H. J. Buschow and J. H. N. van Vucht, Philips Res. Rep. 22, 233 (1967).Search in Google Scholar

[7] J. P. McDonald, M. A. Rodriguez, E. D. Jones, and D. P. Adams, J. Mat. Res. 25, 718 (2010).10.1557/JMR.2010.0091Search in Google Scholar

[8] K. Brugger, Phys. Rev. 133, A1611 (1964).10.1103/PhysRev.133.A1611Search in Google Scholar

[9] D. Singh, V. Bhalla, J. Bala, and S. Wadhwa, Z. Naturforsch. 72, 977 (2017).10.1515/zna-2017-0217Search in Google Scholar

[10] S. Mori and Y. Hiki, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 45, 1449 (1978).10.1143/JPSJ.45.1449Search in Google Scholar

[11] P. B. Ghate, Phys. Rev. A 139, 1666 (1965).10.1103/PhysRev.139.A1666Search in Google Scholar

[12] R. R. Yadav and D. K. Pandey, Acta Phys. Pol. A 107, 933 (2005).10.12693/APhysPolA.107.933Search in Google Scholar

[13] M. Moakafi, R. Khenata, A. Bouhemadou, F. Semari, A. H. Reshak, et al., Comput. Mat. Sci. 46, 1051 (2009).10.1016/j.commatsci.2009.05.011Search in Google Scholar

[14] F. Kalarasse, L. Kalarasse, B. Bennecer, and A. Mellouki, Comput. Mat. Sci. 47, 869 (2010).10.1016/j.commatsci.2009.11.016Search in Google Scholar

[15] S. L. Kakani and C. Hemrajani, Solid State Physics, Sultan Chand & Sons, New Delhi 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[16] R. Truell, C. Elbaum, and B. B. Chick, Ultrasonic Methods in Solid State Physics, Academic Press, New York 1969.Search in Google Scholar

[17] S. O. Pillai, in: Solid State Physics: Crystal Physics, 7th ed., New Age International Publishers, New Delhi 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[18] D. K. Pandey and S. Pandey, in: Acoustic Waves: Ultrasonic: A Technique of Material Characterization (Ed. D. W. Dissanayake), Scio Publisher, Croatia 2010, p. 397.Search in Google Scholar

[19] C. Kittel, Introduction to Solid State Physics, 7th ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[20] D. E. Gray, AIP Handbook, 3 rd ed., McGraw Hill Co. Inc., New York 1956, pp. 4–44, 4–57.Search in Google Scholar

[21] D. T. Morelli and G. A. Slack, High Lattice Thermal Conductivity Solids in High Thermal Conductivity of Materials (Eds. S. L. Shinde, J. Goela J). XVIII ed., Springer, New York 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[22] C. C. Chao, H. L. Luo, and P. Duwez, J. Appl. Phys. 35, 257 (1964).10.1063/1.1713089Search in Google Scholar

[23] P. K. Yadawa, D. Singh, D. K. Pandey, and R. R. Yadav, Open Acoust. J. 2, 61 (2009).10.2174/1874837600902010061Search in Google Scholar

[24] T. Kraft and P. M. Marcus, Phys. Rev. B 48, 5886 (1993).10.1103/PhysRevB.48.5886Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] H. M. Ledbetter, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 6, 1181 (1977).10.1063/1.555564Search in Google Scholar

[26] E. P. Wohalfarth and K. H. J. Buschow, Handbook of Ferromagnetic Materials, Elsevier B. V., Amsterdam 1990, p. 5.Search in Google Scholar

[27] M. Yasui, T. Terai, T. Kakeshita, and M. Hagiwara, J. Phys. Conf. Series 165, 012059 (2009).10.1088/1742-6596/165/1/012059Search in Google Scholar

[28] V. Bhalla, D. Singh, S. K. Jain, and R. Kumar, Pramana J. Phys. 86, 1355 (2016).10.1007/s12043-015-1183-5Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Atomic, Molecular & Chemical Physics

- Selenium Zinc Oxide (Se/ZnO) Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity

- Dynamical Systems & Nonlinear Phenomena

- Fluid Flow and Solute Transfer in a Tube with Variable Wall Permeability

- Gravitation & Cosmology

- Gauge Fixing and the Semiclassical Interpretation of Quantum Cosmology

- Hydrodynamics

- Formation of the Capillary Ridge on the Free Surface Dynamics of Second-Grade Fluid Over an Inclined Locally Heated Plate

- Solid State Physics & Materials Science

- Green Zn3Al2Ge2O10: Mn2+ Phosphors: Solid-Phase Synthesis, Structure, and Luminescent Properties

- First Principles Study of Thermodynamic Properties of CdxZn1−xO (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Ternary Alloys

- Elastic and Ultrasonic Studies on RM (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm; M = Zn, Cu) Compounds

- Tailoring of Bandgap to Tune the Optical Properties of Ga1−xAlxY (Y = As, Sb) for Solar Cell Applications by Density Functional Theory Approach

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Atomic, Molecular & Chemical Physics

- Selenium Zinc Oxide (Se/ZnO) Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity

- Dynamical Systems & Nonlinear Phenomena

- Fluid Flow and Solute Transfer in a Tube with Variable Wall Permeability

- Gravitation & Cosmology

- Gauge Fixing and the Semiclassical Interpretation of Quantum Cosmology

- Hydrodynamics

- Formation of the Capillary Ridge on the Free Surface Dynamics of Second-Grade Fluid Over an Inclined Locally Heated Plate

- Solid State Physics & Materials Science

- Green Zn3Al2Ge2O10: Mn2+ Phosphors: Solid-Phase Synthesis, Structure, and Luminescent Properties

- First Principles Study of Thermodynamic Properties of CdxZn1−xO (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Ternary Alloys

- Elastic and Ultrasonic Studies on RM (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm; M = Zn, Cu) Compounds

- Tailoring of Bandgap to Tune the Optical Properties of Ga1−xAlxY (Y = As, Sb) for Solar Cell Applications by Density Functional Theory Approach