Abstract

The effects of halogen element X (X = Br, I) doping on the geometrical structures and electronic properties of neutral aluminium clusters are systematically studied by utilising the density functional theory calculations. The structures of X-doped clusters show the three-dimensional forms with increasing atomic number except for n = 3 and X (X = Br, I) atom prefer to occupy the surface site of the host Aln clusters. BrAl7 and IAl7 clusters are the most stable geometries. The HOMO-LUMO energy gap and chemical hardness show an odd–even alternative phenomenon. The charges always transfer from the Al atoms to the X (X = Br, I) atom. Finally, the dipole and polarisability are discussed.

1 Introduction

The study of the structural, electronic, and optical properties of aluminium clusters has become a hot topic both theoretical and experimental in the past few decades. One of the major motivations behind these researches is that the pure and impurity-doped aluminium clusters have highly promising applications in modern molecular science [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Based on anion photoelectron spectra (PES), Nakajima et al. [8] studied the geometric and electronic properties of AlnS−1 clusters. Using the PES, Pramann et al. [9] explored the structure of AlnCo−1 (n = 8–17) clusters. Rao and Jena [10] investigated the nature of bonding of AlnC clusters using density functional theory (DFT) and found that the C appears different bonding behaviour in AlnC clusters according to their size and charge state. Sun et al. [11] studied the structural and electronic properties of AlnBe (n = 1–13) using the B3LYP/aug-cc-pVDZ method, the result of which has shown that Al6Be is the most stable one among these clusters. Guo [12] reported a spin-polarised DFT study of the structures of AlnAs (n = 1–15), where the As atom is found to occupy the peripheral position. Torres et al. [13] performed a DFT study on the structural and electronic properties of AlnTi+ (n = 16–21) clusters as well as the adsorption of an Ar atom on them and found that the n = 21 is the critical size for the encapsulation of Ti in the AlnTi+ clusters. Li et al. [14] have found that in the Cu-doped Aln clusters AlnCu (n = 1–19) only the Al12Cu, Al19Cu, and Al17Cu2 clusters exhibit magnetic property. Xing et al. [15] calculated the geometrical and electronic structures of AlnMg0,−1 (n = 3–20) clusters, whose results show that the Al6Mg cluster exhibits an excellent stability in accordance with the jellium model predictions.

The computed values of bond lengths r(Å) and vibrational frequencies ω(cm−1) of Al2, Br2, I2, AlBr, and AlI dimers at different levels, together with the experimental (Exp.) data for comparison.

| Clusters | Para. | Method | Exp. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3PW91 | BP86 | PBE | PW91 | B3LYP | |||

| Al2 | r | 2.484 | 2.499 | 2.492 | 2.491 | 2.763 | 2.701a |

| ω | 344.55 | 334.09 | 341.68 | 340.42 | 253.77 | 286a | |

| Br2 | r | 2.491 | 2.519 | 2.511 | 2.512 | 2.510 | 2.672b |

| ω | 277.81 | 264.8 | 267.41 | 267.52 | 270.44 | 281.011c | |

| I2 | r | 2.839 | 2.869 | 2.859 | 2.860 | 2.863 | 3.022d |

| ω | 187.64 | 178.71 | 181.16 | 181.12 | 181.39 | 125.69d | |

| AlBr | r | 2.359 | 2.377 | 2.372 | 2.370 | 2.370 | 2.318e |

| ω | 350.49 | 340.32 | 344.05 | 344.31 | 342.69 | 297.2e | |

| AlI | r | 2.584 | 2.600 | 2.594 | 2.592 | 2.582 | 2.543f |

| ω | 296.85 | 288.89 | 292.78 | 292.43 | 286.68 | 316.1f | |

Although the results of above studies provide new approaches to explore the geometrical structures and electronic properties for the impurity-doped Aln clusters, relatively few theoretical reports are available on the halogen element-doped Aln clusters. Bergeron et al. [16] revealed the role of Aln cluster superatoms as halogens in polyhalides and as alkaline earths in iodide salts. Sun et al. [17] investigated the structures and electronic properties Al7X0,−1 and Al13X1,2,12−1 (X = F, Cl, and Br) clusters and found that the NBO charges of Cl and Br have similar properties, but much different from Han and Jung [18], who systematically studied the existence of superatoms in halogenated aluminium clusters. The research priority is to observe the behaviour of Al13,14 in MX1,2 clusters (M = Al11–15, X = F, Cl, Br, I). However, there is no detailed study into Aln clusters doped with X (X = Br, I) atoms until recently. In this article, we perform a DFT study of the impurities-doped aluminium clusters (XAln; X = Br, I; n = 3–15) to explore their structural and electronic properties. The growth behaviour, stabilities, HOMO-LUMO gaps, charge transfer, chemical hardness, polarisabilities, and dipole moment have been analyzed and discussed. We hope that this work can provide valuable information for understanding the physical and chemical properties of small Aln cluster doped with halogen element and can offer relevant theory basis for subsequent experimental and theoretical studies.

2 Computational Methods

In order to search the lowest-energy XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters, a large amount of initial structures including one-, two-, and three-dimensional (3D) configurations are considered using the following ways: (i) many previous researches of pure Aln [6], [19], [20] and MAln [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] clusters are first used as a guide and (ii) capping or placing X (X = Br, I) atom at various sites of the Aln clusters as well as substituting one M atom by the X (X = Br, I) atom from the MAln. Through these methods, a lot of isomers for XAln cluster are obtained. Then these isomers are further optimised using the DFT method with the hybrid B3LYP functional, as implemented in the Gaussian 09 program [26]. The effective core potential LANL2DZ basis set for the X (X = Br, I) atom and the full electron 6−311 + G(d) basis set for Al atom are chosen. The effects of the spin polarisation have been taken into account, and no symmetry constraints are performed in the geometry optimisation. In addition, the vibrational frequency calculations are performed at the same level theory to ensure the nature of the stationary points. The calculated vibrational frequencies are summarized in Tables S1–S2 of the supplementary material. Their positive values show that the calculated structures correspond to true minima. It is not easy to say that the obtained isomers are the lowest-energy structures, because of a lack of experimental data. But because the size of XAln clusters is small, the number of isomers for each cluster size is rather limited. So, we can be sure that the optimised structures correspond to a local minimum.

To ensure the accuracy of the calculation method, the bond length r(Å) and frequency ω(cm−1) of Al2, Br2, I2, BrAl, and IAl dimers are first calculated using different functions (B3PW91 [27], [28], [29], BP86 [30], [31], PBE [32], PW91 [27], [28], and B3LYP [27], [33]). The results with experimental value [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39] are summarized in Table 1. From Table 1, it is easy to find that the r and ω calculated from the B3LYP functional agree with experimental results well. Therefore, the B3LYP functional is adopted in the current study.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Structures

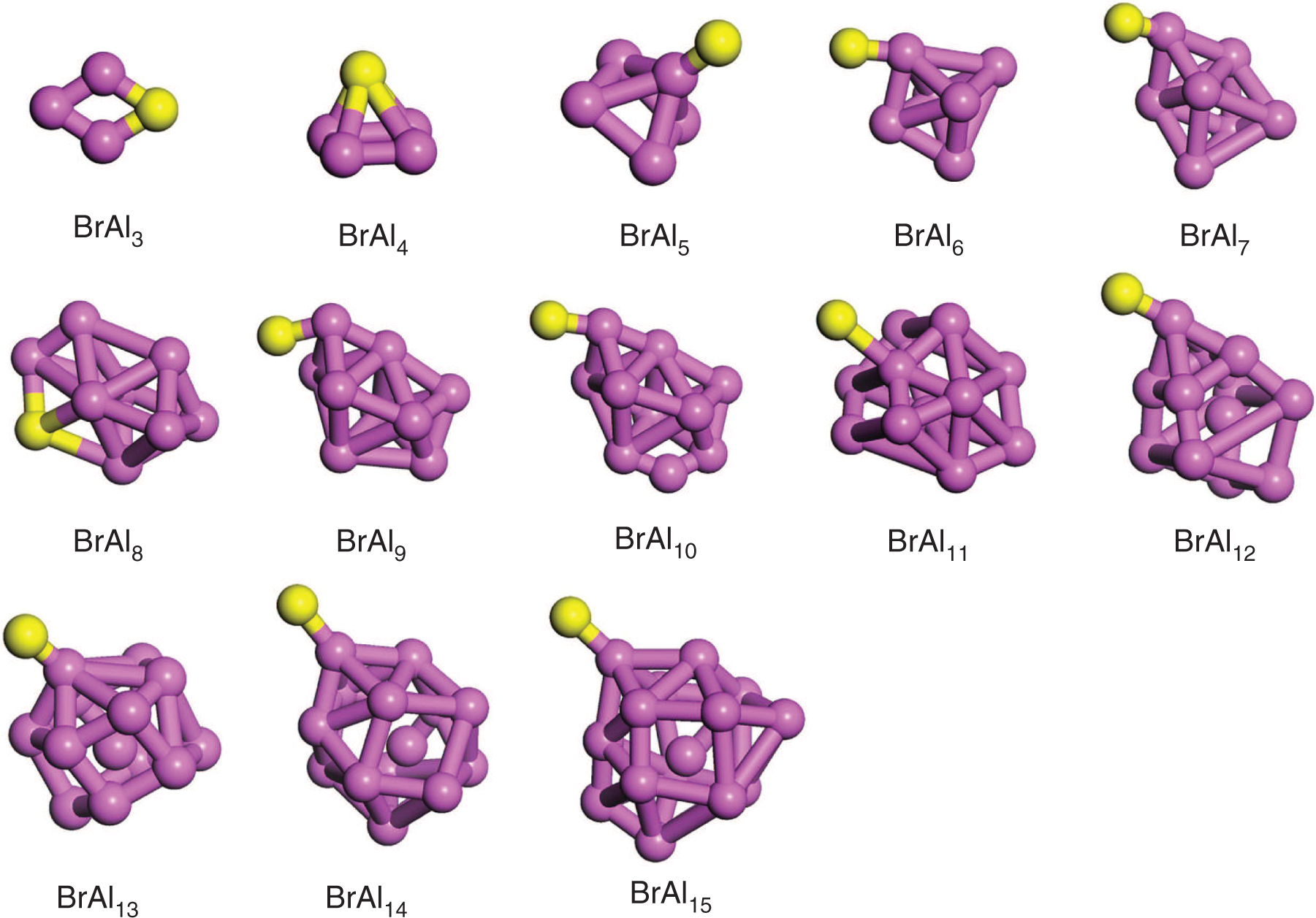

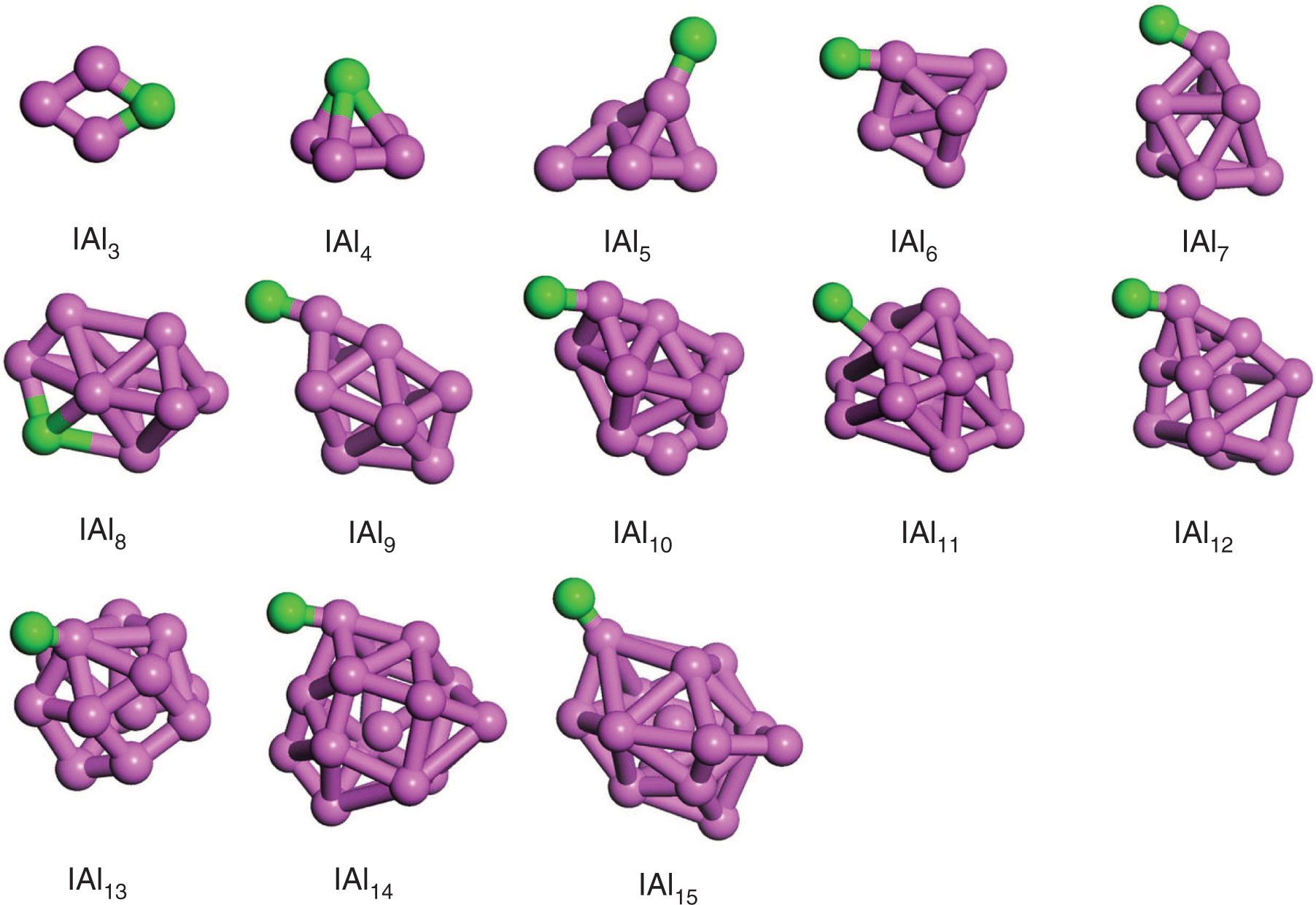

The lowest-energy structures of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) cluster are plotted in Figures 1 and 2, and the corresponding electronic state and symmetry are listed in Table 2. Other metastable isomers of XAln clusters are shown in Figures S1–S2. The average bond lengths of Al–Br, Al–I, and Al–Al bond are also calculated and listed in Table S3.

The ground-state structures of BrAln (n = 3–15) clusters. Purple and yellow balls represent Al and Br atoms, respectively.

The ground-state structures of IAln (n = 3–15) clusters. Purple and green balls represent Al and I atoms, respectively.

The geometric symmetry, electronic state, averaged binding energy Eb (eV), second-order energy difference Δ2E (eV), and HOMO-LUMO energy gaps Egap (eV) of the lowest-energy XAlnu (n = 3–15; X = Br, I) clusters.

| n | BrAln | n | IAln | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Sym | Eb | Δ2E | Egap | State | Sym | Eb | Δ2E | Egap | ||

| 3 | 3A′ | Cs | 1.60 | −0.60 | 1.51 | 3 | 3A1 | C2v | 1.47 | −0.72 | 1.64 |

| 4 | 2A′ | Cs | 1.66 | −0.42 | 1.46 | 4 | 2A | C4 | 1.58 | −0.18 | 1.40 |

| 5 | 1A′ | Cs | 1.78 | 0.46 | 2.01 | 5 | 1A′ | Cs | 1.69 | 0.30 | 2.01 |

| 6 | 2A | C1 | 1.79 | −1.64 | 1.53 | 6 | 2A | C1 | 1.72 | −1.59 | 1.42 |

| 7 | 1A | C1 | 2.01 | 2.02 | 2.63 | 7 | 1A | C1 | 1.94 | 1.98 | 2.62 |

| 8 | 2A′ | Cs | 1.95 | −0.58 | 1.33 | 8 | 2A | C1 | 1.89 | −0.58 | 1.36 |

| 9 | 1A | C1 | 1.97 | −0.16 | 1.79 | 9 | 1A | C1 | 1.91 | −0.15 | 1.84 |

| 10 | 2A | C1 | 1.99 | 0.04 | 1.30 | 10 | 2A | C1 | 1.94 | 0.02 | 1.30 |

| 11 | 1A′ | Cs | 2.01 | −0.11 | 1.79 | 11 | 1A | C1 | 1.97 | −0.08 | 2.00 |

| 12 | 2A | C1 | 2.04 | −0.68 | 1.18 | 12 | 2A | C1 | 1.99 | −0.72 | 1.88 |

| 13 | 1A′ | Cs | 2.10 | 0.55 | 2.28 | 13 | 1A | C1 | 2.07 | 0.59 | 2.36 |

| 14 | 2A | C2 | 2.13 | 0.66 | 1.38 | 14 | 2A | C2 | 2.09 | 0.65 | 1.43 |

| 15 | 1A | C1 | 2.11 | 1.72 | 15 | 1A | C1 | 2.07 | 1.92 | ||

For BrAln (n = 3–15) clusters, only the BrAl3 cluster is planar structures. For n ≥ 4, it is easy to see that the most stable structures have 3D configurations. The lowest-energy structure BrAl3 is a rhombus, with bond lengths of Al–Br and Al–Al being 2.66 and 2.73 Å, respectively. This structure is similar to the most stable structure of Al3Zn and Al3Mg [24], [25]. At n = 4, the ground-state BrAl4 is a derived geometry of BrAl3 structure after one Br atom is capped on it, which resembles the most stable structures of Al4As and Al4P [12], [23]. The average bond lengths of Al–Al and Al–Br are 2.58 and 2.34 Å, respectively. For n = 5, the lowest-energy structure BrAl5 shows a similar structure to the ground-state Al5As, Al5Mg, and Al5P [12], [15], [23] clusters with average Al–Al and Al–Br bond lengths of 2.84 and 2.41 Å. When one Al atom is capped on the quadrangular face of BrAl5, the most stable structure of BrAl6 is generated, which is similar to the lowest-energy isomer of Al6As, Al6P, and Al6Mg [12], [15], [23]. This structure has average bond lengths of 2.64 and 2.34 Å for Al–Al and Al–Br, respectively. The most stable geometries of BrAl7, BrAl8, BrAl9, and BrAl10 can be considered as the newly proposed BrAl6 cluster capped with a variable number of Al atoms (1, 2, 3, and 4) on the surface. These structures are similar to the ground-state structures of Al7Mg, Al7X (X = F, Cl), Al8Be, Al9Zn, and Al10Mg [15], [17], [11], [24], [15], respectively. The Al–Br bond length varies in the range 2.32–2.33 Å, and Al–Al bond length has increased to 2.74 Å. In the case of BrAl11, the ground-state isomer is obtained when Br atom is capped on a cage-shape Al11 cluster. The Al–Br average bond length is 2.36 Å, and Al–Al average bond length is 2.71 Å. For n = 12, the 3D structure BrAl12 is a generated by capping one Br atom on the top of an Al-centred cage structure Al12. The average bond lengths of Al–Al and Al–Br are found to be 2.69 and 2.33 Å, respectively. The cubic structure of BrAl13 in which one Al encapsulated into the centre of a bicapped pentaprism Al13 is calculated to be the most stable isomer, which is similar to the ground-state Al13Br [18] cluster. The average bond length between Al and Br atom is 2.34 Å, and that between Al atoms is 2.76 Å. As for BrAl14 cluster, the ground-state isomer is a stereoscopic structure in which one Al atom is encapsulated into the cluster. This structure has been reported as lowest-energy for Al14Br [18]. The Al–Br average bond length is 2.34 Å, whereas the Al–Al average bond length is 2.77 Å. When one Al atom is capped on the bottom of BrAl14, the derived structure BrAl15 is generated. The average bond lengths of Al–Br and Al–Al bond are 2.35 and 2.78 Å, respectively.

For IAln (n = 3–15) clusters, it is easy to find that the most stable IAln clusters adopt 3D geometries with the lowest spin multiplicity for 4 ≤ n ≤ 15, and most of them are similar to the corresponding BrAln clusters with the exception of n = 5. This may be the result from the bromine and iodine atoms being a similar electronic structure. From Figure S1–S2, one can find that most of the metastable isomers of IAln clusters are consistent with the corresponding BrAln clusters.

Through the analyses above, one can see that the XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters favour the 3D structures from n = 4. The X (X = Br, I) atom prefers to occupy the surface site of the host Aln clusters, which is similar to the structure of AlnAs, AlnMg, and AlnN clusters [12], [15], [22]. When the number of Al atom goes to 12, one Al atom begins to enter the Aln cage. In addition, one Al atom capped on the XAln−1 structures for different sized XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) cluster is the dominant growth pattern.

The bond between atoms is closely related to the structure. In order to research the combination of various structure parameters and bonds, we discussed the average bond length of Al–Al, Al–Br and Al–I bonds. For BrAln clusters, the average bond length of Al–Al quickly changes when n = 3–5, then the average bond length of Al–Al increases slowly as the cluster size grows for n > 5. The average bond length of Al–Br decreases with the increasing size, and it also can be seen that the average bond length of Al–Br is smaller than that of Al–Al bond length. For IAln clusters, the average bond lengths of Al–Al and Al–I show the similar trend as that of BrAln clusters. Compared with Al7Y0,−1 (Y=F, Cl) [17] clusters, the Al–X (X = Br, I) bond length increases clearly.

3.2 Relative Stabilities

In order to analyse the stability of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters, the averaged binding energy (Eb), second-order energy difference (Δ2E), and fragmentation energy (Ef) are calculated and listed in Table 2. For XAln clusters, the Eb, Δ2E, and Ef can be defined as follows [15]:

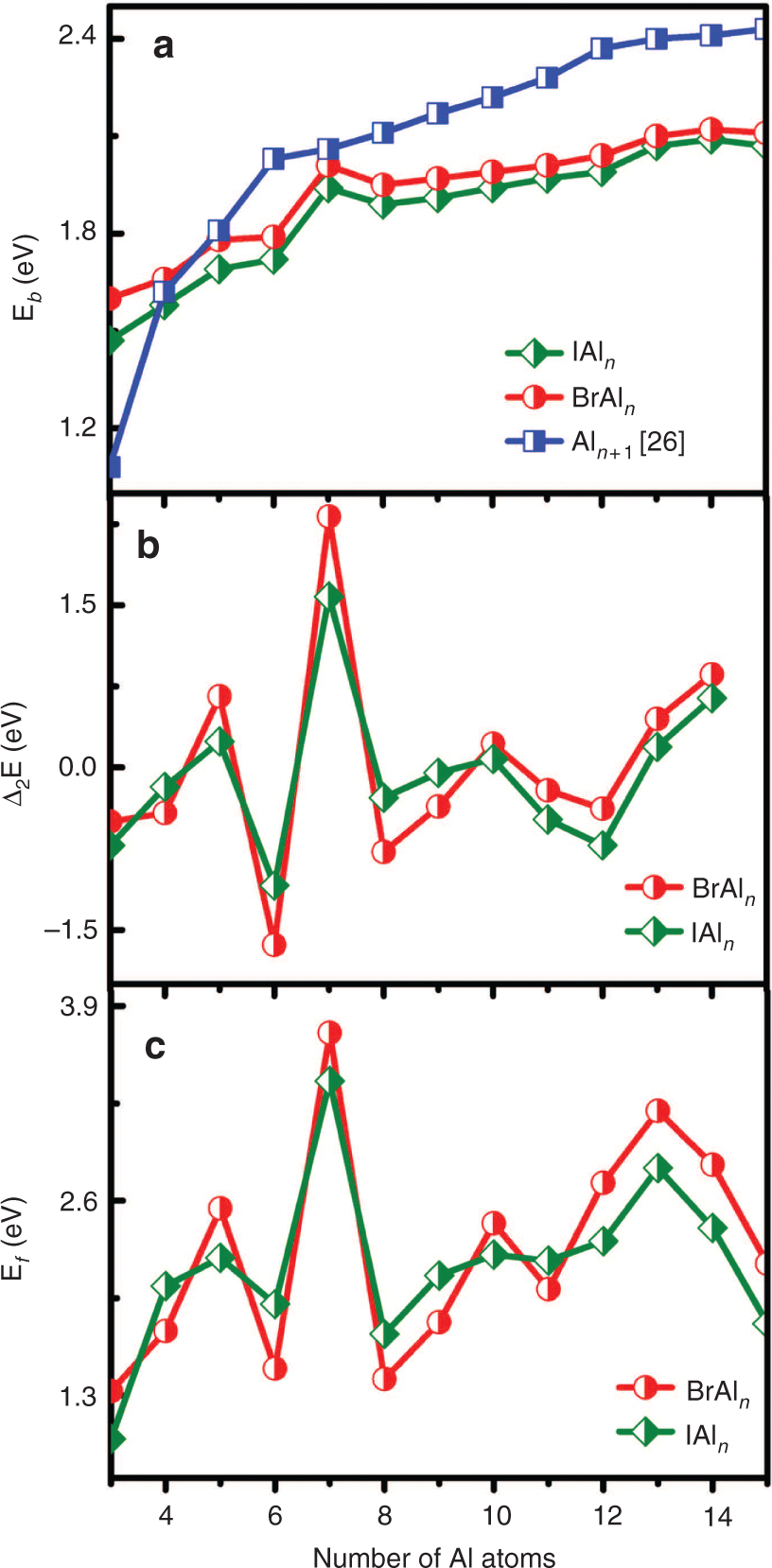

The Eb, Δ2E, and Ef of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters are plotted in Figure 3a, b, and c. As Figure 3 shows, some meaningful results can be obtained.

The size dependence of the averaged binding energy Eb (a), second-order difference energy Δ2E (b), and fragment energy Ef (c) of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

The Eb values of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) and Aln+1 [25] clusters have an increasing tendency with increasing cluster size. For XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15), one clear peak is found at n = 7, indicating that the Al7Br and Al7I clusters are relatively more stable than its neighbouring. Moreover, the Eb of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters is smaller than that of Aln+1 [25] clusters except n = 3 and 4, which implies that the impurity of the X (X = Br, I) atoms can reduce the stabilities of aluminium clusters. Similar phenomena have been found in the previous researches of AlnP and AlnMg [23], [25] clusters.

The Δ2E values of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters show an irregular odd–even oscillatory behaviour as a function of cluster size. Specifically, the XAl5,7,10,14 (X = Br, I) clusters have higher stability than the others. For BrAl7 and IAl7 clusters, they have the largest Δ2E of 2.01 and 1.94 eV, respectively, which implies that BrAl7 and IAl7 isomers are more stable than other XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters. This feature also occurs separately in chemical hardness and vertical ionisation potential. The Ef of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters exhibits a similar trend of Δ2E. The obvious peaks appear at BrAl5,7,10,14 and IAl5,7,10,14 clusters, indicating that these clusters have stronger relative stabilities compared with their neighbours, which is in line with the trend of Δ2E.

Based on the above analysis, it is clear to find that the magic number of the relative stability is n = 7 among the investigated XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters, implying that the BrAl7 and IAl7 clusters are the most stable geometries in the XAln clusters, respectively.

3.3 HOMO-LUMO Gaps and Charge Transfer

The HOMO-LUMO energy gaps (Egap) are a useful quantity for reflecting the stability of clusters; in general, a system with larger Egap is usually less reactive [15]. Here, the Egap of the most stable XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters is calculated and displayed in Figure 4, and the values are also summarized in Table 2. By comparing the Egap curves of BrAln and IAln clusters in Figure 4, one can find that the Egap curves exhibit obvious odd–even oscillating trend, which implies that the odd number clusters (n = 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15) with even valence electrons keep stronger stabilities compared with their neighbouring clusters, which may be result from their closed-shell configuration. It is worth noting that the enhanced stabilities of these clusters are associated with the maximum hardness principle [40], analyzed in Section 3.4. Especially, the BrAl7 and IAl7 clusters have the largest Egap values of 2.63 and 2.62 eV, respectively. The reason may be related to the closed structure of XAl7 (X = Br, I), and the Ionization Potentials (IPs) (7.30 and 7.16 eV) are quite high. It is very interesting to note that the Egap for Al7X (X = F, Cl) [17] has the value of almost 2.67 eV.

The natural population charges (NPCs) and NECs of the X (X = Br, I) atom in XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

| n | BrAln | n | IAln | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPC | NEC | NPC | NEC | ||

| 3 | −0.44 | 4s1.934p5.51 | 3 | −0.40 | 5s1.905p5.49 |

| 4 | −0.24 | 4s1.874p5.52 | 4 | −0.31 | 5s1.915p5.41 |

| 5 | −0.40 | 4s1.874p5.53 | 5 | −0.28 | 5s1.875p5.41 |

| 6 | −0.38 | 4s1.864p5.52 | 6 | −0.25 | 5s1.865p5.40 |

| 7 | −0.38 | 4s1.864p5.52 | 7 | −0.26 | 5s1.865p5.40 |

| 8 | −0.37 | 4s1.864p5.51 | 8 | −0.25 | 5s1.865p5.39 |

| 9 | −0.37 | 4s1.864p5.51 | 9 | −0.25 | 5s1.865p5.39 |

| 10 | −0.40 | 4s1.884p5.52 | 10 | −0.28 | 5s1.885p5.40 |

| 11 | −0.37 | 4s1.844p5.53 | 11 | −0.24 | 5s1.835p5.40 |

| 12 | −0.36 | 4s1.854p5.51 | 12 | −0.24 | 5s1.855p5.39 |

| 13 | −0.36 | 4s1.834p5.53 | 13 | −0.23 | 5s1.835p5.40 |

| 14 | −0.37 | 4s1.854p5.52 | 14 | −0.25 | 5s1.855p5.38 |

| 15 | −0.38 | 4s1.844p5.54 | 15 | −0.26 | 5s1.845p5.42 |

The HOMO-LUMO energy gap (Egap) of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

To study the internal charge transport mechanism of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters more deeply, the natural charge population (NCP) and natural electron configurations (NECs) of the most stable XAln (X = Br, I) species are calculated and listed in Table 3. The NCP values show that the Br and I atoms possess negative −0.24 to −0.44e and −0.23 to −0.40e charges, respectively, which indicates that the charges transfer from the Al atoms to the X (X = Br, I) atom; namely, Br or I acts as electron acceptor in all XAln (X = Br, I) clusters. The reason for this is possibly because X [X = Br (2.96), I (2.66)] atom has a higher electronegativity than Al (1.61) atom [41]. On the basis of the NEC values, one can find that 5.51–5.54 and 5.38–5.49 electrons, respectively, occupy the 5p subshells of the Br and I atoms in the ground-state BrAln and IAln clusters. The values reveal that the 5p orbitals of the X (X = Br, I) atom in XAln (X = Br, I) clusters can be considered as dominant core orbital. With regard to impurities, the NEC values also show that the 4s orbital of Br atom and 5s orbital of I atom lose electrons 0.07–0.17 and 0.09–0.17, respectively. Charges are transferred from Al atoms and the 4s/5s orbitals of the X (X = Br, I) atom to the 5p orbitals of the X (X = Br, I) atom, respectively. Therefore, one can conclude that the charge distributions of XAln (X = Br, I) clusters are primarily governed by s- and p-orbital interactions.

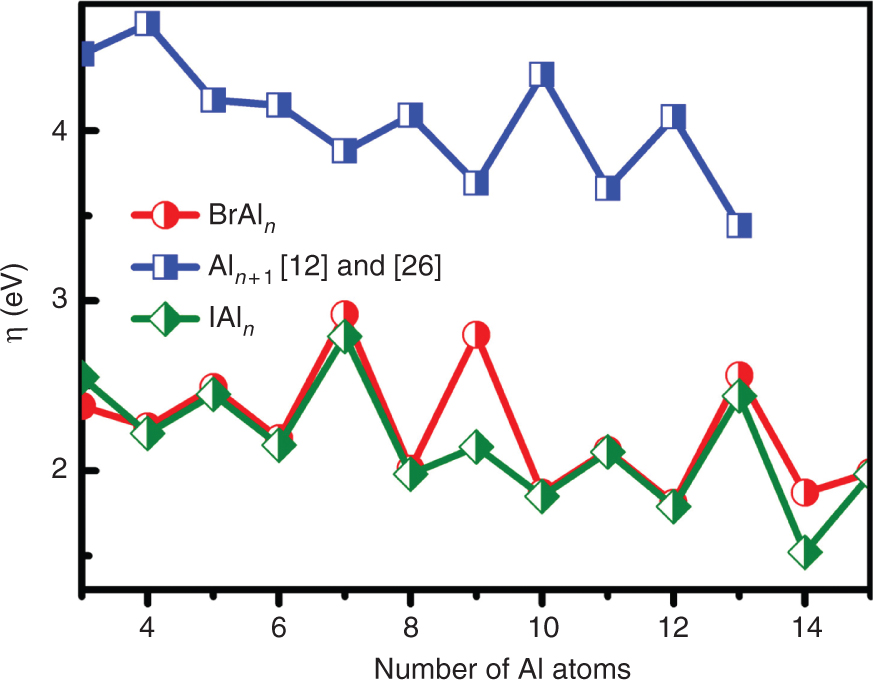

The chemical hardness of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

3.4 Chemical Hardness

The chemical hardness η is an important electronic quantity of the chemical stabilities, which could be used to characterize the relative stabilities of molecules and aggregate through the principle of maximum hardness proposed by Pearson [40]. The η can be obtained by:

where VIP is the vertical ionisation potential, and VEA is the vertical electron affinity. The η of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters is calculated according to formula (4) and plotted in Figure 5. The values of VIP and VEA are listed in Table 4. For comparison, the η of pure Aln+1 (n = 3–14) [12], [25] clusters is also displayed in Figure 5. As Figure 5 shows, the η of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters has apparent odd–even oscillatory behaviours. It means that the odd numbers have stronger η than their neighbours, which is in accord with the above analysis of Egap. Especially, the XAl7 (X = Br, I) clusters have the largest η value of 2.92 and 2.79 eV, respectively, which implies that these clusters are very inert and could be helpful to fabricate the cluster-assembled nanomaterials [42]. In addition, the η of pure Aln+1 (n = 3–14) [12], [25] clusters is higher than that of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters, which reflects that the doped X (X = Br, I) atom in the XAln clusters contributes to weaken the stabilities of the Aln framework. This trend is in agreement with the above trend in Eb.

The VIPs and VEAs of the ground-sate XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

| n | BrAln | n | IAln | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIP | VEA | VIP | VEA | ||

| 3 | 6.61 | 1.85 | 3 | 6.84 | 1.73 |

| 4 | 6.75 | 2.13 | 4 | 6.57 | 2.13 |

| 5 | 6.68 | 1.71 | 5 | 6.64 | 1.74 |

| 6 | 6.65 | 2.27 | 6 | 6.60 | 2.29 |

| 7 | 7.30 | 1.45 | 7 | 7.16 | 1.57 |

| 8 | 6.35 | 2.33 | 8 | 6.31 | 2.34 |

| 9 | 6.42 | 0.82 | 9 | 6.38 | 2.09 |

| 10 | 6.12 | 2.37 | 10 | 6.08 | 2.38 |

| 11 | 6.50 | 2.26 | 11 | 6.47 | 2.25 |

| 12 | 6.28 | 2.67 | 12 | 6.25 | 2.67 |

| 13 | 6.57 | 1.44 | 13 | 6.84 | 1.96 |

| 14 | 5.78 | 2.04 | 14 | 5.76 | 2.72 |

| 15 | 6.18 | 2.21 | 15 | 6.17 | 2.21 |

3.5 Polarisabilities and Dipole Moment

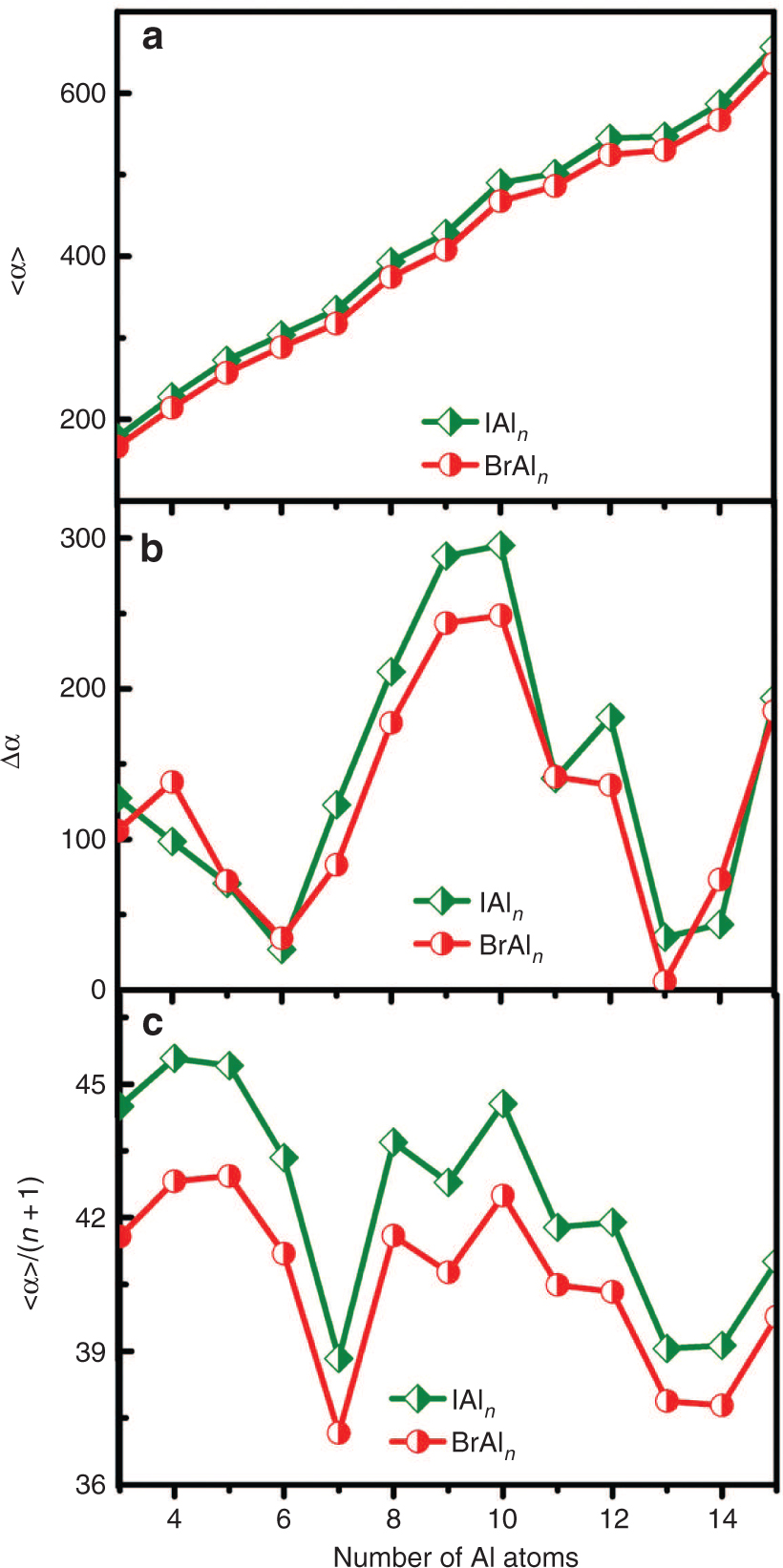

The polarisability is one of the important physical parameters to describe the static property of clusters as we know it. Figure 6a, b, and c show the mean polarisability <α>, polarisability anisotropies Δα, and mean polarisability per atom <α>/(n + 1) of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

where ajj(j = x, y, z) is the integral part of polarisability tensors for XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

The static mean polarisabilities (<α>) (a), polarisability anisotropies (Δα) (b), and static mean polarisability per atom (<α>/(n+1) (c) of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

As shown in Figure 6a, the <α> of XAln (X = Br, I) clusters increases slowly in the range of n = 3–15, implying that the electronic cloud of XAln clusters appears to be easily influenced by outer electronic field and that the nonlinear optical efficiency of XAln clusters can be enhanced by increasing n (from n = 3–15). In addition, one can find that the values of <α> show an order of IAln > BrAln, indicating that the BrAln has relatively higher chemical stabilities than IAln based on the minimum polarisability principle (MPP) theorem [43], [44]. This fact is also in accordance with the above discussion on the stabilities of XAln (X = Br, I) clusters. Figure 6b shows the Δα of XAln (X = Br, I) clusters, it notes a similar trend in the range of n = 3–15 for BrAln and IAln clusters, and some obvious peaks are found at n = 4, 10, 15 and n = 3, 10, 12, 15, respectively. This fact implies that BrAl4,10,15 and IAl3,10,12,15 clusters have a relatively stronger response capability with respect to the external field. From Figure 6c, a similar variation trend of <α>/(n + 1) is also observed in the BrAln and IAln clusters. The BrAl7 and IAl7 clusters have the smallest <α>/(n + 1) values, which probably stems from a joint effect of compactness of structure and closed-shell electronic configuration of this cluster. According to MPP theorem that the natural direction of evolution of any system is toward a state of minimum polarisability, we can conclude that the BrAl7 and IAl7 clusters are stable clusters.

The dipole moments in clusters are responsible for the behaviour of a substance in the presence of external electric fields. In Figure 7, the dipole moments of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters exhibit significantly even–odd oscillation with the increased cluster size, which implies that the even number clusters (n = 4, 6, 7, 10, 12, and 14) have higher dipole moment compared with their neighbouring clusters. This case is in contrast to the odd–even oscillation of Egap. In other words, the dipole moment increased when the cluster number is even, but the Egap decreased. This may be caused by their opened-shell configuration and the asymmetric distribution of electron cloud.

The dipole moment of ground-state XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters.

4 Conclusions

In this work, a detailed theoretical study on the geometries, relative stabilities, HOMO-LUMO gap, charge transfer, chemical hardness, polarisability, and dipole moment of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters has been performed by DFT calculation at the B3LYP/GENECP level. The results are as follows: (i) the optimised results show that the lowest-energy XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) clusters have 3D structures with the exception of n = 3, and the XAln−1 capped with an Al atom is the dominant growth pattern. (ii) The stability analyses reveal that the BrAl7 and IAl7 isomers are the most stable clusters for BrAln and IAln clusters, respectively. (iii) The HOMO-LUMO gap and chemical hardness exhibit an obvious odd–even oscillation, while the dipole moments display an opposite even–odd oscillation. The results also indicate that the odd number clusters have enhanced stabilities compared with other clusters. (iv) The charge analyses point out that the charge transfer from the Al atoms to the X (X = Br, I) atom, and there are strong sp interactions in the X (X = Br, I) atom. (v) The value of polarisability show a sequence of IAln ¿ BrAln, implying that the BrAln has relatively stronger stabilities than those of IAln.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11274235 and 11304167), Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (Nos. 20110491317 and 2014T70280), and Natural Science Foundation of Henan Educational Committee (16A430023).

References

[1] W. C. Lu, C. Z. Wang, L.-Z. Zhao, W. Zhang, W. Qin, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 8551 (2010).10.1039/c004059bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] B. J. Irving and F. Y. Naumkin, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 7697 (2014).10.1039/c3cp54662dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] N. S. Khetrapal, T. Jian, R. Pal, G. V. Lopez, S. Pande, et al., Nanoscale 8, 9805 (2016).10.1039/C6NR01506ASearch in Google Scholar

[4] C. G. da Rocha, P. A. Clayborne, P. Koskinen, and H. Häkkinen, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 3558 (2014).10.1039/c3cp53780cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] B. K. Rao and P. Jena, J. Chem. Phys. 111, 1890 (1999).10.1063/1.479458Search in Google Scholar

[6] R. Fournier, J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 3, 921 (2007).10.1021/ct6003752Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] F. C. Chuang, C. Z. Wang, and K. H. Ho, Phys. Rev. B 73, 125431 (2006).10.1103/PhysRevB.73.125431Search in Google Scholar

[8] A. Nakajima, T. Taguwa, K. Nakao, K. Hoshino, S. Iwata, et al., J. Chem. Phys. 102, 660 (1995).10.1063/1.469178Search in Google Scholar

[9] A. Pramann, A. Nakajima, and K. Kaya, J. Chem. Phys. 115, 5404 (2001).10.1063/1.1394944Search in Google Scholar

[10] B. K. Rao and P. Jena, J. Chem. Phys. 115, 778 (2001).10.1063/1.1379973Search in Google Scholar

[11] W. M. Sun, Y. Li, D. Wu, and Z. R. Li, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 16467 (2012).10.1039/c2cp42386cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] L. Guo, J. Alloy. Comp. 527, 197 (2012).10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.03.013Search in Google Scholar

[13] M. B. Torres, A. Vega, F. Aguilera-Granja, and L. C. Balbás, J. Chem. Phys. 140, 174304 (2014).10.1063/1.4873436Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] B. X. Li, Z. W. Ma, and Q. F. Pan, J. Clust. Sci. 27, 1041 (2016).10.1007/s10876-016-0987-xSearch in Google Scholar

[15] X. D. Xing, J. J. Wang, X. Y. Kuang, X. X. Xia, C. Lu, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 26177 (2016).10.1039/C6CP05571KSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] D. E. Bergeron, P. J. Roach, A. W. Castleman, N. O. Jones, and S. N. Khanna, Science 307, 231 (2005).10.1126/science.1105820Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] J. Sun, W. C. Lu, L. Z. Zhao, W. Zhang, Z. S. Li, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 4378 (2007).10.1021/jp068591oSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Y. K. Han and J. Jung, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 2 (2008).10.1021/ja074225mSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] M. D. Deshpande and D. G. Kanhere, Phys. Rev. B 68, 035428 (2003).10.1103/PhysRevB.68.035428Search in Google Scholar

[20] A. Aguado and J. M. López, J. Chem. Phys. 130, 064704 (2009).10.1063/1.3075834Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Z. Y. Jiang, C. J. Yang, and S. T. Li, J. Chem. Phys. 123, 204315 (2005).10.1063/1.2130339Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] B. L. Wang, J. J. Zhao, D. N. Shi, X. S. Chen, and G. H. Wang, Phys. Rev. B 72, 023204 (2005).10.1103/PhysRevA.72.023204Search in Google Scholar

[23] L. Guo and H. S. Wu, J. Nanopart. Res. 10, 341 (2008).10.1007/s11051-007-9258-ySearch in Google Scholar

[24] X. J. Ren and B. X. Li, Physica B, 405, 2344 (2010).10.1016/j.physb.2010.02.045Search in Google Scholar

[25] Y. F. Ouyang, P, Wang, P. Xiang, H. M. Chen, and Y. Du, Comput. Theor. Chem. 984, 68 (2012).10.1016/j.comptc.2012.01.012Search in Google Scholar

[26] M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, et al., Gaussian 09 (Revision C.01), Gaussian, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[27] A. D. Becke, J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648 (1993).10.1063/1.464913Search in Google Scholar

[28] J. P. Perdew and Y. Wang, Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244 (1992).10.1103/PhysRevB.45.13244Search in Google Scholar

[29] J. P. Perdew, P. Ziesche, and H. Eschrig, Electronic Structure of Solids, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1991.Search in Google Scholar

[30] A. D. Becke, Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098 (1988).10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098Search in Google Scholar

[31] J. P. Perdew, Phys. Rev. B 33, 8822 (1986).10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8822Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke and M. Ernzerhof, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] C. T. Lee, W. T. Yang, and R. G. Parr, Phys. Rev. B 37, 785 (1988).10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785Search in Google Scholar

[34] Z. W. Fu, G. W. Lemire, and G. A. Bishea, J. Chem. Phys. 93, 8420 (1990).10.1063/1.459280Search in Google Scholar

[35] H. Cordes and H. Sponer, Z. Phys. 63, 334 (1930).10.1007/BF01339609Search in Google Scholar

[36] P. B. V. Haranath and P. T. Rao, J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2, 428 (1958).10.1016/0022-2852(58)90093-6Search in Google Scholar

[37] J. D. Brown, G. Burns, and R. J. Leroy, Can. J. Phys. 51, 1664 (1973).10.1139/p73-220Search in Google Scholar

[38] F. H. Crawford and C. F. Ffolliott, Phys. Rev. 44, 953 (1933).Search in Google Scholar

[39] F. C. Wyse and W. Gordy, J. Chem. Phys. 56, 2130 (1972).10.1063/1.1677509Search in Google Scholar

[40] R. G. Pearson, Chemical Hardness: Applications from Molecules to Solids, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 1997.10.1002/3527606173Search in Google Scholar

[41] G. D. Zhou and L. Y. Duan, Structural Chemistry Basis, Peking University Press, Beijing 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[42] P. J. Bruna, S. D. Peyerimhoff, and R. J. Buenker, J. Chem. Phys. 72, 5437 (1980).10.1063/1.439012Search in Google Scholar

[43] P. K. Chattaraj, P. Fuentealba, P. Jaqueand, and A. Toro-Labbé, J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 9307 (1999).10.1021/jp9918656Search in Google Scholar

[44] U. Hohm, J Phys Chem A 104, 8418 (2000).10.1021/jp0014061Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/zna-2018-0376).

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- General

- Einstein’s “Clock Hypothesis” and Mössbauer Experiments in a Rotating System

- Atomic, Molecular & Chemical Physics

- Dual Fabry–Pérot Interferometric Carbon Monoxide Sensor Based on the PANI/Co3O4 Sensitive Membrane-Coated Fibre Tip

- Study of the Geometric Structures, Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Aluminium-Antimony Alloy Clusters

- A Density Functional Theory Study on the Structures and Electronic Properties of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) Clusters

- Dynamical Systems & Nonlinear Phenomena

- Three-Dimensional Instability of Opposite Polarity Nonthermal Dusty Plasma

- Riemann–Hilbert Problem and Multi-Soliton Solutions of the Integrable Spin-1 Gross–Pitaevskii Equations

- Quantum Theory

- Space-time from Collapse of the Wave-function

- Gravitation & Cosmology

- Modeling Cosmic Expansion, and Possible Inflation, as a Thermodynamic Heat Engine

- Hydrodynamics

- Safety Factor for the New Exact Plasma Equilibria

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- General

- Einstein’s “Clock Hypothesis” and Mössbauer Experiments in a Rotating System

- Atomic, Molecular & Chemical Physics

- Dual Fabry–Pérot Interferometric Carbon Monoxide Sensor Based on the PANI/Co3O4 Sensitive Membrane-Coated Fibre Tip

- Study of the Geometric Structures, Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Aluminium-Antimony Alloy Clusters

- A Density Functional Theory Study on the Structures and Electronic Properties of XAln (X = Br, I; n = 3–15) Clusters

- Dynamical Systems & Nonlinear Phenomena

- Three-Dimensional Instability of Opposite Polarity Nonthermal Dusty Plasma

- Riemann–Hilbert Problem and Multi-Soliton Solutions of the Integrable Spin-1 Gross–Pitaevskii Equations

- Quantum Theory

- Space-time from Collapse of the Wave-function

- Gravitation & Cosmology

- Modeling Cosmic Expansion, and Possible Inflation, as a Thermodynamic Heat Engine

- Hydrodynamics

- Safety Factor for the New Exact Plasma Equilibria