Abstract

The metal-rich antimonide Gd5Rh19Sb12 was synthesized by induction-melting of the elements in a sealed tantalum ampoule. The Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure was refined from single crystal X-ray diffractometer data of a twinned crystal: P31m, a = 1,349.3(3), c = 417.99(12) pm, wR2 = 0.0682, 1545 F2 values and 67 variables. Gd5Rh19Sb12 is closely related to the Sc5Co19P12-type. A split position of Rh5 is avoided by a translationengleiche symmetry reduction of index 2 from P

1 Introduction

The ternary systems RE-T-P 1 and RE-T-Si 2 , 3 (RE = rare earth element, T = electron-rich transition metal) have intensively been studied and a manifold of ternary phosphides and silicides has been structurally characterized. 4 The transition metal-rich parts of these phase diagrams are characterized by a large family of compounds with a metal-to-metalloid ratio of exactly or close to 2:1. The basic geometrical building units of all these structures are phosphorus or silicon centered trigonal prisms formed by the RE and/or T atoms. Condensation of these prisms leads to a variety of extended geometrical motifs which spread from isolated prisms to shamrock-like trimeric units up to larger arrangements which are usually called propeller-shaped assemblies. 5 , 6 This kind of modular principle is helpful to explain and classify the different, sometimes complex structure types.

Some of the structural families observed for the phosphides and silicides also occur with the higher homologues arsenic and germanium; however, to a lesser extent. While many of the RE-T-Ge systems have thoroughly been studied, 7 , 8 systematic phase analytical knowledge of the respective arsenic systems is poor. One of the largest series of isotypic representatives are the Zr2Fe12P7-type phases RE2(Co, Ni, Rh)12P7 and RE2(Co, Ni, Rh)12As7. 4 In going to antimony, only the metal-rich series RE3Pt7Sb4 (RE = Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm) 9 and RE6Rh30Sb19 (RE = La–Nd, Sm, Eu) 10 with antimony centered trigonal prisms are known.

During phase analytical studies in the RE-T-Sb systems we have now obtained Gd5Rh19Sb12, the first antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12-related 11 structure. In the field of intermetallics, Sc5Co19P12 type phases are known for the phosphides A5T19P12 (A = Ca, Zr, Hf, rare earth metal; T = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ru, Rh and Ir), 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 the tetrelides (Sr, Ba, Eu, Yb)5Mg19(Si, Ge)12 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 and the recently reported silicides RE5Ir19Si12 (RE = Y, Gd–Dy, Er, Tm, Lu). 33 Gd5Rh19Sb12 is a remarkable compound since phosphorus was substituted by the much larger homologue antimony and still no arsenides with this structure type are known. The synthesis and structural chemistry of Gd5Rh19Sb12 are reported herein.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis

Starting materials for the synthesis of Gd5Rh19Sb12 were gadolinium ingots (Johnson Matthey), rhodium powder (Degussa-Hüls) and antimony shots (Johnson Matthey), all with stated purities better than 99.9 %. The elements were weighed in the atomic ratio of Gd:Rh:Sb = 1:2:2 and arc-welded 34 in a tantalum ampoule. The latter was placed in a water-cooled sample chamber of an induction furnace (Hüttinger Elektronik, Freiburg, Typ TIG 1.5/300), 35 heated to 1280 K and kept at that temperature for 10 min. The temperature was then lowered to 1080 K and the sample was annealed for another 3 h followed by rapid cooling (switching off the power supply). The temperature was controlled through a radiation pyrometer (Metis MS09, Sensortherm) with an accuracy of ±50 K. The product sample was mechanically broken out of the ampoule. No reaction with the crucible material was evident. Gd5Rh19Sb12 is stable in air. Single crystals exhibit silvery metallic luster.

2.2 X-ray diffraction

Pieces of the annealed sample were carefully crushed and small irregularly shaped single crystals were selected under an optical microscope. The crystals were glued to thin glass fibers using beeswax and their quality was first tested by Laue photographs on a Buerger camera (white molybdenum radiation, image plate technique, Fujifilm, BAS-1800). A complete data set of an appropriate crystal was collected at room-temperature on a STOE IPDS-II diffractometer (graphite-monochromatized MoK α radiation; oscillation mode). A numerical absorption correction was applied to the data set. Details about the data collection and the structure refinement are summarized in Table 1.

Single crystal data and refinement parameters of Gd5Rh19Sb12, Z = 1, space group P31m and Pearson code hP36. The data set was collected on a Stoe IPDS II diffractometer with Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 71.073 pm).

| Formula | Gd5Rh19Sb12 |

| Molar mass/g mol−1 | 4,202.5 |

| Cell parameters/pm | a = 1,349.3(3) |

| c = 417.99(12) | |

| Cell volume/nm3 | V = 0.6591 |

| Calc. density/g cm−3 | 10.59 |

| Crystal size/µm3 | 20 × 20 × 30 |

| Absorpt. corr. | Numerical |

| Absorpt. coeff./mm−1 | 35.9 |

| Detector distance/mm | 80 |

| Irradiation time/min | 5 |

| ω range, increment/◦ | 0–180; 1.0 |

| Integr. param. (A; B; EMS) | 13.2; 3.1; 0.022 |

| F(000)/e | 1,787 |

| θ range/◦ | 3.02–31.79 |

| hkl range | ±20; ±20; ±5 |

| No. Refl. | 7,744 |

| Indep. refl./Rint | 1,545/0.0613 |

| Refl. with I ≥ 3σ(I)/R σ | 1,223/0.0480 |

| Data/parameters | 1,545/67 |

| Goodness-of-fit | 1.34 |

| R1/wR2 (I ≥ 3σ(I)) | 0.0349/0.0666 |

| R1/wR2 (all data) | 0.0458/0.0682 |

| Extinct. coeff. | 71(9) |

| Flack parameter | 0.12(12) |

| Largest diff. peak, hole/e Å−3 | 2.33/−2.25 |

2.3 EDX analysis

The Gd5Rh19Sb12 single crystal studied on the image-plate diffractometer was semiquantitatively analyzed by EDX: Zeiss EVO® MA10 scanning electron microscope, LaB6 cathode, variable pressure mode (60 Pa N2) and an Oxford Instruments INCA® x-act detector. GdF3, Rh and Sb were used as standards. The analyses on the irregular crystal surface resulted in the composition 12 ± 2 at.% Gd: 55 ± 2 at.% Rh: 33 ± 2 at.% Sb, in agreement with the ideal composition (13.9 : 52.8: 33.3). No impurity elements were detected.

3 Structure refinement

The diffractometer data set showed a hexagonal lattice and no further systematic extinctions. In agreement with our earlier studies on the RE5Ir19P12 phosphides

27

and RE5Ir19Si12 silicides,

33

the non-centrosymmetric space group P

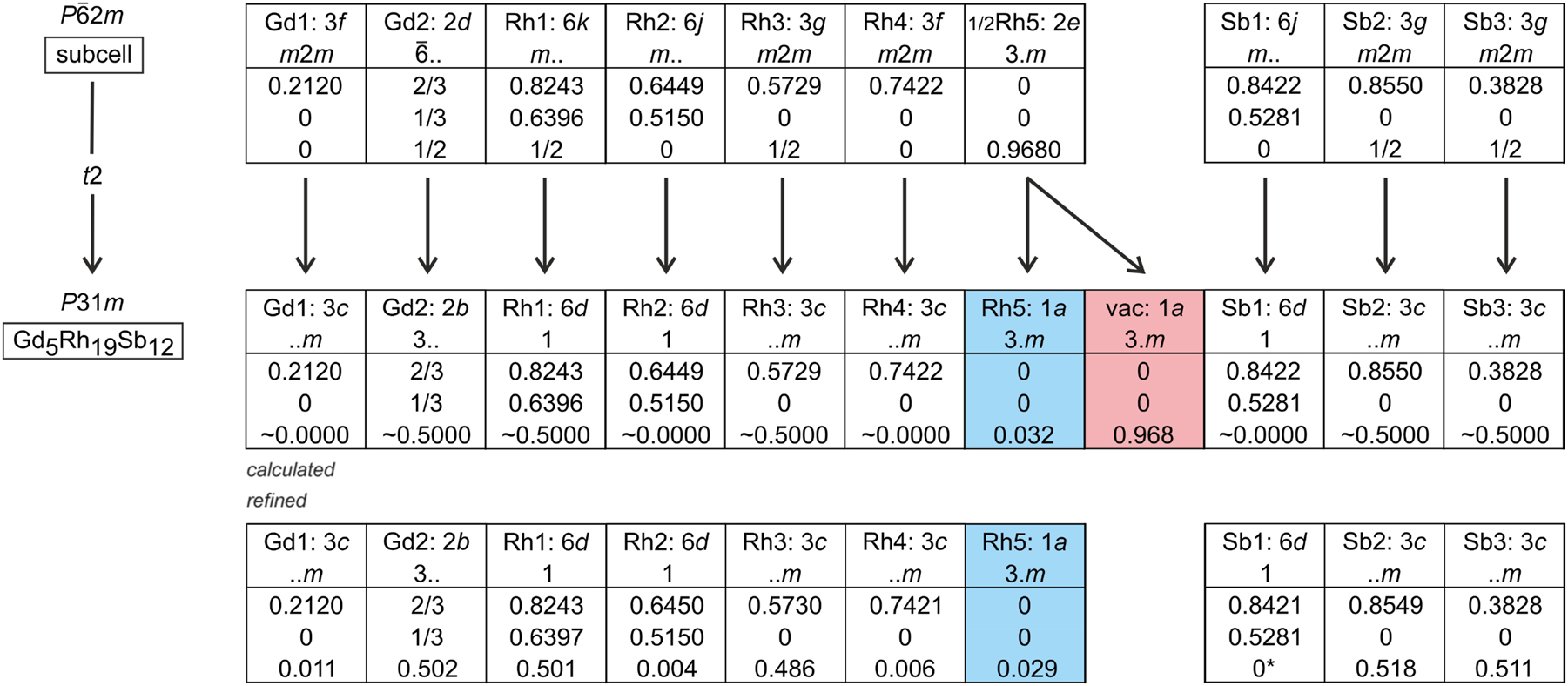

The split position called for a symmetry reduction. The simplest step is a translationengleiche symmetry reduction of index 2 to the trigonal space group P31m, where the 2e site splits into two one-fold sites 1a, of which only one needs to be occupied. The corresponding Bärnighausen tree

40

,

41

,

42

,

43

is presented in Figure 1. We have thus transferred the coordinates of the subcell refinement to space group P31m and refined the structure again, now with anisotropic displacement parameters for all sites. The loss of the

Atomic coordinates and anisotropic displacement parameters (pm2) for Gd5Rh19Sb12 at 300 K (space group P31m). The anisotropic displacement factor exponent takes the form: –2π2[(ha*)2U11 + … + 2hka*b*U12]. Ueq is defined as one third of the trace of the orthogonalized U ij tensor.

| Atom | Wyckoff | x | y | z | U 11 | U 22 | U 33 | U 12 | U 13 | U 23 | Ueq/Uiso |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd1 | 3c | 0.21196(9) | 0 | 0.011(3) | 97(3) | 113(5) | 108(8) | 57(2) | −10(20) | 0 | 104(4) |

| Gd2 | 2b | 2/3 | 1/3 | 0.502(3) | 134(4) | U 11 | 92(8) | 67(2) | 0 | 0 | 120(4) |

| Rh1 | 6d | 0.82431(11) | 0.63966(10) | 0.501(2) | 81(5) | 92(5) | 104(7) | 40(5) | −10(20) | 20(20) | 94(5) |

| Rh2 | 6d | 0.64496(10) | 0.51504(9) | 0.004(2) | 95(5) | 77(5) | 123(8) | 42(4) | −30(30) | 10(20) | 99(4) |

| Rh3 | 3c | 0.57305(15) | 0 | 0.486(4) | 116(5) | 193(9) | 110(30) | 97(5) | −14(18) | 0 | 133(10) |

| Rh4 | 3c | 0.74213(14) | 0 | 0.006(3) | 154(6) | 101(8) | 149(12) | 50(4) | −30(30) | 0 | 140(6) |

| Rh5 | 1a | 0 | 0 | 0.029(7) | 183(10) | U 11 | 270(70) | 91(5) | 0 | 0 | 210(30) |

| Sb1 | 6d | 0.84212(9) | 0.52809(9) | 0* | 99(4) | 98(5) | 93(8) | 53(4) | 0(2) | 10(20) | 95(4) |

| Sb2 | 3c | 0.85493(13) | 0 | 0.518(3) | 168(6) | 94(6) | 102(15) | 47(3) | −10(19) | 0 | 130(6) |

| Sb3 | 3c | 0.38275(11) | 0 | 0.511(3) | 97(5) | 100(6) | 97(10) | 50(3) | −20(30) | 0 | 97(5) |

Interatomic distances (pm) for Gd5Rh19Sb12. All distances of the first coordination spheres are listed. Standard deviations are equal or smaller than 1.0 pm.

| Gd1: | 1 | Rh5 | 286.1 | Rh3: | 1 | Sb3 | 257.0 |

| 2 | Rh1 | 307.0 | 2 | Sb1 | 278.2 | ||

| 2 | Sb3 | 311.1 | 2 | Sb1 | 286.9 | ||

| 2 | Rh1 | 312.6 | 2 | Rh1 | 292.6 | ||

| 2 | Rh2 | 319.2 | 1 | Rh4 | 303.8 | ||

| 2 | Rh4 | 321.5 | 1 | Rh4 | 315.1 | ||

| 2 | Sb2 | 326.5 | 2 | Rh2 | 326.0 | ||

| 2 | Sb2 | 330.2 | 2 | Rh2 | 335.5 | ||

| 1 | Sb1 | 392.4 | Rh4: | 1 | Sb2 | 254.5 | |

| Gd2: | 3 | Sb1 | 325.9 | 2 | Sb1 | 259.4 | |

| 3 | Sb1 | 327.0 | 1 | Sb2 | 262.6 | ||

| 3 | Rh2 | 333.9 | 2 | Rh1 | 292.1 | ||

| 3 | Rh2 | 334.9 | 2 | Rh1 | 295.1 | ||

| 3 | Rh1 | 358.0 | 1 | Rh3 | 303.8 | ||

| Rh1: | 1 | Sb1 | 265.3 | 1 | Rh3 | 315.1 | |

| 1 | Sb3 | 265.6 | 2 | Gd1 | 321.5 | ||

| 1 | Sb1 | 265.9 | Rh5: | 3 | Sb2 | 283.0 | |

| 1 | Sb2 | 267.9 | 3 | Gd1 | 286.1 | ||

| 1 | Rh4 | 292.1 | 3 | Sb2 | 289.7 | ||

| 1 | Rh3 | 292.6 | Sb1: | 1 | Rh2 | 254.5 | |

| 1 | Rh4 | 295.1 | 1 | Rh2 | 257.7 | ||

| 1 | Rh2 | 298.8 | 1 | Rh4 | 259.4 | ||

| 1 | Rh2 | 300.6 | 1 | Rh1 | 265.3 | ||

| 1 | Gd1 | 307.0 | 1 | Rh1 | 265.9 | ||

| 1 | Gd1 | 312.6 | 1 | Rh3 | 278.2 | ||

| 1 | Gd2 | 358.0 | 1 | Rh3 | 286.9 | ||

| Rh2: | 1 | Sb1 | 254.5 | 1 | Gd2 | 325.9 | |

| 1 | Sb1 | 257.7 | 1 | Gd2 | 327.0 | ||

| 1 | Sb3 | 260.8 | Sb2: | 1 | Rh4 | 254.5 | |

| 1 | Sb3 | 265.5 | 1 | Rh4 | 262.6 | ||

| 1 | Rh1 | 298.8 | 2 | Rh1 | 267.9 | ||

| 1 | Rh1 | 300.6 | 1 | Rh5 | 283.0 | ||

| 1 | Rh2 | 303.6 | 1 | Rh5 | 289.7 | ||

| 1 | Gd1 | 319.2 | 2 | Gd1 | 326.5 | ||

| 1 | Rh3 | 326.0 | 2 | Gd1 | 330.2 | ||

| 1 | Gd2 | 333.9 | 2 | Sb2 | 339.0 | ||

| 1 | Gd2 | 334.9 | Sb3: | 1 | Rh3 | 257.0 | |

| 2 | Rh2 | 260.8 | |||||

| 2 | Rh2 | 265.5 | |||||

| 2 | Rh1 | 265.6 | |||||

| 2 | Gd1 | 311.1 |

CCDC–2443530 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

4 Crystal chemistry

Gd5Rh19Sb12 is the first antimonide in the family of Sc5Co19P12-related intermetallic compounds. The substitution of phosphorus by the larger antimony (110 vs. 141 pm covalent radius 48 ) leads to a drastic increase of the unit cell parameters (a = 1,349.3(3), c = 417.99(12) pm), when compared with the gadolinium-based phosphides Gd5Co19P12 (a = 1,210.04(3), c = 370.0(1) pm) 14 and Gd5Ir19P12 (a = 1,262.9(3), c = 395.7(1) pm). 27 The increase is even stronger for the tetrelides (Sr, Ba, Eu, Yb)5Mg19(Si, Ge)12, 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 e. g., a = 1,479.3(1), c = 445.2(1) pm for Eu8Mg16Ge12. 30 This leads to a small but important difference with respect to the prototype Sc5Co19P12. 11 The crystal chemical differences are addressed in the following.

Before starting with the crystal chemical discussion, we first concentrate on the role of the Rh5 atoms, which manifest the difference to the Sc5Co19P12 type. In the prototype structure, the corresponding cobalt atoms fill a trigonal Sc6 prism at the unit cell origin, while in the case of Gd5Rh19Sb12, the Rh5 atoms are shifted by c/2 to the Gd13 triangles; however, refined with a split position in the prototype space group symmetry, P

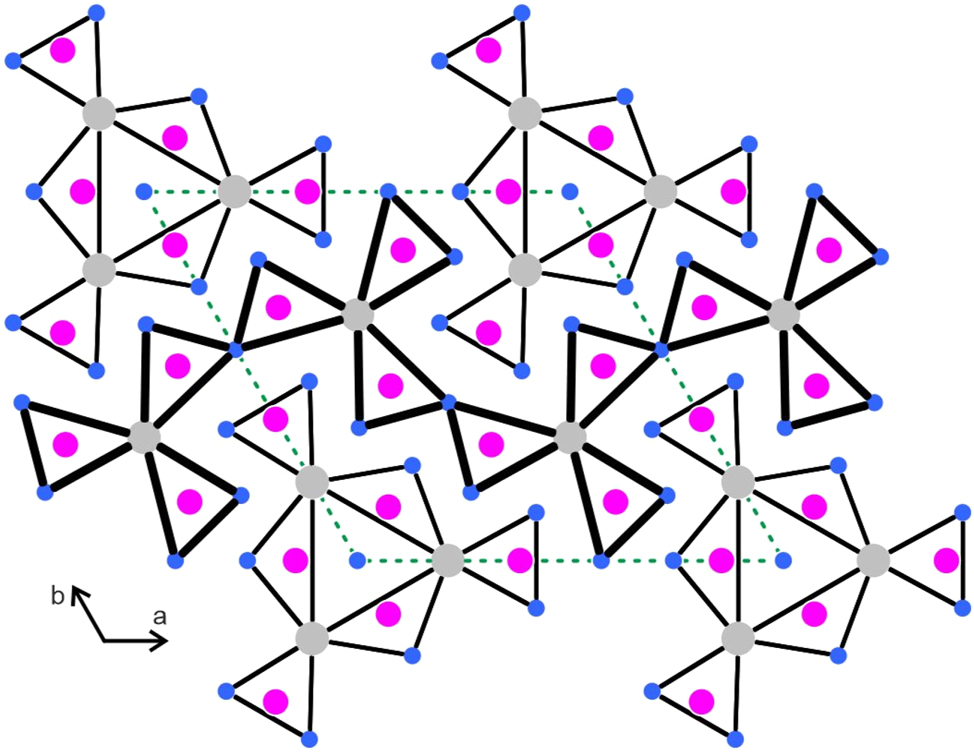

The Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure contains five crystallographically independent rhodium sites. These rhodium atoms have between three and six nearest antimony neighbors with Rh–Sb distances ranging from 255–290 pm, comparable to the antimonides CeRhSb (268–287 pm Rh–Sb), 49 Ce2Rh3Sb4 (259–270 pm Rh–Sb) 50 or Ce8Rh17Sb14 (257–272 pm Rh–Sb). 51 All these Rh–Sb distances are close to the sum of the covalent radii 48 of 266 pm for Rh + Sb. Together, the rhodium and antimony atoms build a covalently bonded [Rh19Sb12] network (Figure 2). This network is additionally stabilized by weak Rh–Rh bonding. The Rh–Rh distances in the Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure range from 292–336 pm, all slightly longer than in fcc rhodium (12 × 269 pm). 52 The two crystallographically independent gadolinium atoms fill slightly distorted hexagonal prismatic cavities within the [Rh19Sb12] network.

![Figure 2:

View of the Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure along the c axis. Gadolinium, rhodium and antimony atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively. The [Rh19Sb12] network is emphasized. Atom designations are given at the lower right-hand part.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2025-0017/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2025-0017_fig_002.jpg)

View of the Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure along the c axis. Gadolinium, rhodium and antimony atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively. The [Rh19Sb12] network is emphasized. Atom designations are given at the lower right-hand part.

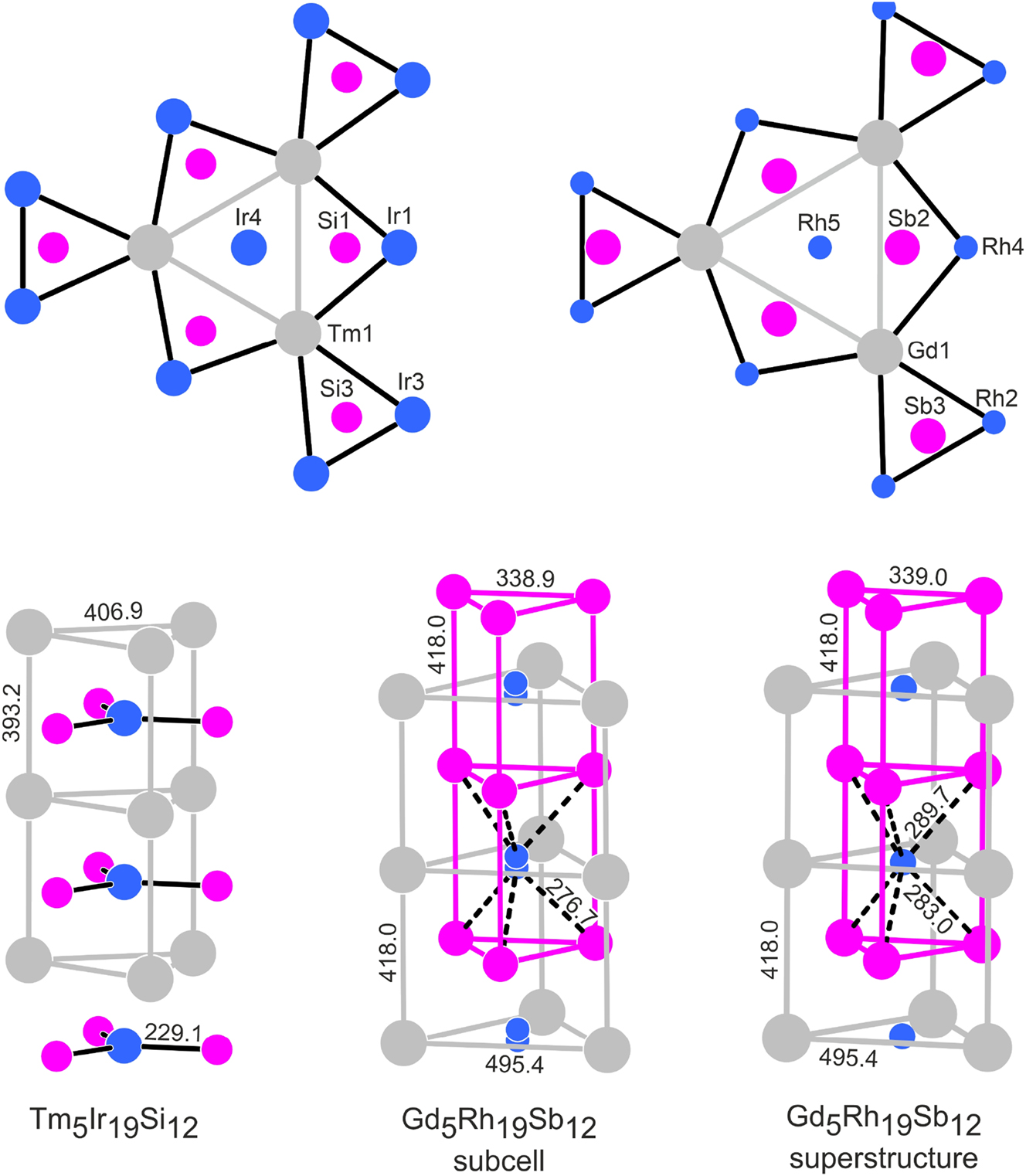

The structures of metal-rich phosphides can geometrically be described by a condensation pattern of phosphorus-centered trigonal prisms formed by the metal atoms. 5 Often the condensation patterns resemble a shamrock-like arrangement. 6 In analogy to the RE5T19P12 phosphides 11 , 14 , 27 and RE5Ir19Si12 silicides, 33 we have drawn the Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure with the trigonal prismatic arrangement around the antimony atoms (Figure 3). The shamrock-like motif that undulates through the middle of the unit cell looks quite regular with antimony atoms approximately within the centers of the trigonal prisms. This is different for the motif located around the origin of the unit cell. The three inner prisms that are directly condensed to form the Gd6 prism have one strongly elongated edge and the antimony atoms are shifted towards the c axis. Also, the terminal prisms of this motif show a shift of the antimony atoms towards the outer Rh4 faces. In Figure 4 we compare this arrangement with the one in the recently reported silicide Tm5Ir19Si12, 33 where all prisms are almost regular.

Projection of the Gd5Rh19Sb12 structure along the c axis. Gadolinium, rhodium and antimony atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively. All atoms lie on mirror planes at z = 0 (thin lines) and z = 1/2 (thick lines). The trigonal prismatic coordination of the antimony atoms in emphasized.

Comparison of the Tm5Ir19Si12 and Gd5Rh19Sb12 structures. Thulium (gadolinium), iridium (rhodium) and silicon (antimony) atoms are drawn as medium grey, blue and magenta circles, respectively. The trigonal prismatic building units around the origins of the unit cells are shown as projections onto the ab planes in the upper part. The lower part shows the local trigonal prismatic coordination in the strands that extend in c direction. Atom designations and relevant interatomic distances are given.

The main difference between the Sc5Co19P12-type phosphides and silicides with the comparatively small phosphorus and silicon atoms on one side and Gd5Rh19Sb12 on the other concerns the position of the rhodium atoms on the c axis. The local coordination in the gadolinium prisms in Gd5Rh19Sb12 is compared with that in Tm5Ir19Si12 in the lower part of Figure 4. The Rh5 atoms in Gd5Rh19Sb12 are shifted by ∼c/2 with respect to Ir4 in Tm5Ir19Si12 and the Sb2 atoms move towards the c axis, forming the trigonal prisms around Rh5. The Gd1 atoms are then capping the rectangular faces of these trigonal prisms. The Sb2–Sb2 contact of 339 pm, i. e., the edge of the triangles, is a weak one and corresponds to the secondary Sb–Sb interactions in elemental antimony (3 × 291 and 3 × 336 pm Sb–Sb). 52 The distance of the Rh5 atoms to the Gd2 atoms of 286 pm is exactly the value of the sum of the covalent radii for Gd + Rh. 48 Thus, the Rh5@Gd23 coordination is comparable to the Ir4@Si13 coordination in Tm5Ir19Si12.

Summing up, Gd5Rh19Sb12 adds a new structural motif to the family of the so-called 5-19-12 phases and can be considered as a proper structure type. The pnictides assigned to the Ho5Ni19P12 type 53 are those phases that show no split position for the atom at the origin, while those related to the Sc5Co19P12 type 11 show cobalt split positions as manifested by single crystal X-ray diffraction data also for Zr5Co19P12 13 and Ho5Co19P12 14 (these two branches are distinguished in the Pearson data base 4 ). Important parameters that have an impact on the T5 subcell site are the size of the rare earth element (one can play with the lanthanide contraction, i.e., the size of the rare earth element) and also the crystal growth conditions (kind of flux and the temperature profile). Especially the thermal treatment of the samples influences a potential long-range order. Thus, it is difficult to predict the correct description of a 5-19-12 crystal. Furthermore, Gd5Rh19Sb12 is the first antimonide of this atomic arrangement with the much larger antimony atoms.

Th5Fe19P12 54 and Yb5Ni19P12, 55 on the other side, have the same atomic ratios as Tm5Ir19Si12 and Gd5Rh19Sb12 but a different condensation pattern of their phosphorus-centered trigonal prisms.

Future studies must now focus on RE5Rh19Sb12 antimonides with rare earth elements larger and smaller than gadolinium, in order to check the existence range of this new type and further on antimony-arsenic substitution, since this is a gap with respect to the many RE5T19P12 phosphides.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dipl.-Ing. U. Ch. Rodewald for the intensity data collection.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved the submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Not relevant. Our group is able to think and act independently.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by Universität Münster.

-

Data availability: Data is available from the corresponding author on well-founded request.

References

1. Kuz’ma, Yu.; Chykhrij, S. Phosphides. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; GschneidnerJr.K. A.; Eyring, L., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Vol. 23, Chapter 156, 1996; pp. 285–433.10.1016/S0168-1273(96)23007-7Suche in Google Scholar

2. Parthé, E.; Chabot, B. Crystal Structures and Crystal Chemistry of Ternary Rare Earth-Transition Metal Borides, Silicides and Homologues. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; GschneidnerJr.K. A.; Eyring, L., Eds.: North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 6, Chapter 48, 1984; pp. 113–332.10.1016/S0168-1273(84)06005-0Suche in Google Scholar

3. Rogl, P. Phase Equilibria in Ternary and Higher Order Systems with Rare Earth Elements and Silicon. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; GschneidnerJr.K. A.; Eyring, L., Eds.; North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 7, Chapter 51, 1984; pp. 1–264.10.1016/S0168-1273(84)07004-5Suche in Google Scholar

4. Villars, P.; Cenzual, K., Eds. Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds (release 2023/24); ASM International®: Materials Park, Ohio (USA), 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Gladyshevskii, E. I.; Grin’, Yu. N. Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 1981, 26, 683–689.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Zaremba, N.; Krnel, M.; Prots, Yu.; König, M.; Akselrud, L.; Grin, Yu.; Svanidze, E. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 4566–4573; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c03837.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Salamakha, P. S.; Sologub, O. L.; Bodak, O. I. Ternary Rare-Earth-Germanium Systems. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; Gschneidner, Jr., K. A.; Eyring, L., Eds.; Elsevier Science B. V.: Amsterdam, Vol. 27, Chapter 173, 1999; pp. 1–223.10.1016/S0168-1273(99)27004-3Suche in Google Scholar

8. Salamakha, P. S. Crystal Structures and Crystal Chemistry of Ternary Rare-Earth Germanides. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; Gschneidner, Jr., K. A.; Eyring, L., Eds.; Elsevier Science B. V.: Amsterdam, Vol. 27, Chapter 174, 1999; pp. 225–338.10.1016/S0168-1273(99)27005-5Suche in Google Scholar

9. Schmidt, T.; Jeitschko, W. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2002, 628, 927–932; https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3749(200206)628:5<927::aid-zaac927>3.0.co;2-c.10.1002/1521-3749(200206)628:5<927::AID-ZAAC927>3.0.CO;2-CSuche in Google Scholar

10. Jeitschko, W.; Altmeyer, R. O.; Rodewald, U.Ch. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 2440–2446; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200900230.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Jeitschko, W.; Reinbold, E. J. Z. Naturforsch. 1985, 40b, 900–905.10.1515/znb-1985-0709Suche in Google Scholar

12. Jeitschko, W.; Meisen, U.; Reinbold, E. J. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2012, 638, 770–778; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.201100502.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Ghetta, V.; Chaudouet, P.; Madar, R.; Senateur, J. P.; Lambert-Andron, B. J. Less-Common Met. 1986, 120, 197–201; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(86)90644-2.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Jakubowski-Ripke, U.; Jeitschko, W. J. Less-Common Met. 1988, 136, 261–270; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(88)90429-8.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Chykhrij, S. I.; Kuz’ma, Y. B. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 35, 1821–1823.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Orishchin, S. V.; Zhak, O. V.; Koval’chuck, I. V.; Kuz’ma, Y. B. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 46, 1892–1895.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Budnyk, S. L.; Kuz’ma, Yu. B. Pol. J. Chem. 2002, 76, 1553–1558.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Babizhetskii, V. S.; Chykhrij, S. I.; Oryshchyn, S. V.; Kuz’ma, Y. B. Ukr. Khim. Zh. Ukr. Ed. 1993, 59, 240–242.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Stoyko, S. S.; Davydov, V. M.; Babizhetskii, V. S.; Oryshchyn, S. V. Visn. Lviv Derzh. Univ., Ser. Khim. 2003, 43, 40–44.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Oryshchyn, S. V.; Chykhrij, S. I.; Babizhetskii, V. S.; Kuz’ma, Yu. B. Dopov. Akad. Nauk Ukr. RSR 1991, 6, 133–136.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Cava, R. J.; Siegrist, T.; Carter, S. A.; Krajewski, J. J.; PeckJr.W. F.; Zandbergen, H. W. J. Solid State Chem. 1996, 121, 51–55; https://doi.org/10.1006/jssc.1996.0007.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Zandbergen, H. W.; Jansen, J. J. Microsc. 1998, 190, 222–237; https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2818.1998.3270880.x.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Jansen, J.; Tang, D.; Zandbergen, H. W.; Schenk, H. Acta Crystallogr. A 1998, 54, 91–101; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108767397010489.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Demchyna, R. O.; Oryshchyn, S. V.; Kuz’ma, Y. B. J. Alloys Compd. 2001, 322, 176–183.10.1016/S0925-8388(01)01017-9Suche in Google Scholar

25. Dhahri, E.; Fourati, N. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1997, 9, 5517–5525; https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/9/26/002.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Wurth, A.; Löhken, A.; Mewis, A. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2002, 628, 661–666.10.1002/1521-3749(200203)628:3<661::AID-ZAAC661>3.3.CO;2-SSuche in Google Scholar

27. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Rodewald, U.Ch.; Hoffmann, R.-D.; Pöttgen, R. J. Solid State Chem. 2011, 184, 2731–2737; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2011.07.045.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Steinwand, S. J.; Hurng, W.-M.; Corbett, J. D. J. Solid State Chem. 1991, 94, 36–44; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(91)90218-7.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Nesper, R.; Wengert, S.; Zürcher, F.; Currao, A. Chem. Eur. J. 1999, 5, 3382–3389.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19991105)5:11<3382::AID-CHEM3382>3.3.CO;2-TSuche in Google Scholar

30. Slabon, A.; Cuervo-Reyes, E.; Kubata, C.; Mensing, C.; Nesper, R. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2012, 638, 2020–2028.10.1002/zaac.201200058Suche in Google Scholar

31. Vasquez, G.; Latturner, S. E. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6478–6485; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b02916.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Vasquez, G.; Wei, K.; Choi, E. S.; Baumbach, R.; Latturner, S. E. Crystal Growth Des. 2020, 20, 2632–2643; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.0c00012.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Voßwinkel, D.; Block, T.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2025, 80b, 79–84.10.1515/znb-2025-0011Suche in Google Scholar

34. Pöttgen, R.; Gulden, Th.; Simon, A. GIT Labor-Fachzeitschrift 1999, 43, 133–136.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Pöttgen, R.; Lang, A.; Hoffmann, R.-D.; Künnen, B.; Kotzyba, G.; Müllmann, R.; Mosel, B. D.; Rosenhahn, C. Z. Kristallogr. 1999, 214, 143–150.10.1524/zkri.1999.214.3.143Suche in Google Scholar

36. Palatinus, L. Acta Crystallogr. 2013, B69, 1–16.10.1107/S0108768112051361Suche in Google Scholar

37. Palatinus, L.; Chapuis, G. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, 786–790; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889807029238.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Petříček, V.; Dušek, M.; Palatinus, L. Z. Kristallogr. 2014, 229, 345–352.10.1515/zkri-2014-1737Suche in Google Scholar

39. Petříček, V.; Palatinus, L.; Plášil, J.; Dušek, M. Z. Kristallogr. 2023, 238, 271–282.10.1515/zkri-2023-0005Suche in Google Scholar

40. Bärnighausen, H. Commun. Math. Chem. 1980, 9, 139–175.10.1007/BF01674443Suche in Google Scholar

41. Müller, U. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2004, 630, 1519–1537.10.1002/zaac.200400250Suche in Google Scholar

42. Müller, U.; Wondratschek, H. International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. A1, Symmetry Relations between Space Groups; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2010.10.1107/97809553602060000110Suche in Google Scholar

43. Müller, U. Symmetriebeziehungen zwischen verwandten Kristallstrukturen, 2nd ed.; Springer Spektrum Berlin: Heidelberg, Germany, 2023.10.1007/978-3-662-67166-5_12Suche in Google Scholar

44. Flack, H. D.; Schwarzenbach, D. Acta Crystallogr. 1988, A44, 499–506.10.1107/S0108767388002697Suche in Google Scholar

45. Watkin, D. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 491–522; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889808007279.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Rodewald, U.Ch.; Pöttgen, R. Monatsh. Chem. 2011, 142, 219–224.10.1007/s00706-011-0450-5Suche in Google Scholar

47. Reimann, M. K.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2024, 79b, 113–120.10.1515/znb-2023-0106Suche in Google Scholar

48. Emsley, J. The Elements; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

49. Chevalier, B.; Decourt, R.; Heying, B.; Schappacher, F. M.; Rodewald, U.Ch.; Hoffmann, R.-D.; Pöttgen, R.; Eger, R.; Simon, A. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 28–25.10.1021/cm062168aSuche in Google Scholar

50. Cardoso-Gil, R.; Caroca-Canales, N.; Budnyk, S.; Schnelle, W. Z. Kristallogr. 2011, 226, 657–666; https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.2011.1392.Suche in Google Scholar

51. Schellenberg, I.; Hoffmann, R.-D.; Schwickert, C.; Pöttgen, R. Solid State Sci. 2011, 13, 1740–1747; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2011.07.001.Suche in Google Scholar

52. Donohue, J. The Structures of the Elements; Wiley: New York, 1974.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Pivan, J. Y.; Guérin, R.; Sergent, M. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1985, 109, 221–224.10.1016/S0020-1693(00)81774-0Suche in Google Scholar

54. Albering, J. H.; Jeitschko, W. Z. Naturforsch. 1992, 47b, 1521–1528.10.1515/znb-1992-1104Suche in Google Scholar

55. Chikhrii, S. I.; Kuz’ma, Y. B.; Davydov, V. M.; Budnyk, S. L.; Orishchin, S. V. Crystallogr. Rep. 1998, 43, 548–552.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure