AI regulation: Competition, arbitrage and regulatory capture

-

Filippo Lancieri

Abstract

The commercial launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 and the fast development of large language models have catapulted the regulation of artificial intelligence to the forefront of policy debates. A vast body of scholarship, white papers, and other policy analyses followed, outlining ideal regulatory regimes for AI. The European Union and other jurisdictions have moved forward by regulating AI and LLMs. One overlooked area is the political economy of these regulatory initiatives—or how countries and companies can behave strategically and use different regulatory levers to protect their interests in the international competition on how to regulate AI.

This Article helps fill this gap by shedding light on the tradeoffs involved in the design of AI regulatory regimes in a world where (i) governments compete with other governments in using AI regulation, privacy, and intellectual property regimes to promote their national interests; and (ii) companies behave strategically in this competition, sometimes trying to capture the regulatory framework. We argue that this multilevel competition to lead AI technology will force governments and companies to trade off risks of regulatory arbitrage versus those of regulatory fragmentation. This may lead to pushes for international harmonization around clubs of countries that share similar interests. Still, international harmonization initiatives will face headwinds given the different interests and the high-stakes decisions at play, thereby pushing towards isolationism. To exemplify these dynamics, we build on historical examples from competition policy, privacy law, intellectual property, and cloud computing.

Introduction

The impressive capabilities of recent artificial intelligence systems, in particular large language models, have taken the general public by surprise and triggered a global debate among policymakers on whether and to what extent artificial intelligence needs to be regulated. Potential targets of these regulatory regimes include protecting the privacy interests of consumers, preserving the incentives of creators and writers, avoiding biases and discrimination, ensuring free speech and democratic discourse, defending the interests of nation-states, and even ensuring the survival of humankind.

Governments, however, do not regulate in a vacuum. Regulatory interventions by one country may prompt other governments to adapt their own legal frameworks. They may also induce companies to adapt their business strategies to evade governmental mandates. These potential company responses trigger a dynamic interaction between different governments and companies to protect their interests in the face of a fast-moving regulatory landscape.

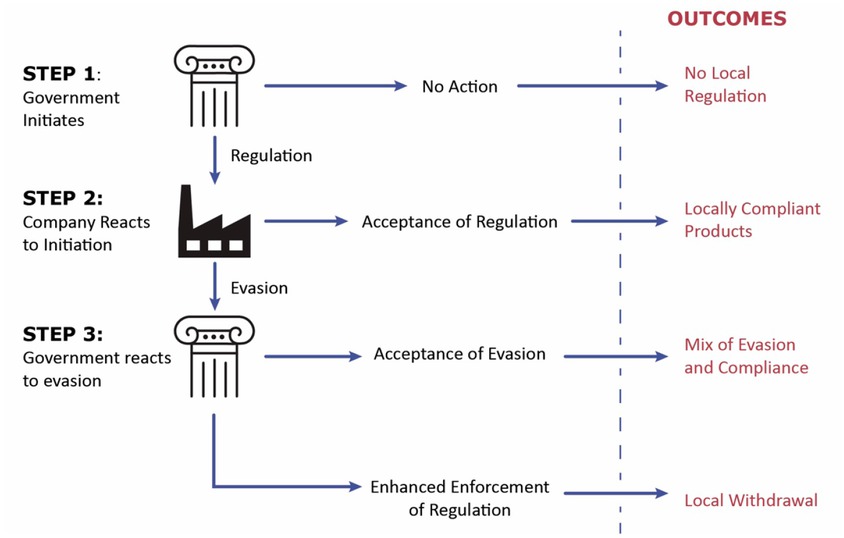

This Article explores the determinants and potential outcomes of such a regulatory “game,” looking in a forward manner to the case of AI technologies. It is divided into two parts. Part I.A. starts by developing a simple, three-step “model” of strategic interactions between governments and technology companies. This naïve model focuses only on local considerations; in other words, players cannot influence the regulatory regime in other jurisdictions. In step one, a government decides whether to regulate technology companies’ local conduct, which the government perceives as harmful to its citizens. In step two, depending on how drastically this regulation impacts business strategies, companies may decide to (i) adapt their products and services to comply with the legal mandates from step one or (ii) try to evade these obligations by engaging in regulatory arbitrage. In step three, the regulating government may either accept a certain level of company evasion, or it may ramp up its regulatory intervention by switching to a cross-jurisdictional regulatory regime. This game yields different outcomes that range from no regulation at all to compliance, successful evasion, or even companies’ exit from a given jurisdiction altogether.

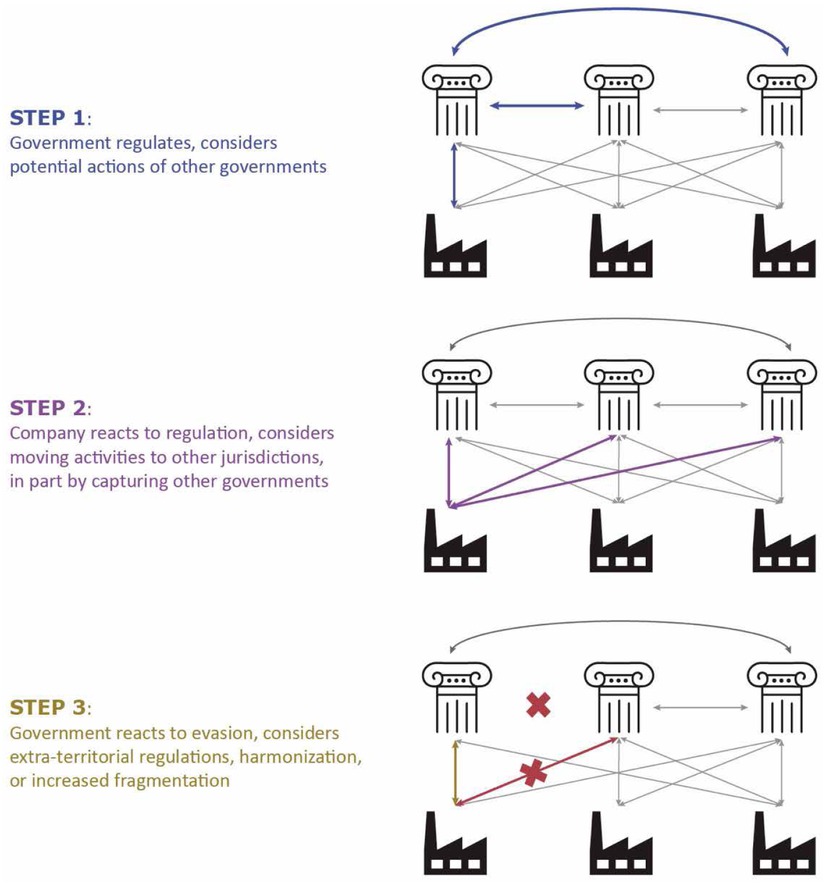

Part I.B allows participants in this regulatory game to engage with one another. This has the effect of relaxing two assumptions of the baseline “model.” First, companies can now capture regulators by sharing some of the rents of this corporate arbitrage with local jurisdictions, inducing the formation of low-regulation regimes. Second, certain technological advancements can trigger zero-sum international disputes between countries, prompting national governments to enact policies that place them ahead of the international competition, potentially triggering similar tit-for-tat reactions that lead to isolationism. These strategic interactions may ultimately lead to four different international governance arrangements, all with different welfare implications: (i) multiple local regimes; (ii) international harmonization; (iii) unilateral imposition (“Brussels effect”); or (iv) fragmentation (Splinternet). We use examples from the recent history of technology regulation—from the Google Books copyright dispute to antitrust policy, data protection policy, and cloud computing—to showcase what these different equilibria may mean in practice.

Part II applies this framework to the current global regulatory game of governing artificial intelligence. It starts by providing a short overview of the key building blocks of today’s foundational AI models, discussing how the most important bottlenecks are likely to shift from computational capacity to access to high-quality data. It then considers what this shifting landscape means for international attempts to regulate AI. Our framework indicates that jurisdictions such as the United States and the European Union will not succeed in either fully harmonizing their AI regulatory regimes or unilaterally imposing their rules on AI regulation (a “Brussels effect” of AI regulation). There is simply too much at stake for other countries to allow foreign jurisdictions to dominate the global AI regulatory arena. Rather, we envision a global regime for artificial intelligence that results in a mixture of fragmentation and occasional bursts of cooperation, with countries potentially opting to lower the overall quality of their endogenous AI models in exchange for relative superiority in this international fight.

I The “Model”: a Dynamic Game of Policy Decisions In (Digital) Regulation

There is increasing attention to the regulatory competition between governments and companies present in digital markets. For example, Anu Bradford’s book Digital Empires describes an international regulatory game that is played on two different levels. [1] First, governments (or empires) compete among themselves horizontally for the supremacy of their regulatory systems. Second, governments struggle to enforce their national laws against increasingly powerful and sophisticated technology companies—a process described as vertical, intra-jurisdiction competition. [2] Other scholarship on this regulatory game focuses on understanding how platforms exploit the legal and regulatory environment to promote their agendas, [3] or how regulators use different tools and respond to different societal pressures when enforcing digital laws. [4]

However, this growing literature lacks a more solid understanding of how governments and companies play this “regulatory game”: What regulatory tools do they employ, and how do these tools impact the likelihood that different outcomes will materialize? In the following, we explore how governments and companies actively exploit or generate gaps in public regulation to win strategic regulatory battles. We outline a dynamic, repeated game of local regulatory choices that unfolds in three sequential steps: (i) governments impose narrow regulation; (ii) platforms decide whether to comply or evade/arbitrage; and (iii) governments close loopholes, in our case by increasing the reach of their regulatory jurisdiction. In subsequent rounds of the game, other governments can react, with different equilibria arising.

Part I.A below describes a local version of these dynamics, where companies and governments do not behave strategically to advance their agendas vis-à-vis other global actors, but instead solely focus on considerations within their jurisdiction. Part I.B then adds global dynamics to this game, focusing on how international competition and regulatory capture alter interactions and lead to different regulatory outcomes.

A A “Local” Game of Regulatory Choices

In this “local” game, regulators and companies focus on the national dimension. They are aware of how the global environment is shaped by competition between countries but treat it as something that they cannot influence through their actions. We take this first step for simplicity, as it allows us to better outline the factors that can influence decisions on the scope of regulations.

1 Step 1: Regulating a Local Jurisdiction

Imagine that a given government must decide whether to regulate a new technology, reflecting its citizens’ beliefs about the potential benefits and harms posed by that technology. This government may decide that the new technology does not pose significant risks or that any intervention will be more harmful than the status quo, and therefore choose not to regulate it. If it decides to regulate, it must design the scope of the regulatory response.

In a normal first step, such a government would create a regulatory regime targeting behavior that takes place within their jurisdiction, aiming to modify the local impact of that new technology. For example, most environmental regulations are country-specific (tackling the sources of local air pollutant emissions in a given country), [5] and so are most criminal laws, labor laws, intellectual property regimes, or laws impacting freedom of expression. With some exceptions, the coverage of such regulations ends where a country’s borders end.

There are many reasons why a locally targeted approach is an optimal starting point for regulatory design:

Governments have a primary duty to protect their own citizens;

The enforcement costs of country-specific regulations are typically lower, as governments have a monopoly over the use of force in their own jurisdiction, as well as local agencies, staff, and other resources to effectively produce and process information on what is happening on the ground. Violations are therefore easier to detect and prosecute;

Most conduct can be effectively regulated at the domestic level without much loss to the effectiveness of the regulation; and

Extraterritorial application and enforcement of laws can be costly.

To understand these latter two points, we need to understand companies’ potential reactions—step 2 of this framework.

2 Step 2: Companies React: Compliance, Withdrawal, or Evasion

By definition, governmental regulations that impose local limits on the deployment of a new technology should require changes in how target companies conduct their businesses in that country, with a potential negative impact on such companies’ profits. In response, companies must decide whether to comply with or evade the new obligations resulting from these regulations (or a mix of both). [6] Evasion is defined here as the act of moving company activities to another jurisdiction with less onerous regulations for that given activity, still with the hope of supplying the product to customers in the original country. [7]

For now, let us assume the existence of a foreign country in the global environment with less onerous regulations. The corporate decision to comply with the new regulations imposed by country A, or to evade them by moving operations to country B, should be a function of how onerous the new regulation is to the company’s operations given the available evasion alternatives. Holding the onerous nature of the regulation constant, the costs for a company to evade regulation can depend on the production structure of a given good, including the costs of adapting the product to meet the new regulatory needs. [8] It also depends on how a product is delivered.

The costs of evasion may be higher, or even insurmountable, for companies providing goods or services that rely on large physical, indivisible assets located within a given country’s jurisdiction. That is because this physical presence increases companies’ exposure to the state’s police powers and potential forfeiture of the asset: some companies supplying physical goods might be able to move production elsewhere, but that would still require local imports. As governments can seize assets at ports or borders, evasion becomes mostly a function of the capacity of governments to identify and seize these physical goods. In this context, evasion may be profitable for small, easily disguised, and highly profitable goods such as drugs, but more difficult for bulkier, easily identifiable goods such as cars or construction materials. [9]

The costs of evasion, however, are much lower for the growing class of intangible goods and services characterized by low marginal reproduction costs and nonrival use. [10] These digital products or services can rely on the decentralized, difficult-to-control nature of the Internet to be supplied at a distance, facilitating decisions to engage in evasion. [11] There are multiple examples of this type of arbitrage. Companies have long offered gambling services online, even in jurisdictions where the practice is illegal—and while blocking these websites is not impossible, [12] it is difficult to implement and may have side effects (such as a need to centralize Internet provision to enable such blocking). [13] Google Books is another interesting example: when launching the product, Google ensured that the scanning of the books takes place in the U.S. so that Google could rely on the fair-use defense that U.S. copyright law provides against claims of copyright infringements. This strategy proved successful. The company successfully defended Google Books against copyright infringement claims in the U.S. under the fair-use doctrine, [14] while evading copyright liability in the EU: as the potentially copyright-infringing acts did not take place in the European Union, Google avoided EU copyright liability due to copyright’s territoriality principle. [15] While the service itself—Google Books—was accessible from the EU, it was only the “training” of the service (here: book scanning), not the deployment of the service (here: display of book snippets), that could have triggered EU copyright liability. Google arguably managed to evade that liability by engaging in product development location arbitrage. [16]

Sometimes regulations are so onerous and the costs of evasion so high that companies withdraw from a market. We explore this reaction in more detail in Part I.B below.

All in all, companies have differing economic incentives to engage in evasion when a new regulation significantly impacts their business. However, evasion seems to be a relatively rare scenario: firms—even those that deliver digital goods—do not always shift production to different jurisdictions whenever a new regulation is passed. As step 3 outlines, that is partially because firms understand that governments have powerful tools at their disposal that can make such evasion strategies even costlier.

3 Step 3: Regulators React to Evasion, Including by Adopting Extraterritorial Regulations

If companies choose to evade regulation, governments must then subsequently choose whether to tolerate this evasion or respond in kind by ramping up the regulatory regime. [17]

Detecting and addressing evasion at the local level may itself be costly. Building on the above example, identifying illegally imported drugs can be a difficult task that requires scanning the millions of products entering national ports (among others), making enforcement expensive. Technology can sometimes make it easier for authorities to detect violations—for example, AirBnB is prohibited from operating in some jurisdictions, and because its business model requires disclosing the locations of the rental homes it offers, regulators can rely on automated tools to detect and thwart evasion. But often there is no technological silver bullet to ensure appropriate enforcement.

An alternative (or complement) can be to expand the scope of the legal regime: governments—especially those of large countries [18]—may discourage entities from moving their operations abroad by establishing that their regulations also cover activities taking place outside of their direct jurisdiction. This cross-border shift helps close some simple loopholes, as companies can no longer escape regulation by simply moving certain activities to a different geographic location (as in the Google Books example).

Antitrust laws and the U.S. Cloud Act exemplify how corporate evasion can justify an extraterritorial shift. Antitrust laws began by covering solely violations that took place within a given country’s jurisdiction. The growth of international commerce and international cartels, however, led authorities in the U.S. and the EU to move towards an extraterritorial application of their laws, which they called an “effects-based approach.” [19] This new system allowed jurisdictions to prosecute cartel agreements whenever the net result of such agreements was an increase in domestic prices, no matter where the actual violation of the law (in this case, the agreement to raise prices) took place. Similarly, the U.S. CLOUD Act requires U.S.-based companies to provide American law enforcement agencies with any data they have stored in their servers—if so requested by a warrant or subpoena—no matter where the data/server is geographically located. [20] Congress passed the CLOUD Act in 2018 as an explicit anti-evasion measure, motivated by a 2nd Circuit court ruling that Microsoft was not required to provide the FBI with emails that were stored in data centers in Europe.

The Different Steps of the Local Regulatory Game

End-States of the Local Regulatory Game

The local regulatory game we have outlined so far is an iterative regulatory game: actors may proceed through these three steps multiple times until a local equilibrium is established. Still, there are only a limited number of outcomes:

Outcome 1: No local regulation – Governments decide not to regulate at step 1, either because they believe the technology is not harmful or because they believe that the costs of policing evasion are not worth the gains.

Outcome 2: Locally compliant products – Companies comply with local regulations, either because the absolute costs of evasion are too high in step 2 or because they understand that governments can successfully prevent evasion by expanding their regimes beyond their own territory in step 3.

Outcome 3: Mix of evasion and/or compliance – Some companies comply with regulations while others successfully evade them (depending on business structures). Governments are uncapable of fully blocking evasion by investing in enforcement efforts or by reforming the legal regime in step 3, so they accept the existence of noncomplying products.

Outcome 4: Local withdrawal – Companies decide to withdraw from the market, either because the business costs of evasion are too high in step 2, or because they believe governments will successfully block evasion in step 3.

B A Global, Multiplayer Scenario: Corporate Capture and Strategic Behavior

Part I.A presented a baseline local scenario in which governments act in response to the policy demands of their own citizens and the realities of regulation, ignoring whether other governments from other countries would make simultaneous moves. In this local scenario, companies cannot directly influence the decisions of different governments to set stricter or laxer regulatory regimes, and governments are not particularly concerned with international competition.

This scenario is useful for understanding the basic moves available to our “players.” Yet, it provides limited insights as to what equilibria will emerge at the global level, as international interactions between countries create additional incentives for strategic behavior. These are important: in their absence, most governments would have an incentive to adopt extraterritorial regulatory regimes to make corporation evasion costlier. Extraterritorial laws, however, are the exception, not the rule. Part I.B helps explain why by also outlining a three-step game with four end-states.

1 Step 1: Governments Again Start with Local Regulations

Regulators still decide whether to regulate a new technology based on their perceptions of whether or not the new product is harmful. The incentives here are largely the same: countries start by regulating local conduct through local laws, because if such local regulation is successful, they can receive the benefits of the regulatory regime without incurring the costs of having to police evasion.

However, regulators must also consider that other jurisdictions are simultaneously making the same determinations.

2 Step 2: Companies Comply or Evade. Regulatory Capture Influences Decisions

As in the local regulatory game presented in Part I.A, companies are now faced with the choice of compliance or evasion. However, international competition between countries allows companies to influence the regulatory rules of other jurisdictions by sharing part of the arbitrage rents these companies gain when they move their operations to other “low-regulation” jurisdictions. This is a form of regulatory capture, [21] but one that allows low-regulation countries to generate negative externalities to other countries, as they appropriate part of the evasion gains. Ireland, for example, has historically pitched itself as a low-tax, low-regulation jurisdiction within the EU. As more tech companies settled there—employing locals at high salaries and increasing Irish exports—Ireland was increasingly encouraged to cater to the local industry by further lowering taxes and regulatory requirements while externalizing the costs to other EU countries. [22] This has prompted other countries, such as Luxembourg and The Netherlands, to match incentives. [23]

The relative positions between countries start mattering more. As a result, the possibility of capture increases the likelihood of arbitrage, as companies can now directly induce the formation of low-regulation regimes around the world from where they can base their operations.

3 Step 3: Governments React: Extraterritorial Regulations, Harmonization, or Increased Fragmentation

The fact that capture is a possibility does not mean that it always happens. [24] Governments continue to have the ability to resist capture or arbitrage by increasing enforcement against companies that do not comply with their laws or by adopting extraterritorial regulations.

In other words, in the regulatory game we outline, regulators also behave strategically in at least two ways. First, they can continue to transition to an extraterritorial regime that diminishes the incentives for companies to move their operations abroad—the gains from arbitrage have to be very large for the evasion to be profitable. Second, capture can also lead to an inverse result, [25] that is, regulators shift their local laws to drive fragmentation, hindering international imports and favoring local industries.

To understand these dynamics better, one needs to consider the importance of scale for a given industry. If multiple countries employ extraterritorial regulations, a product or service relying on this technology might be subject to multiple (and often conflicting) overlapping obligations that companies cannot evade by moving the location of their operations.

This conflict of laws creates costs for companies in at least three different ways: (i) companies must spend resources and time to simply understand the different legal requirements (transaction costs); (ii) companies may be forced to adapt their product/service offerings to the requirements of the different jurisdictions, losing economies of scale typically associated with the supply of a homogenous good; and (iii) companies may lose benefits from network externalities, as overlapping regulations may force them to create regional versions of their services. For simplicity, we will refer to those costs as the loss of economies of scale, and we assume that losing economies of scale will make the underlying products that are regulated worse in quality and/or more expensive to supply. The more divergent the regulations across countries, the less scale a given company can achieve.

As discussed in Part I.A, different business models are differently impacted by losses in economies of scale. For the purposes of the regulatory game, what matters is the interaction between the business model and the level of regulatory divergence. Sometimes, regulatory divergences are small and scale is not important for the delivery of the underlying product, so the overall “tax” on a given company that tries to offer products in both jurisdictions is small. The U.S. and Europe, for example, have different consumer protection rules, [26] but many similar products are still sold across borders with changes in warranties and disclosures.

At other times, regulations differ significantly, forcing major product restructurings—multinationals engaged in international mergers are regularly required to divest specific assets in specific jurisdictions to appease local requirements from antitrust authorities. [27] Ultimately, extreme divergences in regulations may induce companies to exit a jurisdiction altogether—Google and Meta, for example, left China because they did not want to comply with some of the regulatory requirements imposed by the Chinese government. [28]

Importantly, the opposite dynamics can also happen. That is, if scale is very important to business models, large companies may voluntarily adopt strict standards or lobby countries to harmonize their regulatory regimes through international agreements. [29] We further explore these outcomes below.

As governments decide whether to adopt extraterritorial or local laws, they balance these considerations, and their perceptions reflect the different forms of lobbying they are subject to.

Figure 2 depicts the different steps of this game.

The Steps of the International Multiplayer Regulatory Game

4 Four Potential End-States

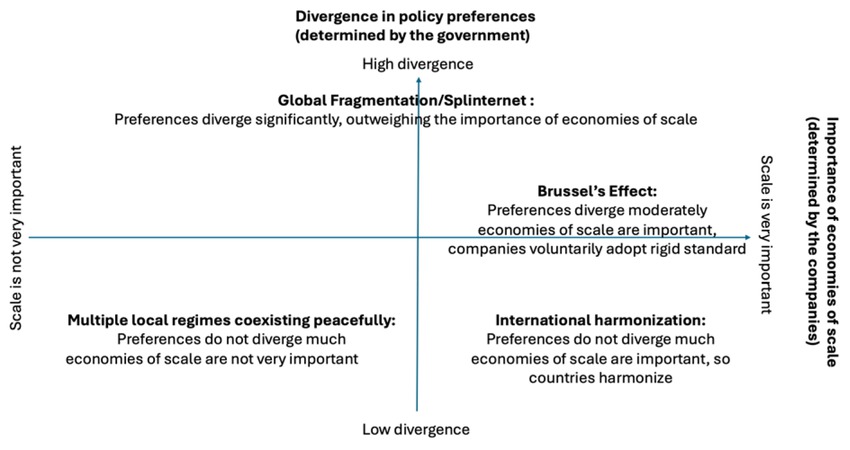

The ultimate result of the global regulatory game we have outlined depends on how much countries diverge in their initial policy preferences and how important scale economies are for companies’ operations. Figure 3 depicts the four most likely outcomes, mapping them on more traditional international governance arrangements: (i) the prevalence of multiple local regimes; (ii) international harmonization; (iii) unilateral dominance; and (iv) global fragmentation.

Which of these outcomes emerges for a particular case of technology regulation will depend on the relative benefits and costs to governments that stem from regulating the technology locally or globally, and to companies from abiding by or evading these regulations. These governance arrangements also have potentially different welfare outcomes.

Four Governance Outcomes

More specifically:

Multiple local regimes are the good version of a multipolar world. In this equilibrium, multiple local regimes coexist because (i) countries accept some levels of arbitrage to avoid a tit-for-tat war, and (ii) the costs of adapting products to local requirements are not high enough for businesses to voluntarily export stricter standards.

This system preserves sovereignty and potentially high levels of welfare, as it enables some differentiation according to national preferences without significant losses as to scale. Consumer protection rules are good examples of multiple local regimes coexisting. [30]

International harmonization occurs when countries and companies recognize that fragmentation is costly, pushing societies to bridge differences in regulatory preferences to safeguard economies of scale. The likelihood of harmonization is a function of how costly the fragmentation is vis-à-vis how different countries perceive the best mitigation strategies for the harms generated by the new technology.

Assuming that harmonization decisions are voluntary and well-informed, this should be a mostly welfare-enhancing outcome, as it preserves national sovereignty and scale. One example of this process is the evolution of antitrust policy. The rise of antitrust regimes around the world after the fall of the Soviet Union led to increasing conflict between different jurisdictions. These conflicts became increasingly costly—in particular in merger review. As a solution, countries like the U.S. started sponsoring the expansion of international bodies focused on coordinating antitrust policy, such as the International Competition Network and the OECD Committee on Antitrust Policy. [31] These were attempts by a leading jurisdiction to foster international harmonization by “educating” developed and developing jurisdictions on what a sound antitrust policy was supposed to look like. [32] Similar beliefs that harmonization would be more beneficial than a tit-for-tat war led to the expansion of the World Trade Organization and the lowering of trade barriers. [33] In related fashion, the EU actively uses bilateral and multilateral trade agreements to extend its regulations to other jurisdictions. [34]

Unilateral imposition of a regulatory regime (Brussels effect): In some cases, policy divergences prevent international harmonization through governmental cooperation. An alternative outcome, then, is for companies to sponsor this harmonization by adopting a single product/service in all the jurisdictions where they do business, regardless of the local requirements. This is the so-called “Brussels effect,” which takes place when a large country with significant regulatory capacity adopts a strict regulatory regime that governs a mostly inelastic and indivisible asset. [35] Companies, then, decide that economies of scale are more important than regulatory fragmentation and voluntarily adopt the stricter regulation in a way that leads to a de facto leader in international regulation. The divergence in policy preferences, however, is not so high that other countries force companies to adhere to their own laxer national regulatory standards. One example of the “Brussels effect” in action is Apple’s voluntary worldwide adoption of USB-C type connectors for all its iPhones from model 15 onwards, which took place after the EU imposed the use of such chargers inside the bloc. Apple could have maintained its Lightning chargers elsewhere but voluntarily decided not to. [36] As other countries did not express a strong preference for the Lightning charger, the EU standard became the de facto global standard.

The welfare impacts of this process are ambiguous. If economies of scale trump the losses generated by the lack of regulatory divergence, then welfare goes up, while the opposite can also be true.

Fragmentation (Splinternet): A final potential outcome is pure fragmentation, with countries insisting that their rules must apply to their own jurisdiction no matter the losses to economies of scale that are generated by global convergence. [37]

For this outcome, welfare implications are again ambiguous. There are many good reasons why countries may determine that certain goods must be produced within the country and require that they comply with local laws, regardless of the costs to businesses. Companies, however, may lose so much scale by having to adapt their products to local requirements that they may end up pulling out of the market altogether. This can lead to higher prices and/ or lower quality. The welfare outcomes will depend on whether the gains from the imposition of the national law trump the losses in scale caused by the regulatory fragmentation. Content moderation laws (broadly defined) provide a good example of these dynamics. Google and Meta, for example, have pulled their services out of jurisdictions such as Russia, China, Spain, Australia, and even Canada rather than comply with local regulatory requirements. [38] Meta is also being forced to change part of its business model in Europe, adopting a subscription model in response to local regulatory requirements regarding privacy. [39]

It is worth noting that these four “outcomes” are not categorical or permanent—they are a stylized representation that should help us better understand the dynamics that may arise as a result of an iterative process of regulatory competition and evasion. Many regulatory regimes in the real world will be mixed: a certain level of harmonization combined with a certain level of fragmentation. It is also possible that the increasingly costly nature of fragmentation will push countries to harmonize certain aspects of their regulatory regime or accept some levels of unilateral imposition, among others. For our framework, this increasingly costly nature of fragmentation over time can be understood as either countries or companies acquiring better information on the costs and benefits of their positions, or as an external shock that disrupts the equilibrium and induces players to rearrange their positions (like the adoption of a new technology that resets the original game).

II Applying this Framework to AI Regulation

A A Shifting Landscape for Foundational AI Models: From Computing Power to Data

To understand the implications for regulation and opportunities for arbitrage in the area of artificial intelligence, we must define some terms and briefly review how the technology works and is used. This Part briefly introduces artificial intelligence concepts and then proceeds to an overview of the large language models and AI systems that use them. [40] Understanding the underpinnings behind the technology helps us understand how regulatory games may evolve in the future, and in particular what policy tools governments and companies will employ to push their respective agendas.

The term ‘AI’ has become something of a buzzword, so it is important to begin by defining what AI systems are. The OECD defines an AI system as “a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.” [41] This definition is intentionally broad and also encompasses simple rules-based systems that are not at the focus of current regulation. Beyond this structure of an agentic system that generates outputs based on inputs and an objective, the AI systems that are currently at the focus of regulation have two other key features that are relevant to the regulatory context: development of the models via a machine learning process, and knowledge representation.

Broadly speaking, machine learning is simply the process of allowing an algorithm to learn patterns from a corpus of data. [42] The process of learning is sometimes referred to as ‘training.’ In this process, a piece of software is given some goal, represented as an objective function, that it is asked to maximize. By looking at many data points, more complex patterns can be learned. There is a roughly linear relationship between the size of the training dataset and the time required to extract the most information from the training data; this means that the more data you have, the longer it may be useful to train an algorithm on that corpus. [43] Because of this somewhat linear relation between data, time, and training capacity, the amount of compute used to train a model, typically measured in Floating Point Operations (FLOPs), has become a benchmark measure of foundational models. [44]

A second key feature that distinguishes AI systems from other algorithmic processes is their knowledge representation, typically encapsulated in their models (although not exclusively). Foundational models are ones with knowledge representation that is both large and broad. For example, GPT-4 is a foundational, general-purpose large language model (LLM) that contains a broad representation of human language usage, particularly in English. [45] It is not focused on any specific purpose, which is both a strength and a limitation. Such foundational models are trained on enormous amounts of data using a correspondingly large amount of computational resources. The AI system Chat-GPT uses a version of GPT-4 (as well as other GPT models) that has been fine-tuned, or further trained for a specific application, for good performance on conversation tasks. But these specifically tuned models alone will not perform well for the many tasks that users wish to use Chat-GPT for. Therefore Chat-GPT and the fine-tuned models that back it have additional knowledge representation of several additional areas, like which topics are or are not offensive in the course of a conversation, basic facts that a user might ask about (perhaps stored in a knowledge graph), what topics Microsoft Open AI wants Chat-GPT to avoid as a matter of policy, and the history of that user’s prior interactions in the conversation.

There are currently two major barriers that face any company that wishes to train foundational models. The first is training data. Much of the improvement in performance of the latest general-purpose models such as GPT-4 over earlier models has been driven by the increase in the data the model was trained on. [46] The second barrier is graphical processing units (GPUs), the type of chip that is most commonly used to efficiently train the deep-learning models that have become most performant. It has been estimated that current models are somewhat undertrained, meaning that if they had been trained on the same data but for more cycles, they could perform better. [47] This is likely due to the current extremely restricted availability of GPUs (at least as of the time of this writing). These limitations impact what models can be built and how well they can perform in different ways.

Of the two limiting factors, a lack or inaccessibility of training data is the most fundamental. Even the largest AI systems can only replicate and generalize from patterns found in their training dataset. [48] This means that if a type of data is missing from the training dataset or some portion of the training data is systematically biased, those areas of content will similarly be missing from or biased in the system’s outputs. This is why companies developing LLMs have invested significantly in labeling their existing data to better harness the information it contains, and in creating new, proprietary datasets to fill in the gaps of sparse data, such as images of racial minorities. Augmenting training datasets in this way is a slow and labor-intensive process, but there is no alternative for foundational models that seek to encapsulate a broad range of knowledge and offer good performance on a broad range of tasks. To achieve the best results, model trainers must also prune their training data. Significantly duplicated data (i.e., many copies of the same document or image) causes memorization and harms general performance. [49] And of course, aside from the challenges of pruning a dataset and labeling niche data, just collecting the vast amounts of data required to perform the initial training of a performant LLM is in and of itself an expensive undertaking.

For human-related training data, particularly human-generated text and visual representations of people, this problem of assembling relevant training data is not a one-time, limited cost. In addition to the ever-changing nature of the topics we discuss and themes of our media, the way we use language and the way we present ourselves is also constantly changing. This evolution of presentation is referred to as semantic drift in language and fashion in visual presentation. [50] Between the ever-changing nature of how we communicate and what we communicate, building training datasets for use in large foundational models should be thought of as a task of maintenance as much as of initial assembly. This changes the cost structure of data assembly: it is not a one-time expense that can be amortized over the lifetime of a model, but rather should be thought of as an ongoing running cost. Of course, some companies already must absorb this cost in the course of their other business operations. Companies in this position will be at a significant advantage, in terms of both the time it takes to bring new models to market and the cost structure of the models they create.

The second barrier—limited access to GPUs, the chips used to train large models—is likely to be easier to solve. Supply shortages have periodically plagued Nvidia for years but were most severe in 2022 and 2023. Most chips of this type are produced by one foundry: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). TSMC makes GPUs (as well as other chips) for several chip companies, but Nvidia is by far the market leader in designing GPUs. Nvidia’s GPUs are currently considered to be significantly more efficient at training large models, so customers are willing to endure longer waiting times and to pay significantly more for Nvidia hardware as opposed to other manufacturers. [51] The most relevant limitation on expanding chip production capacity is the availability of expertise. GPUs are built in highly specialized facilities that few companies have the expertise to construct or operate. Designing these chips is similarly a highly specialized discipline, with nearly all the designers and engineers involved in such work being employed by a handful of firms. These create technical barriers that currently cannot be solved by simply increasing the resources that a given country invests in the construction of foundries and the design of GPU chips. [52]

Thus far, we have primarily discussed large foundational models that encapsulate broad knowledge of how humans use language, what human voices sound like, or what our visual model looks like. In addition to requiring significant resources to run, these general models often do not perform well on highly specialized tasks. This is because of a lack of training data about that specific task and also because maximizing performance on a very specific task nearly always hurts performance on a general task. As already discussed, fine-tuning can be used to adapt a general model to maximize performance on a specific task, typically by doing additional training with a specialized dataset. This is commonly performed by retraining only a portion of the base LLM on new data for reasons of cost and efficiency. Fine-tuning is becoming a common enough practice that several general-purpose models, including GPT-4 and Llama, now offer APIs specifically to allow customers to create fine-tuned derived models.

While only a few companies have the resources, both in terms of data and in terms of GPUs, to build general-purpose AI models, fine-tuned models built for specific domains and specific tasks are being built by tens of thousands of companies globally, and this number is expected to continue to grow for years to come. Companies that have specific proprietary data that can be used to fine-tune models and the resources to build them will be at a distinct advantage over those that do not in making this next technological leap.

B Connecting the Technical Dynamics with the Policy Game

1 Complex and Fluid Multi-Agent Game

The regulation of AI is a fast-moving field, and one where countries and companies participate in a dynamic game that can be partially rationalized by the “model” outlined above. Governments use a combination of regulatory regimes and subsidies to ensure control over the different layers that make up the AI supply chain (in particular compute capacity and data). Companies try to pit governments against one another to gain additional leverage in international negotiations and to weaken restrictions that they see as detrimental to their business models. This complex game, which is also influenced by government notions of “strategic autonomy,” is shaping the current evolution of AI regulations and technologies. [53]

Let us start with the governmental side of the game. Anu Bradford’s work has detailed the geopolitical competition between the U.S., the EU, and China to impose their different visions for digital regulation. [54] This competition manifests itself in measures such as the U.S. working with the EU to restrict China’s access to high-end GPUs and other advanced AI chips, [55] or the U.S., the EU, and China entering into an international competition—and potentially a zero-sum game—to provide subsidies for companies willing to move the production of such high-end chips to their own jurisdictions. [56]

A similar dynamic has begun to emerge in data access. China has long recognized the key role of data in the training of AI models, and has restricted access to certain data of Chinese citizens to companies aligned with the Chinese government’s view of the world. [57] While the Western world has not gone that far, it is worth noting the rapid decline of open-access data that has been previously used to train AI models. [58] This decline is triggered by companies trying to better monetize their valuable data through the imposition of technical and legal restrictions that prevent the scraping of their websites, combined with selected licensing agreements that grant access to a database in exchange for monetary payments. [59] This blocking of data access for commercial purposes, however, also creates the infrastructure that Western governments may need to provide selective access to their own databases, and it is no surprise that controlling and enabling access to data is at the center of the AI industrial policy of the EU through the Data Act, the AI Act, and others. [60] Military experts in the U.S. are already talking about restricting Chinese access to American-controlled data, [61] and the U.S. government is starting to take steps in this direction (even if AI is not the main focus). [62]

Companies understand that this level of international competition for relative and absolute supremacy in AI technologies provides them with an opening to shape regulation to their advantage. For example, European companies have used this international competition to shape the drafting of the EU’s AI Act to make it more EU-company-friendly, and a coalition of companies is using this international competition to push for the reforms of other EU regulations that they dislike—such as data privacy laws. [63] Governments are increasingly responsive to these pleas—a 2024 high-level expert report commissioned by the President of the European Commission to shape the evolution of European competitiveness denounced the GDPR and the AI Act as overly complex and restrictive of AI advancements, calling for their reform to safeguard Europe’s position in the “global AI competition” shaped by “winner takes most dynamics.” [64] In the U.S., tech companies have also used the innovation race to successfully pressure California’s governor to veto a 2024 bill that would have imposed restrictions and safeguards on the development of AI models in the state. [65]

This dynamic game is prompting some countries to impose their will over other countries, and some companies to shape the evolution of the regulatory systems. The game also shapes the way laws are drafted and how companies react to these laws. For example, it is interesting to note that the EU AI Act is a cross-jurisdictional regulatory regime where providers of AI systems may be subject to its rules as long as there is an impact on the EU market, independent of where they are physically located. [66] This decision can be seen as both a push to eliminate opportunities for regulatory arbitrage and an attempt by the EU to emerge as the leader in the international debate on AI regulation. The EU is trying to rely on a “Brussels effect,” de facto exporting its rules through voluntary adoption by technology companies. [67] Companies, however, are actively pushing back through the use of mechanisms described above. This may not only include lobbying complemented by unilateral threats—both Apple [68] and Meta [69] have opted not to release their latest AI models in Europe “due to the unpredictable nature of the European regulatory environment.” It may also include the exploration of legal uncertainty under the AI Act. While the AI Act, for example, requires providers of general-purpose AI models to “put in place a policy to comply with Union law on copyright and related rights” (Article 53 (1)(c) AI Act), it is an open question whether EU copyright law actually covers machine-learning training activities that take place outside the EU. As copyright’s territoriality principle may put a limit to the AI Act’s extraterritorial reach, companies may at least have an incentive to move any training activities outside the European Union, thereby still engaging in regulatory arbitrage. [70]

2 The Likely Outcome: Fragmentation with Occasional Pushes for Harmonization

As the simple model we developed in Part I outlines, the final outcomes of the regulatory AI game between a country and companies depends on how a government perceives the relative costs and benefits of local versus extraterritorial regimes, and on how companies perceive their ability to comply with or evade such regulations. These decisions are partially shaped by a government’s differing preferences on how important it is to obtain relative or absolute superiority vis-à-vis international competitors. Once one introduces international competition between countries, whether a government will push for international harmonization or fragmentation of rules or whether it will try to expand the reach of its own regime through extraterritorial application will again depend on its preferences vis-à-vis the technology it is attempting to regulate.

While this regulatory game can lead to various equilibria—ranging from the dominance of one regime over fragmented national regimes to a harmonized global regime—we stipulate that for AI technologies, neither a Brussels effect nor global harmonization is likely to emerge. [71] Current actions by different players increasingly indicate that being a technology leader in AI systems is of such vital importance that governments are willing to use a combination of regulation and their physical control over infrastructure as a lever to shape AI governance in their favor. When European AI regulation can be understood in terms of achieving “AI sovereignty,” other countries will consider how this technology and its regulation impacts their own sovereignty as well. [72] The more the regulation of AI technologies and the fencing off of foreign influence over these technologies become matters of national security, the more likely we are to end up in a world of policy fragmentation. [73] In our model, this means that governments’ strong policy preferences outweigh considerations for the global availability of AI technologies.

For some technologies—in particular technologies that are subject to strong economies of scale and network effects—fragmented regulations impose a significant cost. If different countries regulate social media in different ways and prevent the exchange between users of different social media in different regions of the world, this hampers the potential these media have for global connectivity. As the consumption of AI systems is much less subject to externalities in consumption, fragmented AI regulations may appear less worrisome than fragmented social media regulations at first sight. However, a world of AI fragmentation will not come without costs—and these may be significant. As outlined in Part II.A, current AI models require significant scale to operate efficiently. As these costs grow and lead to lower-quality models, industry players and even governments themselves may push for certain levels of harmonization that can enable gains in economies of scale. This will be contrasted against the level of policy divergence between different countries. Ultimately, the less likely an initial policy divergence between the agents, the more likely that some form of harmonization will take place. In practical terms, this may mean, for example, that the United States and European countries will achieve a certain level of harmonization as a way to facilitate cooperation between their agents, thereby increasing the costs of the isolation imposed on more important adversaries such as China. [74]

If this is the case, what we may ultimately witness is a dynamic game marked by bursts of fragmentation in certain areas where autonomy trumps scale (e.g., chip production or even privacy regulation), [75] with the formation of certain and restricted regulatory blocs that enable countries to tap into economies of scale that are key for certain applications. One risk here is that companies may successfully pit governments against each other in a race to the bottom that ultimately weakens the nascent regulatory system for AI—a process we are starting to witness in the push against privacy protection in AI systems and against AI safety laws.

As our discussion indicates, we are skeptical that a more cooperative equilibrium such as a broad system of international harmonization will emerge in the area of AI regulation. This would require changes in the policy divergences between countries—say, for example, a growing international consensus that AI models are indeed a threat to mankind that justifies the adoption of international safeguards similar to those imposed on nuclear weapons. It seems that, at least for now, mankind has not arrived at any such agreement.

Conclusion

This Article has focused on better understanding the forces that drive governments’ decisions on whether to regulate a technology with local and international reach, and companies’ decisions on whether to comply with or evade such regulation. We explored examples of technology regulation where governments focused on locally applicable obligations (as in the case of Google Books), and others where governments decided to regulate conduct irrespective of where it takes place (as in the case of antitrust or the U.S. Clouds Act). We provided examples of company strategies where companies attempted to evade the reach of regulatory regimes (as in the case of government access to email infrastructure abroad, before the enactment of the U.S. Clouds Act), and others where companies voluntarily subjected themselves to a particular regulatory regime on a global basis even though they were not required to do so (as in the case of universal chargers for cellphones).

Today, policymakers and scholars speculate as to how the competition between countries and investment decisions by companies will shape the nascent regulatory regime for AI technologies. Our framework indicates that the near-term outcome will be an internationally fragmented system that is complemented by occasional bursts of cooperation.

We arrive at this conclusion by developing a three-step model of regulatory choices in which governments decide whether to regulate a technology on a local basis; companies then decide whether to comply with or evade this regulation; and governments then decide whether to fight potential arbitrage by switching to a cross-jurisdictional regulatory approach. This interaction between various governments and various companies may then lead to various outcomes, ranging from a fully fragmented regulatory regime to a fully harmonized regime with global reach. While we use this model of regulatory choices to explain and predict government strategies in the area of AI technologies, we believe that it can be used to understand regulatory regimes of other existing or emerging technologies as well.

© 2025 by Theoretical Inquiries in Law

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- AI, Competition & Markets

- Introduction

- Brave new world? Human welfare and paternalistic AI

- Regulatory insights from governmental uses of AI

- Data is infrastructure

- Synthetic futures and competition law

- The challenges of third-party pricing algorithms for competition law

- Antitrust & AI supply chains

- A general framework for analyzing the effects of algorithms on optimal competition laws

- Paywalling humans

- AI regulation: Competition, arbitrage and regulatory capture

- Tying in the age of algorithms

- User-based algorithmic auditing

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- AI, Competition & Markets

- Introduction

- Brave new world? Human welfare and paternalistic AI

- Regulatory insights from governmental uses of AI

- Data is infrastructure

- Synthetic futures and competition law

- The challenges of third-party pricing algorithms for competition law

- Antitrust & AI supply chains

- A general framework for analyzing the effects of algorithms on optimal competition laws

- Paywalling humans

- AI regulation: Competition, arbitrage and regulatory capture

- Tying in the age of algorithms

- User-based algorithmic auditing