Here, There, Nowhere: Urban Eviction as State Erasure of Roma Rights and Heritage between Bulgaria and Germany

-

Francesco Trupia

Francesco Trupia is an adjunct researcher at the Faculty of Humanities (Collegium Maius) at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland, and a research fellow at the CEU Democracy Institute in Budapest, Hungary. His research focuses on the intersections of democracy, memory, and political participation of minority groups in Southeastern and Eastern Europe. For the last ten years, he also has worked as a policy analyst. He is currently a member of the 9th Cycle of the Young Academics Network at the Foundation for European Progressive Studies in Brussels.

Abstract

The latest urban eviction of dwellers from Sofia’s district of Zaharna Fabrika, home to one of the oldest Roma settlements in the city, has shone a spotlight on an “archipelago” of residential clusters in which spatial confinement and the steady erosion of basic rights wall off Roma communities and shrink their space for political participation. In his commentary, the author advances an intersectional reflection that foregrounds the deep-seated anti-Roma discourse and neoliberal urban replanning – phenomena that both had a particularly significant impact on the Bulgarian Roma and fostered far-right violence. Based on previous fieldwork and qualitative studies, this article highlights how the neoliberal restructuring and rescaling of cities drive the patterns of migration from Southeastern to Northern Europe, while the far-right’s anti-migration discourse is taking root within urban migrant/minoritised spaces.

In 2025, just before Orthodox Easter, hundreds of Roma were forcibly evicted and displaced from their homes in the district known as the Zaharna Fabrika, home to one of the oldest Roma settlements in the city. Many, including pregnant women and children, were left with no choice but to live in makeshift tents, amid the ruins of their bulldozed houses.[1]

The hardships of homelessness ultimately far surpassed the poor living conditions identified by local authorities as justification for demolishing the illegal dwellings. Ironically, the eviction of all Roma families from the Zaharna Fabrika district was carried out in blatant defiance of interim measures put in place four days earlier by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which had stipulated that no homes should be demolished until the state had provided alternative housing for those affected.[2]

When rumours regarding the potential relocation of the evicted Roma community in nearby Zaharna Fabrika began to circulate, (white) Bulgarian citizens in the district of Lyulin, the largest residential complex in Bulgaria, promptly protested against such a plan. The district mayor, Georgi Todorov, from the liberal “We Continue the Change – Democratic Bulgaria” party (Prodalzhavame Promyanata – Demokratichna Balgaria), took to the streets along with a substantial number of other residents chanting: “We are all Lyulin” and emphasising that “Lyulin is not, and will not become, a ghetto”.[3]

Meanwhile, the pleas of activists and other Roma practitioners highlighting the lack of access to basic sanitation and healthcare fell on deaf ears at both the municipal and the national level. The ensuing solidarity and fundraising campaigns paradoxically repositioned the Zaharna Fabrika community, and the Roma minority in general, as internal and oriental others at both the local and the wider European level. The persistent housing insecurity faced by the Roma minority, both within and outside the Zaharna Fabrika district, highlighted the dire living conditions endured by this marginalised minority on the fringes of Bulgarian society. Consequently, deep-seated racism has evolved, depicting Roma people as thieves, burglars, and “exploiters” of the welfare state, stoking fear whenever socio-economic issues pertain to Roma communities (Trupia 2021; Maeva and Erolova 2023, among others).

None of this is new. Similar to other Roma-majority areas across Sofia and indeed the whole country, houses in the Zaharna Fabrika district were already demolished in late summer 2017 (Rexhepi 2023, 2). Bulgaria’s urban policy-making approach towards the Roma neighbourhoods is unlikely to help tackle the phenomenon of suburbanisation. Since the early 1990s, the latter has been reshaping the urban landscape in Sofia due to the increasing population in the peripheral areas of the city and urban expansion reaching smaller neighbouring towns and rural areas (Stanchev and Domaradzki 2021). Similar urban dynamics have been observed in Plovdiv – Bulgaria’s second largest city – whose urban expansion has encroached upon the former Roma village of Stolipinovo in recent decades. At present, Stolipinovo is one of Europe’s largest Roma enclaves, and one of the most ethnically segregated and underprivileged neighbourhoods in and beyond Bulgaria.[4]

The urban eviction of Roma families from the Zaharna Fabrika once again involved an exercise of power – albeit subtle or oblique – which enforced exclusion and difference (Levine-Rasky 2013). In retrospect, this exercise of power has shifted the spotlight onto a series of neighbourhoods in which spatial confinement and the steady erosion of basic rights are excluding Roma communities and shrinking their space for political participation at both a personal and collective level. As I argue elsewhere, Sofia’s intra-city dynamics and the conditions under which Roma communities are evicted and brutally displaced resemble Frantz Fanon’s crude distinction between the colonial and the colonised zone in the former Western overseas colonies (Fanon 2011/1961, 37-41).[5] By the same token, everyday life in neighbourhoods where the Roma population make up the majority is spatially shaped by the principle of reciprocal exclusivity between the Roma and other (white) city dwellers.

This description calls to mind the high level of surveillance and extensive ad hoc measures implemented in Roma neighbourhoods by force during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic in spring 2020 (Trupia 2021). Last April, the Zaharna Fabrika district was subjected to similarly heavy surveillance by police and water cannons were deployed to curb any potential unrest.[6] The Bulgarian government sought to limit the Covid-19 infection rate by declaring a state of emergency. The latter was implemented by sealing off the Roma-majority neighbourhoods and forcing residents to comply with a temporally ambiguous ad hoc quarantine. Further research showed that dozens of Roma communities were placed under systematic surveillance after the police cordoned off Roma districts in Sofia and across Bulgaria. Checkpoints were set up on the outskirts of these areas, conveying a deceptive image to the wider public of “Covid-free zones” and “diseased areas” along ethnic majority–minority lines. Drones with thermal sensors were flown above Roma neighbourhoods in Burgas to detect any outbreak of fever among residents, while an aeroplane was deployed to spray disinfectant on Roma houses in Yambol (Maeva and Erolova 2023, among others).

Examining the link between the urban eviction of Roma communities and gross human rights violations is essential, and not only in order to mainstream Roma issues (Kóczé and Bakos 2021, 212). The issue is also pertinent for discussing existing, albeit often ignored, racialised methods of control and coercion where obedience is demanded and any deviation punished.[7] In addition, the eviction of Roma families from the Zaharna Fabrika district goes beyond amplifying the impact of earmarking public land as a selective means of displacing Roma communities. It also reveals the long durée of colonial imitation of Western modernity and racial capitalism that in Bulgaria, and indeed other former socialist countries of Eastern Europe, has frequently contributed to the erasure of the cultural and political agency of Roma people under the guise of Europeanisation of former socialist citizens (Kancler 2021, 166).

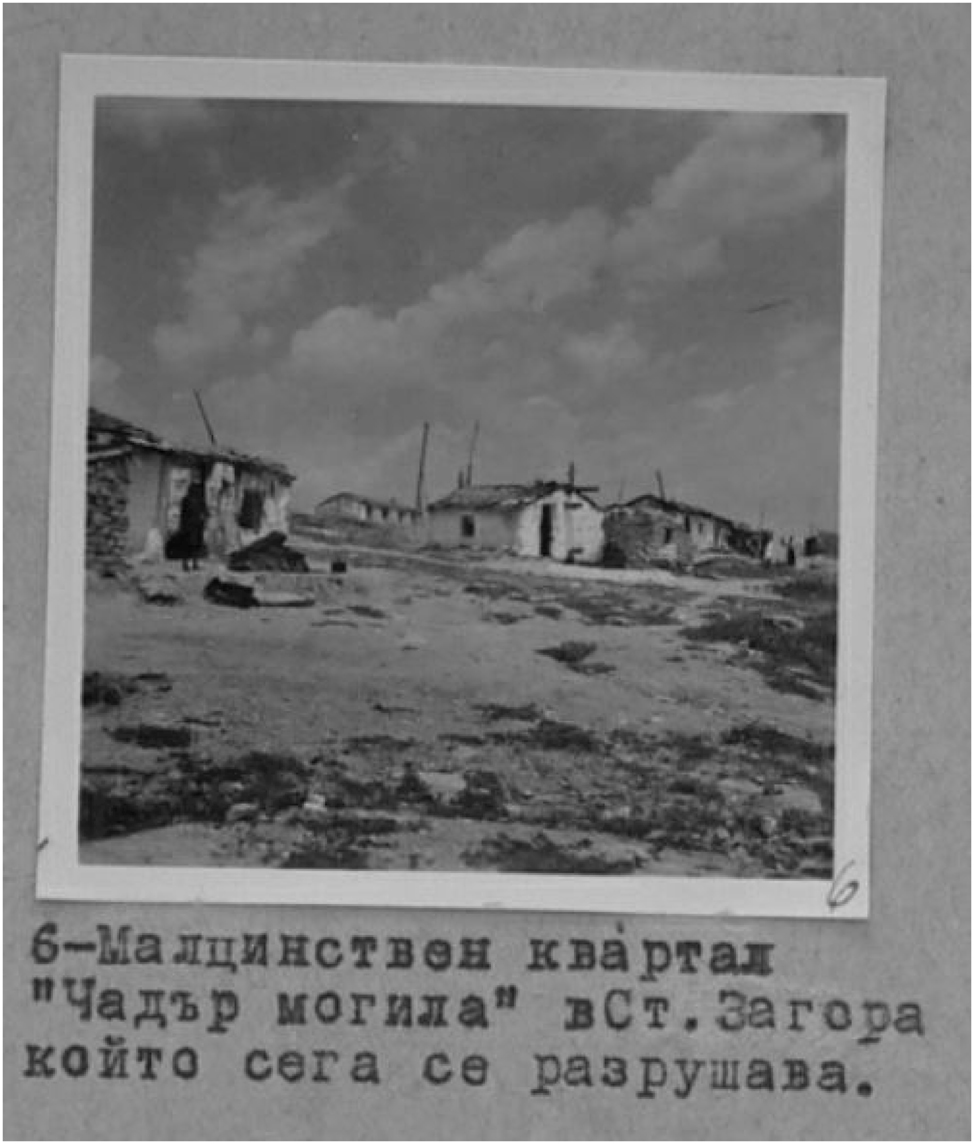

Historically, the sociopolitical issues pertaining to the Roma minority in Bulgaria have resembled other phenomena common to the former socialist states of Central and Southeastern Europe. During socialism, the Bulgarian Roma constituted a “minority within a minority”, being subjected to communist Bulgaria’s assimilation policies as members of a minority group and subaltern to the larger Turkish and Muslim minorities across the country. Their subaltern status remained unacknowledged, or barely addressed, as the protracted racialisation across different post-Ottoman spaces flew in the face of the supposed racelessness of socialist power and its ideology of classlessness. Instead, the latter was used to exploit and neutralise ethnic and religious factors and eventually exclude those citizens who manifested any symptoms of such otherness (Trupia 2024, 3). Turkish and Pomak Muslims were at times seen as redeemable “white converts” to Islam, whereas Roma, some of whom were also Muslims and Turcophones, were portrayed as complete outsiders (Rexhepi 2023, 24) (Figure 1).

Archival photograph showing the “Chadur Moghila” Roma neighbourhood in Stara Zagora, which had gone to rack and ruin during communism. It highlights the extremely poor conditions endured by Roma communities. Source: Archive State Agency, Republic of Bulgaria. “Album sas snimki za vatreshnata politika ‒ narodnostni grupi f. № 720, op. 5, a.e. 58; 58.1. Narodnostni grupi ‒ evrei, turtsi, armentsi, tsigani (1945−1982, 102 str.)”, 99. https://www.archives.government.bg/bgphoto/058.01..pdf (accessed 31 July 2025).

At the city level, spatial confinement was not uncommon as Roma settlements were hidden along railway lines and motorways, located out of sight behind concrete walls. It was in fact around the orbital railway of Sofia Central Railway Station that the Zaharna Fabrika, as well as the Poduyane district, was first used for the industrial development of the Bulgarian capital. Prior to the adoption of the resolution “on the issue of the Gypsy minority in Bulgaria” in 1958, followed in 1978 by a decree “on the further improvement of work with Bulgarian Gypsies”, this intra-city division contributed to a deepening of the systematic exclusion of the Roma, preventing them from voting, and restricting their cultural, educational, and religious initiatives. While their inclusion in the socialist system was aimed at developing a classless society, they paradoxically endured incoherent yet merciless assimilation campaigns which forced them to adopt new names and subjected them to other culturally restrictive measures (Marushiakova and Popov 2014). The extensive research I conducted on this subject in recent years has revealed that what was known as the “revival process” (Vazroditelen protses) in Bulgaria found the Muslim Roma unable to seek refuge in any other country. Those who did flee the country by travelling westwards, carried with them the heavy burden of trauma, which they subsequently passed down to post-migrant generations (Trupia 2025, 69).

Paraphrasing Achille Mbembe (2019, 62), I maintain that socialist racial thinking prevailed in the post-1989 period and throughout the process of democratisation to the extent that the latter was misunderstood as a context in which to strengthen the ethnic majority and discard the “ethnic others”, who were considered unfit for the democratic arena. Minority groups such as the Roma, who were supposed to benefit the most from the great opportunities emerging after an epoch of persecution and invisibility, ultimately ended up suffering due to the protracted postsocialist transition and the economic fatigue that accompanied the process of catching up with the Western markets (Ilisei 2017, 57).

In recent decades, some Roma activists have uncritically followed the recommendations of Western donors advocating for their cultural rights, trying to empower new spokespeople and leaders from within the community, and strengthening alternative ways of addressing the socioeconomic and political difficulties impacting the Bulgarian population – problems which without doubt have hit the Roma the hardest. Yet, the NGO sector appears to have been more concerned with implementing projects and public campaigns than solving Roma issues (Galliera 2022, 77). At the same time, Bulgaria’s official discourse often drowns out reports and research conducted by the Roma as well as media coverage, and most (white) Bulgarians never really stopped associating the entire minority with petty crime, urban pollution, illiteracy, and cultural backwardness (Karamihova 2021).

Against this backdrop, some Roma communities have recently taken a critical stance against police violence in Central and Southeastern Europe by joining the global wave of protests in the wake of the killing of George Floyd in the United States (Kola et al. 2022, 1413). Others have protested against processes of racialisation and othering in the wake of Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine (Szewczyk et al. 2025). In Bulgaria, Roma activists have claimed that a number of public policies pertaining to Roma districts are subtle interventions aimed at reducing political participation and disenfranchising the community to such an extent that it is virtually impossible for any leadership to emerge.[8]

During the 2023 election runoff in Sofia, the unexpected success of Vanya Grigorova – an independent, leftist syndicalist supported by a broader coalition of political parties – was discredited due to her strong female agency and previous involvement with Roma projects in suburban areas and urban peripheries where she ultimately received most of her electoral support. Some leftist sympathisers and younger Sofia residents were subsequently critical of Grigorova’s unclear position on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine – expressed in a nebulous rhetoric echoing that of President of the Republic of Bulgaria Rumen Radev – and the support she received, and tacitly accepted, from certain far-right organisations. When other grassroots organisations shared messages of solidarity towards the Roma, most (white) Bulgarians saw this form of activism as a manifestation of wokeism imposed by international bodies and “lobbying groups” whose “foreign propaganda” aims to put Bulgaria under external control.[9]

The discontent and distrust expressed by many Bulgarians regarding the green light the European Commission has given to the country to adopt the euro is illuminating. Under the guise of national sovereignty and economic independence, the far-right “Revival” (Vazrazhdane) party has instilled fear among the wider public and mobilised many citizens against the imposition of “eurocolonialism”.[10] Hence, it comes as no surprise that deep-seated anti-Roma rhetoric is being employed yet again, this time to reject the recommendations of Commissioner Michael O’Flaherty at the ECtHR, as well as those of the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ERCI), two institutions that advocate for Roma and LGBTQI+ rights and equality in healthcare, education, and employment.[11]

In Southeast European countries such as Bulgaria, where efforts to curb rampant emigration have failed to halt depopulation, the alarm over vacant housing and residential areas (both understood as white Bulgarian Christian spaces) becoming ghost towns barely mentions the housing issues faced by the Roma. Conversely, the so-called “Romanisation” of Bulgarian society remains a major concern in light of the increasing birth rate among Roma and Turkish families and the steep decline in the ethnically white Bulgarian population. Needless to say, the urban eviction of Roma families from the Zaharna Fabrika district reignited racial rhetoric in Bulgaria, failing to acknowledge any analysis pertaining to the different ways in which urban eviction is deeply connected with migratory outflow and political disenfranchisement (Trupia 2025, 158-76).

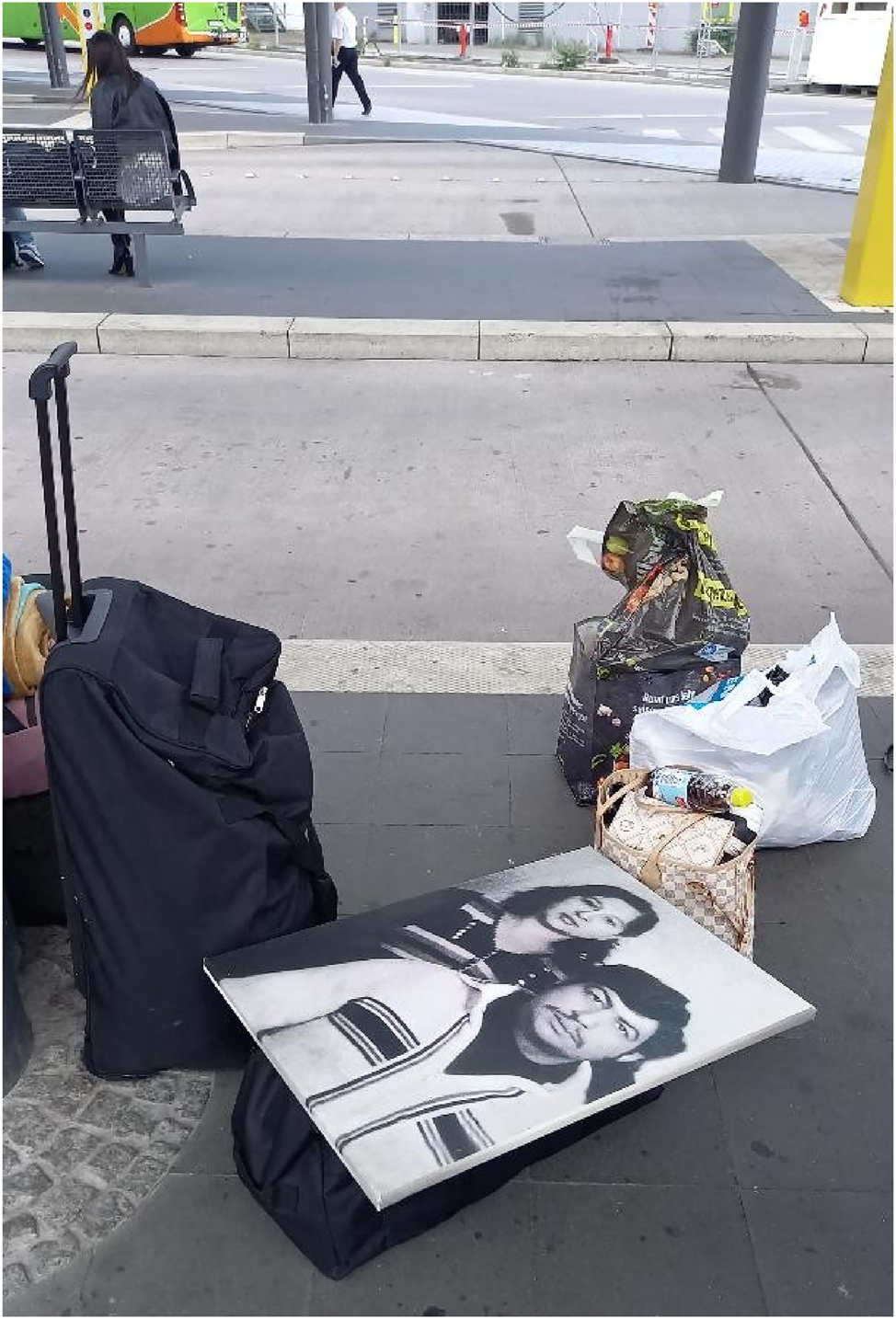

During what was dubbed the “Syrian refugee crisis” in 2015, many Roma became migrants by surreptitiously using regional humanitarian “corridors” through which thousands of refugees from war-torn Syria and the Middle East reached Europe and Germany, in particular (Figure 2). Looking at this transnational geography of migration, qualitative data from previous fieldwork in Bremen and Dortmund shows that Bulgarian Roma residents clustered around the multicultural neighbourhoods of Gröpelingen and nearby Nordstadt after arriving from the Roma enclave of Stolipinovo and other Roma areas in Kazanlak and Shumen (Trupia 2025).

A portrait of a Roma couple carried by a family arriving in Germany from Bulgaria. Source: Courtesy of the author.

Unfortunately, displacement and marginalisation do not come to an end after arrival in Germany. At all levels, Roma migrants suffer more significant economic disadvantages and inequalities that go beyond political alienation and marginalisation. They are more likely to be ostracised and face systemic punishment for their perceived inability to adapt to and incompatibility with German society. The steady erosion of rights and political agency continues as Bulgarian Roma newcomers are members of an already racialised Eastern European workforce. Of pertinence in this regard is the horrific case of Refat Süleyman, a 26-year-old migrant worker from Stolipinovo whose dead body was found kilometres away from his assigned place of work in Duisburg, in a zone designated for servicing toxic industrial waste.[12]

Even as EU passport holders, the Roma continue to face minoritisation, often perpetuated by the recurrence of the same challenging living conditions they sought to escape by migrating. As residents in non-white and working-class neighbourhoods, most Roma newcomers, and even members of the younger post-migrant generations, are confronted with nesting transnational racist attitudes, including racial profiling, arbitrary home inspections, and denial of social benefits. Just as in Bulgaria, the Roma remain low-income “allochthone” (non-native) residents in Germany, segregated yet again from “autochthonous” (native) residents. In addition, skyrocketing rents and new urban forms of touristification and financialisation deepen infra-city inequalities between the much better established Turkish diaspora and Balkan Roma families (De Cesari and Dimova 2018, among others).

I have argued elsewhere (Trupia 2025, 159) that the rhetoric of urban modernisation and innovation echoes anti-immigration discourse by far-right actors. In Germany, it seems that Henry Lefebvre’s “right to the city” (Lefebvre 1991) has been hijacked to spotlight (post-)migrant neighbourhoods – often described as “ghettos” – in order to advance a political agenda against various “undesirables”. This is similar to the scenario already envisaged by the local authorities in Sofia regarding former industrial suburbs. According to the 2003 Master Plan for the Municipality of Sofia, the Zaharna Fabrika district was designated to host the multimedia centre “Sofia and European Culture”, serving as a new spatial bridge connecting the local, cultural, and historical interconnections of the new “Belgrade–Sofia–Plovdiv–Edirne–Istanbul” route. Tellingly, Roma heritage was to be excluded and de facto erased[13] from this “spatial replanning”. In fact, the neoliberal urban mantra of turning “the city” into “innovative hubs” and functional redesignation for trade, business, and green technologies (Bourriaud 2002; Swanstrom and Plöger 2022, among others) would place the Roma and other minoritised (non-white) communities away from the natural path of history and modern development (Kolářová and Koobak 2021, 221).

As anticipated above, Bulgaria’s xenophobic and ethnonationalist discourse, which was first explicitly verbalised by groupuscules of hooligans, is increasingly being used by institutional figures. Emerging from the depths of the Bulgarian wider public, the far-right’s appeal for biopolitical population management calls for “Roma criminals” to be euthanised and Roma women to be sterilised.[14] In Germany, since the Baseballschlägerjahre – a period during the 1990s dubbed “the baseball bat years” – right-wing terrorism has continued to be deadly for the Roma and other minoritised communities. On the night of 28-29 May 1993 in Solingen, a neo-Nazi arson attack took the lives of three girls and two women from Bulgaria, all of whom belonged to an ethnic Turkish migrant family.[15] Kaloyan Velkov, also originally from Bulgaria, along with Mercedes Kierpacz and Vili-Viorel Păun, all members of the Sinti and Roma minority, were among the nine victims of the Hanau shootings committed on the outskirts of Frankfurt on 19 February 2020 by a German citizen with blatant far-right and xenophobic motives.[16] In March 2024, again in Solingen, four members of a Bulgarian family of ethnic Turkish origin were killed in yet another arson attack, which injured over a dozen others. This year, the presiding judge of the Criminal Division at the Wuppertal Regional Court suggested a far-right motive in the attack.[17]

In Bremen and Dortmund, neighbourhoods where migrants make up the majority are referred to as der Kiez, similar to the English slang term “the hood”, a word of Slavic or mixed Slavic/German origin that meant “house” or “hut”.[18] Qualitative data on the two cities indicates that Roma responses to urban forms of racism and violence do not exclude parallel actions against labour exploitation and inadequate housing. While in Bulgaria, the Zaharna Fabrika evictions sparked protest among the former residents and spurred them to raise their voices against institutional silence, inhabitants of the two German cities have shown broader and stronger support for the political participation and cultural initiatives of Roma communities seeking to claim and exercise their rights. Unlike Bulgaria, Germany’s left-leaning civil society and grassroots activism are fertile ground and provide opportunities for enacting transnational postulates of solidarity and class actions against the deprivation (or denial) of minority rights.

In the neighbourhood of Duisburg-Marxloh and the surrounding area, several thousand immigrant workers from ethnically segregated Roma groups from Bulgaria and Romania took to the streets near the gates of the ThyssenKrupp factory, calling for justice after the death of Refat Süleyman. One of a number of collectives created in this context was “Stolipinovo in Europa”, founded by a group of migrants, activists, journalists, and scientists committed to offering social counselling in the Bulgarian, Turkish, Romanian, and Roma languages for people facing unequal treatment and unfair working conditions.[19]

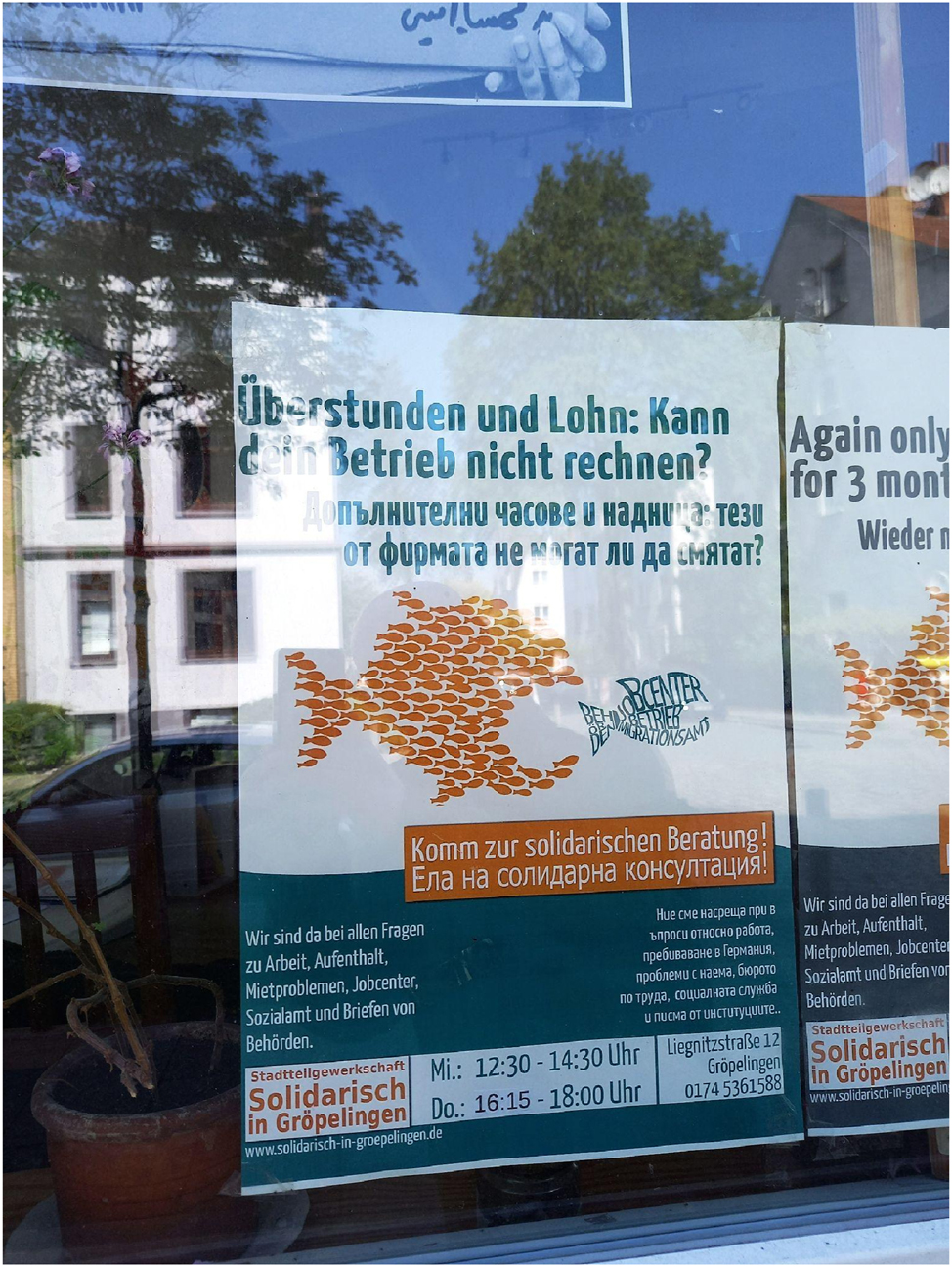

In Bremen, the struggle of some Roma residents has ended with success thanks to the Solidarisch in Gröpelingen neighbourhood union (Stadtteilgewerkschaft) composed of activists and residents from migrant communities focusing on workers’ rights, housing, and access to education. The neighbourhood bulletin, also published in Bulgarian by and for Bulgarian residents, mainly of Roma origin, informs people about strike actions and demonstrations at the district’s job centres. Roma families have been active participants in these initiatives, debunking certain political myths regarding the Bulgarian diaspora and contradicting Germany’s understanding of Roma newcomers (Figure 3).[20]

A bilingual German/Bulgarian flyer inviting Gröpelingen’s residents to participate in workers’ actions at the local job centre. As activists pointed out, the use of multiple languages is a way of forging solidarity in the neighbourhood. Source: Courtesy of the author.

In Dortmund, German–Turkish companies have a long history of labour exploitation of the Roma as they largely rely on the minority’s ability to commute between Bulgaria and Germany in times of labour shortages. The “new Germans”, as these Roma migrants are usually called after returning home from seasonal work in Germany, bring a glimpse of hope to the Bulgarian Roma community.[21] Yet most Roma are prevented from fully integrating and achieving their full potential, as today’s anti-minority discourse and nationalism leave the cultural rights of the Roma unprotected and restrict their political space for active participation within institutions both at home and in other European host countries. It comes as no surprise here that the public image of Roma workers has been sullied, putting their modest entrepreneurial activities at risk or forcing them to return home. Nor is there any doubt that an intersectional perspective along Bulgarian–German lines, such as the one presented here, warrants further research and in-depth investigation. A comparative approach might better show the cross-border reproduction of brutal racialisation and the ensuing urban eviction. Ultimately, such an approach could transcend the façade of liberal multiculturalism, enabling an exploration of the genealogy of transnational power dynamics and violence which the Roma face, both within and beyond Bulgaria.

Funding source: Narodowe Centrum Nauki

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021/43/B/HS6/00451

About the author

Francesco Trupia is an adjunct researcher at the Faculty of Humanities (Collegium Maius) at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland, and a research fellow at the CEU Democracy Institute in Budapest, Hungary. His research focuses on the intersections of democracy, memory, and political participation of minority groups in Southeastern and Eastern Europe. For the last ten years, he also has worked as a policy analyst. He is currently a member of the 9th Cycle of the Young Academics Network at the Foundation for European Progressive Studies in Brussels.

References

Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2002. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du Reel.Search in Google Scholar

De Cesari, Chiara, and Rozita Dimova. 2018. “Heritage, Gentrification, Participation: Remaking Urban Landscapes in the Name of Culture and Historic Preservation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (9): 863–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1512515 Search in Google Scholar

Fanon, Frantz. 2011/1961. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin Books.Search in Google Scholar

Galliera, Izabel. 2022. Socially Engaged Art after Socialism. Art and Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Ilisei, Irina. 2017. “Romania: a Missed Opportunity for Minorities.” In Mapping Transition in Eastern Europe: Experiences of Change after the End of Communism. Edited by Louisa Slaukova, 57–67. Berlin: German-Russian Exchange (DRA e.V.).Search in Google Scholar

Kancler, Tjaša. 2021. “Speaking against the Void: Decolonial Transfeminist Relations and Radical Potentialities.” In Postcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues. Intersections, Opacities, Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and Practice. Edited by Redi Koobak, Madina Tlostanova, and Suruchi Thapar-Björkert, 155–70. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003003199-13Search in Google Scholar

Karamihova, Margarita. 2021. “Exploring Memories of Communism in Bulgaria.” In Studying the Memory of Communism. Genealogies, Social Practices and Communication. Edited by Rigels Halili, Guido Granzinetti, and Adam F. Kola, 257–75. Toruń: Wydawnicstwo Nauko Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika.Search in Google Scholar

Kola, Adam, Agata Domachowska, Łukasz Gemziak, and Francesco Trupia. 2022. “Mnemonic Wars and Parallel Polis: the Anti-Politics of Memory in Central and Southeast Europe: Kosovar Women and Black/Roma Lives Matter.” Memory Studies 15 (6): 1406–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980221134936 Search in Google Scholar

Kolářová, Kateřina, and Redi Koobak. 2021. “Cripping Postsocialist Chronicity.” In Postcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues. Intersections, Opacities, Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and Practice. Edited by Redi Koobak, Madina Tlostanova, and Suruchi Thapar-Björkert, 216–26. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003003199-19Search in Google Scholar

Kóczé, Angéla, and Petra Bakos. 2021. “We Need to Learn About Each Other and Unlearn Patterns of Racism.” In Postcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues. Intersections, Opacities, Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and Practice. Edited by Redi Koobak, Madina Tlostanova, and Suruchi Thapar-Björkert, 209–15. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003003199-18Search in Google Scholar

Lefebvre, Henry. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Limited.Search in Google Scholar

Levine-Rasky, Cynthia. 2013. Whiteness Fractured. London, New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315547268 Search in Google Scholar

Maeva, Mila, and Yelis Erolova. 2023. “Bulgarian Roma at the Dawn of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Social Sciences 12 (4): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040208 Search in Google Scholar

Marushiakova, Elena, and Vesselin Popov. 2014. “Two Patterns of Roma Migration from Southeast Europe.” In Migration from and Towards Bulgaria 1989-2011. Edited by Tanya Dimitrova and Thede Kahl, 227–44. Berlin: Frank & Timme.Search in Google Scholar

Mbembe, Achille. 2019. Necropolitics. New York: Duke University Press.10.1215/9781478007227Search in Google Scholar

Rexhepi, Piro. 2023. White Enclosures. Racial Capitalism and Coloniality along the Balkan Route. New York: Duke University Press.10.1215/9781478023913Search in Google Scholar

Stanchev, Krassen, and Spasimir Domaradzki. 2021. “Bulgaria’s Suburbanisation. the Specifics of a Transforming Polity: a Case Study of Bulgaria.” Problemy Rozwoju Miast (72): 92–103. http://bazekon.icm.edu.pl/bazekon/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171636108 10.51733/udi.2021.72.09Search in Google Scholar

Szewczyk, Monika, Ignacy Jóźwiak, Elżbieta Mirga-Wójtowicz, and Kamila Fiałkowska. 2025. “The Claim to Have Rights, and the Right to Have Claims − Transnational Solidarity of Roma in the Face of the War in Ukraine.” Mobilities, June: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2025.2509691 Search in Google Scholar

Swanstrom, Todd, and Jörg Plöger. 2022. “What to Make of Gentrification in Older Industrial Cities? Comparing St. Louis (USA) and Dortmund (Germany).” Urban Affairs Review 58 (2): 526–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087420975203 Search in Google Scholar

Trupia, Francesco. 2021. “Debunking ‘The Great Equaliser’ Discourse: Minority Perspectives from Bulgaria and Kosovo During the First Shockwave of the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Teorija in Praksa 58, Special Issue: 616–31. https://doi.org/10.51936/tip.58.specialissue.616-631 Search in Google Scholar

Trupia, Francesco. 2024. “Otherness as a Commodity: Rethinking Islamophobia and Anti-Semitism in Central and Eastern Europe from the Time of Global Socialism.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 28 (4): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494241300836 Search in Google Scholar

Trupia, Francesco. 2025. Islamophobia in European Cities. Solidarities, Responses and Dilemmas for Young Balkan Muslims. London, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003589624Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- From Memory Politics to Mnemonic Diplomacy: Serbia’s Strategic Use of the 1999 NATO Bombing to Challenge Kosovo’s Statehood before and after Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

- The Transformation of Gender Roles and Women’s Resilience in Postwar Rural Kosovo: The Case of the Krusha Cooperative

- Negotiating Variegated Stabilities: Working Conditions of Supermarket Employees in Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- The Strength of Family Ties and Community Social Capital: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Zadar, Croatia

- Strategic Rebalancing in the Contested Global Order: The United States’ Cost–Benefit Analysis of Foreign Policy Regarding Greece and Türkiye in the Eastern Mediterranean

- Left Behind? Advocacy Lessons from the National Regions European Citizens’ Initiative on Cultural and Linguistic Diversity in the European Union

- Spotlight

- Here, There, Nowhere: Urban Eviction as State Erasure of Roma Rights and Heritage between Bulgaria and Germany

- Book Reviews

- Aida Ibričević: Decided Return Migration. Emotions, Citizenship, Home and Belonging in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Kateřina Králová: Homecoming. Holocaust Survivors and Greece, 1941–1946

- Chelsi West Ohueri: Encountering Race in Albania. An Ethnography of the Communist Afterlife

- Armend Bekaj: Former Combatants, Democracy, and Institution-Building in Transitory Societies. Kosovo and North Macedonia

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- From Memory Politics to Mnemonic Diplomacy: Serbia’s Strategic Use of the 1999 NATO Bombing to Challenge Kosovo’s Statehood before and after Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

- The Transformation of Gender Roles and Women’s Resilience in Postwar Rural Kosovo: The Case of the Krusha Cooperative

- Negotiating Variegated Stabilities: Working Conditions of Supermarket Employees in Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- The Strength of Family Ties and Community Social Capital: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Zadar, Croatia

- Strategic Rebalancing in the Contested Global Order: The United States’ Cost–Benefit Analysis of Foreign Policy Regarding Greece and Türkiye in the Eastern Mediterranean

- Left Behind? Advocacy Lessons from the National Regions European Citizens’ Initiative on Cultural and Linguistic Diversity in the European Union

- Spotlight

- Here, There, Nowhere: Urban Eviction as State Erasure of Roma Rights and Heritage between Bulgaria and Germany

- Book Reviews

- Aida Ibričević: Decided Return Migration. Emotions, Citizenship, Home and Belonging in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Kateřina Králová: Homecoming. Holocaust Survivors and Greece, 1941–1946

- Chelsi West Ohueri: Encountering Race in Albania. An Ethnography of the Communist Afterlife

- Armend Bekaj: Former Combatants, Democracy, and Institution-Building in Transitory Societies. Kosovo and North Macedonia