Left Behind? Advocacy Lessons from the National Regions European Citizens’ Initiative on Cultural and Linguistic Diversity in the European Union

-

Attila Dabis

Attila Dabis is a political scientist and civil society actor with a PhD in international relations, based in Budapest, Hungary. He has been serving as the Szekler National Council’s Foreign Affairs Commissioner since 2012. Between 2016 and 2022, he was International Coordinator of the Institute for the Protection of Minority Rights. Since 2022, he has been an academic writing consultant and AI expert at the Corvinus University of Budapest. He is also the founder and co-editor-in-chief of the academic journalMinority Protection/Kisebbségvédelem .

Abstract

This study examines the challenges minority communities face in using European Union mechanisms to contest alleged economic discrimination. It focuses on the National Regions European Citizens’ Initiative launched by stakeholders from Szeklerland, a Hungarian minority region in Romania, to urge the European Commission to address concerns over cohesion policy fund allocation. Using a theory-driven single-case design, the research combines economic data, legal analysis, and advocacy materials. County-level GDP per capita trends are triangulated with European Court of Justice jurisprudence and grassroots initiatives, framed against the Sustainable Development Goals. Findings reveal that the EU’s cohesion policy oversight is structurally ill-equipped to uncover or remedy discriminatory practices. The NUTS II statistical aggregation conceals intraregional disparities, and institutional responses to minority claims remain weak. The article focuses on the nexus between regional development and minority rights, proposing reforms to facilitate fairer distribution of funds and ensure the protection of cultural and linguistic diversity.

Introduction

For over a quarter of a century now, the human rights-based approach to sustainable development has recognised the intrinsic value of cultural diversity alongside biodiversity (Gorenflo and Romaine 2021).[1] This perspective has become embedded in global frameworks, most notably the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), where cultural and linguistic diversity is implicitly or explicitly promoted through at least three targets: Goal 16, by building effective and accountable public institutions that safeguard diversity; Goal 11, by creating resilient, inclusive, and safe societies and settlements that leave no one behind; and Goal 4, by supporting education systems that offer equitable education for all, while also safeguarding cultural and linguistic diversity. Indeed, ensuring inclusive education for all is fundamentally linked to honoring all forms of diversity, including cultural and linguistic differences: “Inclusive societies recognize and build development policies around the diversity of their members and enable everyone’s full inclusion and participation, regardless of their status.”[2] The underlying rationale is that cultural diversity enriches the global knowledge base, and its erosion weakens humanity’s collective capacity to devise sustainable solutions to complex challenges such as climate change.

More than 20 years ago, prominent European Union (EU) figures made the same observations. Head of the European Commission, Romano Prodi, identified the “diversity of cultures” as one of the cornerstones of the advantages that the peoples of Europe enjoy within a globalised world.[3] Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, in his capacity as President of the Convention on the Future of Europe, reminded his audience that the achievements of Europe, including reason, humanism, and freedom, are all based on mutual acceptance and tolerance, ensured by the EU’s cultural diversity (Giscard d’Estaing et al. 2002, 19). Even very recently, the importance of protecting cultural diversity was placed on a par with that of biodiversity by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in her 2023 State of the Union Address, in which she characterised the EU as a “Europe of the Regions with a unique blend of languages, music, art, and traditions”.[4]

Such declarations suggest that not only is safeguarding cultural and linguistic diversity a global imperative, but also a cornerstone of the EU’s self-identification. This very diversity might, however, be under threat from various public policy practices in EU member states – an issue that warrants scientific scrutiny.

Accordingly, this article contributes to the scholarly discourse on preserving cultural diversity in the EU by critically examining the practical challenges of rights advocacy in national minority regions to reach that goal. “National region” is a legal concept that entered Community law following two cases before the European Court of Justice (ECJ), which challenged the European Commission’s refusal to register the initiative.[5]

The term “national region” alludes to areas characterised by unique national, cultural, linguistic, ethnic, or religious identities that set them apart from neighboring regions – that is, a region where a minority is concentrated and thus represents the majority. The article presents an in-depth case study of the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) “Cohesion Policy for the Equality of Regions and the Sustainability of Regional Cultures” (Commission registration number: ECI(2019)000007, hereinafter “National Regions ECI”), the ECI with the longest overall procedural timeline of all citizens’ initiatives submitted to date.[6] Within the context of this ECI, the study focuses on the example of Szeklerland, a region in southeastern Romania that is home to a Hungarian national minority, whose representatives were among the initiative’s lead organisers. In this region, local actors suspected systemic economic discrimination in the allocation of EU cohesion funds, to the disadvantage of members of the Szekler national minority. According to these stakeholders, such practices not only suppress regional development but also erode cultural diversity by exacerbating inequalities and marginalisation.

This initiative, alongside related litigation, lobbying, and awareness-raising, highlights the difficulties civil society actors face in engaging EU institutions, particularly the European Commission, on claims of structural discrimination potentially affecting regional minority cultures. While the article does not evaluate the accuracy of the discrimination claims, it does underscore the persistent institutional and procedural barriers that inhibit meaningful dialogue and redress, even when the latter is supported by disaggregated data and grassroots mobilisation. Accordingly, the core research problem addressed is the protection of cultural and linguistic diversity in national minority regions within the EU’s cohesion policy framework, an aspect largely neglected in both policy evaluation and anti-discrimination assessments. Recognising that regional underdevelopment typically results from a range of interrelated factors, including political will, administrative capacity (Kaposzta and Lorinc 2024), urban–rural demographic disparities, inadequate infrastructure (Fedajev et al. 2020), and historical legacies (Cherkashyna 2022), the study refrains from making normative claims about the discrimination allegations or assessing their validity. Instead, it examines the structural conditions that constrain institutional responsiveness and the procedural barriers that obstruct meaningful dialogue and accountability regarding these claims.

Why does this matter? The potential for discriminatory practices directly undermines the foundational objective of the EU’s cohesion policy, which is to reduce economic, social, and territorial disparities in development. Such practices also impede the effective implementation of the SDGs, and by tolerating them, the European Commission risks becoming complicit in actions that violate the EU’s founding Treaties. That being said, discovering, combating, and preventing such practices can be considerably more challenging than it might initially appear. Multiple steps are required to draw the attention of the European Commission to potentially discriminatory practices that are within their jurisdiction to act upon, with numerous barriers at every step of the advocacy process.

Consequently, the core research question of this study is: How difficult is it to substantiate an allegation of economic discrimination before the European Commission in a way that compels institutional action? To answer this, the article explores two interrelated questions: 1) What are the primary obstacles in providing credible evidence of economic discrimination to the Commission?; and 2) How do these obstacles affect the EU’s capacity to ensure fair allocation of cohesion policy resources? As I will show, the European Commission lacks the institutional mechanisms required to detect potentially discriminatory state practices that can ultimately undermine the effectiveness of cohesion policy instruments and the equitable distribution of development resources.

By focusing on an underexplored aspect of cohesion policy implementation, this article provides one of the first empirical accounts of how minority regions may be structurally disadvantaged and how bottom-up advocacy often fails to trigger institutional responses. While the study does not take a definitive stance on whether, and to what extent, the relative economic underdevelopment of Szeklerland is attributable to discrimination, it does present credible sources that suggest such a link might be plausible. It argues that well-founded claims, especially those involving EU-managed financial instruments, should be sufficient to prompt action by the Commission, particularly given its legal jurisdiction in cohesion policy oversight.

Following the methodological outline provided in the next section, I present the evaluation framework employed by the European Commission to monitor the expenditure of cohesion policy resources. This is followed by an in-depth case study of the Szekler case, highlighting significant deficiencies in the current evaluation system, particularly its inability to capture the broader implications of development fund distribution. I then examine whether and to what extent the claim of economic discrimination persists over time. This is followed by an elaboration on the difficulties of detecting potentially discriminatory state practices from the point of view of the European Commission. The study concludes with an analysis of the grassroots National Regions ECI developed by stakeholders directly impacted by Romania’s potentially discriminatory funding practices and with a discussion on how the EU could implement affirmative action within its competencies to safeguard cultural and linguistic diversity. The initiative referred to in this article contains proposals to tackle the above-mentioned issue in a sustainable manner, the relevance of which is further underscored by its recent submission to the European Commission on 4 March 2025.

The analysis demonstrates that there is still considerable room for improvement in the EU’s implementation of its obligations regarding the preservation of cultural and linguistic diversity. It also highlights the need for EU institutions to exercise enhanced oversight over the allocation of development funds at the member state level, to ensure alignment with the provisions of the founding Treaties and to make progress towards achieving the SDGs. The topic is also relevant in the context of ongoing debates on the use of EU funding as a tool to safeguard its fundamental values, especially the protection of human rights, including those of minority groups, by making the allocation of such funds conditional upon member states’ compliance with these core principles (Blauberger and van Hüllen 2021).

Finally, as far as the policy implications are concerned, I hope to draw the attention of EU decision-makers, particularly those of the European Commission, to existing loopholes in the cohesion policy system that potentially violate EU law. The article then also discusses the possibility of closing said loopholes by means of a legal act of the Union, as requested by the signatories of the National Regions ECI as part of the planning process of the 2028–2034 MFF of the EU.

Methodology

While the academic literature has extensively explored the influence of culture on economic development, significantly less attention has been devoted to analysing how development programs impact regional cultures and territorial identities (Fratesi and Wishlade 2017; Butkus and Matuzevičiūtė 2016; Hofstede et al. 2010). Addressing this research gap is the central aim of this study, which is situated within the field of quantitative human rights research. Adopting an advocacy-oriented lens, the article employs a theory-driven empirical approach to explore and interpret a largely overlooked phenomenon: the allegation of economic discrimination perpetuated through EU-funded financial subsidies.

Using the case of Szeklerland as a single-case analysis, the study seeks to draw broader inferences about the systemic dynamics of such discrimination. A mixed-methods approach underpins the analysis, combining legal and economic data with evidence gathered from grassroots advocacy initiatives undertaken by the affected community. These advocacy actions do not merely serve as supplementary contextual information but are treated as vital empirical indicators that illuminate both the lived experience and reactions to the discrimination claims under examination. The primary sources of the analysis are thus a blend of advocacy documents, international documents, economic data, and scientific literature, i.e. the relevant case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU); the cohesion policy monitoring and evaluation guidelines of the European Commission; written responses of the Commission to questions of European Parliament representatives; GDP per capita data on the affected areas; materials from the UN on the human rights-based approach to sustainable development; as well as the findings of the relevant academic literature.

Put differently, this article adopts the SDGs and the foundational principles enshrined in the Treaties of the European Union as normative benchmarks, against which it evaluates empirical realities on the ground. Through the case study of Szeklerland in Romania, the article discusses a potential systemic deficiency in the allocation of EU development funding that undermines the effective implementation of cohesion policy objectives and the broader realisation of the SDGs. It argues that, in the absence of targeted monitoring mechanisms, the EU lacks the institutional capacity to detect whether member states are deploying development funds in a discriminatory manner, specifically to the disadvantage of regions primarily inhabited by national minorities.

The case of Szeklerland illustrates how the allocation of EU development funds may, in certain contexts, be employed in ways that run counter to their original purpose. Given that similar patterns of exclusion may be observed in other member states, such as Slovakia or Greece, the Szeklerland example is pivotal for exposing structural weaknesses in the EU’s cohesion policy framework and assessing their implications for the protection of the Union’s linguistic and cultural diversity.

To substantiate the analysis, the study relies on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, expressed in current market prices (EUR) and adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), as the principal economic indicator. This metric serves to highlight disparities in regional development and to quantify the economic effects of potentially discriminatory funding allocation across the relevant Romanian counties.

Given that I, the author of this study, served as the deputy representative of the National Regions ECI, I am able to draw upon first-hand experiences accumulated throughout the entire lifespan of this initiative. The foundation for the evidence compiled in this article was effectively laid in 2011, at the initiative’s conception, and further reinforced from 2013 onwards, when the representatives of the ECI, myself among them, challenged the European Commission’s refusal to register the initiative before the ECJ.[7] Now, with the ECI process approaching its conclusion, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of the advocacy-related lessons emerging from this long-term engagement.

Diversity under Threat and the EU’s Jurisdiction

According to UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, approximately 2,500 languages worldwide are classified as endangered (Moseley 2010). Over 5 % of these are found in Europe, with the vast majority categorised as either definitely or severely endangered, amounting to more than one hundred endangered languages within the EU.[8] This raises a critical question: Is the EU’s current evaluation system adequately equipped to detect member state practices that potentially diminish cultural and linguistic diversity?

Past reforms to the cohesion policy framework suggest that EU decision-makers have primarily focused on addressing macro-level concerns, such as reconciling divergent policy objectives among member states or refining evaluation methodologies. In contrast, comparatively little attention has been paid to micro-level issues, including the policy impact on regional cultures and minority identities (Bachtler and Wren 2006; Grazi 2012; Ferry and McMaster 2013). Under the current system, the European Commission exercises oversight of cohesion policy funds at multiple stages – prior to, during, and following their allocation – yet this oversight fails to capture the nuanced, localised consequences of implementation for cultural diversity.[9]

Different stages of policy evaluation serve distinct purposes. Ex ante evaluations are intended to ensure that operational programs articulate a clear intervention rationale within a strategic framework that reflects social, environmental, and economic priorities, aiming to deliver practical and sustainable solutions to development disparities. Mid-term evaluations focus on monitoring the efficient and transparent implementation of programs as approved by the relevant decision-making bodies. Ex post evaluations, in contrast, assess the broader regional and macro-economic impacts of the programs on national development, examining the extent to which their actual outcomes align with their initial objectives.

Despite this multi-tiered evaluation framework, the European Commission does not assess whether financial resources have been allocated in a discriminatory manner, particularly in ways that disadvantage national minorities or the regions they inhabit. This oversight is further complicated by the fact that the economic lag resulting from such discriminatory practices may not be readily detectable in aggregate statistical indicators. The boundaries of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) regions are aligned with pre-existing internal administrative divisions. NUTS is a geocoding framework used for referencing the administrative subdivisions of EU member states for the purpose of statistical analysis and reporting. Challenges arise when a member state’s domestic administrative structure is defined or aggregated into larger NUTS units without adequate consideration of social, historical, or cultural factors, as stipulated by Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003.[10] In such cases, tracing the financial patterns of economic discrimination against areas inhabited by national minorities becomes significantly more difficult, a concern that will now be explored in greater depth.

As the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights emphasised, the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 introduced a series of horizontal obligations that must inform all EU actions.[11] Notably, Article 9 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) requires the EU to take various considerations into account, including “the fight against social exclusion”,[12] when formulating and implementing its policies and activities. Moreover, Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) affirms that the EU is founded on core values such as respect for human rights, explicitly including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.[13]

These provisions collectively underscore the Union’s duty to ensure that its policies do not contribute, either directly or indirectly, to patterns of exclusion or discrimination. Article 3 (3), paragraphs 2-4 of the TEU, declares that the Union “shall combat social exclusion and discrimination, and shall promote social justice and protection”, “promote […] social cohesion”, and “respect its rich cultural and linguistic diversity”.[14] This latter commitment is further reinforced by Article 167 TFEU, which stipulates that the EU shall “contribute to the flowering of the cultures of the Member States, while respecting their national and regional diversity”.[15] The cultural, linguistic, and regional diversity present “between and within Member States” therefore constitutes a core value that the EU is obligated to respect and actively protect through affirmative measures, a commitment that extends “not only to the protection of national identities, but also to the protection of minority cultures”.[16]

This stance was reaffirmed in a cohesion policy context by the European Commission in its written response to European Parliament (EP) questions nr. P-000320/2022. As per this response, both member states and the Commission must ensure, among others, the integration of the principle of non-discrimination during all stages of access to and implementation of cohesion policy instruments, i.e. the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, and the Cohesion Fund. The Commission’s written response to question nr. E-001781/2022 further clarifies that it has an obligation to ensure that member states implementing EU funds respect the non-discrimination clauses of regulations governing the implementation of cohesion policy instruments (e.g. Article 16 of Regulation 1083/2006 and Article 21 of the EU Fundamental Rights Charter).[17]

This principle, when juxtaposed with the actions on the ground elaborated in the following section, substantiates the claim that if Romania’s conduct in distributing EU sources violates the acquis communautaire, this should prompt a response from the EU Commission. The nature of such a response could be manifold. The answer to question E-001781/2022 states that the Commission has different means at its disposal to ensure that member states comply with anti-discrimination standards, including “interruptions of payment deadlines, suspensions of payments and financial corrections”.[18]

A similar approach is echoed in the case law of the ECJ. In para. 129 of Judgment T-495/19 from 10 November 2021, the European General Court (EGC) called attention to the fact that it was the Commission itself that stated in its defence during the aforementioned case that it may

examine, in particular on the basis of factual information, whether and to what extent the characteristics of a national minority region may have an impact on its economic or social development in relation to the surrounding regions, and whether and to what extent the differences found between the levels of economic or social development call for action leading to the strengthening of economic, social and territorial cohesion.[19]

Furthermore, in its judgment of 24 September 2019 in Case T-391/17 (para. 56), the EGC affirmed that there is no legal barrier preventing the European Commission from proposing specific legislative measures intended to complement EU action within its areas of competence.[20] Such measures may aim to uphold the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU, including respect for the rights of persons belonging to minorities, and to safeguard the cultural and linguistic diversity of the Union, as referenced in the fourth subparagraph of Article 3(3) TEU.[21] In other words, the judgment confirms that the adoption of targeted initiatives by the Commission aimed at protecting national minorities or promoting cultural and linguistic diversity falls within the bounds of EU law and does not contravene the Treaties, provided such actions remain within the Commission’s established competences.

This is particularly true in cases of discrimination based on racial or ethnic origin, which not only undermines the rule of law but also jeopardises the attainment of the objectives enshrined in the Treaties. Such discrimination is explicitly prohibited under Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and Council Directive 2000/43/EC.[22] In light of this prohibition, Article 258 TFEU can be invoked, allowing the Commission to issue a reasoned opinion on the matter and even refer the issue to the CJEU, should the state in question fail to comply with the Commission’s opinion.[23]

The CJEU’s jurisprudence further reinforces this position through what has been termed the economic relativism approach (Davison 2009). This interpretive framework suggests that the court’s rulings should not be assessed solely in terms of legal formalism but also with regard to their practical efficacy in advancing EU objectives and ensuring coherence within the internal market. It acknowledges that economic phenomena may be evaluated through the broader lens of European integration goals, such as preventing the entrenchment of development disparities through ethnicity-based discrimination, thus seeking to strike a balance between member state sovereignty and the EU’s overarching aims.

It should be added, however, that while this might sound appealing in theory, Büyükkiliç, for example, presents EU case law-based evidence that this approach is prone to produce inconsistent enforcement of non-discrimination provisions by the ECJ. In some cases, discrimination is actively addressed; in others, it is overlooked, leading to a lack of uniformity in legal interpretations. One prominent case is Case C-2/90 Commission v Belgium [1992] ECR I-4431, whereby Wallonia in Belgium prohibited the storage, tipping, or dumping of waste originating from another member state. The Commission challenged the compatibility of this measure with Directive 84/631/EEC, which permits and regulates the transfer of hazardous waste between member states. The judgment agreed with Wallonia’s arguments that the imperative requirements of environmental protection justify the prohibition due to the large inflow of waste that poses a real danger to the environment, given the region’s limited capacity. Thus, while the ECJ acknowledged the discriminatory nature of the Belgian measures against waste originating from other member states, they ultimately found the measures justified on grounds of environmental protection as an overarching EU integration objective (Büyükkiliç 2011, 450-1).

Moreover, recent developments in EU law have introduced mechanisms for addressing threats to the rule of law, including systemic discriminatory practices. Notably, measures under Regulation 2020/2092 of 16 December 2020 (the conditionality regulation) empower the Commission to propose appropriate and proportionate measures to the Council where breaches of the rule of law in a member state pose a risk to the Union’s financial interests.[24] Arguably, if there is a well-founded threat of a member state using cohesion policy funds not for their intended purposes but to practice economic discrimination targeting national minority regions, this undermines the financial interests of the EU.

These interpretations are also reflected in the growing academic consensus on the importance of decentralisation as a means to enhance the efficiency and responsiveness of the EU’s cohesion policy framework. Focusing on the interplay between the EU, its member states, and its regions, Ridao-Cano and Bodewig (2018) argue that the policy focus of the EU’s “convergence machine” should be recalibrated towards equalising opportunities to maximise the economic potential of its regions. Capello (2018) concurs, arguing that fostering territorial identity generates a favourable social environment whereby the critical factors that hamper the successful programming, design, and implementation of cohesion policies can be overcome. More specifically, and in agreement with Healy’s (2016) views on the importance of smart specialisation approaches in centralised states where regional powers are limited, Incaltarau et al. (2020) note with respect to Romania that in such highly centralised states, increasing regional powers may maximise the use of European funds by better embedding territoriality. They add that regional disparities in development induce migration flows from the less-developed areas to financially more affluent regions, which, in turn, further widens regional development gaps over time. This phenomenon undermines the realisation of regional development policy goals as well as the SDGs.

Step 1: The Claim of Economic Discrimination

At this juncture, the experiences of Szeklerland come to the fore. Szeklerland is a historical region located in southeastern Transylvania, in the centre of Romania. Covering approximately 13,500 km2, it is predominantly inhabited by the Hungarian-speaking Szekler community (Hungarian: Székely; Romanian: Secui). Importantly, the Szeklers constitute not only a linguistic minority but also a religious one. While the majority of Szeklers does adhere to Christian denominations – primarily Roman Catholicism, Calvinism (Reformed), and Unitarian or other Protestant faiths – the majority population of Romania belongs to the Orthodox Church, underscoring an additional layer of cultural and religious differences. Past experiences indicate that both linguistic and cultural specificities[25] and religious distinctness (Andreescu 2007) have all been sources of marginalisation of Szeklers in the past. Adding to these elements of self-identification, Szeklers have also exhibited a pronounced characteristic in their political aspirations, consistently calling for enhanced self-governance through territorial autonomy of Szeklerland, drawing parallels with the model established in Italy’s South Tyrol (Dabis 2021a).

The Szekler–Hungarian population is concentrated in three counties: Hargita/Harghita (85.2 %, 257,707 people), Kovászna/Covasna (73.7 %, 150,468 people), and Maros/Mureş (38.1 %, 200,858 people).[26] These counties fall under the “Central Romanian” NUTS II development region (hereinafter CDR), along with the predominantly Romanian-inhabited counties of Alba, Sibiu, and Braşov. As a result, Szekler–Hungarians comprise less than 30 % of the population of the CDR as a whole, a demographic imbalance that was central to the arguments presented in Case T-529/13 (Izsák and Dabis v Commission) before the EGC – where I was one of the applicants – concluded on 10 May 2016. This case is particularly important for understanding the social context, given that Romania’s central government had previously planned to vest these eight NUTS II regions with administrative competencies. In what follows, I will first present the demographic and statistical data submitted in the proceedings of the aforementioned case, going on to expand the analysis by incorporating more recent data.

The intervention of the Council of Kovászna County in this judicial procedure made reference to the dramatic divergence in economic development by citing the GDP per capita of the counties of the CDR.[27] They presented data showing that, since Romania’s accession to the EU in 2007, the average per capita GDP of the counties with a Hungarian majority population (Maros, Hargita, Kovászna) has been only 80.5 % of the CDR’s average, while the corresponding figure for the counties with far fewer Hungarian inhabitants (Fehér, Brassó, Szeben) has remained well above 110 % (see Table 1).

Proportion of GDP/capita in the CDR counties, relative to the CDR’s GDP/capita average (in %).

| County | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Alba/Fehér | 108 | 103 | 102 | 99 | 107 |

| Braşov/Brassó | 122 | 124 | 118 | 122 | 126 |

| Sibiu/Szeben | 109 | 115 | 117 | 119 | 116 |

| Covasna/Kovászna | 81 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 74 |

| Harghita/Hargita | 82 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 77 |

| Mureş/Maros | 83 | 82 | 85 | 83 | 80 |

-

Source: Annex FB 3 of the Intervention of Kovászna County in Case T-529/13. https://www.nationalregions.eu/hu/hirek/2014-iv-25.

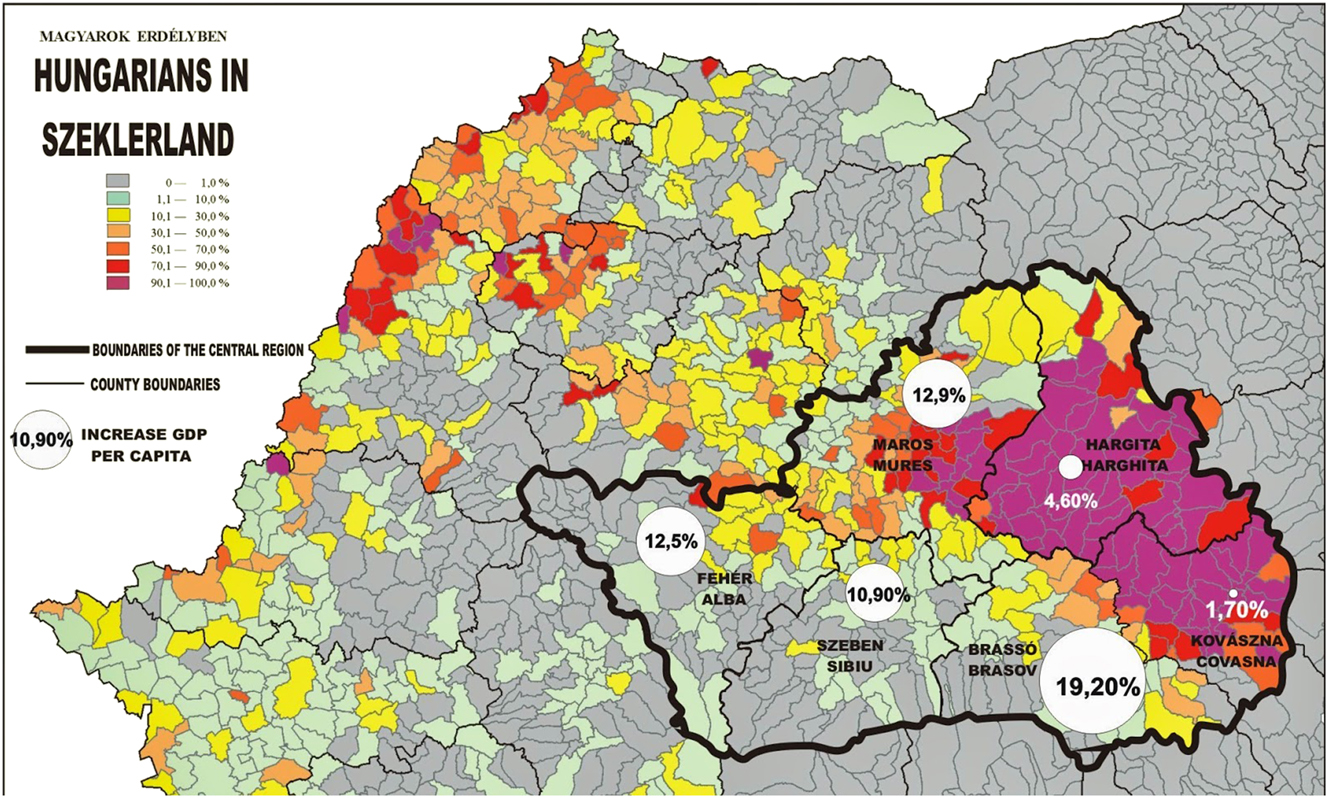

Furthermore, while the average per capita GDP in the two counties with the most substantial Hungarian majority (Harghita/Hargita and Covasna/Kovászna) grew by only 4.6 % and 1.7 % between Romania’s accession to the EU and 2013, the per capita GDP in the counties with a Romanian majority increased many times faster. Braşov/Brassó County, for example, experienced growth that was more than 11 times greater (19.2 %) than Covasna/Kovászna in the same period (see Table 2 and Figure 1).

Annual increment of GDP/capita in the counties of the central development region from (2008–2013).

| County | 2008 (EUR) | 2013 (EUR) | Increment (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alba/Fehér | 6,318 | 7,111 | 12.5 |

| Braşov/Brassó | 7,285 | 8,681 | 19.2 |

| Sibiu/Szeben | 7,225 | 8,011 | 10.9 |

| Covasna/Kovászna | 4,923 | 5,009 | 1.7 |

| Harghita/Hargita | 5,013 | 5,243 | 4.6 |

| Mureş/Maros | 5,269 | 5,953 | 12.9 |

-

Source: Annex FB 4 of the Intervention of Kovászna County in Case T-529/13.

Ethnic map of Transylvania, juxtaposed with borders of the administrative and Central Romanian NUTS II region (with bold outlines), as well as the increment of their GDP per capita income 2007-2013. Source: “A EU kohéziós politikájának kudarca a Közép-romániai fejlesztési régióban.” Erdély.ma. 19 May 2018. https://www.erdely.ma/a-eu-kohezios-politikajanak-kudarca-a-kozep-romaniai-fejlesztesi-regioban (accessed 18 September 2025).

From an analytical point of view, it should be noted that the discrimination-based arguments put forward by Kovászna County rest implicitly on the assumption that cohesion policy instruments have a positive growth effect in economically lagging regions, an assumption that is corroborated by numerous scholarly studies. This is especially the case for Objective 1 regions, i.e. regions whose per capita GDP was below 75 % of the EU average, which is true of all three Szekler NUTS II administrative units (Becker et al. 2012; Mohl and Hagen 2010). This is the case despite the fact that such convergence in development expressed in per capita GDP is not linear and is contingent on a series of other variables, such as strong institutions, low corruption, strong rule of law, effective governments, and high regulatory quality (Augusztin et al. 2025).

This line of reasoning suggests that Szeklerland would likely have experienced stronger convergence in development had it received a higher volume of cohesion funds. While it remains possible that other factors might have hindered development even in the presence of increased funding, the available evidence supports a plausible inference that the region’s developmental lag may, at least in part, be attributed to the economic consequences of allegedly discriminatory practices reflected in disproportionately low levels of funding.

That being said, the academic literature offers multiple explanations for the above-mentioned divergence in economic development, many of which attribute it to macroeconomic challenges or historical and societal factors unrelated to any form of alleged discrimination. While research showed a positive effect of European funds on the overall growth rates of new member states that joined the EU after 2000 (Marin 2022), the goal of closing regional development gaps in Romania has been hampered by weak administrative systems (Ferry and McMaster 2013), corruption, political patronage, and clientelism (Surubaru 2017a). Some scholars cite Hargita County, one of the Szekler-majority areas, as an example of such weak administrative capacity. They argue that its low absorption rate of EU funds and the limited number of development projects implemented there stem from inefficiencies in the organisation of that specific territorial administrative unit (Stan and Cojocaru 2022), which can hardly be blamed on the central government. Others point out that, when it comes to cohesion policy, the absorption rate is closely linked to the political ties between local elites and the central government, as well as the former’s ability to exert informal influence through participation in “opportunity networks” (Surubaru 2017b, 851). Additionally, and crucially for this study, other scholars contend that the persistence of development disparities stems from the central government’s reluctance to devolve decision-making authority to subnational units (Bătuşaru et al. 2015; Dyba et al. 2018; Bourdin 2019). When broader, uncontrollable factors such as global financial crises and economic cycles are also considered, the above sources underscore the difficulty of isolating or assigning relative weight to the specific determinants behind the lack of economic development convergence. This complexity makes it particularly challenging to either fully dismiss or definitively corroborate the potential impact of alleged discriminatory practices. However, this does not mean they should escape scrutiny by the European Commission.

Step 2: Does the Claim of Discrimination Persist Over Time?

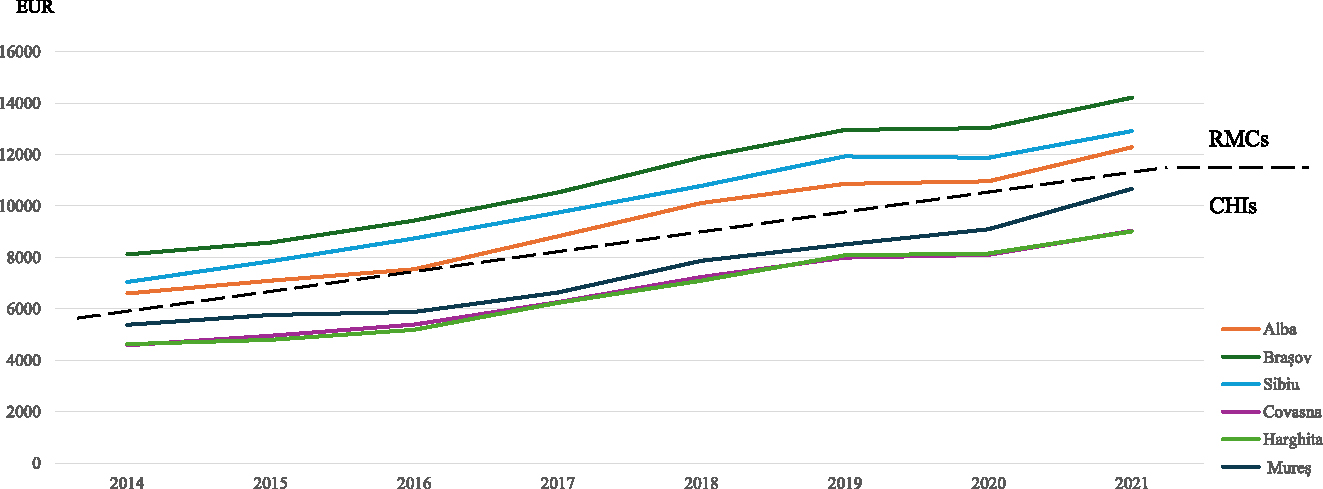

Since the data presented in the previous subchapter originates from a lawsuit initiated in 2013, more recent data must be scrutinised to gauge whether this regional development gap has continued in the years following the lawsuit. Table 3, therefore, presents the GDP per capita data of the same counties in the period from 2014 to 2021, the most recent available data when this research was completed, provided by the Romanian National Institute of Statistics (RNIS). Since the figures were initially in Romanian lei, I used the European Commission’s currency converter, InforEuro, to calculate the prices in euros at the exchange rate in force on 10 April 2025. As Table 3 shows, there has been a persistent development gap in the Central NUTS II region between the Romanian-majority counties (hereinafter RMCs) Alba, Braşov, and Sibiu, and their Szekler-majority counterparts (Covasna, Harghita) or Maros, where the Szekler form a significant minority (these will be referred to collectively as CHI or counties with Hungarian inhabitants). Table 3 and Figure 2 show that RMCs have a consistently higher GDP per capita than CHIs.

GDP/capita development in the counties of the Central NUTS II region of Romania (2014-2021) in EUR, calculated in current market prices according to NACE Rev.2 - ESA 2010.

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alba/Fehér | 6,596 | 7,092 | 7,536 | 8,815 | 10,118 | 10,865 | 10,962 | 12,284 |

| Braşov/Brassó | 8,116 | 8,578 | 9,434 | 10,523 | 11,888 | 12,960 | 13,031 | 14,214 |

| Sibiu/Szeben | 7,043 | 7,849 | 8,739 | 9,742 | 10,777 | 11,929 | 11,871 | 12,912 |

| Covasna/Kovászna | 4,580 | 4,953 | 5,386 | 6,259 | 7,233 | 7,995 | 8,098 | 9,034 |

| Harghita/Hargita | 4,627 | 4,796 | 5,183 | 6,231 | 7,092 | 8,078 | 8,148 | 9,011 |

| Mureş/Maros | 5,378 | 5,759 | 5,880 | 6,632 | 7,871 | 8,506 | 9,097 | 10,670 |

-

Source: Author’s compilation of data based on RNIS statistics available at statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed 18 September 2025).

GDP per capita development in the counties of the Central NUTS II region of Romania, 2014–2021. Calculated in current market prices in EUR, based on purchasing power parity terms. Source: Author’s own illustration based on RNIS statistics, available at //statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed 18 September 2025).

As the numbers in Table 3 show, even Maros County, the best-performing CHI unit within the Central NUTS II region, was unable to catch up with the least-well-performing RMC unit, neighbouring Alba County. The difference in GDP per capita development between the RMCs and the CHIs was an average of 47.6 % in the eight years covered.

Members of the Szekler community continue to perceive the long-lasting nature of this development gap as indirect economic discrimination, given the lack of any other reasonable justification for these disproportionate effects. An extensive survey conducted in 2019 found that both Hungarians and, to a lesser extent, even Romanians in Transylvania share the belief that there is a disparity in development. They also perceived that the different parts of Transylvania, including Szeklerland, contribute considerably more to Romania’s budget than they receive in return. Furthermore, the survey found a correlation between the ethnic makeup of a region and its economic exploitation. Specifically, in areas with a higher proportion of the Hungarian population, the state takes more resources away than it gives back (Kiss et al. 2020, 53-7), resulting in fewer opportunities for development. Here, the data cited in the Kovászna intervention are particularly relevant, given that it can be difficult to determine whether disproportionately prejudicial effects of public policy measures amount to indirect discrimination (Barelli et al. 2011, 6-8).

Step 3: Spot the Claim from Brussels

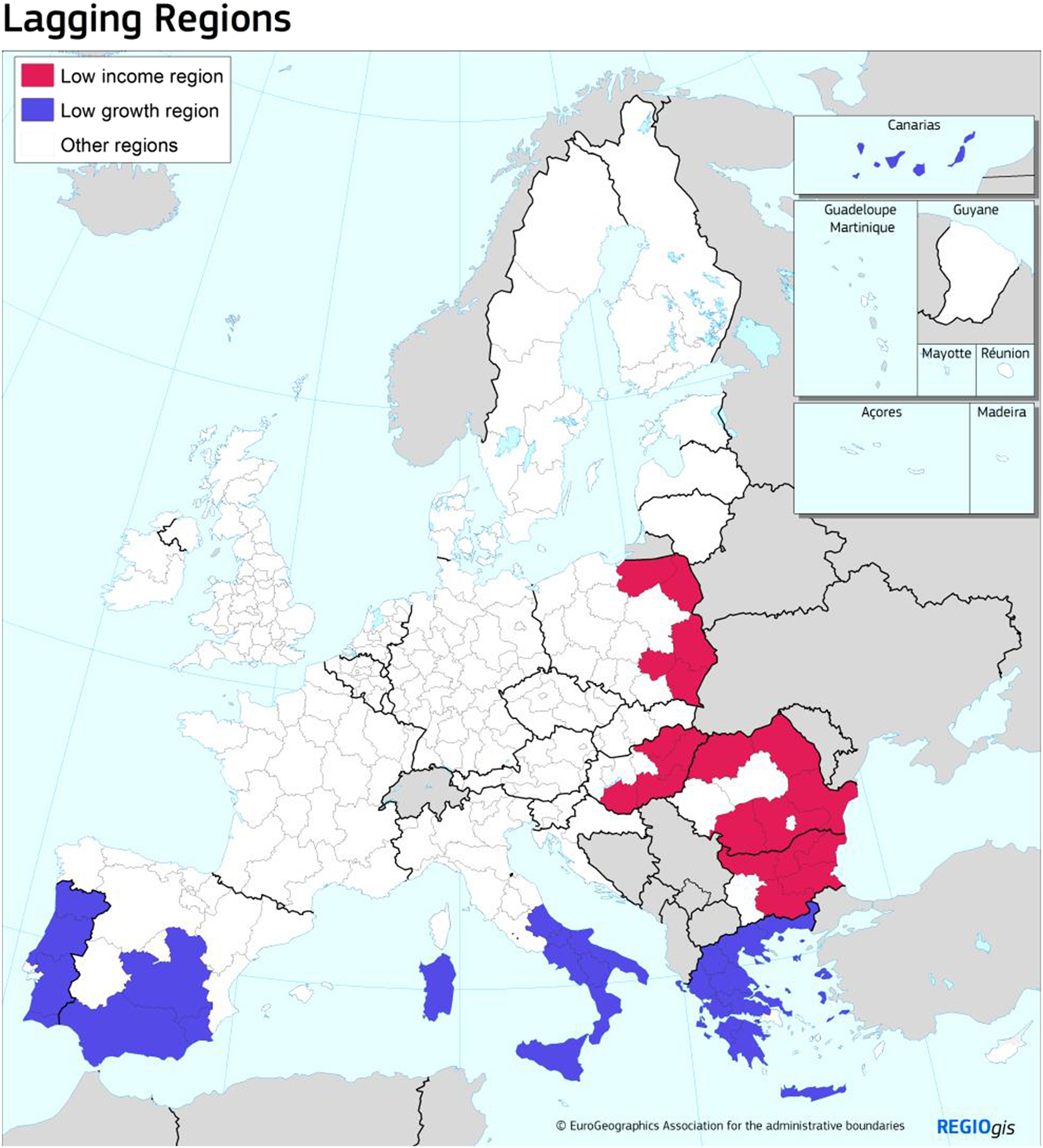

An additional dimension of the situation addressed in Case T-529/13 emerged through the expert report submitted as part of the Kovászna County intervention. This report contended that the actual economic underdevelopment of the Szekler-inhabited regions is obscured within the current NUTS II framework. Specifically, the inclusion of more developed, Romanian-majority counties within the same statistical unit artificially narrows the perceived disparity, thereby masking the economic lag of the predominantly Szekler areas (see Figure 3).

Low-income (red), low-growth (blue), and other NUTS II regions (white). Source: “Competitiveness in Low-Income and Low-Growth Regions. The Lagging Regions Report. SWD (2017) 132 Final.” European Commission Staff Working Document. 10 April 2017, 1. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/studies/lagging_regions%20report_en.pdf (accessed 19 September 2025).

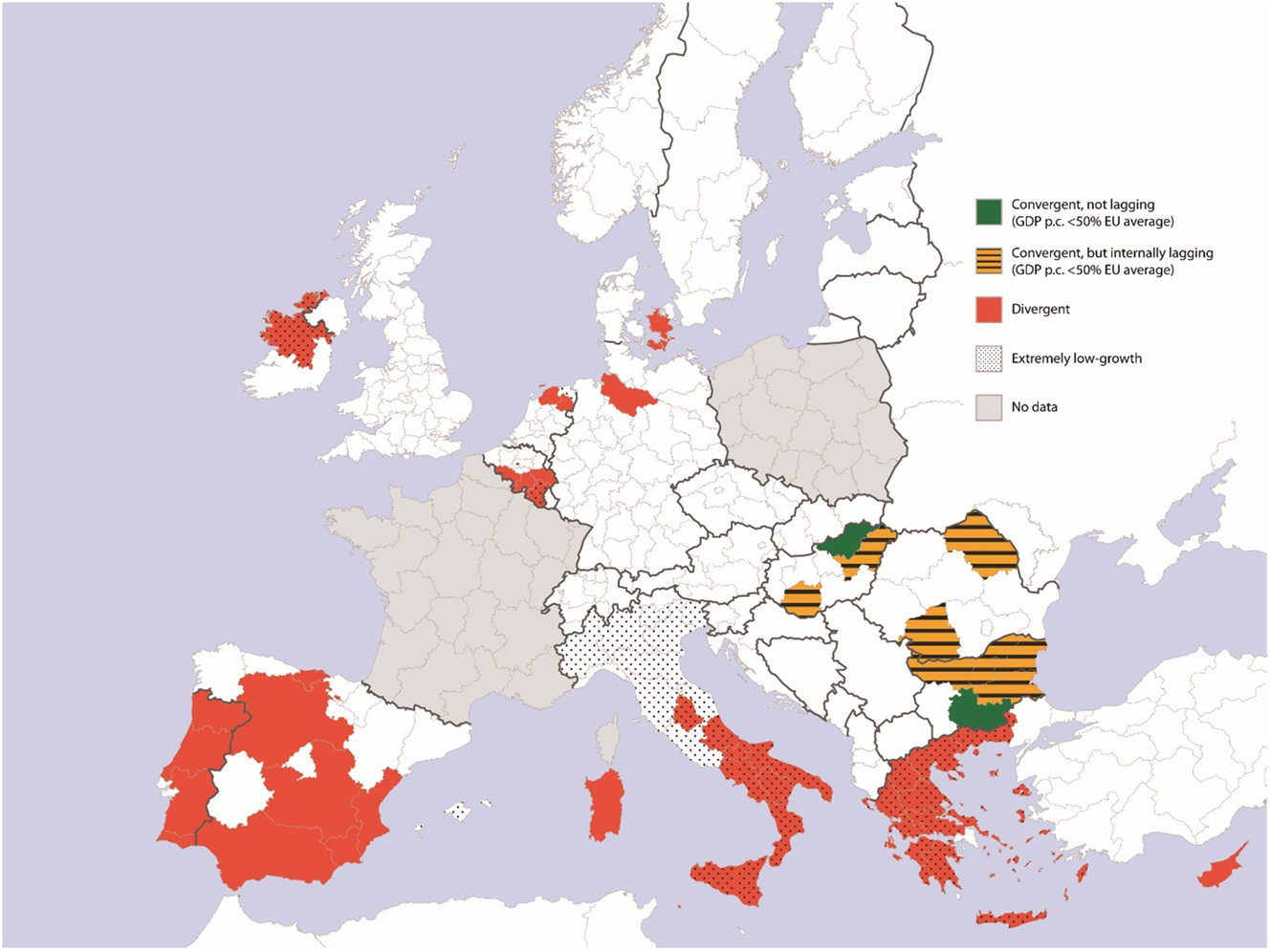

The same deceptive statistical levelling effect can be seen in other datasets. The OECD 2022 Economic Survey of Romania shows that while regional development has been extremely uneven, and regional disparities, in terms of GDP per capita, are much larger than in the OECD on average, the Central Development Region appears to be the second-best performing region in terms of “population percentage at risk of poverty”. The same indicators show the aforementioned CHIs to be in a much worse position, if measured on a county (NUTS III) basis.[28] Moreover, an expert study commissioned by the European Parliament’s Committee on Regional Development observed that “low-income regions in Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria are strongly converging to the average EU income and should therefore not be considered as lagging”.[29] As a result, the report does not classify the Central NUTS II region in Romania as a lagging region, defined as having a persistently below-average GDP per capita, nor as a diverging region, which refers to areas that remain economically underdeveloped relative to the EU average and show limited convergence (see Figure 4).

Lagging regions in the EU, based on GDP (2019). Source: Pilati and Hunter 2020, 23.

Furthermore, it seems that the EU itself has different priorities when it comes to reporting discrimination. A Eurobarometer survey from 2019, for example, measured discrimination from many angles (e.g. discrimination in access to employment opportunities) and with a focus on Roma, women, the elderly, and LGBTI people. Yet, economic discrimination in terms of EU development funds directed against autochthonous national minorities flew largely under the radar in their analysis.[30]

A similar pattern emerges from Romanian source materials. When examining regional GDP per capita data, the CDR ranks as the third-best-performing NUTS II region in the country, surpassed only by the capital region (Bucharest–Ilfov) and the westernmost region (Vest) (Surd, Kassai, and Giurgiu 2011, 23; Oțil, Miculescu, and Cismaş 2015, 42).

This phenomenon is also relevant from the point of view of the SDGs, as scholars have identified the lack of proper, territorially disaggregated data as a significant barrier to the effective implementation of the SDGs. Without adequate data, policies risk being overly generic, missing the needs of specific regions, and reinforcing existing inequalities through poorly targeted interventions, thereby hindering progress towards achieving the SDGs (Pop and Stamos 2025).

Even though Romania’s national development plan at the moment of the country’s accession to the EU contained[31] – and its current plan still does contain –[32] the strategic goal of stopping and preferably reversing the growing trend of regional development disparities, the expert report submitted alongside Kovászna County’s intervention further contended that the current configuration of the CDR was inefficient in achieving the objectives of cohesion policy. This inefficiency was attributed to the significant disparities between the RMCs and the CHIs, as well as to the persistent failure of successive Romanian governments to acknowledge and address the distinct developmental needs arising from these differences. As Crucitti et al. (2022) argue, Romania’s cohesion policy strategy for the 2021–2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) is conceptually flawed. The strategy prioritises investment in regions that are already more developed, operating under the assumption that the resulting growth will eventually diffuse to less developed areas. However, the authors note that such top-down development plans tend to generate minimal spillover effects and thus fail to promote meaningful convergence or reduce internal regional disparities.

Compounding the above, the current boundaries of the CDR are also at odds with the provisions of the NUTS regulation. By bringing administrative units together within a NUTS II region with no regard for relevant social, historical, and cultural factors, this territorial delineation conceals intraregional inequalities and development patterns that run counter to the overarching objectives of both EU cohesion policy and Romania’s national development plans.

From the perspective of the SDGs, the establishment of development regions based on cultural, historical, and linguistic specificities can be seen as a means to promote inclusive governance structures grounded in the principle of subsidiarity. Such an approach enhances the capacity of public policy to ensure that no one is left behind, a core commitment of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In contexts such as Szeklerland, where multiple identity dimensions (linguistic, cultural, and religious) intersect and may serve as grounds for exclusion or marginalisation, it is especially critical for states to “recognise and respond to multiple and intersecting deprivations and sources of discrimination that are compounded by one another and make it harder to escape poverty, live with dignity and enjoy human rights”.[33]

At this point, it is important to note that discrimination against national minorities is neither a phenomenon that is foreign to the European Commission nor unique to the case of Szeklerland. Since 2014, the Commission has launched infringement proceedings against several member states, including Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, for failing to implement the Racial Equality Directive, particularly concerning the segregation of Roma children in schools. The recent case Commission v Slovak Republic (C-799/23) underscores that institutional responses to ethnic discrimination are both possible and precedent based in the EU.[34] Similar claims have been raised elsewhere, including in case T-529/13, where the Hungarian-majority town of Debrad, acting as an intervenor plaintiff, alleged systematic underfunding during the 2007–2013 programming period in Slovakia, showing a negative correlation between the proportion of ethnic Hungarians and EU fund allocation within the Environmental, the Rural, and the Regional Development Operational Programmes (Int. VII-14, dated 25 August 2018, No. 634824). Likewise, in Greece’s Western Thrace region, persistent underdevelopment has been linked to discriminatory policies against the local Turkish-Muslim minority,[35] with studies indicating unequal distribution of EU funds and structural exclusion among the underlying causes. It is important to note that the Western Thrace region is not only geographically peripheral but also home to approximately 100,000 Turkish-Muslim minority citizens, a community that constitutes both an ethnic and religious minority. The vulnerability of this area and its inhabitants is further exacerbated by structural disadvantages, with over 80 % of the population residing in rural areas and nearly half depending on tobacco farming for their livelihood. As a result, Western Thrace remains the least developed region in Greece and one of the most economically marginalised areas in the entire European Union, particularly in the context of the EU’s post-2004 enlargement.[36] These examples collectively illustrate that the issues raised in the Szeklerland case are neither unique nor unprecedented, but part of a wider challenge of ethnic inequality that is known to the decision-makers of the European Commission.

Together, the deprivations documented in Kovászna County’s court application and the findings outlined in the above sections paint a troubling picture: the European Union appears inadequately equipped to detect instances in which a member state might be allocating cohesion policy resources in a discriminatory manner. This institutional limitation constrains the EU’s capacity to respond effectively to such occurrences and hampers the potential for learning during the funding cycle. As a result, the system struggles to implement safeguarding mechanisms that could prevent the recurrence of such discriminatory practices. Against this backdrop, a question that arises here is what the broader policy implications might be. This is something that will be discussed in more detail in the upcoming two sections.

Step 4: Affirmative Action as a Way to Safeguard Socioeconomic Cohesion in the EU

In the third section above, I explored the EU’s key responsibilities in combating discrimination, addressing social exclusion, and safeguarding cultural and linguistic diversity. To grasp the practical implications of these responsibilities, it is essential to analyse the goals of the National Regions European Citizens Initiative that prompted a lawsuit on this topic to be brought before the CJEU a decade ago. This legal case was a salient illustration of the developmental challenges that national regions of the EU might face.

Case T-529/13 and its appeal procedure (C-420/16 P) concerned the registration of the National Regions ECI. The initiative called for special attention to be given within the EU’s cohesion policy to national regions, including those that may lack administrative competencies, such as Szeklerland or Alsace, in France. According to the ECI’s organisers, in the context of such national regions, the prevention of economic underdevelopment, the promotion of sustainable development, and the maintenance of economic, social, and territorial cohesion must be pursued in a manner that preserves their distinctive cultural features at the same time. This approach, they argued, is essential to achieving sustainable and harmonious development within the EU while also safeguarding its cultural and linguistic diversity.

In line with this vision, the initiators proposed that such “special attention” could take the form of a dedicated funding mechanism within the EU’s cohesion policy, one that would be directly and exclusively accessible to national regions. At a minimum, they suggested the introduction of safeguards to ensure that EU financial instruments are not used to support economic discrimination against these regions. To substantiate their proposal, the organisers submitted a supporting document detailing the subject matter, objectives, and broader context of the ECI.[37] This material explicitly engages with the third paragraph of Article 174 TFEU, which stipulates that

Among the regions concerned, particular attention shall be paid to rural areas, areas affected by industrial transition, and regions which suffer from severe and permanent natural or demographic handicaps such as the northernmost regions with very low population density and island, cross-border and mountain regions.

This list is illustrative and not exhaustive, allowing for the inclusion of additional categories. In the experience of the ECI organisers, the unique ethnic, cultural, and linguistic traits of national minority regions can, in practice, become demographic handicaps, making it more challenging for these regions to establish the necessary conditions for economic, social, and territorial cohesion. A separate legal act of the Union could thus broaden the scope of Article 174 and ensure that the EU gives special attention to national regions, an approach whose legality was confirmed by the European Commission in its final response to this ECI:

[…] the Commission considers the proposal to expand the list of least favoured regions in Article 174 TFEU to include new categories such as national regions, as well as the proposal to ensure equal access to Union funding and ensuring that Union funds are not used in ways that would alter the ethnic composition, regional identity, or cultural heritage of national regions to fall under the scope of the ECI as registered by the Commission.[38]

This novel funding mechanism could create proper financial incentives for states to appreciate, protect, and maintain their unique cultural diversity. Simultaneously, it could empower local communities to independently devise and execute their own innovative regional development strategies. Such a financial framework could provide the leverage for local communities to tackle their respective development issues and prevent the eventual demographic decline of their regions and the outflow of their population, which in itself erodes and endangers traditional minority cultures in the EU.

To ensure the above outcome, the organisers explained during the ECI’s public hearing in the European Parliament’s Regional Development Committee (REGI) that the proposed legal act should clearly enumerate the national regions of the EU, ensuring that all member states and EU institutions have a shared understanding of the beneficiaries involved.[39] Should direct funding be introduced, this mechanism would empower representatives of local communities to determine how funds are allocated, effectively removing discriminatory political practices by the territorial state from the decision-making process. Revising EU development policy in the above-indicated direction is also possible in the view of the EGC, as stipulated in para. 129 of case T-495/19. The referenced written answers from the European Commission, complemented with the provisions of the founding Treaties, substantiate the claim that the EU has a proactive obligation to prevent and combat all forms of discrimination, also in terms of cohesion policy funds, and to safeguard the cultural and linguistic diversity of the Union. Policy outcomes and actual practice on the ground, however, have also been subject to political considerations reflecting the Commission’s growing involvement in shaping cohesion policy directions (Batory 2021, 190-2; Wille 2007).

Conclusions and Implications

The European Commission is bound by a dual responsibility to ensure the preservation of cultural diversity within the European Union: a legal obligation derived from the EU’s founding Treaties and a political obligation that arises from the commitment made to the UN to integrate the SDG objectives into EU policies. Yet, the collected evidence reveals a systemic deficiency in the monitoring and evaluation mechanisms pertaining to the impact that the national-level allocation of EU development funds may have on regional cultures and territorial identities. When such allocation practices are discriminatory, they impede the effective implementation of core policy objectives, such as the reduction of disparities between regions, and undermine the fulfilment of the SDGs, particularly those aimed at fostering inclusive societies that leave no one behind. In the absence of a dedicated evaluation framework addressing these concerns, there is a tangible risk that member states may divert EU resources towards objectives that contravene the Union’s aims and, in doing so, violate its foundational values. As a result of this loophole, EU policymakers may not be able to accurately identify the populations left behind and understand the underlying factors contributing to their exclusion, potentially resulting in ineffective interventions that exacerbate disparities and hinder progress towards the achievement of the SDGs, as well as cohesion policy objectives.

The case of Szeklerland highlights a serious risk, namely that EU funds can be used as instruments of indirect discrimination, escaping detection by EU institutions. Given that a range of factors, such as weak administrative structures, political patronage, corruption, and external economic shocks, may contribute to regional disparities in development levels, this article does not seek to determine the specific weight or causal role of each in explaining the relative economic underperformance of Szeklerland, as indicated by GDP per capita data. These factors are often mutually interconnected, including claims of discrimination, which makes it difficult to isolate their individual impact. Nevertheless, the sources cited in relation to Szeklerland are particularly noteworthy due to their grassroots origin, reflecting the lived experiences and perspectives of local actors. As outlined in the preceding section, these inputs originate from local representatives of the affected community – myself included – and reflect a bottom-up account of the discrimination, social exclusion, and demographic disadvantages experienced by inhabitants of a national region, on the grounds that the ethnic, cultural, and linguistic characteristics of the area they traditionally inhabit are different from those of the surrounding regions.

The EU, bound by its founding Treaties, is obliged to refrain from becoming complicit in any form of discrimination, including indirect economic discrimination against regions inhabited by national minorities. Permitting such practices would not only undermine its foundational values but also jeopardise its overarching objective of achieving balanced and harmonious development across its territory. Attaining this objective requires a clear identification of the underlying sources of developmental divergence, a task that is often as complex as formulating effective solutions to address them.

This challenge is further exacerbated when evaluation procedures fail to account for critical factors contributing to economic underperformance, such as the potentially discriminatory allocation of funding resources. At present, the European Commission’s monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are insufficiently equipped to detect, let alone prevent, such policy shortcomings. In the absence of effective detection capabilities, it becomes exceedingly difficult for affected communities to bring their grievances to the attention of EU decision-makers through rights-based advocacy, let alone to prompt serious consideration of discrimination claims or act as a catalyst for concrete measures aimed at preventing such occurrences in the future.

While the primary responsibility for preventing discriminatory practices against regions inhabited by national minority communities lies with the member states, the fact that economic, social, and territorial cohesion constitutes a shared competence between the EU and its members justifies the expectation that the European Commission should, at a minimum, establish the capacity to detect discriminatory patterns in the allocation of EU development funds. This position is further supported by the EGC’s judgment in Case T-495/19.

Development agencies, financial institutions, and other actors engaged in international cooperation and the allocation of development funds face a dual responsibility with respect to national minorities. First, they must ensure that the legitimate interests of minority communities are not adversely affected by the measures implemented within the framework of such cooperation. Second, they are obliged to guarantee that persons belonging to minorities can benefit from development efforts on an equal footing with members of majority populations.[40]

This dual responsibility is underscored by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which cautions that “[d]evelopment is a powerful tool, but it can also be a tool of the powerful unless human rights for all, without discrimination, is part of its design.”[41] In line with this perspective, Henrard added that the vision of social inclusion is mostly about ensuring that “minorities’ integration in the wider society does not go hand in hand with forced assimilation” (Henrard 2015, 157-8). Shahabuddin noted concurrently that “[a]n alternative paradigm is needed beyond the conventional ‘vulnerability framework’, which considers minorities agency-less entities in constant need of external protection, to empower minorities to ensure their own protection” (Shahabuddin 2023, 977).

The National Regions ECI was submitted to the Commission on 4 March 2025. On 25 March 2025, Raffaele Fitto, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission for Cohesion and Reforms, received the representatives of the ECI as the first step in the Commission’s preparation of the reply to their initiative.[42] This was followed by a public hearing in the European Parliament’s Committee on Regional Development (REGI Committee) on 25 June 2025, in joint session with the Cultural and the Petition Committee as well as the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE Committee). On 10 July, a plenary debate in Strasbourg followed.[43] Pursuant to Article 15 of Regulation (EU) 2019/788, the Commission communicated its legal and political conclusions on the initiative on 3 September 2025.[44]

While the most favourable outcome envisaged by the organisers was the establishment of a dedicated funding mechanism exclusively accessible to member states with national regions, the final result fell significantly short of this. Despite over a decade of advocacy efforts – including strategic litigation, systematic data collection, lobbying of decision-makers, and successful mobilisation of citizens’ support – the European Commission refused to adopt a new legal act or amend an existing one on the basis of this ECI. In its communication, the Commission found that a legal act on national regions requested by the ECI was neither necessary nor an appropriate response to the initiative, arguing that a) there was no clear evidence that national regions were systematically disadvantaged; and b) the legislative framework currently applicable to cohesion policy contained safeguards to ensure compliance with the Charter of Fundamental Rights and prevent discriminatory practice, which were not in place when the request for registration of the ECI was submitted on 18 June 2013.[45]

While these new methods have indeed been introduced under Regulation (EU) 2021/1060, including, for example, horizontal enabling conditions, that is requirements that member states must fulfil before they can effectively access EU funds,[46] the framework these methods establish can hardly be characterised as an effective remedy to the discrimination issue discussed here. Their design is too convoluted; their procedures too protracted; and their character too overtly politicised. Under this regulation, it is up to the member states to assess whether the enabling conditions linked to a specific objective are fulfilled or not, including the implementation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights. The Commission’s role here, pursuant to Article 15 of the same regulation, is to assess whether it agrees with the member state regarding the fulfilment of the enabling condition. If not, then the reimbursement of costs linked to objectives where the Commission deems the corresponding enabling conditions not to have been met can be withheld until compliance is proven by the member state. In late 2022, the European Commission invoked the conditionality regulation for the first time against Hungary, suspending 6.3 billion euros due to concerns about the rule of law and corruption.[47] To date, no other member state has faced a similar Council decision. Apart from this, Article 69 (7) of the same regulation stipulates that it is the jurisdiction of the member states to ensure the effective examination of complaints concerning the funds. This arrangement can hardly be regarded as a standard institutional mechanism for addressing cases of discrimination, nor is it suited to preventing such issues, since it channels potential grievances back to the very territorial state whose practices may be under scrutiny.

In practical terms, the Commission’s response to the ECI amounted to a reaffirmation of existing instruments rather than a commitment to policy reform, implying that the initiative’s concerns had been overtaken by subsequent regulatory developments. In the broader context of ongoing discussions surrounding the cohesion policy framework for the 2028–2034 MFF, the European Commission made no attempt to connect the National Regions ECI to the broader budgetary debates. During the EP public hearing, as well as in advocacy meetings with relevant office-holders, the ECI organisers emphasised that the underlying spirit of their initiative reflects a clear preference for a more decentralised cohesion policy. This preference is directly contrasted with the centralised, umbrella-funded model proposed in the Commission’s 2025 Midterm Report on Cohesion Policy. Rather than empowering national regions, the proposed policy direction threatens to further erode their visibility and influence within the EU’s institutional framework.

Moreover, the trajectory of current policy discussions suggests a possible consolidation of cohesion policy into a broader funding architecture, potentially in combination with the Common Agricultural Policy. Such an approach risks reducing the visibility of cohesion policy as a distinct instrument and may further marginalise specific territorial concerns. For the inhabitants of national regions, this development raises the prospect that their cultural and linguistic particularities will receive even less direct attention in future financial frameworks. In fact, elements of this “minimising approach” were already present in the Commission’s response to the ECI, where it extended its reasoning by grouping national minority regions together with other, unrelated categories of marginalised populations, such as persons with disabilities or chronic illnesses, homeless individuals, and the elderly.[48] In this sense, the Commission’s response to the initiative, when read alongside its preferences for the upcoming MFF, conveys continuity with existing practices rather than a move towards enhanced recognition of the specific development needs of national minority regions.

Finally, the outcome underscores a structural feature of the ECI mechanism itself. Since the regulation does not legally compel the Commission to initiate legislative proposals even when initiatives are successful, institutional responses remain inherently discretionary. In this case, the Commission’s decision illustrates that the principal constraint on reform was not juridical, but political. The National Regions ECI thereby exemplifies both the capacity of the instrument to channel concerns into the EU policy agenda and its limitations in translating such mobilisation into substantive policy change.

About the author

Attila Dabis is a political scientist and civil society actor with a PhD in international relations, based in Budapest, Hungary. He has been serving as the Szekler National Council’s Foreign Affairs Commissioner since 2012. Between 2016 and 2022, he was International Coordinator of the Institute for the Protection of Minority Rights. Since 2022, he has been an academic writing consultant and AI expert at the Corvinus University of Budapest. He is also the founder and co-editor-in-chief of the academic journal Minority Protection/Kisebbségvédelem.

References

Andreescu, Liviu. 2007. “The Construction of Orthodox Churches in Post-Communist Romania.” Europe-Asia Studies 59 (3): 451-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130701239906 Search in Google Scholar

Augusztin, Anna, Áron Iker, Anna Monisso, and Béla Szörfi. 2025. The Growth Effect of EU Funds – the Role of Institutional Quality. Working Paper No. 2025/3014. Frankfurt/M.: European Central Bank. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5119947 Search in Google Scholar

Bachtler, John, and Colin Wren. 2006. “Evaluation of European Union Cohesion Policy: Research Questions and Policy Challenges.” Regional Studies 40 (2): 143-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600600454 Search in Google Scholar

Barelli, Mauro, Gulara Guliyeva, Stefania Errico, and Gaetano Pentassuglia. 2011. Minority Groups and Litigation: A Review of Developments in International and Regional Jurisprudence. Working Paper. London: Minority Rights Group International. https://minorityrights.org/app/uploads/2024/01/mrg-minority-groups-and-litigation-guide.pdf Search in Google Scholar

Batory, Agnes. 2021. “A Free Lunch from the EU? Public Perceptions of Corruption in Cohesion Policy Expenditure in Post-Communist EU Member States.” Journal of European Integration 43 (6): 651-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1800681 Search in Google Scholar

Bătuşaru, Cristina Maria, Oțetea Alexandra, Dobre Cristian Alexandru, and Ungureanu Mihai Aristotel. 2015. “The Importance of Regionalization in Improving the Process of Absorbing European Funds in Romania.” Annals of the Constantin Brâncuşi University of Târgu Jiu, Economy Series 2015 (5). https://www.utgjiu.ro/revista/ec/pdf/2015-05/19_Batusaru,%20Otelea.pdf Search in Google Scholar

Becker, Sascha O., Peter H. Egger, and Maximilian von Ehrlich. 2012. “Too Much of a Good Thing? On the Growth Effects of the EU’s Regional Policy.” European Economic Review 56 (4): 648-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.03.001 Search in Google Scholar

Blauberger, Michael, and Vera van Hüllen. 2021. “Conditionality of EU Funds: An Instrument to Enforce EU Fundamental Values?” Journal of European Integration 43 (1): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708337 Search in Google Scholar

Bourdin, Sebastien. 2019. “Does the Cohesion Policy Have the Same Influence on Growth Everywhere? A Geographically Weighted Regression Approach in Central and Eastern Europe.” Economic Geography 95 (3): 256-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1526074 Search in Google Scholar

Butkus, Mindaugas, and Kristina Matuzevičiūtė. 2016. “Evaluation of EU Cohesion Policy Impact on Regional Convergence: Do Culture Differences Matter?” Economics and Culture 13 (1): 41-52. https://doi.org/10.1515/jec-2016-0005 Search in Google Scholar

Büyükkiliç, Öğr Gör Gül. 2011. “Discrimination in the European Union: A Problem Aimed to Be Resolved or Just an Instrument to Serve the Economic Targets?” Marmara Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Hukuk Araştırmaları Dergisi 17: 1-2. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1256 Search in Google Scholar

Capello, Roberta. 2018. “Cohesion Policies and the Creation of a European Identity: The Role of Territorial Identity.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 489-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12611 Search in Google Scholar

Cherkashyna, Tetiana. 2022. “Taxonomic Analysis of Income Inequality in the EU Countries.” Economics of Development 21 (4): 8-18. https://doi.org/10.57111/econ.21(4).2022.8-18 Search in Google Scholar

Crucitti, Francesca, Nicholas-Joseph Lazarou, Philippe Monfort, and Simone Salotti. 2022. A Cohesion Policy Analysis for Romania towards the 2021-2027 Programming Period. Working Papers on Territorial Modelling and Analysis, No. 06/2022. Luxembourg: The Joint Research Centre: EU Science Hub. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC129049 Search in Google Scholar

Dabis, Attila, Vivien Benda, and Tamás Zoltán Wágner. 2019. “A közvetlen demokrácia európai útjai, különös tekintettel az európai polgári kezdeményezésre.” Kisebbségvédelem - Minority Protection (1): 69-94.Search in Google Scholar

Dabis, Attila. 2021a. Misbeliefs about Autonomy. The Constitutionality of the Autonomy of Szeklerland. Berlin: Peter Lang. https://www.peterlang.com/document/1140501 10.3726/b18504Search in Google Scholar

Dabis, Attila. 2021b. “Sustainability of Cultural Diversity and the Failure of Cohesion Policy in the EU: The Case of Szeklerland.” In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions: Results of SSPCR 2019. Edited by Adriano Bisello, Daniele Vettorato, Håvard Haarstad, and Judith Borsboom-van Beurden, 355-69. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57332-4_25 Search in Google Scholar

Davison, Leigh M. 2009. “EU Competition Policy: Article 82 EC and the Notion of Substantial Part of the Common Market.” Intereconomics 44 (4): 238-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-009-0301-3 Search in Google Scholar

Dyba, Wojciech, Bradley Loewen, Jaan Looga, and Pavel Zdražil. 2018. “Regional Development in Central-Eastern European Countries at the Beginning of the 21st Century: Path Dependence and Effects of EU Cohesion Policy.” Quaestiones Geographicae 37 (2): 77-92. https://doi.org/10.2478/quageo-2018-0017 Search in Google Scholar

Fedajev, Aleksandra, Dragiša Stanujkić, Darjan Karabašević, Willem K.M. Brauers, and Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas. 2020. “Assessment of Progress towards ‘Europe 2020’ Strategy Targets by Using the MULTIMOORA Method and the Shannon Entropy Index.” Journal of Cleaner Production 244: 118895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118895 Search in Google Scholar

Ferry, Martin, and Irene McMaster. 2013. “Between Growth and Cohesion: New Directions in Central and East European Regional Policy.” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (8): 1499-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2013.832958 Search in Google Scholar

Fratesi, Ugo, and Fiona G. Wishlade. 2017. “The Impact of European Cohesion Policy in Different Contexts.” Regional Studies 51 (6): 817-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1326673 Search in Google Scholar

Giscard d’Estaing, Valéry, Pat Cox, Romano Prodi, and José María Aznar. 2002. The Constitutional Convention on the Future of Europe: Speeches by Valéry Giscard D’Estaing, Pat Cox, Romano Prodi, José M. Aznar. London: The Federal Trust for Education and Research. https://fedtrust.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Essay_21.pdf Search in Google Scholar

Gorenflo, L. J., and Suzanne Romaine. 2021. “Linguistic Diversity and Conservation Opportunities at UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa.” Conservation Biology 35 (5): 1426-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13693 Search in Google Scholar

Grazi, Laura. 2012. “The Long Road to a Cohesive Europe. The Evolution of the EU Regional Policy and the Impact of the Enlargements.” Eurolimes. Journal of the Institute for Euroregional Studies 14.Search in Google Scholar

Healy, Adrian. 2016. “Smart Specialization in a Centralized State: Strengthening the Regional Contribution in North East Romania.” European Planning Studies 24 (8): 1527-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1184233 Search in Google Scholar

Henrard, Kristin. 2015. “The UN Declaration on Minorities’ Vision on ‘Integration’”. In The United Nations Declaration on Minorities. An Academic Account on the Occasion of its 20th Anniversary (1992-2012). Edited by Ugo Caruso and Rainer Hoffmann, 156-191. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004251564_009 Search in Google Scholar

Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. Revised and expanded 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.Search in Google Scholar

Incaltarau, Cristian, Gabriela Carmen Pascariu, and Neculai-Cristian Surubaru. 2020. “Evaluating the Determinants of EU Funds Absorption across Old and New Member States – the Role of Administrative Capacity and Political Governance.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (4): 941-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12995 Search in Google Scholar

Kapitány, Balázs. 2015. “Ethnic Hungarians in the Neighbouring Countries.” In Demographic Portrait of Hungary. Edited by Judit-Őri Monostori and Zsolt Péter–Spéder. Budapest: Hungarian Demographic Research Institute. https://demografia.hu/en/publicationsonline/index.php/demographicportrait/article/view/894.Search in Google Scholar

Kaposzta, Jozsef, and Balazs Lorinc. 2024. “Economic Analysis of Emergence of a Bipolar European Union, 2011–2022.” In Engineering for Rural Development. 23rd International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development. Edited by Vitalijs Osadcuks, Aivars Aboltins, and Janis Palabinskis, 390-5. Jelgava: Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies, Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.22616/ERDev.2024.23.TF074 Search in Google Scholar

Kiss, Tamas, Csata István, and Toró Tibor. 2020. Regionális barométer - 2019: fejlődési idealizmus, regionális identitások, korrupciópercepció, demokrácia-felfogás és magyarellenesség Romániában. Bálványos Intézet: Székelyföldi Közpolitikai Intézet.Search in Google Scholar

Marin, Maras. 2022. “The Spillover Effect of European Union Funds between the Regions of the New European Union Members.” Croatian Review of Economic, Business and Social Statistics 8 (1): 58-72. https://doi.org/10.2478/crebss-2022-0005 Search in Google Scholar