The Future of Slovakia and Its Relation to the European Union: From Adopting to Shaping EU Policies

-

Lucia Mokrá

Lucia Mokrá is Associate Professor of International and European law at the Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences at Comenius University in Bratislava. She has been a visiting professor at several other universities in Europe and is chairperson of the Trans European Policy Studies Association (TEPSA) board. Her research focuses on human rights, international relations, institutional settings and enforcement in international and European law.und Hana Kováčiková

Hana Kováčiková is Associate Professor of International and European law at the Faculty of Law at Comenius University in Bratislava. She is a member of the Jean Monnet Chair and Jean Monnet Network; her professional focus is on European Law, European Competition Law, and Public Procurement.

Abstract

The authors offer an analysis of the economic and political development of the independent Slovak Republic on its way to the EU as well as of its positions in strategic policy fields since it became an EU member state in 2004, such as migration policy, enlargement policy, the rule of law, and security on the EU’s eastern border. Slovakia’s stance vis-à-vis the values of the EU are assessed by an analysis of government programme declarations over the last 20 years. The authors show how economic success and GDP growth has influenced Slovakia’s support for EU membership, as well as how the country has positioned itself with regard to policy development and national interests on the one hand and to achieving EU goals and policies on the other.

Facing the Past before European Integration: The Development of the European Idea in the Context of Slovak Independence and Sovereignty

The foundation of the Slovak Republic was a process of “silent divorce”, when Czechoslovakia split into two sovereign countries in November 1992. As a precondition, a constitutional law had been adopted on the split of the federation that had existed from 1990 to 1992, as well as a constitutional act: the Constitution of the Slovak Republic. After the political changes of 1989, a debate emerged regarding the future state law architecture of Czechoslovakia, the status of the two parts of the federation, and the role of the federal government. Significant steps towards an independent Slovak Republic were the abolition of Article 4 of the Constitution on the leading role of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, the subsequent change of the name of the state, and the adoption of new state symbols. Important norms were adopted in accordance with the law: in particular the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (Constitutional Act No. 23/1991 Coll.), the Petition Act (Act No 85/1990 Coll. on the Right to Petition), the Association Act (Act No 83/1990 Coll. on the Association of Citizens), the Political Parties Act (Act No 424/1991 Coll. On Association in Political Parties and Political Movements), the Law on Assembly (Law No. 84/1990 Coll. on the Right of Assembly), and electoral laws that were based on democratic principles. All these were a prerequisite for the transition to a democratic society.

The gradual steps towards the Constitution of the Slovak Republic were based on the new legal regulation of the competences between the federation and the two republics by means of the Constitutional Act No. 556/1990 Coll. This constitutional regulation was focused on the gradual amendment of the federal constitution and the Constitutional Act on the Czech-Slovak Federation (Constitutional Act No. 143/1968 Coll.). The government’s draft constitution was submitted by Milan Čič, the leader of a group of experts working on the text. It was approved at a meeting of the Slovak National Council on 1 September 1992 and signed at a ceremony at Bratislava Castle on 3 September 1992. The new Constitution was published under number 460/1992 Coll. in the Collection of Laws on 1 October 1992, thus making the Constitution effective. The independent Slovak Republic came into being on 1 January 1993, when Constitutional Act No 542/1992 Coll. on the dissolution of the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic took effect. The independent sovereign Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic became the successor states of Czechoslovakia. The legal succession of the Slovak Republic meant that the constitutional laws, statutes, and other generally binding legislation remained in force unless they contradicted the Constitution on the basis of Article 152(1) of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic.

This constitutional and legal basis, which included provisions reflecting the international ambitions of the Slovak Republic, created space for the gradual integration of the sovereign Slovak Republic at the global level, with membership in organisations such as the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and at the European level, with membership in the Council of Europe and, subsequently, the European Union (EU). As a newly founded sovereign state, the Slovak Republic was not a member of any international organisations. It built on Czechoslovakia’s legacy, a founding UN member state, which helped pave the way towards membership in international organisations. This article analyses these international and European integration ambitions of the Slovak Republic from a legal and economic perspective. Our interdisciplinary approach reflects the complexity of the requirements for EU membership.

We will first present the economic and political development of the newly independent Slovak Republic from the beginning of the accession process to EU membership. Subsequently, we map the formation of Slovakia’s positions in relation to specific EU policies, with a focus on Slovak foreign policy strategies: migration, enlargement, rule of law, and, not least, the current security perspective in relation to the EU’s eastern border. We analyse the contents of government programme declarations over two decades and their compliance with the EU values as stated in the Treaty on European Union. Similarly, public opinion surveys over the same period clarify the evolution of support for EU membership, which was mainly due to Slovakia’s economic performance after its EU accession. Such an interdisciplinary analysis of two decades of Slovakia’s EU membership enables us to assess the country’s position in forming particular policies between advancing national interests on the one hand and shaping EU objectives and policies on the other.

The Slovak Route to the European Union

The Slovak Republic’s Integration Ambitions

The Slovak Republic’s interest in becoming part of the group of countries envisaged for enlargement was based mainly on Central East European regional perspectives as well as on the political necessity emerging from the transition to democracy and to a market-oriented economy. Both aspects of the transition were challenging for the new and small country. The Slovak Republic faced significant challenges, especially in the area of economic transition. In 1990, interim agreements covering trade and related issues of the Association agreements were signed, whereby the Slovak Republic—at the time part of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic—gained access to financial instruments of the European Community (EC). To improve Czechoslovakia’s market access, the EC had already decided in 1989 to include it in the Generalized System of [Trade] Preferences (GSP) for imports from Poland and Hungary and to eliminate or suspend quantitative trade restrictions as of 1 January 1990 in all member states except Spain and Portugal. These measures were later extended to imports from Bulgaria and Romania. Albania and the Baltic States began to benefit from this scheme in 1992. The economic advantages significantly helped the Slovak Republic’s transition: its economy was basically divided into heavily subsidised agriculture and so-called heavy industry, the latter of which was curtailed as a part of the economic transition. The high priority sectors of economic transition in cooperation with the EC/EU therefore included agriculture, industry, energy, financial services, privatization, investment promotion, and environment protection (Mokrá 2017, 283).

The political requirements of the time referred to the need to have sustainable and reliable institutions. The Slovak Republic, after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, basically built its institutional system from scratch. The creation of a fully functioning and independent parliament, elected by direct vote, was the first step towards meeting this requirement. The National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada Slovenskej republiky) (as the national parliament) created the constitutional and legal prerequisites for a functioning institutional system, and its first act was to adopt the Constitution of the Slovak Republic. Its political, economic, and geopolitical interest in European integration and NATO was based on the 1989 Agreement on Trade in Industrial Products between the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (CSFR, which existed from 1990 to 1992) and the EC. This agreement was replaced in 1990 by the Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation and the European Agreement on the Association of the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic with the European Community of 16 December 1991. The latter was never ratified because the CSFR dissolved into two separate countries in November 1992 (Euractiv 2005).

On 4 October 1993, the Association Agreement of the Slovak Republic with the EU was signed by prime minister Vladimír Mečiar. It was ratified by the European Parliament (EP) on 27 October and by the National Council of the Slovak Republic, the Slovak Parliament, on 15 December. As of 1 February 1995, the Slovak Republic became an EU associated country, and its official application for admission was presented by prime minister Mečiar on 27 June 1995 at the EU Summit in Cannes (SME 1995).

Political developments in the Slovak Republic before the official application for membership and also afterwards, however, provoked reactions from EU representatives who were concerned about the lack of fulfilment of the democracy criteria in the country. In fact, none of these criteria had been met. There was a lack of stability regarding institutions that guaranteed democracy, a lack of respect for the principle of the rule of law and for human rights, as well as respect for and the protection of minorities. The EU reacted to the developments after the parliamentary election of 1994 by sending a so-called demarche (political note) which was handed over on 23 and 24 November by the first German Ambassador to Slovakia Heike Zenker and French Ambassador Michel Perrin to the constitutional representatives of the Slovak Republic: president Michal Kováč, the president of the Slovak Parliament Ivan Gašparovič, and the acting prime minister Jozef Moravčík. Subsequently, on 25 October 1995, the EU representatives handed over another demarche expressing concern about the political situation in Slovakia to prime minister Mečiar (Malová, Láštic, and Rybář 2005).

As a result of these political notes, the European Commission on 16 July 1997 announced it had not included Slovakia among the candidates for EU accession talks. This assessment was subsequently reflected at the EU summit in Luxembourg on 12–16 December 1997, when the EU’s enlargement concept was discussed and finally approved. The Summit decided that the EU would conduct intensive membership negotiations with a first group of countries, namely Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Estonia, and Cyprus. Slovakia was included in the second group of countries, which had failed to fullfill the political criteria. The Slovak Republic found itself in a group with Lithuania, Latvia, Bulgaria, and Romania (Euractiv 2005).

The parliamentary elections held in Slovakia on 25 and 26 September 1998 brought the decisive change: On 1 October 1998, the EU assessed these elections as a positive step towards Slovakia’s EU integration, confirming the reciprocal positive political developments expressed at the meeting in London on 30 March 1998. On the same day, the European Commission and the Slovak Republic had confirmed the Partnership for Accession and the Slovak National Programme for the Adoption of the Acquis communautaire (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 1998). In response to these developments, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on 3 December 1998 regarding Slovakia’s candidacy for EU accession. It recommended a flexible approach towards the Slovak Republic, recommending to the Vienna Summit a few days later that it review the situation in Slovakia and to the European Commission that it prepare a new report (European Parliament 1998).

A year later, at the EU summit in Helsinki on 10 December 1999, Slovakia was invited, together with Romania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, and Malta, to start EU accession negotiations (European Council 1999). The so-called Accession Conference was held in Brussels on 15 February 2000. At the end of that year, the European Commission evaluated the Slovak Republic’s performance and praised its overall progress towards EU accession. For the first time, it was described as a functioning market economy, thus fulfilling one of the economic criteria (European Commission 2000).

After 2001, the EU assessed the political developments in the Slovak Republic positively, but reports addressed remaining shortcomings and called on its constitutional representatives to address them (Table 1). Economically, the year 1999 was the starting point for stable economic growth, which only temporarily and insignificantly slowed in the year of accession to the EU (Figure 1). The decisive meeting for the EU’s biggest enlargement to date was the Copenhagen Summit on 12–13 December 2002, when an agreement was reached on the conclusion of accession negotiations with the ten candidate countries. Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia were to be admitted on 1 May 2004.

The Slovak Republic’s final steps towards EU membership.

| Date of assessment of Slovakia | EU document/sources | Identified deficiencies |

|---|---|---|

| 5 September 2001 | EP resolution on Slovakia’s progress towards EU membership. The document, authored by Dutch MEP Jan Marinus Wiersma, welcomed the progress made but also highlighted deficiencies. | Financial control, agriculture, environment, justice, domestic affairs |

| 13 June 2002 | EP resolution on enlargement in Strasbourg highlighting Slovakia’s progress in preparing for EU membership. | Persistent corruption in the public sector |

| 9 October 2002 | EC regular report on Slovakia’s preparations for EU membership. The developments since 1997 were assessed, when, according to the Commission, Slovakia had made significant progress. The EC formally recommended the admission of the republic and nine other candidate countries to the EU in 2004. | N/A |

-

Source: Mokrá 2017; Directorate-General NEAR of European Commission 1997–2004. Commission Opinion on Slovakia’ s Application for Membership of the European Union. 15 July 1997. Brussels. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:51997DC 2004 (accessed 21 August 2023); Enlargement of the European Union. Official Position of the European Parliament. Resolutions Adopted by the European Parliament., n.d., Brussels. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement_new/positionep/resolutions_en.htm and https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/positionep/default_en.htm (accesssed 21 August 2023).

Annual GDP growth (%) in Slovakia, 1993–2004. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

On 17 February 2003, in accordance with the Constitution, the Slovak president Rudolf Schuster called a referendum, to be held on 16 and 17 May 2003 on the question: “Do you agree that the Slovak Republic should become a member of the EU?” Of those who voted, 92.46 % were in favour; 6.2 % answered in the negative. More than half (52.15 %) of the citizens who were eligible to vote had gone to the polls (Štatistický úrad SR 2003). Meanwhile, on 9 April 2003, the European Parliament in Strasbourg approved the admission of Slovakia and the nine other countries. There were 521 MEPs who voted for Slovakia’s accession, 21 voted against and 25 abstained (Euractiv 2005). After the European Parliament, the EU Council, which is composed of the EU countries’ foreign ministers, formally approved the ten countries’ admission on 14 April 2003. Based on these votes and the referendum, the Treaty on the Accession of the Slovak Republic to the EU was signed by president Schuster and prime minister Mikuláš Dzurinda at the EU Summit in Athens on 16 April 2003. On 1 July 2003, the Slovak parliament agreed to the Treaty. Of the 140 voting members in the Slovak Parliament, 129 approved, 10 voted against, and 1 abstained from voting (Euractiv 2005). On 26 August 2003, president Schuster signed the instrument of ratification of the Treaty, thereby ratifying the country’s EU accession. Its first EU Commissioner was Ján, who had been the Republic’s chief EU negotiator. Following the elections of 13 June 2004, Figeľ was flanked by 14 members of the European Parliament (MEPs).

Neither the Constitution of the Slovak Republic nor the legal system as it emerged in connection with the establishment of the independent Slovak Republic on 1 January 1993 contained special provisions on the legal status of the regulations of the European Communities/European Union. Accordingly, a legal prerequisite for Slovakia’s membership in the EU was a modification of the Constitution so that it would allow accession to the EU and establish the primacy of EC and EU legal acts over the laws of the Slovak Republic (National Council of the Slovak Republic 2001).

Expectations and Capability Dilemma

From the very beginning, the expectations accompanying Slovakia’s EU membership were directed towards the achievement of the so-called “Western standard”, especially with respect to economic well-being as well as with respect to a fundamental qualitative shift of financial remuneration, economic, and labour market development and institutional reinforcement. Opinion polls conducted in 2003, shortly before accession, accentuate these expectations, even though fear had set in: a third of the citizens (34 %) had less positive expectations of EU membership, compared to five years earlier. Less than a fifth of respondents (18 %) said that their positive expectations had increased over these five years, and almost a third (31 %) said their expectations had not changed. 12 % did not have positive expectations at all. The most frequent respondents who reported such a decrease in positive expectations were 50–59 years old (41 %), unskilled workers (43 %), the unemployed (42 %), respondents from small cities with 10,000 to 50,000 inhabitants (42 %) and from those with over 100,000 inhabitants (40 %). Positive expectations remained particularly unchanged among people 40–49 year old (36 %), entrepreneurs (39 %), the university-educated (37 %), and employees (36 %). An increase in positive expectations was particularly characteristic of people 25–29 year old (26 %), entrepreneurs (33 %), the university-educated (24 %), and skilled workers (24 %). Those who answered indifferently were predominantly aged 60 and over or had only primary education (20 % each) (SME Domov 2003).

In terms of content, the same opinion poll showed that between 30 and 35 % of respondents expected EU accession to have a positive effect on the development of tourism, the protection of human rights—and especially the rights of national minorities—the alignment of the legal system with EU legislation, and the international position of Slovakia. The most sceptical expectations—improvement only after more than 20 years—prevailed in relation to the development of the standard of living. This was particularly evident in the answers of skilled workers (27 %) and the unemployed (26 %). No positive effects were expected from EU integration in addressing the situation of Slovakia’s Roma population or the development of agriculture (SME Domov 2003).

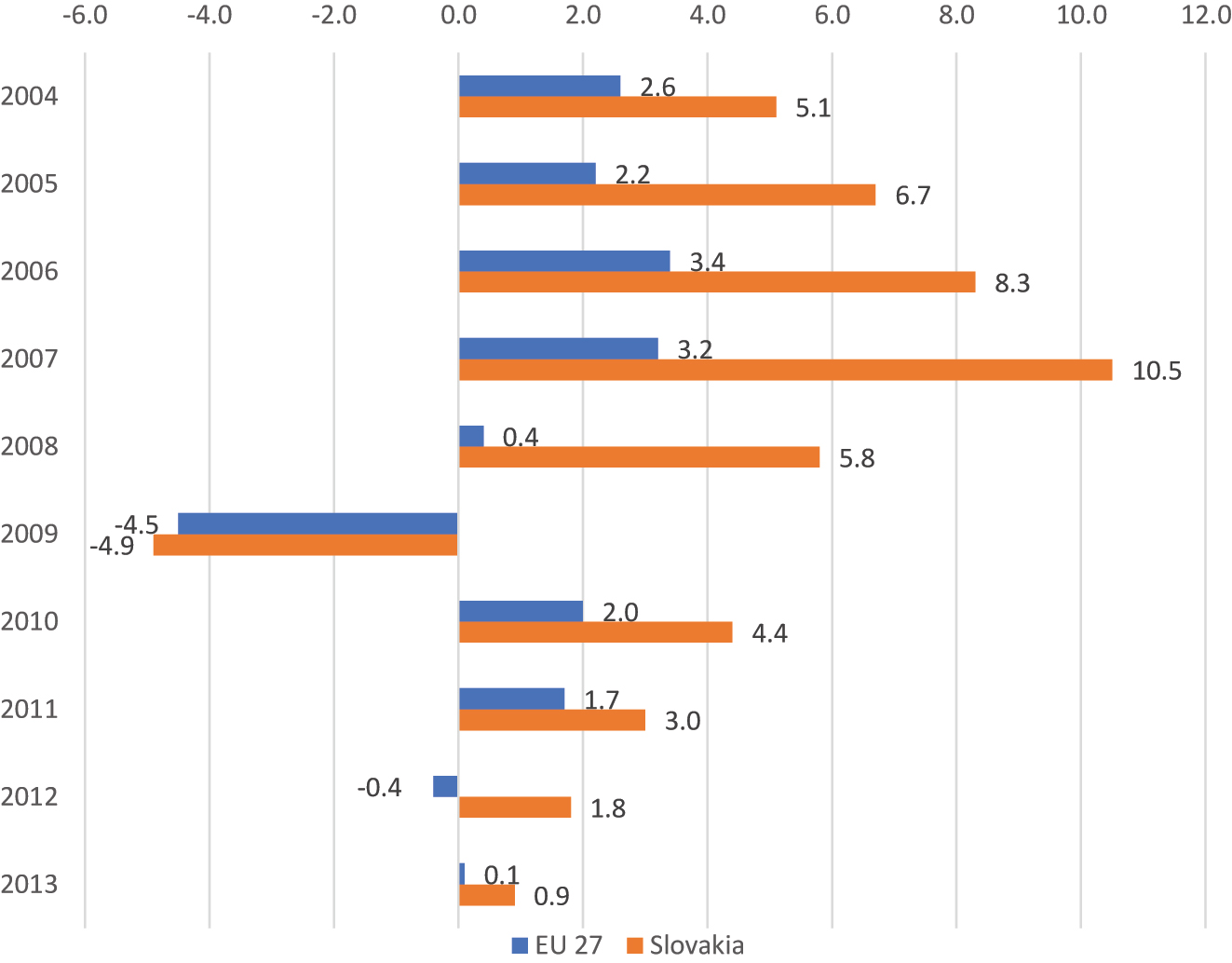

Ten years later, economic expectations especially had been fulfilled (Figure 2): Slovakia’s EU accession has had a positive impact on its gross domestic product (GDP), even if it was not the only factor facilitating this development. Thanks to EU membership, Slovakia was also able to mitigate the impact of the global economic crisis on its economy. Expressed in purchasing power parity, Slovakia’s economic performance rose from 57 % of the EU average in 2004 to 75 % in 2013. Comparing the four countries of the Visegrád group (V4), Slovakia showed the strongest growth in this first decade of EU membership (Figure 3).

Real GDP growth of the EU and Slovakia (2004–2013) in %. Source: Fórum pre medzinárodnú politiku 2014. “Hodnotiaca správa o 10 rokoch členstva SR v EÚ.” 2 July. Bratislava. http://mepoforum.sk/kniznica/europa-k/slovenska-republika-k/zahranicna-politika-k/hodnotiaca-sprava-o-10-rokoch-clenstva-sr-v-eu/ (accessed 21 August 2023).

Economic performance of the V4 countries as % of the EU27 average (GDP per capita in purchasing power parity). Source: Fórum pre medzinárodnú politiku 2014. “Hodnotiaca správa o 10 rokoch členstva SR v EÚ.” 2 July. Bratislava. http://mepoforum.sk/kniznica/europa-k/slovenska-republika-k/zahranicna-politika-k/hodnotiaca-sprava-o-10-rokoch-clenstva-sr-v-eu/ (accessed 21 August 2023).

These positive economic results notwithstanding, the fight against tax fraud and tax evasion remained a key challenge for Slovakia’s fiscal policy. In the field of value added tax (VAT) especially, the focus was on measures to effectively combat serious forms of fraud. For example, a rapid response mechanism was introduced, and the possibility of applying self-taxation to domestic transactions was extended. In the fields of direct taxation and administrative cooperation, the existing legislative instruments were improved, and new initiatives combatted tax fraud and tax evasion in line with the recommendations of the European Commission (Fórum pre medzinárodnú politiku 2014, 7).

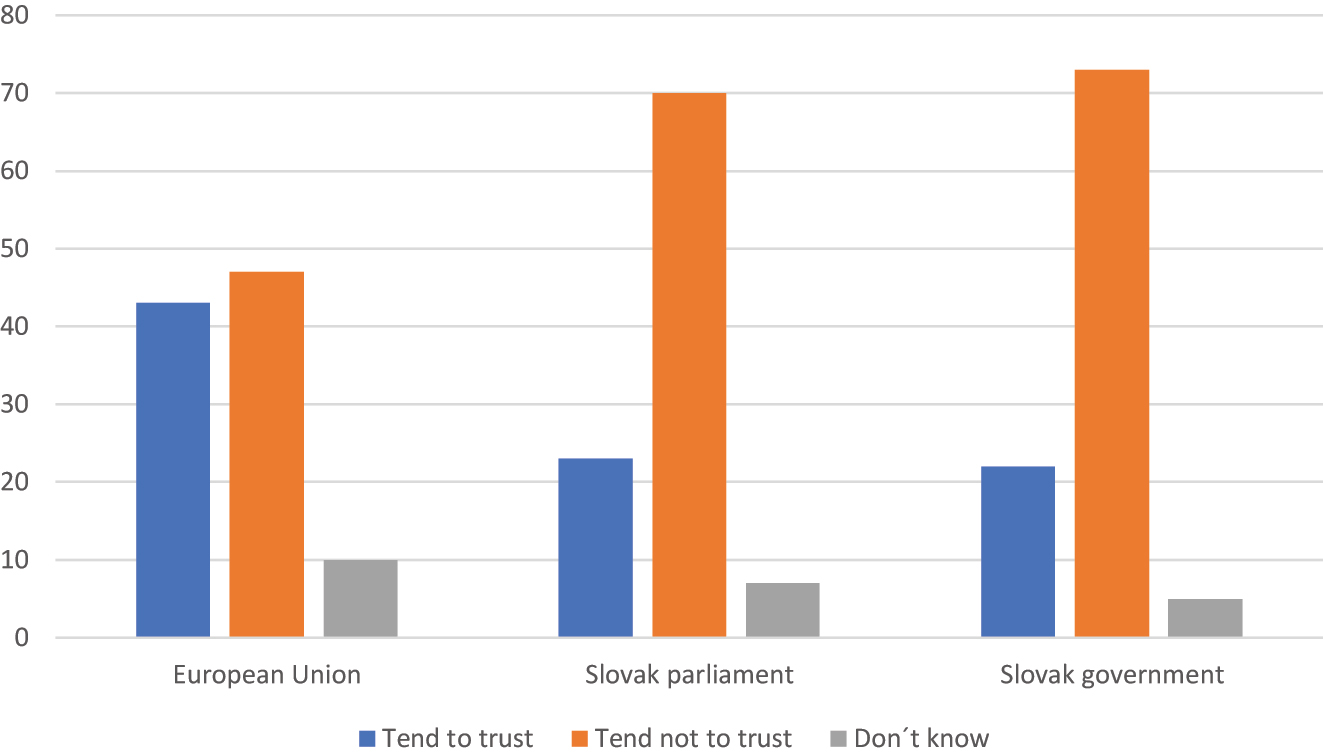

After almost 20 years of EU membership, the expectations are still very high, reflecting both Slovakia’s economic development and a number of political ones. The Eurobarometer results of 2022 show that 73 % of Slovaks perceive the EU positively or neutrally. The perceived biggest benefits of membership remain connected to the common market and economic well-being, such as the free movement of people, goods, and services, peace between member states and the common currency, the euro, which Slovakia adopted on 1 January 2009. But more than half of the respondents are satisfied politically as well, seeing democracy in the EU as functioning and European institutions worthy of higher trust than national ones (Figure 4). In recent years, political trust in the EU has been above 40 %, and most European policies have been strongly supported by the Slovak population (Eurobarometer 2022).

Comparison of trust of Slovak citizens in the EU and in the Slovak parliament and government (in %). Source: Eurobarometer Winter 2021–2022. Standard Eurobarometer 96.3. European Commission. Brussels. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=81534 (accessed 14 August 2023).

The recent crises brought additional benefits of EU membership, which were never part of any “expectations”. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU represented solidarity and togetherness when joint action and negotiations by the European Commission ensured that effective vaccines reached Slovakia at the same time as all other member states and facilitated the purchase of medical supplies. In response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, EU member states have joined forces and are taking joint action to support Ukraine (Zastúpenie na Slovensku 2022). In Slovakia, both the EU’s response to the pandemic and to the attack on Ukraine have additionally strengthened support for the EU. Paradoxically, however, despite their widespread support in opinion polls, Slovak citizens’ participation in the European Parliament’s elections and in European citizens’ initiatives has long been among the lowest, as we will show in the following section.

Slovakia and EU: A Relation of Dancing In and Out

As the Czech economist Růžena Vintrová observed in 2004, a “crucial factor in the post-accession period will be how the new member states manage to exploit the new opportunities open to them for catching up” (Vintrová 2004, 521). In 2019, Gyarfášová and Mokrá reminisced that “Slovakia entered the EU with big enthusiasm and with the feeling ‘we made it’, because at the end of the 1990s it was not clear whether Slovakia was going to catch up on its integration deficit and whether it may become a member of the western-democratic clubs with other post-communist countries” (Gyarfášová and Mokrá 2019, 111). Since its EU accession, Slovakia has reached several milestones when it comes to political discourse and public perception of EU membership as well as concerning its conduct within EU policy fields.

The most prominent areas in which the relationship between the EU and Slovakia has been subject to turbulence have also been major issues more generally within the EU. Migration was one of these, but it was particularly prominent in Central East European countries. In spite of its relatively large ethnic minorities, Slovakia perceives itself as culturally homogeneous. It had minimum experience with incoming migration during the 20th century and thus with the questions of integration and inclusion connected with this. In June 2017, there were 97,934 foreigners registered in Slovakia, only 1.8 % of the population. Still, this was a considerable increase, as the number of foreigners in 2004 had been 22,108. In 2015, during the so-called “refugee crisis”, the Slovak government clearly opposed the EU relocation scheme, refusing to accept any migrants. Slovakia sued the European Council for its refugee distribution plan (joined cases C-643/15 and C-647/15), losing the case based on its inappropriate argument of a procedural error in adopting the decision. But it continued to blame the EU afterwards as well for imposing something on Slovakia that it clearly did not wish to follow. As a political response, Slovakia presented the principle of flexible solidarity in relation to migration during its presidency of the Council of the EU, but this too was unsuccessful at the European level (European Council 2016). The strengthening of Slovakia’s competences and capacities in dealing with migrants and refugees as well as its support on several levels, such as when it collaborated with Austria in 2015 and 2016 in providing shelters to asylum seekers and with the creation of joint police teams in Greece under EU auspices, may efficiently contribute to the de-escalation of hate speech and negative attitudes towards migrants in Slovakia.

The creation of the European Financial and Stabilisation Mechanism in 2011 was another policy area Slovakia reacted negatively to. The issue of solidarity with Greece, a member of both the European Union and the eurozone, led to a domestic political redistribution of forces and strengthened Eurosceptic sentiments in Slovakia. It even led to early elections in 2012: now the governing coalition was formed by Freedom and Solidarity (Sloboda a Solidarita, SaS), Most-Híd, and the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union – Democratic Party (Slovenská demokratická a kresťanská únia – Demokratická strana, SDKÚ-DS). One of the coalition parties (Sloboda a Solidarita) refused to support the mechanism (National Council of the Slovak Republic 2011).

The Covid-19 pandemic, on the other hand, produced a wave of solidarity within the EU that included Slovakia. Slovakia’s official position is that solidarity with other partners should be interpreted from a member state’s perspective while also being offered across borders within the EU and across EU borders. This includes economic support from the common budget, as happened on many occasions in the EU’s history. As the Slovak state secretary of foreign affairs Ivan Korčok put it in his presentation of the annual report on the Slovak Republic’s EU membership, it “is necessary to show solidarity within the EU, but also beyond, towards our partners in Africa, the Western Balkans and the Eastern Partnership countries. The entire EU is based on the principle of solidarity, and the Slovak Republic wants to be part of the system of aid and solidarity” (Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí Slovenskej republiky 2021, 4).

The Slovak government’s wish to be seen as a solidarity leader was not always successful: “Slovakia’s efforts to shape the EU’s policy have been a blend of solidarity and pragmatism, a permanent renegotiation between ‘the logic of appropriateness’ and the ‘logic of consequentialism’” (Najšlová 2011, 101). Under the European Commission’s coordinated effort (European Commission 2020a) Slovakia offered to contribute to the development of a vaccine against Covid-19, but this contribution was not financial support of the World Health Organization (WHO). Rather, it consisted of a contribution in kind: through activities not only in the WHO, but also in the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), United Nations Multi-Partner Trust Fund (UN MPTF), the UN’s centre of expertise on pooled funding mechanisms. In the words of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, “Slovakia has provided material humanitarian assistance in the form of medical supplies and equipment and has implemented several bilateral projects in partner countries aimed at combating Covid-19” (Zachová and Yar 2021).

Slovakia has also strongly supported the coordinated approach of the European Union to the situation in Ukraine (European Council 2022). It has unequivocally supported the various sanctions packages against Russia adopted at the EU level. In addition, it has been helping fleeing Ukrainian citizens, has accepted Ukrainian pupils into Slovakia’s educational system, created a system of accommodation for those arriving, coordinated processes relating to applications for temporary refuge under European legislation, and also adapted national legislation, the so-called Lex Ukrajina, which allows for Ukrainians’ simplified access to the labour market, universities, social support, and healthcare (Sekulova 2022). The Slovak Republic thus has been selective about which policy areas to support and which to exercise reservations towards.

Slovakia’s Strategic Vision of the Future of the European Union

How does the EU envision its future? The Treaty on European Union states that it is the creation of an economic and monetary union whose currency is the euro (Article 3(4) TEU). Some time has surely passed since this treaty was drafted, and the geopolitical scene has changed a great deal as well. The EU has been facing many challenges that tested its resilience, solidarity, and unity. Brexit opened up a Pandora’s box with “nation first” voices sounding much louder than before. Working towards a solution, the EU launched a Conference on the Future of Europe, providing EU citizens a platform for debate. The outcome of such a debate was presented in a final report. Citizens had given the EU a strong mandate for deepening integration (Conference on the Future of Europe 2022b). So, what did Slovakia’s government compliance with EU standpoints look like? And how much has its economy integrated with the EU’s common market and its economic instruments?

Political Standpoints

Examining the government program declarations (programové vyhlásenie vlády) since Slovakia’s EU accession, we shed light on what kind of EU Slovakia would like to see. Has it just been promoting EU values, or has it actually implemented them? Since the year of accession, 2004, Slovakia has seen eight governments. The first, legislative, period, which ended with early elections, was headed successively by Mikuláš Dzurinda (2002–2006), Robert Fico (2006–2010), Iveta Radičová (2010–2012). The second period saw first Robert Fico (2012–2016 and 2016–2018) at the helm and ended with a change of prime minister without early elections. In the third period first Peter Pellegrini (2018–2020) and then Igor Matovič (2020–2021) were in charge, and this period also ended with a change of prime minister without early elections: Eduard Heger (2021–2023). As of the time of writing this article, Ľudovít Ódor has been leading an interim government of experts installed by president Zuzana Čaputová and tasked with leading the country from May 2023 until the next elections take place in September.

Seven government programme declarations have been introduced since 2004. After becoming an EU member state, integration goals such as accession to the monetary union and the full application of the Schengen law were announced. The government under Mikuláš Dzurinda advocated for an EU that would “take due account of the influence of its member states, regardless of their size, as well as of the preservation of national identities in cultural and ethical matters” (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2002, 40). The subsequent government of Róbert Fico declared “a vigorous defence of national and state interests”, but this was qualified by the aim to “support the deepening of partnership and strategic cooperation within the EU”, as well as the European integration process, which included the envisaged ratification of the treaty establishing a constitution for Europe. At the time, Slovakia explicitly referred to the EU’s values as its own (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2006, 54).

A few years later, in 2010, Iveta Radičová’s government stressed the need to substantially strengthen EU level mechanisms “with a view to stabilis[ing] public finances in the eurozone in the long term”. Despite the fact that this government clearly called for due application of the principle of subsidiarity and proportionality, it explicitly declared, as the only government in Slovak history to do so, that Slovakia would “participate in the redistribution of migrants in the resettlement process, accept migrants from European Union countries affected by a large influx of migrants, respectively from countries for which humanitarian aid has been agreed at EU level”. This was, of course, a few years prior to the so-called refugee crisis when such redistribution mechanisms were to become more acute than ever (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2010, 47).

The second Fico government, which replaced Radičová’s in 2012 after early elections, abandoned the themes of migration and solidarity. It declared the necessity of a “deeper coordination of budgetary policies” and emphasized its “clear pro-European attitude”. A new important goal was to “bring the EU closer to its citizens so the deepening of integration processes following the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty would be better understood” (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2012, 7). The rule of law, resilience, the prevention of further fragmentation and enforcement of the internal market through the envisaged Energy Union, the Single Digital Market and Capital Markets Union were among the most important goals presented by the third Fico government. Peter Pellegrini, who replaced Róbert Fico as a prime minister in 2018 after massive civil protests, continued to adhere to these goals as he represented the same political party (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2016, 5).

The current government programme declaration, issued in 2021 and in force until 2024, shows continuity with previous programs and aims “to strengthen the perception of the EU agenda as a part of domestic policies […], full restoration, functioning and further development of the common market, as well as the elimination of all discriminatory barriers, […] enforcement of the rule of law” as long as the principle of subsidiarity is met. There is still a clear reservation towards EU migration policy as it denies the policy of compulsory relocations while claiming that the asylum process must remain in the competence of the member state (Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2021, 116). The only area in which this standpoint was mitigated was rin connection with the refugee waves triggered by the Russian attack against Ukraine.

Slovakia’s governments have thus consistently proclaimed a compliance of national values with those of the EU. They all have welcomed a deeper integration at least when it comes to the Common Market, the Energy Union, the Single Digital Market and the Capital Markets Union. Moreover, a deeper coordination and effective enforcement has been welcomed in the fields of fiscal regulation and the rule of law. Slovakia was among the countries that ratified the then stalled Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe in 2005. The “Strategic Foresight for the Foreign and European Policy of the Slovak Republic”, an elaborate strategic programme issued by the Slovak Foreign Ministry in the face of the world’s multiple crises, further sustains Slovakia’s pro-EU orientation and was adopted across the entire political spectrum (MZV 2022).

The Eurobarometer survey of winter 2021–2022 testified to Slovak citizens agreeing to the pro-European ways of their government. A significant majority of Slovaks (76 %) perceive themselves as EU citizens. More than half (59 %) know what rights they enjoy as EU citizens. A path towards deepening integration, towards a European economic and monetary union, is perceived positively by 78 % of Slovaks, and so is the euro (60 %) (Eurobarometer 2022). To sum up, Slovak citizens comply with the outcomes of the Conference on the Future of Europe as much as with the continuous pro-EU attitude of their governments.

The Correlation of Economic Performance Development and EU Membership

Adding to what was said about the economy above, in this section we correlate Slovakia’s performance with its EU membership. This includes, for example, GDP comparison with other member states, the development of trade relations, the efficiency of using EU funds, the modernisation of export structures, and an analysis of foreign direct investments.

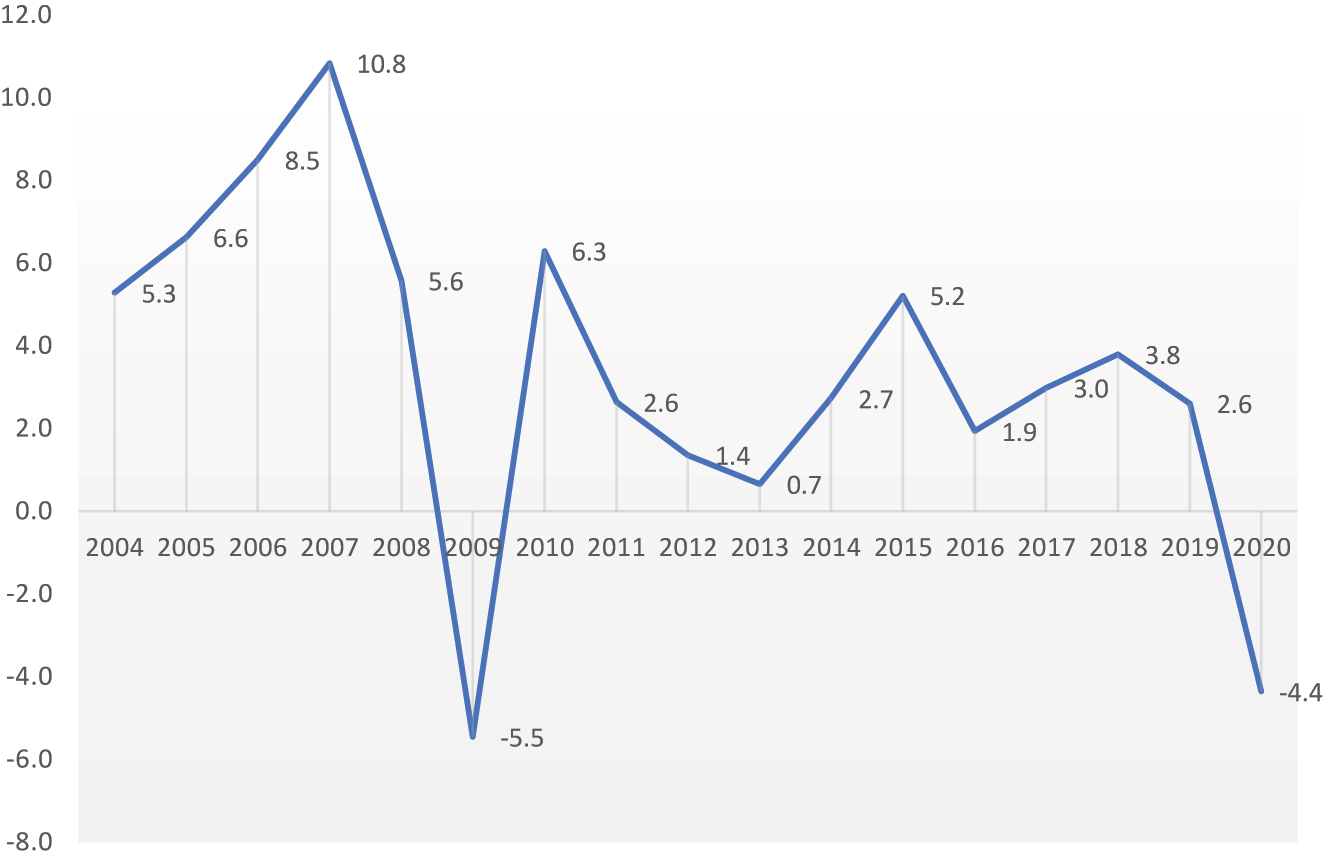

Comparing GDPs

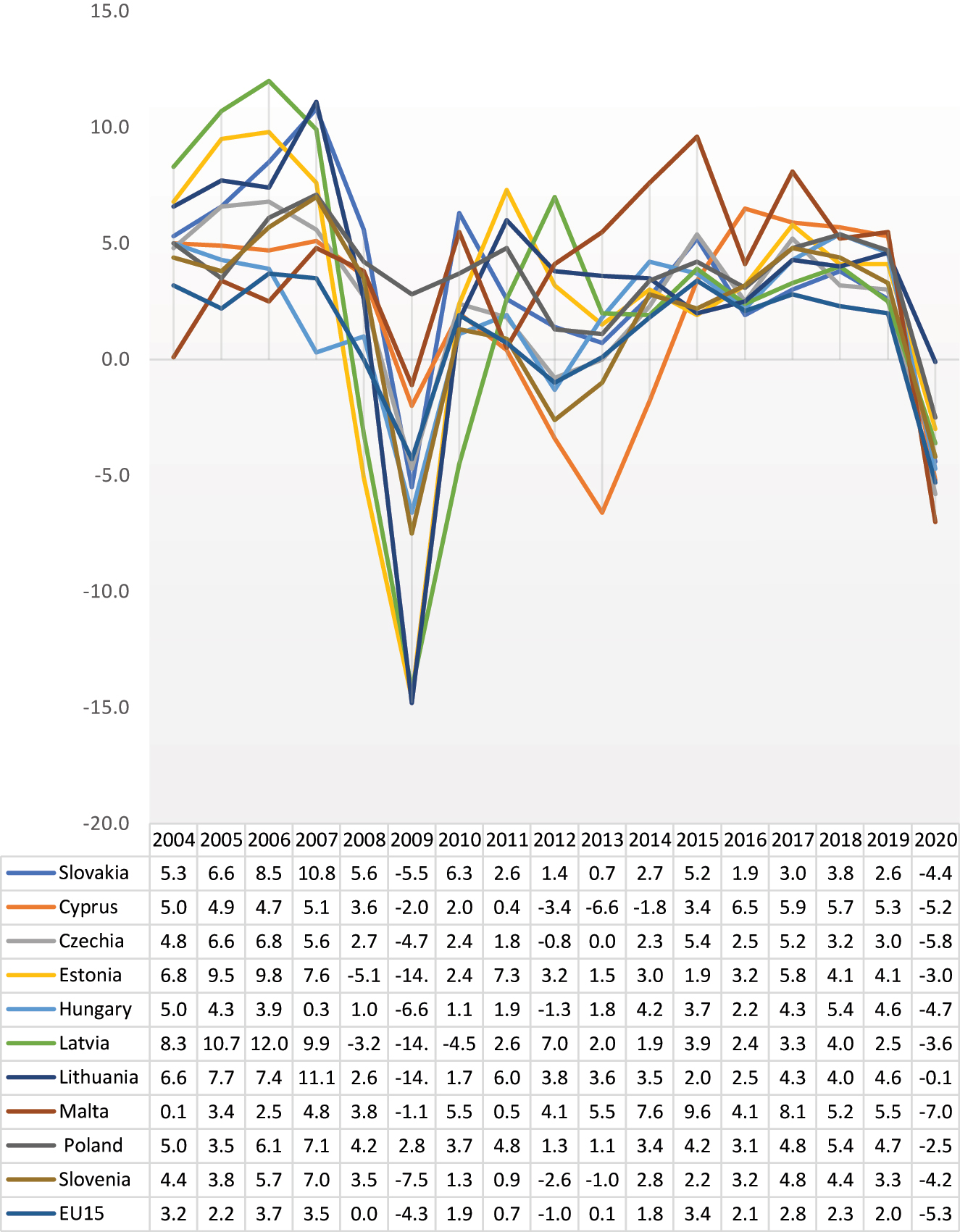

We compared Slovakia’s levels of annual GDP growth (Figure 5) with the GDP per capita, PPP (Figure 6). The average GDP growth in Slovakia between 2004 and 2020 was 3.4 %. The GDP growth rose gradually until the 2008–2009 economic crisis, when it fell drastically to −5.5 %. From that point, the GDP growth reached a maximum of 6.3 % in 2010, which has not yet been superseded. Despite the deceleration, however, GDP growth remained positive for the next decade until the Covid-19 pandemic broke out (Figure 5).

Annual GDP growth (%) in Slovakia, 2004–2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

GDP per capita, PPP (in $) in Slovakia, 2004–2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

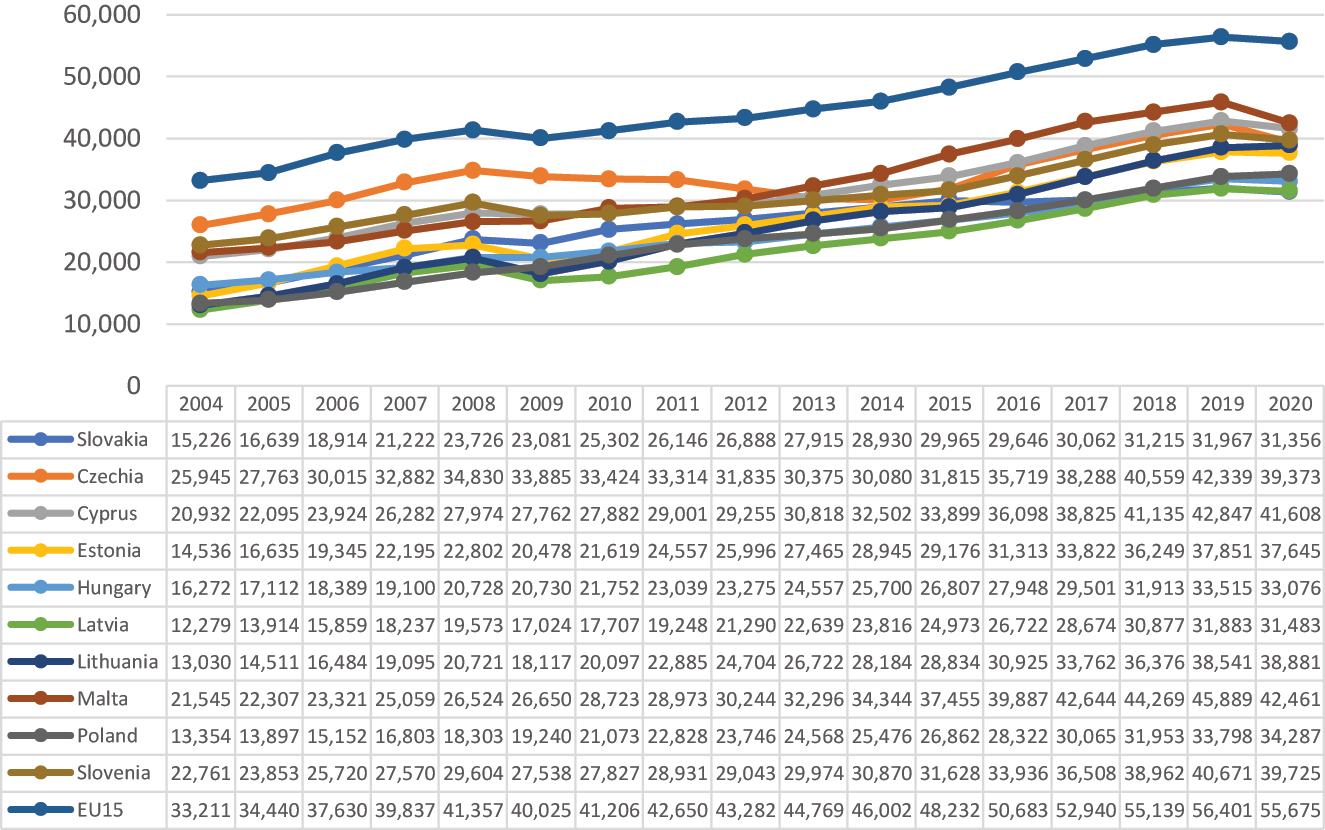

Surprisingly, these economic swings have not had a significant effect on the growth of GDP per capita, PPP in Slovakia (Figure 6). Since 2004, it has more than doubled from $15,226.34 to $31,356.46 in 2020. Moreover, despite the global economic crisis in 2008–2009 and the Covid-19 pandemic significantly lowering and slowing GDP growth, no similar effects to the GDP per capita, PPP occurred, which basically continues to be an increasing curve, lowering only a little, counting in hundreds of $ (from $23,725.86 in 2008 to $23,080.59 in 2009 and from $31,966.55 in 2019 to $31,356.46 in 2020).

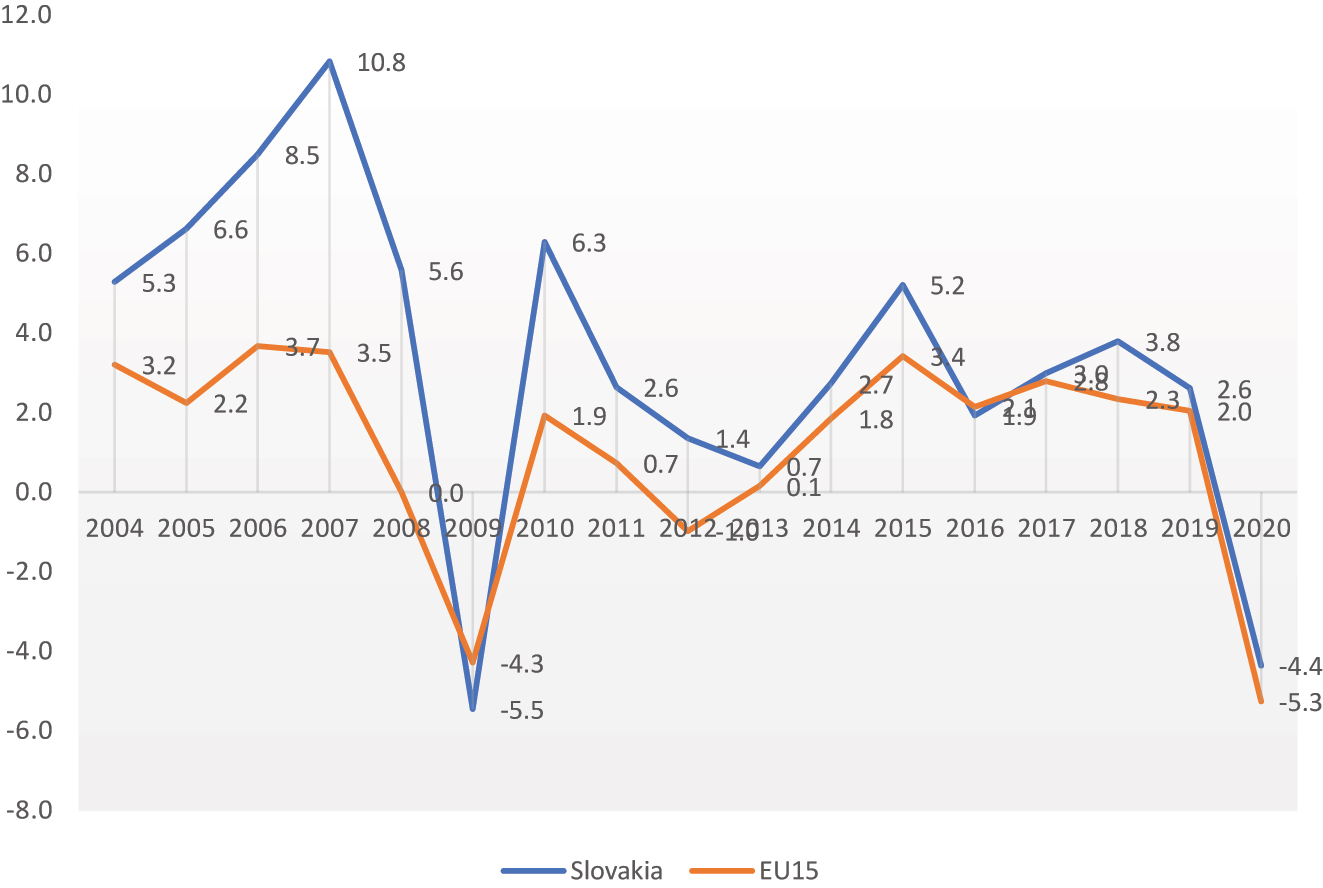

What does the Slovak performance look like when compared to the EU15, i.e. the EU member states prior to the enlargement of 2004 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom)? Has Slovakia caught up with them yet? And what can be said about the comparison with the fellow member states since 2004? Slovakia’s average GDP growth of 3.4 % was not matched by the EU15—here the average was only 1.1 % (Figure 7). But in the EU15 as well, slow GDP growth did not preclude the growth of GDP per capita, PPP (Figure 8).

Annual GDP growth (%) – Slovak Republic versus EU15, 2004–2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

GDP per capita, PPP ($) – Slovak Republic versus EU15, 2004–2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

Clearly, Slovakia has not reached the level of average GDP per capita, the PPP of the former EU15 group. But some improvement is observable: in 2004, the level of the Slovak GDP per capita was 45.85 % of the EU15 GDP, while in 2020 it was 56.32 %. It is also a fact that the Slovak GDP per capita in 2020 was still lower than the average EU15 GDP in 2004, even though it doubled in these 15 years (from $15,226 in 2004 to $31,356 in 2020). Without a doubt, the economic cooperation between EU member states, particularly the common market and competition regulation, influenced the growth trajectory.

The situation of the other member states that accessed to the EU in 2004 has been similar to Slovakia’s. They too suffered from economic swings, but, like Slovakia, their average annual GDP growth remained higher than the EU15 one (Figure 9). Of these countries, Malta and Poland had the highest average annual growth of GDP (3.7 %), followed by Slovakia (3.4 %), Lithuania (3.3 %), Estonia (2.8 %), Latvia (2.6 %), Cyprus (2.4 %), Czechia (2.0 %), Slovenia (1.9 %), and Hungary (1.9 %).

Annual GDP growth (%) – 2004 enlargement states versus EU15, 2004–2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

Like Slovakia, none of the other new member states managed to reach the average GDP per capita, PPP of the EU15 by 2020. Unlike Slovakia, however, there are states that exceeded previous EU15 averages and thus were effectively closer to “catching up” with them. In 2020, Cyprus ($42,461.25) and Malta ($41,608.03) exceeded the EU15’s average of 2010 ($41,206.01). Slovenia ($39,725.26), Czechia ($39,373.41), Lithuania ($38,880.55), and Estonia ($37,645.22) exceeded EU15’s average of 2006 ($37,629.72). Poland ($34,286.99) reached the EU15’s average of 2004 ($33,210.73). Hungary ($33,075.92) and Latvia ($31,482.68), like Slovakia ($31,356.46), did not even reach that average in 2020 (Figure 10).

GDP per capita, PPP ($) – 2004 enlargement states, 2004–2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

Slovakia’s economic indicators are not much better, even if we consider the EU28 in 2020, given that it is 25th. The only state from the EU15 which Slovakia managed to overtake is Greece. Croatia and Bulgaria are also behind Slovakia, but they accessed to the EU at a later stage (Figure 11). Given that the convergence of economies is one of the EU’s aims, the disparities are significant. It seems that politicians and lawmakers need to be reminded at every available possibility to keep sight of this in their policy making.

GDP per capita, PPP ($) – EU28 in 2020. Source: The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).

Development of Trade Relations

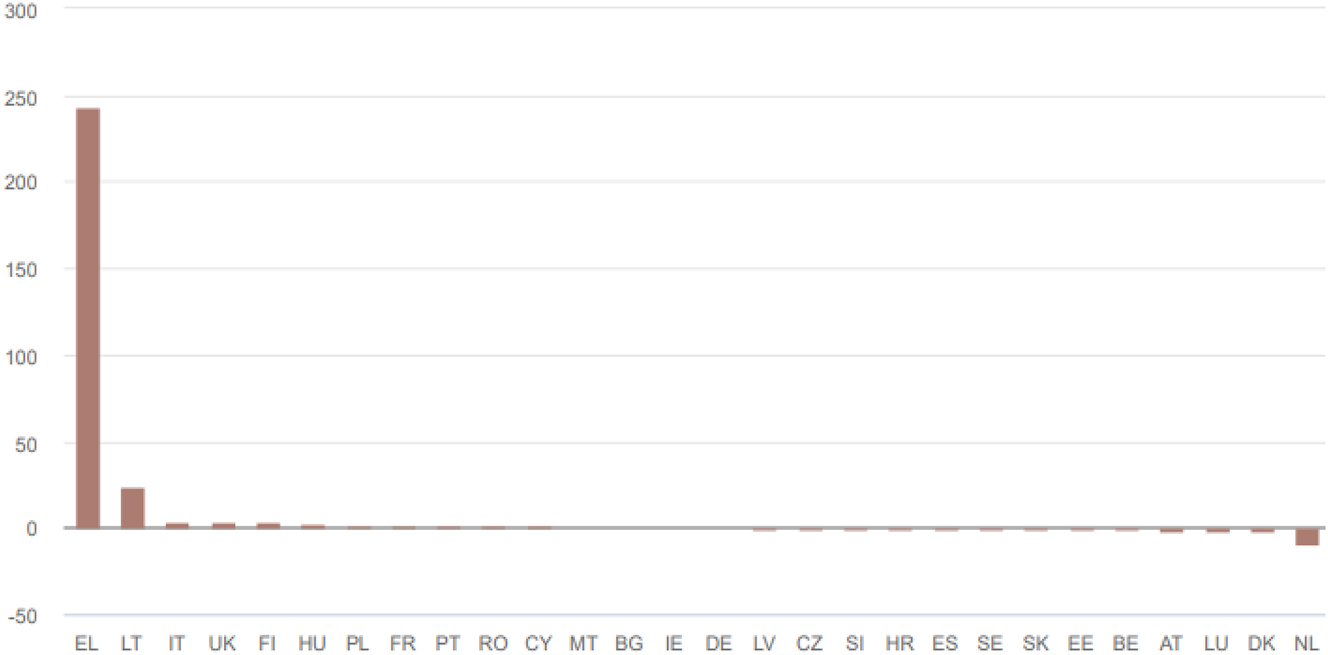

Traditionally, Slovakia has been an export economy, which is why our data indicators retrieved from Eurostat focus on where Slovakia stands in intra-EU trade relations when it comes to trade. Between 2002 and 2021, Slovakia’s balance of intra-EU trade rose from 990 million to 2091 million euros. Its annual average export growth rate compared to other member states in that time period was 9.1 %, which put Slovakia in 6th place of all member states (Figure 12). Moreover, if the spotlight is put on Slovakia’s performance in comparison with its fellow member states of 2004, it shows rather stable trade export relations (Figure 13).

Annual average growth rate – Slovakia’s exports of goods within the EU (2002–2021). Source: Eurostat Database (DS-057009). Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=452727 (accessed 21 August 2023).

Intra-EU goods: exports divided by imports 2004–2021, enlargement states of 2004. Source: Eurostat Database (DS-057009). Eurostat. Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=452727 (accessed 21 August 2023).

The Role of Foreign Direct Investments

Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) are a component of the investments made in an economy. As such, they can play a role in spurring economic growth and the creation of jobs in the receiving economy. Moreover, the level of FDI may indicate—among many other factors—an economy’s particular attractiveness or competitiveness. Measuring the levels and trends of FDIs is thus a relevant exercise in assessing a country’s performance (European Commission 2020b).

The European Commission recently provided a Single Market Scoreboard for the period from 2017 to 2018. The accumulated indicators reflected the relative attractiveness of Slovakia and the other EU member states. Negative FDI flow data indicate reverse investment, or disinvestment, in which at least one of the three components of FDI (equity capital, reinvested earnings, or intracompany loans) was negative and not offset by positive amounts of the remaining components (European Commission, 2020b). Changes in the level of inward intra-EU FDI flows show that Slovakia, whose score is below 0, has tended to lose its attractiveness for investors (Figure 14). A negative trend for Slovakia also appeared in the level of outward intra-EU FDI flows (Figure 15). It may be that policy measures taken in other countries have contributed to modifying incentives or creating barriers to investment. Finally, the situation is even worse in inward extra-EU FDI flows (Figure 16) and almost the same in outward extra-EU FDI flows (Figure 17).

Change in inward intra-EU FDI flows, 2017–2018. Source: European Commission 2020b. Single Market Scoreboard. Foreign Direct Investments. European Commission. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/internalmarket/scoreboard/docs/2020/07/integrationmarketopenness/fdien.pdf (accessed 14 August 2023).

Change in outward intra-EU FDI flows, 2017–2018. Source: European Commission 2020b. Single Market Scoreboard. Foreign Direct Investments. European Commission. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/internalmarket/scoreboard/docs/2020/07/integrationmarketopenness/fdien.pdf (accessed 14 August 2023).

Change in inward extra-EU FDI flows, 2017–2018. Source: European Commission 2020b. Single Market Scoreboard. Foreign Direct Investments. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/internalmarket/scoreboard/docs/2020/07/integrationmarketopenness/fdien.pdf (accessed 14 August 2023).

Change in outward extra-EU FDI flows, 2017–2018. Source: European Commission. 2020b. Single Market Scoreboard. Foreign Direct Investments. European Commission. Brussels. July. https://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/scoreboard/_docs/2020/07/integration_market_openness/fdi_en.pdf (accessed 14 August 2023).

Slovakia’s Future in the EU: Interests and Policies

Slovakia is pursuing several policy priorities within the EU, the most visible of which include the enlargement of the EU, particularly to include the Western Balkan countries, the fight against corruption, the protection of online space, and the promotion of the rule of law and democracy. It committed itself to contributing to the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy, especially with regard to the Western Balkans, the European Neighbourhood Policy, and the Eastern Partnership. Slovakia’s core policy interests are democracy promotion and transformation, energy security, citizen service, and crisis management (Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí Slovenskej republiky 2021). Slovakia also considers the stability of the Southern Neighbourhood to be a strategic interest of the EU. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Barcelona Process in 2020, the EU looked for ways to strengthen its partnership with the southern Mediterranean countries, similar to the Western Balkan countries and Eastern Neighbourhood, to which Slovakia contributed by sharing the experiences of experts working on the ground (e.g. MEP Vladimír Bilčík as the chair of the EU-Montenegro relations, vice-chair of EU-Serbia relations, Lucia Mokrá as the expert for Serbian accession process in relation to its approximation to chapter 23, Human Rights and Judiciary) (European Parliament 2022c).

The Slovak Republic also considers it strategic to regulate and strengthen the powers of the EU in the fight against populism and the growing influence of disinformation campaigns and conspiracy theories to manipulate public opinion and undermine trust in democratic institutions and decision making. It contributed to drafting appropriate legislation; in particular, it strongly supported the establishment and subsequent operation of the Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union (INGE). In the 18 months of INGE’s mandate, Slovakia contributed to the analysis of the disinformation and propaganda and its impact on the functioning of the rule of law and democratic processes in the EU and its member states, but also to related aspects, such as how foreign money is used to undermine democracy in the EU or how the necessary critical infrastructure and information sharing may prevent the negative impact of disinformation campaigns in relation to LGBTI+ people, migrants, and other minorities in the EU (European Parliament 2022a). In this case, both the Slovak Parliament and the European Parliament (Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí Slovenskej republiky 2021), with the strong support of the Slovak MEPs, contributed to the adoption of INGE’s final resolution, which led to its renewal as ING2 (European Parliament 2022b).

One of the EU’s core values is the rule of law and democracy, uniting the member states in their efforts to face economic and social crises, political challenges, and nationalism (Kováčiková and Blažo 2019). At the end of 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the European Commission published the European Democracy Action Plan, directed at the challenges of digitalization. The Slovak Republic signed up to a number of related initiatives and strategies, among them the Cyber Security Strategy. It also brought its own critical view to initiatives related to strengthening democracy, such as the Pact on Migration or the Green Deal. The mechanism of financial conditionality as a prerequisite for ensuring the application of the rule of law in all EU member states was deemed essential, however (Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí Slovenskej republiky 2021). The fact that the rule of law is based on the principle of mutual trust refers to the responsibility for both its adoption and its implementation. The rule of law is of core significance because, without it as a common value foundation for EU membership, it throws the EU back onto the question whether it is more than a merely economic integration initiative (Máčaj 2021).

No one less than the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, has expressed how the EU can contribute to strengthening integration awareness in Slovakia: “The people need to be at the very centre of all our policies. […] It is only together that we can build our Union of tomorrow” (European Commision 2020c). The Conference on the Future of the Europe held in 2021 and 2022 was an effective tool for doing this. In Slovakia, it was launched on 9 May 2021 and subsequently hosted more than 100 events, including discussions and surveys all around the country, as well as a five-day WeAreEU roadshow that was performed and debated in 25 cities (Conference on the Future of Europe 2022a).

An important message retrieved from this Conference is that only 22 % of interviewed Slovaks favoured a limitation of the EU competences. A huge majority thus favoured the preservation of the status quo or even the extension of those competences (Figure 18), making an important statement in favour of the European Union, given that in Slovakia, as in other countries, relevant political parties exist who advocate Eurosceptic stances. As these parties could also realize, citizens at the base level of Slovak society do trust the EU. And the EU would be well advised not to abuse such trust.

Results of summer 2021 survey as part of the Conference on the Future of Europe. Source: Eurobarometer Winter 2021–2022. Standard Eurobarometer 96.3. European Commission. Brussels. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=81534 (accessed 14 August 2023).

Conclusion

Since its foundation, the Slovak Republic has formulated and pursued the ambition of EU integration as part of its policies to become a member of international or regional organisations and institutions. In 1995, one of the most nationally oriented Slovak governments, led by Vladimír Mečiar, applied for EU membership under the influence of broad civic opinion, which has remained staunchly pro-EU.

As part of the EU’s most numerous enlargement in 2004, Slovakia entered the Schengen area in 2007 and adopted the euro in 2009. This deep integration brought continuous and stable economic growth, despite not reaching that level of GDP per capita, PPP, that the EU15 had reached on average in 2004 when Slovakia accessed to the EU. It is also due to the EU’s common market that Slovakia has preserved its high level of export of goods and has remained an export economy. On the other hand, the decreasing level of FDI in Slovakia, the result of its legal regulations, shows that Slovakia should adhere even more comprehensively to the EU’s common market rules.

The Slovak Republic supports policy fields such as the establishment of a European Public Prosecutor’s Office and future EU enlargement to include the countries of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. We assume that the social and economic benefits from such integration would strengthen even more Slovak citizen’s positive attitude towards the EU as the future model of regional cooperation. But Slovaks are also well aware of the fragility of the European project—as some member states threaten the rule of law, democracy, and human rights. Accordingly, the Slovak government supports the EU’s system of check and balances, including the conditionality between the aforementioned policy fields on the one hand and institutional and financial support on the other.

The domestic political scene in Slovakia has not always been explicitly pro-European, although each government programme pledged commitment to the EU. Implementation in some periods, however, especially between 2012 and 2020, was very limited or even misused by populist rhetoric. As long as Slovak citizens remain committed to EU membership, no government will use anti-EU rhetoric openly or even advocate a withdrawal of Slovak membership. Maintaining such public support for EU membership and the work of EU institutions—something both the domestic civil and political actors and those at the EU level should be very aware of—may be decisive. The Conference on the Future of Europe underlined the importance of the “citizens’ voice” and the need to associate the EU’s future with knowledge and public awareness about its past competences and achievements. It is indeed crucial that the citizens be heard both on the national and European levels. The citizens need to know how the sustainable political and economic development of Slovakia, a small country, has been profiting from its implementation of EU policies, while making good use of the measures and tools it has available to participate in the adoption and implementation of EU policies in a way that this reflects Slovakia’s domestic priorities and strategic positions.

About the authors

Lucia Mokrá is Associate Professor of International and European law at the Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences at Comenius University in Bratislava. She has been a visiting professor at several other universities in Europe and is chairperson of the Trans European Policy Studies Association (TEPSA) board. Her research focuses on human rights, international relations, institutional settings and enforcement in international and European law.

Hana Kováčiková is Associate Professor of International and European law at the Faculty of Law at Comenius University in Bratislava. She is a member of the Jean Monnet Chair and Jean Monnet Network; her professional focus is on European Law, European Competition Law, and Public Procurement.

References

Conference on the Future of Europe. 2022a. “Slovakia.”n.d. https://wayback.archive-it.org/12090/20220918074214/https://futureu.europa.eu/pages/slovakia (accessed 21 August 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Conference on the Future of Europe. 2022b. “Report on the Final Outcome.” May. Brussels: European Commission. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/resources/library/media/20220509RES29121/20220509RES29121.pdf (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Directorate-General NEAR of European Commission 1997–2004. “Commission Opinion on Slovakia’s Application for Membership of the European Union.” 15 July 1997. Brussels. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:51997DC2004 (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Enlargement of the European Union n.d. “Official Position of the European Parliament. Resolutions Adopted by the European Parliament.” Brussels. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargementnew/positionep/resolutionsen.htm and https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/positionep/defaulten.htm (accesssed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Euractiv. 2005. “Slovensko a Európska únia.” 3 January. https://euractiv.sk/section/slovenske-predsednictvo/linksdossier/slovensko-a-europska-unia/ (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Eurobarometer Winter 2021–2022. Standard Eurobarometer 96.3. European Commission. Brussels. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=81534 (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2000. “Regular Report from the Commission on Slovakia’s Progress towards Accession. 8 November. Brussels. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-12/sken1.pdf (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2020a. “Coronavirus Global Response.” n.d. https://global-response.europa.eu/indexen (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2020b. “Single Market Scoreboard. Foreign Direct Investments.” n.d. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/internalmarket/scoreboard/docs/2020/07/integrationmarketopenness/fdien.pdf (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2020c. “Shaping the Conference on the Future of Europe.” 22 January. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip2089 (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2023. “State of Play: New Pact on Migration and Asylum.” Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs231850 (accessed 15 July 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Council 1999. “Helsinki European Council 10 and 11 December 1999. Presidency Conclusions.” n.d. Helsinki. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/hel1en.htm (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Council 2016. “The Priorities of the Slovak Republic Presidency of the Council of the EU.” Council of the European Union, Library blog, 3 June. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/sk/documents-publications/library/library-blog/posts/the-priorities-of-the-slovak-republic-presidency-of-the-council-of-the-eu/ (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

European Council, Council of the European Union. 2022. “EU Sanctions against Russia Explained.” n.d. Brussels. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/restrictive-measures-against-russia-over-ukraine/sanctions-against-russia-explained/ (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

European Parliament. 1998. “Report on Slovakia’s Application for Membership of the European Union, with a View to the Vienna European Council (12 and 13 December 1998) (COM(97)2004 – C4-0376/97).” 19 November. Strasbourg. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-4-1998-0427EN.html (accessed 23 August 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

European Parliament. 2022a. “Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union, Including Disinformation.” Strasbourg. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/inge/home/highlights (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

European Parliament. 2022b. “Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union: Resolution of the European Parliament on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union, Including Disinformation (2020/2268(INI)).” 28 April. Strasbourg. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0064EN.html (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

European Parliament. 2022c. “Renewed Partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood – A New Agenda for the Mediterranean: European Parliament Recommendation of 14 September 2022 to the Commission and the Commission Vice-President/High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on the Renewed Partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood – A New Agenda for the Mediterranean (2022/2007(INI)).” 14 September. Strasbourg. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0318EN.html (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Eurostat Database (online data code: DS-057009). Eurostat. n.d. Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=452727 (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Fórum pre medzinárodnú politiku 2014. “Hodnotiaca správa o 10 rokoch členstva SR v EÚ.” 2 July. Bratislava. http://mepoforum.sk/kniznica/europa-k/slovenska-republika-k/zahranicna-politika-k/hodnotiaca-sprava-o-10-rokoch-clenstva-sr-v-eu/ (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Gyarfášová, O., Mokrá, L. 2019. “Slovakia and the EU: Ready for the Future?” In The Future of Europe: Views from the Capitals, edited by M. Kaeding, S. Aydin-Düzgit, and J. Pollak, 101–4. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Suche in Google Scholar

Kováčiková, H., Blažo, O. 2019. “Rule of Law Assessment: Case Study of Public Procurement.” European Journal of Transformation Studies 7 (2): 221–36.Suche in Google Scholar

Máčaj, A. 2021. “Torpedoing v. Carpet Bombing: Mutual Trust and the Rule of Law.” Slovak Yearbook of European Union Law 1 (1): 9–22.10.54869/syeul.2021.1.268Suche in Google Scholar

Malová, D., E. Láštic, and M. Rybář. 2005. Slovensko a ko nový členský štát EÚ: Výzva z periférie? Bratislava: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.Suche in Google Scholar

Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí Slovenskej republiky. 2021. “Výročná správa o členstve Slovenskej Republiky v Európskej Únii za rok 2020 a aktuálne priority vyplývajúce z pracovného programu Európskej Komisie na rok 2021.” n.d. Bratislava. https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Dynamic/DocumentPreview.aspx?DocID=492230 (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí Slovenskej republiky. 2022. “Strategic Foresight for the Foreign and European Policy of the Slovak Republic Risks and Opportunities for Slovakia in a Transforming World.” n.d. Bratislava. https://www.mzv.sk/en/web/en/diplomacy/documents (accessed 15 July 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Mokrá, L. 2017. “Pre-Accession Programmes as Example of EU Influence to Enlargement and New Member States Development: Case Study Slovakia.” Journal of European Integration History 23 (2): 281–93.10.5771/0947-9511-2017-2-281Suche in Google Scholar

Najšlová, L. 2011. “Slovakia in the East: Pragmatic Follower, Occasional Leader.” Perspectives (19) (2): 101–22.Suche in Google Scholar

National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2001. “Constitutional Act No. 90/2001.” Coll. of Laws on Amendment and Modifications of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic. 23 February. Bratislava. https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2001/90/20020101 (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2011. “Hlasovanie o vyslovení súhlasu s Európskym finančným stabilizačným nástrojom a o vyslovení dôvery vláde SR.” 11 October. Bratislava. https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Default.aspx?sid=schodze/hlasovanie/hlasklub&ID=29245 (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Sekulova, M. 2022. “Slovakia Adopts Package of Legislative Changes to Facilitate Integration of Those Fleeing Ukraine.” European Commission, 17 March. Brussels https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/news/slovakia-adopts-package-legislative-changes-facilitate-integration-those-fleeing-ukraineen#:∼:text=Under%20the%20directive%2C%20temporary%20protection,applying%20to%20the%20nuclear%20family (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

SME. 1995. “Žiadosť o plné členstvo v EÚ predloží SR 26. Júna v Cannes.” SME. 16 June. https://www.sme.sk/c/2124070/ziadost-o-plne-clenstvo-v-eu-predlozi-sr-26-juna-v-cannes.html (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

SME Domov. 2003. “Pozitívne očakávania od vstupu SR do EÚ sa u tretiny občanov znížili.” SME Domov. 27 August. https://domov.sme.sk/c/1076287/pozitivne-ocakavania-od-vstupu-sr-do-eu-sa-u-tretiny-obcanov-znizili.html (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Štatistický úrad SR. 2003. “Výsledky hlasovania oprávnených občanov v referende.” n.d. https://volby.statistics.sk/ref/ref2003/webdata/sk/menu.htm (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

The World Bank Data. n.d. New York. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed 21 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 1998. “Uznesenie Vlády SR 237/1998 k Národnému programu pre prijatie acquis communautaire v Slovenskej republike.” 24 March. Bratislava. https://www.vlada.gov.sk/uznesenia/1998/0324/uz02371998.html (accessed 9 May 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 2002. “Programové vyhlásenie vlády Slovenskej republiky.” n.d. Bratislava. https://www.vlada.gov.sk/data/files/981programove-vyhlasenie-vlady-slovenskej-republiky-od-30-10-1998-do-15-10-2002.pdf?csrt=13251025194494607807 (accessed 14 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 2006. “Programové vyhlásenie vlády Slovenskej republiky.” August. Bratislava. https://www.vlada.gov.sk/data/files/979programove-vyhlasenie-vlady-slovenskej-republiky-od-04-07-2006-do-08-07-2010.pdf?csrt=13251025194494607807 (accessed 23 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 2010. “Občianska zodpovednosť a spolupráca. Programové vyhlásenie vlády Slovenskej republiky na obdobie rokov 2010–2014.” August. Bratislava. https://www.vlada.gov.sk/data/files/18programove-vyhlasenie-2010.pdf?csrt=13251025194494607807 (accessed 23 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 2012. “Programové vyhlásenie vlády Slovenskej republiky.” May. Bratislava. https://www.vlada.gov.sk/data/files/2008programove-vyhlasenie-vlady.pdf?csrt=13251025194494607807 (accessed 23 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 2016. “Programové vyhlásenie vlády Slovenskej republiky.” n.d. Bratislava. https://www.mosr.sk/data/files/33456483programove-vyhlasenie-vlady-slovenskej-republiky.pdf (accessed 23 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. 2021. “Programové vyhlásenie vlády Slovenskej republiky na obdobie rokov 2021–2024.” 28 April Bratislava. https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Dynamic/DocumentPreview.aspx?DocID=494677 (accessed 23 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Vintrová, R. 2004. “The CEE Countries on the Way into the EU – Adjustment Problems: Institutional Adjustment, Real and Nominal Convergence.” Europe-Asia Studies 56 (4): 521–41.10.1080/0966813042000220458Suche in Google Scholar

Zachová, A., and L. Yar. 2021. “Slovensko, Česko a Poľsko napriek sľubom neprispeli na svetový boj s COVID-19.” Euractiv, 9 March. https://euractiv.sk/section/buducnost-eu/news/slovensko-cesko-a-polsko-napriek-slubom-neprispeli-na-svetovy-boj-s-covid-19/ (accessed 23 August 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Zastúpenie na Slovensku. 2022. “18 rokov v EÚ – 72 % Slovákov je spokojných s tým, že Slovensko je súčasťou Európskej únie.” European Commission. 29 April. Brussels. https://slovakia.representation.ec.europa.eu/news/18-rokov-v-eu-72-slovakov-je-spokojnych-s-tym-ze-slovensko-je-sucastou-europskej-unie-2022-04-29sk (accessed 14 August 2023).10.24078/dng.2022.6.128877Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Accession Twenty Years On – Experiences, Expectations and Effects on the European Union

- Accession Twenty Years On – Experiences, Expectations and Effects on the European Union: Introductory Remarks

- Hungary in the European Union – Cooperation, Peacock Dance and Autocracy

- Physically Present but Spiritually Distant: The View of the European Union in Poland

- Romania: A Case of Differentiated Integration into the European Union

- The Future of Slovakia and Its Relation to the European Union: From Adopting to Shaping EU Policies

- The Slovenian Perception of the EU: From Outstanding Pupil to Solid Member

- Article

- “Symphonia”? A New Patriarch Attempts to Redefine Church–State Relations in Serbia

- Critical Essay

- The Age of Skin and the Epoch of an Author: A Eulogy to Dubravka Ugrešić

- Book Reviews

- Iva Vukušić: Serbian Paramilitaries and the Breakup of Yugoslavia. State Connections and Patterns of Violence

- Jacqueline Nieβer: Die Wahrheit der Anderen: Transnationale Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung in Post-Jugoslawien am Beispiel der REKOM Initiative

- Lana Bastašić: Mann im Mond. Erzählungen

- Julianne Funk, Nancy Good and Marie E. Berry: Healing and Peacebuilding after War. Transforming Trauma in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Jasmina Tumbas: “I am Jugoslovenka!” Feminist Performance Politics during and after Yugoslav Socialism

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Accession Twenty Years On – Experiences, Expectations and Effects on the European Union

- Accession Twenty Years On – Experiences, Expectations and Effects on the European Union: Introductory Remarks

- Hungary in the European Union – Cooperation, Peacock Dance and Autocracy

- Physically Present but Spiritually Distant: The View of the European Union in Poland

- Romania: A Case of Differentiated Integration into the European Union

- The Future of Slovakia and Its Relation to the European Union: From Adopting to Shaping EU Policies

- The Slovenian Perception of the EU: From Outstanding Pupil to Solid Member

- Article

- “Symphonia”? A New Patriarch Attempts to Redefine Church–State Relations in Serbia

- Critical Essay

- The Age of Skin and the Epoch of an Author: A Eulogy to Dubravka Ugrešić

- Book Reviews

- Iva Vukušić: Serbian Paramilitaries and the Breakup of Yugoslavia. State Connections and Patterns of Violence

- Jacqueline Nieβer: Die Wahrheit der Anderen: Transnationale Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung in Post-Jugoslawien am Beispiel der REKOM Initiative

- Lana Bastašić: Mann im Mond. Erzählungen

- Julianne Funk, Nancy Good and Marie E. Berry: Healing and Peacebuilding after War. Transforming Trauma in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Jasmina Tumbas: “I am Jugoslovenka!” Feminist Performance Politics during and after Yugoslav Socialism