Abstract

This article focuses on the complex nature of the creative freedom often displayed in acts of digital social writing. Drawing on theoretical contributions from philosophy of language and psychology, the authors argue that even in communication where prescriptive norms are deliberately challenged, creative ways of multilectal and multilingual writing are still shaped by norms and normativity. Mutually recognized norms are part of the common ground that communicators must maintain to secure audience uptake.This is illustrated with three examples, where explicit and implicit negotiations of norms take place in online contexts. In both antagonistic and friendly contexts, we see that successful norm-violating communication involves a collaborative interplay of layers of normativity. Instances of norm shifts and norm challenges of the sort displayed here should not be seen as special cases or fringe phenomena, nor as acts of inherent socio-political significance, but as frequent and highly adaptable moves typical of human language use. Improvised norm shifts manifest a form of creativity that is basic to linguistic communicative competence.

1 Introduction

A great deal of research on digital social practices focuses on the subversive, creative, and transgressive potential afforded by the freedom to write and interact in more than one language, variety, or script. This body of work examines how young people exploit this potential in their multi-faceted linguistic, semiotic, and orthographic practices by flouting spelling rules, contesting standard language ideologies, mocking authorities, and ‘talking back’ to colonial languages (e.g. Androutsopoulos 2011; Cutler 2018; Deumert 2018; Deumert and Lexander 2013; Li Wei et al. 2020; Sebba 2007). New digital technologies have undoubtedly enabled playful, creative, subversive, and norm-breaking ways of using language, allowing people to deploy their linguistic resources innovatively to make sense of themselves and the world around them (e.g. Cutler et al. 2022; Cutler and Røyneland 2018; Deumert 2014; Li Wei et al. 2020; Thurlow and Mroczek 2011; Spilioti 2019; Vandergriff 2010). Several of these studies employ translanguaging theory in their analyses and its understanding of creativity as a boundary transcending, transgressive, and disruptive practice (see Santello 2022: 683). On this approach, translanguaging is viewed as transformative in nature (see Li Wei 2011). According to Li Wei (2018: 23), translanguaging theory emphasizes the creativity of multilingual individuals, understood as “their abilities to push and break boundaries between named languages and between language varieties, and to flout norms of behaviour including linguistic behaviour”. Similar perspectives are echoed by Garcia (2018: 42–43) and Jones (2020: 536), who regard creativity as a fundamentally political act. They argue that creativity can transform power dynamics, challenge dominant narratives, and help reimagine new social identities. According to this line of thinking, creativity is seen as intrinsically connected to criticality, though it seems fair to say that both concepts still remain under-explored dimensions of multilingual practices (see Li Wei 2011: 1223; Kharkhurin 2018: 167).

In this article we pick up this challenge by addressing the complex nature of the creative freedom often displayed in acts of digital social writing. It is evident that even in communication where prescriptive norms are deliberately and meaningfully challenged, such creative ways of writing are still shaped by norms and normativity. Although the linguistic norms of digital writing may be diffuse and negotiated moment by moment, there are evidently constraints on such creative innovations, reflecting communicators’ need to secure audience uptake. This is a general point regarding linguistic communication. To create the unexpected there must be something that is expected. Successful norm-violating communication will always involve an interplay of layers of normativity.

We consider three examples where explicit and implicit negotiations of norms – in particular with regard to the use of non-standard features – take place in online written contexts. We find that creative innovation and norm challenges depend on underlying normative patterns. What kinds of patterns might these be, and what accounts for them? We approach these questions in a spirit of interdisciplinary cross-fertilization, bringing in, first, an account of linguistic communication developed by the philosopher Donald Davidson (Davidson 2001, 2005; Ramberg 1989). While Davidson’s mode of theorizing remains anchored to the tradition of analytic philosophy of language, he is nevertheless a transitional figure, whose approach points beyond that particular disciplinary framework (see Ramberg 2004, 2015). His account of the dynamics of interpretation makes salient basic constraints under which discursive moves are successfully made. Such constraints, however, can take various and interestingly different forms, and generate very different sorts of responses. We discuss this further below (Section 2) and then illustrate our claims with examples (Section 3).

We go on to develop a reading of patterns of norm negotiation and violation found in cases of online written communication as expressions of dynamic and tension-driven projects of assertions of identity, acts of differentiation, and, simultaneously, a search for recognition. To frame this part of the story, we rely on the psychologist Phillipe Rochat’s work (Rochat 2009) on self-consciousness and self-worth. At first blush, Rochat’s work on identity and the self may appear inimical to the traditional sociolinguistic emphasis on groups and group relations. We hope, however, to connect these perspectives by reading Rochat’s account as of an embedded self, and so a source of insight into the relational dynamics that obtain between first-person subjectivities and the living social practices of which they form constituent parts. Thus, there is no implicit denial here of the significance of the social, but an attempt to illuminate further the micro-dynamics through which agents socially perform and become the particular selves that they are.

We conclude by suggesting that norm shifts and norm challenges should not be seen as special cases or fringe phenomena, nor as acts of inherent socio-political significance. Rather, such moves are, we suggest, typical of human language use, manifesting a form of creativity that is basic to linguistic communicative competence.

2 Theoretical reflections

2.1 Norm games and common ground

Donald Davidson’s approach to linguistic communication (Davidson 2001: Ch 9) brings into view certain background conditions for successful communication, conditions that pertain to the kinds of moves communicators make in what we call linguistic norm games. Aligning with philosophers like Wittgenstein, Austin, and Grice, Davidson breaks with the traditional philosophical approach to language as primarily a system of propositional representation, attending rather to features of the interactive dynamics of any social practice that counts as linguistic. This shift brings into focus communicators’ sensitivity to different layers of normativity in the uptake of utterances and so provides an illuminating perspective on various kinds of breaches of standards, norms, and expectations that may be deployed in linguistic communication. Hence, while Davidson’s explicit explanatory targets remain highly general concepts (linguistic competence, interpretation, agency, truth), his work, as we hope to show, nevertheless yields insights with empirical applicability within more narrowly circumscribed theoretical contexts.

Davidson highlights the fact that language use is fundamentally a game of social cooperation. The critical philosophical point here is that this remains true no matter what specific communicative aims are in play, and also when interlocutors’ purposes are at loggerheads and the setting adversarial. Our particular concern is with the range of ways in which this fundamental cooperative dimension of language, highlighted by Davidson, both constrains and enables agents in their communicative choices and strategies. It does this in a variety of ways, the specifics of which will depend on the means and objectives of the particular communicative situation. And so, we expect, this dynamic will be traceable, too, in the ways that communicators creatively exploit the resources available in digital social writing.

As we interpret each other we relate to a shared world, exchange information about it, and generally coordinate our dealings with it. However, we also differentiate – we articulate our respective perspectives on this shared world. As subjects engaged in mutual linguistic interpretation strive to make sense of each other’s utterances, we attribute not only specific illocutionary intentions, but also a wide range of beliefs, desires, evaluations, and perceptions in which specific utterances may be meaningfully embedded. Importantly, as Davidson stresses, in order to be able to locate divergences in our view of things, and to disagree about specifics, we must as communicators always converge on a great deal. Only against a background of shared understanding and assumptions can fine-grained divergence be articulated at all. As Davidson makes this point in his discussion of his account of linguistic interpretation:

What justifies the procedure is the fact that disagreement and agreement alike are intelligible only against a background of massive agreement. Applied to language, this principle reads: the more sentences we conspire to accept or reject (whether or not through a medium of interpretation), the better we understand the rest, whether or not we agree about them (Davidson 2001: 137).

This point is expressed methodologically as a non-negotiable assumption on the part of linguistic agents regarding the basic reasonableness of fellow speakers (see Ramberg 1999). In line with ethnographic and anthropological traditions highlighting the centrality of norms in accounts of human conduct, we place the emphasis here on shared norm sensitivity. The claim, then, is that successful interpretation is a form of collaboration that presupposes shared norm sensitivity – a commonality of oughts and don’ts.[1] This perspective entails that norms are not treated simply as descriptive regularities, or theoretical constructs distilled by investigators from surveys of linguistic behavior (see Pitzl 2022). Rather, agents’ commitments to norms are irreducible and ineliminable from the account, since it is by virtue of shared sensitivity to norms of behavior that language users are able to interpret each other as linguistic agents at all. This commonality we may think of as a common ground, constituted by a convergence of expectations that are not only factual but also normative in character. Such expectations pertain to how agents may reasonably respond to events and situations and navigate their way through them. This common ground is not fixed (neither temporally nor in extension), it is fuzzy-bordered, and it is generally implicit. It is typically thematized locally when communication breaks down, when specific expectations are thwarted – when we are surprised by what happens, or, in particular, by what someone does or says. As we will see, it may also shift through conversation and particular aspects of it may be brought into play explicitly, in order to secure understanding or to challenge it.

Another key feature of Davidson’s approach is that it dispenses with the idea of a shared linguistic structure as a basic explanatory notion in the account of linguistic competence (Davidson 2005: 96). In effect, Davidson reverses the traditional explanatory approach, by accounting for the possibility of common linguistic understanding by assuming a shared world. This means that norm-breaking (rule-breaking or convention-breaking) linguistic behavior presents no particular explanatory puzzle, in the way it might do for an account of linguistic uptake that is based on the idea of shared rules or conventions. Rather, the common ground that allows uptake may well be dynamically shifted through communication as expectations are adjusted and calibrated. Accordingly, such ground-shifting moves (small and large) can be assigned the typical and central role that is often reflected in empirically oriented studies of actual linguistic behavior. At the same time, a clear constraint is placed on norm-flouting behavior; to secure uptake, users who aim to be understood must always be able to keep in place a sufficiently rich common ground of understanding with their interlocutors. This sometimes requires measures ensuring an intended interlocutor’s access to relevant aspects of a communicative situation (contextualization cues), whether explicit or implicit; empirical or normative. This is true irrespective of whether the intention behind the move is friendly or hostile, converging or diverging, ironic or serious. What this means, in turn, is that communicative creativity manifesting in divergence from rules and conventions is constrained by an ability to convey the point of the divergence. Succinctly put, successful infringement of normative expectations depends on a mutually accessible expectation replacement – what we will call a normative shift: a specific move in a context that changes the salience of norms in play. Thus we agree with Pitzl (2022) when she remarks that the link between creativity and norms is very close, but diverge when she supports this with the claim that “creativity is in many ways the very opposite of normativity” (Pitzl 2022: 125). As we see it, normativity is rather the fuel of linguistic creativity, which is typically displayed as a surprising move within a complex context of layered normative expectations.

This approach to creativity chimes with pivotal contributions to sociolinguists, such as the work of Sacks on conversation analysis (e.g. 1995), Gumperz on contextualization conventions (e.g. 1982), and, in particular, with the holistic approach central to Hymes’s ethnography of communication (e.g. 1962). Davidson’s more abstract account stresses the collaborative dimension in any linguistic communication, and the concomitant assumptions of shared practices, in a very general form. How communicators actually secure and modify common ground in successful acts of meaning creation, however, is left largely unexplored. The development of sociolinguistic theory over the last five decades demonstrates that exactly this question is extremely fruitful. It is in this spirit that we canvas our examples. They illustrate two basic aspects of the approach we take to successful normative shifts. First, one would expect that normative shifts are unremarkable and integrated occurrences in a great deal of ordinary conversation, and the ability to perform and respond to them a very basic part of pragmatic linguistic competence. It is worth noting that this makes it difficult to rely on norm deviations to draw a principled line between creative and conventional linguistic behavior. Some such shifts might stand out as innovative and creative on the part of the language user, while others will appear more unremarkable, given their context. Secondly, creative norm shifts have no intrinsic connection with what is socially or politically transgressive. On this point we align with Marco Santello (Santello 2022). Santello deploys Michel de Certeau’s groundbreaking work on everyday life (Certeau 1984) to retrieve the idea of creativity at work in ordinary ‘tactical’ speech. This places in question the tempting thought that linguistic creativity has an inherent transgressive, critical, and transformative function (e.g. Jones 2020; Li Wei 2018; Li Wei et al. 2020). We do not deny that it can have this, but, qua creative, it need not.

2.2 Creativity and conflict

Creativity is understood, theorized, and operationalized quite differently by various language scholars. Some emphasize novelty and utility, or our ability to bring a sense of ‘newness into the world’ (Bhabha 1994, after Deumert 2018: 10), while others focus on aesthetics and authenticity (Kharkhurin 2018: 167). Without venturing a definition, we rely here on an understanding of creativity that ties it closely to a certain kind of improvisational ability, that is, an ability to achieve both uptake and further perlocutionary aims by exploiting resources afforded by the communicative situation in ways not (yet) conventionalized. Creativity, then, as we think of it here, will be a matter of degree. Moreover, it may manifest both as an individual achievement in a particular move, such as in a successful norm-shift performance, or it may be conceived as a joint achievement, a trait of a certain kind of practice, where the instability and transience of the value of the signifiers employed – the how-it’s-done of the communicative practice – is built into the constitutive goals of an ongoing inter-subjective exchange.

In our first example (3.1) norm shifts are undertaken as moves in a tense and conflict-driven exchange between interlocutors with no prior relationship to draw on. They struggle for authority and legitimacy in a complex exchange that is clearly antagonistic, with participants both substantively and conceptually at odds. We will see that rules and conventions are constantly at issue. Meaning-determining conventions are challenged and problematized, as are pragmatic norms guiding up-take, as well as more broadly social norms that bear on the significance of what is being said. At the same time, though, up until the final move, the exchange maintains a collaborative dimension. In line with this, we suggest that much creativity displayed in antagonistic contexts can be traced to the double-sidedness of the communicative situation. On the one hand, an antagonistic communicative move may express an effort to achieve a tactical or strategic repositioning by performing a norm-shift aimed to win ground on the issue under dispute. At the same time, though, it must reflect the constraint imposed by the need to maintain sufficient commonality of understanding, if that shift is to have a chance at hitting home.

In conflict situations, such as that in (3.1), creative norm-shifting moves may express resistance toward particular communicative hierarchies that are invoked or assumed in the encounter. Norm shifts may be performed as direct or indirect challenges to the epistemic and social statuses dispensed by these hierarchies. Yet, to remain communicatively effective, these moves must connect with the antagonistic interlocutor’s norm system in a way that will move the antagonist – they must hook in, as we might say. The challenge posed by this duality is evident where antagonistic interlocutors are simultaneously struggling to move each other while also trying to resist each other’s efforts to hook in – and this challenge may give rise to improvised norm-shifting moves. When the statuses that are challenged and negotiated are clearly connected to political struggles (as in our example 3.1), the creativity displayed may fit neatly with a sociolinguistic perspective that approaches discursive normative struggles as expressive of social conflict and injustice.

2.3 Self-expression, recognition, belonging

Our next examples (3.2 and 3.3), by contrast, involve interlocutors in friendly, well-aligned communication. Here we also find norm violations and norm shifts of different kinds, some of which display significant creativity. Clearly, though, that creative impulse is not rooted in antagonism, nor in conflicting communicative aims between the interlocutors. Yet, the norm games on display here are, we take it, representative of commonplace communicative behavior. What drives creative norm-shift moves in this sort of play? We will argue that also in such instances creativity may be tied to norm shifts that negotiate communicative goals in tension.

To substantiate this claim, we turn to the psychologist Philippe Rochat, whose work Others in Mind: Social Origins of Self-Consciousness (2009) offers an interpretation of the significance of social recognition for beings that are self-aware. Self-awareness of the kind that Rochat is concerned with is a conceptual capacity, in the sense that it is awareness of an evaluative, narrative kind. It is the kind of self-awareness that common linguistic interaction typically displays and requires, a capacity that goes beyond mere communication or even self-recognition of a sort that a range of other species may well be capable of. Rochat’s fundamental concern is to show that and how our sociality is constitutive of the distinctively human kind of evaluative and projective self-awareness. As he says, “[c]oping with the basic need to be with others and fearing rejection by them are constitutive of the context in which we, as a species, evolved self-consciousness. All we do, as a result, is with others in mind.” (Rochat 2009: 213–214). In our species, this constitutive relation has evolved into a fundamentally normative one. Following this lead, we might say that human linguistic agency inevitably brings in its wake moral evaluation and self-evaluation – not just of this or that action or situation, but of the position that I, the communicative agent, occupy, of what kind of a self it is that I am. And insofar as linguistic interaction is the province of self-aware and sense-making agents, then it will also be a domain for struggles of self-expression and for recognition from the community that ultimately funds any sense of self-worth available to an individual agent. For Rochat, this point has a fundamental existential significance for creatures like us:

We strive to get recognition from others, but ultimately it is to be confirmed in the value we ascribe to and aspire for ourselves. This is how we fulfill the sense that we exist and, that we are not psychologically dead, that we have a self that has coherence, meaning, and, more importantly, that has some worth in itself. It is the expression of a deep abstract and existential need, a transcendental and moral expression (in the sense of value system) of self-consciousness (Rochat 2009: 226).

For present purposes a key take-away from these considerations is that human communication is always also a project of self-articulation. It goes without saying that the extent to which this existential dimension of communicative life is salient will vary immensely with communicative context. However, it is exactly a shared feature of our cases here that they provide settings where this dimension is tangible, though in sharply contrasting ways. In the first example (3.1), the existential dimension is explicitly at issue, framed in antagonistic terms and in a socio-political vocabulary. In the other two examples (3.2 and 3.3), the articulation of self, of social differentiation and belonging, is collaborative and mutually affirmative. In both settings, creativity is a central resource.

3 Conflict and collaboration: three examples

3.1 The sociolinguistic context

In the following examples, we scale down and zoom in on three examples drawn from digital (social) writing on YouTube and Snapchat within a Norwegian context. To situate these, we give a brief outline of the ecology of language and the sociolinguistic situation in Norway. Historically and today, linguistic diversity in both spoken and written forms has been extensive in Norway, and has been associated with principles of egalitarianism and democracy (Røyneland and Lanza 2023). There are two standard written norms of Norwegian, Bokmål and Nynorsk, that in principle have equal status. All schoolchildren, with certain clearly defined exceptions, must learn both written standards, but they may choose one as their primary standard (for details about the Norwegian Language situation see Jahr 2014). Only around 13 % of pupils, mostly in Western Norway, have Nynorsk as their primary written norm. The majority written standard, Bokmål, is much more commonly used both in public and private discourse, online as well as offline, and is generally more visible in the linguistic landscape. Consequently, people are in general much more exposed to Bokmål than to Nynorsk. While most Nynorsk users are also proficient in Bokmål, the reverse is often not the case (e.g. Sønnesyn 2023).

Unlike in most other European countries, dialects are widely used also within formal contexts and by people in all social strata (e.g. Sandøy 2011), and dialect diversity is regarded as a hallmark of equality and democratic ideals. Retaining one’s dialect is evaluated very positively, whereas mixing or switching is commonly perceived as a signal of inauthenticity (Røyneland and Lanza 2023: 345). The urban speech of the capital, Oslo, has relatively high prestige and arguably shares some of the properties of a spoken standard. Nevertheless, the spoken standard language ideology in Norway is relatively weak: there is no consensual, unequivocal ‘best and most correct spoken variety’ of Norwegian that everyone is required to acquire (e.g. Røyneland and Jensen 2020; Sandøy 2011).

Traditionally, Norway has had several regional minority languages, all which are now recognized either as official languages (Sámi) or as national minority languages (e.g. Kven). Moreover, globalization has introduced a number of new minority languages and increased the use of English (for more details, see Røyneland and Lanza 2023). In addition, new multiethnolectal speech styles have emerged in multilingual, multicultural urban areas, particularly in the capital and other major cities characterized by a high density of youth from multilingual backgrounds (e.g. Nortier and Svendsen 2015).

Taken together, this suggests that youth in Norway have a potentially large linguistic repertoire at their disposal for their digital (social) writing. Non-standard writing that incorporates dialect features, elements from other languages (particularly English), multiethnolectal traits, and features typical of digitally mediated communication (hereafter referred to as DMC features) – such as acronyms, letter and punctuation reduplication, omitted punctuation, all caps, and emoticons – is very common in digital writing across the country (e.g. Røyneland and Vangsnes 2020; Vinichenko forthc.).

3.2 Norm negotiation: authority and legitimacy

The first example we want to consider is a lengthy online multilectal and multilingual written exchange between three individuals (Person 1, 2, and 3) with highly conflicting views commenting on a YouTube video by the Norwegian-Peruvian-Chilean rapper Pumba (Excerpt 1–9). We present several turns, in order to illustrate the shifts performed as the conflict evolves. The video addresses the legitimacy of multiple belongings and identities, as well as the conditions of entitlement to claim a particular identity. An extensive analysis and discussion of the video and the subsequent comments may be found in Røyneland (2018). All the comments, 666 by January 2017, were downloaded using the scraping tool YouTube Scrape.[2] User anonymity is protected by omitting their online nicknames, slightly altering quotations, and excluding some of the most offensive or racist language (these are marked with a bracketed description in the examples). Hence, the quotations are not completely identical with the downloaded material, but nothing has been added (following the Association of Internet Researchers 2019 ethical guidelines, aoir.org/ethics). For the purposes of this article, we will focus on a handful of comments, particularly highlighting a heated discussion between three individuals in which knowledge of the standard written norm serves as a proxy for authority, legitimacy, and identity (also discussed in Røyneland 2018).

The discussion is kicked off by Person 1 with a comment on a phrase used by Pumba in the rap video: “Man kan hustle uten å miste armen” [‘You can hustle without losing your arm’] (Excerpt 1). This line is apparently (mis)understood by Person 1 as evidence that immigrants are lazy and do not want to work. Several commenters respond, emphasizing that the line should not be taken literally, but rather as a metaphor suggesting that no one should have to work themselves to the bone to make a living. This is contrasted with situations in some other countries outside Norway, where widespread and abject poverty means that many people will exhaust themselves just to secure survival.

In Excerpt 2 we see Person 2 reacting to the explicitly racist utterance made by Person 1 in Excerpt 1. Person 2 asks whether Person 1 is from northern Norway and then challenges them directly, asking if they would like to meet in person. In Excerpt 3, Person 1 responds in an aggressive, threatening, and racist manner by calling Person 2 a “monkey” – a term with an established racist and discriminatory connotation. Additionally, Person 1 characterizes and labels immigrants with highly derogatory language, reflecting a hostile and harmful attitude. Person 1’s account has since been terminated and no longer appears on YouTube.

In the exchange between Person 1 and 2 (Excerpt 1–3) both individuals flout standard written norms by using a number of northern Norwegian dialect features (bolded) and lexical items from English (italicized). Person 2 also uses DMC-features such as; contraction, smileys, lack of standard punctuation and use of lowercase where we would expect uppercase according to the standard norm.

Example 3.1: Discussion about authenticity and belonging on YouTube

Person 1: “Man kan hustle uten å miste armen”. Jævla idiot! Om det e sånne holdninge de der førbanna [racist noun with northern Norwegian dialect plural inflection] kommer til landet med så e det faen ikke rart at det bor en liten rasist i de fleste av oss.

[“You can hustle without losing your arm”. Damned idiot! If that’s the kind of attitude those damn [racist noun with northern Norwegian dialect plural inflection] bring to the country, it’s no wonder there’s a little racist living inside most of us.]

Person 2: Du og rasisten i dæ kan sug [offensive noun] min :) det kan forsåvidt landet ditt også :) Internet thug [offensive noun] …du e norlending? avtale møte bitch? (2014)

[You and the racist in you can suck my [offensive noun] :) the same goes for your country, by the way :) Internet thug [offensive noun] … you’re a northerner? schedule a meeting bitch?]

Person 1: […] Æ e internet thug ja, det ekke æ som sett å true med juling over internett. Ha litt selvinnsikt, eller blir det for komplisert for ei apa? Og nei, æ hold mæ unna utlendinga, eneste dokker duge til e å lage junkfood og [offensive language omitted]. (2014)

[Oh so I’m an internet thug, it’s not me who threatens beatings over the internet. Have some self-insight, or would that be too complicated for a monkey? And no, I keep my distance from foreigners, the only thing you’re good for is to make junk food and [offensive language omitted].

In this exchange, the dialect features used by both individuals are those most commonly used in digital social dialect writing among adolescents across the country (see Vinichenko 2025), namely personal pronouns, noun and verb inflection and negation.

Dialect features in Excerpt 1–3

|

Dialect |

Standard, Bokmål |

English |

|

|

Pronoun, 1. pers sg. subj. |

æ |

jeg |

I |

|

Pronoun, 3. pers. pl. subj. |

dokker |

dere |

you |

|

Pronoun, 1. pers. sg. obj. |

mæ |

meg |

me |

|

Pronoun, 2. pers. sg. obj. |

dæ |

deg |

you |

|

Adjective |

førbann-a |

forbann-a/-ede |

bloody |

|

Negation/contraction |

ekke |

er ikke |

is not |

|

Noun, indef. pl. |

holdning-e |

holdning-er |

attitudes |

|

Noun, indef. pl. |

utlenning-a |

utlenning-er |

foreigners |

|

Noun, indef. sg. |

ap-a |

ap-e |

monkey |

|

Verb, present tense |

e |

e-r |

is |

|

Verb, inf. |

sug |

sug-e |

suck |

|

Verb, present tense |

dug-e |

dug-er |

be good for |

|

Verb, present tense |

hold |

hold-er |

keeps |

|

Verb, present tense |

sett |

sitt-er |

sits |

We note that both racist and anti-racist stances are voiced using dialect features and other non-standard features. Hence, in this exchange these features do not seem to index any salient political conviction or ideological stance. Nor is the fact that dialect features are used directly commented upon, though when Person 2 identifies Person 1 as someone from Northern Norway this is presumably on the basis of the dialect features used, since no other information to that end is available.

At this point, a third person enters the discussion, taking a clear stance against Person 1’s racist and damaging utterances (Excerpt 4). In contrast to the two previous discussants, Person 3 does not use any local dialect features; instead, they adhere much more closely to the standard written norm, albeit with a few DMC-features, as well as occasional misspellings (underlined), and lexical items and phrases from English (italicized).

Example 3.1 cont.

Person 3: hhahahahha d er kansje noe av det mest tilbakestående jeg har lest i hele mitt liv, du hadde kansje blitt tatt litt mere serriøst om du faktisk ga mening i det du sa, kjenner en [offensive noun] som har bod i norge [få år] som gir mer mening en hva du akkurat skrev. jævla norske fjell ape. (2014)

[hhahahahha this is maybe some of the most retarded stuff I have read in my whole life, you would maybe have been taken a bit more seriously if you actually gave meaning to what you’re saying, know a [offensive noun] who has lived in norway [only a few] years who gives more meaning than what you just wrote. bloody Norwegian mountain ape.]

In the earlier exchange, the status of dialect features was not at issue, and they were neither mobilized nor challenged in the antagonistic confrontation. Their pragmatic acceptability remains part of the common ground of the confrontation. However, with the intervention of Person 3, this shared assumption is challenged, and the ground is shifted. From this point on, as mastery of the prescriptive written standard becomes a crucial theme of the ensuing metalinguistic and metapragmatic discussion, Person 1 stops using any dialect features, adhering instead to the prescriptive norm with correct orthography. The extent to which one is able to write Norwegian correctly now serves as an index of how much authority one has, and therefore, how legitimate one’s views are, on the question of Norwegianess. With this move, Person 3 also problematizes the understanding and value of the idea of Norwegianness in play so far. On the one hand, Person 3 claims authority by asserting a kind of competence that, presumably, anyone who values Norwegianness should respect. Person 3 thereby lands a normative hook, keeping Person 1 in the game. On the other hand, Person 3 claims that they know someone with an immigrant background who has lived in Norway for only a few years and still makes more sense (“gives more meaning”) than Person 1 does. This in effect challenges the idea that simply being of Norwegian extraction gives any kind of authority in itself. The point is reinforced when Person 3 picks up on the derogatory use of “monkey” previously employed by Person 1 and turns it against them by calling Person 1 a “bloody Norwegian mountain monkey”. This term “[fjellape]” also has an established offensive derogatory connotation, suggesting here that Person 1’s variety of Norwegianness is that of an ignorant individual from the rural periphery, consequently one lacking insight and authority. By shifting the norms of the contest in these ways, Person 3 introduces evaluative axes that challenge the ground of the initial exchange, presumably aiming to dismiss and delegitimize Person 1 in terms that Person 1 cannot feel entitled to ignore or dismiss out of hand. That this norm shift is at least partially successful is apparent from Person 1’s response. The devaluation of dialect features (not DMC-features) through the association with delegitimizing geographical (social) placement is picked up through Person 1’s immediate shift to the standard norm.

In their response (Excerpt 5) to this intervention, Person 1 counters by questioning Person 3’s ability to use Norwegian correctly and express themselves coherently, effectively attempting to dismiss the entire discussion by turning the norms put in play by Person 3 back on them. To this rebuttal, Person 3 (Excerpt 6) replies that Person 1’s lack of comprehension must depend either on the fact that Person 1 actually does not know Norwegian or, alternatively, that Person 1 is completely “retarded”. The excerpt contains several misspellings (underlined), English features (italicised), and several DMC-features (d for standard “det” [‘it/that’-PRO], emoji, lower case, lack of punctuation according to standard rules).

Example 3.1 cont.

Person 1: Det du skrev gav lite mening. “en [racist noun] som har bod i norge i [få] år som gir mer mening…” Hvordan kan en person gi mening? Nytter ikke å “diskutere” om du ikke klarer å formulere deg på en forståelig måte.

[What you wrote makes little sense. “A [racist noun] who has lived in Norway for [a few] years gives more meaning…” How can a person give meaning? It’s pointless to “discuss” if you can’t express yourself in an understandable manner.]

Person 3: om du virkelig ikke skjønnte hva jeg skrev så er d 2 alternativer 1: du kan ikke norsk 2: du er helt retardert – whatever makes u happy :). en normann som klager over utlendinger men kan ikke skrive sitt eget språk engang var hele “meningen” i kommentaren, jeeze folk må ha allt med t-skje. (2014)

[If you really didn’t understand what I wrote then there are 2 alternatives 1: you don’t know Norwegian 2: you’re totally retarded – whatever makes u happy :) a Norwegian who complains about foreigners but who cannot even write his own language was the entire “message” of the comment, jeeze people must have everything with a t-spoon.]

In their response (Excerpt 7), Person 1 begins by pointing out all the misspellings made by Person 3 by presenting them in their alleged correct form followed by an asterisk – presumably to indicate that they were written incorrectly by Person 3. Person 1 again endorses mastery of written Norwegian as a norm for legitimacy and authority, introduced by Person 3, and relies on it to undermine Person 3’s claim to superiority and authority over what is properly Norwegian. Asserting that Person 3 is the only one with language difficulties, Person 1 points both to (presumed) Norwegian misspellings and to English ones (erroneously correcting the Norwegian spelling retardert to the English spelling retarded). Interestingly, Person 1 does not react to the use of English words and phrases per se, nor to the use of DMC-features. Hence, the use of English and DMC-features does not seem to be perceived as discrediting or “incorrect” in this context.

Example 3.1 cont.

Person 1: Skjønte* retarded* nordmann* alt* teskei* Hvilken nordmann er det som ikke kan skrive sitt eget språk her? Den eneste med språkvansker her er deg. […] Jeg kan norsk, men det kan tydeligvis ikke du. (2014)

Understood* retarded* Norwegian* everything* teaspoon* What kind of Norwegian doesn’t know how to write his own language? The only one with language difficulties is you. […] I know Norwegian, but you obviously don’t.]

In Excerpt 8 we see Person 3 reacting strongly to this, insisting on their knowledge of Norwegian while attempting to delegitimize and undermine Person 1’s authority by, again, calling them a “mountain ape”. Here, though, Person 3 performs a further shift; at stake now is not who best displays mastery of the standard norm, but how (by whom) the standard is set – whose language gets to be considered Norwegian. The legitimacy of the claim to be a competent user is now vindicated through reference to Person 3’s background as a de facto fully qualified competent user – born in Norway, raised in Norway, a habitual speaker of Norwegian at home and with friends.

Of particular interest in this turn is the final shift performed by Person 3, who concludes this response with an all caps swear phrase in Croatian. The context gives no grounds for assuming that this expression is a part of Person 1’s repertoire, so presumably Person 3 had no expectation of being understood in a conventional sense. And of course the expression might be taken simply as an expression of frustration. However, its communicative impact may also be more articulate, precisely because of the shared knowledge that with this move Person 3 breaks with standard norms for uptake. The move might be both intended and received as an assertion of a kind of power, expressing a claimed superiority of Person 3’s multilingual repertoire and international affiliation in contrast to Person 1’s allegedly limited (local and peripheral), ignorant, racist and nationalist worldview. The move might be read as an insulting withdrawal – a shift in audience orientation, repositioning Person 1 as an object of derision in the eyes of an intended new audience, rather than as an interlocutor: “I am not talking to you anymore, because you are not worth the effort. (But I am letting you know).” Is this the intention? Is it successful? We cannot know. But as a distinct norm-shifting move it breaks the norms of the game being played up until that point, and through this shift also appears to carry communicative significance. Notably, the move is not taken up. After another round of insults, where Person 3 insists on their Norwegian competence by referring to their school grades, Person 1, in return, pseudo-apologetically restricts themselves to remarking on Norwegian orthography, rather than knowledge of Norwegian per se, but continues to emphasize that correct spelling and orthography is not something Person 3 demonstrates. Person 1 then ends the exchange with what may be interpreted as a condescending smiley (Excerpt 9).

Example 3.1 cont.

Person 3: hør her din [offensive language], <jeg kan ikke norsk? wow du er virkelig stokk dum…hvordan i helvete kan jeg ikke norsk når jeg er født i norge og har bod her [i hele mitt liv] snakker norsk hjemme og blandt vennner så ikke snakk piss jævla fjell ape. […] IDI U PICKU MATRINU [Croatian with misspellings]! (2014)

[Listen up you [offensive language], <I don’t know Norwegian? Wow you’re really thick as a brick… how the hell do I not know Norwegian when I was born in Norway and have lived here [my whole life] speak Norwegian at home and among friends so don’t talk shit bloody mountain ape GO FUCK YOURSELF !]

Person 1: Beklager, norsk RETTSKRIVNING da. Ser ikke ut som det er en av dine sterke sider :) (2014)

[Sorry, Norwegian ORTHOGRAPHY. Does not seem to be one of your strong sides :)]

To sum up the points we draw from this antagonistic exchange: We find Person 1 initially using several dialect features but then changing this practice once it is challenged (and insulted as the behavior of a “mountain monkey”). Switching to the standard written norm, Person 1 uses only DMC-features that do not situate them geographically. In our terms, this change appears as a response to a successfully executed norm shift performed by Person 3. Person 3, in effect, transposes the confrontation over racism between Person 1 and Person 2 into a context where the authority of the participants is linked to their mastery of prescriptive written norms. Each now attempts to delegitimize their opponent by pointing out flaws (typos, etc.), indirectly articulating the following chain of claims: “You cannot write properly”, hence “You are not Norwegian”, and so “Your opinions have no authority and are not legitimate”. The antagonists jointly proceed on the assumption (the common ground) that both their degree and their variety of Norwegianness is being challenged, and that knowing how to write Norwegian is important and central to claiming an authoritative Norwegian identity. They also appear to concur that employing dialect features does not constitute correct Norwegian. However, they seem to disagree on exactly what constitutes writing Norwegian correctly – and on how to write acceptably on a social digital platform both in terms of content and form. It is noteworthy that these norm shifts, whether pragmatically effective or not, are not particularly creative linguistically. On the contrary, we observe in this exchange a striking example of the resilience of prescriptive norms. It illustrates how these norms can be invoked both to assert authority and to undermine others by highlighting norm violations. This underscores the point that prescriptive norms are often highly resilient, with acts of norm violation being correspondingly conditional, superficial, or contextually circumscribed. Additionally, it demonstrates the kind of norm-layering that norm shifts utilize. In dialect writing, the flouting of standard prescriptive norms depends on the operational effectiveness of underlying norms that facilitate their acceptance, as presumably was the case in the initial exchange between Person 1 and Person 2, their mutual hostility notwithstanding. Yet, dialect writing is fragile. It may indeed serve various pragmatic purposes, even of securing authority and position, in circumscribed and often geographically specific contexts. As Example 3.1 illustrates, however, this status-conferring position is unsafe, and subject to displacement by the force of norms recognized and underwritten nationally, and often through institutional authority. Command of such norms is linked to authority, and deviation to ignorance. In the exchange above, such ignorance indexes flaws of identity.

3.3 Creativity, normativity, affirmation

The next two examples we consider are much shorter, and both taken from a corpus of a total of 3743 donated non-sensitive chat messages from Northern, Western and Central Eastern Norway.[3] In total, 257 9th-graders from these three regions contributed authentic chat messages (mostly Snapchat) with their classmates (for a description of the procedure and ethical considerations, see Lunde and Røyneland 2023). A detailed analysis of their online practices by Vinichenko (forthc.) reveals that non-standard writing is common in all three regions. She finds that messages containing non-standard features are widespread in the West (74.5 %), almost equally widespread in the North (71.3 %) and slightly less so in the Central East (57%). However, the patterns of non-standard usage are qualitatively different in the three regions. In the Northern and Western regions where the structural distance between the regional spoken dialect and the local written standard is most pronounced, the use of dialectal features is high and accounts for most of the non-standard writing. In the Central Eastern region more general DMC-features are used and very few dialectal features – probably because the actual structural and perceived difference between their spoken language and the majority written standard Bokmål is fairly small. This results in fewer opportunities for including dialectal elements in their writing. This may suggest, according to Vinichenko (forthc.), a compensatory mechanism, where participants without a lot of dialectal resources at hand may resort to alternative markers of informality, such as DMC-features, in their digital writing.

The first of these two examples (3.2) illustrates a strikingly creative double norm-shift. In this instance, presumably authoritative written standards are invoked in a sudden flouting of local norms, but this move is conducted so as to invite convergence and reaffirmation of common local practice – a playful, we-affirming move. The second example attests to the normality of what we consider non-standard language use, that is, use that deviates from recognized prescriptive norms. There is no transgression or criticality to be seen. Yet the exchange does display a form of creativity, both in specific turns, and also in the creative combination of multilingual, multilectal, and DMC-features that characterizes it. At the same time the creativity displayed here is in a sense par for the course – an expected feature of a reasonably common-place kind of exchange. What we do see in this case is a smooth, collaborative participation in a shared and highly refined discursive practice. As this practice is maintained and developed, it can also be read, with Rochat, as an ongoing affirmation of identity and of belonging, in a game of mutual recognition. Perhaps, then, the kind of creativity displayed in 3.3 is better conceived as a collaborative intersubjective achievement, realized in the nature of the practice itself.

3.3.1 Creative shift to the majority standard

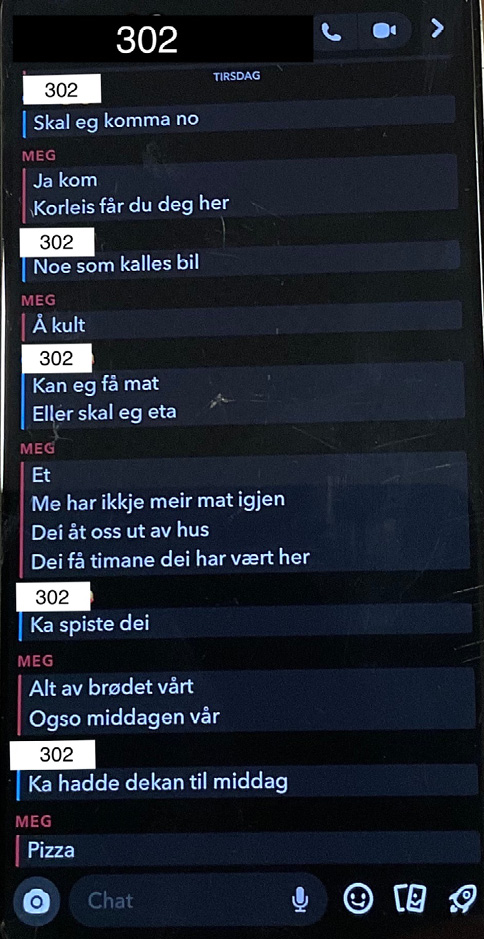

In example (3.2) we see an exchange between two 15-year-old girls from the Western region in Norway. Most of the exchange is written in standard Nynorsk with a few local dialect features (marked in bold: wh-word ka, (Nynorsk kva [‘what’] and the 2nd person plural pronoun dekan, (Nynorsk dykk/dokker [‘you’]). This seems to be the normal, unmarked choice in their communication. In the fourth line (marked in grey) an interesting jocular and creative norm shift to the majority written standard Bokmål occurs. When asked how she will get there, 302 answers “with something that is called car” (the Bokmål features are marked with italics: Noe (standard Nynorsk Noko [‘something’]) and kalles, (Nynorsk vert kalla [‘is called’], the two other features in the message, som [‘that’] and bil [‘car’] are isomorphic in the two standard varieties). The norm-shift made here is clearly intended to bolster the humorous intent of the ironically implied presumption that the recipient is not familiar with automobiles. It is also clear from the uptake from 342: Å kult [‘Oh cool’], that the friendly intent is received:

Example 3.2: Chat between two girls age 15 (302 and 342) from Western Norway

|

|

302 Skal eg komma no 342 Ja kom Korleis får du deg her 302 Noe som kalles bil 342 Å kult 302 Kan eg få mat Eller skal eg eta 342 Et Me har ikkje meir mat igjen Dei åt oss ut av hus Dei få timande dei har vært her 302 Ka spiste dei 342 Alt av brødet vårt Ogso middagen vår 302 Ka hadde dekan til middag 342 Pizza |

302 Shall I come now 342 Yes come How do you get yourself here 302 Something that is called car 342 Oh cool 302 Can I have food Or shall I eat 342 Eat We don’t have more food left They eat us out of house The few hours they were here 302 What did they eat 342 All our bread And our dinner 302 What did you have for dinner 342 Pizza |

The creative move, in this case, lies in a sudden and surprising norm-shift performed by adhering to the standard majority norm, Bokmål, and so flouting the locally shared Nynorsk norm. In this highly circumscribed context, the implicit norm is using Nynorsk and dialect features. Sudden use of the majority standard is thus a momentary shift of the common ground of the exchange. But how is it that this shift to Bokmål has the effect of bolstering the humor of the remark? It is plausible that the shift serves to underline the pretense by embodying the voicing nature of the remark, and thus also to undercut any possibility of reading a genuine put-down into it. In having this effect, though, it also serves as an indirect affirmation of a certain kind of mutually shared freedom between two communicators, who here assume a shared stance: when joking, the standard norm is invoked as not-me, not-us, but something that we have at our disposal, as a play-space.

3.3.2 Non-transgressive translanguaging

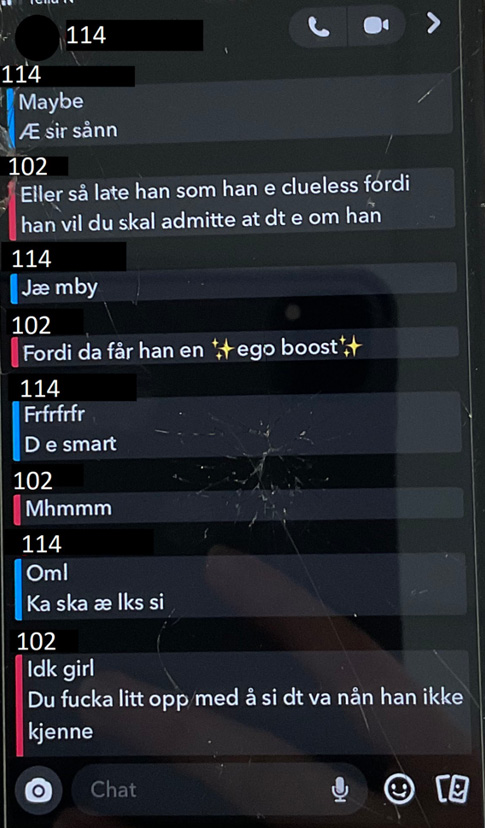

In our final example (3.3), we witness an exchange heavily infused with non-standard writing, including dialect features, Norwegian-specific oral features, DMC-features, and many “English(-ish)” features of different types:

Example 3.3: Chat between two girls age 15 (102 and 114) from Northern Norway

|

|

114 Maybe Æ sir sånn 102 Eller så late han som han e clueless fordi han vil du skal admitte at dt e om han 114 Jæ mby 102 Fordi da får han en ✨ego boost✨ 114 Frfrfrfr D e smart 102 Mhmmm 114 Oml Ka ska æ lks si 102 Idk girl Du fucka litt opp med å si dt va nån han ikke kjenne |

114 Maybe I say like 102 Or he pretends to be clueless because he wants you to admit that it is about him 114 Yeah maybe 102 Because then he gets an ✨ego boost✨ 114 Frfrfrfr [For real x 4] That is smart 102 Mhmmm 114 Oml [Oh my lord] What shall I like say 102 Idk girl [I don’t know gir]l You kind of fucked it up by saying it was someone he doesn’t know |

The dialect features (marked in bold in example 3.3) unmistakably place these youngsters in northern Norway. These are first person personal pronoun Æ/æ (standard Bokmål jeg [‘I’]), omission of consonants which are not pronounced in the dialect (here -l and -r) ska, e, va, late (standard Bokmål skal [‘shall’], er [‘is’], var [‘was’], later [‘pretends’]), adaptation to dialect pronunciation sir, nån (standard Bokmål sier [‘say’-PRS], noen [‘some’]), and the interrogative pronoun ka (standard Bokmål hva [‘what’]).

We also find oral features that are common in Norwegian pronunciation regardless of dialect background, for instance deletion of so-called silent consonants like word final -t (d instead of standard det [‘it/that’]). Interestingly, sometimes only the vowel is omitted, presumably because the pronunciation of the letter -d in Norwegian includes an -e-sound, which means the visual representation dt indirectly suggests the inclusion of the vowel. In this case of what can be called ‘disemvoweling’, the visual graphemic representations seem to be more important than the actual pronunciation since the final -t is never pronounced.

The DMC-features we see are letter reduplication (like Mhmmm), both Norwegian and English acronyms lks (short for liksom [‘like’]) and Idk [‘I don’t know’], and two sparkle emojis (✨) encircling the English-ish loan “ego boost” (“-ish” since both “ego” and “boost” are commonly used in Norwegian). The English(-ish) features are represented in many different ways: standard English orthography (like maybe and clueless, and boost), acronyms (like Oml and Idk), abbreviation combined with letter reduplication (like mby ‘maybe’ and Frfrfrfr ‘for real’). Some of the English loans are adapted to Norwegian morphology (like admitt-e [‘to admit’] and fuck-a- [‘fucked’]. There is also a creative example of phono-stylistic spelling, which presupposes knowledge of both languages, where a Norwegian grapheme is used to illustrate an English word: Jæ sounds like yeah when pronounced in Norwegian. Hence, we observe that the English(-ish) features are represented in various non-standard ways, and also for various purposes.

Here two girls are talking – as teenage girls often do – about a boy, and are debating different possible interpretations of an exchange that one of the girls (114) has had with him. A key point to note is that while these turns exemplify a highly translingual exchange, the sequence also appears conventionalized and norm-bound, with very few marked communicative choices. In spite of the norm-flouting use of linguistic resources, which may appear creative when regarded from a point of view informed by standard written practice, there is no particular move in this exchange that could be read as norm-shifting or particularly linguistically innovative, when regarded from inside the specific context of communication. On the contrary, the easy flow of this conversation about how to read the responses of a third party turns on an extremely finely-tuned shared understanding of the available repertoire. Moreover, while it is infused with non-standard writing, there does not appear to be anything at all transgressive in this exchange. An important feature, though, of this time-slice of a communicative practice, is that the repertoire deployed bears the hallmarks of transience. This is a repertoire undergoing rapid and constant change, creatively absorbing new resources and reforming what is already in use. This kind of game is also a game of norm-shifting – not typically in single abrupt moves, but in the rapid collaborative metamorphosis of the game itself. Competence here is in part an ability to constantly absorb and adjust, in a highly collaborative communicative venture, where the rewards of successful participation are recognition and affirmation of a self with a meaningful contribution to make. Regarded in this way, along the lines suggested by Rochat’s account of human communicators, these mundane examples of teenage written multilectal and multilingual communication afford glimpses into a serious, never-ending game of preservation of identities through perpetual renewal.

4 Conclusion

In our discussion we have demonstrated that creativity displayed through norm-shifting moves can show up both in antagonistic performances and in friendly exchanges. We have suggested that creativity in linguistic performances may be called forth precisely by the tensions between competing communicative goals and constraints. Furthermore, we have placed in question the idea of an inherent link between linguistic creativity and ideological or political transgression. Even in communication where prescriptive norms are deliberately challenged, creative ways of multilectal and multilingual writing are still shaped by norms and normativity.

In sum, we have argued for four main points: (1) First, prescriptive norms are often highly resilient and, accordingly, violations may be conditional or shallow; (2) second, norms are layered, and flouting of prescriptive norms depends on the operational effectiveness of norms that secure uptake – norms thus function both as constraints and as affordances; (3) third, norms securing uptake constitute a largely silent normative common ground; and (4) fourth, this normative common ground may nevertheless be brought into play through norm game performances in ways that disrupt it or shift it.

In making these points we have made use of an interdisciplinary approach. We have relied on Davidson’s philosophical account of interpretation to bring to light the ineliminable collaborative imperative that constrains all kinds of linguistic norm games. Pursuing the subjective side of the sources of linguistic creativity, we have turned to Rochat’s account of the embedded self. He argues that identity-constituting narratives are formed around our hopes and aspirations but must at the same time reflect the truth of experience, of what we have so far been and – to a great but indeterminate extent – shall remain. However, this facticity (to borrow a Sartrean term) to which our self-projections may always be held accountable, is to a very great extent settled by others, by what others recognize in us, and by what they take us to be. This game of mutual self-assertion and recognition is not restricted to antagonistic contexts but is an existential feature of human language use that is at work also in the playfulness displayed in friendly, informal settings.

In conclusion, instances of norm shifts and norm challenges of the sort displayed here should not be seen as special cases or fringe phenomena, nor as acts of inherent socio-political significance, but as frequent and highly adaptable moves typical of human language use. Improvised norm shifts manifest a form of creativity that is basic to linguistic communicative competence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for their generous, insightful and very helpful comments, and the Special Issue co-editors, Cecelia Cutler and Zvjezdana Vrzić, for their comments and support. We would also like to thank Helle Nystad for pointing us to the examples in 3.2 and 3.3, for discussing the data with us, and also for providing excellent comments on the manuscript. Røyneland’s work was partially supported by the research project Multilectal Literacy in Education (MultiLit) funded by the Research Council of Norway (2020–2026, project number 301700).

References

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2011. From variation to heteroglossia in the study of computer-mediated discourse. In Crispin Thurlow & Kristine Mroczek (eds.), Digital discourse: Language in the new media, 277−298. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199795437.003.0013Suche in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2015. Networked multilingualism: some language practices on Facebook and their implications. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(2). 185–205.10.1177/1367006913489198Suche in Google Scholar

Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cutler, Cecelia. 2018. “Pink Chess Gring Gous”: Discursive and orthographic resistance among Mexican-American rap fans on YouTube. In Cecelia Cutler & Unn Røyneland (eds.), Multilingual youth practices in computer mediated communication, 127–145. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316135570.008Suche in Google Scholar

Cutler, Cecilia, May Ahmar & Wafa Bahri. 2022. Digital orality: Vernacular writing in online spaces. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.10.1007/978-3-031-10433-6Suche in Google Scholar

Cutler, Cecelia & Unn Røyneland. 2018. Multilingual youth practices in computer mediated communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316135570Suche in Google Scholar

Davidson, Donald. 2001. Inquiries into truth and interpretation, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0199246297.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Davidson, Donald. 2005. Truth, language, and history (Philosophical Essays volume 5). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.10.1093/019823757X.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Deumert, Ana. 2014. Sociolinguistics and mobile communication. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748655755Suche in Google Scholar

Deumert, Ana. 2018. Mimesis and mimicry in language: creativity and aesthetics as the performance of (dis-)semblances. Language Science 65. 9–17.10.1016/j.langsci.2017.03.009Suche in Google Scholar

Deumert, Ana & Kristin Vold Lexander. 2013. Texting Africa: Writing as performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 17(4). 522–546.10.1111/josl.12043Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia. 2018. Translanguaging, pedagogy and creativity. In Jürgen Erfurt, Eloise Caporal-Ebersold & Anna Weirich (eds.). Éducation plurilingue et pratiques langagières: Hommage à Christine Hélot, 39–56. Berlin: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia & Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging. Language, bilingualism and education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137385765_4Suche in Google Scholar

Gumperz, John. J. 1982. Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511611834Suche in Google Scholar

Hymes, Dell H. 1962. The ethnography of speaking. In Thomas Gladwin & William C. Sturtevant (eds.), Anthropology and human behavior, 13–35. Washington, DC: The Anthropological Society of Washington.Suche in Google Scholar

Jahr, Ernst Håkon. 2014. Language planning as a sociolinguistic experiment: the case of modern Norwegian. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.3366/edinburgh/9780748637829.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Rodney H. 2020. Creativity in language learning and teaching: Translingual practices and transcultural identities. Applied linguistics review 11(4). 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-011410.1515/applirev-2018-0114Suche in Google Scholar

Kharkhurin, Anatoliy V. 2018. Bilingualism and creativity. In Jeanette Altarriba & Roberto R. Heredia (eds.), An introduction to bilingualism. Principles and processes, 159–189. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2011. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43(5). 1222–1235.10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39(1). 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx03910.1093/applin/amx039Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Wei, Tsang, Alfred, Wong, Nick & Pedro Lok. 2020. Kongish daily: Researching translanguaging creativity and subversiveness. International Journal of Multilingualism 17(3). 309–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.176646510.1080/14790718.2020.1766465Suche in Google Scholar

Lunde, Kirsti & Unn Røyneland. 2023. Prosedyre for innsamling av private meldingar. [Procedure for collecting private chat messages]. https://osf.io/jn5t2/Suche in Google Scholar

Mortensen, Janus & Kamilla Kraft. 2022. Introduction: ‘Behind a veil, unseen yet present’ – on norms in sociolinguistics and social life. In Janus Mortensen & Kamilla Kraft (eds.), Norms and the study of language in social life, 1–20. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9781501511882-001Suche in Google Scholar

Nortier, Jacomine & Bente Ailin Svendsen (eds.). 2015. Language, youth and identity in the 21st century. Linguistic practices across urban spaces. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139061896Suche in Google Scholar

Pitzl, Marie-Luise. 2022. Multilingual creativity and emerging norms in interaction: Towards a methodology for micro-diachronic analysis. In Janus Mortensen & Kamilla Kraft (eds.), Norms and the study of language in social life, 125–157. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9781501511882-006Suche in Google Scholar

Ramberg, Bjørn Torgrim. 1989. Donald Davidson’s philosophy of language: An introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramberg, Bjørn Torgrim. 1999. The significance of charity. In Lewis Edwin Hahn (ed.), The philosophy of Donald Davidson (The library of living philosophers, vol. XXVII), 601–617. Chicago: Open Court Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramberg, Bjørn Torgrim. 2004. Naturalizing idealizations: Pragmatism and the interpretivist stance. Contemporary Pragmatism 1(2). 1–66.10.1163/18758185-90000140Suche in Google Scholar

Ramberg, Bjørn Torgrim, 2014. Davidson and Rorty: Triangulation and anti-foundationalism. In Jeff Malpas & Hans-Helmut Gander (eds.), The Routledge companion to hermeneutics, 216–235, London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Rochat, Philip. 2009. Others in mind: Social origins of self-consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511812484Suche in Google Scholar

Røyneland, Unn. 2018. Virtually Norwegian: Negotiating language and identity on YouTube. In Cecelia Cutler & Unn Røyneland (eds.), Multilingual youth practices in computer mediated communication, 145–168. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316135570.009Suche in Google Scholar

Røyneland, Unn & Bård Uri Jensen 2020. Dialect acquisition and migration in Norway – questions of authenticity, belonging and legitimacy. [Special issue] Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 46(4), 937–953. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.172267910.1080/01434632.2020.1722679Suche in Google Scholar

Røyneland, Unn & Elizabeth Lanza. 2023. Dialect diversity and migration: Disturbances and dilemmas, perspectives from Norway. In Stanley D. Brunn & Roland Kehrein (eds.), Language, society and the state in a changing world, 337–355 Springer, Cham. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-18146-7_1410.1007/978-3-031-18146-7_14Suche in Google Scholar

Røyneland, Unn & Øystein A. Vangsnes. 2020. ‘Joina du kino imårgå?’ Ungdomars dialektskriving på sosiale medium. [‘Joining cinema tomorrow?’ Youth dialect writing on social media]. Oslo Studies in Language 11(2). 357–392. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5617/osla.850810.5617/osla.8508Suche in Google Scholar

Sacks, Harvey 1995. Lectures on conversation (Volumes I and II). Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9781444328301Suche in Google Scholar

Sandøy, Helge. 2011. Language culture in Norway: A tradition of questioning language standard norms. In Tore Kristiansen & Nikolas Coupland (eds.), Standard languages and language standards in a changing Europe, 119–126. Oslo: Novus.Suche in Google Scholar

Santello, Marco. 2022. Questioning translanguaging creativity through Michel de Certeau. Language and Intercultural Communication 22(6). 681–693.10.1080/14708477.2022.2084553Suche in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 2007. Spelling and society: The culture and politics of orthography around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486739Suche in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza. 2019. From transliteration to trans-scripting: Creativity and multilingual writing on the internet. Discourse, Context & Media 29. 100294. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uio.no/10.1016/j.dcm.2019.03.00110.1016/j.dcm.2019.03.001Suche in Google Scholar

Sønnesyn, Janne. 2023. Conditions for Nynorsk language use – the role of capacity, opportunity, and desire in the maintenance of Nynorsk among Norwegian adolescents. Sociolinguistica 37(2). 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1515/soci-2022-003410.1515/soci-2022-0034Suche in Google Scholar

Thurlow, Crispin & Kristine Mroczek (eds.) 2011. Digital discourse: Language in the new media, 277−298. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199795437.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Vandergriff, Ilona. 2010. “Humor and play in CMC.” In Rotimi Taiwo (ed.), Handbook of research on discourse behavior and digital communication: Language structures and social interaction, 235–251. Hershey, PA: IGI Global Publishing.10.4018/978-1-61520-773-2.ch015Suche in Google Scholar

Vinichenko, Anya. forthcoming. From speech to screen: Norwegian dialect-writing in the context of multilectal literacy. Nordic Journal of Linguistics.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.