Abstract

This article examines scriptal hybridity in Greek digital discourse through the framework of trans-scripting, a script-focused extension of translanguaging. Moving beyond digraphia and biscriptality, which conceptualize scriptal choice as functionally distributed and socially compartmentalized, trans-scripting highlights how fluid and context-specific recombinations of scripts serve as semiotic resources in mediated discourse and interaction. The analysis focuses on two non-canonical script practices in Greek: Greeklish (Romanized Greek) and Engreek (Greek-scripted English) and is organized in two case studies. The first analyses feature-level script alternations in advertising discourse, utterance-level trans-scripting in online discussions, and instances of trans-scripting in language-ideological discourse. The second case study is based on a diachronic Reddit corpus (151,268 comments, 2015–2021) and documents patterns and functions of Engreek in user-generated discourse. Synthesizing these findings, the paper proposes a typology of four trans-scripting patterns: grapheme-level alternations, rescripting of lexical items and chunks, contextualized double voicing, and language-ideological critique. Trans-scripting simultaneously destabilizes inherited mappings of language and script while reproducing language-ideological fixities, contingent on genre, medium, and interactional context. Overall, the study underscores the importance of scriptal hybridity in contemporary digital literacies and its significance for understanding identity, ideology, and semiotic creativity in networked communication.

1 Theorizing scriptal diversity: from digraphia to trans-scripting

In this paper, we shed light on the complexities and ambiguities of scriptal hybridity as a semiotic resource in public (digital) interaction. We begin by theorizing scriptal diversity and argue that contemporary fluid writing practices are better accounted for in a script-focused translanguaging rather than digraphia framework. In Section 2, we present the range of canonical and non-canonical language/script combinations in the case of Greek public (digital) discourse. In sections 3 and 4, we analyse the pragmatic and indexical potentials of such choices in the context of two case-studies. Section 5 critically discusses our key findings and offers an initial typology of trans-scripting patterns, in terms of, first, the direction of non-canonical script choice and, second, contextual (medium-, domain- and genre-) affordances. With our contribution to this special issue, we foreground the significance of script choice as a (visually salient) semiotic resource in multilingual writing, while pointing to its indexical fluidity and entanglement with historical and contemporary language ideologies and metalinguistic discourses.

Early sociolinguistics privileged speech as an object of enquiry, assigning spoken language qualities such as spontaneous, authentic, and primary in biological, developmental, and historical terms. As a result, spoken language was considered the natural domain of choice for investigating the relationship between language and society (Lillis 2013; Sebba 2012). At the same time, scriptal diversity as a sociolinguistic phenomenon has been largely overlooked by early sociolinguistics, an effect no doubt also due to the location of these phenomena beyond the mainstream Anglo and Northern European spheres. From the late 1990s onwards, the growing interest in scripts (writing systems) and orthographies as socially meaningful choices (Sebba 1998) was triggered not just by a growing awareness of these less-considered practices, but also by social and technological developments that had an impact on writing norms and practices, such as spelling reforms (e.g. in German, Johnson 2002); the redrawing of nation-state boundaries in the post-Soviet world (Bunčić et al. 2016; Wertheim 2012); and the impact of early digital infrastructures on the writing of languages with non-Roman script, such as Greek and Arabic, on the Internet (Androutsopoulos 1998; Palfreyman and al Khalil 2003).

Early sociolinguistic work on scriptal diversity focused on long-standing, historically evolved societal contexts where the same language or language variety is represented in two or more scripts, as with Cyrillic and Roman for the Serbian language (Grivelet 2001; Unseth 2008). Drawing on Ferguson’s (1959) concept of ‘diglossia’, which describes the use of two language varieties in different social domains and with varying prestige (‘High’ and ‘Low’ variety), scholars coined the term ‘digraphia’ to describe the use of two different scripts for the same language within a speech community (Coulmas 2003; Dale 1980). In more recent work, Bunčić et al. (2016: 14) propose the term ‘biscriptality’ as an umbrella term for this range of phenomena, with digraphia representing only one type of biscriptality (Bunčić et al. (2016: 56–63). According to this model, digraphia refers to situations where two or more scripts are functionally distributed in terms of register (‘diaphasic digraphia’), social group (‘diastratic digraphia’), writing medium (‘medial digraphia’) or public and private situation types (‘diamesic digraphia’). Differences among individual scholars aside, digraphia and biscriptality approaches share certain theoretical underpinnings and research interests. They focus on the societal distribution of script choices rather than their interactional use, assuming socially shared language attitudes towards the preference for a particular script by a specific group of language users or type of situation. On these grounds, scripts have the potential to become “iconic of the groups of users themselves or of particular social characteristics which are attributed to them” (Sebba 2012: 3–4). From a digraphia viewpoint, then, scriptal choices are seen as socially and/or situationally compartmentalized, rather than fluid and malleable within an interactional situation.

As computer-mediated communication (CMC) gained social currency in the 1990s, scholars interested in the impact of digital technologies on script choice drew on digraphia and adapted the concept to the empirical sites under study. Technological constraints on script choice on the early Internet were evident in the vernacular Romanized transliteration of languages conventionally written with other scripts (Greek, Arabic, Cyrillic, and others; Akbar et al 2020; Androutsopoulos 1998; Ivkovic 2013). The ASCII code (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) that was installed on early computer and mobile devices afforded only a limited set of graphic signs, notably the letters, numbers, and punctuation marks of the English writing system. Consequently, the vernacular Romanization of a number of languages when written online (as opposed to their representation in their conventional script in all other settings) was widespread and unavoidable until the early 2000s and described as ‘computer-mediated digraphia’ (Androutsopoulos 2009) or ‘medial digraphia’ (Bunčić et al. 2016). In the case of Greek, a language with a diglossic past, this new digraphic condition sparked language-ideological tensions and moral panic discourses (Johnson 2002) related to preexisting language ideologies, such as language purism (Koutsogiannis and Mitsikopoulou 2003; Moschonas 2009: 316). This way, public debates about ‘new’ forms of digraphia were shaped by ‘old’ language hierarchies.

The phase of ‘unavoidable’ Romanization did not last long. The implementation of Unicode on operating systems during the late 1990s and early 2000s allowed for a much wider set of graphic signs in numerous scripts, making vernacular Romanization technically obsolete. In the Greek context, this gave rise to even stronger protest against residual Romanization practices, which persisted among diasporic populations and niche (youth) groups. In this process, Romanization did not fully disappear but became recontextualized (and re-indexicalized) as a semiotic resource both in CMC and other domains of discourse. Since the late 2000s, instances of Romanized Greek occurred online, in newspaper headlines, TV advertisements or in the urban linguistic landscape, and indexed humor, exaggerated expressivity or old writing habits in exchanges among close friends or colleagues (Georgakopoulou 1997; Spilioti 2009). At the same time, the continuing use of Romanization among youth groups and/or diasporic communities boosted its potential to index delocalized identities with transnational or cosmopolitan orientations (Lee and Barton 2011; Spilioti 2009).

The move into ‘post digital’ culture (Cramer 2014), broadly understood as a societal condition where digital media have “become so interwoven into our everyday linguistic activity that we come to depend on them and cannot fathom a world without their presence” (Bhatt 2023: 743; see also Tagg and Lyons 2022), challenges digraphia as a sufficient theoretical explanation of script choice in communicative practice. While digraphia emphasizes how script choice is determined, what is widely observed today are spontaneous, impromptu, and fluid deployments of non-canonical script and spelling choices within digital literacy practices such as messenger interaction, comment sections or digital content creation. Here, script choice is one among other available semiotic resources by which people engage in language play, semiotic remix, or political critique (Dovchin 2015; George 2019; Tebaldi 2020).

Recent work on script choices in digital literacy practices orients to translanguaging, a theoretical paradigm that focuses on language practices which transgress preconceived language boundaries, and at the same time critiques the ideological construal of such boundaries (García and Li 2014; Lee and Li 2020; Lee and Dovchin 2020). The terms trans-scripting (Androutsopoulos 2015; Spilioti 2020) and tranßcripting (Li and Zhu 2019) take translanguaging to a microanalysis of digital written language, with trans-scripting explicitly paraphrased as script-related translanguaging (Androutsopoulos 2015:188). Unlike the macro-level scope of digraphia and the structuralist underpinnings of biscriptality, the notion of trans-scripting focuses on digital literacy practices that transgress historically inherited mappings of scripts to languages (e.g. English language and Roman script) while at the same time presupposing an awareness of these mappings. In the case studies below (Sections 3 and 4), we see the Greek language written in the Roman script (‘Greeklish’) and, conversely, English cast in the Greek script (‘Engreek’). In both cases, participants mobilize language skills to write and/or read one language from their repertoire in the script of another. As in spoken translanguaging, languages and scripts are coactivated in production and interpretation, and inference work is required to figure out why an English segment is not set in the default Roman script in a particular context. Trans-scripting is thus conceived as an intentional act of recombining scripts and languages in non-canonical and visually salient ways, thereby potentially evoking a range of pragmatic and social meanings.[1] Again, while digraphia models emphasize the social distribution of script choice across domains and groups, trans-scripting foregrounds the creative and experimental agency of languagers and at the same time the crucial role of digital affordances in creating the condition of possibility for scriptal experiments. The two case studies support our claim that deployments of script in digital literacy practices are theoretically better accounted for in a translanguaging rather than digraphia framework.

2 ‘Greeklish’ and ‘Engreek’: non-canonical script choices in Greek

At the microlevel of script and spelling choices, trans-scripting can involve a range of techniques from the consistent choice of non-canonical script for an entire text or stretch of discourse (e.g. a meme, George 2019) to highly salient reconfigurations of letters from different source languages in a hybrid ensemble (Li and Zhu 2019). In addition, these techniques differ by language and the scriptal resources that comprise its writing system. Japanese, for example, makes use of several scripts (Kanji, Hiragana, Katakana), which afford opportunities for non-canonical deployment (Robertson 2022); therefore, the notion of non-canonical script choice, which is key to our analysis, is not an absolute one, but must be specified for the sociolinguistic context under examination.

In this paper we examine trans-scripting practice and discourse in the case of Greek, starting here with a general distinction of canonical and non-canonical language/script relations. The Greek language has been written in different scripts in the course of its history; conversely, the Hellenic script has been used for the representation of other languages (Androutsopoulos 2009: 362–363). We focus here on the alternation of Hellenic and Roman script for the representation of the Greek and English language, as displayed in Table 1. Two out of four cells display (in bold type) the canonical combinations of language/script choice that written English and Greek relies on. Our interest in the following is in non-canonical combinations of (in italics), which are culturally salient outliers. Any token of such non-canonical representation becomes meaningful against its canonical backdrop.

Canonical and non-canonical combinations of language/script choice for English and Greek, on the example <now>, <τώρα>

|

|

LANGUAGE |

|

|

SCRIPT |

Greek |

English |

|

Hellenic |

τώρα |

νάου |

|

Roman |

tora, twra, tvra |

now |

The bottom left cell stands for ‘Greeklish’, the vernacular Romanization that became compulsory in early Internet days (as discussed in Section 1) and morphed into an intentional script choice later. The three spelling variants in the cell are all possible and attested ones, brought about by the lack of a transliteration standard, but differently motivated, i.e. by phonological equivalence (tora), visual similarity (twra), or material convenience, notably the position of the keys on the keyboard: the form tvra reflects the placement of Greek omega, <ω> on the same key as Roman <v>. Our focus, however, is on the non-canonical combination displayed at the top right, where English lexis is cast in the Greek script. In Greek public discourse this goes by the term Engreek (as a counterpart to Greeklish), while more transparent terms are ‘Hellenized English’ or ‘Greek-scripted English’. This practice is overall more recent, less well documented, and socially less prominent. Unlike Greeklish, Greek-scripted English does not originate in technological necessity, but in an intentional rescripting of English-language segments into the script of the base language of communication, i.e. Greek. That is, writers produce a segment that knowingly originates in English, such as the adverb ‘now’, while still typing on the Greek keyboard layout, thus yielding the homophone form, <ναου>. As noted elsewhere (Androutsopoulos 2020), this practice contextualizes the rescripted segment as part of a Greek-speaking discourse and can also evoke an imaginary ‘Greek accent’ in silent reading. Since it involves a transformation and appropriation of the dominant code of cultural globalization, Greek-scripted English can also be theorized at the interplay of ‘global’ and ‘local’ orientations and stances (Androutsopoulos 2010; Tebaldi 2020).

In the remainder of this paper, two case studies shed light on this interplay of languages and scripts, drawing on data from public linguistic landscapes and digital discourse. We are aware of the lack of reliable information about the participants and their socio-demographics. Our focus lies on observable communicative practices and their outcomes, and our continuous observation of trans-scripting practices on- and offline helps uncover formal and pragmatic patterns, which in turn allow conclusions about the sedimented indexical values of script choice in various contexts of discourse. Both studies draw on public domain data, including data from online discussion forums. While registration is required to post on these forums, no limitations are imposed on reading (on a browser), thus not necessitating permission to collect data, especially when content is of general interest and not sensitive. In line with established ethical guidelines (Association of Internet Researchers: aoir.org/ethics), the anonymity of posters is protected by not recording usernames, and minor modifications were used to prevent the searchability of verbatim quotes and potential reidentification of users.

Excerpt from campaign video by Athens International Airport (Source: ATHairport 2014)

3 Case study 1: aesthetics and ideologies of Greek-scripted English

The first case study draws on research that investigates Greek-scripted English (‘Engreek’) in various online and offline settings based on a multi-sited approach to data collection (Spilioti 2014, 2019, 2020; Spilioti and Giaxoglou 2021). This research started by collecting and analysing instances of Greek-scripted English on various online sites (webpages of a satirical TV show, comments to humorous YouTube videos), and later opened to other genres (memes, online marketing) and data from urban spaces (graffiti, advertising posters, shop signs), leading to a collection of 1116 tokens of Greek-scripted English (Spilioti 2019). The formal analysis of this data has shown that script alternation takes place primarily at the level of individual graphemes, words, and utterances/posts, with very rare use of ‘Engreek’ in long sequences of subsequent posts. Compared to Romanized Greek, there are two distinct patterns in Greek-scripted English: formally, the grapheme-level script alternations (section 3.1); and interactionally, the use of fluid scriptal hybridity in language-ideological discourse (section 3.2). These are examined by first exploring a marketing campaign and second, instances of language-ideological debates in online public forums.

3.1 Feature-level trans-scripting in marketing discourse

‘Feature-level trans-scripting’ (Androutsopoulos 2020: 291) refers to the occasional intentional mixing of graphemes from the two scripts within the same word and, by repetition, within a phrase or clause. This technique is not documented for Greeklish or other early cases of vernacular Romanization. By contrast, it is at the core of tranßcripting as described by Li and Zhu (2019), which involves mixing Chinese, English and other graphemic resources. It is also consistent with other documented cases of mixing letters from different orthographic systems for salience, comic effect or cryptic purposes, with examples including the German Umlaut (Spitzmüller 2012) or the mixing of German diacritics and English spelling (e.g. ‘hilariös’, Jaworska 2014).

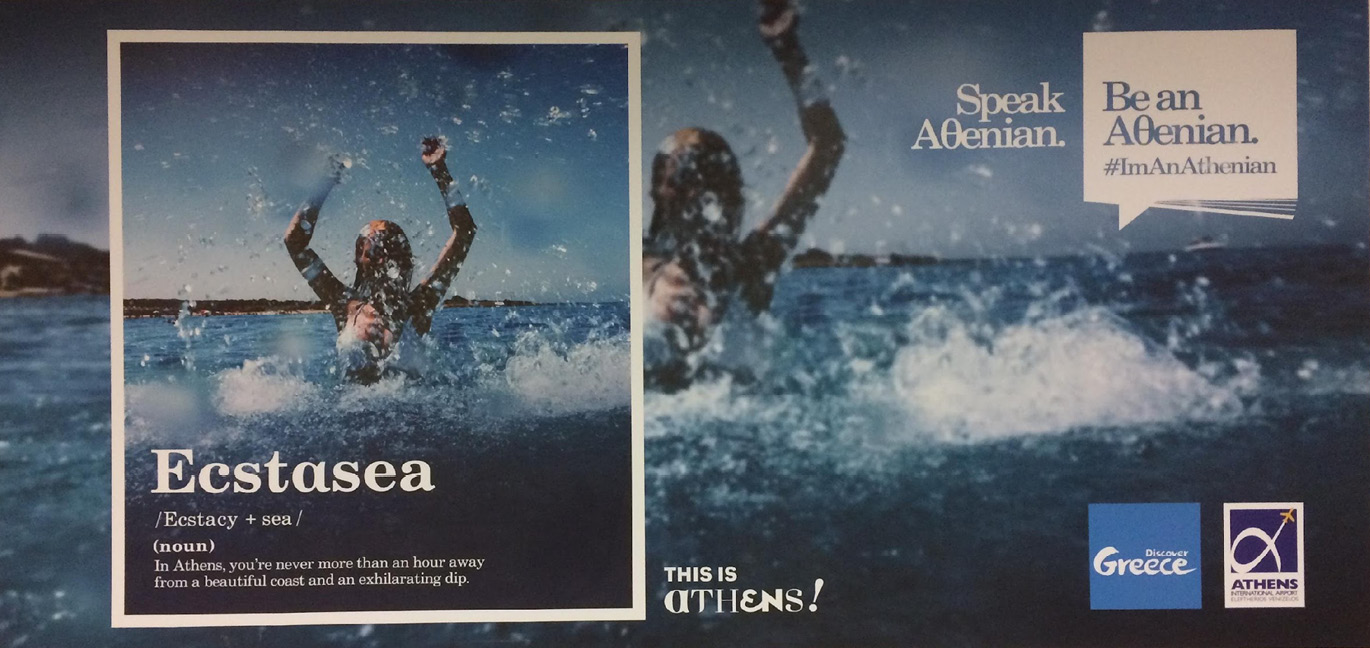

In the Greek context, this type of script alternation thrives in public domains and has primarily aesthetic and symbolic value. To illustrate this, we consider a marketing campaign by the Athens International Airport (2014–2016) which aimed to promote tourism in Greece and portray Athens as a top city break destination (for further discussion see Spilioti and Giaxoglou 2021). As evident in the campaign slogan ‘PerhaΨ you’re an AΘenian too!’ (Figure 1), rescripting is limited to the substitution of the digraphs <ps> and <th> with the Greek letters <Ψ> and <Θ> accordingly.[2] This minimal substitution is primarily aesthetic and does not interfere with the literal meaning of the message. The limitation of script alternation to only one or two graphemes allows the reader to compute the meaning of the sentence, even with only minimal or no understanding of the phonemic value of the Greek letters.

The same pattern of minimal script alternation is repeatedly deployed in the campaign video and posters, with examples displayed in Table 2. The individual Greek graphemes are selected on account of their difference from the Roman alphabet; out of ten capital letters that are unique to the Greek script, six <Θ, Λ, Π, Σ, Φ, Ψ> are used in the campaign. Their selection, therefore, contributes to visually foregrounding the difference(s) between the ‘familiar’ (embodied here by the choice of English) and the ‘new’ and ‘exotic’, represented by the unfamiliar script, which by extension indexes ‘Greekness’. At the same time, these graphemes also allude to the global relevance of Greek characters in maths, sciences, and material culture (cf. π for the mathematical constant 3.14, Σ for summation in statistics, Ω for ‘Omega’ wrist watches, Greek initials for US college fraternities, etc.). This reading is consistent with the campaign’s own discourse, notably a YouTube video that points out: “The campaign […] “plays” with the letters of the Greek alphabet and with global concepts of Greek origin, such as “history”, “harmony”, “philoxenia”, etc.” (ATHairport, 2014; our translation).

Examples from the campaign ‘Perhaps you’re an Athenian too!’

|

Feature-Level Trans-scripting (examples) |

Original Grapheme(s) |

Substitutions |

|

An AΘenian keeΠs on making history |

th – p |

Θ – Π |

|

An AΘenian is a Φun enthusiast |

th – f |

Θ – Φ |

|

An AΘenian Φinds harmony in nature |

th – f |

Θ – Φ |

|

An AΘenian enjoys a bΛue paradise |

th – l |

Θ – Λ |

|

An AΘenian enjoys a plethora of taΣtes |

th – s |

Θ – Σ |

|

An AΘenian can Σee comedy in tragedy |

th – s |

Θ – Σ |

|

An AΘenian knowΣ about philoxenia |

th – s |

Θ – Σ |

|

An AΘenian reinvents claΣΣical myths |

th – ss |

Θ – ΣΣ |

When feature-level trans-scripting becomes part of a marketing campaign, as in this case, typography is mobilized not just as a necessary medium of representation (what Stöckl 2005 aptly calls the ‘body’ of written text), but also as an aesthetic, connotation-rich resource, i.e. the text’s ‘dress’ (Stöckl 2005). The Greek graphemes appear always capitalized against a default lower-case script and are thereby visually foregrounded (Figure 1). They are also cast in blue, against the grey of the Roman type, a colour choice that is probably motivated by the colour of the Greek national flag. In addition to script alternation, these campaign posters also feature instances of ‘typographic mimicry’ (Meletis 2021), whereby typefaces that are part of one script emulate visual features of a different script. In Figure 2, the Roman graphemes <a> and <e> (see Athens, bottom part of poster) are shaped in a style that is reminiscent of elegant Greek typography. As Meletis (2021: 2) points out, typographic mimicry aims at evoking associations with a corresponding “foreign” culture, underlining the indexical potential of typeface choices and their cultural, as well as ideological, values. In this case, script and typographic alternations work together to evoke cultural stereotypes associated with ‘Greekness’ in a similar way to the construal of graphic Germanness by means of Fraktur typeface (Spitzmüller 2015). The aesthetic manipulation of the typefaces, the resulting exoticization of the script and the evoked cultural associations contribute to the presentation of ‘Greekness’ as both familiar and exotic. Considering that these campaign posters are developed by Greek graphic designers and marketing professionals,[3] such choices also reveal a process of self-exoticization by which a rather stereotypical image of one’s own culture is reproduced and reinforced for a diffuse international audience.

Campaign poster, Athens International Airport (Source: Author’s personal photos, 2015)

Overall, this playful mixing of linguistic, scriptal and typographic resources are exemplary enactments of ‘banal globalization’, which Thurlow and Jaworski (2011) describe as every day, micro-level ways in which the social meanings and material effects of globalization are realized. Through the mobilization of rescripted forms, the campaign alludes to and authenticates a hybrid cosmopolitan identity for Athens, and Greece, both familiar and exotic. The production of ‘commodified authenticities’ (Heller 2014) through trans-scripting, deployed here as a resource for advertising discourse, is an integral part of place-branding strategies that aim to resonate globally while retaining local specificity, portraying Greece as both rooted in the historical past and accessible to the present global traveller.

3.2 Utterance-level trans-scripting and language-ideological discourses

With ‘utterance-level trans-scripting’, non-canonical scripting extends over a larger stretch of discourse (Androutsopoulos 2020: 291). Previous work has identified (sparse) instances of Greek-scripted English in various interactive online settings, ranging from discussion forums to social media platforms. Non-canonical script choices there often go both ways, i.e. include Romanized Greek as well as Hellenized English, and both patterns can be observed coexisting in a discussion thread of comment section, or in a set of memes.

Early instances of utterance-level Hellenized English were identified in diasporic Facebook groups among transnationally mobile Greeks (Spilioti 2014). Greek-scripted English appeared as one among several semiotic resources by which participants created style shifts, especially from a serious to a jocular interactional modality. At the same time, it became a resource for marking various Greek stereotypes, such as the ‘last minute’ improvising Greek (Spilioti 2014) or the ‘uncultivated’ Greek with their heavily accented English. This latter stereotype was heavily reinforced by memes and videos that targeted the former Greek PM, Alexis Tsipras, and his lack of proficiency in English (Androutsopoulos 2020; Spilioti 2020), juxtaposing his English solecisms to images or subtitling his videos in Greek-scripted English to expose pronunciation issues and performance errors. Paradoxically, these displays of rescripted English to critique a hybrid spoken delivery (i.e. Greek-accented English) are measured to the ideal of the native English speaker. In other words, semiotic hybridity eventually promotes language ideologies of native speakerism and purism.

With respect to language ideological discourses and non-canonical script choices, we have mentioned that the reverse phenomenon of Romanized Greek has sparked lively language ideological debates and linguistic moral panics (Johnson 2002) in Greek society, especially as the technological necessity that legitimized its early use became obsolete. Greeklish was heavily attacked as a threat to national language and identity, among others in a 2001 statement by the Academy of Athens and a media campaign by the satirical TV show, ‘Radio Arvyla’, in 2011. These arguments were widely recycled in the press and profoundly influenced the wider discourse around language/script tensions in Greece (Koutsogiannis and Mitsikopoulou 2003; Moschonas 2009; Mouresioti and Terkourafi 2024). As an outcome, trans-scripting practices are understood by large parts of Greek society as challenging standard norms, national language ideologies and, ultimately, nationalism. Example 1 illustrates how this critique plays out.

[4] (2014)

|

|

Original |

Translation/Transliteration |

|

@user1 |

Sorry alla to mati sas to alloi8wro! kati tetoia paidia e3eliswntai se antikoinwnikous prezwnes, ceytes, kleftes kai apatewnes epi to pleiston gia na synthroyn thn alazwneia poy toys ema8an oi filodo3oi goneis na exoyn gia dikh toys xrhsh! Ta alla paidia toys kanoyn grhgora sthn akrh [part omitted] |

“Sorry but you are a fool! such kids turn out to be antisocial junkies, liars, thieves and mainly crooks, to feed the arrogance their ambitious parents had instilled on them! The other children soon marginalize them [part omitted]” |

|

@user2 |

Πλοιζ ράοιτ οιν γκροικ. Γκροικ ηζ δαι λάνγκουιτζ γουεί σποικ αιντ ράοιτ οιν Γκροισς. |

“Please write in Greek. Greek is the language we speak and write in Greece.” |

This is an exchange on a general interest public forum that discusses the ‘birth order’ effect (i.e. how birth order can influence personality and psychological development). @user2 engages in trans-scripting (Greek-scripted English) to criticize the hybrid script choice of @user1 (Greeklish). Through the appropriation of trans-scripting and subversion of Greeklish (i.e. ‘dressing’ English as Greek, rather than vice versa), the reply positions @user1 as the ‘other’, as somebody who does not adhere to the norms of the community. In this case, the community is not defined as an online space but in offline and national terms, i.e. as part of the sovereign Greek nation state. Scriptal fluidity here does not challenge any borders, but it reproduces them. While this discussion unfolds in transnational virtual space, the second comment explicitly reterritorializes the discourse and alludes to nationalist ideologies, emphasizing the bond between nation and language. Nonetheless both turns are part of a translanguaging practice, as their production and reception mobilize translingual competence for meaning making (reading the Roman script, parsing grapheme-to-grapheme mappings across scripts, recognizing English lexis and syntax through the Greek script).

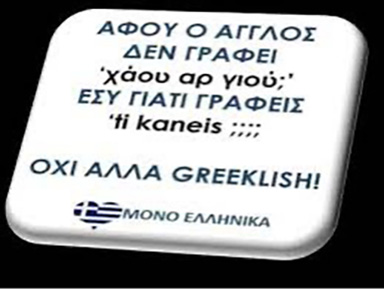

Such use of semiotic fluidity to reify norms and hierarchies is also evident in messages circulated in extreme-right forums. The call to ban Greeklish has been particularly popular among far-right supporters. Figure 2 illustrates one of the postings to this effect.

(2016)

|

Original |

Translation/Transliteration |

|

|

|

“SINCE THE ENGLISHMAN DOES NOT WRITE ‘χάου αρ γιού;’ [‘how are you?’] WHY DO YOU WRITE ‘ti kaneis;;;; [‘how are you’????] NO MORE GREEKLISH! [Greek flag in heart shape] ONLY GREEK” |

|

We again see how a scriptal hybrid, Hellenized English, is deployed to critique the use of Romanized Greek. In this case, the figure of a foreign ‘other’ (i.e. ‘Englishman’) and a constructed example of trans-scripting are used as a mirror against which one can reflect on their own hybrid practice. Similar to mock translanguaging (Tebaldi 2020: 209), mock trans-scripting attests to the use of fluid language in ways that create demeaning figures of alterity (Hastings and Manning 2004) and support far right discourses and ideologies. In this context, semiotic hybridity becomes a resource for reproducing, rather than challenging, social norms and national hierarchies.

4 Case study 2: Greek-scripted English on Reddit

The second case study draws on micro-diachronic data from the largest Greek-speaking forum on Reddit, r/Greece, with around 100k members at the time of collection and 250k members as of mid 2025. A large dataset was compiled by scraping the first 1000 discussion threads every six months from August 2015 until August 2021. This yielded a total of 151 268 comments and several million words, and the gradual increase of the data size from 2015 to 2021 is an apt indicator of Reddit’s rising popularity in Greece.[5] Collected metadata include the timestamp for each comment, the title of the respective submission (i.e. the post that opens a new thread), and a URL to the original posting. This dataset contains several instances of both Greeklish and Greek-scripted English, but the present analysis focuses on the latter.

To retrieve instances of Greek-scripted English, word searches for items that were repeatedly observed in earlier examples were carried out, notably grammatical words such as ‘you’ <γιου>, ‘for’ <φορ>, ‘well’ <γουελ> and lexical items such as ‘god’ <γκοντ>, ‘love’ <λαβ>. All of these are graphemically quite distinctive with hardly any Greek homographs. Iterative searches for these items on the annual r/Greece datasheets yielded a total of 93 comments that contain at least a short segment of Greek-scripted English. All hits, including metadata, were then transferred to a new datasheet and qualitatively coded for the following features:

formulaic language, providing a grip to repetitions in linguistic expression

segment to comment ratio, i.e. whether the rescripted segment makes up an entire comment or is just part of it

size of the rescripted segment, i.e. a clause with a finite verb or not; and

context notes, especially regarding intertextual references.

Most of the entries were then followed back to their original sequential environment (based on the automatically retrieved URLs), a step that is necessary to figure out how rescripted items are interactionally brought about. While the scraped Reddit dataset is not statistically representative and the retrieval method is not exhaustive (indeed, the qualitative look-up of hits in their sequential context sometimes brought up additional segments of Greek-scripted English), the retrieved segments all originate in a single discussion forum and are deemed sufficient for the paper’s purpose.

4.1 Rescripted English lexis and chunks

As noted in Androutsopoulos (2020), some English-origin lexical borrowings are eventually graphemically integrated into Greek, thereby yielding Greek-scripted loanwords such as <ποπ> ‘pop’, <ροκ> ‘rock’ or <σταρ> ‘star’. Not all loanwords follow this pattern, and graphemic integration is possibly influenced by factors such as word length, semantic domain and diachronic depth, which are not further discussed here. The important point here is that several recent rescripted loanwords occur in the Reddit data (Example 3). This list is not exhaustive; more types exist, as well as more tokens for some of the listed types.

Selected lexical rescriptings (Roman back-transliteration to the right)

|

(1) |

νετφλιξ |

Netflix |

|

(2) |

γιουτούμπ |

YouTube |

|

(3) |

γιουτιουμπερ |

YouTuber |

|

(4) |

εκοτσάμπερ |

echo chamber |

|

(5) |

φανμποϋς |

fanboys |

|

(6) |

γιουζερ |

user |

|

(7) |

βιντεογκέιμς |

video games |

|

(8) |

σαητ |

site |

|

(9) |

οφ τόπικ |

off topic |

|

(10) |

νταουνβόουτ |

downvote |

Lexical rescriptings concentrate on semantic fields such as digital culture, platforms, and associated social media types (user, fanboys) and practices (downvote). Almost all items are novel rescriptings, not diachronically attested ones, in some cases not even spread across the entire Greek-speaking Internet.[6] As the transition from Roman to Hellenic script does not follow a prescription or policy, the fact that certain items (e.g. YouTube) are regularly rescripted but not others must be attributed to usage and sample limitations. In the absence of standardization pressures, alternative rescripting variants emerge. In the following exchange (Example 4), the item ‘site’ (for ‘website’) is transliterated in two different forms, none of which corresponds to the form listed in Greek Wiktionary, i.e. <σάιτ>. One is a phonetic approximation, <σαητ>; the other an exact repetition of the English keyboard strokes, <σιτε>, which yields a different phonetic form in Greek, ['site] rather than ['sait], but is nonetheless responded to in the thread, thus deemed acceptable in the sequential exchange.[7]

(2020), English lexis in the original post set in bold

|

|

Original |

Translation |

|

Submission title |

Ξερει κάνεις που μπορω να βρω παλια vintage περιοδικα ειτε σε μαγαζι στην Θεσσαλονικη ειτε από σιτε σε ψηφιακη μορφή; |

“Does anybody know where to find old vintage magazines either in a shop in Thessaloniki or on a site in digital format?” |

|

Comment |

Μήπως λες αυτό το σαητ; [URL] |

“Maybe you mean this site?” |

A second set of hits involves multi-word English-origin items that rescript conversational (in some cases, vernacular) phrases and formulae from everyday speech (Example 5). While a detailed investigation by item is beyond our scope, we see some widely used expletives (various fuck expressions, as in lines 3,4); conventional politeness formulae, also reminiscent of hospitality interactions (thank you, here you are, you’re welcome); and some intertextual references, e.g. change my mind, part of a popular Internet meme.[8]

Selected rescripted chunks and phrases

|

(1) |

Γιου νεβερ νοου |

you never know |

|

(2) |

απλά φορ δε σεικ οφ χιουμορ |

just for the sake of humor |

|

(3) |

Γουελ, φακ. |

Well, fuck. |

|

(4) |

ΣΑΤ ΔΕ ΦΑΚ ΑΠ! |

Shut the fuck up! |

|

(5) |

Χίαρ γιου αρ |

here you are |

|

(6) |

Χιαρ γιου γκοου |

here you go |

|

(7) |

Θενκ γιου! |

Thank you! |

|

(8) |

Οοο θενκ γιου ε λοτ |

oh thank you a lot |

|

(9) |

Θενκ γιου ομως ρε συ |

thank you, my dear |

|

(10) |

Ααα γες, θενκ γιου μαϊ Γκουντ μαν |

ah, yes, thank you my good man |

|

(11) |

Γιορ γουελκαμ |

you’re welcome |

|

(12) |

Ναι μαν, γιου γκότ μι. |

Yeah man, you got me |

|

(13) |

Τσειντζ μαι μαιντ. |

Change my mind |

English-origin chunks (multi-word formulaic expressions) are popular in urban social networks among young people and adults in Greece (and elsewhere), some already documented since the late 1990s as a (then) new form of English/Greek language contact (Makri-Tsilipakou 1999). This formulaic repertoire is strongly influenced by cultural contact, more specifically exposure to the global English-language entertainment industry (pop culture, games, movies) and thus characterized by a high degree of intertextuality and renewal through the constant addition of new formulaic material (Kulavuz-Onal and Vasquez 2018). Several items in example (5) occur in the Reddit data both in their native form (i.e. as a code-and-script switch within a Greek-base comment) and as a rescripted form. Moreover, writers repeatedly combine rescripted English chunks with Greek discourse markers (e.g. lines 2, 10, 11, 13), which we read as implying a conventional conversational usage of the English chunk in Greek-speaking discourse; for example, in line (2) the clause-initial modal adverb ‘just’ comes in Greek, followed by the rescripted English chunk; in line (11) the initial discourse marker is spelt <Ααα>, as is common in Greek, not English <ah>.

The pragmatics of rescripted chunks varies by discourse context. In several cases, rescripted chunks index the writer’s own perspective or stance, rather than double-voicing, discussed below (Section 4.2). For example, item (4) <ΣΑΤ ΔΕ ΦΑΚ ΑΠ!> ‘shut the fuck up!’ is part of a longer argument between the writer and another user, and expresses the writer’s own sentiment. In our analysis, this item involves a dual move within the writer’s translingual repertoire, i.e. (a) the choice of an English expletive over an equivalent Greek expression, which may be heard as somewhat exaggerated or excessively expressive; and (b) rescripting, which frames the English chunk as part of Greek-speaking discourse. Language and script choice work together as contextualization cues (Gumperz 1982). Likewise, Example (6) is part of a dispute between two users who both draw on irony to disparage the other’s stance. Both the comment and reply have the same structure, starting with a discourse chunk that leads to an elaboration. The first chunk comes in Greek (νταξ ρε φίλε μας έπεισες, ‘Sure mate, you persuaded us’); the second in Greek-scripted English (Ναι μαν, γιου γκότ μι, ‘Yeah man, you got me’). Both are semantically similar and have the same pragmatic effect, i.e. they mock persuasion. The comment’s opener does so in Greek throughout and so does the reply opener, yet in rescripted English. Hence, we see rescripting involved in a paradigm of repetition und variation.

(2016), English lexis in the original post set in bold

|

|

Original |

Translation/Transliteration |

|

Comment |

νταξ ρε φίλε μας έπεισες. θα κυνηγάς την ουρά σου όλη μέρα αντί να απαντήσεις μια απλή ερώτηση |

“Sure mate, you persuaded us. You’ll be chasing your tail the whole day long instead of answering a simple question” |

|

Reply comment |

Ναι μαν, γιου γκότ μι. [one omitted para] |

“Yeah man, you got me.” [one omitted para] |

4.2 Utterance-level trans-scripting: hedging, voicing, joyful hybridity

Another set of hits are longer segments of Greek-scripted English, especially clauses that often stand alone as entire comments. These are neither conventional loanwords nor chunks that readily index spoken vernacular style; some are recognizable intertextual references (see Example 10 below). While the items in this subset fan out into various patterns of usage, a common denominator is double-voicing (Bakhtin 1971). That is, the combined effect of language choice (i.e. English over Greek for a comment or part thereof) and script choice (i.e. rescripting from Roman to Greek) indexes a socially typified position or stance that diverges from the surrounding discourse (see Androutsopoulos 2023 for a voice analysis of Reddit discourse). The following examples illustrate how this plays out in the data.

In some cases, the Greek-scripted English segment is interpretable as a face-saving device. Example 7 displays two replies to previous, Greek-language comments. In both cases, short clauses in rescripted English round up the preceding assertion and express a sort of ‘well-known truth’ related to self-esteem or Internet culture. The combined effect of language and script choice can be read as playing down a potential face-threat to the addressee.

(Both items are entire comments; English segments in the original set in bold)

|

Original |

Translation/Transliteration |

|

(1) Responds to a post that seeks advice on breast cosmetic enhancement without a surgery (2019) |

|

|

Δεν νομιζω πως υπαρχει φυσικος φυσικος τροπος να γινει αυτο. Τζαστ αξεπτ χου γιου αρ:) |

“I don’t think there’s a natural way of doing this. Just accept who you are:)” |

|

(2) Comments on another user’s previous posts (2019) |

|

|

Πρέπει να χάρηκες πολύ που νίκησες ένα τρολ στο ίντερνετ. Άι γκες γιου νιντ α λάιφ τού μαι φρεντ |

“You must be very happy you won over a troll on the Internet. I guess you need a life too my friend” |

In another subset of hits, the rescripted segment indexes the metapragmatic frame of quoting or is itself a metapragmatic commentary, i.e. the combined effect of language/script choice indexes the boundary between quoted or referenced speech and the surrounding discourse. More specifically, the data includes some discussions about English language learning where English expressions are rescripted. In other cases, participants share and discuss video clips where native Greeks speak English, and quoted speech from these videos comes in rescripting, often with a denigrating purpose.

(Both comments are set entirely in Greek-scripted English)

|

Original |

Transliteration |

|

(1) Quoted speech by extreme-right Greek politician (2016) |

|

|

Ιβ γιου μπιλίβ δέι αρ τούρκισ γιου μαστ γκόου του Τούρκι |

“If you believe they are Turkish you must go to Turkey” |

|

(2) Comments on another user’s choice of English (2020) |

|

|

γιου καν βράιτ ολσο ιν γκρικ, σι γουιλ μοστ σερταινλυ αντερσταντ |

“You can write also in Greek, she will most certainly understand” |

In line (1), a Reddit user quotes the speech of a Greek extreme-right politician speaking English. The speech is rescripted in a way that exposes second-language features, in phonology and grammar, in the quoted voice. More specifically, the rescripted items <τούρκις> ‘Turkish’ and <Τούρκι> ‘Turkey’ index the politician’s pronunciation with [u] rather than [ʌ] and [s] rather than [ʃ]. This is quite similar to other cases (see Section 3.2), where the rescripting of direct speech reinforces the metamessage of ‘English with an accent’. In yet other cases, Greek-scripted English is explicitly metalinguistic. In line (2), the topic is a query by a foreign visitor about street safety in Athens. This query is phrased in machine-translated Greek, and several responses point this out. One preceding comment responds in English, and the one in line (2) uses Greek-scripted English to indirectly criticize that choice of English as unnecessary or inappropriate.

In still other cases, trans-scripting is encased in moments of language play, another well-known translanguaging motif (Lee and Li 2020). The combined effect of switching to English while not switching the keyboard layout to Roman instantiates here a clash of cultural frames, which is taken up and jointly elaborated by forum participants (Examples 9, 10).

(2019), entire comments, English segments in the original set in bold

|

Original |

Translation/Transliteration |

|

Γιορτή πατάτας φορεβαρ |

Potato Festival forever |

|

Γιορτή Φακής στην Εγκλουβή, μπίτσιζ |

Lentil Festival in Englouvi, bitches |

|

Γιορτή του σκόρδου φορ δε γουιν ρε!! |

Garlic Festival for the win, you all! |

The context of Example 9 is a post about a ‘Sardine Festival’ that takes place in a Greek countryside village in the summertime. Some participants find this funny and produce variations of the phrase, <Γιορτή σαρδέλας>, ‘Sardine festival’. Three tokens of the ‘X festival’ construction occur in a thread of 23 comments, all followed by a rescripted English expletive that adds jocular emphasis. Evident here is an element of cultural incongruence, as these English phrases, themselves highly indexical of an urban style, are latched on these imaginary festival names with Greek agricultural produce.

(2019), entire comment

|

Original |

Translation/Transliteration |

|

Πατρόλινγκ δε βοσκοτόπια μέικς γιου γουίς φορ α νούκλιαρ γουίντερ. |

‘‘Patrolling the meadows makes you wish for a nuclear winter.’ |

In a similar vein, Example 10 responds to a posted photo of a Greek landscape with the caption, ‘what is closest to Nevada in Greece’. Here, the frame offered by the original post is taken up with a meme reference,[9] which is modified by adding the Greek term βοσκοτόπιa (‘meadows, pastures’ instead of the meme quote’s original reference, ‘Mojave’). This is the thread’s highest upvoted comment, and other commenters index their recognition of the quote and the video game it originates from. This is one out of several examples where Greek-scripted English occurs in references to video games, sci-fi movies, or pop music. In all these cases, Greek-scripted English comments are not themselves the starting point of a discussion but rather brought about in the conversation flow and often taken up, revoiced and further modified by others.

5 Conclusions: trans-scripting patterns and their indexical fluidity

The two case studies uncover the multifaceted use of script-related translanguaging at the interface of Greek and English language, and Hellenic and Roman script. Case study 1 offered an examination of trans-scripting across off- and online contexts and from a micro-diachronic perspective, while case study 2 focused on a corpus-driven examination of Greek-scripted English in a large Greek discussion forum on Reddit. Taken together, both studies shed light on the complexities and ambiguities of scriptal hybridity as a semiotic resource but also reveal some recurrent usage patterns. In the concluding discussion, we first group together these usage patterns (Table 3) and then discuss their pragmatic potentials and ambivalences.

A major finding of this paper is that the pragmatics and indexicalities of trans-scripting are finely differentiated by, first, the direction of non-canonical script choice, and, second, the context of discourse, in particular genre and participation framework. As summarized below, there are clear differences between Romanizing Greek and Hellenizing English. Likewise, there are huge differences between airport marketing posters (study 1) and Reddit discussion forums (study 2). Marketing posters and memes may reach a high degree of publicity and virality, whereas online discussions offer opportunities for interactional uptake and alignment. Greek practices of trans-scripting are closely related to these domain- and genre-specific affordances. The common denominator between Romanizing Greek and Hellenizing English is not their pragmatic functions, but the underlying process of transgressing inherited boundaries between language and script. By probing non-canonical recombinations, language users engage in translanguaging in the concept’s basic sense, i.e. a coactivation of semiotic resources at the multiple levels of writing and reading, cognition and socio-pragmatics. Taken together, we propose to group different patterns of trans-scripting into four distinct types, displayed on Table 3 and briefly discussed below.

Trans-scripting patterns in the two case studies

|

Type |

Context of use |

Discussion |

Example |

|

(1) Feature-level script alternations |

Advertising campaigns |

Section 3.1 |

PerhaΨ you’re an AΘenian too! |

|

(2) Rescripting of English lexis and chunks |

Media discourse, social media postings, user comments |

Section 4.1 |

εκοτσάμπερ ‘echo chamber’ Γιου νεβερ νοου ‘You never know’ |

|

(3) Trans-scripting that contextualizes double voicing |

User comments |

Section 3.2 Section 4.2 |

Ιβ γιου μπιλίβ δέι αρ τούρκισ γιου μαστ γκόου του Τούρκι ‘If you believe they are Turkish you must go to Turkey’ |

|

(4) Trans-scripting as a resource for language-ideological discourse |

Social media postings, user comments |

Section 3.2 Section 4.2 |

Πλοιζ ράοιτ οιν γκροικ ‘Please write in Greek’ γιου καν βράιτ ολσο ιν γκρικ ‘you can write also in Greek’ |

Type 1 is the microlevel of word composition that draws on an intentional mixing of graphemes from the Greek and Roman script. Here trans-scripting works as an aesthetic resource alongside other forms of visual styling such as typographic mimicry, and its outcomes are rather transparent messages of stereotyped cultural authenticity. The distinctiveness of graphic shape iconizes a distinctiveness of cultural experience, which is marketed to a diffuse international audience. Remarkably, this pattern of trans-scripting seems limited to advertising discourse and does not occur at all in social media interactions.

Type 2 is the inconspicuous rescripting of English lexis and chunks. This type of trans-scripting can be seen as part of a loanword integration process, whereby conventionalization in usage leads to vernacular graphemic integration. As online writers cast a loanword or phrase into their familiar native script, they selectively transgress the boundaries that separate languages and scripts and indicate their degree of familiarity with the respective item. This observation aligns with the ‘ordinariness’ of translanguaging (Lee and Dovchin 2020): trans-scripting is part of inconspicuous language contact, which in turn is encased within contemporary globalized media culture. Instances of micro-variation such as the word ‘site’ (Example 4) are revealing of participants’ ability to co-activate their knowledge about Greek and English spelling. Not bothering to shift the keyboard layout is the decisive material aspect that mobilizes translanguaging knowledge in this case.

Type 3 represents trans-scripting that contextualizes double voicing. It expresses social positionalities and recognizable cultural frames, which interact with the current topical frame. A major motif of such trans-scripting is a joyful blend of discourse frames, whereby commenters partake simultaneously in a Greek discourse and in global cultural flows, for example remixing references from digital media culture with Greek countryside imaginaries. Such incongruence is arguably entertaining, and trans-scripting is a major resource for this.

Type 4 features trans-scripting as a resource for language-ideological debate and commentary. We document this when people cross scripts purposefully to counter and protest others’ non-canonical combinations (notably in the Greeklish debate, case study 1) and when people purposefully rescript their English to comment on others’ language choices (case study 2). It is also evident in more implicit forms of metapragmatic critique including stylized voicings that expose others’ ways of using English, and thereby eventually reaffirm language/script bonds and standard language ideologies.

The analysis has uncovered how these four types of trans-scripting relate to recurrent choices of linguistic forms. However, this mapping is not always straightforward, and different patterns of trans-scripting may draw on a range of linguistic resources. For example, rescripted English lexis is most often vernacular Anglicisms with no additional contextualization force; yet some rescripted tokens are motivated by reporting direct speech, voicing pronunciation, or blending cultural frames (see Example 9). Likewise, rescripted English chunks are often part of vernacular mixed styles that occur in Reddit conversations (Examples 5, 6) but also deployed in parodic double-voicing (Example 8).

Regarding the positionalities and stances indexed by Romanized Greek and Hellenized English, the analysis uncovers shared ambiguities as much as differences between the two. These differences are motivated by diachronic techno-social developments as much as by language ideologies. Romanized Greek (‘Greeklish’) was widely used in the early stage of its compulsory deployment on the Internet, and early forms of Romanized Greek were often associated with cosmopolitanism and mobility (see Section 1). The advent of the Greek script as afforded by Unicode turned Greeklish into an ideologized choice, either as a code that can express opposition to the default expectations of using the Greek script or, conversely, as a resource for stigmatizing non-canonical script choice and reinforcing inherited language-script configurations (see Section 3.2). On Reddit, too, the use of ‘Greeklish’ is often met by criticism and rejection by other participants. Evident here is a sharp language-ideological boundary between ‘our’ language, imagined as an inseparable bond of language and script, and ‘foreign’ language influences that are positioned as a threat (Moschonas 2009).

Hellenized English (‘Engreek’), on the other hand, is not met by the same criticism and resistance. It is not perceived as threatening the ideological unity of Greek language and script, as it does not affect the written form of Greek itself but rather that of English segments. Our case studies reveal a wide range of usage and pragmatic functions (Table 3, types 2 to 4), including collaborative language play, recontextualized direct speech, and metalinguistic critique. Greek-scripted English can signal light-hearted affiliation and in-group playfulness while participants engage in transcultural exchanges and cultural identity narratives. It can be used to mimic (Deumert 2018) others’ lacking skills in the English language; or to expose an inappropriate choice of English by others. Returning to the notion of a ‘transformative’ potential of translanguaging (Lee and Li 2020), Greek-scripted English links this potential to the poetic function of language. It provides a way to experiment with the elasticity of assumed language boundaries and can yield unexpected and entertaining associations between local culture and global semiotic flows (Section 4.2). Some rescripted comments have a tongue-in-cheek quality that leaves ambiguous whether the writer identifies with or disidentifies from the evoked person types and cultural stereotypes. In the Reddit case study, these little episodes are encased in the forum’s discourse culture, where language play is highly valued, and community members spontaneously collaborate in producing impromptu joyful exchanges. However, these playful appropriations of English, too, nonetheless presuppose language-ideological fixities of ‘normal Greek’ and ‘native English’, against which scriptal reconfigurations meet cultural hybridity to produce entertaining moments.

Our findings suggest that the pragmatic and social meanings of scriptal fluidity are context-dependent and entangled with historical and contemporary language ideologies and metalinguistic discourses. What emerges from this study is the need for a systematic and critical approach to scriptal hybridity within translanguaging studies, which accounts for the various types of pragmatic and ideological work scriptal practices can accomplish. As digital communication continues to evolve and hybrid scriptal practices proliferate across platforms and communities, understanding trans-scripting becomes crucial for unpacking how language users negotiate identity, belonging, and power in contemporary networked societies.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to two anonymous reviewers and the Special Issue editors for their feedback and support. Androutsopoulos’s work was partially supported by the international scientific network DiLCo (“Digital Language Variation in Context”), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg under the German Excellence Strategy. Androutsopoulos expresses his thanks to Jenia Yudytska for data retrieval. Spilioti expresses her thanks to the School of English, Communication and Philosophy, Cardiff University, who supported research for this paper with a research leave in spring semester 2024–2025.

Funder Name: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, Funder Id:, Grant Number: Z5-V2-003:TN 2021 DiL.Co;Androutsopoulos

References

Akbar, Rahima, Taqi Hanan & Taiba Sadiq. 2020. Arabizi in Kuwait: An emerging case of digraphia. Language & Communication 74. 204–216.10.1016/j.langcom.2020.07.004Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 1998. Ορθογραφική ποικιλότητα στο ελληνικό ηλεκτρονικό ταχυδρομείο: μια πρώτη προσέγγιση [Orthographic variation in Greek e-mail: a first approach]. Glossa 46. 49–67.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2009. ‘Greeklish’: Transliteration practice and discourse in a setting of computer-mediated digraphia. In Alexandra Georgakopoulou & Michael Silk (eds.), Standard languages and language standards: Greek, past and present, 221–249. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2010. Localising the global on the participatory web. In Nikolas Coupland (ed.), Handbook of language and globalization, 203–231. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9781444324068.ch9Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2015. Networked multilingualism: Some language practices on Facebook and their implications. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(2). 185–205.10.1177/1367006913489198Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2020. Trans-scripting as a multilingual practice: The case of Hellenised English. International Journal of Multilingualism 17(3). 286–308.10.1080/14790718.2020.1766053Search in Google Scholar

ATHairport. 2014. Perhaps you’re an Athenian too! YouTube video, 13 May 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXPcMhu4rAA (accessed 26 July 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1971. Probleme der Poetik Dostoevkijs. München: Hanser.Search in Google Scholar

Bhatt, Ibrar. 2023. Postdigital possibilities in applied linguistics. Postdigital Science and Education 6. 743–755.10.1007/s42438-023-00427-3Search in Google Scholar

Bunčić, Daniel, Sandra L. Lippert & Achim Rabus (eds.). 2016. Biscriptality: A sociolinguistic typology. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag.10.33675/978-3-8253-7619-2Search in Google Scholar

Coulmas, Florian. 2003. Writing systems: An introduction to their linguistic analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139164597Search in Google Scholar

Cramer, Florian. 2014. What is ‘Post-Digital’? APRJA 3(1). https://aprja.net/article/view/116068 (accessed 26 July 2025).10.7146/aprja.v3i1.116068Search in Google Scholar

Dale, Ian R. H. 1980. Digraphia. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 26. 5–14.10.1515/ijsl.1980.26.5Search in Google Scholar

Deumert, Ana. 2018. Mimesis and mimicry in language – Creativity and aesthetics as the performance of (dis-)semblances. Language Sciences 65. 9–17.10.1016/j.langsci.2017.03.009Search in Google Scholar

Dovchin, Sender. 2015. Language, multiple authenticities and social media: The online language practices of university students in Mongolia. Journal of Sociolinguistics 19(4). 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12134 (accessed 26 July 2025).10.1111/josl.12134Search in Google Scholar

Ferguson, Charles A. 1959. Diglossia. Word 15(2). 325–340.10.1080/00437956.1959.11659702Search in Google Scholar

García, Ofelia & Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137385765_4Search in Google Scholar

Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. 1997. Self-presentation and interactional alliances in e-mail discourse: The style- and code-switches of Greek messages. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 7(2). 141–164.10.1111/j.1473-4192.1997.tb00112.xSearch in Google Scholar

George, Rachel. 2019. Simultaneity and the refusal to choose: The semiotics of Serbian youth identity on Facebook. Language in Society 49(3). 399–423.10.1017/S004740451900099XSearch in Google Scholar

Grivelet, Stéphane. 2001. Introduction. Digraphia: Writing Systems and Society [Special issue]. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 150. 1–10.10.1515/ijsl.2001.037Search in Google Scholar

Gumperz, John J. 1982. Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511611834Search in Google Scholar

Hastings, Adi & Paul Manning. 2004. Introduction: Acts of alterity. Language and Communication 24. 291–311.10.1016/j.langcom.2004.07.001Search in Google Scholar

Heller, Monica. 2014. The commodification of authenticity. In Veronica Lacoste, Jakob Leimgruber & Thiemo Breyer (eds.), Indexing authenticity: Sociolinguistic perspectives (Linguae & litterae 39), 112–136. Berlin, München & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110347012.136Search in Google Scholar

Ivkovic, Dejan. 2013. Pragmatics meets ideology: Digraphia and orthographic practices in Serbian online news forums. Journal of Language and Politics 12(3). 335–356.10.1075/jlp.12.3.02ivkSearch in Google Scholar

Jaffe, Alexandra, Jannis Androutsopoulos, Mark Sebba & Sally Johnson (eds.). 2012. Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power (Language and social processes 3). Boston & Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511038Search in Google Scholar

Jaworska, Sylvia. 2014. Playful language alternation in an online discussion forum: The example of digital code plays. Journal of Pragmatics 71. 56–68.10.1016/j.pragma.2014.07.009Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Sally. 2002. On the origin of linguistic norms: Orthography, ideology and the first constitutional challenge to the 1996 reform of German. Language in Society 31(4). 549–576.10.1017/S0047404502314039Search in Google Scholar

Koutsogiannis, Dimitris & Bessie Mitsikopoulou. 2003. Greeklish and Greekness: Trends and discourses of “glocalness”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00358.x (accessed 26 July 2025).10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00358.xSearch in Google Scholar

Kuvaluz-Onal, Derya & Camilla Vasquez. 2018. “Thanks, shokran, gracias”: Translingual practices in a Facebook group. Language Learning and Technology 22(1). 240–255.10.64152/10125/44589Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Carmen & David Barton. 2011. Constructing glocal identities through multilingual writing practices on Flickr.com. International Multilingual Research Journal 5(1). 39–59.10.1080/19313152.2011.541331Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Jerry Won & Sender Dovchin (eds.). 2020. Translinguistics: Negotiating innovation and ordinariness. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429449918Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Tong King & Li, Wei. 2020. Translanguaging and momentarity in social interaction. In Anna De Fina & Alexandra Georgakopoulou (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of discourse studies, 394–416. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108348195.019Search in Google Scholar

Li, Wei & Hua Zhu. 2019. Tranßcripting: Playful subversion with Chinese characters. International Journal of Multilingualism 16(2). 145–161.10.1080/14790718.2019.1575834Search in Google Scholar

Lillis, Theresa. 2013. The sociolinguistics of writing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748637492Search in Google Scholar

Makri-Tsilipakou, Marianthi. 1999. Q: Do you use foreign words when you speak? ((in Greek)). A: Never ((laughter)). In Anastasios-Fivos Christidis (ed.), ‘Strong’ and ‘weak’ languages in the European Union: Aspects of linguistic hegemonism, 448–457. Thessaloniki: Centre for the Greek Language.Search in Google Scholar

Meletis, Dimitrios. 2021. “Is your font racist?” Metapragmatic online discourses on the use of typographic mimicry and its appropriateness. Social Semiotics 33(5). 1046–1068.10.1080/10350330.2021.1989296Search in Google Scholar

Moschonas, Spiros. 2009. ‘Language Issues’ after the ‘Language Question’: On the modern standards of Standard Modern Greek. In Alexandra Georgakopoulou & Michael Silk (eds.), Standard languages and language standards: Greek, past and present, 293–320. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Mouresioti, Evgenia & Maria Terkourafi. 2024. Othering through spelling: Greek native speakers’ attitudes toward Greeklish and Engreek in digitally-mediated communication. In Vojkan Stojičić, Ana Elaković-Nenadović & Martha Lampropoulou (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Greek Linguistics, vol. 2, 389–415. Belgrade: University of Belgrade.10.18485/icgl.2024.15.2.ch23Search in Google Scholar

Palfreyman, David & Muhamed al Khalil. 2003. “A funky language for teenz to use”: Representing Gulf Arabic in instant messaging. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00355.x (accessed 26 July 2025).10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00355.xSearch in Google Scholar

Robertson, Wesley C. 2022. ‘Ojcfn gokko shiyo! [Let’s pretend to be old men!]’: Contested graphic ideologies in Japanese online language play. Japanese Studies 42(1). 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2021.2020087 (accessed 26 July 2025).10.1080/10371397.2021.2020087Search in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 1998. Phonology meets ideology: The meaning of orthographic practices in British Creole. Language Problems and Language Planning 22(1). 19–47.10.1075/lplp.22.1.02sebSearch in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 2007. Spelling and society: The culture and politics of orthography around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486739Search in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 2012. Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power. In Alexandra Jaffe, Jannis Androutsopoulos, Mark Sebba & Sally Johnson (eds.), Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power, 1–20. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511038.1Search in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza. 2009. Graphemic representation of text-messaging. Pragmatics 19(3). 393–412.10.1075/prag.19.3.05spiSearch in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza. 2014. Greek-alphabet English: Vernacular transliterations of English in social media. In Bettina O’Rourke, Niamh Bermingham & Stephen Brennan (eds.), Opening new lines of communication in applied linguistics: Proceedings of the 46th Meeting of the British Association for Applied Linguistics, 435–446. London: Scitsiugnil Press.Search in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza. 2019. From transliteration to trans-scripting: Creativity and multilingual writing on the internet. Discourse, Context and Media 29. Article number: 100294.10.1016/j.dcm.2019.03.001Search in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza. 2020. The weirding of English, trans-scripting and humour in digital communication. World Englishes 39(1). 106–118.10.1111/weng.12450Search in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza & Korina Giaxoglou. 2021. Translation and trans-scripting: Languaging practices in the city of Aθens. In Tong King Lee (ed.), The Routledge handbook of translation and the city, 278–293. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429436468-21Search in Google Scholar

Spitzmüller, Jürgen. 2013. Graphische Variation als soziale Praxis. Eine soziolinguistische Theorie skripturaler‘Sichtbarkeit [Graphic Variation as Social Practice. A Sociolinguistic Theory of Scriptal Visibility]. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110334241Search in Google Scholar

Spitzmüller, Jürgen. 2015. Graphic variation and graphic ideologies: a metapragmatic approach. Social Semiotics 25(2). 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2015.101032310.1080/10350330.2015.1010323Search in Google Scholar

Stöckl, Hartmut. 2005. Typography: Body and dress of a text – A signing mode between language and image. Visual Communication 4(2). 204–214.10.1177/1470357205053403Search in Google Scholar

Tagg, Caroline & Agnieszka Lyons. 2022. Mobile messaging and resourcefulness: A post-digital ethnography. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429031465Search in Google Scholar

Tebaldi, Claudia. 2020. ‘Bad hombres’, ‘aloha snackbar’, and ‘le cuck’: Mock translanguaging and the production of whiteness. In Jerry Won Lee & Sender Dovchin (eds.), Translinguistics: Negotiating innovation and ordinariness, 206–216. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429449918-16Search in Google Scholar

Thurlow, Crispin & Adam Jaworski. 2011. Tourism discourse: Languages and banal globalization. Applied Linguistics Review 2. 285–312.10.1515/9783110239331.285Search in Google Scholar

Unseth, Peter. 2008. The sociolinguistics of script choice: An introduction. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 192. 1–4.10.1515/IJSL.2008.030Search in Google Scholar

Wertheim, Suzanne. 2012. Reclamation, revalorization and re-Tatarization via changing Tatar orthographies. In Alexandra Jaffe, Jannis Androutsopoulos, Mark Sebba & Sally Johnson (eds.), Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power, 65–101. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511038.65Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelei

- Introduction: multilingual, multilectal, and multiscriptal writing

- Norms at play

- Professional identities and cosmopolitan personas: Latin as cultural capital in Scandinavian rune inscribers’ signatures

- How planning a national language cured the Croatian nationalists of xenolingohassen

- Orthographic practices and social meanings: writing Istro-Romanian, an endangered language in Croatia

- The politics of writing in Iran

- What you see is what you get? Challenging the primacy of the visual in writing research

- Scripts in interaction: fixity and fluidity in Greek trans-scripting practices

- Multilingualism, digital translingua and linguistic repertoires among migrant youth in virtual communities

- Fuhgeddaboudit shugah! Social meanings of the New York City dialect in the semiotic landscape

- Miscellaneous

- An interview with Björn H. Jernudd

- An interview with Deborah Cameron

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelei

- Introduction: multilingual, multilectal, and multiscriptal writing

- Norms at play

- Professional identities and cosmopolitan personas: Latin as cultural capital in Scandinavian rune inscribers’ signatures

- How planning a national language cured the Croatian nationalists of xenolingohassen

- Orthographic practices and social meanings: writing Istro-Romanian, an endangered language in Croatia

- The politics of writing in Iran

- What you see is what you get? Challenging the primacy of the visual in writing research

- Scripts in interaction: fixity and fluidity in Greek trans-scripting practices

- Multilingualism, digital translingua and linguistic repertoires among migrant youth in virtual communities

- Fuhgeddaboudit shugah! Social meanings of the New York City dialect in the semiotic landscape

- Miscellaneous

- An interview with Björn H. Jernudd

- An interview with Deborah Cameron