Abstract

Written culture in medieval Scandinavia featured the concurrent use of different languages–Latin and the local vernaculars–and two scripts–the Roman script and the runic script. Although Latin carried substantial cultural capital as the cosmopolitan language of religious and juridical authorities, diplomacy, and high literate culture, the vernacular runic written tradition had already been established for many centuries and continued to be used alongside Latin and the Roman script. This coexistence was particularly evident in the epigraphic landscape and resulted in several inscriptions that mixed both languages and scripts.

This article explores the choices of language and script made by two medieval inscribers who, despite being primarily trained within a vernacular runic tradition, used Latin and/or the Roman script, particularly in their signatures. The study argues that these inscribers leveraged the symbolic value of Latin and the Roman script to project a distinctive professional identity in response to a changing linguistic market in which these linguistic resources were gaining value. The analysis also illustrates how these inscribers’ highly individual practices resulted from a negotiation of different linguistic norms and highlights a tension between their level of literacy and their efforts to display cultural capital. Finally, the article argues that the use of Latin and the Roman script was motivated more by their symbolic value than by purely communicative necessity, offering parallels to modern instances of language commodification.

1 Introduction

Recent research on historical multilingual contexts has increasingly employed and adapted theoretical concepts and methodologies from modern sociolinguistics. This trend both showcases the increased analytical depth that interdisciplinary approaches can bring to historical studies (e.g. Baglioni and Tribulato 2015; Krogull and Rutten 2025; Mullen 2013; Mullen and James 2012; Palumbo 2025; Rutten et al. 2017; Steele 2018; Torrens Álvarez and Tuten 2022), and simultaneously reveals that historical multilingualism has often been neglected in investigations of related phenomena that have perhaps been too hastily labeled as solely or predominantly “modern” (see Pavlenko and Mullen 2015; Pavlenko 2018: 154–156; Pavlenko 2023; and Rutten 2016 for examples of such critique).

Attempts at cross-fertilization between fields, such as modern and historical sociolinguistics, which have widely different access to textual and contextual data, undoubtedly raise methodological issues and the risk of oversimplification and presentism. At the same time, the application of theoretical frameworks to explain the social significance of modern multilingual and multiscriptal practices can provide greater explanatory power in investigations of past writing practices if such analyses are grounded in historical and philological awareness of the specificities of the written records examined. In certain subfields of historical linguistic inquiry, such as the study of medieval Scandinavian epigraphic records, bridging modern sociolinguistics and philology can also help foreground the social aspects of such writing practices, in addition to traditionally prioritized linguistic or literacy-related observations (see e.g. Bianchi 2010 and 2016 for applications of sociolinguistic and sociosemiotic frameworks within Scandinavian runic epigraphy).

In this paper, I investigate the choices of language and script made by two inscribers active in medieval Scandinavia, namely Harald and Jacob the Red, also known as magister Haraldus and magister Iacobus Rufus. These craftsmen were trained within a vernacular tradition–thus proficient in the local Scandinavian languages and the runic alphabet–but also employed, to varying degrees and with varying success, Latin and the Roman script in their work. In this analysis, I bridge modern sociolinguistics and the study of medieval written sources by relating these craftsmen’s bilingual and biscriptal practices to the concepts of professional identity (Heggen 2008), cultural capital, and the linguistic market (Bourdieu 1977, 1986) as well as to investigations of the commodification of languages and scripts in modern societies.

I will primarily focus on these two inscribers who, while producing bilingual and biscriptal texts, chose to employ Latin and/or the Roman script for their own names and signatures. Given the strong connection between one’s own name–including its written representation–and identity (Aldrin 2016), I hypothesize that the semiotic resources employed in the signatures may be particularly revealing of the self-image they sought to convey (see Holmqvist 2018, 2020a, 2020b where a combination of cognitive theory and practice theory is employed to study expressions of the self in medieval runic graffiti). I will argue that the writing practices adopted by these inscribers may be interpreted as part of a process of developing and projecting their professional identity, in response to a changing linguistic market characterized by the introduction of a new language and script–Latin and the Roman script–into a context where the vernacular and the runes had long been the primary, if not sole, linguistic resources. Within this context, I will also argue that the choice to use Latin and Roman letters was motivated more by their symbolic value than by purely communicative necessity, offering parallels to modern instances of language commodification.

2 Diglossia, digraphia, or fluid writing practices in medieval Scandinavia

Written texts in medieval Scandinavia (c. 1050–1500) featured the concurrent use of different languages–Latin and the local vernaculars–and two scripts–the Roman script and the runic script. Runes were employed as a writing system in Scandinavia and in other Germanic-speaking areas from at least the first century CE. They were used on a variety of material supports and for a variety of text types and purposes, but were limited to the production of epigraphs, i.e. inscriptions. Although Scandinavians undoubtedly were acquainted with Latin and the Roman script during the Roman Iron Age and the Early Middle Ages, Latin written culture spread relatively late in Scandinavia, with the first fragmentary attestations of locally produced writing in Latin and the Roman script–either on parchment or in inscriptions–stemming from the eleventh century.

Although Latin carried substantial cultural capital as the cosmopolitan language of religious and juridical authorities, diplomacy, and high literate culture, the vernacular runic written tradition was not abandoned once Latin and the Roman script were introduced but endured for several centuries, in some areas of Scandinavia until the fifteenth century. This gave rise to a long coexistence between these written traditions, and a period of societal–and in many cases also individual–bilingualism and biscriptality. The production of manuscripts was always dominated by the use of the Roman script, with a few exceptions being sporadic examples of manuscripts in runes and the use of single runes or short sequences on parchment. On the other hand, the epigraphic landscape, i.e. the production and display of inscriptions, was more varied, as both scripts and languages were used side by side (e.g. Blennow and Palumbo 2021, 2022; Blennow et al. 2022; Bollaert 2022; Imer 2021; Kleivane 2021). Although not all combinations of script and language appeared equally often, medieval inscriptions include instances of runes used for both Latin and the vernacular (Knirk 1998; Palumbo 2022; Steenholt Olesen 2021), and of the Roman script employed for both languages as well. This sphere of coexistence led to influence between different epigraphic practices as well as the production of inscriptions displaying both languages and scripts, demonstrating various types of code- and script-switching (e.g. Källström 2018; Palumbo 2023, 2025).

Although the general nature of the relationship between Latin and the vernacular in the Middle Ages can be described as diglossic, the strict and stable separation of domains implied by this concept has led various scholars to problematize its applicability to historical contexts (e.g. Adams 2003: 539–541; Mullen 2012: 24–25; Petrucci 2010: 23; Rutten 2016). While providing a useful categorization of a linguistic situation from a certain level of societal abstraction, diglossia at the same time risks making invisible more variable and fluid language uses, showcased for instance in linguistically hybrid documents (see e.g. Torrens-Álvarez and Tuten 2022). The same criticism can be directed at the concept of digraphia used to describe the relation between different scripts, for example, runes and the Roman script in medieval Scandinavia (Bollaert 2022; Palumbo and Tamošiūnaité forthcoming).

It is this kind of more fluid or even ad hoc solution that we see in several bilingual and biscriptal Scandinavian inscriptions, including those by the inscribers studied in this paper. Instead of a stable separation of domains, we can observe negotiations of the social functions linked to different languages and scripts in order to achieve certain communicative and social goals. In a recent article, Torrens-Álvarez and Tuten (2022: 730) aptly describe the process of choosing between the vernacular–Romance in medieval Castile in their case–and Latin as the result of a “tension between different notions of indexical value”, i.e. a tension between factors favouring Latin and those favouring the vernacular. Among these factors are sociocultural, ideological, and economic considerations–just as in modern multilingual societies–which at the same time have to be balanced with the writers’ and expected readers’ literacy skills.

In medieval Scandinavia as well, the reasons for choosing Latin and the Roman alphabet were multifaceted (see e.g. Palumbo 2025). Here, I explore the role that the perceived cultural capital of these varieties played in shaping different craftsmen’s linguistic choices. In the next section, I therefore relate the concepts of professional identity, cultural capital, and linguistic market to the literacy situation of medieval Scandinavia and the role of rune carvers.

3 Medieval professional identities in a changing linguistic market

Professional identity can be defined as the individual self-identification as a professional within a collective identity linked to a given line of work. It is in fact generally considered separate from the collective identity shared by the members of a whole profession–what could be called professionalism. As Heggen (2008: 323–324) points out, members of a profession who share a collective identity do not necessarily share a common practice. This means that although they might have a certain set of values in common, or a shared symbolism (Heggen 2008: 323), the collective identity of professionalism allows individuals to develop their own professional style (Hansbøl and Krejsler 2004: 31), i.e. they can adopt different ways of acting which set them apart from other members of the same profession. Individual professional identities develop over time and are not solely connected to the development of certain qualifications or professional skills. Rather, they develop through participation, socialization, and norm negotiation in certain relevant communities of practice (Heggen 2008: 322). From this point of view, the development of qualifications and skills and the development of one’s professionalism and professional identity occur together: acquiring new qualifications is seen as an activity which changes one’s identity.

The relevance of this perspective for the medieval Scandinavian situation is linked to the spread of a new written language and script among members of the professions to which the inscribers and craftsmen studied here belonged. Such an important change in these professions’ practices as a shift of both language and script entailed, on the one hand, an opportunity and a spur to acquire, to various degrees, new skills and proficiencies. On the other hand, such a shift, I argue, would have entailed both a reshaping of the collective identity shared by these professionals–the meaning of their professionalism–and the possibility, or even the necessity, of redefining one’s individual professional identity.

The effects of such developments in the broader written culture of medieval Scandinavia are particularly interesting to examine with regard to those inscribers who were already schooled and active within a vernacular runic epigraphic tradition. The question is what kind of response they made to these radical changes, and what reasons they may have had to acquire new proficiencies, adapt their personal style, and evolve their professional identity.

As I will argue later in the article, the linguistic adaptations employed by these craftsmen can partly be interpreted in the context of a changing linguistic market in medieval Scandinavia and as motivated by a desire to acquire and display cultural capital that could position them more advantageously within the emerging system of cultural and linguistic values shaped by the introduction and spread of Latin and the Roman script.

Central to this interpretation are considerations regarding linguistic practices and the market, an area of research that has drawn increasing interest from sociolinguists in recent years (see Kelly-Holmes 2016 on the development of sociolinguistic approaches to the market, as well as Heller and Duchêne 2016). Foundational for much of this research is Bourdieu’s concept of linguistic capital which, as a form of cultural capital, can be deployed in the market and exchanged for other forms of material capital (Bourdieu 1977, 1986). Linguistic practices, therefore, cannot be separated from the value attached to them nor “from their links to all kinds of social activities and to the circulation of resources of all kinds that social order mediates” (Heller 2010: 102). The perceived value of a language and that of its speakers are also co-constructed: while a “language is worth what those who speak it are worth” (Bourdieu 1977: 652), the worth of speakers and writers is assessed on the basis of their linguistic choices (Heller 2010: 102). This implies that the value attributed to different linguistic practices informs, to varying degrees, the choices of speakers and writers, who can act differently “on the basis of there being more or less chance of profit from these choices” (Kelly-Holmes 2016: 161).

Linguistic competence functions as linguistic capital depending on the market in which it is used and the value attributed to it, assessed in relation to the hierarchical relations among different variants of linguistic competence (Bourdieu 1977: 654). Cultural capital in general derives its value from its scarcity–from being unequally distributed–and from the competition to acquire it. Bourdieu calls this the “symbolic logic of distinction” (Bourdieu 1986: 18) or the “profit of distinctiveness” (Bourdieu 1977: 654), namely that “any given cultural competence (e.g., being able to read in a world of illiterates) derives a scarcity value from its position in the distribution of cultural capital and yields profits of distinction for its owner” (Bourdieu 1986: 18–19). Languages–and scripts–can thus function as markers of distinction.

Bourdieu’s example of being literate in a world of illiterates is directly relevant to medieval contexts, including that of Scandinavia. At the outset of the spread of Latin in the region, literacy in Latin and the Roman script was closely tied to the upper echelons of society. Literacy in the vernaculars and runes was certainly more widespread, as attested both by the higher numbers of inscriptions in these varieties and by the involvement of other social groups in the production of inscriptions, particularly those intended for pragmatic, everyday use. By contrast, active knowledge of Latin and the Roman script was far more restricted. Latin also entered Scandinavia imbued with substantial social value, derived by its “global” use in high-status and authoritative domains such as religion, law, and diplomacy. In a still scarcely Latinized and largely illiterate society, knowledge of Latin and the Roman script would have been seen as a valuable asset, acquirable either directly or by proxy (see Bourdieu 1986: 20). For example, an inscriber might develop some degree of literacy as a form of embodied cultural capital, while a wealthy commissioner could acquire objectified cultural capital in the form of commemorative inscriptions in Latin and/or the Roman script.

In modern societies, economic imperatives have been widely observed to shape choices of language and script in public space. For example, Ben-Rafael (2009) and Ben-Rafael et al. (2006), focusing on linguistic landscapes in modern urban centres, note how various actors compete for the attention of potential clients, seek to project advantageous images of themselves, and strive to enhance the appeal and impact of their signs (Ben-Rafael 2009: 45–46; Ben-Rafael et al. 2006: 9–10). Scholars have also argued that language increasingly functions as an economic resource in late-capitalist and globalized societies (Heller 2010; Heller and Duchêne 2016). This development includes processes of commodification of, for instance, minority languages or scripts–often used to signal authenticity in the context of marketing (e.g. Leeman and Modan 2009; Kelly-Holmes 2014; Pietikäinen et al. 2019; see also Gorter and Cenoz 2024: 218–221 for an overview of recent case studies)–as well as historical scripts used in tourism-related contexts in modern societies (Oštarić 2018 on Glagolitic script in Croatia, as well as Freund and Ljosland 2017 and Ljosland 2014 on the modern uses of Scandinavian runes in Northern Scotland; see also Petersson 2010), and English utilized as a global commodity, indexing internationalism and modernity (see e.g. Huebner 2006; Cameron 2012; Kelly-Holmes 2014).

While the medieval context differs in many respects from modern societies, the relationship between language and the market as well as the use of languages and scripts as resources in a symbolic economy nevertheless appear relevant. This is partly because medieval inscribers and craftsmen were also commercial actors in a market–although on a much smaller scale–and partly because the use of linguistic resources to pursue social, cultural, and economic goals is well attested in historical contexts. I thus hypothesize that medieval inscribers were likewise interested in “marketing” themselves, and that changes in their practice in the Scandinavian context may be seen, at least in part, as an adaptive response to a shifting linguistic market in which new forms of cultural capital were gaining value. Within this context, we can also observe a negotiation of linguistic and textual norms tied to different communities of practice, which provides the backdrop for these inscribers’ own creative strategies and personal styles.

4 Names, signatures, and professional identities

In the following section, I will examine the work of the two medieval Scandinavian inscribers, Harald and Jacob the Red, with particular attention to the choice of language and script in their own signatures, compared to the linguistic resources used in other parts of their inscriptions. As previously mentioned, this focus is motivated by the strong connection that exists between one’s own name and identity (Aldrin 2016). In the case of professional craftsmen, signatures can be expected to reflect the kind of professional identity they sought to project, and how they aimed to market themselves and their work. We can also assume that the choices made in the signatures are more directly attributable to the inscribers, whereas other parts of the texts may reflect greater influence from external actors, for example the commissioners.

In their work, these inscribers draw on the Latin written tradition, using Latin, the Roman script, or both alongside sections written in the vernacular and/or runes. They were not selected because their language and script choices are particularly representative of the period. On the contrary, their bilingual and biscriptal practices stand out in the Scandinavian context in which they were active. What they have in common is that they both appear to have received their primary training within a vernacular runic writing tradition while also acquiring some proficiency in Latin and the Roman script, which they employed in their signatures.

An examination of their practice reveals a negotiation of linguistic norms that may reflect different conceptions of professionalism in relation to language and script use, while also highlighting a tension between their level of literacy and their efforts to display cultural capital. Within this negotiation, these inscribers demonstrate highly individual professional practices.

4.1 Harald the stonemason, aka Haraldus magister

Haraldær stenmæstari, or Harald the stonemason, was a craftsman active in a rather well-delimited area of the western Swedish province of Västergötland in the early thirteenth century. We know of five epitaphs that include his signature, in addition to four epitaphs that, with varying degrees of confidence, have been attributed to him based on palaeographic similarities or the simultaneous use of both runes and Roman letters. All the inscriptions signed by him are bilingual and biscriptal (Blennow 2016: 235–237; Blennow and Palumbo 2021, 2022; Källström 2018).

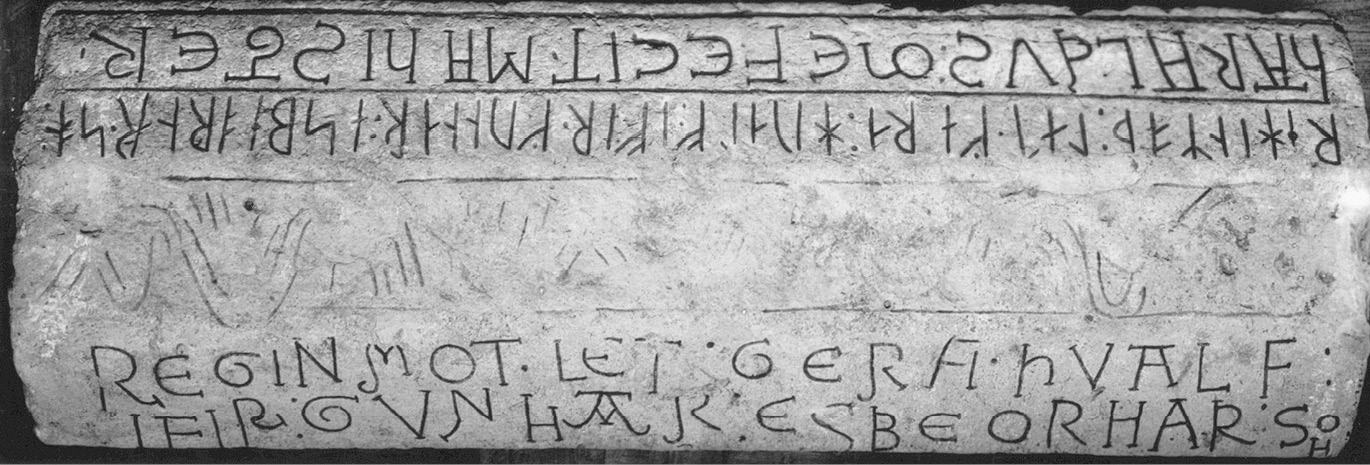

Bilingual and biscriptal funerary monument by Master Harald. Ugglum churchyard, Sweden. Photo: Statens Historiska Museer. Public domain.

In the extracts below (Examples 1–3), a transliteration of runes is given in bold and a transcription of the Roman letters is given in small capitals, in addition to a version with a normalized spelling and a translation into English.[1]

[1] Valstad (Vg Blennow 2016;187; Valstad 1)

alexander g---n · n gvnvr harạḷḍ harraldær

Alexander … Gunnur. Harald. Haraldær.

[Alexander … Gunnur. Harald. Harald.]

[2] Södra Ving churchyard (Vg 165; Södra Ving 1)

+ botilder : let : gera : hvalf : denna : ifir : sven : devṛṃ[o]son : ave : maria : gratia botildær : læt : gæra : huaḷf : þænna : ifir : suen : dyrmoson : haraldær : stenmæstari : gærþi:

Bothildær læt gæra hvalf þænna yfir Sven Dyrmoðsson. Ave Maria gratia. Bothildær læt gæra hvalf þænna yfir Sven Dyrmoðsson. Haraldær stenmæstari gærði.

[Bothild had this monument made over Sven Dyrmodson. Hail, Mary, (full of) grace. Bothild had this monument made over Sven Dyrmodson. Harald the stonemason made.][2]

[3] Ugglum churchyard (Vg 95; Ugglum 1; Figure 1)

reginmot · let · gera · hvalf : ifir : gvnnar : esbeornar : son rehinmoþ : læt · gæra : hualf : ifir · gunnar : æsbeorna͡r · so͡n : haraldvs : me : fecit : mahister

Reginmoð læt gæra hvalf yfir Gunnar Æsbiornar son. Reginmoð læt gæra hvalf yfir Gunnar Æsbiornar son. Haraldus me fecit magister.

[Reginmod had this monument made over Gunnar Äsbjörn’s son. Reginmod had this monument made over Gunnar Äsbjörn’s son. Master Harald made me.]

Harald’s signed epitaphs feature partially overlapping texts in different languages and scripts, where the same content–typically the sequence concerning the commissioner and the commemorated–is repeated word for word in runes and in the Roman script, while other contents appear only once in a single language and script. Despite the small size of the corpus, his signatures display a certain degree of variation. The inscription from Valstad (Example 1), which may be Harald’s oldest preserved work (see Blennow 2016: 190), is the only instance in which he repeats his name twice, once in each script. The name in runes is clearly inscribed in the vernacular, as indicated by the Old Swedish ending -ær, while the Roman-script version is more ambiguous, lacking both the vernacular ending and the ending -us typical of Latinized forms. It is therefore a non-Latinized form, which nevertheless differs from the expected Scandinavian form. In Example 2, he opts to use only the vernacular form of his name–Haraldær–along with the vernacular epithet stenmæstari, ‘stonemason’, both rendered in runes. In three inscriptions, he switches to Latin for his own signature, signing once as Haraldus and twice as Haraldus magister (see Example 3), thereby both Latinizing his name and attributing to himself the title of magister.

The use of Latin for names and signatures is a feature that both inscribers examined here have in common, yet it remains a very uncommon trait among medieval Scandinavian rune carvers. While no comprehensive quantitative analysis of the language used for these inscribers’ names exists, useful overviews of the Swedish and Danish material can be found in Mårtensson (2024) and Steenholt Olesen (2010), respectively. A search in the Scandinavian Runic-Text Database (2020) for the verb form gerði ‘made’–just one of the possible verbs used in signatures–returns over a hundred medieval inscriptions containing signatures with vernacular names. By contrast, a preliminary quantification suggests that only about twenty inscriptions feature Latinized forms of inscribers’ names, including those analyzed here. The use of Haraldus–as well as Iacobus, discussed below–thus appears to be a sociolinguistically marked choice, which would likely have contributed to distinguishing this craftsman’s work in the epigraphic landscape, especially among inscribers who used runes in their inscriptions.

The title magister is also an especially rare epithet among medieval Scandinavian rune carvers. In the Middle Ages, this title had various uses, including signalling the attainment of an academic degree, but also denoting the role of an artist or craftsman. It seems to have become more common in European epigraphy only from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries onward (Favreau et al. 1989: 86). In the medieval Scandinavian runic corpus, magister appears in just eleven inscriptions produced by five individuals (including one uncertain case), two of whom are inscribers studied here: Harald and Jacob the Red. Alongside the uncommon use of a Latinized version of his own name, Harald’s self-designation as magister strengthens the impression that he sought to present himself as part of a professional community of practice that extended beyond the local western Swedish–or even Scandinavian–context, leveraging the cultural capital associated with Latin to project an advantageous portrayal of his professional identity.

It also seems significant that in three inscriptions (e.g. in Example 3), Harald’s own signature is the only content for which Latin is used, while the rest is in Old Swedish. It is conceivable that he chose Latin to address a somewhat different audience than those who could read Old Swedish. However, it seems plausible that readers literate in the Roman script would have been able to understand a vernacular version of the signature, just as they could read the rest of the content of the epitaph inscribed in Old Swedish and Roman letters. I therefore argue that Harald’s choice of Latin was less about practical communication and more about showcasing his linguistic proficiency and the cultural capital it conveyed.

Theoretically, one could also envision the opposite scenario, namely that Harald was primarily trained in Latin and the Roman script and used the vernacular and runes to signal a more “local” identity. However, several observations clearly speak against such a hypothesis.

The first indication of this is the fact that he includes his name in his funerary inscriptions. While signing commemorative epitaphs was a common practice in the earlier Viking-Age runic tradition (see e.g. Källström 2007), signatures were virtually absent from medieval funerary inscriptions in the Roman script.

Second, the wording of the epitaph continues the Viking-Age runic textual tradition, in which the most common pattern of commemoration consisted of the name of the commissioner, followed by a verb and the name of the commemorated, often with an indication of the type of relationship between the two. An example of this formula can be seen in Example 3 above: “Reginmod had this monument made over Gunnar Äsbjörn’s son”. Additionally, Harald is the only known author of biscriptal epitaphs who replicates the same commemorative formula in the runic and the Roman scripts, rather than producing different texts in each script. This may suggest that Harald’s competence in Latin was limited, at least with regard to the Latin-language commemorative repertoire (Palumbo 2025).

Third, several details of his work in Latin and in the Roman script suggest a lower level of proficiency compared to that demonstrated in the vernacular runic parts. As previously noted (e.g. Källström 2018; Palumbo 2022; Spurkland 1998), the epithet magister is twice spelled mahister (Valtorp I and Vg95/Ugglum in Example 3), most likely influenced by the common use of the rune <h> for the fricative allophone of /g/ in intervocalic position (cf. the name rehinmoþ for Reginmoð in the same text). The same phenomenon is attested in another inscription (Vg 146), where felaga ‘wife’ is spelled felaha and felahạ. In the same inscription, his Latinized name is truncated as haraldv. The spellings felaha and haraldv also occur in his Roman-script inscription from Valtorp (Valtorp I). Compared to his use of runes, Harald’s inscriptions in Roman letters exhibit a noticeably less regular ductus (the manner in which letters are inscribed). Other examples of irregular or problematic spellings can be found in works attributed to him as well (e.g. Blennow 2016: 193–198).

These observations indicate that Harald was much more accustomed to the vernacular runic tradition, yet also experimented with new linguistic resources, particularly in his signature, in an effort to project a dual professional identity that engaged with different cultural practices.

4.2 Jacob the Red, aka magister Iacobus Rufus

The second case study concerns a Danish craftsman who produced several beautifully inscribed censers, namely Jakob Røþ, ‘Jacob the Red’, or Iacobus Rufus. A total of twelve inscribed censers are known, one of which is now lost, all dated to the first half of the thirteenth century. Most were found in churches in the region of Funen and share physical and textual similarities that indicate that they were produced in the same workshop (Steenholt Olesen 2007: 46, 2010: 337). One of the censers is only attributed to Jacob, while the remaining eleven bear his signature.

Jacob’s inscriptions exhibit a range of textual, orthographic, and palaeographic features that cannot be covered comprehensively in this article (see e.g. Steenholt Olesen 2007: 46–72 for an overview of his inscriptions and of issues concerning their readings, interpretations, and spelling). This section focuses on aspects of his language use relevant for understanding how he might have conceived his professional identity and employed linguistic resources to express it.

Censer with a runic inscription in Latin by master Jacob. Ulbølle, Denmark. Photo: runer.ku.dk

Jacob’s language and script choices indicate a complex professional identity rooted both in native traditions and in novel, Latin-influenced ones. In contrast to Harald, Jacob used only runes in his texts, but mixed Old Danish and Latin. His many signatures display in this regard a high degree of variation (see also Steenholt Olesen 2007: 57–63 for an overview of Jacob’s signatures and observations on his spelling): of eleven signatures, five are entirely in Latin, four are entirely in the vernacular (including one uncertain occurrence, i.e. DR 183 Ulbølle; see Figure 2), and two display code-switching (see examples 4 and 7).

[4] Fåborg (DR 173)

ma͡gist͡ær ⁝ ia͡ko͡bus ⁝ ruffus ⁝ fabær ⁝ me feciþ ⁝ guþ ⁝ si

Magister Iacobus Rufus faber me fecit. Guþ si[gne].

[Master Jacob Red smith made me. May God bless.]

[5] Hesselager (DR 175)

+ mæstær : iako͡p ⁝ ry͡þ ⁝ a͡f sinnæbu͡uhr ⁝ gør͡æ · mik : gesus krist

Mæstær Iakop Røþ af Swinæburg gørþæ mik. Iesus Krist.

[Master Jacob Red from Svineburg made me. Jesus Christ.]

[6] Hundstrup (DR 176)

magistæ͡r røþ

Magister Røþ.

[Master Red.]

[7] Svindinge (DR 181)

[mæstær : iakobus ruffus me fecit aufe maria kra]

Mæstær Iacobus Rufus me fecit. Ave Maria gra[tia].

[Master Jacob Red made me. Hail, Mary, (full of) grace.]

In addition to his own name, Jacob uses four attributes: ‘master’, ‘red’, ‘smith’, and ‘of Svineburg’. Only the last two, ‘smith’ and ‘of Svineburg’, appear exclusively in one language: Latin for ‘smith’ and Old Danish for the prepositional phrase (see Table 1).[3] His name and his other attributes, ‘master’ and ‘red’, are attested in both languages. Notable examples of this variation are the two bilingual signatures (Examples 6 and 7 above), where magister is paired with røþ ‘red’, and mæstær is paired with Iacobus Rufus.

Overview of the languages used for Master Jacob’s name and attributes. Numbers in parentheses indicate uncertain attestations.

|

Attribute |

Latin |

|

Old Danish |

|

|

‘master’ |

magister |

6 |

mæstær |

4 |

|

‘Jacob’ |

Iacobus |

6 |

Iakop |

2(1) |

|

‘red’ |

rufus |

5 |

røþ / røþlytr |

4(1) |

|

‘smith’ |

faber |

2(1) |

- |

0 |

|

‘of Svineburg’ |

- |

0 |

af Swinæburg |

1 |

While the corpus is too small to perform a quantitative analysis, qualitative observations regarding his language choice can shed light on how he perceived and projected his identity. For example, there appears to be a slight preference for Latin in the rendering of his title magister and an even clearer inclination to Latinize his own name. In my view, this is already an indication of the identity Jacob likely intended to convey.

While his name does appear in the vernacular in two inscriptions (e.g. Hesselager in Example 5), both are entirely in Old Danish, so they do not allow for a direct comparison between the use of vernacular and Latin.[4] However, we can note that the monolingual vernacular inscription from Hesselager shows the only instance of the attribute ‘of Svineburg’, indicating Jacob’s provenance. Although it occurs only once, it is tempting to see this all-vernacular signature as indexing belonging to a more local sphere, in contrast to the majority of Jacob’s signatures, which index a more cosmopolitan sphere.

While the vernacular signatures appear in inscriptions that do not permit direct comparison with Latin use, in three other bilingual inscriptions, it is notable that Latin was chosen specifically for the signature–thus projecting a more ‘modern’ identity–while other types of content were conveyed in Old Danish. Invocations to God are inscribed in the vernacular–Guþ(?) ‘God’ in Tjøme (DR 182) and Guþ si[gne] ‘may God bless’ in Fåborg (example 4)–as well as a commissioner’s signature–Toke køptæ mik ‘Toke bought me’ in Ollerup (DR 179; Example 8). The latter case may illustrate how different actors aligned themselves with different cultural or social contexts, or how Jacob may have sought to differentiate his cultural affiliation from that of the commissioner.

[8] Ollerup (DR 179)

+ magistær : iakobus : me fecit : toke : køptæ mik : maria

Magister Iacobus me fecit. Toke køptæ mik. Maria.

[Master Jacob made me. Toke bought me. Maria.]

Only one example in Jacob’s work runs counter to the patterns described above, i.e. an inscription in which he inscribed his signature in the vernacular while using Latin for other parts of the text. On the censer from Heden (DR 174), he signed himself as Mæstær Røþ, ‘Master Red’, but also added a longer Latin metrical sentence: Cras dabor toto die, sicque ago quotidie. The sentence can be translated literally as ‘Tomorrow I will be given the whole day, and thus I do/act every day’, though its exact meaning is unclear, possibly referring to the censer’s function (see Steenholt Olesen 2007: 63). The sentence is likely a quotation from a manuscript source, which Jacob either copied directly or adapted into a new proverb. Though no exact parallel has yet been found (Ertl 1994: 370), Steenholt Olesen (2007: 65) has identified a very similar wording in one of the Latin proverbs collected by Walther (1963, nr. 3613), namely Cras do, non hodie: sic nego cotidie, ‘Tomorrow I give, not today: hence I say no every day’. Unlike the short and formulaic Latin sequences typically found in runic inscriptions–such as signatures, memorial formulas, and prayers–this sentence stands out for its length, metrical form, and uniqueness within the corpus. The inclusion of such an uncommon addition may have served to convey his learnedness, thus serving a similar symbolic purpose as his Latin signatures in other inscriptions.

It is notable that Jacob’s rendering of Latin is largely free from mistakes, which otherwise appear quite often in Latin sequences rendered in runes (see e.g. Knirk 1998).[5] The Latin sequences in his inscriptions thus indicate that he possessed a certain level of language proficiency. Like other rune carvers, he displays various orthophonic spellings, i.e. spellings that reproduced the pronunciation of Latin. Examples of this are the use of þ for final /t/, e.g. feciþ for fecit, indicating lenition, and the distinction in the pronunciation of <c> as a plosive [k] and as a fricative [s] or affricate [ts], depending on the following vowel, for instance in Iacobus rendered as ia͡ko͡bus versus fecit rendered as feciþ (see also Steenholt Olesen 2007: 69–70). The significance of such spellings, however, has been a matter of debate. In some contexts, they have rightly been seen as a sign of lower literacy. However, the consistency of some of these spellings across a high number of runic inscriptions has led scholars to question whether they were in fact ad hoc or erroneous (Spurkland 2001: 127; Steenholt Olesen 2021: 77). Moreover, their occurrence in inscriptions which otherwise display grammatically correct Latin also suggests that they could have been the result of a conscious choice, or the product of learning Latin through the runic writing system and conventions, rather than through the Roman script (Palumbo 2022). Steenholt Olesen (2021: 101) has suggested that a “common understanding of vernacular orthography” underlay such renderings of Latin. It thus seems that magister Iacobus’ tendency to project a learned, Latin identity may have reflected a higher degree of actual proficiency compared to other rune carvers, including Master Harald discussed above.

In her epigraphic analysis of Master Jacob’s inscriptions, Steenholt Olesen (2007: 71) defines the function of the inscriptions on these censers as a “reklamemedium” (an ‘advertisement medium’), which very much aligns with my interpretation of the signatures of both inscribers examined in this article as means of marketing their skills by projecting a professional identity through conscious choices of language and script. She accounts for Jacob’s language choices by referring to the literacy of the intended readers: “indskrifterne må have været henvendt til et bestemt publikum, som har været såvel latin- som runekyndige og potentielle aftagere af sådanne kar” [The inscriptions must have been addressed to a specific audience who were both knowledgeable in Latin and runes, and potential buyers of such vessels] (Steenholt Olesen 2007: 71).

Explaining inscribers’ language and script choices with the intended audience’s literacy is a valid point. At the same time, consideration of actual readers is a variable whose role can be difficult to weigh because the texts on the censers, although public in one sense, are indeed quite small, raising the question of who would realistically have been able to read them. The choice of script–runes–was likely more immediately recognizable than the choice of language. Moreover, the inscriptions’ function as an ‘advertisement medium’ likely did not rely solely on being read, since knowledge of Master Jacob’s skills could also have circulated orally.

It is also worth noting that although Latin and the vernacular may have been employed to address readers with different literacy skills, it seems likely that individuals who could read Latin rendered in runes would also have been able to understand Old Danish in the same script. In my view, this suggests that the use of Latin was not dictated solely by reader design. Conversely, readers familiar with runes but not with Latin would probably have understood parts of the formulaic signature, likely recognizing the word magister due to its similarity to the vernacular mæstær, and certainly identifying the name Iacobus despite its Latinized form.

If these assumptions are plausible, Jacob’s choice of using runes most probably secured him a larger readership than if he had used Roman script (as Harald did), even if some of the readers would not have been able to fully understand the Latin sequences. At the same time, one should remember that comprehension of the lexical meaning of a text is not necessarily a prerequisite to perceive the indexical values of certain language and script choices–a sociolinguistic fact observed in both modern and historical contexts (e.g. Kelly-Holmes 2000; Liu 2017; Mullen 2012). Master Jacob’s primary audience may thus have even included a local readership unfamiliar with Latin, to whom he aimed to convey a dual professional identity. Against this backdrop, I would argue that–partly independently from his readers’ linguistic competence–the rich variation in Jacob’s language choices for his signatures reflects an adaptation to a changing linguistic market. His professional identity is thereby situated at the intersection of two cultural spheres: a local one rooted in the vernacular and runes, and a learned, cosmopolitan one, where Latin was the normative means of communication.

5 Conclusions

The analysis of Harald’s and Jacob’s inscriptions shows that language and script choices were central semiotic resources through which these craftsmen negotiated and projected their professional identities. Situated at a moment of profound cultural transition in medieval Scandinavia due to the spread of the Latin written culture, these inscribers operated in a changing linguistic market in which Latin and the Roman script were gaining value and occupying an increasingly important place in the symbolic economy where these and other craftsmen were active.

While one way to interpret Harald’s and Jacob’s linguistic choices is as a response to the literacy of their intended readers, it is clear that Latin and the Roman script in medieval Scandinavia could function in ways that exceeded its purely communicative value. The studied inscriptions provide several indications of this.

This symbolic dimension is particularly evident in the inscribers’ signatures, which display Latin and/or Roman script even when other types of content were rendered in runes and the vernacular. These signatures–the most personal and self-referential elements of the inscriptions–illustrate how the inscribers leveraged these resources to signal distinction and professional prestige, even when their primary training had been rooted in the vernacular runic tradition. The use of Latinized names and of the title magister, both uncommon features among Scandinavian rune carvers, suggests a deliberate attempt to foreground their Latin literacy–however partial–mobilized as a form of cultural capital.

Another indication of the symbolic value attached to Latin language and script is the tension between these linguistic choices and the actual proficiency of the inscribers. At times, Latin and the Roman script are used despite limited literacy and a noticeably weaker familiarity with them compared to runes and the vernacular. This suggests that their use may have been a deliberate stylistic choice rather than dictated by the inscribers’ skills. Similarly, reader design–the choice of language and script to accommodate readers’ literacy–does not necessarily appear to have been a primary concern. The individual texts do presuppose model readers with at least some degree of bilingual and biscriptal proficiency, and it is very plausible that at least part of the actual readership in fact possessed such skills. At the same time, I have argued that the choice of language and script in the signatures was made, at least in part, independently from the readers’ varying literacy and that it is highly likely that the display of Latin and Roman script served as an equally effective marker of cultural capital for readers who were not proficient in either.

This type of symbolic use of Latin and the Roman script is reminiscent of modern instances of commodification of languages and scripts, involving linguistic choices driven by economic considerations that prioritize symbolic value over purely communicative function (e.g. Kelly-Holmes 2014; Leeman and Modan 2009; Oštarić 2018; Pietikäinen et al. 2019). This means, among other things, that the language proficiency of writers and readers becomes less central. Language commodification can also involve the detachment of languages from (ethnic) identity, turning them into marketable commodities (e.g. Heller 2003). Such uses of languages (and scripts) have been labeled ‘inauthentic language’ (Sweetland 2002) and ‘linguistic fetish’ (e.g. Kelly-Holmes 2014), phenomena which illustrate how “the symbolic or visual value of a language takes precedence over its communicative value” (Kelly-Holmes 2014: 139; see also Kelly-Holmes 2016: 167). This does not mean that the communicative function of languages is entirely unimportant and, as Leeman and Modan (2009: 351) note, the relative importance of informational and symbolic value depends on the viewer’s level of literacy.

Despite the differences between the medieval context and the modern societies in which language commodification has been studied, the historical practices analyzed here offer glimpses of comparable dynamics. Harald’s and Jacob’s linguistic choices were clearly not dictated–at least not solely–by their own or their readers’ linguistic competence, nor by any inherent ethno-symbolic connection. These choices could thus be understood as a form of ‘language display’ (Eastman and Stein 1993; see also Coupland 2012): a visual Latin employed for symbolic purposes (cf. ‘visual English’, Kelly-Holmes 2014), serving to project professional distinctiveness and skill, cosmopolitanism, and “modernity”.

Such linguistic resources were, at the same time, paired with a continued use of the runes and the vernacular, resulting in a practice that anchored these inscribers in local practices as well as orienting them toward a wider, international professional and cultural network. Moreover, the simultaneous engagement with two different cultural spheres and communities of practice also illustrates the negotiation between different linguistic and textual norms, leading to creative mixing and adaptation, and resulting in distinctive professional personas.

More generally, the study of these two medieval inscribers also demonstrates that the symbolic use of languages and scripts has a long history, and that comparisons with modern phenomena through modern theoretical concepts–paired with philological analyses–can enhance the investigation of historical phenomena.

References

Adams, James Noel. 2003. Bilingualism and the Latin language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511482960Suche in Google Scholar

Aldrin, Emilia. 2016. Names and identity. In Carole Hough (eds.), The Oxford handbook of names and naming, 382–394. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199656431.013.24Suche in Google Scholar

Baglioni, Daniele & Olga Tribulato. 2015. Contatti di lingue – contatti di scritture: considerazioni introduttive. In Daniele Baglioni & Olga Tribulato (eds.), Contatti di lingue – Contatti di scritture. Multilinguismo e multigrafismo dal Vicino Oriente Antico alla Cina contemporanea (Filologie medievali e moderne 9), 9–37. Venice: Università Ca’ Foscari.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Rafael, Eliezer. 2009. A sociological approach to the study of singuistic sandscapes. In Elana Shohamy & Durk Gorter (eds.), Linguistic landscape. Expanding the scenery, 40–54. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Rafael, Eliezer, Elana Shohamy, Muhammad Hasan Amara & Nira Trumper-Hecht. 2006. Linguistic landscape as symbolic construction of the public space: The case of Israel. International Journal of Multilingualism 3(1). 7–30.10.1080/14790710608668383Suche in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Marco. 2010. Runor som resurs: Vikingatida skriftkultur i Uppland och Södermanland [Runes as a resource: Viking Age written culture in Uppland and Södermanland]. Uppsala: Institutionen för nordiska språk.Suche in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Marco. 2016. Runstenen som socialt medium [The rune stone as social medium]. In Daniel Anderson, Lars-Erik Edlund, Susanne Haugen & Asbjørg Westum (eds.), Studier i svensk språkhistoria 13: Historia och språkhistoria (Nordsvenska 25, Kungl. Skytteanska Samfundets Handlingar 76), 9–30. Umeå: Institutionen för språkstudier, Umeå universitet & Kungl. Skytteanska Samfundet.Suche in Google Scholar

Blennow, Anna. 2016. Sveriges medeltida latinska inskrifter 1050–1250: edition med språklig och paleografisk kommentar [Sweden’s medieval Latin inscriptions 1050–1250: edition with linguistic and palaeographic commentary]. Stockholm: Statens historiska museum.Suche in Google Scholar

Blennow, Anna & Alessandro Palumbo. 2021. At the crossroads between script cultures: The runic and Latin epigraphic areas of Västergötland. In Anna Catharina Horn & Johansson G. Karl (eds.), The Meaning of media: Texts and materiality in medieval Scandinavia (Modes of Modification 1), 39–69. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110695366-003Suche in Google Scholar

Blennow, Anna & Alessandro Palumbo. 2022. Epigrafiska områden i medeltidens Västergötland. Ett samspel mellan latinsk och runsk skriftkultur [Epigraphic areas of medieval Västergötland: Interplay between Latin and runic written culture]. Fornvännen 117(3). 181–197.Suche in Google Scholar

Blennow, Anna, Alessandro Palumbo & Jonatan Pettersson. 2022. Literate mentality and epigraphy. In Katharina Heiniger, Rebecca Merkelbach & Alexander Wilson (eds.), Þáttasyrpa – Studien zu Literatur, Kultur und Sprache in Nordeuropa. Festschrift für Stefanie Gropper (Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie 71), 21–37. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.10.24053/9783772057694-003Suche in Google Scholar

Bollaert, Johan. 2022. Visuality and literacy in the medieval epigraphy of Norway. Oslo: University of Oslo PhD dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information 16(6). 645–668.10.1177/053901847701600601Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In John G. Richardson (ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, 241–258. Westport, CT: Greenwood.Suche in Google Scholar

Cameron, Deborah. 2012. The commodification of language: English as a global commodity. In Terttu Nevalainen & Elizabeth Closs Traugott (eds.), The Oxford handbook of the history of English, 352–362. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199922765.013.0031Suche in Google Scholar

Gorter, Durk & Jasone Cenoz. 2024. A panorama of linguistic landscape studies. Bristol, Jackson: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781800417151Suche in Google Scholar

Coupland, Nikolas. 2012. Bilingualism on display: The framing of Welsh and English in Welsh public spaces. Language in Society 41. 1–27.10.1017/S0047404511000893Suche in Google Scholar

DR + number = runic inscription published in Lis Jacobsen & Erik Moltke (eds.), Danmarks runeindskrifter [Denmark’s runic inscriptions]. Copenhagen 1941–1942.Suche in Google Scholar

Eastman, Carol M. & Roberta F. Stein. 1993. Language display: Authenticating claims to social identity. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 14(3). 187–202.10.1080/01434632.1993.9994528Suche in Google Scholar

Ertl, Karin. 1994. Runen und Latein: Untersuchungen zu den skandinavischen Runeninschriften des Mittelalters in lateinischer Sprache. In Klaus Düwel (eds.), Runische Schriftkultur in kontinental-skandinavischer und -angelsächischer Wechselbeziehung: internationales Symposium in der Werner-Reimers-Stiftung vom 24.–27. Juni 1992 in Bad Homburg (Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde 10), 328–90. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Favreau, Robert, Jean Michaud & Bernadette Mora. 1989. Alpes-Maritimes, Bouches-du-Rhône, Var (Corpus des inscriptions de la France médiévale 14.) Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique.Suche in Google Scholar

Freund, Andrea & Ragnhild Ljosland. 2017. Modern rune carving in northern Scotland. Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies 8. 127–150.10.33063/diva-385073Suche in Google Scholar

Hansbøl, Gorm & John Krejsler. 2004. Konstruktion af professionel identitet: en kulturkamp mellem styring og autonomi i et markeds samfund [Construction of a professional identity: A cultural struggle between governance and autonomy in a market Society]. In John Krejsler & Per Fibæk Laursen (eds.), Relationsprofessioner – lærere, pædagoger, sygeplejerske, sundhedsplejerske, socialrådgivere og mellemledere [Relation professions – teachers, educators, nurses, health visitors, social workers, and middle managers], 19–58. København: Danmarks Pædagogiske universitets forlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Heggen, Kåre. 2008. Profesjon og identitet [Profession and identity]. In Anders Molander & Lars Inge Terum (eds.), Profesjonsstudier [Profession studies], 321–32. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.Suche in Google Scholar

Heller, Monica. 2003. Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7(4). 473–492.10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00238.xSuche in Google Scholar

Heller, Monica. 2010. The commodification of language. Annual Review of Anthropology 39(1). 101–114.10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104951Suche in Google Scholar

Heller, Monica & Alexandre Duchêne. 2016. Treating language as an economic resource: Discourse, data and debate. In Nikolas Coupland (ed.), Sociolinguistics: Theoretical debates, 139–156. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781107449787.007Suche in Google Scholar

Holmqvist, Karen Langsholt. 2018. Names and prayers: Expressions of self in the medieval inscriptions of the nidaros cathedral walls. Collegium medievale 31 (2018). 103–149.Suche in Google Scholar

Holmqvist, Karen Langsholt. 2020a. Mikill oflati ‘A great show-off’: Expressions of self in the runic inscriptions of Maeshowe, Orkney. Viking and Medieval Scandinavia 16.10.1484/J.VMS.5.121519Suche in Google Scholar

Holmqvist, Karen Langsholt. 2020b. The creation of selves as a social practice and cognitive process: A study of the construction of selves in medieval graffiti. In Stefka G. Eriksen, Karen Langsholt Holmqvist & Bjørn Bandlien (eds.), Approaches to the medieval self, 301–324. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Huebner, Thom. 2006. Bangkok’s linguistic landscapes: Environmental print, codemixing and language change. International Journal of Multilingualism 3(1). 31–51.10.1080/14790710608668384Suche in Google Scholar

Imer, Lisbeth M. 2021. Lumps of lead – New types of written sources from medieval Denmark. In Anna Catharina Horn & Johansson G. Karl (eds.), The meaning of media: Texts and materiality in medieval Scandinavia (Modes of Modification 1), 19–37. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110695366-002Suche in Google Scholar

Källström, Magnus. 2007. Mästare och minnesmärken: studier kring vikingatida runristare och skriftmiljöer i Norden [Masters and memorials: Studies on Viking Age rune carvers and writing milieus in the North] (Stockholm Studies in Scandinavian Philology 43). Stockholm: Institutionen för nordiska språk, Stockholms universitet.Suche in Google Scholar

Källström, Magnus. 2018. Haraldær stenmæstari – Haraldus magister: A case study on the interaction between runes and Roman script. In Alessia Bauer, Elise Kleivane & Terje Spurkland (eds.), Epigraphy in an intermedial context, 59–74. Dublin: Four Courts Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Kelly-Holmes, Helen. 2000. Bier, parfum, kaas: Language fetish in European advertising. European Journal of Cultural Studies 3(1). 67–82.10.1177/a010863Suche in Google Scholar

Kelly-Holmes, Helen. 2014. Linguistic fetish: The sociolinguistics of visual multilingualism’. In David Machin (ed.), Visual communication (Handbooks of Communication Science 4), 135–152. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110255492.135Suche in Google Scholar

Kelly-Holmes, Helen. 2016. Theorising the market in sociolinguistics. In Nikolas Coupland (ed.), Sociolinguistics: Theoretical debates, 157–172. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781107449787.008Suche in Google Scholar

Kleivane, Elise. 2021. Roman-script epigraphy in Norwegian towns. In Kasper H. Andersen, Jeppe Büchert Netterstrøm, Lisbeth M. Imer, Bjørn Poulsen & Rikke Steenholt Olesen (eds.), Urban literacy in the Nordic Middle Ages (Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy 53), 105–134. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.10.1484/M.USML-EB.5.126234Suche in Google Scholar

Knirk, James E. 1998. Runic inscriptions containing Latin in Norway. In Klaus Düwel (eds.), Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des vierten internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4.–9. August 1995 (Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde 15), 476–507. Berlin: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Krogull, Andreas & Gijsbert Rutten (eds.). 2025. Sociolinguistic perspectives on historical multilingualism in Europe. [Special issue]. Sociolinguistica 39(1).10.1515/soci-2025-0009Suche in Google Scholar

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. 2009. ‘Commodified Language in Chinatown: A Contextualized Approach to Linguistic Landscape’. Journal of Sociolinguistics 13 (3). 332–362.10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00409.xSuche in Google Scholar

Liu, Yin. 2017. Stating the obvious in runes. In Matti Peikola, Aleksi Mäkilähde, Hanna Salmi, Mari-Liisa Varila & Janne Skaffari (eds.), Verbal and visual communication in early English texts (Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy 37), 125–139. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.10.1484/M.USML-EB.5.114133Suche in Google Scholar

Ljosland, Ragnhild. 2014. Communicating identity: The modern runes of Orkney. Studia Historyczne 3. 412–430.Suche in Google Scholar

Mårtensson, Lasse. 2024. Personnamnen i de medeltida svenska runinskrifterna [Personal names in the medieval Swedish runic inscriptions]. Uppsala: Institutet för språk och folkminnen.Suche in Google Scholar

Mullen, Alex. 2012. Introduction: Multiple languages, multiple identities. In Alex Mullen & Patrick James (eds.), Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman worlds, 1–35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139012775.002Suche in Google Scholar

Mullen, Alex. 2013. Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean: Multilingualism and multiple identities in the Iron Age and Roman periods (Cambridge Classical Studies). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139105743Suche in Google Scholar

Mullen, Alex & Patrick James (eds.). 2012. Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139012775Suche in Google Scholar

Oštarić, Antonio. 2018. Commodification of a forsaken script: The Glagolitic script in contemporary Croatian material culture. In Larissa Aronin, Michael Hornsby & Grażyna Kiliańska-Przybyło (eds.), The material culture of multilingualism (Educational Linguistics 36), 189–208. Cham: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-91104-5_10Suche in Google Scholar

Palumbo, Alessandro. 2022. How Latin is runic Latin? Thoughts on the influence of Latin writing on medieval runic orthography. In Edith Marold & Christiane Zimmermann (eds.), Vergleichende Studien zur runischen Graphematik: methodische Ansätze und digitale Umsetzung (Runrön 25), 177–218. Uppsala: Institutionen för nordiska språk, Uppsala universitet.10.33063/diva-462705Suche in Google Scholar

Palumbo, Alessandro. 2023. Analysing bilingualism and biscriptality in medieval Scandinavian epigraphic sources: A sociolinguistic approach. Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics 9(1). 69–96.10.1515/jhsl-2022-0006Suche in Google Scholar

Palumbo, Alessandro. 2025. From the vernacular to Latin: Social functions and indexicalities in bilingual and biscriptal epitaphs of medieval Scandinavia. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 100(4). 1045–1083.10.1086/737383Suche in Google Scholar

Palumbo, Alessandro & Aurelija Tamošiūnaitė. Forthcoming. Biscriptality and script Choice. In Bridget Drinka, Terttu Nevalainen & Gijsbert Rutten (eds.), Handbook of Historical Sociolinguistics. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Pavlenko, Aneta. 2018. Superdiversity and why it isn’t: Reflections on terminological innovation and academic branding. In Barbara Schmenk, Stephan Breidbach & Lutz Küster (eds.), Sloganization in language education discourse, 142–68. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.22730494.11Suche in Google Scholar

Pavlenko, Aneta. 2023. Multilingualism and historical amnesia: An introduction. In Aneta Pavlenko (eds.), Multilingualism and history, 1–49. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009236287.001Suche in Google Scholar

Pavlenko, Aneta & Alex Mullen. 2015. Why diachronicity matters in the study of linguistic landscapes. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal 1(1–2). 114–32.10.1075/ll.1.1-2.07pavSuche in Google Scholar

Petersson, Bodil. 2010. Travels to identity: Viking rune carvers of today. Lund Archaeological Review 15&16. 71–86.Suche in Google Scholar

Petrucci, Livio. 2010. Alle origini dell’epigrafia volgare: iscrizioni italiane e romanze fino al 1275. Pisa: Pisa University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Pietikäinen, Sari, Helen Kelly-Holmes & Maria Rieder. 2019. Minority languages and markets. In Gabrielle Hogan-Brun & Bernadette O’Rourke (eds.), The Palgrave handbook of minority languages and communities, 287–310. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.10.1057/978-1-137-54066-9_11Suche in Google Scholar

Rutten, Gijsbert. 2016. Historicizing diaglossia. Journal of Sociolinguistics 20(1). 6–30.10.1111/josl.12165Suche in Google Scholar

Rutten, Gijsbert, Joseph Salmons, Wim Vandenbussche & Rik Vosters (eds). 2017. Historische Mehrsprachigkeit: Sprachkontakt, Sprachgebrauch, Sprachplanung / Historical multilingualism: language contact, use and planning / Le multilinguisme historique: contact, usage et aménagement linguistiques. [Special issue]. Sociolinguistica 31(1).10.1515/soci-2017-0002Suche in Google Scholar

Scandinavian Runic-text Database 2020. Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University. http://www.nordiska.uu.se/forskn/samnord.htmSuche in Google Scholar

Spurkland, Terje. 1998. Runic inscriptions as sources for the history of Scandinavian languages in the Middle Ages. In Klaus Düwel (eds.), Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des vierten internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4.–9. August 1995 (Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde 15), 592–600. Berlin: De Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Spurkland, Terje. 2001. Scandinavian medieval runic inscriptions: An interface between literacy and orality? In John Higgitt, Katherine Forsyth & David N. Parsons (eds.), Roman, runes and ogham: Medieval inscriptions in the insular world and on the Continent, 121–28. Donington: Shaun Tyas.Suche in Google Scholar

SRI = Various authors. 1900–. Sveriges runinskrifter [Sweden’s runic inscriptions]. 14 volumes to date. Stockholm: Kungliga Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien.Suche in Google Scholar

SRI 5 = Jungner, Hugo & Elisabeth Svärdström. 1940–1970. Västergötlands runinskrifter. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell internationalSuche in Google Scholar

Steele, Philippa M. 2018. Writing and society in ancient Cyprus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316729977Suche in Google Scholar

Steenholt Olesen, Rikke. 2007. Fra biarghrúnar til Ave sanctissima Maria: studier i danske runeindskrifter fra middelalderen [From biarghrúnar to Ave sanctissima Maria: Studies in Danish runic inscriptions from the Middle Ages]. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen PhD dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Steenholt Olesen, Rikke. 2010. Personal names in medieval runic inscriptions from Denmark. In Maria Giovanna Arcamone (eds.), I nomi nel tempo e nello spazio: atti del XXII Congresso internazionale di scienze onomastiche, Pisa, 28 Agosto – 4 Settembre 2005 (Nominatio. Collana di studi onomastici 7), 331–44. Pisa: Edizioni ETS.Suche in Google Scholar

Steenholt Olesen, Rikke. 2021. Medieval runic Latin in an urban perspective. In Kasper H. Andersen, Jeppe Büchert Netterstrøm, Lisbeth M. Imer, Bjørn Poulsen & Rikke Steenholt Olesen (eds.), Urban literacy in the Nordic Middle Ages (Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy 53), 69–103. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.10.1484/M.USML-EB.5.126233Suche in Google Scholar

Sweetland, Julie. 2002. Unexpected but authentic use of an ethnically-marked dialect. Journal of Sociolinguistics 6. 514–538.10.1111/1467-9481.00199Suche in Google Scholar

Torrens-Álvarez, María Jesús & Donald N. Tuten. 2022. From ‘Latin’ to the vernacular: Latin-romance hybridity, scribal competence, and social transformation in medieval Castile. Speculum. A Journal of Medieval Studies 97(3). 698–736.10.1086/720547Suche in Google Scholar

Vg + number = runic inscription published in SRI 5.Suche in Google Scholar

Walther, Hans. 1963. Proverbia sententiaeque latinitatis medii ac recentioris aevi. Lateinische Sprichwörter und Sentenzen des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit in alphabetischer Anordnung. Vol. 1. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.Suche in Google Scholar

Zilmer, Kristel. 2013. Christian prayers and invocations in Scandinavian runic inscriptions from the Viking Age and Middle Ages. Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies 4. 129–171.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 bei den Autorinnen und Autoren, publiziert von Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.