Correlation between the degree of pain relief following discoblock and short-term surgical disability outcome among patients with suspected discogenic low back pain

Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate how well the degree of pain relief after discoblock predicts the disability outcome of subsequent fusion or total disc replacement (TDR) surgery, based on short-term Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed a set of patients who had undergone discoblock and subsequent fusion or TDR surgery of the same lumbar intervertebral disc due to suspected discogenic chronic LBP between 2011 and 2018. We calculated the degree of pain relief following discoblock (ΔNRS) and the changes in both absolute and percentual ODI scores (ΔODI and ΔODI%, respectively) following fusion or TDR surgery. We analyzed the statistical significance of ΔNRS and ΔODI and the correlation (Spearman’s rho) between ΔNRS and ΔODI%. The fusion and TDR group were analyzed both in combination and separately.

Results

Fifteen patients were eligible for the current study (fusion n=9, TDR n=6). ΔNRS was statistically significant in all groups, and ΔODI was statistically significant in the combined group and in the fusion group alone. The parameters of both decreased. We found a Spearman’s rho of 0.57 (p=0.026) between ΔNRS and ΔODI% for the combined group. The individual Spearman’s rho values were 0.85 (p=0.004) for the fusion group and 0.62 (p=0.191) for the TDR group.

Conclusions

We suggest that discoblock is a useful predictive criterion for disability outcome prior to surgery for discogenic LBP, especially when stabilizing spine surgery is under consideration.

Ethical committee number

174/2019 (Oulu University Hospital Ethics Committee).

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most prevalent health problems in the world [1], and commonly arises from intervertebral disc degeneration (IVD). The pain associated with IVD is referred to as discogenic if no clear pathology or anatomical deformity is present. The diagnostic criteria of discogenic LBP are unclear [2]. Non-invasive methods such as physical examination and radiological imaging are either unsensitive or unspecific [3]. Lumbar discography is a widely used diagnostic procedure, and involves the injection of a contrast agent into the disc of interest. The concordance of the patient’s pain response and internal anatomy of the disc are subsequently evaluated [4]. Despite being more accurate than non-invasive methods, discography may be associated with high false-positive rates [4], [5], [6], complications [7], and poor predictive value for successful operative treatment [8, 9]. It also exposes patients to considerably strong pain sensation [4].

Discoblock is an alternative diagnostic method whereby an anesthetic agent is injected into the disc of interest and the result is considered positive when LBP decreases [10]. Liu et al. recently described notable clinical improvement among patients with discography- and discoblock-confirmed LBP 12 months after oblique lumbar interbody fusion, based on Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) values. The patients underwent the surgery following positive discography and positive discoblock [11]. However, patients were excluded if their discography was negative, which makes it difficult to interpret whether discoblock is a suitable stand-alone selection criterion for surgery. In a Japanese study, patients underwent anterior interbody fusion surgery after their discogenic LBP was confirmed by either discography or discoblock in a randomized fashion. Three years after surgery, the discoblock group had superior surgical results to those of the discography group, as evaluated using VAS, ODI, and the Japanese Orthopedic Association Score (JOAS) [10]. Notably, both studies categorized discoblock results in a binary manner without measuring the degree of post-procedural pain relief.

As scientific evidence of the usefulness of discoblock as a selection criterion for operative treatment of discogenic LBP is scarce, the present study evaluated whether the degree of pain relief following discoblock (ΔNRS) was a good predictor of the disability outcome of subsequent fusion or total disc replacement (TDR) surgery, based on short-term ODI scores.

Methods

Subjects

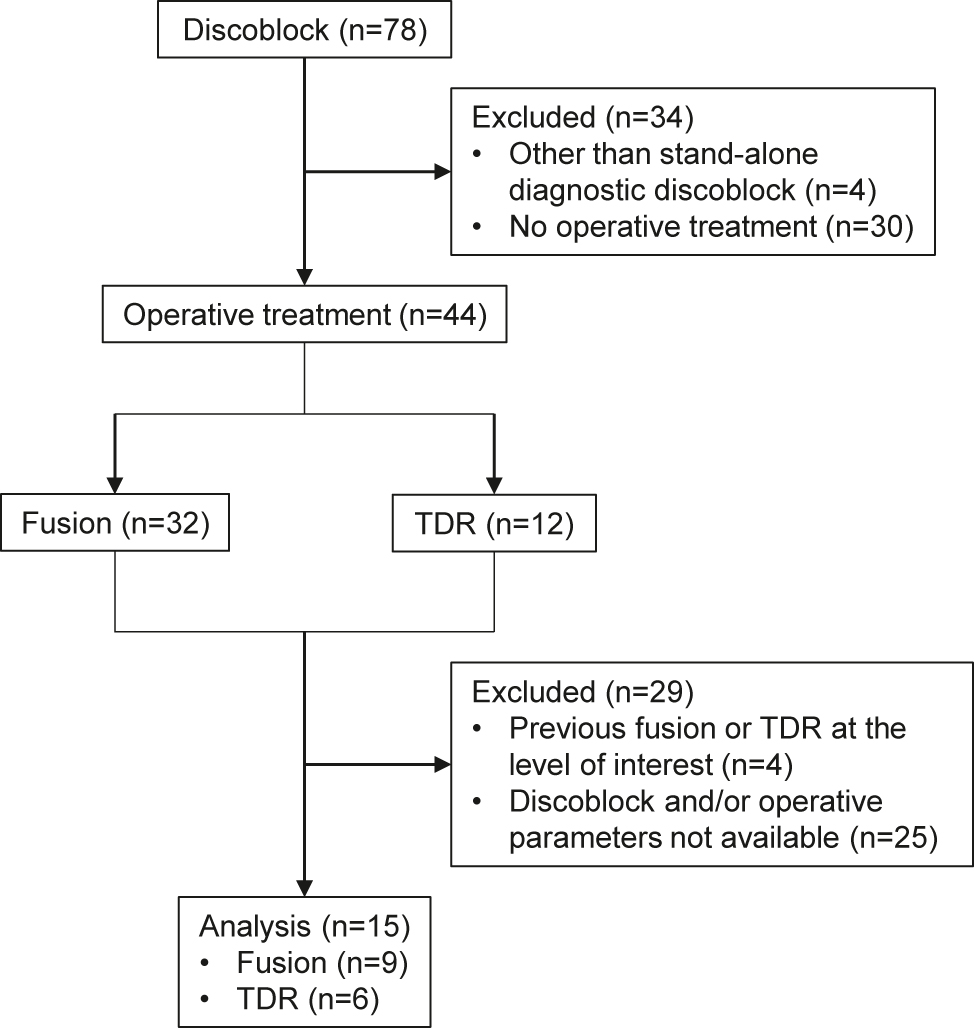

We retrospectively identified all patients who had undergone discoblock due to chronic LBP at the Oulu University Hospital between 2011 and 2018. Patients were selected to undergo discoblock due to a suspicion of discogenic LBP originating from a specific lumbar intervertebral disc, based on a clinical evaluation by a spine orthopedist which included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Initially, the patients were referred to the tertiary level hospital from primary care, secondary level hospital, or private sector as candidates for surgery due to their refractory chronic LBP. The patients were included in the present study if the spinal level of interest underwent discoblock and was subsequently operated using fusion or TDR surgery, if LBP was continuous for at least six months and responded suboptimally to conservative treatment, and if complete clinical parameters regarding discoblock and surgery were available. Patients were excluded from the present study if their chronic LBP was caused by any other pathological or anatomical cause (e.g., facet joint pathology, malignancy, fracture, infection, or rheumatic spine disease), if they had undergone previous fusion or TDR surgery at the lumbar level of interest, or if they were under 18 years of age. Of the 78 patients who underwent discoblock during the time frame, 15 (19.2%) met the inclusion criteria above and were included in the present study.

The study protocol was approved by the Oulu University Hospital Ethics Committee. As this was a retrospective registry study, no additional patients’ informed consent was required. The study was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Discoblock procedure

All the patients underwent discoblock prior to fusion or TDR surgery of the same lumbar level. The discoblock procedures were conducted under imaging guidance by an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist. The patient was placed in a supine or slight lateral recumbent position. Following local anesthesia of the skin (5–10 mL 10 mg/mL lidocaine), the discoblock needle was inserted into the disc of interest under fluoroscopic guidance using a posterolateral approach. Correct needle position was confirmed using fluoroscopy, and when necessary, additional cone beam CT.

Lidocaine 20 mg/mL was injected into the nucleus pulposus of the disc of interest. We used a target injection volume of 2 mL. The injection was discontinued if the patient experienced significant pain or if the injection pressure significantly increased. No pressure-controlled syringe was used. The pre-procedural Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) pain score was recorded directly before the injection at rest and the post-procedural NRS pain score 45 min after the injection. We used the standard form of the NRS pain score, which ranges from 0 to 10, a lower score indicating less pain [12]. We did not use any standardized provocative movements when assessing the post-procedural NRS pain score. However, patients were asked to move slightly to determine the degree of the pain.

Pre-procedural and post-procedural NRS pain scores were retrospectively extracted from the hospital’s radiology information systems database. The change in NRS pain score (ΔNRS, post-procedural NRS – pre-procedural NRS) was calculated for each patient.

Surgical procedures

An appropriate surgical method was chosen at the discretion of the operating spine surgeon in a patient-specific manner. The employed techniques were posterolateral fusion with pedicle screw fixation (PLF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) including PLF, anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) and TDR. Surgeries were conducted in accordance with the widely accepted technique standards and are described elsewhere [13], [14], [15]. We used the common form of the ODI score version 2.0 [16]. The total ODI score ranged between 0 and 100, a lower score indicating less disability. In accordance with Ostelo et al., we considered a reduction of 30% in ODI score clinically significant [17].

Preoperative and postoperative follow-up ODI scores, time intervals between preoperative ODI score assessment and surgery and follow-up times were retrospectively extracted from the hospital’s information systems database. Both absolute (ΔODI, postoperative ODI – preoperative ODI) and percentual (ΔODI% [preoperative ODI – postoperative ODI]/preoperative ODI) changes in ODI scores were calculated for each patient. The last ODI score assessed by a spine surgeon prior to surgery was used as a preoperative ODI score. All patients underwent a re-examination by the operating spine surgeon in 1–2 weeks’ range before surgery in which the LBP symptoms were confirmed unchanged and the final decision of the operation was done. The follow-up time was calculated as the time interval between surgery and the most recent postoperative follow-up appointment with the surgeon, during which the ODI score was evaluated. Operational complications were retrospectively recorded.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with 1st (Q1) and 3rd (Q3) quartiles and ranges. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate ΔNRS and ΔODI. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho) was calculated to compare ΔNRS with ΔODI%. Spearman’s rhos were also calculated to compare the postoperative ODI score with both the pre-procedural NRS pain score and the preoperative ODI score. The fusion and TDR groups were analyzed both in combination and separately. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (v. 26, IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

General characteristics

Fifteen patients underwent operations. Figure 1 illustrates the exclusion rates and reasons. Three (20%) patients underwent posterolateral fusion, two (13.3%) underwent TLIF, four (26.7%) underwent ALIF, and six (40.0%) underwent TDR. The spinal levels operated on were L5/S1 (n=9; 60%), L4/L5 (n=5; 33.3%) and L3/L4 (n=1; 6.7%). Table 1 presents the patient demographics.

Flow chart of the study setting. TDR, total disc replacement.

Demographic characteristics.

| Total | Fusion | TDR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (%) | 15 (100%) | 9 (60%) | 6 (40%) |

| No. of male sex (%) | 8 (53.3%) | 6 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Age range (mean ± SD), yr | 21.2–59.0 (44.9 ± 11.3) | 21.2–59.0 (47.3 ± 13.0) | 31.2–53.1 (41.5 ± 7.7) |

| No. of non-smokers (%) | 9 (60%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (66.7%) |

| Follow-up time range (mean ± SD), mo | 3.0–18.5 (10.8 ± 5.3) | 3.0–18.5 (9.2 ± 6.2) | 12.0–16.0 (13.3 ± 2.1) |

-

TDR, total disc replacement; SD, standard deviation; yr, years; mo, months.

Discoblock parameters

The median pre-procedural and post-procedural NRS pain scores for the combined group were 7.0 (Q1 5.0; Q3 8.0; range 3.0–10.0) and 1.0 (Q1 0; Q3 3.0; range 0–5.0), respectively. The median reduction in NRS pain score was −5.0 (Q1 −7.0; Q3 −2.5; range from −2.0 to −8.0; p<0.001) for the combined group. Table 2 presents the discoblock parameters for the fusion group and TDR group separately.

Procedural and operative parameters.

| Total | Fusion | TDR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | |

| Discoblock (NRS) | |||||||||

| Pre-procedural | 7.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 3.3 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 8.3 |

| Post-procedural | 1.0 | 0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 3.4 |

| ΔNRS | −5.0 | −7.0 | −2.5 | −4.0 | −6.0 | −2.3 | −5.5 | −7.0 | −4.4 |

| p-Values | <0.001a | 0.004a | 0.031a | ||||||

| Surgery (ODI) | |||||||||

| Preoperative | 50.0 | 42.0 | 54.0 | 44.0 | 38.0 | 58.0 | 52.0 | 49.0 | 55.0 |

| Postoperative | 36.0 | 14.0 | 52.0 | 27.0 | 14.0 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 29.5 | 59.0 |

| ΔODI | −8.0 | −28.0 | −2.0 | −18.0 | −30.0 | 0 | −7.0 | −18.0 | 6.0 |

| p-Values | 0.021a | 0.043a | 0.313 | ||||||

| ΔODI% | −13.8% | −66.7% | −3.7% | −40.9% | −74.1% | −0.8% | −12.7% | −36.5% | 12.2% |

-

TDR, total disc replacement; Q1, 1st quartile; Q3, 3rd quartile; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; ΔNRS, degree of pain relief following discoblock; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; ΔODI, absolute change in ODI score following surgery; ΔODI%, percentual change in ODI score following surgery. ap<0.05.

Operative parameters

The preoperative ODI score was assessed on average 133 days (range 9–228, median 151 days) before surgical treatment during a preoperative appointment with the spine surgeon. The mean follow-up time was 10.8 months (SD 5.3; range 3.0–18.5 months). For the combined group, the median preoperative and postoperative ODI scores were 50.0 (Q1 42.0; Q3 54.0; range 30.0–76.0) and 36.0 (Q1 14.0; Q3 52.0; range 4.0–80.0), respectively. The median absolute decrease in ODI score was −8.0 (Q1 −28.0; Q3 −2.0; range from −62.0 to 30.0; p=0.021) and the median percentual decrease was −13.8% (Q1 −66.7%; Q3 −3.7%; range from −88.9% to 60.0%) for the combined group. Table 2 presents the operative parameters for the fusion group and TDR group separately.

Twelve patients’ ODI scores decreased following surgery, whereas three patients’ ODI scores increased. Three (20.0% of total) patients had postoperative complications, which consisted of nonunion after posterolateral fusion (n=1; 33.3%), painful prothesis misalignment after TDR (n=1; 33.3%), and neuropathic pain after TDR (n=1; 33.3%). Of these, two (66.7%) patients required reoperation.

Correlation analysis

We found a Spearman’s rho of 0.57 (p=0.026) between ΔNRS and ΔODI% for the combined group. The individual Spearman’s rho values were 0.85 (p=0.004) for the fusion group and 0.62 (p=0.191) for the TDR group. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation.

Scatter box showing the positive correlations between the ΔNRS and the percentual change in ODI score for the combined fusion and TDR group, and the fusion and TDR groups separately. TDR, total disc replacement; ΔNRS, degree of pain relief following discoblock; ΔODI%, percentual change in ODI score following surgery. *Indicates a line of percentual decrease of 30% in ODI score. †p=0.026, ‡p=0.004.

The postoperative ODI score did not significantly correlate with the pre-procedural NRS pain score or the preoperative ODI score (rho −0.30; p=0.276 and rho 0.31; p=0.257 for the combined group; rho −0.52; p=0.156 and rho 0.19; p=0.620 for the fusion group; rho 0.058; p=0.913 and rho 0.20; p=0.700 for the TDR group).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the ΔNRS with the disability outcome of operative treatment of discogenic LBP. We found a moderate positive correlation between the ΔNRS and short-term surgical disability outcome measured as a decrease in the postoperative ODI score for the combined group. Thus, our results suggest that the ΔNRS can be utilized to predict surgical disability outcome following lumbar fusion or TDR surgery of discogenic LBP.

Further, the correlation between the ΔNRS and postoperative ODI score appeared stronger in the fusion group than in the TDR group (rho 0.85 vs. 0.62, respectively). To the authors’ knowledge, the correlation between discoblock result and TDR surgery outcome has not previously been assessed. Although we used mixed fusion techniques, our results are consistent with previous studies that have reported positive discoblock results to have a predictive value for superior anterior and oblique lumbar fusion outcomes [10, 11]. Thus, we believe that discoblock, among other standard methods (i.e., physical examination and MRI), is a viable selection criterion for the operative treatment of discogenic LBP, especially when fusion surgery is under consideration.

We recorded pain relief following discoblock using a numerical continuous NRS pain score, as opposed to previous studies, which considered discoblock to be positive when a patient has obtained any relief at all for their LBP [10, 11]. In the present study, only one of six (16.7%) patients whose pain relief following discoblock was moderate (i.e., ΔNRS 0–4) exceeded the clinically significant decrease of 30% in the ODI score [17] following surgery (Figure 2). In addition to using the NRS pain score to report the discoblock results, we suggest a discoblock result of ΔNRS >−4 as a disqualifying factor for the operative treatment of discogenic LBP. In addition, using the NRS pain score may reduce the subjectivity of discoblock.

The complication group and the increasing ΔODI% group both included three patients. These groups were overlapped by one patient who underwent TDR with a ΔNRS of −6 and had an inferior ΔODI% of +60.0%. On the two other patients whose ΔODI% increased, discoblock seemed to work as hypothesized (ΔNRS −2 and −2.5; ΔODI% +17.4% and +5.0%, respectively). Conversely, discoblock, as a preoperative test, predicted postoperative complications poorly; patients suffering from complications had ΔNRSes of −2; −5; and −6. As operative complications have a broad variety of possible sources including surgical approach- and device-related [18], we keep discoblock’s inability to predict operative complications reasonable. Furthermore, the complications might also account for the insignificance of the ΔODI among TDR patients. Of the three patients who suffered postoperative complications, two had undergone TDR surgery. They had minimal to no improvement in disability (ΔODI −8 and +30) after a somewhat notable pain relief following discoblock (ΔNRS −5 and −6, respectively). Constituting a third of the TDR group, these patients might have caused the insignificance.

We found no statistically significant correlations between postoperative ODI score and pre-procedural NRS pain score or preoperative ODI score, both of which are identified as patient-related baseline factors that affect the surgical disability outcome of spine surgery [19]. However, as many other confounding factors are present in spine surgery [19, 20] and surgical treatment is generally considered a controversial treatment for discogenic LBP [21], determining discoblock’s predictive value solely on the basis of surgical outcomes may be problematic. This issue is also known as the “gold standard” dilemma. Since no objective standardized method is available for diagnosing discogenic LBP or for comparing to novel diagnostic criterion, validating discoblock or any other diagnostic method is challenging [5]. Therefore, further research on the diagnostics of discogenic LBP is needed.

The unclear diagnostic criteria of discogenic LBP naturally also affect our study setting. Intervertebral disc, facet joint, and sacroiliac joint (SI joint), in order of estimated prevalence, are potential pain generators of LBP. In addition to intra-structural injections and SI joint scintigraphy, the best readily available diagnostic methods to diagnose said structures as the LBP source are physical tests and MRI, both of which our study sample underwent, interpreted by a spine surgeon [3]. As we injected only suspected painful intervertebral discs based on MRI and clinical evaluation, and SI joint originating pain occurs more caudad to lumbar spine [22], we think we defined our study sample as accurately as possible to discogenic LBP patients. Nevertheless, we are unable to completely rule out a clinical bias regarding false assumptions of discogenic LBP as aforementioned diagnostic methods are informationally defective and the complexity of LBP is known [3, 23, 24].

Modic changes are lesions in vertebral endplates seen in MRI as changes in signal intensities. Briefly, Modic change type I represents active inflammation and fibrovascular growth; type II, fatty replacement; and type III, sclerotic conversion of the adjacent bone marrow [25], [26], [27]. These changes are connected to endplate defects and disc degeneration [28, 29]. A positive correlation has been reported between Modic changes and both positive discoblock [30, 31] and superior fusion outcomes [32], [33], [34]. In the current study, the greater response to discoblock might be attributable to the inflammatory phase of the adjacent bone marrow, that is, to type I Modic changes. Therefore, it is possible that our results are related to Modic changes. However, further evaluation is needed in the future.

Our study has some limitations. The design of the study was retrospective and had a limited sample size. We might have introduced a selection bias to our study, as the patients who underwent discoblock might have expressed more severe symptoms or have had discrepancy in their diagnostics. Regarding discoblock, some patients’ pre-procedural NRS pain score could have been low and therefore influenced the magnitude of the reduction in the NRS pain score. In addition, our study lacked a control group, and we could only analyze short-term surgical results in the absence of other common outcome measures besides the ODI score. Although common, the mixed fusion techniques might bias our results. We could not analyze ΔODI% in the fusion subgroups due to our limited sample size. It should also be noted that albeit patients were given a strong recommendation to quit nicotine preoperatively, the operating spine surgeon made the decision patient-wise if continued smoking was a disqualification criterion for surgery. Additionally, the time interval between the assessment of preoperative ODI score and surgery was relatively long for some patients (maximum 228 days). However, patients were re-examined by the operating spine surgeon in one to two weeks’ range before the operation to confirm LBP symptoms unchanged.

In conclusion, we found a moderate, positive correlation between the ΔNRS and short-term surgical disability outcome among patients who underwent fusion or TDR surgery for discogenic LBP. The correlation was very strong in the fusion group. Thus, our findings suggest that discoblock is a useful predictive criterion for disability outcome prior to surgery for discogenic LBP, especially when stabilizing spine surgery is under consideration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Tommi Korhonen MD, PhD for his comments on the manuscript draft.

-

Research funding: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: As this was a retrospective registry study, no additional patients’ informed consent was required.

-

Ethical approval: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013), and has been approved by the Oulu University Hospital Ethics Committee (REC# 174/2019).

References

1. Hoy, D, Bain, C, Williams, G, March, L, Brooks, P, Blyth, F, et al.. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34347.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Fujii, K, Yamazaki, M, Kang, JD, Risbud, MV, Cho, SK, Qureshi, SA, et al.. Discogenic back pain: literature review of definition, diagnosis, and treatment. JBMR Plus 2019;3:e10180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10180.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Hancock, MJ, Maher, CG, Latimer, J, Spindler, MF, McAuley, JH, Laslett, M, et al.. Systematic review of tests to identify the disc, SIJ or facet joint as the source of low back pain. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1539–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0391-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Carragee, EJ, Alamin, TF. Discography. a review. Spine J 2001;1:364–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1529-9430(01)00051-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Manchikanti, L, Glaser, SE, Wolfer, L, Derby, R, Cohen, SP. Systematic review of lumbar discography as a diagnostic test for chronic low back pain. Pain Physician 2009;12:541–59. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2009/12/541.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Wolfer, LR, Derby, R, Lee, J, Lee, S. Systematic review of lumbar provocation discography in asymptomatic subjects with a meta-analysis of false-positive rates. Pain Physician 2008;11:513–38. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2008/11/513.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Carragee, EJ, Don, AS, Hurwitz, EL, Cuellar, JM, Carrino, JA, Carrino, J, et al.. 2009 ISSLS prize winner: does discography cause accelerated progression of degeneration changes in the lumbar disc: a ten-year matched cohort study. Spine 2009;34:2338–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181ab5432.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Cohen, SP, Larkin, TM, Barna, SA, Palmer, WE, Hecht, AC, Stojanovic, MP. Lumbar discography: a comprehensive review of outcome studies, diagnostic accuracy, and principles. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:163–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rapm.2004.10.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Staartjes, VE, Vergroesen, PA, Zeilstra, DJ, Schröder, ML. Identifying subsets of patients with single-level degenerative disc disease for lumbar fusion: the value of prognostic tests in surgical decision making. Spine J 2018;18:558–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2017.08.242.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ohtori, S, Kinoshita, T, Yamashita, M, Inoue, G, Yamauchi, K, Koshi, T, et al.. Results of surgery for discogenic low back pain: a randomized study using discography versus discoblock for diagnosis. Spine 2009;34:1345–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181a401bf.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Liu, J, He, Y, Huang, B, Zhang, X, Shan, Z, Chen, J, et al.. Reoccurring discogenic low back pain (LBP) after discoblock treated by oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF). J Orthop Surg Res 2020;15:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-1554-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Haefeli, M, Elfering, A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J 2006;15:S17–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-1044-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Mobbs, RJ, Phan, K, Malham, G, Seex, K, Rao, PJ. Lumbar interbody fusion: techniques, indications and comparison of interbody fusion options including PLIF, TLIF, MI-TLIF, OLIF/ATP, LLIF and ALIF. J Spine Surg 2015;1:2–18. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2414-469X.2015.10.05.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Tropiano, P, Huang, RC, Girardi, FP, Cammisa, FP, Marnay, T. Lumbar total disc replacement. surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(1 Suppl):50–64. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200603001-00006.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Tajima, N, Chosa, E, Watanabe, S. Posterolateral lumbar fusion. J Orthop Sci 2004;9:327–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-004-0773-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Fairbank, JC, Pynsent, PB. The oswestry disability index. Spine 2000;25:2940–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Ostelo, Raymond, WJG, Deyo, RA, Stratford, P, Waddell, G, Croft, P, et al.. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine 2008;33:90–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e31815e3a10.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Lang, SAJ, Bohn, T, Barleben, L, Pumberger, M, Roll, S, Büttner-Janz, K. Advanced meta-analyses comparing the three surgical techniques total disc replacement, anterior stand-alone fusion and circumferential fusion regarding pain, function and complications up to 3 years to treat lumbar degenerative disc disease. Eur Spine J 2021;30:3688–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06784-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. McGirt, MJ, Bydon, M, Archer, KR, Devin, CJ, Chotai, S, Parker, SL, et al.. An analysis from the quality outcomes database, part 1. disability, quality of life, and pain outcomes following lumbar spine surgery: predicting likely individual patient outcomes for shared decision-making. J Neurosurg Spine 2017;27:357–69. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.11.spine16526.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Khor, S, Lavallee, D, Cizik, AM, Bellabarba, C, Chapman, JR, Howe, CR, et al.. Development and validation of a prediction model for pain and functional outcomes after lumbar spine surgery. JAMA Surg 2018;153:634–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0072.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Gibson, JNA, Waddell, G. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis: updated cochrane review. Spine 2005;30:2312–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000182315.88558.9c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Szadek, KM, van der Wurff, P, van Tulder, MW, Zuurmond, WW, Perez, RSGM. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain 2009;10:354–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Nijs, J, Apeldoorn, A, Hallegraeff, H, Clark, J, Smeets, R, Malfliet, A, et al.. Low back pain: guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant neuropathic, nociceptive, or central sensitization pain. Pain Physician 2015;18:E333–46. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2015/18/e333.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Maher, C, Underwood, M, Buchbinder, R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017;389:736–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30970-9.Suche in Google Scholar

25. de Roos, A, Kressel, H, Spritzer, C, Dalinka, M. MR imaging of marrow changes adjacent to end plates in degenerative lumbar disk disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:531–4. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.149.3.531.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Modic, MT, Masaryk, TJ, Ross, JS, Carter, JR. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology 1988;168:177–86. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.168.1.3289089.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Modic, MT, Steinberg, PM, Ross, JS, Masaryk, TJ, Carter, JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology 1988;166:193–9. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336678.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Dudli, S, Fields, AJ, Samartzis, D, Karppinen, J, Lotz, JC. Pathobiology of modic changes. Eur Spine J 2016;25:3723–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4459-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Jensen, TS, Karppinen, J, Sorensen, JS, Niinimäki, J, Leboeuf-Yde, C. Vertebral endplate signal changes (modic change): a systematic literature review of prevalence and association with non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1407–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0770-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Putzier, M, Streitparth, F, Hartwig, T, Perka, CF, Hoff, EK, Strube, P. Can discoblock replace discography for identifying painful degenerated discs? Eur J Radiol 2013;82:1463–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.03.022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Alamin, TF, Kim, MJ, Agarwal, V. Provocative lumbar discography versus functional anesthetic discography: a comparison of the results of two different diagnostic techniques in 52 patients with chronic low back pain. Spine J 2011;11:756–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2011.07.021.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Esposito, P, Pinheiro-Franco, JL, Froelich, S, Maitrot, D. Predictive value of MRI vertebral end-plate signal changes (modic) on outcome of surgically treated degenerative disc disease. results of a cohort study including 60 patients. Neurochirurgie 2006;52:315–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3770(06)71225-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Pinson, H, Hallaert, G, Herregodts, P, Everaert, K, Couvreur, T, Caemaert, J, et al.. Outcome of anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a retrospective study of clinical and radiologic parameters. World Neurosurg 2017;103:772–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.077.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Vital, JM, Gille, O, Pointillart, V, Pedram, M, Bacon, P, Razanabola, F, et al.. Course of modic 1 six months after lumbar posterior osteosynthesis. Spine 2003;28:715–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000051924.39568.31.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Reviews

- Long-term opioid treatment and endocrine measures in patients with cancer-related pain: a systematic review

- Prevalence of pain in adult patients with moderate to severe haemophilia: a systematic review

- Topical Review

- Evidence of distorted proprioception and postural control in studies of experimentally induced pain: a critical review of the literature

- Clinical Pain Researchs

- Headache and quality of life in Finnish female municipal employees

- Discriminant properties of the Behavioral Pain Scale for assessment of procedural pain-related distress in ventilated children

- Long-term biopsychosocial issues and health-related quality of life in young adolescents and adults treated for childhood Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, type 1

- The association between pain and central nervous system depressing medication among hospitalised Norwegian older adults

- “Opioids are opioids” – A phenomenographic analyses of physicians’ understanding of what makes the initial prescription of opioids become long-term opioid therapy

- Comparing what the clinician draws on a digital pain map to that of persons who have greater trochanteric pain syndrome

- Temperament and character dimensions differ in chronic post-surgical neuropathic pain and cold pressure pain

- Correlation between the degree of pain relief following discoblock and short-term surgical disability outcome among patients with suspected discogenic low back pain

- Cold allodynia is correlated to paroxysmal and evoked mechanical pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Observational Studies

- Analgesic use in adolescents with patellofemoral pain or Osgood–Schlatter Disease: a secondary cross-sectional analysis of 323 subjects

- Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the pain anxiety symptom scale (PASS-20) in chronic non-specific neck pain patients

- High score of dizziness-handicap-inventory (DHI) in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain makes a chronic vestibular disorder probable

- Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and palliative-care clinician reported outcomes (ClinROs) mutually improve pain and other symptoms assessment of hospitalized cancer-patients

- Adults with unilateral lower-limb amputation: greater spatial extent of pain is associated with worse adjustment, greater activity restrictions, and less prosthesis satisfaction

- Original Experimentals

- Exploration of the trait-activation model of pain catastrophizing in Native Americans: results from the Oklahoma Study of Native American pain risk (OK-SNAP)

- “Convergent validity of the central sensitization inventory and experimental testing of pain sensitivity”

- Hypoalgesia after exercises with painful vs. non-painful muscles in healthy subjects – a randomized cross-over study

- Neuromodulation of somatosensory pain thresholds of the neck musculature using a novel transcranial direct current stimulation montage: a randomized double-blind, sham controlled study

- Short Communication

- Self-compassion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain: a pilot study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Reviews

- Long-term opioid treatment and endocrine measures in patients with cancer-related pain: a systematic review

- Prevalence of pain in adult patients with moderate to severe haemophilia: a systematic review

- Topical Review

- Evidence of distorted proprioception and postural control in studies of experimentally induced pain: a critical review of the literature

- Clinical Pain Researchs

- Headache and quality of life in Finnish female municipal employees

- Discriminant properties of the Behavioral Pain Scale for assessment of procedural pain-related distress in ventilated children

- Long-term biopsychosocial issues and health-related quality of life in young adolescents and adults treated for childhood Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, type 1

- The association between pain and central nervous system depressing medication among hospitalised Norwegian older adults

- “Opioids are opioids” – A phenomenographic analyses of physicians’ understanding of what makes the initial prescription of opioids become long-term opioid therapy

- Comparing what the clinician draws on a digital pain map to that of persons who have greater trochanteric pain syndrome

- Temperament and character dimensions differ in chronic post-surgical neuropathic pain and cold pressure pain

- Correlation between the degree of pain relief following discoblock and short-term surgical disability outcome among patients with suspected discogenic low back pain

- Cold allodynia is correlated to paroxysmal and evoked mechanical pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Observational Studies

- Analgesic use in adolescents with patellofemoral pain or Osgood–Schlatter Disease: a secondary cross-sectional analysis of 323 subjects

- Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the pain anxiety symptom scale (PASS-20) in chronic non-specific neck pain patients

- High score of dizziness-handicap-inventory (DHI) in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain makes a chronic vestibular disorder probable

- Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and palliative-care clinician reported outcomes (ClinROs) mutually improve pain and other symptoms assessment of hospitalized cancer-patients

- Adults with unilateral lower-limb amputation: greater spatial extent of pain is associated with worse adjustment, greater activity restrictions, and less prosthesis satisfaction

- Original Experimentals

- Exploration of the trait-activation model of pain catastrophizing in Native Americans: results from the Oklahoma Study of Native American pain risk (OK-SNAP)

- “Convergent validity of the central sensitization inventory and experimental testing of pain sensitivity”

- Hypoalgesia after exercises with painful vs. non-painful muscles in healthy subjects – a randomized cross-over study

- Neuromodulation of somatosensory pain thresholds of the neck musculature using a novel transcranial direct current stimulation montage: a randomized double-blind, sham controlled study

- Short Communication

- Self-compassion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain: a pilot study