Abstract

Objectives

In patients with a vestibular disorder a high score of dizziness-handicap-inventory (DHI) is common. Patients with chronic lithiasis of multiple canals benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (mc-BPPV) can have incapacitating symptoms, e.g. headache, neck pain, musculoskeletal pain, and cognitive dysfunction. Patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain with few objective findings at an ordinary examination of the musculoskeletal system together with unsuccessful interventions can either receive a diagnosis of a biopsychosocial disorder or a diagnosis connected to the dominant symptom. The aim of this investigation is to examine if the DHI- and the DHI subscale scores are abnormal in 49 patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders. In addition, explore the possibility of a chronic mc-BPPV diagnosis.

Methods

Consecutive prospective observational cohort study at five different physiotherapy clinics. A personal interview using a structured symptom questionnaire consisting of 15 items. Modified Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) including the Physical-, Catastrophic- and Emotional impact DHI subscale scores suggested by the Mayo Clinic was applied.

Results

Eighty-four percent of the 49 patients have a pathological DHI-score and a potential underlying undiagnosed vestibular disorder. Very few patients have scores at the catastrophic subscale. A correlation is found between the number of symptoms of the structured scheme and the DHI-score. Results from all five physiotherapy clinics were similar.

Conclusions

Patients with a high number of symptoms and a high DHI-score can have a potential underlying treatable balance disorder like mc-BPPV. Increased awareness and treatment of mc-BPPV may reduce suffering and continuous medication in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Regional Ethical Committee (No IRB 00001870).

Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain often results in an interplay of biological, psychological, and social influences and is considered a biopsychosocial disorder. The definition of multiple canals benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (mc-BPPV) is given in point 3.3 from the consensus document of the Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society [1]. According to the consensus document, BPPV is probably the most common vestibular disorder, and up to 20% of these are with lithiasis in multiple canals [1], [2], [3]. mc-BPPV probably occurs most often after trauma [4].

The clinical appearance and the diagnostics of mc-BPPV is different from the obvious one of an ordinary posterior canal BPPV. The symptoms of headache, neck pain, temporo-mandubular joint region (TMJ) pain, other localized- or generalized pain, together with fatigue and cognitive dysfunction are common [5], [6], [7].

Patients with chronic mc-BPPV and a history of trauma with few objective findings at an ordinary examination of the musculoskeletal system as well as a headache survey together with unsuccessful interventions may potentially receive the label of a biopsychosocial disorder. Among these patients, it is natural to feel frustrated and discouraged over lost quality of life and social consequences. Unfortunately, many patients are misdiagnosed due to lack of objective findings, i.e., lack of the objective findings one is looking for, not lack of objective findings overall.

In patients with chronic mc-BPPV abnormal signals are transmitted from a diseased labyrinth to the healthy normally functioning vestibular nuclei complex in the brainstem. From there, the abnormal signals go directly via the vestibulo-spinal reflexes or via different cranial nerve nuclei to their end organs, which act in an abnormal way [8]. The actual diagnosis the patient receives is often based on the patient’s dominant symptom.

In a retrospective cohort study of 163 patients with chronic mc-BPPV and a history of trauma 98% of the 163 patients fulfilled the Barany Society criteria of a probable vestibular migraine; 17% fulfilled the International Classification of Headache Disorders defined vestibular migraine criteria; 63% fulfilled the Fukuda criteria of ME/CFS (i.e., myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome); 100% of the patients with whiplash associated disorders (WAD) suffered from chronic mc-BPPV. This survey supports the hypothesis that chronic mc-BPPV may be the trigger of symptoms in vestibular migraine, ME/CFS and WAD [7].

In patients with a vestibular disorder a high score on the dizziness-handicap-inventory (DHI) is common. DHI was developed to quantify the detrimental effects of dizziness on an individual’s life [9]. According to a recent investigation from the Mayo Clinic, the analysis of the DHI total score can be supplemented by subscale scores i.e., Physical manifestations, Catastrophic impact, and Emotional impact of dizziness on the patient with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) [10].

The aim of this investigation is to examine if the total DHI score as well as the DHI subscale scores are abnormal in 49 patients with a chronic musculoskeletal pain disorder of more than one year’s duration. In addition, the current study will explore the possibility of a chronic mc-BPPV diagnosis among these patients.

Methods

Study setting and participants

This prospective observational study consists of a cohort of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and is performed at four different private physiotherapy clinics in Southern Norway and one in Denmark. The first 10 patients aged 15–60 years who suffer from on-going musculoskeletal pain for more than one year who were referred to the physiotherapy clinic in the period April to November 2016 were included. Patients with CNS disorders and neoplastic disorders were excluded. Two clinics have an urban location, one is a rural clinic, and two clinics receive patients from mixed urban and rural areas.

Questionnaires

Structured symptom questionnaire

A personal interview was performed by the physiotherapist at the respective clinic. The questionnaire consists of 15 items: headache, neck- and/or shoulder pain, TMJ pain, other localized pain, generalized pain, isolated rotatory vertigo, nautical vertigo, dizziness, nausea, fatigue with effort intolerance, visual disturbance, shopping center discomfort, tinnitus, concentration difficulties, short term memory difficulties. Patients answer always, sometimes, or no to each question.

Modified dizziness handicap inventory (DHI)

The Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) is validated for individuals with vestibular dysfunction. The tool consists of 25 items that are scored as always (four points), sometimes (two points), and never (zero point) for a maximum score of 100. A score >60 indicates an increased likelihood of having a fall [9, 11].

The original DHI has a choice of yes, sometimes or no. Since it is easier to respond ‘yes’ than the definitive ‘always’, we have decided to use ‘always’ instead of ‘yes’, re-naming the questionnaire as the Modified DHI. This alternative is used by Elizabeth H Toe [12]. Thus, we expect to get a lower, but probably more accurate DHI-score.

All the questions of the DHI inquiry deal with ‘the condition’, where dizziness is a compulsory part of the symptom complex. The Barany Society characterizes dizziness as a sensation of disturbed spatial orientation [13]. According to the literature a DHI-score >20 is considered abnormal [11, 12, 14].

DHI subscales

According to the reappraisal of the DHI inquiry at the Mayo Clinic of analyzing data from the DHI: calculate a total score and then calculate subscale scores to assess the Physical manifestations, Catastrophic impact, and Emotional impact of dizziness on the patient with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) [10]. Contrary to the original subscales developed empirically by Jacobson and Newman [9], the present subscales are based on an exploratory factor analysis [10].

A confirming answer to question Number 13 ‘Does turning over in bed increase your problem?’ is considered as a strong suggestion of a BPPV [15]. A confirming answer to question Number 25 ‘Does bending over increase your problem?’ supports a suggestion of a BPPV involving the anterior SCC [16].

Table 1 presents the actual questions of the physical-, catastrophic- and emotional subscales. The full DHI questionnaire is shown in the references.

The questions of the physical-, catastrophic- and emotional subscales. The DHI-questionnaire numbers are shown. Number of confirming positive answers. Proportion of the 41 patients with a DHI score above 20.

| No | Physical manifestations | Number confirming positive answers | Proportion of patients with a DHI score >20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=49 | n=41 | ||

| 1 | Does looking up increase your problem? | 30 | 73% |

| 5 | Because of your problem, do you have difficulty getting into or out of bed? | 37 | 90% |

| 11 | Do quick movements of your head increase your problem? | 37 | 90% |

| 13 | Does turning over in bed increase your problem? | 37 | 90% |

| 25 | Does bending over increase your problem? | 40 | 98% |

| No | Catastrophic manifestations | Number confirming positive answers | Proportion of patients with a DHI score >20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=49 | n=41 | ||

| 9 | Because of your problem, are you afraid to leave your home without having someone accompany you? | 2 | 5% |

| 16 | Because of your problem, is it difficult for you to go for a walk by yourself? | 4 | 10% |

| 20 | Because of your problem, are you afraid to stay home alone? | 2 | 5% |

| No | Emotional manifestations | Number confirming positive answers | Proportion of patients with a DHI score >20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=49 | n=41 | ||

| 2 | Because of your problem, do you feel frustrated? | 44 | 100% |

| 22 | Has your problem placed stress on your relationship with members of your family or friends? | 14 | 32% |

| 23 | Because of your problem, are you depressed? | 30 | 73% |

Statistical analysis

The StatSoft-statistical program, copyright 2015 (Tulsa, OK 74104, USA) is used for the analyses. Non-parametric analysis is used for non-normally distributed data. Kruskal-Wallis (two-tailed) test is used for comparing the DHI-scores of the different physiotherapy clinics. Chi-Square test is used for comparing gender. To evaluate whether there is a correlation between the number of symptoms and the DHI score, DHI subscale scores as well as age, the Spearman Rank Order Correlation coefficients are calculated (p=0.05).

Results

Demographics of the patients

Forty-nine patients (38 female) with a median age of 49 years (range 18–60 years) are included. There are no differences among the patients of the different physiotherapy clinics in regard to gender (p=0.08) and age (p=0.80). Thirty-two patients i.e., 65%, have a history of trauma resulting from fall accidents (29%), road traffic accidents (27%), sport injuries (10%) and three individuals (6%) suffer from more than one trauma.

Symptoms

The main reasons for contacting the physiotherapy clinics are neck and shoulder pain (37%), generalized pain (18%), lumbar spine pain (18%), headache (16%), and other localized pain (10%).

The symptom frequency of all patients is given in Table 2.

The symptom frequencies of patients who report the specific symptom either as always or as sometimes are demonstrated.

| Symptom | Always in percent | Sometimes in percent |

|---|---|---|

| n=49 | ||

| Headache | 18 | 63 |

| Neck-and/or shoulder pain | 53 | 35 |

| TMJ-pain | 8 | 29 |

| Other localized pain | 51 | 27 |

| Generalized pain | 35 | 18 |

| Rotatory vertigo | 0 | 12 |

| Isolated | ||

| Nautical vertigo | 4 | 14 |

| Isolated | ||

| Dizziness | 2 | 16 |

| Isolated | ||

| Any movement illusion* | 6 | 45 |

| Nausea | 2 | 35 |

| Fatigue with effort intolerance | 18 | 31 |

| Visual disturbance | 8 | 41 |

| Shopping center discomfort | 18 | 31 |

| Tinnitus | 6 | 24 |

| Concentration difficulties | 24 | 49 |

| Short term memory difficulties | 14 | 41 |

-

*Any kind of combination of movement illusions, i.e., rotatory-, nautical vertigo and dizziness.

Vertigo

The vertigo appearance in declining frequencies is rotatory-, nautical- and dizziness (18%); isolated dizziness (16%); isolated nautical- (14%); isolated rotatory- (12%); rotatory- and dizziness (12%); nautical- and dizziness (10%); rotatory- and nautical- (4%). This means that 40% of the present patients have a vertigo which does not appear to be rotatory.

DHI scores

The DHI total score and DHI subscale scores of the five different physiotherapy clinics are shown in Table 3.

The median percentile total DHI score, physical-, catastrophic – and emotional DHI subscores are demonstrated. Quartiles in brackets. The p-values of the comparisons are shown.

| Physio 1 | Physio 2 | Physio 3 | Physio 4 | Physio 5 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=10 | n=10 | n=6 | n=10 | n=13 | ||

| Total DHI | 36 [18–40] | 30 [20–40] | 45 [32–54] | 36 [24–42] | 34 [34–48] | 0.438 |

| Physical DHI | 55 [30–60] | 45 [40–60] | 50 [50–60] | 50 [20–60] | 50 [30–50] | 0.992 |

| Catastrophical DHI | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–17] | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–0] | 0.649 |

| Emotional DHI | 25 [17–33] | 17 [17–33] | 50 [50–50] | 33 [17–33] | 50 [33–50] | 0.183 |

Distribution of patients and their percentual DHI scores

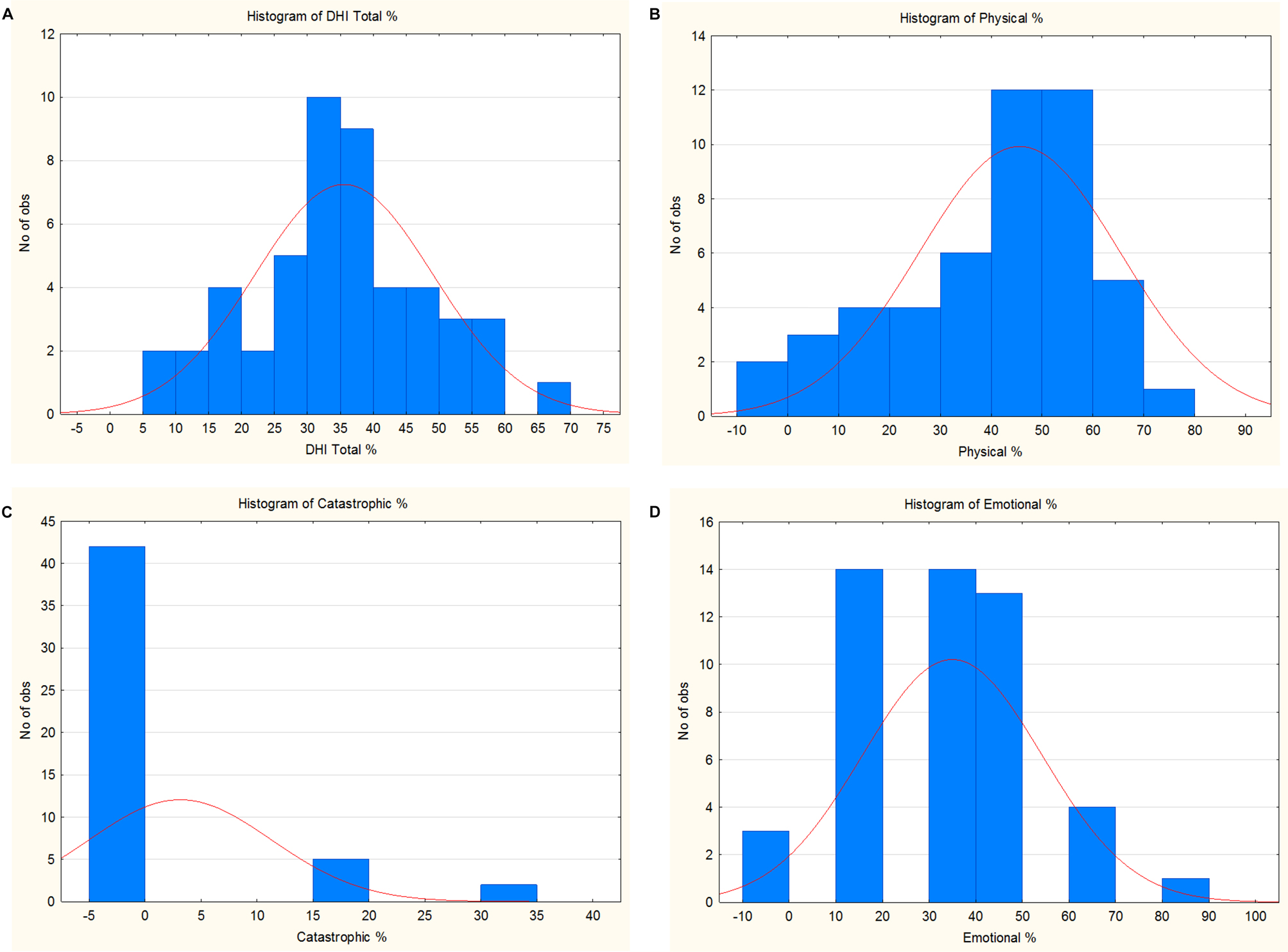

The distribution of patients and their percentual total DHI score as well as the DHI subscale scores are given in Figure 1A–D. Forty-one patients (i.e., 84%) out of 49 have a total DHI score above 20. Forty-one out of 49 patients have a physical manifestation DHI subscale score above 20 and 30 out of 49 patients (i.e., 61%) have a physical manifestation DHI subscale score above 40.

The number of patients on the Y-axis who obtained the percentual score of the (A) total DHI score as well as the DHI subscale scores: (B) physical-; (C) catastrophic-; (D) emotional- shown at the X-axis.

Answers of the physical-, catastrophic- and emotional DHI subscale questions are given in Table 1.

Correlations

The correlation ‘r-values’ between Total DHI score, physical-, catastrophic – and emotional DHI subscale scores, number of symptoms and age are shown in Table 4.

The correlations (shown as the ‘r values’) between total DHI score, physical-, catastrophic – and emotional DHI subscale scores, number of symptoms and age.

| Total | Physical | Catastrophic | Emotional | Number of symptoms | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1.00 | 0.57* | 0.38* | 0.62* | 0.83* | −0.03 |

| Physical | 0.57* | 1.00 | −0.09 | 0.19 | 0.35* | 0.11 |

| Catastroph | 0.38* | −0.09 | 1.00 | 0.36* | 0.36* | 0.05 |

| Emotional | 0.62* | 0.19 | 0.36* | 1.00 | 0.46* | −0.32* |

| Number of symptoms | 0.83* | 0.35* | 0.36* | 0.46* | 1.00 | 0.03 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.32* | 0.03 | 1.00 |

-

Marked correlations. *are significant at p<0.05.

Discussion

DHI scores

This observational study has shown that 84% of a cohort of 49 patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders have a pathological DHI score. A high DHI score makes a vestibular disorder probable [9, 14] and a chronic mc-BPPV possible [5, 6, 10, 11, 14]. Eighty-four percent have a physical manifestation DHI subscale score above 20 and 61% have a score above 40. At the Mayo clinic Van de Wyngaerde et al. [10] examined the predictive accuracy of responses of the subscales to the presence of BPPV. Using this subscale, a diagnosis of BPPV for these patients could be predicted successfully. Thus, their results showed the probability of having BPPV increased significantly as the patients endorsed a greater number of items from the subscale. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders of more than one year’s duration and a high DHI score likely suffer from an undiagnosed vestibular disorder like a chronic mc-BPPV.

Correlation between DHI scores and number of symptoms

The investigation takes place at five different physiotherapy clinics distributed in urban and rural areas. There is a high correlation between the number of symptoms, typically seen in chronic mc-BPPV [5], [6], [7] and the DHI score among all 49 patients. The greater the number of symptoms, the higher the DHI score was. A similar correlation is observed between the number of symptoms and the physical- and emotional DHI subscale scores.

Subscale scores

Very few patients were found to have scores at the catastrophic subscale. The scores of the emotional subscale are similar to the scores of the physical subscale. However, the emotional questions mostly express sadness of their condition and not a general panic reaction, which the catastrophic subscale indicates. The present subscales are based on an exploratory factor analysis [10] which results in a diagnosis of BPPV. Therefore, we raise the question: Could patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and a high DHI score have a balance disturbance as the driving force behind the vicious cycle of pain?

Consider a mc-BPPV

The most important factor is for the examiner to consider the possibility of a balance disorder as a cause of the chronic pain when dealing with patients who have chronic polysymptomatic musculoskeletal pain.

Individuals with a chronic vestibular disorder normally obtain a habituation according to Hebb’s principle of neural plasticity [17]. Therefore, it is expected that the influence of the vestibular pathology would fade away. Patients with a static balance disturbance such as vestibular neuritis usually improve following compensatory exercises, this however is not the case for individuals with a dynamic balance disturbance such as mc-BPPV and Ménière’s disease [18]. It is impossible to compensate in the same way within a canalithiasis with its dislocated free-floating otoliths and debris because the affected labyrinth(s) transmit(s) varying abnormal signals from time to time to the same stimuli. This is probably why their symptoms are ongoing.

In the present study, high scores of questions of the physical DHI subscale typically for BPPV was found, which agree with the mathematical model by the Mayo Clinic [15, 16]. Patients with involvement of a diseased anterior SCC are common in chronic mc-BPPV [7, 19, 20], and are often more seriously affected than patients without [19, 20].

A clinical investigation can be performed for diagnosing a chronic mc-BPPV, the Dix-Hallpike test for the posterior semicircular canal (SCC), the horizontal side-lying test for the horizontal SCC and the bending forward test for the anterior SCC are used, i.e., the first position in the treatment of each semicircular canal [16].

Dominant symptom gives the diagnosis

Compound disorders with uncharacteristic symptoms can be interpreted in several ways [7]. If pain is the dominant symptom, less attention is paid to balance related symptoms, and therefore examination of the vestibular system is not included in the general overview. An example of this is the history of a fifty-year-old man who had suffered a road traffic accident. His main complaint was invalidating headache. He visited several different specialists and always opened with ‘the giddiness came first’, but it was always ignored, because the headache was the dominating symptom. We focused on his chronic mc-BPPV and after otolith repositioning according to the diseased SCCs, the headache ceased.

Trauma

Two thirds of the present patients have a history of trauma. Earlier trauma seems to be of relevance in chronic mc-BPPV [1, 4, 19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. The trauma can occur years before the onset of symptoms. This agrees with the statement of Ernst et al. [29] that any trauma of the head, neck, and craniocervical junction can have a major impact on the vestibular system at different sites.

Symptoms

The symptom frequencies of the patients are mostly consistent with previously reported findings of patients with chronic mc-BPPV [5], [6], [7]. The postural control is mainly secured through vestibulo-spinal [30] and vestibulo-reticular reflexes [31]. From a teleological point of view, their purpose is to protect the individual from falling. The lateral vestibulo-spinal reflex is involved in control of torso and extremity muscle tension. The medial one is related to control of the neck. The reticular formation maintains a level of tonus and integrates information from several neural centers. A disturbance in the delicate integration of facilitatory and inhibitory signals in the myotatic spinal reflexes [3] is important for developing musculoskeletal pain.

TMJ-region pain among patients with chronic mc-BPPV is probably due to the involvement of the anterior SCC [7, 16].

In the current study few patients suffered isolated acute attacks of rotatory vertigo. In patients with chronic mc-BPPV any kind of movement illusion can occur [1]. Vertigo has become a part of daily living for many patients with a long history of illness. For example, at shopping centers there is a powerful stimulation of the peripheral view, which stimulates the optokinetic system, which signals directly terminate in the vestibular nuclei complex [8].

Cognitive difficulties could be explained via the vestibulo-thalamic reflex in patients with chronic mc-BPPV [32, 33].

There are indications that the non-classical pathways are abnormally active via a vestibular input in connection with tinnitus [34, 35]. This is not the case for the classical continuing treble or high frequency tinnitus.

Strength and limitation

A strength of the investigation is that the study is performed at different clinics and the findings of the patients are similar in all consecutive patient groups. However, one clinic with pure rural recruiting was unable to reach 10 patients. This was compensated with the Danish urban/rural patient group. The skew gender distribution in the current study is consistent with previously reported findings [36, 37]. A weakness is that the cohort is restricted to only 49 patients.

Conclusions

The current study, by using the DHI inquires and a symptom questionnaire, has shown that patients with compound chronic musculoskeletal disorders may be suffering from an undiagnosed vestibular disorder, like a chronic mc-BPPV. Increased awareness and treatment of chronic mc-BPPV may reduce suffering and need for continuous medication.

Implications

The most important point is for the examiner to consider the possibility of a balance disorder as a cause of the chronic pain when dealing with patients who suffer from chronic musculoskeletal pain. A clinical investigation can be performed for diagnosing a chronic mc-BPPV, the Dix-Hallpike test for the posterior semicircular canal (SCC), the horizontal side-lying test for the horizontal SCC and the bending forward test for the anterior SCC are used, i.e., the first position in the treatment of each semicircular canal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ellen Abusdal, Kvadraturen Fysikalske Institut, Kristiansand; Østby og Flottorp, Markensgt. 35, Kristiansand; Nina Anda Eiken, Agder Fysioterapi Eiken; as well as Vibeke Samalo and Sanne Stræde Madsen, Bene-FiT Sæby, Denmark for their valuable contribution to this study.

-

Research funding: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contribution: Iglebekk and Tjell are responsible for the study concept and design. They have full access to all data in the study and the accuracy of the data analysis and interpretation of the data. Drafting of the manuscript. Both have read and approved the final version.

-

Competing interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed written consent was obtained from all participants in the study and participation was entirely voluntary.

-

Ethical approval: This study is in accordance with ethical standards on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Formal approval was given by the Regional Ethical Committee (No IRB 00001870).

References

1. von Brevern, M, Bertholon, P, Brandt, T, Fife, T, Imai, T, Nuti, D, et al.. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2015;25:105–17. https://doi.org/10.3233/ves-150553.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Lopez-Escamez, JA, Molina, MI, Gamiz, M, Fernandez-Perez, AJ, Gomez, M, Palma, MJ, et al.. Multiple positional nystagmus suggests multiple canal involvement in benign paroxysmal vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol 2005;125:954–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480510040146.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Nakayama, M, Epley, JM. BPPV and variants: improved treatment results with automated, nystagmus-based repositioning. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;133:107–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Bertholon, P, Chelikh, L, Tringali, S, Timoshenko, A, Martin, C. Combined horizontal and posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in three patients with head trauma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005;114:105–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940511400204.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Iglebekk, W, Tjell, C, Borenstein, P. Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Scand J Pain 2013;4:233–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.06.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Iglebekk, W, Tjell, C, Borenstein, P. Treatment of chronic canalithiasis can be beneficial for patients with vertigo/dizziness and chronic musculoskeletal pain, including whiplash related pain. Scand J Pain 2015;8:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.02.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Tjell, C, Iglebekk, W, Borenstein, P. Can a chronic BPPV with a history of trauma be the trigger of symptoms in vestibular migraine, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS) and whiplash associated disorders (WAD)? A retrospective cohort study. Otol Neurotol 2019;40:96–102. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000002020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Goldberg, ME, Walker, MF, Hudspeth, AJ. The vestibular system. In: Kandel, ER, Schwartz, JH, Jessel, TM, Siegelbaum, SA, Hudspeth, AJ, editors. Principles of neural science, 5th ed. New York, NY: MCGraw-Hill Companies; 2013:917–34 pp.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Jacobson, GP, Newman, CW. The development of the dizziness handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;116:424–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1990.01870040046011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Van De Wyngaerde, KM, Lee, MK, Jacobson, GP, Pasupathy, K, Romero-Brufau, S, McCaslin, DL. The component structure of the dizziness handicap inventory (DHI): a reappraisal. Otol Neurotol 2019;40:1217–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000002365.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Whitney, SL, Marchetti, GF, Morris, LO. Usefulness of the dizziness handicap inventory in the screening for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2005;26:1027–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mao.0000185066.04834.4e.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Toe, E. Vestibular rehabilitation. In: Weber, PC, editor. Vertigo and disequlibrium. New York, NY: Thieme; 2008:149–50 pp.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Bisdorff, A, von Brevern, M, Lempert, T, Newman-Toker, DE (on behalf of the Committee for the Classification of the Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society). Classification of vestibular symptoms: towards an international classification of vestibular disorders. J Vestib Res 2009;19:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3233/ves-2009-0343.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Vanspauwen, R, Knoop, A, Camp, S, van Dinther, J, Erwin Offeciers, F, Somers, T, et al.. Outcome evaluation of the dizziness handicap inventory in an outpatient vestibular clinic. J Vestib Res 2016;26:479–86. https://doi.org/10.3233/VES-160600.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Lindell, E, Finizia, C, Johansson, M, Karlsson, T, Nilson, J, Magnusson, M. Asking about dizziness when turning in bed predicts examination findings for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res 2018;28:339–47. https://doi.org/10.3233/ves-180637.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Iglebekk, W, Tjell, C, Borenstein, P. Can the bending forward test be used to detect a diseased anterior semi-circular canal in patients with chronic vestibular multi-canalicular canalithiasis (BPPV)? Acta Otolaryngol 2019;139:1067–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2019.1667529.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Hebb, DO. The organization of behavior. New York: Wiley and Sons; 1949.Suche in Google Scholar

18. McDonnell, MN, Hillier, SL. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;1:CD005397. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Jackson, LE, Morgan, B, Fletcher, JCJr, Krueger, WWO. Anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an underappreciated entity. Otol Neurotol 2007;28:218–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mao.0000247825.90774.6b.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Dlugaiczyk, J, Siebert, S, Hecker, DJ, Brase, C, Schick, B. Involvement of the anterior semicircular canal in posttraumatic benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2011;32:1285–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0b013e31822e94d9.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Katsarkas, A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): idiopathic vs. post-traumatic. Acta Otolaryngol 1999;119:745–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489950180360.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Monobe, H, Sugasawa, K, Murofushi, T. The outcome of the canalith repositioning procedure for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2001;545:38–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/000164801750388081.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Cohen, HS, Kimball, KT, Stewart, MG. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and comorbid conditions. ORL J Oto-Rhino-Laryngol its Relat Specialties 2004;66:11–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000077227.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Gordon, CR, Levite, R, Joffe, V, Gadoth, N. Is posttraumatic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo different from the idiopathic form? Arch Neurol 2004;61:1590–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.61.10.1590.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Pollak, L, Stryjer, R, Kushnir, M, Flechter, S. Approach to bilateral benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. Am J Otolaryngol 2006;27:91–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.07.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Kansu, L, Avci, S, Yilmaz, I, Ozluoglu, LN. Long-term follow-up of patients with posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol 2010;130:1009–12. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016481003629333.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Ahn, SK, Jeon, SY, Kim, JP, Hur, DG, Kim, DW, Woo, SH, et al.. Clinical characteristics and treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 2011;70:442–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0b013e3181d0c3d9.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Balatsouras, DG, Koukoutsis, G, Aspris, A, Fassolis, A, Moukos, A, Economou, NC, et al.. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to mild head trauma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2017;126:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489416674961.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Ernst, A, Basta, D, Seidl, RO, Todt, I, Scherer, H, Clarke, A. Management of posttraumatic vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;132:554–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2004.09.034.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Goldberg, JM, Cullen, KE. Vestibular control of the head: possible functions of the vestibulocollic reflex. Exp Brain Res 2011;210:331–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-011-2611-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Tellegen, AJ, Arends, JJ, Dubbeldam, JL. The vestibular nuclei and vestibuloreticular connections in the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos L.) an anterograde and retrograde tracing study. Brain Behav Evol 2001;58:205–17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000057564.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Espinosa-Sanchez, JM, Lopez-Escamez, JA. New insights into pathophysiology of vestibular migraine. Front Neurol 2015;6:12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2015.00012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. O’Connell Ferster, AP, Priesol, AJ, Isildak, H. The clinical manifestations of vestibular migraine: a review. Auris Nasus Larynx 2017;44:249–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2017.01.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Møller, AR, Møller, MB, Yokota, M. Some forms of tinnitus may involve the extralemniscal auditory pathway. Laryngoscope 1992;102:1165–71.10.1288/00005537-199210000-00012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Møller, AR. Tinnitus: presence and future. Prog Brain Res 2007;166:3–16.10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66001-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Mansfield, KE, Sim, J, Croft, P, Jordan, KP. Identifying patients with chronic widespread pain in primary care. Pain 2017;158:110–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000733.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Andrews, P, Steultjens, M, Riskowski, J. Chronic widespread pain prevalence in the general population: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2018;22:5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Reviews

- Long-term opioid treatment and endocrine measures in patients with cancer-related pain: a systematic review

- Prevalence of pain in adult patients with moderate to severe haemophilia: a systematic review

- Topical Review

- Evidence of distorted proprioception and postural control in studies of experimentally induced pain: a critical review of the literature

- Clinical Pain Researchs

- Headache and quality of life in Finnish female municipal employees

- Discriminant properties of the Behavioral Pain Scale for assessment of procedural pain-related distress in ventilated children

- Long-term biopsychosocial issues and health-related quality of life in young adolescents and adults treated for childhood Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, type 1

- The association between pain and central nervous system depressing medication among hospitalised Norwegian older adults

- “Opioids are opioids” – A phenomenographic analyses of physicians’ understanding of what makes the initial prescription of opioids become long-term opioid therapy

- Comparing what the clinician draws on a digital pain map to that of persons who have greater trochanteric pain syndrome

- Temperament and character dimensions differ in chronic post-surgical neuropathic pain and cold pressure pain

- Correlation between the degree of pain relief following discoblock and short-term surgical disability outcome among patients with suspected discogenic low back pain

- Cold allodynia is correlated to paroxysmal and evoked mechanical pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Observational Studies

- Analgesic use in adolescents with patellofemoral pain or Osgood–Schlatter Disease: a secondary cross-sectional analysis of 323 subjects

- Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the pain anxiety symptom scale (PASS-20) in chronic non-specific neck pain patients

- High score of dizziness-handicap-inventory (DHI) in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain makes a chronic vestibular disorder probable

- Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and palliative-care clinician reported outcomes (ClinROs) mutually improve pain and other symptoms assessment of hospitalized cancer-patients

- Adults with unilateral lower-limb amputation: greater spatial extent of pain is associated with worse adjustment, greater activity restrictions, and less prosthesis satisfaction

- Original Experimentals

- Exploration of the trait-activation model of pain catastrophizing in Native Americans: results from the Oklahoma Study of Native American pain risk (OK-SNAP)

- “Convergent validity of the central sensitization inventory and experimental testing of pain sensitivity”

- Hypoalgesia after exercises with painful vs. non-painful muscles in healthy subjects – a randomized cross-over study

- Neuromodulation of somatosensory pain thresholds of the neck musculature using a novel transcranial direct current stimulation montage: a randomized double-blind, sham controlled study

- Short Communication

- Self-compassion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain: a pilot study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Reviews

- Long-term opioid treatment and endocrine measures in patients with cancer-related pain: a systematic review

- Prevalence of pain in adult patients with moderate to severe haemophilia: a systematic review

- Topical Review

- Evidence of distorted proprioception and postural control in studies of experimentally induced pain: a critical review of the literature

- Clinical Pain Researchs

- Headache and quality of life in Finnish female municipal employees

- Discriminant properties of the Behavioral Pain Scale for assessment of procedural pain-related distress in ventilated children

- Long-term biopsychosocial issues and health-related quality of life in young adolescents and adults treated for childhood Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, type 1

- The association between pain and central nervous system depressing medication among hospitalised Norwegian older adults

- “Opioids are opioids” – A phenomenographic analyses of physicians’ understanding of what makes the initial prescription of opioids become long-term opioid therapy

- Comparing what the clinician draws on a digital pain map to that of persons who have greater trochanteric pain syndrome

- Temperament and character dimensions differ in chronic post-surgical neuropathic pain and cold pressure pain

- Correlation between the degree of pain relief following discoblock and short-term surgical disability outcome among patients with suspected discogenic low back pain

- Cold allodynia is correlated to paroxysmal and evoked mechanical pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Observational Studies

- Analgesic use in adolescents with patellofemoral pain or Osgood–Schlatter Disease: a secondary cross-sectional analysis of 323 subjects

- Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the pain anxiety symptom scale (PASS-20) in chronic non-specific neck pain patients

- High score of dizziness-handicap-inventory (DHI) in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain makes a chronic vestibular disorder probable

- Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and palliative-care clinician reported outcomes (ClinROs) mutually improve pain and other symptoms assessment of hospitalized cancer-patients

- Adults with unilateral lower-limb amputation: greater spatial extent of pain is associated with worse adjustment, greater activity restrictions, and less prosthesis satisfaction

- Original Experimentals

- Exploration of the trait-activation model of pain catastrophizing in Native Americans: results from the Oklahoma Study of Native American pain risk (OK-SNAP)

- “Convergent validity of the central sensitization inventory and experimental testing of pain sensitivity”

- Hypoalgesia after exercises with painful vs. non-painful muscles in healthy subjects – a randomized cross-over study

- Neuromodulation of somatosensory pain thresholds of the neck musculature using a novel transcranial direct current stimulation montage: a randomized double-blind, sham controlled study

- Short Communication

- Self-compassion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain: a pilot study