Abstract

Objectives

Insomnia is commonly comorbid with chronic pain, and typically leads to worse outcomes. Two factors that could contribute to a cycle of pain and sleeplessness are pre-sleep cognitive arousal (repetitive thought processes) and low mood. This study aimed to examine how pain, sleep disturbance, mood, and pre-sleep cognitive arousal inter-relate, to determine whether low mood or pre-sleep cognitive arousal contribute to a vicious cycle of pain and insomnia.

Methods

Forty seven chronic pain patients completed twice daily diary measures and actigraphy for one week. Analyses investigated the temporal and directional relationships between pain intensity, sleep quality, time awake after sleep onset, anhedonic and dysphoric mood, and pre-sleep cognitive arousal. Fluctuations in predictor variables were used to predict outcome variables the following morning using mixed-effects modelling.

Results

For people with chronic pain, an evening with greater pre-sleep cognitive arousal (relative to normal) led to a night of poorer sleep (measured objectively and subjectively), lower mood in the morning, and a greater misperception of sleep (underestimating sleep). A night of poorer sleep quality led to greater pain the following morning. Fluctuations in pain intensity and depression did not have a significant influence on subsequent sleep.

Conclusions

For people with chronic pain, cognitive arousal may be a key variable exacerbating insomnia, which in turn heightens pain. Future studies could target cognitive arousal to assess effects on sleep and pain outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic pain affects approximately 20% of the population and is the leading cause of disability globally [1]. Whilst chronic pain can be treated with cognitive behavioural interventions, effect sizes are small and not all patients benefit [2]. To enhance treatments, it is imperative to understand the factors that maintain chronic pain and disability. One such factors is sleep disturbance. Sleep problems predict the development of chronic pain, and sleep deprivation is associated with increased pain and hyperalgesia in healthy people as well as people with chronic pain [3]. A vicious cycle can develop where pain and poor sleep may perpetuate each other. One way to explore the direction of such relationships is through diary studies, and this micro-longitudinal approach is widely accepted for assessing the temporal relationships between sleep and pain [4], and has also been used to assess the links between pain and depression [5].

Understanding the cognitions and emotions that may influence pain-related insomnia is critical, as they may be target variables in psychological treatment. One variable that has been linked to sleep disturbance is pre-sleep arousal, which comprises both cognitive arousal (rumination) and somatic (physiological) arousal [6]. Polysomnography studies show that pre-sleep cognitive arousal is associated with poorer sleep in healthy people [7] and insomnia patients [8]. Cross-sectional studies demonstrate that chronic pain patients who report more pre-sleep cognitive arousal also report greater sleep difficulties [9] and have poorer sleep efficiency [10]. Interestingly, excessive pre-sleep cognitive arousal may also result in an individual overestimating the magnitude of their sleep disturbance [11]. This ‘misperception of sleep’ has previously been documented amongst people with sleep problems and likely exacerbates worry about sleep [12]. However it is unclear whether sleep problems lead to cognitive arousal or vice versa. Another variable which could influence insomnia in people with chronic pain is low mood. Depression is a risk factor for chronic pain [13]; and chronic pain patients with depression have poorer function, poorer response to treatment and increased healthcare costs [14]. The direction of relationships between sleep, pain and depression are the topic of debate and so diary studies make a good methodology to explore these relationships.

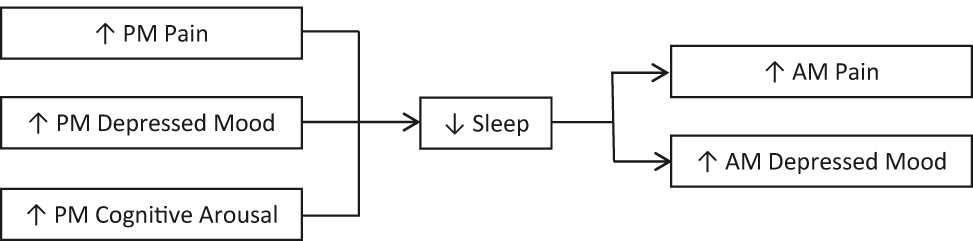

The aim of the present study was to investigate the temporal associations between pain, sleep, mood and pre-sleep cognitive arousal in chronic pain patients, using daily diary recordings and actigraphy. We expected that increased pain, depressed mood and pre-sleep cognitive arousal in the evening would lead to poorer sleep, which would lead to increased pain and depressed mood in the morning (see Figure 1 for a model demonstrating expected relationships).

Proposed model of relationships between pain, mood, pre-sleep cognitive arousal and sleep variables. PM, post-meridiem; AM, ante-meridiem.

Methods

Overview

47 chronic pain patients completed baseline questionnaires then monitored pain, mood, pre-sleep cognitive arousal and sleep over seven nights and eight days. Participants made twice daily ratings and wore an actiwatch to monitor sleep. The diary assessments were made in the evening before bed and every morning within 45 min of waking. The study received ethical approval from the University of Auckland Human Ethics Committee (IRB #9006) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Chronic pain patients attending The Auckland Regional Pain Service (an interdisciplinary pain centre in Auckland, New Zealand) were recruited during a routine clinic visit. Participants were required to be ≥18 years, have persistent condition, and literate and fluent in English. Exclusion from the study was indicated if the patient had a diagnosis of a severe psychiatric disorder (e.g. schizophrenia) or a sleep disorder other than insomnia (e.g. sleep apnoea, narcolepsy) documented in their medical records or noted during their routine appointment with a pain medicine specialist. 51 patients were recruited for this study and provided informed consent. Four participants dropped out from the study, leaving 47 completing the protocol. Reasons for discontinuing the study were: failure to complete measures, being in too much pain, and change of medication.

Measures

Demographics and clinical variables

Baseline assessments included demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, employment status and marital status) and medical information: duration of pain, diagnosis, medication use and type of pain (coded as specific musculoskeletal, nonspecific musculoskeletal, neuropathic, visceral, headache).

Questionnaires

In order to characterise the sample, participants completed the following baseline questionnaires: The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [15], The Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire-2 (SFMPQ2) [16], The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS21) [17], and The Pain Disability Index (PDI) [18].

Daily diary measures

Diaries were completed in pen and paper format with text message or phone reminders. To reduce burden, brief or single item scales were used.

Evening diary recordings: Participants rated their experiences on the following scales “since this morning”:

Pain intensity: 10 point numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 1 ‘no pain’ to 10 ‘worst pain ever’. The NRS is a widely used and validated measure of pain [19]. The traditional 0–10 scale was adjusted to 1–10 to be consistent with other scales in the diary.

Depressed mood: adapted version the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) [20]. This two-item scale has one item assessing anhedonic mood (“today I have felt little interest or pleasure in doing things”) and one item assessing dysphoric mood (“today I have felt down, depressed or hopeless”). Participants rated each from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much so). The original PHQ-2 utilises a six point scale but for the purposes of this study it was changed to a 10 point scale to be consistent with the other diary measures.

Morning diary recordings

Sleep-onset latency-subjective (SOL-S): how many minutes a participant believed it had taken them to fall asleep the previous night, based on their reported bedtime and estimate of the time they fell asleep.

Total sleep time-subjective (TST-S): how long a participant believed they slept for the previous night, calculated into minutes.

Sleep quality (SQ); a participant’s subjective rating of the quality of their sleep the previous evening was rated on a 10 point NRS from 1 ‘dreadful’ to 10 ‘wonderful’. Single item sleep quality scales have been demonstrated to have good reproducibility and validity with chronic pain patients [21].

Pain intensity (same as evening diary, except the time-frame was “since yesterday evening”)

Depressed mood (same as evening diary, except the time-frame was “since yesterday evening”).

Pre-sleep cognitive arousal: one item from the Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale [6]. This item (“As you were trying to go to sleep last night, thoughts kept running through your mind”) was rated on a 10 point NRS from 1 ‘not at all’ to 10 ‘very much so’ and has previously been used to measure pre-sleep cognitive arousal [10].

Participants also recorded what time they went to bed, what time they woke up and what time they got out of bed. These recordings were used to set the timeframe for the actigraphy assessment.

Actigraphy

The Mini-Mitter AW64 system was used to detect sleep-wake patterns by monitoring ambulatory activity. Participants were instructed to wear the actiwatch on their non-dominant wrist for the entire duration of the study period except when the watch could come in to contact with water. Good reliability between actigraphy and the gold standard of sleep assessment, polysomnography, has been documented (90% agreement on classification of epochs on healthy subjects) [22], however because actigraphy relies on movement to determine wakefulness, the accuracy of this method can be affected in individuals who have periods of motionless wakefulness. Cambridge Neurotechnology Sleep Analysis 5.5 was used to determine sleep parameters and actigraphy was cross-referenced to the times specified in the sleep diary. Actigraphy parameters included total sleep time-objective (TST-O; an actigraphic estimation of how long a participant was asleep for overall), wake-after-sleep-onset (WASO; an actigraphic estimation of how many minutes a participant was awake for during their sleep phase), and sleep onset latency-objective (SOL-O; an actigraphic estimation of how long it took for a participant to fall asleep once they had gone to bed).

Misperception of sleep

Misperception of sleep scores were calculated as the difference between subjective and objective sleep measures. Subjective scores (TST-S) were subtracted from objective scores (TST-O). Misperception of sleep has previously been measured in the home environment with actigraphy, using similar parameters [23].

Statistical analyses

Statistical power was calculated for this study with G*Power, using the Exact/Linear multiple regression: Random model test [24]. With an α level of 0.05, a power level of 0.80, an effect size of 0.23 (previous diary studies investigating the effect of sleep on pain have generally found medium to large effects), and a two-tailed test, 45 participants were required to obtain the desired power. In order to allow for possible attrition and missing data 51 participants were recruited. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25 and SAS 9.3. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the average diary and actigraphy variables. Variables were person mean-centred for further analyses. To calculate the mean-centred variables, an individual’s mean score (across 7 days) was subtracted from their daily score, so that a negative score would mean a lower score than usual, whereas a positive value would mean a higher score than usual on that variable. Mixed-effects modelling for repeated measures (MMRM, SAS PROC_MIXED), assuming random intercept and random slope, was used to analyse continuous outcomes (morning pain, sleep quality, objective sleep (WASO) and misperception of sleep). This was selected as variables were person mean-centred so that daily fluctuations in one variable were used to predict daily fluctuations in another, and the method preserves the repeated measures nature of the data. The within-subject errors were modelled using an unstructured (co)variance structure. The first order Kenward–Roger method was used to estimate the denominator degrees of freedom for fixed effects. The compound symmetry covariance matrix was used to estimate the between subject variation. Dependent variables (DVs) which were not normally distributed (pre-sleep cognitive arousal, morning dysphoric mood and morning anhedonic mood) were dichotomised (using a cutoff score of 5, i.e. ≥5 and <5) and analysed using generalised linear mixed effect models assuming random intercept and random slope. The within-subject errors were modelled using an unstructured (co)variance structure. The containment method was used to estimate the denominator degrees of freedom for fixed effects.

For each multilevel model, all predictor variables that made theoretical sense were included. The following variables were included in all the multilevel models: intercept, time (automatically included in SAS MMRM methods; this variable would indicate any effect of change over the 7-day period, and therefore was not expected to predict outcomes), age and gender (included as covariates), evening pain, mood and cognitive arousal. For the DVs morning pain and mood, subjective sleep quality was also included as a predictor. For the DVs morning pain, subjective sleep quality, morning mood and sleep misperception, WASO, an objective measure of sleep was also included as a predictor. WASO was selected as this is not dependent on total sleep opportunity, and only one objective sleep measure could be included due to multicollinearity. Use of sleep medication was not included as the models used fluctuations in IVs to predict fluctuations in DVs, and there were only five participants who had any variation in their use of sleep medication from day to day.

Results

Participants

The characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table 1. The sample included a majority of female participants and were predominantly of European descent. Participants had a mean pain duration of over 8 years and only a minority were employed fulltime. The mean insomnia severity score was above the threshold for ‘moderate insomnia’ (i.e. scores ≥ 15), and 61% of participants scored above this threshold. According to the DASS21, 46% scored above the threshold for ‘moderate depression’, 44% above the threshold for ‘moderate anxiety’, and 42% above the threshold for ‘moderate stress’. Mean scores for the diary measures and actigraphy are displayed in Table 2. This demonstrates that on average, participants slept for just less than 7 h per night. They also underestimated their total sleep time and overestimated the time to fall asleep, compared to actigraphy.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Characteristic | Mean, SD/N | Range/percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45.95 (10.88) | 25–67 |

| Pain duration, years | 8.23 (7.78) | 1–38 |

| Insomnia severity index, ISI | 16.97 (4.02) | 4–26 |

| ISI absence of insomnia | 1 | 2% |

| ISI subthreshold insomnia | 12 | 27% |

| ISI moderate insomnia | 27 | 60% |

| ISI severe insomnia | 5 | 11% |

| SFMPQ-2 pain | 4.34 (2.10) | 0.21–9.02 |

| DASS21 depression | 13.58 (9.91) | 0–38 |

| DASS21 anxiety | 10.56 (8.96) | 0–40 |

| DASS21 stress | 18.16 (9.54) | 0–36 |

| Pain disability index | 41.72 (14.00) | 6–67 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 19 | 40% |

| Female | 28 | 60% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| NZ European | 31 | 69% |

| European | 6 | 13% |

| Asian | 4 | 9% |

| Maori | 1 | 2% |

| Other | 3 | 7% |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 13 | 28% |

| Part time | 6 | 13% |

| Unemployed | 25 | 53% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 23 | 49% |

| Divorced | 2 | 4% |

| Widowed | 1 | 2% |

| De-facto relationship | 9 | 19% |

| Single | 10 | 21% |

| Pain diagnosis | ||

| Non-specific musculoskeletal | 11 | 23% |

| Specific musculoskeletal | 6 | 13% |

| Neuropathic | 19 | 40% |

| Visceral | 2 | 4% |

| Headache | 2 | 4% |

| Medication | ||

| Paracetamol | 21 | 45% |

| NSAIDs | 13 | 28% |

| AEDs | 20 | 43% |

| TCAs | 14 | 30% |

| Opioids | 20 | 43% |

| Sleep medication | 12 | 26% |

| SSRIs/SNRIs | 7 | 15% |

-

SFMPQ-2 Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire-2; DASS21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21; NZ, New Zealand; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories; AEDs, anti-epileptic drugs; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Note: Where percentages do not add up to a total of 100% for a variable missing data is indicated.

Mean descriptive statistics for diary and actigraphy data across the week of testing.

| Variable | Mean, SD |

|---|---|

| Morning pain | 4.89 (1.83) |

| Evening pain | 5.22 (1.76) |

| Morning anhedonia | 4.05 (1.82) |

| Evening anhedonia | 3.99 (1.86) |

| Morning dysphoria | 3.16 (1.98) |

| Evening dysphoria | 3.40 (2.03) |

| Cognitive arousal | 4.55 (2.86) |

| Sleep quality | 5.34 (1.21) |

| Total sleep time - subjective, min | 397.92 (66.52) |

| Total sleep time - objective, min | 419.82 (60.09) |

| Total sleep time discrepancy, min | 22.55 (45.93) |

| Wake after sleep onset, min | 43.79 (19.23) |

| Sleep onset latency -subjective, min | 49.25 (32.69) |

| Sleep onset latency -objective, min | 31.12 (23.81) |

| Sleep onset latency discrepancy, min | −17.86 (18.29) |

-

SD, standard deviation.

Predicting morning pain

A mixed-effects model assessed the influence of fluctuations in evening anhedonia, evening dysphoria, pre-sleep cognitive arousal, sleep quality and WASO on morning pain. The overall model proved to be significant according to the null model likelihood ratio test. The individual predictors that were significant included gender, evening pain and sleep quality (Table 3). Men experienced greater morning pain, and nights with higher evening pain and nights with poorer sleep quality were followed by greater morning pain. The estimate for sleep quality shown in Table 3 (−0.21) indicates that for every 1-point increase in sleep quality, morning pain scores reduced by an average of 0.21 points.

Results of mixed models analyses for all dependent variables.

| DV | AM pain | Sleep quality (subj) | WASO (obj) | AM anhedonia | AM dysphoria | Cognitive arousal | Sleep misperception | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | Est | SE | Pr>t | Est | SE | Pr>t | Est | SE | Pr>t | Est | SE | Pr>t | Est | SE | Pr>t | Est | SE | Pr>t | Est | SE | Pr>t |

| Intercept | 4.78 | 0.93 | <0.001 | 6.59 | 1.03 | <0.001 | 28.59 | 15.23 | 0.06 | −3.65 | 1.04 | 0.001 | −5.96 | 1.40 | <0.001 | −1.20 | 1.28 | 0.35 | −34.60 | 37.65 | 0.36 |

| Time | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.34 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 0.43 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 1.39 | 2.30 | 0.55 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.43 | <−0.01 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.18 |

| Gender | −0.76 | 0.37 | 0.047 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 7.08 | 6.07 | 0.25 | −0.04 | 0.33 | 0.90 | −0.65 | 0.37 | 0.08 | −0.72 | 0.49 | 0.14 | −15.25 | 14.79 | 0.31 |

| PM pain | 0.36 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.17 | −0.06 | 1.15 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.34 | −1.01 | 2.93 | 0.73 |

| PM dsyphoria | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.86 | −1.00 | 0.97 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 2.78 | 2.75 | 0.31 |

| PM anhedonia | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.59 | – | – | – | 0.71 | 1.07 | 0.51 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.55 | −2.24 | 2.49 | 0.37 |

| Cog arousal | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.69 | −0.16 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 0.71 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.07 | <0.001 | – | – | – | 5.28 | 1.84 | <0.01 |

| Sleep quality (subj) | −0.21 | 0.04 | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.62 | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.80 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| WASO (obj) | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.54 | −0.02 | <0.01 | <0.001 | – | – | – | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.37 | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

-

DV, dependent variable; Subj, subjective; WASO, wake after sleep onset, Obj, objective; IV, independent variable; Cog, cognitive; Est, estimate; SE, standard error, Pr > t, probability of obtaining t statistic by chance.

Indicates independent variable not included in analysis. Bold values indicate significant effects at p<0.05.

Predicting sleep

A mixed-effects model assessed whether fluctuations in evening pain, evening dysphoric mood, and pre-sleep cognitive arousal predicted subsequent sleep quality. Anhedonic mood was not entered as including this variable led to a poor model, and the variable did not demonstrate any predictive relationship with sleep. Age, gender, time and WASO were entered as covariates. The overall model proved to be significant according to the null model likelihood ratio test. Contrary to hypotheses, evening pain and evening depressed mood were not significant predictors of sleep quality but, consistent with hypotheses, pre-sleep cognitive arousal was, even after controlling for objective measures of sleep (WASO, which was also a significant predictor) (Table 3). Nights with greater pre-sleep cognitive arousal were associated with poorer sleep quality and the estimate in Table 3 of −0.16 indicates that for every one point increase in cognitive arousal, sleep quality reduced by an average of 0.17 points. Another model was created using the same predictor variables to explain WASO. Again, the null model likelihood ratio test found that the overall model had a significantly better fit than the null model. Consistent with the findings for sleep quality, pre-sleep cognitive arousal proved to be the only significant predictor of WASO. Evenings with more pre-sleep cognitive arousal were followed by more time awake that night (Table 3).

Predicting morning mood

To test for the influence of fluctuations in sleep, pain and cognitive arousal on mood, two mixed-effects models were conducted. In the first model, morning anhedonic mood was the dependent variable, and the predictor variables included fluctuations in evening pain, anhedonic and dysphoric mood, pre-sleep cognitive arousal, sleep quality, and WASO. The model also controlled for age and gender. Anhedonic mood the previous night and pre-sleep cognitive arousal were both significant predictors of morning anhedonic mood. The same variables were also used in the second mixed-effects model to predict morning dysphoric mood. Similarly, the variables that were significant predictors were dysphoric mood the previous night and pre-sleep cognitive arousal (see Table 3). Evenings with more dysphoric mood and with more pre-sleep cognitive arousal were followed by more dysphoric mood in the morning.

Predicting pre-sleep cognitive arousal

A mixed-effects model was used to determine whether fluctuations in mood influenced pre-sleep cognitive arousal. Age, gender and pain intensity were included as covariates. The overall model proved to be significant according to the null model likelihood ratio test. Contrary to predictions, neither anhedonic nor dysphoric mood were significant predictors of pre-sleep cognitive arousal (Table 3).

Predicting the misperception of sleep

A mixed effects model was created to determine predictors of the misperception of total sleep time. Fluctuations in evening pain, anhedonic mood and dysphoric mood were entered as predictors. Age, gender and WASO were entered as covariates. The overall model proved to be significant according to the null model likelihood ratio test. Pre-sleep cognitive arousal was a significant predictor, even after controlling for WASO (which was also a significant predictor) (Table 3). This demonstrates that nights with more time spent awake and evenings with greater pre-sleep cognitive arousal were followed by a greater underestimation of the amount of sleep in the morning.

Discussion

Main findings

The current study had several key findings. First, poorer sleep at night was followed by greater pain in the morning. Second, evening pain did not predict sleep, so an evening with more intense pain did not disrupt sleep more than usual. Instead, poor sleep was predicted by greater pre-sleep cognitive arousal and this was true for both objective and subjective measures of sleep. In fact, evenings characterised by greater than usual cognitive arousal led not only to poorer sleep, but also to greater underestimations of sleep time, and lower mood in the morning. However daily fluctuations in mood had little influence on subsequent sleep or pain.

Pain and sleep

We found that although sleep quality predicted pain the next morning, evening pain did not appear to influence sleep. Several previous diary studies have demonstrated bidirectional relationships between pain and sleep disturbance [25], [26], but our results are consistent with a number of previous diary studies showing that whilst sleep predicted pain, pain did not predict sleep [27], [28], [29]. Overall the pain and sleep literature demonstrates a stronger and more consistent influence of sleep on pain than the influence of pain on sleep [10], with experimental and longitudinal studies also demonstrating the consistent influence of sleep on pain [3]. There are a number of mechanisms by which sleep can influence pain; for example sleep influences opioid systems and dopaminergic signalling, inflammatory processes, and mood, which can in turn influence pain [3], [30]. Pain may also be influenced by circadian rhythms, which could explain this association [31].

Pre-sleep cognitive arousal

The results from this study highlight pre-sleep cognitive arousal as an important process in the pain-sleep relationship. Evenings with greater rumination were followed by poorer sleep, the perception that sleep was even worse than it was, and lower mood the following day. These findings are consistent with the previous literature, as the influence of pre-sleep cognitive arousal on sleep has been demonstrated previously [10], though this is the first diary study in a general chronic pain sample. The finding also supports the cognitive theory of insomnia which suggests that excessive arousal is expressed as rumination about lack of sleep [32]. Interestingly, some research has assessed the thought content of sleepless people with chronic pain, and these studies suggest that worry about pain and about sleep itself may be important for this population [33], [34]. Worry about sleep is also an important predictor of sleep in insomnia patients [8], but this effect may be exaggerated in people with chronic pain, who may worry about the effect of poor sleep on their subsequent pain. There may be benefits of targeting pre-sleep cognitive arousal (and perhaps worry about pain and sleep in particular) in treatments for pain and sleep.

Role of mood

We hypothesised that there would be bidirectional relationships between mood and pain and between mood and sleep, in keeping with previous studies [10] and theoretical hypotheses [3]. However our data revealed that daily fluctuations in mood did not appear to influence fluctuations in subsequent sleep or pain, which could indicate that any influence of mood occurs over longer time periods than would be captured in a diary study. Also, it might be that the mood measure in this study (which focussed on dysphoric and anhedonic mood), did not adequately capture the mood state which might influence pain and sleep (which could be anger or anxiety, for example). Alternatively the present results lend more support to the role of pre-sleep cognitive arousal and it is possible that mood does not play as strong a role in pain fluctuations as previously suggested.

Clinical implications

There is now a strong and consistent body of experimental, longitudinal, micro-longitudinal and cross-sectional research demonstrating that poor sleep leads to more pain. For people with chronic pain, treatments that improve sleep may need to be prioritised not only for their beneficial effects on sleep, but in order to better manage pain. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is recommended as a first line treatment for insomnia [35], and is also the mainstay of chronic pain management [36]. It is possible to combine CBT for both pain and insomnia, and this appears to improve outcomes [9], [37]. The current study suggests that one key variable to target in CBT for people with chronic pain is pre-sleep cognitive arousal. Research of mindfulness course attendees shows that mindfulness meditation can reduce pre-sleep cognitive arousal [38], though this has not been investigated for sleep specifically in chronic pain populations. It is also likely that cognitive therapy techniques could reduce pre-sleep cognitive arousal, in keeping with cognitive models of insomnia.

Limitations & future directions

There are some limitations to this study. First, the sample size was relatively small and were recruited from a tertiary referral pain centre so typically had longstanding and severe pain and disability, which reduces the generalisability of the findings. Many of the assessments were made by subjective self-report. It is therefore possible that variables rated at the same time-point may share inflated associations. Further, although the data demonstrate statistical significance, some of the effect sizes were small. For example, for each point improvement in sleep quality, morning pain was just 0.21 points lower. Additionally, actigraphic assessments of sleep may have overestimated sleep and underestimated wakefulness due to motionless periods of wakefulness [39]. However, actigraphy is considered to be appropriate when assessing temporal fluctuations in sleep rather than absolute quantities [40]. Finally, causation cannot be assumed but repeated measurements using a time lagged design helps to establish temporal order within a naturalistic setting. Although we did not include medication use in statistical models this was unnecessary as the analyses predicted daily fluctuations in variables of interest, only five of the 47 participants reported any variation in their use of sleep medication from day to day.

Future research could aim to replicate this study, examining the contribution of other negative emotions (for example, stress and anxiety) and fatigue. The influence of positive emotions in promoting a virtuous cycle or improvements in pain, and sleep, is another area for investigation. Research on the potential psychological and biological mechanisms underlying these relationships is important, which may include measurement of endogenous pain modulation, opioidergic or dopaminergic mechanisms. Finally, research could also test interventions that target pre-sleep cognitive arousal as a method for improving sleep and pain in people with chronic pain.

Conclusions

Pre-sleep cognitive arousal appears to be a key variable which exacerbates sleep disturbance in people with chronic pain, which in turn leads to heightened pain intensity. Both the findings that (a) pre-sleep cognitive arousal leads to poorer sleep, and (b) sleep disturbance leads to greater pain, involve clinically modifiable variables and can be further explored in chronic pain treatment. This means that intervening on sleep may be a key component of effective pain management, and sleep interventions may be more effective if they specifically address pre-sleep cognitive arousal. Future research may wish to test these mechanisms in intervention studies.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the staff at The Auckland Regional Pain Service for supporting this research.

-

Research funding: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board.

References

1. GBD Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602.10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Williams, AC, Eccleston, C, Morley, S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD00407.10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Finan, PH, Goodin, BR, Smith, MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain 2013;14:1539–52.10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Smith, MT, Nasir, A, Campbell, CM, Okonkwo, R. Sleep disturbance and chronic pain. In: Espie, CA, Morin, CM, editors The Oxford Book of Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376203.013.0040Suche in Google Scholar

5. Feldman, SI, Downey, G, Schaffer-Neitz, R. Pain, negative mood, and perceived support in chronic pain patients: a daily diary study of people with reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:776.10.1037//0022-006X.67.5.776Suche in Google Scholar

6. Nicassio, PM, Mendlowitz, DR, Fussell, JJ, Petras, L. The phenomenology of the pre-sleep state: the development of the pre-sleep arousal scale. Behav Res Ther 1985;23:263–71.10.1016/0005-7967(85)90004-XSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Wuyts, J, De Valck, E, Vandekerckhove, M, Pattyn, N, Bulckaert, A, Berckmans, D, et al.. The influence of pre-sleep cognitive arousal on sleep onset processes. Int J Psychophysiol 2012;83:8–15.10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.09.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Spiegelhalder, K, Regen, W, Feige, B, Hirscher, V, Unbehaun, T, Nissen, C, et al.. Sleep-related arousal versus general cognitive arousal in primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:431–7.10.5664/jcsm.2040Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Tang, NKY, Goodchild, CE, Salkovskis, PM. Hybrid cognitive-behaviour therapy for individuals with insomnia and chronic pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2012;50:814–21.10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Tang, NKY, Goodchild, CE, Sanborn, AN, Howard, J, Salkovskis, PM. Deciphering the temporal link between pain and sleep in a heterogeneous chronic pain patient sample: a multilevel daily process study. Sleep 2012;35:675–97.10.5665/sleep.1830Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Tang, NKY, Harvey, AG. Effects of cognitive arousal and physiological arousal on sleep perception. Sleep 2004;27:69–78.10.1093/sleep/27.1.69Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Harvey, AG, Tang, NKY. (Mis)perception of sleep in insomnia: a puzzle and a resolution. Psychol Bull 2012;138:77–101. 2011/10/03.10.1037/a0025730Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Currie, SR, Wang, J. More data on major depression as an antecedent risk factor for first onset of chronic back pain. Psychol Med 2005;35:1275–82.10.1017/S0033291705004952Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Holmes, A, Christelis, N, Arnold, C. Depression and chronic pain. Med J Aust 2012;1:17–20.10.5694/mjao12.10589Suche in Google Scholar

15. Bastien, CH, Vallières, A, Morin, CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2:297–307.10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Dworkin, RH, Turk, DC, Revicki, DA, Harding, G, Coyne, KS, Peirce-Sandner, S, et al.. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). PAIN® 2009;144:35–42.10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Lovibond, SH, Lovibond, PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995.10.1037/t01004-000Suche in Google Scholar

18. Chibnall, JT, Tait, RC. The pain disability index: factor structure and normative data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75:1082–6.10.1016/0003-9993(94)90082-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Ferreira-Valente, MA, Pais-Ribeiro, JL, Jensen, MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 2011;152:2399–404.10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, Williams, JBW. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–92.10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3CSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Cappelleri, JC, Bushmakin, AG, McDermott, AM, Sadosky, AB, Petrie, CD, Martin, S. Psychometric properties of a single-item scale to assess sleep quality among individuals with fibromyalgia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:54.10.1186/1477-7525-7-54Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Van Someren, EJW. Actigraphic monitoring of sleep and circadian rhythms. In: Montagna, P, Chokroverty SBT-H of CN, editors Sleep Disorders Part I. Elsevier; 2011. pp. 55–63.10.1016/B978-0-444-52006-7.00004-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Tang, NKY, Harvey, AG. Correcting distorted perception of sleep in insomnia: a novel behavioural experiment? Behav Res Ther 2004;42:27–39.10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00068-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Faul, F, Erdfelder, E, Lang, AG, Buchner, AG. *Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91.10.3758/BF03193146Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. O’Brien, EM, Waxenberg, LB, Atchison, JW, Gremillion, HA, Staud, RM, McCrae, CS, et al.. Intraindividual variability in daily sleep and pain ratings among chronic pain patients: bidirectional association and the role of negative mood. Clin J Pain 2011;27:425–33.10.1097/AJP.0b013e318208c8e4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Alsaadi, SM, McAuley, JH, Hush, JM, Lo, S, Bartlett, DJ, Grunstein, RR, et al.. The bidirectional relationship between pain intensity and sleep disturbance/quality in patients with low back pain. Clin J Pain 2014;30:755–65.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000055Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Davin, S, Wilt, J, Covington, E, Scheman, J. Variability in the relationship between sleep and pain in patients undergoing interdisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic pain. Pain Med 2014;15:1043–51.10.1111/pme.12438Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Gerhart, JI, Burns, JW, Post, KM, Smith, DA, Porter, LS, Burgess, HJ, et al.. Relationships between sleep quality and pain-related factors for people with chronic low back pain: tests of reciprocal and time of day effects. Ann Behav Med 2017;51:365–75.10.1007/s12160-016-9860-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Huo, M, Ng, YT, Fuentecilla, JL, Leger, K, Charles, ST. Positive encounters as a buffer: pain and sleep disturbances in older adults’ everyday lives. J Aging Health 2020;33:75–85.10.1177/0898264320958320Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Herrero Babiloni, A, De Koninck, BP, Beetz, G, De Beaumont, L, Martel, MO, Lavigne, GJ. Sleep and pain: recent insights, mechanisms, and future directions in the investigation of this relationship. J Neural Transm 2020;127:647–60.10.1007/s00702-019-02067-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Palada, V, Gilron, I, Canlon, B, Svensson, CI, Kalso, E. The circadian clock at the intercept of sleep and pain. Pain 2020;161:894–900.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001786Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Harvey, AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther 2002;40:869–93.10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00061-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Smith, MT, Perlis, ML, Carmody, TP, Smith, MS, Giles, DE. Presleep cognitions in patients with insomnia secondary to chronic pain. J Behav Med 2001;24:93–114.10.1023/A:1005690505632Suche in Google Scholar

34. Byers, HD, Thomas, S, Lichstein, K. Cognitive arousal and sleep complaints in chronic pain. Cognit Ther Res 2011;36:149–55.10.1007/s10608-011-9420-9Suche in Google Scholar

35. Riemann, D, Baglioni, C, Bassetti, C, Bjorvatn, B, Dolenc Groselj, L, Ellis, JG, et al.. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 2017;26:675–700.10.1111/jsr.12594Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Ehde, DM, Dillworth, TM, Turner, JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014;69:153–66.10.1037/a0035747Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Pigeon, WR, Moynihan, J, Matteson-Rusby, S, Jungquist, CR, Xia, Y, Tu, X, et al.. Comparative effectiveness of CBT interventions for co-morbid chronic pain & insomnia: a pilot study. Behav Res Ther 2012;50:685–9.10.1016/j.brat.2012.07.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Hassirim, Z, Lim, ECJ, Lo, JC, Lim, J. Pre-sleep cognitive arousal decreases following a 4-week introductory mindfulness course. Mindfulness 2019;10:2429–38.10.1007/s12671-019-01217-4Suche in Google Scholar

39. Hauri, PJ, Wisbey, J. Wrist actigraphy in insomnia. Sleep 1992;15:293–301.10.1093/sleep/15.4.293Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Ancoli-Israel, S, Cole, R, Alessi, C, Chambers, M, Moorcroft, W, Pollak, CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep 2003;26:342–92.10.1093/sleep/26.3.342Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comment

- When surgery prompts discontinuation of opioids

- Systematic Reviews

- The efficacy of botulinum toxin A treatment for tension-type or cervicogenic headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials

- Pain medication use for musculoskeletal pain among children and adolescents: a systematic review

- Topical Review

- Erector spinae plane block in acute interventional pain management: a systematic review

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Maternal haemodynamics during labour epidural analgesia with and without adrenaline

- Cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Portuguese breakthrough pain assessment tool with cancer patients

- Opioid availability statistics from the International Narcotics Control Board do not reflect the medical use of opioids: comparison with sales data from Scandinavia

- Granisetron vs. lidocaine injection to trigger points in the management of myofascial pain syndrome: a double-blind randomized clinical trial

- Pain experience in an aging adult population during a 10-year follow-up

- Pre-sleep cognitive arousal exacerbates sleep disturbance in chronic pain: an exploratory daily diary and actigraphy study

- Psychometric assessment of the Swedish version of the injustice experience questionnaire among patients with chronic pain

- Exploring how people with chronic pain understand their pain: a qualitative study

- Pain, cognition and disability in advanced multiple sclerosis

- Disability, burden, and symptoms related to sensitization in migraine patients associate with headache frequency

- Observational Studies

- Health-related quality of life in tension-type headache: a population-based study

- Is this really trigeminal neuralgia? Diagnostic re-evaluation of patients referred for neurosurgery

- Does the performance of lower limb peripheral nerve blocks differ among orthopedic sub-specialties? A single institution experience in 246 patients

- Risk of infection within 4 weeks of corticosteroid injection (CSI) in the management of chronic pain during a pandemic: a cohort study in 216 patients

- Reliability and smallest detectable change of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with chronic low back pain

- Associations of multiple (≥5) chronic conditions among a nationally representative sample of older United States adults with self-reported pain

- Original Experimental

- Circulating long non-coding RNA signature in knee osteoarthritis patients with postoperative pain one-year after total knee replacement

- Educational Case Report

- Analgesic effect of paired associative stimulation in a tetraplegic patient with severe drug-resistant neuropathic pain: a case report

- Short Communication

- Examining resting-state functional connectivity in key hubs of the default mode network in chronic low back pain

- Book Review

- Emmanuel Bäckryd and Mads U. Werner: Långvarig smärta – SMÄRTMEDICIN VOL. 2

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comment

- When surgery prompts discontinuation of opioids

- Systematic Reviews

- The efficacy of botulinum toxin A treatment for tension-type or cervicogenic headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials

- Pain medication use for musculoskeletal pain among children and adolescents: a systematic review

- Topical Review

- Erector spinae plane block in acute interventional pain management: a systematic review

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Maternal haemodynamics during labour epidural analgesia with and without adrenaline

- Cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Portuguese breakthrough pain assessment tool with cancer patients

- Opioid availability statistics from the International Narcotics Control Board do not reflect the medical use of opioids: comparison with sales data from Scandinavia

- Granisetron vs. lidocaine injection to trigger points in the management of myofascial pain syndrome: a double-blind randomized clinical trial

- Pain experience in an aging adult population during a 10-year follow-up

- Pre-sleep cognitive arousal exacerbates sleep disturbance in chronic pain: an exploratory daily diary and actigraphy study

- Psychometric assessment of the Swedish version of the injustice experience questionnaire among patients with chronic pain

- Exploring how people with chronic pain understand their pain: a qualitative study

- Pain, cognition and disability in advanced multiple sclerosis

- Disability, burden, and symptoms related to sensitization in migraine patients associate with headache frequency

- Observational Studies

- Health-related quality of life in tension-type headache: a population-based study

- Is this really trigeminal neuralgia? Diagnostic re-evaluation of patients referred for neurosurgery

- Does the performance of lower limb peripheral nerve blocks differ among orthopedic sub-specialties? A single institution experience in 246 patients

- Risk of infection within 4 weeks of corticosteroid injection (CSI) in the management of chronic pain during a pandemic: a cohort study in 216 patients

- Reliability and smallest detectable change of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with chronic low back pain

- Associations of multiple (≥5) chronic conditions among a nationally representative sample of older United States adults with self-reported pain

- Original Experimental

- Circulating long non-coding RNA signature in knee osteoarthritis patients with postoperative pain one-year after total knee replacement

- Educational Case Report

- Analgesic effect of paired associative stimulation in a tetraplegic patient with severe drug-resistant neuropathic pain: a case report

- Short Communication

- Examining resting-state functional connectivity in key hubs of the default mode network in chronic low back pain

- Book Review

- Emmanuel Bäckryd and Mads U. Werner: Långvarig smärta – SMÄRTMEDICIN VOL. 2