Military veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder: results from a chronic pain management programme

-

Jannie Van Der Merwe

, Suzanne Brook

Abstract

Background and aims

There is very little published evaluation of the treatment of military veterans with chronic pain, with or without post-traumatic stress disorder. Few clinical services offer integrated treatment for veterans with chronic pain and PTSD. Such veterans experience difficulty in accessing treatment for either condition: services may consider each condition as a contraindication to treatment of the other. Veterans are therefore often passed from one specialist service to another without adequate treatment. The veteran pain management programme (PMP) in the UK was established to meet the needs of veterans suffering from chronic pain with or without PTSD; this is the first evaluation.

Methods

The PMP was advertised online via veteran charities. Veterans self-referred with accompanying information from General Practitioners. Veterans were then invited for an inter-disciplinary assessment and if appropriate invited onto the next PMP. Exclusion criteria included; current severe PTSD, severe depression with active suicidal ideation, moderate to severe personality disorder, or who were unable to self-care in the accommodation available. Treatment was by a team of experienced pain management clinicians: clinical psychologist, physiotherapist, nurse, medical consultant and psychiatrist. The PMP was delivered over 10 days: five residential days then five single days over the subsequent 6 months. The PMP combines cognitive behavioural treatment, which has the strongest evidence base, with more recent developments from mindfulness-based CBT for pain and compassion-focused therapy. Standard pain management strategies were adapted to meet the specific needs of the population, recognising the tendency to use demanding activity to manage post-traumatic stress symptoms. Domains of outcome were pain, mood, function, confidence and changes in medication use.

Results

One hundred and sixty four military veterans started treatment in 19 programmes, and 158 completed. Results from those with high and low PTSD were compared; overall improvements in all domains were statistically significant: mood, self-efficacy and confidence, and those with PTSD showed a reduction (4.3/24 points on the IES-6). At the end of the programme the data showed that 17% reduced opioid medication and 25% stopped all opioid use.

Conclusions

Veterans made clinically and statistically significant improvements, including those with co-existing PTSD, who also reduced their symptom level. This serves to demonstrate the feasibility of treating veterans with both chronic pain and PTSD using a PMP model of care.

Implications

Military veterans experiencing both chronic pain and PTSD can be treated in a PMP adapted for their specific needs by an experienced clinical team.

1 Introduction

There is a high prevalence of co-morbid chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in military veterans seeking pain management: 49% of patients at a US Veterans’ Administration (VA) health care facility [1]; 21.7% of Croatian homeland war veterans [2]; and in US Armed Forces deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan, 81.5% reported chronic pain and 68.2% PTSD [3]. Williamson et al. [4] quotes a Ministry of Defence statistic that up to 60% of medical discharges within the United Kingdom Armed Forces (UK AF) between 2001 and 2014 were for musculoskeletal injuries with 4% of regular personnel suffering from PTSD and 9% of deployed ex-regular veterans were found to experience PTSD. Comorbidity between medical conditions and mental health is significant, with medical conditions correlating with anxiety and mood disorders, including work loss. A multidisciplinary team approach as the treatment of choice is being suggested [5], [6].

There is growing interest in the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and identifying effective treatments when these conditions present together. Psychological models proposed to explain the association of chronic pain and post-traumatic stress remain largely hypothetical [7], [8], [9]. The recognition of interaction between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress has generated recommendations for integrated treatment [10], [11], [12], for example, behavioural activation using a collaborative approach involving primary care, mental health, and other clinicians [12], Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT), interdisciplinary pain programmes, and exposure-based interventions [11]. There are some important differences from standard chronic pain programmes, particularly the need to address the common myth among veterans of “no pain, no gain”, and their strategic use of pain to distract from post-traumatic stress symptoms [13].

Guidelines exist for treatment of chronic pain [14], [15] and for post-traumatic symptomatology [16], [17], but few studies report on combined and simultaneous treatment of chronic pain and PTSD. For example, Otis et al. [18] describes an integrated treatment model, combining cognitive processing therapy (designed for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and includes elements of CBT) and CBT for pain management in a trial for integrated treatment of veterans with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Despite a high drop-out rate, the integrated treatment model appears to be beneficial and further clinical trials and evaluation are in progress.

Health services often lack the expertise to assess and manage pain conditions in the veteran population [19] or to fully understand the complexities of comorbid chronic pain and PTSD [1], [10]. Veterans with both chronic pain and post-traumatic stress symptoms may be offered the treatments in sequence, but there are differences in clinical opinion on the best order of treatment. This can result in veterans being excluded from each service until their other problem is resolved, meaning they receive no treatment and the experience itself is likely to increase negative mood. Few data exist on UK veterans with comorbid chronic pain and post-traumatic stress symptoms [7], with studies mainly focused on mental health or musculoskeletal problems [4], [20], [21], but not the combination, which is common [22], [23], [24]. Data are not available on support and treatment provided by local services for UK veterans with physical health problems, such as musculoskeletal pain, and some individuals may require long-term support [4].

The first interdisciplinary veteran-specific pain management programme (PMP) in the UK was established with charitable funding in a private hospital in London in 2015. This study reports on the first 158 patients, investigating the differences in clinical outcomes between those with and without PTSD.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Veterans self-referred to the pain service in response to advertisements in service media, for example, Help4Heroes. Supporting information was provided by their General Practitioners (GPs) alongside proof of military service. An assessment appointment was offered once sufficient information had been obtained of the patient’s medical care to date. Referred patients were not assessed if they were currently undergoing medical treatment or misused alcohol or non-prescribed drugs.

Veterans were individually assessed by a consultant in pain medicine, consultant psychiatrist, consultant clinical psychologist, and a physiotherapist specialising in chronic pain; these clinicians then met to reach consensus on the patient’s suitability. Some veterans were referred for additional medical or psychological treatment prior to attending the PMP, including those with current complex PTSD symptoms, severe depression with active suicidal ideation, moderate to severe personality disorder, or who were unable to self-care in the accommodation available. The diagnosis of PTSD was made at initial assessment by the consultant psychiatrist and consultant psychologist using DSM-5 [25] and the ICD-10 [26] criteria. Veterans attending the assessment completed a brief self-report scale of posttraumatic stress symptoms: The Impact of Event Scale-6, in which a score of 10 or more of a maximum 24 suggests clinically significant post-traumatic symptoms. Clinical correspondence from mental health experts, including diagnoses and opinions regarding veterans attending the assessment, was also considered in assigning the diagnosis.

2.2 Programme content and delivery

Programmes were run over 10 days: five sequential residential days (with hotel accommodation) followed by five single days over the following 4–6 months, a total of 60 h. Each programme had a maximum of 10 veterans; in the 19 programmes reported here, 164 veterans started treatment, of whom 158 completed. Irregularities of patient flow and dropout shortly before the start meant that fewer than 10 patients started some programmes.

PMPs were delivered by clinical staff with extensive experience in delivering specialist pain management programmes, ensuring an empathic and responsive clinical environment was maintained throughout. Essential to the optimal delivery of the programme was the consistency of the staff members’ approach, producing a united clinical team and ensuring adequate time for clinical discussion and supervision. In addition, given the complex nature of the study population, extra support services were in place to manage patient risk, particularly at times when the service is out of hours.

The content of the PMP conforms to UK guidelines [15] and to current practice in the UK. The PMP treatment model combines cognitive behavioural therapy, which has the strongest evidence base [27], with more recent developments drawn from mindfulness-based CBT for pain [28] and compassion-focused therapy [29]. PMP content was adapted to meet the specific needs of the veteran population experiencing PTSD (see Table 1). For example, medication rationalisation, which includes avoiding the unnecessary duplication of medications from the same class, utilising by-the-clock regime rather than as required regime where possible; ensuring recommended daily doses are not exceeded; and reducing dose or discontinuing medication. Also strategies to encourage return to meaningful activities, in some cases by pacing gradual increase, and in others to reduce overactivity driven by the attempt to distract from PTSD symptomatology or to achieve overambitious physical goals.

PMP content.

| Introductory session: Interactive session where veterans describe the impact of chronic pain on their lives |

| Pain science: Information on pain physiology, mechanisms and neuroscientific explanation of pain and of its impact on mood and activity |

| Physiotherapy-led sessions: The effects of pain on activity (including exercise, mindful movement, and meaningful activities) explored with emphasis on the impact on mood and post-traumatic stress symptoms, especially the tendency towards an all or nothing approach to activity |

| Psychology-led sessions: The correlation between psychology and pain physiology is explored. Veterans are introduced to psychological strategies aiming to reduce pain-associated distress, reduce self-blame and enhance emotional regulation |

| Mindfulness practice sessions: Each day starts with a brief mindfulness-based CBT exercise. In addition, veterans are introduced to a mindfulness body scan technique |

| Nurse-led sessions: Information is provided about common pain medications, their mechanisms of action, effectiveness for chronic pain, and side effects. Veterans are offered the opportunity to rationalise and reduce their pain-related medication. Information is also provided about pain and sleep, and sleep hygiene |

| Pain flare-up: The causes and management of increased pain are discussed, and veterans encouraged to create a personalised flare-up plan |

| Friends and family day: The veterans’ significant others are invited to attend a single day to gain an understanding of the programme and how to support them after discharge |

2.3 Data collection

Data were collected at assessment and on days 1, 5, 8 and 10 (last day) of the PMP. Veterans completed a pack of questionnaires covering general mental health (CORE outcome measure: CORE) and post-traumatic stress symptoms (Impact of Events Scale: IES-6), pain and interference by pain (Brief Pain Inventory: BPI), pain anxiety (Pain Catastrophizing Scale: PCS), and confidence in being active despite pain (Pain Self-Efficacy Scale: PSEQ). Information was also collected on medication use.

2.3.1 Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

The BPI assesses severity of pain with four questions, on least, worst, average and current pain, each scored 0–10 where 0 is “no pain” and 10 is “pain as bad as you can imagine”. Only worst and average pain are reported here. It also assesses interference of pain with seven areas of life, including work, sleep, social life, and enjoyment of life, again providing a 0–10 scale where 0 is “does not interfere” and 10 is “interferes completely”. The mean of these is used as a score of pain interference.

Originally developed in cancer pain, it functions well for chronic pain [30], [31], with acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α 0.85 for pain and 0.88 for interference), a stable structure, and sensitivity to change with treatment [32]. The form has a copyright and used without charge by permission from the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (https://www4.mdanderson.org/symptomresearch/index.cfm).

2.3.2 CORE outcome measure (Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations CORE)

This is a 34-item scale, developed in the UK, covering all aspects of mental health for generic evaluation of change over psychological therapies. It has a 10-item short version and a 34-item long version [33]. Items are worded negatively or positively, and are answered in terms of how often they applied in the last week, on a 5-point scale from 0=“not at all” to 4=“all the time”. Internal reliability is adequate (Cronbach α 0.82) (CORE manual). It is copyrighted and free to use (http://www.coreims.co.uk/About_Core_System_Outcome_Measure.html). Both short and long versions were used in the Veterans’ PMP: the CORE-10 is less burdensome for patients, but the CORE-34 covers risk of self-harm or violence to others in more detail. For those completing CORE-34, the CORE-10 items were extracted and the scoring protocol for CORE-10 followed.

2.3.3 Impact of Events Scale (IES-6)

There are multiple versions of the IES. The Veterans’ PMP uses the six-item civilian version [34]. The items cover intrusions, vigilance, and the effects of the symptoms, and responses indicate the extent of distress caused by the symptoms, from 0=“not at all” to 4=“extremely”. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) is 0.80, and it appears to be sensitive to treatment change and reasonably well related to clinical diagnosis [34], [35], [36].

2.3.4 Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)

The term catastrophising describes a negative bias in thinking about pain, and thereby associated with a negative emotional response to pain [37], [38]. It consists of 13 statements, such as “It’s awful and I feel that it overwhelms me”, with response options of “not at all”, “to a slight degree”, “to a moderate degree”, “to a great degree”, and “all the time”, scored 0–4, respectively. Responses are added for a possible total from 0 to 52. Internal consistency from the largest sample is Cronbach α 0.92 [39]. The scale is copyrighted (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/pain-catastrophizing) but free for use in research.

2.3.5 Pain Self-Efficacy Scale (PSEQ)

Self-efficacy, or confidence in activity despite pain, is assessed with 10 items, each scored 0–6, where 0 is “not at all confident” and 6 is “completely confident”. Items include daily household activities, social life, work, leisure activities, and coping with pain without medication [40]. The range of the total is 0–60, with higher scores representing greater confidence. Internal consistency is excellent (Cronbach’s α is 0.92), and it has shown sensitivity to change [41]. There is no copyright and the PSEQ is free to use.

2.4 Data analysis

Missing data were handled as follows: for the IES, items that were not filled out were scored as zero; for the CORE-10 the protocol for missing items was followed; for other scales where no more than 10% of scores were missing, the total was prorated using the mean of completed items. Other scale scores were calculated according to standard methods as totals or means.

Repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted in SPSS (version 23) for each of the outcomes; cases were excluded list-wise in any analysis if they were missing data but included in other analyses where they completed the measures.

3 Results

Of the 164 veterans who started treatment, six dropped out; two because of employment demands, three for medical or mental health reasons, and one unknown. Information concerning the 158 veterans who completed treatment is detailed in Table 2. Overall attendance of sessions was 88%, with sessions missed for similar reasons as for drop out, flare-up of post-traumatic stress symptoms or because of difficulties with travel from distant parts of the country for single days.

Information collected at assessment n=158.

| Sex | 142 males, 16 females |

| Duration of pain mean and range | 15.6 years, 1–48 |

| Age mean and range | 45.3 years, range 27–70 |

| Pain site – 99% more than one | |

| Spinal | 86 |

| Lower limb | 96 |

| Upper limb | 45 |

| Head/face | 10 |

| Abdominal/Pelvic | 11 |

| Total body pain (5 sites or more) | 23 |

| Current employment status | |

| Not working | 71 |

| Work full time (paid or unpaid) | 30 |

| Work part time (paid or unpaid) | 26 |

| Employed, off work sick | 10 |

| Retired | 11 |

| In training | 5 |

| Missing | 5 |

| Rank | |

| Officer | 19 |

| Non officer | 123 |

| Doctors/nurses/police force | 16 |

| Pain started | |

| During service including training | 110 |

| Not during service | 40 |

| Missing | 8 |

| Partnership status | |

| Married/living with partner | 108 |

| Not married/living with partner | 47 |

| Missing | 3 |

Of the 148 veterans that were deployed, most served in Afghanistan and Iraq, The Falkland Islands and Northern Ireland. Sixteen veterans were not deployed during their service. All veterans reported pain in more than one site.

Baseline scores for the 158 who completed treatment are divided according to diagnosis of PTSD (Table 3). Clinical diagnosis of post-traumatic symptoms were borne out by scores on the IES-6, with the PTSD group (n=95) scoring well above the threshold of clinical concern, and those without scoring well below that threshold (n=63) (see Table 3). The PTSD group also reported poorer mental wellbeing (CORE-10) at the start of treatment, but there were no other differences.

Mean (s.d.) scores at start of treatment for PTSD and no PTSD groups on all self-reported outcomes.

| PTSD |

No PTSD |

t(df) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | s.d. | n | Mean | s.d. | |||

| BPI worst pain | 69 | 7.5 | 1.7 | 46 | 7.4 | 1.4 | 0.10(113) | 0.92 |

| BPI average pain | 70 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 45 | 6.0 | 1.3 | 0.80(113) | 0.42 |

| BPI Interference | 70 | 7.1 | 1.9 | 46 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 1.56(114) | 0.12 |

| CORE-10 | 69 | 20.8 | 7.3 | 49 | 15.6 | 7.4 | 3.86(116) | <0.001 |

| PSEQ | 70 | 21.4 | 11.1 | 47 | 23.7 | 11.7 | 1.07(115) | 0.29 |

| PCS | 70 | 28.8 | 11.2 | 49 | 25.1 | 10.8 | 1.77(117) | 0.08 |

| IES-6 | 60 | 15.8 | 5.5 | 36 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 6.68(82) | <0.001 |

-

Descriptive statistics for day 1 by PTSD Status (individuals not completing day 10 excluded).

Repeated measures ANOVA from day 1 to day 10 showed statistically significant improvements at the group level for all variables except the IES-6 (Table 4), but no interaction with PTSD group for any outcome; that is, both those with and without PTSD improved with treatment.

Scores at beginning and end of treatment for all self-reported outcomes.

| n | Day 1 |

Day 10 |

F | df | p-Value | Interaction p (time*PTSD group) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| BPI worst pain (0–10) | 115 | m7.5 | 1.6 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 15.18 | 1.113 | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| BPI average pain (0–10) | 115 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 10.38 | 1.113 | <0.001 | 0.68 |

| BPI interference (0–10) | 116 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 42.38 | 1.114 | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| CORE-10 (0–40) | 118 | 18.6 | 7.7 | 16.7 | 9.3 | 5.72 | 1.116 | 0.018 | 0.77 |

| PSEQ (0–60) | 117 | 22.3 | 11.3 | 30.4 | 13.8 | 60.93 | 1.115 | <0.001 | 0.77 |

| PCS (0–52) | 119 | 27.3 | 11.1 | 17.2 | 12.6 | 98.65 | 1.117 | <0.001 | 0.95 |

| IES-6 (0–24) | 96 | 12.9 | 7.0 | 11.4 | 7.3 | 1.69 | 1.82 | 0.198 | >0.05 |

-

Key: BPI=Brief Pain Inventory; CORE-10=Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations; PSEQ=Pain Self Efficacy Questionnaire; PCS=Pain Catastrophising Scale; IES-6=Impact of Events Scale.

Additionally, at end of treatment the PTSD group when compared to the no PTSD group had made statistically significant reductions on the CORE-10 and on the IES-6 (see Table 5). However, there was substantial missing data at day 10 in both PTSD and No PTSD groups, 31 and 23, respectively, mainly due to administrative error [12], work [11], pain flare-up [8], and post-traumatic stress symptoms [19].

Comparison between PTSD and no PTSD groups for end of treatment scores.

| Outcome | PTSD status | Mean (s.d.) | t (df) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORE-10 | PTSD | 18.7 (7.6) | t(df 116)=2.83 | 0.005 |

| No PTSD | 13.9 (10.9) | |||

| IES-6 | PTSD | 13.2 (6.9) | t(df 82)=3.59 | 0.001 |

| No PTSD | 7.5 (6.7) |

-

Key: CORE-10=Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations; IES-6=Impact of Events Scale.

-

Changes in medication use from day 1 to day 10 are shown in Table 6; 10 of the 158 veterans were not on any pain medications at day 1.

Numbers taking pain related medication at baseline and end of treatment, by class of medication.

| Medication type | Baseline n=148 |

n Stopped | n Reduced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid including compound analgesic | 132 (89%) | 33 (25%) | 22 (17%) |

| Non opioid analgesic | 104 (70%) | 31 (30 %) | 10 (10%) |

| Adjuvant (e.g. tricyclic antidepressant) | 86 (58%) | 22 (25%) | 15 (17%) |

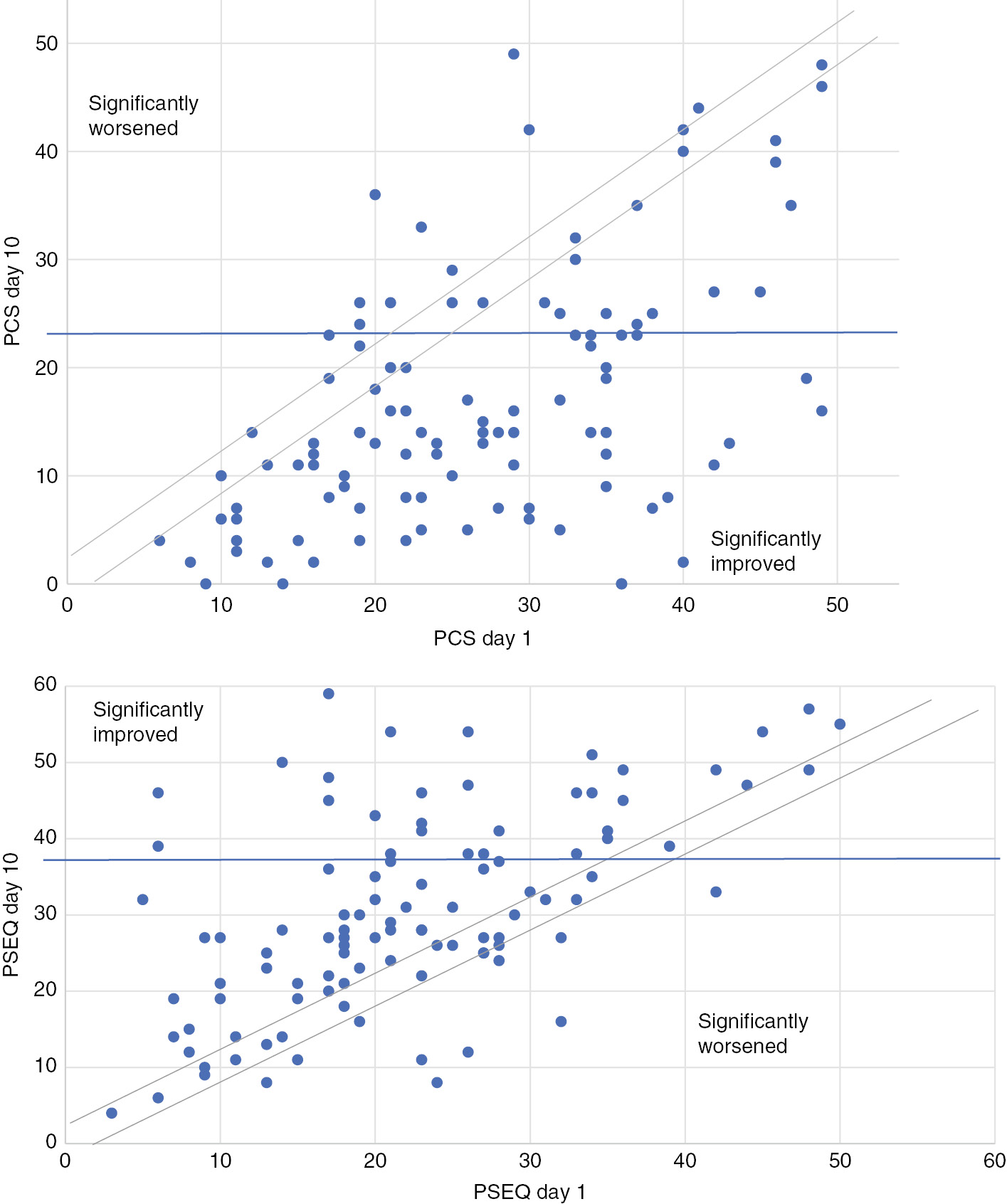

Figure 1 shows reliable changes [41] in confidence in activity despite pain (PSEQ) and pain catastrophising (PCS); those making reliable improvement far outnumbered those who reliably worsened, only a few of the latter for each outcome. The diagonal lines indicate the line of no change from pre- to post-treatment, with measurement error marked either side. Very few veterans scored worse after treatment. Also shown on both figures is a reference level from large-sample norms [41]: for the PCS it shows the proportion of the treated population who achieved or exceeded the threshold score of clinical concern (dark blue horizontal line); for the PSEQ it shows the mean score above which an population with chronic pain was more likely to be at work than not.

Clinically significant change in catastrophizing (PCS) and confidence in activity despite pain (PSEQ).

4 Discussion

Veterans with and without PTSD, treated in the PMP adapted for post-traumatic stress symptoms, made statistically and clinically significant improvements in pain, pain interference with life, and psychological health, with clear clinical improvement in post-traumatic stress symptoms and overall mental health for those scoring high at the start of the programme, in the non-clinical range at discharge. Results suggest that it is clinically appropriate to treat veterans with both conditions within the same treatment model. Comparison of the outcomes at day 10 of our veteran specific PMP with a 16-day residential UK PMP [42] with few military veteran participants shows similar improvements were achieved in both PMPs where the same scales were used. It is harder to compare findings from the UK, where armed forces are medically discharged back into the National Health System and from the USA, where military veterans are treated under multiple health insurance schemes, predominantly the Veterans’ Administration.

This study is a worthwhile addition to the scarce data on treatment of veterans presenting with high rates of chronic pain and PTSD. Although it cannot be extrapolated from the data presented, clinical experience of the treatment team puts emphasis on adapting usual PMP content and process to address veterans’ tendency to over-compensate physically to manage emotional distress, requiring flexibility in and adaptation of goal setting and paced progression towards goals. Staff members’ years of experience in pain management and team cohesion made such adaptations feasible. Additionally, veterans have a strong sense of shared identity and core values, so that engagement and group dynamics and cohesion benefited substantially from providing a veterans’ only PMP. Easier access to similar programmes would benefit the large numbers of UK military veterans with chronic pain.

There are several limitations to this study. There was no follow-up beyond the last day of the programme (albeit at 4–6 months from the start), so no evidence can be provided for maintenance of treatment gains in the longer term. Missing values were a problem for some scales, particularly the IES-6. Veterans with severe PTSD were excluded from the PMP, more because of difficulty providing sufficient psychological and psychiatric cover during treatment than because treatment was thought to be unsuitable, but it means that results cannot be extrapolated to veterans with chronic pain and any level of PTSD.

This paper supports the adaptation of pain management programmes for chronic pain to treat veterans with comorbid PTSD, as well as those without. Further research is required on whether there are measurable benefits to treating military veterans together rather than among civilian patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank King Edward VII’s Hospital which hosted the programme, organised fundraising and provided administration, The J Davy Foundation, ABF-The Soldiers Charity, Howard De Walden Trust, The Lord Majors Big Curry Lunch, Supporting Wounded Veterans, The Joron Charitable Trust, Help 4 Hero’s and HM Treasury/LIBOR for financial support. We would also like to thank the following from King Edward VII’s Hospital; Caroline Dunne (Veteran PMP Service Administrator), Tim Brawn (Director of Fundraising and Veterans’ Health), Dr Dominic Aldington (Consultant in Pain Medicine) and Jane Taylor (Coordinator, Centre for Veterans’ Health).

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee.

References

[1] Otis JD, Gregor K, Hardway C, Morrison J, Scioli E, Sanderson K. An examination of the co-morbidity between chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder on U.S. veterans. Psychol Serv 2010;7:126–35.10.1037/a0020512Search in Google Scholar

[2] Braš M, Milunović V, Boban M, Brajković L, Benković V, Đorđević V, Polašek O. Quality of life in Croatian Homeland war (1991-1995) veterans who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:56.10.1186/1477-7525-9-56Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Lew HL, Otis JD, Tun C, Kerns RD, Clark ME, Cifu DX. Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent post concussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: polytrauma clinical triad. JRRD 2009;46:697–702.10.1682/JRRD.2009.01.0006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Williamson V, Diehle J, Dunn R, Jones N, Greenberg N. The impact of military service on health and well-being. Occup Med 2019;69:64–70.10.1093/occmed/kqy139Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Goodell S, Druss BG, Reisinger Walker E: based on a research synthesis by Druss and Reisinger. Mental disorders and medical co morbidity; The Synthesis Project. The Robert Wood Johnson foundation. Policy brief No. 21. 21 February 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Buist-Bouwman MA, De Graff R, Vollebergh WAM, Ormel J. Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders and the effect on work-loss days. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006;111:436–43.10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00513.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Morgan L, Aldington D. Comorbid chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder in UK veterans: a lot of theory but not enough evidence. Br J Pain 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463719878753.10.1177/2049463719878753Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Ravn S, Hartvigsen J, Hanse M, Sterling M, Elmose T. Do post-traumatic pain and post-traumatic stress symptomatology mutually maintain each other? A systematic review of cross-lagged studies. Pain 2018;159:2159–69.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001331Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD. An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. JRRD 2003;40:397–406.10.1682/JRRD.2003.09.0397Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Asmundson G, Coons M, Taylor S, Katz J. PTSD and the experience of pain: research and clinical implications of shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance models. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47:930–7.10.1177/070674370204701004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Bosco M, Gallinati J, Clark M. Conceptualizing and treating comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Pain Res Treat 2013;2013:174728.10.1155/2013/174728Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Plagge JM, Lu MW, Lovejoy TI, Karl AI, Dobscha SK. Treatment of comorbid pain and PTSD in returning veterans: a collaborative approach utilizing behavioural activation. Pain Med 2013;14:1164–72.10.1111/pme.12155Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Otis JD. Chronic pain and PTSD. Presentation at satellite meeting, pain in military veterans: after the conflict, the battle continues. IASP World Congress. Boston, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Turk DC, Gatchel RJ, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management. 3rd ed, A practitioner’s handbook, 2018. ISBN: 9781462528530.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Faculty of Pain Medicine, Royal College of Anaesthetists. Core Standards for Pain Management Services in the UK, 2015. https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/FPM-CSPMS-UK2015.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[16] NICE guidelines NG116 Post-traumatic stress disorder. 2018 Dec. Available at nice.org.uk.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Dalton J, Thomas S, Melton H, Harden M, Eastwood A. The provision of services in the UK for UK armed forces veterans with PTSD: a rapid evidence synthesis. 2018 Feb. White rose research online. URL for this paper: http//eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133790/.10.3310/hsdr06110Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD, Monson C, Scioli E. The development of an integrated treatment for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med 2009;10:1300–11.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00715.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Kerns R, Heapy A. Advances in pain management for veterans: current status of research and future directions. JRRD 2016;53:vii–x.10.1682/JRRD.2015.10.0196Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] King’s Centre for Military Health Research, September 2018. The mental health of the UK armed forces (September 2018 version). https://www.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/publications/reports/files/Mental-Health-of-UK-Armed-Forces-Factsheet-Sept2018.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Wilson S. Veterans and chronic pain. Br J Pain 2013;7:79–84.10.1177/2049463713482082Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Diehle J, Greenberg N. Counting the costs. King’s Centre for Military Health Research. 2015 Nov, Commissioned by Help for Heroes. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/publications/reports/files/diehle2015.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Murphy D, Busuttil W. Focusing on the mental health of treatment-seeking veterans. JRAMC 2018;164:3–4.10.1136/jramc-2017-000844Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Wyldbore M, Aldington D. Trauma pain – a military perspective. Br J Pain 2013;7:74–8.10.1177/2049463713487515Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] DSM-5 – American Psychiatric Association https://www. psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm.Search in Google Scholar

[26] ICD-10 Version:2010 – World Health Organization apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Williams ACDC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3.10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther 2016;45:5–31.10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Purdie F, Morley S. Self-compassion, pain, and breaking a social contract. Pain 2015;156:2354–63.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000287Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994;23:129–38.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Tan KP, Jensen MP, Thomby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the brief pain inventory for chronic non malignant pain. J Pain 2004;5:133–7.10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Carr DB, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dionne R, Galer BS, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Kramer LD, Manning DC, Martin S, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2008;113:9–19.10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Barkham M, Bewick B, Mullinb T, Gilbodyc S, Connella J,Cahillbet J, Mellor-Clark J, Richards D, Unsworth G, Evans C. The CORE-10: a short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Counsell Psychother Res 2013;13:3–13.10.1080/14733145.2012.729069Search in Google Scholar

[34] Thoresen S, Tambs K, Hussain A, Heir T, Venke AJ,Bisson JI. Brief measure of posttraumatic stress reactions: impact of event scale-6. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:405–12.10.1007/s00127-009-0073-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale – revised. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:1489–96.10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Ruggiero KJ, Rheingold AA, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Galea S. Comparison of two widely used PTSD-screening instruments: implications for public mental health planning. J Trauma Stress 2006;19:699–707.10.1002/jts.20141Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale; development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:524-32.10.1037//1040-3590.7.4.524Search in Google Scholar

[38] Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet 2012;13:537–51.10.1038/nrg3240Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Wheeler C, Williams ACDC, Morley SJ. Meta-analysis of the psychometric properties of the pain catastrophising scale and associations with participant characteristics. Pain 2019;160:1946–53.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001494Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2012;11:153–63.10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM. What do the numbers mean? Normative data in chronic pain patients. Pain 2008;134:158–73.10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Smith JG, Knight L, Stewart A, Smith EL, McCracken LM. Clinical effectiveness of a residential pain management programme – comparing a large recent sample with previously published outcome data. Br J Pain 2016;10:46–58.10.1177/2049463715601445Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2020 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comment

- Some controversies related to questionable clinical uses of methadone for chronic non-cancer pain and in palliative care

- Systematic Reviews

- Heart rate variability in patients with low back pain: a systematic review

- Prevalence of musculoskeletal chest pain in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Clinical Pain Research

- When driving hurts: characterizing the experience and impact of driving with back pain

- Sensitization in office workers with chronic neck pain in different pain conditions and intensities

- Do chronic low back pain subgroups derived from dynamic quantitative sensory testing exhibit differing multidimensional profiles?

- Do people with acute low back pain have an attentional bias to threat-related words?

- Effects of dynamic stabilization exercises and muscle energy technique on selected biopsychosocial outcomes for patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a double-blind randomized controlled trial

- Health-related quality of life and pain interference in two patient cohorts with neuropathic pain: breast cancer survivors and HIV patients

- Breast reconstruction after breast cancer surgery – persistent pain and quality of life 1–8 years after breast reconstruction

- Autonomic dysregulation and impairments in the recognition of facial emotional expressions in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Sleep disturbance in patients attending specialized chronic pain clinics in Denmark: a longitudinal study examining the relationship between sleep and pain outcomes

- The challenge of recognizing severe pain and autonomic abnormalities for early diagnosis of CRPS

- Military veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder: results from a chronic pain management programme

- Observational Studies

- Long-term postoperative opioid prescription after cholecystectomy or gastric by-pass surgery: a retrospective observational study

- Criterion validity and discriminatory ability of the central sensitization inventory short form in individuals with inflammatory bowel diseases

- Neural activity during cognitive reappraisal in chronic low back pain: a preliminary study

- Social deprivation and paediatric chronic pain referrals in Ireland: a cross-sectional study

- Original Experimental

- The inhibitory effect of conditioned pain modulation on temporal summation in low-back pain patients

- “Big girls don’t cry”: the effect of the experimenter’s sex and pain catastrophising on pain

- Short Communication

- Persistent pain relief following a single injection of a local anesthetic for neuropathic abdominal wall and groin pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comment

- Some controversies related to questionable clinical uses of methadone for chronic non-cancer pain and in palliative care

- Systematic Reviews

- Heart rate variability in patients with low back pain: a systematic review

- Prevalence of musculoskeletal chest pain in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Clinical Pain Research

- When driving hurts: characterizing the experience and impact of driving with back pain

- Sensitization in office workers with chronic neck pain in different pain conditions and intensities

- Do chronic low back pain subgroups derived from dynamic quantitative sensory testing exhibit differing multidimensional profiles?

- Do people with acute low back pain have an attentional bias to threat-related words?

- Effects of dynamic stabilization exercises and muscle energy technique on selected biopsychosocial outcomes for patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a double-blind randomized controlled trial

- Health-related quality of life and pain interference in two patient cohorts with neuropathic pain: breast cancer survivors and HIV patients

- Breast reconstruction after breast cancer surgery – persistent pain and quality of life 1–8 years after breast reconstruction

- Autonomic dysregulation and impairments in the recognition of facial emotional expressions in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Sleep disturbance in patients attending specialized chronic pain clinics in Denmark: a longitudinal study examining the relationship between sleep and pain outcomes

- The challenge of recognizing severe pain and autonomic abnormalities for early diagnosis of CRPS

- Military veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder: results from a chronic pain management programme

- Observational Studies

- Long-term postoperative opioid prescription after cholecystectomy or gastric by-pass surgery: a retrospective observational study

- Criterion validity and discriminatory ability of the central sensitization inventory short form in individuals with inflammatory bowel diseases

- Neural activity during cognitive reappraisal in chronic low back pain: a preliminary study

- Social deprivation and paediatric chronic pain referrals in Ireland: a cross-sectional study

- Original Experimental

- The inhibitory effect of conditioned pain modulation on temporal summation in low-back pain patients

- “Big girls don’t cry”: the effect of the experimenter’s sex and pain catastrophising on pain

- Short Communication

- Persistent pain relief following a single injection of a local anesthetic for neuropathic abdominal wall and groin pain