Abstract

Background and aims

A targeted pain program may prevent the progression and subsequent occurrence of chronic pain in adolescents. This study tested the effectiveness of a new acceptance and commitment therapy -based pain management intervention, using physical and psychological functions as the outcomes. The objective was also to determine whether Pediatric Pain Screening Tool risk profiles function as outcome moderator in the current sample. A valid screening tool would enable the program development.

Methods

Thirty-two consecutive adolescent patients (13–17 years old) with idiopathic recurrent musculoskeletal pain completed the study. The intervention comprised acceptance and commitment therapy-oriented multidisciplinary treatment. Pediatric Pain Screening Tool, pain frequency, functional disability, school attendance, physical endurance, depressive symptoms, and catastrophizing coping style were measured before treatment (baseline) and again at 6 and 12 months after the initiation of treatment. To test the effectiveness of the new program, we also determined whether the original risk classification of each patient remained constant during the intervention.

Results

The intervention was effective for high-risk patients. In particular, the pain frequency decreased, and psychosocial measures improved. In post-intervention, the original risk classification of seven patients in the high-risk category changed to medium-risk. PPST classification acted as a moderator of the outcome of the current program.

Conclusions

The categorization highlighted the need to modify the program content for the medium-risk patients. The categorization is a good tool to screen adolescent patients with pain.

Implications

The results support using the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool in developing rehabilitation program for pediatric musculoskeletal pain patients. According to the result, for adolescent prolonged musculoskeletal pain patients the use of ACT-based intervention program is warranted.

1 Introduction

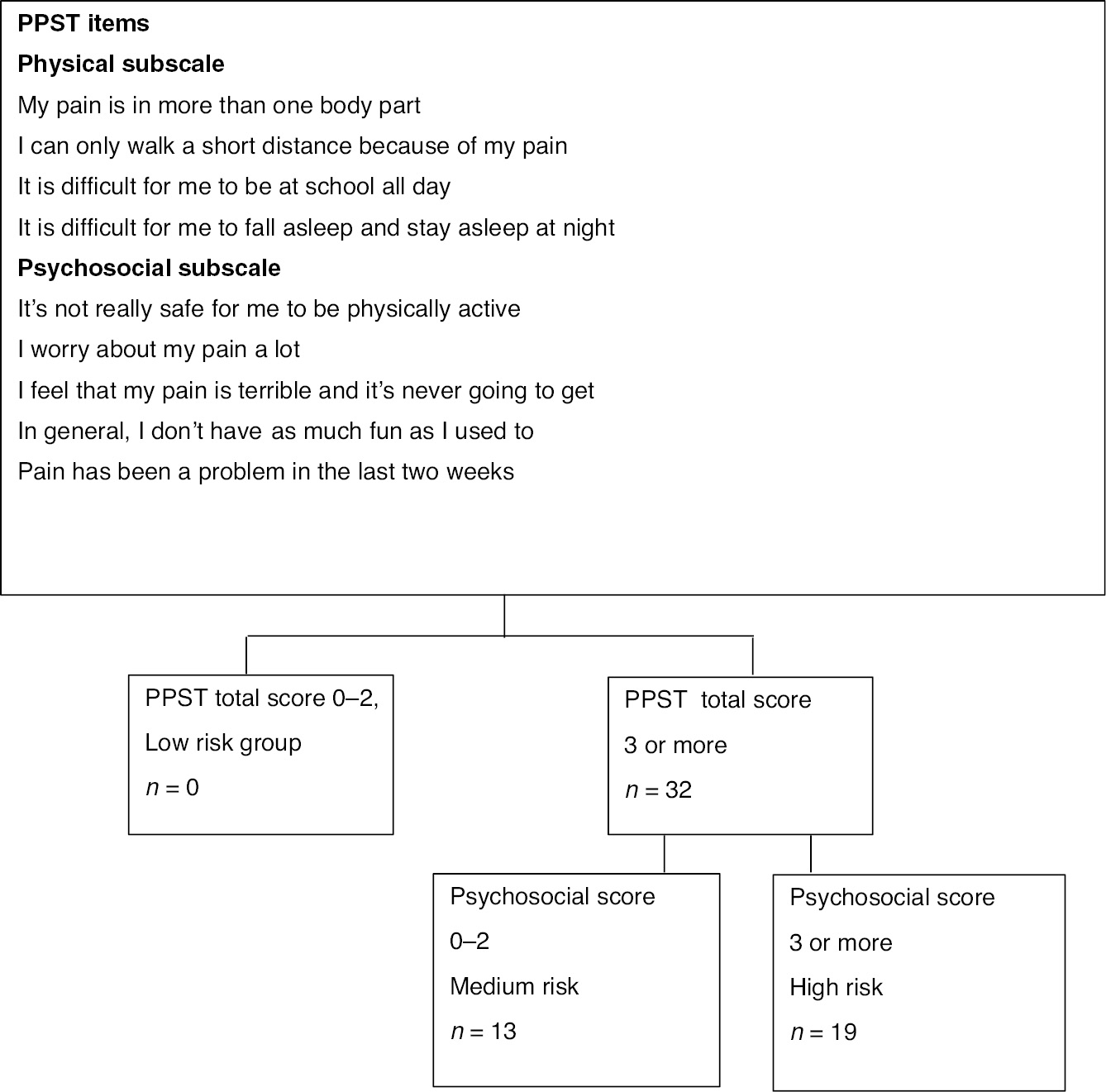

Adolescents with prolonged musculoskeletal pain may develop pain-associated disabilities and have decreased school attendance and poor social involvement [1], [2], [3], [4]. Therefore, early intervention is necessary for these pain patients. When targeting treatment for these patients in general, it seems that the rational is to increase effective response to pain [5]. These responses may include participation in activities with pain and engagement in activities that bring meaning, vitality, and value to life [5]. However, this patient group is not uniform in regard to the frequency of pain experienced, pain coping skills used, or level of physical functioning. Therefore, it is important to recognize the modifying factors that might have an effect on the treatment benefit. Morley et al. [6] have argued that levels of distress or disability should be distinctly specified in the entry criteria for clinical trials to target patient treatment. Therefore, in the present study the recently published Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) [7] was used to empirically classify patients based on physical and psychosocial subscales (Fig. 1). In this study, the PPST-categorization was performed retrospectively to ensure the feasibility of the categorization system for future use.

Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) scoring and group allocation in the sample.

Coping refers to purposeful cognitive and behavioral efforts to overrule the negative impact of stress [8]. In prolonged adolescent pain, coping can be active and adaptive [9], as the patient finds ways to accept the symptoms while participating in meaningful activities [5]. In passive and maladaptive coping, the focus shifts more to the pain itself, and the patient may experience rumination, helplessness, and fear of pain [10], [11], [12]. It is therefore important to recognize maladaptive coping skills in adolescents with prolonged pain and to target treatment as necessary. Improvement in pain acceptance may be associated with functional activity [13], whereas catastrophizing and worrying have adverse effects [14], [15], [16], [17], [18].

In clinical practice, it is important to find ways to enhance patients’ flexibility, and acceptance [11], [13], [19] in connection with prolonged pain. However, Cochrane studies [20], [21] report conflicting results on the efficacy of behavioral therapies for pain management. The interventions effectively reduce pain intensity and alleviate anxiety in some pain states after treatment but maintaining the results of pain alleviation and mood outcomes is challenging. Eccleston et al. [20] suggested using functional outcomes, such as the return to normal schooling, to measure the efficacy of treatment. Recently Palermo et al. [22] found that pain and function change together during treatment, meaning that function may improve before pain subsides. Therefore, when developing a new intervention, increased patient activity is a logical goal that should be implemented at the beginning of treatment [23]. Typically, a multidisciplinary team works in collaboration on shared treatment goals to achieve functional restoration and psychological and physical improvement in the activities of the patient and their family [24], [25]. Physical therapy and working with pain as a bodily sensation may be included in the treatment as crucial components. There is an increasing number of randomized controlled trials in the field of pediatric chronic pain [21], [24], [25]], [26]. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has been incorporated into treatment protocols [11], [13], [27], [28]. In ACT, improvement of functionality with pain is usually the working goal. According to Pielech et al. [5] the primary focus of ACT is to facilitate valued-based action and increase a repertoire of responses to pain and associated cognitions and sensations; there is also a focus to develop flexible use of these strategies. Additionally, parental functionality and flexibility are important treatment targets given that parents can help their children with active pain management, e.g. promote school attendance [29], [30], [31], [32].

The primary objective of this study was to test the utility of the current ACT-based pain management intervention pain management intervention (PMI) for further development of this program. This small study was conducted to determine if the current intervention is effective, and if so, to determine which patients with varying risks status can be treated successfully using this method. To answer these questions, we examined whether the Pediatric pain screening tool (PPST)-based risk profiles functioned as outcome moderators. To test the utility of the new program, we also investigated whether the original classification of patients (as high- or medium-risk) changed during the intervention.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Treatment setting

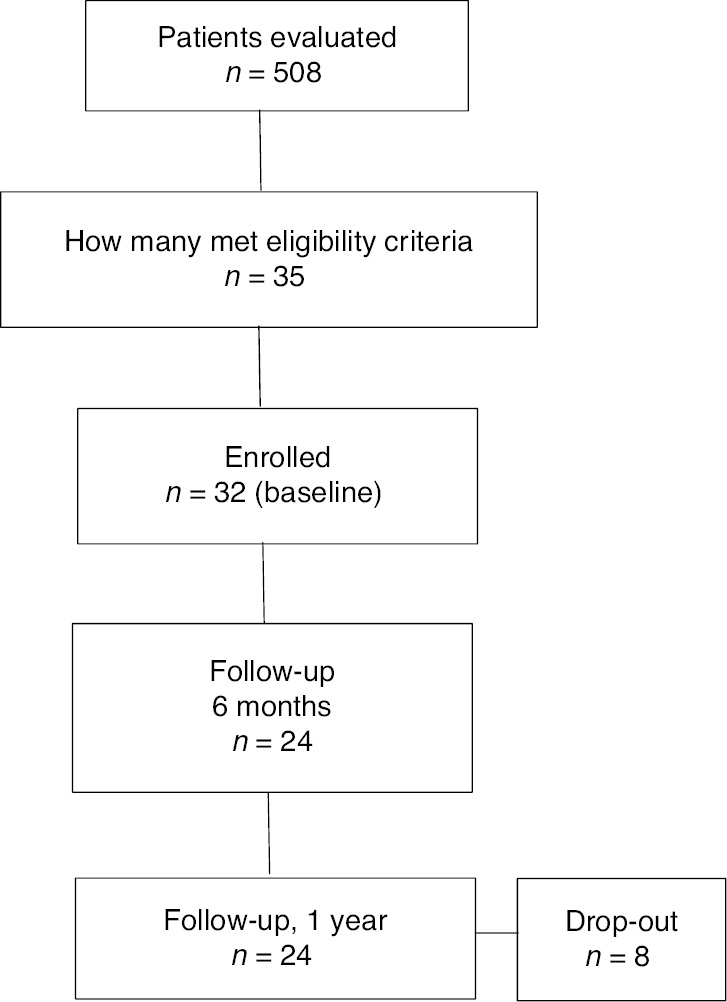

In the current feasibility study, a pain management intervention (PMI) program was developed for use in a pediatric rheumatological clinic. The clinic’s territory included 36,000 children <16 years of age. From 2010 to 2015, the pediatric rheumatology outpatient clinic evaluated 508 patients (Fig. 2). Of these patients, 35 met the eligibility criteria. Thirty-two of those patients enrolled in the study. In a 1-year follow-up, there were 24 patients.

Flow diagram of the study.

The inclusion criteria included: referral to the central hospital due to musculoskeletal pain, age between 13 and 17 years, persistent pain over 3 months, pain not explained by chronic illnesses, and substantial pain-related disability including poor school attendance and sleep. Patients diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), connective systemic rheumatic diseases, or other diseases that cause prolonged pain, were excluded from the PMI program. After entering the tertiary care hospital, the patients were recruited to the PMI program without delay to mitigate pain-associated problems and additional pain-related healthcare referrals. Study data were collected before treatment (baseline, t1) and at 6 (t2) and 12 months (t3) after the initiation of treatment. The treatment modules 1 and 2 took place one and 2 months after baseline assessment (Table 1).

Outline of the treatment approach.

| Baseline assessment | Module 1 3 days | Home assignments 1 | Module 2 3 days | 6 Months follow-up | Home assignments 2 | 1 Year follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | x | X | x | ||||

| Main content of the treatment | |||||||

| Value based action | x | xxx | xxx | xxx | xx | ||

| Distinguishing pain associated cognitions and sensations | xxx | x | xx | x | |||

| Flexible use of response to pain cognitions and sensations | x | x | xxx | x | |||

| Psychoeducation | x | xxx | xx | ||||

| Physical exercises | xx | xx | xx | xx | xx | ||

| Mindfulness exercises | x | x | xx | x | |||

| Muscle relaxation | xxx | x | x | ||||

| Time spent | |||||||

| Patients | 6 | 18 | 18 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Accompanying parent | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | ||

-

x=intensity of the content included in the module.

2.2 Participant recruitment

Thirty-two consecutive patients with musculoskeletal pain were recruited for the current study during routine clinical visits over a 2-year period from an area covering the Päijät-Häme region. All patients were Caucasian. Persistent pain over a 3-month period was the primary complaint. The patients and their accompanying parents were invited to participate in the next group-format outpatient pain program; one patient declined. At the Department of Pediatrics described in this study, adolescents participated in a group outpatient program for pain rehabilitation that comprised nine intensive days of pain management. All patients underwent tests for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complete blood count, levels of C-reactive protein, creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, citrullinated peptide antibodies, anti-tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies, IgA (to exclude deficiency), human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class 1 molecule B27 (HLA-B27), Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (to exclude Crohn’s disease), and Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies. Patients with chronic illnesses were excluded from the study based on test results. To exclude chronic arthritis and other illnesses and to confirm idiopathic musculoskeletal pain with no other cause, 27 of the 32 patients were examined using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). One of the patients had Marfan syndrome and four had Ehler-Danlos syndrome; all of these diagnoses were confirmed by a physician who specialized in genetics. The patients and the parents were interviewed before the study onset by the multidisciplinary team, which comprised a psychologist, physiotherapist, pediatric rheumatologist, and nurse. The outline of the PMI program was introduced in the interviews, and the patients and parents were given the opportunity to join the next group treatment initiation session.

2.3 Treatment intervention

The purpose of the program, entitled pain management intervention (PMI), was to improve active functioning and engagement in life regardless of pain level. The treatment was based on and modified from protocols using ACT frameworks [5], [19]. The patients’ life activities, such as school attendance, involvement in hobbies, and social life, were supported (Table 1). Concrete plans were made to enhance everyday healthy activities such as sleeping, eating, social relations, and initiation of physical activity and recovery. Each patient was provided with an individual working plan and home assignments to improve active life. The team, comprising the patient, the parent, a physical therapist, a psychologist, a nurse, and a pediatric rheumatologist, tailored an individual plan for each patient that involved increasingly challenging goals. In the group sessions, physical exercises were performed alternately with mindfulness exercises, ACT-based exercises, and muscle relaxation. The primary objective of the program was to improve the adolescent’s ability to cope and function with the pain, to promote independence from medical care, and to support the patient’s return to a normal level of adolescent activity. It was expected that improvement in pain management skills (e.g. improved flexibility in managing pain associated thoughts), would reduce the pain frequency at follow-up visits. The treatment comprised 10 days of sessions at the outpatient clinic (Table 1). The parents participated in each of the modules of the program. The adolescents and parents were also given home assignments. The adolescents, and the parental groups worked in groups of 5–6 persons.

The PMI started with an information day, which was designed to achieve a sound mutual understanding of the adolescent’s health status, with a special emphasis on normalization. During this day, the adolescent and accompanying parent were given basic information about pain chronification and how it may affect of daily living. The patients were encouraged to increase their activity and exercise. The PMI sessions comprised ACT-related content (Table 1) that addressed topics such as a meaningful and valued life, distinguishing thoughts, and sensations and their effect on actions. The content of the group-treatment was as uniform as possible, and it addressed the issues outlined in Table 1. As the treatment took place in a group-format, timing of the practices and actual realization varied to some extent between the groups; this depended on, for example, the current activity level of each of the patients.

The team members worked in pairs with the adolescents, and all aspects of the sessions were covered from both psychological and physical perspectives. This work was ACT-driven, meaning that the working pair had an equal theoretical understanding regarding the program realization, which was to help the adolescents develop valued-based actions. The mind-body aspect was used to identify stress and promote stress reduction during the sessions. Education on the physiology of recurrent pain and exercise, the potential effects of inactivity, benefits of exercise, pacing, nutrition, relaxation skills, and sleeping was also provided. The parent sessions focused on increasing the pain-related problem-solving skills in living with a child with persistent pain and managing health-related anxiety. The parents were given the home assignment of supporting the adolescent in active and flexible coping strategies for pain. The home assignments were followed-up by the team during the sessions.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Physical function

2.4.1.1 School absence

Each parent was asked to record the number of school days during the previous 6 months that the adolescent had missed school due to pain. The answers were rated from 1 to 5, (1, none; 2, 1–5 days; 3, 6–15 days; 4, 16–25 days; and 5, ≥25 days absent).

2.4.1.2 Six-minute walking test (6MWT)

A six-minute walking test [33], [34] was used to evaluate the endurance of each patient. The test measured the distance the patient was able to walk quickly on a flat, hard surface. The walking test has been found to have a moderate correlation with maximum oxygen consumption.

2.4.1.3 Pain frequency score

Pain was measured using a structured pain questionnaire [35]. The rationale for evaluating pain frequency was to measure pain over a period in children with persistent pain rather than at a particular point of time. The questionnaire used a five-level system to classify the frequency of pain during the previous 3 months (seldom or never, once per month, once per week, more than once per week, almost daily). Each of the six pain areas (neck, upper and lower extremities, chest, upper back, lower back) was scored from 0 to 5; the total (frequency and area combined) score ranged from 0 to 24. The body area in question was marked on a picture beside the question to help the patient recognize it. The pain frequency score has previously been validated for use in children [35], [36].

2.4.1.4 Functional disability

The Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire CHAQ [37], [38] was used to measure each patient’s functional status. It included general and pain-related visual analog scale (VAS) ratings and assessed performance in eight areas (dressing and grooming, rising, eating, walking, hygiene, reaching, gripping, and other activities). It provided an overall disability score of 0–3; a higher score indicated greater functional impairment. The CHAQ has been reported to be reliable and sensitive, and was validated in a sample of Finnish patients.

2.4.2 Psychological function

2.4.2.1 Child Depression Inventory (CDI)

The Finnish version of the Child Depression Inventory [39] was used to measure the depression/mood disturbances of each patient. The Finnish version included 26 of the 27 items in the English version; the question about suicide was excluded for ethical reasons. Each item was scored from 0 to 2, with the total score ranging from 0 to 52. Higher values indicated increasingly severe depression. A score of 13 was the cut-off point for identifying clinical depression.

2.4.2.2 Catastrophizing style of pain coping (CAT)

The Pain Coping Questionnaire (PCQ) was used to measure if a catastrophizing style of coping with pain was utilized [10], [40]. The questionnaire included 39 items indicating how often the patient used a certain coping strategy when in pain. In the instructions on the form, the subjects were advised to report how they acted when in pain for hours or days, and to rate the frequency (1, never; 2, hardly ever; 3, sometimes; 4, often; 5, very often). The PCQ is independent of the cause of pain and can be administered to children as young as 8 years of age. The original PCQ included eight subscales (information seeking, problem solving, seeking social support, positive self-statements, behavioral distraction, cognitive distraction, externalizing, and internalizing/catastrophizing). The internalizing/catastrophizing subscale included the following six items: “I worry that I will always be in pain;” “I think that the pain will never stop;” “I think that nothing helps;” “I worry too much about it;” “I keep thinking about how much it hurts;” and “I figure out what I can do about it.” The total score of internalizing/catastrophizing can range from 6 to 30. In the current study, a catastrophizing coping style was measured independently from other coping subscales because it has been suggested to be a distinct form of coping [10].

The PPST [7] was used as a potential moderator of outcome. The patients completed the PPST, which consisted of nine items and two subscales: physical and psychosocial. The physical subscale included four items and the psychosocial subscale included five items (Fig. 1). Each item is scored as 0 or 1; the total maximum score for the tool is 9. According to Simons et al. [7] patients with total score 0–2 are low risk patients and patients with a total score of ≥3 are at medium- or high-risk. Of these, patients that scored 0–2 in the psychosocial subscale were medium-risk-patients and ≥3 in the psychosocial subscale were classified as high-risk patients. Pain frequency and the 6MWT of the medium- and high-risk groups were measured at baseline (t1) and again at 6-month (t2) and 12-month (t3) follow-up visits.

2.5 Statistical methods

To find out if the PPST risk profiles function as outcome moderators in the current sample the following was done: the statistical significance of the unadjusted hypothesis of linearity across the PPST categories and the descriptive baseline data were evaluated using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend and an analysis of variance with an appropriate contrast (orthogonal polynomial), respectively. To analyze if the treatment was effective, repeated measures were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) models with an appropriate distribution and link function. Generalized estimating equations were developed as an extension of the general linear models [such as ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis] to analyze longitudinal and other correlated data. GEE models consider the correlation between repeated measurements of the same subject; the models do not require complete data and can be fitted even when observations are not available for all time points. For cases where there is violation of the assumptions (such as non-normality), a bootstrap-type method was used (10,000 replications) to estimate the standard error. The normality of the variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. All analyses were performed using STATA 14.1. (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA)

3 Results

3.1 Baseline assessment

Table 2 shows the descriptive data of the patients. Most patients were girls (81%). In the beginning of the pain management intervention, the mean age of the patients was 14.4±1.3 years. The time from pain onset ranged from 15 to 72 months (mean, 24 months). The primary pain locations in the six musculoskeletal pain areas were the lower extremities (87%), neck and shoulders (78%), and lower back (69%). Patients suffered from pain in multiple locations: three or more painful body areas were reported by 78% of patients. The patients as a group had a comparable degree of depressive symptoms to healthy Finnish adolescents [41]. The amount of pain catastrophizing was measured at baseline as a sign of a vulnerable pain coping style; the mean was 15.1±5.5. At baseline, 19% of the study patients had not been absent from school due to pain during the previous 6 months; 40% had been absent for >25 days due to pain. Functional disability score was M=0.25±0.33. This was comparable to a larger sample of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [36]. The results indicated the patients’ poor psychological, physical, and social functioning status at baseline.

Descriptive data of the baseline variables.

| Allbaseline |

PPST baseline |

p-Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=32 | PPST psychosocial score 0–2 n=13 |

PPST psychosocial score 3 or more n=19 |

||

| Girls, n (%) | 26 (81) | 10 (77) | 16 (84) | 0.67 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 14.4 (1.3) | 14.2 (1.1) | 14.6 (1.3) | 0.30 |

| Duration of pain, mth, median (IQR) | 24 (15, 72) | 24 (18, 36) | 24 (15, 72) | 0.32 |

| CHAQ, mean (SD) | 0.25 (0.33) | 0.09 (0.21) | 0.37 (0.36) | 0.017 |

| Structured pain questionnaire; pain frequency score, mean (SD) | 12.5 (6.1) | 7.5 (4.0) | 15.9 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal pain, n (%) | ||||

| Neck or shoulder | 25 (78) | 8 (62) | 17 (89) | 0.091 |

| Upper ex | 20 (62) | 5 (38) | 15 (79) | 0.030 |

| Chest | 10 (31) | 2 (15) | 8 (42) | 0.14 |

| Upper back | 18 (56) | 4 (31) | 14 (74) | 0.029 |

| Low back | 22 (69) | 7 (54) | 15 (79) | 0.24 |

| Lower ext | 28 (87) | 9 (69) | 19 (100) | 0.020 |

| Three or more locations | 25 (78) | 8 (62) | 17 (89) | 0.091 |

| 6MWT, mean (SD) | 577 (58) | 575 (58) | 578 (59) | 0.93 |

| CDI, mean (SD) | 10.2 (8.5) | 6.9 (7.3) | 12.5 (8.8) | 0.039 |

| CDI 13-, n (%) | 9 (28) | 1 (8) | 8 (42) | 0.033 |

| Catastrophizing (CAT) | 15.1 (5.5) | 10.8 (3.4) | 18.1 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| School absence days due to pain, previous 6 months, n (%) | 0.17 | |||

| None | 6 (19) | 5 (38) | 1 (5) | |

| 1–5 | 4 (12) | 1 (8) | 3 (16) | |

| 6–15 | 7 (22) | 2 (15) | 5 (26) | |

| 16–25 | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | |

| >25 | 13 (40) | 5 (38) | 8 (42) | |

According to the PPST scale, patients had pain in several body parts, and pain had been a problem for all of them in the last 2 weeks (Fig. 1). Almost all patients in the study (n=29) felt a loss of fun in their life, and many (n=25) had difficulties going to school. One in three patients was not able to walk even a short distance (1 km) due to pain. The patients also worried about pain (n=24) and felt that physical activity was not safe for them (n=25). As a group, their functional activity was lowered. All patients in the current study had a PPST total score of ≥3, meaning that there were no low-risk patients in this study. Nineteen patients were classified as high-risk (total PPST score ≥3; psychosocial subscale score ≥3), and 13 were classified as medium-risk (total PPST score ≥3; psychosocial subscale score 0–2). In the medium-risk group, the baseline values of depressive symptoms were not clinically significant, but in the high-risk group there were elevated emotional symptoms. The medium-risk group had pain symptoms in fewer pain areas of the body than did the high-risk group, and they were functioning relatively well in terms of school attendance. There were baseline differences between the medium- and high-risk groups in functional disability (p=0.017), pain frequency (p<0.001), depressive symptoms (p=0.039), and catastrophizing coping style (p<0.001) (Table 2).

3.2 Follow-up assessment

The patients were assessed at baseline (t1) and again at 6-month (t2) and 12-month (t3) follow-up visits. All the patients were in medium- and high-risk groups.

3.3 Physical functioning at t1, t2, and t3

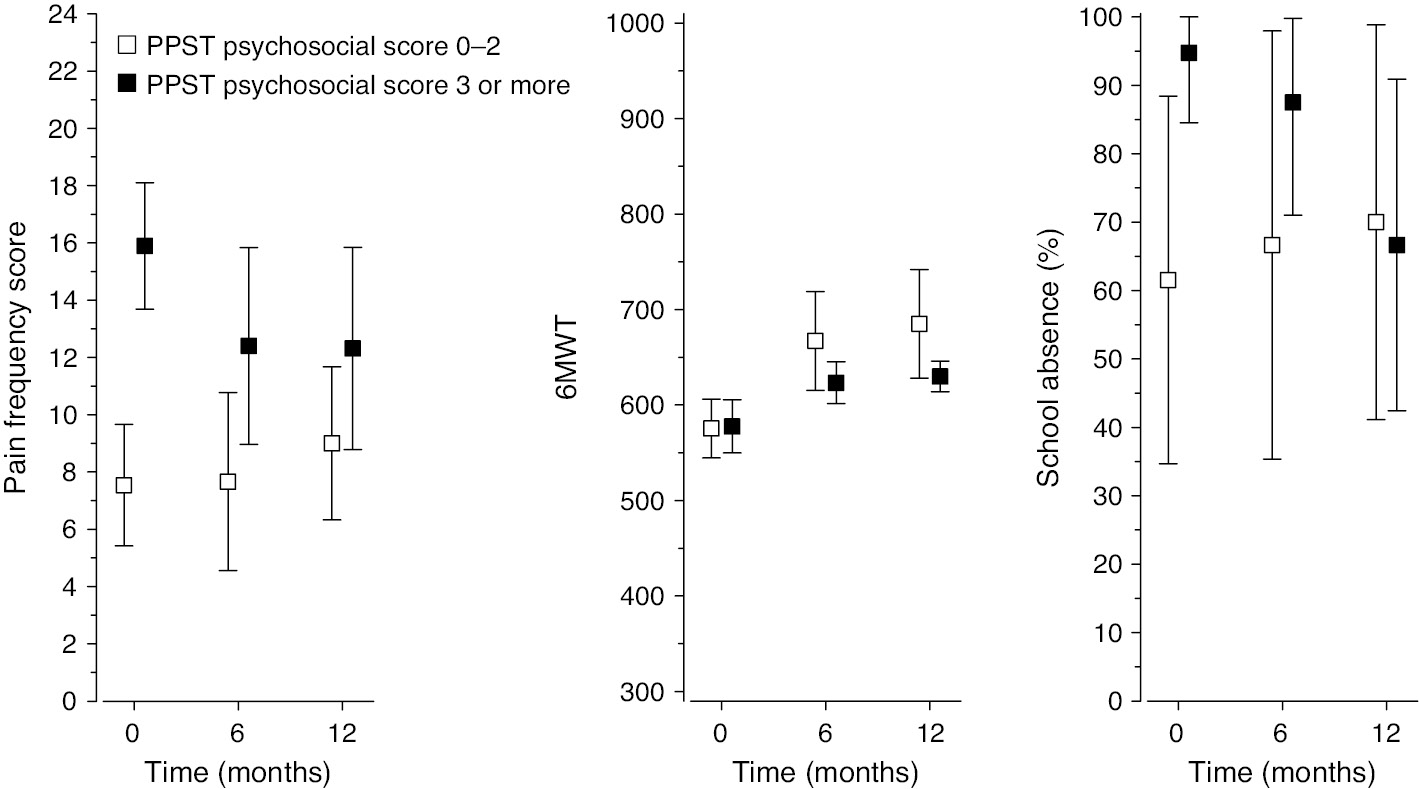

Pain frequency and the 6MWT in the medium- and high-risk groups were measured as factors of physical function (Fig. 3). There was a significant time-group interaction in pain frequency between the medium- and high-risk groups, as measured using a structured pain questionnaire (p=0.019). The high-risk group improved by 25% (p=0.005) from (15.9±2.0) to (12.2±7.4), whereas there was no change in the medium-risk group for the same period. The reduction tendency in the high-risk group could be seen at t2, after the patients had gone through the modules of intervention.

Follow-up data according to pain frequency, the six-minute walking test, and school absences. The patients were categorized as high-risk or medium-risk according to the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) criteria.

The time-group interaction for the walking test (6MWT) between the medium- and high-risk groups was not significant (p=0.091) (Fig. 3). Both the medium- and the high-risk groups improved from t1 to t3 (p<0.001). At t1, the walking test results were the same in both groups; the patients in both groups were able to walk approximately 580 m in 6 min. The walking test results in the medium- and the high-risk groups improved by 14% and 7%, respectively.

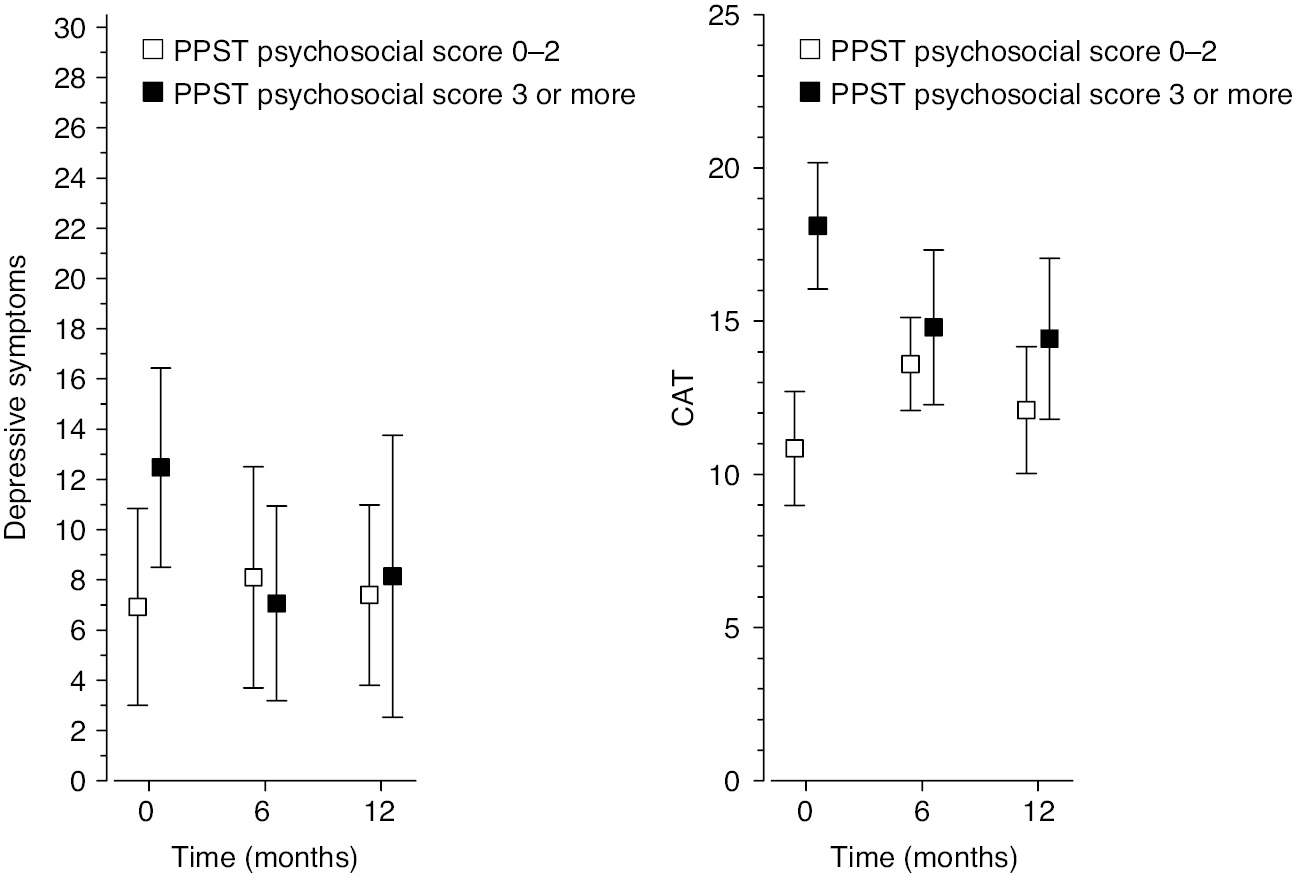

3.4 Psychosocial functioning at t1, t2, and t3

Depressive symptoms, school attendance, and pain catastrophizing were measured in all patients as factors of psychosocial function. There was a significant time-group interaction in depressive symptoms between the medium- and high-risk groups (p=0.020) (Fig. 4). In the high-risk group, the depressive symptoms decreased by 36% (p=0.0046) from (12.5±8.8) to (8.0±11.35). In the medium-risk group, there was no significant change in depressive symptoms from (6.9±7.3) to (7.1±7.1). The time-group interaction for pain catastrophizing was significant between the medium- and high-risk groups (p<0.001), showing that the high-risk group improved compared with the medium-risk group (Fig. 3). In the high-risk group, pain catastrophizing (CAT) decreased by 19% (p=0.008) from (18.1±3.4) to (14.2±5.2); there was no change in the medium-risk group for the same period.

Follow-up data according to the psychological variables of depression and the catastrophizing coping style. The patients were categorized as high-risk or medium-risk according to the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) criteria.

Of the patients in the high-risk group, 95% had been absent from school during the past 6 months due to pain at baseline (Fig. 4). The corresponding number in the medium-risk group was 62%. The difference in school attendance between the groups was not significant (p=0.13). School attendance in the high-risk group improved slightly (p=0.039). In the medium-risk group, school attendance worsened during the same interval, but the change was not significant.

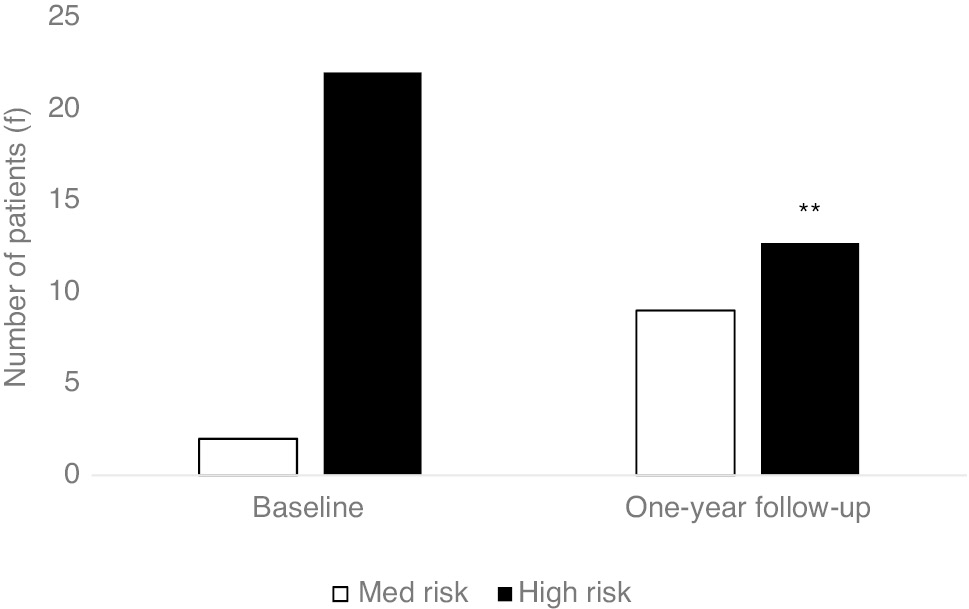

3.5 Stability of group allocation during the intervention

At the 1-year follow-up there were 24 patients. When the classification was repeated at the follow-up, seven patients (37.5%, p=0.008) were re-classified from the high risk into the medium risk group: the risk profile of these patients changed during the intervention (Fig. 5). None of patients in the original medium-risk group was re-allocated to the high-risk group. Eight patients dropped out from the baseline to 1-year follow-up. Of these the original grouping of the patient was medium risk-group (n=2) and high risk-group (n=6).

Risk classification of the patients (f) at the baseline and in the 1-year follow-up. **p<0.01, change from high risk into medium risk group.

4 Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the PPST [7] classification acted as a moderator of the outcome of the current program. The intervention was effective for high-risk patients. Specifically, the pain frequency decreased, and psychosocial measures improved. In the medium-risk group, the psychosocial variables remained fairly constant and the functional and psychological measures did not improve as much. When the empirical categorization was repeated after the intervention, 37.5% of the high-risk patients were reclassified as medium-risk. These patients had benefitted from the PMI program, and the progression of their pain condition changed. Thus, further development of the ACT-based multidisciplinary program is warranted.

The most probable reason for the lack of change in the medium-risk group was that these patients were managing relatively well at baseline; while the group values in psychological functioning were not clinically significant, one cannot expect changes in post-intervention in terms of these factors. The problem with the treatment effect is well established in a study by Palermo et al. [22].

According to the findings in this study, the ACT-based content of the treatment (e.g. facilitation of valued-based action and improving functionality and flexibility in pain management) successfully captured the challenges that are faced in the high-risk group. As the content of PMI was ACT-based, including the PPST psychosocial subscale that differentiates between medium- and high-risk, it is logical that those with greater impairment had greater response to treatment.

Despite the small sample size, only 32 patients, the categorization provided a clinically significant result; we found that patients with different risk profiles require different pain interventions, and the PPST may serve as a treatment optimizing tool. Future options might include the formation of separate PMI groups for patients with different risk profiles, and prospective modification of the content within a group of patients with different risk classifications. The group format itself has advantages compared to individual therapy; the sense of peer-to-peer collaboration during pain-related challenges is the most important. However, Kanstrup et al. [1] recently compared ACT-based individual and group treatment in a pediatric pain sample comparable to ours; both treatment formats significantly improved adolescent functioning and parental flexibility, but the there was no significant difference in the results between the formats. For the current rehabilitation protocol, the results of Kanstrup et al. [1] suggest the use of an individually delivered format, specifically for the PPST-medium risk patients and their parents, as the next developmental step of the program. In an individual format, the baseline strengths of the patients (e.g. more flexible pain coping skills and less mood disturbance) could be better considered in the flow of the treatment, such as in the facilitation of valued-oriented behavior. The medium-risk group adolescents should receive attention in treatment planning, because pain in childhood may predict pain-related disability later in life.

The current study showed that the patients in the sample had suffered from pain symptoms for approximately 2 years before admission to the PMI program, and there was no difference between the groups in pain duration. To prevent an adverse prognosis, earlier implementation along with an efficient screening tool [7] may improve the intervention results in general. Another important aspect beside pain duration is pain interference. Wicksell et al. [13] recently showed that the pediatric patients displaying the greatest functional impairment were not the patients with the longest pain duration nor those with the highest level of pain. Interestingly, pain interference mediated the relationship between pain and depression. Wicksell et al. [13] result suggests the use of the PPST as a risk assessment tool, as the scale comprises items referable to pain interference and impact of pain, such as of school attendance, walking, sleep, and mood.

The baseline measurements of patients in the current study indicated moderate depressive symptoms, the use a catastrophizing coping style, and poor endurance. The level of depressive symptoms was not alarmingly high in the patients in the study. Of Finnish schoolchildren, 22% have been determined to have some depressive symptoms, and 3% to have severe depression. In a Finnish epidemiological study [42], roughly 30% of schoolchildren 11 years of age and with widespread pain, had clinical depression [41]. In the current sample, a corresponding number of patients (28%), had clinical depression. Of the patients in this study, 40% had been absent from school for over 25 days during the previous 6 months due to pain. Moreover, almost all high-risk patients had severely decreased school attendance. These characteristics could be anticipated based on previous studies [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [7], [9], [10], [11], [13].

A number of limitations should be considered, when interpreting the results of this preliminary clinical study. First, to our knowledge, PPST has not previously been validated as a tool that is sensitive to detecting significant changes over time. Second, the small sample size limited the power to evaluate the effect of the program. Attrition of the sample was high considering the statistical analysis. However, as the result of this preliminary study shows, further data collection and research is warranted as the risk assessment tool functioned as a moderator. There was no control group, thus it cannot be fully concluded that treatment caused the progress observed. Additionally, because of the small sample size, this study does not allow causality conclusions regarding the baseline factors vs change relations. The re-classification result that occurred after treatment was introduced as a promising, yet preliminary finding. Extrapolating this result was done cautiously. Moreover, the missing data from the follow-ups challenged the interpretation of the findings. A larger amount data is expected to provide more reliable and detailed information about what specific characteristics explain the reclassification. As the program was ACT-oriented, possible variables in future studies may include valued-based and flexible function, improvement in functional disability, and pain interference. The current study does not include measures of ACT specific variables (e.g. pain acceptance, cognitive flexibility), which likely may be most reliable for capturing treatment changes.

The study sample was comparable to many clinical studies in the field of pediatric pain [1], [7], [11], [13], [27]. In this respect, the results can be generalized to hospital settings. In the future, with the availability of a valid tool, the ideal goal is to administer the PPST prospectively. Only prospective group allocation could facilitate better targeted and more effective treatment, as Morley et al. [6] have suggested.

In conclusion, the PPST moderated the effectiveness of the current ACT-based treatment in adolescents with idiopathic recurrent musculoskeletal pain. In the future, the use of PPST categorization can help screening the pediatric musculoskeletal pain patients in hospital settings. It may also enhance the effectiveness of the treatment. In the current study, the categorization system highlighted the need to adjust the program content for the medium-risk patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Pediatrics at Päijät-Häme Central Hospital for enabling this study.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This study was financially supported by the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Tampere University Hospital.

-

Conflict of interest: Hanna Vuorimaa has received a lecture fee from AbbVie. Heini Pohjankoski has received travel and congress fees from Pfizer, AbbVie, and Roche. Maiju Hietanen has received travel and congress fees from Pfizer, AbbVie, Roche, and Celgene. Marja Mikkelsson has received lecture fees from Orionpharma, Medtronic, Pfizer, and MSD. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this study.

-

Informed consent: All patients and their parents received both oral and written information about the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

-

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol and procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Päijät-Häme Hospital District. Approval number EC, R12119.

References

[1] Kanstrup M, Wicksell RK, Kemani M, Lipsker CW, Lekander M, Holmströn L. A clinical pilot study of individual and group treatment for adolescents with chronic pain and their parents: effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on functioning. Children 2016;3:30.10.3390/children3040030Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Maynard C, Amari A, Wieczorek B, Christensen JR, Slifer KJ. Interdisciplinary behavioral rehabilitation of pediatric pain-associated disability: retrospective review of an inpatient treatment protocol. J Pediatr Psychol 2010;35:128–37.10.1093/jpepsy/jsp038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Agoston AM, Gray LS, Logan DE. Pain in School: patterns of pain-related school impairment among adolescents with primary pain conditions, juvenile idiopathic arthritis pain, and pain-free peers. Children 2016;3:1–9.10.3390/children3040039Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Logan DE, Simons LE, Carpino E. Too sick for school? Parent influences on school functioning among children with chronic pain. Pain 2012;153:437–43.10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Pielech M, Vowles K, Wicksell R. Acceptance and commitment therapy for pediatric chronic pain: theory and application. Children 2017;4:1–12.10.3390/children4020010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Morley S, Williams A, Eccleston C. Examining the evidence about psychological treatments for chronic pain: time for a paradigm shift. Pain 2013;154:1929–31.10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.049Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Simons LE, Smith A, Ibagon C, Coakley R, Logan DE, Schechter N, Borsook D, Hill JC. Pediatric pain screening tool. Rapid identification of risk in youth with pain complaints. Pain 2015;156:1511–8.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000199Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med 1993;55:234–47.10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Stein K, Pearson RM, Stein A, Zazel M. The predictive value of childhood recurrent abdominal pain for adult emotional disorders, and the influence of negative cognitive style. Findings from a cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185643.10.1371/journal.pone.0185643Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Kashikar-Zuck S, Sil S, Lynch-Jordan AM, Ting TV, Peugh J, Schikler KN, Hashkes PJ, Arnold LM, Passo M, Richards-Mauze MM, Powers SW, Lovell DJ. Changes in pain coping, catastrophizing, and coping efficacy after cognitive-behavioral therapy in children and adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia. J Pain 2013;14:492–501.10.1016/j.jpain.2012.12.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Wicksell RK, Olsson GL, Hayes SC. Mediators of change in acceptance and commitment therapy for pediatric chronic pain. Pain 2011;152:2792–801.10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Chatkoff DK, Leonard MT, Maier KJ. Pain catastrophizing differs between and within West Haven-Yale Multidimensonal Pain Inventory (MPI) pain adjustment classifications: theoretical and clinical implications from preliminary data. Clin J Pain 2015;31:349–54.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000117Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Wicksell RK, Kanstrup M, Kemani MK, Holmström L. Pain interference mediates the relationship between pain and functioning in pediatric chronic pain. Front Psychol 2016;7:1–8.10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01978Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Marttinen MK, Santavirta N, Kauppi MJ, Pohjankoski H, Vuorimaa H. Validation of the Pain Coping Questionnaire in Finnish. EJP 2018;22:101625.10.1037/t72662-000Search in Google Scholar

[15] Eccleston C, Fisher E, Vervoort T, Crombez G. Worry and catastrophizing about pain in youth: a reappraisal. Pain 2012;153:1560–2.10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Simons L, Kaczynski K. The fear avoidance model of chronic pain: examination for pediatric application. J Pain 2012;13:827–35.10.1016/j.jpain.2012.05.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Trost Z, Strachan E, Sullivan M, Vervoort T, Avery AR, Afari N. Heritability of pain catastrophizing and associations with experimental pain outcomes: a twin study. Pain 2015;156: 514–20.10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460326.02891.fcSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Welkom, JS, Hwang WT, Guite JW. Adolescent pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between protective parental responses to pain and disability over time. J Pediatr Psychol 2013;38:541–50.10.1093/jpepsy/jst011Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experimental approach to behavioral change. New York: Guilford Press, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams ACDC, Lewandowski A, Morley S, Fisher E, Law E. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD003968.10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Palermo TM, Eccleston C, Lewandowski A, Williams AC, Morley S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. Pain 2010;148:387–97.10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Palermo TM, Law EF, Zhou C, Holley AL, Logan D, Tai G. Trajectories of change during a randomized controlled trial of internet delivered psychological treatment for adolescents chronic pain: how does pain and function relate? Pain 2015;156:626–34.10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460355.17246.6cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Tabor A, Keogh E, Eccleston C. Embodied pain – negotiating the boundaries of possible action. Pain 2017;0:1–5.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000875Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Odell S, Logan DE. Pediatric pain management: the multidisciplinary approach. J Pain Res 2013;6:785–90.10.2147/JPR.S37434Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Hechler T, Ruhe A-M, Schmidt P, Hirsch J, Wager J, Dobe M, Krummenauer F, Zernikow B. Inpatient-based intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment for highly impaired children with severe chronic pain: randomized controlled trial of efficacy and economic effects. Pain 2014;155:118–28.10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Eccleston C, Fisher E, Law E, Bartlett J, Palermo TM. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;15:CD009660.10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Wicksell RK, Kemani M, Jensen K, Kosek E, Kadetoff D, Sorjonen K, Ingvar M, Olsson GL. Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. EJP 2003;17:599–611.10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00224.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Wicksell RK, Melin M, Lekander M, Olsson GL. Evaluating effectiveness of exposure and acceptance strategies to improve functioning and quality of life in longstanding pediatric pain – a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2009;14:248–57.10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Ross AC, Simons LE, Feinstein AB, Yoon IA, Bhandari RP. Social risk and resilience factors in adolescent chronic pain: examining the role of parents and peers. J Pediatr Psychol 2018;43:303–13.10.1093/jpepsy/jsx118Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Hoftun G, Romundstad P, Rygg M. Association of parental chronic pain with chronic pain in adolescent and young adult. Family linkage data from the HUNT study. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:61–9.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.422Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Law E, Fisher E, Howard WJ, Levy R, Ritterband L, Palermo TM. Longitudinal change in parent and child functioning after internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain 2017;158:1992–2000.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000999Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Lynch-Jordan AM, Kashikar-Zuck S, Szabova A, Goldschneider KR. The interplay of parent and adolescent catastrophizing and its impact on adolescents’ pain, functioning, and pain behavior. Clin J Pain 2013;29:681–8.10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182757720Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Enright PL. The six-minute walk test. Respir Care 2003;48:783–5.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Faggiano P, D’Aloia A, Gualeni A, Lavatelli A, Giordano A. Assessment of oxygen uptake during 6-minute walking test on patients with heart failure: preliminary experience with a portable device. Am Heart J 1997;134:203–6.10.1016/S0002-8703(97)70125-XSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Mikkelsson M, Salminen JJ, Kautiainen H. Non-specific musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents: prevalence and 1-year persistence. Pain 1997;73:29–35.10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00073-0Search in Google Scholar

[36] Vuorimaa H, Tamm K, Honkanen V, Komulainen E, Konttinen YT, Santavirta N. Pain in juveline idiopathic arthritis – a family matter. Childrens Health Care 2011;40:34–52.10.1080/02739615.2011.537937Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ruperto N, Ravelli A, Pistorio A, Malattia C, Cavuto S, Gado-West L, Tortorelli A, Landgraf JM, Singh G, Martini A. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the childhood health assessment questionnaire (CHAQ) and the child health questionnaire (CHQ) in 32 countries. Review of the general methodology. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;19:S1–9.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Pelkonen P, Ruperto N, Honkanen V, Hannula S, Savolainen A, Lahdenne P. The Finnish version of the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) and the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;19:S55–9.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression, Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol Bull 1985;21:995–8.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Reid GJ, Gilbert CA, McGrath PJ. The Pain Coping Questionnaire: preliminary validation. Pain 1988;76:83–96.10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00029-3Search in Google Scholar

[41] El-Metwally A, Salminen JJ, Auvinen A, Kautiainen H, Mikkelsson M. Prognosis on non-specific musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents: a prospective 4-year follow-up study till adolescence. Pain 2004;110:550–9.10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Ellonen N, Kääriäinen J, Autio V. Adolescent depression and school social support. A multilevel analysis of Finnish sample. J Community Psychol 2008;4:552–67.10.1002/jcop.20254Search in Google Scholar

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Systemic inflammation firmly documented in chronic pain patients by measurement of increased levels of many of 92 inflammation-related proteins in blood – normalizing as the pain condition improves with CBT-based multimodal rehabilitation at Uppsala Pain Center

- Systematic review

- Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients and effects of a multimodal pain rehabilitation program

- Chronic Widespread Pain in a tertiary pain clinic: classification overlap and use of a patient generated quality of life instrument

- Symptom reduction and improved function in chronic CRPS type 1 after 12-week integrated, interdisciplinary therapy

- Chronic pain after bilateral thoracotomy in lung transplant patients

- Reference values of conditioned pain modulation

- Risk severity moderated effectiveness of pain treatment in adolescents

- Pain assessment in hospitalized spinal cord injured patients – a controlled cross-sectional study

- Risk-based targeting of adjuvant pregabalin treatment in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled trial

- The impact of comorbid pain and depression in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey

- Observational study

- The utility/futility of medications for neuropathic pain – an observational study

- Posttraumatic stress and autobiographical memory in chronic pain patients

- Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017

- Characteristics of women with chronic pelvic pain referred to physiotherapy treatment after multidisciplinary assessment: a cross-sectional study

- The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1,712 patients

- Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study

- Original experimental

- Interpretation bias in the face of pain: a discriminatory fear conditioning approach

- Taboo gesticulations as a response to pain

- Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment

- Muscle stretching – the potential role of endogenous pain inhibitory modulation on stretch tolerance

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical registries are essential tools for ensuring quality and improving outcomes in pain medicine

- Fibromyalgia in biblical times

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Systemic inflammation firmly documented in chronic pain patients by measurement of increased levels of many of 92 inflammation-related proteins in blood – normalizing as the pain condition improves with CBT-based multimodal rehabilitation at Uppsala Pain Center

- Systematic review

- Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients and effects of a multimodal pain rehabilitation program

- Chronic Widespread Pain in a tertiary pain clinic: classification overlap and use of a patient generated quality of life instrument

- Symptom reduction and improved function in chronic CRPS type 1 after 12-week integrated, interdisciplinary therapy

- Chronic pain after bilateral thoracotomy in lung transplant patients

- Reference values of conditioned pain modulation

- Risk severity moderated effectiveness of pain treatment in adolescents

- Pain assessment in hospitalized spinal cord injured patients – a controlled cross-sectional study

- Risk-based targeting of adjuvant pregabalin treatment in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled trial

- The impact of comorbid pain and depression in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey

- Observational study

- The utility/futility of medications for neuropathic pain – an observational study

- Posttraumatic stress and autobiographical memory in chronic pain patients

- Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017

- Characteristics of women with chronic pelvic pain referred to physiotherapy treatment after multidisciplinary assessment: a cross-sectional study

- The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1,712 patients

- Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study

- Original experimental

- Interpretation bias in the face of pain: a discriminatory fear conditioning approach

- Taboo gesticulations as a response to pain

- Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment

- Muscle stretching – the potential role of endogenous pain inhibitory modulation on stretch tolerance

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical registries are essential tools for ensuring quality and improving outcomes in pain medicine

- Fibromyalgia in biblical times