Abstract

Background and aims

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is related to more severe pain among chronic pain patients. PTSD is also related to dysfunctions or biases in several cognitive processes, including autobiographical memory. The autobiographical memories are our memories of specific personal events taking place over a limited amount of time on a specific occasion. We investigated how two biases in autobiographical memory, overgeneral memory style and negative emotional bias were related to pain, PTSD and trauma exposure in chronic pain patients.

Methods

Forty-three patients with diverse chronic pain conditions were recruited from a specialist pain clinic. The patients were evaluated for psychiatric diagnosis, with a diagnostic interview Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I) and for exposure to the most common types of traumatic events with the Life Event Checklist (LEC). The patients were tested with the 15-cue-words version of the Autobiographical Memory Test (AMT). In this test the participants are presented verbally to five positive, five neutral and five negative cue words and asked to respond with a personal, episodic memory associated with the cue word. The participant’s responses were coded according to level of specificity and emotional valence. Pain intensity was assessed on a Visual Analogy Scale (VAS) and extent of pain by marking affected body parts on a pre-drawn body figure. Comparisons on autobiographical memory were made between PTSD and non-PTSD groups, and correlations were computed between pain intensity and extent of pain, trauma exposure and autobiographical memory.

Results

PTSD and extent of pain were significantly related to more negatively emotionally valenced memory responses to positive and negative cue words. There were no significant difference in response to neutral cue words. PTSD status and pain intensity were unrelated to overgeneral autobiographical memory style.

Conclusions

A memory bias towards negatively emotionally valenced memories is associated with PTSD and extent of pain. This bias may sustain negative mood and thereby intensify pain perception, or pain may also cause this memory bias. Contrary to our expectations, pain, trauma exposure and PTSD were not significantly related to an overgeneral memory style.

Implications

Cognitive therapies that have an ingredient focusing on amending memory biases in persons with comorbid pain and PTSD might be helpful for this patient population. Further investigations of negative personal memories and techniques to improve the control over these memories could potentially be useful for chronic pain treatment.

1 Introduction

Chronic pain is among the most common and costly health problems in Europe [1] and is associated with a two- to threefold increased risk of mental disorders [2]. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder being caused by the person being exposed to death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence. These events, called potentially traumatizing events, can further be divided into intentional and non-intentional. Intentional events are deliberate harm infliction, such as interpersonal violence, torture, and war-related trauma. In non-intentional events, the harm is not caused deliberately, as with natural disasters and serious illness in someone close. Non-intentional events are related to more transitory PTSD symptoms, while intentional events are related to more enduring symptoms and negative treatment outcomes [3], [4].

PTSD is associated with a doubled risk of chronic pain [5], [6] and may be even more strongly associated with widespread chronic pain [7]. Why PTSD and chronic pain are associated is largely unknown, but both biological and cognitive factors may be important. Memory is a cognitive domain central to PTSD symptomatology, and PTSD may be seen as a memory disorder [8], where PTSD symptomatology is caused and/or sustained by memory dysfunctions or biases, including lessened control of memory retrieval processes [9]. According to the memory based models of PTSD, fragmented, and highly emotional cognitive material may enter consciousness uncontrolled. These intrusive memories may, act as drivers for PTSD symptoms such as avoidance and hyperarousal. Therefore, understanding memory dysfunctions might improve our understanding of how PTSD is related to chronic pain.

One memory function of particular interest in traumatic stress research is autobiographical memory. Autobiographical memories are memories of specific personal events taking place over a limited amount of time on a specific occasion (e.g. “Last Friday afternoon, I saw a dead cat in the park”). The autobiographical memory system is strongly related to our identity and serves crucial functions such as using previous experiences to solve problems, navigate daily life and plan future action [10], [11], [12]. The most-investigated autobiographical memory bias related to traumatic stress is overgeneral memory style [13]. A person with an overgeneral autobiographical memory style tends to be unable to report specific personal episodic memories when prompted. Rather, the person tends to retrieve general memories of repeated events, such as “On Fridays I go for a walk in the park”, or memories that refer to extended periods of time (“I used to own a blue bike”) [14], [15].

Compared to the amount of literature on traumatic stress and depression, there is limited research on autobiographical memory in people with chronic pain. A majority of the early autobiographical memory studies investigated pain-relevant memories [16], [17], [18]. More recent studies have investigated autobiographical memory functioning in chronic pain patients more broadly and with similar procedures as in posttraumatic stress research. Compared to healthy controls, people with chronic pain show an overgeneral memory bias, which is related to depression and feelings of being unable to cope with pain [19], and report more negative emotional memories when in pain [20].

The current study elaborates on previous research by investigating autobiographical memory biases in chronic pain patients in light of their previous trauma exposure (divided into intentional and non-intentional) and PTSD status. If memory dysfunctions are important drivers for PTSD symptoms, these memory dysfunctions might also increase or sustain pain and functional disability in patients exposed to trauma. Trauma-exposed patients with an overgeneral memory style may more easily succumb to feelings of hopelessness and despair in ways similar to those reported from research on autobiographical memory in depression [21].

We sought to investigate whether an overgeneral memory style and a bias towards reporting memories with negative emotional valence are related to current pain and extent of pain in chronic pain patients. We hypothesized that an overgeneral memory style and a tendency towards retrieving memories with negative emotional memory valence would be related to trauma exposure, PTSD, and pain.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Patients at their first appointment at a large university hospital specialized pain clinic were invited to participate in an interview study on traumatic stress, memory, and pain. The patients were referred by their general practitioner or other departments at the hospital for assessment and treatment of chronic pain. This clinic offers multidisciplinary pain treatment by a specialist team with anesthesiologist, physiotherapist, nurse, and psychologist. All patients with an adequate understanding of Norwegian were eligible for inclusion. The patients were interviewed by the first author, a specialist in clinical psychology. All new patients at the clinic on days of data collection were approached for participation, and approximately half chose to participate. The most common reason given for not participating was lack of time. Written informed consent was collected from all participants prior to the interview, and all participants received 200 NOK (25 €) in compensation. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Health Region South-East (ID: 2010/1646a).

2.2 Measurement

Background demographic information was collected from electronic patient records.

2.2.1 Trauma exposure

The participant’s trauma exposure was assessed with the Life Events Checklist (LEC). The LEC has 17 items with four response categories (0=not relevant, 1=confronted with, 2=witnessed, and 3=it happened to me). Other studies have reported that the LEC has adequate reliability and validity [22]. For further analysis, the LEC items were divided into items assessing exposure to intentional traumatic events such as interpersonal violence, sexual abuse, and war, and items assessing non-intentional exposure such as accidents, natural disaster, and illness.

2.2.2 Psychiatric diagnosis

The M.I.N.I International Neuropsychiatric Interview PLUS (MINI 5.0.0, Norwegian adaptation, hereafter MINI) is a structured diagnostic interview assessing Axis I DSM IV psychiatric disorders [23]. The Norwegian version of the MINI has been validated previously and found to have adequate reliability [24].

2.2.3 Pain

Current pain intensity was assessed by self-report, where the participants rated their pain on a 10 cm visual analog scales (VAS) with the ends of the scale were marked as “No pain” and “Worst possible pain”. Extent of pain was assessed on a pre-drawn body picture where the participants marked their pain-afflicted body parts.

2.2.4 Autobiographical memory test

Participants were presented with the Norwegian version of the autobiographical memory test with 15 cue words: five positive, five neutral and five negative. The AMT has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in previous research [25] and has previously been used in research in Norwegian speaking populations [26]. The specificity and emotional valence of the recorded memories were coded by two independent expert coders blind to the participant’s diagnostic status. All data analyses were performed with SPSS version 22.

3 Results

Demographic information, trauma exposure and self-reported pain are presented according to PTSD status in Table 1. The participants were between 24 and 66 years old (M=43.3, SD=10.2), and 27 (63%) were women. All participants reported experiencing pain for at least 6 months. The most common types of pain were muscular skeletal pain and neuropathic pain. The participants scored between 0 and 44 on the LEC (M=13.3, SD=9.2). Twelve participants met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Women were overrepresented in the PTSD group, where 11 of the 12 participants were women. The number of cue words that elicited specific memories on the autobiographical memory test ranged from 2 to 14 (M=9.2, SD=3.2).

Participants demographics, trauma exposure, and pain by PTSD status.

| All participants | PTSD (n=13) | Non-PTSD (n=30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (M) | 42.3 | 43.7 | 41.5 |

| Gender (% female)a | 63 | 92.3 | 50 |

| Trauma exposurea | 13.33 | 18.2 | 11.2 |

| Intentional eventsa | 5.7 | 7.3 | 3.8 |

| Non-intentional events | 7.6 | 8.2 | 7.3 |

| Pain | |||

| VAS | 5.7 | 6.1 | 5.3 |

| Extenta | 3.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 |

-

aSign at p<0.05.

Our first analysis investigated whether trauma exposure was related to autobiographical memory specificity (see Table 2). The bivariate correlation between trauma exposure and autobiographical memory specificity (r=0.09, ns) was not significant. When trauma exposure was spilt into non-intentional and intentional events, intentional events and autobiographical memory specificity were borderline significantly correlated (r=0.31, p<0.06), while non-intentional event and autobiographical memory specificity was not significantly correlated (r=0.15, ns).

Autobiographical memory, trauma exposure, PTSD and pain: correlations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ABM specificity | ||||||

| 2. Trauma exposure | −0.09 | |||||

| 3. Intentional traumatic events | −0.29 | 0.81b | ||||

| 4. Non-intentional traumatic events | 0.15 | 0.81b | 0.31a | |||

| 5. PTSD | 0.16 | 0.36a | 0.50b | 0.36a | ||

| 6. VAS pain | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.19 | |

| 7. Extent of pain | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.33a | 0.24 | 0.46b | 0.26 |

-

ABM=autobiographical memory; VAS pain=current pain report on a 10 point Visual Analogue Scale.

-

aCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

-

bCorrelation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Our second analysis investigated the relationship between PTSD, autobiographical memory specificity, and pain. While there was a tendency towards participants in the non-PTSD group reporting more specific memories, there was no significant difference in specificity between participants with PTSD (M=9.51, SD=3.05) and other participants [M=10.42, SD=3.23, F(1.36)=0.56, ns]. Further, there was no significant relationship between autobiographical memory specificity and VAS score (r=0.01, ns) or extent of pain (r=0.07, ns). Because the PTSD patients were almost exclusively women, these analyses were repeated controlling for gender, with similar findings.

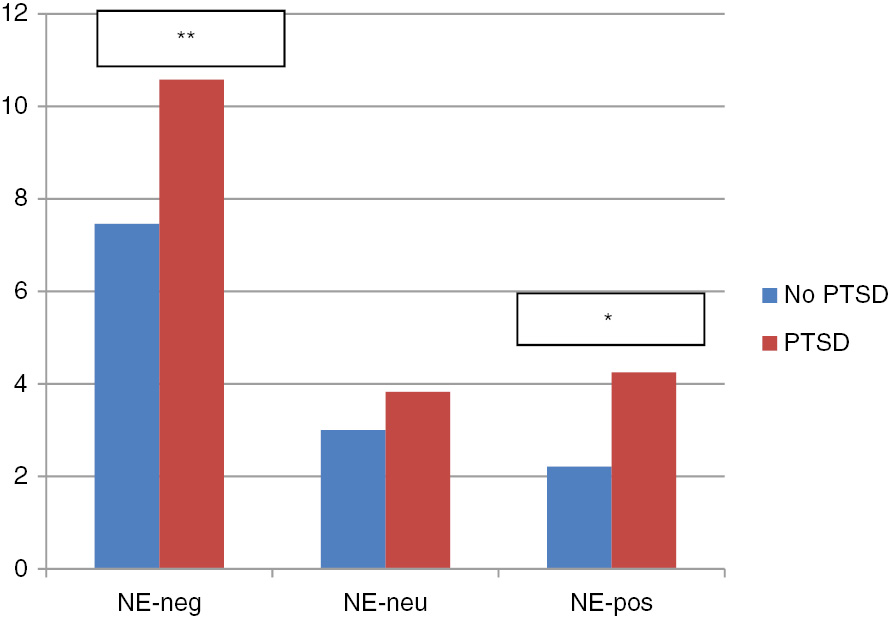

Third, we analyzed the emotional valence of the reported memories (see Fig. 1). This analysis was performed in two ways; the first included all memory responses, while the second included only specific memory responses. As these two analyses led to similar results, they are jointly reported. Participants with PTSD reported memories with more negative emotional valence when presented with cue words that were negatively (t (39)=−3.1, p<0.05) and positively (t (39)=−2.4, p<0.05) valenced. We found the same effect for extent of pain; participants with more pain-affected body parts reported significantly more negative emotionally valenced memories to positive cue words (r=0.44, p<0.05). VAS pain score and trauma exposure were unrelated to memory valence. There was no effect of neutral valenced cue words on memory retrieval, nor any effect for any of the included variables on the positive emotional valence of reported memories.

Negative emotional valence by negative, neutral, and positive cue words and PTSD. NE-neg=negative emotional valenced memory response to negative cue words; NE-neu=negative emotional valenced memory response to neutral cue words; NE-pos=negative emotional valenced memory response to positive cue words. *F (1.36)=9.73, p=0.004. **F (1.36)=5.57, p=0.024.

4 Discussion

We investigated the relationship between autobiographical memory biases, trauma exposure, PTSD, and pain in chronic pain patients. We hypothesized that overgeneral and more negative emotionally valenced autobiographical memories would be related to trauma exposure, PTSD, and pain. Our hypotheses were partially supported. Participants exposed to intentional trauma, participants with PTSD, and participants with more pain-affected body parts retrieved more negative emotional memories in response to positive and negative cue words. The hypothesis about overgeneral autobiographical memory being related to PTSD and pain was not supported.

When we analyzed the relationship between overgeneral memory and trauma exposure, interesting differences emerged when dividing trauma exposure into intentional and non-intentional events. Non-intentional events were not statistically related to overgeneralized memory, but there was a tendency towards this exposure being related to more specific memory. Exposure to intentional events was related to more overgeneral memories, as hypothesized. There is, to our knowledge, little research comparing intentional and non-intentional events in relation to overgeneral memory. However, other studies have reported exposure to intentional events to be related to more psychological damage and higher conditional risk for PTSD [4], [27], [28]. Our finding is therefore consistent with general findings within the PTSD literature. This difference in trauma exposure may also be relevant for the risk of chronic pain, and should be replicated in studies with bigger sample.

Participants with PTSD and those with more pain-affected body parts reported more negative emotional memories in response to positive and negative valenced cue words. People with PTSD may have less emotional control [9], and therefore experience more negative emotional memories popping up uncontrollably. These negative memories could lead to more negative current emotions and thereby maintain chronic pain as described in the mutual maintenance model of chronic pain [29]. The positive relationship between PTSD and the extent of pain could also be due to common underlying psychophysiology causes, such as chronic hyperarousal. Chronic hyperarousal is a central PTSD symptom [30] and might explain how PTSD is related to autoimmune illnesses. Boscarino suggested a model where higher level of T-cells and lower cortisol levels are results of trauma exposure and a risk factor for both PTSD and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [31]. Since rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia are defined by more generalized pain, this model might explain the why persons with PTSD in particular have more generalized rather than more localized pain [31], [32].

Generalized pain, as opposed to localized chronic pain, may represent another type of chronic pain where central cognitive and affective processes are more important for the pain experience, possibly through mechanisms such as central sensitization [33], [34]. People with more generalized chronic pain have higher levels of psychosocial disability [35], [36] than people with localized pain. Thus, the negative bias in the retrieved memories in people with more generalized pain might be related to low levels of coping and high levels of hopelessness.

We found no overgenerality effect related to PTSD in this study. There might be several reasons for this somewhat unexpected finding. One is related to all participants in the study had chronic pain, with average medium to high levels of pain at time of testing. As current pain affect memory functioning, the failure to find the expected overgenerality effect may be due to all participants in this study reporting significant levels of pain and, therefore, more overgeneral memories. Chronic pain is related to reduced working memory [37], which is one of the cognitive processes involved in autobiographical retrieval [21], and consequently all participants may have had reduced specificity independent of PTSD status. This hypothesis is consistent with [19] who found that people with chronic pain report more overgeneral memories compared to healthy controls. The high level of pain in all participants might therefore have washed out an effect of trauma exposure or PTSD on memory specificity. Additional controls such as a group of PTSD patients without pain and healthy controls would have been useful for interpreting this finding.

Further, we dichotomized the PTSD symptoms into two groups according to diagnosis, rather than using the PTSD symptoms to form a continuous symptoms scale. A continuous PTSD measure would have offered more statistical power and a better chance to detect small effect sizes. It is worth noting, however, that there was only a small difference between the PTSD and the non-PTSD group, and there was a tendency towards those in the PTSD group reporting more specific memories (about 1/3 of a SD). Therefore, our finding of no overgenerality effect related to PTSD is less likely to have been caused by low statistical power alone.

However, the rather small sample size in this study limited the chance of finding a small to medium-sized real effect and the possibilities of building more complex models investigating interactions and including control variables. A larger sample size would have allowed more accurate effect estimates.

In sum, this study reported several potentially important associations between autobiographical memory biases, that are non-specific i.e. overgeneral or have a negative emotional valence, PTSD, and chronic pain. Our findings were mainly in line with previous research, except that we did not find any overgenerality effect. Our findings have relevance for development of models for chronic pain and PTSD. While cognitive-based therapies for pain have some documented effect [38], the effect sizes are rather small and further developments are needed. The clinical implications of these findings is that cognitive therapies that have an ingredient focusing on amending memory biases in persons with comorbid pain and PTSD, might be helpful for this patient population. Further investigations of negative personal memories and techniques to improve the control over these memories could potentially be useful for chronic pain treatment.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: The data collection, analysis and writing of this manuscript were supported by funding from Akershus University Hospital.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was collected from all participants prior to the study interview.

-

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Health Region South-East (ID: 2010/1646a).

References

[1] Leadley RM, Armstrong N, Lee YC, Allen A, Kleijnen J. Chronic diseases in the European union: the prevalence and health cost implications of chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2012;26:310–25.10.3109/15360288.2012.736933Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, Alonso J, Karam E, Angermeyer MC, Borges GLG, Bromet EJ, De Girolamo G, De Graaf R, Gureje O. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008;9:883–91.10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, Degenhardt L, de Girolamo G, Dinolova RV, Ferry F, Florescu S. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2017;8:1353383.10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Santiago PN, Ursano RJ, Gray CL, Pynoos RS, Spiegel D, Lewis-Fernandez R, Friedman MJ, Fullerton CS. A systematic review of PTSD prevalence and trajectories in DSM-5 defined trauma exposed populations: intentional and non-intentional traumatic events. PLoS One 2013;8:1–5.10.1371/journal.pone.0059236Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Zatzick DF, Russo JE, Katon W. Somatic, posttraumatic stress, and depressive symptoms among injured patients treated in trauma surgery. Psychosomatics 2003;44:479–84.10.1176/appi.psy.44.6.479Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Andreski P, Chilcoat H, Breslau N. Post-traumatic stress disorder and somatization symptoms: a prospective study. Psychiatry Res 1998;79:131–8.10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00026-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Afari N, Ahumada SM, Wright LJ, Golnari G, Reis V, Cuneo JG. Psychological trauma and functional somatic syndromes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2015;76:2–11.10.1097/PSY.0000000000000010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Rubin DC, Berntsen D, Bohni MK. A memory-based model of posttraumatic stress disorder: evaluating basic assumptions underlying the PTSD diagnosis. Psychol Rev 2008;115:985–1011.10.1037/a0013397Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] DiGangi JA, Gomez D, Mendoza L, Jason LA, Keys CB, Koenen KC. Pretrauma risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:728–44.10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Blix I, Brennen T. Mental time travel after trauma: the specificity and temporal distribution of autobiographical memories and future-directed thoughts. Memory 2011;19:956–67.10.1080/09658211.2011.618500Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim ASN. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 2008;21:489–510.10.1162/jocn.2008.21029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Sutherland K, Bryant RA. Social problem solving and autobiographical memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 2008;46:154–61.10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ono M, Devilly GJ, Shum DHK. A meta-analytic review of overgeneral memory: the role of trauma history, mood, and the presence of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Trauma Theory 2016;8:157–64.10.1037/tra0000027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Williams JMG, Broadbent K. Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. J Abnorm Psychol 1986;95:144–9.10.1037//0021-843X.95.2.144Search in Google Scholar

[15] Williams JMG, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Herman D, Raes F, Watkins E, Dalgleish T. Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychol Bull 2007;133:122–48.10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Bryant RA. Memory for pain and affect in chronic pain patients. Pain 1993;54:347–51.10.1016/0304-3959(93)90036-OSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Feine JS, Lavigne GJ, Dao TTT, Morin C, Lund JP. Memories of chronic pain and perceptions of relief. Pain 1998;77:137–41.10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00089-XSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Matera D, Morelli M, La Grua M, Sassu B, Santagostino G, Prioreschi G. Memory distortion during acute and chronic pain recalling. Minerva Anestesiol 2003;69:775–83.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Liu X, Liu Y, Li L, Hu Y, Wu S, Yao S. Overgeneral autobiographical memory in patients with chronic pain. Pain Med 2014;15:432–9.10.1111/pme.12355Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Meyer P, Karl A, Flor H. Pain can produce systematic distortions of autobiographical memory. Pain Med 2015;16:905–10.10.1111/pme.12716Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Williams JMG. Capture and rumination, functional avoidance, and executive control (CaRFAX): three processes that underlie overgeneral memory. Cogn Emot 2006;20:548–68.10.1080/02699930500450465Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment 2004;11:330–41.10.1177/1073191104269954Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:22–33.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Mordal J, Gundersen Ø, Bramness J. Norwegian version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview: feasibility, acceptability and test-retest reliability in an acute psychiatric ward. Eur Psychiatry 2010;25:172–7.10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.02.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Griffith JW, Kleim B, Sumner JA, Ehlers A. The factor structure of the Autobiographical Memory Test in recent trauma survivors. Psychol Assess 2012;24:640–6.10.1037/a0026510Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Blix I, Brennen T. Intentional forgetting of emotional words after trauma: a study with victims of sexual assault. Front Psychol 2011;2:1–8.10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00235Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Alisic E, Zalta AK, Van Wesel F, Larsen SE, Hafstad GS, Hassanpour K, Smid GE. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatrysychiatry 2014;204:335–40.10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131227Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Kessler RC, Rose S, Koenen KC, Karam EG, Stang PE, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Hill ED, Liberzon I, McLaughlin KA, McLean SA. How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry 2014;13:265–74.10.1002/wps.20150Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev 2001;21:857–77.10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00071-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] McNally RJ, Robinaugh DJ, Wu GWY, Wang L, Deserno MK, Borsboom D. Mental disorders as causal systems: a network approach to posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Sci 2015;3:836–49.10.1177/2167702614553230Search in Google Scholar

[31] Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004;1032:141–53.10.1196/annals.1314.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Stojanovich L, Marisavljevich D. Stress as a trigger of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev 2008;7:209–13.10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Neblett R, Cohen H, Choi Y, Hartzell MM, Williams M, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI): establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain 2013;14:438–45.10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Nijs J, Meeus M, Van Oosterwijck J, Roussel N, De Kooning M, Ickmans K, Matic M. Treatment of central sensitization in patients with “unexplained” chronic pain: what options do we have? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2011;12:1087–98.10.1517/14656566.2011.547475Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM, Bruusgaard D. Does the number of musculoskeletal pain sites predict work disability? A 14-year prospective study. Eur J Pain 2009;13:426–30.10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM, Benth JS, Bruusgaard D. Number of pain sites is associated with demographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors in the general population. Eur J Pain 2008;12:742–8.10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.11.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering JK, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Evidence for working memory deficits in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2013;154:1181–96.10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Eccleston C, Williams A, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults (Review). Cochrane Libr 2009:1–82.10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Systemic inflammation firmly documented in chronic pain patients by measurement of increased levels of many of 92 inflammation-related proteins in blood – normalizing as the pain condition improves with CBT-based multimodal rehabilitation at Uppsala Pain Center

- Systematic review

- Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients and effects of a multimodal pain rehabilitation program

- Chronic Widespread Pain in a tertiary pain clinic: classification overlap and use of a patient generated quality of life instrument

- Symptom reduction and improved function in chronic CRPS type 1 after 12-week integrated, interdisciplinary therapy

- Chronic pain after bilateral thoracotomy in lung transplant patients

- Reference values of conditioned pain modulation

- Risk severity moderated effectiveness of pain treatment in adolescents

- Pain assessment in hospitalized spinal cord injured patients – a controlled cross-sectional study

- Risk-based targeting of adjuvant pregabalin treatment in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled trial

- The impact of comorbid pain and depression in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey

- Observational study

- The utility/futility of medications for neuropathic pain – an observational study

- Posttraumatic stress and autobiographical memory in chronic pain patients

- Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017

- Characteristics of women with chronic pelvic pain referred to physiotherapy treatment after multidisciplinary assessment: a cross-sectional study

- The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1,712 patients

- Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study

- Original experimental

- Interpretation bias in the face of pain: a discriminatory fear conditioning approach

- Taboo gesticulations as a response to pain

- Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment

- Muscle stretching – the potential role of endogenous pain inhibitory modulation on stretch tolerance

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical registries are essential tools for ensuring quality and improving outcomes in pain medicine

- Fibromyalgia in biblical times

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Systemic inflammation firmly documented in chronic pain patients by measurement of increased levels of many of 92 inflammation-related proteins in blood – normalizing as the pain condition improves with CBT-based multimodal rehabilitation at Uppsala Pain Center

- Systematic review

- Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients and effects of a multimodal pain rehabilitation program

- Chronic Widespread Pain in a tertiary pain clinic: classification overlap and use of a patient generated quality of life instrument

- Symptom reduction and improved function in chronic CRPS type 1 after 12-week integrated, interdisciplinary therapy

- Chronic pain after bilateral thoracotomy in lung transplant patients

- Reference values of conditioned pain modulation

- Risk severity moderated effectiveness of pain treatment in adolescents

- Pain assessment in hospitalized spinal cord injured patients – a controlled cross-sectional study

- Risk-based targeting of adjuvant pregabalin treatment in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled trial

- The impact of comorbid pain and depression in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey

- Observational study

- The utility/futility of medications for neuropathic pain – an observational study

- Posttraumatic stress and autobiographical memory in chronic pain patients

- Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017

- Characteristics of women with chronic pelvic pain referred to physiotherapy treatment after multidisciplinary assessment: a cross-sectional study

- The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1,712 patients

- Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study

- Original experimental

- Interpretation bias in the face of pain: a discriminatory fear conditioning approach

- Taboo gesticulations as a response to pain

- Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment

- Muscle stretching – the potential role of endogenous pain inhibitory modulation on stretch tolerance

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical registries are essential tools for ensuring quality and improving outcomes in pain medicine

- Fibromyalgia in biblical times