Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

-

Justine Binny

Abstract

Background and aims

There has been no comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain (LBP). The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the efficacy and safety of TENS for acute LBP.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CENTRAL, CINAHL and PsycINFO (inception to May 2018) for randomised placebo controlled trials. The primary outcome measure was pain relief in the immediate term (within 2-weeks of administration) assessed using the 100 mm visual analogue scale. A mean difference of at least 10 points on the 100-point pain scale was considered clinically significant. Methodological quality of the eligible studies was assessed using the PEDro scale and overall quality assessment rating was assessed using GRADE.

Results

Three placebo controlled studies (n = 192) were included. One low quality trial (n = 63) provides low quality evidence that ~30 min treatment with TENS in an emergency-care setting provides clinically worthwhile pain relief for moderate to severe acute LBP in the immediate term compared with sham TENS [Mean Difference (MD) – 28.0 (95% CI – 32.7, −23.3)]. Two other studies which administered a course of TENS over 4–5 weeks, in more usual settings provide inconclusive evidence; MD −2.75 (95% CI −11.63, 6.13). There was limited data on adverse events or long term follow-up.

Conclusions

The current evidence is insufficient to support or dismiss the use of TENS for acute LBP.

Implications

There is insufficient evidence to guide the use of TENS for acute LBP. There is low quality evidence of moderate improvements in pain with a short course of TENS (~30 min) during emergency transport of patients to the hospital. Future research should evaluate whether TENS has an opioid sparing role in the management of acute LBP.

1 Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a prevalent and costly condition worldwide [1]. In 2001, the estimated cost to Australians, both direct (including charges for hospitalisation, diagnosis, treatment) and indirect (for example, loss of income, early retirement) was over $9 billion [2]. Low back pain is the leading cause of global disability, and because of the ageing population, the burden is expected to increase [3]. The latest clinical guidelines for managing acute LBP suggest non-pharmacological interventions be used initially [4], [5]. This follows findings from recent studies which show treatment with simple analgesics such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs offer minimal or no benefit for acute LBP [6], [7]. Furthermore, the efficacy of more complex interventions such as opioid analgesics has not been established in this context [8].

A potential non-pharmacological approach to the management of acute LBP is transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS). TENS therapy involves placing electrodes on the skin to stimulate peripheral sensory nerves, at an appropriate intensity, in the hope of alleviating pain via descending modulatory pathways [9], [10], [11], [12]. It is a compact device that is easy to transport and integrate into existing pain management protocols, such as during emergency transport of patients with acute non-specific LBP [13]. The intervention can be self-administered but is also commonly used in practise, e.g. by physical therapists.

Most of the evidence around the use of TENS in LBP comes from studies of people with chronic LBP [14], [15], [16]. These studies provide mixed evidence, with some reporting worthwhile pain reduction [14] and others reporting short term benefits for disability but not pain [16]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE guideline does not endorse the use of TENS [17], citing an absence of evidence on effectiveness. Similarly, the Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) also does not recommend its use by physiotherapists [18].

Currently, however there is no consensus regarding the efficacy of TENS for the management of acute LBP. One review points to a potential role of TENS for acute LBP [19] however this review is now almost a decade old. As there are no current reviews of the effect of TENS on acute LBP, this project was conducted to systematically review the available literature, including a formal evaluation of research quality.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources and search

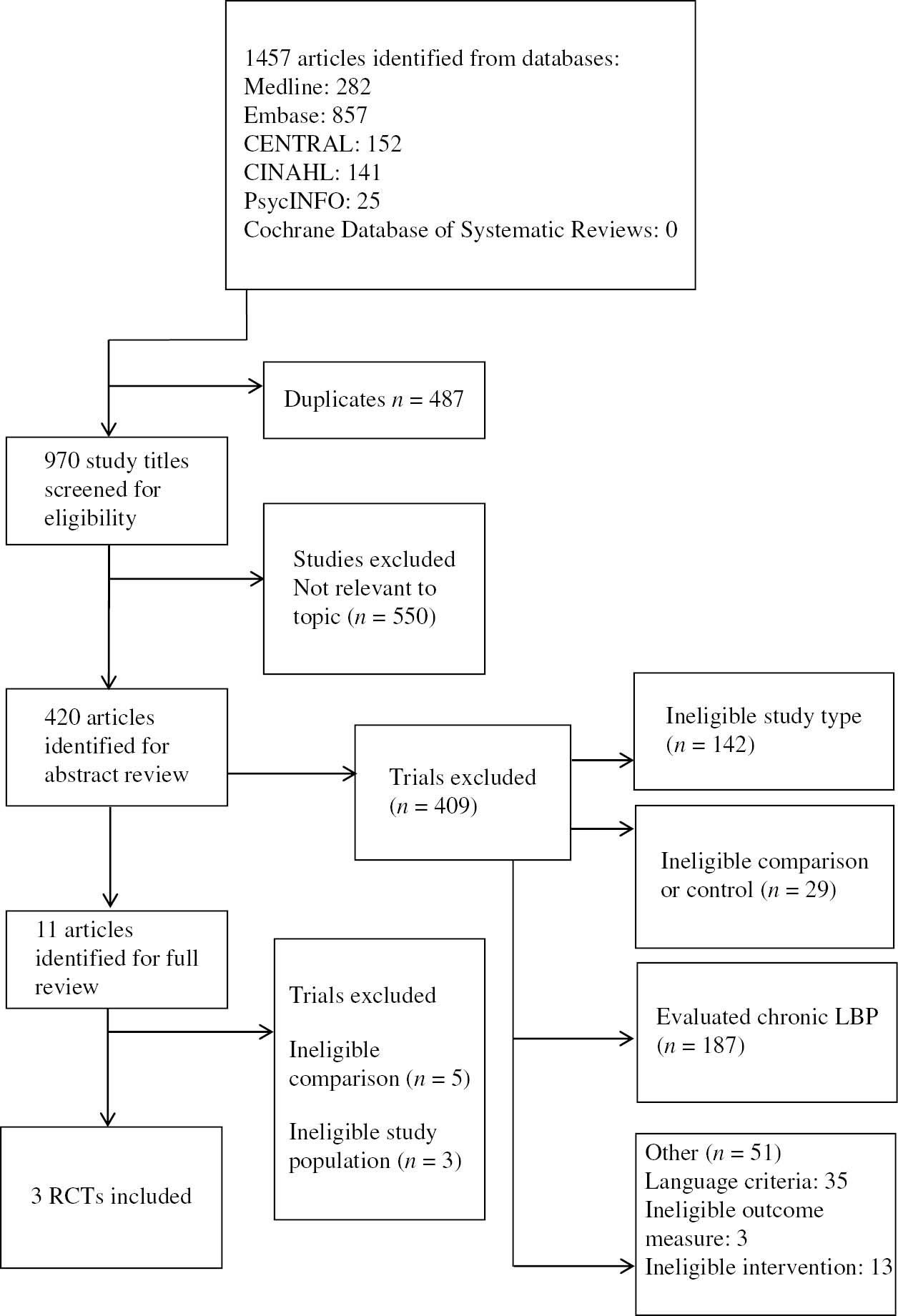

The electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (inception to May 2018) were searched for reports of placebo-controlled randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating TENS for acute LBP (Appendix Table 1). Additionally, we screened reference lists of included RCTs and relevant systematic reviews to identify any other relevant studies (Fig. 1).

Summary of search.

2.2 Study selection

We included English language RCTs evaluating TENS for acute, non-specific LBP. Two reviewers (CAS and JW) screened titles and abstracts of retrieved studies, and two reviewers drawn from a pool of three reviewers (JB, SG and CAS) independently inspected the full manuscript of potentially eligible RCTs to determine eligibility, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

2.3 Data extraction

Two reviewers drawn from a pool of three reviewers (JW, SG and CAS) independently extracted study and participant characteristics, and outcomes data from included studies. Missing data were obtained by contacting authors or estimated using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [20].

2.4 Outcomes

Trials were included if they reported on pain, disability or adverse events outcomes. Pain outcomes were converted to a common 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst possible pain) scale. The pain intensity measures used in the retrieved trials were visual analogue scale (VAS) scores (range, 0–100) and numerical rating scale (NRS) scores (range, 0–10). The NRS was converted to the same 0–100 scale as in the VAS, as these two pain measures have been shown to be highly correlated and when transformed, can be used interchangeably [21].

2.5 Data synthesis

We present results as mean differences (MD) expressed in points on a 0–100 pain scale and 95% confidence intervals rather than standardised mean differences (SMD). We considered treatment effects in the range 10–19 points as small; >20 points as moderate and >30 points as large. These values are consistent with the proposed thresholds for clinically important changes in pain response from the literature on chronic pain [22]. Effects <10 points were considered as not clinically meaningful [23].

2.6 Follow-up

Outcomes were grouped with respect to follow up period: immediate term (outcomes measured <2 weeks after administration of intervention), short term (outcomes measured between 2 and 6 weeks after the intervention) and intermediate term (outcomes measured 6–12 weeks after the intervention). We considered immediate term pain relief as the primary time point.

2.7 Quality assessment

Risk of bias was assessed by two reviewers (JB, SG or CAS) using the 11-item PEDro scale [24], [25], [26], which is a valid and reliable method of rating risk of bias of RCTs [24], [25], [26]. Each item (excluding the item for external validity) is scored as either present (1) or absent (0) to give a total score out of 10. Trials scoring <7/10 on the PEDro scale were defined as high risk of bias; those scoring 7 or more were considered at low risk of bias [25].

We used the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook [20] to determine a GRADE rating for the overall quality of the evidence for an intervention. This method is described elsewhere [27], [28], but briefly the quality of evidence was downgraded a level for each of four factors: poor study design [25% or more of trials, weighted by sample size, have a low PEDro score (<7/10)], inconsistency of results (25% or more of the trials, weighted by sample size, have results which are not in the same direction or evidence of clinical heterogeneity), imprecision (small sample size and/or wide 95% CI) and publication bias (assessed using funnel plot analysis/Egger’s regression test where there were 10 or more studies). Where Egger’s regression two-tailed p-value was <0.10, the overall quality of evidence was downgraded by one level [29]. It was not necessary to downgrade for indirectness (when the trial context is not the same as the review question) as this review evaluated administration of specific intervention (TENS). The quality of evidence was defined as “high quality”, “moderate quality”, “low quality”, and “very low quality” [20].

2.8 Data analysis

We planned to conduct meta-analysis using Review Manager (RevMan version 5.3) [30]. Where results could not be pooled (e.g. high heterogeneity, I2>85%), results from individual studies were assessed and reported separately. For adverse events data, we were interested in the proportion of participants experiencing one or more adverse events and where possible, calculating a risk ratio based on this information.

3 Results

A total of 1,457 articles were identified from the database search. After screening titles and abstracts, then full inspection of potentially eligible trials, we identified three eligible studies for inclusion in the efficacy analysis (n=192). All patients had acute LBP, with at least moderate pain intensity (four or more out of 10 on 0–10 pain rating scale). All of the eligible studies compared TENS with placebo TENS [13], [31], [32], however, one of these studies administered an additional exercise program in both groups (baseline care) [31]. Often the placebo group received treatment with an identical TENS unit that did not produce an output. In one of the studies [31] the absence of sensation was explained by “subliminal” stimulation.

A summary of the search is shown in Fig. 1, and the characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Details of the search are described in Appendix Table 1. Risk of bias assessments are provided in Table 2.

Characteristics of included trials.

| Study | Patient population | Intervention | Comparison | Length of treatment | Follow up | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertalanffy et al. [13] | Patients with acute LBP (with pain intensity >60 mm on VAS) who required emergency transport because of pain and immobilisation | 30 min of TENS therapy The TENS machine used was the TENStem eco (Pierenkemper GmbH, Ehringshausen, Germany) Output volt-age: 70 mA, frequency range: 0.5–120 Hz, pulse width: 60–300 ms, power input: 15 mA n=30 |

Sham TENS treatment n=33 |

30 min duration | On admission | Visual analogue pain scale (0–100 mm) |

| Lourenzi et al. [32] | Patients with acute LBP between 4 and 8 on a 10 point pain scale | Without causing pain or muscular contraction. Electrodes were placed crosswise in the paravertebral region. In PG the same procedures were adopted, but without electrical stimulation Treatment consisted of 10 sessions lasting 30 min each |

Placebo TENS n=36 |

Two times/week for 5 weeks | Assessments were at: T0 (baseline), T1–T10 (the beginning and end of each session), T11 (after the last session), T30 (30 days after the last session) and T60 (60 days after the last session) | Numerical pain scale (0–10 cm) |

| Herman et al. [31] | Patients with acute (3–10 weeks duration) occupational LBP, i.e. work related LBP injury of musculoskeletal or fibromyalgic origin | TENS/CODETRON (Code IV, 200 Hz) applied 30 min before an exercise program n=29 Exercise program consisted: (hydrotherapy, mobility exercises, strengthening exercise and cardiovascular fitness) |

Sham TENS applied 30 min before an exercise program n=29 Same exercise program |

4 week program | 4 weeks | Visual analogue pain scale (0–100 mm) |

PEDro ratings for included trials.

| PEDro criterion | Bertalanffy et al. [13] | Herman et al. [31] | Lourenzi et al. [32] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Eligibility criteria | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. | Random allocation | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. | Concealed allocation | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4. | Baseline similarity | 1 | 1 | Unclear |

| 5. | Patient blinding | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. | Therapist blinding | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. | Assessor blinding | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. | >85% follow-up | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. | Intention to treat | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10. | Between group comparison | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11. | Point measures and measures of variability | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total score | 6 | 5 | 5 |

-

1=the trial complied with the PEDro item; 0=non-compliance. Operational definitions for each PEDro item are provided in the box. PEDro Criteria (de Morton [25], Macedo et al. [26], Maher et al. [24]). 1. Eligibility criteria were specified. 2. Subjects were randomly allocated to groups (in a crossover study, subjects were randomly allocated an order in which treatments were received). 3. Allocation was concealed. 4. The groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators. 5. There was blinding of all subjects. 6. There was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy. 7. There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome. 8. Measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups. 9. All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least one key outcome was analysed by “intention to treat”. 10. The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome. 11. The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one outcome.

The eligible studies evaluated treatment with TENS in various contexts and for varying durations:

~30 min treatment with TENS as a one-off treatment during emergency transport of patients to the hospital [13];

TENS administered directly before an exercise program (program duration 4 weeks) [31];

TENS administered twice a week over a course of 5-weeks [32].

All of the studies were rated as high risk of bias.

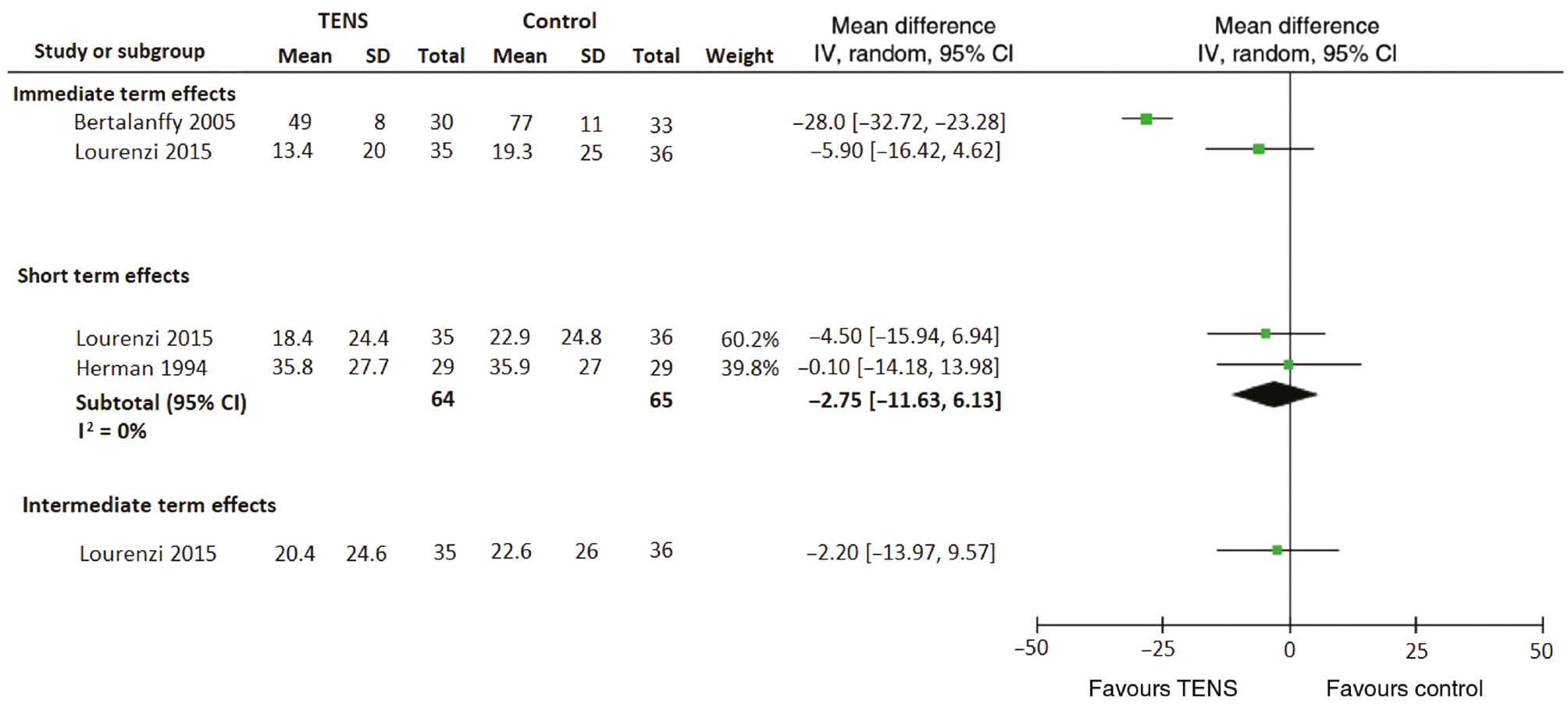

3.1 Pain

One study [13] provided low quality evidence (downgraded for imprecision, risk of bias) of immediate improvements in pain with ~30 min TENS treatment compared with sham TENS; MD −28.0 (CI −32.72, −23.28) in patients with moderate to severe acute LBP being transported to the hospital by paramedics. This is shown in Fig. 2. This effect size is just beneath our threshold for large improvements in pain. No longer term results were reported. Another study evaluating a course of TENS over 5 weeks [32] provided inconclusive evidence regarding the effect of TENS for acute LBP in the immediate term; MD −5.90 (−16.42, 4.62) (low quality evidence; downgraded for imprecision, risk of bias). Pooled effects from two low quality studies [31], [32] similarly provide inconclusive evidence regarding the effectiveness of a course of TENS (over 4–5 weeks) for the short term; MD −2.75 (CI −11.63, 6.13) (low quality evidence; downgraded for imprecision, risk of bias). For the intermediate term, one study [32] provided a lack of evidence of an effect of TENS vs. sham TENS; MD −2.20 (CI −13.97, 9.57) (low quality evidence; downgraded for imprecision, risk of bias).

Effects of TENS on pain. Pain is measured on a 0 (no pain) to 100 (maximum) scale. Effects are mean differences in outcome with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

3.2 Adverse events

There were limited data on adverse events. There were no adverse events outcomes reported in two of the studies [13], [32]. In one of the studies [31], an equal proportion of people in the active (2/29) and control (2/29) groups experienced an adverse event, however, the nature of these adverse events was not reported.

4 Discussion

4.1 Principal findings

There is insufficient evidence to support or dismiss the use of TENS for acute LBP. Currently there is low quality evidence that treatment with TENS (~30 min) provides immediate improvements in pain compared with sham TENS for patients with moderate to severe acute LBP being transported to hospital by paramedics. This improvement is just below our threshold for a large improvement in pain (>30 points on a 100-point pain scale). There is a lack of evidence of an effect of TENS over a course of 4–5 weeks in a clinical setting (low quality evidence).

4.2 Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of the study are the use of a comprehensive search strategy, use of a validated scale to measure risk of bias and double data extraction. A limitation of this review is that we only retrieved a few trials, none of which provided data on long term outcomes and there was limited data on safety. A limitation common to all three of the included studies was their small sample size and limitations in study design (all were rated as high risk of bias). None of the studies could truly guarantee patient, therapist and assessor blinding thereby introducing potential performance bias as individuals in the treatment arm would have been more likely to perceive an effect. Furthermore, two of the studies [31], [32] did not report adequate methods for concealed allocation, which may have resulted in selection bias, as particular patients may have been preferred over others for allocation to treatment. Another uncertainty is the unusual results reported in the one positive trial [13]. The study reported that after 30 min treatment with active TENS, mean pain scores almost halved, whereas pain scores for the placebo group increased slightly to 77. This is a very unusual pattern of results for a placebo controlled trial in this field. As such, we would caution readers to consider these findings carefully, as it is based on low quality evidence, and because further studies are needed to determine the true effectiveness of TENS for acute LBP.

4.3 Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

This review provides a comprehensive evaluation of TENS in acute LBP, taking into consideration clinical context and treatment duration. We have also included studies previously excluded in a Cochrane review of TENS for acute pain [33]. Previous systematic reviews evaluating TENS for LBP have focused on the treatment of chronic LBP and it is still inconclusive as a viable treatment option in this context [34], [14], [15], [16]. A 2009 review [19] described moderate effect of TENS for acute LBP, based on the pooled estimate from two studies [13], [31], however there was no quality of evidence assessment for this finding. We considered these studies [13], [31] to be sufficiently heterogeneous to challenge pooling (course of treatment in outpatient clinic vs. single treatment in acute care emergency setting, respectively). As such we presented the findings separately which has implications on the overall findings.

4.4 Implications for clinicians and policy makers

The current NICE guideline [17] advises against the use of TENS for LBP, however, it is unclear if this recommendation relates to acute or chronic LBP. The findings from our review are inconclusive, and support the need for larger and more rigorous trials to resolve this uncertainty. If the effects are truly as large as reported by Bertalanffy et al. [13], it is possible that TENS can be integrated in the care plan for patients with acute LBP being transported to hospital. This approach may also reduce the need for strong medications, e.g. opioid analgesics, upon arrival at the hospital or during emergency transport to the hospital. Evidence from more robust clinical trials are not only needed to establish efficacy and safety but also to inform consideration around cost to the individual, particularly as TENS devices are generally more costly than a standard packet of analgesic medicine. Cost effectiveness studies would therefore also be important, to ascertain whether this intervention is good value.

5 Conclusion

There is low quality evidence from one study that TENS provides immediate pain relief for patients with moderate to severe acute LBP being transported to hospital by paramedics. There is a lack of evidence of an effect of TENS when administered in more usual treatment contexts. As the findings come from only a few studies, there is a need to conduct larger trials across both ambulatory and primary care settings to resolve these conflicting results on the efficacy of TENS for acute LBP.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Chris Maher, Chris Lin, Adrian Traeger and Gustavo Machado hold research fellowships funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

-

Authors’ contributions

-

JB, JW, CAS were involved in study inception and design. JB, JW, SG, CAS were involved in the article search and data extraction. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Appendix

Summary of search strategy.

| 1 | Randomised study OR random allocation OR Radomi*ed controlled trial OR Random$ Control$ trial OR RCT OR REVIEW, ACADEMIC.pt. OR REVIEW, TUTORIAL.pt. OR META–ANALYSIS.pt. OR META–ANALYSIS.sh. OR systematic review$ OR systematic overview$ OR meta-analy$ or metaanaly$ or (meta analy$) |

| 2 | ANIMAL/ not HUMAN/ |

| 3 | 1 NOT 2 |

| 4 | Low back pain OR mechanical back pain OR lumbago OR acute low back pain or Low-back pain |

| 5 | TENS OR Transcutaneous electric Nerve stimulation OR analgesic cutaneous electrostimulation OR cutaneous electrostimulation, analgesic OR electric stimulation, transcutaneous OR electroanalgesia OR electrostimulation, analgesic cutaneous OR electrostimulation, transdermal OR nerve stimulation, transcutaneous OR inferential therapy OR inferential current OR Codetron OR transcutaneous electric* stimulation OR transcutaneous electric* nerve stimulation |

| 6 | 4 AND 5 |

| 7 | 3 AND 6 |

References

[1] Walker BF. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord 2000;13:205–17.10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD. Low back pain in Australian adults: the economic burden. Asia-Pacific J Public Health 2003;15:79–87.10.1177/101053950301500202Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, Williams G, Smith E, Vos T, Barendregt J, Murray C, Burstein R, Buchbinder R. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74.10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–30.10.7326/M16-2367Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Traeger A, Buchbinder R, Harris I, Maher C. Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in primary care. Can Med Assoc J 2017;189:E1386–95.10.1503/cmaj.170527Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin C-WC, Day RO, McLachlan AJ, Ferreira ML. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. Br Med J 2015;350:h1225.10.1136/bmj.h1225Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Day RO, Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1269–78.10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210597Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG, Williams KA, Day R, McLachlan AJ. Efficacy, tolerability, and dose-dependent effects of opioid analgesics for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:958–68.10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1251Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Deyo RA, Walsh NE, Martin DC, Schoenfeld LS, Ramamurthy S. A controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) and exercise for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1627–34.10.1056/NEJM199006073222303Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] American Physical Therapy Association. American Physical Therapy Association Anthology, vol. 2. American Physical Therapy Association, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Barr JO. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for pain management. In: Nelson RM, Hayes KW, Currier DP, editors. Clinical Electrotherapy. 3rd ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1999:291–354.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Sluka KA, Walsh D. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation basic science mechanisms and clinical effectiveness. J Pain 2003;4:109–21.10.1054/jpai.2003.434Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Bertalanffy A, Kober A, Bertalanffy P, Gustorff B, Gore O, Adel S, Hoerauf K. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation reduces acute low back pain during emergency transport. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:607–11.10.1111/j.1553-2712.2005.tb00914.xSearch in Google Scholar

[14] Jauregui JJ, Cherian JJ, Gwam CU, Chughtai M, Mistry JB, Elmallah RK, Harwin SF, Bhave A, Mont MA. A meta-analysis of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for chronic low back pain. Surg Technol Int 2016;28:296–302.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Resende L, Merriwether E, Rampazo EP, Dailey D, Embree J, Deberg J, Liebano RE, Sluka KA. Meta-analysis of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for relief of spinal pain. Eur J Pain 2018;22:663–78.10.1002/ejp.1168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Wu LC, Weng PW, Chen CH, Huang YY, Tsuang YH, Chiang CJ. Literature review and meta-analysis of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in treating chronic back pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018;43:425–33.10.1097/AAP.0000000000000740Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Low Back pain and sciatica in over 16’s: assessment and management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. Medycyna Pracy 2011;63:295–302.Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed: Jun 2017.10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Australian Physiotherapy Association. Choosing Wisely Australia. Available at: https://www.physiotherapy.asn.au/APAWCM/Advocacy/Campaigns/Choosing_Wisely.aspx. Accessed: Dec 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Machado LA, Kamper SJ, Herbert RD, Maher CG, McAuley JH. Analgesic effects of treatments for non-specific low back pain: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:520–7.10.1093/rheumatology/ken470Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.2.0. Cochrane Collaboration, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, Fainsinger R, Aass N, Kaasa S. European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC). Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:1073–93.10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Kerns RD, Ader DN, Brandenburg N, Burke LB, Cella D, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dimitrova R, Dionne R, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Katz NP, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21.10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, Waddell G, Croft P, Von Korff M, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine (PhilaPa1976) 2008;33:90–4.10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2003;83:713–21.10.1093/ptj/83.8.713Search in Google Scholar

[25] de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother 2009;55:129–33.10.1016/S0004-9514(09)70043-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Macedo LG, Elkins MR, Maher CG, Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Sherrington C. There was evidence of convergent and construct validity of Physiotherapy Evidence Database quality scale for physiotherapy trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:920–5.10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.10.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Hancock M, Oliveira VC, McLachlan AJ, Koes B. Drugs for relief of pain in patients with sciatica: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 2012;344:e497.10.1136/bmj.e497Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, Hancock M, Oliveira VC, McLachlan AJ, Koes B, Ferreira PH. Epidural corticosteroid injections in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:865–77.10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00564Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J 1997;315:629–34.10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Herman E, Williams R, Stratford P, Fargas-Babjak A, Trott MA. A randomized controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (CODETRON) to determine its benefits in a rehabilitation program for acute occupational low back pain. Spine 1994;19:561–8.10.1097/00007632-199403000-00012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Lourenzi VDGCM, Jones A, Lourenzi FM, Jennings F, Natour J. THU0638-HPR effectiveness of the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in pain control of patients with acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1322.10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-eular.4989Search in Google Scholar

[33] Johnson MI, Paley CA, Howe TE, Sluka KA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for acute pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;CD006142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006142.pub3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Khadilkar A, Odebiyi DO, Brosseau L, Wells GA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) versus placebo for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;4:CD003008.10.1002/14651858.CD003008.pub3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2019 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Systemic inflammation firmly documented in chronic pain patients by measurement of increased levels of many of 92 inflammation-related proteins in blood – normalizing as the pain condition improves with CBT-based multimodal rehabilitation at Uppsala Pain Center

- Systematic review

- Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients and effects of a multimodal pain rehabilitation program

- Chronic Widespread Pain in a tertiary pain clinic: classification overlap and use of a patient generated quality of life instrument

- Symptom reduction and improved function in chronic CRPS type 1 after 12-week integrated, interdisciplinary therapy

- Chronic pain after bilateral thoracotomy in lung transplant patients

- Reference values of conditioned pain modulation

- Risk severity moderated effectiveness of pain treatment in adolescents

- Pain assessment in hospitalized spinal cord injured patients – a controlled cross-sectional study

- Risk-based targeting of adjuvant pregabalin treatment in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled trial

- The impact of comorbid pain and depression in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey

- Observational study

- The utility/futility of medications for neuropathic pain – an observational study

- Posttraumatic stress and autobiographical memory in chronic pain patients

- Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017

- Characteristics of women with chronic pelvic pain referred to physiotherapy treatment after multidisciplinary assessment: a cross-sectional study

- The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1,712 patients

- Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study

- Original experimental

- Interpretation bias in the face of pain: a discriminatory fear conditioning approach

- Taboo gesticulations as a response to pain

- Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment

- Muscle stretching – the potential role of endogenous pain inhibitory modulation on stretch tolerance

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical registries are essential tools for ensuring quality and improving outcomes in pain medicine

- Fibromyalgia in biblical times

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Systemic inflammation firmly documented in chronic pain patients by measurement of increased levels of many of 92 inflammation-related proteins in blood – normalizing as the pain condition improves with CBT-based multimodal rehabilitation at Uppsala Pain Center

- Systematic review

- Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for acute low back pain: systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Detection of systemic inflammation in severely impaired chronic pain patients and effects of a multimodal pain rehabilitation program

- Chronic Widespread Pain in a tertiary pain clinic: classification overlap and use of a patient generated quality of life instrument

- Symptom reduction and improved function in chronic CRPS type 1 after 12-week integrated, interdisciplinary therapy

- Chronic pain after bilateral thoracotomy in lung transplant patients

- Reference values of conditioned pain modulation

- Risk severity moderated effectiveness of pain treatment in adolescents

- Pain assessment in hospitalized spinal cord injured patients – a controlled cross-sectional study

- Risk-based targeting of adjuvant pregabalin treatment in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, controlled trial

- The impact of comorbid pain and depression in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey

- Observational study

- The utility/futility of medications for neuropathic pain – an observational study

- Posttraumatic stress and autobiographical memory in chronic pain patients

- Prescribed opioid analgesic use developments in three Nordic countries, 2006–2017

- Characteristics of women with chronic pelvic pain referred to physiotherapy treatment after multidisciplinary assessment: a cross-sectional study

- The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1,712 patients

- Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study

- Original experimental

- Interpretation bias in the face of pain: a discriminatory fear conditioning approach

- Taboo gesticulations as a response to pain

- Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment

- Muscle stretching – the potential role of endogenous pain inhibitory modulation on stretch tolerance

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical registries are essential tools for ensuring quality and improving outcomes in pain medicine

- Fibromyalgia in biblical times