Abstract

Against the backdrop of low oil prices, oil-macro-financial linkages in Saudi Arabia are analyzed by applying panel econometric frameworks (multivariate and vector autoregression) to macro- and micro-level data for 9 banks spanning 1999–2014. Lower growth of oil prices and nonoil private sector output leads dampen credit and deposit growth and lift nonperforming loan ratios. Positive feedback loops within bank balance sheets in turn dampen economic activity. U.S. interest rates are not found to be a key determinant. The banking system remains strong at present, but policy makers should monitor its health with the important macro-financial feedback loops in mind.

Appendix

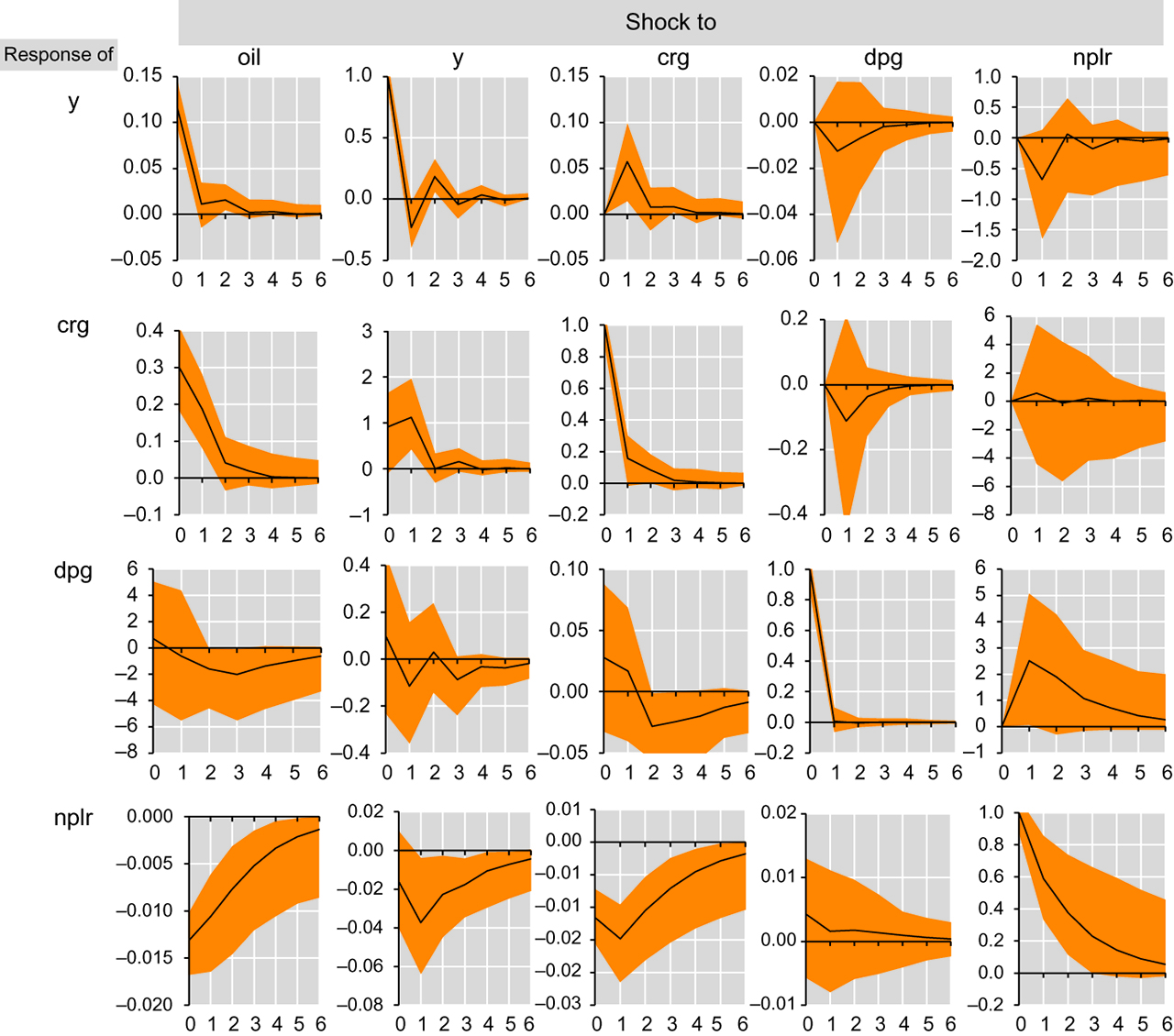

Oil-macro-financial feedback effects, pvar 2.

Note: Oil is real oil price growth, y is real nonoil private sector GDP growth, crg is real credit growth, dpg is real deposit growth, nplr is NPL ratio.

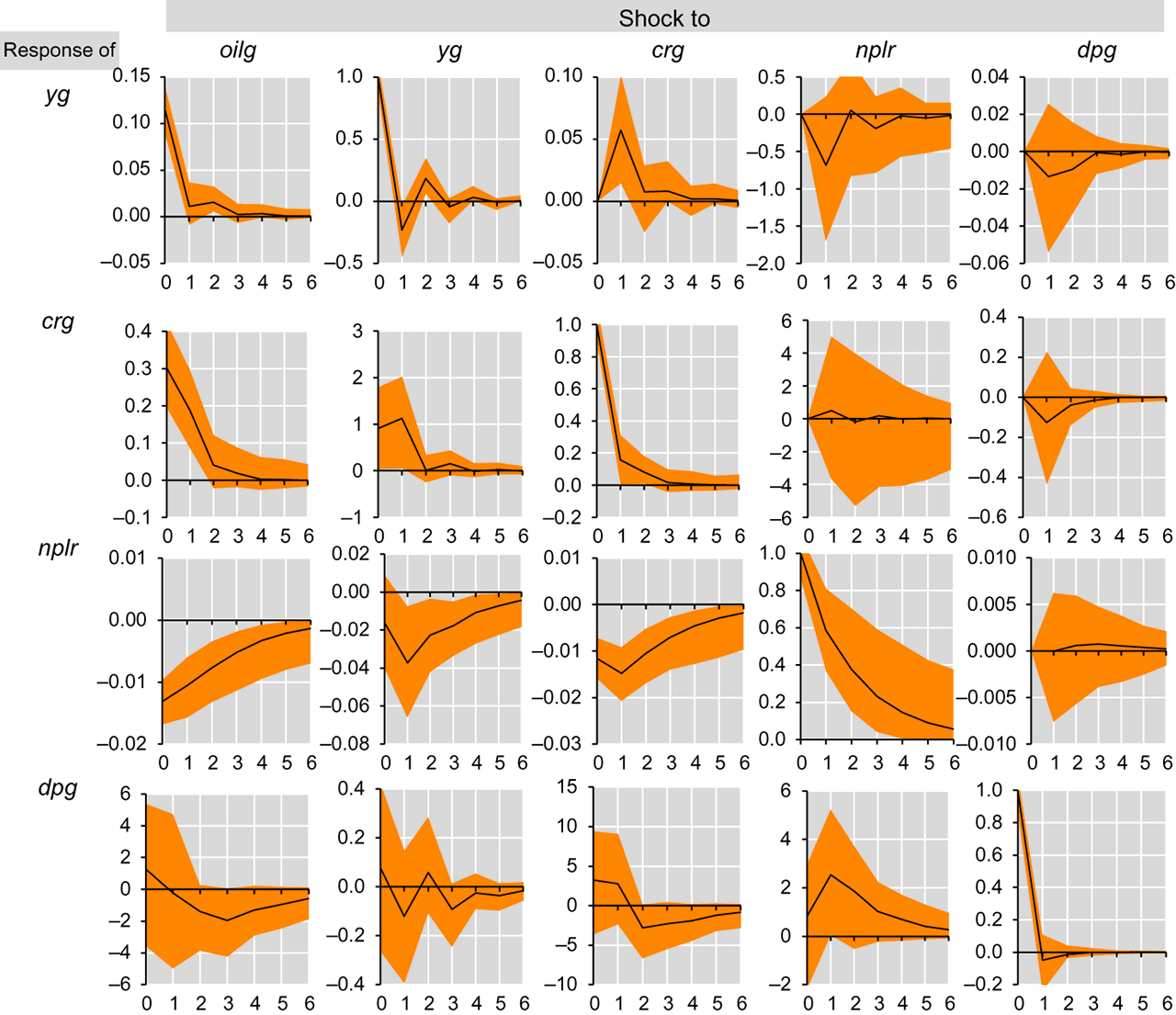

Oil-macro-financial feedback effects, pvar 3.

Note: oilg is real oil price growth, yg is real nonoil private sector GDP growth, crg is real credit growth, nplr is NPL ratio, dpg is real deposit growth.

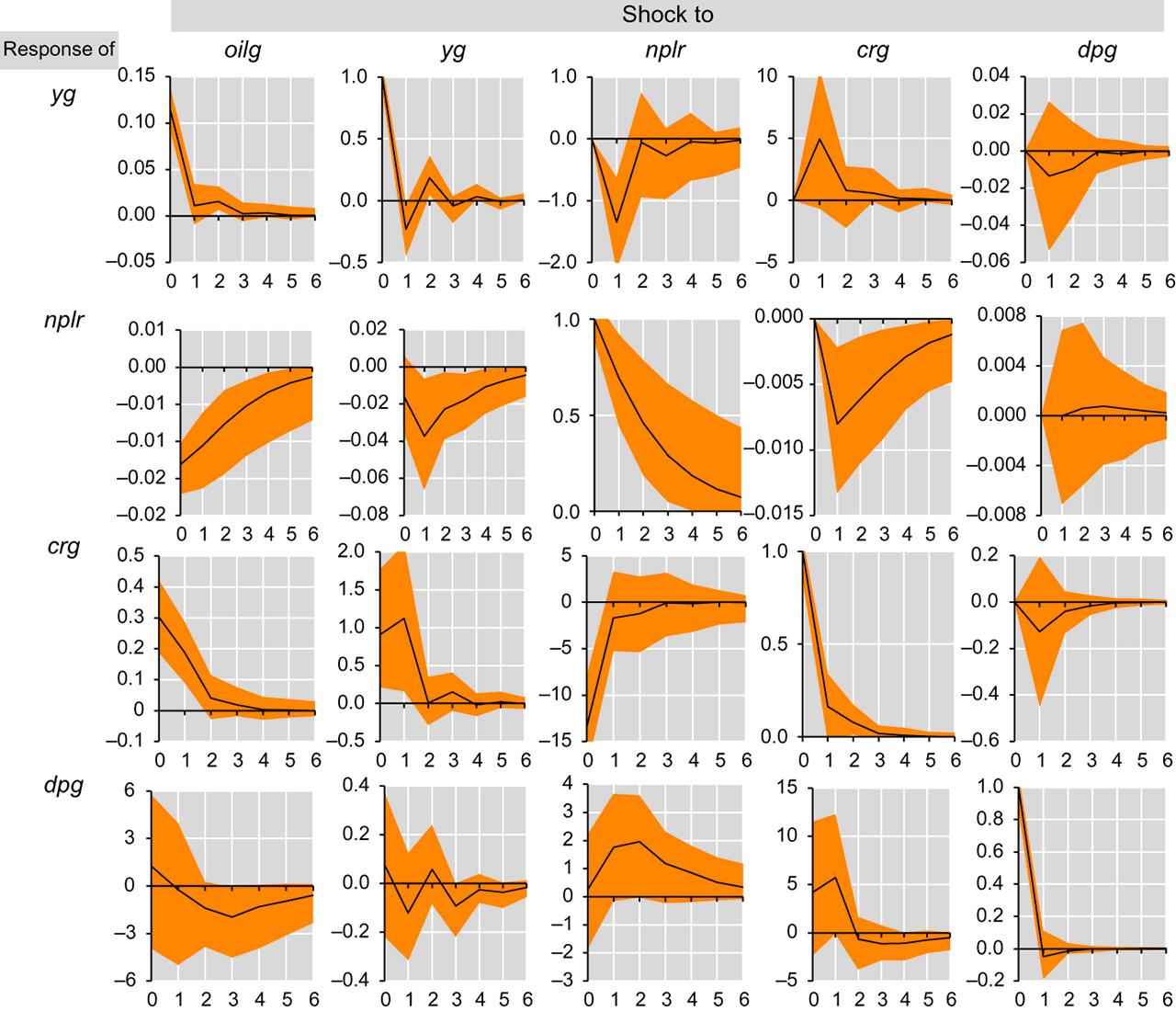

Oil-macro-financial feedback effects, pvar 4.

Note: olig is real oil price growth, yg is real nonoil private sector GDP growth, nplr is NPL ratio, crg real credit growth, dpg is real deposit growth.

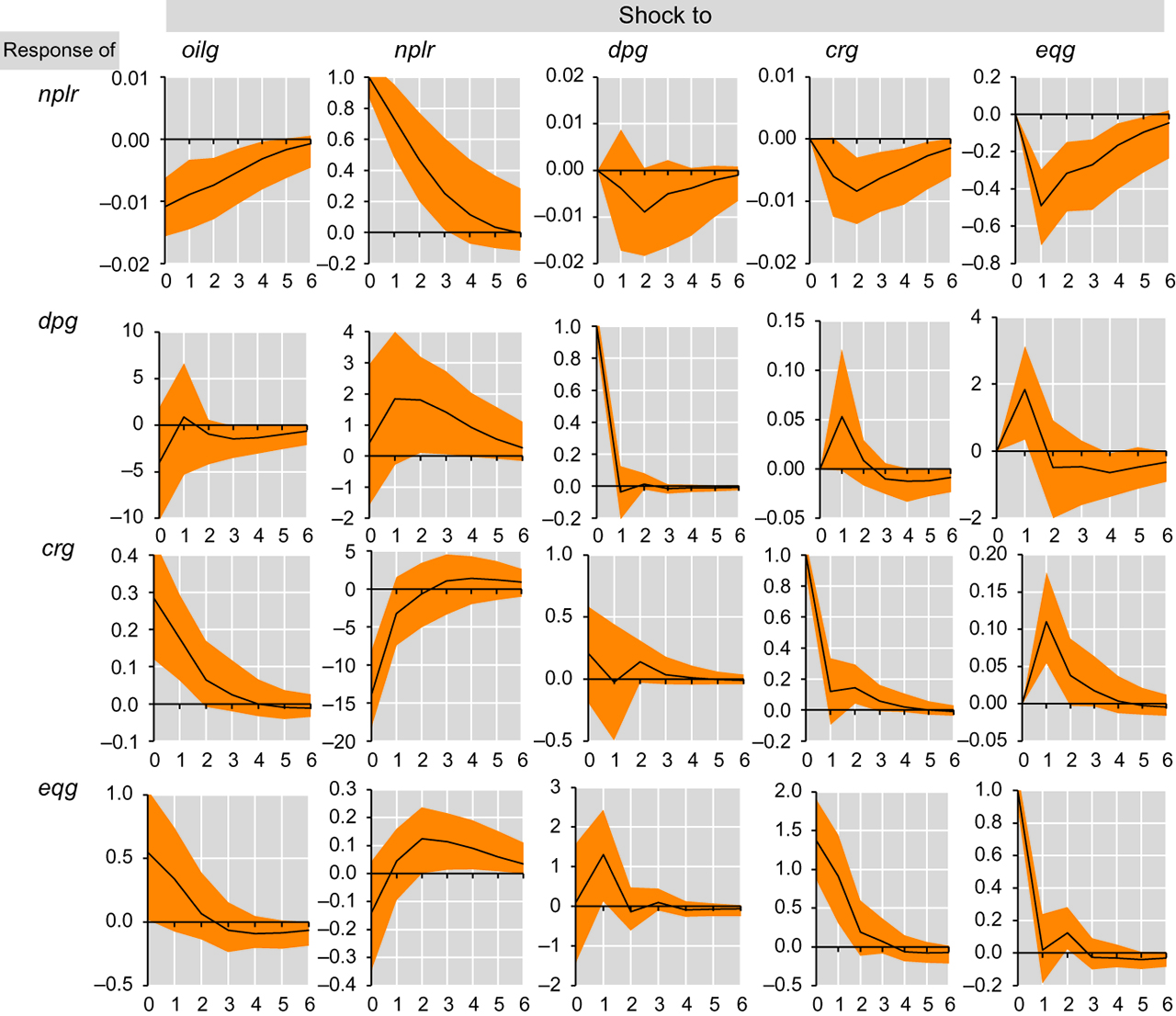

Oil-macro-financial feedback effects, pvar 5.

Note: olig is real oil price growth, nplr is NPL ratio, dpg is real deposit growth, crg is real credit growth, eqg is real equity price growth.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management. Earlier versions of this paper benefitted from extensive discussion with the Executive Directors and Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency staff. The author is grateful to Tim Callen, Javier Hamann, Phakawa Jeasakul, Padamja Khandelwal, Ananthakrishnan Prasad, seminar participants at the IMF and the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency. The author would like to also think the referees and the editor of the journal for useful comments. Any errors are the author’s responsibility.

References

Arellano, M., and O. Bover. 1995. “Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models.” Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 29–51.10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-DSuche in Google Scholar

Beck, R., P. Jakubik, and A. Piloiu. (2013).Non-performing Loans what Matters in Addition to the Economic Cycle? ECB Working Paper 1515.10.2139/ssrn.2214971Suche in Google Scholar

Blundell, R., and S. Bond. 1998. “Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models.” Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–143.10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8Suche in Google Scholar

Cho, S. 2006. “Evidence of a Stock Market Wealth Effect Using Household Level Data.” Economic Letters 90: 402–406.10.1016/j.econlet.2005.09.006Suche in Google Scholar

De Bock, R., and A. Demyanets. (2012).Bank Asset Quality in Emerging Markets: Determinants and Spillovers IMF Working Paper 12/71.10.5089/9781475502237.001Suche in Google Scholar

Espinoza, R., and A. Prasad. (2010).Nonperforming Loans in the GCC Banking Systems and their Macroeconomic Effects IMF Working Paper 10/224.10.5089/9781455208890.001Suche in Google Scholar

Funke, N. 2004. “Is There a Stock Market Wealth Effect in Emerging Markets?” Economic Letters 83: 417–421.10.1016/j.econlet.2003.12.002Suche in Google Scholar

Hesse, H. Stock Market Wealth Effects in Emerging Market Countries 2008 VOX blog: http://www.voxeu.org/article/stock-market-wealth-effects-emerging-market-countries.Suche in Google Scholar

Klein, N. (2013).Non-Performing Loans in CESEE: Determinants and Impact on Macroeconomic Performance IMF Working Paper 13/72.10.5089/9781484318522.001Suche in Google Scholar

Love, I., and R.T. Ariss. 2014. “Macro-Financial Linkages in Egypt: A Panel Analysis of Economic Shocks and Loan Portfolio Quality.” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 28 (C): 158–181.10.1016/j.intfin.2013.10.006Suche in Google Scholar

Love, I., and L. Zicchino. 2006. “Financial Development and Dynamic Investment Behavior: Evidence from Panel Vector Autoregression.” The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 46: 190–210.10.1016/j.qref.2005.11.007Suche in Google Scholar

Marcucci, J., and M. Quagliariello. 2008. “Is Bank Portfolio Riskiness Procyclical? Evidence from Italy Using a Vector Autoregression.” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 18: 46–63.10.1016/j.intfin.2006.05.002Suche in Google Scholar

Nkusu, M. (2011).Nonperforming Loans and Macrofinancial Vulnerabilities in Advanced Economies IMF Working Paper 11/161.10.5089/9781455297740.001Suche in Google Scholar

Peltonen, T.A., R.M. Sousa, and I.S. Vensteenskiste. 2012. “Wealth Effects in Emerging Market Economies.” International Review of Economics and Finance 24: 155–166.10.1016/j.iref.2012.01.006Suche in Google Scholar

Roodman, D 2009. “A Note on the Theme of Too Many Instruments.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 71 (1): 135–158.10.1111/j.1468-0084.2008.00542.xSuche in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- An Empirical Investigation of Oil-Macro-financial Linkages in Saudi Arabia

- Political Instability and Economic Growth in Egypt

- Iran’s Inflationary Experience: Demand Pressures, External Shocks, and Supply Constraints

- Analysis of Food Imports in a Highly Import Dependent Economy

Artikel in diesem Heft

- An Empirical Investigation of Oil-Macro-financial Linkages in Saudi Arabia

- Political Instability and Economic Growth in Egypt

- Iran’s Inflationary Experience: Demand Pressures, External Shocks, and Supply Constraints

- Analysis of Food Imports in a Highly Import Dependent Economy