Abstract

This experimental paper provides evidence on the incidence of different third-party punishment institutions in the context of a game designed to represent simplified versions of specific, real-life situations. We begin with a benchmark scenario (which we will call “Baseline”), that involves the possibility of altruistic third-party punishment after playing a taking game. The “vertical control” treatment adds a second possible punisher who can confirm or overturn the initial decision. The “giving reasons” treatment requires the third party to provide reasons to motivate her/his choice. A fourth treatment combines both instruments. Thus, we manipulate our interest variables (“vertical control” and “giving reasons”) both one at a time and, eventually, in a combined format. The main result is that both instruments have a significant positive impact on the incidence of punishment. In contrast, the hybrid scenario does not further increase the frequency of punishment, seemingly due to a “mis-use” of the “giving reasons” requirement by arguing vis-à-vis the second instance to uphold the first-instance, non-punishment decision.

1 Introduction: Institutional Background

This article is an experimental paper in law and economics. It uses incentivized experiments to address a genuine institutional/legal topic: whether (and, if yes, how exactly) alternative procedural regimes entice different levels of costly punishment.

The aim of this paper is threefold. First, the paper provides, in its initial baseline analysis, a very brief contribution to the role of law enforcement by means of “altruistic third party punishment” – namely, by providing an independent observer with the option for costly punishment regarding an underlying “stealing scenario”. In its main second part, the paper contributes to comparative institutionalism by comparing the incidence of this altruistic, third party punishment in the aforementioned “institution-free” baseline punishment-scenario with different institutional (“procedural”) environments. We begin this comparative analysis, thereby building on our previous work, by studying the punishment effects that stem from (i) the introduction of a second (vertical) instance that has the last word regarding punishment, possibly overriding the first instance decision. We then turn to an alternative institutional setting – namely, (ii) the introduction of an obligation for the (potential) punisher to provide justification for her/his decision. The pertinent research question is whether such an obligation to reflect on one’s punishment decision and provide written reasons increases or decreases costly, third party (altruistic) punishment. We proceed by (iii) merging the two aforementioned variants, such that the “first instance” punisher must justify her/his decision, which is subsequently subject to a (possibly overriding) reassessment by the second instance. Third, the paper addresses the influence of the aforementioned various enforcement institutions on the underlying “stealing behaviour” – namely, on their effects to reduce the “incidence of crime”. Both the experimental analysis of a giving-reasons-requirement and its combination with an “appeals-setting” on enforcement levels have not been investigated in the previous literature.

On a more technical level, the paper is “procedural”. There is (and has been) wide consensus that ideal procedures shall be expedient, inexpensive, and just (=fair[1]). A simultaneous accomplishment of these goals, however, is a difficult task, because the aforementioned goals are partially conflicting.[2] Because of this trade-off, there is no such thing as the single best procedure. Procedural rules are always a compromise seeking to balance the accomplishment of these different goals in a socially acceptable manner,[3] whereby some goals may be prioritized over others depending on the situation at hand. In that sense, there are many different (procedural) paths to Rome. In terms of law enforcement, concepts of fairness appear to require that a committed wrong shall not go unpunished. The institutional question, however, is whether this enforcement-task can be best accomplished in an institution-free world by introducing a second vertical instance, a giving-reason-requirement, or a combination of the two. Although these alternative settings obviously differ in terms of cost (with the usage of a second instance naturally increasing costs in relation to a simple giving-reasons-requirement) and the time necessary to reach a final decision, the question is whether they accomplish similar or different enforcement results (in terms of the incidence and amount of punishment).

Historically, the picture is complex. In ancient times, broadly conceived dispute resolution (including “criminal enforcement”) was primarily done within the community and often even in front of the entire community, by specific community members (often by wise elderly men). In such a world, there is no need for a second instance because, on the one hand, all conceivable evidence is already being collected by the decision makers in the course of their basic decision and, on the other hand, there are no other, potentially better decision makers available who could constitute a second instance in a meaningful sense. Whereas, in such a world, the need for reasoned decisions is reduced, early tribal forms of restorative justice did encompass a pertinent communication element in the ultimate “settlement decision”. In turn, giving reasons for a verdict was obsolete to the extent that the procedural system relied on formalistic types of proof (say, in “ordeals”, where the result of the ordeal already decides the trial).[4]

Still, in more modern times, two fundamental institutional instruments have emerged with the specific potential to improve judicial decision making – namely, the provision of a second instance (“vertical control”) and a requirement to motivate one’s decision (“giving reasons”).[5] The paper analyzes the effects of these instruments both separately and jointly (i.e. in a procedural world that combines a giving reasons requirement for the first instance with a second instance) in their potential to increase the incidence of costly punishment.

Vertical control is essentially provided by allowing for an appeal against the first-instance-decision.[6] The introduction of any such remedy serves a twofold goal. First, appeals represent an instrument designed to check and possibly improve the decision by the first instance by correcting conceivable errors.[7] Second, the institution of appellate review aims as such to improve the quality of first-instance judicial decision making: the mere possibility of such an appeal casts a shadow on the first instance and provides a powerful incentive for the decision maker (i.e. the trial judge) to render a decision such that it will not be overturned. In substance, this means that the first instance court will orient itself towards the presumed position by the higher court on this question – which is generally a good thing.[8] , [9]

A second basic procedural feature, a “giving reasons” requirement for judicial decisions, is considered a fundamental aspect of procedural fairness and decision making under the rule of law.[10] Requiring the decision maker to motivate her/his decision is a tool to rationalize the decision and improve its quality.[11]

In this paper, we assess the potential of the two aforementioned “institutional levers” to affect legal decision making (= punishment decisions) from an empirical, namely experimental, viewpoint. To the best of our knowledge, a comparable experimental study has not yet been undertaken. There is, thus far, no systematic study examining the impact of “giving reasons” on legal decision making as such, neither regarding the impact on the decision maker her/himself (compared with no reason being required), nor on the way in which a “second instance” views a reasoned versus non-reasoned decision. Our experiments aim to provide a first view on this set of issues through the lens of costly punishment.[12]

Whereas the paper analyses – with the focus on “giving reasons” and vertical control – the effects of various procedural settings on punishment and law enforcement (and on the incidence of the underlying “unwanted” behaviour), it does not investigate other relevant procedural issues. In our experiments, there is no ambiguity regarding the underlying deed; the relevant facts (stealing vs non-stealing) are evident.[13] As we leave out questions of fact-finding, we also do not study judicial effort in terms of concerns for accuracy.[14] What we are interested in, however, is the punishment-decision of the “judge(s)” in the light of the different institutional environments and the therein embedded incentives. This paper is also not a study on the incentives for bringing an appeal.[15] In fact, the appeal is “automatic”. In the vertical treatment, each first instance punishment decision is subject to review by the second instance decision maker without a pertinent initiative or action by a player being necessary or even possible to trigger this “vertical control”.

Our aim is to understand whether one of these two mechanisms works better than the other for “enforcement purposes” (in terms of incidence of punishment) as well as whether a combination of the two is preferable. We believe these are relevant questions for at least two reasons.

First, the implementation of these mechanisms entails some costs, both monetary and in terms of time (i.e. both mechanisms increase the monetary cost of a trial and the time required to resolve a dispute). Attempting to understand whether one of these two mechanisms (or a combination of the two) entice higher levels of punishment may be a starting point for a more sophisticated cost/benefit analysis. Second, the experimental analysis allows for the identification of possible shortfalls in enforcement that may result from undesired counter-effects in a “combined scenario”.

Moreover, the use of experiments allows us to perfectly disentangle the effects of the two mechanism and, at the same time, analyse them jointly. The experimental methodology appears to be the most suitable tool to answer our research questions, since it allows us to control the institutional environment – something that is nearly impossible in a real-life context.

Experiments have been widely used to highlight different scenarios and aspects of (third-party) punishment. Starting with the pioneering works by Fehr and Gäechter (2000, 2002) on public good games, the third-party punishment game developed by Fehr and Fischbacher (2004), allowing a third party to sanction a dictator if s/he considers the allocation of the pot unfair, was another milestone of the literature. A refinement of this experiment is the “taking game” (or “gangster game”), initially developed in 1998 by (see Flage 2024 for a meta- analysis), in which the dictator is not the owner of the endowment but may take the money from the other player. Lewisch et al. (2015) combined the taking game with the third-party punishment game. This is the basis of our experiment.

Section 2 describes the experimental design and procedure. Section 3 reports the pertinent payoff-structure. Section 4 defines the expected results, whereas Section 5 focuses on data analysis. Section 6 summarises our findings and provides a conclusion.

2 Experimental Design and Procedure

In our experiment, subjects participate in a game designed to represent a simplified version of a specific, real-life situation, namely costly punishment under different institutional environments. Beginning with a benchmark scenario (which we will call “Baseline”), we manipulate our interest variables (“top-down control” and “giving reasons”) – first, one at a time and, eventually, in a combined format. Thus, the resulting design consists of four treatments: baseline (= ordinary third-party punishment), vertical control, giving reasons, and vertical control with giving reasons. Each of these treatments is implemented with different groups of subjects.[16]

This is a laboratory experiment in which decisions are recorded by the computer and anonymity is guaranteed even when the experimental session ends.[17] Participants enter the laboratory and take a seat in front of a computer. They are immediately asked to switch off their mobile phones and refrain from talking to other participants. Participants then read the experiment instructions on their computer screen, while an experimenter simultaneously reads them out loud. A sheet of paper with all information concerning the game is also handed out.

In the B aseline T reatment (BT), a basic, 3-person punishment scenario is implemented. Each session involves n A-players, n B-players and n*3 C-players.[18] Each player is assigned just one role for the whole session. In each session, players participate in 3 rounds. At the beginning of each round, all players receive their initial endowment (200 tokens each). The first round consists of two stages. In the first stage, A-player and B-player are paired and participate in a Theft Game, in which A-player is offered the option to take away (“steal”) 50 tokens of B-player’s initial endowment. In the second stage, 1/3 of C-players are randomly selected and assigned to a team who played the theft game in the first stage. Each selected C-player must decide whether she/he wants to spend 10 tokens of the endowment to punish A-player[19] in the case of stealing (i.e. ex ante).[20] Punishment may be lenient (A-player’s endowment is reduced by 100 tokens) or harsh (A-player’s endowment is reduced by 150 tokens). We introduce these two levels of punishment since they represent two ways of sanctioning the theft. In the lenient case (100 tokens) A-player’s payoff when s/he steals and the payoff of B are equal. In this case, C-player restores the initial situation of equality between A-player and B-player. In the harsh case (150 tokens), A-player becomes poorer than B-player. Thus, C-player presumably believes that A-player deserves to be in lower position than B-player.

C-players who are not selected to participate in the second stage are asked to wait. The second round is exactly the same as the first one, except that a different 1/3 of C-players are selected to make their choice in the second stage. In the third round, A-players and B-players play again, while the remaining 1/3 of C-players participate in the second stage. This implies that A-players and B-players play the game 3 times, whereas each C-player makes her/his choice only once. Even if A-players and B-players play for all the rounds, no feedback is provided until the end of the experimental session. This holds for all treatments.

The BT represents our benchmark scenario. In fact, it represents a standard setting (of so-called “third party altruistic punishment”) that has been frequently examined in experimental studies. Obviously, a “social conflict” emerges if A-player takes (“steals”) money from B-player. Whereas B-player is unable to react, the neutral third party, the observer C-player, has the opportunity to intervene and punish the A-player. This punishment option is costly for the punisher in that, following a standard format, the C-player may “purchase”, by investing some of her/his own endowment, monetary deductions from A-player’s endowment. The punishment deduction from the A-player is a genuine punishment, i.e. it goes to the experimenter and not the punishing third party. The punishment/non-punishment decision by the C-player is the end-step of this social conflict. In some meaningful sense, it terminates the conflict that was originally sparked by A-player’s “theft”. Since the parties are aware of C-player’s punishment option, decisions by the A-player to take money from the B-player are always done in light of C-player’s punishment options and the respective expectations.[21]

In the other three treatments, we introduce “second-instance control” and “giving reasons”, both separately and jointly, in order to study the influence of these institutional tools on conflict resolution and conflict avoidance.

The V ertical C ontrol T reatment (VCT) is an extension of the baseline model with an “automatic” second-instance control competent of superseding the first-instance punishment decision. The D-player is informed about the underlying decision by C-player.[22] Technically, s/he has to confirm or not confirm C-player’s choice. In the case of no confirmation, s/he can correct C-player’s choice by selecting one of the other two options available. For example, if C-player decides not to punish the A-player in the case of theft and the D-player does not confirm this choice, s/he must impose a punishment decision and provide a final sentence by choosing between the lenient and harsher sanction. If, say, the C-player punishes but the D-player disagrees as to the harshness of the penalty, s/he may only alter the penalty. Each session involves n A-players, n B-players, n*3 C-players, and n D-players. Again, in each session players participate in 3 rounds. At the beginning of each round, all players receive their initial endowment (200 tokens each). Each round consists of three stages. The first two stages are the same as in the BT. However, in the third stage, the “second instance” comes into play as a new D-player. Each D-player is assigned to a team (A-player, B-player and C-player) and takes a fresh decision on whether or not – and, if yes, to what degree (lenient/harsh) – to punish the A-player. D-player’s punishment decision amounts to a confirmation or a correction of the C-player’s decision (to punish or not to punish). Mirroring the real-life situation that “confirmation” of a decision is easier than “overturning” it, only the decision to supersede the C-player’s decision is costly for the D-player. The decision to overrule the C-player’s punishment decision comes at a cost of 10 tokens for the D-player. Since the decision by the D-player marks the final step in the entire interaction, it ultimately determines the outcomes for both the players and the first instance punisher in the underlying scenario. D-player’s decision[23] directly determines A-player’s ultimate payoff (meaning that the punishment decision of the first instance is set aside by the appeals decision). Even if the C-player had not punished the A-player, a possible punishment decision by the D-player will lead to A-player’s punishment.[24] Likewise, if the A-player was punished by the C-player, but D-player does not punish the A-player, the A-player receives her/his initial payoff (without the punishment deduction). The appellate decision (realistically) also affects the “first-instance-punisher”, the C-player, in the sense that modifying decisions by the instance (D-player) lead to a reduction of 20 tokens in C-player’s payoff, whereas confirming decisions leave the C-player’s payoff unchanged.[25] The second round is exactly the same as the first one, with the exception that another 1/3 of C-players are selected to make their choices in the second stage. In the third round, the remaining 1/3 of C-players participate in the second stage. In the VCT, A-players, B-players, and D-players play the game 3 times, whereas each C-player makes her/his choices only once.

The G iving R easons T reatment (GRT) follows almost exactly the set-up of the BT, with the – however crucial – difference that now, C-players must write down the reason for her/his choice.[26] This reason is not communicated to players A and B in the group to avoid “words-against-fists-substitution” – i.e. C-players punish by (costless) harsh words, while avoiding costly monetary punishment.[27] However, A-player and B-player are informed that they are in a scenario in which the potential punisher C-player must motivate her/his punishment decision. The C-player, of course, also knows before making her/his choice that she/he will have to justify her/his decision.

In the “giving reasons” scenario, the fulfillment of this mandatory requirement (which applies to both punishment and non-punishment decisions) does not involve additional pecuniary costs.

The V ertical Control G iving R easons T reatment (VGRT) merges the two aforementioned procedural worlds, namely the giving-reason requirement with the introduction of a “second instance”. This scenario, therefore, matches the VCT, with the notable difference that now each C-player (i.e. the “first instance”) must write down the reasons of her/his choice.[28] This reasoned decision is communicated to the assigned D-player before she/he makes a choice. As in the GR, the C-player is aware of the requirement to give reasons prior to making her/his choice and also that the reasons will be communicated to the D-player. A-players and B-players are again not informed about the reasons given by the C-player; however, they know that they are in a scenario in which the C-player must motivate her/his decision and that the D-player will be informed about these reasons before making her/his own (final) decision.

At the end of the each experimental session, after filling out a socio-demographic questionnaire, subjects receive their payments in Euro.[29] Participants are paid according to their role and decisions. The final payment is the sum of the payments received in each round. This point is clear from the beginning of the experimental session. The average duration for each session is 45 min. The average payment is 14 €.

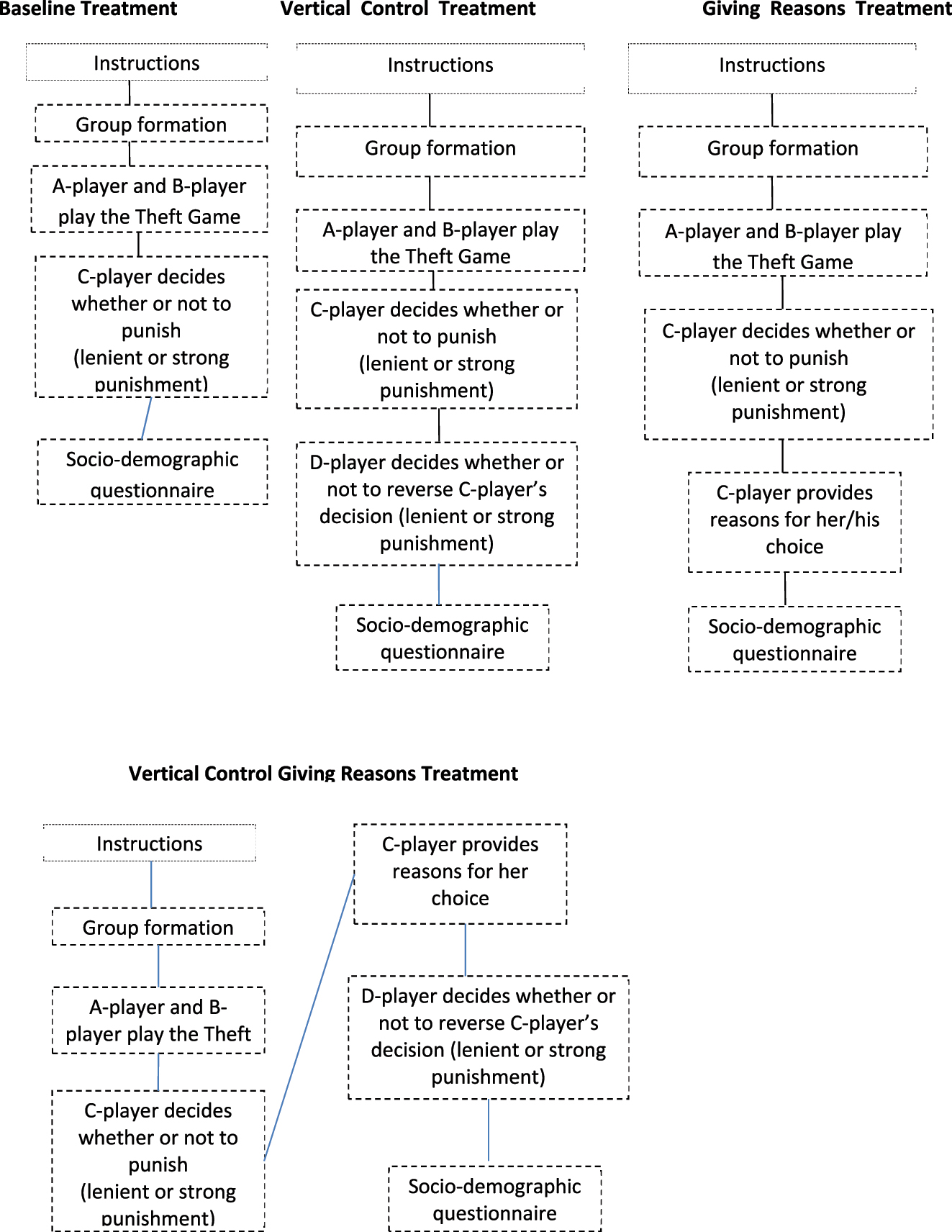

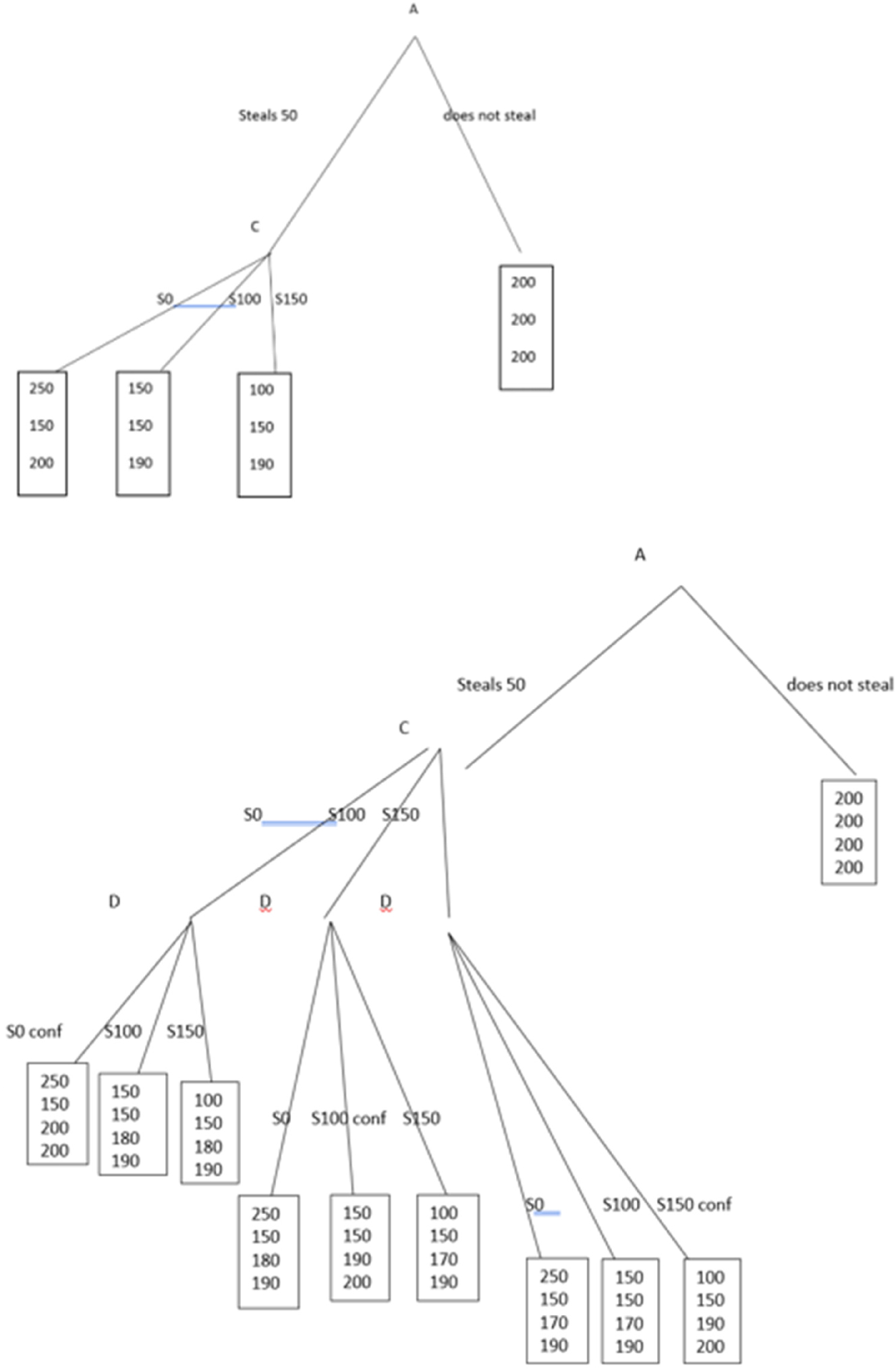

Figure 1 and Table 1 summarize the experimental design. Figures 2 and 3 report the trees of the games.

3 Payoff

First, regarding the BT and the GRT: if A-player does not take money from B-player, the final payoff is the same for each player and is equal to the initial endowment of 200 tokens each.

If A-player takes (“steals”) the 50 tokens from B-player, A-player can obviously enrich herself/himself by the amount taken from B-player. Hence, the payoffs are as follows:

Where:

E = 200 tokens is the endowment each player is given at the beginning of the session.

T B = 50 are the tokens that the A-player can steal from the B-player in the first stage.

C = 10 is the cost that the C-player bears if he/she sanctions the A-player. The cost for punishment is a flat fee; therefore, it does not differ according to the severity of the punishment.

SC is the level of sanction that the C-player imposes on A-player. It may be equal to 0 (if the C-player decides not to punish the A-player for her/his theft), 100, or 150 tokens.

Second, regarding the VCT and VGRT, if the A-player does not take money from the B-player, the final payoff is the same for each player and is equal to the initial endowment of 200 tokens each.

If the A-player steals 50 tokens from the B-player, the payoffs are as follows:

Where:

SF is again the amount of punishment imposed on the A-player, be it by the C-player or (eventually) the D-player. If the D-player decides to punish the A-player (and, thus, confirms the decision taken by C-player), it corresponds to the level of sanction chosen by the C-player. If the D-player’s punishment deviates from that by the C-player, the D-player’s decision is relevant, superseding (in all directions) C-player’s choice. Hence, the ultimate punishment for the C-player corresponds to the level of sanction decided by the D-player. It may be equal to 0 (if the final decision is not to punish the A-player for the theft), 100, or 150 tokens.

SD = 20 is the “sanction” the C-player receives (the disutility that the C-player suffers) if the D-player overturns her/his decision.

The reason to choose this pay-off structure, where we consider the costs of punishment without the “potential” benefits, is twofold. First, we do not want to present an overly complicated design. Secondly, in Italy, where we run our experiment, additional monetary benefits with respect to the initial endowment for third parties may sound strange for the experiment participants. In real life, judges receive a wage.

4 Experimental Hypotheses

In this part, we present our hypotheses regarding the final level of punishment in the different treatments. Hypotheses 1 and 2 consider both the homo economicus and behavioral perspectives. The third hypothesis is based on two different ways of reasoning. In fact, we divide the hypothesis in two possible results: the first is the opposite with respect to the second.

Hypothesis 1: The level of punishment is higher in the VCT than in the BT. [30]

Both the baseline treatment and the second-instance treatment involve cases of possible altruistic third-party punishment (be it, in the BT, that the C-player has the punishment option or, as in the VCT, that the D-player has the last word on punishment). In a narrowly conceived homo-economicus world, costly punishment will not be meted out, because it implies cost without (instrumental) benefit. Anticipating thus zero costly punishment by the C-player, the rational choice for the A-player is to take the B-player’s entire endowment. In the VCT, nothing would change because, in backward induction, there are again no instrumental grounds for the D-player to reverse, in a manner costly for herself/himself, the C-player’s punishment decision. Anticipating the lack of incentives for reversal, the C-players may disregard the presence of a second instance and simply pursue their rational choices as before, i.e. to avoid, on their part, costly punishment. The A-player would again “steal with impunity”.

Only if we introduce, in line with previous experimental results, a behavioral perspective, may we expect a certain degree of punishment in the baseline treatment. Third-party punishment is considered to be a social order enforcement device. A sort of golden keystone of social stability (see Chaudhuri 2011; Gachter and Herrmann 2009; Lewisch 2020). Studies (e.g., Fehr & Gächter 2002) show that people are willing to sacrifice resources to punish norm violations, even when they gain nothing. Even when not personally involved, people care about how others treat each other. Experimental evidence confirms this point (see Fehr and Fischbacher 2004, Ottone et al. 2015, among others).

What changes may we expect in a VCT-world? Given that reversals are costly and confirmations are not, there is, first of all, a certain status quo bias (Kahneman et al. 1991) in favor of any decision taken by the C-player. One may, moreover, further distinguish between punishment and non-punishment decisions by the C-player. In principle, punishment by the C-player can be construed as an altruistic (“social”) act, namely as a positive interference with (or as a “correction” of) a seemingly unjust act committed by A-player (therefore, as a type of unilateral – costly – dispute resolution). Will we expect the D-players to correct a punishment decision by C-player? In light of the foregoing, it seems rather unlikely that the D-players would sacrifice their money to reverse what could be framed prima facie as the “social act” of costly punishment. Would the D-players, in turn, reverse a non-punishment decision by the C-player? This is a less straightforward question. Whereas any reversal is costly, the D-players may wish to punish the A-players (in order to answer their “theft” vis-à-vis the B-player), but they may also be driven by the wish to “correct” (and insofar to “punish”) the C-players, who selfishly did not carry out altruistic punishment to protect their own resources. In such a situation, even self-interested C-players may carry out punishment to avoid the potential reversal of their sentence by the D-players. Altogether, these factors are likely to contribute, in a behavioral perspective, to a slight overall trend towards an increase in punishment (i.e. more punishment to be expected in the VCT than in the baseline treatment). These factors lead us to predict an increase in the level of punishment in the VCT with respect to the BT. This would confirm the result found in Lewisch et al. (2015).

Hypothesis 2: The level of punishment in the GRT is higher than or equal to the level of punishment in the BT.

Would requiring participants to provide reasons for their punishment decisions increase the incidence of punishment? Obviously, this requirement would be without any effect for the hard-nosed homo economicus, because she/he would not carry out costly punishment in any situation. In a more behaviourally oriented world, the obligation to motivate one’s decision is likely to have an effect. On the one hand, “giving reasons” forces the potential punisher to “think twice” about his decision and reflect on both the underlying deed and her/his reasons to answer or not answer this unsocial act, with a slight tendency to not leave such an act unchallenged. On the other hand, this requirement may also lead to reflexions by the potential punisher regarding the question whether her/his spontaneous impulse for punishment is worth the cost associated therewith.[31]

In the realm of this hypothesis, we assume that a (costless) no-punishment decision is quick and easy, whereas the requirement to motivate one’s-decision triggers reflections that instead increase the likelihood of punishment. Whereas the required reasons could, in cases of non-punishment decisions, also evoke the absence of meaningful deterrence in one-shot interactions, they would often also implicate a confrontation with shame/guilt when putting on paper a selfish reason for not punishing. Depending on the composition of the population on the experiment, we would cautiously predict an ultimate punishment level that is equal to or higher than the level of punishment in the BT.

In the GRT treatment, the reasons by the C-player are not communicated to other players. Consequently, we can rule out the possibility that a higher level of punishment may be due to the fact that a non-punishment choice is difficult to justify to the B-player (the victims).

Hypothesis 3A: The level of punishment in the VGRT is higher than the level of punishment in the VCT and GRT.

This hypothesis is based on the assumption that both mechanisms, viewed separately, are likely to generate, in a behavioral perspective, an increased incidence of punishment, so that this effect shall only be reinforced when both institutional changes apply jointly. Or put differently, if setting GRT as well as VCT is likely to foster punishment, we should expect an even stronger positive effect on punishment if we bring the two settings together.

Hypothesis 3B: The level of punishment in the VGRT is lower than the level of punishment in the VCT. The effect with respect to the BT and the MT is uncertain.

This hypothesis is based on the assumption that, whereas both mechanisms have a positive effect on punishment, the combination of vertical control and “giving reasons” need not necessarily generate super-positive results. Provided for communication between the punishers, opportunistic C-players could attempt to abuse the opportunity to motivate their decision for purposes of influencing the D-players and not carry out costly punishment against them. The underlying intuition would be the following: In a scenario with vertical control, where choices cannot be justified, C-player’s decision to not punish may be risky in terms of triggering punishment by the D-players. In turn, in a motivated decision, the C-players are able to explain their motives for non-punishment (be it the absence of deterrence purposes, the lack of an explicit prohibition of stealing in the formal instructions, or a homo economicus reasoning) and also attempt to convince the D-players that it would be in their best interest to leave the punishment decision by the C-players unaltered (in which case, both the C-player and D-player could save their resources). To be sure, any such attempt to influence the D-players would also be possible if the C-player actually punishes the A-player (explaining to the D-players that it would be unwise to alter such a “social” decision in light of the costs associated therewith). The “communication tool”, however, seems more attractive for the non-punishment decision, where the C-players can also explain their “good” reasons for the seemingly unsocial act of non-punishment and the advantage for the D-players to leave such a decision unaltered.

5 Results – Data Analysis

We ran three sessions for each treatment. Overall, 319 students at a University in northern Italy[32] participated in the experiment.[33] With the final questionnaire, we collected data concerning standard demographic characteristics (gender, age, occupation, religious beliefs[34]), as well as information revealing participants’ attitudes towards intervening to correct unfairness and solve real or potential conflicts (volunteering activities, chosen option in the classic trolley game[35]). Finally, we checked whether participants were naive experimental subjects by asking them whether it was the first time they participated in an experiment.

About half of participants (53.3 %) are male. Less than 24 % are currently employed. More than half of participants are religious (61.8 %). 21.3 % are volunteers. 19 % were participating in an experiment for the first time. Table 2 reports how these variables are distributed across the treatments. Statistical analyses show some differences, especially between MT and VCMT. In any case, the econometric analysis allows us to examine whether potential differences between the treatments are affected by these characteristics.

This means that, during the experimental campaign, we collected observations from 173 cases. Due to the composition of the groups and the fact that each C-player participates in a single game, whereas each D-player participates in three games, we collected 173 independent observations from 173 C-players (42 in BT, 45 in VCT, 42 in MT, 44 in VCMT) as well as 90 choices from 30 D-players (15 in the VCT and 15 in VCMT).

We conducted our analysis in several steps, focusing on the relative changes in terms of punishment (5.1.) and of the underlying “criminal” behavior (5.2.).

5.1 Punishment

5.1.1 Overview

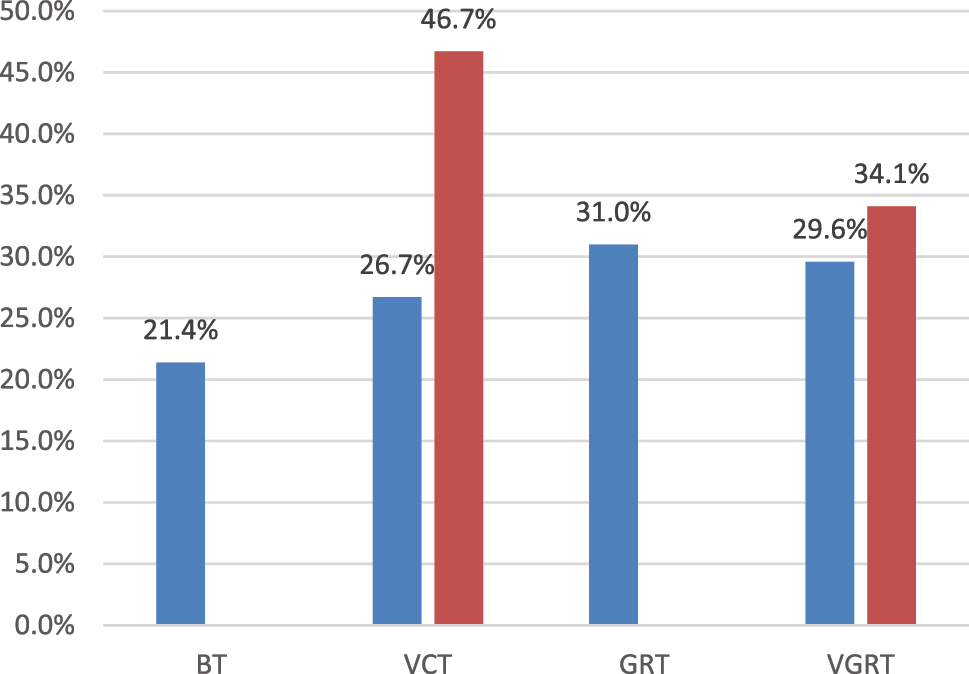

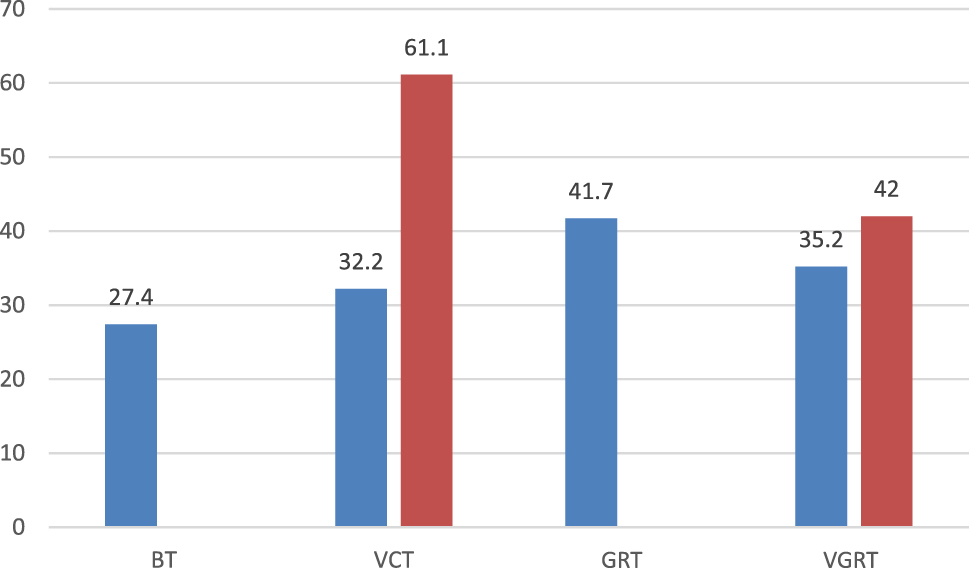

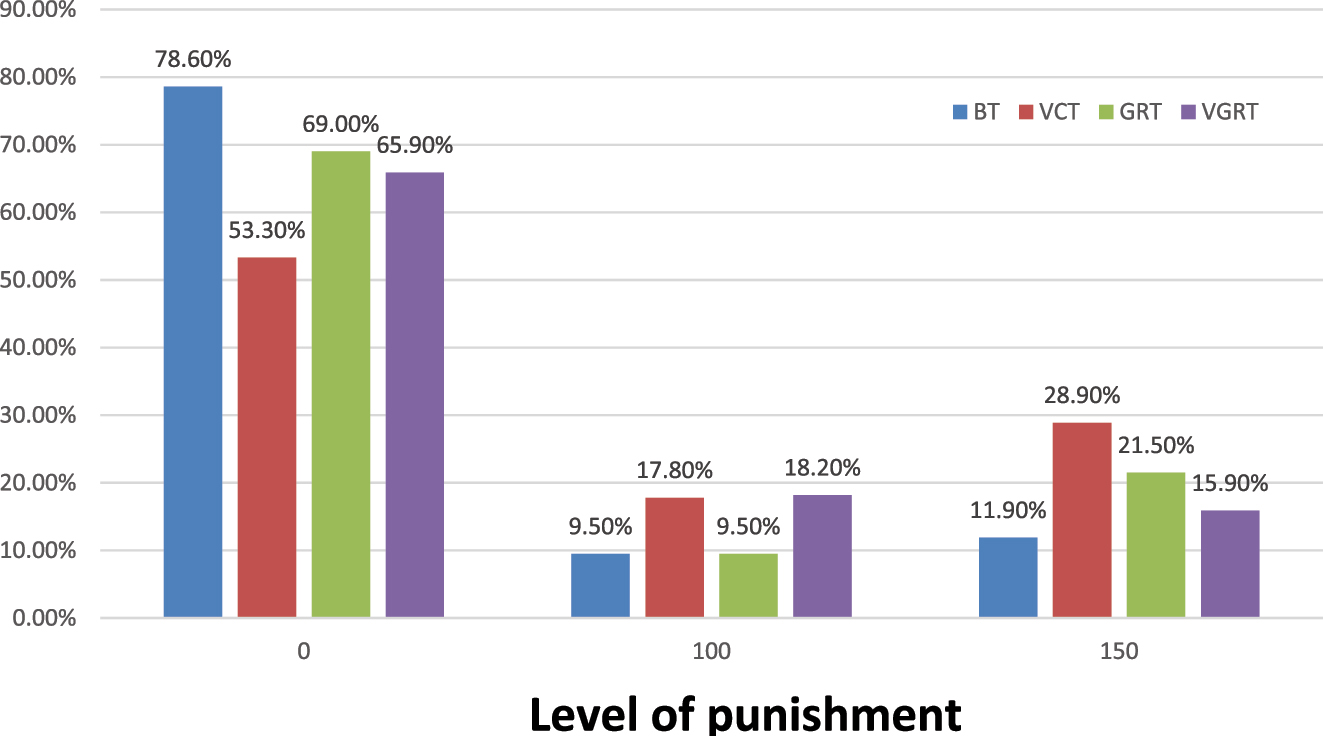

This section is devoted to an overview of our experimental evidence concerning both the probability to punish and the average level of punishment across the treatments. In particular, Figures 4 and 5 represent:

for each treatment, the percentage of C-players who decide to punish and the average level of punishment in case of theft. When “vertical control” is implemented, the C-player’s choice is the “first-instance decision”;

for each treatment where “vertical control” is implemented, the final percentage and the average level of punishment in case of theft. When we use the adjective “final”, we refer to the decision that it is eventually implemented in the case of theft. When “vertical control” does not exist, the final choice corresponds to the C-player’s choice. In the two treatments that include “vertical control”, the final choice is made by the D-player. The final decision corresponds to the C-player’s choice if the paired D-player confirms her/his decision; otherwise, player-D’s choice is implemented.

What emerges from the visual evidence is that both instruments increase punishment. Focusing first on the C-players’ choices, we can observe that, in the BT, the percentage of sanctioned theft (incidence of punishment) is 21.4 %, whereas, in the VCT, the percentage of punishment by the C-players increases to 26.7 %. When C-players must provide reasons for their choices, the percentage of punishment is close to 31 %, which is 10 % more than in our baseline scenario. On the level of punishment decisions by the C-players, the jump upwards in the incidence of punishment is even more pronounced than in the VCT. When we combine the two instruments, the punishment rate by the C-players of 29.5 % is slightly higher than the punishment rate in the (not motivated) VCT (which is 26.7 %) and slightly lower than in the stand-alone “giving-reasons scenario” (which is 31 %).

If we look to the overall outcome in terms of punishment, comparing the final decision, we find that in the VCT the ultimate punishment rate jumps up to 46.7 %. This is a large increase in the incidence of punishment and higher than in all other scenarios (21.4 % in the BT, 31 % in the GRT and 34.1 % in the VGRT).

The same trend emerges when we analyze the average level of punishment in each treatment. Introducing the stand-alone instrument “giving reasons” leads to the highest incidence of punishment by the C-players (27.4 % in the BT, 32.2 % in the VCT, 41.7 % in the GRT, 35.2 % in the VGRT), whereas the stand-alone mechanism of “vertical control” has the most incisive effect on the final decision (27.4 % in the BT, 61.1 % in the VCT, 41.7 % in the GRT, 42 % in the VGRT).

We perform a series of non-parametric tests. We first check whether the two instruments – “vertical control” and “giving reasons” – affect C-players’ choices. Even if, graphically, both the percentage and the average level of punishment increase when we switch from the BT to the other treatments, non-parametric tests report no statistical significance (Mann-Whitney tests, p > 0.32 and p > 0.28 when considering all pairwise comparisons of treatments on percentage and the average level of punishment, respectively). On the other hand, when we perform our statistical analysis on the final decision (i.e. the decision by the D-players), we find that punishment significantly increases in the VCT, that is, when only the “vertical control” is implemented (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0009 and p = 0.0036 when considering percentage and the average level of punishment, respectively; Mann-Whitney tests performed on all pairwise comparisons of treatments, p-value significant when comparing the VCT to the other treatments; see Table 3 for details).[36]

The econometric analysis we run in the next section will provide more details concerning these preliminary results.

5.1.2 Methodology

Our econometric analysis is threefold. In a first step, we analyze the consequences of the introduction of a second instance on the (i) overall punishment and (ii) changes in the frequency of punishment by the C-players. In doing this, we first focus on C-players’ choices in order to understand whether the introduction of a vertical control has some effect on the first instance decision maker. Then, we analyze the final verdict in order to understand whether there is a propensity of the “vertical controller” to correct the sentences.

In the second step, we investigate the effects of introducing the “giving reasons” requirement.

The third step aims to examine the combined effect of the two mechanisms, namely to check whether the joint application of both institutional tools (“second instance” and “giving reasons”) would lead to an increase or decrease in punishment relative to the baseline scenario and/or relative to the introduction of only one of the two instruments separately.

Regarding the methodology applied, we conducted a series of probit regressions. In our first probit regression, we examine whether the probability for C-players to punish is affected by the instrument we implement in the lab. The dependent variable is the probability for C-players to punish and the regressors are dummy variables for instruments and socio-demographic characteristics. The regression is clustered at the session level.

Our probit specification is:

Where FIRST_INSTANCE_PUNISHMENT i is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the ith C-player decides to punish; VERTICAL_CONTROL i is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the observation belongs to a treatment where “vertical control” is implemented; GIVING_REASONS i is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the observation belongs to a treatment where “giving reasons” is implemented; VERTICAL_CONTROL*GIVING_REASONS&MOTIVATIONi is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the observation belongs to the VGRT (the only treatment where both instruments are implemented); and CONTROLS i represents all the controls mentioned in the first part of Section 5 and described in Table 2. Table 4 reports the most relevant results of our regression.[37]

In our second probit regression, we examine the probability that the final decision – as explained in the previous section – is affected by the two instruments. The dependent variable is the probability that the final decision is to punish the A-player and the regressors are, again, dummy variables for instruments and socio-demographic characteristics. The regression is clustered at the group level.[38]

Where FINAL_PUNISHMENT i is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the A-player in the group is punished (regardless of whether the decision depends on the C-player or the D-player). Table 5 reports the most relevant results of our regression.[39]

Our last regression is an ordered probit regression on the different levels of final punishment across the treatments, clustered at the group level. Our specification is:

Where FINAL_LEVEL_PUNISHMENT i is equal to 0, 100, or 150. Table 6 reports the most relevant results of our regression.[40]

5.1.3 Results

Result 1:

Introducing the “vertical control” increases the level of punishment. Hypothesis 1 is confirmed.

Our first results concern the analysis of punishment levels when “vertical control” is included. The results are clear and straightforward. The introduction of a “second instance” leads to a substantial increase in the incidence of punishment, namely – worth noting – even at the first-instance level and – even more so – in terms of the respective ultimate punishment decisions. The econometric analysis confirms this point. When “vertical control” is implemented, the probability that C-players punish A-players in the case of theft increases (in R1 marginal effect of VERTICAL_CONTROL dummy is equal to 0.11 and p = 0.052, see Table 4). The same result holds when we analyse the final decision to punish thieves (in R2 marginal effect of VERTICAL_CONTROL dummy is equal to 0.297 and p = 0.003, see Table 5). Finally, focusing on the final level of punishment, harsh sanctions are more likely to be implemented (in R3 marginal effect of VERTICAL_CONTROL dummy to predict a harsh sanction is equal to 0.069 and p = 0.003, see Table 6). See Figure 6.

On the VCT scenario, where the stand-alone “vertical control” instrument is implemented, one can see that, in addition to the (already given) “first-instance increase” in punishment, the D-players intervened to a considerable extent regarding non-punishment decisions by the C-players and reversed those decisions into punishment decisions. In fact, in the VCT, 20 % of C-player’s verdicts were overturned. In all of these cases, D-players decided to introduce punishment when C-players chose not to punish. Moreover, D-players introduce harsh sanctions.

Result 2:

Punishment is higher when “giving reasons” is introduced. Hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

What about the consequences in terms of punishment levels due to the introduction of a “giving reasons” obligation? As anticipated by the visual evidence in Figures 4 and 5, when the “giving reasons” mechanism is implemented, the propensity to punish increases among C-players (in R1 marginal effect of GIVING_REASONS dummy is equal to 0.11 and p = 0.033, see Table 4). It is noteworthy that, in the GRT, where the stand-alone “giving reasons” instrument is implemented, this shift in punishment is not triggered by any anticipation of a potential sanction (in terms of a second instance that could overturn the decision in a manner costly for the first instance), but rather solely by the requirement to reflect on the punishment decision and write down a reason for one’s decision. It is equally noteworthy that the imposed duty to deliberate did not have the effect of hampering and mitigating a spontaneous punishment impulse in the sense that subjects would, upon reflection, reduce costly punishment vis-à-vis their first intuition in the pecuniary interest of saving one’s resources. If we analyse the reasons provided by C-players, we find that most punishers motivate their choice through fairness arguments (92 %, chi2 test, p = 0.000[41]), whereas participants who avoid punishment refer to selfish monetary interest related to the non-punishment choice (77 %, chi2 test, p = 0.000[42]).

Focusing on the final decision, from R2 and R3 it emerges that “giving reasons” has no effect (p = 0.294 and p > 0.24 respectively, see Tables 5 and 6). This point will be discussed in the next section.

Result 3:

Combining “vertical control” and “giving reasons” leads to a perverse effect on subjects’ choices: it decreases the propensity to punish with respect to a stand-alone implementation of these instruments, confirming Hypothesis 3B.

When both instruments are introduced together into the game, we again have a two-tier punishment system, with an obligation to motivate the punishment decision on the first-instance level. What are the results? The combination of the two instruments has no effect on C-players’ choices (see Table 4) but has a negative effect on the final punishment. It emerges from both R2 (marginal effect of VERTICAL_CONTROL*GIVING_REASONS dummy is equal to −0.233 and p = 0.04) and R3 (marginal effect of VERTICAL_CONTROL dummy to predict a harsh sanction is equal to −0.187 and p = 0.077). Since in R2 and R3 (see Tables 5 and 6) we observed a significant, positive effect for the dummy variable VERTICAL_CONTROL and no effect for GIVING_REASONS, the negative impact of the interaction variable VERTICAL_CONTROL*GIVING_REASONS implies that adding the “giving reasons” instrument to “vertical control” considerably reduces its positive effect. The reason why the overall punishment rate in the combined scenario falls short of the overall punishment rate in the stand-alone VCT is mainly due to differences in the confirmation percentage. Whereas, in the stand-alone VCT, D-players overturned non-punishment decisions by C-players in 20 % of the cases, in the combined treatment, 96 % of choices made by C-players were confirmed by D-players. This is a significant increase in the confirmation level vis-à-vis the VCT (Mann-Whitney test, z = 2.018, p = 0.004).

The conceivable boost in punishment from a combination of two (when considered alone) powerful institutional drivers of punishment rates does not occur. Results stagnate and even partially decrease.

How can we explain these results, and in particular the much higher confirmation rate in the combined treatment? In Section 4, we pointed to the possibility that the C-players may use – that is, “abuse” – the possibility to “motivate” their decision for purposes of indirectly (or even directly) influencing the D-players in their decision of whether to reverse the first-instance punishment decision, in particular by appealing to the D-players’ pecuniary self-interest to leave C-player’s decision not to punish unchallenged and avoid the costs of reversal. In fact, an analysis of the actual reasons given by the C-players for their decisions allows for a “look into the respective black-box”. If we analyse the nature of reasons given by the C-players in this treatment, we find that, again, most C-players opting for punishment (77 %) motivate their decision by fairness considerations. In contrast, when we analyse reasons of C-players who decide not to punish, we observe that they are more strategic than in the stand-alone GRT (71 % are self-oriented). In other words, some C-players attempt to justify their decision to convince D-players that upholding their own non-punishment-choice is convenient for them, as well. In other words, in some cases, non-punishers used the device of giving reasons, not only to defend their utility-maximizing-decision, but also to explicitly argue vis-à-vis the vertical controller that it would be optimal for D-players to leave the non-punishment-decision by the first instance unchanged. These results seem to suggest that “giving reasons” has not only an expressive value but also an instrumental function that can be exploited by self-interested subjects (C-players).[43] The combination of both institutional changes (second instance and giving reasons), therefore, leads to the perhaps counter-intuitive result that it does not further increase punishment rates vis-à-vis stand-alone scenarios of VCT and GRT. As such, it draws attention to a possible (negative) interplay of different institutional tools, when applied in combination, and the potential to off-set the positive effects or even trigger negative outcomes compared to the stand-alone case. The concrete results, however, depend strongly on the composition of the population and the degree of interaction between the C-players and the D-players.

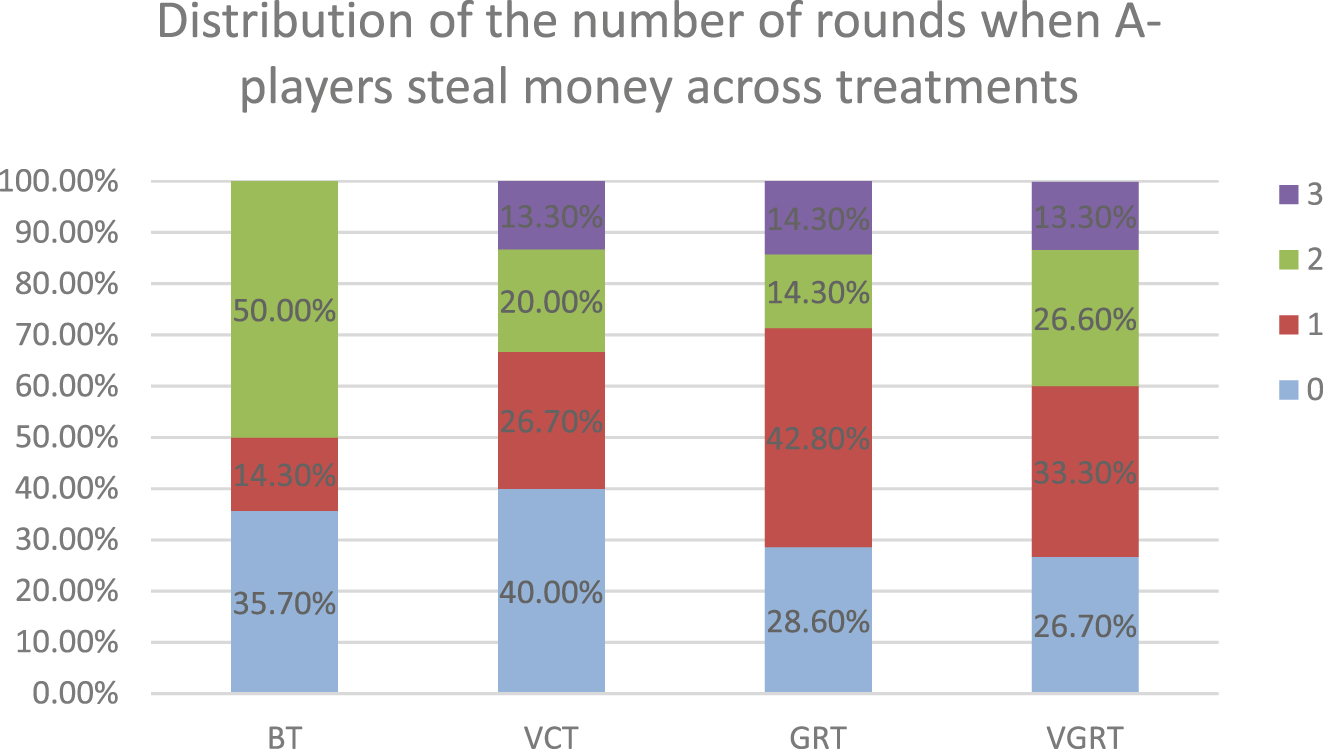

5.2 Crime: Incidence of “Theft”

A second set of questions concerns not the punishment side, but the underlying “theft behaviour”. Is there an effect of the pertinent institutional changes (giving reasons, second instance, combination) not only on the incidence of punishment but also on the incidence of the unwanted act of “taking” (“stealing”)? This is a complex question for two reasons. First, any influence of the aforementioned institutional variants on “crime” could only be indirect in the sense that the respective adaptions by the A-players (as the potential thieves) would hinge on their predictions regarding changes in the incidence of punishment. That is, potential thieves must first assume that the introduction of a giving reasons requirement or of a second instance would in fact influence the probability of punishment. Second, this in turn would render a theft less attractive, thus reducing the overall incidence of thefts. However, the presumed consequences of the aforementioned institutional changes for the incidence of punishment are by no means straightforward, as shown in Section 4. In particular, there is a decisive difference between predictions on a homo-economicus-basis and on a more pragmatic “behavioural” basis. It follows that there is a considerable part of “gut feeling” involved in the respective predictions by the A-players. Second, on top of these ambiguities, the effects for the incidence of crime will also depend on the composition of the population. People are heterogenous. So will be the A-players in terms of their estimates regarding the incidence of punishment and also their sensitivity towards any such changes. Only as an extremely crude guess may one predict a decrease rather than an increase in the incidence of thefts following the introduction of vertical control or a giving reasons requirement.

Looking now to our results, we must report a nil-result. Focusing on A-players’ behaviour, we find no real decrease in the amount of thefts (Figure 7). Non parametric tests confirm this evidence (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.948; Mann-Whitney tests on pairs of treatment, p > 0.55).

Since the results of our experiments do not show a decrease in the underlying incidence of crime, it seems important to relate them to the results of our 2015 paper on the effects of a two-tier punishment scheme.[44] In that experiment, we found some – again complex – influence of the introduction of a second instance on the underlying incidence of crime. On the one hand, in the 2015 paper, the introduction of a second instance reduced the crime rate such that, statistically, the baseline scenario would decrease the incidence of thefts, whereas the appeals-scenario would increase it. On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the expectations by the A-players of being punished in the two scenarios. This somewhat surprising finding led us to the conclusion that the A-players, while not having a thorough understanding as to the consequences of the pertinent institutional changes, relied instead on their crude intuition. This interpretation would be in line with the results reported here, with – of course – the notable difference that our new experiments do not show differences in the incidence of “thefts”.

What may explain the result of our new experiments (and, in fact, also those of the previous experiments) other than the aforementioned considerations regarding the complexity of the pertinent predictions? There is a limitation in our experiment regarding “learning”. That is, we do not provide A-players with feedback regarding C-players’ and D-players’ decisions. Regarding their punishment choices, the A-players can only rely on their crude rule-of-thumb guesses as to possible changes in punishment under a giving reason or second instance scenario. They cannot update their expectations from experience, such that there is no learning. Thus, one may claim that punishment as a norm enforcement device needs time to “roll out” and succeed. Only if the A-players learn that the institutional changes (vertical control, giving reasons) actually increase punishment levels will they take into account the changed environment and reduce stealing correspondingly.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to shed some light on the basic question of whether an implementation of institutional variants like “vertical control” and “giving reasons” influences the carrying out of costly punishment by potential punishers. We focus on these specific institutional instruments since both “vertical control” and “giving reasons” are generally presumed to be devices that improve the attractiveness of a procedural system. Moreover, both instruments aim to make judges’ decisions more deliberative and less intuitive.[45] The former because it drives first-instance judges to think more carefully about what is a correct and fair sentence in order to not be reversed by second-instance judges. The latter because it makes judges focus more on the rational and normative aspects of a conflict rather than on instinctive and emotional factors.[46]

The paper analyzes four different experimental settings, each of which stands for a separate institutional world (“naked” third-party punishment, vertical control, giving reasons, motivated punishment under vertical control). We believe that the paper is novel, namely that the impact of neither an (overriding) second instance,[47] a giving-reason requirement, nor the combination of the two have been studied previously.

Our main result is that both instruments (“vertical control” and “motivated punishment”) increase the level of costly punishment by non-involved observers (= potential punishers) in relation to the institution-less baseline scenario. Whereas the two instruments generate similar results, the changes are even more pronounced in a “giving reasons scenario” (which amounts to a remarkable 10%-points increase in the incidence of punishment vis-à-vis the baseline scenario). In contrast, a combination of the two (in themselves powerful) institutional devices, in a somewhat counter-intuitive manner, does not additionally increase punishment rates. This last-mentioned finding highlights a general point in procedural rule making, namely the possibility of countervailing effects in the overall procedural system. That is, procedural rules (aimed as such at a well-defined goal) allow the players in the system, even only as a side effect, to pursue their self-interest in an opportunistic manner. In addition, there is always the danger that the accomplishment of overall policy goals is weakened.[48]

Overall, our results show that the institutional framework of the respective setting has a considerable impact on the level of third-party punishment. Both the introduction of a second instance and the requirement of motivated decisions trigger a substantial effect on the incidence of punishment. A comparison between these two institutional tools, however, shows that these similar results come at a different cost, given that a second instance requires both more resources and more time than a mere giving-reasons-requirement. Whereas in our experiments the combination of the two tools generated the somewhat surprising “negative result” of a decrease – and not a further increase – in the incidence of punishment, this is not to suggest that such a combination is generally unadvisable on policy grounds. Our findings just alert us to the fact that players in procedural systems behave opportunistically and that they may misuse certain procedural instruments if they have the option to do so. Procedural rules shall, therefore, be designed such that they minimize the potential for such opportunistic behaviour. Under the appropriate incentives, a combination of a second instance and a requirement to provide reasoned decisions may work very well indeed.

Appendix- Figures and Tables

See Figures 1–7 and Tables 1–6.

Treatments.

Trees of the GAMES.

Percentage of C-players who decide to punish in case of theft (blue bars) and final percentage of punishment in case of theft when “vertical control” is implemented (red bars).

Average level of C-players’ punishment in case of theft (blue bars) and final level of punishment in case of theft when “vertical control” is implemented (red bars).

Final level of punishment in case of theft across the treatments.

Percentage of thefts over treatments.

Experimental design.

| Treatment | First instance control | Second instance control | Giving reasons | Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT | Yes | No | No | 70 subjects = 14 A-players 14 B-players 42 C-players |

| VCT | Yes | Yes | No | 90 subjects = 15 A-players 15 B-players 45 C-players 15 D-players |

| GRT | Yes | No | Yes | 70 subjects = 14 A-players 14 B-players 42 C-players |

| VGRT | Yes | Yes | Yes | 89 subjects = 15 A-players 15 B-players 44 C-players 15 D-players |

Demographic variables over treatments.

| BT | VCT | GRT | VGRT | Sign. Δa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 51.4 | 56.7 | 52.9 | 51.7 | – |

| Age (av.) | 21.8 | 21.6 | 22.2 | 22.1 | – |

| Job (%) | 27.1 | 22.2 | 30 | 16.8 | GRVT BT p = 0.085 GRT-VGRT p = 0.038 |

| First (%) | 18.6 | 17.8 | 11.4 | 27 | GRT-VGRT p = 0.012 |

| Believer (%) | 61.9 | 71.1 | 69 | 56.8 | – |

| Volunteer (%) | 20 | 22.2 | 17.1 | 24.7 | – |

| Trolley (%)b | 68.6 | 83.3 | 68.6 | 73 | VCT – BT p = 0.02 VCT – VGRT p = 0.068 |

-

aThis column focuses on the chi2 tests (for the variables indicated through percentages) and the t-tests (for the variables indicated through the average) run on each variable comparing their values across the different treatments taken in pairs. We report only the statistically significant results. In all the other cases, p > 0.32. bThis variable reports the percentage of subjects who decide to pull the lever in the trolley game. The same distribution across the treatments holds if we focus on the subsample of C- and D-players.

Non parametric tests on percentage of final punishment and average final level of punishment across the treatments.

| Percentage of Final punishment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal-Wallis test chi2 = 16.582 p = 0.0009 | ||||

| Pairwise Mann-Whitney tests | ||||

| BT | VCT | GRT | VGRT | |

| VCT | p = 0.000 | X | X | X |

| GRT | p = 0.0629 | p = 0.0153 | X | X |

| VGRT | p = 0.0998 | p = 0.0351 | p = 0.9889 | X |

| Average level of final punishment | ||||

| Kruskal-Wallis test chi 2 = 13.523 p = 0.0036 | ||||

| Pairwise Mann-Whitney tests | ||||

| BT | VCT | GRT | VGRT | |

| VCT | p = 0.0003 | X | X | X |

| GRT | p = 0.0649 | p = 0.0856 | X | X |

| VGRT | p = 0.256 | p = 0.0158 | p = 0.6124 | X |

Probit regression (R1) – marginal effects (standard errors in brackets).

| Dependent variable: C-player’s decision to punish A-player | |

|---|---|

| Cluster at session level | |

| Punishment | |

| Vertical control | 0.113* |

| (0.058) | |

| Giving reasons | 0.111** |

| (0.052) | |

| Vertical control*giving reasons | −0.13* |

| (0.077) | |

| Socio-demographic controls | Yes |

| Personal characteristics controls | Yes |

| N | 173 |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −93.291901 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0781 |

-

***1 % significance **5 % significance *10 % significance.

Probit regression (R2) – marginal effects (standard errors in brackets).

| Dependent variable: final decision to punish A-player | |

|---|---|

| Cluster at group level | |

| Punishment | |

| Vertical control | 0.297*** |

| (0.099) | |

| Giving reasons | 0.104 |

| (0.099) | |

| Vertical control*giving reasons | −0.233** |

| (0.113) | |

| Socio-demographic controls | Yes |

| Personal characteristics controls | Yes |

| N | 173 |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −102.61779 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0218 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0700 |

-

***1 % significance **5 % significance *10 % significance.

Ordered probit regression (R3) – marginal effects (standard errors in brackets).

| FLP = 0 | FLP = 100 | FLP = 150 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VERTICAL CONTROL | 0.285*** | 0.069*** | 0.217*** |

| (0.095) | (0.023) | (0.079) | |

| GIVING REASONS | −0.100 | 0.024 | 0.076 |

| (0.09) | (0.022) | (0.069) | |

| VERTICAL CONTROL*GIVING REASONS | −0.144 | 0.034 | 0.110 |

| (0.108) | (0.025) | (0.084) | |

| Socio-demographic controls | YES | ||

| Personal characteristics controls | YES | ||

| N | 173 | ||

| Log pseudolikelihood | −141.90076 | ||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0459 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0520 |

-

***1 % significance **5 % significance *10 % significance.

International courts are, in principle, monolythic bodies that do not have another court above them. Still, a considerable number of these courts provide for a certain type of a “second instance” (or quasi-second instance).

References

Chaudhuri, A. 2011. “Sustaining Cooperation in Laboratory Public Goods Experiments: A Selective Survey of the Literature.” Experimental Economics 14 (1): 47–83.10.1007/s10683-010-9257-1Search in Google Scholar

Drahozal, C. R. 1998. “Judicial Incentives and the Appeals Process.” SMU Law Review 51 (3): 469–503.Search in Google Scholar

Engel, C., and L. Zhurakhovska. 2014. “Conditional Cooperation with Negative Externalities – an Experiment.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 108 (C): 252–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.10.005.Search in Google Scholar

Fees, E., and R. Sareel. 2018. “Judicial Effort and the Appeals System: Theory and Experiment.” Journal of Legal Studies 47 (2): 269–94.10.1086/699391Search in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and U. Fischbacher. 2004. “Third-Party Punishment and Social Norms.” Evolution and Human Behavior 25 (2): 63–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(04)00005-4.Search in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and S. Gaechter. 2000. “Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments.” The American Economic Review 90 (4): 980–94.10.1257/aer.90.4.980Search in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and S. Gaechter. 2002. “Altruistic Punishment in Humans.” Nature 415 (6868): 137–40.10.1038/415137aSearch in Google Scholar

Fischbacher, U. 2007. “z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox for ready-made Economic Experiments.” Experimental Economics 10 (2): 171–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4.Search in Google Scholar

Flage, A. 2024. “Taking Games: A Meta Analysis.” Journal of the Economic Science Association 10 (3): 255–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-023-00155-1.Search in Google Scholar

Fuller, L. L., and K. I. Winston. 1978. “The Forms and Limits of Adjudication.” Harvard Law Review 92 (2): 353–409. https://doi.org/10.2307/1340368.Search in Google Scholar

Gachter, S., and B. Herrmann. 2009. “Reciprocity, Culture and Human Cooperation: Previous Insights and a New Cross-Cultural Experiment.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364 (1518): 791–806.10.1098/rstb.2008.0275Search in Google Scholar

Guthrie, C., J. J. Rachlinsky, and A. J. Wistricht. 2007. “Blinking on the Bench: How Judges Decide Cases.” Cornell Law Review 93 (1): 1–44.Search in Google Scholar

Higgins, R. S., and P. H. Rubin. 1980. “Judicial Discretion.” The Journal of Legal Studies 9 (1): 129–38, https://doi.org/10.1086/467631.Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, D., J. Knetsch, and R. Thaler. 1991. “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias.” Journal of Economic Perspective 5 (1): 193–206, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.193.Search in Google Scholar

Lewisch, P. 2020. “Altruistic Punishment: The Golden Keystone of Human Cooperation and Social Stability?” Analyse & Kritik 42 (2): 255–83.10.1515/auk-2020-0011Search in Google Scholar

Lewisch, P., S. Ottone, and F. Ponzano. 2015. “Third-Party Punishment Under Judicial Review: An Economic Experiment on the Effects of a Two-Tier Punishment System.” Review of Law and Economics 11 (2): 209–30. https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2015-0018.Search in Google Scholar

Mischkowski, D., A. Glöckner, and P. Lewisch. 2018. “From Spontaneous Cooperation to Spontaneous Punishment: Distinguishing the Underlying Motives Driving Spontaneous Behaviour in First and Second Order Public Good Games.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 149: 59–72.10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.07.001Search in Google Scholar

Ottone, S., F. Ponzano, and L. Zarri. 2015. “Power to the People? An Experimental Analysis of Bottom-Up Accountability of Third-Party Institutions.” The Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 31 (2): 347–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewu007.Search in Google Scholar

Posner, R. A. 2005. “Judicial Behavior and Performance: An Economic Approach.” Florida State University Law Review 32: 1259–79.Search in Google Scholar

Shavell, S. 2006. “The Appeals Process and Adjudicator Incentives.” Journal of Legal Studies 35 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1086/500095.Search in Google Scholar

Szego, B. 2008. “Le Impugnazioni in Italia: Perchè le riforme non hanno funzionato.” Quaderni di Ricerca Giuridica della Consulenza Legale 61. Bank of Italy.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2024-0055).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.