Abstract

Should managers be liable for ill-conceived business decisions? One answer is given by U.S. courts, which almost never hold managers liable for their mistakes. In this paper, we address the question in a theoretical model of delegated decision making. We find that courts should indeed be lenient as long as contracts are restricted to be linear. With more general compensation schemes, the answer depends on the precision of the court’s signal. If courts make many mistakes in evaluating decisions, they should not impose liability for poor business judgment.

Appendix

First, take a

Because

It then also follows that

Second, take a

such that if

because there is more weight on the larger of the two payoffs. If instead

The first claim is a direct consequence of risk aversion. With a linear contract, the expected wage (without liability) from the risky project at

For the proof of the second claim, we define

the agent also prefers the risky to the safe project with no liability and the contract

The intuition behind this result is that the agent would be willing to pay at least

Using [18], we can conclude that

With reasoning as before, we get

and from this

Because

Again, we let

We will show in the following that the principal gets a higher payoff with

we can apply Lemma 2, and get

Next, we will show that the agent is weakly better off with

where

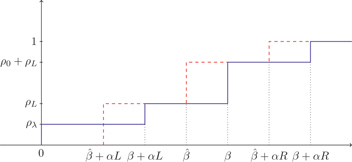

The (red) dashed line is the distribution function

We use this figure to show that

Knowing that the agent’s utility is weakly greater under no liability immediately gives us the participation constraint

We consider the problem of implementing a given

It holds that

with the usual complementary slackness conditions. Using these necessary conditions we can prove that in any optimum it holds that

This follows from

We can immediately determine the sign of

If

It can be seen that if

In the following, we solve the problem of choosing

We know that

the first two terms in

Note that the left hand side shows the direct effect of a change in

We can exploit that

where

Assume first that

which means that

Assume now

and therefore

and

We can conclude that

hence

We have to show that in these two cases

We have to show that this expression is increasing in

For the linear error term with distribution

For the normal error term with distribution

and, using integration by parts,

Putting everything together, we get

In a first step, we show that as the signal becomes more precise, eventually a positive standard must be better. We show that with a perfect signal, the same threshold as under no liability,

For the so defined contract it holds that

It exposes the agent to a lottery between

In a second step, we consider the limit

It remains to show that the principal’s payoff, once it is equal to

where we have modified the earlier notation to make the dependence on precision explicit. We now look at the principal’s cost of implementing

It follows from Assumption 1 that

and consequently

Because

This time, we cannot a priori exclude the case that the monotonicity constraint is binding in the other direction

Let

For the regime

In case that

and are satisfied due to our assumptions. In general, we can only show that there should be no liability after the safe alternative

with

The first order conditions are now

Only the first constraint has changed, and it follows immediately that

if either

As before,

and hence implies

Hence, the cost of implementing any

We will show that if the signal is as precise as stated and the standard is set at

To conclude from the assumption on

which holds because

The result that

Next we consider the case

while

and

From

which implies

Exploiting

Since the right-hand side is increasing in

For linear contracts we know that

For the case of more general contracts, Lambert (1986) treats the case without liability in detail and shows that if

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous referees as well as Matthias Lang, Holger Spamann, Kathryn Spier, participants of the SFB TR 15 meeting in Caputh and seminar participants in Frankfurt and Bonn for helpful comments and suggestions.

References

Allen, William T., Jack B. Jacobs and Leo E. Strine Jr. 2002. “Realigning the Standard of Review of Director Due Care with Delaware Public Policy: A Critique of Van Gorkom and Its Progeny as a Standard of Review Problem,” 96(2) Northwestern University Law Review 449–466.Search in Google Scholar

American Law Institute. 1992. Principles of Corporate Governance: Analysis and Recommendations, Vol. 1. St. Paul, MN: American Law Institute Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Armour, John and Jeffrey N. Gordon. 2014. “Systemic Harms and Shareholder Value”, 6 Journal of Legal Analysis 35–85.10.1093/jla/lau004Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Tom and Sean J. Griffith. 2010. Ensuring Corporate Misconduct, How Liability Insurance Undermines Shareholder Litigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226035079.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Biais, Bruno and Catherine Casamatta. 1999. “Optimal Leverage and Aggregate Investment,” 54(4) The Journal of Finance 1291–1323.10.1111/0022-1082.00147Search in Google Scholar

Black, Bernard S., Brian R. Cheffins and Michael Klausner. 2006a. “Outside Director Liability”, 58 Stanford Law Review 1055–1159.10.2139/ssrn.382422Search in Google Scholar

Black, Bernard S., Brian R. Cheffins and Michael Klausner. 2006b. “Outside Director Liability: A Policy Analysis,” 162(1) Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 5–20.10.1628/093245606776166543Search in Google Scholar

Bundesgerichtshof. 2005. “Judgment 3 StR 470/04 of December 21, 2005,” 50(1) Entscheidungen Des Bundesgerichtshofs in Strafsachen 331–346.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Rutherford B. 2011. “Normative Justifications for Lax (or No) Corporate Fiduciary Duties: A Tale of Problematic Principles, Imagined Facts and Inefficient Outcomes,” 99(2) Kentucky Law Journal 231–257.Search in Google Scholar

Chaigneau, Pierre, Alex Edmans and Daniel Gottlieb. 2014. “The Informativeness Principle Under Limited Liability,” European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) - Finance Working Paper No. 439/2014.10.3386/w20456Search in Google Scholar

Chancery Court of Delaware. 1996. “Gagliardi v. Trifoods International, Inc., Atlantic Reporter,” Atlantic Reporter, 2d Series, 683, 1049–1055.Search in Google Scholar

Chancery Court of Delaware. 2009. “In re Citigroup Inc. Shareholder Derivative Litigation,” Atlantic Reporter, 2d Series, 964, 106–140.Search in Google Scholar

Craswell, Richard and John E. Calfee. 1986. “Deterrence and Uncertain Legal Standards,” 2 Journal of Law Economics & Organization 279–303.Search in Google Scholar

Demski, Joel S. and David E. M Sappington. April 1987. “Delegated Expertise,” 25(1) Journal of Accounting Research 68–89.10.2307/2491259Search in Google Scholar

Easterbrook, Frank H. and Daniel R. Fischel. 1991. The Economic Structure of Corporate Law. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenberg, Melvin Aron. 1993. “The Divergence of Standards of Conduct and Standards of Review in Corporate Law,” 62(3) Fordham Law Review 437–468.Search in Google Scholar

Fairfax, Lisa. 2005. “Spare the Rod, Spoil the Director? Revitalizing Directors’ Fiduciary Duty Through Legal Liability”, 42 Houston Law Review 393–456.10.2139/ssrn.601970Search in Google Scholar

Fama, Eugene F. and Michael C. Jensen. June 1983. “Separation of Ownership and Control,” 26(2) Journal of Law and Economics 301–325.10.4324/9780203888711.ch6Search in Google Scholar

Fischel, Daniel R. 1985. “The Business Judgment Rule and the Trans Union Case,” 40 The Business Lawyer 1437–1455.Search in Google Scholar

Gevurtz, Franklin A. 2007. “Disney in a Comparative Light,” 55(3) American Journal of Comparative Law 453–492.10.1093/ajcl/55.3.453Search in Google Scholar

Gromb, Denis and David Martimort. November 2007. “Collusion and the Organization of Delegated Expertise,” 137(1) Journal of Economic Theory 271–299.10.1016/j.jet.2007.01.003Search in Google Scholar

Gutierrez, Maria. October 2003. “An Economic Analysis of Corporate Directors’ Fiduciary Duties,” 34(3) The RAND Journal of Economics 516–535.10.2307/1593744Search in Google Scholar

Hakenes, Hendrik and Isabel Schnabel. 2014. “Bank Bonuses and Bailouts,” 46(1) Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 259–288.10.1111/jmcb.12090Search in Google Scholar

Holmström, Bengt. 1979. “Moral Hazard and Observability,” 10(1) The Bell Journal of Economics 74–91.10.2307/3003320Search in Google Scholar

Innes, Robert D. October 1990. “Limited Liability and Incentive Contracting with Ex-Ante Action Choices,” 52(1) Journal of Economic Theory 45–67.10.1016/0022-0531(90)90066-SSearch in Google Scholar

Kadan, Ohad and Jeroen M. Swinkels. January 2008. “Stocks or Options? Moral Hazard, Firm Viability, and the Design of Compensation Contracts,” 21(1) Review of Financial Studies 451–482.10.1093/rfs/hhm077Search in Google Scholar

Kaplow, Louis and Steven Shavell. 1994. “Accuracy in the Determination of Liability,” 37 Journal of Law and Economics 1–15.10.3386/w4203Search in Google Scholar

Kraakman, Reinier, Hyun Park and Steven Shavell. 1994. “When Are Shareholder Suits in Shareholders’ Interests?”, Georgetown Law Journal 1733–1775.Search in Google Scholar

Lambert, Richard A. April 1986. “Executive Effort and Selection of Risky Projects,” 17(1) The RAND Journal of Economics 77–88.10.2307/2555629Search in Google Scholar

Malcomson, James M. January 2009. “Principal and Expert Agent”, 9(1) The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics.10.2202/1935-1704.1528Search in Google Scholar

Malcomson, James M. 2011. “Do Managers with Limited Liability Take More Risky Decisions?”, 20(1) An Information Acquisition Model,” Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 83–120.Search in Google Scholar

Matthews, Steven A. March 2001. “Renegotiating Moral Hazard Contracts Under Limited Liability and Monotonicity,” 97(1) Journal of Economic Theory 1–29.10.1006/jeth.2000.2726Search in Google Scholar

Murphy, Kevin J. 2013. “Executive Compensation: Where We Are, and How We Got There,” in George M. Constantinidis, Milton Harris, and Rene M. Stulz, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Finance, Vol. 2A: Corporate Finance. Elsevier (North Holland), 211–356.10.1016/B978-0-44-453594-8.00004-5Search in Google Scholar

Nowicki, Elizabeth. 2008. “Director Inattention and Director Protection Under Delaware General Corporation Law Section 102(B)(7): A Proposal for Legislative Reform,” 33(3) Delaware Journal of Corporate Law 695–718.Search in Google Scholar

Palomino, Frédéric and Andrea Prat. 2003. “Risk Taking and Optimal Contracts for Money Managers,” 34(1) The RAND Journal of Economics 113–137.10.2307/3087446Search in Google Scholar

Rachlinski, Jeffrey John, Andrew J. Wistrich and Chris Guthrie. 2011. “Probable Cause, Probability, and Hindsight,” 8(S1) Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 72–98.10.1111/j.1740-1461.2011.01230.xSearch in Google Scholar

Raith, Michael. 2008. “Specific Knowledge and Performance Measurement,” 39(4) RAND Journal of Economics 1059–1079.10.1111/j.1756-2171.2008.00050.xSearch in Google Scholar

Spamann, Holger. 2015. “Monetary Liability for Breach of the Duty of Care?,” Harvard Law School John M. Olin Center Discussion Paper No. 835.10.2139/ssrn.2657231Search in Google Scholar

Supreme Court of Delaware. 1984. “Aronson v. Lewis,” Atlantic Reporter, 2d Series, 473, 805–818.Search in Google Scholar

Supreme Court of Delaware. 1985. “Smith v. Van Gorkom,” Atlantic Reporter, 2d Series, 488, 858–899.Search in Google Scholar

Supreme Court of Delaware. 2000. “Brehm v. Eisner,” Atlantic Reporter, 2d Series, 746, 244–268.Search in Google Scholar

Supreme Court of Michigan. 1919. “Dodge v. Ford Motor Co.” Northwestern Reporter, 170, 668–685.Search in Google Scholar

Towers Watson. 2013. “Directors and Officers Liability Survey 2012.”Search in Google Scholar

Trautman, Lawrence J. and Kara Altenbaumer-Price. 2012. “D & O Insurance: A Primer,” 1(2) American University Business Law Review 337–367.Search in Google Scholar

Ulmer, Peter. 2004. “Haftungsfreistellung Bis Zur Grenze Grober Fahrlässigkeit Bei Unternehmerischen Fehlentscheidungen Von Vorstand Und Aufsichtsrat?,” 57(16) Der Betrieb 859–863.Search in Google Scholar

Wagner, Gerhard. 2015. “Officers’ and Directors’ Liability Under German Law – A Potemkin Village,” 16(1) Theoretical Inquiries in Law 69–106.10.1515/til-2015-005Search in Google Scholar

©2017 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- The Economics of Scams

- Why Agents Need Discretion: The Business Judgment Rule as Optimal Standard of Care

- Voting Rules in Bankruptcy Law

- A Note on Trial Delay and Social Welfare: The Impact of Multiple Equilibria

- Malice Aforethought

- Weak Law v. Strong Ties: An Empirical Study of Business Investment, Law and Political Connections in China

- Estimating Judicial Ideal Points in Latin America: The Case of Argentina

Articles in the same Issue

- The Economics of Scams

- Why Agents Need Discretion: The Business Judgment Rule as Optimal Standard of Care

- Voting Rules in Bankruptcy Law

- A Note on Trial Delay and Social Welfare: The Impact of Multiple Equilibria

- Malice Aforethought

- Weak Law v. Strong Ties: An Empirical Study of Business Investment, Law and Political Connections in China

- Estimating Judicial Ideal Points in Latin America: The Case of Argentina