Abstract

Background and Objective

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex, heterogeneous autoimmune disease whose presentation can vary widely with patient age. While SLE in young adults has been extensively characterized, less is known about phenotypes of late-onset SLE.

Methods

This study aimed to characterize the features of late-onset SLE patients in a Chinese cross-sectional study. Patients diagnosed with SLE at age 50 years or older were classified as having late-onset SLE. Early-onset SLE patients from the same cohort were included as controls. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected, and a two-step cluster analysis was employed to categorize late-onset SLE patients.

Results

A total of 141 patients (27.48%) were classified as late-onset SLE. The onset of lupus in late-onset patients is more insidious, they exhibited lower systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index-2000 (SLEDAI-2K) scores, and had significantly fewer instances of fever, mucocutaneous, and positive of antibodies compared to early-onset SLE (all P values < 0.05). However, late-onset SLE patients had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, particularly Sjögren’s syndrome (P < 0.001). Additionally, late-onset SLE was associated with a high frequency of interstitial lung disease (ILD) and thrombotic events (P < 0.001, P < 0.001; respectively). Two distinct clusters of late-onset SLE patients were identified. Cluster 1 was characterized by the presence of SLE-specific autoantibodies such as anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-Smith (anti-Sm) with higher SLEDAI-2K scores (11.8 ± 5.2). In contrast, cluster 2 presented with a high frequency of anti-Sjögren syndrome antigen A (anti-SSA) antibodies and Sjögren’s syndrome with a significantly lower SLEDAI-2K scores (8.8 ± 5.4) at diagnosis.

Conclusion

This study refines our understanding of late-onset SLE by delineating two subgroups and suggests that age-stratified approaches to diagnosis and management may improve patient care.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that can present at any age, with diverse clinical manifestations. Although SLE most commonly begins in young women, a significant minority of cases occur later in life: studies estimate that roughly 10%–25% of SLE patients have disease onset at age ≥ 50 years.[1] In the literature, “late-onset” SLE is frequently defined by a cutoff of 50 years- an age threshold that roughly corresponds to the postmenopausal period- even though some authors have proposed higher cut-offs (such as 60 years).

Clinically, late-onset SLE is known to differ from younger-onset disease in several respects. Older patients tend to present more insidiously, with nonspecific symptoms (such as fatigue, weight loss, arthralgias) rather than the classic malar rash or severe nephritis seen in many younger patients.[2,3] In addition, comorbid conditions accumulate with age: previous reports have noted that older SLE patients have higher rates of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other autoimmune illnesses compared to younger patients.[4] However, the interplay between SLE manifestations and age-related comorbidities in late-onset SLE is not fully understood. In particular, it is unclear whether distinct subgroups (phenotypic clusters) exist among older-onset patients.

To address this, we conducted a cross-sectional study of patients diagnosed with SLE according to standard criteria, comparing those with disease onset at age ≥ 50 (late-onset SLE) to a reference group with onset at ages 18–49 years (adult-onset SLE). Our goal was to clarify the “dual nature” of late-onset SLE and elucidate how these subgroups might influence clinical practice.

Methods

Patients

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving 513 newly diagnosed SLE patients between October 2019 and July 2025 at The First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University. Patients were included based on either the 1997 revised American College of Rheumatology classification criteria [5] or the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics criteria [6] for SLE. To investigate the risk factors and clinical characteristics associated with late-onset SLE, patients were stratified into two groups: early-onset SLE (diagnosis age between 18 and 49 years) and late-onset SLE (diagnosis age ≥ 50 years). The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, and all patients provided informed consent (2024-SR-221).

Data Collection

At the time of SLE diagnosis, data were collected on a range of variables, including demographic, clinical and laboratory manifestations, comorbidities, treatments (hydroxychloroquine, daily prednisone intake, and immunosuppressive agents).

Laboratory data within 10 days before or at the time of hospitalization were recorded, including complete blood cell count, 24-hour proteinuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), complement 3 (C3) and complement 4 (C4), C-reactive protein (CRP), anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) by Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), anti-phospholipid antibodies (including anti-cardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-1[anti-β2GPI]; by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) and anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) (by ELISA or IFA). Additionally, autoantibodies such as anti-Sm, anti-small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (anti-snRNP), anti-nucleosome, anti-histone, anti-Sjögren syndrome antigen A or Ro60 (anti-SSA/Ro60), anti-Sjögren syndrome antigen A or Ro52 (anti-SSA/Ro52), anti-Sjögren syndrome antigen B or La (anti-SSB/La) were assessed using immunoblotting techniques. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) was evaluated using chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans.[7] A confirmed diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension (PAH) via Right Heart Catheterization (RHC), the diagnostic criteria for PAH were as follows: mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥ 20 mmHg as measured by hemodynamic (RHC), pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) ≤ 15 mmHg, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) ≥ 2 Wood units.[8] Disease activity was assessed using two standardized measures: (1) SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score;[9] (2) patient global assessment (PGA).[10] All variables were analyzed as observed, with no imputation of missing data.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using R software (version 4.4.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and GraphPad Prism software (version 10.1.2; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Continuous variables with normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation, while those with non-normal distribution are presented by median (Q1, Q3). The t test or Mann-Whitney U test was employed for continuous variables, while Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to control for age as a potential confounder in the comparison of comorbidities between early- and late-onset SLE groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To categorize subtypes of late-onset SLE patients, a two-step cluster analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 24.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).[11] In the first phase, variables are grouped into “pre-clusters”, which are then clustered using hierarchical clustering methods. During the pre-clustering phase, the two-step algorithm applies Euclidean distance to continuous variables and log-likelihood distance for discrete variables. In our analysis, the log-likelihood distance measure was used due to the binary nature of the variables. In the second phase, clusters are formed by applying hierarchical clustering based on the log-likelihood distance measure. The optimal number of clusters determined by the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the quality of clustering was evaluated using the silhouette score, which ranges from-1 to +1. Higher silhouette scores indicate better clustering quality, with values closer to +1 representing well-separated clusters, while values closer to-1 suggest poor clustering.[12]

Results

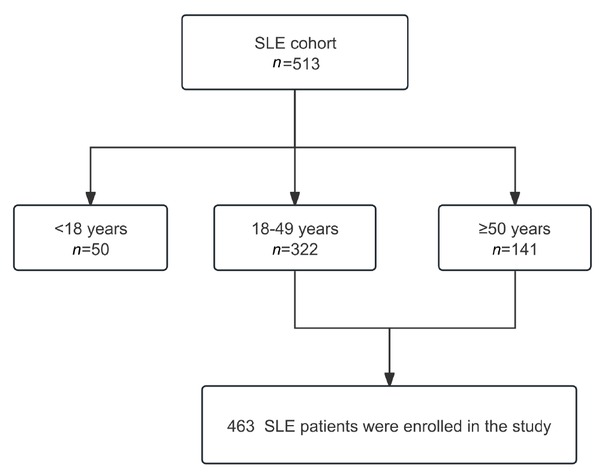

For the present study, we included a total of 513 cases of SLE, comprising 141 late-onset lupus patients and 322 early-onset lupus patients, as shown in Figure 1.

Flow diagram of SLE patient enrollment.

The Clinical Manifestation of Late-onset and Early-onset SLE Patients

Significant differences were observed between younger and older SLE patients. The female-to-male ratio was 3.4: 1 in the late-onset group and 6.5: 1 in the early-onset group (P = 0.012). Disease onset was defined as the interval from the first symptom or sign of lupus to the date the patients diagnosed with SLE fulfilled the classification criteria. There was a significant delay in the diagnosis of SLE among older patients [median 1.5 months (interquartile range [IQR] 1.0–3.1) vs. 1.0 months (IQR 0.5–2.1), P = 0.002]. Late-onset SLE exhibited significantly lower score of SLEDAI-2K (9.6 ± 5.3 vs. 12.3 ± 6.0, P < 0.001) and PGA (1.3 ± 0.6 vs. 1.5 ± 0.6, P < 0.001). Older SLE patients exhibited significantly lower prevalences of anti-Sm (41.84% vs. 57.14%), anti-dsDNA (42.55% vs. 64.91%), anti-nucleosome (31.91% vs. 55.59%), and anti-histone (31.91% vs. 48.76%) (all P < 0.05). Conversely, they had a significantly higher prevalence of anti-ribosomal P protein (anti-RPP) (16.31% vs. 4.35%, P < 0.001). The late-onset patients also displayed significantly higher mean complement levels (C3: 0.51 vs. 0.42 g/L; C4: 0.11 vs. 0.08 g/L, both P < 0.001), and lower eGFR (99.66 mL/min/1.73 m2 vs. 121.26 mL/min/1.73 m2, P < 0.001).

Late-onset SLE patients demonstrated a distinct clinical profile characterized by significant differences in organ involvement, comorbidities, and treatment patterns. They exhibited a substantially higher prevalence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) (9.22% vs. 2.17%, P < 0.001) but lower rates of fever (5.67% vs. 14.60%, P = 0.006) and mucocutaneous involvement (27.66% vs. 44.10%, P < 0.001). Older patients were significantly more likely to have overlapping connective tissue diseases, particularly Sjögren’s syndrome (26.95% vs. 11.18%, P < 0.001), systemic sclerosis (4.96% vs. 0.93%, P = 0.016), and rheumatoid arthritis (5.67% vs. 0.93%, P= 0.006). Comorbid conditions were markedly more frequent in the older group, including hypertension (30.50% vs. 11.80%, P < 0.001), diabetes (9.22% vs. 0.62%, P < 0.001), coronary heart disease (4.26% vs. 0.31%, P = 0.005). Treatment analysis revealed older patients received hydroxychloroquine less frequently (76.60% vs. 90.31%, P < 0.001) and biological agents less often (12.77% vs. 21.74%, P = 0.024), while their prednisone dosing distribution differed significantly (P = 0.005), with higher proportions receiving ≥ 1 mg/kg/d (72.34% vs. 65.84%). Table 1 provide detailed descriptive characteristics of early-onset and late-onset patients.

Clinical variables of early-onset and late-onset SLE patients

| 18–50 years, n = 322 | > 50 years, n = 141 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Female, n (%) | 279 (86.65) | 109 (77.30) | 0.012* |

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 31.99 ± 9.01 | 59.13 ± 7.45 | < 0.001* |

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Disease onset, month, M (Q1, Q3) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.1) | 1.5 (1.0, 3.1) | 0.002* |

| SLEDAI-2K, mean ± SD | 12.3 ± 6.0 | 9.6 ± 5.3 | < 0.001* |

| PGA, mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | < 0.001* |

| Laboratory and serology | |||

| Anti-Sm, n (%) | 184 (57.14) | 59 (41.84) | 0.002* |

| Anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 209 (64.91) | 60 (42.55) | < 0.001* |

| Anti-snRNP, n (%) | 186 (57.76) | 78 (55.32) | 0.625 |

| Anti-nucleosome, n (%) | 179 (55.59) | 45 (31.91) | < 0.001* |

| Anti-histone, n (%) | 157 (48.76) | 45 (31.91) | < 0.001* |

| Anti-SSA/Ro60, n (%) | 221 (68.63) | 87 (61.70) | 0.146 |

| Anti-SSA/Ro52, n (%) | 180 (55.90) | 69 (48.94) | 0.167 |

| Anti-SSB/La, n (%) | 123 (38.20) | 44 (31.21) | 0.149 |

| Anti-RPP, n (%) | 14 (4.35) | 23 (16.31) | < 0.001* |

| Anti-β2GPI moderate to high titers, n (%) | 30 (11.86) | 10 (8.70) | 0.366 |

| ACA moderate to high titers, n (%) | 49 (17.95) | 12 (9.02) | 0.018* |

| ANA titer | 1.000 | ||

| 1:100, n (%) | 9 (2.80) | 4 (2.84) | |

| ≥1:320, n (%) | 313 (97.20) | 137 (97.16) | |

| C3, g/L, mean ± SD | 0.42 ± 0.21 | 0.51 ± 0.23 | < 0.001* |

| C4, g/L, mean ± SD | 0.08 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | < 0.001* |

| PLT, × 109/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 152 (104, 219) | 123 (77, 195) | 0.002* |

| WBC, × 109/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 4.08 (2.93, 6.17) | 4.33 (3.01, 6.47) | 0.559 |

| Hb, g/L, mean± SD | 98.76 ± 20.45 | 97.99 ± 21.25 | 0.710 |

| CRP, mg/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 3.81 (1.71, 9.17) | 6.09 (3.10, 14.00) | < 0.001* |

| 24-h proteinuria > 0.5 g, n (%) | 173 (53.73) | 67 (47.52) | 0.219 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, M (Q1, Q3) | 121.26 (102.49, 130.62) | 99.66 (72.43, 107.47) | < 0.001* |

| CD19+B cells, %, M (Q1, Q3) | 19.60 (13.90, 28.00) | 17.70 (12.43, 27.05) | 0.171 |

| Systemic involvement | |||

| Fever, n (%) | 47 (14.73) | 8 (5.67) | 0.006* |

| Mucocutaneous, n (%) | 142 (44.10) | 39 (27.66) | < 0.001* |

| Renal involvement, n (%) | 175 (54.35) | 69 (48.94) | 0.283 |

| Vasculitis, n (%) | 21 (6.52) | 4 (2.84) | 0.106 |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 62 (19.25) | 21 (14.89) | 0.260 |

| Serosal, n (%) | 124 (38.51) | 55 (39.01) | 0.919 |

| CNS, n (%) | 27 (8.39) | 7 (4.96) | 0.194 |

| ILD, n (%) | 7 (2.17) | 13 (9.22) | < 0.001* |

| PAH, n (%) | 28 (8.70) | 12 (8.51) | 0.948 |

| Myocarditis, n (%) | 56 (17.39) | 22 (15.60) | 0.636 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 25 (7.76) | 6 (4.26) | 0.164 |

| Thrombotic events, n (%) | 14 (4.35) | 28 (19.86) | < 0.001* |

| Treatments | |||

| GC (max. dosage), n (%) | 0.005* | ||

| Pulse therapy | 57 (17.70) | 15 (10.64) | |

| ≥1 mg/kg/d | 212 (65.84) | 102 (72.34) | |

| 0.5–1 mg/kg/d | 45 (13.98) | 12 (8.51) | |

| < 0.5 mg/kg/d | 7 (2.17) | 9 (6.38) | |

| Unused | 1 (0.31) | 3 (2.13) | |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | 271 (84.16) | 119 (84.40) | 0.949 |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 289 (90.31) | 108 (76.60) | < 0.001* |

| Biologicals, n (%) | 70 (21.74) | 18 (12.77) | 0.024* |

| Combined other CTD | |||

| Sjögren’s syndrome, n (%) | 36 (11.18) | 38 (26.95) | < 0.001* |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome, n (%) | 28 (8.70) | 11 (7.80) | 0.750 |

| Systemic sclerosis, n (%) | 3 (0.93) | 7 (4.96) | 0.016* |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 3 (0.93) | 8 (5.67) | 0.006* |

| ANCA associated vasculitis, n (%) | 2 (0.62) | 4 (2.84) | 0.135 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 38 (11.80) | 43 (30.50) | < 0.001* |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 2 (0.62) | 13 (9.22) | < 0.001* |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 1 (0.31) | 6 (4.26) | 0.005* |

| Tumor, n (%) | 6 (1.86) | 7 (4.96) | 0.120 |

*, statistically significant; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA; anti-Sm, anti-Smith; anti-snRNP, anti-small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; anti-SSA/Ro60, anti-Sjögren syndrome antigen A or Ro60; anti-SSA/ Ro52, anti-Sjögren syndrome antigen A or Ro52; anti-SSB/La, anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen B or La; anti-RPP, anti-ribosomal P protein; anti-β2 GPI, anti-β2-glycoprotein I; ACA, anti-cardiolipin antibody; CRP, C-reactive protein; PLT, platelet count; WBC, white blood cell count; Hb, hemoglobin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CNS, central nervous system; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; GC, glucocorticoids; CTD, connective tissue disease. Notes: Anti-β2 GPI moderate/high titers defined as >40 U/mL. ACA moderate/high titers defined as >40 GPL/MPL (GPL: IgG phospholipid units; MPL: IgM phospholipid units). Renal involvement was defined as 24-hour proteinuria >0.5 g and/or positive renal biopsy. Myocarditis was diagnosed by cardiac magnetic resonance and/or electrocardiogram and/or serum cardiac markers.

Two Distinct Clusters of Late-onset SLE Patients

Our analysis revealed a distinct autoantibody profile in patients with late-onset SLE compared to those with early-onset. Multiple studies demonstrate that distinct autoantibody clusters associate with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes in SLE. To further delineate the phenotypic diversity among late-onset SLE patients, we performed two-step cluster analysis on 12 autoantibodies: ANA, anti-dsDNA, anti-nucleosome, anti-histone, anti-Sm, anti-SSA/Ro52, anti-SSA/Ro60, anti-SSB/La, anti-snRNP, anti-RPP, anti-β2 GPI, ACA. This analysis included 114 patients with late-onset SLE; 27 SLE patients were excluded due to missing data for these auto-antibodies. The cluster analysis identified two distinct patient clusters, with the solution demonstrating moderate cohesion (average silhouette measure = 0.4), which is similar or higher than those reported in several other studies,[11,13,14] indicating a reasonable structure for the clusters.

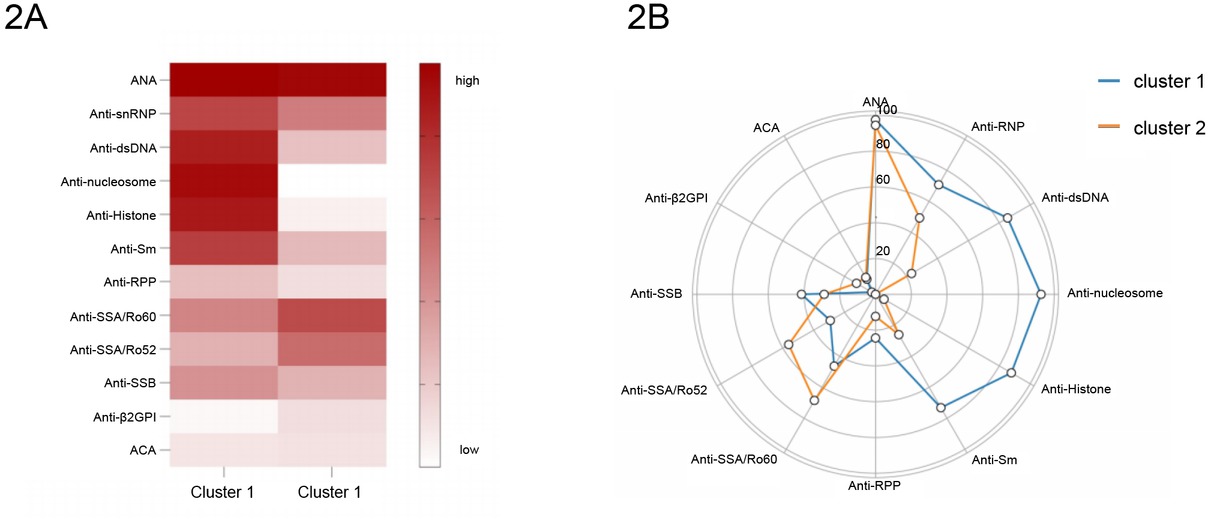

The heatmap in Figure 2A illustrates the two distinct clusters, with bright red indicating high frequencies of a given phenotype and white indicating very low incidences. Cluster 1 (n = 41) exhibited a classical lupus-specific autoreactivity profile characterized by significantly higher frequencies of anti-dsDNA (85.37% vs. 23.29%, P < 0.001), anti-Sm (73.17% vs. 26.03%, P < 0.001), anti-nucleosome (92.68% vs. 0.00%, P < 0.001), and anti-histone antibodies (87.80% vs. 5.48%, P < 0.001) compared to Cluster 2 (n = 73). Conversely, Cluster 2 demonstrated a phenotype with significantly elevated anti-SSA/Ro60 (68.49% vs. 46.34%, P = 0.020) and anti-SSA/Ro52 antibodies (56.16% vs. 29.27%, P = 0.006), Supplementary Table S1, Figure 2B.

A, Autoantibody clusters of patients with Late-onset SLE in the study. Heatmap shows the frequencies for each autoantibody by cluster. B, Radar plots show the frequencies for each autoantibody by cluster.

Cluster 1 demonstrates significant hypocomplementemia, with markedly lower mean C3 (0.39 vs. 0.51 g/L, P = 0.002) and C4 (0.07 vs. 0.11 g/L, P = 0.017) levels compared to Cluster 2. This profound complement consumption signifies more active immune complex-mediated pathogenesis, aligning with their significantly higher systemic disease activity (SLEDAI-2K: 11.8 vs. 8.8, P = 0.004; PGA: 1.5 vs. 1.2, P = 0.003). Cluster 2, while exhibiting less complement activation, shows a significantly higher prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH: 12.33% vs. 0.00%, P = 0.048), ILD (15.07% vs. 2.44%, P = 0.073) and greater association with Sjögren’s syndrome (34.25% vs. 14.63%, P = 0.024), suggesting divergent autoantibody specificities or pathogenetic mechanisms (Table 2).

Baseline parameters and clinical outcomes of patients among autoantibody clusters

| cluster 1 (n = 41) | cluster 2 (n = 73) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Female, n (%) | 33 (80.49) | 55 (75.34) | 0.530 |

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 57.90 ± 7.18 | 59.84 ± 7.82 | 0.115 |

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Disease onset, month, M (Q1, Q3) | 1.13 (0.70, 2.67) | 1.47 (0.77, 3.13) | 0.871 |

| SLEDAI-2K, mean ± SD | 11.8 ± 5.2 | 8.8 ± 5.4 | 0.004* |

| PGA, mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.003* |

| Laboratory and serology | |||

| C3, g/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 0.39 (0.21, 0.55) | 0.51 (0.38, 0.67) | 0.002* |

| C4, g/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.12) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | 0.017* |

| PLT, × 109/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 126.0 (78.0, 195.0) | 121.0 (75.0, 192.0) | 0.682 |

| WBC, × 109/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 3.72 (2.84, 5.21) | 5.14 (3.19, 7.17) | 0.016* |

| Hb, g/L, mean± SD | 95.88 ± 14.99 | 99.27 ± 21.74 | 0.328 |

| CRP, mg/L, M (Q1, Q3) | 8.09 (5.32, 14.55) | 5.50 (3.09, 13.02) | 0.086 |

| 24-hour proteinuria > 0.5 g, n (%) | 21 (51.22) | 26 (35.62) | 0.104 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, M (Q1, Q3) | 102.28 (72.52, 107.29) | 100.66 (83.65, 107.35) | 0.966 |

| Systemic involvement | |||

| Fever, n (%) | 5 (12.20) | 3 (4.11) | 0.215 |

| Mucocutaneous, n (%) | 15 (36.59) | 22 (30.14) | 0.480 |

| Renal involvement, n (%) | 20 (48.78) | 28 (38.36) | 0.279 |

| Vasculitis, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 2 (2.74) | 1.000 |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 10 (24.39) | 11 (15.07) | 0.218 |

| Serosal, n (%) | 19 (46.34) | 29 (39.73) | 0.492 |

| CNS, n (%) | 3 (7.32) | 4 (5.48) | 1.000 |

| ILD, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 11 (15.07) | 0.073 |

| PAH, n (%) | 0 (0.00) | 9 (12.33) | 0.048* |

| Myocarditis, n (%) | 7 (17.07) | 14 (19.18) | 0.781 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 3 (7.32) | 2 (2.74) | 0.504 |

| Thrombotic events, n (%) | 10 (24.39) | 16 (21.92) | 0.763 |

| Treatments | |||

| GC (max. dosage), n (%) | 0.065 | ||

| Pulse therapy | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.37) | |

| ≥1 mg/kg/d | 4 (9.76) | 11 (15.07) | |

| 0.5–1 mg/kg/d | 36 (87.80) | 48 (65.75) | |

| < 0.5 mg/kg/d | 1 (2.44) | 6 (8.22) | |

| Unused | 0 (0.00) | 7 (9.59) | |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | 32 (78.05) | 65 (89.04) | 0.114 |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 35 (85.37) | 55 (75.34) | 0.208 |

| Biologicals, n (%) | 7 (17.07) | 7 (9.59) | 0.243 |

| Combined other CTD | |||

| Sjögren’s syndrome, n (%) | 6 (14.63) | 25 (34.25) | 0.024* |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome, n (%) | 4 (9.76) | 7 (9.59) | 1.000 |

| Systemic sclerosis, n (%) | 0 (0.00) | 6 (8.22) | 0.147 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 2 (2.74) | 1.000 |

| ANCA associated vasculitis, n (%) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (5.48) | 0.319 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 7 (17.07) | 22 (30.14) | 0.124 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (12.20) | 4 (5.48) | 0.361 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 4 (5.48) | 0.776 |

| Tumor, n (%) | 1 (2.44) | 4 (5.48) | 0.776 |

*, statistically significant; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000; PGA, Patient Global Assessment; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4; PLT, platelet count; WBC, white blood cell count; Hb, hemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CNS, central nervous system; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; GC, glucocorticoids; CTD, connective tissue disease.

Discussion

This study delineates the distinct phenotype of newly diagnosed late-onset SLE compared to early-onset disease. We chose age 50 as the cutoff for late-onset based on its common use in the literature,[2,4,15, 16, 17, 18] which approximates the menopausal transition and the onset of immune aging. We acknowledge that this choice is somewhat arbitrary- indeed, some studies have proposed 60 as an alternative threshold[19] -and that any dichotomous cutoff on a continuous variable has limitations. Studies show SLE varies by age of onset. Early-onset is more severe. Late-onset has more pulmonary/ serositis involvement but less malar rash, photosensitivity, arthritis, and nephritis.[7,20,21] To address whether alternative age thresholds would alter our conclusions, we conducted a subgroup analysis comparing patients aged 50–60 years (n = 85) versus > 60 years (n = 56) within our late-onset SLE cohort. We found that while there were expected differences in age-related comorbidities (e.g., coronary heart disease) and slight variations in disease activity scores, the core clinical, serological, and organ-involvement profiles remained largely consistent across the two age subgroups. Notably, autoantibody patterns—central to our cluster analysis—did not differ significantly (Supplementary Table S2). These findings reinforce that using 50 years as the cutoff captures a phenotypically distinct group consistent with the literature, and supports the robustness of our identified clusters.

In alignment with previous reports, our study also confirmed that juvenile-onset SLE tends to present with a more severe phenotype, late-onset SLE demonstrated attenuated disease activity, reduced classic manifestations (such as mucocutaneous involvement), and distinct serological profiles compared to early-onset disease. This attenuated clinical presentation contributed to a significant diagnostic delay (median 1.47 vs. 1.03 months, P = 0.002). For instance, Cervera et al. described reduced renal involvement in late-onset SLE (22% vs. 41% in early-onset) and limited pulmonary manifestations (9%) in this subgroup.[22] These findings appear partly consistent with observations from a Korean cohort which reported a relatively low proportion (13.5%) of lupus nephritis (LN) among late-onset patients.[4] In our study found a substantial proportion of late-onset patients presented with LN (69/141, 48.94%). However, this rate was not significantly different from that in the early-onset group within our cohort (54.35%, P = 0.283), suggesting that the risk of renal involvement in Chinese SLE patients may persist into older age. The marked discrepancy in late-onset LN prevalence suggests potential ethnic variations and underscores the imperative for vigilant renal monitoring across all age groups in Chinese SLE patients.

Consistent with previous reports,[2,23,24] our study confirms a higher burden of comorbidities in patients with late-onset SLE. After multivariate adjustment for age, only diabetes mellitus remained independently associated with late-onset SLE (P = 0.005). However, the notably wide confidence interval suggests limited. After multivariate adjustment for age, only diabetes mellitus remained independently associated with late-onset SLE (P = 0.005) precision in this estimate, likely due to the small number of events, and thus this finding should be interpreted with caution. In contrast, the increased prevalence of hypertension appeared to be primarily driven by advancing age itself rather than by late-onset SLE status. Although numerically more cases of coronary heart disease were observed in the late-onset group, the low event count precluded stable multivariate modeling, Supplementary Table S3. These observations highlight the need for further validation in larger prospective cohorts to better delineate the independent contributions of age and SLE phenotype to comorbidity profiles. Notably, ILD occurred significantly more frequently (9.22% vs. 2.17%, P < 0.001), potentially related to advancing age, immunosenescence, and an association with SLE-Sjögren’s overlap syndrome conferring higher ILD risk in this subgroup.[18] These findings highlight the more complex comorbidity burden, distinct organ manifestation patterns (particularly increased ILD), and different therapeutic approaches in late-onset SLE.

Critically, this study demonstrates that late-onset SLE encompasses at least two distinct phenotypic clusters—revealed through our cluster analysis as divergent subgroups masked within the aggregate profile—a novel finding underscoring the disease’s heterogeneity in older adults. Our “lupus-dominant” cluster (Cluster 1) essentially mirrors younger-onset SLE in its clinical and serologic intensity, while our “comorbidity-dominant” cluster (Cluster 2) suggests a syndrome in which age-related health conditions are the prevailing feature and classical SLE manifestations are attenuated. This dual nature is not entirely unexpected: older SLE patients are known to present more subtly, and it is well established that comorbidities accumulate with age. However, by formally identifying clusters, we extend prior knowledge by showing that there is a subgroup of late-onset patients for whom comorbid conditions effectively eclipse lupus symptoms.

Cluster 1 was characterized by specific autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm) and hypocomplementemia, reflecting a pathogenesis driven by immune complex (IC) deposition and type I interferon (IFN) pathway activation.[25,26] These autoantibodies—highly specific for SLE—form pathogenic ICs that deposit in tissues such as the kidney, activate complement (accounting for low C3/C4), and exacerbate inflammation, leading to severe organ manifestations.[27] This mechanism, which relies on adaptive immunity involving T and B cell collaboration,[28] indicates that a strong lupus-specific autoimmune drive persists in this late-onset subgroup, overriding age-related immunosenescence. Cluster 2 was characterized by a higher prevalence of anti-SSA/Ro antibodies, Sjögren’s syndrome, ILD, and PAH, alongside relatively mild lupus activity. The anti-Ro52 antibody—which is frequently associated with rapidly progressive ILD and poor prognosis in autoimmune diseases such as idiopathic inflammatory myopathy-associated interstitial lung disease (IIM-ILD)—may reflect a shared immunopathogenic mechanism.[29] Mechanistically, anti-Ro52 is closely linked to robust type I interferon activation, promoting innate immune-mediated damage in lung and vascular tissues, thereby contributing to the prominent cardiopulmonary manifestations observed in this cluster. This phenotype is further supported by findings from the Chinese SLE Treatment and Research Group (CSTAR) registry, in which both anti-SSA positivity and older age at onset independently predicted organ damage accumulation in SLE patients.[30] These results suggest that Cluster 2 represents a high-risk subgroup within late-onset SLE, necessitating vigilant monitoring for progressive organ damage—particularly cardiopulmonary complications.

Recognizing this distinction is clinically critical, as it directly informs therapeutic strategy. Patients in the lupus-dominant cluster likely require more aggressive, lupus-specific therapy tailored to particular organ involvement. In contrast, patients in the comorbidity-dominant cluster may benefit from a conservative approach to immunosuppression, coupled with proactive management of age-related comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and geriatric syndromes. Although these comorbidities are often not SLE-specific, their high prevalence in late-onset patients necessitates careful management to avoid overtreatment. Importantly, older patients frequently exhibit reduced tolerance to immunosuppressive agents; our clustering helps contextualize this by identifying which patients may still require standard lupus regimens versus which patients warrant individualized, lower-intensity therapy. The overarching goal remains to balance treatment—avoiding both inadequate control of lupus activity and excessive intervention that may worsen comorbidities.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and dependence on available clinical data. Unmeasured confounders could influence cluster formation. Additionally, our cohort size (and that of some clusters) was modest, which highlighs the challenge of recruiting large late-onset SLE cohorts due to diagnostic delays and heterogeneity. While our clustering approach achieved moderate separation (silhouette score = 0.4), smaller sample sizes may limit the stability of subgroup identification. Nonetheless, the consistency of our clusters with known SLE subgroups, and the novelty of applying cluster analysis to a late-onset cohort, lend credibility to the findings.

Conclusions

In summary, our analysis of a late-onset SLE study reveals a “dual nature” of the disease in older adults. One subgroup of patients has a clinical profile much like younger-onset lupus, with prominent SLE-specific manifestations, while another subgroup’s profile is dominated by age-related comorbidities and relatively mild lupus activity. This phenotypic heterogeneity has important implications: it suggests that late-onset SLE should not be treated as a single entity, and that clinical management should be personalized according to the patient’s dominant phenotype. By delineating these clusters, we clarify the scientific understanding of SLE across the lifespan and emphasize the need for age-tailored approaches in both research and care.

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Chinese National Key Technology R&D Program (2021YFC2501305).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the staff physicians and nurses for providing care to the patients with SLE.

-

Supplementary information

Supplementary materials are only available at the official site of the journal (www.rir-journal.com).

-

Author contributions

F. Lu: evaluated patients, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. D. Li and X. Sun: collected data, performed data entry and supervised statistical analysis. Q. Wang and C. Ouyang: designed and lead the study, evaluated patients, reviewed the draft.

-

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University (Ethics Approval No. 2024-SR-221).

-

Informed consent

All patients provided informed consent.

-

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

-

Use of large language models, AI and machine learning tools

None declared.

-

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Piga M, Tselios K, Viveiros L, et al. Clinical patterns of disease: From early systemic lupus erythematosus to late-onset disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2023;37:101938.10.1016/j.berh.2024.101938Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Riveros Frutos A, Holgado S, Sanvisens Bergé A, et al. Late-onset versus early-onset systemic lupus: characteristics and outcome in a national multicentre register (RELESSER). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:1793–1803.10.1093/rheumatology/keaa477Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Sohn IW, Joo YB, Won S, et al. Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Is it “mild lupus”? Lupus. 2018;27:235–242.10.1177/0961203317716789Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Kang JH, Park DJ, Lee KE, et al. Comparison of clinical, serological, and prognostic differences among juvenile-, adult-, and late-onset lupus nephritis in Korean patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1289–1295.10.1007/s10067-017-3641-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.10.1002/art.1780400928Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677–2686.10.1002/art.34473Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.10.1164/rccm.2009-040GLSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. Linee guida ESC/ERS 2022 per la diagnosi e il trattamento dell’ipertensione polmonare [2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2023;24:e1-e116.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Dafna D Gladman, Dominique Ibañez, Murray B Urowitz. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:288–291.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Piga M, Chessa E, Morand EF, et al. Physician Global Assessment International Standardisation COnsensus in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: the PISCOS study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4:e441–e449.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhao DT, Yan HP, Liao HY, et al. Using two-step cluster analysis to classify inpatients with primary biliary cholangitis based on autoantibodies: A real-world retrospective study of 537 patients in China. Front Immunol. 2023;13:1098076.10.3389/fimmu.2022.1098076Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Artim-Esen B, Çene E, Şahinkaya Y, et al. Cluster analysis of autoantibodies in 852 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from a single center. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1304–1310.10.3899/jrheum.130984Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Tischendorf T, Geithner S, Schaal T. Views on the well-being of groups of informal caregivers. A cluster analysis using the example of Saxony. BMC Nurs. 2024;23:912.10.1186/s12912-024-02576-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Yinon R, Shaul S. Cognitive-Linguistic Profiles Underlying Reading Difficulties Within the Unique Characteristics of Hebrew Language and Writing System. Dyslexia. 2025;31:e1799.10.1002/dys.1799Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Ambrose N, Morgan TA, Galloway J, et al. Differences in disease phenotype and severity in SLE across age groups. Lupus. 2016;25:1542–1550.10.1177/0961203316644333Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Choi JH, Park DJ, Kang JH, et al. Comparison of clinical and serological differences among juvenile-, adult-, and late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Korean patients. Lupus. 2015;24:1342–1349.10.1177/0961203315591024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Alonso MD, Martinez-Vazquez F, de Teran TD, et al. Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Northwestern Spain: differences with early-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and literature review. Lupus. 2012;21:1135–1148.10.1177/0961203312450087Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Medlin JL, Hansen KE, McCoy SS, et al. Pulmonary manifestations in late versus early systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48:198–204.10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Viveiros L, Neves A, Gouveia T, et al. A large cohort comparison of very late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with younger-onset patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2024;42:1480–1486.10.55563/clinexprheumatol/jgsyosSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Wilson HA, Hamilton ME, Spyker DA, et al. Age influences the clinical and serologic expression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:1230–1235.10.1002/art.1780241002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Livingston B, Bonner A, Pope J. Differences in clinical manifestations between childhood-onset lupus and adult-onset lupus: a meta-analysis. Lupus. 2011;20:1345–1355.10.1177/0961203311416694Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] R Cervera, M A Khamashta, J Font, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. The European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113–124.10.1097/00005792-199303000-00005Search in Google Scholar

[23] Prevete I, Iuliano A, Cauli A, et al. Similarities and differences between younger and older disease onset patients with newly diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41:145–150.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Sassi RH, Hendler JV, Piccoli GF, et al. Age of onset influences on clinical and laboratory profile of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:89–95.10.1007/s10067-016-3478-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Kato Y, Park J, Takamatsu H, et al. Apoptosis-derived membrane vesicles drive the cGAS-STING pathway and enhance type I IFN production in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1507–1515.10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-212988Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Chasset F, Ribi C, Trendelenburg M, et al. Identification of highly active systemic lupus erythematosus by combined type I interferon and neutrophil gene scores vs classical serologic markers. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3468–3478.10.1093/rheumatology/keaa167Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Sturfelt G, Truedsson L. Complement in the immunopathogenesis of rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:458–468.10.1038/nrrheum.2012.75Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Arnaud L, Chasset F, Martin T. Immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: An update. Autoimmun Rev. 2024;23:103648.10.1016/j.autrev.2024.103648Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Gui X, Shenyun S, Ding H, et al. Anti-Ro52 antibodies are associated with the prognosis of adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathy-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61:4570–4578.10.1093/rheumatology/keac090Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Wang Z, Li M, Ye Z, et al. Long-term Outcomes of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Multicenter Cohort Study from CSTAR Registry. Rheumatol Immunol Res. 2021;2:195– 202.10.2478/rir-2021-0025Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 Fengyun Lu, Dongyu Li, Xiaoxuan Sun, Qiang Wang, Chun Ouyang, published by De Gruyter on behalf of NCRC-DID

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review

- Crystal deposition disease of the shoulder at uncommon sites: Diagnostic challenges and nomenclature issues in the absence of synovial fluid analysis

- Original Article

- Features of IgG4-related sclerosing mesenteritis: A Chinese cohort study and literature review

- CD209 gene polymorphism and its clinical correlation with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis among Egyptian patients: A case-control study

- Unveiling the dual nature of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: A cross-sectional study

- Letter to the Editor

- The mystery of the blue toe

- Spondyloarthritis recognition for primary care: A simplified diagnostic and referral pathway for general physicians

- Development and validation of the manual disease activity score (MDAS) for rheumatoid arthritis

- Images

- Hemorrhage or thrombosis? Adrenal involvements in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome

Articles in the same Issue

- Review

- Crystal deposition disease of the shoulder at uncommon sites: Diagnostic challenges and nomenclature issues in the absence of synovial fluid analysis

- Original Article

- Features of IgG4-related sclerosing mesenteritis: A Chinese cohort study and literature review

- CD209 gene polymorphism and its clinical correlation with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis among Egyptian patients: A case-control study

- Unveiling the dual nature of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: A cross-sectional study

- Letter to the Editor

- The mystery of the blue toe

- Spondyloarthritis recognition for primary care: A simplified diagnostic and referral pathway for general physicians

- Development and validation of the manual disease activity score (MDAS) for rheumatoid arthritis

- Images

- Hemorrhage or thrombosis? Adrenal involvements in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome