Dear Editor,

Late-onset rheumatoid arthritis (LORA) refers to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in individuals aged 60–65 or older, representing 10%–30% of the total RA population. The increasing of life expectancy over the last two decades will turn LORA a more prominent form of RA. The goal of treating LORA remains consistent with that for younger patients, however, there are several challenges linked with the diagnosis and management of this disease: the need to ruling out other conditions with similar clinical presentations; the absence of specific guidelines for treating RA in this age group; as well as the complexity of selecting appropriate therapies for these patients. The authors believe it is of utmost importance to address issues related to the diagnosis and management of LORA, considering the increasing prevalence of this condition and the absence of specific guidelines for it. We present a case of a patient with LORA to illustrate the difficulties in its management. We believe that more attention should be given to this topic to assist other healthcare professionals who may need to address it and to encourage further research in this area.

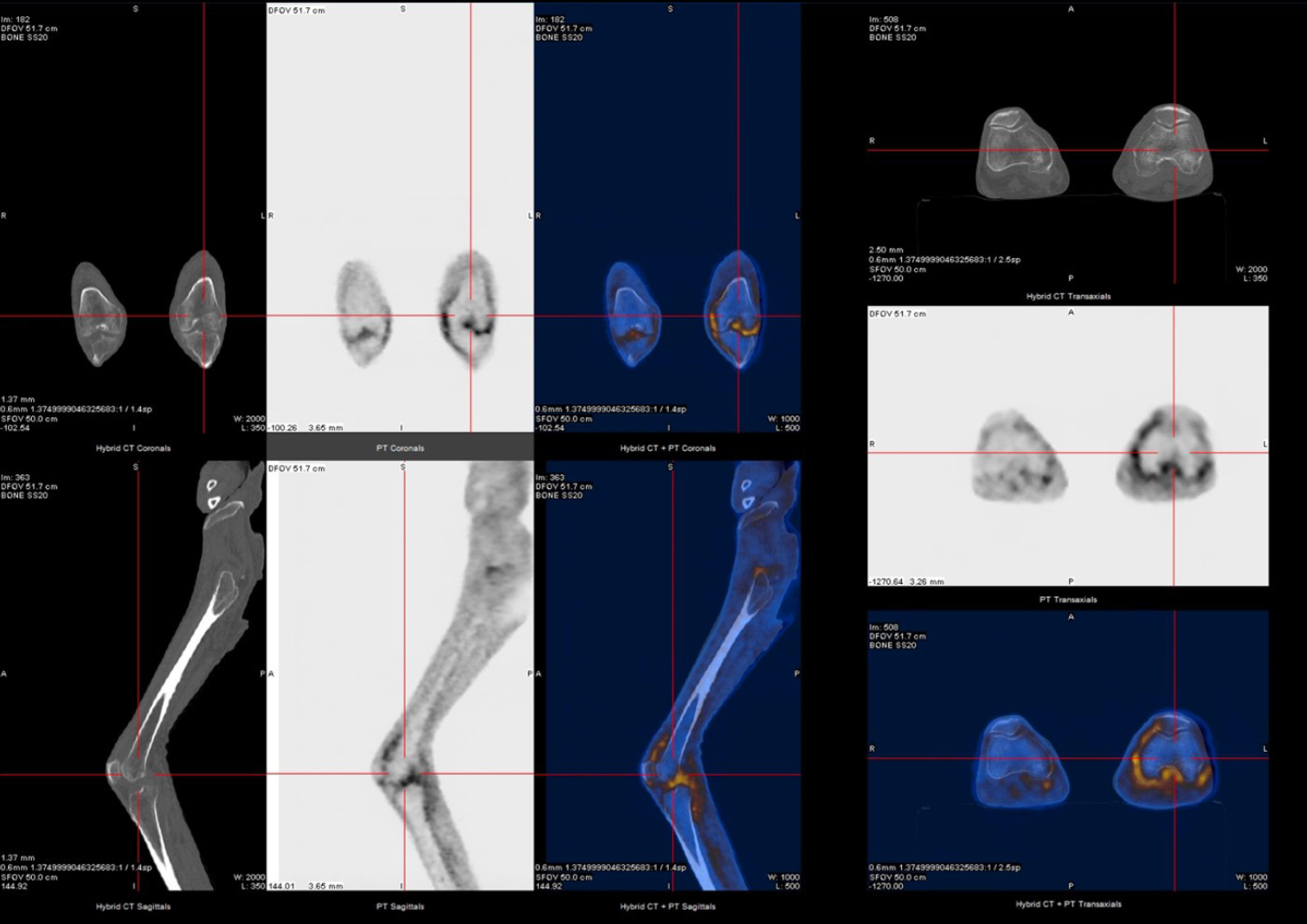

A 76-year-old man with hypertension and hypothyroidism went to the Emergency Department (ED) due to a 3-months history of weight loss (15% of the total body weight), asthenia and 1-hour morning stiffness. He reported no fever or night sweats. General examination revealed poor tolerance to any activity, severe muscle mass loss was evident; Body mass index (BMI) was 19.1 kg/m2. Several joints were painful, with symmetrical synovitis of the knees, elbows, wrists, proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints (Figure 1 demonstrate the impairment to the hand’s joints). Blood levels revealed inflammatory anemia (Hemoglogin 7.6 g/dL, reference range 12–15) and high inflammatory biomarkers (Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 96 mm/h, reference range 0–25; C-reactive protein 97.7 mg/dL, reference range 0–5; ferritin 757 μg/L, reference range 2.2–178). Blood and urine cultures were negative, and human immunodeficiency, B/C hepatitis viruses and syphilis serologies were negative too. Thyroid function were normal. Transthoracic echocardiogram excluded endocarditis. Full body computed tomography, positron emission tomography, upper and lower digestive endoscopies excluded neoplastic causes. The study was complemented with rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP), both elevated (279.9 UI/mL, reference range 0–20, and 435 UI/mL, reference range 0–20, respectively).

Radiographs of the hands (posteroanterior, superior; oblique, inferior).

A very active and systemic LORA was assumed, and the patient started on systemic corticosteroids and methotrexate. Initial clinical response was observed with clinical improvement. Nevertheless, a septic left knee arthritis with bacterie-mia led to a long hospital stay (Figure 2). It was resolved after temporary suspension of immunosuppressive therapy, surgery and intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy. After restarting immunosuppressive therapy, he was admitted to the immunology outpatient clinic for follow-up and started ambulatory motor rehabilitation. However, he soon returned to the ED due to diarrhea, mucositis and pancytopenia secondary to methotrexate toxicity, possibly due to erroneous intake. The condition was resolved after discontinuation of the drug, but a rapid worsening of the arthritis lead to IV infliximab initiation to assure correct drug administration. Six months after infliximab initiation the patient is on clinical remission under outpatient follow-up.

18F-FDG and PET-CT study reveals slightly increased uptake of FDG in the knee joints (more in the left knee joint, with apparent extension to the subquadricipital synovial bursa region). PET-CT, pistron emission tomography-computed tomography.

In brief, patients with LORA will differ from patients with early--onset RA in several aspects and should have a personalized therapeutic approach. Clinical presentation is often more acute and severe, with involvement of large joints, higher disease activity and functional impairment. Constitutional symptoms can be the predominant feature, mimicking neoplasms or occult infections, and delaying the correct diagnosis due to the necessary investigational steps to exclude these entities.[1,2,3,4,5] The treatment objectives are transversal in all cases of RA. However, elderly patients often experience more comorbidities and a higher incidence of adverse drug reactions. There are no specific treatment guidelines to LORA and, although the current RA guidelines advocate conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) as first-line therapies, in these group of patients, early biological drugs should be considered. Not only due to the several specific RA poor prognostic factors presented in LORA patients, but also because of the potential of csDMARDs to worsen chronic diseases. This clinical case illustrates some of these subjects. The data regarding the use of biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (b/tsDMARDs) in elderly patients are limited. However, they appear to be as effective and well-tolerated in these patients as in those with early-onset RA. Some literature indicates that b/tsDMARDs do not exhibit higher rates of side effects when compared to csDMARDs. In this case, IV Infliximab (TNF-α inhibitor) turned out to be a logic option, controlling as early as possible the LORA activity.[6,7,8,9,10]

Our clinical case highlights how LORA clinical and therapeutic approach can be challenging. A high level of suspicion and early action are essential to delay the progression of the disease and its many complications.

Funding statement: None.

Acknowledgement

None.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: ARC, IC, SRM, TF; Writing—Original draft preparation: ARC, SRM, TF; Writing—Reviewing and Editing: ARC, SRM, TF; Conceptualization, Supervision: SRM, TF; Supervision, Project administration: TF.

-

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

-

Ethical Statement

Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

-

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

References

[1] Serhal L, Lwin MN, Holroyd C, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in the elderly: Characteristics and treatment considerations. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102528.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Kojima M, Kawahito Y, Sugihara T, et al. Late-onset rheumatoid arthritis registry study, LORIS study: study protocol and design. BMC Rheumatol. 2022;6:90.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Zhang M, Feng M, Lai B. The comprehensive geriatric assessment of an older adult with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol & Autoimmun 2022;2:102–104.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Kobak S, Bes C. An autumn tale: geriatric rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2018;10:3–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Korkmaz C, Yildiz P. Giant cell arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, and late-onset rheumatoid arthritis: Can they be components of a single disease process in elderly patients? Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4:157–160.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Novella-Navarro M, Balsa A. Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis in Older Adults: Implications of Ageing for Managing Patients. Drugs Aging. 2022;39:841–849.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bergstra SA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:3–18.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Koh JH, Lee SK, Kim J, et al. Effectiveness and safety of biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis: real-world data from the KOBIO Registry. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:269–278.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Sugihara T, Ishizaki T, Onoguchi W, et al. Effectiveness and safety of treat-to-target strategy in elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a 3-year prospective observational study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:4252–4261.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Akter R, Maksymowych WP, Martin ML, et al. Outcomes with Biological Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (bDMARDs) in Older Patients Treated for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23:184–189.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 Ana Rubim Correia, Inês Clara, Sara Raquel Martins, Tomás Fonseca, published by De Gruyter on behalf of NCRC-DID.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Early diagnosis and standardized treatment are critical to improve the prognosis of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis

- Guideline and Consensus

- Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of Takayasu’s arteritis (2023)

- Review

- The effect of anti-TNF drugs on the intestinal microbiota in patients with spondyloarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel diseases

- What can patients tell us in Sjögren’s syndrome?

- Amyopathic dermatomyositis may be on the spectrum of autoinflammatory disease: A clinical review

- Original Article

- Adalimumab in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Results from a Delphi investigation

- Clinical implications of seropositive and seronegative autoantibody status in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A comparative multicentre observational study

- Images

- The vanishing touch: Unveiling the tuft erosion in scleroderma

- Letter to the Editor

- Not all geriatric cachexia is cancer – The difficult lateonset rheumatoid arthritis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Early diagnosis and standardized treatment are critical to improve the prognosis of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis

- Guideline and Consensus

- Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of Takayasu’s arteritis (2023)

- Review

- The effect of anti-TNF drugs on the intestinal microbiota in patients with spondyloarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel diseases

- What can patients tell us in Sjögren’s syndrome?

- Amyopathic dermatomyositis may be on the spectrum of autoinflammatory disease: A clinical review

- Original Article

- Adalimumab in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Results from a Delphi investigation

- Clinical implications of seropositive and seronegative autoantibody status in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A comparative multicentre observational study

- Images

- The vanishing touch: Unveiling the tuft erosion in scleroderma

- Letter to the Editor

- Not all geriatric cachexia is cancer – The difficult lateonset rheumatoid arthritis