A review: evaluating methods for analyzing kidney stones and investigating the influence of major and trace elements on their formation

-

Fidan Suleman Muhammed

, Aryan Fathulla Qader

, Rzgar Faruq RashidIman

Abstract

Kidney stone disease is a global concern, and its prevalence is increasing. The objective of this review is to provide a thorough analysis of the many analytical techniques used in the study of kidney stones and to investigate the significance of major and trace components in the development of kidney stone formation. The samples included organic (uric acid) and inorganic (calcium oxalate and carbonate apatite). To study kidney stone analysis methods like XRD, FTIR, SEM, and ICP-MS, a systematic literature review was conducted. The quantities and effects of main (calcium, oxalate, phosphate) and trace (magnesium, zinc, copper) elements in kidney stone development were also examined. The review shows that XRD and FTIR are best for evaluating kidney stone crystalline structure and content, whereas SEM gives rich morphological insights. Its trace element detection sensitivity makes ICP-MS unique. Calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate, the most common components, affect kidney stone development. Trace elements like magnesium prevent stone formation, whereas zinc and copper may encourage crystallisation. Results revealed significantly higher calcium levels in inorganic components compared to organic ones. Uric acid stones exhibited lower element content except for copper and selenium, likely originating from the liver. Carbonate apatite stones showed higher element concentrations, particularly magnesium, compared to calcium oxalate stones. Principal component analysis (PCA) identified three principal components, explaining 91.91 % of the variance. These components reflected specific co-precipitation processes of elements, with distinct distributions among different stone types. This variability in element content among stone types could serve as valuable guidance for patient dietary considerations.

1 Introduction

Kidney stone disease poses a significant global health concern and has a profound impact on human well-being. It is prevalent among the populations of developed nations. 1 , 2 The incidence of kidney stone diseases has increased. Since the 1990s, the proportion of individuals afflicted with kidney stones has doubled, rising from 5 % to 10 % of the population. 3 Kidney stones result from an abnormal biomineralization process within the urinary system, and typically consist of combinations of two or more components. 4 This condition has multiple contributing factors and is influenced by the physical and chemical conditions within the urinary system. 4 Kidney stones can induce severe pain in patients and may also exacerbate renal function, potentially leading to permanent kidney impairment. 5 , 6 Nevertheless, uncertainties persist regarding the causes and elemental dynamics involved in the formation of kidney stones. 7 Typically, kidney stones arise from pathological biomineralization processes, resulting in compositions consisting of one or more complex components, including calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and uric acid. 8 Previous research indicates that the development of kidney stones is directly influenced by geological factors, dietary patterns, and hydrological conditions, including water hardness. 9 Multiple processes contribute to the formation of kidney stones, leading to the supersaturation of ionic constituents and the subsequent development of distinct types of stones. 10 , 11 Thus, investigating kidney stones from an elemental standpoint becomes essential for understanding their pathophysiology and advancing techniques for treatment and prevention. 12 In recent times, significant attention has focused on the roles and significance of major and trace elements in biominerals. 13 Earlier research utilizing X-ray spectral microanalysis has indicated that specific elements influence the development and growth of kidney stones. 14 These elements can either enhance or hinder crystal nucleation by interacting with the crystalline surface. 15 In addition, analyzing the chemical and mineral composition of kidney stones is crucial for accurate diagnosis. 16 For instance, lead contamination is consistently associated with environmental factors. 17 Consequently, this study examined the major and trace elements present in various kidney stone types from patients in Beijing. The goal was to explore relationships among these elements and offer recommendations for patient intake based on their specific stone types.

2 Kidney function

The kidneys are critical organs that carry out a number of duties that are absolutely necessary. Examining the functions of the kidneys, such as filtering blood, maintaining electrolyte balance, controlling blood pressure, and releasing hormones, is necessary for gaining an understanding of renal function. 18 The kidneys perform the function of filtering blood to eliminate waste materials and surplus chemicals. The renal arteries transport blood into the kidneys, where it then flows via the nephrons, which are the kidneys’ functional components, waste products, excess salts, and water are filtered out of the blood and form urine, which is excreted from the body. 19 The kidneys play a crucial role in regulating the equilibrium of electrolytes, including sodium, potassium, calcium, and phosphate, within the bloodstream. Their role is to regulate the excretion or reabsorption of these electrolytes in order to maintain optimal cellular function and overall fluid balance. 20 The kidneys excrete hydrogen ions and resorb bicarbonate from urine to maintain bodily acid-base balance. This control keeps blood pH within a small range for appropriate cellular activity. 21 The kidneys control blood pressure using the RAAS. When blood pressure lowers, the kidneys release renin, which produces angiotensin II, a strong vasoconstrictor, and increases aldosterone. 22 The kidneys produce erythropoietin, which increases bone marrow red blood cell synthesis. This function is essential for blood oxygenation. 22 Blood is detoxified by the kidneys by eliminating metabolic waste and pollutants. They also reduce waste toxicity before excretion. 23 The kidneys metabolise vitamin D into its biologically active form, known as calcitriol, which plays a crucial role in the absorption of calcium and the maintenance of bone health. 23

3 Types of kidney stones

There are four types of kidney stones based on their composition: 24 , 25

Calcium Stones: These are the most common type of kidney stones. They can be further divided into two subgroups:

Calcium Oxalate Stones: These stones have an envelope- or dumbbell-shaped appearance. They account for 61 % of all kidney stones and can occur at any age, with a mean presentation in the late 40s. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1, and the recurrence rate is 38 %.

Calcium Phosphate Stones: These stones appear as amorphous or wedge-shaped rosettes. They make up 15 % of all kidney stones and typically present in the early 40s. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1:2, and the recurrence rate is 43 %.

Uric Acid Stones: These stones have a rhomboid-shaped appearance. They constitute 10 %–15 % of all kidney stones and are most frequently seen in individuals aged 60–65 years. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 4:1.

Struvite Stones (also known as triple phosphate or magnesium ammonium phosphate stones): These stones have a coffin-lid-shaped appearance. They account for 5 %–15 % of all kidney stones and can occur at any age, with a mean presentation in the early 50s. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1:3, and the recurrence rate is 41 %.

Cystine Stones: These stones are hexagon-shaped. They are rare, constituting only 1 %–2 % of all kidney stones. Cystine stones are most frequently observed in individuals aged 0–20 years. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1, and the recurrence rate is remarkably high at 89 %

4 The role of trace elements in the development of kidney stones

The pathogenesis of kidney stones involves various mechanisms that occur in urine, which is supersaturated with respect to the ionic constituents of the specific stone. These mechanisms lead to the formation of kidney stones. Although significant progress has been made in understanding the factors contributing to kidney stone formation, questions remain about the role of trace elements. Some studies suggest that major and trace elements play a role in the initiation of stone crystallization, either as a nucleus or nidus for stone formation or as contaminants within the stone structure. Analyzing kidney stones is essential to comprehend the contribution of trace constituents and formulate strategies for treatment and prevention 10 as shown in Table 1.

Urinary stone promoters and inhibitors.

| Promoters | Inhibitors | |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic | Organic | |

| Calcium (Ca) Oxalate Urate Cystine Low urine pH Low urine flow Bacterial products |

Magnesium (Mg) Citrate Pyrophosphate |

Nephrocalcin Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP) Urinary prothrombin fragment 1 Protease inhibitor: inter-alfainhibitor Glycosaminoglycans Osteopontin (uropontin) Other bikunin, calgranulin High urine flow |

Trace elements, including zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), aluminum (Al), strontium (Sr), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb), play a significant role in kidney stone formation. These elements form poorly soluble salts with phosphate and oxalate ions, contributing to the crystallization process. 10 Researchers have demonstrated that magnesium (Mg), aluminum (Al), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and copper (Cu) exhibit an inhibitory effect on the growth of calcium oxalate crystals, even at very low concentrations (Table 2). These trace elements play a crucial role in modulating the crystallization process and influencing the external morphology of growing crystals. 105 Munoz and Valiente 63 studied the impact of various trace elements on preventing the crystallization of calcium oxalate, marking significant progress in understanding the development of urinary stones Munoz and Valiente. 63 Meyer and Angino 42 examined the levels of trace metals in calcium oxalate and a combination of calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate. They investigated the inhibitory effects of these trace metals on the growth of crystals of calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate. Other scientists have also studied the impacts of trace elements on solubility and crystallization. There has been a growing interest in determining the levels of trace elements in humans Meyer and Angino. 42 A wide array of trace elements has been quantified in kidney stones, urine, and serum. In some instances, efforts have been made to correlate these measurements with the process of stone formation. 106

Presents the potential roles of various major and trace elements implicated in kidney stone formation, along with recent references supporting these roles.

| Elements | Issue studied related to kidney stones | References | Role in lithogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca) | –High Ca intake has been associated with a lower risk for kidney stones. –Ca is the predominant element in stones which influences the distribution trace elements. Ca ion promotes the formation and growth of intrarenal crystals. –Higher concentration of Ca has been observed in the center, shell and surface parts of the kidney stones. |

(Bihl and Meyers); (Stoller and Meng); (Haghighatdoost et al.)

26

,

27

,

28

Basavaraj et al. 29 Dornbier et al. 30 Huang et al. 31 Joost and Tessadri 32 Ghashghaei and Barbas 33 Schubert 34 Chaudhri et al. 35 |

Ca plays an important role in lithogenesis |

| Magnesium (Mg) | –Mg is the fourth most abundant element in the body; only 1 % of total Mg is found in blood and the rest is present in combination with Ca and P. –In vitro studies have demonstrated decreased nucleation and growth of calcium oxalate crystals in the presence of super physiological concentrations of Mg. –Supplementation with Mg and vitamin B6 significantly lowers the risk of kidney stone formation. –Low concentration ofMg in urine is a risk factor for kidney stone formation. –Dietary Mg deficiency causes experimental urolithiasis, and high levels of this element in urine reduce the concentration of oxalate available for calcium oxalate precipitation. –Mg inhibits calcium oxalate crystallization in human urine and it also inhibits absorption of dietary oxalate from the gut lumen. |

Escott-Stump

36

Ali 37 Domínguez 38 Kohri et al. 39 Johansson and Wedborg 40 Durak et al. 41 Meyer and Angino 42 Scott and Medioli 43 Anderson 44 Cupisti et al. 45 Ormanji et al. 46 |

Mg acts as a potential inhibitor in formation of kidney stones. |

| Manganese (Mn) | –Mn is associated with bone development and plays an important role in the metabolic pathway of amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates and proteins. –Mn levels have been found to be lower in the serum and urine of stone patients than in healthy people. –Low level of Mn might interfere with the fragility of urinary stones in extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) therapy. –It was suggested that Mn as well as other elements, such as Ni, Li and Cd, could be of significance in the pathological mechanism of stone formation. |

Fraga et al.

47

Lall and Kaushik 48 Turgut and Turgut 49 (Hofbauer et al.; ElBaset et al.) 50 , 51 |

Role of Mn in kidney stone formation is still not clear. |

| Copper (Cu) | –Cu is an antioxidant and its highest concentration is found in the liver, kidney, heart and brain. Chronic (long-term) effect of Cu exposure can damage the liver and kidney. –It was firstly pointed out by Bird et al. (1963) that Cu shows the inhibitory effect on the mineralization process of rachitic rats’ cartilage. –Cu and Mn urinary levels were found to be lower in stone formers than in normal subjects. –The inhibitory activity of Cu against growth of calcium phosphate crystals was observed, but not on oxalate. –It has been observed that the amount of Cu stored in the stones is more relevant when compared to Zn, especially in oxalate stones. |

Task

52

Bird and Thomas Jr 53 Wrissenberg 54 Abdel-Gawad et al. 55 Shen et al. 56 Joost and Tessadri 32 Shaltout et al. 57 Barker-Davies et al. 58 |

Cu shows its inhibitory activity against growth of calcium phosphate crystals but not on oxalate. |

| Iron (Fe) | –Fe is considered to be an inhibitor of oxalate stones. However, more extensive research is needed to elucidate its role in lithogenesis. –Non-Ca stones have beens reported to have a lower content of Fe than Ca-containing stones. –The Fe3+ ions have the ability to establish stable chemical interactions with oxalate ions on the surface of calcium oxalate crystals. –An increased 24 h urinary Fe excretion was reported in calcium oxalate stone patients compared with healthy persons. |

Lieu et al.

59

Bazin and Pham 60 Joost and Tessadri 32 Levinson et al. 61 Durak et al. 62 Munoz and Valiente 63 Atakan and Akan 64 |

Fe is considered to be an inhibitor of oxalate stones. However, more extensive research is needed to elucidate ts role in lithogenesis. |

| Potassium (K) | –K is important for many functions in the human body and has a role in maintaining normal Ca balance in the body as K decreases urinary loss of Ca. It is reported that the lower the K intake below 74 mmol/day, higher the relative risk of stone formation. Such an effect can be ascribed to an increase in urinary Ca and a decrease in urinary citrate excretion induced by a low K intake. –A low–normal K intake and a higher NaCl intake were also observed in stone formers as compared to healthy people. –A significantly higher urine Na/K ratio was observed to increase the risk of stone formation. –Higher K intake was recommended in order to prevent kidney stone formation. Potassium, magnesium citrate reduces the risk of developing calcium oxalate stones. |

Curhan et al.

65

Lemann Jr et al. 66 Borsatti 67 Martini et al. 68 Cirillo et al. 69 Ettinger et al. 70 |

K together with Mg can help prevent calcium oxalate kidney stones. |

| Zinc (Zn) | –Zn is an essential trace element and its deficiency can enhance the expression of angiotensis II that constricts the blood vessels in kidneys and further aggravates the condition of individuals with obstructive kidney disease. –It has been described as an inhibitor of urinary stone formation but its exact role is divergent. –The higher content of Zn in weddellite stones than whewellite stones is reported, which may be linked to the fact that weddellite is formed during the first phase of the crystallization process and subsequently transforms to whewellite. –It was found in higher concentrations in Ca containing stones but also in organic urinary stones compared to other trace elements. –Its inhibitory effect was observed only on calcium phosphate stones but not on calcium oxalate growth. –Calcium phosphate stones were reported to have a higher Zn content than calciumoxalate stones. By contrast, brusite stones contain significantly less Zn than carbonate apatite stones. –Significantly higher amounts of Zn have also been observed in urinary excretion of stone patients. –Some authors detected no differences relating to Zn urinary excretion between healthy people and stone patients. –In some studies, serum Zn is lower in stone patients than in healthy controls. –Healthy controls were found to have significantly high urinary and serum Zn levels than stone patients. Study documented that mean Zn levels have an inhibitory effect on calcium oxalate stone formation. –Trace elements like Zn, Fe, and Mn appear to interfere with whewellite stone fragility. |

Yanagisawa et al.

71

Hofbauer et al. 50 Komleh et al. 72 Bazin and Pham 60 Joost and Tessadri 32 Hofbauer et al. 50 Levinson et al. 61 Atakan and Akan 64 Bazin and Pham 60 Joost and Tessadri 32 Meyer and Angino 42 Bazin and Pham 60 Trinchieri et al. 73 Komleh et al. 72 Rangnekar and Gaur 74 Ozgurtas et al. 75 François 76 Welshman and McGeown 77 Hofbauer et al. 50 Cohanim and Yendt 78 Pak and Cho 79 Atakan and Akan 80 (Turgut et al.; Höbarth et al.) 81 , 82 Khan 83 (Negri et al.; Słojewski et al.) 84 , 85 (Cao Pinna et al.; Aramendia et al.) 86 , 87 |

More extensive research is needed to determine the exact role of Zn in lithogenesis. |

| Cadmium (Cd) | –Cd is a widely disseminated metal that can be accumulated in living cells, thereby drastically interfering with their biological mechanisms. Increased concentrations of urinary beta-2 microglobulin can be an early indicator of renal dysfunction in persons chronically exposed to low but excessive levels of environmental Cd. The urinary beta-2 microglobulin test is an indirect method ofmeasuring Cd exposure. The longterm exposure of Cd leads to renal damage due to massive low weight tubular proteinuria. –A study of almost 2,700 renal cadaver samples showed that subjects who had died of renal disease had lower Cd concentrations. –Its inhibitory effect on calcium oxalate crystallization was also suggested. –Cd exposure has been found associated with a greater risk of kidney stone formation. –Recently, Swaddiwudhipong et al. (2011) found an increase in stone prevalence with increasing urinary Cd levels observed in both genders. A positive association was found between urinary Cd levels and stone prevalence. Finally, they documented that elevated calciuria induced by Cd might increase the risk of urinary stone formation in environmentally exposed population. –Some authors have also noted the increased prevalence of kidney stones in workers exposed to Cd which is possibly related to the increased urinary excretion of Ca or tubular damage. |

(Järup et al.; Iwata et al.)

88

,

89

Lyon et al. 90 Ferraro et al. 91 Swaddiwudhipong et al. 92 Järup et al. 93 |

The experimental findings clearly reveal that Cd plays an important role in kidney formation. |

| Boron (B) | –B is an ultra-trace element which is essential for healthy bone and joint function and effects on the balance and absorption of Ca, Mg and P. It is efficiently absorbed and excreted in the urine. Its deficiency seems to affect Ca and Mg metabolism, and affects the composition, structure and strength of bone. Due to its effects on Ca and Mg metabolism, B deficiency may also contribute to the formation of kidney stones. –Hunt et al. 94 reported low calcium oxalate urine excretion in postmenopausal women as a metabolic response to dietary B supplementation during low Mg intake. It is well reported that sodium borate is the most common form of supplement. B is increasingly used in Ca and bone replenishing nutritional formulas. It may be particularly useful in those whose Mg intake is low. This effect may be useful in the prevention of kidney stones. –Low concentration of B has been observed in patients with cystine stones. |

Nielsen

95

Hunt 94 Słojewski 15 |

More extensive research is needed to elucidate its role in lithogenesis. |

| Selenium (Se) | –Se is an essential trace element in humans and its deficiency has been found to induce renal calcification. Experimental and clinical studies have shown that Se has an inhibitory effect on urolithiasis. –Supplementation of Se and vitamin E prevents hyperoxaluria in experimental urolithic rats by decreasing the level of lipid peroxidation and the activities of oxalate synthesizing enzymes such as xanthine oxidase. –The oxalate and Ca concentration can also be reduced and the process of crystallization can be inhibited by Se which acts as nephroprotective antioxidant. –Recently, Sakly et al. 96 documented that Se is one of the stone formation inhibitors which could adhere to the crystal surface and would inhibit the induction of new crystals, growth and aggregation. |

Rayman

97

Fujieda et al. 98 (Selvam et al.; Lee et al.) 99 , 100 Lahme and Bruse 101 Rasool et al. 102 Sakly et al. 96 Zambonino et al. 103 Varshney et al. 104 |

The experimental findings indicate that Se act as an inhibitor to the stone formation. |

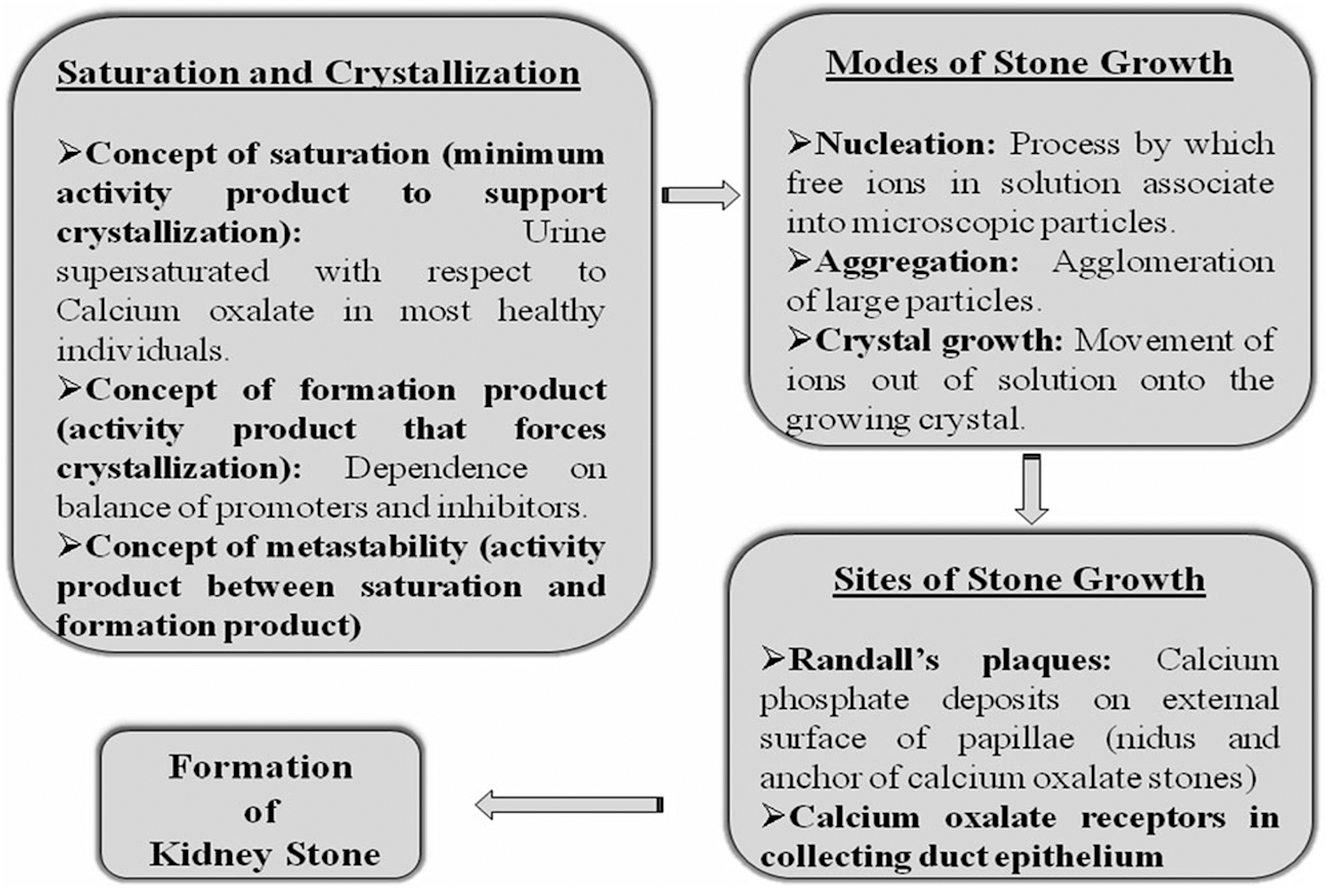

5 The physical and chemical process involved in the formation of kidney stones

Urinary supersaturation and crystallization are the primary drivers behind the precipitation of crystals within the kidneys and are predominantly attributed to inherited or acquired conditions that affect renal function. Furthermore, urinary supersaturation and crystallization are influenced by factors such as urine pH and the specific concentrations of various substances, including calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, uric acid, urates, struvite, amino acids (such as cysteine), purines (like 2,8-dihydroxyadenine and xanthine), and certain medications (such as atazanavir, sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin, and ceftriaxone). 107 Additionally, the formation and growth of crystals are regulated by a multitude of modulating molecules, including receptors, promoters, and inhibitors (Figure 1). 108

The series of physiochemical processes and mechanisms involved in the formation of kidney stones.

6 Discussion

Major and trace elements are inherent components of the human body, crucial for maintaining health when consumed through food, beverages, or inhalation. Numerous trace elements play vital roles in specific metabolic functions, being stored temporarily before being eliminated via the kidneys. 109 This may lead to the inadvertent inclusion of trace elements into urinary stones, potentially influencing crystal formation or altering the properties of such stones. The objective of this review is to evaluate the significance of major and trace elements in the development of kidney stones. 109 The initial investigation into trace elements in urinary stones dates back to 1963 with the work of Nagy et al., who identified a significant number of trace elements in stone samples (Ag, Al, Ba, Bi, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb, Si, Sr, and Zn). 110 Subsequently, the first examination of how trace elements influence the crystallization process of calcium oxalate was conducted by Sutor 111 and Eusebio and Elliot. 112 Their findings indicated that certain trace elements, including Co, Ni, Pb, tin (Sn), V, and Zn, could inhibit the crystallization of calcium oxalate. 112 The inaugural investigation into the impact of trace elements on the crystallization of calcium oxalate was conducted by Sutor 111 and (Eusebio and Elliot). 112 Their findings indicated that trace elements, notably Co, Ni, Pb, tin (Sn), V, and Zn, could impede the crystallization process of calcium oxalate. Additionally, 32 identified significantly elevated levels of Fe, Sb, Sr, and Zn in calcium oxalate stones, Fe, As, and Zn in phosphate stones, and Sb and As in uric acid stones. 32 This phenomenon may be attributed to the influence of heterogenic isomorphism, wherein foreign elements are incorporated into the crystal lattice of a salt. Bazin et al. 113 demonstrated a higher concentration of Zn and Sr in phosphate stones compared to calcium oxalate stones, with a lower proportion of these elements found in the latter Bazin et al. 113 Słojewski et al. 85 discovered a positive association between Zn and Sr concentrations in calcium phosphate stones, although no such correlation was observed in calcium oxalate stones. 85 In a study by; Durak et al. 41 the distribution of five metals – Fe, Cu, Cd, Zn, and Mg – in stones and hair was examined. 114 Significant variances were observed in the levels of these elements between the stones, the hair of patients, and that of control subjects. Early investigations by Bird and Thomas 53 and a more recent study by Atakan et al. 115 indicated that reduced urinary Zn levels in individuals prone to kidney stone formation suggest a potential inhibitory effect on stone development. 115 Turgut et al. 81 reported that decreased concentrations of Zn, Mn, and Mg in calcium oxalate monohydrate stones may render them resistant to extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. 106 Similar findings regarding Cu, Fe, Mg, and Zn were reported by Küpeli et al. 116 Scott et al. 117 observed elevated levels of Mg and K in phosphate stones, with comparatively lower levels of Na in calcium oxalate stones. 118 Analyses conducted on the core and shell of urinary stones have indicated elevated levels of Zn in the core of mixed calcium oxalate/apatite stones compared to pure calcium oxalate or struvite stones. 109 , 119 These findings suggest that Zn, along with other trace elements like Cu and Sr, may contribute to the formation of the stone nucleus. Additionally, some heavy metals such as Pb, Cd, Ni, and Al have been found in higher concentrations in the stone nuclei than in the crust, indicating their potential involvement in initiating stone crystallization. 120 These metals may act as nuclei or nidus for stone formation or could be contaminants. Trace elements like Zn, Cu, Fe, Ni, and Sr form insoluble salts with oxalate and phosphate ions, although no pure urinary stones solely consisting of these compounds have been identified yet. 109 However, zinc phosphate has been detected in the layers of struvite stones. Some trace elements are also present in small amounts in uric acid stones. Comparatively higher concentrations of Zn and other trace elements like Sr have been observed in calcium phosphate stones than in calcium oxalate stones. In a recent study by; 121 a comprehensive analysis of kidney stone samples using ICP spectrometry revealed varying concentrations of elements such as Ca, Mg, K, Zn, Fe, Cu, Mn, Pb, and Cr. The majority of urinary stones exhibited high levels of K, Cu, and Mg and low levels of Fe. Calcium oxalate and phosphate stones showed significant amounts of these elements, while uric acid and cystine stones displayed higher Zn content. 121 Calcium phosphate stones contained more trace elements than calcium oxalate stones, with weddellite stones containing higher trace element levels than whewellite stones. Techniques for kidney stone analysis, which involves several techniques including SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy), FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy), XRD (X-ray Diffraction), LIBS (Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy), ICP (Inductively Coupled Plasma), EDAX (Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis), and XAS (X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy).

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): SEM provides high-resolution images of the stone surface. It allows researchers to visualize the crystal morphology, surface features, and any organic or inorganic inclusions.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): FTIR identifies the chemical bonds present in the stone. By analyzing the infrared absorption spectrum, researchers can determine the types of molecules (such as oxalate, phosphate, or uric acid) within the stone.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): XRD is used to identify the crystalline phases present in the stone. It helps determine whether the stone is composed of calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, uric acid, or other compounds.

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS): LIBS analyzes the elemental composition of the stone. By focusing a laser on the stone surface, researchers can detect and quantify elements like calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus.

Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP): ICP is another elemental analysis technique. It measures trace elements (such as zinc, copper, and iron) in the stone. These elements play a role in stone formation and growth see (Figure 2).

Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis (EDAX): EDAX provides information about the elemental composition of the stone. It detects X-rays emitted when the stone is bombarded with electrons.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): XAS investigates the local atomic environment around specific elements within the stone. It helps determine oxidation states and coordination geometries.

Illustrates the flowchart for kidney stone analysis, which involves several techniques including SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy), FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy), XRD (X-ray Diffraction), LIBS (Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy), ICP (Inductively Coupled Plasma), EDAX (Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis), and XAS (X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy).

7 Conclusions

Trace elements become integrated into kidney stones depending on the stone type and their presence in urine, potentially influencing the properties of the stones. Significant variations in certain trace elements observed in the blood, urine, and serum of both stone patients and healthy individuals indicate their involvement in nephrolithiasis. Correlations between elements within each stone group and between calcium and other trace elements suggest their relevance in the processes underlying stone formation and growth. Further in vitro and in vivo investigations are necessary to fully elucidate the precise role of elements in kidney stone formation and growth. The review of literature underscores the multicomponent nature of kidney stones, including various crystalline components. Therefore, the choice of analytical technique for stone analysis should be capable of resolving all stone components. Published studies advocate for the use of FT-IR, Raman, or XRD as preferred analytical methods. Additionally, separate analysis of different stone regions at both elemental and molecular levels is essential for understanding stone pathogenesis. LIBS emerges as a suitable method for determining the elemental composition of each stone portion under investigation due to its point detection capability. LIBS enables rapid and simultaneous multi-elemental analysis of stone, urine, blood, and serum samples, providing qualitative information on the spatial distribution of elements within the kidney stone. Another advantage of LIBS is its non-destructive nature, allowing samples to be used for other molecular analyses using complementary methods such as IR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and XRD.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Adeola, F. O. Global Impact of Chemicals and Toxic Substances on Human Health and the Environment. Handbook Glob. Health 2020, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05325-3_96-1.Search in Google Scholar

2. Luyckx, V. A.; Al-Aly, Z.; Bello, A. K.; Bellorin-Font, E.; Carlini, R. G.; Fabian, J.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iyengar, A.; Sekkarie, M.; Van Biesen, W.; Ulasi, I.; Yeates, K.; Stanifer, J. Sustainable Development Goals Relevant to Kidney Health: An Update on Progress. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 15–32; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-00363-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Scales JR, C. D.; Smith, A. C.; Hanley, J. M.; Saigal, C. S.; Project, U. D. I. A. Prevalence of Kidney Stones in the United States. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 160–165; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Sivaguru, M.; Saw, J. J.; Wilson, E. M.; Lieske, J. C.; Krambeck, A. E.; Williams, J. C.; Romero, M. F.; Fouke, K. W.; Curtis, M. W.; Kear-Scott, J. L.; Chia, N.; Fouke, B. W. Human Kidney Stones: A Natural Record of Universal Biomineralization. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 404–432; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-021-00469-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Khan, S. R.; Pearle, M. S.; Robertson, W. G.; Gambaro, G.; Canales, B. K.; Doizi, S.; Traxer, O.; Tiselius, H.-G. Kidney Stones. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 1–23; https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Lu, T. J. Quantification of Ureteral Pain Sensation Induced by Kidney Stone. J. Appl. Mech. 2023, 90, 081003; https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4062222.Search in Google Scholar

7. Mannstadt, M.; Bilezikian, J. P.; Thakker, R. V.; Hannan, F. M.; Clarke, B. L.; Rejnmark, L.; Mitchell, D. M.; Vokes, T. J.; Winer, K. K.; Shoback, D. M. Hypoparathyroidism. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 1–21; https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.55.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Wesson, J. A.; Ward, M. D. Pathological Biomineralization of Kidney Stones. Elements 2007, 3, 415–421; https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.3.6.415.Search in Google Scholar

9. Keshavarzi, B.; Yavarashayeri, N.; Irani, D.; Moore, F.; Zarasvandi, A.; Salari, M. Trace Elements in Urinary Stones: A Preliminary Investigation in Fars Province, Iran. Environ. Geochem. Health 2015, 37, 377–389; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-014-9654-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Singh, V. K.; Rai, P. K. Kidney Stone Analysis Techniques and the Role of Major and Trace Elements on Their Pathogenesis: A Review. Biophysical reviews 2014, 6, 291–310; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-014-0144-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Oner, M.; Koutsoukos, P. G.; Robertson, W. Kidney Stone Formation—Thermodynamic, Kinetic, and Clinical Aspects. In Water-Formed Deposits; Elsevier, 2022.10.1016/B978-0-12-822896-8.00035-2Search in Google Scholar

12. Tian, Y.; Han, G.; Qu, R.; Xiao, C. Major and Trace Elements in Human Kidney Stones: A Preliminary Investigation in Beijing, China. Minerals 2022, 12, 512; https://doi.org/10.3390/min12050512.Search in Google Scholar

13. Khaleghi, F.; Rasekhi, R.; Mosaferi, M. Mineralogy and Elemental Composition of Urinary Stones: A Preliminary Study in Northwest of Iran. Period. Mineral. 2021, 90, 105–119.Search in Google Scholar

14. Bazin, D.; Portehault, D.; Tielens, F.; Livage, J.; Bonhomme, C.; Bonhomme, L.; Haymann, J.-P.; Abou-Hassan, A.; Laffite, G.; Frochot, V.; Letavernier, E.; Daudon, M. Urolithiasis: What Can We Learn from a Nature Which Dysfunctions? Compt. Rendus Chem. 2016, 19, 1558–1564; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2016.01.019.Search in Google Scholar

15. Słojewski, M. Major and Trace Elements in Lithogenesis. Cent. European. J. Urol. 2011, 64, 58; https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2011.02.art1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Cloutier, J.; Villa, L.; Traxer, O.; Daudon, M. Kidney Stone Analysis: “Give Me Your Stone, I Will Tell You Who You Are!”. World J. Urol. 2015, 33, 157–169; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-014-1444-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Huel, G.; Frery, N.; Takser, L.; Jouan, M.; Hellier, G.; Sahuquillo, J.; Giordanella, J. Evolution of Blood Lead Levels in Urban French Population (1979–1995). Revue D’epidemiologie et de Sante Publique 2002, 50, 287–295.Search in Google Scholar

18. Van Westing, A. C.; Küpers, L.; Geleijnse, J. Diet and Kidney Function: A Literature Review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2020, 22, 1–9; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-020-1020-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Venkatakrishna, S. S. B.; Onyango, L. C.; Serai, S. D.; Viteri, B. Kidney Anatomy and Physiology. Advanced Clinical MRI of the Kidney: Methods and Protocols; Springer, 2023.10.1007/978-3-031-40169-5_1Search in Google Scholar

20. Mcgregor, T.; Jones, S. Fluid and Electrolyte Problems in Renal Dysfunction. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 22, 406–409; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2021.05.008.Search in Google Scholar

21. Clayton-Smith, M.; Sharma, M.-P. Renal Physiology: Acid–Base Balance. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 22, 415–421; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2021.05.011.Search in Google Scholar

22. Almeida, L. F.; Tofteng, S. S.; Madsen, K.; Jensen, B. L. Role of the Renin–Angiotensin System in Kidney Development and Programming of Adult Blood Pressure. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 641–656; https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20190765.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Gupta, P.; Gupta, P. Target Organ Toxicity. In Problem Solving Questions in Toxicology: A Study Guide for the Board and other Examinations, 2020; pp 83–117.10.1007/978-3-030-50409-0_7Search in Google Scholar

24. Kolupayev, S.; Lesovoy, V.; Bereznyak, E.; Andonieva, N.; Shchukin, D. Structure Types of Kidney Stones and Their Susceptibility to Shock Wave Fragmentation. Acta Inf. Med. 2021, 29, 26; https://doi.org/10.5455/aim.2021.29.26-31.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Wood, B. G.; Urban, M. W. Detecting Kidney Stones Using Twinkling Artifacts: Survey of Kidney Stones with Varying Composition and Size. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 156–166; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.09.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Bihl, G.; Meyers, A. Recurrent Renal Stone Disease—Advances in Pathogenesis and Clinical Management. Lancet 2001, 358, 651–656; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05782-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Stoller, M. L.; Meng, M. V. Urinary Stone Disease: The Practical Guide to Medical and Surgical Management; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.10.1007/978-1-59259-972-1Search in Google Scholar

28. Haghighatdoost, F.; Gholami, A.; Hariri, M. Effect of Resistant Starch Type 2 on Inflammatory Mediators: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Compl. Ther. Med. 2021, 56, 102597; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102597.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Basavaraj, M.; Gupta, G.; Naveen, K.; Rudolph, V.; Bali, R. Local Liquid Holdups and Hysteresis in a 2‐D Packed Bed Using X-ray Radiography. AIChE J. 2005, 51, 2178–2189; https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.10481.Search in Google Scholar

30. Dornbier, R. A.; Bajic, P.; Van Kuiken, M.; Jardaneh, A.; Lin, H.; Gao, X.; Knudsen, B.; Dong, Q.; Wolfe, A. J.; Schwaderer, A. L. The Microbiome of Calcium-Based Urinary Stones. Urolithiasis 2020, 48, 191–199; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-019-01146-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, T.; Xia, J.; Wei, Y.; Wu, W.; Xie, X.; Yin, W.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, H.; Guo, L.; Xie, J.; Jiang, R.; Gao, Z.; Jin, Q.; Wang, J.; Cao, B. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Joost, J.; Tessadri, R. Trace Element Investigations in Kidney Stone Patients. Eur. Urol. 1987, 13, 264–270; https://doi.org/10.1159/000472792.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Ghashghaei, H. T.; Barbas, H. Pathways for Emotion: Interactions of Prefrontal and Anterior Temporal Pathways in the Amygdala of the Rhesus Monkey. Neuroscience 2002, 115, 1261–1279; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00446-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Schubert, R. Analyzing and Managing Risks–On the Importance of Gender Differences in Risk Attitudes. Manag. Finance 2006, 32, 706–715; https://doi.org/10.1108/03074350610681925.Search in Google Scholar

35. Chaudhri, N.; Caggiula, A. R.; Donny, E. C.; Booth, S.; Gharib, M.; Craven, L.; Palmatier, M. I.; Liu, X.; Sved, A. F. Self-Administered and Noncontingent Nicotine Enhance Reinforced Operant Responding in Rats: Impact of Nicotine Dose and Reinforcement Schedule. Psychopharmacology 2007, 190, 353–362; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0454-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Escott-Stump, S. Nutritional Review. Nutrition and Diagnosis-Related Care; Wolters Kluwer, Lippincot Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2007; pp 842–862.Search in Google Scholar

37. Ali, A. A. H. Overview of the Vital Roles of Macro Minerals in the Human Body. J. Trace. Elem. Min. 2023, 4, 100076; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemin.2023.100076.Search in Google Scholar

38. Domínguez, R.; Zhang, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P. E.; Lorenzo, J. M. Elderberry (Sambucus Nigra L.) as Potential Source of Antioxidants. Characterization, Optimization of Extraction Parameters and Bioactive Properties. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127266; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127266.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Kohri, K.; Garside, J.; Blacklock, N. The Role of Magnesium in Cacium Oxalate Urolithiasis. Br. J. Urol. 1988, 61, 107–115; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb05057.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Johansson, O.; Wedborg, M. The Ammonia-Ammonium Equilibrium in Seawater at Temperatures between 5 and 25 C. J. Solut. Chem. 1980, 9, 37–44; https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00650135.Search in Google Scholar

41. Durak, E. P.; Jovanovic-Peterson, L.; Peterson, C. M. Comparative Evaluation of Uterine Response to Exercise on Five Aerobic Machines. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 162, 754–756; https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(90)91001-s.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Meyer, J.; Angino, E. The Role of Trace Metals in Calcium Urolithiasis. Invest. Urol. 1977, 14, 347–350.Search in Google Scholar

43. Scott, D. B.; Medioli, F. S. Living vs. Total Foraminiferal Populations: Their Relative Usefulness in Paleoecology. J. Paleontol. 1980, 814–831.Search in Google Scholar

44. Anderson, B. For Space (2005): Doreen Massey. Key Texts in Human Geography 2008, 8, 227–235.10.4135/9781446213742.n26Search in Google Scholar

45. Cupisti, S.; Kajaia, N.; Dittrich, R.; Duezenli, H.; W Beckmann, M.; Mueller, A. Body Mass Index and Ovarian Function are Associated with Endocrine and Metabolic Abnormalities in Women with Hyperandrogenic Syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 158, 711–719; https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-07-0515.Search in Google Scholar

46. Ormanji, M. S.; Rodrigues, F. G.; Heilberg, I. P. Dietary Recommendations for Bariatric Patients to Prevent Kidney Stone Formation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1442; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051442.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Fraga, M. F.; Ballestar, E.; Paz, M. F.; Ropero, S.; Setien, F.; Ballestar, M. L.; Heine-Suñer, D.; Cigudosa, J. C.; Urioste, M.; Benitez, J.; Boix-Chornet, M.; Sanchez-Aguilera, A.; Ling, C.; Carlsson, E.; Poulsen, P.; Vaag, A.; Stephan, Z.; Spector, T. D.; Wu, Y. Z.; Plass, C.; Esteller, M. Epigenetic Differences Arise during the Lifetime of Monozygotic Twins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005,;102, 10604–10609; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0500398102.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Lall, S. P.; Kaushik, S. J. Nutrition and Metabolism of Minerals in Fish. Animals 2021, 11, 2711; https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092711.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Turgut, A.; Turgut, T. A Population-Based Study on Deaths by Drowning Incidents in Turkey. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2014, 21, 61–67; https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2012.759238.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Hofbauer, J.; Steffan, I.; Höbarth, K.; Vujicic, G.; Schwetz, H.; Reich, G.; Zechner, O. Trace Elements and Urinary Stone Formation: New Aspects of the Pathological Mechanism of Urinary Stone Formation. J. Urol. 1991, 145, 93–96; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38256-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Elbaset, M. A.; Salem, R. S.; Ayman, F.; Ayman, N.; Shaban, N.; Afifi, S. M.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Abdelaziz, M.; Elalfy, Z. S. Effect of Empagliflozin on Thioacetamide-Induced Liver Injury in Rats: Role of AMPK/SIRT-1/HIF-1α Pathway in Halting Liver Fibrosis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2152; https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11112152.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Task, N. H. C. C. P. The New Hampshire Climate Action Plan: A Plan for New Hampshire’s Energy, Environmental and Economic Development Future, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

53. Bird, E. D.; Thomas Jr, W. C. Effect of Various Metals on Mineralization In Vitro. PSEBM (Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med.) 1963, 112, 640–643; https://doi.org/10.3181/00379727-112-28126.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Wrissenberg, M. Calcinogenic Glycosides. In Toxicants of Plant Origin; CRC Press, 2023.10.1201/9781003418276-7Search in Google Scholar

55. Abdel-Gawad, M.; Zaghloul, M. S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Hashem, M.; Lashen, S. A.; Mahros, A. M.; Mohammed, A. Q.; Hassan, A. M.; Bekhit, A. N.; Mohammed, W.; Alboraie, M. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome Clinical Manifestations: A Systematic Review. Anti-Inflammatory Anti-Allergy Agents Med. Chem. 2022, 21, 115–120; https://doi.org/10.2174/1871523021666220328115818.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Shen, X.; Tang, H.; Mcdanal, C.; Wagh, K.; Fischer, W.; Theiler, J.; Yoon, H.; Li, D.; Haynes, B. F.; Sanders, K. O.; Gnanakaran, S.; Hengartner, N.; Pajon, R.; Smith, G.; Glenn, G. M.; Korber, B.; Montefiori, D. C. SARS-CoV-2 Variant B. 1.1. 7 Is Susceptible to Neutralizing Antibodies Elicited by Ancestral Spike Vaccines. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 529–539.e3; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2021.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Shaltout, A. A.; Harfouche, M.; Hassan, F. A.; Eichert, D. Synchrotron X-Ray Fluorescence and X-Ray Absorption Near Edge Structure of Low Concentration Arsenic in Ambient Air Particulates. J. Anal. Atomic Spectrom. 2021, 36, 981–992; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ja00504e.Search in Google Scholar

58. Barker-Davies, R. M.; O’Sullivan, O.; Senaratne, K. P. P.; Baker, P.; Cranley, M.; Dharm-Datta, S.; Ellis, H.; Goodall, D.; Gough, M.; Lewis, S.; Norman, J.; Papadopoulou, T.; Roscoe, D.; Sherwood, D.; Turner, P.; Walker, T.; Mistlin, A.; Phillip, R.; Nicol, A. M.; Bennett, A. N.; Bahadur, S. The Stanford Hall Consensus Statement for Post-COVID-19 Rehabilitation. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 949–959; https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Lieu, P. T.; Heiskala, M.; Peterson, P. A.; Yang, Y. The Roles of Iron in Health and Disease. Mol. Aspect. Med. 2001, 22, 1–87; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0098-2997(00)00006-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Bazin, P.-L.; Pham, D. L. Topology-preserving Tissue Classification of Magnetic Resonance Brain Images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2007, 26, 487–496; https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2007.893283.Search in Google Scholar

61. Levinson, A. D.; Oppermann, H.; Levintow, L.; Varmus, H. E.; Bishop, J. M. Evidence that the Transforming Gene of Avian Sarcoma Virus Encodes a Protein Kinase Associated with a Phosphoprotein. Cell 1978, 15, 561–572; https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(78)90024-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Durak, İ.; Karabacak, H. İ.; Büyükkoçak, S.; Cimen, M.; Kaçmaz, M.; Omeroglu, E.; Öztürk, H. S. Impaired Antioxidant Defense System in the Kidney Tissues from Rabbits Treated with CyclosporineProtective Effects of Vitamins E and C. Nephron 1998, 78, 207–211; https://doi.org/10.1159/000044912.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Munoz, J.; Valiente, M. Effects of Trace Metals on the Inhibition of Calcium Oxalate Crystallization. Urol. Res. 2005, 33, 267–272; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-005-0468-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Atakan, B.; Akan, O. B. On Channel Capacity and Error Compensation in Molecular Communication. Trans. Comput. Syst. Biol. 2008, X, 59–80; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92273-5_4.Search in Google Scholar

65. Curhan, G. C.; Willett, W. C.; Rimm, E. B.; Stampfer, M. J. A Prospective Study of Dietary Calcium and Other Nutrients and the Risk of Symptomatic Kidney Stones. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 833–838; https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199303253281203.Search in Google Scholar

66. Lemann, J. R. J.; Pleuss, J. A.; Gray, R. W.; Hoffmann, R. G. Potassium Administration Increases and Potassium Deprivation Reduces Urinary Calcium Excretion in Healthy Adults. Kidney Int. 1991, 39, 973–983; https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1991.123.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Borsatti, A. Calcium Oxalate Nephrolithiasis: Defective Oxalate Transport. Kidney Int. 1991, 39, 1283–1298; https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1991.162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Martini, A.; Walter, L.; Budai, J.; Ku, T. C.; Kaiser, C.; Schoell, M. Genetic and Temporal Relations between Formation Waters and Biogenic Methane: Upper Devonian Antrim Shale, Michigan Basin, USA. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 1998, 62, 1699–1720; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7037(98)00090-8.Search in Google Scholar

69. Cirillo, J. D.; Falkow, S.; Tompkins, L. S. Growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba Castellanii Enhances Invasion. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 3254–3261; https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.62.8.3254-3261.1994.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70. Ettinger, W. H.; Burns, R.; Messier, S. P.; Applegate, W.; Rejeski, W. J.; Morgan, T.; Shumaker, S.; Berry, M. J.; O’Toole, M.; Monu, J. A Randomized Trial Comparing Aerobic Exercise and Resistance Exercise with a Health Education Program in Older Adults with Knee Osteoarthritis: the Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST). JAMA 1997, 277, 25–31; https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540250033028.Search in Google Scholar

71. Yanagisawa, H.; Hammer, R. E.; Richardson, J. A.; Emoto, N.; Williams, S. C.; Takeda, S.-I.; Clouthier, D. E.; Yanagisawa, M. Disruption of ECE-1 and ECE-2 Reveals a Role for Endothelin-Converting Enzyme-2 in Murine Cardiac Development. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 105, 1373–1382; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci7447.Search in Google Scholar

72. Komleh, K.; Hada, P.; Pendse, A.; Singh, P. Zine, Copper and Manganese in Serum, Urine and Stones. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 1990, 22, 113–118; https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02549826.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Trinchieri, A.; Mandressi, A.; Luongo, P.; Longo, G.; Pisani, E. The Influence of Diet on Urinary Risk Factors for Stones in Healthy Subjects and Idiopathic Renal Calcium Stone Formers. Br. J. Urol. 1991, 67, 230–236; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410x.1991.tb15124.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Rangnekar, G.; Gaur, M. Serum and Urinary Zinc Levels in Urolithiasis. Br. J. Urol. 1993, 71, 527–529; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16019.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

75. Ozgurtas, T.; Yakut, G.; Gulec, M.; Serdar, M.; Kutluay, T. Role of Urinary Zinc and Copper on Calcium Oxalate Stone Formation. Urol. Int. 2004, 72, 233–236; https://doi.org/10.1159/000077122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

76. François, P. Chemical Evolution of the Galaxy-A Comparison of the Abundances of Light Metals in Disk and Halo Dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 1986, 160, 264–276.Search in Google Scholar

77. Welshman, S.; Mcgeown, M. A Quantitative Investigation of the Effects on the Growth of Calcium Oxalate Crystals on Potential Inhibitors. Br. J. Urol. 1972, 44, 677–680; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410x.1972.tb10141.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Cohanim, M.; Yendt, E. The Effects of Thiazides on Serum and Urinary Zinc in Patients with Renal Calculi. Johns Hopkins Med. J. 1975, 136, 137–141.Search in Google Scholar

79. Pak, B. C.; Cho, Y. I. Hydrodynamic and Heat Transfer Study of Dispersed Fluids with Submicron Metallic Oxide Particles. Exp. Heat Transf. Int. J. 1998, 11, 151–170; https://doi.org/10.1080/08916159808946559.Search in Google Scholar

80. Atakan, B.; Akan, O. B. Carbon Nanotube-Based Nanoscale Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 129–135; https://doi.org/10.1109/mcom.2010.5473874.Search in Google Scholar

81. Turgut, A. T.; Karakaş, H. M.; Özsunar, Y.; AltıN, L.; Çeken, K.; AlıCıOĞLU, B.; Sönmez, İ.; Alparslan, A.; Yürümez, B.; Çelik, T.; Kazak, E.; Geyik, P. Ö.; Koşar, U. Age-related Changes in the Incidence of Pineal Gland Calcification in Turkey: A Prospective Multicenter CT Study. Pathophysiology 2008a, 15, 41–48; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathophys.2008.02.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Höbarth, K.; Koeberl, C.; Hofbauer, J. Rare-earch Elements in Urinary Calculi. Urol. Res. 1993, 21, 261–264; https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00307707.Search in Google Scholar

83. Khan, S. R. Is Oxidative Stress, a Link between Nephrolithiasis and Obesity, Hypertension, Diabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, Metabolic Syndrome? Urol. Res. 2012, 40, 95–112; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-011-0448-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Negri, M.; Cagno, E.; Colicchia, C.; Sarkis, J. Integrating Sustainability and Resilience in the Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 2858–2886; https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2776.Search in Google Scholar

85. Słojewski, M.; Czerny, B.; Safranow, K.; Jakubowska, K.; Olszewska, M.; Pawlik, A.; Gołąb, A.; Droździk, M.; Chlubek, D.; Sikorski, A. Microelements in Stones, Urine, and Hair of Stone Formers: A New Key to the Puzzle of Lithogenesis? Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010, 137, 301–316; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8584-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

86. Cao Pinna, L.; Axmanová, I.; Chytrý, M.; Malavasi, M.; Acosta, A. T.; Giulio, S.; Attorre, F.; Bergmeier, E.; Biurrun, I.; Campos, J. A.; Font, X.; Küzmič, F.; Landucci, F.; Marcenò, C.; Rodríguez‐Rojo, M. P.; Carboni, M. The Biogeography of Alien Plant Invasions in the Mediterranean Basin. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e12980; https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12980.Search in Google Scholar

87. Aramendia, E.; Heun, M. K.; Brockway, P. E.; Taylor, P. G. Developing a Multi-Regional Physical Supply Use Table Framework to Improve the Accuracy and Reliability of Energy Analysis. Appl. Energy 2022, 310, 118413; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118413.Search in Google Scholar

88. Järup, L.; Hellström, L.; Alfvén, T.; Carlsson, M. D.; Grubb, A.; Persson, B.; Pettersson, C.; Spång, G.; Schütz, A.; Elinder, C.-G. Low Level Exposure to Cadmium and Early Kidney Damage: The OSCAR Study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2000, 57, 668–672; https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.57.10.668.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

89. Iwata, H.; Tanabe, S.; Aramoto, M.; Sakai, N.; Tatsukawa, R. Persistent Organochlorine Residues in Sediments from the Chukchi Sea, Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1994, 28, 746–753; https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-326x(94)90334-4.Search in Google Scholar

90. Lyon, J. D.; Barber, B. M.; Tsai, C. L. Improved Methods for Tests of Long‐Run Abnormal Stock Returns. J. Finance 1999, 54, 165–201; https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00101.Search in Google Scholar

91. Ferraro, P. J.; Miranda, J. J.; Price, M. K. The Persistence of Treatment Effects with Norm-Based Policy Instruments: Evidence from a Randomized Environmental Policy Experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 318–322; https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.318.Search in Google Scholar

92. Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Limpatanachote, P.; Mahasakpan, P.; Krintratun, S.; Punta, B.; Funkhiew, T. Progress in Cadmium-Related Health Effects in Persons with High Environmental Exposure in Northwestern Thailand: A Five-Year Follow-Up. Environ. Res. 2012, 112, 194–198; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2011.10.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

93. Järup, L.; Berglund, M.; Elinder, C. G.; Nordberg, G.; Vanter, M. Health Effects of Cadmium Exposure–A Review of the Literature and a Risk Estimate. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1998, 1–51.Search in Google Scholar

94. Hunt, S. D. Competing through Relationships: Grounding Relationship Marketing in Resource‐Advantage Theory. J. Market. Manag. 1997, 13, 431–445; https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.1997.9964484.Search in Google Scholar

95. Nielsen, J. Usability Inspection Methods. In Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1994; pp 413–414.10.1145/259963.260531Search in Google Scholar

96. Sakly, A.; Gaspar, J. F.; Kerkeni, E.; Silva, S.; Teixeira, J. P.; Chaari, N.; Cheikh, H. B. Genotoxic Damage in Hospital Workers Exposed to Ionizing Radiation and Metabolic Gene Polymorphisms. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A 2012, 75, 934–946; https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2012.690710.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

97. Rayman, M. P. The Importance of Selenium to Human Health. Lancet 2000, 356, 233–241; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02490-9.Search in Google Scholar

98. Fujieda, S.; Fujita, A.; Fukamichi, K. Reduction of Hysteresis Loss in Itinerant-Electron Metamagnetic Transition by Partial Substitution of Pr for La in La (FexSi1– x) 13. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 310, e1004–e1005.10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.10.960Search in Google Scholar

99. Selvam, T. P.; Kumar, P. V.; Kumar, A. S. Synthesis and Anti-Oxidant Activity of Novel 6, 7, 8, 9 Tetra Hydro-5h-5-(2’-Hydroxy Phenyl)-2-(4’-Substituted Benzylidine)-3-(4-Nitrophenyl Amino) Thiazolo Quinazoline Derivatives. Res. Biotechnol. 2010, 1.Search in Google Scholar

100. Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barret, K. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I. In II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team; Lee, H.; Romero, J., Eds. IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

101. Lahme, E.; Bruse, M. Microclimatic Effects of a Small Urban Park in Densely Built-Up Areas: Measurements and Model Simulations. ICUC5, Lodz 2003, 5.Search in Google Scholar

102. Rasool, S. F.; Chin, T.; Wang, M.; Asghar, A.; Khan, A.; Zhou, L. Exploring the Role of Organizational Support, and Critical Success Factors on Renewable Energy Projects of Pakistan. Energy 2022, 243, 122765; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.122765.Search in Google Scholar

103. Zambonino, M. C.; Quizhpe, E. M.; Mouheb, L.; Rahman, A.; Agathos, S. N.; Dahoumane, S. A. Biogenic Selenium Nanoparticles in Biomedical Sciences: Properties, Current Trends, Novel Opportunities and Emerging Challenges in Theranostic Nanomedicine. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 424; https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13030424.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

104. Varshney, D.; Mishra, A. K.; Joshi, P. K.; Roy, D. Social Networks, Heterogeneity, and Adoption of Technologies: Evidence from India. Food Pol. 2022, 112, 102360; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102360.Search in Google Scholar

105. Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; Liang, H. Recent Advances on the Mechanisms of Kidney Stone Formation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 48, 1–10.10.3892/ijmm.2021.4982Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

106. Turgut, M.; Unal, I.; Berber, A.; Demir, T. A.; Mutlu, F.; Aydar, Y. The Concentration of Zn, Mg and Mn in Calcium Oxalate Monohydrate Stones Appears to Interfere with Their Fragility in ESWL Therapy. Urol. Res. 2008, 36, 31–38; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-007-0133-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

107. Daudon, M.; Frochot, V.; Bazin, D.; Jungers, P. Drug-induced Kidney Stones and Crystalline Nephropathy: Pathophysiology, Prevention and Treatment. Drugs 2018, 78, 163–201; https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0853-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

108. Rodgers, A. L. Physicochemical Mechanisms of Stone Formation. Urolithiasis 2017, 45, 27–32; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-016-0942-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

109. Hesse, A.; Siener, R. Trace Elements in Urolithiasis. In Urolithiasis: Basic Science and Clinical Practice, 2012; pp 227–230.10.1007/978-1-4471-4387-1_27Search in Google Scholar

110. Nagy, Z.; Szabó, E.; Kelenhegyi, M. Spektralanalytische untersuchung von nierensteien auf metallische spurenelemente. Z Urol 1963, 56, 185–190.Search in Google Scholar

111. Sutor, D. J. Growth Studies of Calcium Oxalate in the Presence of Various Ions and Compounds. Br. J. Urol. 1969, 41, 171–178.10.1111/j.1464-410X.1969.tb09919.xSearch in Google Scholar

112. Eusebio, E.; Elliot, J. Effect of Trace Metals on the Crystallization of Calcium Oxalate. Invest. Urol. 1967, 4, 431–435.Search in Google Scholar

113. Bazin, D.; Chevallier, P.; Matzen, G.; Jungers, P.; Daudon, M. Heavy Elements in Urinary Stones. Urol. Res. 2007, 35, 179–184; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-007-0099-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

114. Durak, I.; Kilic, Z.; Sahin, A.; Akpoyraz, M. Analysis of Calcium, Iron, Copper and Zinc Contents of Nucleus and Crust Parts of Urinary Calculi. Urol. Res. 1992, 20, 23–26; https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00294330.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

115. Atakan, I. H.; Kaplan, M.; Seren, G.; Aktoz, T.; Gül, H.; Inci, O. Serum, Urinary and Stone Zinc, Iron, Magnesium and Copper Levels in Idiopathic Calcium Oxalate Stone Patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2007, 39, 351–356; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-006-9050-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

116. Küpeli, T.; Altundaǧ, H.; Imamoǧlu, M. Assessment of Trace Element Levels in Muscle Tissues of Fish Species Collected from a River, Stream, Lake, and Sea in Sakarya, Turkey. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 17.10.1155/2014/496107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

117. Scott, K. M.; Ashley, P. M.; Lawie, D. C. The Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Maturity of Gossans Derived from Volcanogenic Zn–Pb–Cu Deposits of the Eastern Lachlan Fold Belt, NSW, Australia. J. Geochem. Explor. 2001, 72 (3), 169–191.10.1016/S0375-6742(01)00159-5Search in Google Scholar

118. Schneider, H.-J. Morphology of Urinary Tract Concretions. In Urolithiasis: Etiology·Diagnosis; Springer, 1985.10.1007/978-3-642-70579-3_1Search in Google Scholar

119. Singh, V. K.; Rai, A.; Rai, P.; Jindal, P. Cross-Sectional Study of Kidney Stones by Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Laser Med. Sci. 2009, 24, 749–759; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-008-0635-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

120. Perk, H.; Serel, T. A.; Koşar, A.; Deniz, N.; Sayin, A. Analysis of the Trace Element Contents of Inner Nucleus and Outer Crust Parts of Urinary Calculi. Urol. Int. 2002, 68, 286–290; https://doi.org/10.1159/000058452.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

121. Giannossi, M. L.; Summa, V.; Mongelli, G. Trace Element Investigations in Urinary Stones: A Preliminary Pilot Case in Basilicata (Southern Italy). J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2013, 27, 91–97; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.09.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Comprehensive reviews on the potential applications of inorganic metal sulfide nanostructures in biological, environmental, healthcare, and energy generation and storage

- Comparative analysis of dye degradation methods: unveiling the most effective and environmentally sustainable approaches, a critical review

- A review: evaluating methods for analyzing kidney stones and investigating the influence of major and trace elements on their formation

- Revolutionizing Metal-organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Wastewater Treatment Applications

- Advances in synthesis and anticancer applications of organo-tellurium compounds

- Effect of doping of metal salts on polymers and their applications in various fields

- Recent trends in medicinal applications of mercury based organometallic and coordination compounds

- A review of organometallic compounds as versatile sensors in environmental, medical, and industrial applications

- A comprehensive overview of fabrication of biogenic multifunctional metal/metal oxide nanoparticles and applications

- Semiconductor-attapulgite composites in environmental and energy applications: a review

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Comprehensive reviews on the potential applications of inorganic metal sulfide nanostructures in biological, environmental, healthcare, and energy generation and storage

- Comparative analysis of dye degradation methods: unveiling the most effective and environmentally sustainable approaches, a critical review

- A review: evaluating methods for analyzing kidney stones and investigating the influence of major and trace elements on their formation

- Revolutionizing Metal-organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Wastewater Treatment Applications

- Advances in synthesis and anticancer applications of organo-tellurium compounds

- Effect of doping of metal salts on polymers and their applications in various fields

- Recent trends in medicinal applications of mercury based organometallic and coordination compounds

- A review of organometallic compounds as versatile sensors in environmental, medical, and industrial applications

- A comprehensive overview of fabrication of biogenic multifunctional metal/metal oxide nanoparticles and applications

- Semiconductor-attapulgite composites in environmental and energy applications: a review