Abstract

The re-evaluation of animals, plants, and microorganisms for green synthesis has revolutionized the fabrication of metallic nanoparticles (MNPs). Green synthesis provides more biocompatibility compared to chemically synthesized MNPs, which make them ideal for diverse biological applications, especially in biomedicine. Various organisms have been extensively studied for green synthesis. Interestingly, angiosperms, algae, and animal-derived biomaterials like chitin and silk have shown a prominent role in synthesizing these nanoparticles. Moreover, bacteria, viruses, and fungi serve as sources of reducing agents, further expanding green synthesis possibilities. Despite progress, research on natural reducing agents remains relatively limited, with only a few exceptions such as tea and neem plants receiving attention. Green-synthesized nanoparticles have diverse applications in various fields. In biomedicine, they enable drug delivery, targeted therapies, and bio-imaging due to their enhanced biocompatibility. Some MNPs also exhibit potent antimicrobial properties, aiding in disease control and eco-friendly disinfection. Furthermore, green nanoparticles contribute to environmental remediation by purifying water and serve as sensitive biosensors for diagnostics and environmental monitoring. This review will provide the recent progress and advancements in the field of green synthesis (GS) of nanoparticles. It will also analyze the key characteristics and evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of GS compared to chemical synthesis.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, nanotechnology is the most promising and rapidly growing field of engineering and material science, which includes the relationship of chemistry, biology, material science and knowledge of other branches. In the beginning of nanotechnology (NT) and green chemistry (GC) have significant scientific events that influence the goal of research for environmental safety. Nanotechnology and green chemistry are genuinely regarding to appreciate and have made a significant contribution recently. 1 The twelve green chemistry principles in green nanotechnology strongly advise taking to green alternatives for Nano-product. However, this knowledge could run into many difficulties because not every formulation for nanotechnology may have a green choice. While pursuing the technical advantages of the nanoscale over bulk materials, one should be mindful of the drawbacks of nano-sized materials. 2

Green synthesis GS has emerged as a pivotal field in nanotechnology over the last few decades, offering a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional chemical and physical methods of nanoparticle synthesis. 3 GS uses natural reagents like plant extracts, microbial biomolecules, and animal-derived biomaterials to produce nanoparticles, thereby reducing the environmental effects and health risks associated with conventional synthesis methods (discuss in detailed later). 4 Among others in addition to the ethnobotanical and medicinal chemistry perspectives. The search for new substances that can make metallic ions valence-free and so allow for the bottom-up method of MNP synthesis has intensified. Actually, GS is thought to facilitate biomolecules’ binding to the surface of metallic nanoparticles during their production. This behavior is known as “capping” in the GS profession. 5 Plants have been the main target of GS and the success rate is also very high compared to animal and microbial-mediated GS. 6

Numerous studies have shown the possibility of GS and capping behavior in plants from various taxonomic groupings. 7 Animal-based biomolecules like chitosan, silk, and alginate have also demonstrated their potential for usage in GS, in addition to plant-based biomolecules. 8 , 9 Invertebrate species have recently been experimented to see if they may produce MNPs. 10 Bacteria, fungi and viruses in the microbial world have responded well to the MNPs synthesis through green synthesis. 11 Various studies have showcased the progress made in this particular field. 12 It is evident that GS has provided NT and GC with a fresh perspective on how to formulate novel ideas for use in applied nanotechnology. However, before GS can be greeted as an independent and well-recognized subject for adoption on a global basis further, study must be done. In this review, we will discuss the key findings on GS of various MNPs using plants-based, animal derived biomaterials, and microbial biomolecules, followed by detailed examination of GS’s benefits and drawbacks, as well as the future perspectives.

2 Biofabrication of metallic nanoparticles (MNPs)

Metallic Nanoparticles (MNPs) can be synthesized using various natural sources such as plants, microorganisms, animals, and viruses.

2.1 Plant-induced biofabrication of MNPs

Plants induced fabrication of metal and metal oxide NPs have taxonomically verified, due to the very large number of plants examined for GS, certain subsections do not cover all of them. But plants that have been researched for GS and may have some therapeutic uses have been given importance. The process of MNPs production by GS has been studied in order to understand the metallic ions reduction capability of plants and to support their capping nature. 13 A schematic representation of the synthesis of nanoparticles from plants is shown in Figure 1. Including angiosperms are well-suited for GS of MNPs, given their position at the top of the plant evolutionary tree. Global range, accessibility and socioeconomic culture have made this taxonomic group of plants more approachable to humans. Angiosperms have always been essential in the natural treatment of illnesses in humans and other animals.

This schematic diagram showcases a plant-based method for synthesis metal nanoparticles. Extracts from plant parts like leaves or roots contain specialized molecules that serve as electron donors, which enable the formation of MNPs from salts such as silver nitrate. The diagram illustrates the sequential stages of this process, from initial metal clustering to controlled nanoparticle growth, with specific plant materials aiding in nanoparticle stabilization. Adopted from Dikshit et al. 14 Copyright permission@ MDPI 2021.

Furthermore, the majority of angiosperm species are edible, which draws interest in researching their scientific significance. 15 Either poorly understood or unknown are the details of the first report on the application of angiosperms for green synthesis GS. The broad-based character of angiosperms has aided in executing nature’s decreasing capacity towards the quick expansion of this green field of study, as seen by the global development of GS research. Asian countries, which are incredibly rich in plant bio resources, have made a huge contribution to enhancing the GS library with fresh finds. 16 , 17 Plant species are not all of the randomly chosen but may be legitimately used in GS practices. This has been one of the main issues with the GS technique, and it may be recognized to the absence of real widely known types. 17 In light of this reality, recent times have seen an unanticipated acceleration in the search for new plant species. These initiatives have undoubtedly expanded the GS library and promoted this type of research’s advancement.

The main challenge is to highlight the GS mechanism that inspires each plant species employed and to support its selection over others. To find and improved all angiosperm plants investigated for GS. 18 The common angiosperm plant species studied for GS has been tried and included in many MNPs that use the GC method. This indicates that phytochemicals derived from plants have a considerable reduction potential. To produce MNPs, phytochemicals from plants neutralize uni- or multivalent metallic cations (Mn) into neutral atoms (Mo). With larger (e.g., Au3 e− Auo(s), Eo (V) = 1.52) and smaller standard reduction potentials (e.g., Mg2 2e− Mg(s), Eo (V) = −2.372), plant molecules with lower ionization potentials reduce metallic cations. The bulk of studies involving angiosperm species have focused on the GS of Au or Ag nanoparticles, and there are few reports on other MNPs. Plant taxonomic groupings employed in the green synthesis of various metallic nanoparticles, along with their current state of utilization as of reported by Das et al. 19 This might be due to plant molecules’ incapacity to reduce metal cations with lower reduction potentials. By identifying plant chemicals with greater electron-donating capabilities, it may be feasible to make green synthesis a widely used technique for producing MNPs.

It is evident that many angiosperm plant species are used in our edibles and medicinal products. Thus, while selecting plants have certain other important technical variables such edibility, socioeconomic relevance, ethnobotanical background and availability should be considered in addition to the reducing nature of the chosen plant species. 20 Many MNPs may be produced using a random selection technique; however, a biocompatibility concern might make this a non-progressive area of research. The most well-known examples of plant species with substantial medicinal potential studies that also have clinical significance include angiosperm species such as Centella asiatica, Azadirachta indica, Camellia sinensis, and Aloe vera. According to a cytotoxicity test conducted by Britto et al., 21 MNPs are biocompatible due to the phytochemical molecules capping behavior. However, the MNPs’ size and form are crucial in determining their overall biocompatibility. 22

Green synthesized MNPs should have a size range of less than 100 nm for their biological applications. As shown in Table 1, MNPs can have sizes ranging from 2 to 500 nm. Although this range is very changeable, currently the most challenging issue for GS researchers is regulating the size and shape of MNPs. Recent studies suggest that the morphology (shape and size) of the generated MNPs may be correlated with the factors (e.g., concentrations of plant extract, concentrations of metallic ions, reaction time, and temperature). 37 Although this assertion may be valid in certain cases, it may be that plant molecules were unable to decrease metal cations. Making GS a common mode of MNPs production may be possible by screening plant compounds with increased electron-donating capacities. 38

Some representative examples of angiospermic plant species used for green synthesis of different metallic nanoparticles.

| Plant name | Part used | Solvent used | Type of NPs | Reaction temperature | Size (nm) | Mechanism/causative agent | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelumbo nucifera L | Leaves | Water | Ag | Room temperature | 25–80 nm | Not mentioned | 23 |

| Jatropha curcas L | Latex | Water | Pb | Room temperature | 10–12.5 nm | Curcacycline A and curcacycline B | 24 |

| Lemongrass plant extract | Leaves | Water | Au | Room temperature | 200–500 nm | Sugar derivative molecules | 25 |

| Avena sativa | Stems | Water | Au | Room temperature | 5–85 nm | Not mentioned | 26 |

| Asparagus racemosus | Tuber cortex | Water | Pd | Room temperature | 1–6 nm | Bioactive compounds (not specified) | 27 |

| Camellia sinensis | Leaves | Water | Pt | Room temperature | 30–60 nm | Pure tea polyphenol | 28 |

| Cintella asiatica | Leaves | Ethanol (70 %) | Au | Room temperature | 9.3, 11.4 nm | Phenolic compound | 29 |

| Syzygium aromaticum | Flower, buds | Water | Cu | Room temperature | 5–40 nm | Eugenol (not specified) | 30 |

| Euphorbia esula L | Leaves | Water | Cu | Room temperature | 20–110 nm | Flavonoids and phenolic acids | 31 |

| Nephelium lappaceum L | Peels | Hydro-ethanol 80 °C | MgO | 100 nm | Not mentioned | 32 | |

| Aloe barbadensis miller | Leaves | Water | ZnO | 150 °C | 25–40 nm | Phenolic compounds, terpenoids or proteins | 33 |

| Nephelium lappaceum L | Peels | Hydro-ethanol | NiO | 80 °C | 50 nm | Nickel–ellagate complex formation | 34 |

| Ocimum tenuiflorum | Whole plant | Ethanol (70 %) | ZnO | Room temperature | 50–400 nm | Bioactive compounds (not specified) | 35 |

| Eucalyptus | Leaves | Water | Fe2O3 | Room temperature | 20–80 nm | Epicatechin and quercetin–glucuronide | 36 |

It is apparent that a large number of angiosperm plant species are employed in our meals or as medicines. Therefore, in choosing plants consideration should be given to a number of other important technical variables such as edibility, socioeconomic relevance, ethnobotanical background and availability in addition to the reducing nature of the chosen plant species. A random selection procedure might be used to manufacture metallic NPs; however, a biocompatibility issue might render this a non-progressive research area. The most well-known examples of plant species with substantial medicinal potential studies that also have clinical significance include angiosperm species, such as C. asiatica, A. indica, C. sinensis and Aloe Vera. The MNPs are biocompatible due to the phytochemical molecules’ capping behavior. However, the MNPs’ dimensions and shape are crucial in determining their general biocompatibility. 20

Green synthesized MNPs should have a size range of less than 100 nm for their biological applications. The size of MNPs can vary from 2 to 500 nm. 37 These days, managing the number and structure of MNPs can be considered the most challenging issue GS researchers are dealing with recent studies suggest that the morphology (form and size) of the generated MNPs may be correlated with the parameters (plant extract concentrations, metallic ion concentrations, reaction duration and temperature).

Though some people might find this assertion to be accurate Mechanism research or information on the causes of decrease and capping behavior in (GS) with angiosperm species has not been thoroughly investigated. Further various plants species included in Table 1 provide some crucial examples for both particular and general explanations of the mechanisms and causal agents. Tea-producing plant C. sinensis is one of the more studied plant species when it comes to GS mechanism research. Catechins, theaflavins, and thearubigins were isolated and purified from tea and experiments with these biomolecules using Au3? Cations demonstrated their participation in the (GS) of Au nanoparticles. 23 , 28

A. indica’s lowering and capping roles in the GS of Au and Ag nanoparticles have also been confirmed by the tetra-nortriterpenoid azadirachtin isolation and purification. 39 For the green production of Pt nanoparticles, pure tea polyphenol (from Sigma) is available commercially. These results may serve as an excellent foundation for planning large-scale GS investigations. Epicatechin and quercetin-glucuronide are two phenolic chemicals that are crucial to use in the green synthesis of MNPs (like Fe2O3) because they are also sold in pure form. 36 , 40 The plant species Jatropha curcas L.’s latex contains two cyclic peptide compounds called curcacycline (A) and curcacycline (B), which are believed to reduce metal cations. The functions of these peptide compounds have been better understood thanks to structural elucidation. 41 Reports on the in situ production of metal nanoparticles in live plants are scarce. One such instance is the in situ creation of Ag nanoparticles utilizing Alfa sprouts as a plant species. 42 , 43

In addition to these particular discoveries researchers appear to be leaning more towards a general mechanical explanation of the GS process for many angiosperm species. The pattern indicates that common phytochemical components have been implicated in the GS of many MNPs, including phenols, alkaloids, terpenoids and some pigments. 29 , 30 However, it is imperative to confirm each constituent’s capacity to reduce various metal anions. During GS of MNPs, instrumental examination such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) frequently results in the conclusion of the plant molecules’ capping nature. These analytical tools are either perfect or all-inclusive although the results of the FTIR and EDX tests may be significantly impacted by the green synthesized MNPs’ downstream processing.

Overall, this recently developed field of nano-green science has made amazing advances. But perhaps most significantly, because it is not limited to any one particular region of the globe, GS is now a more appealing option to traditional GS approaches due to its non-constrictive nature. The verification of certain rules for the process of choosing plants, the processing of MNPs both upstream and downstream, the assessment of MNPs’ biocompatibility and the qualities that are needed for biomedical applications are all absent at this point. Furthermore, creating protocols for large-scale GS production is another important area that has to be the future of concentration.

2.1.1 Gymnospermic plants-induced biofabrication of MNPs

Since gymnosperms were the first plants to produce seeds, their evolution was an important stage in the development of plant reproduction. Gymnosperms that still exist are found almost everywhere on the globe. Each plant family is distinctive due to the wide diversity of plants, which are well-organized and contain many valuable metabolites. 44 These biomolecules reduce metals to become MNPs. It was shown recently that eukaryotes might also reduce metal ions. For many years, researchers have employed prokaryotes to investigate the bio-sorption and bio-reduction of metal ions. The function that various reducing/stabilizing agents of cells play in the production and bioaccumulation of MNPs in plants has been extensively studied. Gaining further insight into the genetic encodeng of these agents and their functions, 45 which included reducing and stabilizing MNPs in plant cells helped to clarify how they functioned as a catalyst for the detoxification of contaminants. 46

Plants need copper (Cu) as a micronutrient and when Cu ions are reduced to neutral atoms and then to Cu nanoparticles, plants detoxify the increased to quantity. 47 There are few studies on the biosynthesis of MNPs with gymnosperms. 48 This might be as a result of the lesser worldwide awareness and accessibility of certain plant groups. More research on MNP biosynthesis using gymnosperms is necessary because, although they are vascular plants like angiosperms/gymnosperms ability to produce MNP is dependent on the phytochemical composition of their plant cells. 49 The process of creating NPs revealed that the primary factors influencing NP size, shape and number are the kind of plant and its constituents, the pH of synthesis and the bioavailability of metals. 50 Most of the research on the biosynthesis of metal-NPs (MNPs) was conducted in angiosperms and concentrated on using plant biomass, plant extract or real plants to produce silver (Ag) and gold (Au) NPs. 51 The process of metal reduction and stabilization by phytochemicals has also been explored by angiosperms. Gymnosperms and angiosperms share several phytochemical families, making it possible to extrapolate the mechanism of MNP production by comparing their structural characteristics. 52 Table 2 enumerates the common gymnospermic plants that were looked at for the synthesis of MNPs. The Cycas plant’s antoxidative system was activated by metallic stress (AgNO3), which led to the creation of AgO NPs. 55

Gymnospermic plants used for the synthesis of MNPs.

| Plant species | Plant material | Solvent | Type of MNPs | Reaction temperature | Size | Shape | Mechanism/causative agent | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo biloba | Leaves | Water | Ag, Au | 25–95 C | 15–50, 5–40 nm | Cubic and spherical | Proteins and metabolites | 53 |

| Cycas | Leaf | 50 % ethanol | Ag | Room temperature | 2–6 nm | Spherical | Ascorbic, amenti/hinoki | 54 , 55 |

| Pinus densiflora | Leaves | Water | Ag | 25–95 C | 15–500 nm | Cubic | Not mentioned | 56 |

| Pinus resinosa | Bark | Water | Pb | 80 C | 16–20 nm | Spherical | Fulvic acid | 57 |

| Pinus thunbergii | Pine cone | Water | Ag | Room temperature | 35 nm | Triangular and hexagonal | Hydroxyl and carbonyl groups | 58 |

The carbonyl (ascorbic acid) and thiol (metallothionein) groups required for this bioprocess are present in the leaves of the Cycas plant, along with phenolic compounds (amento-flavone and hinoki-flavone), which are special bi-flavones that are exclusive to gymnospermic plants. 59 , 60 The primary functional groups and the responsible phytochemical families are comparable when comparing the production method of Ag NPs with angiosperms. 61 The actual chemical compounds might be affecting the physicochemical properties of recently generated MNPs. The aqueous extract of cypress (Thuja orientalis) leaves has the potential to reduce in their green synthesis of Au NPs. 62 The response finished in 10 min at room temperature with a progress rate above 90 % percent. The synthesized Au NPs were mostly spherical in shape with an average particle size ranging from 5 to 94 nm, greatly depending on the pH and extract concentration. The crystalline structure and the binding of capping molecules to the particle surface were confirmed by their FTIR and X-ray investigations. 54 , 63

In a similar study, Cu NPs with a size range of 15–20 nm were made using Ginkgo biloba Linn leaf extract as a reducing and stabilizing agent at room temperature, because no hazardous compounds were used, this synthesis technique can be considered an environmentally friendly process. 64 Torreya nucifera leaves extract used to produce Ag NPs. They found that temperature and extract concentration had significant influence on NP size and shape, respectively. 65 , 66 The produced nanoparticles (NPs) varied in size from 10 to 125 nm and were mostly spherical found, while in different study that extracts from the leaves of Cycas circinalis may quickly decrease Ag ions, producing crystalline Ag NPs. In a manner similar to this the manufactured NPs had spherical forms with a 13–51 nm diameter. 67 High concentrations of phenolic chemicals have been found in the leaves and bark of gymnospermic plants in the pine family. 58 Pinus thunbergii formed MNPs mainly from the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of phenolic compounds.

The mechanism and molecules involved in the bioprocess have not been studied, especially in pine trees. The effect of temperature and pH on the size, shape and efficiency of NPs was assessed in these plants. Studies have demonstrated that NPs’ properties are favorably influenced by high temperature, pH and duration. 68 Studies show that because Au (1.83) NPs have a bigger reduction potential than Ag (0.79), they develop more quickly; hence, metallic characteristics also affect the process factors. The presence of proteins, surface coating molecules and metabolites with polyphenol functional groups for the stabilization of MNPs has been shown by FTIR investigations respectively. 50 These biological elements of the extract from gymnospermic plants create and stabilize MNPs, an environmentally benign and efficient substitute for traditional methods. 69

2.1.2 Pteridophytes and bryophytes-induced biofabrication of MNPs

Pteridophytes plant extracts have historically been utilized as antibacterial agents. This antimicrobial action could be the reason why Pteridophytes have survived evolutionary pressure for more than 350 million years. Three distinct Pteridophytes plants of the genus Pteris were utilized in studies to synthesize Ag NPs. 21 Plant Pteris biaurita Ag NPs exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity of the NPs that were produced. Different plant-derived NPs have varying antibacterial activities but the mechanisms behind these differences are still being investigated. The Pteridophytes plants employed in the biosynthetic process to produce MNPs are listed in Table 3. Nephrolepis exaltata fern-derived nanoparticles (NPs) have demonstrated antibacterial efficacy against many bacterial pathogens. 72 Phytochemicals including tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids and terpenoids are present in Adiantum philippense. L, a substance that mimics angiosperms and makes plant extracts highly oxidative, might be implicated in Produce nanoparticles of gold and silver. MNPs generated from Pteridophytes have been demonstrated to have improved antibacterial activity in investigations thus far; this may be because the plants themselves have differing inherent therapeutic properties (antioxidant and antibacterial). Comparing the mechanism and antibacterial activity of derived NPs to those of other plant-derived NPs is still essential, though. Kunjiappan et al. have demonstrated that the flavonoids present in Azolla microphylla function as both stabilizers and reducing agents during the low-temperature (35 °C) production of Au NPs. 69

Examples of Pteridophytes reported for the synthesis of MNPs.

| Plant species | Plant material | Solvent | Type of MNPs | Reaction temperature | Size (nm) | Shape | Mechanism/causative agent | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiantum caudatum | Leaves | Water | Ag | Room temperature | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | 21 |

| Adiantum capillus-verenis | Whole plant | Water | Ag | Room temperature | 25–37 nm | Spherical | 70 | |

| Pteris argyreae, Pteris confusa and Pteris biaurita | Leaf | Water | Ag | Room temperature | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | 50 | |

| Nephrolepis exaltata | Leaflet extrac | Water | Ag | Room temperature | 10–47 nm | Spherical | 19 | |

| Adiantum philippense L | Leaf | Water | Au and Ag | 30 C | 10–18 nm | 71 |

They further claimed that the hepato-protective and antioxidant qualities of Au NPs were derived from the flavonoids. Their NPs ranged in size from 3 to 20 nm, with an average of 8.3 nm, and had a variety of forms, including spherical, triangular, hexagonal and rod morphologies. 73 The production of Au NPs in a similar work, employing Azolla pinnata aqueous extract as a reducer and stabilizer at 50 °C. The produced nanoparticles (NPs) had two different shapes: spherical, measuring around 20 nm, and rod-shaped, measuring roughly 200 nm. 74 In a related study to synthesized poly-dispersed spherical Ag NPs with a mean size of 6.5 nm in a 5-h reaction time using the complete plant of A. pinnata. They discovered that 1 mm for the precursor and 100 g of plant powder for the dry extract was the ideal concentration for the process. 75

The oldest surviving global bryophytes are the second-largest group of land plants and do not have a circulatory system. Understanding the origins of plants and following their migration to land depend heavily on bryophytes. Similar to Pteridophytes, bryophytes defend themselves from other living things by producing chemicals that are biologically active. These physiologically active substances are used in many different ways as a result of the phytochemical activity of bryophytes. 76 Table 4 shows the bryophytes that are used in the synthesis of MNPs. Studies indicate that the process is made simple by the simple organization of the thallus body of the bryophyte plant. The bryophytes are the least investigated group of plants in the (GS) of MNPs. Used the bryophyte gametophyte extract to create Au NPs at 37 °C, the diameters of the hexagonal, triangular and spherical Au NPs varied from 42 to 145 nm. 80

Bryophytic plants reported for the biosynthesis of MNPs.

| Plant species | Plant material | Solven | Type of MNPs | Reaction temperature | Size | Shape | Mechanism/causative agent | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riccia liverworts | Mature thalli | Water | Ag | Room temperature | 20–50 nm | Cuboidal and triangular | Not mention | 77 |

| Anthoceros | Thallus | 70 % alcohol | Ag | Room temperature | 20–50 nm | Cuboidal and triangular | Not mention | 78 |

| Fissidens minutus | Thallus | 70 % ethanol | Ag | Room temperature | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mention | 79 |

Algae are the three primary needs for producing entirely green metallic nanoparticles: environmentally acceptable solvent system, particle-stabilizing capping agent, and environmentally friendly reducing agent. 81 The biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles by algae is one of them. 82 The algae are aquatic oxygenic photoautotrophs that are eukaryotic. The bio-reduction of algae has great promise for the clean, environmentally friendly synthesis of several metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles such as gold, silver, platinum, palladium, copper oxide, zinc oxide and cadmium sulphate among others. 19 , 83 While several algae have been shown to be able to synthesize different NPs, there is still a lack of knowledge on the principals involved control over the size and shape of the products and knowledge about how to govern these parameters. 84 Because of this, a lot of scientists are very interested in learning more about the biological production of the nanoparticles that algae create. Through evolution of algae have developed the capacity to create complex inorganic extracellular or internal structures. How precisely algal biomass generates intracellular gold nanoparticles is yet unknown. The metal ions are initially trapped on the cell surface by an electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged carboxylate groups on the plant cell surface. 85 Cellular enzymes subsequently decrease the ions, producing nuclei that become larger as more metal ions are reduced. 86 On the other hand, Sesbania drummondii absorbs a lot of Au (III) ions and converts them into other forms of Au (0) inside cells. 87 Both processes happen simultaneously in algae because gold nanoparticles can be extracellular in the media (like in Lyngbya majuscula and Spirulina subsalsa) or intracellular (like in Rhizoclonium fontinale). 88 Gold and silver nanoparticles and nano-plates, among other metal nanoparticles, are particularly interesting for technical applications like cancer hyperthermia and antimicrobials. 89 Strong binding was observed between single-celled green algae and tetra-chloro-aurate ions/silver nitrate, resulting in the formation of algal bound gold/silver that was then reduced to Au (0)/Ag (0). 90 About 88 % of the gold in its metallic state was reduced by the dried alga Chlorella vulgaris, and gold crystals with tetrahedral, decahedral, and icosahedral structures collected on the inner and outer surfaces of the cells. 91 , 92 Outside of cells, gold, silver, and Au/Ag bimetallic nanoparticles are produced using an edible blue-green algae known as Spirulina platensis. 90 , 93 Tetraselmis kochinensis was recently reported to be used to manufacture intracellular gold nanoparticles. 94

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the biomass of the brown alga Fucus vesiculosus may be utilized for the extracellular bio-reduction of Au (III)–Au (0). 95 It was widely known that cyanobacteria could produce internal metallic nanoparticles. 96 The cyanobacteria Oscillatory Willie’s cell included the protein molecule NTDM01, which helped reduce silver ion to metallic silver, which was released from the dead cell. It has also been discovered that different functional groups, such as hydroxyl (–OH) from polysaccharides and different amino acids (like tyrosine) and carboxyl anions (–COOH–) from different amino acids like aspartic acid (Asp), are the most effective for Ag ion reduction and controlling the anisotropic growth of Ag nano-plates. 97 Ag NPs were synthesized in a single step and used as a reducer and stabilizer in an aqueous leaf extract of the seaweed Hypnea musciformis. The majority of the synthetic Ag NPs had a spherical form. 98 Algae have not got much attention on Fe2O3, MgO, NiO, and other nanoparticles as angiosperms and microorganisms like PbS, ZnS and CdS. 99

2.2 Microbes-induced biofabrication of MNPs

These synthesis of MNPs have been created in recent years using chemical and physical methods. 100 Both methods are using the most complicated, expensive and hazardous chemicals to create nanoparticles using laser ablation, aerosol spray, and UV radiation. Although these techniques are widely utilized, the use of harmful substances raises questions. Microbial production of nanoparticles is being investigated as a solution to this issue. 101 Limitations of the physical method for producing nanoparticles. Lower synthesis calls for more energy use, which comes at a considerable cost. Chemical methods, on the other hand, are inexpensive but call for the use of hazardous solvents and leave a chemical contamination trail with the production of hazardous byproducts. 102 In order to produce high-yield, low-cost, and environmentally friendly nanoparticles, a biological technique including bacteria, fungus, yeast, and viruses is used. 100

The synthesis of nanoparticles by microbes is anticipated to be a green chemical approach and a potential area of study for the future. 103 Rapid synthesis and enhanced nanoparticle properties can be attained by facile microbial culture, a wide range of microorganisms, and molecular, cellular, and biochemical processes (Figure 2). 101 In biotechnological processes including bioleaching, bio-mineralization, bio-corrosion and bioremediation, microbial and metal interaction is well known. The characteristics of metallic nanoparticles and nanostructured mineral crystals created by microorganisms are comparable to those of chemically synthesized nanomaterials. 105 Numerous prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses are examples of unicellular and multicellular creatures that create intracellular or extracellular inorganic compounds. By adjusting the culture settings, it is possible to somewhat modify how these inorganic materials develop in terms of shape and size. 106

The figure illustrates the process of biosynthesizing MNPs using enzymatic reduction and stabilization mechanisms within the supernatant. First, enzymes and biomolecules present in the supernatant catalyze the reduction of metal ions, which facilitate the formation of MNPs. This reduction process is important for converting metal salts into nano-sized particles. Subsequently, to prevent agglomeration and ensure stability, the reduced metal particles are effectively stabilized. Similarly, negatively charged molecules present in the supernatant act as capping agents, which encapsulate the MNPs. This capping mechanism contributes further to the stability and properties of the MNPs, enhancing their overall functionality. Adopted from Carrapiço et al. 104 Copyright permission MDPI.

Microorganisms use various sophisticated methods to biosynthesize nanomaterials, relying on complex extracellular and internal mechanisms. 104 The process begins with positively charged metal ions being drawn to the negatively charged components of the microbial cell wall that allow them to bind and enter the cell through membrane proteins or passive diffusion. 107 Once inside, enzymes such as oxidoreductases and metal reductases reduce the metal ions to their elemental form, creating nanoparticles. The distribution of these nanoparticles within the cell depends on the cell’s internal structure and the physicochemical properties of both the nanoparticles and cellular components. 108 , 109 This process provides the unique insight of physiological and biochemical traits of different microbial species in nanoparticle biosynthesis, which underscore the complexity and specificity of the intracellular mechanisms involved in this biogenic process. 110 Here is a quick summary of recent work on the microbial production of metallic nanoparticles (Table 5).

Algae mediated synthesized metallic nanoparticles.

| Algae species | Part used | Solvent used | Reaction temperature | Type of MNPs | Size | Shape | Mechanism/causative agent | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. calcitrans, C. salina, I. galbana and T. gracilis | Cell culture | Water | Room temperature | Ag | 53.1–71 nm | Not mention | ND | 111 |

| Chlorella vulgaris/Scendesmus obliquus | Cell culture | Water | Room temperature | Ag | 8.2 ± 3/nm | Not mention | ND | 112 |

| Jania rubins (Jr), Ulva faciata (Uf) | Cell culture | Water | 70 C | Ag | 7–20 nm | Not mention | ND | 113 |

| Shewanella algae | Cell culture | Water | Room temperature | Au | 10–20 nm | Not mention | ND | 114 |

| Spirulina platensis IPPAS B-256 | Cell culture | Water | Room temperature | Au | 20–30 nm | Sphericals | ND | 115 |

| Sargassum wightii | Cell culture | Water | Room temperature | Au | 8–12 nm | Not mention | ND | 116 |

| Chlorella pyrenoidusa | Cell culture | Water | 100 C | Au | 25–30 nm | Spherical/icosahedra | ND | 117 |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Cell extract | Water | Room temperature | Au | 9–20 nm | Single crystalline | ND | 118 |

| Sargassum bovinum | Cell extract | Water | 60 C | Pd | 5–10 nm | Not mention | ND | 119 |

| Phormidium tenue NTDM05 | Cell extract | Water | Room temperature | CdS | 5.1 ± 0.2 nm | Not mention | The C-phycoerythrin pigmen | 120 |

| Sargassum muticum | Cell extract | Water | 450 C | ZnO | 30–57 nm | Not mention | ND | 121 |

| Bifurcaria bifurcate | Cell extract | Water | 100–120 C | CuO | 5–45 nm | Not mention | ND | 122 |

| Sargassum longifolium | Cell extract | Water | Room temperature | Ag | 40–85 nm | Not mention | ND | 123 |

| Sargassum muticum | Cell extract | Water | Room temperature | Ag | 5–15 nm | Not mention | ND | 124 |

| Anabaena sp. 66-2 | Cell extract | Water | Room temperature | Ag | Not mention | Not mention | C-phycocyanin, polysaccharide | 125 |

| Alphanothece spp. Oscillatoria spp. Microcolius sp. |

Cell extract | Water | Room temperature | Ag | 44–79 nm | Not mention | ND | 126 |

2.2.1. Bacterial and fungus-induced biofabrication of MNPs

In order for essential metals to be released extra-cellular, they must first enter the cytoplasm of bacteria through the wall meshwork and then return there. The cell wall’s peptidoglycans include poly-anions that enable metal to interact stoichiometric-ally with the wall’s chemically reactive groups before depositing inorganically. 127 Anhydride treatment, a chemical technique, can alter the wall with several potential metal binding sites by converting positive charge to negative charge, which is an essential stage in the metal binding process for groups like amines and carboxyl groups. Chemical modifications were made to the carboxyl group of glutamic acid in Bacillus subtilis peptidoglycan, enabling both substantial and easy metal deposition and penetration. 128 Once within the cell, metal deposition can give bacteria a dipole moment to assist them align with the geomagnetic field and can raise concentration by 20,000–40,000 times compared to extracellular concentration. 129

The crystalline and non-crystalline phases of particles are often affected by the cellular intra- and extracellular environment, as well as certain morphological species of bacteria. 130 The mechanism of Fe3O4 crystal formation occurs within cells during the crystal growth mechanism in the presence of hydrates iron-oxide as a precursor. 131 When cadmium ions were included in the growth media, Klebsiella pneumonia was able to produce CdS particles on the cell surface that had a diameter of a few nanometers. Bacterial cell walls might be coated with discrete quantum dots of “CdS, or bio-CdS” as a potential biological barrier to prevent corrosion. 132 This synthesis not only incorporates photochemical and photo physical features for possible bio-semiconductor applications, but it also eliminates the poisonous effects of Cd species. 133

Using B/w the plasma membrane and cell wall, Pseudomonas stutzeri, an isolated strain from silver mine, was able to create cerium nanoparticles. The organic carbon matrix that makes up the biosynthesized crystalline silver particles has characteristic size and form. 134 The optical characteristics may be tailored using a combination of further processing stages, including heat, a change in the volume percent of the metal, and an efficient manufacturing environment. 135 The biologically produced nanoparticles have features that are complimentary to those of traditional thin-film coating processes. Such materials can be employed in optical filters and for the effective conversion of solar photo-thermal energy into energy. 136

The silver resistance of P. stutzeri allows the binding proteins of the cell surface and the pumping system of cellular efflux through the production and accumulation of metal precipitate by metal flux and metal binding. 145 Physical and chemical growth variables, such as particle size, pH, temperature, culture duration, growth media composition, and growth in the presence or absence of light, are critical for the formation of metal nanoparticles and the ability of bacteria to withstand metal ions. 146 Bacteria containing metal can be used to make metal nanoparticles with regulated optical and electrical characteristics; this technology could be useful in the future. 136 In bacterial nanoparticles may be completely isolated and employed in analytical chemistry, metal ion recovery, rheumatology and medication delivery. 141

When H2 was present as an elector donor with the sulfate-reducing bacteria, the generation of Pd (II)–Pd (0) was accelerated, reaching a maximum rate of 1.3–1.4 lmol/min/mg dry cells. The biological Pd has the ability to act as a chemical catalyst, making it useful for potential bioprocessing applications in industrial waste water treatment for one-step metal recovery. 147 , 148 The bio-sorption technique used to recover metals from the environment also produces metal nanoparticles when the metals are bio-reduced. As a result, the industrial synthesis of nanoparticles is becoming more and more interested in bio-sorption combined with bio-reduction for the conversion of heavy metals waste into nanoparticles. 149 , 150

Because living and non-living organisms are used in the biological manufacture of spherical platinum nanoparticles, green nano-factories can serve as an efficient alternative to traditional chemical processes. 151 Although titanium surgical instruments react with human serum to develop cancer cells, nano-titanium may one day be used for gene transfer and cancer therapy through a biological, environmentally safe process involving microorganisms. 152 Table 6 shows the synthesis of nanoparticles with varying sizes and shapes using different bacteria at different sites.

Various strains of bacteria reported for the synthesis of MNPs.

| Microorganisms | Nanoparticle | Localization/morphology | Size (nm) | Shape | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus sp. | Ti | Intracellular | 40–60 nm | Spherical | 137 |

| P. boryanum UTEX 485 | Pt | Intracellular | 30–0.3 nm | Spherical, chains, dendritic | 138 |

| Corynebacterium sp. SH09 | Ag | Cell wall | 10–15 nm | Not mention | 139 |

| Desulfovibrio desulfuricans | Pd | Cell surface | 50 nm | Not mention | 140 |

| Lactobacillus sp. | Au–Ag | Intracellular | 20–50 nm | Hexagonal/contour | 141 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri AG259 | Ag2S | Periplasmic space | <200 nm | Nano-crystals | 142 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | CdS | Cell surface | 5–200 nm | Not mention | 133 |

| Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum | Fe3O4 | Intracellular | 40–50 nm | Octahedral prism | 143 |

| Bacillus subtilis 168 | Au | Inside cell wall | 5–25 nm | Octahedral | 144 |

Fungi have advantages over bacteria when it comes to the rational creation of NPs. Fungi can be used to create nanoparticles that are more tolerably mono disperse than those produced by bacteria and have nanoscale dimensions. Fungi may use extracellular nanoparticle synthesis methods for increased economic viability. In an aqueous solution containing AuCl4-ions, Fusarium oxysporum releases reducing agents into the solution to produce gold nanoparticles. The NADH enzyme is the catalyst for this process XZ. 151 The protein binding those results from the cysteine and lysine residues connecting leads to the long-term stability of the synthesized nanoparticles in solution. This property allows immobilization on matrices or thin films for nonlinear optics and optoelectronic applications. 153 Unlike other fungal species, F. oxysporum has the ability to hydrolyze unknown metals and, in the presence of K2ZrF6, to form crystalline zirconia nanoparticles in aqueous solution. The fungus may also create silica and titania nanoparticles in the presence of aqueous anionic complexes of Si and Ti. The fungal biological system is an ecologically friendly and energy-conserving means of producing metal nanoparticles on a wide scale that may be commercially viable. 154

F. oxysporum has the ability to create Au–Ag nanoparticles with varying molar percentages extracellular when it is exposed to an equimolar solution of AuCl4 and AgNO3. 135 Additionally, under some circumstances, it can produce platinum nanoparticles by forming them between and outside of cells while being exposed to hexa-chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6). 155 Different bacteria, fungi and yeasts isolated from soil and waste samples rich in metals were used to regulate the size and shape of gold nanoparticles by varying the pH and temperature during the growth circumstances. Two fungi, Verticillium lute album and isolate 6–3 produced a range of nanoparticle morphologies by varying the pH and the oxygen content. Operating temperature allows for adjustment of nanoparticle size. 156

Apart from possessing plasmids containing the ‘sil’ gene for big-scale synthesis of silver ion reduction, Aspergillus flavus demonstrated the ability to produce mono-dispersed silver nanoparticles with an average particle size of 8.92 nm. 157 , 158 The extracellular and intracellular processes of the white-rot fungus Coriolus versicolor produced silver nanoparticles in the absence of surfactants and linking agents. If glucose was supplied as a stabilizing component, fungus may manufacture silver nanoparticles that could be used as water-soluble metallic catalysts for living cells. 159 Table 7 summarizes the fabrication of nanoparticles utilizing several funguses of varying sizes and shapes.

Various species of fungi reported for the synthesis of MNPs.

| Fungal species | Nanoparticle | Localization/morphology | Size | Shape | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coriolus versicolor | Ag | Intracellular and extracellular | 25–75 nm, 444–491 nm | Spherical | 160 |

| Aspergillus flavus | Ag | Extracellular | 8.9 nm | Not mention | 158 |

| V. Luteoalbum and isolate 6–3 | Au | Extracellular | <10 nm | Spherical | 105 |

| F. oxysporum | BaTiO3 | Extracellular | 4 nm | Not mention | 161 |

| F. oxysporum | Pt | Extracellular | 10–50 | Triangle, hexagons, square, rectangles | 155 |

| F. oxysporum | Si, Ti | Extracellular | 5–15 nm, 6–13 nm | Quasi-spherical, spherical | 162 |

| F. oxysporum | Au–Ag | Extracellular | 8–14 nm | Not mention | 163 |

| F. oxysporum | Au | Extracellular | 20–40 nm | Spherical, triangular | 153 |

| F. oxysporum | Zr | Extracellular | 3–11 nm | Quasi-spherical | 164 |

2.3 Biofabrication of MNPs using viruses

Creating inorganic nano-crystals with the required arrays over the nanoscale length is a difficult task for bacteria and fungi. Under such conditions, the use of protein cages, DNA-recognizing linkers, and surfactant-built routes is limited. Nevertheless, these limitations are circumvented by the creation of self-assembling/supporting semiconductor surfaces with highly oriented quantum dots (QD) structures and mono-disperse shape and size along the length of nanoparticles. Through molecular cloning and genetic selection, the genetically engineered tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) produces nanoparticles of a certain length. In 3D layered materials, these particles have the ability to align and modify inorganic nano-crystals. 165 High-density synthetic DNA with various medicinal applications may be preserved for up to 7 months without running the danger of bacterial infection thanks to the development of viral films. 166 The use of viruses is the most sustainable and green way to prepare NPs because of their fine structural control, ability to self-assembling, and biocompatibility. The synthesis of different nanoparticles has explored the significance of various viruses in the advancement of GN, emphasizing their applicability in eco-friendly, sustainable synthesis processing because of bio-templates. Viruses have minimum environmental effects to promote sustainability; their application in nanoparticles is one of the views of GN. Viral capsids also facilitate the preparation of nanoparticles, which is a naturally and environmentally acceptable procedure for creating nanomaterials. The viruses’ template of NPs has been investigated as much as possible as an imaging agent, medication delivery system, and therapeutic treatment of targeted cells. 167 These particles are also used in sensor, electronic, and cutting-edge technology; their optical and magnetic properties may be controlled by the exact shape of nanoparticles. 168 , 169 Table 8 illustrates the synthesis of nanoparticles using several viruses with different sizes and shapes.

MNPs synthesized from various viruses.

| Virus type | Nanoparticle type | Size | Localization/morphology | Shape | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M13 bacteriophage | ZnS, CdS | 560,920 nm | ND | Quantum dot nano-wires | 166 |

| Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) | SiO2, CdS, PbS, Fe2O3 | ND | Nano-tubes on surface | ND | 165 |

| Cowpea mosaic virus | Co, Ni, Fe | 35 nm | ND | ND | 170 |

| Tobacco mosaic virus | Ni, Co | 3 nm | Nanowires on surface | ND | 171 |

2.4 Faunal and their derived-based biofabrication of MNPs

MNPs are used for several purposes, such as antimicrobial protection by their interactions with enzymes, proteins, and/or DNA to disrupt cell division. Furthermore, the MNPs may pose a risk to a range of species, including fungi and humans. 172 For usage in biomedical applications such catheters, dental materials, medical devices and implants, cellulose acetate is a great choice because to its hydrophilic, non-toxic, and biodegradable properties. 173 Different synthesis procedures have been developed and summarized elsewhere for the impregnation of metallic nanoparticles in tissue grafts. 174

Medical diagnosis and treatment can be improved by biomedicine and nanomedicine, which creates different biological molecules that do not damage the host tissues. On the other hand, magnetic nanoparticles are used in cancer therapy because they may be engineered to affect tumors. In research employing animal models aids in defining broad guidelines for the effective creation of nanoparticles with therapeutic uses. 175 Reports on MNPs synthesis on animal medium are few best examples is the silk fibroin found in worms and arachnids such as Bombyxmori, which has a restricted ability for catalysis and chemical recognition 176 (Figure 3).

The figure shows the green synthesis of antibacterial and antifungal silver nanoparticles (AF-AgNPs) using a fur extract as the reducing and stabilizing agent. The UV–visible spectrum of the synthesized AF-AgNPs is also shown, which exhibits a characteristic surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak around 420 nm, that confirm the formation of silver nanoparticles. Adopted from Akintayo et al. 177

Polymer nanofibers have been shown to possess unique properties recently, as their unique surface area, minuscule pore widths and ability to function as a microbiological barrier have been utilized in the production of novel materials. The host is administered nanomaterials, such as their physiology and development aspects, in order to measure the cell response. Similar to the aforementioned scenarios, a wide variety of animals might be a source of inorganic materials. Unicellular organisms produce magnetite nanoparticles, whereas multicellular species synthesize inorganic composite materials from simpler ones to construct a variety of structures, including bones, shells, and spicules.

The silk proteins sericin and fibroin, as well as spider silk fibroin, are produced by a variety of insects and spiders. A naturally occurring semi-crystalline biopolymer, silk fibroin is mostly composed of amino acids, such as serine, alanine, and glycine. Silk fibroin has been used in the production of textiles and medical sutures because of its capacity to promote the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of basic cells. Furthermore, making them using films and porous scaffolds is easy. 178 Silk fibroin was used as a material for tissue engineering to regenerate skin, bone, blood vessels, ligaments, and nerve tissue since it is non-immunogenic and non-toxic. It is currently unknown how rapidly silk fibroin degrades, despite several study papers showing that it is biodegradable. 179 Arachnids with the natural ability to make silk include spiders and certain extinct species. Spiders may produce two types of silk: non-sticky, dry, strong strands that serve as the foundation of their webs, and sticky spiraling threads for snagging prey. The only animal silk used in commerce to date is from the silkworm, Bombyx mori and due to its restricted catalytic and molecular recognition. 180

During metamorphosis, several species make silk; for instance, the adult Hymenoptera larva produces silk. A South American tree ant’s mouth cavity-based glands may directly generate silk. Through the use of constructing bags made of sand or plant pieces, Trichoptera larvae manufacture silk. 181 Additionally, a number of nano-composites including fibroin were created, including fibroin-TiO2 and nano-hydroxyapatite/silk fibroin. 15 The crystalline particles that were produced were 100 nm long. Additionally, sericin, which is dumped in wastewater from the silk industry, may be utilized to make NPs. There are methods for recovering it in order to create more nano-sericin particles. Spinning reduces the extracted sericin and produces a concentrated sericin solution. Nano-sericin powder is created following lyophilization and ultra-sonication to decrease the particle size. 182 Among other qualities, these fibres exhibit UV resistance, biocompatibility, resistance to oxidation, and antibacterial activity. 183 Last but not least, spider nets have adhesive nano-filaments that can catch preys using a sticky aqueous glycoprotein. 184

2.4.1 Invertebrate-induced biofabrication of MNPs

Medical applications can benefit from the hardened biological materials present in sponges and starfish because of their form and content similarity to mammalian teeth. The manipulation of biomaterials for the formation of microstructures and stabilization of amorphous minerals is an important field of research. The two most common types of these biomaterials are hydroxyapatite and bio-silica. Collagenous and non-collagenous proteins at the nanoscale make up the majority of hydroxyapatite, a naturally occurring mineral type of calcium apatite that is recovered from fish bone. 185 These proteins have biological uses for bone transplant safety, biocompatibility and osteo-conductivity. The glassy amorphous silica known as bio-silica, or biogenic silica, is created by a variety of aquatic species, including sponges, diatoms, radiolarians, and chino-flagellates. The enzyme silicate in sponges produces the bio-silica. The process is attributed to the appositional stacking of silica nanoparticle-based lamellae. For instance, the application of nano-hydroxyapatite (NHA) in medicine, such as osteogenesis, has been studied. 186

By using thermo-gravimetric created a technique to extract nano-HA from corals. 187 The nano-HA and chitosan were combined in a later development. Additional instances of the creation of nanoparticles from several worm species have been documented. For instance, the reaction between HAuCl4 and the earthworm extract Eisenia Andrei produced nano-red gold radiolarians and chino flagellates. 185 The creation of Ag nanoparticles using a poly-chaeta marine worm solution serves as another example. During the synthesis of silver nitrate nanoparticles, this solution served as a reducing and stabilizing agent. 188

Chitosan, a peptide derived from invertebrate chitin, has multiple uses in various fields. For instance, chitosan nano-fibers having a diameter of 20–40 nm can be utilized to dye fabrics. When paired with polyester materials, it can help reduce static electricity. It can be utilized as a nano-capsule in medicine to deliver cancer treatments and vaccinations slowly. The behavior of a poly HEMA-chitosan-MWCNT nano-composite, which may find application as a carrier for various compounds in the industrial and medical domains. 189 Furthermore, nano-chitosan has environmental applications, such pollutant removal. For example, ZnO/chitosan nano-photo catalysts with a size of less than 4 nm have been produced for the photo degradation of organic pollutants that are dangerous and present in wastewater, as well as for other environmentally beneficial uses.

Furthermore, chitosan-polyacrylic acid (PAA) nanoparticles with a diameter of 50 nm were produced. 190 This material shows antifungal activity against three species of fungus (F. oxysporum, Fusarium solani, and Aspergillus terreus) and inhibits the egg deposition of several insect species, including Aphis gossypii and Callosobruchus maculatus, which frequently damage soybean, crops. 191 Another intriguing usage was revealed, who extracted cadmium from wastewater by using nano-sized hydroxyapatite/chitosan composite sorbents. Its adsorption efficiency is around 122 mg/g, according to Salah et al. 192 It has been demonstrated that magnetic graphene/chitosan is useful in eliminating various chemical dyes because of the quantity of hydroxyl and amino groups in chitosan and the magnetism of Fe3O4. 193 Bentonite-chitosan nano composites are also very good in absorbing and getting rid of synthetic dyes. A combination of TiO2 and chitosan was demonstrated to be efficient in eliminating organic contaminants from waste waters while preserving a substantial portion of its photocatalytic activity after ten cycles. 194 This information was obtained recently, Under UV light, nano-ZnO quantum dots and chitosan have comparable applications. 195

3 Advantages and disadvantages of biological and chemical synthesis of MNPs

The physical methods have been used for the synthesis of various nanoparticles through preparation processes like lithography, thermal evaporation, ball milling and vapor deposition phase, while the chemical solutions form the basis of the widely used hazardous chemical techniques. These chemical techniques include chemical reduction, irradiation, pyrolysis, electrolysis and sol-gel processing. Previous research using both physical and chemical methods demonstrated that the physicochemical properties of metal nanoparticles, such as size, morphology, stability, and reactivity, are significantly influenced by the experimental conditions as well as the kinetics of interaction between metal ions and reducing agents and the adsorption between stabilizing agent and metal nanoparticles.

Consequently, in both physical and chemical synthesis, the design parameters are optimized for stability, size and form. 196 The main biological process makes use of a variety of microorganisms, such as bacteria, yeast, and fungi, in addition to plant extract synthesis. The biogenesis of metallic nanoparticles occurs when the microbe absorbs target ions from its environment and transforms the metal ions into the element metal. During this phase, both extracellular and intracellular processes may occur. 197 Previous sections that describe the process and related yields have covered all biological models for creating nanoparticles in detail.

Chemical synthesis is the most widely used method for producing metallic nanoparticles. Although the use of nonpolar solvents and a variety of dangerous chemicals during the synthesis process limits the application of chemically produced nanoparticles in the clinical and biological domains. Hazardous materials are used in several of these chemical processes as final capping agents and synthetic additives. 198 , 199 Another big drawback of chemical processes is their high energy and financial requirements. The use of toxic chemicals in the synthesis process will cause them to end up in environmental compartments like soil and water, along with other hazardous byproducts, which is cause for worry. 200 Therefore, the search for sustainable and ecologically friendly methods of producing metallic nanoparticles resulted in the synthesis of nanoparticles using biological means, albeit at a lower yield at this time. 201 Nanoparticles may be produced from simple prokaryotic bacteria to eukaryotic fungi and plants. 202 This allows it to be more flexible than chemical processes because biological activities don’t need energy, benign and may be carried out in environmentally friendly situations.

In addition, the process is environmentally clean, green and eco-friendly because it doesn’t use any dangerous chemicals or solvents. These “bio products” are safe to use in biomedical and therapeutic contexts. Very stable and well-characterized nanoparticles may be created biologically by optimizing key parameters such as the types of organisms utilized, cell growth, enzyme activity, optical growth, reaction conditions and the appropriate biocatalyst. 203 Removal of stabilizing agents from biologically generated nanoparticles is another step towards “green synthesis” and is enabled by the presence of proteins and the enzymes secreted by bacteria. 204 Furthermore, NPs made organically have a higher poly-disparity than NPs made chemically. The fundamental properties of the NPs, including their electrical, optical, magnetic and catalytic activities are determined by their size and shape. The simplicity of controllability of biological systems makes biological nanoparticle manufacturing superior to chemical synthesis. 205

However, the length of production is the primary problem with biologically synthesizing nanoparticles, and this has to be investigated further. As they develop in their native environments, microbes create nanoparticles due to biological production and toxicity. Concerns regarding a target being toxic during the production of biological nanoparticles are quite rare. The biosynthesized NPs have several applications including targeted drug administration, cancer treatment, gene therapy, DNA analysis, antimicrobial agents, biosensors, higher response rates, separation science, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). 206 , 207 This broad variety of applications cannot be achieved via chemical synthesis since hazardous chemicals are used in the preparation process. The biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles seldom involves the use of organic solvents or inorganic salts, making the process “green.” However, in particular situations, such synthesis and extraction in non-aqueous situations its might be difficult to avoid utilizing organic solvents. Thus, it is imperative to investigate the feasibility of employing alternative ecologically benign solvents such as water. 208

4 Effect of MNPs on environment

Nanoparticles can position a threat to the environment since they are hazardous to a wide range of animals, including humans. Since the dawn of time, dust storms, volcanic ash and other natural phenomena have exposed humans and other living things to minute particles. The creation of anthropogenic nanoparticles has increased dramatically since the industrial revolution. Nonetheless, manufactured and synthetic nanoparticles have raised awareness of nanoparticles in relation to environmental deterioration in recent years. 209 The environment of most organisms is continuously interacting with a small number of critical organs. For example, human skin, lungs and digestive system are in continual contact with the environment. Compared to the skin, the lungs and digestive system are more vulnerable to NPs. 210 Because of their nanoscale size, NPs can move from entry points into the lymphatic and circulatory systems to body tissues and organs. The extent to which certain nanoparticles cause oxidative stress and death of organelles in cells depends on their size and makeup. 211

Numerous parameters, such as dose, size, surface area, concentration, particle chemistry, crystalline structure, aspect ratio, and surface tension, can lead to the toxicity of metallic nanoparticles. 212 Furthermore, it is critical to comprehend that not all nanoparticles pose a threat and that, in addition to particle size and age, toxicity is influenced by elements including chemical composition and structure. 213 Certain types of nanoparticles may be rendered harmless and many of them show no harmful effects at all, while others have advantageous impacts on health. 214 Fe2O3 nanoparticles have been used for separating magnetically arsenic from unusable water. CuO NPs may contain a broad range of effective bacteria, which improves the disinfection of water systems. 215 The uses of TiO2 NPs in photocatalytic water treatment show their effectiveness in degrading pollutants like methylene blue under ultraviolet irradiation, while ZnO NPs involve strong antibacterial activity against a variety of pathogens, making them suitable for environmental sanitation. 216 Furthermore, in addition to fundamental categories of physical behavior and resultant toxicity, research into the toxicological properties of each material as well as particle ageing must be prioritized in order to collect trustworthy data to assist future policy and regulatory procedures. 217

5 Characterization techniques

Many methods are employed to determine the structural properties of the NPs once they are produced to including surface morphology, disparity, size, shape and homogeneity. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier transmission infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX), UV–vis absorption spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), dynamic light scattering (DLS), etc. are techniques that are commonly used to characterize nanoparticles (NPs). 218 UV–vis spectra were used to analyze the shape and size of NPs in an aqueous solution. 219 Generally, wavelengths between 300 and 800 nm are used to characterize NPs with diameters between 2 and 100 nm. 220 Significant UV absorption spectra were obtained from the surface Plasmon resonance of the ZnO particles made using aloe vera extract, with the absorption peak falling between 358 and 375 nm. 221 Generally, NPs’ size and form are described using TEM and SEM. 222 Electron microscopy analysis revealed ZnO NPs (25–55 nm) in line with the XRD studies. 223 For SEM and TEM analysis, green synthesized carbon nanotubes were completely encased in layers of polyaniline. 224 , 225 . During TEM analysis, TiO2 particles were often spherically agglomerated in the 10–30 nm range. Furthermore, the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) analysis disclosed a crystalline form. 223

XRD provides information on size, phase, and translational symmetry. XRD may be used to assess the size, phase, and translational symmetry of metallic NPs. 225 , 226 The structure is ascertained by penetrating the nanomaterials with X-rays and comparing the resulting diffraction pattern to reference materials. XRD peaks at angles (2 h) of 28.51, 33.06 and 47.42, respectively, which correspond to the 111, 200, and 220 planes and the standard diffraction peaks, show that CeO2 NPs are in their face-center cubic phase. 227 The presence of Pb NPs’ crystalline pattern and their average particle size of 47 nm were shown using the Scherer equation in an XRD investigation. 228 , 229

One can make use of the kinds of functional groups or metabolites that FT-IR spectroscopy reveals to be present on the surface of NPs. 230 Functional group bands detected at 3,450, 3,266, and 2,932 cm−1 for NPs utilizing Aloe vera leaf extracts have been ascribed to the amines’ stretching vibrations, alcohols’ O–H stretching, and alkanes’ C–H stretching. ZnO is responsible for peaks in the 600–400 cm−1 range. Peaks at 1,648, 1,535, 1,450, and 1,019 cm−1 were seen in the FT-IR spectrum when Ag NPs were created using Solanum torvum leaf extract. Ag NP stabilization was attributed to the peak of carboxylate ions at 1,450 cm−1. 231 The DLS and EDX are used, respectively, to examine the size distribution dispersed in liquid and the elemental components of NPs. 232

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis is a crucial technique for characterizing the surface area and porosity of biogenic metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. 233 , 234 This method involves nitrogen gas adsorption and desorption on the nanoparticle surface, with the data obtained used to calculate specific surface area using the BET equation. 235 BET analysis provides vital insights into surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of biogenic nanoparticles, essential for understanding their physicochemical properties and applications like catalysis, adsorption, and environmental remediation. A high specific surface area, determined through BET analysis, is particularly desirable for enhancing the reactivity and efficiency of nanomaterials in various applications. 236

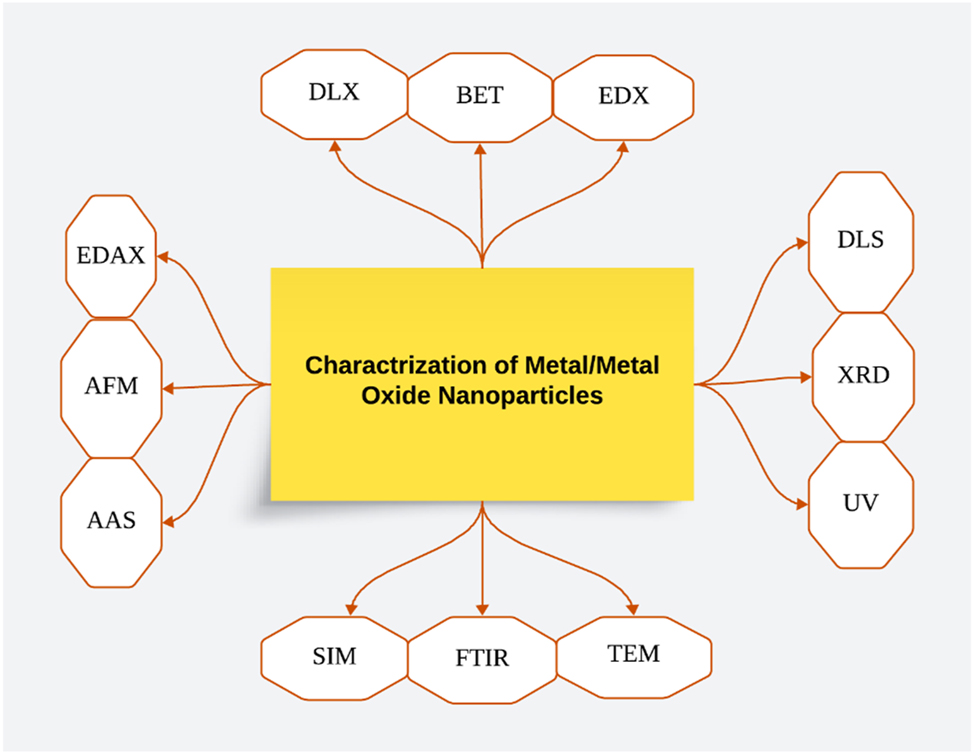

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDAX), and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) are crucial techniques for characterizing MNPs nanoparticles. AAS, as discussed in Kumar et al., 237 is used to determine the elemental composition of nanoparticles by measuring the absorption of specific wavelengths of light. EDAX, mentioned in Bushell et al., 238 provides information on the elemental composition and distribution within nanoparticles. AFM, as detailed in Liu et al., 239 is instrumental in observing the surface morphology and mechanical properties of nanoparticles, offering insights into their structural characteristics. 240 These techniques collectively enable researchers to analyze the elemental composition, size, shape, and mechanical properties of metal/metal oxide nanoparticles, providing valuable information for a deep understanding of their properties and potential applications (Figure 4).

A representative sketch of the various techniques characterizing metal/metal oxide nanoparticles. (Created with Lucidchart.com).

6 Applications

There has been a notable surge in the number of academic papers on nanotechnology throughout the last ten years. Green synthesis-produced nanomaterials are crucial for the use of nanotechnology in many different fields. 241 The green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles has enabled the development of a wide range of biocompatible and environmentally friendly nanomaterials with diverse biomedical applications. 242 , 243 In the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, metallic nanoparticles produced through green synthesis have demonstrated enhanced biocompatibility, making them suitable for use as materials in tissue engineering scaffolds. 244 , 245 Moreover, green-synthesized nanoparticles can be employed as drug delivery vehicles due to their improved biocompatibility and stability, that provide a promising avenue for targeted drug delivery. 246 For instance, PEI-associated MTB-NPs are used to distribute b-galactosidase plasmids both in vitro and in vivo. Magneto tactic bacteria (MTB) nanoparticles are used for gene delivery. 247

Another significant application of green-synthesized nanoparticles lies in their antimicrobial and antiviral properties. 248 Silver, copper oxide, and other metal/metal oxide nanoparticles produced through green synthesis have shown some strong antimicrobial, antifungal, and antiviral activities, making them valuable for various biomedical and healthcare applications. 246 Small interfering RNA (siRNA) and quantum dots were co-transfected using standard transfection methods to produce photo stably fluorescent nanoparticles (NPs). These may be used to monitor the transport of nucleic acids, the degree of cell transfection, and the isolation of uniformly silenced subpopulations. 249 HIV infection may be prevented and treated with the help of this particular NP interaction, which prevents the virus from attaching itself to host cells. The HIV-1 virus adheres rapidly to NPs on gp120 glycoprotein knobs with a size range of 1–100 nm. Nanoparticles have the ability to destroy cell walls and membranes. 250 They may also release free radicals that harm DNA, induce oxidative stress, or disrupt the electron transport chain, which kills bacteria. The mechanism of NP toxicity against bacteria and a picture of cellular absorption. 251 Furthermore, certain green-synthesized nanoparticles have demonstrated anticancer properties, as they can induce apoptosis and disrupt cellular processes in cancer cells. 242

Environmentally friendly NPs have superior antibacterial, antifungal and anti-parasitic properties. 252 To remove viruses from drinking water, biogenic silver generated by Lactobacillus fermentum has been used to form green nanoparticles. 253 Two commercially available household water filtering systems that use silver as a disinfectant are Aquaporin and QSI-Nano. 254 According to these eco-friendly techniques, contaminated landscapes and hazardous waste sites are cleaned by organisms and their byproducts, or NPs. 229 In the process of treating wastewater that has been tainted by organic pollutants, surface and groundwater, and toxic metal ions. 223 , 255 . Many of the cleaning chemicals used in routine maintenance procedures may be replaced with self-cleaning nanoscale surface coatings. Fe NPs are gaining a lot of attention because of their quickly evolving uses in heavy metal cleanup and water disinfection. Nanoparticles are useful fertilizers and pesticide substitutes in the management and prevention of plant disease. 256 They preserved the environment and increased agricultural output. Magnetite (Fe3O4)/greigite (Fe3S4) and siliceous material made from diatoms and bacteria respectively, are useful materials for ion insertion in electrical battery applications and optical coatings for solar energy applications. 257 Chemical reactions are more productive and less wasteful when nanoscale catalysts are used. 258

7 Conclusion and future directions

The concept of Green synthesis is a comparatively new knowledge and in developing areas to synthesizing the nanoparticles. The re-evaluation of animals, plants, and microorganisms for green synthesis has indeed revolutionized the fabrication of MNPs. This approach, using natural sources, significantly reduces reliance on hazardous substances and facilitates the conversion of metallic ions into neutral atoms. The biocompatibility of MNPs synthesized through green methods surpasses that of chemically synthesized counterparts, highly suitable for diverse biological applications, particularly in biomedicine.

Extensive research has been conducted on various organisms for green synthesis, resulting in the production of MNPs such as Au, ZnO, CuO, Pd, Pt, Fe, MgO, and NiO. Bacteria, viruses, and fungi also serve as valuable sources of reducing agents, which expand the possibilities for green synthesis. Despite progress, research on natural reducing agents remains relatively limited, with only a few substances like tea and neem plants receiving substantial attention. Furthermore, GS MNPs have found diverse applications across various fields. In biomedicine, they facilitate drug delivery, targeted therapies, and bio-imaging due to their enhanced biocompatibility. Moreover, certain MNPs demonstrate potent antimicrobial properties, which contribute to disease control and eco-friendly disinfection. Furthermore, green nanoparticles play an important role in environmental remediation by purifying water and function as sensitive biosensors for diagnostics and environmental monitoring.

The following are some of the main points of biological synthesis:

It was unclear how the biologically synthesized nanoparticles worked mechanistically. Therefore, future research must focus on the proteins and enzyme systems involved in the production of nanoparticles. In comparison to their chemical counterparts, the characteristics of the synthesized NPs must also be thoroughly examined.

The downstream processing of MNPs is another area that has not been well studied. These processes for the metal NPs and their primary production have included different essential stages in downstream processing in order to be purified and isolated. These areas involve different steps like separation, purification, characterization tools, and green synthesis methods that assure that the finished product will be free of contaminants and of suitable quality. Currently, innovative and conventional approaches have been highlighted in order to increase the sustainability and efficiency of nanoparticles. 259 This procedure comprises removing any contaminants, such as the microorganisms themselves, from synthesized nanoparticles. It should be noted that most chemical purification methods must be avoided in order to keep nanoparticles non-toxic. Physical processes including centrifugation, freeze-thawing, heating, ultrasound, and osmotic stress can all be studied.

The biological production of metallic nanoparticles has primarily been done in laboratories up until now. Large-scale production needs industrial scale optimization. These “bio-nano-factories” may manufacture different stables (NPs) with well-known shape, sizes, compositions, and morphologies when given the right optimized circumstances and the right microorganisms. The biological system is capable to generating a nontoxic MNPs will be created as a result of the commercialized methods, marking another step towards sustainable development.

Another aspect that needs to be taken care of for the process to be sustainable is cost effectiveness. Comparing economic studies to the commonly utilized chemical methodologies is necessary. As was already indicated, to meet industrial feasibility, large-scale biosynthesis of nanoparticles needs to be carried out. For instance, the cost of different consumable chemicals, including stabilizing, reducing agents and salts among others, makes up the majority of the cost of chemical synthesis. Similar to biological production, metal salt and the medium for microbial growth will be quite expensive. Recycling waste products could be a solution in this situation to cut costs. With trash recycling and value addition, this strategy may be viable.

Future research must emphasize nanoparticles’ quick production. It’s intriguing that some study is being done in this area already. 204

Recent research suggests that green chemistry principles may be successfully used for the biological production of nanoparticles, 19 which will be a huge step towards sustainability and a “green future.”

-