Ethanol as an Antifungal Treatment for Silver Gelatin Prints: Implementation Methods Evaluation

-

Chloé Lucas

Chloé Lucas is a photograph conservator based in Ottawa, Canada. She graduated in history of art from the Sorbonne University in 2012. It was followed by a five year degree in photograph conservation at the Institut National du Patrimoine, from which she graduated in 2016.Institut national du patrimoine, 124 rue Henri Barbusse, 93 300 Aubervilliers, France, Franck Déniel

Frank Déniel has been a mycology engineer in service for provision of agro-food and cosmetic industries at EQUASA of University of Brest for the past fifteen years. He has developed an expertise in fungi identification in the laboratory based of molecular, microscopic, classic method, and on control of those microorganisms in different kind of environmental, agricultural, food sector.Étude en Qualité et Sécurité des Aliments (EQuASA), Centre de Ressources EQuASA ESIAB, Technopôle Brest Iroise, 29 280 Plouzané, France.Dr. Philippe Dantigny is an engineer in Food Processing and Master Degree in Food Microbiology (1985). He got his PhD in 1989 in Biochemical Engineering at the National Polytechnics of Lorraine, Nancy, France. After post-doctoral work, he was appointed as a lecturer in biochemical engineer at the University of Bath, UK. Since 1991, he is a senior lecturer at the University of Lyon, France in food microbiology, and biotechnology. He is the head of the Predictive Mycology group at the LUBEM. He has been member of the French Food Safety Authority for eight years– Biohazard group, expert in Predictive modelling/Food spoilage/Mycotoxins contamination/Fermentations. Dr. Philippe Dantigny has coordinated 1 FP6 project and participated in another EU project. The group of Dr Philippe Dantigny has developed specific modelling tools for fungi, and more generally a new topic named “Predictive Mycology” which aims at understanding and modelling germination, growth and production of mycotoxins in food and agricultural products.Laboratoire Universitaire de Biologie et d’Écologie Microbienne (LUBEM), Avenue du Technopole, 29 280 Plouzané, France.

Abstract

This study deals with mold damaged photographic gelatin disinfection methods. The goal of the study is to determine a suitable method to apply a solution of deionized water and absolute ethanol (30:70 v/v) mixture in order to obtain a biocide effect on four fungal strains: Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium globosum and Penicillium brevicompactum. Three implementations were tested: solvent chamber, direct contact and direct contact followed by a mechanical removal. Different treatment times were tested for each method. The deionized water and absolute ethanol mixture, applied for two hours in a solvent chamber, succeeded in inactivating the four tested fungal strains.

Zusammenfassung

Ethanol als Fungizid zur Behandlung von Silbergelatine-Fotografien: Untersuchung unterschiedlicher Implementierungsmethoden

Diese Studie beschäftigt sich mit durch Schimmel geschädigter, fotografischer Gelatine und Methoden zu deren Desinfektion. Das Ziel der Studie ist es, eine geeignete Methode zur Anwendung einer Mischung aus deionisiertem Wasser und absolutem Ethanol (30:70 v/v) zu bestimmen, um eine Biozidwirkung auf die folgenden vier Pilzstämme zu erhalten: Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium globosum und Penicillium brevicompactum. Es wurden drei Implementierungen getestet: Lösungsmittelkammer, direkter Kontakt und direkter Kontakt gefolgt von einer mechanischen Abnahme von Sporen und Myclien. Für jede Methode wurden unterschiedliche Behandlungszeiten getestet. Mit einer Mischung aus deionisiertem Wasser und absolutem Ethanol, die zwei Stunden lang in einer Lösungsmittelkammer einwirken konnte, gelang es, die vier getesteten Pilzstämme zu inaktivieren.

Résumé

L’éthanol comme traitement antifongique pour des épreuves à la gélatine argentique: mise en oeuvre, méthodes, évaluation

Cet article a pour sujet la désinfection de tirages gélatino-argentiques altérés par des moisissures. L’objectif de cette étude est de déterminer une méthode de mise en œuvre d’un mélange eau déionisée – éthanol absolu (30:70 v/v) adaptée au traitement des photographies gélatino-argentique. Trois méthodes de mise en œuvre ont été testées: par vapeur, par contact et par contact suivit d’un retrait mécanique sur quatre souches fongiques : Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium globosum and Penicillium brevicompactum. Plusieurs temps de traitement ont été testés pour chacune des méthodes de mise en œuvre. Le mélange eau déionisée – éthanol absolu, appliqué pendant deux heures sous la forme de vapeurs dans une chambre de solvants a permi l’inactivation des quatre souches testées.

1 Introduction

For photographic collections, fungal development is a recurring problem. Most photographs are easily used as a substrate for fungal growth because they are made of proteinaceous materials such as gelatin or albumen, and polysaccharides such as cellulose; both material groups also being hygroscopic materials. Fungal development can result in the loss of parts or the totality of the photographic image by hydrolysis of the substrate (paper and colloid). The prevention of such damages can be done with a strict control of the storage climate to avoid fungal growth; however what are the options once the fungi have developed?

In France several antifungal treatments are used. For example, treatments using ethylene oxide or gamma ray have been the subject of various research projects and are used to treat fungi in archival collections.

Ethylene oxide fumigation is very efficient in killing fungi, insects, and bacteria (Flieder and Capderou 1999, 144–151); however it can cause damage to photographic prints. The gelatin peptic chains are broken, thus resulting in a high viscosity loss (Tomsŏvá et al. 2016). As well, cellulosic materials are more hydrophilic after treatment, resulting in a higher sensitivity to further fungal attacks (Jacek 2004; Valentin 1986; Nittérus 2000a, 22–40). Ethylene oxide is also a very toxic compound: mutagen and carcinogenic for humans, it is forbidden to use in North America and several European countries (Trehorel 1988).

The dose of gamma rays needed to inactivate fungi is not consensual, and ranges from 4.5 kGy to 18 kGy (Flieder and Capderou 1999; Pavon Flores 1975). Gamma rays also cause damage to photographic gelatin, such as viscosity loss after an exposure of 2.5 kGy of radiation (Tomsŏvá et al. 2016) and increase of the print’s density after an exposure of 90 kGy of radiation (Adamo et al. 2012). Even if this dose is much higher than the one needed to kill the fungi, it is important to keep in mind that exposure to gamma rays is cumulative. Thus if a photograph is treated several times in its life, the 90 kGy dose will be attained at some point. The radiation also degrades the photographic paper support which presents damage similar to the one caused by ageing (weakening and yellowing), resulting from cellulose depolymerisation and oxidization (Butterfield 1987; Nittérus 2000a, 25–40).

These two treatments are costly and more adapted to large collections. So, what are the available options for treating single items or a small collection of photographs? Today, photograph conservators use pure ethanol or a deionised water–pure ethanol mixture of different ratios applied on the surface of the prints with a cotton swab. This method, while widely used, has not been tested and its fungicidal effects have not been studied. There is some research on the use of alcohols as a fungicide for paper objects. The use of a water-ethanol mixture with a 30:70 (v/v) ratio is the most recommended (Nittérus 2000b, 101–105; Jacek 2004; Meier 2006; Sequeira et al. 2016), however authors disagree on its most effective implementation method between spraying, bathing, and vapour fumigating (Nittérus 2000b, 101–105; Bacílková 2006; Meier 2006).

In this study, we intended to clarify which implementation method of water-ethanol (30:70 v/v) mixture inactivates fungal growth on silver gelatin prints. Three implementation methods of this mixture were tested. In order to check if the cotton-swab application, corresponding to a short contact time with mechanical action, was efficient or not, we chose to test a short direct contact between the mixture and the photograph, with and without mechanical action, to determine the influence of this factor. The use of the mixture as vapour, previously tested, was chosen as our third implementation method because of the treatment possibilities it opens, such as treating photographs whose surfaces are too damaged for contact, and treating several photographs at the same time. Those three methods are not representative of today’s practice in conservation labs but correspond to three levels of intervention on the prints: without contact, with contact, and with contact and mechanical action.

Various fungi have been identified on silver gelatin prints; however, as the sampling is done with swabs, the identified species may not be the ones responsible for the prints’ deterioration (Sclocchi et al. 2013). For this study, four fungal species were selected within the most common encountered species on photographs (Lucas 2016, 289–294): Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium globosum, and Penicillium brevicompactum.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Silver gelatin prints

Developing-out silver gelatin prints were selected as they are the most widely used black and white photographic printing technique throughout the 20th century. It was used by amateurs and professional photographers, thus it can be found in private and public, archival and museum collections.

Glossy Ilford® Multigrade Classic baryta paper was selected for the tests. This paper is constituted of three layers: paper, baryta (barium sulphate in gelatin), and gelatin emulsion containing light sensitive silver halides. We decided to print a neutral light grey colour in order to work on a binder including metallic silver without impeding the observation of the fungal development on the emulsion.

The paper was exposed with an enlarger Omega® Super Chromega D Dichroic II for six seconds at f/32 without a contrast filter. It was developed with Kodak® Dektol (1:2 v/v) for two minutes, then immersed into a Tetenal® Indicet stop bath (1:19 v/v) for thirty seconds before fixing it for four minutes with Ilford® Rapid Fix (1:4 v/v). The print was then washed with cold flowing water for an hour and air dried overnight.

The print was cut in square samples of 2.5 cm length. The samples were not sterilized because the autoclave temperature would have damaged the constituents.

2.2 Fungal strains

Four fungal strains were used in the present study: Alternaria alternata FD412, Aspergillus niger FD255, Chaetomium globosum FD477, and Penicillium brevicompactum FD487, from the mycological collection of the LUBEM (Plouzané, France). These strains were identified on the basis of sequence analysis. Ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (rDNA ITS) was used for identifying FD412 (accession number KY977416) and FD477 (accession number KY977415) whereas a portion of the beta-tubulin gene sequence was used for FD487 (accession number KY985235) and FD255 (accession number KY886458).

2.3 Inoculum preparation

The cryopreserved strains were thawed, then plated on M2Lev medium (for 1 L of water: 20 g malt, 3 g yeast extract Biomerieux®, 15 g agar Biomerieux®) and incubated at 25 °C for seven to ten days. Spores were then harvested with a sterile sampling loop and suspended in 20 % glycerol water, with two drops of Tween® 80 (Sigma-Algdrich®). The concentration of 5 x 107 spores/mL was determined with a haemocytometer. The suspension was diluted with sterile water in order to obtain a 5 x 105 spores/mL inoculum.

2.4 Sample contamination

Each sample was inoculated with 10 μL of the inoculum. The samples were placed in Petri dishes, three samples per dish, with the gelatin emulsion facing up.

The Petri dishes were placed over 300 mL of sterilized water in a closed Ikea® 365+ Food container (polypropylene and synthetic rubber) and incubated at 25 °C for seven days. The Petri dishes were then removed from the box and incubated one more day to allow the gelatin emulsion to dry.

2.5 Ethanol implementation method

A mixture of sterilized water-absolute ethanol Carlo Erba Reagents® (30:70 v/v) was used as the treatment solution for the tests. The tests were conducted at a controlled temperature, between 15 °C and 18 °C.

2.5.1 Control samples

For each strain, three samples were contaminated but not treated with the treatment solution to serve as control samples.

2.5.2 Ethanol vapours

The Petri dishes containing the samples (three each) were placed open over 350 mL of the treatment solution in a closed Ikea® 365+ Food container. The container dimensions were 34 x 25 x 12 cm.

Several exposure times were tested: 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 hours. Those times were chosen based on previous research (Bacílková 2006; Dao et al. 2010).

2.5.3 Direct contact

The sample was transferred in a clean Petri dish with the emulsion facing up, a 2.5 cm long square of sterilized Atlantis® microfiber cloth was placed on top. 300 mL of the treatment solution was added to the cloth with a pipette (the quantity has been determined empirically as the one required to soak the cloth). The Petri dish was closed to limit evaporation.

Several contact times were tested: 15 seconds, 30 seconds, 1, 2, 4 and 8 minutes. These times are shorter than the vapour treatment times in order to be comparable to the conservation lab practice with cotton swabs.

After the contact time, the cloth was removed by pulling it off gently.

2.5.4 Direct contact followed by a mechanical removal

The treatment solution was applied in the same way and with the same contact times as the direct contact. The removal was done by swiping the cloth once over the emulsion.

2.6 Evaluation of fungal inactivation

Once treated, the sample was placed with the emulsion down on M2Lev medium (for 1 L of water: 20 g malt, 3 g yeast extract Biomerieux®, 15 g agar Biomerieux®), and then incubated at 25 °C.

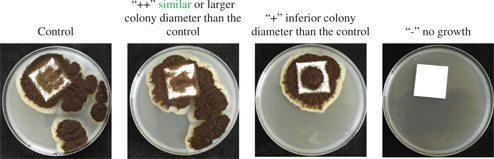

The colony diameter was observed visually after seven days. Its diameter was assessed qualitatively in comparison to the diameter of the untreated control samples. The samples were marked as “++” when the colony diameter was similar or larger than the control, “+” when inferior than the control, or “-” when no growth was visible (Figure 1).

Example of colony diameter for Aspergillus niger.

When no growth was observed after seven days of incubation, the samples were incubated for an additional seven days and the colony diameter was observed again.

3 Results

3.1 Ethanol vapour implementation

The results for the fungal growth at seven days after the water-ethanol vapour treatment are summarized in Table 1. This treatment prevented the fungal growth after seven days for all strains after two hours of treatment. A. alternata and P. brevicompactum are inactivated after one hour.

Fungal growth at seven days (25 °C) after water-ethanol vapour treatment (350 mL/0.1 m3).

| Strains | Treatment times | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 8 h | 16 h | 24 h | |

| Alternaria alternata | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Aspergillus niger | ++ | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chaetomium globosum | + | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | ++ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Evaluation: “++” similar/larger colony diameter than the control, “+” inferior colony diameter than the control, “–” no growth.

3.2 Direct contact implementation

The results for the fungal growth at seven days after the water-ethanol direct contact treatment are summarized in Table 2. From 15 seconds to 2 minutes of treatment, all strains resumed growth, A. alternata was inactivated after 8 minutes, and P. brevicompactum after 4 minutes.

Fungal growth at seven days (25 °C) after direct water-ethanol contact treatment (300 μL/6.5cm2).

| Strains | Treatment times | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 s | 30 s | 1 min | 2 min | 4 min | 8 min | ||

| Alternaria alternata | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | |

| Aspergillus niger | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Chaetomium globosum | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | – | – | |

Evaluation: “++” similar/larger colony diameter than the control, “+” inferior colony diameter than the control, “–” no growth.

3.3 Direct contact followed by a mechanical removal implementation

The results for the fungal growth at seven days after the water-ethanol direct contact treatment and mechanical removal are summarized in Table 3. Up to 4 minutes of treatment, all strains resumed growth. At 8 minutes, A. alternata and P. brevicompactum did not grow.

Fungal growth at seven days (25 °C) after direct water-ethanol contact and mechanical removal treatment (300 μL/6.5cm2).

| Strains | Treatment times | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 s | 30 s | 1 min | 2 min | 4 min | 8 min | |

| Alternaria alternata | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | – |

| Aspergillus niger | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Chaetomium globosum | + | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | + | + | + | + | + | – |

Evaluation: “++” similar/larger colony diameter than the control, “+” inferior colony diameter than the control, “–” no growth.

3.4 Growth at fourteen days

The results obtained with the direct contact implementations are the same after fourteen incubation days, i. e. the samples do not resume growth. Concerning the ethanol vapour implementation, A. alternata and A. niger samples do not resume growth; the P. brevicompactum samples treated for one hour resumed growth whereas no growth was visible at seven days; and the C. globosum sample treated for one hour shows a growth similar to the control sample. All samples treated for two hours or more are inactivated.

4 Discussion

One of the major interests of the present study was the antifungal treatment of artificially contaminated silver gelatin prints. The development of all the tested species within a week at 25 °C demonstrated that rapid decontamination (within 48 hours), or at least preservation, of photographs after flooding is required to avoid fungal growth.

Fungal species are, in general, cellulolytic. This was shown for C. globosum and A. niger (Lakshmikant 1990), and P. brevicompactum and A. alternata (Méheust 2012), but these species were also potentially capable of degrading gelatin. P. brevicompactum (Bingley and Verran 2013), A. alternata (Abrusci et al. 2006), and some isolates of C. globosum (Lech 2016) proved to degrade gelatin. We did not find any reference on the existence of gelatinase positive isolates among A. niger because this species is recognized as a high amylase producer; however, many other Aspergilli such as A. versicolor (Abrusci et al. 2005), A. ustus, and A. nidulans (Abrusci et al. 2007) were found gelatinase positive. It is suggested that all the species tested in the present study were cellulolytic, but it was not determined whether they were also gelatinase positive.

The protocol allowed determination of fungal inactivation by ethanol vapours. Fungi are strictly aerobic organisms, however they can grow with oxygen levels as low as approximately 2 % depending on the species (Nguyen Van Long and Dantigny 2016). Control samples demonstrated that the species grew at the surface of the agar medium, even if the sample was turned upside down, with the print over the mycelium. Therefore negative experiments that did not exhibit growth were not due to oxygen limitation but to fungal inactivation. Prior to ethanol treatments, the samples were entirely covered with mycelium and conidia. It can be expected that treatments that proved effective in the present study against heavy inoculum will be even more effective against lighter inoculum.

The obtained results depend on the different tested strains. Indeed each strain has a different growth speed and sensitivity to external agents. For instance, C. globosum’s ascospores are contained into perithecias, which makes the spores more resistant to external agents. In this experiment, A. niger and C. globosum showed more resilience to every tested treatment compared to the two other tested strains.

The vapour implementation showed the best results with the inactivation of all strains at fourteen incubation days (25 °C) after two hours of treatment.

The samples treated by direct contact with the water-ethanol mixture showed consistent results within the two batches, with and without mechanical removal.

The mechanical removal of spores, by swiping the microfiber cloth on the sample surface, did not influence fungal growth in this experiment. Indeed, the results from this batch of samples are similar to the batch without cloth swiping. The spores’ removal was partial, and the remaining spores resumed growth as the water-ethanol contact did not inactivate them; however, another study has shown that the mechanical removal of fungal spores, by reducing the number of spores on the surface, reduces the overall fungal activity on heritage objects (Prevet 2016).

For vapour implementation, the experiments that were negative after one week of incubation were re-incubated at the same conditions for another week. They remained negative, thus suggesting that, in these conditions, all the mycelium and all the conidia were inactivated. A diameter of the colony similar or larger than the control did not mean that no fungal fragments of the mycelium or conidia were inactivated. Parts of the mycelium and a fraction of the conidia were inactivated, but not enough to prevent growth and germination in many parts of the print. For more drastic treatments, more sections of the mycelium and a more important fraction of the conidia were inactivated. Therefore, it was hypothesized that viable cells were not present in all places of the print. Accordingly, a delay was observed for the growth outside the print, and eventually the diameter of the colony was less than the control. The observation of colonies not growing all around the print but appearing at first only on one edge of the print strengthened this hypothesis.

5 Conclusion

The present work was undertaken to clarify which implementation method of a water-ethanol (30:70 v/v) mixture inactivates fungal growth on silver gelatin prints.

The efficiency of the fungal growth inactivation depends on the temperature and on the time of contact between the water-ethanol mixture and the fungus. In a heritage context, working at high temperature (over 20 °C) is not possible because it would cause damage to the photograph’s constituents. Consequently, contact time is the relevant parameter. Our results show that the longer times tested with vapour implementation successfully inactivated fungal growth. The four tested strains were inactivated after only two hours of exposure to water-ethanol vapours; however, the direct contact tests did not inactivate fungi as the contact times, of between 30 seconds and 8 minutes, were too short.

The vapour treatment shows promising use in heritage conservation as it could be used to treat storage spaces or larger volumes of photographic prints because ethanol vapour can reach any remote place. The lower flammability limit for ethanol is 3.3 kPa (Anonymous 2003) and it can be obtained at 25 °C with an ethanol-water mixture close to 70:30 (v/v). For safety reasons, it is suggested to use an ethanol-water mixture close to 40:60 (v/v) but to extend the ethanol vapour application from 2 to 24 h (Dao et al. 2010).

In conclusion, before being used on photographs this treatment’s long term effects on silver gelatin prints and other photographic techniques must be evaluated further. Some studies have already been performed regarding this matter. Firstly, the water-ethanol mixture was shown not to damage the paper (Sequeira et al. 2016; Weiß 2006); however, butanol vapours lead to a slight modification in photographic gelatin structure resulting in a decrease in viscosity (Tomsŏvá et al. 2016). Complementary tests on the long-term effect of a water-ethanol (30:70 v/v) mixture on photographic materials should be performed.

About the authors

Chloé Lucas is a photograph conservator based in Ottawa, Canada. She graduated in history of art from the Sorbonne University in 2012. It was followed by a five year degree in photograph conservation at the Institut National du Patrimoine, from which she graduated in 2016.Institut national du patrimoine, 124 rue Henri Barbusse, 93 300 Aubervilliers, France

Frank Déniel has been a mycology engineer in service for provision of agro-food and cosmetic industries at EQUASA of University of Brest for the past fifteen years. He has developed an expertise in fungi identification in the laboratory based of molecular, microscopic, classic method, and on control of those microorganisms in different kind of environmental, agricultural, food sector.Étude en Qualité et Sécurité des Aliments (EQuASA), Centre de Ressources EQuASA ESIAB, Technopôle Brest Iroise, 29 280 Plouzané, France.

Dr. Philippe Dantigny is an engineer in Food Processing and Master Degree in Food Microbiology (1985). He got his PhD in 1989 in Biochemical Engineering at the National Polytechnics of Lorraine, Nancy, France. After post-doctoral work, he was appointed as a lecturer in biochemical engineer at the University of Bath, UK. Since 1991, he is a senior lecturer at the University of Lyon, France in food microbiology, and biotechnology. He is the head of the Predictive Mycology group at the LUBEM. He has been member of the French Food Safety Authority for eight years– Biohazard group, expert in Predictive modelling/Food spoilage/Mycotoxins contamination/Fermentations. Dr. Philippe Dantigny has coordinated 1 FP6 project and participated in another EU project. The group of Dr Philippe Dantigny has developed specific modelling tools for fungi, and more generally a new topic named “Predictive Mycology” which aims at understanding and modelling germination, growth and production of mycotoxins in food and agricultural products.Laboratoire Universitaire de Biologie et d’Écologie Microbienne (LUBEM), Avenue du Technopole, 29 280 Plouzané, France.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Christelle Donot, from EQUASA for her help in the implementation of this study.

References

Abrusci, C., Marquina, D., Del Amo, A., Catalina, F.: A viscometric study of the biodegradation of photographic gelatin by fungi isolated from cinematographic films. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 58 (2006): 142–149.10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.06.011Suche in Google Scholar

Abrusci, C., Marquina, D., Del Amo, A., Catalina, F.: Biodegradation of cinematographic gelatin emulsion by bacteria and filamentous fungi using indirect impedance technique. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 60 (2007): 137–143.10.1016/j.ibiod.2007.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

Abrusci, C., Martín-Gonzáles, A., Del Amo, A., Catalina, F., Collado, J., Platas, G.: Isolation and identification of bacteria and fungi from cinematographic film. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 56 (2005): 58–68.10.1016/j.ibiod.2005.05.004Suche in Google Scholar

Adamo, M., Cesareo, U., Francesco, M., Matè, D.: Gamma radiation treatment for the recovery of photographic materials: Results achieved and prospects. Kermes 86 (2012): 43–53.Suche in Google Scholar

Anonymous: NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards, Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

Bacílková, B.: Study of the effect of butanol vapours and other alcohols on fungi. Restaurator 27 (2006): 186–199.10.1515/REST.2006.186Suche in Google Scholar

Bingley, G., Verran, J.: Counts of fungal spores released during inspection of moldy cinematographic film and determination of the gelatinolytic activity of predominant isolates. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 84 (2013): 381–387.10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.04.006Suche in Google Scholar

Butterfield, F. J.: The potential long-term effects of gamma irradiation on paper. Studies in Conservation 32 (1987): 181–191.10.1179/sic.1987.32.4.181Suche in Google Scholar

Dao, T., Dejardin, J., Benoussan, M., Dantigny, P.: Use of the Weibull model to describe inactivation of harvested conidia of different Penicillium species by ethanol vapours. Journal of Applied Microbiology 109 (2010): 408–414.10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04662.xSuche in Google Scholar

Flieder, F., Capderou, C.: Sauvegarde Des Collections Du Patrimoine. La Lutte Contre Les Détériorations Biologiques, Paris: CNRS, 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

Jacek, B.: Erkennen und Behandlung von Mikroorganismen auf Fotografien (Teil 2). Rundbrief Fotografie 11 (2004): 5–11.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakshmikant, K.: Cellulose degradation and cellulase activity of five cellulolytic fungi. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 6 (1990): 64–66.10.1007/BF01225357Suche in Google Scholar

Lech, T.: Evaluation of a parchment document, the 13th century incorporation charter for the city of Krakow, Poland, for microbial hazards. Applied Environmental Microbiology 82 (2016): 2620–2631.10.1128/AEM.03851-15Suche in Google Scholar

Lucas, C.: « L’asphalte même est un miroir » Étude et conservation de sept tirages de la Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. Traitement aux vapeurs d’éthanol des gélatines photographiques altérées par des micro-organismes. Master thesis, Paris: Institut national du patrimoine, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Méheust, D.: Exposition aux moisissures en environnement intérieur: méthodes de mesure et impacts sur la santé. Ph.D. thesis, Rennes: Santé publique et épidémiologie, Université Rennes 1, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Meier, C.: Schimmelpilze auf Papier. Fungizide Wirkung von Isopropanol und Ethanol. Papier Restaurierung 7 (2006): 24–31.10.1080/15632628.2006.12461858Suche in Google Scholar

Nguyen Van Long, N., Dantigny, P.: Fungal contamination in packaged foods. In: Antimicrobial Food Packaging, J. Barrros-Vélàzquez (Ed.), Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2016: 45–63.10.1016/B978-0-12-800723-5.00004-8Suche in Google Scholar

Nittérus, M.: Fungi in Archives and Library: A literary survey. Restaurator 21 (2000a): 25–40.10.1515/REST.2000.25Suche in Google Scholar

Nittérus, M.: Ethanol as a fungal sanitizer in paper conservation. Restaurator 21 (2000b): 101–105.10.1515/REST.2000.101Suche in Google Scholar

Pavon Flores, S. C.: Gamma radiation as fungicide and its effects on paper. The American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works Bulletin 16 (1975): 16–45.10.2307/3179347Suche in Google Scholar

Prevet, M.: Conservation-restauration d’un meuble d’appui du XIXe siècle en marqueterie Boulle conservé au château d’Espeyran (Saint-Gilles, Gard). Analyse historique et technique d’un meuble resté dans son contexte et témoin rare des matériaux de fabrication originaux. Observation in situ de l’évolution du traitement des moisissures et du comportement microbiologique de produits de restauration. Reconstitution de pièces de marqueterie : l’apport des technologies numériques pour la découpe et la gravure. Master thesis, Paris: Institut national du patrimoine, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Sclocchi, M. C., Damiano, E., Matè, D., Colaizzi, P., Pinzari, F.: Fungal biosorption of silver particles on 20th century photographic document. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 84 (2013): 367–371.10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.04.021Suche in Google Scholar

Sequeira, S. O., Phillips, A. J. L., Cabrita, E. J., Macedo, M. F.: Ethanol as an antifungal treatment for paper: Short-term and long-term effects. Studies in Conservation 62 (2016): 33–42.10.1080/00393630.2015.1137428Suche in Google Scholar

Tomsŏvá, K., Ďurovič, M., Drábková, K.: The effect of disinfection methods on the stability of photographic gelatin. Polymer Degradation Stability 129 (2016): 1–6.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.03.034Suche in Google Scholar

Trehorel, M.: Aspects réglementaires concernant l’utilisation de l’oxyde d’éthylène: Incidence sur la conception et la mise en œuvre des équipements de désinfection. In: Patrimoine culturel et altérations biologiques : actes des Journées d’études de la SFIIC., Poitiers, 17 et 18 novembre 1988, Champs-sur-Marnes: Section française de l’International Institute for Conservation, 1989: 55–69.Suche in Google Scholar

Valentin, N.: Biodeterioration of library materials: Disinfection methods and new alternatives. The Paper Conservator 10 (1986): 40–45.10.1080/03094227.1986.9638530Suche in Google Scholar

Weiß, D.: Ethanol und Chlorometakresol als Fungizide. Papier Restaurierung 7 (2006): 32–39.10.1080/15632628.2006.12461859Suche in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Ethanol as an Antifungal Treatment for Silver Gelatin Prints: Implementation Methods Evaluation

- Evaluation of Alkaline Compounds Used for Deacidification and Simultaneous Lining of Extremely Degraded Manuscripts

- Longevity of Optical Disc Media: Accelerated Ageing Predictions and Natural Ageing Data

- Micro-Chemical and Spectroscopic Study of Component Materials in 18th and 19th Century Sacred Books

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Ethanol as an Antifungal Treatment for Silver Gelatin Prints: Implementation Methods Evaluation

- Evaluation of Alkaline Compounds Used for Deacidification and Simultaneous Lining of Extremely Degraded Manuscripts

- Longevity of Optical Disc Media: Accelerated Ageing Predictions and Natural Ageing Data

- Micro-Chemical and Spectroscopic Study of Component Materials in 18th and 19th Century Sacred Books