Abstract

This article introduces Positive Economic Psychology, a novel discipline that integrates Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology. The article elucidates the two parent disciplines, detailing their respective goals, remits, key topics, research methods, and sub-disciplines. The article then delves, with a critical eye, into the historical and intellectual backdrop that catalysed the birth of Positive Economic Psychology. Next, the article describes Positive Economic Psychology, a field situated at the junction of psychological wellbeing, and economic decision-making and behaviour, defining it as a discipline that is concerned with examining and promoting economic wellbeing, focusing on the conditions and processes that can foster economic prosperity and optimal economic functioning in individuals, groups, and institutions. The article draws the contours of the new discipline and outlines its goals and key principles. It also predicts its future trajectory, considering both its potential for profound societal impact and the challenges that it may face.

1 Introduction

This article marks the launch of Positive Economic Psychology as a novel interdisciplinary field that integrates Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology. Topics belonging to this field are presently experiencing a period of growth and discovery and attracting significant interest from the scientific community, practitioners, and the public. The aim of this article is to chart the intellectual terrain of this nascent discipline and the rationale for its emergence.

A scientific discipline is defined as a field of study that systematically explores specific phenomena, grounded in established principles and employing rigorous methodologies. It is distinguished by its unique subject matter, theoretical frameworks, and methodological approaches, often formalised through academic departments, professional associations, and scholarly publications (Kuhn, 1970).

To delineate the contours of the new discipline, the article begins by describing the two fields that form the foundation of Positive Economic Psychology. It then discusses the background that prompted the discipline’s emergence and delves into its mission, remit, and principles. The article concludes with an assessment of its future trajectory and potential challenges.

2 Positive Psychology

2.1 Defining Positive Psychology

Positive Psychology is a branch of Psychology that emerged as an applied scientific field in 1998 (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). While at the outset there were significant misconceptions about its remit and it was dubbed as “happiology,” today it is recognised as “the study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing or optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions” (Gable & Haidt, 2005, p. 104). Hence, the concept of psychological wellbeing is at the centre of its scientific endeavours and applied work.

2.2 The Mission of Positive Psychology

The establishment of Positive Psychology emerged primarily as a counteraction to the emphasis on pathology that prevailed in Applied Psychology throughout the twentieth century. Seligman (1999), the founding leader of Positive Psychology, critiqued the field of Applied Psychology and argued that its focus on psychological distress, disorder, and dysfunction has led to the constriction of Applied Psychology’s scope, effectively positioning it as a remedial field. This partial perspective has left the field ill-equipped to harness and leverage the positive aspects of human nature: “Psychology is not just the study of weakness and damage, it is also the study of strengths and virtues. Treatment is not just fixing what is broken, it is nurturing what is best within ourselves” (Seligman, 1999, p. 2). On the back of this critique, Positive Psychology situated itself as a rebellious movement that challenged the status quo with the aim of providing a more balanced view of human nature, both in research and in its applied practices (Seligman, 2005).

The mission of Positive Psychology was notably far-reaching: “to catalyse a change in the focus of Psychology from preoccupation only with repairing the worst things in life to also building positive qualities” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5). To promote this transformation, several key goals were set (Seligman et al., 2004):

To place high on the scientific agenda, new themes and questions that centre on the healthy facets of human psychology.

To design and empirically test interventions that promote wellbeing.

To formulate a common language that facilitates communication and comprehension of Positive Psychology concepts.

To combine within therapeutic work, positive and negative perspectives and assessments.

2.3 Key Topics in Positive Psychology

Rusk and Waters (2013) conducted a comprehensive mapping exercise of published research, with the aim of identifying the spectrum of research topics that featured within Positive Psychology in its first 15 years of existence. Their exploration revealed 233 distinct concepts, which the authors categorised into 21 overarching themes: life satisfaction, happiness, positive emotions, mood, self-efficacy, motivation, self-regulation, creativity, optimism, resilience, hardiness, mental toughness, posttraumatic growth, behavioural change, relationship, altruism, leadership, citizenship behaviour, education, mindfulness, and gratitude. The topics that received the most research attention were self-efficacy, happiness, optimism, strengths, engagement, and meaning. Notably, among the 233 concepts, 30% are considered novel and were not explored prior to the inauguration of Positive Psychology (examples include character strength, gratitude, and psychological capital). However, 70% of these concepts (e.g. optimism, self-determination, and mindfulness) have been researched before Positive Psychology was established, which elicits questions around ownership. As it stands, the remit of the discipline has been broadly defined, capturing within its scope these established concepts that are considered allied with Positive Psychology, rather than originated by it (Hart, 2020). Moreover, although these topics have been examined prior to the launch of Positive Psychology, some have seen little development over the years. Therefore, one of the primary missions of Positive Psychology was to assemble, recognise, prioritise, build on, develop, and integrate this body of knowledge (Linley & Joseph, 2004).

Since 2013, no updated analysis was published, though an inspection of recently published textbooks in Positive Psychology suggests that this classification of key themes still holds true (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019; Carr, 2022; Compton & Hoffman, 2019; Hart, 2020; Pedrotti et al., 2024; Snyder et al., 2020).

2.4 Research Methods in Positive Psychology

Positive Psychology employs methods rooted in its parent field, Psychology, adapted for its unique focus (Ong & Van Dulmen, 2007). Quantitative methods dominate the field, with tools developed to measure constructs like happiness (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999), wellbeing (Butler & Kern, 2016), and resilience (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Experimental designs mainly assess positive interventions, such as gratitude exercises (Emmons & McCullough, 2003), resilience training (Gillham et al., 2006), and wellbeing therapy (Fava, 2016). Qualitative methods, though less prominent, provide deeper insights through interviews, focus groups, and document analysis, exploring constructs like flow (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 2014) and posttraumatic growth (Hefferon, 2012). Mixed-methods research is used to study complex phenomena, as seen in the Nun’s Study (Danner et al., 2001) and the Yearbook Study (Harker & Keltner, 2001), which provide insights on the merit of positive affectivity. Theoretical research and reviews, such as Fredrickson’s (2001) Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions, and Bolier et al.’s (2013) review of positive interventions, as well as policy papers like Diener’s (2000) proposal for a national happiness index, contribute to developing conceptual frameworks by synthesising existing evidence and identifying areas requiring further investigation. Large-scale surveys like the World Happiness Reports and the British Census which incorporate wellbeing measures, complement academic studies, offering extensive datasets.

However, methodological critiques remain. Over-reliance on self-reports and cross-sectional designs limits causal inference and raises concerns about biases (Coyne & Tennen, 2010). The discipline is also criticised for its focus on individual-level variables (Christopher & Hickinbottom, 2008) and a WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic [Henrich et al., 2010]) population bias (Linley & Joseph, 2004). There is also scarce research in Positive Psychology that incorporates insights from neuroscience or utilises big data. Additionally, it has been linked to Psychology’s wider “replicability crisis” (Pashler & Wagenmakers, 2012), with some pivotal studies failing to yield consistent results in subsequent research (Brown et al., 2017).

2.5 Sub-Domains of Positive Psychology

Since its inception, Positive Psychology has evolved in numerous directions, some of which have solidified into interdisciplinary sub-disciplines. Each of these cultivated a distinctive theoretical viewpoint and application while merging with other scholarly and applied fields. These include two highly established sub-disciplines: Positive Education (Kern & Wehmeyer, 2021) and Positive Work and Organisational Psychology (Linley et al., 2010). It also comprises several burgeoning domains such as Positive Health (Burke et al., 2022), Positive Body (Hefferon, 2013), Positive Ageing (Minichiello & Coulson, 2012), Positive Social Psychology (Lomas, 2015; Roffey, 2011), Positive Neuroscience (Greene & Seligman, 2016), Positive Environment and Architecture (Menezes et al., 2021), and Positive Tourism (Filep et al., 2016). In addition, several applied integrated fields have emerged: Positive Psychology Coaching (Green & Palmer, 2018), Positive Psychotherapy (Rashid & Seligman, 2018), Positive Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Bannink & Geschwind, 2021), and Positive Psychiatry (Bannink & Peeters, 2021; Palmer, 2015). One domain that is conspicuous in its absence is Positive Economic Psychology.

2.6 Limitations and Critique

Beyond the methodological critique mentioned above, Positive Psychology has faced significant criticism, with scholars questioning its philosophical and theoretical foundations, key concepts, and broader implications. van Zyl et al. (2024) conducted a systematic review, identifying 117 specific critiques, which the authors grouped into 21 categories and the following overarching themes:

Lack of theorising and conceptualisation: Positive Psychology is criticised for lacking a unifying theoretical framework and clear philosophical underpinnings. Issues include poorly defined virtues, unclear definitions of “positive,” artificial divisions between “positive” and “negative” experiences, and inconsistencies in constructs like flourishing or wellbeing.

Perception as a pseudoscience: Critics argued that Positive Psychology literature often lacks empirical evidence and relies on unsubstantiated claims. Confirmation bias, circular reasoning, and reliance on “common sense” instead of rigorous scientific methods have been highlighted.

Lack of novelty and isolation from mainstream Psychology: Positive Psychology is seen as repackaging existing ideas from traditional Psychology without meaningful innovation. It is also criticised for isolating itself from the broader discipline and falling into the “jingle-jangle fallacy,” where similar terms are confused or old concepts are rebranded.

Promotion of a neoliberal ideology: The field has been criticised for promoting individualism while neglecting systemic and structural factors. For instance, by interpreting wellbeing through a neoliberal perspective – emphasising individualism and self-reliance, it places the responsibility for wellbeing on the individual, disregarding wider societal and systemic influences such as inequality and resource accessibility.

Overcommercialisation and alignment with capitalism: Positive Psychology has been criticised for prioritising profit-driven interventions over scientifically validated practices. Its focus on commodifying happiness and aligning with consumerist ideologies raises ethical concerns.

Another critique, particularly relevant to this article, is the limited research within Positive Psychology on economic and financial aspects of life beyond the association between money and happiness. This reflects the broader concern about neglect of structural and systemic factors influencing wellbeing. Additionally, there is little integration of economic measures (such as wealth, consumption, Gross Domestic Product [GDP], or economic inequality) in Positive Psychology scholarship, highlighting a significant gap.

Interestingly, most textbooks in Positive Psychology (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019; Carr, 2022; Compton & Hoffman, 2019; Pedrotti et al., 2024; Snyder et al., 2020) acknowledge and address criticism voiced towards the discipline, as well as highlight its contribution to the growth and evolution of the field. Hart (2020) observed that, although it is unsurprising for a discipline that challenges the status quo to face criticism, some of this critique has been misplaced or overstated. However, engaging with valid critique has encouraged reflection and learning, ultimately driving significant advancements in its foundational philosophy, theories, methods, and interventions. Lomas et al. (2021) described three waves of development in Positive Psychology: the first simplified approaches to wellbeing, the second embraced the complexity of positive and negative experiences, and the third broadened the scope to include systems, contexts, and interdisciplinary methodologies. Each wave has emerged in response to previous critiques, leading to a more nuanced and sophisticated field.

3 Economic Psychology

3.1 Defining Economic Psychology

Economic Psychology is a branch of applied psychology and an interdisciplinary field that combines elements from Psychology and Economics. It aims to understand how psychological factors influence economic decisions and behaviours, and conversely, how economic contexts or circumstances impact people’s lives. Ranyard and De Mello Ferreira (2018, p. 4) defined Economic Psychology concisely as “the science of economic mental life and behaviour.” An earlier definition described it as “the study of how individuals affect the economy and how the economy affects individuals” (Lea et al., 1987, p. 2).

3.2 Behavioural Economics

Behavioural Economics is a multidisciplinary field that initially focused on understanding decision-making processes by incorporating psychological insights into economic models (Ranyard & De Mello Ferreira, 2018). Over the years, the scope of Behavioural Economics has expanded to encompass a wide range of domains, such as financial behaviours, market dynamics, and public policy. This broadened focus overlaps with the intellectual terrain of Economic Psychology, raising questions about the association between them (Cartwright, 2011). Kirchler and Hoelzl (2018) clarified that Economic Psychology and Behavioural Economics cover the same intellectual terrain and share similar goals; however, Economic Psychology is rooted in Psychology, while Behavioural Economics emerged from Economics. Hence, the differences between the two schools of thought are philosophical and methodological in essence and mainly pertain to the diverse epistemological assumptions of their parent disciplines, regarding the nature, scope, and origins of knowledge, and the ways in which research is conducted. Nevertheless, today, the two lines of work are showing some levels of convergence, as Cartwright (2011, p. 11) noted: “it seems fair to say that a lot of what has historically been called Behavioural Economics would probably be more appropriately called Economic Psychology.” Hence, in the context of this article, we will refer to Economic Psychology as an interdisciplinary endeavour that encompasses both fields.

3.3 The Goals of Economic Psychology

Economic Psychology emerged in the late nineteenth century, with Tarde’s (1902) seminal works, which highlighted the absence of psychological considerations in Economics. Thus, the primary goal of Economic Psychology is to utilise psychological theories and concepts to explore and explain economic phenomena. Notably, this development occurred shortly after Psychology was formalised as a scientific field in 1879, following the establishment of Wundt’s Introspectionist School in Leipzig (Schultz & Schultz, 2011).

A significant objective of Economic Psychology was to challenge the foundational assumptions of economic theory. Early research in the field often contested the concept of “homo economicus,” which forms the basis of key economic theories. It claims that individuals approach economic decisions and actions in a manner that is rational and consistent, guided by valid information, motivated by self-interest, and strives to maximise the utility of economic activities (Sloman & Garratt, 2010). The term “utility” refers to the satisfaction or benefit that an individual derives from economic decisions or actions (Becker, 1976).

In challenging the concept of homo economicus, Economic Psychology scholars claimed that it presents an unrealistic depiction of economic behaviour. To address this flaw, they called for the integration of concepts and theories, particularly from Cognitive Psychology, in the analysis of economic phenomena to enable a more realistic representation of economic decisions and behaviours and their drivers.

3.4 Challenging Homo Economicus: Seminal Work in Economic Psychology

Below are several examples of the ways in which scholars in Economic Psychology challenged the assumptions that underlie the concept of homo economicus.

In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen (1899) analysed the attitudes and life-style of US millionaires. His findings on conspicuous consumption describe how the leisure class engages in lavish spending to publicly display their social status and wealth, hence suggesting a lack of rationality in their consumer behaviour, as well as highlighting the importance of social factors (particularly social comparison) in driving consumption.

Later on, Katona (1951) created the Index of Consumer Sentiment (ICS), which revealed the extent to which people’s expectations and attitudes towards the economy influence their decisions and behaviours, and the irrationality of spending behaviours.

During the same period, Simon (1960) observed that business executives did not pursue profit maximisation. Instead, they aimed for certain satisfactory performance thresholds, ensuring that their businesses remained viable. He introduced the term “satisficing” to describe these aspiration levels, hence moving away from the focus on utility maximisation. His pivotal work on bounded rationality challenged the notion of rationality in homo economicus (Simon, 1976).

Tversky and Kahneman’s (1974) seminal work on heuristics and biases continued this line of work and contradicted the assumption of rationality in homo economicus, since it revealed that people often rely on mental shortcuts (heuristics) to make economic decisions, which can lead to systematic biases.

Thaler’s (1980) work on economic judgment and decision-making demonstrated that people categorise and treat money differently depending on its source and intended use. This contradicts the homo economicus assumption that individuals make decisions that aim to maximise their wealth.

In another study, Thaler and Shefrin (1981) demonstrated that individuals often have limited self-control, leading to behaviours that may undermine their long-term interests.

Finally, in Nudge Theory, Thaler and Sunstein (2008) suggested that small changes in the way choices are presented to people can significantly influence their behaviours, which challenges the homo economicus assumption that individuals make choices based solely on a rational evaluation of available information.

These examples (and numerous others) demonstrate that much of the early research in Economic Psychology focused on the inept side of economic behaviours, emphasising people’s lack of economic literacy, and limited capacity to process information and make decisions. It also exposed the numerous psychosocial factors that undermine economic thinking and actions, that can lead people to irrational and ineffective economic behaviours. Hence, a key critique that could be voiced towards this impressive volume of work, is that in challenging the key models of Economics, Economic Psychology scholars focused on and mainly examined the negative and deficient aspects of human economic behaviours and experiences, while the positive and capable aspects were mostly ignored (Gigerenzer, 2015, 2018). A review of the key textbooks in Economic Psychology (Kirchler & Hoelzl, 2018; Lewis, 2018; Ranyard, 2018; Van Raaij et al., 2013) indicates a continued emphasis on the maladaptive aspects of economic behaviours, while the adaptive dimensions of human economic behaviour remain underrepresented and insufficiently researched.

3.5 Key Topics in Economic Psychology

Economic Psychology encompasses a broad range of topics, primarily aligning with microeconomics, and less with macroeconomics. An analysis of the key themes that featured in articles published in the Journal of Economic Psychology (considered the main outlet for Economic Psychology scholarship) between 1981 and 2010 (Kirchler & Hoelzl, 2006, 2018) found 16 overarching categories that can be seen as key topics: Theory and history; individual decision making; cooperation and competition; socialisation and lay theories; money, currency and inflation; financial behaviour and investment; consumer attitudes; consumer behaviour; consumer expectations; businesses; marketplace behaviour, marketing and advertising; labour market; tax behaviours; environmental behaviours, government policy, and other topics. The most commonly studied topics were decision making and consumer behaviours. An examination of contemporary textbooks on Economic Psychology (for example Cartwright, 2011; Kirchler & Hoelzl, 2018; Lewis, 2018; Ranyard, 2018) indicates that these categories capture well the current scope of the field.

3.6 Research Methods in Economic Psychology

Economic Psychology uses a broad range of methods drawn from both Psychology and Economics (Antonides, 2018). Quantitative methods are predominant, with tools developed to measure micro-level constructs like financial literacy (CFPB, 2017) and financial behaviours (Dew & Xiao, 2011). Meso-level constructs, such as financial inclusion (Beck & De La Torre, 2007) and corporate size (Connolly et al., 2021), and macro-level indicators, including GDP (Mankiw, 2020) and Human Development Index (HDI) (Baumann, 2021), are often sourced from economic reports. These metrics are used in studies like the Easterlin Paradox (Easterlin, 2004) on economic growth and life satisfaction, and Yu’s (2018) analysis of inequality and mental health. The field therefore frequently leverages large-scale surveys collected by governments and organisations, such as the Global Bank, US Bureau of Labour Statistics, and UK Office of National Statistics, and big data, enabling time-series analyses.

Experimental research is a hallmark of Economic Psychology, particularly in Behavioural Economics research. Laboratory experiments use methods such as the Dictator Game (Engel, 2011) to study fairness and negotiation, and hypothetical scenarios to examine heuristics and biases (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Field experiments test interventions in real-world settings, like Thaler and Sunstein’s (2008) nudging strategies. Randomised controlled trials are employed to assess the impact of interventions, such as financial education programmes, on behaviours (Lusardi et al., 2020). Natural experiments exploit real-world events, for example, examining food consumption shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic (Scarmozzino & Visioli, 2020). Survey experiments embed experimental manipulations into surveys, such as priming participants, as in Vohs et al.’s (2006) money priming and social behaviour study. Behavioural field observations examine natural behaviours, like Anesbury et al.’s (2016) work on shoppers’ online navigation.

Qualitative research is less common, exploring topics like consumer behaviour and materialism (Dittmar & Drury, 2000; Vohra, 2016). Mixed methods, though scarce, combine qualitative and quantitative approaches, as seen in Herrmann et al.’s (2023) exploration of gig workers’ experiences.

Theoretical contributions are abundant, with models describing consumer behaviours, market trends and decision-making processes, such as the Consumer Decision Model (Engel et al., 1968) and Dual Modes of Thinking Theory (Kahneman, 2011). Some theories, such as Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), include mathematical analyses to formalise behavioural insights. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are integral for synthesising research and identifying gaps, as exemplified by Lund et al.’s (2010) review on poverty and mental health, and Kaiser and Menkhoff’s (2020) meta-analysis on financial education. Policy-oriented work, like Thaler and Sunstein’s (2020) nudge policies, further illustrates the field’s application in real-world contexts.

Despite its wide methodological range, Economic Psychology faces significant critiques. Ranyard and De Mello Ferreira (2018) argued that the field lacks a distinct methodological identity, describing it as “eclectic.” This raises concerns about the extent of methodological integration between its two parent disciplines. Additionally, despite addressing similar research domains, the methodological differences between Economic Psychology and Behavioural Economics remain pronounced.

While methods drawn from Psychology face similar critique to other psychological sub-disciplines, the reliance on laboratory experiments has also faced notable criticism. Behaviours observed in low-stakes, controlled environments often fail to translate to real-world contexts, raising concerns that the observed behaviours are merely artefacts of the experimental setting (Pūce, 2019). Additionally, such studies often use students who self-select into these studies, or participants from WEIRD populations (Henrich et al., 2010), raising concerns about their cultural generalisability. Another concern raised is around social desirability bias, where individuals are inclined to present themselves in a favourable light in experimental settings (Zizzo, 2010). Lastly, laboratory research has faced criticism for its lack of a control group, which can lead to misinterpretation or the confounding of observed effects (Wilkinson & Klaes, 2018).

3.7 Sub-Domains of Economic Psychology

Economic Psychology encompasses several sub-disciplines, each focusing on distinct aspects of the interplay between psychological processes and economic behaviour. The two primary sub-disciplines of Economic Psychology are Consumer Psychology and Financial Psychology:

Consumer Psychology investigates the psychological processes underlying consumer behaviour, aiming to understand the motivations and impacts of individuals’ and groups’ consumption activities. A significant part of the discipline focuses on cognitive processes and behaviours involved in purchasing and using products and services. Research in Consumer Psychology covers different aspects of the consumption cycle, from identifying needs and seeking information to evaluating post-purchase experiences. The field integrates theories and concepts from various disciplines including Psychology, Marketing, Advertising, Sociology, and Anthropology, focusing on areas such as motivations, decision-making, perception and attention, information processing, attitudes, and the influence of advertising (Jansson-Boyd, 2019).

Financial Psychology is the study and application of psychological theories, methods, and practices in the areas of personal finance and financial services. Its key aim is to promote sound financial decisions and behaviours. A significant aspect of Financial Psychology is its applied side, which informs the Financial Planning industry. It includes mainly financial and some psychological interventions that are tailored for client interactions, providing financial planners with essential skills and tools to assist their clients in achieving their financial goals (Klontz et al., 2023). Additionally, it encompasses the field of Behavioural Finance, which employs Cognitive Psychology theories and models to investigate financial behaviours (Pompian, 2012). It is worth noting that it is considered a relatively narrow sub-field within Economic Psychology due to its focus on micro-level work around personal finance, while Economic Psychology encompasses micro-, meso- and macro-level work. It primarily consists of applied work and surveys, many of which are conducted by the financial industry, and, at present, it incorporates only limited insights from Positive Psychology.

As can be seen from these descriptions, there has not been an attempt to marry Positive Psychology more broadly with its parent discipline, Economic Psychology.

3.8 Limitations and Critique

Similar to Positive Psychology, Economic Psychology has encountered considerable controversy and debate over the years. However, these disputes tend to focus more on specific models, empirical findings, or particular methodologies (see, e.g. Cartwright, 2011) rather than on broader issues such as its philosophical underpinnings, range of research methods, aims, agenda, scope, or wider impact. Compared to Positive Psychology, there is also less recognition of such broader critiques in its leading textbooks (see, e.g. Antonides, 2012; Kirchler & Hoelzl, 2018; Ranyard, 2018; Van Raaij et al., 2013). Key critique of Economic Psychology beyond the methodological critique mentioned earlier refers to the following points:

Lack of overarching theory: A central critique of Economic Psychology is its lack of foundational theory (Fudenberg, 2006). Unlike traditional economics, which is grounded in a cohesive framework of rationality and optimisation, Economic Psychology focuses on deviations from these principles without a unified structure to integrate its findings. This theoretical gap hinders generalisation and makes the field less systematic and harder to apply across diverse contexts.

Lack of novelty: Economic Psychology has faced criticism for offering little innovation in its models, often repackaging concepts already established in economic literature (McChesney, 2013). Examples include Bounded Rationality (Simon, 1960), the costliness of information (Stigler, 1961), and the acknowledgment of irrational consumer preferences (Galbraith, 1938), all of which predate the field’s emergence.

Focus on deficits: Gigerenzer (2015, 2018) has been a prominent critic of Economic Psychology’s assumptions about human behaviour, which often depict humans as inherently irrational, prone to cognitive biases, and easily influenced. This perspective suggests that biases are not merely occasional errors but deeply ingrained tendencies comparable to hard-wired visual illusions, causing most individuals to err in predictable ways. Thaler (1991) described mental illusions as “the rule rather than the exception” (p. 4), while Tversky and Kahneman (1983) referred to biases as showing “stubborn persistence” (p. 300). Kahneman (2011) further argued that these cognitive limitations are “not readily educable” (p. 417), implying marginal potential for effective de-biasing.

Bias bias: In conjunction with its focus on deficiencies, Gigerenzer (2018) described Economic Psychology’s focus on human irrationality as “bias bias,” suggesting the field may exhibit confirmation bias in its own research. Studies often prioritise highlighting irrational behaviours, overlooking instances of rational or adaptive decision-making. This narrow focus reinforces the narrative of human irrationality and aligns with the field’s core agenda of identifying deviations from rational behaviour, which underpins its identity and purpose.

Paternalistic perspective: Economic Psychology often adopts a libertarian paternalistic approach, using nudges – subtle changes in choice architecture – to influence behaviours deemed beneficial, such as healthier eating or increased savings (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). While effective in achieving short-term outcomes, nudges typically exploit cognitive biases rather than fostering the skills needed for autonomous decision-making, risking dependency on external interventions. Critics argue that this approach reflects paternalistic values, steering individuals towards decisions aligned with policymakers’ judgments of what constitutes a “better” outcome, which may conflict with personal values or priorities (Hertwig & Grüne-Yanoff, 2017). This raises ethical concerns about autonomy, underscoring the need to balance behavioural guidance with respect for individual choice.

Usefulness of heuristics: Gigerenzer (2008) argued that heuristics, often labelled as irrational, can be as effective as analytical methods by balancing effort and accuracy. These cognitive shortcuts simplify decision-making, therefore conserving mental resources by relying on fast, intuitive processes, even if they sometimes sacrifice precision.

Inability to demonstrate causality: Economic Psychology has documented numerous deviations from normative rationality but provides limited evidence that these lead to tangible losses, such as reduced earnings, diminished happiness, poor health, or shorter lifespans (Arkes et al., 2016; Gigerenzer, 2018).

Misleading analogies: Economic Psychology often compares cognitive biases to visual illusions, suggesting they are similarly fixed and inevitable. However, this analogy is misleading. Visual illusions reflect intelligent brain processes, not irrationality, as they transform two-dimensional input into a coherent three-dimensional perception. Furthermore, equating biases with hardwired, unchangeable traits ignores humans’ capacity to learn, adapt, and improve decision-making. Gigerenzer (2018) argued that this perspective fosters a defeatist narrative, overlooking evidence of cognitive adaptability.

Contradictory models: Economic Psychology includes diverse observations, some of which conflict when explaining the same phenomena, with little clarity on when each model applies. For example, it remains unclear whether individuals are more influenced by initial information (priming or anchoring effects) or by the most recent information (recency effect) (Fudenberg, 2006).

Another critique, particularly pertinent to this article, is the scarcity of research within Economic Psychology that explores positive and adaptive aspects of economic and financial life beyond the established connection between money and happiness. For instance, there is limited investigation into the nature of adaptive financial decision-making or the internal factors – such as self-esteem, values, motivation, goals, or mindfulness – that may contribute to such decision-making. This gap highlights a significant area of research that remains underexplored and reflects the broader concern noted above about the field’s predominant focus on deficits.

4 Positive Economic Psychology

4.1 Defining Positive Economic Psychology

Positive Economic Psychology is primarily concerned with researching and enhancing financial and economic wellbeing. It explores the conditions and processes that can foster economic prosperity and optimal economic functioning of individuals, groups, and institutions. Thus, the concepts of financial and economic wellbeing are fundamental to its research and applications.

We note that while the terms financial wellbeing and economic wellbeing are often used interchangeably in the literature (Mahendru et al., 2022; Riitsalu et al., 2023), we consider financial wellbeing as an individual and household-level construct, while economic wellbeing is applied here to refer to larger entities – organisations, communities, and nations.

4.2 The Emergence of Positive Economic Psychology

Interdisciplinary sub-disciplines emerge through diverse pathways, reflecting the cumulative nature of scientific inquiry and the fluidity of disciplinary boundaries (Stichweh, 1992). Some arise in niches within established disciplines or at their boundaries, where the integration can address novel research questions. Sub-domains may also form as a result of schisms within a discipline, with disagreements over key theories or methodologies leading to new cognitive identities and research directions. External drivers, such as societal challenges, technological advancements, or changing global conditions, often catalyse the formation of novel fields of inquiry. The introduction of new techniques and tools can also redefine research possibilities, necessitating specialised sub-disciplines to explore their applications. Additionally, interactions between scholars from different fields can spark innovations, enabling disciplines to incorporate diverse perspectives and evolve.

For a sub-discipline to gain recognition, it typically requires a defined field of study, shared terminology and concepts, institutional representation in research and teaching, and organised scholarly communities.

The inception of Positive Economic Psychology as a distinct domain within Economic Psychology arose in response to the field’s historical focus on economic challenges and deficits. A review of the seminal book titles that charted the field’s evolution, such as Heuristics and Biases (Gilovich et al., 2002), Predictably Irrational (Ariely, 2008), Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes and How to Correct Them (Belsky & Gilovich, 2010), Misbehaving (Thaler, 2015), Noise (Kahneman et al., 2021), and Nudge (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008), reveals a subtle but persistent perception among scholars that people “are not wired to make good decisions with money” (Klontz et al., 2023, p. 16), and that these inadequacies in economic decisions and behaviours are mostly innate, and due to cognitive and psychosocial limitations.

Mirroring the evolution of Positive Psychology (as advocated by Seligman, 1999), Positive Economic Psychology aims to broaden the limited scope of Economic Psychology, which predominantly concentrates on financial and economic inability and dysfunction. Our main critique is that Economic Psychology has not given sufficient attention to the adaptive aspects of economic actions and decision-making processes. This limited scope has resulted in a significant gap in the field: There is a dearth of scholarly research exploring adaptive economic behaviours, research-based strategies for building wealth, and methods for addressing the innate shortcomings identified by researchers in Economic Psychology. This gap has been predominantly bridged by the self-help industry, which often offers suggestions and interventions without the backing of robust empirical evidence.

This critique therefore sees the establishment of Positive Economic Psychology as a counter-movement within Economic Psychology, aiming to provide a more comprehensive and balanced understanding of economic thinking and behaviour, by incorporating both positive and negative dimensions. It seeks to rebalance the field, emphasising research and applied practices that not only address economic problems and inadequacies, but also seeks evidence-based means to foster economic wellbeing and prosperity.

The emergence of Positive Economic Psychology as a novel discipline was also influenced by the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic, a period marked by substantial economic fluctuations, impacting individuals, organisations, and communities (Fernandes, 2020). Studies within Economics and Economic Psychology have underlined the financial fragility of households and businesses during this period, many of which were dependent on governmental aid for survival (Coibion et al., 2020). This body of research revealed that numerous households were struggling with altered work conditions, uncertain incomes, and rising costs, leading many to bankruptcy and revealing their inability to withstand financial crises (Baker et al., 2020). The economic devastation precipitated by the pandemic affected a broad spectrum of the population, including middle-class households and small businesses, and not just those traditionally considered at risk. Economists have raised concerns about the long-term scarring effects this crisis might leave on the economy (Kozlowski et al., 2020). Given the prolonged and widespread financial instability caused by the pandemic, a positive, edifying, and empowering approach to economic wellbeing has become relevant, timely, and essential. Positive Economic Psychology aims to equip individuals and organisations with psychological and economic tools that are evidence-based, to enhance financial wellbeing, resilience, and security amidst ongoing economic challenges.

4.3 The Mission of Positive Economic Psychology

The mission of Positive Economic Psychology is ambitiously comprehensive: to instigate a shift in Economic Psychology from its current focus on the adverse and dysfunctional aspects of economic mental life to study and promote positive economic functioning and prosperity. To facilitate this shift, several essential objectives are proposed:

To place new themes and questions on the scientific agenda, that concentrate on the positive and accomplished aspects of economic behaviour and decision-making.

To develop and empirically evaluate micro-level strategies and interventions aimed at promoting financial wellbeing.

To create and implement meso- and macro-level policies that promote effective and adaptive economic behaviours and enhance financial and economic wellbeing in individuals, households, and organisations.

To assess, address, and reduce economic hardship and disparities in economic opportunities and outcomes across different groups.

To establish a unified language that aids in the communication and understanding of concepts within Positive Economic Psychology.

To integrate both positive and negative perspectives and assessments within the framework of economic counselling and financial planning.

4.4 The Principles of Positive Economic Psychology

One of the challenges that novel integrated disciplines often encounter at the outset is the attempt to define their scope and draw the discipline’s boundaries. On the back of its mission to balance the field of Economic Psychology, yet at the same time avoid the drawbacks of Economic theories, it is important to demarcate the remit of Positive Economic Psychology, and clarify its key principles and features. Below is an initial attempt to depict the key facets of Positive Economic Psychology, which can be used as grounds for further discussion and debate:

Positive assumptions about human nature in economic contexts: Research and applied work in social sciences often rests on underlying assumptions about human nature, which carry implicit value judgments. Traditional and neoclassic Economics has been shaped by the concept of Homo Economicus that portrays people as rational economic actors, primarily driven by self-interest and the maximisation of personal gain. Economic Psychology initially sought to challenge these crude assumptions by unravelling the complexity of human economic thinking and behaviours (Kahneman, 2011). However, as noted, an examination of its agenda and key topics reveals a subtle, pervasive and unacknowledged negative assumptions about human nature. These assumptions portray people’s inherent economic deficiencies, ignorance, and incompetence, which results in economic dysfunction and meagre economic outcomes. In contrast to both disciplines, and akin to Positive Psychology (Seligman, 2005), Positive Economic Psychology is rooted in Aristotelian and Humanistic schools of thought (Robbins, 2008) that views individuals as inherently capable of sound and ethical economic decisions and behaviours, and motivated by a natural inclination towards economic growth, prosperity, and responsible economic decision-making. It therefore posits that people can overcome, with some conscious and intentional effort, the innate cognitive and psychosocial economic flaws identified by Economic Psychology scholars. This perspective also suggests that individuals are not only motivated by personal financial interests, but also have an intrinsic prosocial drive towards contributing to the economic welfare of their households, communities and society at large.

Constructive terminology: Reflecting its assumptions about human nature, the language of Economic Psychology often includes terms that imply economic incompetence or hindrances, such as biases, ignorance, limitation, denial, dependence, distortions, noise, conflict, crisis, irrationality, incongruence, laziness, loss, error, fraud, abuse, and financial disorders (see for example Kahneman, 2011; Kirchler & Hoelzl, 2018; Klontz et al., 2023; Thaler, 2015). To foster a more balanced discourse, Positive Economic Psychology scholars and practitioners strive to formulate an alternative vocabulary. In constructing novel terminology, it will likely draw inspiration from Positive Psychology and its journey to make its lexis mainstream (Maddux, 2005). This new lexicon aims to facilitate the articulation, examination and discussion of the positive aspects of human economic psychology. Within this framework, cognitive limitations and ineffective patterns of economic behaviours are construed as common life challenges that can be addressed and surmounted, rather than inescapable hurdles that inevitably lead to economic mistakes or failures.

Positive aim: In alignment with Positive Psychology (Pawelski, 2016), the core aim of Positive Economic Psychology is to explore and understand the positive, adaptive, effective and fulfilling aspects of economic behaviours and decision-making.

Positive agenda: Taking cues from Positive Psychology (Pawelski, 2016), this point refers to the central concepts or topics that are considered integral to the field, such as financial wellbeing, satisfaction, abundance, literacy, capacity, financial skills, resilience, optimism, planning, grit, self-regulation, economic intelligence, and financial wisdom.

Positive processes: This point pertains to the mechanisms or processes that Positive Economic Psychology seeks to operate (often integrated within its interventions). In alignment with Positive Psychology (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), these processes are geared to employ or cultivate capacities that can help individuals and groups attain their desired economic goals and experience growth and abundance. Examples include attaining knowledge, experience or literacy, practicing self-control, self-awareness or mindfulness, and challenging money beliefs and biases.

Focus on applications: Positive Economic Psychology aims to research and develop interventions that promote productive and effective economic outcomes, such as financial wellbeing, prosperity, and resilience. Hence, analogous to Positive Psychology (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013) it seeks to employ an evidence-based perspective for cultivating an abundant life.

Non-clinical target population: This aspect refers to the primary target population that Positive Economic Psychology aims to serve, which predominantly consists of individuals considered non-clinical. This target population is considered similar to that of Positive Psychology (Pawelski, 2016).

Non-directive position: As a scientific field, Positive Economic Psychology takes a non-directive and non-paternalistic stance and refrains from dictating how individuals should live their economic lives. In alignment with its Humanistic stance, it holds a self-determined approach that aims to empower people to exercise their agency and provides resources and strategies that support individuals in achieving their own economic objectives. In contrast, Economic Psychology scholars hold a “libertarian paternalistic” standpoint (Thaler & Sunstein 2008), which aims to “nudge” people towards particular decisions or actions, therefore taking a subtle, but nonetheless somewhat paternalistic and directive approach.

4.5 Current Developments

Several existing research areas have merged concepts from Economic Psychology and Positive Psychology, and hence they fall within the remit of Positive Economic Psychology.

Happiness Economics: The most notable example includes the vast research into the economics of happiness (Frey, 2018; Easterlin, 2015), which focuses on the association between economic factors (particularly money in its varied forms) and happiness (and associated concepts). In much of the recent work, happiness is defined and measured in accordance with Positive Psychology conventions as “subjective wellbeing” (Tay et al., 2018). Agrawal et al. (2023) noted that integrating happiness into economic metrics initially took economists by surprise. Over time, however, this approach has become a standard practice for assessing the value of public goods, highlighting the influence of Positive Psychology on public policy (Diener, 2000), and the fruitful interdisciplinary collaboration between Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology scholars (Kahneman et al., 1999). Key findings (reviewed by Fisher & Frechette, 2023) indicate that the association between money and happiness is weak to moderate and varies depending on whether one resides in a country with a strong or weak economy. Another repeated stipulation is that the impact of money on happiness is more strongly felt under conditions of privation, while among those with robust financial resources there is a “satiation point” beyond which additional financial resources do not enhance happiness. Furthermore, how individuals spend their money impacts their happiness more than income, and relative income or wealth (compared to one’s reference group) are more important for one’s happiness than objective financial resources. Lastly, the concept of hedonic adaptation suggests that boosts in happiness derived from positive changes (such as a salary increase), are often temporary, and over time, individuals tend to adjust to their new material circumstances, diminishing the initial uplift.

Notably, researchers have identified inconsistent findings within this body of work, largely attributed to methodological challenges, such as variations in how happiness is measured and the diverse approaches used to assess financial resources (Lomas, 2024). These issues highlight opportunities for future research.

Optimism: Kahneman and Tversky’s (1996) influential research on heuristics and biases highlights a prevalent tendency for over-optimistic forecasts, especially in economic decision-making and organisational planning by managers, entrepreneurs, and investors. Lovallo and Kahneman (2003) identified “delusional optimism” as a cognitive bias that underpins the “planning fallacy,” where individuals underestimate required resources while overestimating potential outcomes or revenues. Such optimism, as documented by Kahneman and Tversky (1996), can result in severe consequences, including revenue loss, damaged reputations, job cuts, bankruptcies, and market collapses. Nonetheless, in later work, Kahneman (2011) drew on an extensive body of research conducted by Positive Psychology scholars on the benefits of optimism and claimed that “when action is needed, optimism, even if the mildly delusional variety, may be a good thing” (Kahneman, 2011, p. 256). Key research evidence drawn from this body of research demonstrate strong links between optimism and various health outcomes. Compared to pessimists, optimists are generally healthier, report fewer physical complaints, recover faster from illness or injury, adapt better to chronic conditions, experience fewer relapses, and have higher survival rates for life-threatening illnesses (Scheier & Carver, 2018). These health advantages are attributed to optimists’ healthier lifestyles, proactive coping strategies, and greater social support. Additionally, optimism predicts better psychological wellbeing, reduced depression and stress, and enhanced performance in areas such as education, work, and finance. Optimists also exhibit higher resilience, confidence, and adaptive coping, using problem-focused and proactive strategies while avoiding maladaptive behaviours like denial or avoidance. Socially, optimists maintain larger, more satisfying social networks, manage conflicts constructively, and receive greater support during challenging times, further contributing to their wellbeing and success (Carver & Scheier, 2014; Forgeard & Seligman, 2012).

The contrasting findings between Lovallo and Kahneman’s (2003) research and the evidence cited here highlight the need for further studies to better distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive levels of optimism.

Financial wellbeing: An additional example of a relatively nascent concept that falls within the remit of Positive Economic Psychology is financial wellbeing. The CFPB (2017, p. 6) defined financial wellbeing as “a state of being wherein a person can fully meet current and ongoing financial obligations, can feel secure in their financial future, and is able to make choices that allow them to enjoy life.” However, the concept lacks a universally agreed-upon definition. García-Mata and Zerón-Félix (2022) identified 18 competing definitions, and Riitsalu et al. (2023) emphasised the absence of consensus. Among these, only one definition (Salignac et al., 2020) explicitly integrates insights from Positive Psychology, distinguishing between hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of wellbeing. Salignac et al. (2020) defined financial wellbeing as “how happy people are with their current financial situation, and their ability to function economically” (p. 1583). This lack of agreement is reflected in the diversity of measures used to assess financial wellbeing which include both objective and subjective dimensions and intersecting constructs such as financial stress, vulnerability, and resilience. However, no measure currently adopts Positive Psychology’s approaches to wellbeing measurement.

Despite methodological challenges, empirical research on financial wellbeing has grown significantly in the past years, primarily focusing on its predictors rather than its outcomes. Current findings indicate that financial wellbeing is determined by a combination of factors, with prudent financial behaviours playing a central role (Mahendru et al., 2022). These behaviours, in turn, are influenced by personality traits, financial skills and literacy, objective and subjective economic conditions, and the socio-economic and political environment.

Boosting strategies: Another approach that aligns with Positive Psychology’s Humanistic perspectives is Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff’s (2021) boosting strategies. This approach aims to enhance individuals’ capacities to make their own decisions and choices. Unlike nudging strategies, which aim to guide choices by modifying the decision-making environment, boosting strategies focus on empowering individuals to exercise their own agency. These strategies involve education (and at times psychoeducation) and varied forms of guidance and consultancy which provide tools and techniques that help individuals improve their competence and self-sufficiency in economic contexts. The research around these interventions, although scarce, shows promising results. Hertwig & Grüne-Yanoff (2017) highlighted examples where boosts, such as teaching individuals to understand health risks, improved health decision-making. Similarly, Gerber et al. (2018) found that teaching digital privacy skills improved participants’ ability to recognise and mitigate cybersecurity risks, while Gigerenzer et al. (2007) demonstrated that teaching individuals how to interpret probabilities and risks using visual aids significantly improved their understanding of statistical data.

Financial literacy: In line with boosting strategies and holding similar Humanistic perspectives, there has been a surge of literature in the past decades on financial literacy and the provision of financial education as the main means to boost financial literacy (Kaiser & Lusardi, 2024; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014). It is worth noting that the results of these financial education interventions are inconsistent, with some educational interventions showing meagre effects on financial behaviours (Fernandes et al., 2014; Kaiser et al. 2022; Kaiser & Menkhoff, 2017). However recent work that draws on the principles of Positive Psychology have demonstrated that introducing a self-determined approach, raising self-awareness, weaving into interventions psychoeducational contents, using motivational techniques, and taking into account clients’ readiness to change, seems to enhance the interventions’ impact (see reviews by Kaiser & Lusardi, 2024; Peeters et al., 2016).

Applications of positive interventions: Klontz et al. (2023) advocated the use of several Positive Psychology evidence based interventions (such as optimism and gratitude) in the context of financial planning. However, the authors did not provide evidence of successful implementation of these interventions in the financial domain. The only study that implemented a multi-component positive intervention (entailing expressive writing around money, financial gratitude exercise, meditation around money attitudes, charitable giving, and reflective exercise around one’s future relationship with money) aimed to increase life satisfaction, self-efficacy, saving behaviours, reduce financial anxiety, and alter unhelpful money beliefs (Surana, 2019). The study reported significant improvements in most of these outcome measures. The limited application of positive interventions in the financial domain highlights a significant gap in the literature that Positive Economic Psychology research can further address and develop.

These examples (and several others) suggest that the integration of concepts from Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology is already taking place. Hence, a key undertaking of Positive Economic Psychology with regards to these established topics, will be to compile and recognise them, place them higher on the research agenda, advance their development by incorporating theoretical, empirical, and methodological insights from Positive Psychology, integrate these topics into a coherent body of knowledge, and offer them a conceptual home.

4.6 Key Topics

There are numerous topics that Positive Economic Psychology as an emerging field can investigate and develop, and similar to Positive Psychology, it can be expected that upon maturation, the discipline will encompass both established and novel topics. A crucial point to consider is that novel sub-disciplines are often expected to focus solely on unexplored topics. However, within Psychology, this is seldom the case. New sub-disciplines typically build upon, critique, and further refine existing research, providing a stronger conceptual foundation alongside introducing new topics. Additionally, at the inception of a new sub-discipline, interdisciplinary collaboration is usually limited. It is only through such collaboration that truly novel concepts are likely to emerge.

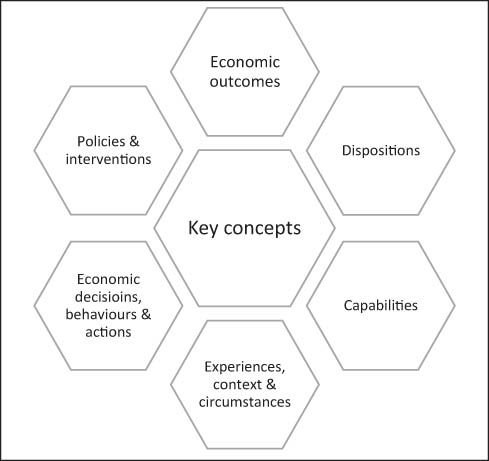

Figure 1 and the descriptions below offer a starting point for considering the remit and potential of Positive Economic Psychology:

Key concepts: The key concepts of this emerging field are financial and economic wellbeing. Consequently, a primary focus of the discipline involves exploring and refining these concepts - their definitions, components and measures. It also aims to examine related concepts such as financial satisfaction, stress, resilience and fragility. The aim is to create interdisciplinary frameworks for these concepts, design compatible measurement tools, and resolve some of the ambiguities and gaps in the existing literature.

Dispositions: These are traits, states, skills and attitudes that impinge on financial behaviours and outcomes. Taking a positive perspective, Positive Economic Psychology can explore various dispositions and their association with financial wellbeing and behaviours, examining concepts that are currently underexplored such as hope, emotional intelligence, grit, values, morality, prosociality, mindfulness, creativity, adaptability and self-awareness.

Capabilities: Navigating the economic landscape effectively requires a combination of cognitive, emotional, and social skills, such as financial literacy, information processing, critical thinking, personal financial management, budgeting, investing, making choices and decisions, negotiating, and time management. These abilities enable individuals to make informed financial decisions, plan for the future, and respond adaptively to economic challenges. Taking a positive perspective, the new discipline will endeavour to examine the nature of these skills and develop appropriate measures, explore how individuals acquire and apply them, and investigate their impact on financial outcomes and wellbeing. These areas represent notable gaps in the existing literature. For example, there is scarce exploratory research that unpacks key financial skills or examines what personal financial management, financial needs, goals or decisions entail, making it challenging to conduct research on their associations with financial outcomes or develop interventions to enhance these capabilities.

Experiences, circumstances and contexts: Life experiences, circumstances, and contextual factors play a significant role in shaping financial behaviours and outcomes. Examples of topics that could be explored within this theme include demographic factors, economic environment and events, country and culture, early life experiences, socio-economic status, financial socialisation, social networks and technology and access to resources. Although some literature examines demographic factors and their influence on financial outcomes, there is limited research on positive contextual factors that can empower individuals, strengthen their financial skills, and foster sensible and responsible financial behaviours.

Decisions, behaviours and actions: In emphasising the positive aspects of human financial behaviours, Positive Economic Psychology aims to promote adaptive and productive decisions and individual behaviours and responsible organisational actions. Examples of topic that could be explored in this category include work patterns, earning, saving, investing, consumption and spending, debt management, tax and insurance behaviours, philanthropy and prosocial spending, life-style choices, economic decisions, entrepreneurship, and ownership. Currently, for some of these concepts (e.g. earning pathways, financial decisions, or life-style choices), there are no validated scales, resulting in scarce research that can differentiate between adaptive and maladaptive behaviours or conditions. Therefore, the new discipline seeks to develop new measures and rebalance the field by exploring the prudent and effective dimensions of these behaviours.

Policies and interventions: Policies and interventions aimed at fostering adaptive and effective financial decisions are crucial in the field of Positive Economic Psychology. Examples of such policies and interventions include financial education programmes, access to financial advice, financial policies that facilitate and promote adaptive behaviours, psychosocial interventions, technology based tools and applications, policy advocacy, individual and community financial empowerment programmes, and financial goal-setting and planning. Currently there is some research on nudging policies, financial education initiatives, financial planning and boosting strategies, but there are few Positive Psychology interventions that have been adapted for the financial domain and tested for their efficacy – a notable gap that Positive Economic Psychology aims to focus on.

Outcomes: Positive Economic Psychology centres on financial and economic wellbeing as core concepts and outcomes, while also examining a variety of other financial and psychological dimensions, such as financial satisfaction, independence, resilience, security, wealth accumulation, productivity, sustainable consumption, and social contribution. Notably, there is a surprising lack of research identifying the factors that drive these positive outcomes – a gap that Positive Economic Psychology seeks to address.

Classification of key topics in Positive Economic Psychology.

The framework depicts the remit and scope of Positive Economic Psychology, highlighting topics and themes that are situated at the junction where positive psychological concepts and economic factors intersect. As seen in the depiction, in most of these domains there are significant gaps in the extent literature, or concepts that require further development and refinement, therefore offering new opportunities for interdisciplinary research to emerge.

However, we note that at this early point we intentionally attempted to avoid confining the boundaries of Positive Economic Psychology too rigidly, as we expect that this process will develops over time.

4.7 Research Methods in Positive Economic Psychology

At this early stage, it remains challenging to predict which research methods the new discipline will adopt, given the distinct methodological orientations of its parent fields. As previously highlighted, Positive Psychology, rooted firmly in Psychology, typically employs a narrower range of methods, while Economic Psychology takes a more eclectic approach, integrating psychological methods with economic modelling, field experiments, and large-scale surveys. These contrasts suggest that the methodological framework of the field will likely evolve dynamically, shaped by its research priorities and interdisciplinary collaborations.

Nonetheless, given the strong reliance on psychological research methods in both Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology, it is reasonable to expect these approaches to dominate the new discipline’s early research efforts. Over time, the field may incorporate more diverse methodologies to address complex phenomena, reflecting its interdisciplinary scope. This anticipated evolution underscores the need for flexibility in methodological choices as the field establishes itself. It also highlights the importance of developing a unique methodological identity that differentiates the discipline.

4.8 Future Possibilities and Challenges

We are currently navigating an era where interdisciplinarity is increasingly prevalent. Researchers regularly discover opportunities to undertake work at the juncture of various disciplines, and funding bodies are acknowledging that addressing societal challenges often requires research that transcends traditional disciplinary lines (Lyall et al., 2011). However, interdisciplinary research involves more than merely combining different disciplines into a single project. Considerable effort is required to harness the potential for synergy and to create a cadre of experts who bring together specialised knowledge from multiple fields. Common challenges include navigating diverse philosophical, linguistic, and methodological traditions that shape how knowledge is constructed and communicated. Integrating these differences requires fostering mutual understanding and respect among scholars from varied disciplines, which is often hindered by entrenched biases, disciplinary silos, and resistance to change. Critiques from established fields, scepticism about the legitimacy of the new domain, its positive lens and attempt to rebalance the field, may further complicate progress.

Unfortunately, there is little research on effective strategies that can aid researchers in efficiently collaborating and integrating knowledge across diverse fields. Consequently, one of the challenges involved in launching a new interdisciplinary field, particularly in this case where the nascent discipline draws on several disciplines or sub-disciplines (Economics, Psychology, Economic Psychology and Positive Psychology) is the requirement to deviate from their well-established disciplinary routes, and venture into uncharted territory.

Building on the strengths and addressing the limitations of its parent disciplines discussed earlier, Positive Economic Psychology is uniquely positioned to complement their weaknesses and harness their strengths across three key domains:

Balanced view of human capabilities: As noted, Economic Psychology often concentrates on deficits, such as irrational decision-making, financial mismanagement, and the negative consequences of economic behaviours. This focus has led to a pessimistic view of human capabilities. In contrast, Positive Psychology adopts a humanistic perspective, emphasising strengths, potential, and growth. However, this optimistic stance has been criticised for being overly idealistic. By integrating these perspectives, Positive Economic Psychology can foster a more balanced view of human capabilities in economic contexts. It can acknowledge the cognitive biases and systemic barriers identified by Economic Psychology while also recognising the potential for individuals, organisations, and communities to develop adaptive and effective financial behaviours.

Broadened scope: Positive Psychology has faced criticism for its heavy emphasis on intra-individual factors, such as personal strengths, optimism, and resilience, while overlooking the broader structural and systemic constraints – such as economic inequality and access to resources, that significantly shape individual experiences and outcomes. In contrast, Economic Psychology incorporates a multi-level approach, addressing factors that operate at the micro (individual), meso (organisational and community influences), and macro (societal and policy-level impacts) levels. It includes substantial research into structural and environmental elements that influence financial and economic outcomes, such as market dynamics, policy frameworks, and socio-economic conditions. Positive Economic Psychology bridges these approaches by offering a holistic approach that spans micro, meso, and macro levels, balancing personal agency with structural realities.

Novel interventions: Positive Economic Psychology aims to bridge the gap between the applied approach of Positive Psychology and the behavioural insights of Economic Psychology to create innovative tools for enhancing financial and economic wellbeing. While Positive Psychology has developed numerous interventions to promote wellbeing, resilience, and other positive outcomes, Economic Psychology has largely focused on understanding financial behaviours rather than addressing them through actionable strategies. The new discipline seeks to combine these strengths by designing interventions that foster adaptive financial behaviours while addressing maladaptive ones. These interventions also extend beyond individuals to empower communities and systems, supporting ethical financial practices and equitable access to resources.

In conclusion, while the challenges of integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives and navigating uncharted academic territory are significant, they also present opportunities for innovation and growth. By fostering collaboration across fields, and embracing both the strengths and limitations of its parent disciplines, Positive Economic Psychology has the potential to offer a more holistic and balanced approach for addressing real-world economic challenges.

4.9 Types of Interdisciplinary Approaches

In the realm of academic research, particularly relevant to fields such as Psychology, there are distinct approaches to integrating knowledge from various disciplines (Lyall et al., 2011). Each approach offers a unique framework for collaboration and knowledge synthesis:

Multidisciplinary research: This approach is characterised by the involvement of researchers from different disciplines who address a common research issue, yet maintain their disciplinary perspectives. In multidisciplinary research, the disciplines remain distinct; they contribute independently to the research question without integrating their methodologies or theoretical frameworks.

Interdisciplinary research: This type of research represents a more integrative approach, where knowledge and methods from different disciplines are combined. Researchers work collaboratively, transcending their disciplinary boundaries to develop new theoretical frameworks and methodologies. This approach emphasises synthesis and unification of diverse perspectives.

Transdisciplinary research: This category represents the most integrative approach, which involves collaboration that extends beyond academic disciplines to include stakeholders outside the academic sphere, such as policymakers and practitioners. This approach is centred around solving real-world problems rather than focusing solely on theoretical constructs.

Each of these approaches reflects a different level of integration and collaboration among various fields of study, illustrating the complexity and multidimensionality of addressing real-world issues (Lyall et al., 2011). We envision that Positive Economic Psychology will likely see all three types of integration emerging in the field and endorse transdisciplinary research as the favoured type due to the importance of the applied side in the new discipline.

4.10 Stages of Development

When interdisciplinary scientific disciplines are established and evolve, they typically undergo several stages, although the sequence may not be strictly linear (Repko & Szostak, 2020). These stages reflect the integration and synthesis of methods, concepts, and theories from multiple established disciplines (Choi & Pak, 2006). Our prediction is that Positive Economic Psychology will experience the following stages of development on its course from inception to maturation:

Initial exploration and interaction: In this stage, dialogues and collaborations between different fields begin, identifying common interests or problems that could benefit from an integrative approach (Klein, 2014).

Formation of interdisciplinary networks: Researchers from different disciplines start forming networks, often through conferences, workshops, and collaborative projects, which are crucial for sharing new ideas and methodologies (Lyall et al., 2011).

Development of shared language and methods: Interdisciplinary research faces the challenge of differing terminologies and methodologies. Developing a shared language and hybrid methodologies becomes essential at this stage (Lyall et al., 2011).

Emergence of new theoretical frameworks: New theories integrating aspects from the contributing disciplines often emerge at this stage, offering perspectives that were not possible within the bounds of each of the discrete disciplines (Lyall et al., 2011).

Institutionalisation: Gaining formal recognition, the interdisciplinary field might see the establishment of academic departments, dedicated journals, and degree programmes, along with targeted funding (Jacobs & Frickel, 2009).

Maturation and diversification: As the field matures, it may diversify into more specialised sub-fields and contribute to the development of its parent disciplines (Lyall et al., 2011).

Integration and impact on parent disciplines: The interdisciplinary field starts to significantly influence parent disciplines, sometimes leading to paradigm shifts or to the introduction of new methodologies in these fields (Rhoten, 2004).

Expansion and societal impact: Mature interdisciplinary fields often have a notable impact on society, influencing public policy, industry practices, and public understanding of important issues (Klein, 2014).

5 Conclusion

This article has embarked on an exploratory journey into the emerging field of Positive Economic Psychology, a discipline situated at the confluence of Positive Psychology and Economic Psychology. The initial sections provided foundational understanding by defining and delving into the history, mission, and core topics of both Positive Psychology with its focus on human flourishing and wellbeing, and Economic Psychology which examines the psychological underpinnings of economic behaviour.

The core section of this article focused on the introduction of Positive Economic Psychology as a distinct field. The section defined it, traced its origins, and outlined its core mission and principles, highlighting how Positive Economic Psychology integrates the strengths of its parent disciplines, to offer a novel perspective on human economic behaviours. The fusion of these disciplines not only broadens our understanding, but also opens new avenues for research, policy-making, and practical applications in Economics and Psychology.

The unique contribution of Positive Economic Psychology lies in its focused effort to enhance financial and economic wellbeing through interdisciplinary research and practical applications. Central to the discipline is the development and refinement of core theories and models that support its research objectives. It also aims to address critical gaps in both Economic Psychology and Positive Psychology by exploring underdeveloped concepts, introducing new psychological constructs to the economic domain, and designing innovative interventions and robust measurement tools. Distinctively, Positive Economic Psychology operates on positive assumptions about human nature, viewing individuals as capable of sound, ethical economic decisions and driven by intrinsic motivations for growth, prosperity, and prosocial contributions. It therefore holds a non-directive position and refrains from dictating how individuals should live their economic lives. In contrast to the deficit-based views and libertarian paternalistic approach applied in Economic Psychology, it employs constructive terminology, reframing financial challenges as surmountable and emphasising human potential and strengths. Its positive aim and agenda advance adaptive financial behaviours, responsible organisational practices, and policies that empower individuals and communities. It therefore offers a transformative pathway to financial prosperity and human flourishing.