Salutogenic Effects of Greenspace Exposure: An Integrated Biopsychological Perspective on Stress Regulation, Mental and Physical Health in the Urban Population

-

Suchithra Varadarajan

, Marilisa Herchet

, Matthias Mack

, Mathias Hofmann

, Ellen Bisle

, Emma Sayer

and Iris-Tatjana Kolassa

Abstract

Globally, urbanization is associated with increased risk for physical and mental diseases. Among other factors, urban stressors (e.g. air pollution) are linked to these increased health risks (e.g. chronic respiratory diseases, depression). Emerging evidence indicates substantial health benefits of exposure to greenspaces in urban populations. However, there is a need for an overarching framework summarizing the plausible underlying biological factors linked to this effect, especially within the context of stress regulation. Therefore, by outlining the effects of greenspace exposure on stress parameters such as allostatic load, oxidative stress, mitochondria, and the microbiome, we conceptualize an integrated biopsychological framework to advance research into the salutogenic and stress-regulatory potential of greenspace exposure. In addition, we discuss the understudied potential health benefits of biogenic volatile organic compounds. Our perspective highlights the potential for innovative greenspace-based interventions to target stress reduction, and their prospect as add-ons to current psychotherapies to promote mental and physical health in urban populations.

1 Introduction

1.1 Growing Cities, Growing Burden of Disease? On the Links Between Urbanization and Health Adversities

The United Nations estimated in 2018 that 55% of the global population resides in urban areas and projected that by 2050, 68% of the global population will be urban dwellers (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2018). On the one hand, urbanization, i.e. the process through which cities grow as well as the population shift from rural to urban areas, offers economic development, employment opportunities, better infrastructure, access to education and health care, etc. (Hou et al., 2019). However, on the other hand, it involves exposure to stressors such as air pollution, noise, violence, substance abuse, poor quality built environment, etc. (Hernandez et al., 2020; Pelgrims et al., 2021; Zona & Milan, 2011). These stressors pose several health burdens, for instance, ambient air pollution (including ozone, nitrogen dioxide [NO2], particulate matter, PM2.5 and PM10) is associated with diseases such as chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, depression, etc. (Khan et al., 2019). Thus, urbanization is widely discussed within the premises of increased risk for physical and mental diseases (Landrigan, 2017; Li et al., 2016; Pinchoff et al., 2020).

As urbanization is progressing rapidly, the health risks associated with it call for a mandate to incorporate health-promoting measures in all urban settings. One such measure is the creation and preservation of greenspaces (Taylor & Hochuli, 2017; Vilcins et al., 2022), such as parks, gardens, woodlands, or nature parks, within and in the periphery of urban areas. In line with this, the health beneficial effects of greenspace exposure are reflected across age groups, i.e. from new-borns to older adults (for systemic reviews and metanalysis, see Dzhambov et al., 2014; Houlden et al., 2021; Twohig-Bennett & Jones, 2018; Vanaken & Danckaerts, 2018; Yuan et al., 2021). An ecological study that used aggregated sales data of prescribed mood disorder medication, psycholeptics and psychoanaleptics from 2006 to 2014 reported a reduction in medication sales (1–2%) associated with an increase (10%) in relative cover of woodland, garden, and grass in an urbanized area, indicating a relationship between greenspace exposure with mental health benefits in urban cohorts (Aerts et al., 2022). Further, a survey (n = 2,089; age range 18–90; 83.1% females) conducted during the first 6 months of the Covid-19 pandemic reported a significant protective effect of tree-rich greenspace on depression as well as composite mental scores, i.e. a standardized and weighted score of parameters: Covid-19-related worries; depression and anxiety symptoms among the entire cohort. Especially proximity to tree-rich greenspace was associated with a reduction in both depression and composite mental health scores in the elderly, as well as a lessening of pandemic-related worries in the younger cohort (Wortzel et al., 2021). Another large survey (n = 5,566) conducted during the pandemic showed that better subjective wellbeing and better self-rated health in study participants were associated with perceived access to public greenspace (e.g. park or woodland) as well as access to a private greenspace (e.g. a private garden) (Poortinga et al., 2021). Thus, although greenspace exposure is one of many variables influencing human health, it is worthy of considerable attention, because well-researched urban greenspace intervention measures implemented in cities would benefit a large number of people every day for an extended period of time.

1.2 Greenspace Exposure as a Viable Approach for Stress Management and Wellbeing Promotion in the Urban Population

Even without any experimental interference, an increase in the duration of greenspace exposure (both visually and physically) is strongly linked to perceived stress reduction (Hazer et al., 2018). In urban communities, greenspace exposure could also facilitate health equity (Rigolon et al., 2021). For instance, spending time in greenspace is linked to a decrease in perceived stress among deprived urban communities (Roe et al., 2013; Ward Thompson et al., 2016). Within the health-care settings and research, there is an on-going discussion about prescribing greenspace exposure (i.e. nature and park) for stress reduction and overall health improvement in urban populations from diverse socio-economic-ethnic backgrounds (Kondo et al., 2020; Razani et al., 2018, 2020; Uijtdewilligen et al., 2019). In addition, greenspace-based interventions are a potential approach for stress reduction (Hartig et al., 2014; for a scoping review, see Jones et al., 2021). To explain the salutary effects of urban greenspace, several ecopsychological theories (e.g. stress reduction theory and attention restoration theory) have been postulated and tested in various experimental settings (see Ohly et al., 2016; Shaffee & Shukor, 2018 for systematic reviews), but a proper integration of biopsychological research results is slowly progressing (Herchet et al., 2022).

2 Understanding Stress Parameters as Crucial Health Indicators

2.1 Cumulative Stress and Allostatic load

Any real or perceived threat is considered a stressor, and any such stimulus that threatens homeostasis is termed stress (Schneiderman et al., 2005). The adaptation reaction to stress is termed allostasis (McEwen & Gianaros, 2011). Cumulative exposure to chronic stress can sensitize and cause alterations in neural and neuroendocrine responses in the human body and challenges the bodily adaptive capacity, which is referred to as allostatic load (Guidi et al., 2021; McEwen, 2000). Some of the pathophysiological components of allostatic load include alterations in the neuroendocrine stress regulation such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic–adrenal–medullary axis (SAM) along with the subsequent release of catecholamines (e.g. adrenaline/epinephrine, noradrenaline/norepinephrine, dopamine) and glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisol) (Godoy et al., 2018; Ketheesan et al., 2020). Allostatic load parameters generally include measurements associated with metabolic, neuroendocrine, immune, and cardiovascular functions (Juster et al., 2010; Seeman, 1997; Wiley et al., 2016). Notably, allostatic load parameters are not univocal, and future research might reveal new parameters that are currently not considered or are not yet known as markers of allostatic load.

Allostatic load is linked to a plethora of diseases and symptoms such as diabetes, cancer, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder (MDD), psychosis, anhedonia, and cognitive or memory decline (Carbone, 2021; Glover et al., 2006; Kapczinski et al., 2008; Mattei et al., 2010; Mazgelytė et al., 2019; McCaffery et al., 2012; Misiak, 2020; Savransky et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2017). Evidence and perspectives on the role of urban stressors like air pollutants in neuroendocrine sensitization and subsequent systemic immunological and metabolic impact point towards exposure to air pollutants as a potential contributor to allostatic load (Kodavanti, 2019; Montresor-López et al., 2021; Thomson, 2019).

2.2 Effects of Prenatal and Childhood Greenspace Exposure on Stress Parameters

Plausible intergenerational health benefits of maternal greenspace exposure were reflected in a pioneer study (n = 150 pregnant women) by Boll et al. (2020), which reported lower cortisol levels in umbilical cord blood associated with residential surroundings and proximity to greenspace (100 m buffer), regular viewing of greenspace through windows, and additional time spent in greenspace during pregnancy. The authors speculate that residential greenspace within a 100 m buffer might lessen exposure to PM2.5 and PM10. These findings might be important in the context of mental health as foetal exposure to sustained higher cortisol levels was found to have long-term adverse health effects; for example, higher maternal cortisol levels during pregnancy were associated with a larger amygdala volume and resultant affective problems in their female children (Buss et al., 2012). Likewise, prenatal maternal stress can influence amygdala volume in childhood, which predicted externalizing behavioural problems in both sexes (Jones et al., 2019). Promisingly, the presence of urban greenspace, such as botanical gardens, is shown to reduce PM2.5 concentrations compared to areas with less green cover (Junior et al., 2022), as certain tree species are highly effective in filtering particulate matter from the air (Chen et al., 2016; Sgrigna et al., 2020). Thus, further research is essential to replicate these crucial findings in other settings (e.g. gardens, residential/school areas, etc.).

The benefits of greenspace exposure are also evident in young children: A large study carried out among school children (n = 3,108, age = 7 years, 51.7% male) showed that greater accessibility to greenspace (i.e. 400 and 800 m) from a child’s school reduced allostatic load parameters, including biomarkers that characterize regulatory systems such as immune and inflammatory systems (high-sensitive C-reactive protein [hsCRP]), metabolic system (high-density lipoprotein [HDL], glycated haemoglobin [HbA1C], total cholesterol, waist-to-hip ratio) and cardiovascular systems (systolic blood pressure [SBP] and diastolic blood pressure [DBP]) (Ribeiro et al., 2019). These findings indicate substantial health-promoting potential of greenspace exposure in early life.

2.3 Effects of Greenspace Exposure During Adulthood on Stress Parameters

In adults, greenspace exposure has the capacity to substantially reduce stress. A field experiment with an urban working cohort (n = 77; activities = viewing and low-speed walking) reported decreased salivary cortisol levels in both large urban woodland and urban parks and in the built-up urban environment (near the main street and with few single urban trees). However, when compared to the built-up environment, being in an urban green park or large urban woodland was perceived to improve feelings of restoration, vitality, and good mood, as well as stress relief after work. Notably, woodlands showed a higher perceived restorative effect in general. The study further suggested the positive wellbeing effect of urban green parks (i.e. more than 5 ha) and large urban woodlands, especially for middle-aged women (Tyrväinen et al., 2014).

Other studies have revealed similar stress reduction with exposure to greenspace in adults. For example, a study by Ewert and Chang (2018) investigated the effect of “levels of nature” on stress reduction (n = 105, activities = hiking outdoors, or running or walking on an indoor track) by measuring salivary cortisol and α-amylase, as well as employing a perceived stress questionnaire in reference to visitation to three sites: a site with wilderness-like characteristics, a semi-natural municipal park, and an indoor urban built environment (exercise facility). Cortisol levels were decreased upon visiting the most natural site, but not to the park or exercise facility. Three indicators of stress reduction, i.e. decreased levels of demands and worries and increased level of joy, were reported after visits to the outdoor sites, whereas visits to the exercise facility were associated with increased levels of α-amylase as well as a reduction in levels of demand and worries. Overall, significant reductions in stress levels were reported for the site with the most natural characteristics. Similarly, an 8-week field experiment (n = 36) on urban nature experience, in which residents were instructed to sit, walk, or do both in an urban greenspace for at least 10 min three times a week, reported reductions in salivary cortisol and α-amylase levels of stress biomarkers, thus indicating a plausible dose–response relation between nature exposure and stress reduction (Hunter et al., 2019).

Dose–response analyses have reported that greater duration, frequency, and intensity of urban greenspace exposure were associated with reduced population prevalence of self-reported depression (Cox et al., 2017; Shanahan et al., 2016). For example, a cross-sectional population-based study (n = 206 adults) by Egorov et al. (2017) established a considerable association between greater vegetated land cover in an urban setting and reduced allostatic load. Greater residential greenery was associated with lowered adjusted odds of potentially unhealthy individual biomarkers: immune function (lower levels of fibrinogen, interleukin-8 [IL-8], vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 [VCAM-1]), neuroendocrine function (prominent levels of epinephrine, and low levels of nor-epinephrine, dopamine, and dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA] in serum), as well as metabolic functions (elevated levels of salivary α-amylase). Further, this study reported reduced odds of previously diagnosed depression in urban settings with greater greenspace cover.

Despite the many lines of evidence that interaction with greenspace can reduce stress in adults, the form of interaction can also play a role. For instance, a study among urban allotment gardeners determined the impacts of contact with nature, physical activity, and social interaction on chronic stress (Hofmann et al., 2017). The concentrations of cortisol in the gardeners’ hair before and after a gardening season (6 months apart) revealed that overall time spent in nature and physical activity were each associated with lower levels of cortisol. However, for participants facing very high levels of stressors, the relationship with time spent in nature was reversed, indicating that gardening may turn out to be an additional stressor in an already stressful life. While this finding needs replication, the study demonstrates a need for more research on the interactions between stressor intensity and biomarkers of chronic stress when assessing the potential benefits of greenspace exposure. Notably, we found no published studies on the allostatic load that exclusively focused on stress-reduction-related mental health effects of greenspace exposure; therefore, research endeavours on these important relations should be carried out.

3 Relationships Between Greenspace Exposure, Oxidative Stress, and Health Markers

Measuring oxidative stress could reveal important linkages between greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Oxidative stress is defined as the imbalance between the amount of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the neutralizing capacity of anti-oxidative defence systems (Valko et al., 2007). Physiologically, ROS are produced in several subcellular structures (mainly within mitochondria). ROS serve important signalling functions that are essential to coordinate metabolic, inflammatory, and stress response-related processes as well as to fight pathogens (López-Armada et al., 2013; Valko et al., 2007). However, if ROS production exceeds the physiologically optimal level and cannot be counterbalanced by the body’s antioxidant defence systems, ROS readily attack cellular macromolecules (e.g. lipids, proteins, DNA, and RNA), resulting in cellular damage (Turrens, 2003). These ROS-induced modifications (e.g. F2-isoprostane levels as a marker for lipid peroxidation) are also often used in biomedical research as stable biomarkers to assess the systemic state of oxidative stress (Nobis et al., 2020). Elevated levels of oxidative stress are associated with increased inflammatory processes referring to a state of ongoing cellular damage and increased demand for cellular repair and proliferation in various pathologies (Elmarakby & Sullivan, 2012). In the context of mental diseases, elevated oxidative stress levels and inflammatory cytokines are associated with stress-related diseases including MDD, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), and PTSD (Horn et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2018; Santoft et al., 2020; Varadarajan et al., 2022). However, further research is warranted to gain insights into alterations in metabolic processes and whether these alterations lead to increased oxidative stress in specific mental disorders.

Studies provide initial evidence that greenspace exposure might reduce oxidative stress and inflammation levels in urban children and adults. In urban children (n = 207, age = 10–13 years), accessibility to larger greenspaces was related to lower levels of oxidative stress measured using biomarker 15-F2t-isoprostane (15-F2t-IsoP) in the spot urinary sample (De Petris et al., 2021). Another cross-sectional study measuring oxidative stress levels in children using urinary levels of isoprostane (n = 323, age = 8–11 years) reported a reduction in oxidative stress levels associated with multisite greenness exposure, which was probably partially mediated by physical activities (Squillacioti et al., 2022). However, in an adult cohort (n = 408) with existing or risk of cardiovascular diseases, individuals residing in greener residential areas had lower levels of oxidative stress (measured in urinary levels of F2-isoprostane) and sympathetic activation as well as a better angiogenic profile compared to individuals living in less green areas, thus indicating a potential beneficial effect of residential greenspace on cardiovascular health (Yeager et al., 2018).

The multiple lines of evidence for reduced oxidative stress levels upon exposure to urban greenspace indicate a plausible anti-inflammatory effect, which implies health benefits across age groups of the urban population. This further emphasizes the need to preserve as well as promote greenspace in and around urban areas, in order to harness its potential anti-inflammatory effect.

4 Mitochondria as a High-Potential Variable in the Interplay of Greenspace Exposure and Health

4.1 Implications of Mitochondria in Urban Health

Mitochondria, the powerhouses of our cells, are the main producers of cellular biochemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondria possess their own circular, double-stranded mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as a vestige of their bacterial heritage (Wallace, 2015). Oxidative stress and inflammation are robustly associated with mitochondrial functioning (Patergnani et al., 2021). Mounting evidence suggests that mitochondria are additionally involved in the regulation, initiation, and resolution of immune responses and inflammatory processes (reviewed in Mills et al., 2017). Measurements of mitochondrial oxygen consumption as well as oxidative stress levels indicate that mitochondrial alterations are involved in the development of a variety of chronic stress-associated mental health diseases such as PTSD, depression, etc. (Hitzler et al., 2019). Picard et al. (2014, 2017) put forth the concept of mitochondrial allostatic load, i.e. an allostatic load mechanism could cause additional energy demands in the body as well as biological changes (molecular, structural, and functional) in mitochondria upon chronic stressor exposure.

Mitochondrial health is relevant in the context of urban health, as there is evidence that environmental stressors such as air pollutants affect mitochondrial function. For instance, prenatal exposure to particulate matter (i.e. measures of average and maximum PM2.5) was associated with long-term alterations in mitochondrial respiration function in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), indicating that the mitochondria may indirectly mediate some of the effects of air pollution on neurodevelopment and behaviour in ASD children (Frye et al., 2021). Potential early life health repercussions of air pollution were also observed in a study that reported a decrease in placental mtDNA content (mtDNAc; measured using DNA extracted from placental tissue n = 174 and umbilical cord leukocytes n = 176) linked with increased PM10 exposure during the last period of pregnancy, whereas an increase in placental mtDNAc was observed when residential distance to main roads was doubled (Janssen et al., 2012). Such alterations in mtDNA content are implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial diseases (for a systematic review, see Valiente-Pallejà et al., 2022).

Preliminary evidence indicates that increased residential greenspace is associated with a higher mtDNAc measured in buccal cells in primary school children (n = 246, age = 9–12 years), where proximity to greenspace, i.e. within a 500 and 100 m radius, had the strongest effect on mtDNAc (Hautekiet et al., 2022). However, we still do not know the health implications of this result, and the effect of greenspace exposure on mitochondrial health is sparse. Considering the vital role played by mitochondria in inflammatory, immunoregulatory, metabolic processes, and resultant stress regulation, advancing our understanding of the relationships between urban greenspace exposure and mitochondrial health could allow us to determine how greenspaces mediate or improve mental health outcomes.

4.2 Can Green Exercise Intervention Target Mitochondrial Health?

Some of the health benefits of greenspace exposure conceivably occur because the presence of greenspace can facilitate and promote physical activities (e.g. exercises, walking, cycling, etc.) (Flowers et al., 2016; Yuen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). However, while exercise alone is also beneficial for human health, green exercise, i.e. exercising in greenspaces, often fosters and exceeds these benefits in comparison with indoor or other non-green exercise forms (Araújo et al., 2019). Green exercise is a comparatively well-studied subtopic of greenspace exposure, with studies demonstrating benefits for stress reduction, mood improvement, restoration of mental fatigue, improved perception of health, etc. (Bamberg et al., 2018; Calogiuri et al., 2015; Gladwell et al., 2013).

The exercise-induced moderate level of ROS production is considered favourable for various cellular functions (e.g. apoptosis, immune response) as well as an increase in the antioxidant capacity (Ascensão et al., 2003). Although exercising is also discussed within the context of improving mitochondrial health and promotion of wellbeing (see Huertas et al., 2019; Oliveira & Hood, 2019; Sorriento et al., 2021), the precise mechanisms underpinning the beneficial effects of exercise are not sufficiently understood. Nevertheless, the effect of exercise on mitochondrial biogenesis, i.e. synthesis of new mitochondria, has been discussed (Islam et al., 2020). To assess the connections between exercise, mitochondria, and greenspace exposure, it would be relevant to investigate whether green exercise offers additional health benefits compared to exercising in other settings. Further, studies are needed to assess whether therapeutically designed green exercise could be a potential intervention to target mitochondrial health in urban populations. Such investigation should take into consideration ROS production and signalling linked to exercising and greenspace exposure, and specifically, whether green exercising is linked to the modulation of mitochondrial function.

5 The Key Role of Human Gut Microbiota in Stress and Overall Health Regulation

5.1 Urban Health and the Gut Microbiome Connection

The key role of human gut microbiota in the regulation of stress, inflammation, metabolism, immunity, and health in general is widely discussed; yet studies that explored the association of human gut microbiota with greenspace exposure are scarce (Clemente et al., 2012; Larsen & Claassen, 2018). Alterations in gut microbiota composition, termed gut dysbiosis, have been linked to imbalanced immune responses, acute or chronic systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance (Amabebe et al., 2020; Peterson et al., 2015; Yoo et al., 2020). Indeed, gut dysbiosis has been associated with numerous diseases, including autoimmune diseases, metabolic diseases, neurogenerative diseases, ASD, ADHD, depression, and anxiety (Fröhlich et al., 2016; Hsiao et al., 2013; Levy et al., 2017; Rogers et al., 2016; Vuong & Hsiao, 2017). In the context of urban health, an improved understanding of the human gut microbiome is essential, as exposure to urban stressors like air pollution is linked to alterations in gut microbiota composition (Mousavi et al., 2021; Mutlu et al., 2018).

5.2 Can Urban Gardening Improve Human Gut Microbiota Composition?

Several studies have highlighted the potential health benefits of urban gardening. Urban gardens are small-scale open greenspaces located within or near urban residential areas, which contribute to community-building and empowerment and can encourage sustainable agriculture practices (Nikolaidou et al., 2016). A systematic review (k = 8 articles) by Lampert et al. (2021) showed a significant association between better mental health, physical health, and wellbeing in community gardeners when compared to non-gardeners. Irrespective of their age (average age 40 years and above), community gardeners reported less perceived stress, increased social support and contacts, better health status, and higher levels of life satisfaction. Household gardening is also linked to emotional well-being, with a higher average net effect of gardening for vegetables vs. ornamental plants and low- vs. high-income gardeners (Ambrose et al., 2020). In this particular study setting, gardening in companies and various ethnicities showed no significant differences.

Along with the health-promoting physical activities involved in urban gardening, it can also substantially encourage healthy dietary behaviour, such as improved nutrition intake in the form of fresh fruits and vegetables (Garcia et al., 2018; for systemic reviews, see Gregis et al., 2021; Lampert et al., 2021), which establishes a potential link between urban gardening and the gut microbiota. Poor dietary nutritional intake is linked with gut dysbiosis and related diseases (e.g. anorexia nervosa, obesity, anxiety, depression, etc., see Firth et al, 2020; Taylor & Holscher 2018; Tidjani Alou et al., 2016), whereas healthier nutritional intake (e.g. fresh fruits and vegetables) promotes a gut bacterial composition that is conducive for health (Asnicar, 2021; García-Vega et al., 2020; van der Merwe, 2021). Diet quality linked with gut microbiota composition is in turn related to the modulation of inflammatory, immunity, and metabolic functions, which are involved in stress and physical and mental health (Altajar & Moss, 2020; Asnicar, 2021; Madison & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2020; Mörkl et al., 2020). Thus, the salutogenic effect of nutritional intake in relation to gut microbiota composition emphasizes the necessity to promote urban greenspaces like community and household gardens, which could increase the accessibility to freshly grown vegetables and fruits for urban populations. For example, a comparison of non-gardening families (n = 9 families) to gardening families (n = 10) during peak gardening season revealed that higher alpha bacteria diversity in the faecal sample of gardeners and higher presence of specific faecal bacteria in lower abundance (Brown et al. 2022). Interestingly, this study also detected soil-derived bacteria in the faecal samples of most of the gardening participants, thus indicating the environmental and bodily microbial connection. In addition, self-reported dietary intake also shows that gardening families have higher levels of iron (24%), selenium (22%), vitamin C (67%), and vitamin K (27%) than non-gardening families. Such relationships between nutrition and mental health are increasingly becoming apparent; for example, nutrition intake was linked to mental health in an adolescent girls cohort (Jafari-Vayghan et al., 2023).

Considering the initial evidence for the influence of gardening on gut microbiota composition and improved nutrition, gardening approaches for boosting gut health should be further explored. Dietary intake and gut microbiome composition is also linked with socio-economic factors (Christian et al., 2020; Kwak et al., 2024). Consequently, encouraging garden spaces can be a viable health promotion approach in urban settings, especially for lower/middle-income households. Moreover, initial evidence on horticulture or garden therapy indicates its use for improving mental health (for a systematic review and metaanalysis, see Zhang et al., 2022). Nevertheless, we do not know whether greenspaces such as urban gardens can contribute to stress regulation and enhance mental health by improving human gut microbiota composition, indicating an exciting new avenue for future research.

6 Targeting Human Health by Increasing Microbiota Diversity

6.1 On the Links Between Biodiversity and Health

The biodiversity hypothesis proposes that the presence of diverse macrobiota (i.e. organisms that can be seen with the naked eye like insects, earthworms, etc.) and microbiota (i.e. microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, protozoa, viruses, etc.) in a given environment play a crucial role in altering and improving the human microbiome, thus significantly influencing inflammatory processes and immune function (Haahtela, 2019; von Hertzen et al., 2015). Decreased human interaction with a diverse natural environment is suggested to detrimentally affect the composition of human commensal microbiota, which adversely affects inflammatory and immunoregulatory pathways, leading to allergic dispositions and diseases (Hanski et al., 2012; von Hertzen et al., 2015). For instance, reduced exposure to a diverse environmental microbiome (i.e. microbiota along with its genes and metabolites) is postulated to contribute to the surge in mental health diseases in Western societies (Hoisington et al., 2018). Simultaneously, the “old friends” hypothesis proposes that in a biodiverse environment, co-evolvement of humans with diverse microbiota (i.e. old friends) was vital to resilient immune system development in humans (Rook, 2005). Furthermore, it is proposed that in urban settings, reduced exposure to microbial diversity in the perinatal phase could intensify consequences of psychosocial stressors, which in turn could detrimentally affect microbiota modulation, inflammatory and immunoregulatory processes, and hence increase the risk for physical and psychological diseases, as well as reduce stress resilience in urban communities (Rook, 2013; Rook et al., 2013). Accordingly, microbial exposure in early life predicts lower levels of C-reactive proteins (CRPs) in adulthood, thus indicating a reduction in inflammatory responses and conceivable lifelong health benefits of early-life microbial exposure (McDade et al., 2010).

6.2 Biodiversity Intervention: A Novel Approach to Target Human Microbiota

Initial evidence from human intervention trials corroborates both the biodiversity hypothesis and the “old friends” theory. For example, during a 28-day-long biodiversity intervention involving covering day-care centre yards with natural forest floor vegetation and sod to improve microbial biodiversity, Roslund et al. (2020) reported alterations in skin and gut microbiota in urban day-care children (n = 75, age: 3–5 years). By ensuring that the children touched the green materials, this biodiversity intervention sustained high commensal skin microbiota diversity (Gamma proteobacteria) as well as increased gut bacterial diversity (Ruminococcaceae). Following these alterations in microbial diversity, modulation of plasma cytokine levels, which were presented in the increased ratio between IL-10 and IL-17A, as well as a positive link between skin Gammaproteobacterial diversity and blood Treg cell frequencies was reported. The authors inferred that playing in microbiologically diverse greenery and dirt could change skin and gut microbiota, along with alterations in the immune system. In a subsequent 2-year biodiversity intervention study (n = 89, age at the beginning of the study = 3–5 years), Roslund et al. (2021) further showed that the commensal microbiota composition improved in children in intervention day-care centres compared to controls in standard day-care centres. The biodiversity intervention enriched mycobacteria, a non-pathogenic bacterium present in the soil surface, and commensal skin Alpha-, Beta, and Gammaproteobacteria in children. At the same time, the relative abundance of potentially pathogenic bacteria such as Haemophilus, Streptococcus sp., Veillonella sp., and parainfluenza on skin was reduced. Furthermore, the relative abundance of Clostridium sensu stricto (various members of this species are pathogenic) was lower in the guts of the intervention children. Overall, these results indicate the potential efficacy of biodiversity interventions in immune regulation by influencing human commensal microbiota composition.

This promising preliminary evidence calls for greater consideration of therapeutically designed biodiverse greenspaces in urban settings for people across age groups. For example, designated areas in a public park could be improved with materials that boost the diversity of macro- and microbiota and complement the given natural habitat, e.g. green materials from the forest floor, sods, etc. As we are beginning to understand the various ways in which biodiversity can be increased within urban settings, future research into the links between biodiversity and health outcomes could contribute towards creating cost-effective, biodiverse greenspace intervention areas for public usage, which could provide mental health benefits for urban dwellers.

7 The Potential Beneficial Role of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (BVOCs) in (Mental) Health

One underexplored aspect of the benefits of urban greenspace on human health is the emission of BVOCs by plants. Plant-derived BVOCs are secondary metabolites emitted from leaves, flowers, stems, and roots (Loreto et al., 2014), which have various functions such as signalling molecules, in responses to abiotic stress, and as defence against herbivores and pathogens (Šimpraga et al., 2019). Around 1,700 BVOCs have been identified to date (Aydin et al., 2014); they mostly comprise low-molecular-weight lipophilic compounds from three biosynthetic classes: terpenes, benzenoids, and fatty acid derivatives (Wu et al., 2021). Much attention has been given to BVOCs in urban settings due to their potential role in air pollution (Eisenman et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2017). BVOCs are highly radical, and, upon exposure to sunlight, some BVOCs react with nitrogen oxides (NO x ) to produce ozone (Duan et al., 2023). As a result, research into the health effects of BVOCs in urban settings has largely focussed on ozone formation and identifying tree species with low BVOC emissions for urban planting (Samson et al., 2017). However, the uptake of ozone and filtering of particulate matter by trees could outweigh the contribution of BVOCs to pollutant formation (Calfapietra et al., 2013), and there is mounting evidence that many BVOCs are beneficial to human health and wellbeing (Antonelli et al., 2020).

Several BVOCS, such as limonene, pinene, and terpenoids, are reported to have anti-inflammatory effects (Antonelli et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020). High emissions of several BVOCs by trees are purported to contribute to the salutary effects of “forest bathing” (Bach Pagès et al., 2020), and increased concentrations of monoterpenes, which are emitted in high concentrations by coniferous trees, have been detected in blood samples after 1 h (n = 4, Sumitomo et al., 2015) or 2 h of forest walking (n = 10, age = 20–40 years, 40% male; Bach et al., 2020). Inhalation of monoterpenes has been linked to anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, as well as stress relief (Zhao et al., 2023). For example, measurements of heart rate variability and brain wave activity during a controlled study of male university students (n = 9, age = 19–25 years) demonstrated that low doses of bornyl-acetate, a monoterpene produced by numerous conifers, induced autonomic relaxation during 30 min of computer-based tasks and reduced the level of arousal afterwards (Matsubara et al., 2011). The largest observational study to date (n = 505, 35% male, age 18–70 years) demonstrated that total monoterpene concentrations at 39 sites, including montane forest, coastal pine forest, and urban park, were associated with a decrease in anxiety metrics, based on State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire (Donelli et al., 2023). Of the monoterpenes, α-pinene shows particular promise for clinical applications (Salehi et al., 2019), and this study showed that reduced anxiety was strongly linked to α-pinene concentrations across sites (Donelli et al., 2023). However, despite numerous lines of evidence for the potential benefits of BVOCs to human health and well-being, the majority of studies to date have been conducted with cell models or animal models (Cho et al., 2017), and there have been very few cohort studies in humans. Additional controlled studies in urban settings are urgently needed to determine whether BVOCs from urban greenspace could contribute to human stress regulation and overall well-being. Insights from such studies could be utilized for preserving and designing greenspaces featuring tree species that emit beneficial BVOCs.

8 Discussion and Summary

8.1 Salutogenic Potential of Exposure to Urban Greenspaces

We have presented biomarker-based human studies that reported the beneficial effects of greenspace exposure on physiological processes associated with stress regulation. This beneficial effect is substantiated by variations in biomarkers in humans exposed to a given greenspace setting, and these effects were observed in diverse cohorts, i.e. from children to adults. Factors that facilitate this salutogenic effect of greenspace exposure include proximity (i.e. nearby presence of greenery in a residential or school area) and accessibility (e.g. a public park in the neighbourhood), as well as levels of nature (i.e. characteristics of nature) and the dose-response of exposure (i.e. duration, frequency, and intensity) in a given greenspace setting. In general, proximity to greenspace is reported to reduce stress parameters, which could contribute to improved stress regulation. Intergenerational effects of greenspace exposure in stress regulation were also apparent, e.g. as reduced cortisol levels in umbilical cord blood, linked to proximity to residential greenspace during pregnancy. In addition, proximity to greenspace in children (i.e. in their school area) was associated with reduced allostatic load, which indicates that greenspace exposure could promote health in early life. Among urban cohorts, greenspace exposure was linked to a reduction in oxidative stress, thus plausibly influencing inflammation. Proximity, accessibility, intensity (i.e. quality and quantity), and levels of greenspace exposure (e.g. woodlands, park) likely play a role here. In schoolchildren, a higher degree of greenspace exposure and accessibility (multisite green areas) near schools were linked to reduced oxidative stress. In adults, residential greenspace is linked to reduced allostatic load and lower levels of oxidative stress. In addition, specific characteristics of the vegetation, such as BVOCs, have been linked to anti-inflammation, stress relief, and relaxation, among other benefits.

The human microbiome and mitochondria are known to be pivotal for mediating stress response processes. Promising initial evidence shows that biodiversity interventions beneficially alter the microbiota composition of skin and gut in children, thus indicating the salutogenic potential of biodiversity exposure in early life. Similarly, in a gardening family cohort, faecal microbiome and soil-derived bacteria presence differed from that of a non-gardening cohort, and gardeners also benefitted from nutritional gain through increased intake of vitamins and minerals. Pioneering studies show that proximity and greater exposure to greenspace is linked to higher mtDNAc (in buccal cells) in primary school children. Yet, the specific health aspect of this link is unknown, thus warranting further investigation. In addition, the interaction between microbiota and mitochondria is discussed as a potential factor in regulating the immune system and inflammation (Saint-Georges-Chaumet et al., 2015; Saint-Georges-Chaumet & Edeas, 2016). Therefore, it is important to investigate if and how microbiota–mitochondria interactions act as a hinge factor in modulating inflammation, immune responses, and associated stress regulation and to uncover the potential role of greenspace exposure in these complex processes.

8.2 Consequences for Health Interventions

Initial evidence linking greenspace exposure to reductions in allostatic load parameters, inflammation and oxidative stress, as well as alterations in gut and skin microbiome and higher mtDNAc in various age groups shows the potential for greenspace-based interventions to regulate stress. To encourage greenspace exposure to urban lifestyles, there is a need to scale up access to greenspace in multiple urban environments, including residential areas, educational or work areas, and public spaces, and promote urban gardens. In the mental health field, urban greenspace-based approaches such as garden therapy, green exercise, and biodiversity interventions are promising for therapeutic purposes and also as add-on interventions to improve psychotherapy outcomes. In addition, prescribing visits to biodiverse greenspaces and nature parks could also be a viable approach to support urban dwellers to better cope with stressors associated with urbanization. The great potential for greenspace-based interventions warrants further research into the stress regulatory and health promotional effect of urban greenspace exposure.

8.3 An Integrated Biopsychological Framework on the Salutogenic Effects of Urban Greenspace Exposure

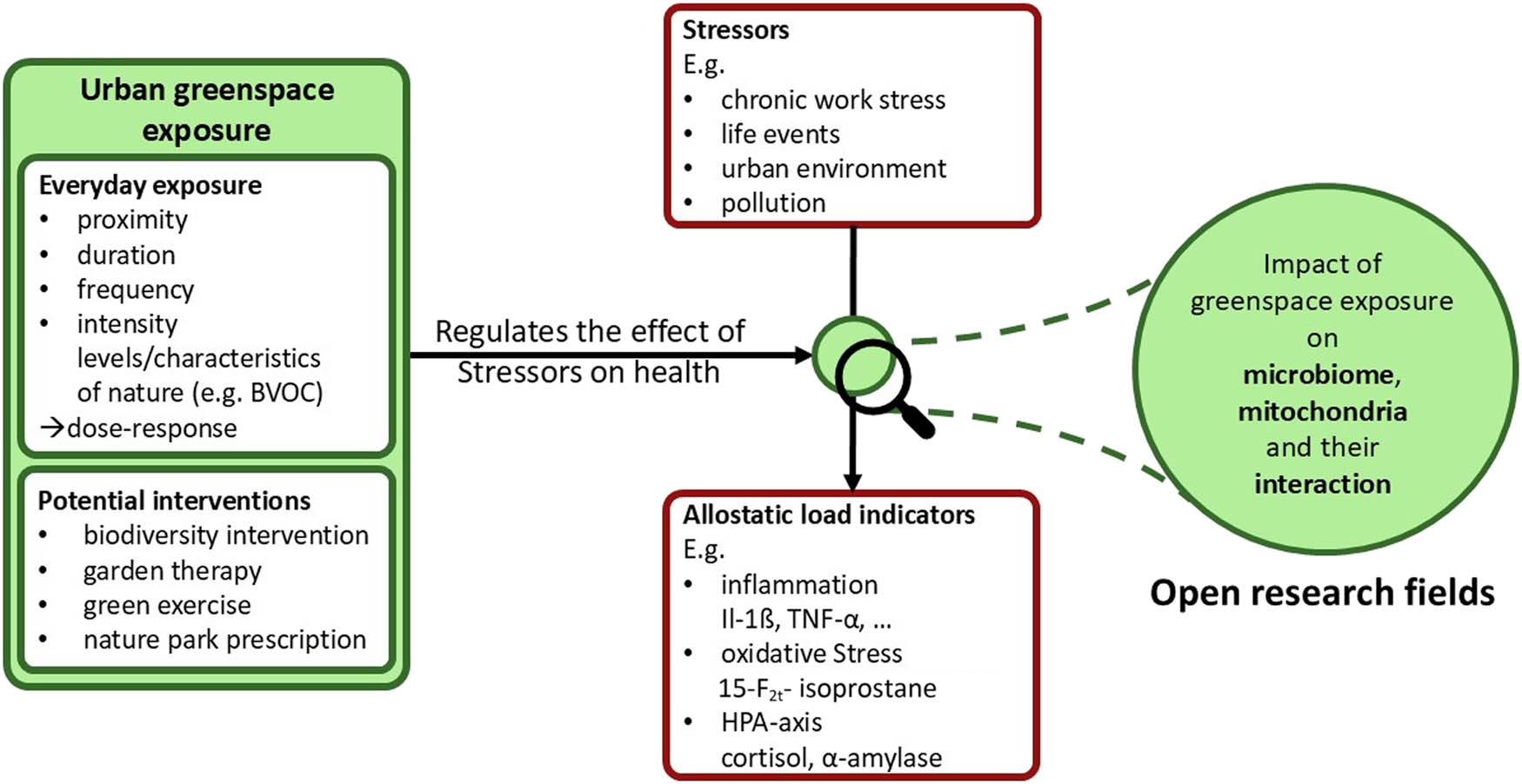

Taken together, the existing evidence and irrefutable knowledge gaps underscore the necessity to expand our understanding of the stress regulatory effects of greenspace exposure. Here, we conceptualize an integrated biopsychology framework to guide future interdisciplinary research (Figure 1).

An integrated biopsychological framework on the salutogenic effects of greenspace exposure: Regular exposure to urban greenspace improves (mental) health in a dose–response manner. Previous studies employed independent biomarkers of stress parameters (e.g. cortisol, α-amylase, 15-F2t-IsoP, hsCRP, and IL-8) as well as entire allostatic load parameters. Future investigations should address the impact of greenspace exposure on mitochondrial function, human gut microbiome diversity, and its mutual influence. Knowledge derived from such investigations could enable innovative greenspace-based interventions, such as biodiversity intervention, garden therapy, and green exercise, and encourage nature park prescriptions.

Our framework proposes that greenspace has – in a dose–response manner – stress-reducing effects which are likely to be dependent on proximity, duration, frequency, and intensity of exposure. In part, the protective effects might be explained by bodily relaxation, reduction in stress parameters like cortisol, reductions in inflammatory and oxidative stress levels, alterations in the human (gut) microbiome and improved (mitochondrial) allostatic load parameters, as well as their mutual interaction. Future research should investigate in more detail the underlying biological mechanisms involved in the salutogenic effects of greenspace exposure, as this knowledge can be used for developing targeted interventions. Understanding these mechanisms could inform primary (mental) health promotion measures within urban settings. Finally, psychotherapy could purposely use greenspace exposure-based interventions as add-ons to improve therapeutic efficacy in stress-related diseases in the future. For a brief description of stress/allostatic load parameters mentioned in this article as well as for future potential parameters of allostatic load see Tables 1 and 2.

Brief description of stress/allostatic load parameters mentioned in this article

| System | Biomarker | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | SBP | SBP is the arterial pressure measured during the contraction of the heart’s left ventricle. It reflects the force exerted by the pumping action of the heart, pushing oxygenated blood into the arteries. A normal SBP range is considered to be around 90–120 mmHg. Deviations from this range can indicate potential cardiovascular issues, such as hypertension or other cardiovascular diseases. Monitoring and maintaining optimal SBP levels is crucial for overall cardiovascular health (Brzezinski, 1990) |

| DBP | DBP refers to the arterial pressure measured during the relaxation phase of the heart, specifically when the heart’s left ventricle is filling with blood. It signifies the pressure exerted on the walls of the arteries during this resting period. Normal DBP typically falls within the range of 60–80 mmHg. Deviations from this range can indicate potential cardiovascular abnormalities, such as hypotension or conditions like hypertension. Monitoring and maintaining optimal DBP levels are crucial for assessing cardiovascular health and managing related conditions (Brzezinski, 1990) | |

| Fibrinogen | Fibrinogen is a glycoprotein and a key component of the coagulation system in the blood. It is synthesized by the liver and circulates in plasma as an inactive precursor. Tissue or vascular damage induces the conversion to fibrin that triggers the formation of blood clots. Elevated levels of fibrinogen are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis and cardiovascular diseases (Pieters & Wolberg, 2019) | |

| Immune | IL-8 | IL-8 is a cytokine and signalling protein involved in immune responses and inflammation. It is produced by various cell types, including immune cells and certain epithelial cells. IL-8 acts as a chemotactic factor, attracting and activating immune cells, to sites of inflammation or infection. Excessive or dysregulated production of IL-8 can contribute to chronic inflammation and various inflammatory disorders (Cesta et al., 2022; Qazi et al., 2011) |

| VCAM-1 | VCAM-1 is a cell adhesion molecule involved in the regulation of inflammation linked to vascular cell adhesion and the transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Dysregulation of VCAM-1 expression has been implicated in various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, e.g. asthma, rheumatoid arthritis (Kong et al., 2018) | |

| hsCRP | hsCRP is an inflammatory marker that is produced by the liver and released into the blood. Elevated hsCRP levels are associated with cardiovascular risks (Bassuk et al., 2004) | |

| Cortisol | Cortisol, a glucocorticoid hormone, is synthesized and released by the adrenal cortex in response to stress. It is controlled by the hypothalamic–pituitary axis and regulates metabolism, blood sugar levels, and immune response. Elevation and dysregulation of cortisol levels are linked to diseases such as depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, etc. (Dziurkowska & Wesolowski, 2021; Lee et al., 2015; Van Den Heuvel et al., 2020) | |

| Neuroendocrine | Epinephrine | Epinephrine, also known as adrenaline, is a hormone released during stress or threat. It increases heart rate, blood pressure, and energy availability, preparing the body for a “fight or flight” response. Epinephrine also enhances respiratory function and mental alertness (Paravati et al., 2023) |

| Norepinephrine | Norepinephrine, also called noradrenaline, is a neurotransmitter and hormone involved in the body’s stress response. It is released by the sympathetic nervous system in response to stress or threat. Like epinephrine, norepinephrine increases heart rate, constricts blood vessels, and raises blood pressure, preparing the body for action. It helps regulate attention, arousal, and mood and plays a role in the fight-or-flight response. Norepinephrine is involved in maintaining alertness and focus, as well as modulating mood and emotions (Paravati et al., 2023) | |

| Dopamine | Dopamine is a neurotransmitter involved in reward, motivation, movement, mood, and cognition. It plays a crucial role in the brain’s pleasure pathways and helps regulate attention and learning. Imbalances in dopamine levels are associated with various neurological conditions (Marsden, 2006) | |

| DHEA | DHEA is a steroid hormone produced in the adrenal glands. It is involved with neuroprotection, mood regulation, cognitive performance, etc. It is linked to diseases such as schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, PTSD, dementia, etc. (Maninger et al., 2009; Vuksan-Ćusa et al., 2016) | |

| HDL | HDL is a beneficial lipoprotein involved in cholesterol transport. It helps remove excess cholesterol from tissues and arteries, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease. Higher levels of HDL are generally associated with a lower risk of dementia, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, etc. (Jomard & Osto, 2020; Kjeldsen et al., 2022; Wong et al., 2018) | |

| Metabolic | HbA1C | HbA1c is a form of haemoglobin that indicates average blood glucose level over a period of the previous 8–12 weeks. Higher levels are associated with diabetes, higher risk of colorectal adenoma (a precursor of colorectal cancer), etc. (Yu et al., 2021) |

| Total cholesterol | It constitutes low-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, and HDL. Total cholesterol level <200 mg/dl is linked to disease risk, e.g. cardiovascular diseases (He et al., 2021) | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | It is a measurement calculated by dividing the waist circumference by hip measurement, and higher levels characterize the distribution of more adipose fat, and this is linked to diabetes, cardiovascular risks, etc. (De Koning et al., 2007) |

Future potential parameters of allostatic load

| Gut health | Microbiomics | The gut microbiome refers to the collection of microorganisms in the digestive tract. It plays a crucial role in digestion, immune function, and overall health. Imbalances in the gut microbiome have been linked to various health conditions, whereas higher microbial diversity is linked to beneficial effects on mental health |

| Gut permeability | The gut epithelial cells and the mucus layer constitute a barrier that hinders microorganisms from entering the blood stream, while on the other hand being essential for nutrient absorption. Chronic stress can damage the gut barrier, which could result in bacterial translocation, increased inflammation, and reduced nutrition uptake | |

| Mitochondrial health | Mitochondrial respiration | Mitochondrial respiration is the process by which cells generate ATP within the mitochondria. It involves the transfer of electrons through the electron transport chain, leading to the pumping of protons and the subsequent synthesis of ATP-by-ATP synthase. Mitochondrial respiration is a vital pathway for cellular energy production. Dysregulated mitochondrial function in various cell types has been associated with physical and mental health conditions |

| Routine/basal respiration | Routine respiration represents the oxygen consumption rate of mitochondria under normal physiological conditions in the absence of any specific stimulation or stress. Elevated values may indicate increased cellular energy demand | |

| Leak respiration | Leak respiration measures the oxygen consumption rate that occurs due to the proton leak across the mitochondrial inner membrane. This leak pathway allows protons to re-enter the matrix. Elevated values indicate increased permeability of the mitochondrial inner membrane, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction or inefficiency | |

| ATP-turnover | ATP-turnover reflects the oxygen consumption rate associated with ATP synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation. This measurement represents ATP provision under routine conditions. Decreased values may indicate reduced energy demand or impaired ATP production | |

| Spare respiratory capacity | Spare respiratory capacity represents the ability of mitochondria to respond to increased energy demands by increasing their ATP production capacity. It is calculated as the difference between maximum respiration and routine respiration. Decreased values may indicate a limited capacity to respond to increased energy demands | |

| Coupling efficiency | Coupling efficiency refers to the efficiency with which mitochondria convert energy derived from the electron transport chain into ATP synthesis. It represents the ratio between ATP synthesis and oxygen consumption. Decreased values indicate an inefficiency in converting energy into ATP | |

| Mitochondrial complex activity | Mitochondrial complex activity refers to the function and efficiency of the complexes within the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This activity is crucial for efficient energy production. Altered complex activity can indicate mitochondrial dysfunction | |

| Mitochondrial biogenesis (biomarker, e.g. mtDNA, PGC-1α, Mitofusin) | Markers for mitochondrial biogenesis reflect the process of increasing and decreasing mitochondrial mass and activity within cells. Alterations in mitochondrial biogenesis may contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction in various pathologies | |

| Oxidative stress | Biomarkers, e.g. 15-F2t-isoprostane (15-F2t-IsoP), malondialdehyde, glutathione | Oxidative stress represents the imbalance between the production of ROS and the body’s antioxidant defence system. Elevated levels of oxidative stress can lead to cellular damage (e.g. damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA) |

8.4 Strengths and Limitations

This perspective article provides an overview of the potential everyday therapeutic benefits of greenspaces for better stress regulation in urban populations. Our perspective paper brings together existing evidence and highlights research gaps on the effects of greenspace exposure in stress regulation within a biopsychology framework. Thus, we aim to stimulate global interdisciplinary research collaboration to advance our understanding of the precise biological mechanisms involved in stress regulation by greenspace exposure. Deriving such in-depth knowledge could encourage the development of viable and cost-effective greenspace-based interventions for the (mental) health of urban populations, thus addressing a pressing need of our time.

As a narrative review with a focus on the benefits of urban greenspace exposure for human health, there could be some unavoidable bias in the selection and reporting of the studies reviewed. However, given the scarcity of research into many of the discussed aspects of greenspace exposure, greater discrimination of the included works would have reduced the information value of the review. For example, we recognize that socioeconomic status (i.e. wealthier people choosing to live near greener and biodiverse neighbourhood) is an influencing factor for greenspace access that was not considered as a criterion when selecting the included articles. In addition, we acknowledge that health challenges such as allergies are also linked to greenspace and nature exposure, but these were beyond the scope of our review. Our review does not attempt to critically evaluate the presented research articles, as our aim was to provide an overview of the state-of-the-knowledge. Finally, it is also important to note that, besides greenspace exposure, other stress reduction approaches, such as taking a short nap, meditation, listening to music, etc., could be effective for urban populations. However, urban greenspace has additional benefits, such as enhancing biodiversity, reducing pollution, and providing shade and cooling in urban heat islands. Thus, improved understanding of greenspace effects on human health and wellbeing will inform and support efforts to increase access to purpose-designed greenspaces for urban populations.

-

Funding information: SV, I-TK, MM, and EB were funded by the own resources of Ulm University. MH and MH were funded within the project “Stadtnatur unterstützt psychisches Wohlbefinden – Effekte und Wirkmechanismen (STUPS)” by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung; BMBF) under the reference 01EL2023.

-

Author contributions: SV conceptualized, wrote, and revised the original draft. I-TK, MH, MM, MH, EB, and ES revised the original draft and contributed to the original draft, conceptualization and revisioning process.

-

Conflict of interest: Iris-Tatjana Kolassa is on the editorial advisory board of Open Psychology. However, the article at hand was handled independently by other parties, therefore there was no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Aerts, R., Vanlessen, N., Dujardin, S., Nemery, B., Van Nieuwenhuyse, A., Bauwelinck, M., Casas, L., Demoury, C., Plusquin, M., & Nawrot, T. S. (2022). Residential green space and mental health-related prescription medication sales: An ecological study in Belgium. Environmental Research, 211, 113056. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113056.Search in Google Scholar

Altajar, S. & Moss, A. (2020). Inflammatory bowel disease environmental risk factors: Diet and gut microbiota. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 22, 1–7.10.1007/s11894-020-00794-ySearch in Google Scholar

Amabebe, E., Robert, F. O., Agbalalah, T., & Orubu, E. S. F. (2020). Microbial dysbiosis-induced obesity: Role of gut microbiota in homoeostasis of energy metabolism. British Journal of Nutrition, 123(10), 1127–1137. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520000380.Search in Google Scholar

Ambrose, G., Das, K., Fan, Y., & Ramaswami, A. (2020). Is gardening associated with greater happiness of urban residents? A multi-activity, dynamic assessment in the Twin-Cities region, USA. Landscape and Urban Planning, 198, 103776. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103776.Search in Google Scholar

Antonelli, M., Donelli, D., Barbieri, G., Valussi, M., Maggini, V., & Firenzuoli, F. (2020). Forest volatile organic compounds and their effects on human health: A state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6506. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186506.Search in Google Scholar

Araújo, D., Brymer, E., Brito, H., Withagen, R., & Davids, K. (2019). The empowering variability of affordances of nature: Why do exercisers feel better after performing the same exercise in natural environments than in indoor environments? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.020.Search in Google Scholar

Ascensão, A., Magalhães, J., Soares, J., Oliveira, J., & Duarte, J. A. (2003). Exercise and cardiac oxidative stress. Revista Portuguesa De Cardiologia: Orgao Oficial Da Sociedade Portuguesa De Cardiologia = Portuguese Journal of Cardiology: An Official Journal of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology, 22(5), 651–678.Search in Google Scholar

Asnicar, F. (2021). Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nature Medicine, 27, 29.10.1038/s41591-020-01183-8Search in Google Scholar

Aydin, Y. M., Yaman, B., Koca, H., Dasdemir, O., Kara, M., Altiok, H., Dumanoglu, Y., Bayram, A., Tolunay, D., Odabasi, M., & Elbir, T. (2014). Biogenic volatile organic compound (BVOC) emissions from forested areas in Turkey: Determination of specific emission rates for thirty-one tree species. Science of The Total Environment, 490, 239–253. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.132.Search in Google Scholar

Bach, A., Yáñez-Serrano, A. M., Llusià, J., Filella, I., Maneja, R., & Penuelas, J. (2020). Human breathable air in a Mediterranean forest: Characterization of monoterpene concentrations under the canopy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4391. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124391.Search in Google Scholar

Bach Pagès, A., Peñuelas, J., Clarà, J., Llusià, J., Campillo i López, F., & Maneja, R. (2020). How should forests be characterized in regard to human health? Evidence from existing literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1027. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17031027.Search in Google Scholar

Bamberg, J., Hitchings, R., & Latham, A. (2018). Enriching green exercise research. Landscape and Urban Planning, 178, 270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.06.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bassuk, S., Rifai, N., & Ridker, P. (2004). High-sensitivity C-reactive proteinClinical importance. Current Problems in Cardiology, 29(8), 439–493. doi: 10.1016/S0146-2806(04)00074-X.Search in Google Scholar

Boll, L. M., Khamirchi, R., Alonso, L., Llurba, E., Pozo, Ó. J., Miri, M., & Dadvand, P. (2020). Prenatal greenspace exposure and cord blood cortisol levels: A cross-sectional study in a middle-income country. Environment International, 144, 106047. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106047.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, M. D., Shinn, L. M., Reeser, G., Browning, M., Schwingel, A., Khan, N. A., & Holscher, H. D. (2022). Fecal and soil microbiota composition of gardening and non-gardening families. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1595. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05387-5.Search in Google Scholar

Brzezinski, W. A. (1990). Blood pressure. In H. K. Walker, W. D. Hall, & J. W. Hurst (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed., Chap. 16). Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK268/.Search in Google Scholar

Buss, C., Davis, E. P., Shahbaba, B., Pruessner, J. C., Head, K., & Sandman, C. A. (2012). Maternal cortisol over the course of pregnancy and subsequent child amygdala and hippocampus volumes and affective problems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(20), E1312–E1319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201295109.Search in Google Scholar

Calfapietra, C., Fares, S., Manes, F., Morani, A., Sgrigna, G., & Loreto, F. (2013). Role of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC) emitted by urban trees on ozone concentration in cities: A review. Environmental Pollution, 183, 71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.03.012.Search in Google Scholar

Calogiuri, G., Evensen, K., Weydahl, A., Andersson, K., Patil, G., Ihlebæk, C., & Raanaas, R. K. (2015). Green exercise as a workplace intervention to reduce job stress. Results from a pilot study. Work, 53(1), 99–111. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152219.Search in Google Scholar

Carbone, J. T. (2021). Allostatic load and mental health: A latent class analysis of physiological dysregulation. Stress, 24(4), 394–403. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2020.1813711.Search in Google Scholar

Cesta, M. C., Zippoli, M., Marsiglia, C., Gavioli, E. M., Mantelli, F., Allegretti, M., & Balk, R. A. (2022). The role of interleukin-8 in lung inflammation and injury: Implications for the management of COVID-19 and hyperinflammatory acute respiratory distress syndrome. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 808797. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.808797.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, L., Liu, C., Zou, R., Yang, M., & Zhang, Z. (2016). Experimental examination of effectiveness of vegetation as bio-filter of particulate matters in the urban environment. Environmental Pollution, 208, 198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.09.006.Search in Google Scholar

Cho, K. S., Lim, Y., Lee, K., Lee, J., Lee, J. H., & Lee, I.-S. (2017). Terpenes from forests and human health. Toxicological Research, 33(2), 97–106. doi: 10.5487/TR.2017.33.2.097.Search in Google Scholar

Christian, V. J., Miller, K. R., & Martindale, R. G. (2020). Food insecurity, malnutrition, and the microbiome. Current Nutrition Reports, 9(4), 356–360. doi: 10.1007/s13668-020-00342-0.Search in Google Scholar

Clemente, J. C., Ursell, L. K., Parfrey, L. W., & Knight, R. (2012). The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell, 148(6), 1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035.Search in Google Scholar

Cox, D., Shanahan, D., Hudson, H., Fuller, R., Anderson, K., Hancock, S., & Gaston, K. (2017). Doses of nearby nature simultaneously associated with multiple health benefits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(2), 172. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020172.Search in Google Scholar

De Koning, L., Merchant, A. T., Pogue, J., & Anand, S. S. (2007). Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular events: Meta-regression analysis of prospective studies. European Heart Journal, 28(7), 850–856. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm026.Search in Google Scholar

De Petris, S., Squillacioti, G., Bono, R., & Borgogno-Mondino, E. (2021). Geomatics and epidemiology: Associating oxidative stress and greenness in urban areas. Environmental Research, 197, 110999. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110999.Search in Google Scholar

Donelli, D., Meneguzzo, F., Antonelli, M., Ardissino, D., Niccoli, G., Gronchi, G., Baraldi, R., Neri, L., & Zabini, F. (2023). Effects of plant-emitted monoterpenes on anxiety symptoms: A propensity-matched observational Cohort study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20042773.Search in Google Scholar

Duan, C., Liao, H., Wang, K., & Ren, Y. (2023). The research hotspots and trends of volatile organic compound emissions from anthropogenic and natural sources: A systematic quantitative review. Environmental Research, 216, 114386. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114386.Search in Google Scholar

Dzhambov, A. M., Dimitrova, D. D., & Dimitrakova, E. D. (2014). Association between residential greenness and birth weight: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13(4), 621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2014.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

Dziurkowska, E., & Wesolowski, M. (2021). Cortisol as a biomarker of mental disorder severity. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(21), 5204. doi: 10.3390/jcm10215204.Search in Google Scholar

Egorov, A. I., Griffin, S. M., Converse, R. R., Styles, J. N., Sams, E. A., Wilson, A., Jackson, L. E., & Wade, T. J. (2017). Vegetated land cover near residence is associated with reduced allostatic load and improved biomarkers of neuroendocrine, metabolic and immune functions. Environmental Research, 158, 508–521. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.07.009.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenman, T. S., Churkina, G., Jariwala, S. P., Kumar, P., Lovasi, G. S., Pataki, D. E., Weinberger, K. R., & Whitlow, T. H. (2019). Urban trees, air quality, and asthma: An interdisciplinary review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 187, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.02.010.Search in Google Scholar

Elmarakby, A. A., & Sullivan, J. C. (2012). Relationship between oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines in diabetic nephropathy: Relationship between oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines. Cardiovascular Therapeutics, 30(1), 49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00218.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ewert, A., & Chang, Y. (2018). Levels of nature and stress response. Behavioral Sciences, 8(5), 49. doi: 10.3390/bs8050049.Search in Google Scholar

Firth, J., Gangwisch, J. E., Borsini, A., Wootton, R. E., & Mayer, E. A. (2020). Food and mood: How do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? BMJ, 369, m2382.10.1136/bmj.m2382Search in Google Scholar

Flowers, E. P., Freeman, P., & Gladwell, V. F. (2016). A cross-sectional study examining predictors of visit frequency to local green space and the impact this has on physical activity levels. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 420. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3050-9.Search in Google Scholar

Fröhlich, E. E., Farzi, A., Mayerhofer, R., Reichmann, F., Jačan, A., Wagner, B., Zinser, E., Bordag, N., Magnes, C., Fröhlich, E., Kashofer, K., Gorkiewicz, G., & Holzer, P. (2016). Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: Analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 56, 140–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.020.Search in Google Scholar

Frye, R. E., Cakir, J., Rose, S., Delhey, L., Bennuri, S. C., Tippett, M., Melnyk, S., James, S. J., Palmer, R. F., Austin, C., Curtin, P., & Arora, M. (2021). Prenatal air pollution influences neurodevelopment and behavior in autism spectrum disorder by modulating mitochondrial physiology. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(5), 1561–1577. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00885-2.Search in Google Scholar

Garcia, M. T., Ribeiro, S. M., Germani, A. C. C. G., & Bógus, C. M. (2018). The impact of urban gardens on adequate and healthy food: A systematic review. Public Health Nutrition, 21(2), 416–425. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017002944.Search in Google Scholar

García-Vega, Á. S., Corrales-Agudelo, V., Reyes, A., & Escobar, J. S. (2020). Diet quality, food groups and nutrients associated with the gut microbiota in a Nonwestern population. Nutrients, 12(10), 2938.10.3390/nu12102938Search in Google Scholar

Gladwell, V. F., Brown, D. K., Wood, C., Sandercock, G. R., & Barton, J. L. (2013). The great outdoors: How a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extreme Physiology & Medicine, 2(1), 3. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-3.Search in Google Scholar

Glover, D. A. Stuber, M., & Poland, R. E. (2006). Allostatic load in women with and without PTSD symptoms. Psychiatry, 69(3), 191–203.10.1521/psyc.2006.69.3.191Search in Google Scholar

Godoy, L. D., Rossignoli, M. T., Delfino-Pereira, P., Garcia-Cairasco, N., & de Lima Umeoka, E. H. (2018). A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 127. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127.Search in Google Scholar

Gregis, A., Ghisalberti, C., Sciascia, S., Sottile, F., & Peano, C. (2021). Community garden initiatives addressing health and well-being outcomes: A systematic review of infodemiology aspects, outcomes, and target populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1943. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041943.Search in Google Scholar

Guidi, J., Lucente, M., Sonino, N., & Fava, G. A. (2021). Allostatic load and its impact on health: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(1), 11–27. doi: 10.1159/000510696.Search in Google Scholar

Haahtela, T. (2019). A biodiversity hypothesis. Allergy, 74(8), 1445–1456.10.1111/all.13763Search in Google Scholar

Hanski, I., von Hertzen, L., Fyhrquist, N., Koskinen, K., Torppa, K., Laatikainen, T., Karisola, P., Auvinen, P., Paulin, L., Mäkelä, M. J., Vartiainen, E., Kosunen, T. U., Alenius, H., & Haahtela, T. (2012). Environmental biodiversity, human microbiota, and allergy are interrelated. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(21), 8334–8339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205624109.Search in Google Scholar

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 207–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443.Search in Google Scholar

Hautekiet, P., Saenen, N. D., Aerts, R., Martens, D. S., Roels, H. A., Bijnens, E. M., & Nawrot, T. S. (2022). Higher buccal mtDNA content is associated with residential surrounding green in a panel study of primary school children. Environmental Research, 213, 113551. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113551.Search in Google Scholar

Hazer, M., Formica, M. K., Dieterlen, S., & Morley, C. P. (2018). The relationship between self-reported exposure to greenspace and human stress in Baltimore, MD. Landscape and Urban Planning, 169, 47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.08.006.Search in Google Scholar

He, G., Liu, X., Liu, L., Yu, Y., Chen, C., Huang, J., Lo, K., Huang, Y., & Feng, Y. (2021). A nonlinear association of total cholesterol with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Nutrition & Metabolism, 18(1), 25. doi: 10.1186/s12986-021-00548-1.Search in Google Scholar

Herchet, M., Varadarajan, S., Kolassa, I.-T., & Hofmann, M. (2022). How nature benefits mental health: Empirical evidence, prominent theories, and future directions. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 51(3–4), 223–233. doi: 10.1026/1616-3443/a000674.Search in Google Scholar

Hernandez, D. C., Daundasekara, S. S., Zvolensky, M. J., Reitzel, L. R., Maria, D. S., Alexander, A. C., Kendzor, D. E., & Businelle, M. S. (2020). Urban stress indirectly influences psychological symptoms through its association with distress tolerance and perceived social support among adults experiencing homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5301. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155301.Search in Google Scholar

Hitzler, M., Karabatsiakis, A., & Kolassa, I.-T. (2019). Biomolekulare Vulnerabilitätsfaktoren psychischer Erkrankungen: Einfluss von chronischem und traumatischem Stress auf Immunsystem, freie Radikale und Mitochondrien. Psychotherapeut, 64(4), 329–348. doi: 10.1007/s00278-019-0366-9.Search in Google Scholar

Hofmann, M., Young, C., Binz, T., Baumgartner, M., & Bauer, N. (2017). Contact to nature benefits health: Mixed effectiveness of different mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 31. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010031.Search in Google Scholar

Hoisington, A. J., Billera, D. M., Bates, K. L., Stamper, C. E., Stearns-Yoder, K. A., Lowry, C. A., & Brenner, L. A. (2018). Exploring service dogs for rehabilitation of veterans with PTSD: A microbiome perspective. Rehabilitation Psychology, 63(4), 575–587. doi: 10.1037/rep0000237.Search in Google Scholar

Horn, S. R., Leve, L. D., Levitt, P., & Fisher, P. A. (2019). Childhood adversity, mental health, and oxidative stress: A pilot study. PLoS ONE, 14(4), e0215085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215085.Search in Google Scholar

Hou, B., Nazroo, J., Banks, J., & Marshall, A. (2019). Are cities good for health? A study of the impacts of planned urbanization in China. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(4), 1083–1090. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz031.Search in Google Scholar

Houlden, V., Jani, A., & Hong, A. (2021). Is biodiversity of greenspace important for human health and wellbeing? A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 66, 127385. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127385.Search in Google Scholar

Hsiao, E. Y., McBride, S. W., Hsien, S., Sharon, G., Hyde, E. R., McCue, T., Codelli, J. A., Chow, J., Reisman, S. E., Petrosino, J. F., Patterson, P. H., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2013). Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell, 155(7), 1451–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.024.Search in Google Scholar

Huertas, J. R., Casuso, R. A., Agustín, P. H., & Cogliati, S. (2019). Stay fit, stay young: Mitochondria in movement: The role of exercise in the new mitochondrial paradigm. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2019, 1–18. doi: 10.1155/2019/7058350.Search in Google Scholar

Hunter, M. R., Gillespie, B. W., & Chen, S. Y.-P. (2019). Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 722. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00722.Search in Google Scholar

Islam, H., Hood, D. A., & Gurd, B. J. (2020). Looking beyond PGC-1α: Emerging regulators of exercise-induced skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and their activation by dietary compounds. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition et Metabolisme, 45(1), 11–23. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2019-0069.Search in Google Scholar

Jafari-Vayghan, H., Mirmajidi, S., Mollarasouli, Z., Vahid, F., Saleh-Ghadimi, S., & Dehghan, P. (2023). Mental health is associated with nutrient patterns and Index of Nutritional Quality (INQ) in adolescent girls—An analytical study. Human Nutrition & Metabolism, 31, 200176. doi: 10.1016/j.hnm.2022.200176.Search in Google Scholar

Janssen, B. G., Munters, E., Pieters, N., Smeets, K., Cox, B., Cuypers, A., Fierens, F., Penders, J., Vangronsveld, J., Gyselaers, W., & Nawrot, T. S. (2012). Placental mitochondrial DNA content and particulate air pollution during in Utero life. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(9), 1346–1352. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104458.Search in Google Scholar

Jomard, A., & Osto, E. (2020). High density lipoproteins: Metabolism, function, and therapeutic potential. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 7, 39. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00039.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, R., Tarter, R., & Ross, A. M. (2021). Greenspace interventions, stress and cortisol: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2802. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062802.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, S. L., Dufoix, R., Laplante, D. P., Elgbeili, G., Patel, R., Chakravarty, M. M., King, S., & Pruessner, J. C. (2019). Larger amygdala volume mediates the association between prenatal maternal stress and higher levels of externalizing behaviors: Sex specific effects in project ice storm. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 144. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00144.Search in Google Scholar

Junior, D. P. M., Bueno, C., & Da Silva, C. M. (2022). The effect of urban green spaces on reduction of particulate matter concentration. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 108(6), 1104–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00128-022-03460-3.Search in Google Scholar

Juster, R.-P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002.Search in Google Scholar