Abstract

Chiral molecules hold a mail position in Organic and Biological Chemistry, so pharmaceutical industry needs suitable strategies for drug synthesis. Moreover, Green Chemistry procedures are increasingly required in order to avoid environment deterioration. Catalytic synthesis, in particular organocatalysis, in thus a continuously expanding field. A survey of more recent researches involving chiral imidazolidinones is here presented, with a particular focus on immobilized catalytic systems.

1 Introduction

Chiral molecules do hold a main position as numerous biological functions rely on the recognition between an unsymmetrical system and the correct stereoisomer. On these basis stereoisomers activities in pharmacologically active compounds can be completely different, one providing the highest therapeutic effect while the others being less active, inert or toxic. Despite a substantial quantity of chiral drugs is still sold in the racemic form – i. e. a mixture of enantiomers – the pharmaceutical industry needs to switch to the commercialization of single enantiomers; in fact, in 1992 FDA and in 1994 EU issued guidelines concerning the development of new chiral drugs, which mandate the development of enantiopure compounds [1].

Development of strategies for preparing enantiomerically enriched chiral molecules represents therefore a field of very active research. Synthetic methods based on the use of chiral auxiliaries (chiral enantiomerically pure molecules covalently linked to a reaction partner to control the stereochemical outcome of a reaction and removed once the desired product is obtained) are gradually being abandoned in favor of chiral catalysts, regarded as a fundamental tool in the context of Green Chemistry. Recognizing the progressive deterioration of environment and natural resources, a special commission of the United Nations General Assembly (the World Commission on Environment and Development) released an official report entitled “Our Common Future” stating the concept of sustainable development [2].

Catalytic strategies are included in the twelve Principles of Green Chemistry and are classified according to the kind of application or to the structure of the catalyst, i. e. the molecule that “accelerates a chemical reaction without affecting the position of the equilibrium” on the basis of their aggregation state or their nature and composition [3]. Catalysts, promoting and controlling reaction selectivity, can be metal complexes, enzymes or organocatalysts. Specifically, in 2000 the term organocatalysisorganocatalysis"?> was coined by McMillan to identify reactions where catalysts are “organic compounds which do not contain a metal atom” [4]. Perhaps better described as a process where a metal is not directly involved in the reaction mechanism, so to include also ferrocene-based organocatalysts, organocatalysis is a continuously expanding field in organic chemistry. Relying on the use of relatively small molecules, typically cheap and readily accessible, easy to handle and non-toxic, organocatalysis finds economic- and eco-friendly applications.

While organocatalysts’ biocompatibility was previously mainly hypothesized, a recent study on different cell lines demonstrated these molecules are actually harmless over a wide range of concentrations, the only exception being a thiourea derivative [5]. Despite the high catalyst loading is often considered a requirement limiting organocatalysis organocatalysis"?> viability in industry, the low cost of organocatalysts as well as bypassing the problem of metals removal from final products make this approach nevertheless appealing [6] and highly selective organocatalytic synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds have already been reported and developed in large scale [7].

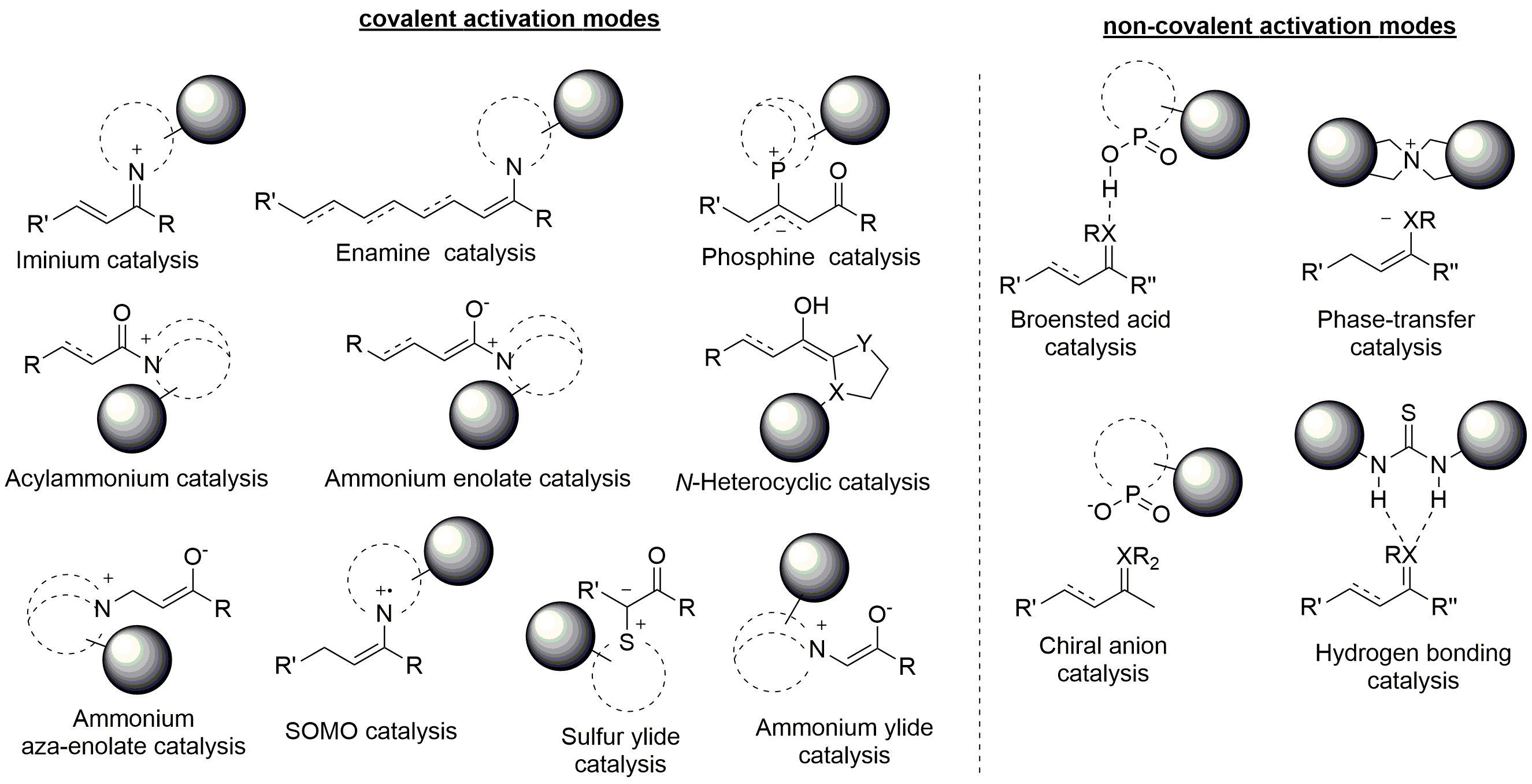

Stereoselective organocatalysis organocatalysis"?> relies on different modes of substrate activation. This can be classified as covalent or non-covalent and further distinguished considering the molecular orbital involved (Figure 1) [8]. It has to be mentioned that the same catalyst can operate through distinct modalities depending on the interacting substrate. Besides, organocatalysts featuring more than one active site, which are simultaneously activating two reaction partners or different positions of the same compound, have been developed and dubbed as multifunctional catalysts.

covalent and non-covalent activation modes of substrate activation

When the energy level of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of the substrate is lowered, nucleophilic attack is favored. Within covalent catalysis, iminium ion, generated upon condensation of a (chiral) primary or secondary amine, is one of the most common intermediate exploited to make the LUMO of α,β–unsaturated compounds more accessible to electrophiles. To achieve carbonyl carbon activation of carboxylic acid derivatives, acylammonium catalysis is instead applied: initiated by the nucleophilicity of an acyltransfer organocatalyst, reactions including transesterifications, kinetic resolutions, desymmetrizations, and Steglich rearrangements have been reported. Activation of the LUMO orbital is also achieved by non-covalent Brønsted acid or hydrogen bonding catalysis, both based on substrate electronic depletion.

On the contrary, increasing of the energy level of the highest occupied molecular orbital enhances the nucleophilicity of the substrate. The most traditional approach is represented by enamine – subsequently extended to di- and trienamine catalysis: parallel to iminium ion mode, the first step of the catalytic cycle consists in the reaction between an amine catalyst and a carbonyl compound, followed by α–deprotonation and generation of an intermediate highly reactive towards electrophilic carbons or heteroatoms. Alternatively, a nucleophilic enolate equivalent (ammonium enolate) can be obtained either by addition of a chiral tertiary amine catalyst to a ketene or through α-deprotonation of an acylammonium intermediate. A different kind of activated nucleophile is the Breslow intermediate; in this case, the α-carbon of an aldehyde acquires an electron rich character upon reaction with carbenes. As for non-covalent catalysis, HOMO activation is achieved via phase-transfer principle.

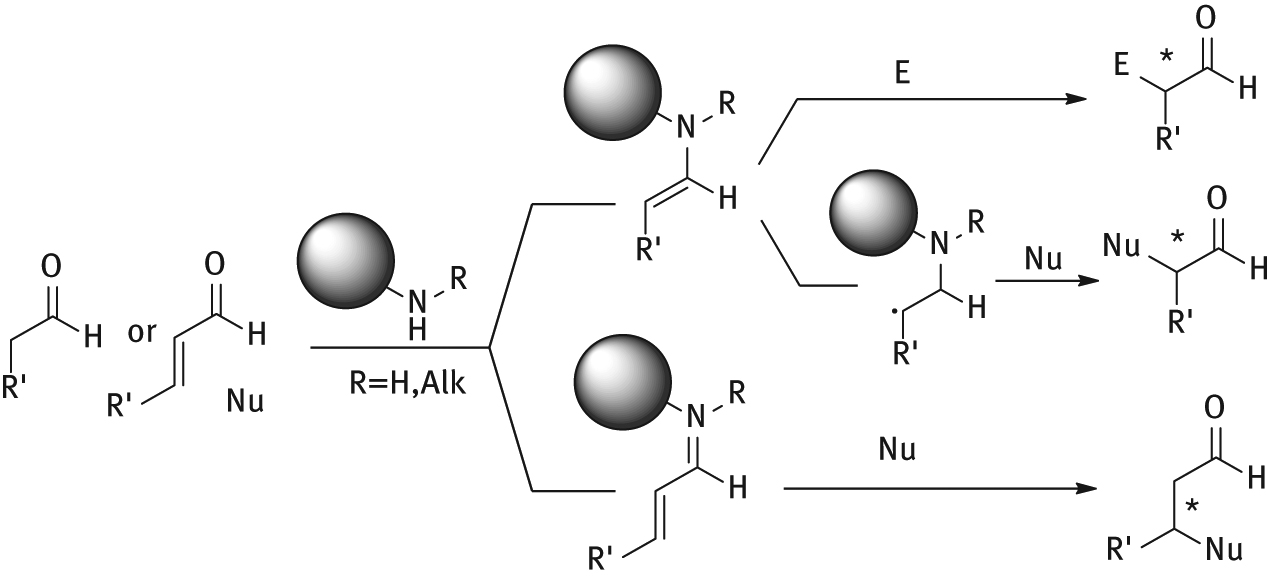

In aminocatalysis [9], three main catalytic mechanisms are operating, based on HOMO (via enamine), LUMO (via iminium-ion) and SOMO activation (Figure 2). Stereoselectivity is given either by steric-shielding, in which one of the reactive intermediate faces is blocked by a bulky group, or by a hydrogen-bonding [10] directed approach, in which both substrate and reagent are simultaneously coordinated. In particular, in enamine-based catalytic processes a carbonyl compound is transformed into a more nucleophilic intermediate. Upon condensation between the catalyst and the substrate, an iminium ion is formed, that tautomerizes to the favored nucleophilic enamine form, in contrast to what happens in the keto-enol equilibrium, mainly lying in the keto-form. The stronger nucleophilic character achieved thanks to the amine activation is not only due to the abundance of the enamine species, but also to the enamine HOMO energy that is higher than that of the corresponding enol, the less electronegative nitrogen lone-pair electrons being higher in energy than that of the more electronegative oxygen. Iminium ion catalysis acts lowering the substrate LUMO energy: when an α,β-carbonyl compound condenses with a chiral secondary amine, it forms a positively charged intermediate prone to electrophilic attack on the β-position. SOMO activation, instead, is based on the in situ generation of single electron species, generated through single electron oxidation of an enamine intermediated or by attack of a radical species.

Operating catalytic mechanisms in aminocatalysis

The field evolved allowing stereoselective functionalization of position that are farther from the carbonyl group, thanks to the vinylogous activation of poly-unsaturated substrates.

2 Imidazolidinones: Iminium ion iminium ion"?> activation

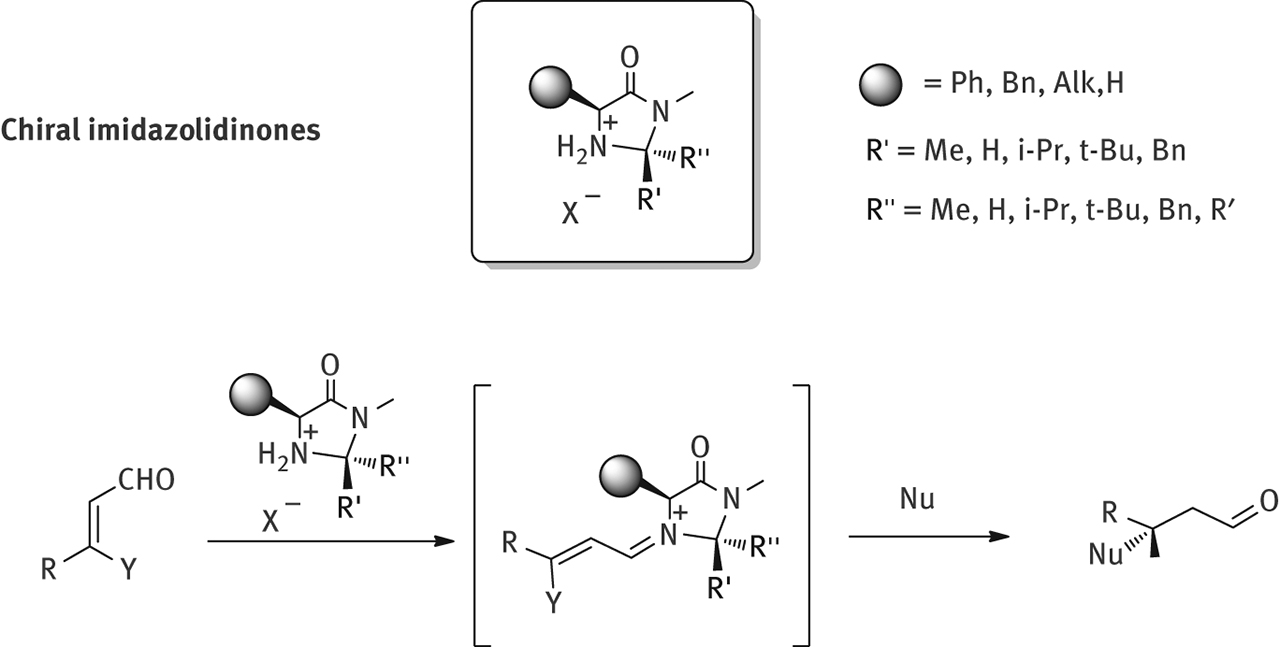

The fundamental work of MacMillan and coworkers with chiral imidazolidinones represents the first example of the iminium ion activation mode and is now considered a landmark in the field of organocatalysis organocatalysis"?> [11]. While usually inactive for enamine-mediated transformations, imidazolidinones have proven to be very versatile catalysts for the activation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes through formation of a transient iminium ion.

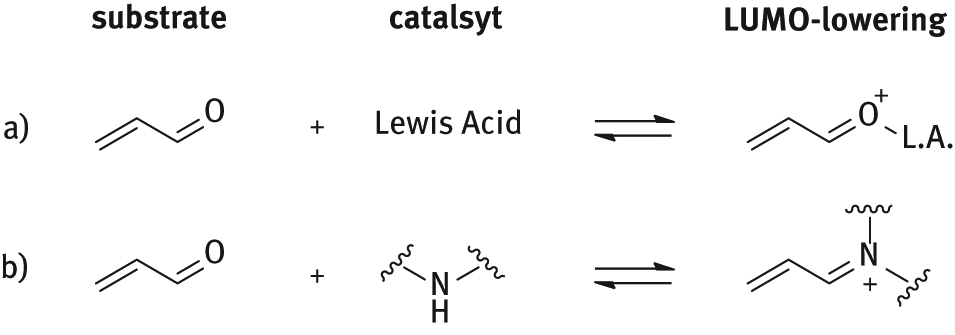

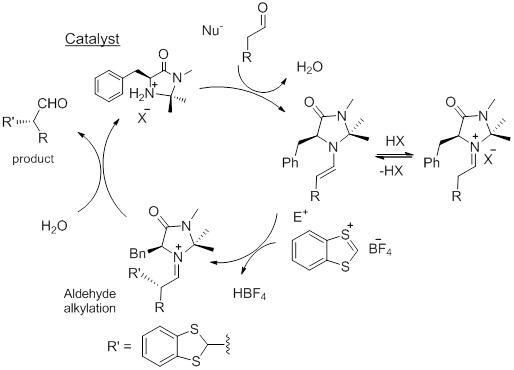

In 2000, the MacMillan research group reported the use of a chiral imidazolidinone derived from natural amino acid L-phenylalanine as organocatalyst to promote Diels-Alder cycloadditions [4]. The catalyst was developed in the context of a general strategy for stereoselective organocatalytic reactions promoted by chiral amines alternatives to Lewis acid catalyzed ones. The reversible formation of iminium ions from α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and amines emulates the equilibrium dynamics and π-orbital electronics that are inherent to Lewis acid catalysis resulting in a LUMO-lowering activation (Figure 3). The iminium ion formation is enhanced by the presence of acid additives so the catalyst operates in its protonated form.

Modes of activation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes.

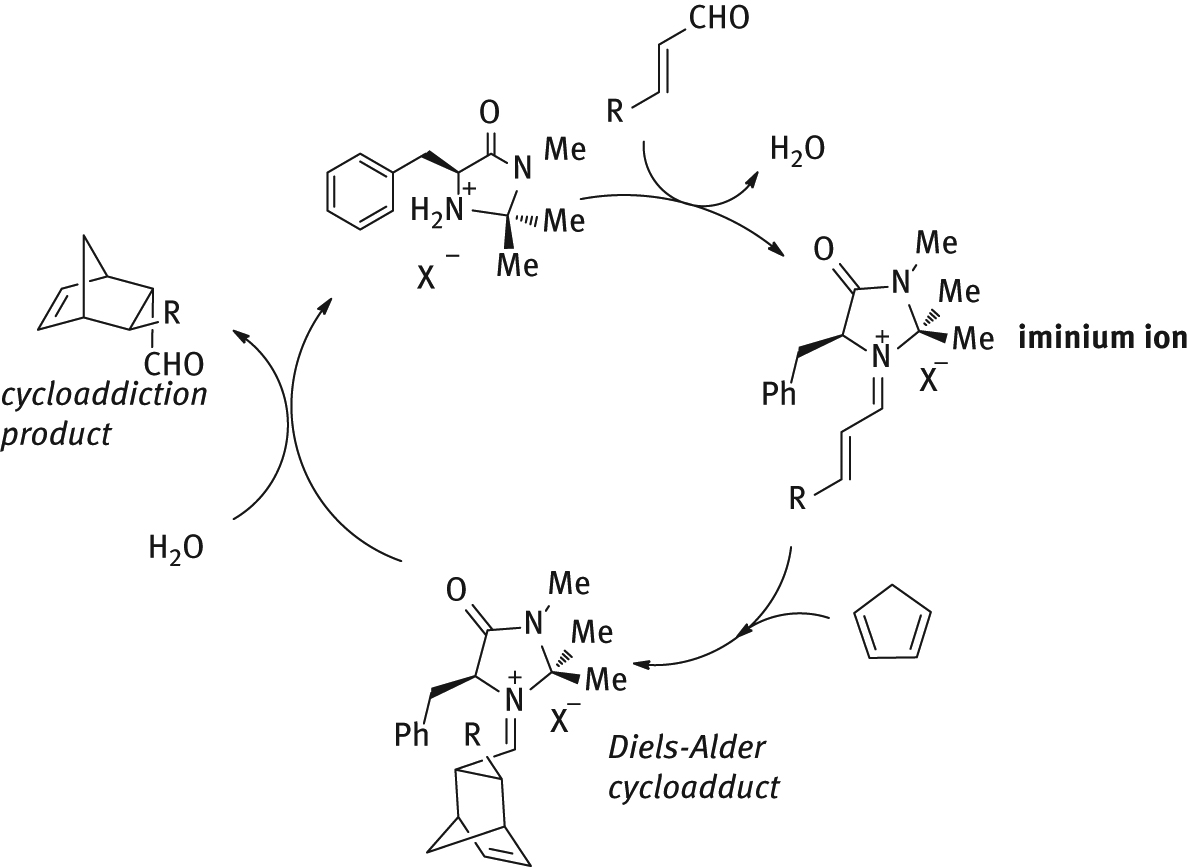

The catalytic cycle for the stereoselective Diels–Alder reaction promoted by MacMillan catalyst is outlined in Figure 4: the condensation of the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde with the enantiopure secondary amine leads to the formation of an iminium ion that is sufficiently activated to engage a diene reaction partner. Accordingly, Diels–Alder cycloaddition would lead to an adduct which upon hydrolysis provides the enantioenriched product, while releasing the chiral amine catalyst.

Reaction mechanism for stereoselective Diels Alder cycloaddition promoted by chiral imidazolidinones.

MacMillan group reported many other asymmetric reactions such as the 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, Friedel-Crafts alkylations, α-chlorinations, α-fluorinations, and intramolecular Michael reactions using chiral imidazolidinones. It was also shown that by combining the organocatalyst and Hantzsch ester it was possible to promote the first enantioselective organocatalytic hydride reduction of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes in what can be defined as a biomimetic approach, somehow analogous to nature’s stereoselective enzymatic transfer hydrogenation with NADH cofactor [12].

A second generation of imidazolidinones-based organocatalysts was developed soon after, to further improve the stereochemical efficiency of the chiral scaffold by exploiting the presence not only of the stereocenter on the aminoacid moiety, but also of an additional stereogenic center on the imidazolidinone scaffold, that offers further possibilities to control the behavior of the catalyst, employed either as trans or cis diastereoisomers, depending on the reactive substrates and the type of transformation (Figure 5). Starting from an amino acid the reaction with an aldehyde or a ketone allows to prepare a high number of compounds, where it is possible to fine tuning the performance of the catalyst and its ability to direct the formation of a well defined conformer in the iminium ion intermediate, key structure for all the stereoselective transformations promoted by this class of catalysts. The reaction of a nucleophile with such intermediate brings to the formation of β–substituted aldehydes, often with very high enantioselectivity.

Stereoselective nucleophile addition to unsaturated aldehydes.

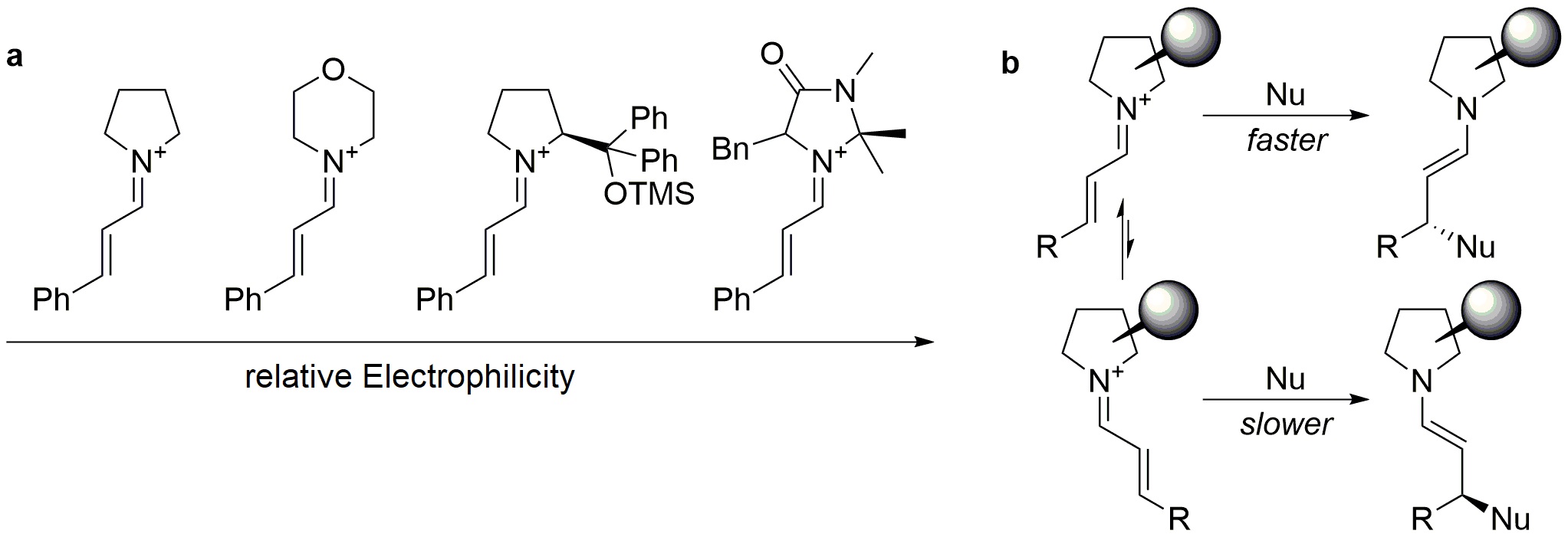

Iminium-ion based catalytic cycle has been the subject of mechanicistic investigation, confirming the importance of a protic additive in assisting a proton transfer that facilitates the formation of the hemiacetal intermediate and of water as proton shuttle for the enamine resulting after C-C bond formation. Moreover, kinetic measurements by Mayr group established an electrophilicity scale for eleven iminium ions obtained from differently structured secondary amines, which revealed dominated by imidazolidinone-based ones (Figure 6) [13]. Rationalization on the stereochemical outcome of the reaction has also been addressed through NMR and theoretical studies. These assessed the conformation of the catalysts, showing that steric shielding has to be ascribed to the benzyl substituent of oxazolidinones. Additionally, the configuration of the iminium ion intermediate was elucidated being in an E/Z ratio > 9:1, the higher level of enantioselection justified by a kinetic resolution process operated by the nucleophile itself [14].

electrophilicity scale for iminium ions

Such organocatalysts have found later wide application in the so called SOMO catalysis (Single Occupied Molecular Orbital), where the chiral imidazolidinone is employed in combination with a photoredox catalyst to promote radical stereoselective reactions, and the organocatalytic cycle is interlocked with the photoredox catalytic cycle. However, since a whole chapter of the book is devoted to organo-photoredox catalysis, the topic will not be discussed in the present chapter.

3 Chiral imidazolidinones imidazolidinones"?> : Other activation modes

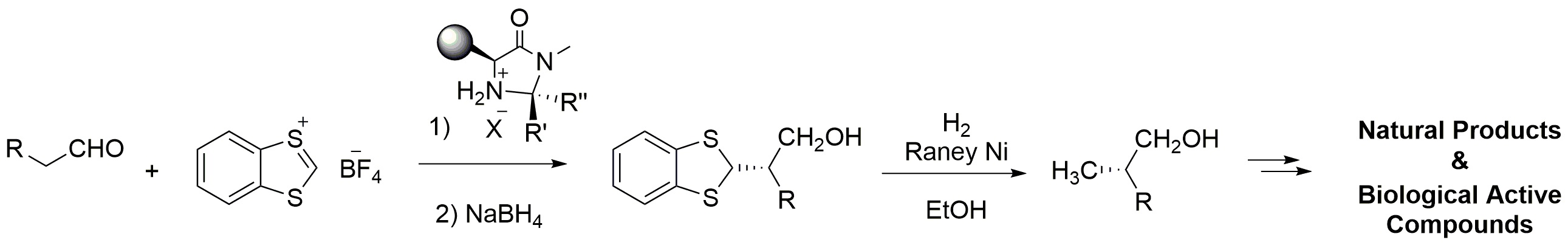

3.1 Stereoselective alkylation of aldehydes

Metal-free synthetic α-alkylation methodologies of aldehydes have been developed by SN1-type reactions, in which carbocations of sufficient stability generated in situ from alcohols, or stable carbenium ions, are employed to perform enantioselective α-alkylation of aldehydes (Figure 7) catalyzed by MacMillan-type catalysts, according to the mechanism reported in Figure 8 [15]. Differently from the previous cases, the organocatalyst is here employed to activate the alfa position of the carbonyl derivative as enamine that reacts with the electrophilic species to afford α-substituted enantiomerically enriched aldehydes.

Stereoselective alkylation of aldehydes.

Reaction mechanism for the stereoselective alkylation of aldehydes promoted by chiral imidazolidinone.

High yields and remarkable enantioselectivities, often higher than 90% e.e. were obtained with linear and not branched aldehydes. Enantiomerically pure α–alkyl-substituted aldehydes are remarkably important key substrates for the synthesis of more complex molecules [16].

3.2 Stereoselective imine reduction

Despite all the recent achievements in the field of enantioselective organocatalytic reduction of C=N double bonds, the combination of inexpensive, non-toxic, easily disposable reagents with very low catalyst loadings, comparable to those of the metal-based chiral catalysts, is an unmet challenge in organocatalysis organocatalysis"?> today [17].

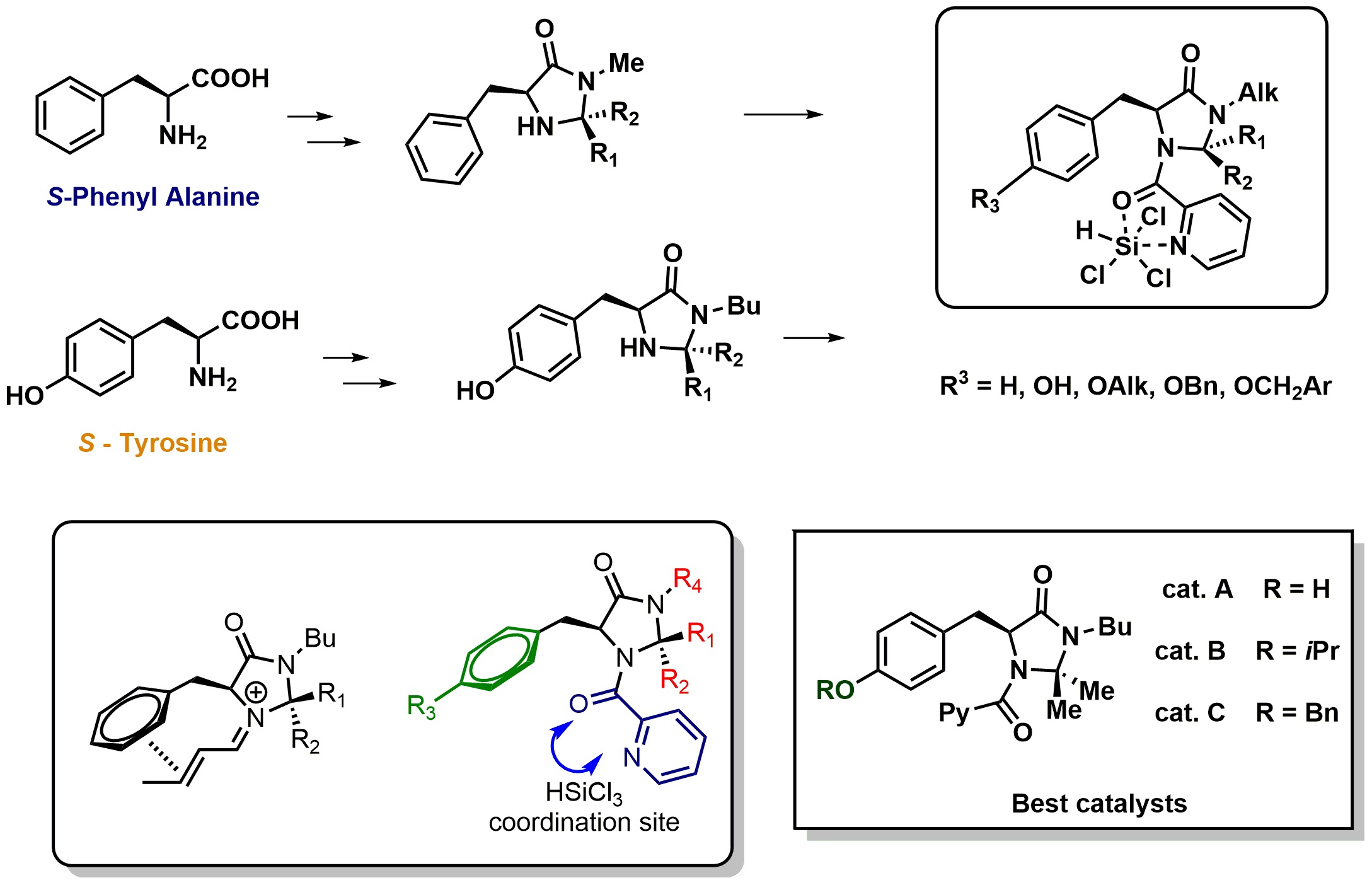

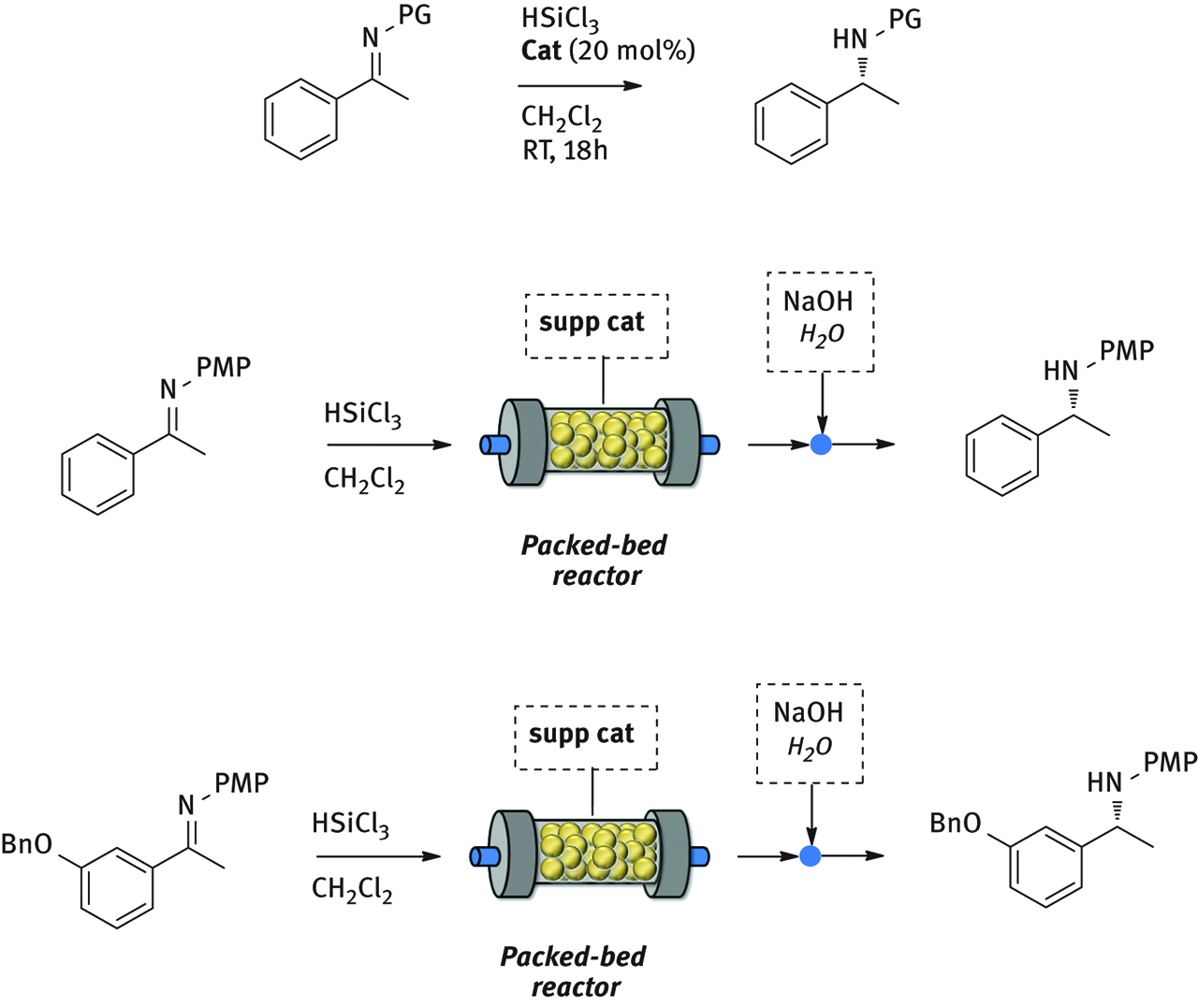

Trichlorosilane-based reduction methodology may offer this opportunity. Recently the design, the synthesis, the optimization, and the application of a new class of easy accessible chiral Lewis bases, prepared with few steps starting from cheap and commercially available aminoacids, have been reported (Figure 9) [18]. Picolinamides, that could be easily obtained by condensation between picolinic acid/chloride/anhydride with different chiral scaffolds, have been extensively studied as activators of trichlorosilane [19]. The inspiration, for the design of this new class of LB*, was taken by the well-established and efficient scaffold of imidazolidinones, able to successfully control the stereochemical outcome of the reaction of carbonyl compounds. The picolinamide residue is responsible of HSiCl3 coordination and chemical activation, while the imidazolidinone scaffold offers many opportunities to tune and modify the steric hindrance and the stereoelectronic properties of the catalytic system.

Chiral Lewis bases for enantioselective catalytic hydrosilylation of imines.

A series of new chemical entities, featuring different substituents on the imidazolidinone ring and on the aromatic ring of the amino acid moiety, were synthesized. Surprisingly the introduction of a para substituent on the aromatic ring leads to the identification of very efficient catalysts. A-C showed very high activity and incredible stereocontrol, ee up to 98% in the enantioselective reduction of ketoimines. In the model reduction of N-PMP imine of acetophenone, with catalyst C the product was obtained with 80% of yield and 97% of ee, using only 0.1% mol of catalyst. Working under such conditions, the ACE (Asymmetric Catalyst Efficiency) [20] was evaluated to be 375–400, a comparable value with organometallic systems and better then most organocatalysts [21].

To test the general applicability of the new catalysts the reduction of a wide variety of imines was investigated. The reduction of 3-alkoxy-substituted acetophenone imines, either N-benzyl protected (as precursor of primary amine derivatives), or N-(3-phenylpropyl) substituted, represents a practical and efficient entry to the synthesis of enantiomerically pure valuable pharmaceutical compounds, used in the treatment of Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases, hyperparathyroidism, neuropathic pains and neurological disorders (Figure 10).

Chiral amines as valuable pharmaceutically active compounds.

4 Immobilized imidazolidinonesimidazolidinones"?>

Given its popularity, due to wide applicability and easy availability, it is not surprisingly that the catalyst has been covalently anchored onto different supports [22]. The immobilization of a catalytic species on a solid support may represent a solution to some of the problems related to the use of chiral catalysts in organic synthesis [23]. Not only the recovery and the possible recycle of a catalyst may be investigated and successfully realized through its immobilization, but also the studies of other issues like the stability, the structural characterization and the catalytic behavior may be better conducted on a supported version of the enantioselective catalyst.

These general considerations are true also for organic catalysts. Even if the transformation of a stoichiometric into a catalytic process can be regarded as a significant step toward the development of a truly green chemistry, catalytic reactions are amenable to a variety of improvements that can make them greener and greener. Among these, the replacement of metal-based catalysts with equally efficient metal-free counterparts, the so-called “organic catalysts”, can be extremely important.

The immobilization of the catalyst on a support with the aim of facilitating the separation of the product from the catalyst, and thus the recovery and recycling of the latter, can also be regarded as an important improvement for a catalytic process [24]. In this line, the immobilization of organic catalysts seems particularly attractive, because the metal-free nature of these compounds avoids from the outset the problem of the leaching of the metal that often negatively affects and practically prevents the efficient recycling of a supported organometallic catalyst [25].

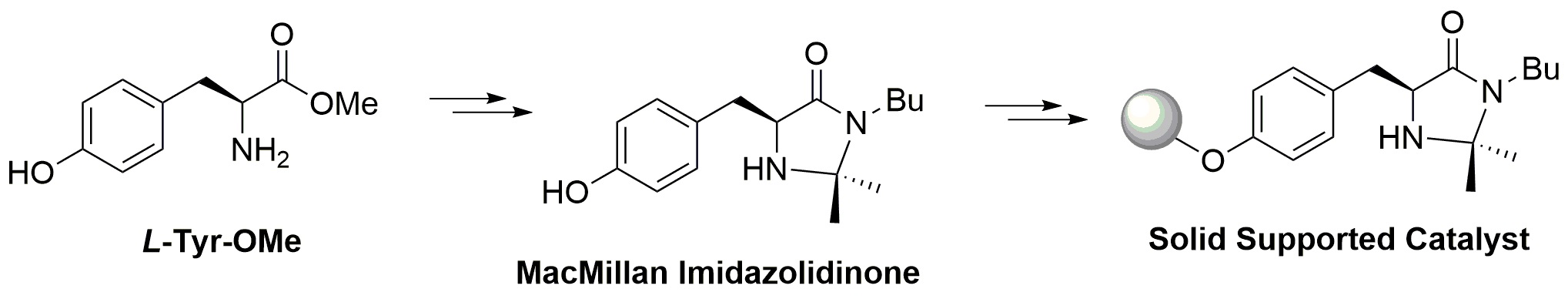

Despite the great number of proposed solutions, the development of a supported chiral imidazolidinone for the application in catalytic flow reactor was not reported until 2013, when the use of chiral imidazolidinones supported on mesoporous silica nanoparticles to build catalytic reactors was investigated (Figure 11) [26].

Immobilization of chiral imidazolidinones.

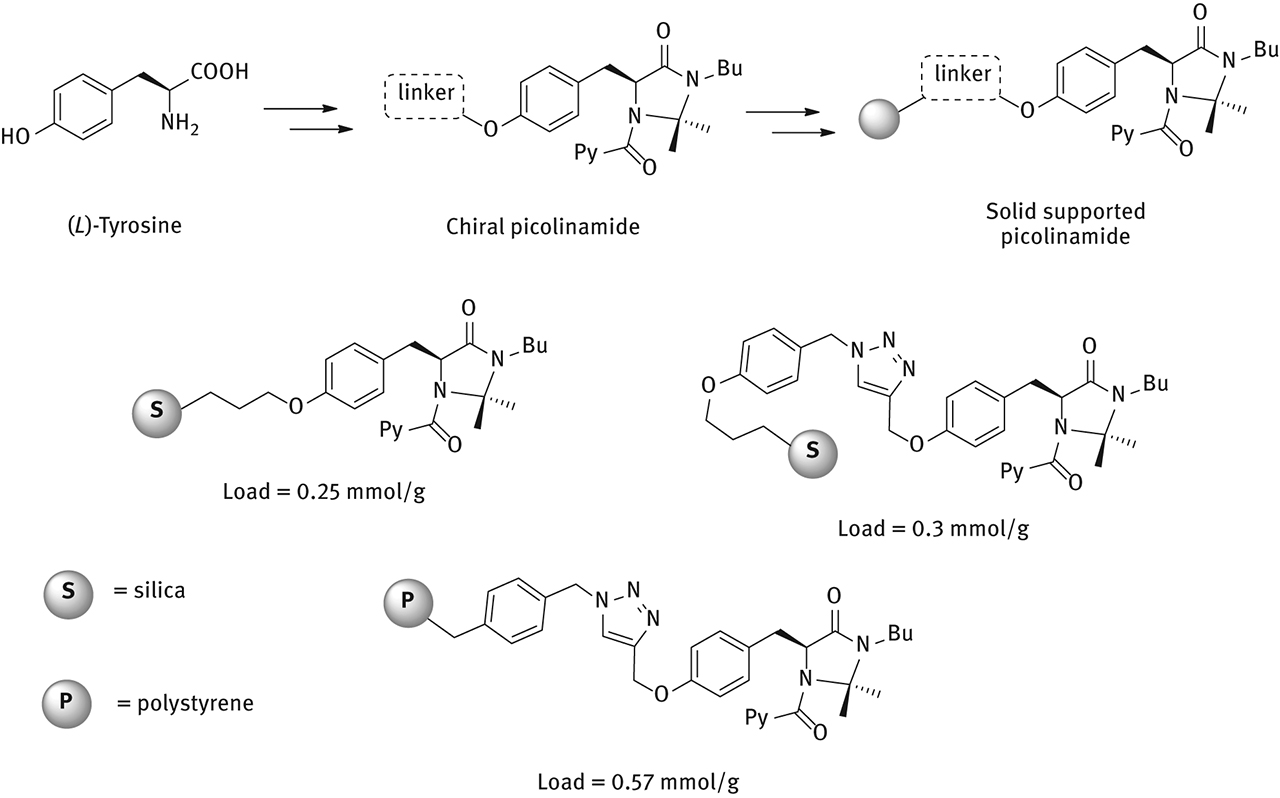

Later, the use of two supporting materials with different properties, inorganic silica and organic polystyrene was compared [27]. The silica supported catalysts were prepared by grafting on silica particles of different size. In order to evaluate the influence of the linker on catalyst performances, a different anchoring strategy was evaluated: the supported catalyst was synthesized through a click reaction between azido-functionalized silica and imidazolidinone in the presence of CuI as catalysts and Hunig’s base in chloroform as solvent. Catalyst with the triazole ring as spacer was obtained (Figure 12).

Synthesis and use of silica and polystyrene-supported catalysts.

Silica-grafted catalysts promoted the model Diels Alder cycloaddition between cyclopentadiene and cinnamic aldehyde in good yields and ee up to 82%, while the material which features a triazole linker on its structure, promoted the reaction in good yields and very good ee, up to 93%. This suggests that a longer linker between the solid support and the catalytically active site positively influences the enantioselectivity of the process.

The solid supported catalysts could be easily recovered after reaction time by simple filtration of the crude mixture. However, attempts to recycle the catalysts were unsuccessful, thus suggesting that the organic catalyst supported onto silica is deactivated under reaction conditions (probably the presence of the acid co-catalyst accelerates the degradation of the imidazolidinone ring).

The use of packed-bed flow reactors was then investigated. As catalytic reactor, an empty HPLC column (l: 12.5 cm, id: 0.4 cm, V: 1.57 mL) containing 1 g of silica-supported catalyst was employed. The void volume was determined experimentally for each reactor and it was necessary to calculate the residence time. The model cycloaddition between cyclopentadiene and cinnamaldehyde was studied. The reagents were pumped in the reactor by a syringe pump and the products were collected at the way out of the reactor. The catalytic reactor containing showed a good activity in terms of chemical yields and enantioselectivity (up to 85%). By using both TFA and HBF4 as co-catalysts the flow system produced cycloadducts for more than 150 h, demonstrating that the flow process could extend catalyst lifetime and reduce the imidazolidinone deactivation observed in batch [28]. Trifluoroacetate salt of the supported imidazolidinones promoted a faster reaction than its tetrafluoroborate counterpart.

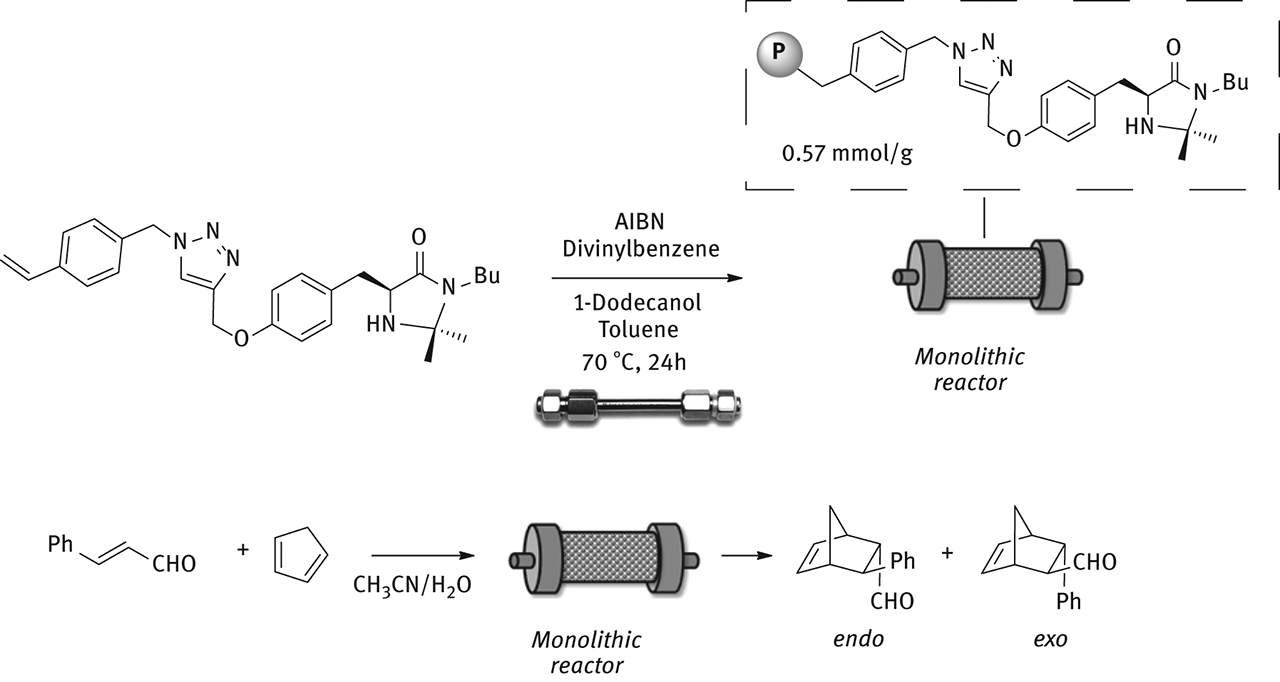

The synthesis of polymer-supported catalysts involved a click reaction between imidazolidinone and 1-(azidomethyl)-4-vinylbenzene in the presence of CuI and Hunig’s base. Resulting intermediate was subjected to radical copolymerization with divinylbenzene as co-monomer in the presence of toluene and 1-dodecanol as porogens and AIBN as initiator. Polystyrene-supported catalyst was obtained with a loading of 0.57 mmol/g that was determined by the stoichiometry of the polymerization reaction. In the benchmark cycloaddition under the same experimental conditions employed for silica-supported catalysts, the cycloadducts were obtained in very good yields and excellent ee, up to 90%. Notably, when the catalyst was recycled, it maintained a good level of chemical activity and a very good enantioselectivity

The results indicate that polystyrene as supporting material is better than silica. This is probably due to the a polar nature of the organic polymer compared to silica that presents Si-OH groups on his surface that can interfere with the activity of the supported catalyst.

A packed bed reactor containing polystyrene-anchored imidazolidinone was then prepared. As flow reactor an HPLC column (l: 6 cm, id: 0.4 cm, V: 0.75 mL) filled with 0.3 g of supported catalyst was employed. The system was used for the enantioselective cycloadditions of cyclopentadiene and three different aldehydes. For the first 24 h product was formed in 75% yield and 91% and 92% ee for endo and exo isomers, respectively. The catalytic reactor operated for 150 h with no appreciable loss in chemical or stereochemical activity.

Although the flow system proved to be stable for a long period of time, a major limitation was related to the low flow rate employed (2 μL/min). The flow reactor was not suitable for operation at high flow rates, as these prevented the supported catalyst to have sufficient contact time with the reagents.

To overcome this problem the use of monolithic reactors was explored [29]. As already reported above, these reactors feature a large surface area and can be employed at high flow rates. Monolithic reactor was prepared inside a HPLC column (l: 6 cm, id: 0.4 cm, V: 0.75 mL) by radical copolymerization of the chiral monomer featuring the imidazolidinone moiety with divinylbenzene as co-monomer, in the presence of toluene and 1-dodecanol as porogens and AIBN as initiator (Figure 13).

Synthesis of monolithic reactor.

The reactor was sealed and heated at 70 °C for 24 h. The reactor was then washed with THF in order to remove excess of porogens. The void volume was determined experimentally and it was necessary to calculate the residence time. Monolithic reactor was tested in the model cycloaddition between cyclopentadiene and cinnamaldehyde in the presence of HBF4 as co-catalyst. Differently from packed bed reactors, the monolithic reactor could work at high flow rates with no appreciable loss in chemical or stereochemical activity. After 70 h of continuous operation the desired cycloadducts were produced in 73% yield and 88% ee.

Comparing the Turn Over Numbers (TON) and productivities (calculated as 1000* mmol product*mmol catalyst−1 * time−1) for the three different flow systems (silica packed bed, polystyrene packed bed and polystyrene monolith reactors), the monolithic reactor proved to be much more efficient in terms of TONs and productivity than packed bed reactors, especially for longer reaction times. Differently from packed bed reactors, the monolithic reactor could work at high flow rates with no appreciable loss in chemical or stereochemical activity (after 24 h, 75% yield and 92% ee, after 44 h 68% yield and 90% ee). After 70 h of continuous operation the desired cycloadducts were produced in 73% yield and 88% ee with a residence time of 1.2 hours (entry 5).

To further demonstrate the advantages related to the use of monolithic reactors with respect to packed bed-ones a comparison of TON and productivities (calculated as 1000* mmol product*mmol catalyst−1 * time−1) obtained with three different flow systems was made. The productivity was determined to be 64 h−1 for the silica-based packed bed reactor, 120 h−1 for the polystyrene-based packed bed reactor and 339 h−1 for the monolithic reactor.

The greater performances are ensured by the possibility to work at higher flow rates with no erosion in the chemical or stereochemical activity. Thus in the same unit of time, larger quantities of product can be obtained.

In order to develop a continuous flow process with the catalytic reactors previously described, the alkylation of propanal with three different cationic electrophiles (I, II and III) [15], was first studied in batch, in the presence of 30 mol% of supported imidazolidinones, HBF4 as co-catalysts, NaH2PO4 as scavenger (of HBF4 released from the electrophile) and CH3CN/H2O mixture as solvent (Figure 14) on two different supports, silica and polystyrene [30].

Alkylation of propanal with different cationic electrophiles.

Products were obtained in good yields and fair to very good enantioselectivity. For example, reaction of propionic aldehyde with electrophile I afforded the product in 75% yield and 90% ee with silica-supported catalyst, and 67% yield and 86% ee with PS-supported system. However, with electrophiles II and III polymer supported imidazolidinone promoted the reactions with higher enantioselectivity compared to silica supported, affording the products in 90% ee with cation II (compared to 79% ee with silica-immobilized species) and in 95% ee with cation III (compared to 67% ee with silica-immobilized catalyst).

Once the compatibility of supported catalysts in the batch reaction was demonstrated the use of packed-bed reactors for the continuous flow alkylation of aldehydes was studied. Two stainless-steel HPLC columns (l: 6 cm, id: 0.4 cm, V: 0.75 mL) were filled with polymer (0.3 g) and silica (0.3 g) supported catalysts, respectively. The alkylation of propanal with I in the packed bed reactor containing silica-support imidazolidinone afforded the product in 65% yield and 80% ee. Packed-bed reactor containing the polystyrene-immobilized catalyst promoted the reaction in moderate yield and very good ee (up to 95%).

The flow systems prepared showed a good activity in the stereoselective alkylation of aldehydes, affording the desired products in very good ee (up to 95%) and high productivities. However when high flow rates were employed quite low yields were obtained. Even if some improvements are still required, this procedure represent the first continuous flow stereoselective alkylation of aldehydes using solid supported imidazolidinones.

The stereoselective reduction of imines with HSiCl3 using picolinamides with a chiral imidazolidinone as scaffold has been recently reported [18]. Starting from (L)-Tyrosine, a chiral picolinamide was prepared and the phenolic residue exploited as an handle to anchor the catalyst onto a solid support (Figure 15) [31].

Synthesis of immobilized imidazolidinones-based chiral picolinamides for enantioselective reduction of imines.

Silica supported picolinamides were prepared by grafting commercially available SiO2 (Apex Prepsil Silica Media 8 µm); the loading was determined by weight difference. Another silica supported picolinamide which features a longer linker longer between the active site and the solid support was synthesized by a click reaction.

The synthetic strategy for the preparation of polymer supported picolinamide involved the preparation of the chiral monomer that was then polymerized with divinylbenzene as co-monomer, in the presence of toluene and 1-dodecanol as porogens and AIBN as initiator. The loading was determined by the stoichiometry of the polymerization reaction.

The reduction of imines derived from acetophenone with trichlorosilane was chosen as model reaction to test the solid supported picolinamides (Figure 16).

In batch and in flow enantioselective organocatalytic reductions of imines.

Silica-supported catalyst promoted the reaction in excellent yield and very good ee. The presence of a longer linker in the structure of catalyst did not improve neither the yield nor the stereoselectivity of the process. However, polystyrene supported picolinamide proved to be the best catalytic system, affording the desired products in very good yields and excellent ee (97%).

On the basis of these preliminary results, the amount of the polymer-supported catalyst could be reduced to 1 mol% without any loss in the chemical or stereochemical activity. When the reaction time was reduced to 4 h, a loading of 5 mol% of immobilized catalyst gave the chiral amine in 82% yield and 94% ee. The methodology showed a wide reaction scope.

In order to demonstrate the practical applicability of the supported catalyst, the recycle was studied. When recycling experiments were conducted for 18 h for each cycle, amine was obtained as racemic mixture already at the second run. It was necessary to reduce reaction time to 2 h to maintain a high level of stereoselectivity. Under these conditions, it was possible to run four reaction cycles without any loss in the chemical or stereochemical activity of the process (ee up to 95%). In the fifth cycle, the product was obtained in very low yield and reduced ee. At the sixth cycle the catalysts was completely deactivated.

Polystyrene supported catalyst was then employed for the preparation of packed bed reactors for the continuous flow reduction of imines with HSiCl3. A 0.05 M solution of imine and HSiCl3 in CH2Cl2 was pumped into the reactor through a syringe pump at 0.4 mL/h (res time: 1 h) at room temperature. The outcome of the reactor was collected into a flask containing NaOH 10% solution. After phase separation and concentration the product was isolated. Every hour the product was collected and analyzed in order to determine the conversion and the ee as a function of time.

The flow system was stable for 7 h, producing the expected chiral amine in excellent yield and very good ee (up to 91% ee). The stereoselectivity of the process slightly decreased with time, probably because of a partial decomposition of the catalyst.

Finally the continuous flow synthesis of chiral precursor of Rivastigamine was performed. The continuous flow process, afforded the desired product in 82% yield and 83% ee for the first 2.5 h. Then the product was continuously produced for additional 3 h in 79% yield and 74% ee.

5 Conclusion and perspectives

Since their introduction in asymmetric catalysis, chiral imidazolidinones have shown to be one of the most successful class of organocatalysts. Their popularity is due to many positive features:

they are highly tunable in different positions of the scaffold, thus modifying the behavior of the catalyst playing either with electronic or steric effects

they are easy to synthesize by a few steps short reaction sequence

they are reasonable cheap catalysts, since they are derived by readily available, enantiopure starting materials such alfa-aminoacids

they are quite stable and can be stored as salts for long time

in aminocatalysis they can be used to activate carbonyl derivatives both through iminium ion catalysis (preferred) and by enamines activation (less frequently)

chiral imidazolidinones have found widespread use also in stereoselective organophoto-redox catalysis, opening the way to the development of unprecedented reactions

imidazolidinone structure has been employed also as chiral platform to build novel metal-free catalysts to be used in fields other than aminocatalysis.

All these advantages well explain the great popularity of this family of organocatalysts, which have been also immobilized on different solid supports in order to develop a recyclable version of the chiral catalyst. The use of solid supported imidazolidinones in packed or monolithic reactors opened the avenue to the development of in-flow reactions, for the synthesis also of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) or advanced intermediates [32].

Chiral imidazolidinones can be considered without doubt “privileged ligands” [33] and even more, novel applications in asymmetric catalysis can be envisaged in the future.

References

[1] Kasprzyk-Hordern B. Pharmacologically active compounds in the environment and their chirality. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:4466–503 and references therein.10.1039/c000408cSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, United Nations (UN) Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission), 1987, Published as Annex to General Assembly document A/42/427, Development and International Cooperation: Environment, August 1987.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Shaikh IR. Organocatalysis: key trends in green synthetic chemistry, challenges, scope towards heterogenization, and importance from research and industrial point of view. J Catal. 2014:2014. Article ID 402860. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/402860.10.1155/2014/402860Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Ahrendt KA, Borths CJ, MacMillan DW. New strategies for organic catalysis: the first highly enantioselective organocatalytic Diels−Alder reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4243–4.10.1021/ja000092sSuche in Google Scholar

[5] Nachtergael A, Coulembier O, Dubois P, Helvenstein M, Duez P, Blankert B, et al. Organocatalysis paradigm revisited: are metal-free catalysts really harmless? Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:507–14.10.1021/bm5015443Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] MacMillan DW. The advent and development of organocatalysis. Nature. 2008;455:304–8.10.1038/nature07367Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Howell GP. Asymmetric and diastereoselective conjugate addition reactions: C–C bond formation at large scale. Org Process Res Dev. 2012;16:1258–72.10.1021/op200381wSuche in Google Scholar

[8] Abbasov ME, Romo D. The ever-expanding role of asymmetric covalent organocatalysis in scalable, natural product synthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1318–27.10.1039/C4NP00025KSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] a) Denmark SE, Beutner GL Lewis base catalysis in organic synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2008, 47, 1560–638; b) Melchiorre P, Marigo M, Carlone A, Bartoli C. Asymmetric aminocatalysis – gold rush in organic chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6138–71; c) Nielsen M, Worgull D, Zweifel T, Gschwend B, Bertelsen S, Jørgensen KA. Mechanisms in aminocatalysis. Chem M Commun. 2011:632–49.10.1002/anie.200604943Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] For a recent summary on recent progress in the field of hydrogen-bonding aminocatalysis XE “aminocatalysis” using proline-derived systems see Albrecht L, Jiang H, Jørgensen KA. Hydrogen-bonding in aminocatalysis: from proline and beyond. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:358–68.10.1002/chem.201303982Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Lelais G, MacMillan DW. Modern strategies in organic catalysis: the advent and development of iminium activation. Aldrichimica Acta. 2006;39:79–87.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Selected papers: a) Paras NA, MacMillan DW New strategies in organocatalysis: the first enantioselective organocatalytic Friedel-Crafts alkylation, J Am Chem Soc 2001, 123, 4370–1; b) Brochu MP, Brown AP, MacMillan DW. Direct and enantioselective organocatalytic α-chlorination of aldehydes. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4108–409; c) Lee S, MacMillan DW. Organocatalytic vinyl and Friedel-Crafts alkylations with trifluoroborate salts. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15438–39; d) Fonseca MT, List B. Catalytic asymmetric intramolecular Michael reaction of aldehydes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3958–60; e) Ouellet SG, Tuttle JB, MacMillan DW. Enantioselective organocatalytic hydride reduction. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:32–3.10.1021/ja015717gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Lakhdar S, Tokuyasu T, Mayr H. Electrophilic reactivities of alpha,beta-unsaturated iminium ions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8723.10.1002/anie.200802889Suche in Google Scholar

[14] See ref. 6 and also: Seebach D, Gilmour R, Groselj U, Deniau G, Sparr C, Mo E, et al. Stereochemical models for discussing additions to α,β-unsaturated aldehydes organocatalyzed by diarylprolinol or imidazolidinone derivatives – Is there an (E)/(Z)-dilemma? Helv Chim Acta. 2010;93:603–34.10.1002/hlca.201000069Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Cozzi PG, Benfatti F, Zoli L. Organocatalytic asymmetric alkylation of aldehydes by S(N)1-type reaction of alcohols. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1313.10.1002/anie.200805423Suche in Google Scholar

[16] a) Wakabayashi T, Mori K, Kobayashi S Total synthesis and structural elucidation of Khafrefungin. J Am Chem Soc 2001, 123, 1372; b) Fürstner A, Bonnekessel M, Blank JT, Radkowski K, Seidel G, Lacombe F, Gabor B, Mynott R. Total Synthesis of Myxovirescin A1. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:8762.10.1021/ja0057272Suche in Google Scholar

[17] For a review on low-loading chiral organocatalysts see: Giacalone F, Gruttadauria M, Agrigento P, Noto R. Low loading asymmetric organocatalysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2406–47.10.1039/C1CS15206HSuche in Google Scholar

[18] Brenna D, Porta R, Massolo E, Raimondi L, Benaglia M. A new class of low-loading catalysts for a highly enantioselective, metal-free imine reduction of wide general applicability. ChemCatChem. 2017;9:941–5.10.1002/cctc.201700052Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Review: Rossi S, Benaglia M, Massolo E, Raimondi L. Organocatalytic strategies for enantioselective metal-free reduction. Catal Sci Technol. 2014;9:2708–23.10.1039/C4CY00033ASuche in Google Scholar

[20] The definition of ACE was recently proposed in the attempt to compare and evaluate the efficiency of different catalysts, considering the level of enantioselectivity and the yield guaranteed by the catalyst, the molecular weight of the product and of the catalysts itself. See: El-Fayyoumy S, Todd MH, Richards CJ. Can we measure catalyst efficiency in asymmetric chemical reactions? A theoretical approach. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2009;5:67.10.3762/bjoc.5.67Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Jones S, Warner CJ. Trichlorosilane mediated asymmetric reductions of the CN bond. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:2189–200.10.1039/c2ob06854kSuche in Google Scholar

[22] a) Benaglia M, Celentano G, Cinquini M, Puglisi A, Cozzi F Poly(ethylene glycol)-supported chiral imidazolidin-4-one: an efficient organic catalyst for the enantioselective diels-alder cycloaddition. Adv Synth Catal 2002, 344, 149–52; b) Selkälä SA,Tois J, Pihko P-M, Koskinen AM. Asymmetric organocatalytic Diels-Alder reactions on solid support. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:941; c) Zhang Y, Zhao L, Lee SS, Ying JY. Enantioselective catalysis over chiral imidazolidin-4-one immobilized on siliceous and polymer-coated mesocellular foams. Adv Synth Catal. 2006;348:2027; d) Hagiwara H, Kuroda T, Hoshi T, Suzuki T. Immobilization of MacMillan imidazolidinone as Mac-SILC and its catalytic performance on sustainable enantioselective Diels–Alder cycloaddition. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:909; e) Shi JY, Wang CA, Li ZJ, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Wang W. Heterogeneous organocatalysis at work: functionalization of hollow periodic mesoporous organosilica spheres with MacMillan catalyst. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:6206; f) Guizzetti S, Benaglia M, Siegel JS. Poly(methylhydrosiloxane)-supported chiral imidazolinones: new versatile, highly efficient and recyclable organocatalysts for stereoselective Diels-Alder cycloaddition reactions. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3188–90; g) Riente P, Yadav J, Pericas MA. click strategy for the immobilization of Macmillan organocatalysts onto polymers and magnetic nanoparticles. Org Lett. 2012;14:3668.10.1002/1615-4169(200202)344:2<149::AID-ADSC149>3.0.CO;2-USuche in Google Scholar

[23] a) Trindade F, Gois PM, Afonso CA Recyclable stereoselective catalysts. Chem Rev 2009, 109, 418–514; b) Benaglia M. Recoverable and recyclable catalysts. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2009; c) Jimeno C, Sayalero S, Pericàs MA. In: Barbaro, P, Liguori, F, editors. Catalysis by metal complexes, vol. 33: heterogenized homogeneous catalysis for fine chemicals production. Berlin: Springer, 2010:123–70.10.1021/cr800200tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Ding KJ, Uozomi FJ. Handbook of asymmetric heterogeneous catalysts. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2008.10.1002/9783527623013Suche in Google Scholar

[25] For a perspective on chiral supported metal-free catalysts see: Benaglia M. Recoverable and recyclable chiral organic catalysts. New J Chem. 2006;30:1525–33.10.1039/b610416aSuche in Google Scholar

[26] Chiroli V, Benaglia M, Cozzi F, Puglisi A, Annunziata R, Celentano G. Continuous-flow stereoselective organocatalyzed Diels Alder reactions in a chiral catalytic “homemade” HPLC column. Org Lett. 2013;15:3590.10.1021/ol401390zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Puglisi A, Benaglia M, Annunziata R, Chiroli V, Porta R, Gervasini A. Chiral hybrid inorganic-organic materials: synthesis, characterization and application in stereoselective organocatalytic cycloadditions. J Org Chem. 2013;78:11326–33.10.1021/jo401852vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] For recent reviews on stereoselective catalytic reactions in flow see: a) Tsubogo T, Ishiwata T, Kobayashi S Asymmetric carbon-carbon bond formation under continuous-flow conditions with chiral heterogeneous catalysts. Angew Chem Int Ed 2013, 52, 6590; b) Puglisi A, Benaglia M, Chiroli V. Stereoselective organic reactions promoted by immobilized chiral catalysts in continuous flow systems. Green Chem. 2013;15:1790; c) Atodiresei I, Vila C, Rueping M, Asymmetric organocatalysis in continuous flow: opportunities for impacting industrial catalysis. ACS Catal 2015;5:1972.10.1002/anie.201210066Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Chiroli V, Benaglia M, Puglisi A, Porta R, Jumde RP, Mandoli A. A chiral organocatalytic polymer-based monolithic reactor. Green Chem. 2014;16:2798–806.10.1039/c4gc00031eSuche in Google Scholar

[30] Porta R, Benaglia M, Puglisi A, Mandoli A, Gualandi A, Cozzi PG. A catalytic reactor for organocatalyzed enantioselective continuous flow alkylation of aldehyde. ChemSusChem. 2014;7:3534–40.10.1002/cssc.201402610Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Porta R, Benaglia M, Annunziata R, Puglisi A, Celentano G. Solid supported chiral N-picolyl-imidazolidinones: recyclable catalysts for the enantioselective,metal- and H2-free reduction of imines in batch and in flow mode. Adv Synth Catal. 2017;359:2375–82.10.1002/adsc.201700376Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Porta R, Benaglia M, Puglisi A. Flow chemistry: recent developments in the synthesis of pharmaceutical products. Org Process Res Dev. 2016;20:2–25.10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00325Suche in Google Scholar

[33] a) Zhou QL, editor. Privileged chiral ligands and catalysts, 2011, NJ, USA: Wiley; b) Yoon, TP, Jacobsen, EN. Privileged chiral catalysts. Science. 2003;299:1691.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Chiral imidazolidinones: A class of priviliged organocatalysts in stereoselective organic synthesis

- Computer-based techniques for lead identification and optimization II: Advanced search methods

- Basic principles of substrate activation through non-covalent bond interactions

- Cyanine dyes

- Technology of large volume alcohols, carboxylic acidsand esters

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Chiral imidazolidinones: A class of priviliged organocatalysts in stereoselective organic synthesis

- Computer-based techniques for lead identification and optimization II: Advanced search methods

- Basic principles of substrate activation through non-covalent bond interactions

- Cyanine dyes

- Technology of large volume alcohols, carboxylic acidsand esters