Abstract

This study investigates the choice between two near-synonymous Mandarin Chinese possessive constructions, namely, the PP+DE+N (e.g., wǒ de mama, ‘my mom’) and PP+N (e.g., wǒ mama, ‘my mom’). Deploying a mixed effects logistic regression model to evaluate the impact of linguistic (syntactic and semantic) and extralinguistic (register) factors, this study reveals a substantial relationship between the selection of possessive constructions and several fixed effects including the number of attributes before N, the syntactic component of PP+(DE)+N, the semantic connection between PP and N, the person and number of the PP, and the context or style of the texts. Furthermore, this study uncovers that the noun serves as an essential random effect that helps determine the conceptual distance between the PP and N. To conclude, this study unveils the patterns governing the use or omission of de in Mandarin Chinese possessive constructions, hence enhancing our comprehension of syntactic nuances in the language. It also offers a potent methodological approach for future investigations of the reasons underpinning the formal marking of possessive constructions.

1 Introduction

Every language encompasses possessive constructions,[1] as underscored by both Robert Dixon (2010: 262) and Ronald Langacker (1995: 51). However, crosslinguistic discrepancies exist concerning the formal marking of these constructions across diverse languages. Dixon elucidates this variation, observing that formal markers may appear on the possessor, on the possessed, on both, or on neither, in what he terms as ‘simply apposed’ (Dixon 2010: 262). In the context of Mandarin Chinese, possessive constructions generally incorporate the genitive marker de suffixed to the possessor, as demonstrated in Example (1).

| 老師 | 的 | 書 |

| lǎoshī | de | shū |

| teacher | GEN | book |

| ‘teache’s book’ | ||

However, the emergence of de becomes complex when the personal pronoun (PP) functions as the possessor, a scenario that is most prevalent and prototypical in Mandarin Chinese possessive constructions (MPC),[2] as illustrated in example (2).

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom |

| ‘my mom’ | ||

| 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom’ | |

| 我 | 的 | 書 |

| wǒ | de | shū |

| 1sg | GEN | book |

| ‘my book’ | ||

| * | 我 | 書 |

| wǒ | shū | |

| 1sg | book | |

| ‘my book’ | ||

Both constructions (2a) and (2c) follow the PP+DE+N schema, while (2b) and (2d) adhere to the PP+N schema. Although (2a) and (2b) are grammatically correct and nearly synonymous possessive constructions, the grammaticality of (2c) and (2d) is directly contingent upon the inclusion or exclusion of de. This raises a pertinent question: what factors govern the presence or absence of the formal marker de. Answering this question not only elucidates the rationale behind the formal marking of MPC, but may also contribute to typological studies of possessive constructions in other languages.

In order to address the above question, the present study employs mixed-effects logistic regression to model the choice between the PP+DE+N and PP+N constructions in Mandarin Chinese. Utilizing corpus data, this study differentiates between fixed and random effects, and quantifies both linguistic factors (syntactic and semantic) and extralinguistic factors (register).[3]

The primary distinction between the PP+DE+N and PP+N constructions resides in the presence or absence of de. Extensive exploration of this topic can be found in previous literature, with the three most notable perspectives proposed by Cui Xiliang (1992), Zhang Min (1998), and Xu Yangchun (2008).

Cui Xiliang (1992) posits that the inclusion or exclusion of de when PP is used as an attributive depends on whether the possessive relationship between PP and the head noun is changeable. If the relationship is not changeable, de can either be present or omitted, rendering both the PP+DE+N form wǒ de bàba (meaning ‘my father’) and the PP+N form wǒ bàba (also meaning ‘my father’) grammatically correct. However, when the relationship is changeable, de becomes obligatory. Consequently, ‘my watch’ can only be expressed in the PP+DE+N form ‘wǒ de shǒubiǎo’, not in the PP+N form ‘wǒ shǒubiǎo’.

Zhang Min (1998) identifies two conditions that determine whether PP and N can form a direct relationship without the inclusion of de: (1) whether PP+DE+N can be represented by proper names; (2) whether PP+DE+N signifies a bidirectional possessive relationship. For instance, the PP+DE+N form wǒ de gēge (meaning ‘my elder brother’) can be represented by a proper name (such as a man named ‘Zhang San’), allowing for the omission of de between PP wǒ (‘I’) and N gēge ‘elder brother’. Conversely, the PP+DE+N form wǒ de shǒubiǎo ‘my watch’ cannot be represented by a unique proper name, necessitating the inclusion of de between PP wǒ ‘I’ and N shǒubiǎo ‘watch’. Furthermore, a bidirectional possessive relationship exists between PP wǒ ‘I’ and N gēge ‘elder brother’, indicating that I have an elder brother and concurrently, my elder brother has me as a younger sibling. This allows for the omission of de between wǒ ‘I’ and gēge ‘elder brother’. This contrasts with the unidirectional possessive relationship between PP wǒ ‘I’ and N shǒubiǎo ‘watch’, where shǒubiǎo ‘watch’ can only be owned by PP wǒ ‘I’, requiring the inclusion of de between wǒ ‘I’ and shǒubiǎo ‘watch’.

Xu Yangchun (2008) employs the principle of relational combination to elucidate the inclusion or omission of de when PP is used as an attributive. He posits that if PP+N corresponds to an appellation relationship (as in tā érzi ‘his son’), a member-unit relationship (as in tāmen gōngsī ‘their company’), or a reference-location relationship (as in tā qiánmiàn ‘in front of her’), then de can be omitted between PP and N.

In conclusion, the aforementioned research provides a qualitative understanding of the rules governing the presence or absence of de in the PP+(DE)+N construction. However, the principles and conditions outlined in these studies are challenging to apply as quantitative criteria when faced with extensive corpus data. Concepts like ‘changeable possessive relationship,’ ‘bidirectional possessive relationship,’ and the ‘principle of relational combination’ are particularly suited for elucidating a confined set of introspective data that scrutinizes the conceptual dynamics between personal pronouns (PP) and nouns (N). Nevertheless, the characteristics of PP (e.g., person, gender, number), the nuanced semantics of N (representing entities such as ‘mom,’ ‘country,’ ‘mind,’ ‘room,’ etc.), and the broader contextual framework within which PP+(DE)+N are positioned (whether the entire structure functions as the subject or object, whether it is utilized in literary works or journalistic pieces) can collectively influence the selection between PP+(DE)+N and PP+N. To comprehensively evaluate all these variables within extensive corpora, a quantitative analysis characterized by objectivity is imperative. Hence, this study endeavors to identify explanatory variables that establish clear boundaries to predict the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N. Specifically, this study seeks to determine the significance of these explanatory variables and, if significant, quantify their explanatory power.

2 Data and methodology

2.1 Data

The data utilized in this study were sourced from the Beijing Language and Culture University Corpus Center (BCC) Corpus. This expansive online Chinese corpus boasts a volume of approximately 9.5 billion characters. It encompasses a diverse range of sources, including newspapers (2 billion characters), literature (3 billion characters), comprehensive data (1.9 billion characters), ancient Chinese texts (2 billion characters), and dialogues (600 million characters, derived from microblogs and movie subtitles). Given its vast scale and diversity, the BCC Corpus provides a comprehensive representation of language usage within contemporary Chinese society.

The methodology for extracting targeted data from the corpus is outlined as follows.

Extract 16 combinations for each of PP+DE+N and PP+N based on 8 distinct personal pronouns in Mandarin Chinese and 2 registers in BCC.[4]

From the 150 most frequent character strings in each combination, as determined by the corpus, identify nouns appearing more than half the time across the 16 combinations in both constructions.

Extract 33 nouns with high frequency in both PP+DE+N and PP+N constructions (refer to Table 1).

Query each combination within the corpus and extract five representative sentences for each to ensure a sufficient data pool.

Procure a total of 4,050 observations, including 2,349 instances of PP+DE+N and 1701 instances of PP+N.

Manually code the observations according to explanatory variables detailed in Section 2.3.

The most frequently occurring nouns in PP+DE+N and PP+N. ‘父親 fùqin (father)’ and ‘母親 mǔqin (mother)’ are predominantly used in written contexts, whereas ‘爸爸 bàba (dad)’ and ‘媽媽 mama (mom)’ are primarily utilized in spoken discourse. ‘建議 jiànyì (suggestion)’, ‘病 bìng (disease)’, ‘計畫 jìhuà (plan)’ can also be interpreted as verbs. This study determines their noun status based on the syntactic role they play. For instance, in PP+DE+N constructions, they typically act as subjects (e.g., 他的病好了, ‘His illness has recovered’) or objects (e.g., 治好了他的病, ‘cured his illness’), establishing them as nouns. Similarly, in PP+N constructions, they frequently appear within prepositional phrases (e.g., 在他建議下, ‘at his suggestion’; 在他病中, ‘during his illness’), further confirming their noun classification in these contexts.

| 兄弟 xiōngdì ‘brother’ |

父親 fùqin ‘father’ |

孩子 háizi ‘child’ |

母親 mǔqin ‘mother’ |

兒子 érzi ‘son’ |

| 父母 fùmǔ ‘parent’ |

哥哥 gēge ‘elder brother’ |

爸爸 bàba ‘dad’ |

媽媽 mama ‘mom’ |

女兒 nǚ’ér ‘daughter’ |

| 手 shǒu ‘hand’ |

人 rén ‘people’ |

心 xīn ‘heart’ |

身體 shēntǐ ‘body’ |

臉 liǎn ‘face’ |

| 內心 nèixīn ‘inner heart’ |

腳 jiǎo ‘foot’ |

思想 sīxiǎng ‘thought’ |

生命 shēngmìng ‘life’ |

頭腦 tóunǎo ‘mind’ |

| 心靈 xīnlíng ‘soul’ |

國家 guójiā ‘country’ |

耳朵 ěrduo ‘ear’ |

錢 qián ‘money’ |

眼睛 yǎnjīng ‘eye’ |

| 精神 jīngshén ‘spirit’ |

建議 jiànyì ‘suggestion’ |

病 bìng ‘disease’ |

信 xìn ‘letter’ |

房間 fángjiān ‘room’ |

| 計畫 jìhuà ‘plan’ |

家庭 jiātíng ‘family’ |

心情 xīnqíng ‘mood’ |

2.2 Mixed effects models

Mixed-effects models, often abbreviated as mixed models, incorporate both fixed and random effects. As delineated by Rolf Baayen (2008: 241), fixed effects are employed for factors with replicable levels, whereas random effects are utilized for ‘factors with levels randomly sampled from a substantially larger population’. Within the context of linguistic experiments and studies, items (words) and subjects (participants) frequently serve as common random effects.

Mixed models have been employed in research pertaining to constructions and metonymic words and expressions, as evidenced in studies by Natalia Levshina et al. (2013), and Zhang Weiwei et al. (2018; 2011]. Furthermore, numerous studies within the realm of second language acquisition have also utilized mixed models. These include, but are not limited to, works by Wu Shiyu et al. (2017), Qi Jing and Wang Hua (2020), Fang Yinjie and Liang Maocheng (2020), and Ji Yinglin (2020), as well as Lu Shiyi et al. (2020).

Mixed models are employed in this study to investigate various factors within PP+(DE)+N constructions due to their ability to quantify the cumulative impact of both fixed and random effects of explanatory variables, thereby ensuring high model accuracy. To facilitate the fitting of mixed models, this study utilizes the glmer() function from the lme4 package in R.

2.3 Variables[5]

The variables incorporated within the mixed models are delineated as follows. Variables A-H serve as explanatory variables for fixed effects, while Variable I is the explanatory variable for the random effect. Variable J functions as the response variable. From another perspective, Variables A-C and E-G represent syntactic factors, whereas Variables D and I denote semantic factors. Variable H corresponds to the extralinguistic register factor.

A Number of attributes in the NP (abbreviated as num_attr)

Cheng Shuqiu (2009: 69) posits that an increase in the number of attribute items correlates with a higher likelihood of de being omitted following the possessive attribute. Consequently, this study designates the levels of num_attr preceding N as 1, 2, and multiple (abbreviated as ‘m’; applicable when num_attr exceeds 2).

num_attr = 1:

| 我 | (的) | 哥哥 |

| wǒ | de | gēge |

| 1sg | GEN | elder brother |

| ‘my elder brother’ | ||

num_attr = 2:

| 我 | (的) | 哥哥 | 的 | 工作 |

| wǒ | de | gēge | de | gōngzuò |

| 1sg | GEN | elder brother | GEN | job |

| ‘my elder brother’s job’ | ||||

num_attr = m:

| 我 | (的) | 哥哥 | 的 | 工作 | (的) | 地點 |

| wǒ | de | gēge | de | gōngzuò | de | dìdiǎn |

| 1sg | GEN | elder bother | GEN | job | GEN | place |

| ‘my elder brother’s working place’ | ||||||

B Position

Cheng Shuqiu (2009: 110) proposes that within a noun phrase (NP), the attribute situated closer to the center is more likely to carry de, whereas the attribute nearer to either end is more prone to omit de. Consequently, this study establishes the levels of the attributive position of PP as left (abbreviated as ‘l’), middle (abbreviated as ‘m’), right (abbreviated as ‘r’), and NA (applicable when only one attribute exists within an NP).

position = l:

| 我 | (的) | 爸爸 | 的 | 錢 |

| wǒ | de | bàba | de | qián |

| 1sg | GEN | dad | GEN | money |

| ‘my dad’s money’ | ||||

position = m:

| 當時 | 的 | 我 | (的) | 家庭 | 的 | 成員 |

| dāngshí | de | wǒ | de | jiātíng | de | chéngyuán |

| at that time | GEN | 1sg | GEN | family | GEN | member |

| ‘my family members at that time’ | ||||||

position = r:

| 善良 | 的 | 我 | (的) | 爸爸 |

| shànliáng | de | wǒ | de | bàba |

| kindhearted | GEN | 1sg | GEN | dad |

| ‘my kindhearted dad’ | ||||

position = NA:

| 我 | (的) | 爸爸 |

| wǒ | de | bàba |

| 1sg | GEN | dad |

| ‘my dad’ | ||

C Syntactic component (abbreviated as syn_comp)

Lu Bingfu (2011) and Pan Tingting (2021) suggest that an NP containing de is more likely to be omitted when it functions as a subject, compared to when it serves as an object. Consequently, this study differentiates the syntactic composition (syn_comp) of PP+(DE)+N as subject (abbreviated as ‘s’), object (abbreviated as ‘o’), and NA (applicable when PP+(DE)+N functions as both subject and object).

syn_comp = s:

| 我 | (的) | 爸爸 | 是 | 老師。 |

| wǒ | de | bàba | shì | lǎoshī |

| 1sg | GEN | dad | COP | teacher |

| ‘My dad is a teacher.’ | ||||

syn_comp = o:

| 她 | 是 | 我 | (的) | 媽媽。 |

| tā | shì | wǒ | de | māma |

| 3sg.f | COP | 1sg | GEN | mom |

| ‘She is my mom.’ | ||||

| 書 | 放 | 在 | |

| shū | fàng | zài | |

| book | put | prep | |

| 我 | (的) | 手 | 上。 |

| wǒ | de | shǒu | shàng |

| 1sg | GEN | hand | used after a noun to indicate the surface of something |

| ‘The book is in my hands.’ | |||

syn_comp = NA:

| 她 | 讓 | 她 | (的) | 孩子 | 學習。 |

| tā | ràng | tā | de | háizi | xuéxí |

| 3sg.f | let | 3sg.f | GEN | child | study |

| ‘She let her child study.’ | |||||

| 愛 | 我們 | 的 | 父母 | 是 | 好事。 |

| ài | wǒmen | de | fùmǔ | shì | hǎoshì |

| love | 1pl | GEN | parent | COP | good deed |

| ‘It’s good to love our parents.’ | |||||

In the given examples, the PP+(DE)+N construction plays different roles within the sentence structure. In (10), wǒ de bàba ‘my dad’ functions as the subject of the sentence. In (11a), wǒ de māma ‘my mom’ serves as the object of the copula shì. In (11b), wǒ de shǒu ‘my hand’ is the object of the preposition zài. In (12a), tā de háizi ‘her child’ acts as both the object of ràng ‘let’ and the subject of xuéxí ‘study’. In (12b), wǒmen de fùmǔ ‘our parents’ is the object of ài ‘love’, while ài wǒmen de fùmǔ ‘love our parents’ serves as the subject of the sentence.

D Semantic relationship (abbreviated as sem_rel)

Chen Zhenyu and Ye Jingting (2014) propose a hierarchy of ‘controllability levels’, which they delineate as follows: organs, body parts > common noun > real space > kinship terms > general appellation > family, unit, and other collective nouns. Within this hierarchy, elements positioned towards the left exhibit a higher degree of controllability and a greater propensity for the utilization of possessive markers, such as de. Conversely, elements situated towards the right demonstrate a lower degree of controllability and a reduced tendency to employ possessive markers. To investigate the potential influence of the semantic relationship between PP and N on the inclusion or exclusion of de, this study incorporates semantic relationship (sem_rel) annotations across six categories: kinship relationships, attributes, whole-part relationships, ownership, associations, and nominalizations.

Kinship relationship:

| 我 | (的) | 母親 |

| wǒ | de | mǔqin |

| 1sg | GEN | mother |

| ‘my mother’ | ||

An attribute:

| 我 | 的 | 心情 |

| wǒ | de | xīnqíng |

| 1sg | GEN | mood |

| ‘my mood’ | ||

Whole-part relationship:

| 我 | 的 | 手 |

| wǒ | de | shǒu |

| 1sg | GEN | hand |

| ‘my hand’ | ||

Ownership:

| 我 | (的) | 房間 |

| wǒ | de | fángjiān |

| 1sg | GEN | room |

| ‘my room’ | ||

Association:

| 我 | (的) | 國家 |

| wǒ | de | guójiā |

| 1sg | GEN | country |

| ‘my country’ | ||

Nominalization:

| 我 | 的 | 計畫 |

| wǒ | de | jìhuà |

| 1sg | GEN | plan |

| ‘my plan’ | ||

E Person

Robert Dixon (1979: 85) introduces the concept of a ‘potentiality of agency’ scale, suggesting that first and second person pronouns are more likely to serve as transitive agents compared to third person pronouns. In a similar vein, William Croft (2002: 130) advances an ‘extended animacy hierarchy’, positing that first and second person pronouns exhibit a higher degree of animacy than third person pronouns. To examine the potential influence of the person of the PP on the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N constructions, this study categorizes PP as first person pronouns (denoted as 1), second person pronouns (denoted as 2), and third person pronouns (denoted as 3).

Person = 1:

| 我 | 的 | 建議 |

| wǒ | de | jiànyì |

| 1sg | GEN | suggestion |

| ‘my suggestion’ | ||

Person = 2:

| 你 | 的 | 建議 |

| nǐ | de | jiànyì |

| 2sg | GEN | suggestion |

| ‘your suggestion’ | ||

Person = 3:

| 他 | 的 | 建議 |

| tā | de | jiànyì |

| 3sg.m | GEN | suggestion |

| ‘his suggestion’ | ||

F Number of the PP (abbreviated as num_pp)

Chen Yu-Jie (2008) delineates the plural semantics of Chinese possessive constructions, particularly those modified by plural personal pronouns, into two distinct categories. The first category, referred to as Plural Meaning 1, signifies the aggregate of disparate entities. An illustration of this is the phrase wǒmen de nǎodai, which translates to ‘our heads’, and is the sum of ‘my head’, ‘his head’, ‘your head’, and so forth. Conversely, the second category, Plural Meaning 2, conveys an indivisible entity. For instance, wǒmen de xuéxiào ‘our school’ represents the school to which we belong, rather than the sum of ‘my school’, ‘his school’, ‘your school’, etc. Chen Yu-Jie (2008) further elucidates that possessive constructions falling under Plural Meaning 1 necessitate the inclusion of de, whereas those under Plural Meaning 2 are typically interpreted as singular and often exclude de. Consequently, this study employs the tags of num_pp as singular (abbreviated as ‘sg’) and plural (abbreviated as ‘pl’) with the objective of examining whether the number of personal pronouns influences the choice between the constructions PP+DE+N and PP+N.

Num_pp = sg:

| 我 | (的) | 兄弟 |

| wǒ | de | xiōngdì |

| 1sg | GEN | brother |

| ‘my brother’ | ||

Num_pp = pl:

| 我們 | 的 | 兄弟 |

| wǒmen | de | xiōngdì |

| 1pl | GEN | brother |

| ‘our brother’ | ||

G Style

Li Tianguang (2012) posits that attributives in narrative and descriptive texts tend to be more complex and frequently used, typically followed by de. Conversely, in legal, scientific, and journalistic texts, which favor brevity and structural compactness, the usage of de is less prevalent. To examine whether the style of a text influences the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N, this study categorizes two styles within the corpus: literature (abbreviated as ‘lit’) and newspaper (abbreviated as ‘news’).

H Noun

The aforementioned 33 most frequently occurring nouns are incorporated into the analysis to investigate whether noun variation influences the selection between PP+DE+N and PP+N.

I Construction choices (abbreviated as cxn)

The choices of construction are bifurcated into two levels: PP+DE+N and PP+N.

In summary, Table 2 encapsulates all the variables examined in this study, while Table 3 presents the frequency distribution of the explanatory variables.

Summary of variables.

| Explanatory variable A | Num_attr | syntactic | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable B | Position | syntactic | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable C | Syn_comp | syntactic | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable D | Sem_rel | semantic | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable E | Person | syntactic | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable F | Num_pp | syntactic | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable G | Style | register | fixed effects |

| Explanatory variable H | Noun | semantic | random effects |

| Response variable I | Cxn |

The frequency distribution of the explanatory variables.

| Variables | Frequency | w/woa | Variables | Frequency | w/wo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num_attr = 1 | 3,624 | 2,270/1,354 | Noun = brother | 102 | 73/29 |

| Num_attr = 2 | 266 | 69/197 | Noun = father | 146 | 75/71 |

| Num_attr = m | 160 | 10/150 | Noun = child | 121 | 78/43 |

| Position = l | 416 | 74/342 | Noun = mother | 143 | 79/64 |

| Position = m | 4 | 0/4 | Noun = son | 140 | 77/63 |

| Position = r | 6 | 5/1 | Noun = parent | 141 | 74/67 |

| Position = na | 3,624 | 2,270/1,354 | Noun = elder brother | 110 | 70/40 |

| Syn_comp = s | 1,077 | 519/558 | Noun = dad | 132 | 76/56 |

| Syn_comp = o | 2,483 | 1,639/844 | Noun = mom | 122 | 71/51 |

| Syn_comp = na | 490 | 191/299 | Noun = daughter | 130 | 73/57 |

| Sem_rel = kin | 1,287 | 746/541 | Noun = hand | 157 | 79/78 |

| Sem_rel = attr | 1,095 | 608/487 | Noun = people | 25 | 19/6 |

| Sem_rel = whlpt | 873 | 449/424 | Noun = heart | 144 | 73/71 |

| Sem_rel = own | 261 | 181/80 | Noun = body | 143 | 78/65 |

| Sem_rel = assoc | 285 | 168/117 | Noun = face | 154 | 76/78 |

| Sem_rel = nomi | 249 | 197/52 | Noun = inner heart | 144 | 73/71 |

| Person = 1 | 1,055 | 597/458 | Noun = foot | 150 | 76/74 |

| Person = 2 | 977 | 589/388 | Noun = thought | 134 | 76/58 |

| Person = 3 | 2,018 | 1,163/855 | Noun = life | 121 | 80/41 |

| Num_pp = sg | 2,194 | 1,204/990 | Noun = mind | 142 | 76/66 |

| Num_pp = pl | 1,856 | 1,145/711 | Noun = soul | 142 | 75/67 |

| Style = lit | 2,095 | 1,209/886 | Noun = country | 115 | 72/43 |

| Style = news | 1,955 | 1,140/815 | Noun = ear | 130 | 72/58 |

| Noun = money | 68 | 68/0 | |||

| Noun = eye | 138 | 73/65 | |||

| Noun = spirit | 137 | 75/62 | |||

| Noun = suggestion | 73 | 70/3 | |||

| Noun = disease | 95 | 62/33 | |||

| Noun = letter | 67 | 43/24 | |||

| Noun = room | 126 | 70/56 | |||

| Noun = plan | 81 | 65/16 | |||

| Noun = family | 145 | 77/68 | |||

| Noun = mood | 132 | 75/57 |

-

aPP+DE+N is denoted as ‘w’, signifying constructions with de, while PP+N is represented as ‘wo’, indicating constructions without de. ‘w/wo’ is used to express the ratio between these two types of constructions.

3 Results

3.1 Model overview

The initial model is formulated as follows:

cxn ∼ num_attr + position + syn_comp + sem_rel + person + num_pp + style + (1|Noun)

The analysis reveals that the coefficients for position = NA was excluded due to rank deficiency in the fixed-effect model matrix. Additionally, a quasi-complete separation was observed between the variables position and num_attr. Upon the removal of the variable position, the final model is articulated as:

cxn ∼ num_attr + syn_comp + sem_rel + person + num_pp + style + (1|Noun)

The final model demonstrates a satisfactory fit to the data, as evidenced by a goodness-of-fit measure of C = 0.75. Moreover, the classification accuracy of the final model surpasses the baseline accuracy of 58 % (2,349/4,050), reaching a notable 70.3 %.

The methods for model validation were based on the approach proposed by Fang Yu and Liu Haitao (2021). Initially, the data in this study were randomly divided into two sets, namely the training set (comprising 75 % of the data) and the test set (comprising the remaining 25 % of the data). Subsequently, the final model was fitted to each training set, and its predictions were evaluated using the corresponding test set. The average classification accuracy across the 100 models was found to be 66.41 %, with a maximum accuracy of 68.68 % and a minimum accuracy of 64.33 %. Notably, this average accuracy surpassed the baseline accuracy of 58 %.

To assess the presence of multicollinearity among the explanatory variables for fixed effects in the final model, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was computed. The results revealed that there was no significant multicollinearity, as indicated by a maximum VIF of 1.02.

Furthermore, the importance of each explanatory variable for fixed effects was validated using the Anova() function from the car package in R. The analysis demonstrated that all six variables included in the final model significantly contributed to predicting the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N. Notably, the three most influential variables were identified as num_attr, syn_comp, and num_pp.

3.2 The analysis of fixed effects

Table 4 displays a comprehensive summary of the fixed effects observed in the final model. It is worth noting that variables exhibiting a positive estimate are associated with an increased likelihood of PP+N, whereas variables displaying a negative estimate suggest a preference for PP+DE+N.

Estimates of the fixed effects in the final model.

| Variables | Estimate | Std. error | z value | Pr(>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.341 | 0.150 | 2.272 | 0.023* |

| Num_attr = 2 | 2.150 | 0.158 | 13.641 | <0.001*** |

| Num_attr = m | 3.990 | 0.343 | 11.633 | <0.001*** |

| Syn_comp = o | −0.981 | 0.083 | −11.812 | <0.001*** |

| Syn_comp = na | 0.499 | 0.117 | 4.267 | <0.001*** |

| Sem_rel = attr | −0.039 | 0.176 | −0.222 | 0.824 |

| Sem_rel = whlpt | 0.618 | 0.189 | 3.268 | 0.001** |

| Sem_rel = own | −0.352 | 0.278 | −1.267 | 0.205 |

| Sem_rel = assoc | −0.316 | 0.270 | −1.167 | 0.243 |

| Sem_rel = nomi | −1.193 | 0.293 | −4.070 | <0.001*** |

| Person = 2 | −0.242 | 0.100 | −2.418 | 0.016* |

| Person = 3 | −0.179 | 0.085 | −2.105 | 0.035* |

| Num_pp = pl | −0.533 | 0.073 | −7.325 | <0.001*** |

| Style = news | −0.165 | 0.071 | −2.320 | 0.020* |

-

Significance codes: *** for p < 0.001, ** for 0.001 ≤ p < 0.01, * for 0.01 ≤ p < 0.05

Based on the findings presented in Table 4, it is evident that all the p-values associated with the variables in the final model are below the conventional level of significance (0.05), except for sem_rel = attr, sem_rel = own, and sem_rel = assoc. This implies that, in comparison to the reference level of sem_rel = kinsh, there is no statistically significant distinction between PP+DE+N and PP+N when sem_rel is characterized as attr, own, or assoc.

The intercept estimate in the final model is 0.341, with a significance level of 0.01 ≤ p < 0.05. This indicates a relatively significant difference between PP+DE+N and PP+N when all fixed effects variables are at their reference levels, namely num_attr = 1, syn_comp = s, sem_rel = kinsh, person = 1, num_pp = sing, and style = lit. Since the estimate represents the log odds, it is exponentiated to obtain simple odds. Upon exponentiation, the odds of PP+N compared to PP+DE+N are approximately 1.4. This implies that in the context of literary style, when a first-person singular pronoun functions as an attribute, the head of the phrase is a kinship term, and the entire noun phrase occupies the subject position, PP+N constructions occur approximately 1.4 times more frequently than PP+DE+N. To illustrate this preference, consider example (24) where the symbol ‘ > ’ denotes a higher frequency on the left side compared to the right side:

| In literary works: | |||||||||

| 我 | 媽媽 | + | pred | > | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | + | pred |

| wǒ | māma | + | pred | > | wǒ | de | māma | + | pred |

| 1sg | mom | + | pred | > | 1sg | GEN | mom | + | pred |

| ‘my mom (PP+N) +pred > my mom (PP+DE+N) +pred’ | |||||||||

The shorter form of 我媽媽 wǒ māma ‘my mom’ compared to 我的媽媽 wǒ de māma ‘my mom’ conveys a greater sense of intimacy and aligns better with the conceptual proximity between 我 wǒ ‘I’ and 媽媽 māma ‘mom’.

The estimate for num_attr = 2 is 2.150, which, when exponentiated, becomes 8.6. This indicates that when num_attr = 2, the frequency of PP+N is approximately 8.6 times higher than that of PP+DE+N, in comparison to the reference level of num_attr = 1. This preference is illustrated through examples (25) and (26):

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 媽媽 | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | māma | wǒ | de | māma |

| 1sg | mom | 1sg | GEN | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+DE+N)’ | |||

| 我 | 媽媽 | 的 | 工作 | > | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 的 | 工作 | |

| wǒ | māma | de | gōngzuò | > | wǒ | de | māma | de | gōngzuò | |

| 1sg | mom | GEN | job | > | 1sg | GEN | mom | GEN | job | |

| ‘the job of “my mom (PP+N)” > the job of “my mom (PP+DE+N)”’ | ||||||||||

The estimate for num_attr = m is 3.990, which equates to an odds ratio of 54.1 upon exponentiation. This signifies that relative to num_attr = 1, constructions with num_attr = m exhibit a 54.1 times higher frequency of PP+N compared to PP+DE+N. Examples (27) and (28) demonstrate this tendency of favoring PP+N when multiple attributes are present:

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 媽媽 | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | māma | wǒ | de | māma |

| 1sg | mom | 1sg | GEN | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+DE+N)’ | |||

| 我 | 媽媽 | 的 | 工作 | 地點 | |

| wǒ | māma | de | gōngzuò | dìdiǎn | |

| 1sg | mom | GEN | work | place | |

| > | |||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 的 | 工作 | 地點 |

| wǒ | de | māma | de | gōngzuò | dìdiǎn |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | GEN | work | place |

| ‘the working place of “my mom (PP+N)” > the working place of “my mom (PP+DE+N)”’ | |||||

Hence, the estimates for num_attr = 2 and num_attr = m provide evidence that an increase in the number of attributives corresponds to a higher occurrence rate of PP+N. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Cheng Shuqiu (2009).

The estimate of syn_comp = o is −0.981 (exponentiated as 0.375), signifing that compared with syn_comp = s, the frequency of PP+N with syn_comp = o is 37.5 % that of PP+DE+N. In other words, PP+DE+N occurs 2.7 (1/0.375) times more frequently than PP+N. Examples (29) and (30) illustrate this preferential selection.

| Reference level: | ||||||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | + | pred | 我 | 媽媽 | + | pred |

| wǒ | de | māma | + | pred | wǒ | mama | + | pred |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | + | pred | 1sg | mom | + | pred |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)+pred’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)+pred’ | |||||||

| pred | + | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | > | pred | + | 我 | 媽媽 |

| pred | + | wǒ | de | mama | > | pred | + | wǒ | māma |

| pred | + | 1sg | GEN | mom | > | pred | + | 1sg | mom |

| ‘pred+my mom (PP+DE+N) > pred+my mom (PP+N)’ | |||||||||

The rationale behind the compatibility of PP+DE+N with the object position has been elucidated in prior scholarly works. For instance, Pan Tingting (2021) posits that de serves a descriptive function by introducing new information, thereby rendering it more congruous in the object position.

The estimate of syn_comp = na is 0.499 (exponentiated as 1.6). This means that compared with syn_comp = s, when syn_comp = na, PP+N appears 1.6 times more frequently than PP+DE+N. Examples (31) and (32) illustrate this preference.

| Reference level: | ||||||||

| 我 | 媽媽 | + | pred | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | + | pred |

| wǒ | māma | + | pred | wǒ | de | mama | + | pred |

| 1sg | mom | + | pred | 1sg | GEN | mom | + | pred |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)+pred’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)+pred’ | |||||||

| 讓 | 我 | 媽媽 | + | pred | |

| ràng | wǒ | māma | + | pred | |

| let | 1sg | mom | + | pred | |

| > | |||||

| 讓 | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | + | pred |

| ràng | wǒ | de | māma | + | pred |

| let | 1sg | GEN | mom | + | pred |

| ‘let my mom (PP+N)+pred > let my mom (PP+DE+N)+pred’ | |||||

The reason for this preference may be related to sentence length. Sentences with a pivotal construction (SVOV) are typically longer than SVO sentences. The longer the sentence string becomes, the more likely it is for de to be omitted, resulting in a preference for PP+N over PP+DE+N.

The estimated value of sem_rel = whlpt is 0.618, which is exponentiated as 1.9. This indicates that when sem_rel = whlpt, PP+N occurs 1.9 times more frequently than PP+DE+N, compared to when sem_rel = kinsh. This preference is illustrated in examples (33) and (34).

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 媽媽 | 我 | 的 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | māma | wǒ | de | māma |

| 1sg | mom | 1sg | GEN | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+DE+N)’ | |||

| 我 | 手 | > | 我 | 的 | 手 |

| wó | shǒu | > | wǒ | de | shǒu |

| 1sg | hand | > | 1sg | GEN | hand |

| ‘my hand (PP+N) > my hand (PP+DE+N)’ | |||||

Omitting de is easier for whole-part semantic relationships than for kinship relationships, indicating that body parts are more inalienable while kinship seems more alienable.[6] First, Chinese culture emphasizes kinship and hierarchy, so de is used to create a sense of distance (respect) between relatives, making kinship seem more alienable. Second, ‘PP+body parts’ commonly appears after prepositions to form prepositional phrases, whereas ‘PP+kinship’ does not have the corresponding usage.

The estimated of sem_rel = nomi is −1.193, which is exponentiated as 0.303. This means that when sem_rel = nomi, the occurrence frequency of P+N is only 30.3 % of the occurrence frequency of PP+DE+N, compared to when sem_rel = kinsh. Another way to express this is that PP+DE+N occurs 3.3 times more frequently than PP+N. Examples (35) and (36) illustrate this preference.

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma | wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)’ | |||

| 我 | 的 | 建議 | > | 我 | 建議 |

| wǒ | de | jiànyì | > | wǒ | jiànyì |

| 1sg | GEN | suggestion | > | 1sg | suggestion |

| ‘my suggestion (PP+DE+N) > my suggestion (PP+N)’ | |||||

In instances where the head noun is a kinship word, the preceding PP and the noun typically exhibit an attribute-head relationship, thereby reducing the necessity for de to delineate this relationship. Conversely, when the head noun is the nominalization of a verb, the inclusion of de becomes essential. This requirement arises due to the potential overlap between the structure of a PP combined directly with a nominalization of a verb and the subject-verb structure. For instance, the phrase 我 wǒ ‘I, my’ + 建議 jiànyì ‘suggest, suggestion’ could be misinterpreted as the conventional Chinese subject-predicate sentence pattern ‘I suggest something’, rather than the intended ‘my suggestion’. Therefore, de is required to accurately signify the intended attribute-head relationship.

The estimated value for person = 2 is −0.242, which becomes 0.785 when exponentiated. This indicates when person = 2, the occurrence of PP+DE+N is 1.3 times more frequent than PP+N, in comparison to person = 1. Examples (37) and (38) provide a representation of this comparison.

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma | wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)’ | |||

| 你 | 的 | 媽媽 | > | 你 | 媽媽 |

| nǐ | de | māma | > | nǐ | māma |

| 2sg | GEN | mom | > | 2sg | mom |

| ‘your mom (PP+DE+N) > your mom (PP+N)’ | |||||

The aforementioned illustration demonstrates that the second person pronoun requires the addition of de to reinforce the speaker-listener distance, in contrast to the first person pronoun. This finding aligns with the concept of linguistic iconicity, as proposed by John Haiman (1983: 782), which suggests that the length of the message corresponds to the social distance between interlocutors, while maintaining equal referential content.

The estimate for person = 3 is −0.179, exponentiated as 0.836. It signifies that when person = 3, the occurrence of PP+DE+N is 1.2 times more frequent than PP+N, in comparison to person = 1. Examples (39) and (40) provide a representation of this tendency.

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma | wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)’ | |||

| 他 | 的 | 媽媽 | > | 他 | 媽媽 |

| tā | de | māma | > | tā | māma |

| 3sg.m | GEN | mom | > | 3sg.m | mom |

| ‘his mom (PP+DE+N) > his mom (PP+N)’ | |||||

Similar to person = 2, the aforementioned preference can be attributed to the motivation of linguistic iconicity, wherein the distance between the speaker and the third person pronoun necessitates the use of de to reinforce it.

The estimated value for num_pp = pl is −0.533 (exponentiated as 0.587). Therefore, when num_pp = pl, the occurrence of PP+DE+N is 1.7 times more frequent than PP+N, in comparison to num_pp = sg. Examples (41) and (42) illustrate this preference.

| Reference level: | ||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma | wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)’ | |||

| 我們 | 的 | 媽媽 | > | 我們 | 媽媽 |

| wǒmen | de | māma | > | wǒmen | māma |

| 1pl | GEN | mom | > | 1pl | mom |

| ‘our moms (PP+DE+N) > our moms (PP+N)’ | |||||

Given that the character string 我們 wǒmen ‘we’ + 媽媽 māma ‘mom’ can convey both an attribute-head meaning, ‘our moms’, and an appositive meaning, ‘we, as moms’, the presence of de between 我們 wǒmen ‘we’ and 媽媽 māma ‘mom’ serves to separate the attribute and the noun head.

The estimated value for style = news is −0.165 (exponentiated as 0.848). This indicates when style = news, the frequency of occurrence of PP+DE+N is 1.2 times higher than the frequency of occurrence of PP+N, in comparison to style = lit. The illustration for such tendency is shown in examples (43) and (44).

| Reference level (lit): | ||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma | wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N)’ | ‘my mom ((PP+N)’ | |||

| News: | |||||

| 我 | 的 | 媽媽 | > | 我 | 媽媽 |

| wǒ | de | māma | > | wǒ | māma |

| 1sg | GEN | mom | > | 1sg | mom |

| ‘my mom (PP+DE+N) > my mom (PP+N)’ | |||||

In the context of newspapers, where language tends to be more formal, the usage of PP+DE+N is more prevalent. Conversely, in literary works, where language tends to be more colloquial, the usage of PP+N is more common. This observation aligns with John Haiman’s (1983, p. 800) assertion that ‘the more respectful the register, the more syllables in the same message.’

Table 5 provides a comprehensive summary of the fixed effects preference. Upon reviewing Section 2.3, which introduces the variables, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The variables position and gender do not demonstrate sufficient relevance to be included in the fixed effects.

The effect of num_attr aligns with Cheng Shuqiu’s (2009) findings, which suggest that the omission of de after the possessive attribute is more likely as the number of attribute items increases. The effect of syn_comp is consistent with the research of Lu Bingfu (2011) and Pan Tingting (2021), who propose that NP with de is more likely to be omitted when it functions as a subject compared to when it functions as an object.

The effect of style contradicts Li Tianguang’s (2012) claim that the use of de is more frequent in narrative and descriptive works than in news works. Similarly, the effect of sem-rel opposes the findings of Chen Zhenyu and Ye Jingting (2014), who suggest that body parts, as opposed to kinship terms, have a higher tendency to use the possessive marker de due to their higher controllability.

The effect of person is not directly related to the ‘potentiality of agency’ or the ‘extended animacy hierarchy’ of personal pronouns mentioned earlier. Instead, it can be explained by the principle of linguistic iconicity, where the distance between the speaker and the second/third person pronoun necessitates the use of de for reinforcement. Similarly, the effect of num_pp is not strongly associated with the differentiation of plural meanings 1 and 2 proposed by Chen Yu-Jie (2008). Rather, it can be interpreted in terms of de marking the attribute-head meaning rather than the appositive meaning between PP and noun.

Preference of fixed effects.

| Variables | Preference (odds) |

|---|---|

| Num_attr = 2 | PP+N (8.6) |

| Num_attr = m | PP+N (54.1) |

| Syn_comp = o | PP+DE+N (2.7) |

| Syn_comp = na | PP+N (1.6) |

| Sem_rel = attr | – |

| Sem_rel = whlpt | PP+N (1.9) |

| Sem_rel = own | – |

| Sem_rel = assoc | – |

| Sem_rel = nomi | PP+DE+N (3.3) |

| Person = 2 | PP+DE+N (1.3) |

| Person = 3 | PP+DE+N (1.2) |

| Num_pp = pl | PP+DE+N (1.7) |

| Style = news | PP+DE+N (1.2) |

3.3 The analysis of the random effect

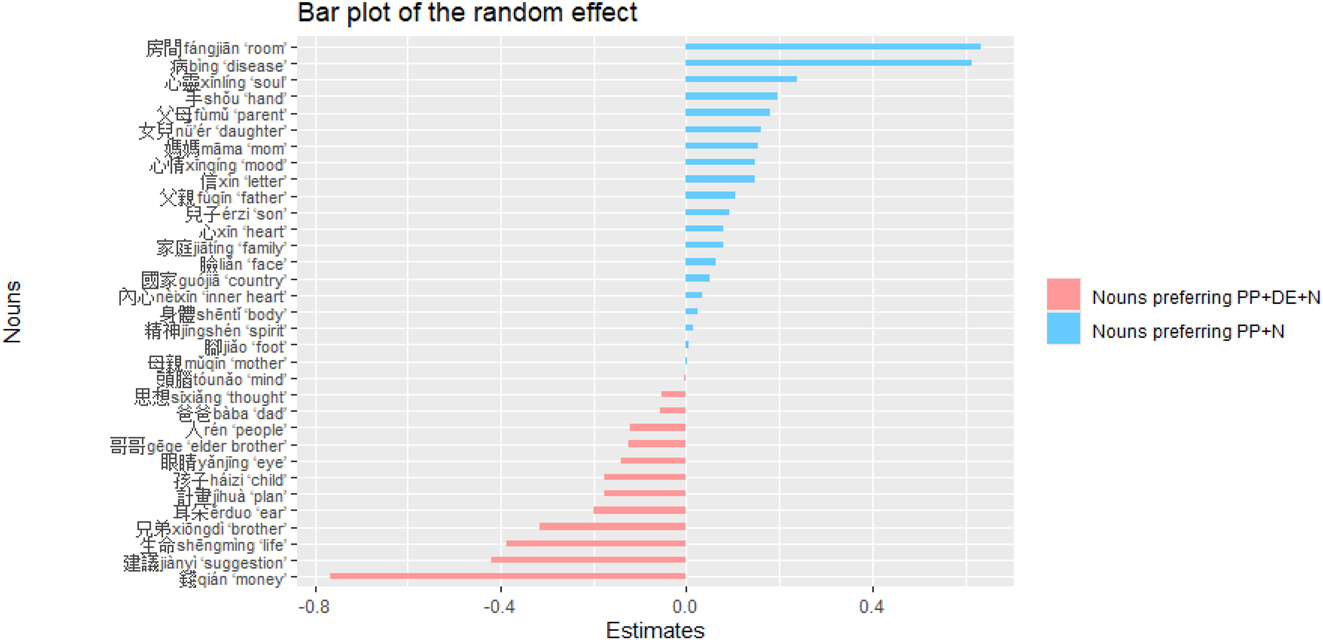

Table 6 provides a summary of the random effect observed in the final model. Among the 20 nouns with positive estimates, the preference is towards PP+N, whereas the 13 nouns with negative estimates exhibit a preference for PP+DE+N. Figure 1 visualizes the summary using a bar plot, where nouns favoring PP+DE+N are depicted in red, and nouns favoring PP+N are represented in blue.

Summary of the random effect.

| Nouns preferring PP+N | estimate | Nouns preferring PP+DE+N | estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 房間 fángjiān ‘room’ | 0.634 | 錢 qián ‘money’ | −0.768 |

| 病 bìng ‘disease’ | 0.616 | 建議 jiànyì ‘suggestion’ | −0.421 |

| 心靈 xīnlíng ‘soul’ | 0.238 | 生命 shēngmìng ‘life’ | −0.388 |

| 手 shǒu ‘hand’ | 0.195 | 兄弟 xiōngdì ‘brother’ | −0.317 |

| 父母 fùmǔ ‘parent’ | 0.180 | 耳朵 ěrduo ‘ear’ | −0.198 |

| 女兒 nǚ’ér ‘daughter’ | 0.159 | 計畫 jìhuà ‘plan’ | −0.177 |

| 媽媽 māma ‘mom’ | 0.155 | 孩子 háizi ‘child’ | −0.176 |

| 心情 xīnqíng ‘mood’ | 0.149 | 眼睛 yǎnjīng ‘eye’ | −0.142 |

| 信 xìn ‘letter’ | 0.148 | 哥哥 gēge ‘elder brother’ | −0.124 |

| 父親 fùqīn ‘father’ | 0.105 | 人 rén ‘people’ | −0.122 |

| 兒子 érzi ‘son’ | 0.091 | 爸爸 bàba ‘dad’ | −0.057 |

| 家庭 jiātíng ‘family’ | 0.080 | 思想 sīxiǎng ‘thought’ | −0.055 |

| 心 xīn ‘heart’ | 0.080 | 頭腦 tóunǎo ‘mind’ | −0.004 |

| 臉 liǎn ‘face’ | 0.063 | ||

| 國家 guójiā ‘country’ | 0.050 | ||

| 內心 nèixīn ‘inner heart’ | 0.033 | ||

| 身體 shēntǐ ‘body’ | 0.025 | ||

| 精神 jīngshén ‘spirit’ | 0.014 | ||

| 腳 jiǎo ‘foot’ | 0.005 | ||

| 母親 mǔqīn ‘mother’ | 0.002 |

Bar plot of the random effect.

Nouns that prefer PP+N can be categorized into the following five classes:

房間 fángjiān ‘room’; 信 xìn ‘letter’:

Objects like rooms and letters possess a sense of privacy and are closely associated with the individual. As a result, the omission of de before these nouns is more common.

病 bìng ‘disease’; 心靈 xīnlíng ‘soul’; 心情 xīnqíng ‘mood’; 心 xīn ‘heart’; 臉 liǎn ‘face’; 內心 nèixīn ‘inner heart’; 身體 shēntǐ ‘body’; 精神 jīngshén ‘spirit’:

These nouns possess unique characteristics and are closely tied to one’s own being, leading to a tendency to omit de before them.

手 shǒu ‘hand’; 腳 jiǎo ‘foot’:

Hands and feet are associated with the sense of touch and mobility. They serve as important means for individuals to explore the external world, thus establishing a close relationship with oneself. Consequently, they are more likely to combine directly with PP. Additionally, in Mandarin Chinese, ‘PP+hand/foot’ is commonly used to form prepositional phrases following prepositions, such as 在我手上 zài wǒ shǒu shàng ‘in my hands’ and 在我腳下 zài wǒ jiǎo xià ‘under my feet’.

父母 fùmǔ ‘parent’; 女兒 nǚ’ér ‘daughter’; 母親 mǔqīn ‘mother’; 媽媽 māma ‘mom’; 父親 fùqīn ‘father’; 兒子 érzi ‘son’:

These nouns represent family members and symbolize inseparable kinship, resulting in a tendency to omit de before them.

家庭 jiātíng ‘family’; 國家 guójiā ‘country’:

Both family and country convey a sense of collectivity. Given that Chinese culture places emphasis on close kinship and collectivism, the omission of de between PP and these nouns is more prevalent.

Nouns that prefer PP+DE+N can be classified into the following eight clusters:

爸爸 bàba ‘dad’; 哥哥 gēge ‘elder brother’:

In traditional Chinese culture, the roles of a father and an elder brother are similar. The saying ‘The elder brother is like a father’ emphasizes the need to respect one’s elder brother as one would respect their father. Consequently, dad and elder brother hold more authority and maintain a greater distance from other family members. This sense of distance necessitates the use of de before the nouns 爸爸 bàba’ and 哥哥 gēge.

孩子 háizi ‘child’:

The term ‘child’ is a general reference to both sons and daughters. Addressing someone as a child creates a greater sense of distance compared to directly addressing them as a son or daughter. Additionally, ‘child’ can be used to refer to younger boys and girls who do not share a kinship relationship with the speaker, further emphasizing the distance expressed by the term. These factors explain why de is more commonly used before 孩子 háizi in possessive constructions.

兄弟 xiōngdì ‘brother’:

The term ‘brother’ can be used to address friends, emphasizing personal loyalty. As a result, 兄弟 xiōngdì carries a greater distance from kindred relatives, making it more compatible with the use of de in possessive constructions.

耳朵 ěrduo ‘ear’; 眼睛 yǎnjīng ‘eye’:

People’s perception of sounds and images through their ears and eyes is rather general and does not necessarily reflect individuality or personalization. Therefore, 耳朵 ěrduǒ and 眼睛 yǎnjīng are not representative of a person’s inherent attributes and are more inclined to be preceded by de.

錢 qián ‘money’; 建議 jiànyì ‘suggestion’; 計畫 jìhuà ‘plan’:

These three nouns, regardless of their concreteness, can be transferred to others. As a result, they are distant from oneself and tend to be accompanied by de.

思想 sīxiǎng ‘thought’; 頭腦 tóunǎo ‘mind’:

Thoughts and the mind are more easily influenced than inherent attributes, making them more compatible with the use of de before them.

生命 shēngmìng ‘life’:

In Mandarin Chinese, ‘life’ can appear in phrases such as ‘offering one’s life’ or ‘sacrificing one’s life’. In these contexts, life acts as an object that can be transferred, creating a distance from oneself. Thus, de tends to appear between PP and 生命 shēngmìng to indicate such distance.

人 rén ‘people’:

‘PP+DE+人rén’ expresses subordinates of somebody. These subordinates take orders from their superior, with whom they maintain a greater distance. Therefore, de tends to appear between PP and ‘人rén’ to indicate this distance.

In summary, the random effect analysis of the noun reveals a correlation between the presence or omission of de and the distance between PP and the noun. John Haiman (1983: 782, 783) argues that ‘the linguistic distance between expressions corresponds to the conceptual distance between them’ and that ‘there is a closer conceptual link between a possessor and an inalienably possessed object than between a possessor and an alienably possessed object.’ While Mandarin Chinese may not have a clear distinction between alienability and inalienability in possessed relations, it adheres to the aforementioned principle by adding de to increase the linguistic distance between PP and N, thereby aligning with their greater conceptual distance.

4 Conclusions

Possession constructions are found in all languages, but they exhibit variations across different languages. This study employs mixed effects logistic regression to model the choice between two nearly synonymous possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: PP+DE+N and PP+N. The final model incorporates both linguistic (syntactic and semantic) and extralinguistic (register) factors as fixed or random effects. The analysis reveals that the selection of the two constructions is influenced by the following fixed effects: (1) the number of attributes preceding N; (2) the syntactic component of PP+(DE)+N; (3) the semantic relationship between PP and N; (4) the person of the PP; (5) the number of the PP; and (6) the style of the works in which PP+(DE)+N is used. Additionally, N is considered a random effect, determining the conceptual distance between PP and N.

Specifically, this study contributes to the understanding of the tendency for the presence or absence of de in possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese. Moreover, it offers a viable methodology for future research aiming to elucidate the reasons behind the formal marking of possessive constructions. For example, in English, possessive constructions are denoted by either the suffix s (Amy’s book, my book) or the preposition of (the book of Amy, the book of mine). These two forms of marking represent distinct tendencies and serve as key indicators in English possessive structures. The explanatory variables that assess fixed effects and the random effect in this study pertain to the analysis of English possessive constructions. By employing the methodology outlined in this study, researchers can quantify when English leans towards using the suffix s and when it leans towards favoring of. Furthermore, this approach can be adopted by researchers studying other languages to examine their own possessive constructions and conduct cross-linguistic comparisons. For instance, researchers can explore the preferred forms translators use to render possessive structures from a source language into a target language.

Lastly, further investigation can be conducted to explore whether the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N is influenced by highly frequent constructions that are conventional, deeply ingrained, and obscure the transparency of the entire constructions. This aspect has been mentioned in previous literature, for instance, Hollmann and Siewierska (2007: 420) conclude that ‘relatively high frequency (whether defined absolutely or relatively) of most combinations of possessive and kinship or body-part noun leads to reduction of the possessive pronoun.’

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [mixed-effects-model] repository, at https://github.com/Amy24680.

Abbreviations

- 1

-

the first person

- 2

-

the second person

- 3

-

the third person

- BCC

-

Beijing Language and Culture University Corpus Center

- cxn

-

construction choice

- COP

-

copula

- DE

-

genitive marker de

- GEN

-

genitive

- lit

-

literature

- m

-

middle; multiple

- MPC

-

Mandarin Chinese possessive constructions

- mixed models

-

mixed-effects models

- N

-

noun

- news

-

newspaper

- NP

-

noun phrase

- num_attr

-

number of attributes in the NP

- num_pp

-

number of the PP

- o

-

object

- pred

-

predicate

- prep

-

preposition

- pl

-

plural

- PP

-

personal pronoun

- s

-

subject

- sem_rel

-

semantic relationship

- sg

-

singular

- syn_comp

-

syntactic component

- VIF

-

variance inflation factor

References

Baayen, Rolf Harald. 2008. Analyzing linguistic data: A practical Introduction to statistics using R. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511801686Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Yu-Jie. 2008. The singularization of plural personal pronouns: A typological perspective. Language Teaching and Linguistic Studies. 39–46.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Alvin Cheng-Hsien. 2009. Corpus, lexicon, and construction: A quantitative corpus approach to Mandarin possessive construction. Paper Presented to the International Journal of Computational Linguistics & Chinese Language Processing 14. 3.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Zhenyu & Jingting Ye. 2014. From possession to stance: Juxtapositional possessive structures in Chinese involved a personal pronoun. Linguistic Sciences 13(2). 154–168.Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, Shuqiu. 2009. A Study on the priority sequences of multiple-attributive phrases in modern Chinese. Wuhan: Central China Normal University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2002. Typology and universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511840579Search in Google Scholar

Cui, Xiliang. 1992. The appearance/omission of “de” when personal pronouns modify nouns. Chinese Teaching in the World. 179–184.Search in Google Scholar

Dixon, Robert Malcolm Ward. 1979. Ergativity. Language 55(1). 59–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/412519.Search in Google Scholar

Dixon, Robert Malcolm Ward. 2010. Basic linguistic theory 2: Grammatical topics. New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Fang, Yinjie & Maocheng Liang. 2020. A study of relativizer omission by Chinese EFL learners: Triangulating corpus and experimental approaches. Foreign Languages and their Teaching. 34–43.Search in Google Scholar

Fang, Yu & Haitao Liu. 2021. Predicting syntactic choice in Mandarin Chinese: A corpus-based analysis of ba sentences and SVO sentences. Cognitive Linguistics 32(2). 219–250. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2020-0005.Search in Google Scholar

Haiman, John. 1983. Iconic and economic motivation. Language 59(4). 781–819. https://doi.org/10.2307/413373.Search in Google Scholar

Hollmann, Willem & Anna Siewierska. 2007. A construction grammar account of possessive constructions in Lancashire dialect: Some advantages and challenges. English Language and Linguistics 11(2). 407–424.10.1017/S1360674307002304Search in Google Scholar

Ji, Yinglin. 2020. The conceptualization of motion events by English–Chinese bilinguals: Evidence from behavioral tasks. Modern Foreign Languages 43(5). 654–666.Search in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1995. Possession and possessive constructions. In John R. Taylor & Robert E. MacLaury (eds.), Language and the cognitive Construal of the world, 51–80. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Levshina, Natalia, Dirk Geeraerts & Dirk Speelman. 2013. Towards a 3D-grammar: Interaction of linguistic and extralinguistic factors in the use of Dutch causative constructions. Journal of Pragmatics 52. 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.12.013.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Tianguang. 2012. The emergence/omission of de in modern Chinese unary attribute-head phrases. Social Science Forum. 97–102.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Charles N. & Sandra A. Thompson. 1981. Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.10.1525/9780520352858Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Bingfu. 2011. Heaviness-marking correspondence and the pragmatic and syntactic coding of functional motivations. Studies of the Chinese Language. 291–300.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Shiyi, Linɡyɑn Gao & Chen Lin. 2020. Online processing of patient subject construction NP+VP. Chinese Language Learning. 96–103.Search in Google Scholar

Pan, Tingting. 2021. The usage of de and subject-object asymmetry. Language Teaching and Linguistic Studies. 75–87.Search in Google Scholar

Qi, Jing & Hua Wang. 2020. The influence of input frequency and semantics on Chinese EFL learners’ acquisition of dative structure – analysis based on mixed-effects models. Foreign Language Education 41(2). 76–80.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Shiyu, Zheng Ma & Qingqing Hu. 2017. The development of lexical and conceptual representation in Chinese EFL learners: Evidence from mixed-effects linear modelling. Foreign Language Teaching and Research 49(5). 767–779.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, Yangchun. 2008. Further discussions on de’s usage in phrases with personal pronouns as modifiers. Studies of the Chinese Language. 21–27.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Min. 1998. Cognitive linguistics and Chinese noun phrases. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Weiwei, Dirk Speelman & Dirk Geeraerts. 2011. Variation in the (non)metonymic capital names in Mainland Chinese and Taiwan Chinese. Metaphor and the Social World 1(1). 90–112. https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.1.1.09zha.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Weiwei, Dirk Geeraerts & Dirk Speelman. 2018. (Non)metonymic expressions for government in Chinese: A mixed-effects logistic regression analysis. In Dirk Speelman, Kris Heylen & Dirk Geeraerts (eds.), Mixed-effects regression Models in linguistics, 117–146. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-69830-4_7Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Modelling the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: a mixed effects logistic regression approach

- Case-mismatching versus D-linking of ATB wh-questions in Korean

- Impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

- Developing awareness of Global Englishes: questioning the native-speakerist paradigm of ELT at a Polish university

- Continua and orientations of packing-repacking and unpacking ideational metaphor for knowledge construction

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Modelling the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: a mixed effects logistic regression approach

- Case-mismatching versus D-linking of ATB wh-questions in Korean

- Impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

- Developing awareness of Global Englishes: questioning the native-speakerist paradigm of ELT at a Polish university

- Continua and orientations of packing-repacking and unpacking ideational metaphor for knowledge construction