Abstract

Recent psycholinguistic research has demonstrated that structural priming can occur not only within linguistic cognition but also across different cognitive domains. However, the factors influencing cross-domain priming remain underexplored. This study aims to investigate the roles of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility in the priming from mathematical processing to L2 comprehension. Sixty-three Chinese college students learning English were recruited as participants. Simple mathematical expressions were presented as primes, and English sentences with relative clauses served as the targets. The participants were categorized based on their working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility. They processed mathematical expressions followed by an English sentence comprehension task to examine whether the processing of mathematical expressions influenced their comprehension of English relative clauses, which shared structural similarities with the mathematical expressions. The results revealed that (1) a priming effect existed from mathematical expressions to L2 sentence comprehension and (2) working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility significantly impacted the priming effect. These findings suggest that cross-domain structural priming is constrained by cognitive factors such as working memory, L2 proficiency and cognitive flexibility.

1 Introduction

Structural priming refers to the tendency in language production to repeat previously encountered structures (Bock 1986). In language comprehension, it manifests as a facilitative effect where prior processing experience improves the processing of similar structures (Branigan et al. 2005). Since its first observation by Bock (1986) in a laboratory setting, structural priming has become an important paradigm for investigating the representation of syntactic structures in the human mind. Initially, structural priming was applied to native language production and comprehension (Bock et al. 2007), but it has since been extended to second language (L2) acquisition and bilingual syntactic representations (Bernolet et al. 2013; Hartsuiker and Bernolet 2017).

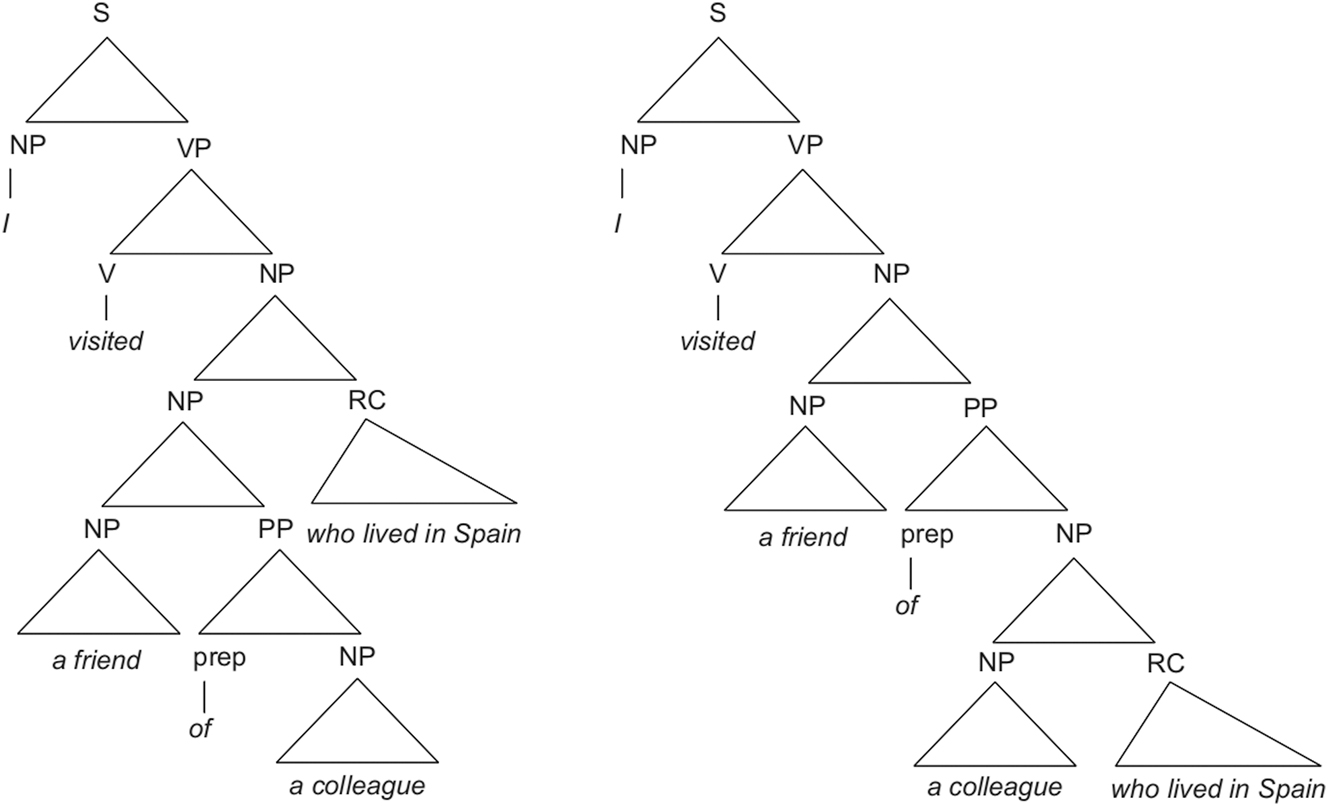

Recent studies have shown that structural priming occurs not only within the linguistic domain but also across different cognitive domains, such as between language and arithmetic (Scheepers et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2023), language and music (Cavey and Hartsuiker 2016), and language and visuo-spatial hierarchical structures (Mao 2020). Scheepers et al. (2011) introduced mathematical expressions into the priming paradigm, using them as primes and sentence fragments containing relative clauses as targets. Relative clauses are known for their potential ambiguity because they can attach to either a complex noun phrase or a simple noun phrase. For example, in the sentence I visited a friend of a colleague who lived in Spain, the relative clause who lived in Spain can either attach to the complex noun phrase a friend of a colleague , forming a high-attachment (HA) clause, or to the simple noun phrase a colleague, forming a low-attachment (LA) clause. Figure 1 shows the hierarchical structures of these two types of relative clauses.

Hierarchical structures representing the high-attachment (left) and low-attachment (right) interpretation of the relative clause in the sentence I visited a friend of a colleague who lived in Spain (Scheepers et al. 2011: 1320).

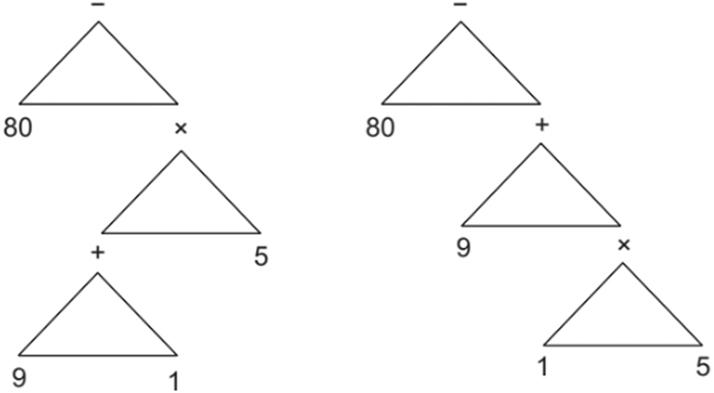

Mathematical expressions resemble English relative clauses in their hierarchical structure. For instance, the calculations 80 – (9 + 1) × 5 and 80 – 9 + 1 × 5 use the same numbers and operators but differ in how the multiplication operator links to other elements. In the former, the multiplication operator connects to the complex expression (9 + 1), similar to an HA relative clause modifying a complex noun phrase (NP + of + NP), while in the latter, the multiplication operator links to a single expression (1), resembling an LA relative clause modifying a simple noun phrase (NP). These structures are illustrated in Figure 2.

Hierarchical structures of mathematical expressions: 80 − (9 + 1) × 5 (left) and 80 − 9 + 1 × 5 (right) (Scheepers et al. 2011: 1321).

Scheepers et al. (2011) found that mathematical expressions could facilitate the production of structurally congruent relative clauses in native English speakers. Specifically, after completing an HA equation, native speakers tended to form HA relative clauses in the target sentences, while solving an LA equation led to more LA relative clauses. This indicates that mathematical expressions can prime syntactic structures in language production. Two theoretical explanations were proposed: the Representational Account and the Incremental-Procedural Account. The Representational Account suggests that the global structural configuration is what is primed and stored in memory. In contrast, the Incremental-Procedural Account posits that both mathematical and linguistic structures are processed incrementally from left to right, requiring structural revisions when encountering specific operators or syntactic markers.

Subsequent studies have confirmed cross-domain structural priming effects from mathematical expressions to linguistic expressions in various sentence structures (Scheepers and Sturt 2014) and across different languages (Zeng et al. 2021). This phenomenon has been observed in both native (Pozniak et al. 2018; Scheepers et al. 2019) and second language learners (Wang et al. 2023). However, as this research area has emerged only recently, further verification is necessary. Additionally, research on structural priming within the linguistic domain has found that the priming effects are influenced by factors such as working memory (Xu 2014), language proficiency (Yang et al. 2020), and verb form repetition (Tooley et al. 2019). Whether these factors also affect cross-domain structural priming remains unclear. Investigating this question will improve our understanding of the mechanisms behind cross-domain priming and the relationship between linguistic cognition and other cognitive abilities.

This study focuses on three factors: working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility. It aims to explore their roles in priming from mathematical expressions to L2 English sentence comprehension. The selection of these factors is based on the following theoretical foundations and research findings:

First, studies on cross-domain structural priming suggest that participants may repeatedly use the structure of the prime (i.e., the mathematical calculation) to complete relative clauses in the subsequent sentence task. This suggests that, during the calculation, participants store the hierarchical structure of the equation in working memory (Scheepers et al. 2011; Pozniak et al. 2018). Previous research indicates that working memory capacity plays a crucial role in structural priming within linguistic cognition (Xu 2014), and individuals with higher working memory capacity may be more likely to retain relevant structural representations long enough to activate them during the comprehension task. In contrast, individuals with lower working memory capacity may struggle to maintain these representations, resulting in weaker priming effects.

Second, studies on cross-linguistic structural priming have found that as learners acquire a second language, their representations of L2 syntactic structures evolve from language-specific patterns to abstract syntactic representations shared between their native and second languages (Hartsuiker and Bernolet 2017). Moreover, higher L2 proficiency has been associated with stronger between-language priming effects (Bernolet et al. 2013). Similarly, this study hypothesizes that mathematical expressions and L2 relative clauses may share abstract structural representations, and that learners with higher L2 proficiency will exhibit stronger cross-domain priming effects.

Third, structural priming is a form of syntactic repetition (Bock 1986), and repetitive behavior is influenced by cognitive flexibility, the ability to switch between tasks or rules (Chevalier and Blaye 2009). Individuals with higher cognitive flexibility can quickly suppress irrelevant rules and activate the relevant ones, while those with lower cognitive flexibility tend to show poorer task-switching performance (Liu et al. 2013). In this study, participants are required to switch between arithmetic and sentence comprehension tasks, and their ability to detect structural similarities between the tasks may depend on their level of cognitive flexibility.

In summary, this study investigates the impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming from mathematical processing to L2 sentence comprehension. Two main research questions are addressed:

Is there cross-domain structural priming from mathematical expressions to sentence comprehension of English relative clauses among Chinese college English learners?

How do working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility influence cross-domain structural priming?

2 The present study

2.1 Research design

This study aims to investigate the impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming from mathematical expressions to L2 sentence comprehension through a task-switching paradigm. The independent variables include prime conditions (a within-subjects variable) and working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility (between-subjects variables).The dependent variable is the reading time for each scoring region during the sentence comprehension task.

2.2 Participants

Sixty-three English learners from a Chinese teachers’ university participated in this study. Of these, 32 sophomores were randomly selected from parallel classes to form the lower-L2-proficiency group, while the remaining 31 students, all first-year graduate students, represented the higher-L2-proficiency group. To ensure a significant difference in L2 proficiency between the two groups, all participants completed a reading comprehension test from the Test for English Majors, Band 4 (TEM-4), a widely recognized English proficiency test in China. The results of an Independent Samples T-test confirmed a significant difference between the two groups in L2 proficiency, t (63) = 2.377, p = 0.021.

Participants were also required to take a working memory span test and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) to evaluate working memory and cognitive flexibility, respectively. The working memory test used was an adaptation of the reading span test developed by Daneman and Carpenter (1980), with materials from Harrington and Sawyer (1992). In this test, participants were presented with a series of unrelated sentences, each containing 11 to 13 words. These sentences were shown in progressively larger sets, starting with two sentences per set and increasing to five sentences. After reading each set, participants were required to recall the final words of each sentence and write them down. Additionally, a comprehension task was included following Swanson’s (1996) methodology, ensuring that participants actively engaged with the content of the sentences. Unlike tests that assess only storage capacity (e.g., digit span or word span tests), the reading span test evaluates both processing and storage resources of working memory, rather than simply the storage resources. Since a sentence comprehension task and an arithmetic task are involved in this study, we want to know whether individual differences in working memory influences the processing of sentences and arithmetic expressions. The reading span test serves as a tool for assessing the storage and processing functions involved in reading. It encompasses the typical demands of sentence comprehension, ranging from lower-level processes that encode the visual patterns of individual words and retrieve their meanings, to higher-level processes that analyze the semantic, syntactic, and referential relationships among successive words. When administered to college students, working memory spans ranged from two to five final words. The underlying theory, proposed by Daneman and Merikle (1996), posits that poor comprehenders devote so much cognitive capacity to understanding the sentences that they can only retain two or three of the final words.

The WCST was used to evaluate participants’ abstract reasoning and their ability to shift cognitive strategies in response to changing rules, which aligns with the experimental design of this study. In the WCST, participants were presented with four stimulus cards that varied in color, shape, and the number of shapes. They were asked to match additional cards to these stimuli, but were not informed about the sorting rules. Feedback on whether their sorting was correct or incorrect was provided after each attempt. Once a participant made six consecutive sorts, the sorting rule was changed without any indication. Participants were then required to discover the new sorting rule based on the feedback. The WCST reflects an individual’s ability to retain a rule in memory and adapt to a new rule when the previous one is deemed incorrect. Since this study seeks to explore individual differences in cognitive flexibility, the WCST was deemed appropriate for the research.

Based on their performance in the working memory capacity test, participants were divided into high- and low-working-memory groups. Using the median test method (Zhang 2010: 306), participants were dichotomously distributed into two groups through a 50 % percent split procedure, resulting in a high-working-memory group (31 students) and a low-working-memory group (32 students). An Independent Samples T-test revealed a significant difference between the two groups, t (63) = 16.13, p = 0.000.

Similarly, participants were divided into high- and low-cognitive-flexibility groups based on their WCST scores. The high-cognitive-flexibility group comprised 30 students, while the low-cognitive-flexibility group comprised 33 students. An Independent Samples T-test also confirmed a significant difference between these two groups, t (63) = 10.98, p = 0.000.

2.3 Materials

This study’s design closely followed that of prior research (Scheepers et al. 2011; Zeng et al. 2021), using 36 sets of materials, as shown in Table 1. Each set included a target sentence (an English relative clause) and one of three types of priming calculations: baseline (BL), HA, and LA. The priming calculations always yielded non-negative results and were simple enough to be solved without a calculator. BL calculations involved two numbers connected by a single operator and were considered neutral with respect to hierarchical structure. HA and LA calculations, by contrast, consisted of four numbers and three operators, with parentheses included in HA calculations but not in LA ones.

Example materials from the main experiment.

| Priming calculations | BL | 23 + 14 = |

| HA | 20 – (3 + 5) × 2 = | |

| LA | 20 – 3 + 5 × 2 = | |

| Target relative clauses | HA | The officials checked the earnings of the company that were obtained by unjust ways. |

| True or false question: The earnings of the company were obtained by just ways. | ||

| LA | Workers fix the doors of the house that has been built for 50 years. | |

| True or false question: The house has been built for 60 years. |

Target sentences contained a subject noun phrase, a verb, and a complex object noun phrase with a relative clause. The clauses were unambiguous and included both HA and LA structures equally. For example, in the earnings of the company that were obtained by unjust ways, the plural verb were signals that the clause attaches high to the earnings of the company. Filler items (26 sentences and 26 calculations) were also included, and true or false comprehension questions followed both target and filler sentences to ensure participants read attentively.

2.4 Procedure

The main experiment which included arithmetic calculation and sentence comprehension was conducted via E-prime 2.0 software and participants’ responses were automatically recorded into the computer. At the start, an equation appeared on the screen. The participant needed to calculate it in his/her mind and enter the result with the keyboard, to which a target sentence was displayed throughout their self-paced reading. The target sentence was divided into six regions (e.g., The officials checked/ the earnings of the company/ that/ were/ obtained/ by unjust ways). Participants read at their normal speed by pressing the space bar to read each region. At the time of each press, the currently read region changed back to a line and, in turn, the following region would appear. After the target sentence, a true or false question regarding its content was presented. “T” and “F” keys were used to represent the answers to the questions. The whole process of the participants’ proceeding through the reading regions was recorded with the E-prime software. During the experiment, priming calculations and target sentences appeared alternately, and the entire experiment lasted for about 25 min.

2.5 Data analysis

To analyze the priming results, the data were categorized based on the type of target sentences. One set included data where target sentences were disambiguated as HA targets, and the other set comprised data for LA targets. The analysis focused on the reading times of the target sentences, with two key scoring regions being examined (Hui and Liu 2012; Wei et al. 2019). The first region, referred to as the disambiguating region (Region 1), was the initial verb in the relative clause (e.g., were in that were obtained by unjust ways). This region is crucial because it serves as the point where the relative clause is disambiguated from the main clause structure, allowing participants to determine whether the target sentence is HA or LA.

The second region, referred to as the post-disambiguation region (Region 2), was the word immediately following the disambiguating region (e.g., obtained in that were obtained by unjust ways). This region was included in the analysis to account for potential spillover effects (Spivey-Knowlton and Sedivy 1995). These two regions were selected because, if structural priming was present, the processing of the target sentences would be facilitated, as reflected by reduced reading times in both regions. Specifically, since the hierarchical structure of HA calculations corresponds to that of HA relative clauses, and the hierarchical structure of LA calculations aligns with that of LA relative clauses, structural priming effects would be expected. Compared to the syntactically neutral BL prime condition, HA primes should enhance comprehension of HA targets, leading to shorter reading times in the HA relative clauses. Similarly, LA primes should facilitate comprehension of LA targets, reducing reading times in the LA relative clauses.

The data were further analyzed using linear mixed-effects models (LMEM) in R (Baayen et al. 2008). The lme4 package was employed to model the reading times for each scoring region, accounting for both by-participant and by-item random effects. A fully maximal version of each model was initially used. In cases where the model did not converge, random effects were progressively removed until convergence was achieved. Statistical significance for all effects was set at α = 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 The priming effects

Before analyzing the priming results, it was essential to first report the accuracy of the participants’ responses to the true or false questions and the priming calculations. Four participants performed poorly on the true or false questions, with an accuracy rate below 80 %, and their data were subsequently excluded from further analysis. For the remaining participants, the average accuracy on the true or false questions was 90 % and the accuracy for the priming calculations was 96 %. In cases where participants failed to correctly solve the priming calculations, their corresponding responses were also excluded, as only correctly solved calculations were considered valid prime-target pairs (Scheepers et al. 2011; Scheepers and Sturt 2014).

Additionally, reading times that were more than three standard deviations away from a participant’s overall mean reading time were excluded from the dataset to ensure the robustness of the results (Fukuta et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2014).

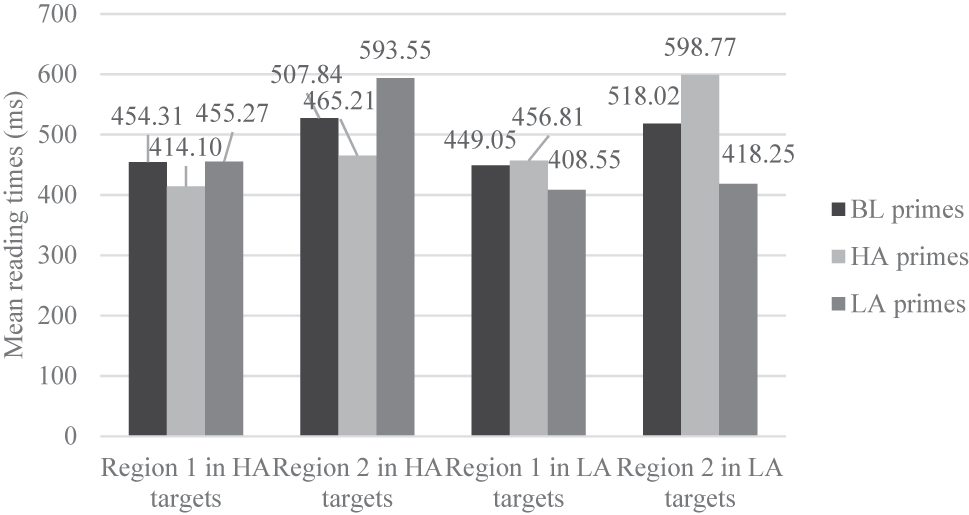

Figure 3 presents a summary of the reading times for each scoring region across different target conditions. As shown in the figure, participants spent the least amount of time reading the two scoring regions for HA targets when they were in the HA prime condition, while the longest reading times were observed in the LA prime condition. In contrast, when processing LA targets, participants read the two scoring regions much faster in the LA prime condition than in the other two conditions, with the slowest reading times occurring in the HA prime condition.

Mean reading times (ms) of each region.

Although differences in reading times were observed across the three prime conditions, LMEM were used to determine the statistical significance of these differences. The three different prime conditions were included as fixed effects, with the BL primes set as the reference condition.

The results, presented in Table 2, show that for both scoring regions in HA targets, the reading times in the HA prime condition were significantly shorter than those in the BL condition. Similarly, for LA targets, reading times in the LA prime condition were significantly reduced compared to the BL condition. Overall, these findings indicate that participants benefited from the facilitative effects of structurally congruent priming calculations. Thus, structural priming from mathematical expressions to English relative clauses was evident among Chinese English learners.

LMEM results for the priming effects.

| Scoring regions | Fixed effects | β | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 in HA targets | Intercept | 455.12 | 14.17 | 25.86 | 32.12 | < 0.001 |

| HA primes | −41.29 | 17.34 | 15.25 | −2.38 | 0.031 | |

| LA primes | −0.36 | 17.48 | 16.36 | −0.02 | 0.984 | |

| Region 2 in HA targets | Intercept | 507.69 | 14.73 | 151.58 | 34.48 | <0.001 |

| HA primes | −43.16 | 16.04 | 899.30 | −2.69 | 0.007 | |

| LA primes | 86.07 | 6.70 | 901.35 | 5.16 | < 0.001 | |

| Region 1 in LA targets | Intercept | 448.72 | 8.86 | 194.66 | 50.66 | < 0.001 |

| HA primes | 7.77 | 10.73 | 890.92 | 0.72 | 0.469 | |

| LA primes | −39.83 | 10.72 | 891.86 | −3.72 | <0.001 | |

| Region 2 in LA targets | Intercept | 515.16 | 34.19 | 6.38 | 15.07 | <0.001 |

| HA primes | −0.11 | 81.87 | 5.29 | −0.00 | 0.999 | |

| LA primes | −103.82 | 37.11 | 8.48 | −2.80 | 0.022 |

3.2 The impact of working memory

LMEM analyses were conducted to assess whether the priming effects were modulated by working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility. First, prime condition, working memory, and their interaction were included as fixed effects in the model, with BL primes and high working memory coded as the reference categories.

According to Table 3, for region 1 of the HA targets, the prime conditions had a significant effect: participants exhibited faster reading times during the HA prime condition compared to the BL prime condition. There was also a significant interaction between HA primes and working memory. Pair-wise comparisons using the emmeans package revealed that, compared to the BL prime condition, participants with high working memory read region 1 of the HA targets significantly faster during the HA prime condition. However, the difference for participants with low working memory did not reach statistical significance. This indicates that participants with high working memory were more responsive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations in region 1 of the HA targets compared to those with low working memory, resulting in larger priming effects (high working memory: Mean = 62; low working memory: Mean = 18).

LMEM results for the impact of working memory.

| Fixed effects | Region 1 in HA targets | Region 2 in HA targets | Region 1 in LA targets | Region 2 in LA targets | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Intercept | 467.81 | 20.08 | 23.29*** | 483.09 | 43.57 | 11.09*** | 452.02 | 18.83 | 24.01*** | 526.86 | 36.40 | 14.48*** |

| HA primes | −61.71 | 22.00 | −2.81* | −44.76 | 60.99 | −0.73 | −11.56 | 24.90 | −0.46 | −24.46 | 84.10 | −0.29 |

| LA primes | −8.73 | 23.20 | −0.38 | 111.57 | 60.94 | 1.83 (*) | −56.87 | 24.64 | −2.31* | −121.85 | 39.65 | −3.07* |

| WM | −26.75 | 24.88 | −1.08 | 7.48 | 25.18 | 0.30 | −13.77 | 17.87 | −0.77 | −25.16 | 27.17 | −0.93 |

| HA primes: WM | 43.90 | 21.87 | 2.01* | 66.69 | 29.65 | 2.25* | 35.89 | 21.23 | 1.69 (*) | 49.66 | 34.96 | 1.42 |

| LA primes: WM | 18.65 | 24.25 | 0.77 | 38.11 | 36.83 | 1.04 | 52.80 | 21.19 | 2.49* | 38.22 | 29.73 | 1.29 |

-

WM = working memory. *** indicates p < 0.001; ** indicates 0.001 < p < 0.01; * indicates 0.01 < p < 0.05; (*) indicates 0.05 < p < 0.01.

For region 2 of the HA targets, a significant interaction between HA primes and working memory was also found. The emmeans results showed that while the contrasts between the BL primes and HA primes did not reach significance for either group, participants with high working memory exhibited larger priming effects than those with low working memory (high working memory: Mean = 45; low working memory: Mean = −21).

In region 1 of the LA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect: participants read significantly faster during the LA prime condition compared to the BL condition. Moreover, there was a significant interaction between LA primes and working memory. Pair-wise comparisons indicated that compared to BL primes, participants with high working memory read region 1 of LA targets marginally faster in the LA prime condition. However, for participants with low working memory, the difference was not significant. This suggests that participants with high working memory were more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations in region 1 of LA targets (high working memory: Mean = 57; low working memory: Mean = 4).

For region 2 of the LA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect, with participants reading significantly faster in the LA prime condition than in the BL prime condition. Although there was no significant interaction between prime condition and working memory, the emmeans package was used to further explore differences between the groups. It was found that participants with high working memory read region 2 of the LA targets significantly faster during the LA prime condition compared to the BL prime condition. However, this contrast was not significant for participants with low working memory. These results indicate that participants with high working memory showed stronger sensitivity to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations in region 2 of LA targets (high working memory: Mean = 122; low working memory: Mean = 84).

Overall, the impact of working memory on the priming effects was significant for both types of target sentences. Specifically, participants with high working memory displayed larger priming effects than those with low working memory.

3.3 The impact of L2 proficiency

Following the initial data analysis, the prime condition, L2 proficiency, and their interaction were included as fixed effects in the model, with BL primes and high L2 proficiency coded as the reference categories. According to Table 4, for region 1 of HA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect: participants read significantly faster during the HA prime condition compared to the BL prime condition. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between HA primes and L2 proficiency. Pair-wise comparisons using the emmeans package showed that participants with high L2 proficiency read region 1 of HA targets significantly faster during the HA prime condition compared to the BL condition. However, the same contrast among participants with low L2 proficiency did not reach statistical significance. This indicates that participants with high L2 proficiency were more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations in region 1 of HA targets than those with low L2 proficiency, resulting in larger priming effects (high L2 proficiency: Mean = 76; low L2 proficiency: Mean = 6).

LMEM results for the impact of L2 proficiency.

| Fixed effects | Region 1 in HA targets | Region 2 in HA targets | Region 1 in LA targets | Region 2 in LA targets | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Intercept | 491.66 | 16.72 | 29.38*** | 492.73 | 47.76 | 10.32*** | 477.38 | 7.94 | 26.61*** | 519.41 | 31.53 | 16.47*** |

| HA primes | −75.80 | 16.71 | −4.54*** | −35.85 | 64.66 | −0.55 | −21.67 | 26.23 | −0.83 | −18.03 | 87.58 | −0.21 |

| LA primes | −40.85 | 17.54 | −2.33* | 111.70 | 62.83 | 1.78 (*) | −64.51 | 24.36 | −2.65* | −118.42 | 33.85 | −3.50** |

| LP | −74.15 | 23.44 | −3.16** | −5.33 | 28.31 | −0.19 | −62.95 | 16.21 | −3.88*** | −8.27 | 28.71 | −0.29 |

| HA primes: LP | 69.94 | 22.96 | 3.05** | 33.44 | 28.14 | 1.19 | 53.64 | 25.02 | 2.14* | 27.25 | 37.22 | 0.73 |

| LA primes: LP | 83.67 | 24.36 | 3.43** | 24.39 | 29.35 | 0.83 | 62.77 | 21.34 | 2.94** | 27.89 | 32.52 | 0.86 |

-

LP = L2 proficiency. *** indicates p < 0.001; ** indicates 0.001 < p < 0.01; * indicates 0.01 < p < 0.05; (*) indicates 0.05 < p < 0.01.

For region 2 of HA targets, no significant interaction between HA primes and L2 proficiency was observed. Pair-wise comparisons did not reach statistical significance either. However, participants with high L2 proficiency still showed larger priming effects than those with low L2 proficiency (high L2 proficiency: Mean = 36; low L2 proficiency: Mean = 2).

For region 1 of the LA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect with participants reading faster in the LA prime condition than in the BL prime condition. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between LA primes and L2 proficiency. Pair-wise comparisons revealed that participants with high L2 proficiency read region 1 of the LA targets significantly faster in the LA prime condition compared to the BL prime condition. However, the difference for participants with low L2 proficiency did not reach statistical significance. This indicates that participants with high L2 proficiency were more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations when reading region 1 of LA targets, resulting in larger priming effects (high L2 proficiency: Mean = 64; low L2 proficiency: Mean = 1).

For region 2 of the LA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect, with faster reading observed in the LA prime condition compared to the BL prime condition. Although no significant interaction between LA primes and L2 proficiency was found, the emmeans package was used to explore how the two groups (high and low L2 proficiency) differed. It was revealed that participants with high L2 proficiency read region 2 of the LA targets significantly faster in LA prime condition compared to the BL condition. However, the same contrast did not reach significance for participants with low L2 proficiency. Thus, participants with high L2 proficiency appeared to be more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations when reading region 2 of LA targets, showing larger priming effects compared to participants with low L2 proficiency (high L2 proficiency: Mean = 118; low L2 proficiency: Mean = 90).

In summary, the impact of L2 proficiency on the priming effects was significant in three of the scoring regions, except for region 2 of the HA targets. Overall, participants with high L2 proficiency demonstrated stronger priming effects than those with low L2 proficiency.

3.4 The impact of cognitive flexibility

Finally, the prime condition, cognitive flexibility, and their interaction were included as fixed effects in the model, with BL primes and high cognitive flexibility coded as the reference categories. According to Table 5, for region 1 of the HA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect, with participants reading significantly faster in the HA primes compared to the BL primes. There was also a significant interaction between HA primes and cognitive flexibility. Pair-wise comparisons using the emmeans package revealed that participants with high cognitive flexibility read region 1 of the HA targets significantly faster in the HA prime condition compared to BL conditions. However, this contrast did not reach statistical significance for participants with low cognitive flexibility. These findings indicate that participants with high cognitive flexibility were more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations when reading region 1 of HA targets, resulting in larger priming effects (high cognitive flexibility: Mean = 75; low cognitive flexibility: Mean = 15).

LMEM results for the impact of cognitive flexibility.

| Fixed effects | Region 1 in HA targets | Region 2 in HA targets | Region 1 in LA targets | Region 2 in LA targets | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Intercept | 486.06 | 23.35 | 20.82*** | 512.82 | 39.00 | 13.15*** | 479.37 | 17.53 | 27.35*** | 539.67 | 38.00 | 14.20*** |

| HA primes | −75.16 | 22.23 | −3.38** | −53.29 | 43.41 | −1.23 | −21.08 | 33.30 | −0.63 | 8.13 | 84.17 | 0.10 |

| LA primes | −35.72 | 23.28 | −1.53 | 139.66 | 83.60 | 1.67 | −71.32 | 20.22 | −3.53** | −121.93 | 40.62 | −3.00* |

| CF | −55.42 | 19.51 | −2.84** | −27.47 | 24.02 | −1.14 | −57.68 | 19.61 | −2.94** | −42.92 | 27.28 | −1.57 |

| HA primes: CF | 60.37 | 18.17 | 3.32*** | 37.69 | 28.00 | 1.35 | 42.66 | 29.36 | 1.45 | −16.39 | 35.45 | −0.46 |

| LA primes: CF | 64.45 | 18.94 | 3.40*** | −25.71 | 35.98 | −0.71 | 55.07 | 25.90 | 2.13* | 31.63 | 29.82 | 1.06 |

-

CF = cognitive flexibility. *** indicates p < 0.001; ** indicates 0.001 < p < 0.01; * indicates 0.01 < p < 0.05; (*) indicates 0.05 < p < 0.01.

For region 2 of the HA targets, no significant interaction between HA primes and L2 proficiency was observed, and pair-wise comparisons did not reach statistical significance either. Nonetheless, participants with high cognitive flexibility demonstrated larger priming effects than those with low cognitive flexibility (high cognitive flexibility: Mean = 53; low cognitive flexibility: Mean = 35).

For region 1 of the LA targets, the prime conditions indeed had a significant effect, with faster reading observed during LA primes compared to BL primes. There was a significant interaction between LA primes and cognitive flexibility. Pair-wise comparisons revealed that participants with high cognitive flexibility read region 1 of the LA targets significantly faster in the LA prime condition compared to BL condition. However, the contrast for participants with low cognitive flexibility did not reach statistical significance. These results suggest that participants with high cognitive flexibility were more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations when reading region 1 of LA targets, showing larger priming effects (high cognitive flexibility: Mean = 71; low cognitive flexibility: Mean = 17).

For region 2 of the LA targets, the prime condition had a significant effect, with participants reading faster during LA primes compared to BL primes. Though there was no significant interaction between LA primes and cognitive flexibility, the emmeans package was used to explore differences between the groups with high and low cognitive flexibility. It was found that participants with high cognitive flexibility read region 2 of the LA targets significantly faster in the LA prime condition compared to the BL condition. However, the contrast for participants with low cognitive flexibility did not reach statistical significance. These results suggest that participants with high cognitive flexibility were more sensitive to the facilitative effects of isomorphic priming calculations when reading region 2 of the LA targets, resulting in larger priming effects (high cognitive flexibility: Mean = 122; low cognitive flexibility: Mean = 91).

In summary, the impact of cognitive flexibility on the priming effects was significant in three scoring regions, except for region 2 of the HA targets. Overall, participants with high cognitive flexibility demonstrated larger priming effects than those with low cognitive flexibility.

4 Discussion

4.1 Structural priming from mathematical expressions to L2 relative clauses

Human cognition has traditionally been viewed as comprising a series of independent, specialized modules, each dedicated to a specific domain or processing mode (Collins 2005). Language, in particular, was once considered a highly modular cognitive system, functioning independently of other cognitive abilities (Fodor 1983). However, scholars have long debated whether language relies on dedicated cognitive and neural mechanisms or whether it shares cognitive resources with other domains, such as arithmetic, working memory, or even music. Some neurolinguistic studies have shown clear dissociations between linguistic and non-linguistic abilities (Amalric and Dehaene 2016; Fedorenko et al. 2011), while other neuroimaging studies suggest that brain regions that support language may also be involved in non-linguistic functions (Spelke and Tsivkin 2001; Varley et al. 2005).

While no consensus has been reached, evidence suggests that tasks involving hierarchically structured mathematical expressions may recruit brain regions that are either shared with or adjacent to those involved in linguistic tasks (Makuuchi et al. 2012; Varley et al. 2005). Behavioral research also provides substantial evidence of the interconnection between arithmetic and language (Cavey and Hartsuiker 2016; Scheepers et al. 2011). Among these studies, the structural priming paradigm is a widely used method to investigate the domain-generality of structural processing. In line with previous studies on cross-domain structural priming, this study also observed reliable structural priming from equation processing to structurally congruent sentence comprehension in L2 learners, as indicated by the reduced reading times in two scoring regions. Compared with BL prime condition, the reading times for HA targets were reduced in HA prime condition, and the reading times for LA targets were reduced in LA prime condition, suggesting that repeating hierarchical structures between primes and targets facilitates L2 comprehension.

Our findings align with previous studies on native speakers (Pozniak et al. 2018; Scheepers et al. 2011; Zeng et al. 2023). Two theoretical explanations have been proposed for such structural priming: the Representational Account and the Incremental-Procedural Account. The Representational Account suggests that the global configuration of the primed structure is retained in working memory and subsequently influences the comprehension of structurally similar target sentences (Scheepers et al. 2011). The Incremental-Procedural Account, on the other hand, posits that both mathematical expressions and linguistic structures are processed incrementally from left to right. Thus, solving a mathematical equation will activate the processing sequence of its hierarchical structure, which is then applied when reading a relative clause with temporary ambiguity (Scheepers et al. 2011).

Our study sheds light on the overlap in structural processing mechanisms and shared structural representations across domains, supporting the idea that domain-general abstract representations may be shared between mathematical and linguistic cognition. This finding also advances our understanding of cognitive modularity, suggesting that while human cognition may consist of specialized modules, the boundaries between these modules are not rigid. Under certain conditions, cognitive processes can transcend modularity, establishing connections between different domains at a more abstract level.

4.2 The impact of working memory on cross-domain structural priming

As demonstrated in this study, participants with high working memory capacity exhibited larger priming effects than those with low capacity. The Capacity Constrained Parsing Model (MacDonald et al. 1992) explains this difference by positing that working memory capacity influences an individual’s ability to retain multiple representations when processing sentences with syntactic ambiguity. Individuals with sufficient cognitive resources can maintain both possible representations while processing information, whereas those with limited resources are likely to select only one, typically the more preferred representation. This selection process increases processing costs when low-capacity individuals encounter less preferred interpretations.

In the present study, both high- and low-capacity participants displayed a preference for HA structures in the unambiguous relative clauses, as evidenced by shorter reading times for HA targets in BL prime condition. However, high-capacity participants exhibited stronger priming effects, particularly when processing LA targets. This difference may be attributed to the ability of high-capacity participants to store both possible interpretations of relative clauses, enabling them to retrieve the representation of the LA structure more easily. Low-capacity participants, on the other hand, may have experienced a greater processing load because they lacked the full representation of the LA structure.

Additionally, in cases where target relative clauses were disambiguated toward the more preferred HA structure, high-capacity groups still showed stronger priming effects. This may be due to their superior inhibitory control, allowing them to focus on relevant syntactic information while suppressing irrelevant details (Kane and Engle 2002). High-capacity participants could devote fewer cognitive resources to sentence comprehension, allowing them to pay more attention to the priming calculations and, in turn, retrieve more information about the primed structures.

The present study, to some extent, provides an answer to the major question in cognitive science concerning the nature and the functional organization of the working memory system, that is, whether there exist cognitive systems that are dedicated to specific cognitive functions, or whether the cognitive system is more domain-general in nature, such that the same cognitive resources are used for multiple cognitive functions. Our findings suggest that linguistic structures and mathematical expressions may rely on overlapping pools of working memory resources. Since working memory is a cognitive system with limited capacity, if arithmetical processing and language processing rely on shared resources, then syntactic integration in language should be more difficult when these limited resources are shared by the concurrent processing of arithmetic. As a result, a disruption due to the temporary ambiguity in a relative clause should be especially severe when that disruption is paired with a syntactically unexpected mathematical expression. This is reflected in the results that participants processed HA targets more slowly after finishing syntactically different LA priming expressions. In addition, the results that participants with different working memory capacity presented different priming effects suggest that working memory capacity can regulate the competition between different cognitive functions for working memory resources. Specifically, participants with high capacity can allocate and utilize their cognitive resources more effectively, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of cognitive processing, so they can process the information from different cognitive domains with greater flexibility and adaptability. Instead, when facing cases where working memory resources are needed during both the arithmetical and the language processing, participants with low capacity cannot have it both ways and have to focus more on one task, for example, paying more attention to the semantic and syntactic information of the target sentences but neglecting the syntactic information carried by the mathematical expressions.

These findings contribute to the ongoing debate about the nature and functional organization of working memory. They suggest that linguistic and mathematical structures may rely on overlapping working memory resources, and that individuals with higher working memory capacity are better equipped to allocate these resources effectively across multiple domains.

4.3 The impact of L2 proficiency on cross-domain structural priming

Our results indicate that L2 proficiency also plays a significant role in structural priming from mathematical expressions to L2 sentence comprehension. Participants with high L2 proficiency demonstrated stronger priming effects compared to those with low L2 proficiency. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the levels of abstraction at which participants represented English relative clauses. High-proficiency learners are more likely to have developed abstract syntactic representations that allow them to integrate information from both mathematical expressions and relative clauses.

According to Hartsuiker and Bernolet (2017), L2 acquisition begins with language-specific syntactic representations and evolves into abstract representations shared across languages.

The findings of this study suggest that L2 proficiency influences the extent to which learners can integrate representations from different cognitive domains. While both high- and low-proficiency participants demonstrated some priming effects, high-proficiency participants exhibited stronger effects, likely because they had developed more abstract representations of the hierarchical structures in both mathematical expressions and relative clauses.

Furthermore, in a cross-linguistic structural priming study, Bernolet et al. (2013) suggest that as learners are studying L2, their representations of L2 syntactic structures actually develop from language-specific patterns to abstract syntactic representations which are then shared by the native language and L2 as a whole. During the process of L2 acquisition, the level of L2 proficiency then affects the size of between-language priming effects, and according to this account, we can subsequently assume that the finding in the present study that L2 proficiency influences the strength of cross-domain priming effects is due to a similar reasoning. That is, L2 learners are going through a process in which their representations of equations and relative clauses actually evolve from separation to integration, and in this process, the priming effect changes with learners’ L2 proficiency throughout. Also, in the present study, the mean priming effect of the low- and high-proficiency groups are both positive. This means that low-proficiency participants have indeed reached a certain proficiency that shows structural priming, but high-proficiency participants can be considered closer to abstract representations of relative clauses. Thus, the integration of representations between calculations and relative clauses, both of which are composed of isomorphic hierarchical structures, is more likely to emerge among high-proficiency participants, so they resultantly yield a larger cross-domain priming effect. The observed correlation between higher L2 proficiency and stronger structural priming effects suggests that high-proficiency learners are likely to own developed cognitive flexibility, enabling them to manipulate abstract concepts across different domains. This indicates that their enhanced language skills are closely linked to advanced cognitive faculties. As learners develop language skills, they also hone their cognitive capacity, particularly in areas like abstraction, information-integration, and problem-solving. This interrelationship supports theories of cognitive linguistics that language is a reflection of cognitive processes. Consequently, improvements in one domain (language) can lead to enhancements in the other (cognition).

Given the interconnectedness of language skills and cognitive abilities, incorporating various cognitive activities, such as arithmetic, within language learning can help foster overall cognitive development. By linking language tasks to mathematical concepts, educators can enhance students’ cognitive flexibility, facilitating their ability to transfer knowledge across different domains.

The relationship between L2 proficiency and cognitive flexibility also emerged as an important factor. High-proficiency learners may have enhanced cognitive abilities, allowing them to manipulate abstract concepts across different domains more effectively. This finding aligns with theories of cognitive linguistics, which posit that language is a reflection of broader cognitive processes.

4.4 The impact of cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

Participants with high cognitive flexibility exhibited stronger priming effects compared to those with low flexibility. Cognitive flexibility, particularly the ability to inhibit irrelevant information, plays a crucial role in adapting to new rules and switching between tasks (Kim et al. 2011; Munakata 2001). The larger priming effects observed in high-flexibility participants can be explained by their ability to quickly switch between rules when solving mathematical equations and processing relative clauses.

In this study, there were three types of priming calculations and two types of target relative clauses, so there were 6 pair-wise combinations in total, including BL primes-HA targets, HA primes-HA targets, LA primes-HA targets, BL primes-LA targets, HA primes-LA targets, and LA primes-LA targets. Moreover, these 6 kinds of combinations appeared randomly in the experiment, so the rules employed to solve the priming calculations or to disambiguate the target sentences were alternating all the time. Also, in order to make full use of the priming effect from calculations, participants were allowed to neatly switch to new rules whenever the switches were needed. Therefore, the larger priming effect of the high cognitive flexibility group can be subsequently explained by their need for strong switching which allowed fast reactions to the previous rules that decided whether to perseverate or to inhibit them. Conversely, participants with low cognitive flexibility could not adapt to new rules as quickly as those with high flexibility and reacted slowly to the previous rules, to which they received fewer effective priming effects from the preceding calculations overall.

The result of the present study can also be explained by the task-set inertia theory (Allport and Wylie 1999). According to such theory, when participants execute a difficult task (i.e., where the task-set has not been established), they inevitably suppress the easy task in which the task-set has been already established. Thus, in terms of the present study, finishing the difficult trials, in which the hierarchical structures of the primes and the targets were inconsistent, saw a form of inhibition produced throughout the easy trials in which the hierarchical structures were in turn seen to be consistent. Therefore, when dealing with inconsistent trials, consistent ones needed to be suppressed, and when alternating from inconsistent trials to consistent ones, the disinhibition of consistent trials were recruited from cognitive flexibility itself. Also, in order to more accurately explain the role of cognitive flexibility, we needed to combine the inhibitory control theory with the task-set inertia theory. According to these two theories, to retrieve the desired information, the interference from previously irrelevant information needs to be suppressed, and to which the now relevant information associated with the previously inhibited one can also be reactivated. Hence, the amount of inhibition will constantly change according to what kind of information is needed. As a consequence, participants with different cognitive flexibility also showed different levels of inhibitory control for their previous information as well as different levels of abilities that could successfully apply useful information in the preceding calculations to the subsequent sentence comprehension produced, thus showing different priming effects on the whole.

These results highlight the importance of cognitive flexibility in cross-domain learning and provide a theoretical foundation for educational practices. By fostering environments that encourage flexibility and interdisciplinary learning, educators can help students transfer knowledge across domains and enhance their overall cognitive development.

5 Conclusions

This study investigated the factors influencing cross-domain structural priming from mathematical expressions to L2 sentence comprehension, focusing on the roles of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility. The results indicate that all the three factors significantly impact the priming effect. These findings provide further evidence for the universality of cross-domain structural priming and, more importantly, shed light on its underlying mechanisms by demonstrating that such priming is constrained by cognitive factors like working memory, L2 proficiency and cognitive flexibility. However, this study is a preliminary investigation, and future research is needed to further verify these results. Expanding the scope of research could provide deeper insights into the interaction between different cognitive domains and the factors that influence cross-domain priming.

Funding source: Social Science and Humanities Planned Project of Fujian Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: FJ2022B043

-

Research funding: This work was funded by Social Science and Humanities Planned Project of Fujian Province (Award No.: FJ2022B043).

References

Allport, Alan & Glenn Wylie. 1999. Task-switching: Positive and negative priming of task-set. In Glyn W. Humphreys, John Duncan & Anne Treisman (eds.), Attention, space and action: Studies in cognitive neuroscience, 273–296. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198524694.003.0016Search in Google Scholar

Amalric, Marie & Stanislas Dehaene. 2016. Origins of the brain networks for advanced mathematics in expert mathematicians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(18). 4909–4917. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1603205113.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Harald, J. Davidson Douglas & Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 59(4). 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bernolet, Sarah, Robert J. Hartsuiker & Martin J. Pickering. 2013. From language-specific to shared syntactic representations: The influence of second language proficiency on syntactic sharing in bilinguals. Cognition 127. 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.02.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bock, Kathryn. 1986. Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology 18. 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(86)90004-6.Search in Google Scholar

Bock, Kathryn, Gary S. Dell, Franklin Chang & Kristine H. Onishi. 2007. Persistent structural priming from language comprehension to language production. Cognition 104. 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

Branigan, Holly P., Martin J. Pickering & Janet F. Mclean. 2005. Priming prepositional-phrase attachment during comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 31(3). 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.31.3.468.Search in Google Scholar

Cavey, Joris V. D. & Robert J. Hartsuiker. 2016. Is there a domain-general cognitive structuring system? Evidence from structural priming across music, math, action descriptions, and language. Cognition 146. 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.09.013.Search in Google Scholar

Chevalier, Nicolas & Agnés Blaye. 2009. Setting goals to switch between tasks: Effect of cue transparency on children’s cognitive flexibility. Developmental Psychology 45(3). 782–797. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015409.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, John. 2005. On the input problem for massive modularity. Minds and Machines 15(1). 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-004-1346-5.Search in Google Scholar

Daneman, Meredyth & Patricia A. Carpenter. 1980. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 19. 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5371(80)90312-6.Search in Google Scholar

Daneman, Meredyth & Philip M. Merikle. 1996. Working memory and language comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 3(4). 422–433. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03214546.Search in Google Scholar

Fedorenko, Evelina, Michael K. Behr & Nancy Kanwisher. 2011. Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108(28). 16428–16433. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112937108.Search in Google Scholar

Fodor, Jerry A. 1983. The modularity of mind: An essay on faculty psychology. Cambridge: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4737.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Fukuta, Junya, Aki Goto, Yusaku Kawaguchi, Daisuke Murota & Akari Kurita. 2015. Japanese EFL learners’ implicit knowledge and algorithmic processing of dative alternation: Perspective from syntactic priming in reading comprehension. Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan 26. 221–236.Search in Google Scholar

Harrington, Michael & Mark Sawyer. 1992. L2 Working memory capacity and L2 reading skill. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 14(1). 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263100010457.Search in Google Scholar

Hartsuiker, Robert J. & Sarah Bernolet. 2017. The development of shared syntax in second language learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20(2). 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728915000164.Search in Google Scholar

Hui, Kun & Ming Liu. 2012. Syntactic priming during English sentence comprehension in proficient Chinese learners of English. Journal of South China Normal University 5. 121–125.Search in Google Scholar

Kane, Michael J. & Randall W. Engle. 2002. The role of prefrontal cortex in working-memory capacity, executive attention, and general fluid intelligence: An individual differences perspective. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 9(4). 637–671. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03196323.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Christina S., Kathleen M. Carbary & Michael K. Tanenhaus. 2014. Syntactic priming without lexical overlap in reading comprehension. Language and Speech 57(2). 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830913496052.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Chobok, Nathan F. Johnson, Sara E. Cilles & Brian T. Gold. 2011. Common and distinct mechanisms of cognitive flexibility in prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 31(13). 4771–4779. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5923-10.2011.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Huanhuan, Ning Fan, Xiangying Shen & Jiangye Ji. 2013. Effect of cognitive flexibility on language switching in non-proficient bilinguals: An ERPs study. Acta Psychologica Sinica 45(6). 636–648. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1041.2013.00636.Search in Google Scholar

MacDonald, Maryellen C., Marcel A. Just & Patricia A. Carpenter. 1992. Working memory constraints on the processing of syntactic ambiguity. Cognitive Psychology 24. 56–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(92)90003-k.Search in Google Scholar

Mao, Wen. 2020. A study on cross-domain structural priming. Changsha, Hunan Province: Hunan University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Makuuchi, Michiru, Jörg Bahlmann & Angela D. Friederici. 2012. An approach to separating the levels of hierarchicalstructure building in language and mathematics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 367. 2033–2045. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0095.Search in Google Scholar

Munakata, Yuko. 2001. Graded representations in behavioral dissociations. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 5(7). 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01682-x.Search in Google Scholar

Pozniak, Céline, Barbara Hemforth & Christoph Scheepers. 2018. Cross-domain priming from mathematics to relative-clause attachment: A visual-world study in French. Frontiers in Psychology 9. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02056.Search in Google Scholar

Scheepers, Christoph, Anastasia Galkina, Yury Shtyrov & Andriy Myachykov. 2019. Hierarchical structure priming from mathematics to two- and three-site relative clause attachment. Cognition 189. 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.03.021.Search in Google Scholar

Scheepers, Christoph & Patrick Sturt. 2014. Bidirectional syntactic priming across cognitive domains: From arithmetic to language and back. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 67(8). 1643–1654. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2013.873815.Search in Google Scholar

Scheepers, Christoph, Patrick Sturt, Catherine J. Martin, Andriy Myachykov, Teevan Kay & Izabela Viskupova. 2011. Structural priming across cognitive domains: From simple arithmetic to relative clause attachment. Psychological Science 22(10). 1319–1326.33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611416997.Search in Google Scholar

Spelke, Elizabeth S. & Sanna Tsivkin. 2001. Language and number: A bilingual training study. Cognition 78(1). 45–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00108-6.Search in Google Scholar

Spivey-Knowlton, Michael & Julie C. Sedivy. 1995. Resolving attachment ambiguities with multiple constraints. Cognition 55. 227–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(94)00647-4.Search in Google Scholar

Swanson, H. Lee. 1996. Individual and age-related differences inchildren’s working memory. Memory & Cognition 24(1). 70–82. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03197273.Search in Google Scholar

Tooley, Kristen M., Martin J. Pickering & Matthew J. Traxler. 2019. Lexically-mediated syntactic priming effects in comprehension: Sources of facilitation. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 72(9). 2176–2196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021819834247.Search in Google Scholar

Varley, Rosemary A., Nicolai J. C. Klessinger, Charles A. J. Romanowski & Michael Siegal. 2005. Agrammatic but numerate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102(9). 3519–3524. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0407470102.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Baochang, Wenrong Lei & Rongbao Li. 2023. Structural priming across cognitive domains: From mathematical expressions to L2 relative clauses. Journal of Foreign Languages 46(2). 13–23.Search in Google Scholar

Wei, Hang, Julie E. Boland, Zhenguang Cai, Fang Yuan & Min Wang. 2019. Persistent structural priming during online second language comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition 45(2). 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000584.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, Hao. 2014. Exploring the impact of working memory and second language proficiency on cross-language priming effects. Foreign Language Teaching and Research 46(3). 412–422.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, Kun, Min Wang & Wei Xing. 2020. The developmental trajectory of unbalanced bilinguals’ L2 syntactic representations: Evidence from structural priming. Foreign Language Teaching and Research 52(6). 906–918.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Minqiang. 2010. Educational and psychological statistics. Beijing: People’s Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

Zeng, Tao, Mao Wen & Yarong Gao. 2023. An eye-tracking study of structural priming from abstract arithmetic to Chinese structure NP1+You+NP2+Hen+AP. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 52(1). 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-021-09819-7.Search in Google Scholar

Zeng, Tao, Yating Mu & Taoyan Zhu. 2021. Structural priming from simple arithmetic to Chinese ambiguous structures: Evidence from eye movement. Cognitive Processing 22. 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-020-01003-4.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2023-0071).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Modelling the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: a mixed effects logistic regression approach

- Case-mismatching versus D-linking of ATB wh-questions in Korean

- Impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

- Developing awareness of Global Englishes: questioning the native-speakerist paradigm of ELT at a Polish university

- Continua and orientations of packing-repacking and unpacking ideational metaphor for knowledge construction

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Modelling the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: a mixed effects logistic regression approach

- Case-mismatching versus D-linking of ATB wh-questions in Korean

- Impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

- Developing awareness of Global Englishes: questioning the native-speakerist paradigm of ELT at a Polish university

- Continua and orientations of packing-repacking and unpacking ideational metaphor for knowledge construction