Abstract

This study explores how conjunct locus and D(iscourse)-linking can improve the acceptability of Korean across-the-board (ATB) wh-questions that violate the case-match requirement of wh-fillers. A 2 × 2 design is employed – involving Korean ATB wh-questions with the first-conjunct or second-conjunct case-mismatches and with bare or D-linked wh-phrases. The results show that the first-conjunct case-licensing of a wh-filler is crucial when the wh-filler is bare, as reconstruction into the first conjunct is allowed while reconstruction into the second is not. Meanwhile, the first-conjunct case-licensing of a wh-filler is not crucial when the wh-filler is D-linked. More precisely, D-linking improves the acceptability of syntactically ill-formed ATB wh-questions which violate the first-conjunct case-licensing requirement of a wh-filler, but it does not improve the acceptability of syntactically well-formed ATB wh-questions. These results thus suggest that the amelioration effect of D-linking only occurs as a last resort when the acceptability of ATB wh-questions is degraded due to a violation of certain grammatical principles.

1 Introduction

Since Ross (1967), it has been established that coordinate structures follow the Coordinate Structure Constraint (CSC), which states that extraction from coordinate structures is not permitted when only one conjunct is involved:

| *Who did [John love __ and Bill hate Susan]? |

| *Who did [John love Mary and Bill hate __ ]? |

In contrast, it is possible to extract elements across multiple clauses or phrases in coordinate structures, known as across-the-board (ATB) extraction (Ross 1967):

| Who did [John love __ and Bill hate __ ]? |

It has been observed that the morphological case of a wh-filler in ATB wh-questions must match across all the conjuncts (Citko 2003; Dyła 1984; Franks 1993, 1995], etc.). This observation is illustrated by the following examples in Polish:[1]

| Co | Jan | lubi | __ | i | Maria | uwielbia | __? |

| whatAcc | Jan | likesAcc | and | Maria | adoresAcc | ||

| ‘What does Jan like and Maria adore?’ | |||||||

| *Co | Jan | lubi | __ | i | Maria | nienawidzi | __? |

| whatAcc | Jan | likesAcc | and | Maria | hatesGen | ||

| ‘What does Jan like and Maria hate?’ (Citko 2003: 89) | |||||||

In (3), the verbs lubić ‘to like’ and uwielbia ‘to adore’ assign accusative case, while the verb nienawidzić ‘to hate’ assigns genitive case. The wh-filler in coordination must match in case types, as shown by the contrast between (3a) and (3b).

However, it has been observed that Korean permits a case mismatch between wh-fillers under ATB dependency:

| Nwukwu-eykey | John-i | __ | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| who-Dat | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | giveDat-and | |

| Mary-ka | ttattushakey | __ | macihayss-ni? | |

| Mary-Nom | heartily | welcomedAcc-Q | ||

| ‘To whom did John give flowers, and Mary heartily welcome?’ | ||||

Kim et al. (2023) report that the example in (4) is grammatical although the different case-assignment properties of the Korean verbs cwu(ta) ‘to give’ (assigning dative case) and maciha(ta) ‘to welcome’ (assigning accusative case) slightly degrade the acceptability of the example. In this light, this study empirically investigates the case-mismatching property of Korean ATB wh-questions.

The other concern of this study is to examine the nature of D(iscourse)-linking. Consider the following:

| Which problem did you solve __? |

| What did you solve __? |

According to Pesetsky (1987), some wh-phrases such as which problem are considered D-linked because they naturally lead to an answer from a set of referents already established in the discourse, whereas other wh-phrases such as what are not. Example (5a) is assumed to be asking about a set of problems already familiar to the speaker and the hearer, while (5b) does not have such an assumption in its most natural interpretation.

The distinction between D-linked and bare wh-phrases has been claimed to have an important consequence for the syntax of wh-dependencies. The consequence relates to the gaps that are necessarily associated with wh-fillers. These gaps are not allowed in certain parts of a sentence, which is known as an island effect, as described by Ross (1967). An example of an island environment, a wh-island, is shown in (6a), whereas (6b) shows a non-island environment where a gap is permitted.

| *What do you wonder [who solved __ ]? |

| What do you think [that John solved __ ]? |

Island effects are thought to be less strong when the wh-phrase is D-linked. This has been observed by several linguists (Cinque 1990; Kiss 1993; Rizzi 1990, etc.):

| ?Which problem do you wonder [who solved __ ]? |

This outcome is seemingly surprising because wh-dependency is commonly viewed as a syntactic phenomenon, yet it is influenced by discourse-related factors.

Considering this, the second issue to be explored is whether D-linking has an amelioration effect on the case-mismatch in Korean ATB wh-questions as follows:

| Enu | nala-uy | haksayng-eykey | John-i | __ | kkochtapal-ul | ||

| which | country-Gen | student-Dat | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | |||

| cwu-ko, | Mary-ka | ttattushakey | __ | macihayss-ni? | |||

| give-and | Mary-Nom | heartily | welcomed-Q | ||||

| ‘To which country’s student did John give flowers, and Mary heartily welcome?’ | |||||||

| Enu | nala-uy | haksayng-eykey | Mary-ka | ttattushakey | __ |

| which | country-Gen | student-Dat | Mary-Nom | heartily | |

| machiha-ko, | John-i | __ | kkochtapal-ul | cwuess-ni? | |

| welcome-and | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | gave-Q | ||

| ‘To which country’s student did Mary heartily welcome and John give flowers?’ | |||||

If D-linking generally reduces the impact of grammatical rule violations, it is reasonable to assume that D-linking might also increase the acceptability of ATB wh-questions that contain case mismatches.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2.1 presents the theoretical background of ATB wh-questions and their (a)symmetric properties, while Section 2.2 discusses previous approaches to ATB wh-dependency. Section 2.3 reviews previous analyses of left-node-raising in Korean (and Japanese) with reference to case-mismatching. Section 2.4 examines two popular approaches to D-linking – the syntactic approach and the working memory approach – and evaluates which approach better predicts the amelioration effect of case-mismatches in ATB dependency. In Section 3, the design, materials, and outcomes of a formal experiment are detailed, revealing that Korean ATB wh-questions sometimes permit the case-mismatch of wh-fillers. Section 4 discusses the implications of our acceptability judgment test results for the analyses of ATB wh-questions, particularly supporting the parasitic gap approach. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Background

2.1 Asymmetric ATB wh-questions

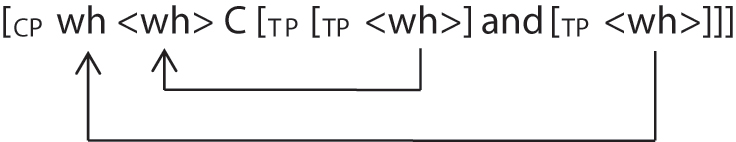

ATB constructions are characterized by an asymmetric dependency involving one landing site and two (or more) extraction sites (Ross 1967; Williams 1978). A central issue in ATB dependencies is to understand how the movement of two (or more) elements can result in a single filler. One approach to analyzing ATB wh-movement is illustrated below (with elided material shown in angle brackets):

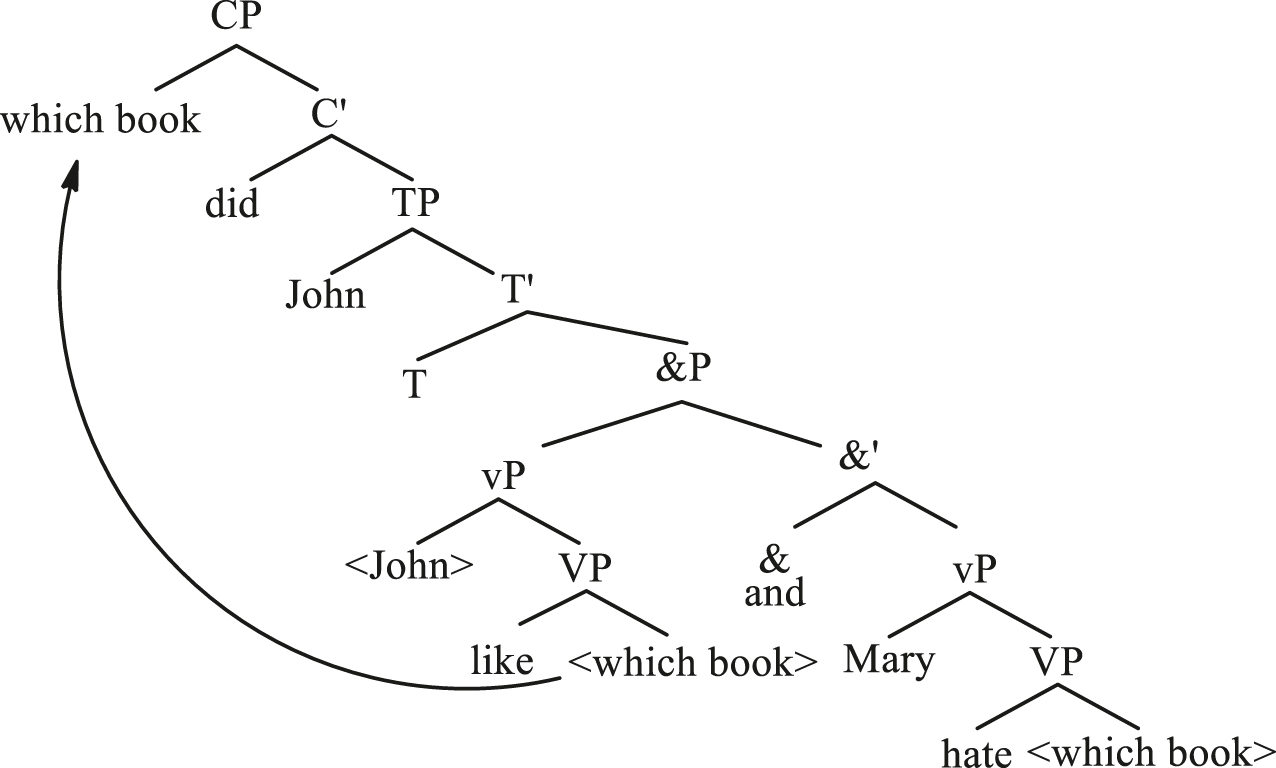

|

In (9), the two distinct wh-phrases are extracted from each conjunct. To create the one-to-many relationship between the wh-filler and the corresponding gaps, one of these wh-phrases is deleted at the PF level. This deletion must be mandatory, which is unusual since PF deletion is typically optional.

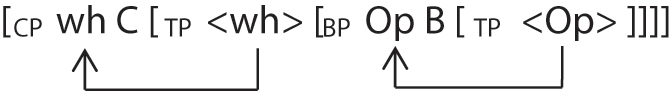

Several linguists have proposed that the conjunction head has its own projection, such as Boolean Phrase, Conjunction Phrase, or &P (Johannessen 1998; Kayne 1994; Munn 1993; Zoerner 1995, among others). For example, Munn (1993, 2001] suggests that ATB wh-questions can be analyzed as a type of parasitic gap construction, where one conjunct undergoes wh-movement, while the other conjunct undergoes null operator (Op) movement. In this view, conjunctions are functional heads that take the second conjunct as their complement and project to a Boolean Phrase (BP), with the entire BP then being adjoined to the first conjunct:[2]

|

According to Munn, the identification of the null operator by the overt operator is enabled by the overt operator’s licensing of the null operator, which necessitates case agreement (cf. Franks 1993, 1995]). It is thus likely that the different case morphology between the overt wh-operator and the null operator lowers the acceptability of ATB wh-questions. However, this case agreement is not mandatory in all instances, as it is possible to have case mismatches between the licenser and the null operator in relative clauses or tough constructions, unlike in ATB dependency:

| The manNom [OpAcc Mary is seeing __ ] is my brother. |

| JohnNom is easy [OpAcc PRO to please __ ]. (Citko 2003: 94) |

As is widely known, certain types of ATB wh-questions require symmetric reconstruction in coordinate structures. For instance, the wh-filler of ATB questions cannot cross over a coindexed pronoun that appears in both conjuncts:

| *[Whose1 mother] did [we talk to __ ] and [he1 never visit __ ]? |

| *[Whose1 mother] did [he1 never visit __ ] and [we talk to __ ]? (Citko 2005: 492) |

The ungrammatical status of (12) suggests that the principle of strong crossover necessitates the ATB-moved wh-filler to be reconstructed symmetrically into both conjuncts.[3]

On the other hand, asymmetric reconstruction occurs when there is reconstruction into the first conjunct but not into the second conjunct with respect to the following examples for Principle C (13), for weak crossover (14), or for anaphor binding (15). This has been called a proximity effect (Williams 1990):

| Which picture of John1 did Mary like and he1 dislike? |

| *Which picture of John1 did he1 like and Mary dislike? (Citko 2003: 101) |

| Which man1 did you hire and his1 boss fire? |

| *Which man1 did his1 boss fire and you hire? (Munn 2001: 374) |

| Which picture of himself1 did John1 sell and Mary buy? |

| *Which pictures of himself1 did Mary sell and John1 buy? (Citko 2003: 100) |

For instance, the LFs of (13) would be represented as in (16).

| [past] Mary like <which picture of John1> and he1 dislike |

| [past] he1 like <which picture of John1> and Mary dislike |

As shown in (16a), (13a) is expected to be grammatical because the fronted wh-filler is reconstructed into the first conjunct. However, (13b) is not grammatical because it violates Principle C when the fronted wh-filler is reconstructed into the first conjunct as in (16b). If the fronted wh-filler were to be reconstructed into the second conjunct, the contrast between (13a) and (13b) could not be captured. In short, reconstruction may occur only into the first conjunct but cannot only into the second conjunct.

2.2 Previous analyses

Several theories of ATB movement have been proposed in the literature, which can broadly be categorized into two main approaches: symmetric and asymmetric. Symmetric approaches assume that extraction occurs from both conjuncts in parallel, while asymmetric approaches posit that genuine extraction happens only from one conjunct, with the other gap not directly related to movement. In this section, we will explore three different analyses of ATB wh-questions: sideward movement, multidominance, and parasitic gap.

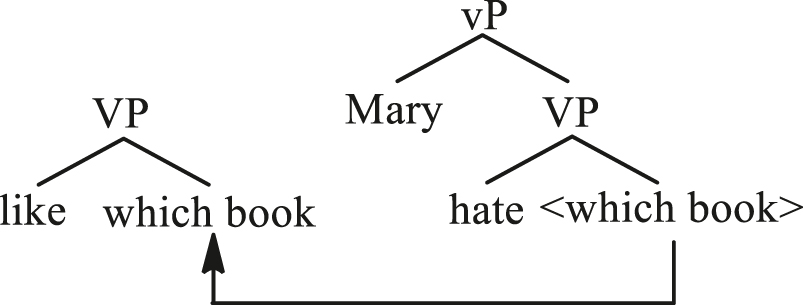

First, Nunes (2004) presents an analysis that permits a constituent to move into an “unconnected workspace” (i.e., a separate syntactic domain of the local tree) via a copy operation. This allows for ATB dependency to be formed in the following way:

| Which book did John like and Mary hate? |

| sideward movement from a workspace to another workspace |

|

| two vPs form a conjunction in the same workspace |

|

| wh-movement from the first conjunct |

|

As illustrated in (18a), the wh-phrase initially merges within the second conjunct, which is constructed in its own workspace. It then moves sideward (rather than upward) to the unconnected first conjunct, which is created in a separate workspace. Sideward movement is a unique operation that involves copying a constituent from one phrase marker to a different, unconnected phrase marker. This type of copying is possible when the initial numeration lacks sufficient elements to fulfill the lexical requirements of other predicates or to maintain parallelism. In a subsequent step, the two vPs are conjoined within the same workspace, as shown in (18b). Finally, the wh-phrase in the first conjunct undergoes operator movement to Spec of CP. For the purpose of linearization, the two copies (i.e., one within the first conjunct and the other within the second conjunct) of the wh-operator should be deleted via chain reduction.

This approach is partly symmetric as extraction occurs from both conjuncts, but also partly asymmetric as movement to Spec of CP proceeds only from the first conjunct. Due to this dual nature, it is debated whether this approach can adequately explain the asymmetric reconstruction effects observed in (13), (14), and (15). As a reviewer pointed out, if sideward movement is considered a form of successive cyclic movement and reconstruction to an intermediate position is possible, this approach might predict that asymmetric reconstruction to the first conjunct could occur.

Now, consider a case where the wh-phrase merges in the first conjunct and then undergoes sideward movement to the second conjunct. After the two conjuncts form a conjunction phrase, the wh-phrase in the second conjunct may undergo wh-movement to Spec of CP. If reconstruction to the intermediate position occurs in this scenario, it should target the second conjunct. To avoid this outcome, the approach might rely on a specific conjunction process, such as Boolean conjunction. However, this approach faces several technical challenges, particularly concerning cyclicity and activity in relation to the Agree mechanism (Fernández-Salgueiro 2008; Salzmann 2012a).

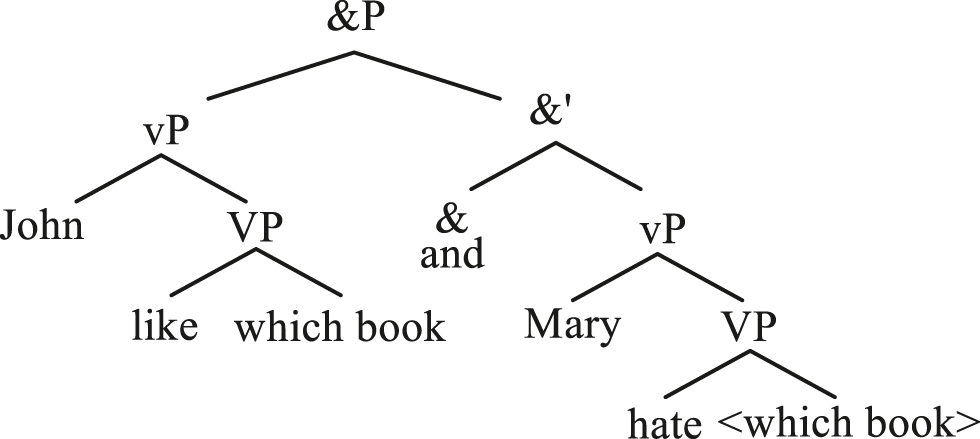

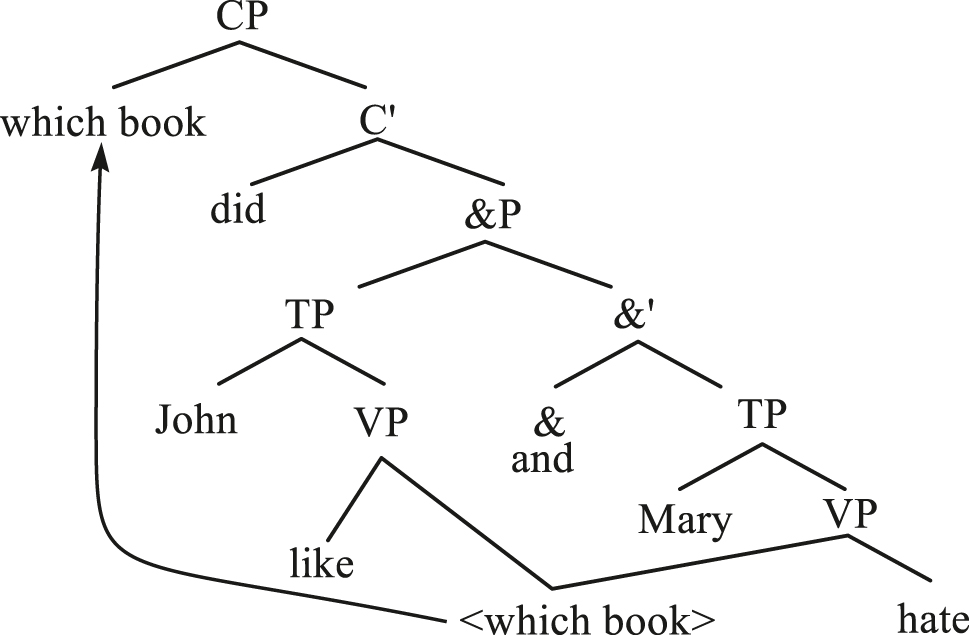

Second, Citko (2003, 2005] attempts to explain ATB dependency through a multidominance structure (Goodall 1987; Moltmann 1992; Riemsdijk 2006, etc.). Specifically, she proposes a parallel merge account which creates symmetric and multidominant structures, as long as the effects of multidominance are invisible at Spell-Out (cf. Chomsky 2000). For the purpose of linearization, the multidominated element must move overtly to a higher position outside the coordination site, obeying Kayne’s (1994) Linear Correspondence Axiom, which dictates that the precedence in linearization be directly mapped from the c-command relation: XP precedes YP if and only if XP asymmetrically c-commands YP. Accordingly, if a multidominated element stays in situ, it cannot be linearized. This is demonstrated in (19).

| Which book did John like and Mary hate? |

|

As Citko’s (2005]: 493) multidominance analysis only posits one copy inside the conjuncts, which should apparently result in symmetric reconstruction, it cannot account for the asymmetric reconstruction effect in (13), (14), and (15).

Third, Munn’s (1993], 2001]) parasitic gap analysis may explain the asymmetric reconstruction effect in ATB wh-questions. According to Munn, under coordination, the second conjunct is adjoined to the first, forming a Boolean structure. It is further assumed that the two coordinated conjuncts may have separate gaps as in (20).

| Which book did [TP [TP John like __ ] [BP Op and [TP Mary hate __ ]]]? |

Under this analysis, there is an overt operator (i.e., which book) movement, leaving a gap, within the first conjunct, and there is a covert operator (i.e., Op) movement, leaving a distinct gap, in the second conjunct. More precisely, the wh-filler in ATB questions satisfies the case and θ-requirements of the first-conjunct predicate like, while the null operator satisfies those of the second-conjunct predicate hate. As a result, only the first conjunct is affected by the reconstruction of the wh-filler because the wh-filler originated within the first conjunct and never existed in the second conjunct.

To summarize, previous analyses of English ATB wh-dependencies make distinct predictions regarding the first-conjunct sensitivity of asymmetric reconstruction. In this context, we will explore asymmetric case-mismatching in Korean left-node-raising, which may be connected to case-mismatching observed in Korean ATB wh-questions.

2.3 Locus of a pivot in left-node-raising

In English right-node-raising (RNR) constructions, a right-peripheral string may be shared by the two conjuncts, as illustrated in (21).

| John wrote, and Mary read a book. |

The shared element (i.e., pivot) a book in (21) appears only in the second conjunct, but can be interpreted in both conjuncts.

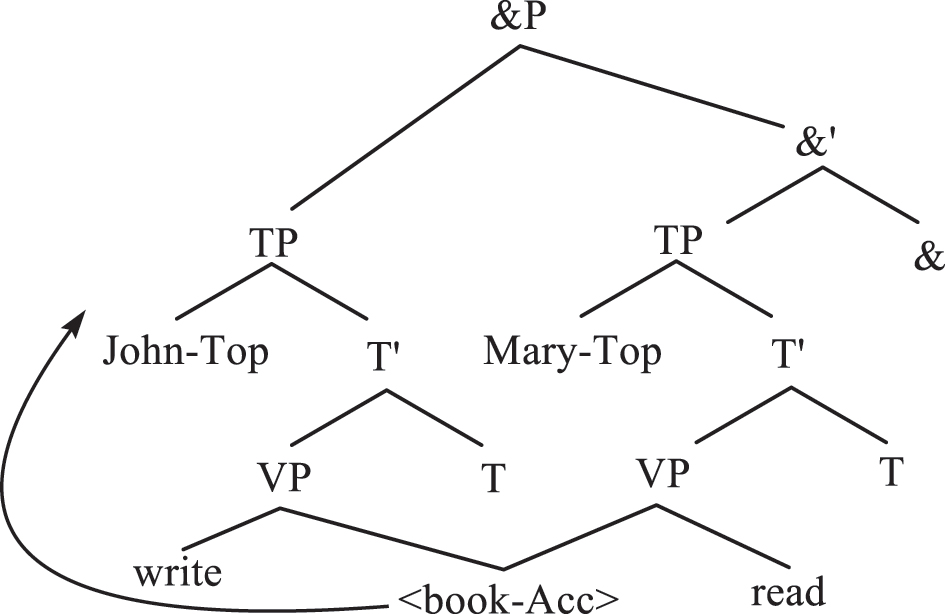

Chung (2010) reports that Korean has a mirror image of RNR, which is called left-node-raising (LNR) (Nakao 2010; Yatabe 2001 for Japanese LNR), as in (22).

| Chayk-ul | John-un | ssu-ko, | Mary-nun | ilkessta. |

| book-Acc | John-Top | write-and | Mary-Top | read |

| ‘The book, John wrote and Mary read.’ | ||||

The left-peripheral pivot chayk-ul ‘book-Acc’ in (22) can be interpreted as the missing element in both conjuncts. In order to explain the nature of LNR, Yatabe (2001) and others (Chung 2010; Kim et al. 2023; Nakao 2010, etc.) have proposed various analyses.

According to the symmetric approach, the pivot, which originated in both conjuncts, was subcategorized by both conjunct predicates. In this regard, Chung (2010) explores a multidominance account of LNR, adopting Citko’s (2003, 2005] theory of multidominance as follows:

|

The multidominated pivot in (23) was base-generated as an argument of each predicate. This naturally captures the case-matching requirement. As mentioned earlier, the pivot under Citko’s multidominance theory must move to a higher position in order to be linearized.

What is notable is that LNR is more acceptable when the case of the pivot is licensed in the first conjunct than in the second conjunct. Kim et al.’s (2020, 2023] experimental findings show that the case-matching requirement may be obviated as long as the case of the LNRed pivot is licensed in the first conjunct, as shown below:

| Mary-eykey | oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | brother-Nom | flowers-Acc | giveDat-and |

| emma-ka | ttattushakey | macihayssta. | |

| mom-Nom | warmly | welcomedAcc | |

| ‘Mary, her brother gave flowers, and her mom welcomed warmly.’ | |||

| *Mary-eykey | emma-ka | ttattushakey | maciha-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | mom-Nom | warmly | welcomeAcc-and |

| oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwuessta. | |

| brother-Nom | flowers-Acc | gaveDat | |

| ‘Mary, her mom welcomed warmly, and her brother gave flowers.’ | |||

In (24a), the dative case of the pivot is licensed by the first-conjunct predicate cwu(ta) ‘to give,’ but not by the second-conjunct predicate maciha(ta) ‘to welcome.’ Conversely, in (24b), the dative case of the pivot is not licensed by the first-conjunct predicate maciha(ta) but is licensed by the second-conjunct predicate cwu(ta). According to the multidominance approach, the pivot in LNR is simultaneously dominated by both conjuncts and then moved out of the shared position. As a result, case-mismatching of the pivot is predicted to be ill-formed regardless of where it occurs. However, the experimental results from Kim et al. (2020, 2023] show that case-matching in the first conjunct, as in (24a), is significantly more acceptable than case-matching in the second conjunct, as in (24b).

This first-conjunct-sensitivity of case-licensing in LNR could pose a dilemma for the multidominance approach (Chung 2010; Nakao 2010). Following Kim et al. (2020, 2023], we maintain that Korean LNR constructions are a type of null object constructions, where the pivot is asymmetrically scrambled only from the first conjunct and there is a null pronoun pro in the second conjunct, which is anaphoric to the LNRed pivot. The following shows the derivation of (24a).

| scrambling-plus-pro analysis of LNR | ||||||

| Mary1-Dat | [brother-Nom | t1 | flowers-Acc | giveDat] | ||

| [mom-Nom | warmly | pro | welcomedAcc] | |||

The pivot in (25) was base-generated only in the first conjunct and assigned case exclusively from the first-conjunct predicate. The missing argument in the second conjunct is pro.[4]

To summarize, the scrambling-plus-pro account would be better than the multidominance account with respect to the case-mismatching property in Korean LNR. We will show later on that the first-conjunct case-licensing preference of the pivot in LNR can be carried over to ATB wh-dependency in Korean.

2.4 D-linking

As previously mentioned, there has been an issue regarding the difference between bare wh-phrases and D-linked wh-phrases in relation to wh-dependency, which relates to the gaps that are necessarily linked to wh-phrase fillers. D-linked wh-phrases have generally been considered as being connected to previous discourse in some way, but for our purposes here, we will use it primarily as a term for which-phrases that indicate a group of individuals. In the syntax literature, it has been noticed that extracting the unmarked wh-phrase what from the wh-island results in a sentence that is considered unacceptable as in (26a). However, the extraction of the D-linked wh-phrase which problem in (26b) is seen as acceptable. This suggests that the wh-island violation in (26b) is somehow repaired, although it is still less acceptable than the wh-extraction in (26c).

| *What do you wonder [who solved __ ]? |

| ?Which problem do you wonder [who solved __ ]? |

| What do you think [that John solved __ ]? |

The phenomenon of D-linking thus poses an intriguing problem, and several explanations have been put forward to account for it.

One popular approach suggests that island violations like (26a) are unacceptable due to a syntactic issue. According to Rizzi (1990, 2004], the dependency between the filler what and its gap site in (26a) violates a fundamental property of syntax called relativized minimality, which does not allow for the dependency between a filler and a gap when there is another intervening filler, such as who in the case of (26a), that could also potentially form a similar dependency with the gap. However, D-linked wh-phrases share similarities with fronted topics, which are not affected by relativized minimality effects. This is because D-linked wh-phrases also contain additional lexical material beyond the wh-word itself and rely on previously mentioned elements in the discourse. Therefore, if D-linked wh-phrases are interpreted as topics, they should be able to bypass the relativized minimality requirement, which would increase their acceptability.

The second popular approach proposes that the reason for unacceptability of island violations like (26a) is due to limitations in working memory (Goodall 2015; Hofmeister and Sag 2010; Kluender 1998; Kluender and Kutas 1993, etc.). The filler what must be held in working memory until it can be reintegrated into the structure at the gap site in the embedded clause. This is difficult because maintaining the filler what in working memory, while processing a clause boundary and the intervening filler who, overwhelms the limited capacity of the processor. Thus, reintegration of the filler what is less likely to succeed and the sentence is perceived as unacceptable. However, when the filler is D-linked as in (26b), it requires more initial processing due to the presence of lexical material, which gives the filler which problem a higher level of initial activation in working memory. This enables the filler which problem in (26b) to survive more successfully until it can be reintegrated at the gap site. There is substantial evidence that such a processing advantage for D-linked fillers exists, likely leading to higher acceptability (Diaconescu and Goodluck 2004; Frazier and Clifton 2002; Goodall 2015; Hofmeister and Sag 2010; Hofmeister et al. 2013; Kluender 1998, etc.).

The working memory approach to D-linking and islands differs from the syntactic approach in a crucial way. Both approaches assign unique properties to D-linked fillers, but only the working memory approach would expect these properties to enhance acceptability even when there is no island violation present. Specifically, D-linked fillers are thought to facilitate individuation, allowing them to avoid island constraints, but the syntactic approach does not anticipate the effect on acceptability outside of island environments. In contrast, the working memory approach proposes that D-linked fillers have a heightened level of activation, promoting better retention in working memory and reintegration at the gap position, regardless of the structure. It thus predicts that making a filler D-linked should enhance acceptability in both well-formed and ill-formed contexts. Therefore, the working memory approach and the syntactic approach have a fundamental divergence in that the former predicts that D-linking will increase acceptability in both well-formed and ill-formed contexts, whereas the latter does not.[5]

As far as we know, no one has investigated whether D-linking affects the acceptability of case-mismatch violations in ATB wh-dependency, regardless of where the case-mismatching gaps occur. Our study aims to address this question.

3 Experiment

We have a hypothesis that in Korean ATB wh-questions, the acceptability of case-mismatching of wh-fillers is dependent on the locus of a conjunct and D-linking status of a wh-filler. To explore this, we will adopt Munn’s (1993, 2001] parasitic gap analysis of ATB wh-questions. The first factor, LOCUS, refers to the relative acceptability of case-licensing whether case-licensing of wh-fillers occurs in the first conjunct or in the second conjunct. We predict that the first-conjunct case-licensing (i.e., the second-conjunct case-mismatch) will be more acceptable than the second-conjunct case-licensing (i.e., the first-conjunct case-mismatch) in that the wh-filler has an exclusive dependency on the first conjunct. The second factor, FILLER, refers to the acceptability of D-linked versus bare wh-fillers in ATB wh-questions. We predict that the D-linked wh-filler will be more acceptable than the bare wh-filler due to the amelioration effect of the former.

3.1 Participants, materials, and design

We recruited 43 self-reported native Korean speakers, who were undergraduate students at a university in South Korea, with a mean age of 21.93 years (SD: 2.04). They agreed to participate in the study and provided informed consent in exchange for course credit. The online experiment was generally completed within 10 min. We excluded responses from three participants who were found to be inattentive during the task, using a specific procedure described in Section 3.2. Therefore, only the responses from 40 participants (10 from each of the four lists) were used in the analysis.

Experimental items were wh-questions and were prepared using a 2 × 2 design, crossing LOCUS and FILLER. The four conditions are exemplified in (27).

| [1st | D-linked] | ||||||

| Enu | nala-uy | kyohwan-haksayng-eykey | John-i | |||

| which | country-Gen | exchange-student-Dat | John-Nom | |||

| kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, | Mary-ka | ttattushakey | |||

| flowers-Acc | give-and | Mary-Nom | heartily | |||

| macihayss-ni? | ||||||

| welcomed-Q | ||||||

| ‘To which country’s exchange student did John give flowers, and Mary heartily welcome?’ | ||||||

| [2nd | D-linked] | ||||

| Enu | nala-uy | kyohwan-haksayng-eykey | Mary-ka | |

| which | country-Gen | exchange-student-Dat | Mary-Nom | |

| ttattushakey | machiha-ko, | John-i | kkochtapal-ul | |

| heartily | welcome-and | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | |

| cwuess-ni? | ||||

| gave-Q | ||||

| ‘To which country’s exchange student did Mary heartily welcome and John give flowers?’ | ||||

| [1st | Bare] | |||

| Nwukwu-eykey | John-i | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| who-Dat | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | give-and |

| Mary-ka | ttattushakey | macihayss-ni? | |

| Mary-Nom | heartily | welcomed-Q | |

| ‘To whom did John give flowers, and Mary heartily welcome?’ | |||

| [2nd | Bare] | |||

| Nwukwu-eykey | Mary-ka | ttattushakey | machiha-ko, |

| who-Dat | Mary-Nom | heartily | welcome-and |

| John-i | kkochtapal-ul | cwuess-ni? | |

| John-Nom | flowers-Acc | gave-Q | |

| ‘To whom did Mary heartily welcome and John give flowers?’ | |||

In the [1st | D-linked] condition, the dative case of the D-linked wh-filler is licensed in the first conjunct, while in the [2nd | D-linked] condition, it is licensed in the second conjunct. Similarly, in the [1st | Bare] condition, the dative case of the bare wh-filler is licensed in the first conjunct, while in the [2nd | Bare] condition, it is licensed in the second conjunct. The full list of experimental items is available online.[6]

Sixteen sets of experimental conditions were created, with each set containing four conditions that were matched for lexical content. These sets were then assigned to four lists using a Latin square design to ensure that each list had one item from each set. Each list contained 16 experimental items and 48 filler items, with a ratio of 1:3 for experimental items to fillers. The filler items were of comparable length to the experimental items but varied in acceptability. Overall, each list contained 64 sentences.

3.2 Procedure

The experiment was conducted using a web-based platform called PCIbex (Zehr and Schwarz 2018). Participants viewed sentences one at a time on a computer screen and made acceptability judgments on a 1–7 Likert scale. The experiment consisted of 16 sets of test items and 16 “gold standard” filler items, including eight good and eight bad filler items which had previously been assessed on about 200 participants to determine their expected value (1 for bad, 7 for good). For each gold standard item, the difference between each participant’s response and its expected value was calculated, squared, and summed to obtain a sum-of-the-squared-differences value. Participants with values greater than two standard deviations from the mean were excluded from the analysis as they were deemed not paying attention during the task (cf. Sprouse et al. 2022).

3.3 Data analysis

Before analyzing the data, the raw judgment ratings, including both experimental and filler items, were converted to z-scores to eliminate potential scale biases between participants (Schütze and Sprouse 2013). This was done to standardize all participants’ ratings to the same scale and correct for the possibility that individual participants treat the scale differently. The data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects (regression) models in the R software environment (R Core Team 2020), estimated with the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015). Linear mixed-effects models allow for the simultaneous inclusion of random participant and random item variables (Baayen et al. 2008). The maximally convergent random effect structure with participant and item was used (Barr et al. 2013), and p-value estimates for the fixed and random effects were calculated by Satterthwaite’s approximation (Kuznetsova et al. 2017).

3.4 Results

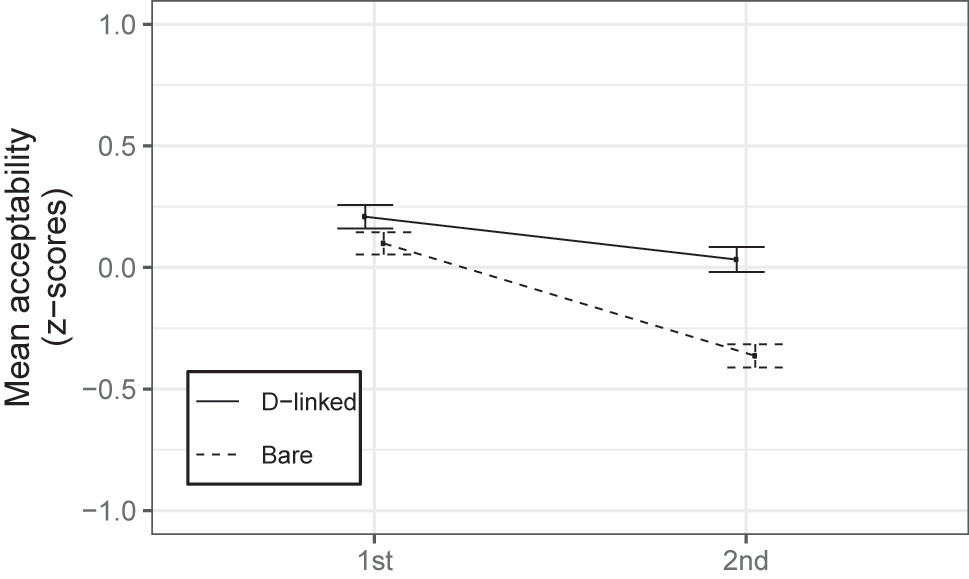

The data from 40 participants, which equates to a total of 640 tokens for the four conditions, were analyzed. Figure 1 displays the average z-scores for the acceptability ratings for each of the four experimental conditions. A score of zero reflects the overall mean acceptability rating. A positive z-score indicates that the conditions are more acceptable, while a negative z-score indicates that the conditions are less acceptable. The LOCUS effect is shown by the downward slope of the lines, while the FILLER effect is shown by a vertical gap between the lines. The interaction can be seen in the non-parallel lines that emerge when the four conditions are plotted together.

Mean acceptability scores for the experiment (error bars = SE).

Table 1 provides an overview of the linear mixed-effects model used in the analysis. The model includes LOCUS and FILLER as fixed effects, as well as their interaction. Random intercepts for both participants and items were included, along with the maximum number of random slopes justified by the data.

Fixed effects summary of the experiment.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.209 | 0.091 | 2.296 | * |

| LOCUS | −0.176 | 0.088 | −2.011 | * |

| FILLER | −0.110 | 0.084 | −1.313 | 0.194 |

| LOCUS:FILLER | −0.286 | 0.097 | −2.945 | ** |

-

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The analysis revealed a significant effect of LOCUS, indicating that the [1st] condition was rated as more acceptable than the [2nd] condition. There was no significant effect of FILLER, but there was a significant interaction between LOCUS and FILLER. The results of the interaction showed that the D-linking effect was significant in the [2nd | D-linked] condition where the first conjunct case-licensing requirement was violated, while it was not in the [1st | D-linked] condition where the first conjunct case-licensing requirement was satisfied. Planned pairwise comparisons indicated that the two 1st conditions did not significantly differ from each other (mean: 0.209 vs. 0.099; β = 0.110, SE = 0.084, t = 1.313, p = 1.000), while the [2nd | D-linked] condition was rated as significantly more acceptable than the [2nd | Bare] condition (mean: 0.032 vs. −0.364; β = 0.396, SE = 0.084, t = 4.744, p < 0.001).[7]

To summarize, there were two main findings. First, the case-licensing of bare wh-fillers in the first conjunct is far more acceptable than that in the second conjunct, supporting the claim that the first-conjunct case-licensing of bare wh-fillers is crucial in Korean ATB wh-questions. Second, the [2nd] conditions, which violate the first-conjunct case-licensing requirement in ATB dependency, are not always unacceptable; they showed super-additive degradation when the bare wh-filler, but not the D-linked wh-filler, was the pivot.

4 Discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate how case-mismatching and D-linking of wh-fillers affect the acceptability of ATB wh-questions. There were two main findings: (i) the [1st] condition was more acceptable than the [2nd] condition when wh-fillers were bare, and (ii) D-linking of wh-fillers led to a significant increase in acceptability of the [2nd] condition.

These findings contradict the prediction of the working memory approach to D-linking effects. The working memory approach proposes that the increased acceptability of D-linked fillers is due to easier retention in working memory and reintegration at the gap site, which should lead to higher acceptability regardless of the location of case-mismatched gaps. However, the findings of this study indicate that this prediction is incorrect, providing support for the syntactic approach. According to the syntactic approach, the D-linking effect is not related to working memory, and the case-mismatch effect is caused by a separate mechanism.

In this light, the case-mismatch property observed in Korean ATB wh-questions can be explained by means of the parasitic gap approach (Munn 1993, 2001]) as follows:

| [1st | D-linked] | |||||

| [CP which NPDat | [TP __ | giveDat] | [BP OpAcc | [TP __ | welcomeAcc]]] |

| [2nd | D-linked] | |||||

| [CP which NPDat | [TP __ | welcomeAcc] | [BP OpAcc | [TP __ | giveDat]]] |

| [1st | Bare] | |||||

| [CP whoDat | [TP __ | giveDat] | [BP OpAcc | [TP __ | welcomeAcc]]] |

| [2nd | Bare] | |||||

| [CP whoDat | [TP __ | welcomeAcc] | [BP OpAcc | [TP __ | giveDat]]] |

In (28a) and (28c), both of which were well-formed, the morphological case of the wh-fillers was licensed by the first-conjunct predicate before the wh-operator was moved to Spec of CP. In the second conjunct, a null operator movement took place, and the case of the trace/copy was licensed by the second-conjunct predicate.

Moving on to (28b) and (28d), these examples were ill-formed because the morphological case of the wh-fillers was not licensed in the first conjunct, which was their origin. To be specific, in (28d), the dative case of the wh-filler nwukwu-eykey ‘who-Dat’ cannot be licensed by the first-conjunct predicate machiha(ta) ‘to welcome’, which assigned accusative case. Similarly, (28b) was expected to be less acceptable than (28a) for the same reason. Surprisingly, however, the acceptability of (28b) was significantly improved via D-linking in comparison to that of (28d), even though the dative case of the which NP-filler in (28b) was not licensed by the first-conjunct accusative predicate machiha(ta).

The question that follows is why the [1st | D-linked] condition was not significantly more acceptable than the [1st | bare] condition (mean: 0.209 vs. 0.099). According to the syntactic approach, the amelioration effect of D-linking only comes into play as a last resort when the acceptability of the construction is degraded due to the violation of certain grammatical principles. This is what happened in (28b) where the case of the D-linked wh-filler was not licensed in the first conjunct. D-linking is a process that occurs during sentence processing, and it helps the parser to access and integrate D-linked fillers at the ungrammatical gap site. This ease of processing led to elevating the acceptability of (28b). In short, the finding that D-liking elevates the acceptability of only the ill-formed, but not the well-formed, Korean ATB wh-questions, supports the syntactic approach to D-linking.

As an alternative to the parasitic gap analysis, one might explore Salzmann’s (2012a, 2012b) asymmetric extraction-plus-ellipsis analysis in which two different operators exist separately in each conjunct of ATB wh-constructions: the first operator moves, and the second undergoes ellipsis. Following Aelbrecht (2009), Salzmann argues that the E-feature (Merchant 2001), which is responsible for ellipsis, is licensed through reverse Agree (cf. Chomsky 2000) by a c-commanding & in ATB dependency. The ellipsis licenser & can check off the uninterpretable feature of any E-marked constituent, as shown in (29).

| Which book did John like and Mary hate? |

| [&P &[F] [TP Mary <did>[E, |

| (based on Salzmann 2012b: 366) |

Salzmann claims that a licenser can license the ellipsis of several constituents bearing an E-feature (cf. Hiraiwa’s (2005) multiple feature checking).

Under the asymmetric extraction-plus-ellipsis analysis, however, several questions can be raised setting aside the issue of non-constituent ellipsis, which is not standard (cf. Lasnik 1999).[8] Among others, one might wonder to what extent case-mismatches in ATB constructions are tolerated. This analysis makes it difficult to explain the acceptability difference between the slightly-degraded case-mismatched ATB construction in (27c), repeated below as (30), and the fully-acceptable case-matched regular ATB construction in (31). It would permit the case mismatch in (30) since the operator in the second conjunct will have moved successive-cyclically up to Spec of vP and will thus be a possible target for deletion:

| Nwukwu-eykey | John-i | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, | |

| who-Dat | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | give-and | |

| [&P [TP | Mary-ka | ttattushakey | <nwukwu-lul>[E, |

|

| Mary-Nom | heartily | <who-Acc> | ||

| macihayss-ni] &[F]]? | ||||

| welcomed-Q | ||||

| ‘To whom did John give flowers, and Mary heartily welcome?’ | ||||

| Nwukwu-eykey | John-i | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, | |

| who-Dat | John-Nom | flowers-Acc | give-and | |

| [&P [TP | Mary-ka | <nwukwu-eykey>[E, |

wain-ul | |

| Mary-Nom | <who-Dat> | wine-Acc | ||

| senmwulhayss-ni] &[F]]? | ||||

| presented-Q | ||||

| ‘To whom did John give flowers, and Mary present a wine?’ | ||||

Considering the case-assigning property of the second conjunct verb maciha(ta) ‘to welcome’ in (30), it is reasonable to assume that the elided wh-phrase has accusative case. Since there is nothing wrong with this derivation, (30) is predicted to be well-formed and thus grammatical (i.e., fully acceptable). Recall that our experimental finding revealed that the acceptability of the case-mismatched ATB construction in (30) is somewhat degraded. Similarly, the bona fide (i.e., case-matched) ATB construction in (31) is predicted to be well-formed and grammatical. This analysis, therefore, has to resort to a rather unorthodox mechanism to explain the contrast between (30) and (31).

As previously mentioned, the parasitic gap analysis focuses on how the null operator (in the second conjunct) is identified through the presence of the overt operator (in the first conjunct). This identification happens because the overt operator licenses the null operator, requiring case agreement as pointed out by Citko (2005), Franks (1993, 1995], and Munn (1993, 2001]. Indeed, the variation in case forms between the overt wh-operator and the null operator seems to contribute to a reduced level of acceptability in ATB wh-questions when there is a lack of case agreement. This sheds light on the difference between examples (30) and (31) without requiring extra conditions. On the other hand, the asymmetric extraction-plus-ellipsis analysis lacks a similar explanation.

5 Conclusion

We have explored the characteristics of case-(mis)matching and D-linking in ATB wh-questions in Korean via an acceptability judgment experiment. The findings indicated that it is acceptable to have a case-mismatch with bare wh-fillers as long as their grammatical case is licensed in the first conjunct. Given that the asymmetric reconstruction of ATB wh-questions is possible only in the first conjunct, this outcome is anticipated. Furthermore, the experimental results demonstrated that the first-conjunct case-mismatch of bare wh-fillers (i.e., the [2nd | bare] condition) lowers acceptability ratings, whereas the first-conjunct case-mismatch of D-linked wh-fillers (i.e., the [2nd | D-linked] condition) does not result in the same amount of decrease in acceptability. Under the parasitic gap account, this outcome can be explained by the fact that the case of the wh-filler must be licensed by the first-conjunct predicate, and the case of the null operator can be licensed by the second-conjunct predicate. With this account, the issue of case-mismatch in ATB wh-questions is viewed as a matter of selection. The wh-filler that has apparently been moved ATB satisfies the case (and θ-) requirements of the first-conjunct predicate, and the null operator meets the selectional requirements of the second-conjunct predicate.

In summary, we concluded that bare wh-fillers in Korean ATB dependency can have a case-mismatch as long as their morphological case is licensed in the first conjunct. The results also showed that D-linking only increases the acceptability of sentences when the gap is not grammatically licensed, thus lending support to the syntactic approach over the working memory approach to D-linking.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics reviewers, the PSiCL editor, and the audiences at the 2023 Seminar at Korea University and the 2024 Summer Conference of the Korean Society for Language and Information for their helpful feedback and comments on the material presented here. Any remaining errors are solely our responsibility.

References

Aelbrecht, Lobke. 2009. You have the right to remain silent: The syntactic licensing of ellipsis. Brussels, Belgium: University of Brussel dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Rolf H., Douglas J. Davidson & Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory & Language 59(4). 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory & Language 68(3). 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Benjamin M. Bolker & Steven C. Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2020. On the coordinate structure constraint, across-the-board-movement, phases, and labeling. In Jeroen van Craenenbroeck, Cora Pots & Tanja Temmerman (eds.), Recent developments in phase theory, 133–182. Berlin & Boston: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501510199-006Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Roger Martin, David Michaels & Juan Uriageraka (eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, 89–155. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2010. Left node raising as a shared node raising. Studies on Generative Grammar 20(1). 549–576.10.15860/sigg.20.1.201002.51Search in Google Scholar

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1990. Types of A’-dependencies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara. 2003. ATB wh-movement and the nature of merge. In Makoto Kadowaki & Shigeto Kawahara (eds.), Proceedings of the 33th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, 87–102. Amherst, MA: Graduate Linguistics Student Association (GLSA).Search in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara. 2005. On the nature of merge: External merge, internal merge, and parallel merge. Linguistic Inquiry 36(4). 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438905774464331.Search in Google Scholar

Diaconescu, Rodica Constanta & Helen Goodluck. 2004. The pronoun attraction effect for D(iscourse)-linked phrases: Evidence from speakers of a null subject language. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 33(4). 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jopr.0000035103.19149.dc.10.1023/B:JOPR.0000035103.19149.dcSearch in Google Scholar

Dyła, Stefan. 1984. Across the board dependencies and case in Polish. Linguistic Inquiry 15(4). 701–705.Search in Google Scholar

Fernández-Salgueiro, Gerardo. 2008. Deriving the CSC and unifying ATB and PG constructions through sideward movement. In Charles B. Chang & Hannah J. Haynie (eds.), Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 156–162. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Franks, Steven. 1993. On parallelism in across-the-board dependencies. Linguistic Inquiry 24(3). 509–529.Search in Google Scholar

Franks, Steven. 1995. Parameters of Slavic morphosyntax. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195089707.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Frazier, Lyn & Charles Clifton Jr. 2002. Processing “d-linked” phrases. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 31(6). 633–660.10.1023/A:1021269122049Search in Google Scholar

Goodall, Grant. 1987. Parallel structures in syntax: Coordination, causatives and restructuring. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goodall, Grant. 2015. The D-linking effect on extraction from islands and non-islands. Frontiers in Psychology 5(Article 1493). 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01493.Search in Google Scholar

Hein, Johannes & Andrew Murphy. 2020. Case matching and syncretism in ATB-dependencies. Studia Linguistica 74(2). 254–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/stul.12126.Search in Google Scholar

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2005. Dimensions of symmetry in syntax: Agreement and clausal architecture. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Hofmeister, Philip & Ivan A. Sag. 2010. Cognitive constraints and island effects. Language 86(2). 366–415. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.0.0223.Search in Google Scholar

Hofmeister, Philip, T. Florian Jaeger, Inbal Arono, Ivan A. Sag & Neal Snider. 2013. The source ambiguity problem: Distinguishing the effects of grammar and processing on acceptability judgments. Language & Cognitive Process 28(1/2). 48–87.10.1080/01690965.2011.572401Search in Google Scholar

Johannessen, Janne B. 1998. Coordination. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-Seok, Yunhui Kim & Duk-Ho Jung. 2020. Case-mismatches in Korean left-node-raising: An experimental study. Linguistic Research 37(3). 499–529.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-Seok, Seojin Choi & Jee Young Lee. 2023. Licensing case-mismatches and dependent plural markers in Korean left-node-raising. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 59(1). 133–158. https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2022-2009.Search in Google Scholar

Kiss, Katalin É. 1993. Wh-movement and specificity. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 11(1). 85–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00993022.Search in Google Scholar

Kluender, Robert. 1998. On the distinction between strong and weak islands: A processing perspective. Syntax & Semantics 29. 241–280.10.1163/9789004373167_010Search in Google Scholar

Kluender, Robert & Marta Kutas. 1993. Subjacency as a processing phenomenon. Language & Cognitive Process 8(4). 573–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690969308407588.Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff & Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. LmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82(13). 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.Search in Google Scholar

Lasnik, Howard. 1999. Minimalist analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Lenth, Russell, Henrik Singmann, Jonathon Love, Paul Buerkner & Maxime Herve. 2018. Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means (Version 1.4.6) [R package]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed 1 March 2024).10.32614/CRAN.package.emmeansSearch in Google Scholar

Marušič, Franc Lanko & Rok Žaucer. 2017. Coordinate structure constraint: A-/A’-movement vs. clitic movement. Linguistica Brunensia 65(2). 69–85.Search in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199243730.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Moltmann, Friederike. 1992. Coordination and comparatives. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Munn, Alan. 1993. Topics in the syntax and semantics of coordinate structures. College Park, MD: University of Maryland dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Munn, Alan. 2001. Explaining parasitic gap restrictions. In Peter W. Culicover & Paul M. Postal (eds.), Parasitic gaps, 369–392. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Nakao, Chizuru. 2010. Japanese left node raising as ATB scrambling. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium, U. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 16(1). 156–165.Search in Google Scholar

Nissenbaum, Jonathan W. 2000. Investigations of covert phrase movement. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Nunes, Jairo. 2004. Linearization of chains and sideward movement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4241.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David. 1987. Wh-in-situ: Movement and unselective binding. In Eric Rueland & Alice ter Meulen (eds.), The representation of (in)definiteness, 98–129. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 3.6.3) [Computer software]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.Search in Google Scholar

Riemsdijk, Henk van. 2006. Free relatives. In Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.), The Blackwell companion to syntax, 338–382. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470996591.ch27Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 2004. Locality and left periphery. In Adriana Belletti (ed.), Structures and beyond [The cartography of syntactic structures 3], 223–251. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195171976.003.0008Search in Google Scholar

Ross, John R. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Salzmann, Martin. 2012a. A derivational ellipsis approach to ATB-movement. The Linguistic Review 29(3). 397–438. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2012-0015.Search in Google Scholar

Salzmann, Martin. 2012b. Deriving reconstruction asymmetries in across the board movement by means of asymmetric extraction + ellipsis. In Peter Ackema, Rhona Alcorn, Caroline Heycock, Dany Jaspers, Jeroen van Craenenbroeck & Guido Vanden Wyngaerd (eds.), Comparative Germanic syntax: The state of the art, 353–385. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Schütze, Carson T. & Jon Sprouse. 2013. Judgment data. In Robert J. Podesva & Devyani Sharma (eds.), Research methods in linguistics, 27–50. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139013734.004Search in Google Scholar

Sprouse, Jon, Troy Messick & Jonathan David Bobaljik. 2022. Gender asymmetries in ellipsis: An experimental comparison of markedness and frequency accounts in English. Journal of Linguistics 58(2). 345–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226721000323.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Edwin. 1978. Across-the-board rule application. Linguistic Inquiry 9(1). 31–43.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Edwin. 1990. The ATB theory of parasitic gaps. The Linguistic Review 6(3). 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.1987.6.3.265.Search in Google Scholar

Yatabe, Shuichi. 2001. The syntax and semantics of left-node raising in Japanese. In Dan Flickinger & Andreas Kathol (eds.), Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, 325–344. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.10.21248/hpsg.2000.19Search in Google Scholar

Zehr, Jérémy & Florian Schwarz. 2018. PennController for internet based experiments (IBEX). https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MD832 (accessed 1 March 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Zoerner, Edward Cyril. 1995. Coordination: The syntax of &P. Irvine, CA: University of California dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Modelling the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: a mixed effects logistic regression approach

- Case-mismatching versus D-linking of ATB wh-questions in Korean

- Impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

- Developing awareness of Global Englishes: questioning the native-speakerist paradigm of ELT at a Polish university

- Continua and orientations of packing-repacking and unpacking ideational metaphor for knowledge construction

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Modelling the choice between PP+DE+N and PP+N possessive constructions in Mandarin Chinese: a mixed effects logistic regression approach

- Case-mismatching versus D-linking of ATB wh-questions in Korean

- Impacts of working memory, L2 proficiency, and cognitive flexibility on cross-domain structural priming

- Developing awareness of Global Englishes: questioning the native-speakerist paradigm of ELT at a Polish university

- Continua and orientations of packing-repacking and unpacking ideational metaphor for knowledge construction