Abstract

One major achievement in syntax has been a deep understanding of displacement in terms of Internal Merge. Therefore, displacement types initially resisting that analysis deserve scrutiny. This article investigates one. Latin verse permits tmesis – the division of “words” into nonadjacent pieces. In one subtype, radical tmesis, the cut is not obviously at a morpheme boundary. If it were not, radical tmesis would be theoretically recalcitrant. The article argues, however, that radical tmesis is actually derived by Internal Merge. The cut does occur at a morpheme boundary, despite appearances. Furthermore, the constituent orders radical tmesis produces can be derived syntactically, positing only independently motivated operations. Radical tmesis, then, is syntactic – supporting nonlexicalist frameworks, e.g., Morphology as Syntax. Even displacement types yielding apparently “irregular” outputs, then, can turn out on examination to be products of Internal Merge, a subcase of the elementary structure-building operation Merge – a theoretically welcome result, given minimalist aims.

1 Introduction

One of the most significant achievements of syntactic inquiry has been to greatly push forward our empirical and theoretical understanding of displacement – the phenomenon wherein an element occurs overtly in one position in a syntactic object SO but has a (typically covert) presence in one or more other positions within SO as well. Some of the strongest evidence for displacement comes from lexical selection, or L-selection (Merchant 2019; Pesetsky 1991: Ch. 1). This is illustrated in (1)–(2).

Examples (1a–c) show that the verb rely obligatorily L-selects a PP headed by on.[1] Crucially, the instance of on whose presence is forced by rely must be highly local to rely: it cannot appear too high, as in (1d), or too low, as in (1e) (see also Landau 2007: 488–489).

| a. | We’re discussing the fact that Katie’s experiments rely [PP on innovative techniques from France]. |

| b. | *We’re discussing the fact that Katie’s experiments rely. |

| c. | *We’re discussing the fact that Katie’s experiments rely [DP innovative techniques from France]. |

| d. | *We’re discussing on the fact that Katie’s experiments rely ([DP innova-tive techniques from France]). |

| e. | *We’re discussing the fact that Katie’s experiments rely [DP innovative techniques [PP on France]]. |

The overall picture that has emerged is one in which, for two lexical items X and Y such that X L-selects Y, (a projection of) Y must merge with (a projection of) X – i.e., L-selection is extremely local (Landau 2007: 488–489; for formal definitions of Merge aimed at accounting for this, see Collins and Stabler 2016: 63–64; Merchant 2019: 326; and Zyman 2024, esp. Sect. 4). In (2), therefore – where the on-PP is superficially entirely outside the maximal projection of rely – this PP must initially merge with rely, satisfying the latter’s L-selectional requirement, and then move to the position where it surfaces overtly. Otherwise, the L-selectional requirement of rely would be unsatisfied, so (2) would be incorrectly predicted to be unacceptable, like (1b–e).

| We’re discussing the innovative techniques from France [PP on which] Katie’s experiments rely. |

The analysis of displacement in terms of movement has been highly successful, and has only been placed on firmer conceptual ground by the insight that movement can be analyzed as Internal Merge, a subcase of the fundamental structure-building operation Merge (Chomsky 2004; see also Collins 2017: 48; Collins and Groat forthcoming; Collins and Stabler 2016: 46; Epstein et al. 1998: 13, 26; Freidin 2016: 802; Groat 1997; Hunter 2015: 274; and Kitahara 1994, 1995, 1997; see Graf 2018 for relevant discussion).[2]

That being so, any instance of displacement initially resisting analysis in terms of Internal Merge[3] deserves scrutiny. Such a phenomenon, if it indeed could not be analyzed as due to Internal Merge, would apparently require us to posit a second mechanism giving rise to displacement besides Internal Merge – yielding, ceteris paribus, a duplication of the sort that the minimalist project aims to eliminate. But if the phenomenon can be analyzed as due to Internal Merge after all, then the duplication can be avoided and the apparent obstacle to a maximally simple and elegant theory of syntax overcome.

This article, then, is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces a type of displacement, tmesis in Latin, of which one subtype (here dubbed radical tmesis) initially seems to resist analysis in terms of Internal Merge, because it splits up “words” in places where there is not obviously a morpheme boundary (i.e., displaces elements that are not obviously constituents). Section 3 scrutinizes radical tmesis more closely and argues, building on Fruyt (1991), that the “cut” in radical tmesis does consistently coincide with a morpheme boundary after all. Section 4 shows that the surface constituent orders yielded by radical tmesis can be derived syntactically, appealing exclusively to independently motivated aspects of the theory. Section 5 concludes the article by summarizing the argument that, despite appearances, radical tmesis is a product of garden-variety Internal Merge – a theoretically welcome result from a minimalist standpoint.

2 The phenomenon: radical tmesis

Latin verse permits tmesis: it allows elements traditionally considered “words” to be split up, under certain circumstances, with the pieces surfacing in nonadjacent positions. Two examples of what we might call canonical tmesis (which is not the focus of this article) are given below. In (3), the verb word praeterı̄re ‘go by, go past’ is split up by the verb word crēditur ‘is believed’; in (4), the verb word interrumpere ‘break apart’ is split up by the adverbial quasi ‘as it were’.[4]

| ea | praeter | crēditur | ı̄-r-e |

| that.f.nom.sg | past | is.believed | go-prs.inf-act |

| ‘that one [= ship] is believed to be passing by’ (Lucretius, De Rerum Natura 4.388) | |||

| radiōs | inter | quasi | rump-e-r-e | lūcis |

| rays.acc | between | as.it.were | break-th-prs.inf-act | light.gen |

| ‘to, as it were, interrupt the rays of light’ (Lucretius, De Rerum Natura 5.287) | ||||

Although such examples of canonical tmesis raise interesting questions – in particular, what are the precise lexical items, features, and elementary operations that derive the surface constituent orders they display – they do not pose any obvious problems for current mainstream syntactic theory. In any nonlexicalist framework – e.g., Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993; Halle and Marantz 1994, among others), Nanosyntax (Starke 2009, among others), or Morphology as Syntax (Collins and Kayne 2023; Crippen 2023; Julien 2022; Koopman 2020b; Ntelitheos 2022; Zyman 2020, 2023b; Zyman and Kalivoda 2020; and references therein; see also Bruening 2018b, 2018c) – structures traditionally considered “words” are built in the syntax, just like traditional “phrases,” so subconstituents of “words” are predicted to be able to undergo Internal Merge and hence surface outside those “words,” a prediction borne out by examples like (3)–(4). Note that this argument that canonical tmesis is theoretically unproblematic relies crucially on the observation that, in the relevant examples, the “cut” clearly occurs at a morpheme boundary – which, in a nonlexicalist framework, means at a syntactic boundary.

There is, however, another type of tmesis permitted in Latin verse that initially appears far more problematic for current syntactic theory: a type in which the “cut” does not obviously occur at a morpheme boundary, here dubbed radical tmesis.[5] Four examples follow:

| … | tēlō | / | Trānsfı̄git | corpus, | saxō | cere- | comminuit | -brum. |

| spear.abl | pierces | body.acc | rock.abl | sk- | crushes | -ull.acc | ||

| ‘He pierced his body with a spear [and] crushed his skull with a rock.’ (Ennius, Annales 609 [Vahlen]; pre-comma context added following Chase 1874: 373, Giles 1836: 17, Jäger 1887: 14, Ménière 1858: 9, and Merula 1595: 308)6 | ||||||||

- 6

In the literature on radical tmesis (Aicher 1989: 229; Bishop 1957; Byrne 1916: 46; Conrad 1965: 227; Cordier 1940; Debouy 2012: 200; Faust 1970: 133; Fruyt 1991; Hahn 1947: 323; Lenchantin 1947: 228; Mariotti 1988: 83; Popan 2012; Poultney 1980: 4; Raehse 1868: 12; Schmidt 1840: 34; Timpanaro 2005: 232; Vollmer 1916: 133; Zetzel 1974, among others), the “word” fragments are often written without hyphens (saxo cere comminuit brum). They are written with hyphens here to make the tmeses easier to see, and to reflect the traditional intuition that the two fragments are pieces of a single “word” (though the article will develop a Morphology as Syntax–style analysis on which there is no syntactic correlate of wordhood, so cerebrum ‘skull’ is not a fundamentally different kind of syntactic object than is, e.g., hoc cerebrum ‘this skull’ [constructed example], which would traditionally be considered two “words”).

Comminuit in (5) is glossed ‘crushes’ but translated “crushed” because the (small amount of) broader context given for this example of radical tmesis by Chase (1874: 373), Giles (1836: 17), Jäger (1887: 14), Ménière (1858: 9), and Merula (1595: 308) suggests that comminuit here is a narrative present form: formally present tense, but with past time reference. (Out of context, it could also be formally a “perfect tense” form, meaning ‘crushed’ or ‘has crushed’.)

As some of the works cited above note, the authorship of (5)–(8) has been debated. Nothing will turn on this: what is important here is not precisely who wrote (5)–(8) but what grammatical operations derive these expressions.

| Massili- | portābant | iuvenēs | ad | lı̄tora | -tānās. |

| b- | were.carrying | youths.nom | to | shores.acc | -ottles.acc |

| ‘The youths were carrying bottles to the shore.’ (Ennius, Annales 610 [Vahlen]) | |||||

| Lāmen- | color | -tātrı̄cı̄ | mūtat… |

| mour- | color.nom | -ner(f).dat | changes |

| ‘The hue of a woman in mourning changes…’ (attributed to Pomponius; see Debouy 2012: 200 for discussion) | |||

| Inveniēs | praestō | subiūncta | petorrita | |||

| you.will.find | ready | having.been.joined.acc | four.wheeled.carriages.acc | |||

| mūlı̄s: | / | Vı̄llā | Lūcāni- | mox | potiēris | -acō. |

| mules.dat | villa.abl | Lucani- | soon | you.will.take.possession.of | -acus.abl | |

| ‘You’ll find a four-wheeled carriage with a team of mules ready: you will soon become the owner of the villa Lucaniacus.’ (Ausonius, Epistle 5, 35)7 | ||||||

- 7

When (5) and (8) are repeated (and explicitly derived) below, the context preceding the minimal clause featuring the radical tmesis will be omitted.

In these examples, particularly the first three, it is initially not obvious that the “cut” occurs at a morpheme boundary. But if it did not, then accounting for these examples would apparently require us to posit a novel, constituency-insensitive displacement operation (call it X), thus complicating the theory of grammar.[8] Such a move would be undesirable not only on general grounds of theoretical parsimony but also because X would be very similar to the independently motivated operation Internal Merge, since both would effect overt displacement – and yet the two could not be unified, because Merge, whether internal or external, operates only on syntactic constituents (see Hornstein 2009: 65 and Davis 2023 for related discussion). Countenancing X, then, would introduce a suspicious duplication into the theory.

3 The cut in radical tmesis consistently occurs at a morpheme boundary

Fortunately, though, the theory of grammar need not be complicated in the way just alluded to: closer scrutiny reveals that, despite appearances, the cut in radical tmesis does in fact occur at a morpheme boundary. That that is indeed so is demonstrated in this section, paving the way for Section 4 to offer an analysis of radical tmesis as a product of Internal Merge.

The view that the cut in (5) and (6) occurs at a morpheme boundary has already been argued for convincingly by Fruyt (1991) (see also Popan 2012: 68). Fruyt’s arguments will thus provide the basis for the discussion of (5)–(6) below – which, however, will expand on them in certain ways.

Consider first (5), which is repeated here:

| saxō | cere- | comminuit | -brum |

| rock.abl | sk- | crushes | -ull.acc |

| ‘He crushed his skull with a rock.’ (Ennius, Annales 609 [Vahlen]) | |||

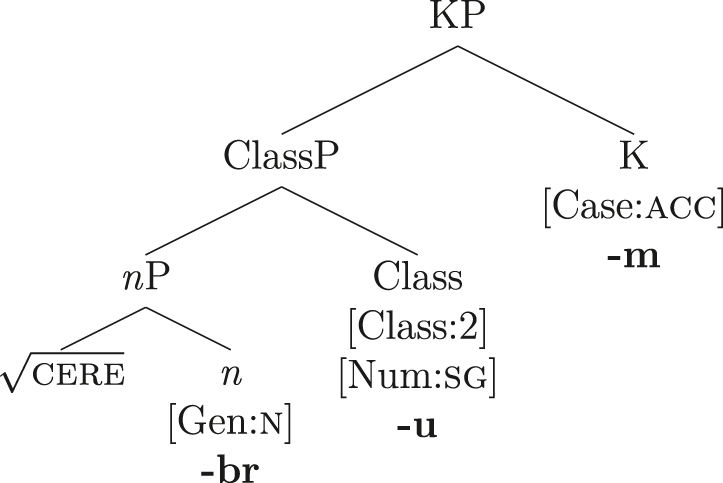

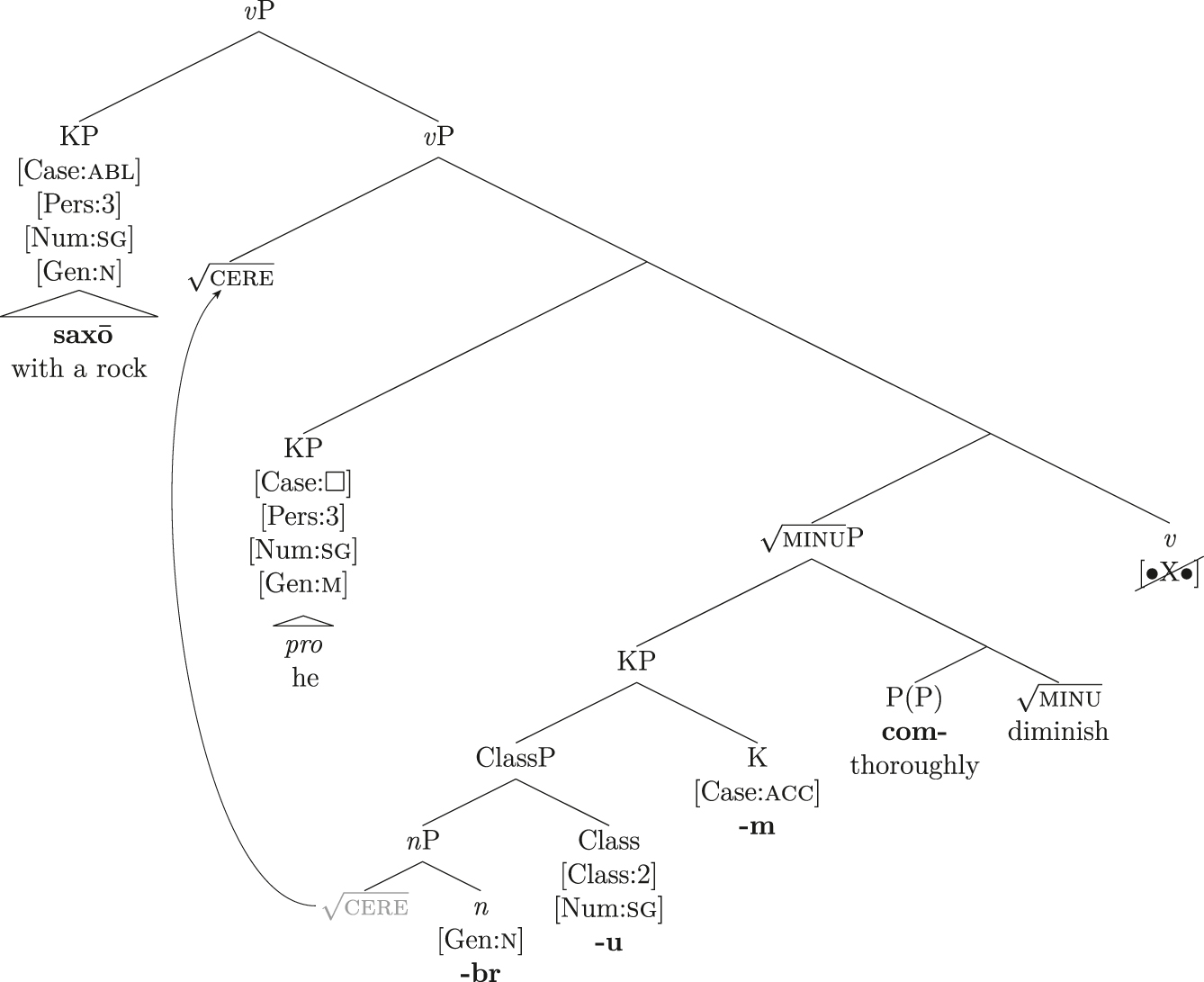

As Fruyt (1991: 244) and Popan (2012: 68) note, cerebrum ‘brain, skull’ invites a synchronic decomposition into a root cere- and a nominalizing suffix -brum – more precisely, -br, since -um is inflectional material (see below). The suffix -br typically forms instrument nouns, as in candēl-a ‘candle’ > candēlā-br-um ‘candelabrum’; crı̄-br-um ‘sieve’ (from the same root as cern-ere ‘sift’); dēlu-ere ‘wash out, wash off, cleanse’ > dēlū-br-um ‘temple, shrine, sanctuary’; lav-āre ‘wash, bathe’ > lavā-br-um ‘bathtub’; and lūc-ēre ‘shine’ > lūcu-br-um ‘candle’ (see Fruyt 1991: 244 and Serbat 1975: 90–91 for more examples).[9] Cerebrum ‘skull.acc’, then, has the structure in (10):

| Structure of cerebrum ‘skull.acc’ |

In (10),

Consider now (6), which is repeated here:

| Massili- | portābant | iuvenēs | ad | lı̄tora | -tānās. |

| b- | were.carrying | youths.nom | to | shores.acc | -ottles.acc |

| ‘The youths were carrying bottles to the shore.’ (Ennius, Annales 610 [Vahlen]) | |||||

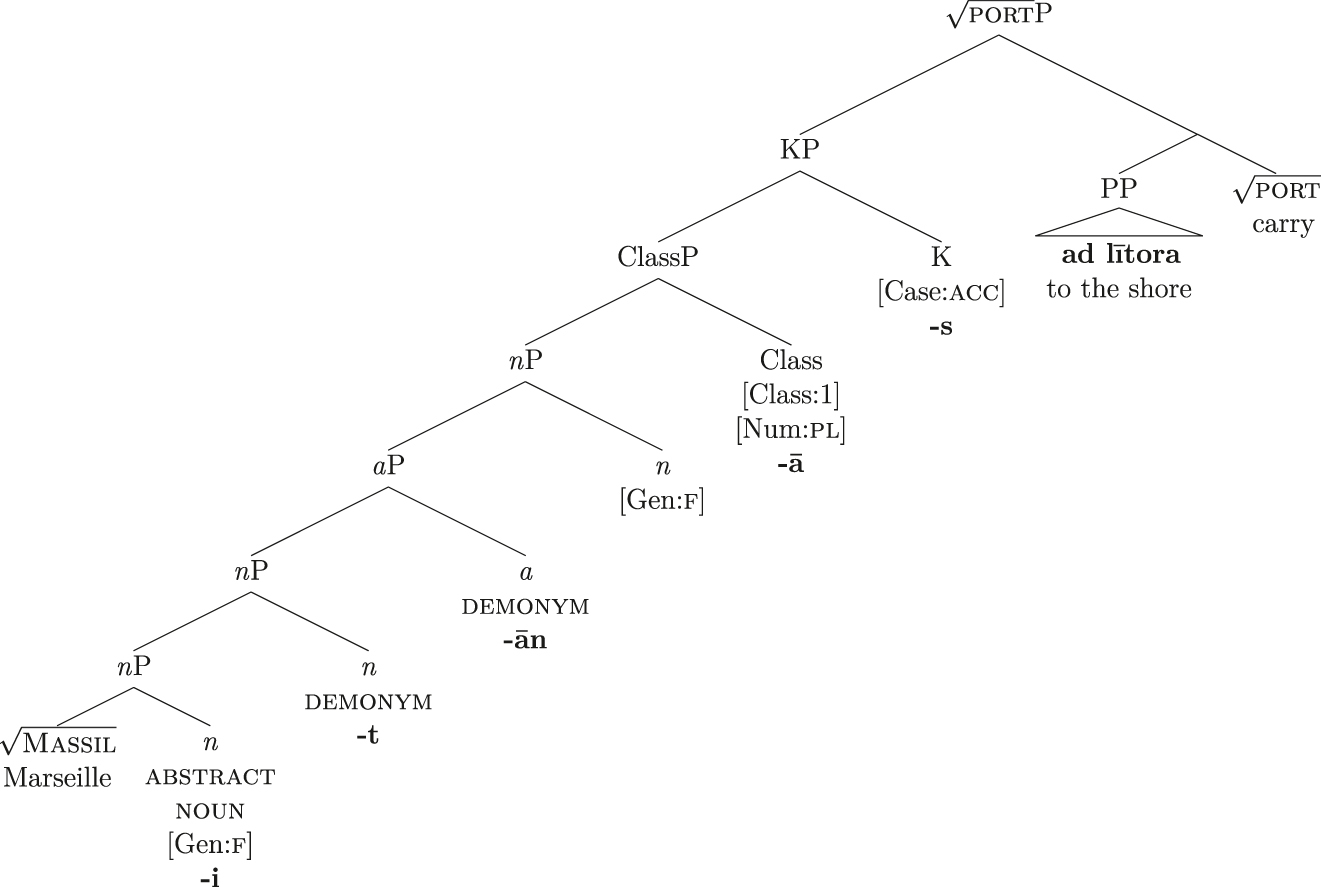

In (11), the boldfaced surface-discontinuous structure is the accusative plural form of the noun Massilitāna ‘bottle’, which is derived by conversion from the feminine form of the adjective Massilitānus ‘from Massilia (Marseille)’. If the radical tmesis in (11) is to be attributed to Internal Merge, as this article argues it should be, then there must be a morpheme boundary between Massili- and -tānās. It is not obvious at first glance that this is the case. Since -ās is inflectional material and -ān is a suffix forming demonyms (aka gentilics – as in Rōm-ān-us ‘Roman’), it initially seems natural to identify -it with the demonym-forming suffix -ı̄t (as in Antōniopol-ı̄t-ae ‘inhabitants of Antoniopolis, Lydia’), despite the vowel-length difference (on which see Fruyt 1991: 244–245 and references cited there). This would yield the decomposition in (12), with no morpheme boundary between Massili- and -tānās.

| Initial decomposition of Massilitānās ‘bottles.acc’ (to be revised) |

| Massil-it-ān-ā-s |

| Marseille-gent-gent-th.decl1-acc.pl |

| ‘bottles’ |

As Fruyt (1991: 244–245) argues, however (on the basis of somewhat different considerations from those discussed here), there is good reason to take the linearly earlier demonym-forming suffix in (11) to be not -it but -t. In particular, -t occurs in demonyms independently of -i/-ı̄:

| Hı̄lō-t-ae |

| Helos-gent-nom.pl |

| ‘the original inhabitants of the city of Helos; helots’ |

| Sax-ē-t-ān-us12 |

| Sex-v-gent-gent-m.nom.sg |

| ‘of or from Sex (a town in Hispania Baetica)’ |

- 12

Also Sex-ı̄-t-ān-us.

| Spart-i-ā-t-ēs |

| Sparta-v-v-gent-m.nom.sg |

| ‘a Spartan’ (adjectival derivative: Spart-i-ā- t -ic-us ‘Spartan’) |

| {Massil/Massal}-i-ō-t-ic-us |

| Marseille-nmlz.abstr 13 -v-gent-adj-m.nom.sg |

| ‘of or from Marseille’ |

- 13

This -i will be discussed shortly below.

That -t occurs in demonyms independently of -i/-ı̄ and can be preceded by a range of other vowels instead (see (13)–(16)) indicates that it is a morpheme unto itself. Thus, (12) should be revised:

| Final decomposition of Massilitānās ‘bottles.acc’ |

| Massil-i-t-ān-ā-s |

| Marseille-nmlz.abstr-gent-gent-th.decl1-acc.pl |

| ‘bottles’ |

In (17), the -i immediately preceding -t is analyzed as an abstract-noun-forming suffix, as in Ital-i-a ‘Italy’ (cf. Ital-us ‘Italian’). Alternatively, Massili- could in principle be an undecomposable root (shared with Massili-a ‘Marseille’), as Fruyt (1991: 245) proposes. What is important here is that there is a morpheme boundary between Massili- and -tānās after all (Fruyt 1991: 244–245; see also Popan 2012: 68). The structure corresponding to (17) is shown below:

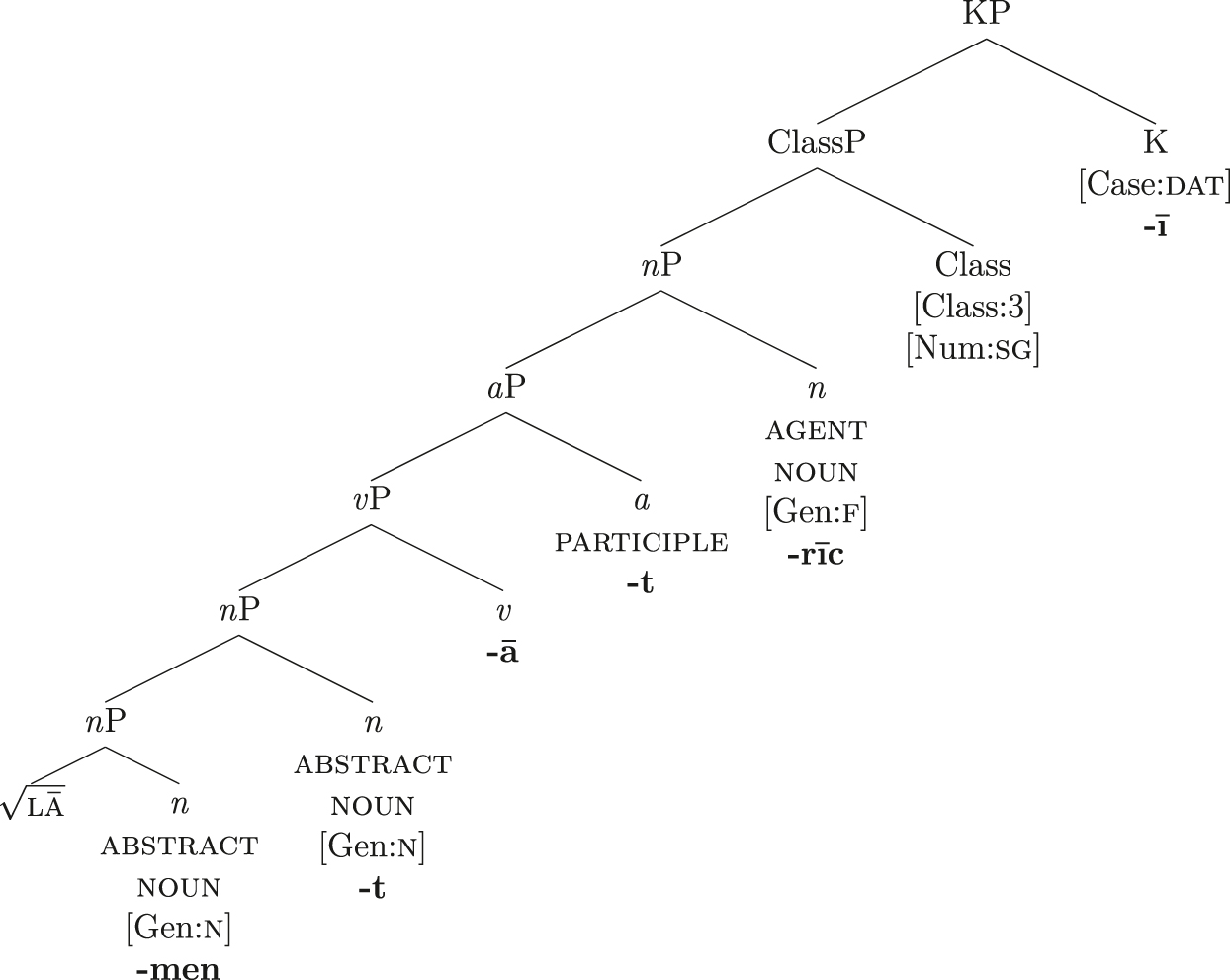

| Structure of Massilitānās ‘bottles.acc’ |

(Here, the n that takes aP as its complement is the element taken to effect the adjective-to-noun conversion – the derivation of a noun Massilitāna ‘bottle’ from the feminine form of the adjective Massilitānus, -a, -um ‘from Marseille’.)

Consider now (7), which is repeated here:

| Lāmen- | color | -tātrı̄cı̄ | mūtat… |

| mour- | color.nom | -ner(f).dat | changes |

| ‘The hue of a woman in mourning changes…’ (attributed to Pomponius; see Debouy 2012: 200) | |||

Lāmentātrı̄cı̄ ‘to/for/of a female mourner’ consists of the following morphemes, at least:

| Initial decomposition of lāmentātrı̄cı̄ ‘mourner(f).dat’ (to be revised) |

| lā-ment-ā-t-rı̄c-ı̄ |

| shout?-nmlz.abstr-th.conj1-ptcp-agt.f-dat.sg |

| ‘to/for/of a female mourner’ |

In (20), working our way from the outside in, -ı̄ is a dative singular suffix; -rı̄c is a suffix forming agent nouns (the feminine counterpart of -or); -t is an element argued at length by Zyman and Kalivoda (2020: Sect. 4.1) to be a participle-forming suffix of category a;[14] and -ā (elsewhere -a) is the theme vowel of first-conjugation verbs. The verb lāment-ā-(rı̄) ‘wail, lament’, from which (20) is derived, is itself derived from the noun lāment-(um) ‘wailing, lament’, which clearly consists of the nominalizer -ment(-um) and a root lā-, perhaps to be identified with the root of clām-āre ‘shout’ (Lewis and Short 1879; see the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae s.v. lāmentae for a different view).

If (20) were the full decomposition, there would be no morpheme boundary between lāmen- and -tātrı̄cı̄, so the radical tmesis in (19) could not be derived by Internal Merge, contra this article’s thesis. But there is good evidence that the Latin nominalizer -ment is not simplex but consists of two smaller elements: the nominalizer -men and a suffix -t. The view that this decomposition is valid diachronically has been argued for extensively (Perrot 1961; Pike 2011: 37; Uth 2010: 216, 228; and references cited there). Crucially, though, there is ample synchronic support for this decomposition as well. Thus, the nominalizer -men occurs independently of -t – as is shown vividly by minimal pairs like aerā-men-t-um ‘copper or bronze vessel or utensil’ ∼ aerā-men ‘copper, bronze’; cōgitā-men-t-um ‘a thought’ ∼ cōgitā-men ‘thinking, thought’; corōnā-men-t-um ‘garland, crown (or flowers therefor)’ ∼ corōnā-men ‘a wreathing, crowning’; and crassā-men-t-um ‘thickness; dregs, grounds’ ∼ crassā-men ‘dregs’ (see Stringer 2017: 24 for more examples). Thus, (20) should be revised:

| Final decomposition of lāmentātrı̄cı̄ ‘mourner(f).dat’ |

| lā-men-t-ā-t-rı̄c-ı̄ |

| shout?-nmlz.abstr-nmlz.abstr-th.conj1-ptcp-agt.f-dat.sg |

| ‘to/for/of a female mourner’ |

The corresponding structure follows:[15]

| Structure of lāmentātrı̄cı̄ ‘mourner(f).dat’ |

There is, then, a morpheme boundary between lāmen- and -tātrı̄cı̄ after all.

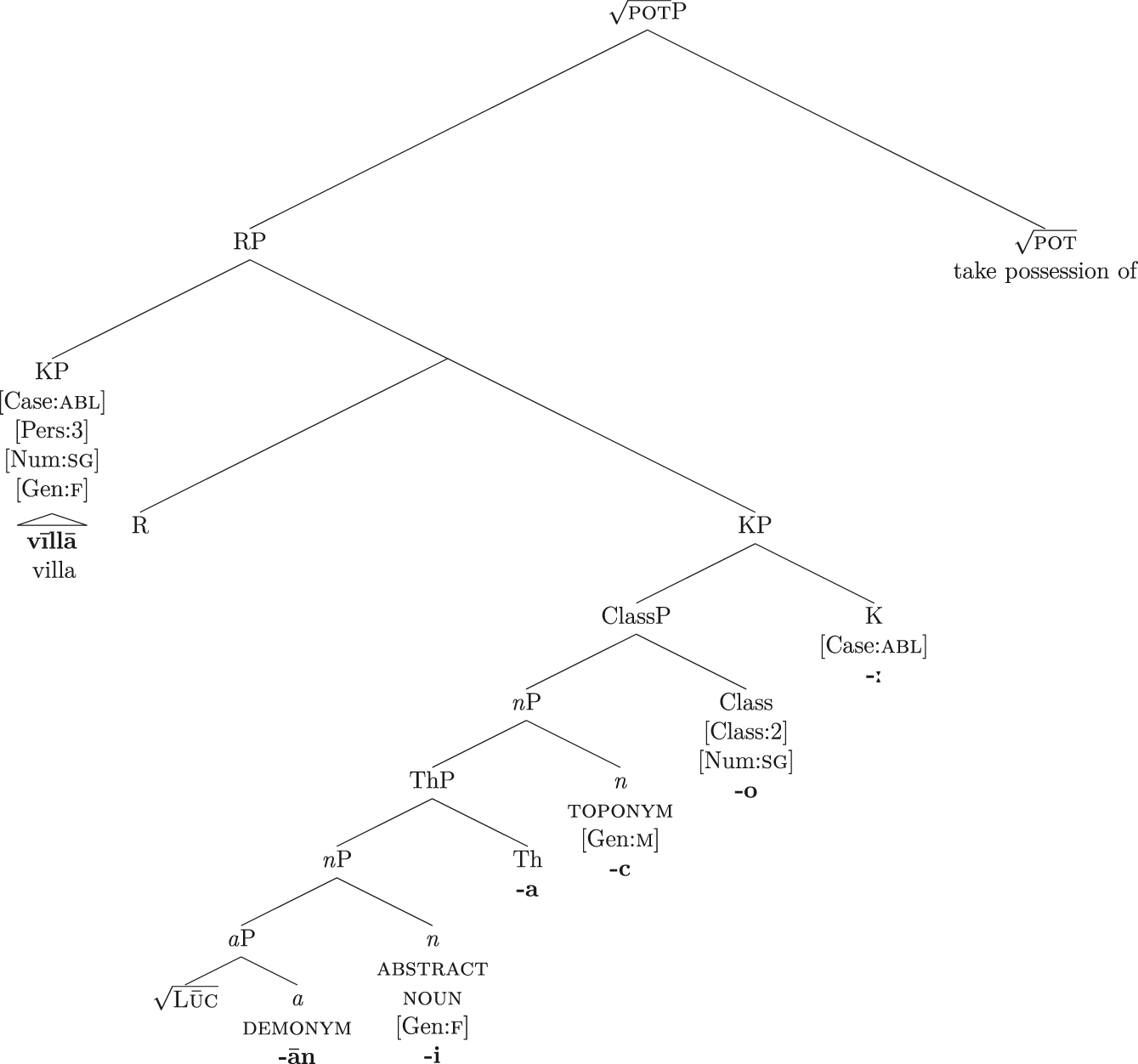

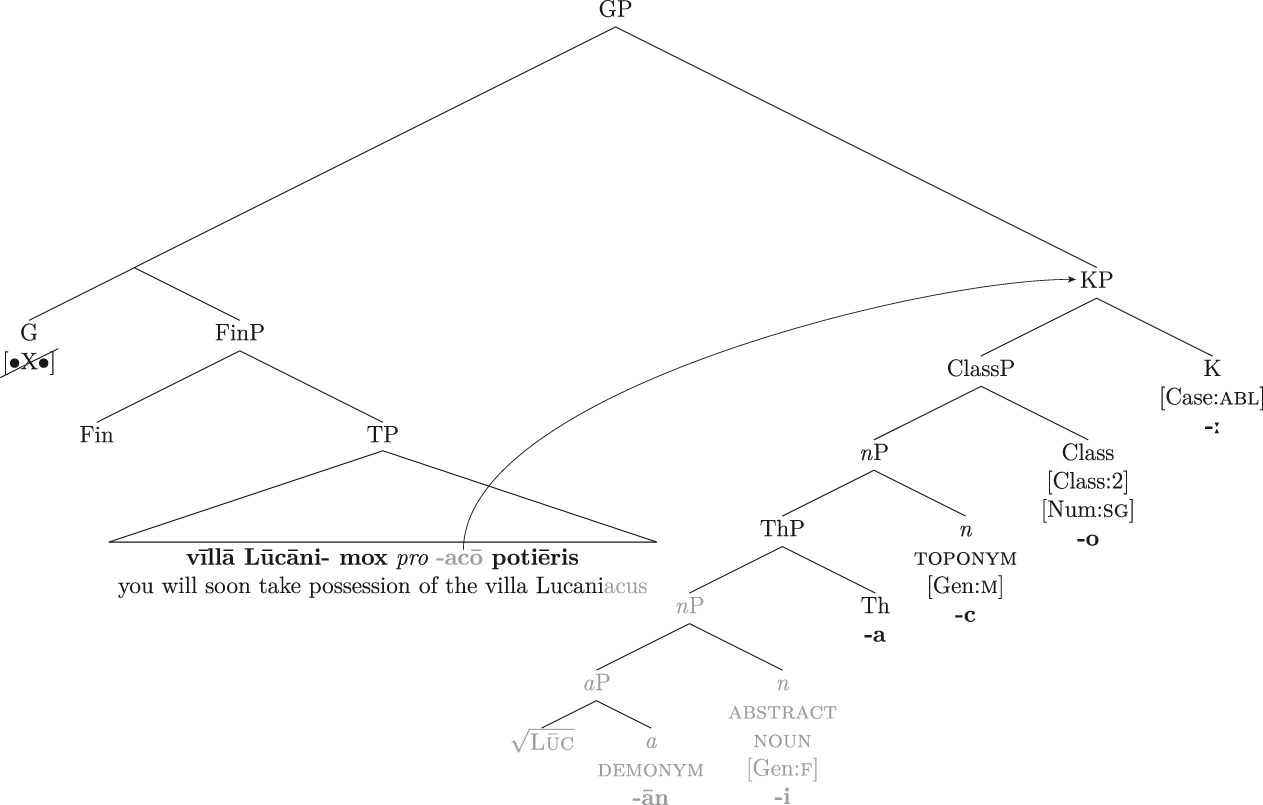

Finally, consider (8), which is repeated here:

| Vı̄llā | Lūcāni- | mox | potiēris | -acō. |

| villa.abl | Lucani- | soon | you.will.take.possession.of | -acus.abl |

| ‘You will soon become the owner of the villa Lucaniacus.’ (Ausonius, Epistle 5, 35) | ||||

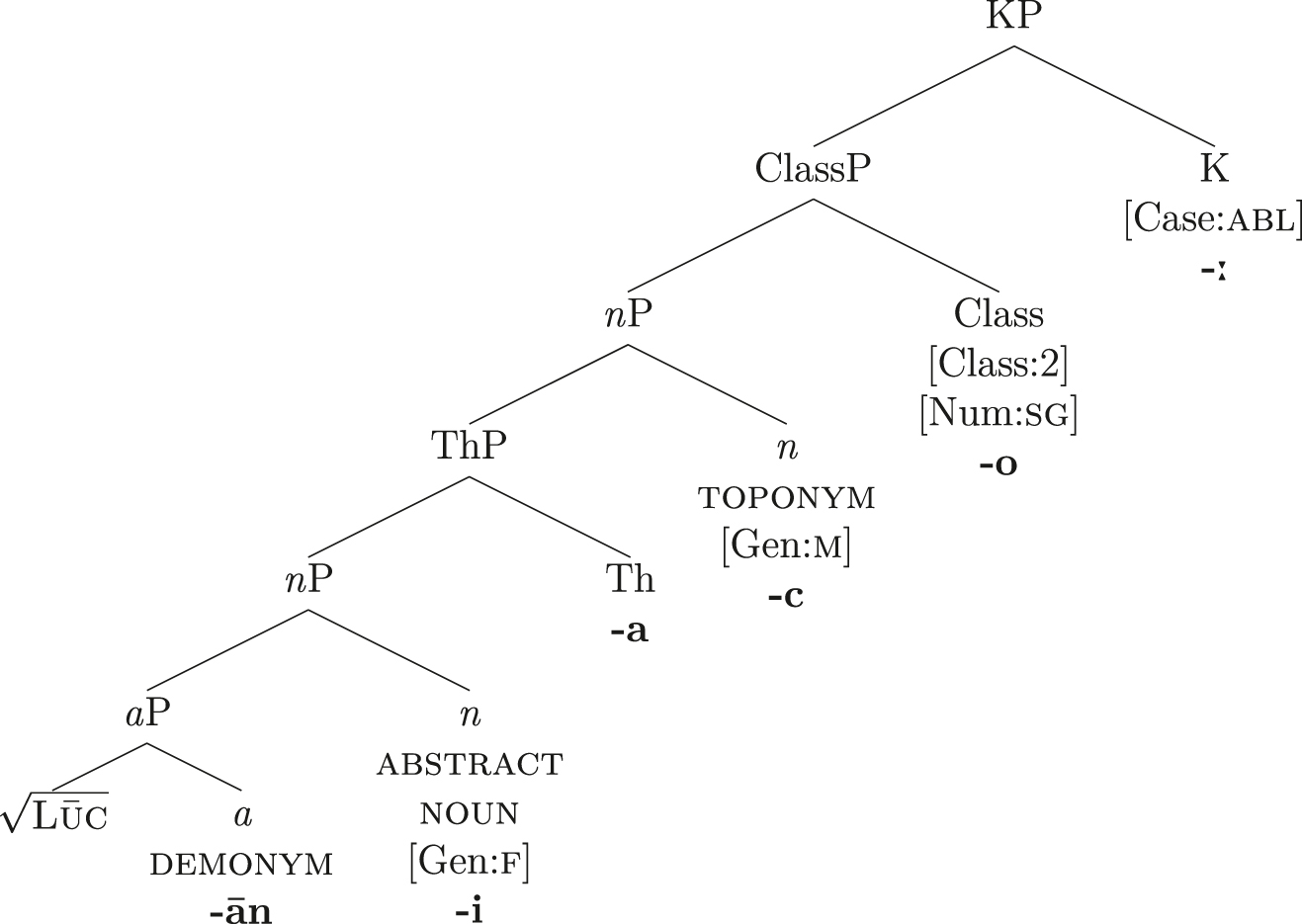

In (23), -ō is inflectional material. It is immediately preceded by -ac, a suffix that forms place names, as well as personal names. (As Mowat 1881: 381–382 discusses, the vowel in -ac can be either short or long, depending on the stem it attaches to. Here it is short, as revealed by the meter: (23) is the second line of an elegiac distich.) In fact, the discussion in Mowat (1881: 382) makes it quite plausible to take the place-name-forming suffix proper to be -c, the immediately preceding -a being a nominal theme vowel, though nothing will hinge on this.[16] The sequence -a-c is immediately preceded by -i, the abstract-noun-forming suffix discussed under (17). This -i, in turn, is preceded by Lūcān-, the stem of the name Lūcān-us: as Billy (2016: 98–99) discusses, Ausonius calls his estate Lūcāniacus because it previously belonged to his late father-in-law, Attūsius Lūcānus Talı̄sius.[17] The stem Lūcān- will be taken here for concreteness to consist of the demonym-forming suffix -ān (discussed under (11)) and a root Lūc-, though nothing will turn on that. The pre-tmesis structure of Lūcāniacō ‘Lucaniacus’ in (23), then, is:

| Structure of Lūcāniacō ‘Lucaniacus.abl’18 |

- 18

In (24), the masculine ablative singular ending -ō is decomposed into the -o (elsewhere -u) that is the second-declension theme vowel (here analyzed as exponing a [Declension] Class head that is also the locus of the singular Number feature) and a suprasegmental morpheme -ː, here analyzed as the exponent of the ablative K(ase) head.

The -a in (24), which was taken above to be a nominal theme vowel, is assigned to a category Th(eme) for concreteness. But if its categorial feature is something other than [cat Th] – e.g., [cat n] – or if -ac is a monomorphemic toponym-forming suffix of category n (see Mowat 1881: 382 for discussion), the analysis will be essentially unaffected.

Recapitulating: in radical tmesis, a structure traditionally considered a “word” is split in two, and the pieces are separated by other material – and it is initially not obvious that the cut occurs at a morpheme boundary. Closer scrutiny reveals, though, that the cut in radical tmesis does occur at a morpheme boundary, though this is much less obvious on casual inspection than it is in cases of canonical tmesis. This finding is significant because it opens the door to analyzing radical tmesis as a product of Internal Merge, entirely on a par with ordinary phrasal movement.

4 Deriving the constituent order in radical tmesis syntactically

Successfully analyzing radical tmesis as a product of Internal Merge will, however, require more than just showing that the cut occurs at a morpheme boundary – i.e., at a syntactic boundary (the conclusion just reached). That the cut occurs at a morpheme boundary indicates that radical tmesis could be derived by Internal Merge, in principle. But showing that it actually can be derived by Internal Merge (in a principled way) will require establishing that the applications of Internal Merge (and other operations) needed to derive the surface constituent orders produced by radical tmesis are independently motivated – the goal of this section.

Before we proceed, it will be worthwhile to highlight two assumptions that will be made in the analysis developed below. First, Merge – whether external or internal – is driven by structure-building features [•F•] (the notation is from Heck and Müller 2007). Secondly, there exist underspecified structure-building features [•X•] that are not keyed to a particular categorial feature (the way that [•D•] on T in English is keyed to the categorial feature [cat D]; see Lai 2019: 248), which can therefore trigger movement even of a categoryless root. The hypothesis that underspecified structure-building features exist is independently supported by the famous “nonpickiness” of movement to [Spec,CP] in V2 environments, which is likewise quite category-insensitive (see Bošković 2020a: 62 and references cited there, as well as Newman 2020: 10; see also Zyman 2018 for empirical observations that suggest that [•X•] can trigger External as well as Internal Merge). Other relevant assumptions will be made explicit as we proceed.

4.1 A brief introduction to Latin clause structure

Establishing that radical tmesis not only could in principle but in fact can be derived syntactically will require us to have a clear idea of the structure and derivation of Latin clauses. Much recent work has argued that, in Latin, the building of an ordinary clause involves movement of a (phrasal) verbal projection to a specifier position in the inflectional layer (Bailey 2010; Danckaert 2012, 2014, 2017a, 2017b; Gianollo 2016; on this kind of derivation crosslinguistically, see many of the papers in Carnie and Guilfoyle 2000; Carnie et al. 2005). This article will adopt the version of that analysis developed by Zyman and Kalivoda (2020), henceforth Z&K. On their analysis, the building of a finite clause in Latin involves two key operations: 1) Asp-to-T head movement, and 2) vP-movement to [Spec,TP]. Consider (25):

| laud-ā-v-era-t |

| praise-th-pfv-pst-3sg |

| ‘he/she/it had praised’ |

| (adapted from Z&K: 6) |

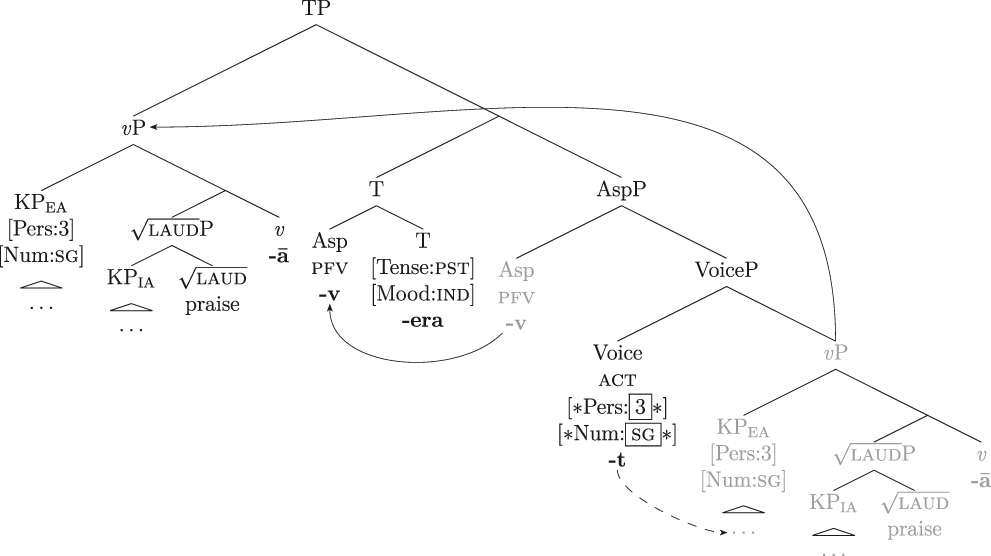

A clause built from (25) is derived as in (26). (EA = ‘external argument’; IA = ‘internal argument’.)

| Derivation of laudāverat ‘he/she/it had praised’ |

|

| (adapted from Z&K: 619) |

- 19

This tree innocuously replaces V and its projections (in Z&K’s tree) with a categoryless root and its projections, for consistency with the trees above.

On this analysis, whenever a clausal structure is built up to the TP level in Latin (i.e., in all finite and infinitival clauses), vP moves to [Spec,TP]. TP itself is invariably head-initial, though, even in surface syntax, since T is linearized to the left of (the overt content of) its AspP complement (see (26) and (28)). On the syntax of Latin clauses containing auxiliaries (which are not directly relevant to this article), see Z&K: 13–14, fn. 19.

On this analysis, the Person and Number probes in a finite clause are on Voice in Latin – not on T, as in English. (The dotted arrow depicts Agree.) This component of the analysis receives some crosslinguistic support from Lemon’s (2024) convincing arguments that the Person and Number probes in Uab Meto (which, like Latin, has a nominative/accusative agreement alignment) are on a head just above Voice, which he calls Agr. It also offers a straightforward explanation for the otherwise puzzling observation that some Latin verb forms obey, and others appear to disobey, Baker’s (1985: 375) Mirror Generalization.[20] To see this, consider (27):

| laud-ē-t-ur |

| praise-prs.sbjv-3sg-pass |

| ‘(that) he/she/it may be praised’ |

| (adapted from Z&K: 8) |

In (27), the passive Voice morpheme -ur surfaces farther from the root laud- ‘praise’ than does the present tense/subjunctive mood portmanteau -ē (see Baker 2014: 8–9; Cinque 1999: 197, citing Calabrese 1985; Calabrese 2019: Sect. 3.4.4.2; and Embick 2000: 196–199). This superficially appears to violate the Mirror Generalization, since Voice is crosslinguistically lower in clause structure than T/Mood. But it is a straightforward consequence of the analysis of Latin clause structure adopted here:

| Derivation of laudētur ‘(that) he/she/it may be praised’ |

|

| (adapted from Z&K: 921) |

- 21

On Z&K’s analysis, the Latin passive Voice head undergoes postsyntactic Fission when its Person and Number features acquire certain values (but not when they acquire others). The result of this Fission is shown anticipatorily in (28). Z&K’s overall analysis nearly complies with the tenets of Morphology as Syntax (see the references under (4)), a framework that seeks to eliminate specifically morphological operations, attributing their effects to independently necessary syntactic operations. However, the analysis would come closer to complying with those tenets if the Fission component were eliminated, since the linear sequences of exponents sometimes taken to be produced by Fission might in principle actually be produced by External and Internal Merge. The account’s Fission component could be eliminated by taking the Person and Number probes to be on an Agr head distinct from Voice, exactly as Lemon (2024) does for Uab Meto. (On the possible eliminability of Fission, see also Marantz 2019.) This alternative, though promising, will not be pursued here: nothing below will turn on these matters.

As shown in (26) and (28), Z&K also posit that Voice’s probe features trigger Agree (Chomsky 2000, 2001). However, Hornstein (2009: Ch. 6) gives extremely interesting conceptual and empirical arguments that (long-distance) Agree should be eliminated in favor of Local Agree (see also Collins 2017: Sect. 8). It would be worthwhile to determine whether the analysis of Latin clause structure adopted here is compatible with Local Agree, but that would take us too far afield here.

As (28) shows, the reason passive Voice surfaces farther from the root than does T in (27) is that Voice is stranded by vP-movement to [Spec,TP].

On this analysis, Latin does obey the Mirror Generalization, despite appearances, but it must be understood as a generalization about structures formed by operations on heads (e.g., Asp-to-T movement, as in (26)): phrasal movement can result in apparent violations of it (see Z&K: 10 for references). The analysis also has the consequence that all Latin finite verb forms, whether they transparently obey the Mirror Generalization or superficially appear to violate it, share the simple derivation just laid out, involving one step of head movement (Asp to T) and one step of phrasal movement (vP to [Spec,TP]) (see Z&K: appendix). See Z&K for further discussion of derivations like (26) and (28) (Z&K: 7–8) and for several strands of syntactic evidence, independent of morpheme order, in favor of the analysis of Latin clause-building adopted here (Z&K: Sect. 5).

4.2 The syntax of radical tmesis

Now that we have an analysis of the derivation of Latin finite clauses, we can proceed to show how our basic derivation, in conjunction with independently motivated further applications of Internal Merge, can account for the constituent orders that radical tmesis produces. To that end, let us consider the derivation of (5) (repeated in (29)) in detail; the other radical tmesis derivations to be considered here are very similar to that one.

| saxō | cere- | comminuit | -brum |

| rock.abl | sk- | crushes | -ull.acc |

| ‘He crushed his skull with a rock.’ (Ennius, Annales 609 [Vahlen]) | |||

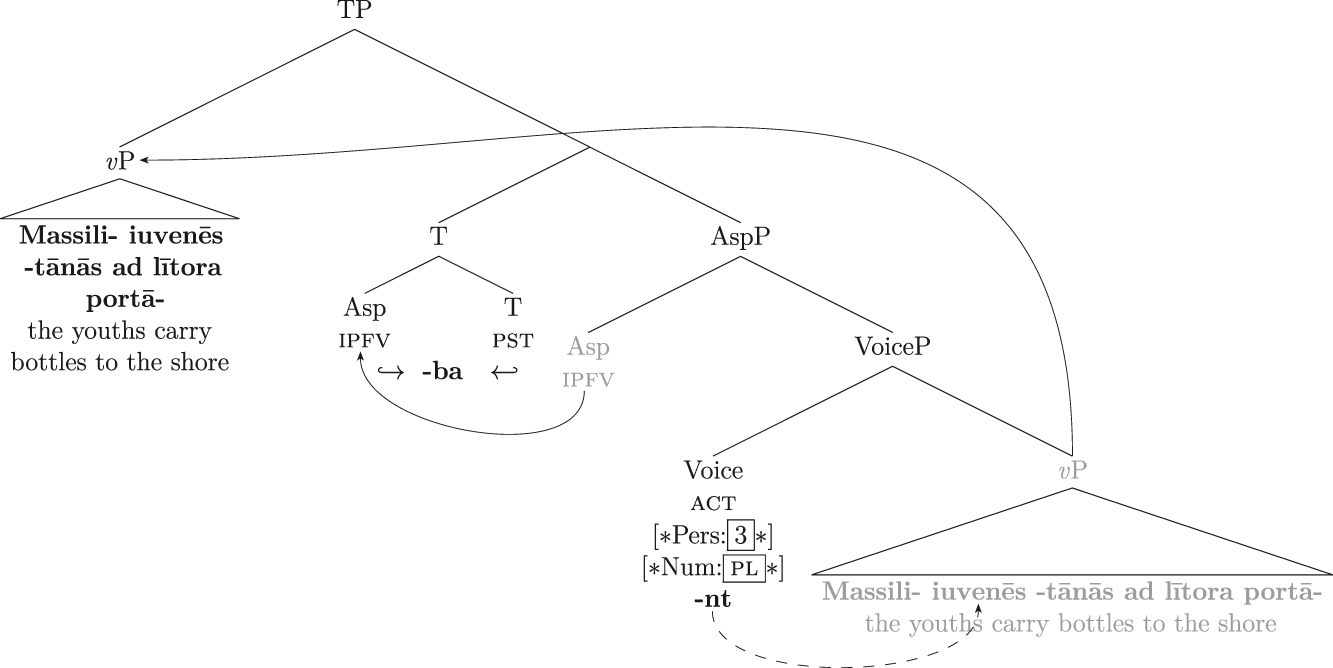

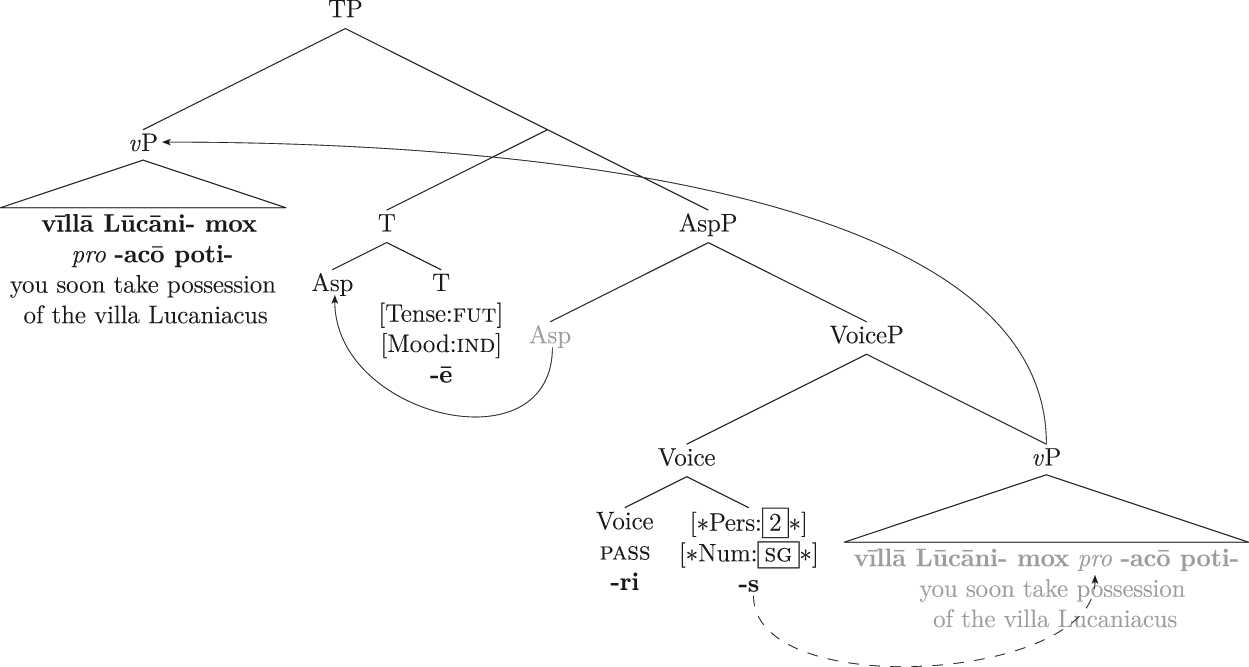

Example (29) is derived as follows. First, the structure in (30) is built:

| Derivation of (29), part 1 |

In (30), the root

Next, the root

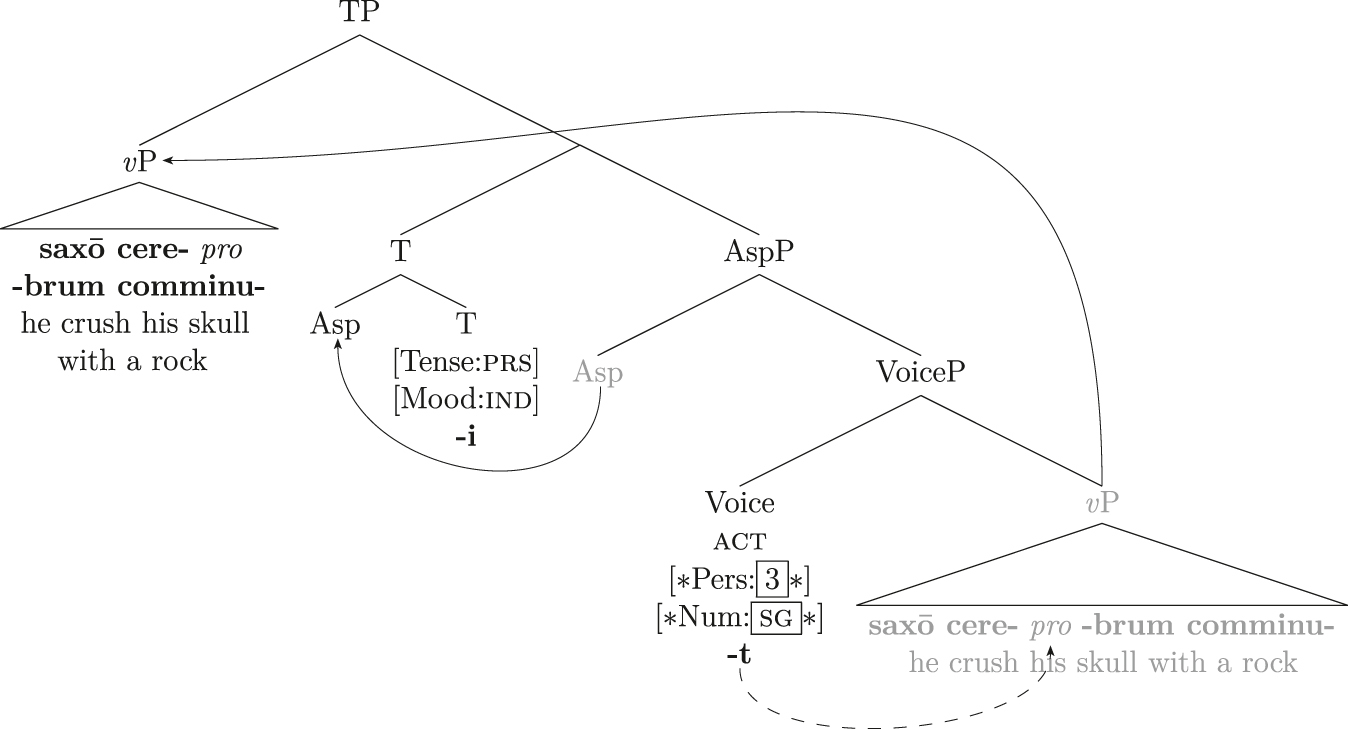

The derivation continues as follows:

| Derivation of (29), part 2 |

In (31), as usual, Voice agrees in Person and Number with the highest accessible nominal (here pro ‘he’); Asp moves to T; and vP moves to [Spec,TP].

The final portion of the derivation unfolds as follows:

| Derivation of (29), part 3 |

In (32), two heads are merged in above TP: a Fin(iteness) head[25] (Rizzi 1997) and a G(round) head (cf. Bianchi and Zamparelli 2004: 319; Poletto and Pollock 2004; see also Hulk and Pollock 2001: 9 and Kayne and Pollock 2001: 118), whose specifier is interpreted as conveying backgrounded or deemphasized information. G bears a [•X•] feature, which attracts a constituent – in this derivation, the remnant KP -brum – to [Spec,GP], which is taken here to be linearized to the right.[26] Crucially, we need not stipulate that a constituent that moves to [Spec,GP] bears an ad hoc information-structure feature [backgrounded] or the like, which would violate the Inclusiveness Condition (Chomsky 1995b): rather, such a constituent is interpreted as backgrounded/deemphasized in virtue of occurring in [Spec,GP] (owing to the denotation of G), so [•X•] suffices to trigger the movement as such. See Chomsky et al. (2019: 237–238, 250) and Chomsky (2020: 165) for similar arguments; theirs are cashed out in a Free Merge framework rather than in the feature-driven Merge framework adopted here, but little will turn on this analytical difference.

The GP component of the analysis is independently supported by the observation that backgrounded/deemphasized constituents can surface right-peripherally quite generally in Latin, including in prose. Thus, in (33), puellam ‘the girl’ is backgrounded (note that it conveys old information, given the presence of sorōris ‘of his sister’ in the first sentence), and it surfaces right-peripherally:

| Movet | ferōcı̄ | iuvenı̄ | animum | conplōrātiō | sorōris … |

| stirs | fierce.dat | youth.dat | spirit.acc | lamentation.nom | sister.gen |

| Strictō | itaque | gladiō | simul | verbı̄s | |

| having.been.drawn.m.abl | and.so | sword.abl | at.the.same.time | words.abl | |

| increpāns | trānsfı̄git | puellam. | |||

| rebuking | pierces.through | girl.acc | |||

| ‘The lamentation of his sister angered the fierce young man […] And so, drawing his sword, while shouting reproaches at her, he ran it through the girl.’ (Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 1.26.3) | |||||

| (adapted from Devine and Stephens 2006: 17) | |||||

And in (34), mundō ‘the world’ is backgrounded (it too conveys old information, given the presence of mundum ipsum ‘the world itself’ in the first finite clause), and it also surfaces right-peripherally:

| … | modo | mundum | ipsum | deum | dı̄cit | esse, | modo |

| now | world.acc | itself.m.acc | god.acc | says | to.be | now | |

| alium | quendam | praeficit | mundō … | ||||

| another.m.acc | certain.m.acc | puts.in.charge.of | world.dat | ||||

| ‘…now he says the world itself is a god, now he puts someone else in charge of the world…’ (Cicero, De Natura Deorum 1.33) | |||||||

| (adapted from Devine and Stephens 2006: 178) | |||||||

For many more examples of backgrounded/deemphasized constituents surfacing right-peripherally in Latin, see Devine and Stephens (2006: 129 et passim).[27]

The GP component of the analysis is independently supported not only Latin-internally but also crosslinguistically. It is lent further plausibility by Cantonese sentences like (35)–(37):

| Zoeng | Saam | tingjat ___4 | heoi | teng | jincoengwui | lo1[Adv | dosou]4. |

| Zoeng | Saam | tomorrow | go | listen | concert | sp | probably |

| ‘Zoeng Saam is probably going to a concert tomorrow.’ | |||||||

| (adapted from Lee 2017: 62) | |||||||

| Zoeng | Saam ___5 | maai-zo | bou | soenggei | aa3 [PP | hai | dinnou | zit]5. |

| Zoeng | Saam | buy-pfv | clf | camera | sp | at | computer | festival |

| ‘Zoeng Saam bought a camera at the computer festival.’ | ||||||||

| (adapted from Lee 2017: 62) | ||||||||

| Zoeng | Saam | jatzik | dou ___6 | heoi | duksyu | ge2 | [V | soeng]6. |

| Zoeng | Saam | all.the.time | all | go | study | sp | want | |

| ‘Zoeng Saam wants to go study all the time.’ | ||||||||

| (adapted from Lee 2017: 62) | ||||||||

In such examples, the constituent that surfaces sentence-finally, to the right of the sentence particle, is interpreted as defocused: it cannot be a wh-phrase or an information focus; bear focal stress (Lee 2017: Sect. 3.1.1, 2020: 140–141); be a contrastive focus (Lee 2020: 141, 2021: 108–109); or be the associate of lin … dou ‘even’ (Lee 2020: 142). For further discussion of defocalization, see Lee (2017: Sects. 3.1.2–3.2), Lee (2020), and references cited there. Notably, the sentence-final position for defocalized elements in Cantonese is not categorially restricted: it can host an adverb (see (35)), a PP (see (36)), a modal verb (see (37)), other types of verbs (Lee 2021: 106), a CP complement (Lee 2017: 62), or a nominal object with or without a demonstrative (Lee 2017: 62; Lai 2019: 270) – exactly as expected if the head determining the relevant specifier position bears an underspecified [•X•] feature, as Lai (2019) essentially argues for Cantonese and as was argued above for Latin.[28]

The account’s GP component receives further crosslinguistic support from Turkish sentences involving postposing, like (38)–(39), if, as Takano (2014: 176) states (citing Erguvanlı 1984), “postposing in Turkish has the discourse function of backgrounding.”

| ___1 | Ali-ye | kitab-ı | verdi | Hasan1. |

| Ali-dat | book-acc | gave | Hasan | |

| ‘He i gave the book to Ali, Hasan i .’ | ||||

| (adapted from Kornfilt 2013: 206) | ||||

| ___2 ___3 | Kitab-ı | verdi | Hasan2 | Ali-ye3. |

| book-acc | gave | Hasan | Ali-dat | |

| ‘He gave the book to him, Hasan to Ali.’ | ||||

| (adapted from Kornfilt 2013: 207) | ||||

Further crosslinguistic empirical observations lending plausibility to the account’s GP component are given in Devine and Stephens (2006: 136) and works cited there.

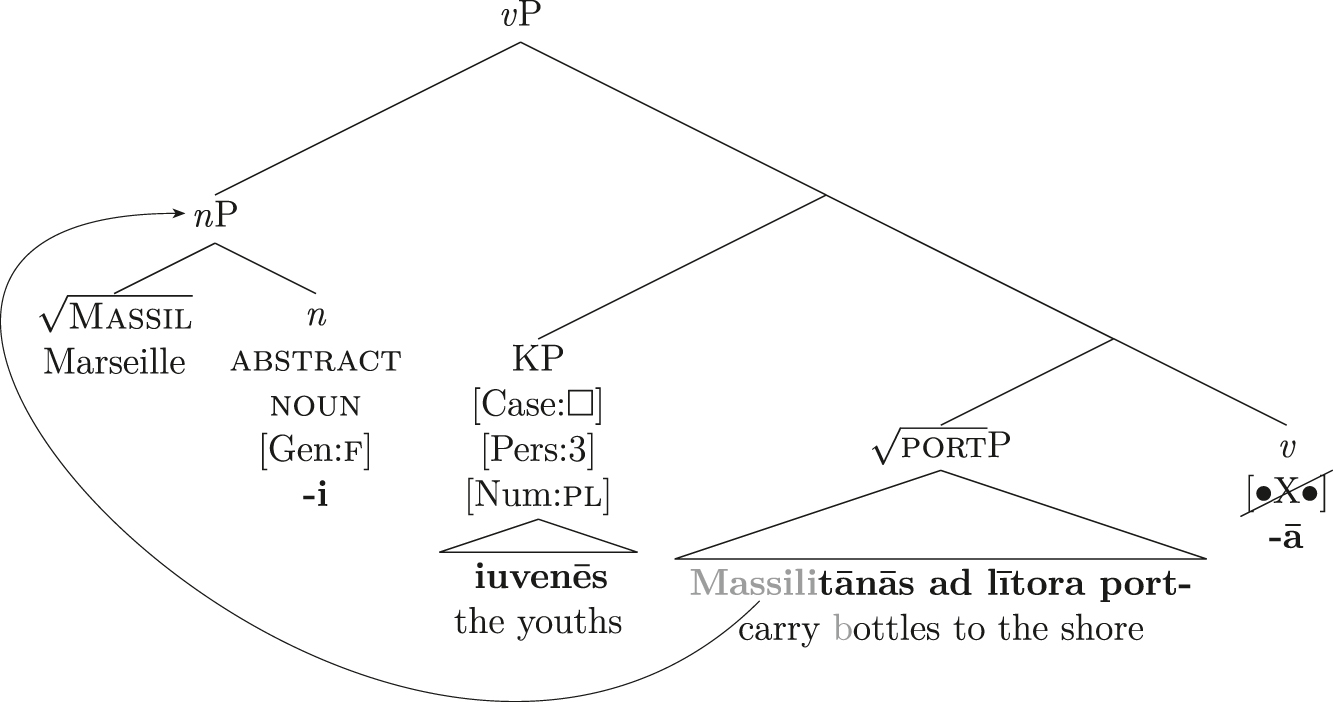

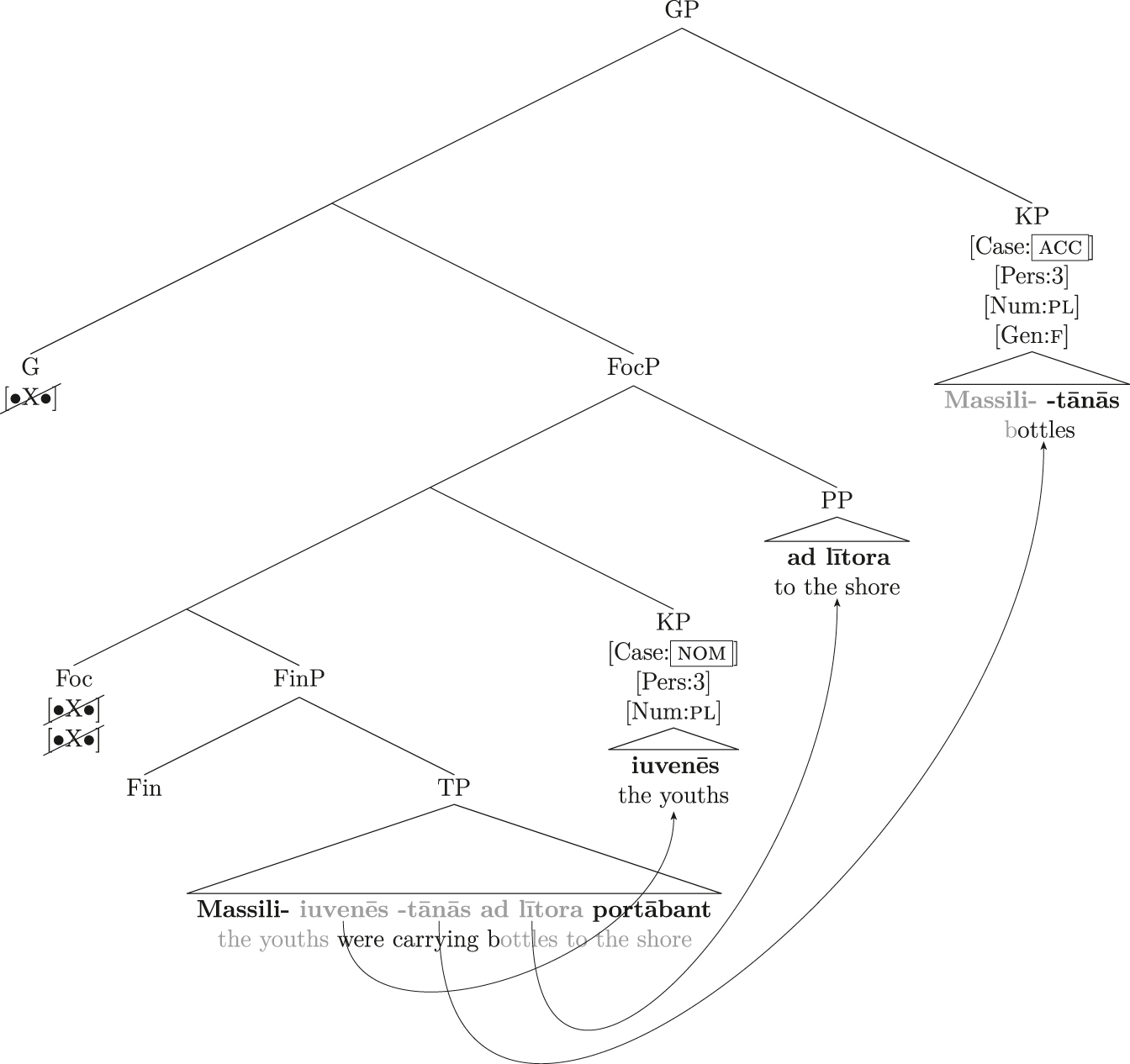

Returning to radical tmesis, the derivations of (6) and (8), both of which exemplify radical tmesis, are very similar to the derivation just examined (in (30)–(32)), so they can be presented quite efficiently.[29] Consider first (6), repeated here:

| Massili- | portābant | iuvenēs | ad | lı̄tora | -tānās. |

| b- | were.carrying | youths.nom | to | shores.acc | -ottles.acc |

| ‘The youths were carrying bottles to the shore.’ (Ennius, Annales 610 [Vahlen]) | |||||

Sentence (40) is derived as follows. First, the structure in (41) is built:

| Derivation of (40), part 1 |

In (41),

| Derivation of (40), part 2 |

As (42) shows, the next head merged in is v – which selects the maximal projection of

| Derivation of (40), part 3 |

In (43), Voice agrees in Person and Number with the closest accessible KP, here iuvenēs ‘the youths’. Asp moves to T; imperfective Asp and past T are jointly realized by the portmanteau exponent -ba. As usual, vP moves to [Spec,TP]. The final portion of the derivation is shown in (44). (As above, the precise mechanism by which the external argument gets nominative case is set aside.)

| Derivation of (40), part 4 |

In this derivation, as (44) shows, three heads are merged in above TP: Fin; Foc(us) (Rizzi 1997; Servidio 2009); and G. The KP iuvenēs ‘the youths’ and PP ad lı̄tora ‘to the shore’ surface to the right of the verb word portābant ‘were carrying’; this is taken here to be due to movement of these arguments to specifier positions of Foc[31] and linearization of the resulting specifiers to the right (as in Kirundi; see Ndayiragije 1999). (That specifiers of FocP projections can alternatively be linearized to the left in Latin is suggested by the empirical observations in Devine and Stephens 2006: Sects. 3.1, 3.3.)

The precise features and operations responsible for the placement of those two arguments will not be investigated further here, as they are not directly relevant to the radical tmesis in (40). What is important here is that [•X•] on G attracts the remnant KP -tānās to [Spec,GP] – which, as in the previous derivation, is linearized to the right – thus yielding the constituent order observed.

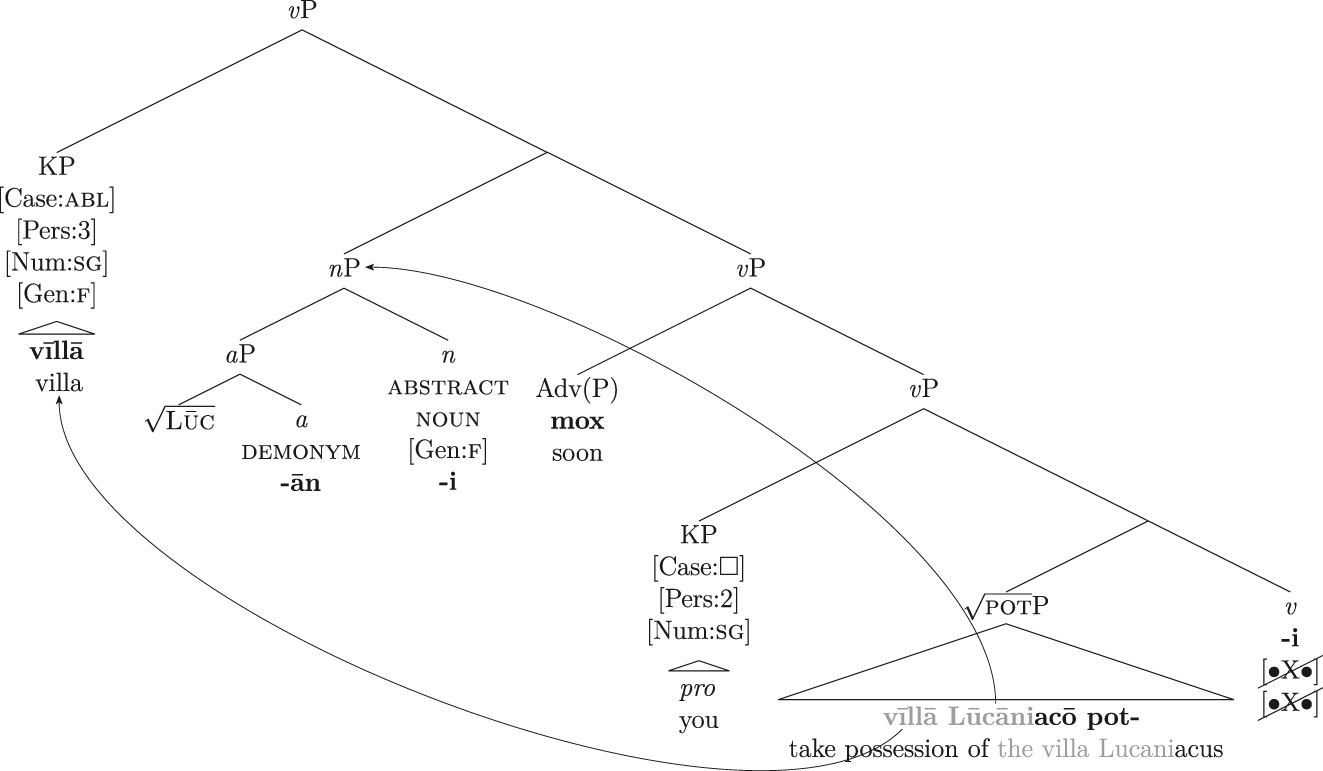

Finally, consider (8), repeated here:

| Vı̄llā | Lūcāni- | mox | potiēris | -acō. |

| villa.abl | Lucani- | soon | you.will.take.possession.of | -acus.abl |

| ‘You will soon become the owner of the villa Lucaniacus.’ (Ausonius, Epistle 5, 35) | ||||

Sentence (45) is derived as follows. First, the structure in (46) is built:

| Derivation of (45), part 1 |

In (46), vı̄llā Lūcāniacō ‘the villa Lucaniacus’ is treated for concreteness as a R(elator) P(hrase) (Den Dikken 2006), in which the KPs vı̄llā ‘villa’ and Lūcāniacō ‘Lucaniacus’ are taken to be the specifier and the complement, respectively, of R. The internal structure of phrases like vı̄llā Lūcāniacō (or the letter A) deserves further scrutiny, but that would take us too far astray here (see Jackendoff 1984 for an initial investigation).[32] The RP vı̄llā Lūcāniacō ‘the villa Lucaniacus’ is merged as the complement of

| Derivation of (45), part 2 |

In (47), v selects the maximal projection of the root and the external-argument KP (pro ‘you’), forming a vP, to which the adverb mox ‘soon’ adjoins. The hypothesis that it adjoins to vP in (47), rather than to some larger verbal constituent, receives crosslinguistic support from the observation that, in English, soon can be carried along under vP-preposing:[33]

| a. But though you most certainly will become the owner of the villa Lucaniacus soon, I suspect that you’re going to continue to live mostly in the city. |

| b. But [ vP become the owner of the villa Lucaniacus soon]1 though you most certainly will ___1, I suspect that you’re going to continue to live mostly in the city. |

In addition, two constituents scramble to the left edge of vP: [ nP Lūcāni-] ‘Lucania’ and [KP vı̄llā] ‘villa.abl’. These two steps of scrambling are taken here for concreteness to be driven by [•X•] features on v. The derivation continues:

| Derivation of (45), part 3 |

In (49), as usual, Voice agrees in Person and Number with the closest accessible nominal (here pro ‘you’),[34] Asp moves to T, and vP moves to [Spec,TP]. The final portion of the derivation unfolds as follows:

| Derivation of (45), part 4 |

In (50), two heads are merged in above TP: Fin and G. The latter bears a [•X•] feature, which attracts the remnant KP -acō to [Spec,GP].[35] This specifier is, as usual, linearized to the right, deriving the constituent order observed.[36]

5 Conclusions

Our empirical starting point here was the phenomenon of tmesis, wherein a structure traditionally considered a single “word” is split into two pieces that surface in distinct syntactic positions, separated by overt material outside the “word.” Canonical tmesis, in which the cut clearly occurs at a morpheme boundary, is theoretically unproblematic in nonlexicalist frameworks; what initially appears far more troublesome theoretically is radical tmesis, in which it is not obvious at first that there is any morpheme boundary at the cut.

In the face of that recalcitrant phenomenon, this article has argued that, contrary to appearances, no second, constituency-insensitive route to displacement need be posited. The argument proceeded in two steps. First, it was shown that, despite appearances, the cut in radical tmesis does occur at a morpheme boundary – which, in a nonlexicalist framework, means at a syntactic boundary – so radical tmesis could in principle be analyzed as a product of Internal Merge. It was then argued that radical tmesis not only could but indeed can be analyzed as a product of Internal Merge: the constituent orders it gives rise to can be analyzed as products of applications of Internal Merge (and other operations, e.g., External Merge and Adjoin) that are independently motivated on Latin-internal and/or crosslinguistic grounds.

The results of this investigation have at least two broader theoretical implications that go beyond the study of tmesis itself. First, they support nonlexicalist approaches to morphosyntax. If the structures traditionally considered “words” were taken to be built in a presyntactic morphological component and to be syntactically atomic, as per the Lexicalist Hypothesis (Bresnan and Mchombo 1995; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; see Bruening 2018b: 1 for further references), then their subconstituents would be incorrectly predicted to be unable to undergo Internal Merge (i.e., to be syntactically displaced). A defender of the Lexicalist Hypothesis might try to reconcile it with the licitness of radical tmesis by analyzing the latter as a phonological and not a syntactic phenomenon, but such an analysis would miss the generalization that the cut in radical tmesis occurs at a morpheme boundary, which suggests that radical tmesis is not fundamentally phonological in nature.[37] But in a nonlexicalist framework, there is a single generative engine – the syntax, which builds both “words” and phrases – so the licitness of radical tmesis is unsurprising. The analysis developed here has been couched in a version of Morphology as Syntax (Collins and Kayne 2023; Crippen 2023; Julien 2022; Koopman 2020b; Ntelitheos 2022; Zyman 2020, 2023b; Z&K; and references therein),[38] but it is compatible with other nonlexicalist frameworks as well (see the discussion under (4)).

Secondly, as noted, the existence of radical tmesis does not – despite appearances – force us to posit a second, constituency-insensitive displacement operation (the “X” from under (8)). Adding X to the theory would be conceptually undesirable not only on general grounds of theoretical parsimony but also because, if it were added, there would then be two operations yielding displacement – X and Internal Merge – and, despite the resemblance between them, X could not be reduced to Internal Merge, since the latter operates only on constituents (cf. Hornstein 2009: 65 and Davis 2023). As we have seen, however, closer scrutiny reveals that there are good reasons to analyze radical tmesis as a product of Internal Merge, a subcase of the independently motivated fundamental structure-building operation Merge – a result that is theoretically welcome from a minimalist perspective (cf. Chametzky 1996: 169).

Funding source: Franke Institute for the Humanities, University of Chicago

Award Identifier / Grant number: Faculty Residential Fellowship (2023–2024)

Acknowledgments

Many thanks, for valuable discussion, to numerous colleagues, especially Karlos Arregi, Nicholas Bellinson, Dan Brodkin, Jackson Confer, Bob Freidin, Daniel Harbour, Andrew Hedding, Matt Hewett, Christopher Husch, Nick Kalivoda, Zach Lebowski, Andrew McInnerney, Jason Merchant, Kate Mooney, Gereon Müller, Noémie Ndiaye, Ross Rauber, Steven Rings, Parker Robbins, Reagan Sparks, Oliver Sweet, Anna Tchetchetkine, Gary Thoms, Dan Walden, the anonymous reviewers of this article, and Probus Co-Editor Jairo Nunes. The usual disclaimers apply.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was generously supported by a Faculty Residential Fellowship (2023–2024) from the University of Chicago’s Franke Institute for the Humanities.

-

Data availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Agbayani, Brian & Chris Golston. 2016. Phonological constituents and their movement in Latin. Phonology 33(1). 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0952675716000026.Search in Google Scholar

Ahn, Byron. 2015. There’s nothing exceptional about the phrasal stress rule Ms. Boston University.Search in Google Scholar

Aicher, Peter. 1989. Ennius’ dream of Homer. The American Journal of Philology 110(2). 227–232. https://doi.org/10.2307/295173.Search in Google Scholar

Aitha, Akshay. 2023. On parallelism between extended projections: The view from the Telugu noun phrase Ms. University of Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

Bailey, Laura. 2010. Latin word order and the EPP. Handout from CamLing. Cambridge University.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Mark. 1985. The Mirror Principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16(3). 373–415.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, James. 2014. Aspects of the evolution of the Latin/Romance verbal system. Cambridge: Trinity Hall M.Phil. thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana & Ur Shlonsky. 1995. The order of verbal complements: A comparative study. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13. 489–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00992739.Search in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Valentina & Roberto Zamparelli. 2004. Edge coordinations: Focus and conjunction reduction. In David Adger, Cécile De Cat & George Tsoulas (eds.), Peripheries: Syntactic edges and their effects, 313–327. Dordrecht: Kluwer.10.1007/1-4020-1910-6_13Search in Google Scholar

Billy, Pierre-Henri. 2016. Les noms de lieux gallo-romains dans leur environnement. In Carole Hough & Daria Izdebska (eds.), ‘Names and their environment’: Proceedings of the 25th International Congress of Onomastic Sciences, Glasgow, 25–29 August 2014, vol. 1: Keynote lectures: Toponomastics I, 93–107. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.Search in Google Scholar

Bishop, J. David. 1957. Comic tmesis in Ennius. The Classical Weekly 50(11). 148–150. https://doi.org/10.2307/4343933.Search in Google Scholar

Bittner, Maria & Ken Hale. 1996. The structural determination of case and agreement. Linguistic Inquiry 27(1). 1–68.Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2002. A-movement and the EPP. Syntax 5(3). 167–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9612.00051.Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2004. Be careful where you float your quantifiers. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22(4). 681–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-004-2541-z.Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2018. On movement out of moved elements, labels, and phases. Linguistic Inquiry 49(2). 247–282.10.1162/LING_a_00273Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2020a. On smuggling, the freezing ban, labels, and tough-constructions. In Adriana Belletti & Chris Collins (eds.), Smuggling in syntax, 96–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0004Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2020b. On the coordinate structure constraint and the adjunct condition. In András Bárány, Theresa Biberauer, Jamie Douglas & Sten Vikner (eds.), Syntactic architecture and its consequences II: Between syntax and morphology, 227–258. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bresnan, Joan & Sam A. Mchombo. 1995. The lexical integrity principle: Evidence from Bantu. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13. 181–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00992782.Search in Google Scholar

Brody, Michael. 2000. Mirror theory: Syntactic representation in perfect syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 31(1). 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438900554280.Search in Google Scholar

Bruening, Benjamin. 2018a. CPs move rightward, not leftward. Syntax 21(4). 362–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12164.Search in Google Scholar

Bruening, Benjamin. 2018b. The lexicalist hypothesis: Both wrong and superfluous. Language 94(1). 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2018.0000.Search in Google Scholar

Bruening, Benjamin. 2018c. Brief response to Müller. Language 94(1). e67–e73. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2018.0015.Search in Google Scholar

Byrne, Marie José. 1916. Prolegomena to an edition of the works of Decimus Magnus Ausonius. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Byron, David. 2019. Extraction from conjuncts in Khoekhoe: An argument for cyclic linearization. Chicago: University of Chicago MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Calabrese, Andrea. 1985. The Mirror Principle and the Latin passive Ms. MIT.Search in Google Scholar

Calabrese, Andrea. 2019. Morphophonological investigations: A theory of PF. From syntax to phonology in Italian and Sanskrit verb forms Ms. University of Connecticut.Search in Google Scholar

Carnie, Andrew & Eithne Guilfoyle (eds.). 2000. The syntax of verb initial languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Carnie, Andrew, Heidi Harley & Sheila Ann Dooley. 2005. Verb first: On the syntax of verb-initial languages. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.73Search in Google Scholar

Chametzky, Robert A. 1996. A theory of phrase markers and the extended base. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chametzky, Robert. 2008 [2003]. Phrase structure. In Randall Hendrick (ed.), Minimalist syntax, 192–226. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470758342.ch5Search in Google Scholar

Chase, Thomas (ed.). 1874. The works of Horace. Philadelphia: Eldredge & Brother.Search in Google Scholar

Chaves, Rui P. 2008. Linearization-based word-part ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 31. 261–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9040-3.Search in Google Scholar

Chaves, Rui P. 2014. On the disunity of right-node raising phenomena: Extraposition, ellipsis, and deletion. Language 90(4). 834–886. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2014.0081.Search in Google Scholar

Chaves, Rui P. 2018. Freezing as a probabilistic phenomenon. In Jutta Hartmann, Marion Knecht, Andreas Konietzko & Susanne Winkler (eds.), Freezing: Theoretical approaches and empirical domains, 403–429. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9781501504266-013Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1964. The logical basis of linguistic theory. In Horace G. Lunt (ed.), Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Linguists, Cambridge, Mass., August 27–31, 1962. The Hague: Mouton and Co.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1973. Conditions on transformations. In Stephen R. Anderson & Paul Kiparsky (eds.), A festschrift for Morris Halle, 232–286. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1995a. Bare phrase structure. In Héctor Campos & Paula Kempchinsky (eds.), Evolution and revolution in linguistic theory: Studies in honor of Carlos P. Otero, 51–109. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1995b. The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Roger Martin, David Michaels & Juan Uriagereka (eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, 89–155. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Michael Kenstowicz (ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language, 1–52. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4056.003.0004Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Adriana Belletti (ed.), Structures and beyond, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195171976.003.0004Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero & Maria Luisa Zubizarreta (eds.), Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, 133–166. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/7713.003.0009Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 2020. Puzzles about phases. In Ludovico Franco & Paolo Lorusso (eds.), Linguistic variation: Structure and interpretation, 163–168. Boston & Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781501505201-010Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam, Ángel J. Gallego & Dennis Ott. 2019. Generative grammar and the faculty of language: Insights, questions, and challenges. Catalan Journal of Linguistics. 229–261.Search in Google Scholar

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195115260.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris. 2017. Merge(X,Y) = {X,Y}. In Leah Bauke & Andreas Blümel (eds.), Labels and roots, 47–68. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9781501502118-003Search in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris. 2020. A smuggling approach to the dative alternation. In Adriana Belletti & Chris Collins (eds.), Smuggling in syntax, 96–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris & Erich Groat. Forthcoming. Distinguishing copies and repetitions. In Kleanthes K. Grohmann & Evelina Leivada (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of minimalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris & Richard S. Kayne. 2023. Towards a theory of morphology as syntax. Studies in Chinese Linguistics 44(1). 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2478/scl-2023-0001.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris & Edward Stabler. 2016. A formalization of minimalist syntax. Syntax 19(1). 43–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12117.Search in Google Scholar

Conrad, Carl. 1965. Traditional patterns of word-order in Latin epic from Ennius to Vergil. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 69. 195–258. https://doi.org/10.2307/310783.Search in Google Scholar

Cordier, André. 1940. Mots mutilés et sectionnés dans Ennius: Ennius justifié par Aristote. In Mélanges de philologie, de littérature et d’histoire offerts à Alfred Ernout, 89–96. Paris: Klinksieck.Search in Google Scholar

Crippen, James A. 2023. Tlingit verb morphology is syntax. Paper presented at Morphology as Syntax 3. Montréal: Université du Québec à Montréal, 15–16 September.Search in Google Scholar

Dahlstrom, Amy. 1987. Discontinuous constituents in Fox. In Paul Kroeber & Robert Moore (eds.), Native American languages and grammatical typology. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Linguistics Club.Search in Google Scholar

Danckaert, Lieven. 2012. Latin embedded clauses: The left periphery. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.184Search in Google Scholar

Danckaert, Lieven. 2014. The derivation of Classical Latin Aux-final clauses: Implications for the internal structure of the verb phrase. In Karen Lahousse & Stefania Marzo (eds.), Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2012: Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’ Leuven 2012, 141–160. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/rllt.6.07danSearch in Google Scholar

Danckaert, Lieven. 2017a. The development of Latin clause structure: A study of the extended verb phrase. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198759522.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Danckaert, Lieven. 2017b. Subject placement in the history of Latin. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 16. 125–161. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/catjl.209.Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Colin P. B. 2023. The unextractability of English possessive pronouns: On portmanteau formation and the syntax-morphology interface Ms. University of Konstanz.Search in Google Scholar

Debouy, Estelle. 2012. Édition critique, traduction et commentaire des fragments d’atellanes. Nanterre: Université Paris X – Nanterre dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Dékány, Éva. 2018. Approaches to head movement: A critical assessment. Glossa 3(1). 1–43. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.316.Search in Google Scholar

den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. Relators and linkers: The syntax of predication, predicate inversion, and copulas. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/5873.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Devine, A. M. & Laurence D. Stephens. 2006. Latin word order: Structured meaning and information. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195181685.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Devine, A. M. & Laurence D. Stephens. 2019. Pragmatics for Latin: From syntax to information structure. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780190939472.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Di Sciullo, Anna Maria & Edwin Williams. 1987. On the definition of word. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Embick, David. 2000. Features, syntax, and categories in the Latin perfect. Linguistic Inquiry 31(2). 185–230. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438900554343.Search in Google Scholar

Epstein, Samuel David, Erich M. Groat, Ruriko Kawashima & Hisatsugu Kitahara. 1998. A derivational approach to syntactic relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Erguvanlı, Eser Emine. 1984. The function of word order in Turkish grammar. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Faust, Manfred. 1970. Zur Erforschung des Altlateins in den westlichen Provinzen. Glotta 48(1/2). 129–140.Search in Google Scholar

Freidin, Robert. 2016. Chomsky’s linguistics: The goals of the generative enterprise. Review of Peter Graff & Coppe van Urk (eds.), Chomsky’s linguistics. Language 92(3). 671–723.10.1353/lan.2016.0057Search in Google Scholar

Fruyt, Michèle. 1991. Mots fragmentés chez Ennius. Glotta 69(3/4). 243–246.Search in Google Scholar

Fukui, Naoki. 2011. Merge and Bare Phrase Structure. In Cedric Boeckx (ed.), The Oxford handbook of linguistic minimalism, 73–95. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199549368.013.0004Search in Google Scholar

Gaffiot, Félix. 2016 [1934]. Dictionnaire latin français, revised and augmented by Gérard Gréco, with Mark de Wilde, Bernard Maréchal & Katsuhiro Ôkubo. http://gerardgreco.free.fr/IMG/pdf/Gaffiot2016-komarov.pdf (accessed 14 December 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Giannoula, Mina. 2021. The nature of preverbs in Modern Greek. In Caitie Coons, Gabriella Chronis, Sofia Pierson & Venkat Govindarajan (eds.), Proceedings of the 20th Meeting of the Texas Linguistic Society, 56–75.Search in Google Scholar

Giannoula, Mina. 2023. Multiple preverbation: Stacking of preverbs. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 20(1). 64–88.Search in Google Scholar

Gianollo, Chiara. 2016. The Latin system of negation at the syntax-semantics interface. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 38. 115–135.Search in Google Scholar

Giles, John Allen. 1836. Quinti Enni, poetae inter Romanos vetustissimi, reliquiae quae extant omnes [All the remains that exist of the works of Quintus Ennius, the oldest poet among the Romans]. London: Bohn.Search in Google Scholar

Graf, Thomas. 2018. Why movement comes for free once you have adjunction. In Daniel Edmiston, Marina Ermolaeva, Emre Hakgüder, Jackie Lai, Kathryn Montemurro, Brandon Rhodes, Amara Sankhagowit & Michael Tabatowski (eds.), Proceedings of the 53rd annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS 53), 117–136. Chicago, IL: Chicago Linguistic Society.Search in Google Scholar

Groat, Erich. 1997. A derivational program for syntactic theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Hahn, E. Adelaide. 1947. The type calefacio. Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 78. 301–335. https://doi.org/10.2307/283501.Search in Google Scholar

Halle, Morris & Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection. In Kenneth Hale & Samuel Jay Keyser (eds.), The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, 111–176. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Halle, Morris & Alec Marantz. 1994. Some key features of Distributed Morphology. In Andrew Carnie, Heidi Harley & Tony Bures (eds.), Papers on phonology and morphology, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, 21, 275–288. Cambridge, MA: MIT, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, MITWPL.Search in Google Scholar

Harley, Heidi. 2008. The bipartite structure of verbs cross-linguistically (or: Why Mary can’t exhibit John her paintings). In Thaïs Cristófaro Silva & Heliana Mello (eds.), Conferências do V Congresso Internacional da Associação Brasileira de Linguística, 45–84. Belo Horizonte, Brazil: ABRALIN and FALE/UFMG.Search in Google Scholar

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory: Principles and case studies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Heck, Fabian & Gereon Müller. 2007. Extremely local optimization. In Erin Bainbridge & Brian Agbayani (eds.), Proceedings of the 34th Western Conference on Linguistics, 170–183. Fresno: Department of Linguistics, California State University.Search in Google Scholar

Hedding, Andrew A. & Michelle Yuan. 2025. Phase unlocking and the derivation of verb-initiality in San Martín Peras Mixtec. In Nikolas Webster, Yağmur Kiper, Richard Wang & Sichen Larry Lyu (eds.), Proceedings of the 41st West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 184–193. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hewett, Matthew. 2023. Types of resumptive Ā-dependencies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Hornstein, Norbert. 2009. A theory of syntax: Minimal operations and Universal Grammar. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511575129Search in Google Scholar

Huck, Geoffrey J. & Younghee Na. 1990. Extraposition and focus. Language 66(1). 51–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/415279.Search in Google Scholar

Hulk, Aafke & Jean-Yves Pollock. 2001. Subject positions in Romance and the theory of Universal Grammar. In Aafke C. J. Hulk & Jean-Yves Pollock (eds.), Subject inversion in Romance and the theory of Universal Grammar, 3–19. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195142693.003.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hunter, Tim. 2015. Deconstructing Merge and Move to make room for adjunction. Syntax 18(3). 266–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12033.Search in Google Scholar

Jackendoff, Ray. 1984. On the phrase the phrase ‘the phrase’. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 2(1). 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00233712.Search in Google Scholar

Jäger, Oskar. 1887. Nachlese zu Horatius. Cologne: Friedrich-Wilhelms-Gymnasium.Search in Google Scholar

Julien, Marit. 2022. Nominal paradigms in North Sámi. Paper presented at Morphology as Syntax II, UCLA, 10–11 June (virtual).Search in Google Scholar

Kalin, Laura. 2022. Infixes really are (underlyingly) prefixes/suffixes: Evidence from allomorphy on the fine timing of infixation. Language 98(4). 641–682. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2022.0017.Search in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard S. & Jean-Yves Pollock. 2001. New thoughts on Stylistic Inversion. In Aafke C. J. Hulk & Jean-Yves Pollock (eds.), Subject inversion in Romance and the theory of Universal Grammar, 107–162. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195142693.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Keyser, Samuel Jay & Thomas Roeper. 1992. Re: The Abstract Clitic Hypothesis. Linguistic Inquiry 23(1). 89–125.Search in Google Scholar

Kitahara, Hisatsugu. 1994. Target α: A unified theory of movement and structure-building. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kitahara, Hisatsugu. 1995. Target α: Deducing strict cyclicity from derivational economy. Linguistic Inquiry 26(1). 47–77.Search in Google Scholar

Kitahara, Hisatsugu. 1997. Elementary operations and optimal derivations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Koopman, Hilda. 2020a. On the syntax of the can’t seem construction in English. In Adriana Belletti & Chris Collins (eds.), Smuggling in syntax, 188–221. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0008Search in Google Scholar

Koopman, Hilda. 2020b. Towards a direct syntax phonology interface: A case study of Huave morphology-as-syntax. Paper presented at Syntactic Approaches to Morphology workshop, NYU, 4–5 December (virtual).Search in Google Scholar

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2013. Turkish. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315823652Search in Google Scholar

Kusmer, Leland Paul. 2015. (Re)labeling and constituency paradoxes: Remnant movement in Akan Ms. UMass Amherst.Search in Google Scholar

Lai, Jackie Yan-Ki. 2019. Parallel copying in dislocation copying: Evidence from Cantonese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 28. 243–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-019-09195-3.Search in Google Scholar

Laka, Itziar. 1990. Negation in syntax: On the nature of functional categories and projections. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Lamontagne, Greg & Lisa Travis. 1987. The syntax of adjacency. In Megan Crowhurst (ed.), Proceedings of the Sixth West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 173–186. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Landau, Idan. 2007. EPP extensions. Linguistic Inquiry 38(3). 485–523. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2007.38.3.485.Search in Google Scholar

Lebowski, Zach. 2021. CED effects in ascending and descending structures: Evidence from extraction asymmetries Ms. University of Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Tsz Ming. 2017. Defocalization in Cantonese right dislocation. Gengo Kenkyu 152. 59–87.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Tommy Tsz-Ming. 2020. Defending the notion of defocus in Cantonese. Current Research in Chinese Linguistics 99(1). 137–152.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Tsz-Ming. 2021. Right dislocation of verbs in Cantonese: A case of head movement to specifier. In Choi Lan Tong & Io-Kei Joaquim Kuong (eds.), Crossing-over: New insights into the dialects of Guangdong, 104–121. Macau: Hall de Cultura.Search in Google Scholar

Lemon, Tyler. 2024. Low nominative agreement in Uab Meto. In Robert Autry, Gabriela de la Cruz, Luis A. Irizarry Figueroa, Kristina Mihajlovic, Tianyi Ni, Ryan Smith & Heidi Harley (eds.), Proceedings of the 39th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL 39), 2, 600–608. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Lenchantin, Massimo. 1947. Review of Vittore Pisani. Grammatica Latina storica e comparativa. Athenaeum 25. 225–228.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, Charlton Thomas & Charles Short. 1879. A Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marantz, Alec. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. Proceedings of the 21st annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium (University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 4), 201–225.Search in Google Scholar

Marantz, Alec. 2019. Teaching Halle & Marantz (1993). https://wp.nyu.edu/morphlab/2019/08/10/teaching-halle-marantz-1993/ (accessed 6 July 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Mariotti, Scevola. 1988. Enn. Ann. 120 Skutsch (126 Vahlen). Bulletin Supplement (University of London, Institute of Classical Studies) 51. 82–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-5370.1988.tb02013.x.Search in Google Scholar

McCloskey, James. 2000. Quantifier float and wh-movement in an Irish English. Linguistic Inquiry 31(1). 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438900554299.Search in Google Scholar

Ménière, Prosper. 1858. Études médicales sur les poètes latins. Paris: Germer Baillière.Search in Google Scholar

Merchant, Jason. 2019. Roots don’t select, categorial heads do: Lexical-selection of PPs may vary by category. The Linguistic Review 36(3). 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2019-2020.Search in Google Scholar

Merula, Paulus. 1595. Quinti Enni, poetae cum primis censendi, Annalium libb. XIIX quae apud varios auctores superant fragmenta [Fragments of the eighteen books of the Annals of Quintus Ennius, a poet to be reckoned among the best, that survive in the works of various authors]. Leiden: Paetsius & Elzevirius.Search in Google Scholar

Mester, R. Armin. 1994. The quantitative trochee in Latin. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 12(1). 1–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00992745.Search in Google Scholar

Mowat, Robert. 1881. Review of Études grammaticales sur les langues celtiques. Première partie : introduction, phonétique et dérivation bretonnes, by H. d’Arbois de Jubainville. Revue Archéologique 42. 375–383.Search in Google Scholar

Ndayiragije, Juvénal. 1999. Checking economy. Linguistic Inquiry 30(3). 399–444. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438999554129.Search in Google Scholar

Newman, Elise. 2020. On the movement/(anti)agreement correlation in Romance and Mayan Ms. MIT.Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Mark. 2021. Case and K. https://morphosyntax.org/lx-theory/case-and-k/ (accessed 3 July 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Mark. Forthcoming. Nominal inflection in Distributed Morphology. In Artemis Alexiadou, Ruth Kramer, Alec Marantz & Isabel Oltra-Massuet (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of Distributed Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ntelitheos, Dimitrios. 2022. Compounding in Greek as phrasal syntax. Languages 7. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020151.Search in Google Scholar

Ott, Dennis. 2018. VP-fronting: Movement vs. dislocation. The Linguistic Review 35(2). 243–282. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2017-0024.Search in Google Scholar

Perrot, Jean. 1961. Les dérivés latins en -men et -mentum. Paris: Klinksieck.Search in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David. 1991. Zero syntax, vol. 2. Infinitives Ms. MIT.Search in Google Scholar

Pesetsky, David. 2021. Exfoliation: Towards a derivational theory of clause size Ms. MIT.Search in Google Scholar

Pike, Moss. 2011. Latin -tās and related forms. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Poletto, Cecilia & Jean-Yves Pollock. 2004. On the left periphery of some Romance wh-questions. In Luigi Rizzi (ed.), The structure of CP and IP, 251–296. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195159486.003.0009Search in Google Scholar

Popan, Marin. 2012. L’hyperbate nominale en latin. Construction, typologie, raison de texte. Toulouse: Université de Toulouse 2 – Le Mirail dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Poultney, James W. 1980. Observations on Ennius. The Classical Outlook 58(1). 3–5.Search in Google Scholar

Punske, Jeffrey. 2013. Three forms of English verb particle constructions. Lingua 135. 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2012.09.013.Search in Google Scholar

Raehse, Theobald. 1868. De re metrica Ausonii [On meter in Ausonius]. Berlin: Urbat.Search in Google Scholar

Rauber, Ross. 2022. Two paths to to Ms. NYU.Search in Google Scholar

van Riemsdijk, Henk C. & Edwin Williams. 1986. Introduction to the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Liliane Haegeman (ed.), Elements of grammar: A handbook of generative syntax, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.10.1007/978-94-011-5420-8_7Search in Google Scholar

Ross, John Robert. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Ludwig Ferdinand. 1840. C. Lucilii satirarum quae de libro nono supersunt disposita et illustrata [What remains of the ninth book of Gaius Lucilius’ Satires, arranged and explained]. Berlin: Nauck.Search in Google Scholar

Seneca the Elder. 1974. Declamations, Volume I: Controversiae, books 1–6. Translated by Michael Winterbottom. Loeb Classical Library 463. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.10.4159/DLCL.seneca_elder-controversiae.1974Search in Google Scholar

Serbat, Guy. 1975. Les dérivés nominaux latins à suffixe médiatif. Paris: Belles Lettres.Search in Google Scholar

Servidio, Emilio. 2009. A puzzle on auxiliary omission and focalization in English: Evidence for cartography. Snippets 19. 21–22.Search in Google Scholar

Starke, Michal. 2009. Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. Nordlyd 36(1). 1–6. https://doi.org/10.7557/12.213.Search in Google Scholar

Stringer, Stephanie. 2017. Enigmatic *-nt-stems: An investigation of the secondary -t- of the Greek neuter nouns in *-men- and *-r/n-. Montreal: Université de Montréal MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Takano, Yuji. 2014. A comparative approach to Japanese postposing. In Mamoru Saito (ed.), Japanese syntax in comparative perspective, 139–180. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199945207.003.0006Search in Google Scholar

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae. 1900–. Berlin (formerly Leipzig): De Gruyter (formerly Teubner). https://tll.degruyter.com (accessed 14 December 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Thoms, Gary & George Walkden. 2019. vP-fronting with and without remnant movement. Journal of Linguistics 55. 161–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002222671800004x.Search in Google Scholar

Timpanaro, Sebastiano. 2005. Contributi di filologia greca e latina. Florence: Università degli Studi di Firenze.Search in Google Scholar

Uth, Melanie. 2010. The rivalry of French -ment and -age from a diachronic perspective. In Monika Rathert & Artemis Alexiadou (eds.), The semantics of nominalizations across languages and frameworks, 215–243. Berlin & New York: Mouton De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110226546.215Search in Google Scholar

Vollmer, Friedrich. 1916. Iambenkürzung in Hexametern. Glotta 8(1/2). 130–137.Search in Google Scholar

Wexler, Kenneth & Peter W. Culicover. 1980. Formal principles of language acquisition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Willson, Jacob. 2021. The labeling ambiguity of Ibero-Romance clitics Ms. Arizona State University.Search in Google Scholar

Wood, Jim & Alec Marantz. 2017. The interpretation of external arguments. In Roberta D’Alessandro, Irene Franco & Ángel J. Gallego (eds.), The verbal domain, 255–278. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Zetzel, J. E. G. 1974. Ennian experiments. The American Journal of Philology 95(2). 137–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/294196.Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2018. Gestures and nonlinguistic objects are subject to the Case Filter. Snippets 32. 6–8. https://doi.org/10.7358/snip-2017-032-zyma.Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2020. Morphology as Syntax: A case study of the syntactic autonomy of prefixes. Paper presented at Syntactic Approaches to Morphology workshop, NYU, 4–5 December (virtual).Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2021. Antilocality at the phase edge. Syntax 24(4). 510–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12220.Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2023a. On the symmetry between Merge and Adjoin. Paper presented at a UCLA colloquium, 28 April.Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2023b. On the syntactic autonomy of theme vowels Ms. University of Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2024. On the definition of Merge. Syntax. 1–37. Early View. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12287.Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik & Nick Kalivoda. 2020. XP- and X0-movement in the Latin verb: Evidence from mirroring and anti-mirroring. Glossa 5(1). 1–38. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1049.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- A syntactic account of auxiliary selection in French

- Investigating locality constraints on wh-in situ in French: an experiment

- Focalization in situ and the absence of covert focus movement in Brazilian Portuguese

- French clausal ellipsis: types and derivations

- Radical tmesis is Internal Merge

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- A syntactic account of auxiliary selection in French

- Investigating locality constraints on wh-in situ in French: an experiment

- Focalization in situ and the absence of covert focus movement in Brazilian Portuguese

- French clausal ellipsis: types and derivations

- Radical tmesis is Internal Merge