Abstract

Proverbs (as Easy come, easy go) are a type of conventionalized multiword unit that can be used as separate, complete statements in speech or writing (Mieder 2007; Steyer 2015). The rationale of this study is to examine word class effects in online processing of proverbs. In Lückert and Boland (submitted), we reported facilitative effects associated with proverb keywords which suggests that word-level properties are active alongside properties of the level of the multiword unit. Previous research has shown that individual word classes have different effects in online language processing. Numerous studies revealed that verbs are processed more slowly (Cordier et al. 2013) and involve greater processing demands compared to nouns (Macoir et al. 2019). The results of the present study suggest that verbs rather than nouns facilitate proverb processing. A distributional analysis of word classes in proverb corpora implies a trend to prefer verbs over nouns in American English proverbs.

1 Introduction: The differential processing of nouns and verbs

Proverbs (e.g., A dog is man’s best friend, Diamonds are forever, or Easy come, easy go) are a type of conventionalized multiword unit that can be used as separate, complete statements in speech or writing (Mieder 2007; Steyer 2015). In everyday language, proverbs are typically used to comment on a situation, to give advice, and to share wisdom (Mieder 2007; Steyer 2015). In the past few decades, proverbs have increasingly been studied with empirical, quantitative methods in phraseological research (e.g., Čermák 2006; Chlosta and Grzybek 2005; Ďurčo 2005; Grzybek 2012; Lückert 2018b; Steyer 2015, Steyer 2017 etc.).

From a psycholinguistic perspective, proverbs are interesting because they are easily retrieved from memory despite being infrequent in actual use. The proverb Beauty is only skin deep, for example, has only 23 hits (.04 per mil) in COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English, a general language corpus with some 575,823,672 words). 94.9% of participants in an elicitation test were, however, familiar with the proverb (Chlosta and Grzybek 2005). There is a discrepancy between the token frequency of proverbs in language use (Arnaud and Moon 1993; Grzybek 2012; Lückert 2018b; Moon 1998) and their familiarity: infrequent proverbs can still feel very familiar to language users (Arnaud and Moon 1993; Grzybek 2012; Lückert 2018b).

Previous psycholinguistic research on proverbs has focused on proverb interpretation and metaphorical mappings (e.g., Duthie et al. 2008; Ferretti et al. 2007; Gibbs and Beitel 1995; Honeck 1997). Studies on online processing of multiword units have mainly focused on idioms (e.g., Horvath and Siloni 2009; Sprenger et al. 2006) and binomial ‘X and Y’ expressions (e.g., Morgan and Levy 2016; Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2011) rather than on proverbs. In Lückert and Boland (submitted), the processing of proverbs during lexical access (an early phase in comprehension and production) was examined. The focus was on frequency effects on the level of constituent words and the level of proverbs. The results of the study implied that word-level properties are active during processing of proverbs – the frequency of constituent words in the proverb context and in general language use influenced how participants performed in a self-paced reading paradigm and in recall tasks.

In the present article, it is examined whether word-level properties beyond the frequency dimension are involved in proverb processing. The effect of the syntactic categories of words – that is word classes (Haspelmath 2012: 110–111) – in proverbs shall be scrutinized. The proverb context is interesting because proverbs are used to express more or less complex messages succinctly and in an easily accessible and memorable way. Proverbs may thus benefit from constituent words that contribute a lot to the meaning of the multiword unit and that are quickly and reliably retrieved from memory. The rationale of the present paper is to identify which content word class(es) makes/make retrieval of the multiword unit easier and faster. It may be assumed that word classes that facilitate proverb processing have better chances of becoming part of lexicalized, entrenched structures. In the present study, corpus analysis and experimental data will be used to test this assumption.

Effects related to word class in online processing have attracted substantial interest in psycholinguistic research (e.g., Alario et al. 2002; Bultena et al. 2014; Sass et al. 2010; Shetreet et al. 2016; Sidhu et al. 2016). While many studies have examined single word processing of either nouns or verbs (e.g., Shetreet et al. 2016; Sidhu et al. 2016), some studies have explored the effect of phrase or sentence contexts (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014; Bürki et al. 2016; Meyer 1996; Sass et al. 2010; Schriefers 1992) or have focused on the differences between noun and verb processing (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014; Cordier et al. 2013; Macoir et al. 2019; Szekely et al. 2005; Vigliocco et al. 2011). In the present paper, the focus is on the effect of word classes in the processing of proverbs as a type of sentential context.

In Section 2, the current state of psycholinguistic research on word class effects will be discussed. Studies in the field agree that there are important differences in the processing of nouns and verbs (e.g., Macoir et al. 2019; Vigliocco et al. 2011) and that processing of nouns and verbs in single word processing differs from processing in sentential contexts (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014). Against the backdrop of the extant psycholinguistic research on word class effects, facilitative effects for nouns in proverb processing relative to other content word classes may be predicted.

In Section 3, findings on the distribution of the content word classes nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs in CAEP, a specialized proverb corpus (Corpus of American English Proverbs; includes 28,159 word tokens [2,562 word types] across 4,164 proverb variants [2,191 proverb types]; see Lückert 2018b)[1] and in a historical proverb collection from the 16th century (John Heywood’s collection, see Aurich 2012) will be reported. CAEP lists English-language proverbs found in modern American sources, databases etc. together with data on their frequency and familiarity. The distributional patterns of the four content word classes in the corpus will be examined so that we may learn which word classes are preferred in proverbs.

In Aurich (2012), historical corpus data has been analyzed that tracks the changes in English proverbs covering the Middle Ages and Early Modern times. In this study, I reported a trend towards increasing nominalization that was accompanied by an increasing use of proverb patterns/formulae (2012: 81). This finding from historical phraseology may also imply a facilitative effect for nouns in proverb processing.

To assess the assumed processing benefit for nouns in proverbs, results of an experimental study will be reported in Section 4.[2] Generalized linear mixed-effects models were fitted for the data from a reaction-time study to examine whether word class association of constituent words in proverbs predicts dependent measures in experimental tasks (response times in milliseconds, accuracy rates, recall position, and recall counts).[3] In Section 5, the central findings of the present paper will be summarized.

2 Word class effects in psycholinguistic research

Word class effects have been examined in previous experimental research.[4] The focus of earlier studies was on the content word classes nouns and verbs in single word processing and in processing in phrase or sentence contexts respectively. Nouns and verbs are distinct in several regards relating to semantics and structure and these distinct properties result in processing differences (Bultena et al. 2014; Vigliocco et al. 2011). As a result of these processing differences nouns and verbs differ in the age of acquisition: it has been observed that nouns are typically learned earlier than verbs (Bultena et al. 2014; Gentner 1981).

A further difference between noun and verb processing has been reported: nouns are often associated with object naming/knowledge, verbs with action naming/knowledge (also Haspelmath 2012: 115). As a result, different brain areas are more strongly activated by nouns and verbs. While the visual cortex is activated in noun processing, the motor cortex is more strongly activated in verb processing (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014; Pulvermüller et al. 1999). Despite differences in activation levels in different brain areas reported in previous research, nouns and verbs are not assumed to be associated with specialized neural or cognitive systems. A shared neural network is assumed to underly the processing of words from different grammatical categories (Vigliocco et al. 2011: 422).

Nouns and verbs differ substantially in their semantics. While nouns, for example, can be concrete, more imageable etc., verbs are generally considered to be more abstract (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014; Federmeier et al. 2000). Nouns tend to have more specific meanings relative to verbs (Bultena et al. 2014; Gentner, 1981). In contrast to noun meaning, verb meaning often depends on actual contexts of use – it can often be identified only in the context of complete sentences (Bultena et al. 2014; Gentner, 1981). While nouns are hierarchically organized within a taxonomic structure that involves superordinate and subordinate links, verbs tend not to be hierarchically organized (Macoir et al. 2019).

Nouns and verbs also differ in their structural properties. Verbs are considered more complex than nouns: the representations of verbs include information on the number and kinds of arguments a verb can take (Bultena et al. 2014; Macoir et al. 2019). Recent research on verb processing has shown that lexical retrieval of verbs involves exhaustive activation of all its complementation options (Shetreet et al. 2016).

The differences in semantic and structural complexity of nouns and verbs result in processing differences. These show in processing speed and demands. Verbs are, for example, processed more slowly relative to nouns (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014: 1216; Cordier et al. 2013: 21). Verbs are also assumed to be more difficult than nouns (Macoir et al. 2019; Vigliocco et al. 2011: 422). Macoir and colleagues have reviewed research on verb and noun production in individuals with various neurological disorders including the non-fluent variant of primary progressive aphasia, the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, and Parkinson disease (2019: 6). These studies report an impairment of verb production relative to noun production. Action naming was more difficult than object naming – this applied to both younger and older age groups.

The role of contexts has been discussed in research. Processing of nouns and verbs in sentence contexts differs from processing in single word processing tasks. Regarding verb processing, Bultena and colleagues reported that “verb cognate facilitation was not observed as a general effect across both tasks” and that “the presence of a sentence context did seem to reduce facilitatory processing of verb cognates” (2014: 1233). In a study on noun processing, Sass and colleagues found that associations facilitated naming in single word production – in sentence production, however, associations resulted in interference (2010: 447). Ambiguity has also been demonstrated to induce word class effects. Ambiguous words result in increased processing demands. EEG studies have, for example, shown that words that are ambiguous with respect to word class differ from unambiguous words in their processing (Federmeier et al. 2000; Vigliocco et al. 2011).

Summing up, nouns are typically acquired earlier than verbs in childhood (Bultena et al. 2014; Gentner 1981) and are less affected by neurological disorders – for example dementia (Macoir 2019). Numerous studies have found that verbs are processed more slowly (e.g., Cordier et al. 2013) and involve greater processing demands compared to nouns (e.g., Macoir et al. 2019).

3 Word class distribution in proverbs: Corpus results

Before the data from a reaction-time study is reported in Section 4 below, the distribution of the content word classes shall be examined in various (sub-)corpora to identify likely preferences for particular word classes. Firstly, the type and token frequencies of word classes in CAEP (Corpus of American English Proverbs; a specialized proverb corpus, see Lückert 2019b, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:6-14159451681, also Lückert 2018b) will be reported. Secondly, the proportions of the word classes from the proverb corpus will be compared to the ratio in the spoken component of COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English) to examine whether word class distribution in the proverb context is distinct from spoken language on a more general level. Lastly, the ratio in a historical proverb collection from the 16th century (John Heywood’s collection, see Aurich 2012) will be considered to test whether the same word class(es) was/were preferred or to identify likely differences that may be linked with linguistic change.

Word classes are associated with various syntactic roles in sentences. Generally, all sentence types occur in proverbs (Mac Coinnigh 2015: 113–115):

simple (e.g., Misery loves company)

complex (e.g., Be all that you can be)

compound (e.g., It never rains but it pours)

compound-complex (e.g., When the oak is before the ash, then you will only get a splash; when the ash is before the oak, then you may expect an oak)

nominal (e.g., The more – the merrier).

The content word categories – noun, verb, adjective, and adverb – perform various functions in these sentence types (cf. Baker 2010; Croft 2000; Haspelmath 2012). In view of sentence functions in proverbs, Mac Coinnigh observed that functions vary and that there seems to be “a clear preference for simple indicative statements over the majority of other forms in modern English-language proverbs” (2015: 130).

In the perception of language users, the four content word classes do not seem to have an equal impact on the overall meaning of phraseological units. Ďurčo (1994) used informant rating to examine how much individual constituents contribute to the overall phraseological meaning. In his study, nouns and verbs but also adjectives were regarded as key constituents. While the ratings for specific phraseological units differed across participants, there was usually a clear pattern. Phraseological comprehension processes may vary across individual language users (cf. Häcki Buhofer 2007: 845).

Nouns are the numerically strongest word class in the proverb corpus both by types and tokens. While the type frequencies of word classes in the subset of the most frequent and/or familiar proverbs from the proverb corpus (‘x3’, Lückert 2018b) relative to the whole proverb corpus do not differ significantly (Tab. 1), the token frequencies reveal significant differences (Tab. 2). By token frequencies, nouns and adverbs are significantly under-represented and verbs and adjectives are significantly over-represented in the ‘x3’ subset relative to the complete proverb corpus. This may imply a preference for verb and adjective constructions in current proverbs.

If we compare the ‘x3’ component of the proverb corpus (CAEP) to the spoken component of COCA, we find significant differences in the token frequencies of word classes (Tab. 3). Both nouns and verbs are under-represented in the proverb corpus. Adjectives and adverbs, however, are over-represented in CAEP. This may be due to proverb patterns/formulae in which adjectives (e.g., better in Better X than Y; see Mac Coinnigh 2015: 117) and adverbs (e.g., never in Never Verb [e.g., Never say never]; Mac Coinnigh 2015: 120; Mieder 2012: 147) are used as structural elements.

Type frequencies of word classes in proverb corpus (CAEP); comparison of ‘x3’ types (most frequent and/or familiar proverbs from CAEP; N = 247 proverbs) and types in complete proverb corpus (N = 4,164 proverbs); observed (OF) and expected (EF) frequencies were compared by log likelihood ratio test (LL) as goodness-of-fit test; odds ratio as effect size measure

OF X3 Types |

OF CAEP Types |

EF X3 Types |

EF CAEP Types |

LL |

LL+/– |

p value (Df 1) |

Odds Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

noun |

207 |

1543 |

228.35 |

1521.65 |

2.36 |

LL– |

p < 0.1 |

0.79 |

verb |

93 |

536 |

82.08 |

546.92 |

1.61 |

LL+ |

p < 0.1 |

1.2 |

adj |

73 |

490 |

73.46 |

489.54 |

0.003 |

LL– |

p < 0.1 |

0.99 |

adv |

55 |

283 |

44.10 |

293.90 |

2.90 |

LL+ |

p > 0.1 |

1.34 |

428 |

2852 |

Token frequencies of word classes in proverb corpus (CAEP); comparison of ‘x3’ tokens (most frequent and/or familiar proverbs from CAEP; N = 247 proverbs) and tokens in complete proverb corpus (N = 4,164 proverbs); observed (OF) and expected (EF) frequencies were compared by log likelihood ratio test (LL) as goodness-of-fit test; odds ratio as effect size measure

OF X3 Tokens |

OF CAEP Tokens |

EF X3 Tokens |

EF CAEP Tokens |

LL |

LL+/– |

p value (Df 1) |

Odds Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

noun |

2173 |

6037 |

2465.55 |

5744.45 |

50.83 |

LL– |

p < 0.001 |

0.77 |

verb |

2072 |

3823 |

1770.33 |

4124.67 |

71.33 |

LL+ |

p < 0.001 |

1.37 |

adj |

1549 |

3384 |

1481.43 |

3451.57 |

4.37 |

LL+ |

p < 0.05 |

1.09 |

adv |

1166 |

2972 |

1242.69 |

2895.31 |

6.85 |

LL– |

p < 0.01 |

0.9 |

6960 |

16216 |

Token frequencies of word classes in ‘x3’ component of proverb corpus (CAEP) relative to spoken component of COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English); comparison of ‘x3’ tokens (most frequent and/or familiar proverbs from CAEP; N = 247 proverbs) and tokens in spoken component of COCA; observed (OF) and expected (EF) frequencies were compared by log likelihood ratio test (LL) as goodness-of-fit test; odds ratio as effect size measure

OF X3 Tokens |

OF COCA Spoken Tokens |

EF X3 Tokens |

EF COCA Spoken Tokens |

LL |

LL+/− |

p value (Df 1) |

Odds Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

noun |

2173 |

19297498 |

2267.34 |

19297403.7 |

3.98 |

LL− |

p < 0.05 |

0.94 |

verb |

2072 |

24806129 |

2914.49 |

24805286.5 |

271.16 |

LL− |

p < 0.001 |

0.59 |

adj |

1549 |

6250438 |

734.49 |

6251252.5 |

682.78 |

LL+ |

p < 0.001 |

2.43 |

adv |

1166 |

8882663 |

1043.68 |

8882785.3 |

13.81 |

LL+ |

p < 0.001 |

1.14 |

6960 |

59236728 |

Interestingly, the ratios of content word classes in the ‘x3’ subset of CAEP do not differ significantly from the ratios in the 16th-century Heywood proverb collection (Tab. 4). Nouns seem to be less frequent in the modern proverb corpus relative to the historical collection. Verbs, however, seem to have become more important. The proportions of adjectives and adverbs have remained very stable. A historical corpus-based study of English proverbs (Aurich 2012) reported a trend to nominalization and increasing use of proverb patterns/ formulae in proverbs found in medieval and early modern sources. While the corpus comparison (Tab. 4) does not reveal significant differences in the distribution of word classes, results may point to a weak trend towards the use of more verbal structures in modern English proverbs.

This assumed trend towards increasing use of verbs in English-language proverbs may go hand in hand with the trend towards “simple indicative statements” (Mac Coinnigh 2015: 130). Traditional proverb formulae that were associated with nominal structures (e.g. Better X than Y or No X no Y) are no longer prevalent (Mac Coinnigh 2015: 118; Mieder 2012). Mac Coinnigh (2015: 119–120) quotes the typical modern formulae from Mieder (2012: 144–147):

| (6) | A(n) / noun / verb … |

| A diamond is forever. | |

| (7) | A(n) / adjective / noun / verb … |

| A wise head is better than a pretty face. | |

| (8) | The / noun / verb … |

| The world hates a quitter. | |

| (9) | You can’t (cannot) / verb … |

| You can’t unscramble eggs. | |

| (10) | Don’t (do not) / verb … |

| Don’t believe everything you think. | |

| (11) | Never / verb … |

| Never work with children or animals. |

Token frequencies of word classes in ‘x3’ component of proverb corpus (CAEP) relative to Heywood Corpus (16th c., cf. Aurich 2012); comparison of ‘x3’ tokens (most frequent and/or familiar proverbs from CAEP; N = 247 proverbs) and tokens in Heywood Corpus (N = 100 proverbs); observed (OF) and expected (EF) frequencies were compared by log likelihood ratio test (LL) as goodness-of-fit test; odds ratio as effect size measure

OF X3 Tokens |

OF Heywood Tokens |

EF X3 Tokens |

EF Heywood Tokens |

LL |

LL+/– |

p value (Df 1) |

Odds Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

noun |

2173 |

150 |

2194.07 |

128.93 |

3.47 |

LL– |

p < 0.1 |

0.78 |

verb |

2072 |

103 |

2054.28 |

120.72 |

2.89 |

LL+ |

p < 0.1 |

1.26 |

adj |

1549 |

89 |

1547.09 |

90.91 |

0.04 |

LL+ |

p > 0.1 |

1.03 |

adv |

1166 |

67 |

1164.57 |

68.43 |

0.03 |

LL+ |

p > 0.1 |

1.03 |

6960 |

409 |

These modern formulae rely heavily on verb structures (both copula constructions, e.g. in A diamond is forever, and full verbs, e.g. in The world hates a quitter). In sum, the corpus results point to the assumed preference for nouns in proverbs but also seem to indicate that verbs have increasingly become more important.

4 The role of word class in online processing of proverbs: Experimental data

Given the findings on noun and verb processing reviewed in Section 2, we may expect nouns to facilitate processing of proverbs. Results of a study will be reported that was run in the Boland Lab at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (USA) in February 2018 (the data including all stimuli are available at URN https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:6-14159451681; cf. Lückert 2019b). The data of 97 participants (mean age 19.65, sd .88) were analyzed. The experimental tasks included self-paced word-by-word reading, expected recognition, and free recall (see Tab. 5).[5] In Lückert and Boland (submitted), the focus was on frequency effects on word and proverb level in self-paced reading of proverbs.[6] By contrast, the role of word class in processing in all three tasks shall be reported in the present paper.

Study design

1 Preparation Phase |

demographic background, rating task (proverb familiarity/use/ attitudes), proverb identification task (N = 97 subjects) |

|

|---|---|---|

2 Self-Paced Reading |

2a proverb list (N = 60 stimuli) word-by-word reading, moving-window script |

2b word list (N = 18 stimuli) word-by-word reading |

3 Recognition |

3a proverb list (N = 100 stimuli, 50 target items, 50 fillers) |

3b word list (N = 36 stimuli, 18 target items, 18 fillers) |

4 Free Recall |

5–15 min written recall of all stimuli (words and proverbs, targets and fillers), non-recall counted as ‘0’ (N = 97 subjects) |

|

Note. All participants performed the proverb-list and word-list tasks. Block order was varied between subjects: Word-first group (N = 46 subjects); Proverb-first group (N = 51 subjects). Trials within each task were randomly ordered. A total of 75 existing proverbs and 35 novel proverb-like phrases were included.[7]

For data analysis, generalized linear mixed-effects models were fitted with the lmerTest package within the R environment for Statistical Computing (R Development Core Team, v. 3.5.1, 2018) for each dependent measure and experimental task with random intercepts for participants and items (and with random slopes by subject for Sentence Type [existing proverbs/novel phrases] unless this resulted in model over-specification). The binomial accuracy data were fitted with logit link function, the recall count data with Quasi-Poisson link function. The dependent measures included response times in milliseconds, accuracy rates, recall count, and recall position. For analysis, the focus was on the assumed word class effect and further variables that have been reported in previous research on word class effects (imageability, length, etc.). Frequency effects were largely excluded from analysis (these effects, in particular the keyword frequency effect, have been reported in Lückert and Boland [submitted]). Control variables that were not part of theoretically interesting interactions with word class were pruned by stepwise backwards elimination of insignificant factors.

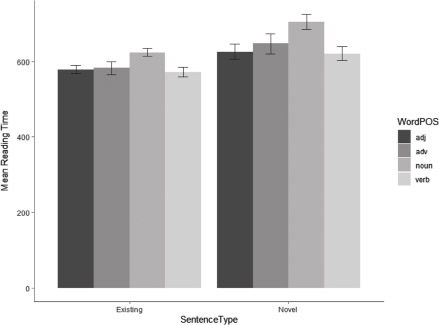

4.1 Word tasks

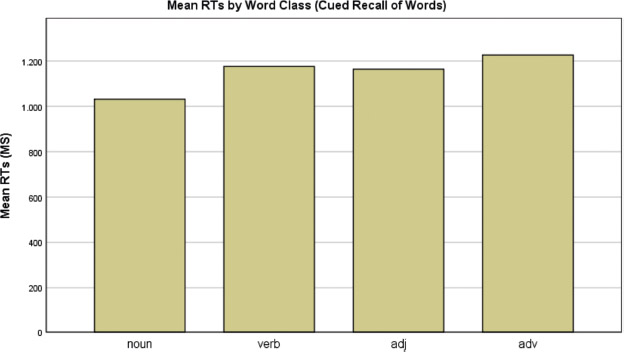

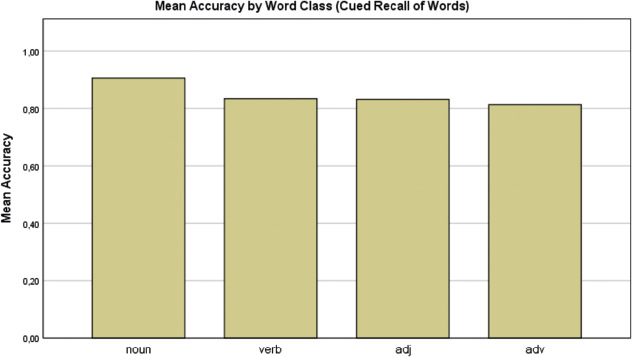

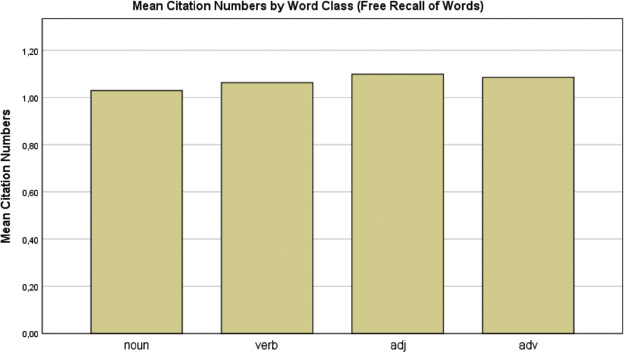

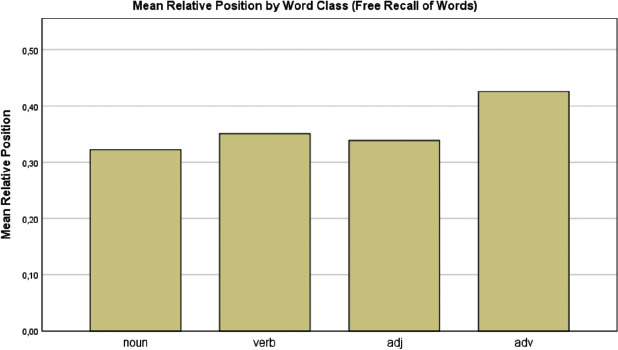

Individual proverb words were examined to compare the word class effect in single word processing to the effect in proverb processing. For the reading data of the word list, no mixed effects model was fitted because of the low number of stimuli in the task (N = 18). Results of the study/test list for proverb words, however, reveal an advantage for nouns relative to other content word classes in recognition and free recall: nouns were responded to significantly faster (t(31.09) −2.211, p = .035; Fig. 1) and tended to be recalled more accurately (z = 1.396, p = .163; Fig. 2) in recognition; nouns were also often named earlier (t(11.3) = −0.552, p = .591; Fig. 4) in free recall. Nouns were, however, cited less often (t = −2.769, p = .0058; Fig. 3) relative to other content word classes in free recall.

4.2 Self-paced reading of proverbs

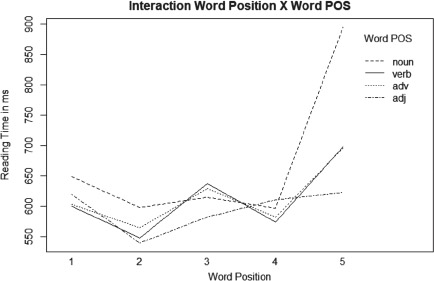

Word class significantly predicted response times in self-paced reading of proverbs. The mean reading-time latencies by word class for word positions 1 to 5 and for the conditions ‘existing proverbs’ and ‘novel proverb-like phrases’ (Sentence Type) in this task are summarized in Tab. 6. Word class is a categorical variable. For the mixed effects analysis, the results for individual word classes were therefore contrasted with adjectives (Tab. 7). In most word positions, nouns and adverbs were read more slowly, verbs were read as fast as adjectives (Figs. 5 and 6).[8]

Mean reaction-time latencies by word classes in cued recall of words (recognition). Both target words and fillers were included.

Mean accuracy by word classes in cued recall of words (recognition). Both target words and fillers were included.

Mean citation numbers (recall count) by word classes in free recall of words. Citation numbers are proportions of number of times a word was named. Non-recall was counted as ‘0’. The list of possible responses included target items and fillers. Higher values correlate with increased memorability.

Mean relative position (recall position) by word classes in free recall of words. Relative Position was measured on a scale where smaller values (closer to ‘0.00’) are associated with earlier positions and values closer to ‘1.00’ are associated with later positions. Lower values correlate with increased memorability.

Mean reading-time latencies by word class in word positions 1 to 5 for existing proverbs and novel proverb-like phrases in self-paced word-by-word reading

W1 |

W2 |

W3 |

W4 |

W5 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

exist. M (SD) |

novel M (SD) |

exist. M (SD) |

novel M (SD) |

exist. M (SD) |

novel M (SD) |

exist. M (SD) |

novel M (SD) |

exist. M (SD) |

novel M (SD) |

|

noun |

659 (43.8) |

632 (47.9) |

592 (55.0) |

615 (71.2) |

591 (102.6) |

660 (176.6) |

589 (96.3) |

620 (194.1) |

748 (155.5) |

1196 (85.4) |

verb |

596 (19.2) |

609 (33.2) |

537 (30.4) |

562 (16.6) |

579 (305.1) |

666 (152.9) |

578 (127.7) |

573 (16.8) |

534 (40.9) |

889 (501.9) |

adj |

606 (34.3) |

654 (114.6) |

538 (21.1) |

537 (21.4) |

613 (161.9) |

496 (13.4) |

583 (117.5) |

688 (229.5) |

531 (144.3) |

722 (326.4) |

adv |

595 (6.4) |

623 (331.3) |

549 (4.0) |

573 (21.1) |

643 (168.7) |

590 (290.3) |

530 (129.9) |

642 (174.4) |

464 (272.7) |

823 (353.0) |

To test the relationship of higher or lower ratios of nouns or verbs in proverbs with response times, two identical models were fitted – one with noun density as factor, one with verb density (the two density variables are not completely independent of each other). While the proportion of nouns in a given proverb (Noun Density) did not influence latencies (Tab. 7), a higher ratio of verbs resulted in faster responses (Verb Density t(58.3) = −1.876, p = .066).

Critical fixed effects from linear mixed model of word-by-word reading times in self-paced reading of proverbs (only word positions 1 to 5 were analyzed; Noun Density model)

Estimate |

Std.Error |

Df |

t value |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Adv |

−6.972e+01 |

2.249e+01 |

1.450e+04 |

−3.100 |

0.00194 ** |

Noun |

−1.580e+02 |

1.577e+01 |

1.637e+04 |

−10.016 |

< 2e-16 *** |

Verb |

−2.181e+01 |

1.954e+01 |

1.418e+04 |

−1.116 |

0.26437 |

Noun Density |

3.147e+00 |

3.823e+01 |

5.984e+01 |

0.082 |

0.93466 |

Word Position: Adv |

1.780e+01 |

6.361e+00 |

1.651e+04 |

2.799 |

0.00514 ** |

Word Position: Noun |

6.688e+01 |

4.692e+00 |

1.644e+04 |

14.253 |

< 2e-16 *** |

Word Position: Verb |

2.491e+01 |

5.947e+00 |

1.380e+04 |

4.189 |

2.82e-05 *** |

Sent. (novel): Adv |

−6.979e-02 |

2.214e+01 |

1.078e+04 |

−0.003 |

0.99748 |

Sent. (novel): Noun |

2.499e+01 |

1.356e+01 |

1.639e+04 |

1.843 |

0.06530 |

Sent. (novel): Verb |

−4.071e+01 |

1.671e+01 |

1.442e+04 |

−2.436 |

0.01486 * |

Note. Control variables came out as expected.[9]

p = 0 ‘***’ p < 0.001 ‘**’ p < 0.01 ‘*’ p < 0.05 ‘.’ p < 0.1 ‘ ’

Nouns led to long response latencies (Tab. 7, Figs. 5 and 6). This effect is not necessarily tied to an increased processing cost for nouns in the proverb context, it may rather be explained by task type: in an expected memory task, participants have intuitions about which constituent words would make memorizing easier. In the learning phase (reading task), nouns attracted more attention than other word classes – as a strategy, participants may have chosen to dwell longer on nouns to commit the whole proverb to memory.

While adverbs had the same effect in existing proverbs and novel proverb-like phrases (interaction with Sentence Type was not significant; Tab. 7), nouns and verbs were strongly affected by item type (Tab. 7). Nouns and verbs index specific proverbs more strongly than other content word classes. Language users tend to consider nouns (and verbs) key constituents of proverbs (e.g., Ďurčo 1994). In novel phrases, nouns and verbs successively activate and cancel existing proverb representations in the mental lexicon (cf. superlemmas, Lückert 2018a, Lückert 2019a, Lückert and Boland submitted). This is linked with a high processing cost. Word position modulated the effect of all word classes on reading times.

Mean reading-time latencies by word class across word positions 1 to 5 in self-paced reading of proverbs

Mean reading-time latencies by word class and Sentence Type in self-paced reading of proverbs

4.3 Recognition of proverbs

Word class did not robustly predict the dependent measures in this recall paradigm. A higher proportion of nouns in a proverb tended to result in slightly shorter reaction times (t(322.4) = −0.829, p = 0.41) and in slightly lower accuracy (z = −0.360, p = 0.72).[10] In the same mixed model, this time with the factor verb density only, a higher number of verbs in a proverb resulted in slightly shorter reaction times (t(527.2) = −1.259, p = 0.21) and in higher accuracy (z = 1.285, p = 0.199). A possible reason may lie in the differential representation of nouns and verbs in the mental lexicon. Nouns – because of their hierarchical structure – may compete more with other nouns in this forced-choice paradigm, while verbs may be less affected by competition.

4.4 Free recall of proverbs

In this recall paradigm, word class tended to influence position data but not count data. A higher number of nouns in a proverb resulted in slightly higher recall counts (t = 0.963, p = 0.335853) and in later positions (t(41.6) = 1.929, p = 0.061).[11] In the same mixed model, this time with the factor verb density only, a higher number of verbs in a proverb resulted in slightly lower counts (t = −1.238, p = 0.216) and in earlier positions (t(39.3) = −1.884, p = 0.067).

4.5 Discussion of experimental results

Word class was revealed to predict several dependent measures in the experimental tasks. This implies that word-level properties are active during processing of proverbs. In Lückert and Boland (submitted), we showed that frequency in the proverb context and in general language use – on the level of constituent words and proverbs – is an important determinant in proverb processing. The present study indicates that there are further word-level properties beyond the frequency dimension that become active in online processing of proverbs: the syntactic word categories of constituent words predicted performance of participants in reading and recall tasks.

In the reading task (learning phase of expected recall tasks), nouns were read more slowly than adjectives, adverbs were read a little slower than adjectives, and verbs were read about as fast adjectives. This effect probably reflects a conscious learning strategy of participants who felt that nouns would be key to memorizing the proverbs (cf. research by Ďurčo [1994]). The effect of nouns on reading-time latencies strongly depended on word position in the proverb and on item type (existing proverb or novel phrase; see Tab. 7).

The effect of nouns and verbs respectively is distinct in single word processing compared to proverb processing. This is consistent with findings from previous research on word class effects in sentential contexts (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014; Sass et al. 2010). In recognition of proverbs (contextual task), nouns led to shorter response times (insign.) and lower accuracy (insign.). In recognition of words (single word processing task), nouns resulted in shorter response times (sign.) and higher accuracy (insign.). Interestingly, the effect of nouns in free recall of words (single word processing task) was completely contrary to the effect in free recall of proverbs (contextual task). While, in single word processing, nouns led to lower recall counts (sign.) and earlier positions (insign.), in processing in the proverb context, nouns resulted in higher recall counts (insign.) and later positions (approached sign.).

Surprisingly, verbs seemed more beneficial to proverb processing than nouns in most tasks. In the reading task, a higher ratio of verbs led to faster reading times (approached sign.). In recognition, verbs resulted in shorter response times (insign.) and in higher accuracy (insign.). In free recall, verbs were associated with lower recall counts (insign.) and with earlier positions (approached sign.). Going by the token frequencies in the ‘x3’ set of the most frequent and/or familiar proverbs in CAEP, verbs are almost as frequent as nouns (Tab. 2) in current English-language proverbs in the American context. The type frequency of verbs is, however, much lower compared to noun type frequency – this means that a comparatively small set of verb types is used over and over again in the proverb context. This re-use of verbs may contribute to their association with the proverb context. The low recall counts linked with verbs in proverbs in free recall can probably be explained by the overall low number of verb types in proverbs together with the non-hierarchical representation of verbs in the mental lexicon (Macoir et al. 2019). This non-hierarchical representation makes co-activation of related words harder.

Within-sentence priming between words has been reported in previous research (e.g., Carrol and Conklin 2019). Stronger association between component words led to faster responses in a reading task (Carrol and Conklin 2019: 20). By contrast, Sass and colleagues reported that associations facilitated naming of nouns in single word production, whereas, in sentence production, associations resulted in interference (2010: 447). A similar inhibitory task type effect may be observed in the present study: in single-word processing tasks, nouns tended to facilitate processing. In sentential contexts, the co-activation patterns associated with nouns were found to inhibit processing of proverbs. Verbs, however, seemed to benefit from their integration in proverbs – the increased processing demands for verbs in (freely formed) sentences seem to diminish in proverb sentences (entrenched sentences).

5 Conclusion

In the present study, the effect of word classes on proverb processing was examined. Previous psycholinguistic research has shown that the word classes nouns and verbs, for example, differ in their effects in language processing. Verbs are, for example, often considered more complex than nouns (e.g., Bultena et al. 2014) and have been shown to be processed more slowly than nouns (e.g. Cordier et al. 2013). Based on these findings (Section 2), nouns (rather than verbs) were assumed to facilitate proverb processing.

The distributional analysis of word classes in various corpora presented in Section 3 was meant to highlight likely preferences for specific word classes in proverbs. It may be assumed that word classes that facilitate proverb processing have better chances of becoming part of lexicalized, entrenched structures. While nouns are the numerically strongest class in all proverb (sub-)corpora considered, there may be a (current) trend towards an increasing importance of verbs in English-language proverbs in the American context.

In Section 4, results of an experimental study were discussed that was originally designed to examine frequency effects on the level of constituent words and the level of proverbs (Lückert and Boland submitted). The word and proverb stimuli in the experiment run at the University of Michigan had been manipulated such that different word classes were all represented rather evenly. The data set was thus suited for an analysis of word class effects.

The analysis of the experimental study showed many null effects for word class. Despite the low number of significant effects for word class, interesting trends could be identified in the data. Contrary to expectation, verbs rather than nouns seemed to facilitate proverb processing in various experimental tasks. This trend in the experimental data cannot, however, explain by itself why there seems to be a trend towards more verbs in modern English-language proverbs in the American context. It remains to be seen whether the effects tied to the word class of constituent words of proverbs of the present study can be reproduced with a more varied population sample (including older people)[12] and in contextual testing paradigms that make it possible to avoid learning strategies (cf. discussion in Section 4.2).[13]

The processing benefit associated with verbs in proverbs appears to be rather weak. It thus stands to reason to assume that the increased importance of verbs in American English proverbs can be explained by changed cultural norms and discourse practices. It has, for example, been noted that “straight-forward indicative formulae, which appear to be void of many of the traditional proverbial markers, especially syntactic and phonological devices” are favored today (Mac Coinnigh 2015: 119) and that “the obvious didactic nature of many traditional proverbs appears to be on the decline” (Mieder 2012: 147). The typical modern formulae in the form of simple indicative statements rely heavily on verb structures (Section 3).

Given the surprising results for verbs in proverb processing, it would seem desirable to investigate the processing of verbs in multiple types of sentence contexts including proverbs and other reproducible multiword contexts and non-entrenched sentence contexts.[14] Lexical retrieval of verbs has been shown to involve exhaustive activation of all its complementation options (Shetreet et al. 2016). This may be different in entrenched sentence contexts such as proverbs.

6 References

Alario, F.-Xavier, Albert Costa & Alfonso Caramazza. 2002. Frequency effects in noun phrase production: Implications for models of lexical access. Language and Cognitive Processes 17(3). 299–319.10.1080/01690960143000236Suche in Google Scholar

Arnaud, Pierre J. L. & Rosamund Moon. 1993. Fréquence et emplois des proverbes anglais et français [Frequency and usage of English and French proverbs]. In Christian Plantin (ed.), Lieux Communs, Topoï, Stéréotypes, Clichés [Commonplaces, topoi, stereotypes, clichés], 323–341. Paris: Kimé.Suche in Google Scholar

Aurich, Claudia. 2012. Proverb Structure in the History of English: Stability and Change. A Corpus-Based Study (Phraseologie und Parömiologie 26). Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, Mark C. 2010. Lexical Categories. Verbs, Nouns, and Adjectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bultena, Sybrine, Ton Dijkstra & Janet G. van Hell. 2014. Cognate effects in sentence context depend on word class, L2 proficiency, and task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 67(6). 1214–1241.10.1080/17470218.2013.853090Suche in Google Scholar

Bürki, Audrey, Jasmin Sadat, Anne-Sophie Dubarry & F.-Xavier Alario. 2016. Sequential processing during noun phrase production. Cognition 146. 90–99.10.1016/j.cognition.2015.09.002Suche in Google Scholar

Carrol, Gareth & Kathy Conklin. 2019. Is all formulaic language created equal? Unpacking the processing advantage for different types of formulaic sequences. Language and Speech (OnlineFirst). 1–28.10.1177/0023830918823230Suche in Google Scholar

Čermák, František. 2006. Statistical methods for searching idioms in text corpora. In Annelies Häcki Buhofer & Harald Burger (eds.), Phraseology in Motion I. Methoden und Kritik [Phraseology in motion I. Methods and criticism] (Phraseologie und Parömiologie 19), 33–42. Baltmannsweiler: Hohengehren.Suche in Google Scholar

Chlosta, Christoph & Peter Grzybek. 2005. Varianten und Variationen anglo-amerikanischer Sprichwörter – Dokumentation einer empirischen Untersuchung [Variants and variations of American English proverbs – Documentation of an empirical study]. ELiSe: Essener Linguistische Skripte elektronisch 5(2). 63–145.Suche in Google Scholar

Cordier, Françoise, Jean-Claude Croizet & François Rigalleau. 2013. Comparing nouns and verbs in a lexical task. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 42(1). 21–35.10.1007/s10936-012-9202-xSuche in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2000. Parts of speech as language universals and as language-particular categories. In Petra M. Vogel & Bernard Comrie (eds.), Approaches to the Typology of Word Classes, 65–102. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110806120.65Suche in Google Scholar

Ďurčo, Peter. 1994. Probleme der allgemeinen und kontrastiven Phraseologie [Issues of general and contrastive phraseology]. Heidelberg.Suche in Google Scholar

Ďurčo, Peter. 2005. Sprichwörter in der Gegenwartssprache [Proverbs in modern language use]. Trnava: Univerzita Sv. Cyrila a Metoda. Filozofická fakulta.Suche in Google Scholar

Duthie, Jill K., Marilyn A. Nippold, Jesse L. Billow & Tracy C. Mansfield. 2008. Mental imagery of concrete proverbs: A developmental study of children, adolescents, and adults. Applied Psycholinguistics 29. 151–173.10.1017/S0142716408080077Suche in Google Scholar

Federmeier, Kara D., Jessica B. Segal, Tania Lombrozo & Marta Kutas. 2000. Brain responses to nouns, verbs and class ambiguous words in context. Brain 123. 2552–2566.10.1093/brain/123.12.2552Suche in Google Scholar

Ferretti, Todd R., Christopher A. Schwint & Albert N. Katz. 2007. Electrophysiological and behavioral measures of the influence of literal and figurative contextual constraints on proverb comprehension. Brain and Language 101. 38–49.10.1016/j.bandl.2006.07.002Suche in Google Scholar

Gentner, Dedre. 1981. Some interesting differences between verbs and nouns. Cognition and Brain Theory 4. 161–178.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W. & Dinara Beitel. 1995. What proverb understanding reveals about how people think. Psychological Bulletin 118(1). 133–154.10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.133Suche in Google Scholar

Grzybek, Peter. 2012. Facetten des parömiologischen Rubik-Würfels. Kenntnis = Bekanntheit? [Facets of the paremiological Rubik’s Cube. Knowledge = familiarity?]. In Kathrin Steyer (ed.), Sprichwörter multilingual. Theoretische, empirische und angewandte Aspekte der modernen Parömiologie [Proverbs from a multilingual angle. Theoretical, empirical and applied aspects of modern paremiology], 99–138. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

Häcki Buhofer, Annelies. 2007. Psycholinguistic aspects of phraseology: European tradition. In Harald Burger, Dmitrij Dobrovol’skij, Peter Kühn & Neal R. Norrick (eds.), Phraseologie. Phraseology. Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung. An International Handbook of Contemporary Research, Vol. 2, 836–853. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110190762.836Suche in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 2012. How to compare major word-classes across the world’s languages. In Thomas Graf, Denis Paperno, Anna Szabolcsi & Jos Tellings (eds.), Theories of Everything: In Honor of Ed Keenan, 109–130. Los Angeles: University of California.Suche in Google Scholar

Honeck, Richard P. 1997. A Proverb in Mind. The Cognitive Science of Proverb Wit and Wisdom. Mahwah, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.Suche in Google Scholar

Horvath, Julia & Tal Siloni. 2009. Hebrew idioms: The organisation of the lexical component. Brill’s Annual of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 1. 283–310.10.1163/187666309X12491131130666Suche in Google Scholar

Lückert, Claudia. 2018a. A psycholinguistic approach to the conventionalisation and variation of proverb structure. In Natalia Filatkina & Sören Stumpf (eds.), Konventionalisierung und Variation: Phraseologische und konstruktionsgrammatische Perspektiven [Conventionalisation and variation: Perspectives from phraseology and construction grammar], 53–71. Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Lückert, Claudia. 2018b. The lexical profile of modern American proverbs: Detecting contextually predictable keywords in a database of American English proverbs. Yearbook of Phraseology 9. 31–50.10.1515/phras-2018-0004Suche in Google Scholar

Lückert, Claudia. 2019a. The proverbial discourse tradition in the history of English: A usage-based view. In Birte Bös & Claudia Claridge (eds.), Norms and conventions in the history of English, 129–148. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.347.07lucSuche in Google Scholar

Lückert, Claudia. 2019b. Proverb Database: Corpus of American English Proverbs (CAEP) and Experimental Study. URN https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:6-14159451681; doi 10.17879/1415945138710.17879/14159451387Suche in Google Scholar

Lückert, Claudia & Julie E. Boland. submitted. Keyword frequency effect facilitates processing of sentence-like multiword expressions. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Mac Coinnigh, Marcas. 2015. Structural aspects of proverbs. In Hrisztalina Hrisztova-Gotthardt & Melita Aleksa Varga (eds.), Introduction to Paremiology. A Comprehensive Guide to Proverb Studies, 112–132. Warsaw: De Gruyter Open.Suche in Google Scholar

Macoir, Joël, Anne Lafay & Carol Hudon. 2019. Reduced lexical access to verbs in individuals with Subjective Cognitive Decline. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias 34(1). 5–15.10.1177/1533317518790541Suche in Google Scholar

Meyer, Antje S. 1996. Lexical access in phrase and sentence production: Results from picture–word interference experiments. Journal of Memory and Language 35(4). 477–496.10.1006/jmla.1996.0026Suche in Google Scholar

Mieder, Wolfgang. 2007. Proverbs as cultural units or items of folklore. In Harald Burger, Dmitrij Dobrovol’skij, Peter Kühn & Neal R. Norrick (eds.), Phraseologie. Phraseology. Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung. An International Handbook of Contemporary Research, Vol. 1, 394–414. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110171013.394Suche in Google Scholar

Mieder, Wolfgang. 2012. “Think outside the box”: Origin, Nature, and Meaning of Modern Anglo-American Proverbs. Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholar-ship 29. 137–196.Suche in Google Scholar

Moon, Rosamund. 1998. Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English. A Corpus-Based Approach. Oxford: Clarendon.10.1093/oso/9780198236146.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Morgan, Emily & Roger Levy. 2016. Abstract knowledge versus direct experience in processing of binomial expressions. Cognition 157. 384–402.10.1016/j.cognition.2016.09.011Suche in Google Scholar

Pulvermüller, Friedemann, Werner Lutzenberger & Hubert Preissl. 1999. Nouns and verbs in the intact brain: Evidence from event-related potentials and high-frequency cortical responses. Cerebral Cortex 9(5). 497–506.10.1093/cercor/9.5.497Suche in Google Scholar

Sass, Katharina, Stefan Heim, Olga Sachs, Katharina Theede, Juliane Muehlhaus, Sören Krach & Tilo Kircher. 2010. Why the leash constrains the dog: The impact of semantic associations on sentence production. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis 70. 435–453.10.55782/ane-2010-1815Suche in Google Scholar

Schriefers, Herbert. 1992. Lexical access in the production of noun phrases. Cognition 45(1). 33–54.10.1016/0010-0277(92)90022-ASuche in Google Scholar

Shetreet, Einat, Tal Linzen & Naama Friedmann. 2016. Against all odds: Exhaustive activation in lexical access of verb complementation options. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 31(9). 1206–1214.10.1080/23273798.2016.1205203Suche in Google Scholar

Sidhu, David M., Alison Heard & Penny M. Pexman. 2016. Is more always better for verbs? Semantic richness effects and verb meaning. Frontiers in Psychology 7. 1–14.10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00798Suche in Google Scholar

Siyanova-Chanturia, Anna, Kathy Conklin & Walter van Heuven. 2011. Seeing a phrase “time and again” matters: The role of phrasal frequency in the processing of multiword sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 37(3). 776–784.10.1037/a0022531Suche in Google Scholar

Sprenger, Simone A., Willem J. M. Levelt & Gerard Kempen. 2006. Lexical access during the production of idiomatic phrases. Journal of Memory and Language 54. 161–184.10.1016/j.jml.2005.11.001Suche in Google Scholar

Steyer, Kathrin. 2015. Proverbs from a corpus-linguistic point of view. In Hrisztalina Hrisztova-Gotthardt & Melita Aleksa Varga (eds.), Introduction to Paremiology. A Comprehensive Guide to Proverb Studies, 206–228. Warsaw: De Gruyter Open.Suche in Google Scholar

Steyer, Kathrin. 2017. Corpus linguistic exploration of modern proverb use and proverb patterns. In Ruslan Mitkov (ed.), EUROPHRAS 2017. Computational and corpus-based phraseology: Recent advances and interdisciplinary approaches. Proceedings of the Conference Volume II. November 13–14, 2017, London, UK, 45–52. Geneva: Editions Tradulex.10.26615/978-2-9701095-2-5_006Suche in Google Scholar

Szekely, Anna, Simonetta D’Amico, Antonella Devescovi, Kara Federmeier, Dan Herron, Gowri Iyer, Thomas Jacobsen, Analía L. Arévalo, Andras Vargha & Elizabeth Bates. 2005. Timed action and object naming. Cortex 41(1). 7–25.10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70174-6Suche in Google Scholar

Vigliocco, Gabriella, David P. Vinson, Judit Druks, Horacio Barber & Stefano F. Cappa. 2011. Nouns and verbs in the brain: A review of behavioural, electrophysiological, neuropsychological and imaging studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 35(3). 407–426.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- Furiously fast: On the speed of change in formulaic language

- Phraseme zu Haus und Hof in der deutschen Sprachgeschichte

- Phrasem-Konstruktionen kontrastiv Deutsch–Spanisch: ein korpusbasiertes Beschreibungsmodell anhand ironischer Vergleiche

- A comparative study of idioms on drunkenness in Chinese and Spanish

- Scheinäquivalente/Potenzielle falsche Freunde im phraseologischen Bereich (am Beispiel des Sprachenpaares Deutsch–Spanisch)

- Zur Äquivalenz der minimalen lexikalisch geprägten Muster „Präposition + Substantiv“ im deutsch-slowakischen Kontrast

- Word class effect in online processing of proverbs: A reaction-time study

- Obituaries

- Obituaries

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- Furiously fast: On the speed of change in formulaic language

- Phraseme zu Haus und Hof in der deutschen Sprachgeschichte

- Phrasem-Konstruktionen kontrastiv Deutsch–Spanisch: ein korpusbasiertes Beschreibungsmodell anhand ironischer Vergleiche

- A comparative study of idioms on drunkenness in Chinese and Spanish

- Scheinäquivalente/Potenzielle falsche Freunde im phraseologischen Bereich (am Beispiel des Sprachenpaares Deutsch–Spanisch)

- Zur Äquivalenz der minimalen lexikalisch geprägten Muster „Präposition + Substantiv“ im deutsch-slowakischen Kontrast

- Word class effect in online processing of proverbs: A reaction-time study

- Obituaries

- Obituaries

- Book reviews

- Book reviews