Abstract

This study examined the acoustic profiles of five basic emotions in American English and Mandarin Chinese using a big data approach. A total of 6,373 features were extracted using the openSMILE toolkit, and key discriminative features were identified through random forest classification. In American English, vocal emotions were primarily conveyed through pitch-related features, while Mandarin Chinese, shaped by its tonal constraints, relied more on spectral and voice quality cues, including MFCCs, HNR, and shimmer. Linear mixed-effects models confirmed significant effects of emotion on the top-ranked features, and Cohen’s d further supported distinct acoustic profiles for each emotion. K-means clustering revealed both categorical groupings and dimensional overlaps, such as the clustering of high-arousal emotions like happy and surprised, and low-arousal emotions like sad and neutral. These results suggest that vocal emotion expression is shaped by language-specific prosodic systems, as well as by both discrete emotion categories and continuous affective dimensions, supporting an integrated model of emotional prosody.

-

Research ethics: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida (Protocol code: IRB202202321; Date of Approval: October 25, 2022). All participants reviewed the informed consent form online and provided their agreement to participate in the study.

-

Author contributions: The author conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, reviewed the literature, collected and analyzed data, created visualizations, drafted and revised the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The data presented in this study are available upon request.

48 Semantically-neutral Sentences in American English.

That I owe my thanks to you.

That was his chief thought.

The football teams give a tea party.

She is now choosing skirt to wear.

This used to be Jerry’s occupation.

I chose the right way.

The octopus has eight legs.

I do not eat bread.

She was born on April nineteen forty three.

I don’t paint tiger.

I guess it’s a choice feast.

Tom and Michael woke up the next morning.

They were children of mine.

I am from towel land.

A large flat ferry boat was moored beside it.

I blinked my eyes hard.

We all see pandas on TV or in the zoo.

The eye could not catch them.

That’s a full grown colt.

I lent George three pounds.

They ate beef at the butcher shop.

Sam waved his arm vaguely.

I shall say goodbye.

He searched through the box.

I pay half a crown a week extra.

But the tune isn’t his own invention.

Your own wife is not at home.

He told me that I ought to change.

Both sides were softly curved.

I must have two to fetch and carry.

The song is called Ways and Means.

After a while he perceived both giants.

We may join with that power.

They had been named Tom and Jerry.

She has a high voice.

I know how to obey orders.

How Tom and Jerry went to visit Mister Sam.

She came back to the valley.

The fisherman and his wife see George every day.

I owe them five hundred dollars.

I am back safe again.

Father has yellow eyes.

Bob goes to a new school.

The name of the song is called haddocks.

She has no place for hot pepper.

They are made of wood.

It’s part of my secret.

I am going back-to-back home.

48 Semantically-neutral Sentences in Mandarin Chinese

我每个月打一次电话。

已经播至该专辑最后一个声音。

我和我朋友刚从巴厘岛回来。

工厂不把它直接排到大气中。

我必须一直通电才能工作。

我们可以轮流开车。

这是台湾地区最大的动物园。

递给我一些彩球和纸花。

我是基于人工智能系统被创造的。

它实际会形成一氧化碳。

我参加了一个有关全球变暖的集会,

坐地铁只需要大约二十分钟。

今年应该是第二十七个教师节。

听说你要去香港看你叔叔。

如果有我能帮忙的请告诉我。

你女儿和她妈妈长得很像。

我只会斗斗地主什么的。

就经常去我们宿舍附近的酒吧。

没有找到蒸鱼的计时。

让我们看看哪一种球技比较好。

自己的事情要自己做。

我要学习一下相关知识。

我只打算放松一下自己。

我的性格就是冷静并且客观。

我想那些应该是草莓的种子。

这样你就有时间挥拍打球了。

他在这次竞选活动中花了数百万,

二零一六年十一月五号是星期六。

上海现在是下午四点三十六分。

我已经习惯这种气候了。

你可以在那儿呆上至少一整天。

我最近正在努力练习棋艺。

它是一个主要的空气污染物。

大约一个小时左右。

我不怎么在乎这个店有没有名。

这是我在旅游第四天拍的。

没有找到你想删除的闹钟。

然后再找一个音乐播放器,

我希望你能和我一起想派对点子。

我刚从苏格兰回来。

我在一个机械化农场做工程师。

我去查查篮球相关的知识。

我们休息一下喝杯咖啡。

旅行结束后我将休息一段时间。

家里有全自动洗衣机。

于是我就问她能不能连我的票买了。

他们将于今年夏天结婚。

这两块是唐朝不同时期铸造的。

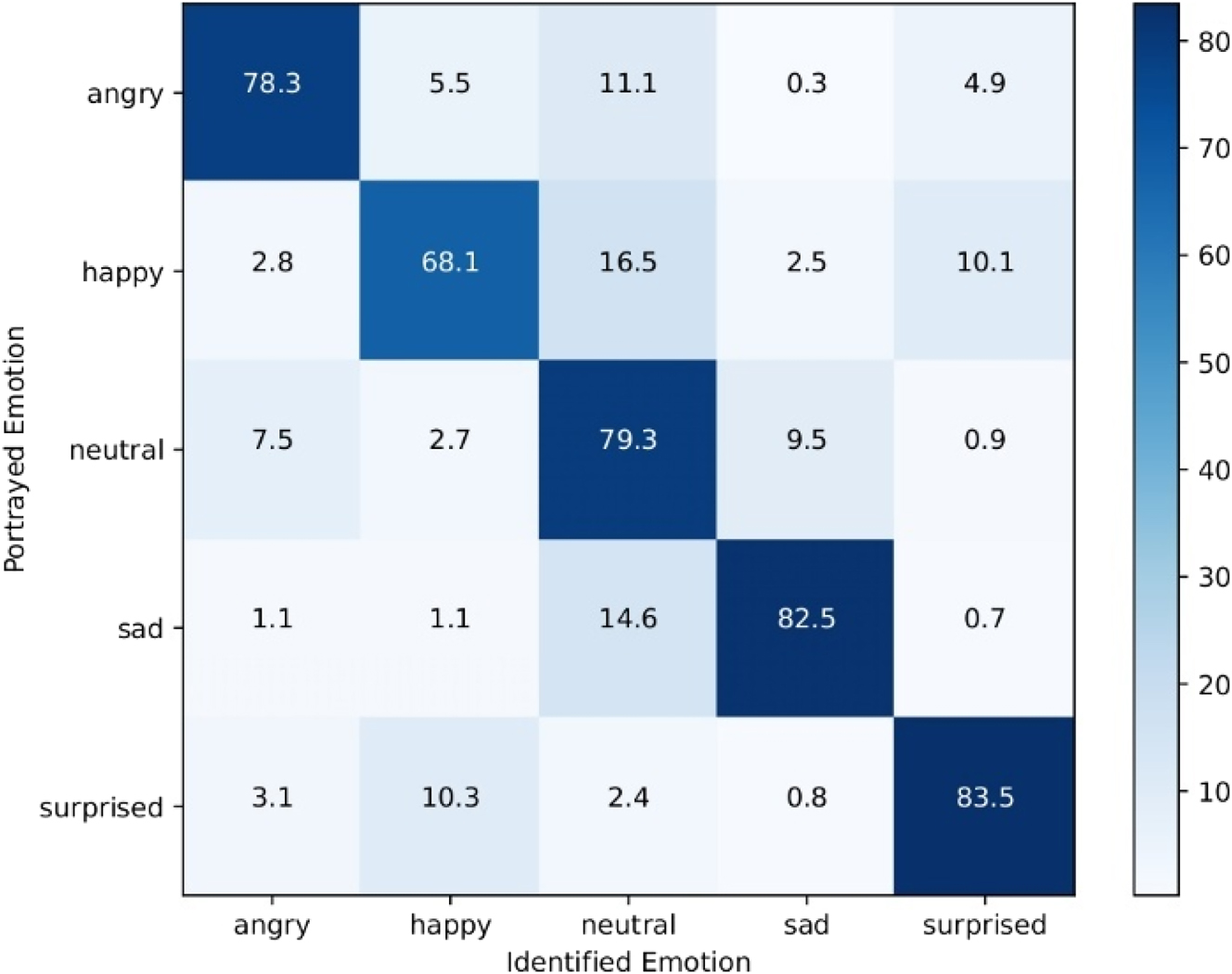

As shown in Figure 1, English raters demonstrated relatively high correct identification rates for neutral, angry, sad, and surprised emotions, all close to or above 80 %. In contrast, happy was the most challenging emotion to identify, with a correct identification rate of 68.1 %. Among the misidentifications, angry was frequently mistaken for neutral (11.1 %), while happy was often confused with neutral (16.5 %) or surprised (10.1 %). Sad was occasionally misidentified as neutral (14.6 %), and surprised was sometimes confused with happy (10.3 %). Neutral showed a consistent pattern, with the highest misidentification rate as sad (9.5 %). These patterns suggest that English raters tend to misidentify non-neutral emotions as neutral and struggle particularly with distinguishing happy from other emotions.

Confusion matrix in percentage for the 30 selected sentences in American English by native English raters.

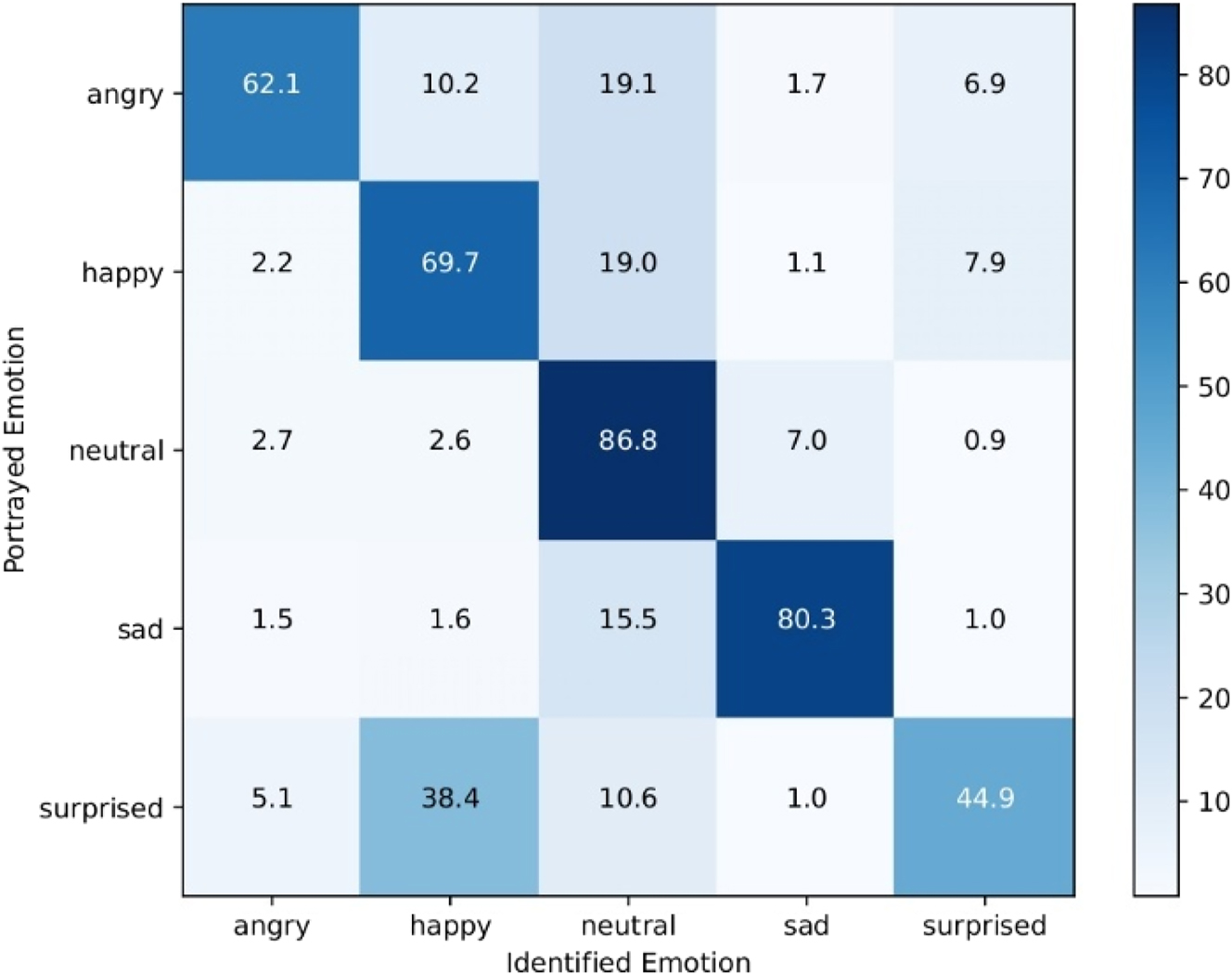

Figure 2 presents the confusion matrix for native Mandarin Chinese raters identifying the same set of emotions. Correct identification rates for angry, happy, and surprised were noticeably lower compared to English raters, with angry at 62.1 %, happy at 69.7 %, and surprised at 44.9 %. Neutral had a high correct identification rate of 86.8 %, surpassing that of English raters. Misidentifications included angry often being confused with neutral (19.1 %) and happy (10.2 %), while happy was frequently misidentified as neutral (19.0 %) or surprised (7.9 %). Sad showed a relatively high correct identification rate of 80.3 %, but neutral was occasionally mistaken for sad (7.0 %). Surprised had the lowest correct identification rate among all emotions and was frequently confused with happy (38.4 %).

Confusion matrix in percentage for the 30 selected sentences in Mandarin Chinese by native Chinese raters.

References

Anolli, L., L. Wang, F. Mantovani & A. De Toni. 2008. The voice of emotion in Chinese and Italian young adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 39(5). 565–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108321178.Suche in Google Scholar

Bachorowski, J.-A. & M. J. Owren. 1995. Vocal expression of emotion: Acoustic properties of speech are associated with emotional intensity and context. Psychological Science 6(4). 219–224.10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00596.xSuche in Google Scholar

Banse, R. & K. R. Scherer. 1996. Acoustic profiles in vocal emotion expression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70(3). 614–636.10.1037//0022-3514.70.3.614Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-David, B. M., N. Multani, V. Shakuf, F. Rudzicz & P. H. van Lieshout. 2016. Prosody and semantics are separate but not separable channels in the perception of emotional speech: Test for rating of emotions in speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 59(1). 72–89.10.1044/2015_JSLHR-H-14-0323Suche in Google Scholar

Bitouk, D., R. Verma & A. Nenkova. 2010. Class-level spectral features for emotion recognition. Speech Communication 52(7). 613–625.10.1016/j.specom.2010.02.010Suche in Google Scholar

Boersma, P. 2023. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [computer program]. http://www.praat.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Borchert, M. & A. Dusterhoft. 2005. Emotions in speech: Experiments with prosody and quality features in speech for use in categorical and dimensional emotion recognition environments. In Proceedings of the 2005 international conference on natural language processing and knowledge engineering, 147–151. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/NLPKE.2005.1598724.Suche in Google Scholar

Breiman, L. 2001. Random forests. Machine Learning 45(1). 5–32.10.1023/A:1010933404324Suche in Google Scholar

Chang, H. S., C. Y. Lee, X. Wang, S. T. Young, C. H. Li & W. C. Chu. 2023. Emotional tones of voice affect the acoustics and perception of Mandarin tones. PLoS One 18(4). e0283635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283635.Suche in Google Scholar

Chao, Y. R. 1933. Tone and intonation in Chinese. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology 4. 121–134.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Abingdon, England: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Duanmu, S. 2007. The phonology of standard Chinese. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199215782.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Eerola, T. & J. K. Vuoskoski. 2011. A comparison of the discrete and dimensional models of emotion in music. Psychology of Music 39(1). 18–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735610362821.Suche in Google Scholar

Ekman, P. 2003. Emotions inside out. 130 years after Darwin’s “the expression of the emotions in man and animal”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1000. 1–6.10.1196/annals.1280.010Suche in Google Scholar

Eyben, F., M. Wöllmer & B. Schuller. 2009. OpenEAR — Introducing the Munich open-source emotion and affect recognition toolkit. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd international conference on affective computing and intelligent interaction and workshops, 1–6. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACII.2009.5349350.Suche in Google Scholar

FindingFive Team. 2023. FindingFive: An online platform for creating, running, and managing your experiments. https://www.findingfive.com.Suche in Google Scholar

Gendron, M. & Lisa Feldman Barrett. 2009. Reconstructing the past: A century of ideas about emotion in psychology. Emotion Review 1(4). 316–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073909338877.Suche in Google Scholar

Gobl, C. & A. Ní Chasaide. 2003. The role of voice quality in communicating emotion, mood and attitude. Speech Communication 40(1). 189–212.10.1016/S0167-6393(02)00082-1Suche in Google Scholar

Guyon, I. & A. Elisseeff. 2003. An introduction to variable and feature selection. Journal of Machine Learning Research 3(Mar). 1157–1182.Suche in Google Scholar

Ho, T. K. 1995. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on document analysis and recognition, vol. 1, pp. 278–282. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.1995.598994.Suche in Google Scholar

Jack, R. E., O. G. B. Garrod & P. G. Schyns. 2014. Dynamic facial expressions of emotion transmit an evolving hierarchy of signals over time. Current Biology 24(2). 187–192.10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.064Suche in Google Scholar

Jackson, P. & S. Haq. 2014. Surrey audio-visual expressed emotion (savee) database. Guildford, UK: University of Surrey.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnstone, T. & K. R. Scherer. 2000. Vocal communication of emotion. Handbook of Emotions 2. 220–235.Suche in Google Scholar

Juslin, P. N. & P. Laukka. 2003. Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychological Bulletin 129(5). 770–814.10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.770Suche in Google Scholar

Juslin, P. N. & K. R. Scherer. 2005. Vocal expression of affect. The new handbook of methods in nonverbal behavior research, 65–135. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198529613.003.0003Suche in Google Scholar

Kassambara, A. & F. Mundt. 2020. Factoextra: Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses [R package version 1.0.7]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra.Suche in Google Scholar

Ketchen, D. J. & C. L. Shook. 1996. The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: An analysis and critique. Strategic Management Journal 17(6). 441–458.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199606)17:6<441::AID-SMJ819>3.0.CO;2-GSuche in Google Scholar

Kotz, S. A. & S. Paulmann. 2007. When emotional prosody and semantics dance cheek to cheek: ERP evidence. Brain Research 1151. 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Kwon, O.-W., K. Chan, J. Hao & T.-W. Lee. 2003. Emotion recognition by speech signals. In Proceedings of INTERSPEECH 2003, 125–128. Geneva, Switzerland: ISCA.10.21437/Eurospeech.2003-80Suche in Google Scholar

Laukka, P., H. A. Elfenbein, N. S. Thingujam, T. Rockstuhl, F. K. Iraki, W. Chui & J. Althoff. 2016. The expression and recognition of emotions in the voice across five nations: A lens model analysis based on acoustic features. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111(5). 686. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000066.Suche in Google Scholar

Lê, S., J. Josse & F. Husson. 2008. FactoMineR: A package for multivariate analysis. Journal of Statistical Software 25(1). 1–18.10.18637/jss.v025.i01Suche in Google Scholar

Li, A., Q. Fang & J. Dang. 2011. Emotional intonation in a tone language: Experimental evidence from Chinese. ICPhS 17. 1198–1201.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Y., J. Tao, L. Chao, W. Bao & Y. Liu. 2017. CHEAVD: A Chinese natural emotional audio–visual database. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 8. 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-016-0406-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Liberman, M. Y. 1975. The intonational system of English. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Doctoral dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Y.-H. 2007. The sounds of Chinese. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lin, Y., X. Ye, H. Zhang, F. Xu, J. Zhang, H. Ding & Y. Zhang. 2024. Category-sensitive age-related shifts between prosodic and semantic dominance in emotion perception linked to cognitive capacities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 67(12). 4829–4849.10.1044/2024_JSLHR-23-00817Suche in Google Scholar

Low, L.-S., N. Maddage, M. Lech, L. Sheeber & N. Allen. 2011. Detection of clinical depression in adolescents’ speech during family interactions. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 58(3 PART 1). 574–586.10.1109/TBME.2010.2091640Suche in Google Scholar

Mirsamadi, S., E. Barsoum & C. Zhang. 2017. Automatic speech emotion recognition using recurrent neural networks with local attention. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing, 2227–2231. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2017.7952552.Suche in Google Scholar

Murray, I. R. & J. L. Arnott. 1993. Toward the simulation of emotion in synthetic speech: A review of the literature on human vocal emotion. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 93(2). 1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.405558.Suche in Google Scholar

Pedregosa, F., G. Varoquaux, A. Gramfort, V. Michel, B. Thirion, O. Grisel, M. Blondel, P. Prettenhofer, R. Weiss, V. Dubourg, J. Vanderplas, A. Passos, D. Cournapeau, M. Brucher, M. Perrot & É. Duchesnay. 2011. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 12. 2825–2830.Suche in Google Scholar

Pell, M. D., S. Paulmann, C. Dara, A. Alasseri & S. A. Kotz. 2009. Factors in the recognition of vocally expressed emotions: A comparison of four languages. Journal of Phonetics 37(4). 417–435.10.1016/j.wocn.2009.07.005Suche in Google Scholar

Pierrehumbert, J. B. 1980. The phonology and phonetics of English intonation. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Doctoral dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Plutchik, R. 1962. The emotions: Facts, theories, and a new model. New York, NY: Random House.Suche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2024. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Rodero, E. 2011. Intonation and emotion: Influence of pitch levels and contour type on creating emotions. Journal of Voice 25(1). e25–e34.10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.02.002Suche in Google Scholar

Russell, J. A. & L. F. Barrett. 1999. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76(5). 805. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.805.Suche in Google Scholar

Sawilowsky, S. S. 2009. New effect size rules of thumb. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 8. 597–599. https://doi.org/10.22237/jmasm/1257035100.Suche in Google Scholar

Scherer, K. R. 1986. Vocal affect expression: A review and a model for future research. Psychological Bulletin 99(2). 143. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.99.2.143.Suche in Google Scholar

Schuller, B., G. Rigoll & M. Lang. 2003. Hidden Markov model-based speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of 2003 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech, and signal processing, vol. 2, II–1. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2003.1202279.Suche in Google Scholar

Schuller, B., S. Steidl, A. Batliner, A. Vinciarelli, K. Scherer, F. Ringeval, M. Chetouani, F. Weninger, F. Eyben, E. Marchi, M. Mortillaro, H. Salamin, A. Polychroniou, F. Valente & S. Kim. 2013. The INTERSPEECH 2013 computational paralinguistics challenge: Social signals, conflict, emotion, autism. In Proceedings INTERSPEECH 2013, 14th annual conference of the international speech communication association. Lyon, France.10.21437/Interspeech.2013-56Suche in Google Scholar

Sobin, C. & M. Alpert. 1999. Emotion in speech: The Acoustic attributes of fear, anger, sadness, and joy. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 28(4). 347–365.10.1023/A:1023237014909Suche in Google Scholar

Sun, Y. & R. Wang. 2015. Voice activity detection based on the improved dual-threshold method. In Proceedings of the 2015 international conference on intelligent transportation, big data and smart city, 996–999. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICITBS.2015.252.Suche in Google Scholar

Tupper, P., K. Leung, Y. Wang, A. Jongman & J. A. Sereno. 2020. Characterizing the distinctive acoustic cues of mandarin tones. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 147(4). 2570–2580. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0001024.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Rossum, G. & F. L. Drake. 2009. Python 3 reference manual. North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace.Suche in Google Scholar

Villarreal, D., L. Clark, J. Hay & K. Watson. 2020. From categories to gradience: Auto-coding sociophonetic variation with random forests. Laboratory Phonology: Journal of the Association for Laboratory Phonology 11(1). 6. https://doi.org/10.5334/labphon.216.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Y., S. Du & Y. Zhan. 2008. Adaptive and optimal classification of speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 2008 fourth international conference on natural computation, vol. 5, 407–411. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNC.2008.713.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, T. & Y.-c. Lee. 2015. Does restriction of pitch variation affect the perception of vocal emotions in Mandarin Chinese? Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 137(1). EL117–EL123.10.1121/1.4904916Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, T., Y.-c. Lee & Q. Ma. 2018. Within and across-language comparison of vocal emotions in Mandarin and English. Applied Sciences 8(12). 2629.10.3390/app8122629Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, F. & R. Wayland. 2023. Acoustic properties of vocal emotions in American English and Mandarin Chinese. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 153(3_supplement). A294. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0018904.Suche in Google Scholar

Wickham, H. 2016. Ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag.10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9Suche in Google Scholar

Wundt, W. 1905. Fundamentals of physiological psychology. Leipzig: Engelmann.Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, Y. 2011. Speech prosody: A methodological review. Journal of Speech Sciences 1(1). 85–115. https://doi.org/10.20396/joss.v1i1.15014.Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, D. & Y. Tian. 2015. A comprehensive survey of clustering algorithms. Annals of Data Science 2(2). 165–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40745-015-0040-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Yuan, J., L. Shen & F. Chen. 2002. The acoustic realization of anger, fear, joy and sadness in Chinese. In Proceedings of INTERSPEECH, 2025–2028. ISCA.10.21437/ICSLP.2002-556Suche in Google Scholar

Zhou, K., B. Sisman, R. Liu & H. Li. 2022. Emotional voice conversion: Theory, databases and ESD. Speech Communication 137. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2021.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Cross-language perception of the Japanese singleton/geminate contrasts: comparison of Vietnamese speakers with and without Japanese language experience

- The association between phonological awareness and connected speech perception: an experimental study on young Chinese EFL learners from cue processing perspective

- Modeling the acoustic profiles of vocal emotions in American English and Mandarin Chinese

- The prosody of cheering in sports events: the case of long-distance running

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Cross-language perception of the Japanese singleton/geminate contrasts: comparison of Vietnamese speakers with and without Japanese language experience

- The association between phonological awareness and connected speech perception: an experimental study on young Chinese EFL learners from cue processing perspective

- Modeling the acoustic profiles of vocal emotions in American English and Mandarin Chinese

- The prosody of cheering in sports events: the case of long-distance running