Abstract

Mnong Râlâm is a South Bahnaric language (Austroasiatic) that is traditionally described as preserving a voicing contrast in onset obstruents, contrary to other languages of the Mnong/Phnong continuum. Acoustic results yield evidence that this voicing distinction is less robust than previously suggested and is redundant with a register contrast realized on following vowels through modulations of F1 at vowel onset (and more limited variations of F2 and voice quality). A perception experiment also shows that F1 weighs heavier than closure voicing in identification. The existence of a language in which voicing and register are redundant allows us to revisit previous models of registrogenesis. It suggests that the acoustic properties of register may develop and become distinctive while voicing is still present rather than as a direct consequence of devoicing. The unexpected discovery of register in Mnong Râlâm also challenges previous reconstructions of Proto-South-Bahnaric, in which only voicing is postulated, based on hitherto limited available descriptive materials.

1 Introduction

Eastern Mnong is an Austroasiatic language of the South Bahnaric branch spoken in the Highlands of South-Central Vietnam. As most other South Bahnaric languages, it has been claimed to preserve a voicing contrast in onset obstruents. In this paper, we present acoustic and perceptual evidence that an Eastern Mnong variety, Râlâm, has a form of register, contrary to expectations, and show that this register is largely redundant with onset voicing. We reassess previous hypotheses about register development based on this conservative register system.

1.1 Register and its development

The term register has a confusingly wide array of uses, in linguistics and beyond. In sociolinguistic and linguistic anthropology, it is used to refer to varieties of language used in specific social contexts, typically defined by formality or politeness. In speech pathology and research on singing, it is used to designate vocal settings resulting in different pitch ranges and voice qualities. In Southeast Asian phonetics and phonology, however, the term has been used since the 1950s to designate a phonological contrast phonetically realized on vowels or rhymes through the modulation of a bundle of acoustic properties such as pitch, voice quality and vowel quality (Ferlus 1979; Haudricourt 1965; Henderson 1952; Huffman 1976). It is found in most Austroasiatic languages but is also attested in Austronesian languages of the Chamic branch and in Javanese (in which it has been designated by a variety of terms, like light-heavy, tense-lax, stiff-slack or clear-breathy). The most common form of Southeast Asian register derives from the loss of an original voicing contrast in onset obstruents (cf. Diffloth 1982; Gehrmann 2022 for less common diachronic sources). The accepted view is that in register languages, former voiced obstruents devoiced and transphonologized into a low register composed of a combination of features such as a breathy or lax voice, a low pitch and a lower F1 (typically realized as falling onglides in more open vowels). Syllables headed by voiceless obstruents underwent more limited changes and developed a high register in which vowels exhibit a modal voice, a higher pitch and limited vowel quality changes (weak rising onglides in close vowels). Note that despite phonetic and diachronic similarities with tone, register is distinct in that it uses phonetic properties that are rarely used in tone systems (like vowel quality) and does not necessarily rely on pitch as its primary property (in fact, it does not always involve pitch). Moreover, register is not typically subject to autosegmental alternations common in tone systems: no examples of register sandhi or OCP are attested, and register seems inseparable from onsets in Cham word games (Brunelle 2005). Only limited register spreading through sonorants has been reported (cf. §2.1.1).

Several articulatory hypotheses have been formulated to account for registrogenesis, i.e., the development of register from onset voicing. The earliest proposal is that registers developed from the spreading of laryngeal tension/laxness from onsets to following vowels before devoicing took place (Ferlus 1979; Haudricourt 1965). While this could account for the voice quality and pitch modulations found in many register systems, it does not easily capture the vowel quality differences that characterize them. It has also been proposed that tongue root advancement/retraction is instrumental in registrogenesis and remains the primary articulatory correlate of the register contrast (Gregerson 1976). However, while tongue root position could easily explain the vowel quality differences between registers, it does not account for voice quality and pitch modulations. A third scenario that has been put forward is that voiced stops evolve into lax voiced stops accompanied by longer formant transitions triggering strong patterns of diphthongization in the low register while voiceless stops evolve into tense stops with shorter transitions (Wayland and Jongman 2002). The presence of a moderate aspiration that could be viewed as a consequence of laxness is instrumentally attested in the low register in many register languages (Brunelle et al. 2019; Tạ et al. 2022) but it is unclear why lax stops should have longer transitions and why these longer transitions would have different outcomes in close and open vowels. The last diachronic explanation proposed in previous work is that register properties are an outcome of the coarticulatory effects of the lowering of the larynx often observed in the production of voiced stops. This explanation has been entertained by a number of authors since register was first described (Ferlus 1979; Gregerson 1976; Henderson 1952; Thurgood 2000; 2002]) and it could account for the acoustic properties of register: the lengthening of the supraglottal tubes caused by larynx lowering should mechanically affect formants, and larynx lowering should also shorten the vocal folds, which should indirectly lower f0 (Honda et al. 1999). However, it is less clear how larynx lowering would affect voice quality and, ultimately, there is only limited actual evidence for its involvement in register production (cf. Brunelle 2010: for evidence from Javanese).

There has been a flurry of instrumental descriptions of register systems since the 1980s (Abramson et al. 2004, 2007], 2015]; Adisasmito-Smith 2004; Lee 1983; Thongkum 1987; 1988]; 1989]; 1990]; Thongkum et al. 1991; Thurgood 2004; Watkins 2002; Wayland and Jongman 2003). These studies suggest significant variability in the acoustic realization of register, some systems making a relatively balanced use of multiple cues, while others clearly favor one cue over others. However, as none of these register systems appears to have developed recently, their acoustic properties do not directly inform us about registrogenetic mechanisms. Fortuitously, recent research on Austroasiatic and Chamic languages spoken in southern Vietnam has uncovered register systems in which residual closure voicing in onset obstruents is still a frequent characteristic of the low register. In Southern Raglai (Chamic), Jarai (Chamic) and Chrau (Austroasiatic), some speakers produce a significant proportion of their low register stops with partial closure voicing (Brunelle et al. 2022, 2024]; Tạ et al. 2022). In Chru (Chamic), a handful of older men even have quasi-redundant voicing and register, while other speakers, especially younger women, rely almost exclusively on register cues (Brunelle et al. 2019). It turns out that in all these languages, F1 is the primary phonetic property of register and that their low register stops are not accompanied by dramatic aspiration. This suggests a more direct path between the original voicing contrast and vowel quality modulations than previously assumed.

Additional evidence from languages with conservative register systems, especially systems with redundant stop voicing and register contrasts like that found in older Chru men, could allow us to better understand how registrogenesis unfolds. As we will see in the next section, Mnong Râlâm is such a language.

1.2 Mnong

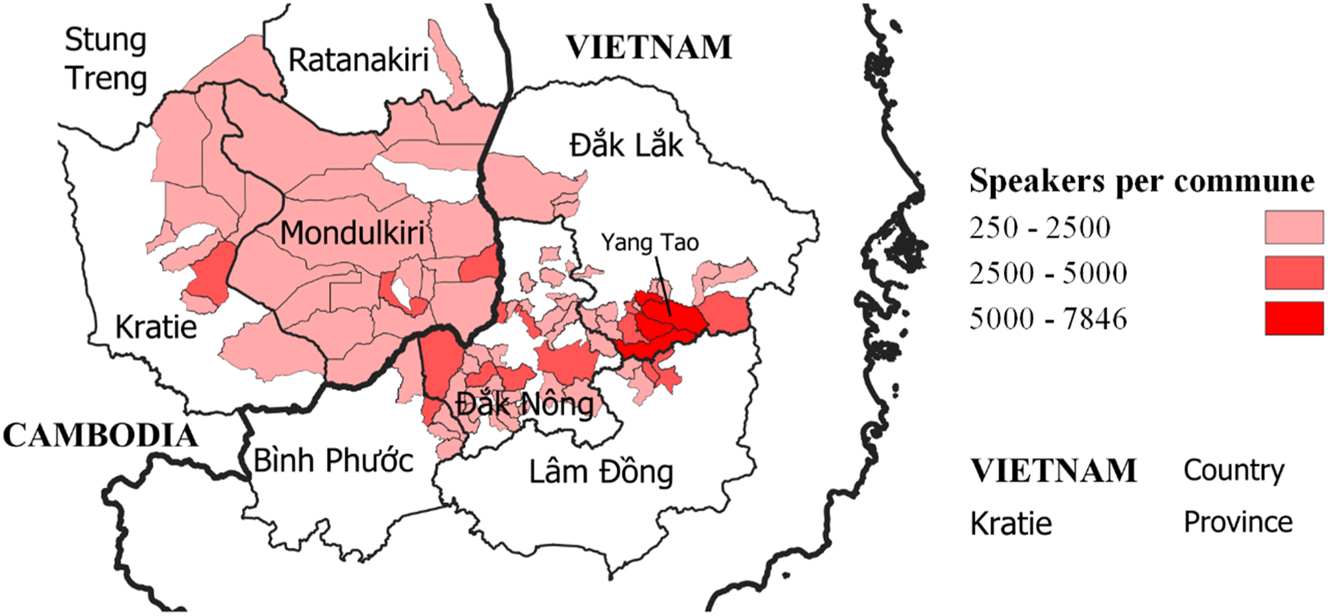

Mnong (also Bunong or Phnong) is a term used to refer to a continuum of loosely related varieties of Southern Bahnaric (see Figure 1) spoken by about 130,000 people in Vietnam and about 40,000 people in Cambodia (General Statistics Office of Vietnam 2020; National Institute of Statistics 2009). It includes three main varieties that are not fully mutually intelligible according to native speakers (Thomas and Headley 1970). The exact geographical distribution of these three varieties is not fully documented, but Central Mnong (also Phnong) is spoken in Cambodia and in contiguous areas of the Vietnamese provinces of Đắk Lắk, Đắk Nông and Bình Phước, Southern Mnong is spoken by communities scattered all over Đắk Nông province, Vietnam, and Eastern Mnong is spoken in the southern part of Đắk Lắk province and in the northern part of Lâm Đồng province, Vietnam.

Geographical distribution of Mnong/Bunong/Phnong speakers (only communes with more than 250 speakers are represented). The 2019 Vietnamese census also reports about 5000 additional speakers in Quảng Nam province, Vietnam, 450 km north of Yang Tao.

In this paper, we focus on a dialect of Eastern Mnong, Râlâm spoken in the commune of Yang Tao, in the district of Lăk, in Đắk Lắk province, Vietnam. Phonologically, it is nearly identical to Râlâm varieties spoken in the neighboring hamlets of Njuñ and Lê, that were described in previous work (Blood 1976; Đinh 2005).

Central and Eastern Mnong are described as having different laryngeal contrasts in onset stops, while the phonology of Southern Mnong has to our knowledge never been documented. Central Mnong has a well-developed register contrast (Butler 2010; Phillips 1973; Vogel and Filippi 2006). Butler (2010) finds that there is no longer any closure voicing in low register stops and that its register contrast is based on voice quality and diphthongization. In contrast, Eastern Mnong, and more specifically Râlâm, is traditionally described as preserving a voicing contrast in obstruents and is not reported to have register (Blood 1976; Đinh 2005). The consonant system of Râlâm is given in Table 1:

Consonant system of Mnong Râlâm (adapted from Đinh 2005).

| p | t | c | k | Ɂ |

| pʰ | tʰ | cʰ | kʰ | |

| b | d | ɟ | ɡ | |

| ɓ | ɗ | ʄ | ||

| s | h | |||

| m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| w | l,r | j |

Thus, Râlâm onset stops should include contrastive voiceless and voiced stop series (bolded in Table 1), along with aspirated and implosive series. Blood (1976) also reported that voiced stops are optionally prenasalized. However, during a non-academic trip to Đắk Lắk in 2010, the first author noticed that register-like properties accompany Râlâm plain voiced stops. This is potentially interesting as the existence of redundant voicing and register contrasts would suggest an early stage of register development that could allow us to better understand incipient registrogenesis. For this reason, it was decided to conduct a proper phonetic study of the laryngeal contrast found in Mnong Râlâm onset stops.

1.3 Research questions

In this paper, we attempt to answer several empirical questions to determine if Mnong Râlâm has registers and, if yes, what it can reveal about early registrogenesis.

Does Mnong Râlâm still preserve a voicing contrast in onset stops?

Does Mnong Râlâm have a register system? If it does:

What are the acoustic properties of the Râlâm register contrast?

What are the perceptual properties of the Râlâm register system?

If Mnong Râlâm has redundant onset stop voicing and register, is there evidence of a trade-off between the two properties?

Two experiments were conducted to investigate these questions: a production experiment and a perceptual one.

2 Production experiment

The production experiment was conducted in the hamlet of Buôn Dơng, in the commune of Yang Tao (district of Lăk, Đắk Lắk province, Vietnam) in March 2019. This venue was selected for its accessibility and because its dialect is similar to the varieties studied in Blood (1976) and Đinh (2005).

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Procedure

Twenty-three native speakers (12 women) of Mnong Râlâm born between 1944 and 1992 (mean: 1975, sd: 15) were recorded in March 2019. They were all originally from the commune of Yang Tao, except for one man who was born in Buôn Ma Thuột, the province capital, but moved back to Yang Tao at the age of four years old. They were all fluent in Vietnamese, and 21 of them also spoke Rade, a Chamic language that is the lingua franca used between minority groups in the province of Đắk Lắk. All spoke primarily Mnong in their daily lives, except one who was married to an ethnic Vietnamese man and spoke Mnong and Vietnamese equally. Five participants had lived in other regions of Vietnam (Buôn Ma Thuột, Hồ Chí Minh City, Kontum) for periods of time ranging from two to eleven years.

Sixty real words comprising target syllables made up of combinations of all dental and velar onsets /t, k, tʰ, kʰ, d, ɡ, ɗ, s, n, ŋ, r, l/ and the five vowels /iː, ɛː, aː, ɔː, uː/ were selected. The full wordlist is given in Appendix I. Open syllables were preferred; when they were not available, syllables closed by sonorants were chosen. Target words were either monosyllables or sesquisyllables ending in target syllables. Sequisyllables are disyllables in which the final stressed syllable has the full array of contrasts while the initial syllable, or presyllable, has a reduced inventory (Thomas 1992).

While the register contrast is normally limited to plain obstruents, it must be noted that many Austroasiatic and Chamic languages have a process of register spreading in which sonorant-initial syllables acquire the register of the preceding syllable or stop (Brunelle and Phú 2019; Friberg and Hor 1977; Huffman 1967; Thurgood 1999). For example, Eastern Cham /t̥anaw/ ‘pound’, where the subscript circle represents the low register, is either realized as [t̥an̥aw] or [n̥aw], which is evidence that register has generalized from stop-initial syllables to sonorant-initial ones. In order to test if this happened in Mnong Râlâm, we included in the wordlist sonorant-initial words (called register neutral sonorants below), as well as sonorants-initial syllables preceded by voiced/voiceless stops or by presyllables headed by voiced/voiceless stops (called low and high register sonorants below).

Target words were read four times in a fixed frame sentence, randomized in SpeechRecorder (Draxler and Jänsch 2004). As few participants could read Mnong, the first author provided the words in Vietnamese to the participants, who had to translate them in Mnong and pronounce them in the frame sentence in (1). A female native assistant born in 1988, H Hê Bkrông, was present during all the recordings and provided clarification in Mnong whenever necessary.

| aɲ | ŋəj | ____ | nɔ | ɛh | rip | |

| I | say | ___ | in.order | 3PS | record | |

| “I say ____ so that he records it”. | ||||||

Recordings were conducted in the Yang Tao communal house, a wooden building located off a dirt road, chosen because it was relatively quiet and offered good recording conditions. Two important signals were acquired during the experiment: an audio signal recorded with a Shure Beta 53 headworn microphone, and an EGG signal recorded with an electroglottograph Glottal Enterprises EG2-PCX. They were channeled through a Steinberg UR44 preamplifier and recorded in SpeechRecorder on a PC laptop. The EGG signal was used to track the onset and offset of voicing; all other measures were obtained from the audio signal. Two additional signals, a larynx height tracking channel recorded with the EG2-PCX and a back-up audio channel recorded with a low-quality microphone, will not be reported here.

All recordings made for this study are available on the Pangloss collection (https://pangloss.cnrs.fr/corpus/Mnong_R%C3%A2l%C3%A2m) and annotated files can be downloaded from the Nakala archive (https://nakala.fr/10.34847/nkl.a35d1if0).

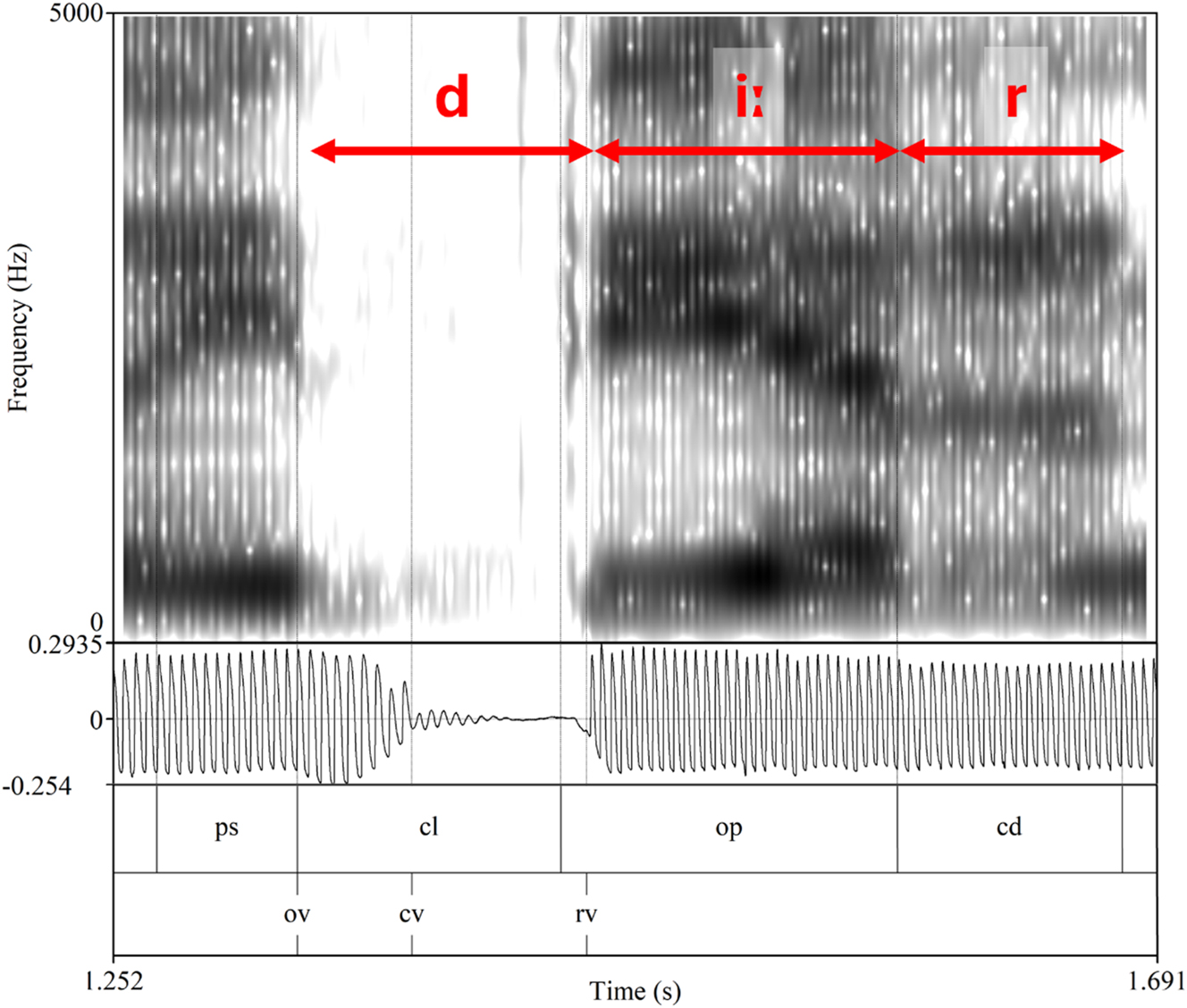

2.1.2 Data analysis

Target words were annotated in Praat Textgrids. The beginnings of the consonant and of the open phase of the rhyme (i.e., the release of the closure in stops and the beginning of the vowel in fricative- and sonorant-headed syllables) as well as the endpoints of the vowel and coda (if any) were labeled based on the acoustic signal. The onset of voicing, as well as any cessation and resumption of voicing were labelled based on the EGG signal. Important landmarks are illustrated in Figure 2.

Annotation of target word /diːr/ ‘to avoid’. Top: spectrogram; middle: EGG signal; bottom: acoustic landmarks (ps, previous sonorant; cl, closure; op, open phase; cd, coda; ov, onset of voicing; cv, cessation of voicing; rv, resumption of voicing).

Automatic measures were made using Praatsauce, a Praat implementation of VoiceSauce (Kirby 2018; Shue et al. 2011). Besides the duration of each interval and the time of each laryngeal landmark, spectral measures (f0, H1-H2, H1-A1, H1-A3, CPP, F1, F2, F3) were made at each millisecond of the vowel. The effect of formants on harmonic amplitudes were then corrected using the formula in Iseli and Alwan (2004): adjusted measures will therefore be reported with stars (H1*-H2*, H1*-A1*, H1*-A3*). Since the measurements windows were 25 ms wide, the initial and final 12 measures of the vowels were excluded as they are spuriously affected by measures made during the preceding and following segments.

Outliers were excluded in two ways. To detect local tracking errors, f0, F1, F2 and F3 were speaker-normalized into z-scores, and derivatives of these z-scores were obtained. All derivatives exceeding −0.5 z and 0.5 z were deemed to indicate abrupt jumps and were excluded as spurious measures. Global tracking errors were then excluded by calculating means and standard deviations for f0, F1, F2 and F3 for each combination of speaker, vowel and voicing/register and by deleting any measure exceeding the mean by more than three standard deviations. All tracking errors were left blank and any spectral measure (H1*-H2*, H1*-A1*, H1*-A3*) derived from an excluded f0 or formant value was also excluded. The proportion of data removed for each indicator is given in Table 2.

Proportion of data removed for each acoustic indicator.

| f0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | H1*-H2* | H1*-A1* | H1*-A3* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 % | 2.6 % | 2.5 % | 12 % | 5 % | 6.9 % | 15.8 % |

Data recorded from different speakers were normalized to allow their aggregation in charts and in statistical models. Each acoustic measure was z-normalized by speaker. To facilitate interpretation of the results, z-scores were then converted into familiar scales using means and standard deviations obtained from all speakers (weighted mean of all speakers + z-score × mean standard deviation of all speakers), but statistical results are equivalent to those that would be obtained directly from z-scores.

2.1.3 Statistical treatment

We evaluated the statistical significance of the voicing/register contrast and of other linguistic factors on relevant phonetic properties by fitting linear mixed models to the data using the lmerTest package in R (Kuznetsova et al. 2017). The phonetic properties chosen as dependent variables include the VOT of plain stops and the mean f0, H1*-H2*, H1*-A1*, H1*-A3*, CPP, F1 and F2 over the initial 10 sampling points (10 ms) of vowels in syllables with plain stops. As will be shown in §2.2.2, this portion of the vowel consistently contains the most significant differences between voicing/register, as register effects in vowels immediately follow the onset rather than spreading uniformly over the entire vowel. The fixed effects used in the models were voicing/register, vowel quality, and place of articulation of onsets, as well as all two-way interactions of these fixed factors (three-way interactions were omitted as they led to overfitting). Random slopes for both subject and word were also incorporated. These maximal models were progressively simplified from the top down by iteratively dropping the interaction with the smallest F-value in the model’s ANOVA as long as the resulting model had a significantly lower Akaike information criterion (AIC) score than the preceding model, or a higher or equal but not statistically significant AIC difference. It is important to note that we did not attempt to run statistical models on the acoustic properties of words with onsets other than plain stops, either because they do not contrast in voicing/register or, in the case of sonorants, because there were not enough target words to fit meaningful models.

In mixed models conducted on vocalic properties, the intercept was set to the high register (or voiceless) dental onset and the vowel /ɔː/ (i.e., target syllable /tɔː/). The reason for choosing an open mid vowel is that it allows easy comparisons with phonetically close and open vowels. Back /ɔː/ was preferred to /ɛː/ because it had fewer gaps in the wordlist (cf. word list in Appendix 1). The predicted effects of vowels other than /ɔː/ on dependent variables can be computed from the model summaries in Appendix II by adding the estimates of their main effects or interactions to those of the reference vowel /ɔː/.

We used Cohen’s d’s to determine the weight of each acoustic property in the realization of the voicing/register contrast in the first 10 ms of the vowel (Brunelle et al. 2020, 2022], 2024]; Clayards et al. 2008; Cohen 1988; Tạ et al. 2022). Cohen’s d’s were computed by dividing the difference between the vowel-weighted and subject-weighted means of each property for each voicing/register category by its standard deviation. A large absolute Cohen’s d (>|0.8|) indicates a substantial difference between the two distributions under investigation, suggesting they could contribute to maintaining the contrast.

2.2 Results

In this section, we first look at the realization of voicing in onsets stops (§2.2.1) and then turn to possible acoustic properties of register on following vowels (§2.2.2).

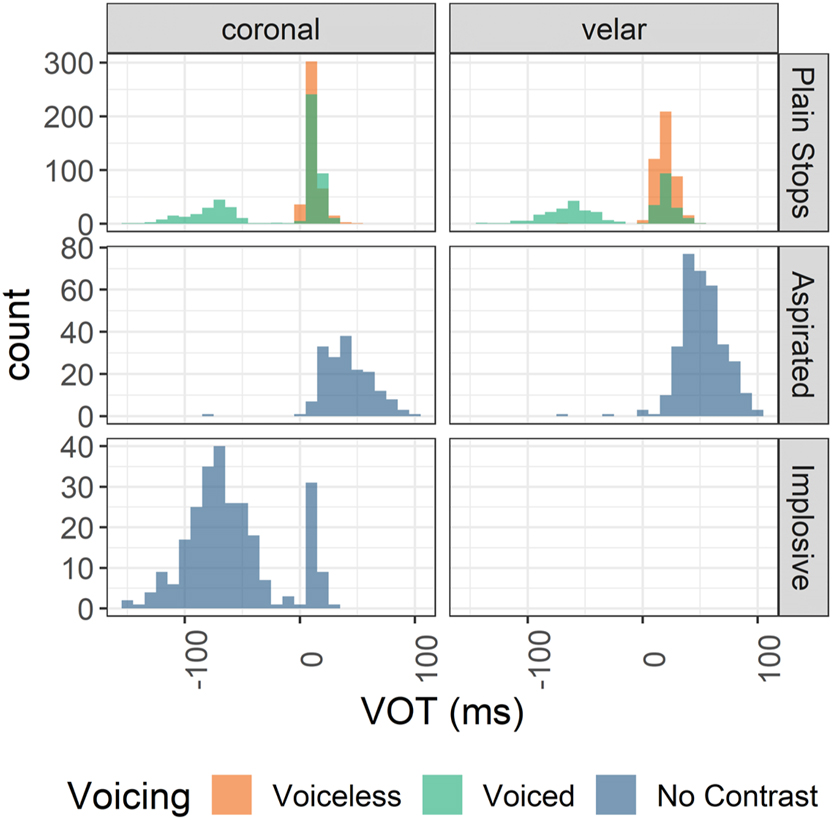

2.2.1 Laryngeal contrasts in onsets

The distribution of VOT in onset stops is reported in Figure 3. Voiceless stops have a short positive VOT (mean = 15.1 ms), as expected, but voiced stops have an unexpected bimodal distribution. Most voiced stops exhibit a strong negative VOT (mean = −21.3 ms) characteristic of true voicing, but a significant proportion also have a positive VOT that is statistically undistinguishable from that of voiceless stops (see Table 3, Appendix II). Unsurprisingly, aspirated stops have a long lag VOT (mean = 47.2 ms). Implosives generally have a long lead VOT (mean = −62 ms) but a non-negligible minority have a slightly positive VOT (42/262, right-hand peak in Figure 3). The reason for this positive VOT is unknown, but they are for the most part prenasalized.

VOT distribution in different types of stops.

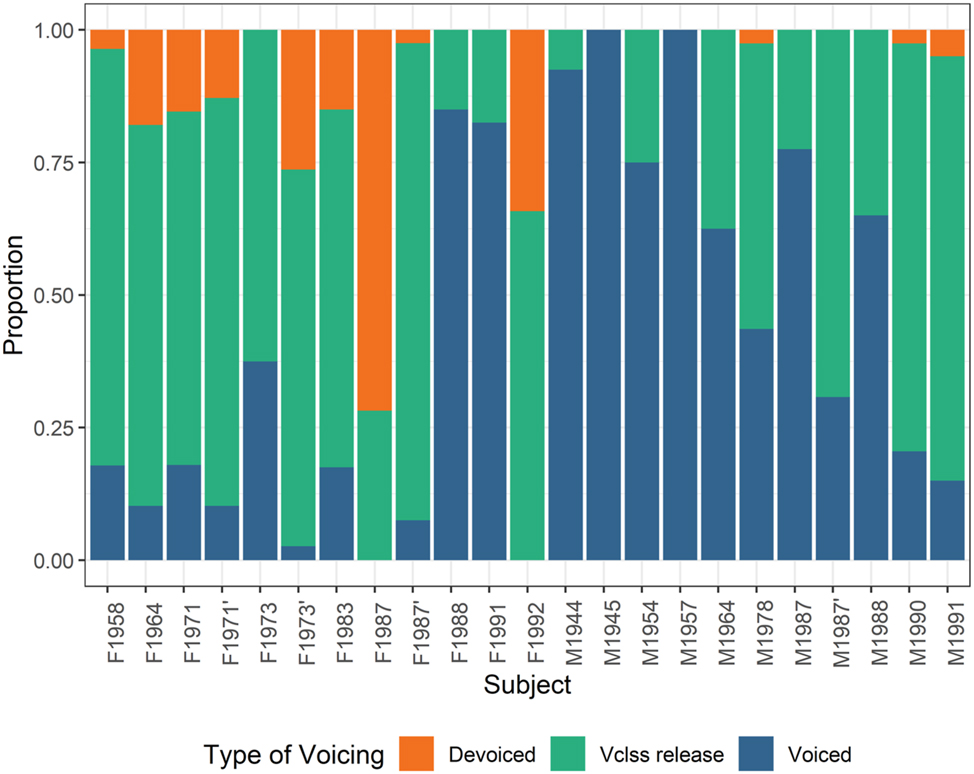

To better understand the bimodal VOT distribution of plain voiced stops, they were broken down into three types: fully voiced stops have voicing throughout their closure; devoiced stops either have voiceless closures or carryover voicing from the previous sonorant over less than 30 % of their closures; voiced stops with a voiceless release have voicing over more than 30 % of their closure but are devoiced before the burst. An example of a voiced stop with a voiceless release was already given in Figure 2.

The breakdown of phonological voiced stops by phonetic realization is given in Figure 4. Few voiced stops are fully devoiced and full devoicing is more prevalent in women than men (yet only F1987 devoices more than half of her voiced stops). Partial devoicing is much more common: most voiced tokens have a voiceless release, especially in women. Tokens with fully voiced closures are rare in women but common in men, especially older ones. Overall, women tend to exhibit more devoicing, full or partial, than men. Since a similar sex asymmetry was obtained in neighboring languages studied with a comparable methodology, it is likely that this partly reflects anatomical differences (Brunelle et al. 2020, 2022], 2024]; Tạ et al. 2022), but the magnitude of the age and sex differences is much greater in Mnong Râlâm. Finally, despite their smaller supraglottal cavity, velars undergo less devoicing than coronals (Coronals: voiced 34.6 %, voiceless release 57.2 % voiceless 8.2 %; Velars: voiced 51.9 %, voiceless release 37.3, voiceless 10.7 %). This tendency is found irrespective of sex or following vowel.

Proportion of phonological voiced stops that are fully devoiced, have a voiceless release or are fully voiced, by speaker. Speakers are organized by sex (F/M) and year of birth.

Importantly, the duration of voiced stop closure does not seem to be affected by their type of voicing. Fully voiced tokens have a shorter duration (mean: 73 ms) than devoiced stops (mean: 89 ms) and voiced stops with a voiceless release (mean: 89 ms), but this is not statistically significant in a mixed model in which Place, Vowel and Voicing Type and their two-way interactions are included as fixed effects, and Subject and Word as random effects. Inspection of the data reveals that durational differences are attributable to a combination of men’s faster speech rate and of the high prevalence of fully voiced stops in their speech.

The upshot is that Mnong Râlâm voiced stops by and large preserve a voicing contrast characterized by the presence of vocal fold vibrations during the closure, even if partial devoicing is frequent.

2.2.2 Registral properties on vowels

Now that it has been established that closure voicing is still present in onset stops, let us examine the following vowels to determine if there is any evidence that register properties have developed in Râlâm. For the sake of simplicity, we will use the terms high and low registers to refer to the two contrastive series in the rest of this section, without any a priori assumption about the phonological nature of the contrast.

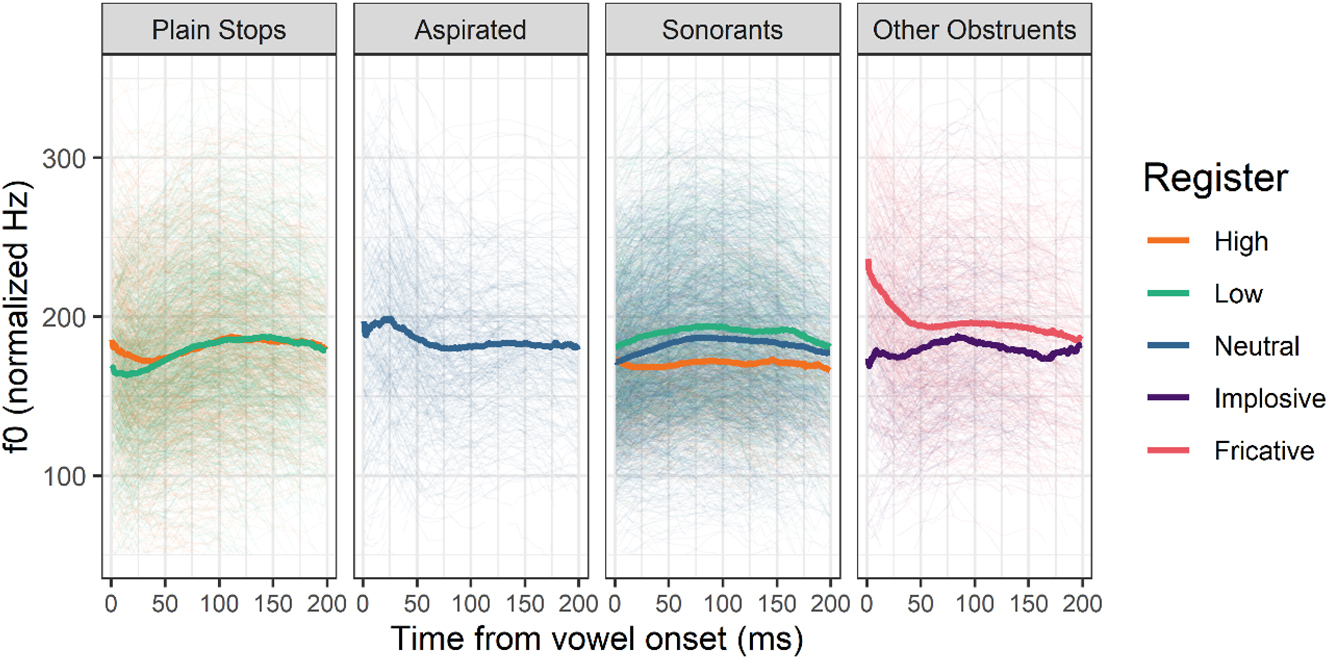

In Figure 5, the f0 of vowels following various types of onsets is reported over their first 200 ms. F0 is marginally higher at the very beginning of the vowel following high register plain stops, but this is only significant in velars (RegisterLow: β = −9.63 Hz, t = −0.908, p = 0.415, RegisterLowPlaceVelar: β = −53.992 Hz, t = −7.327, p = 0.002, see Table 4 in Appendix II).

Normalized f0 of the first 200 ms of vowels following various types of onsets. Thick lines represent means, thin lines individual observations. Aspirates /tʰ, kʰ/, the implosive /ɗ/ and the fricative /s/ do not contrast in register and are included for comparison.

Differences between words with initial sonorants (neutral), and syllables with onset sonorants preceded by different registers are also small: unexpectedly, a low f0 seems to be found on sonorants preceded by voiceless stops or high register syllables. F0 starts very high after fricative /s/, is a bit higher before aspirated than before plain stops and is comparable to that of low register plain stops after implosives.

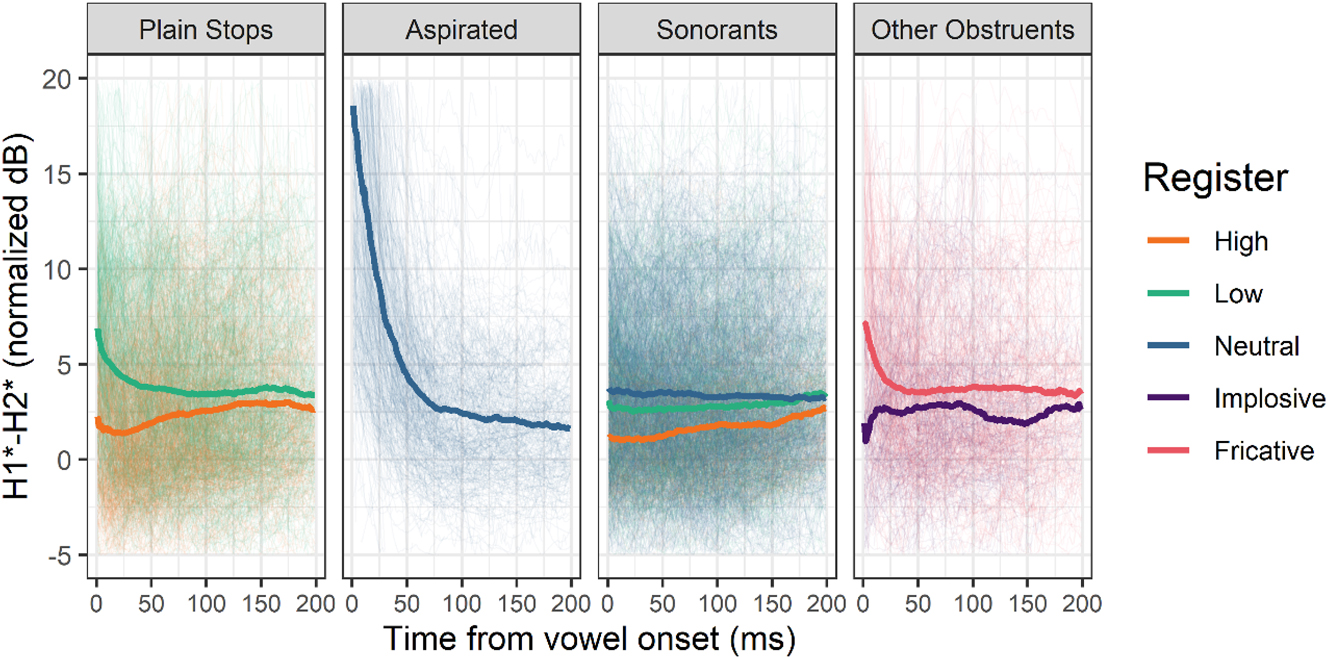

Voice quality differences between the low and high registers are small and are not captured by all voice quality indicators. In Figure 6, H1*-H2* differences are visible in the first 100 ms after plain stops, with low register stops being a bit breathier or laxer, but they do not reach statistical significance (RegisterLow: β = 2.772 dB, t = 0.753, p = 0.466, see Table 5 in Appendix II). Differences between high and low register sonorants appear even smaller (neutral sonorants pattern with low register ones). Vowels following aspirated stops have a high H1*-H2* indicative of their irregular airflow, while those following fricative /s/ and implosive /ɗ/ exhibit a slightly higher and slightly lower H1*-H2* than neutral sonorants, reflecting their moderately open and constricted glottal settings. Overall, H1*-A1* exhibits the same general tendencies as H1*-H2*, but effects are weaker (see Table 6 in Appendix II).

Normalized H1*-H2* of the first 200 ms of vowels following various types of onsets. Thick lines represent means, thin lines individual observations. Aspirates /tʰ, kʰ/, the implosive /ɗ/ and the fricative /s/ do not contrast in register and are included for comparison.

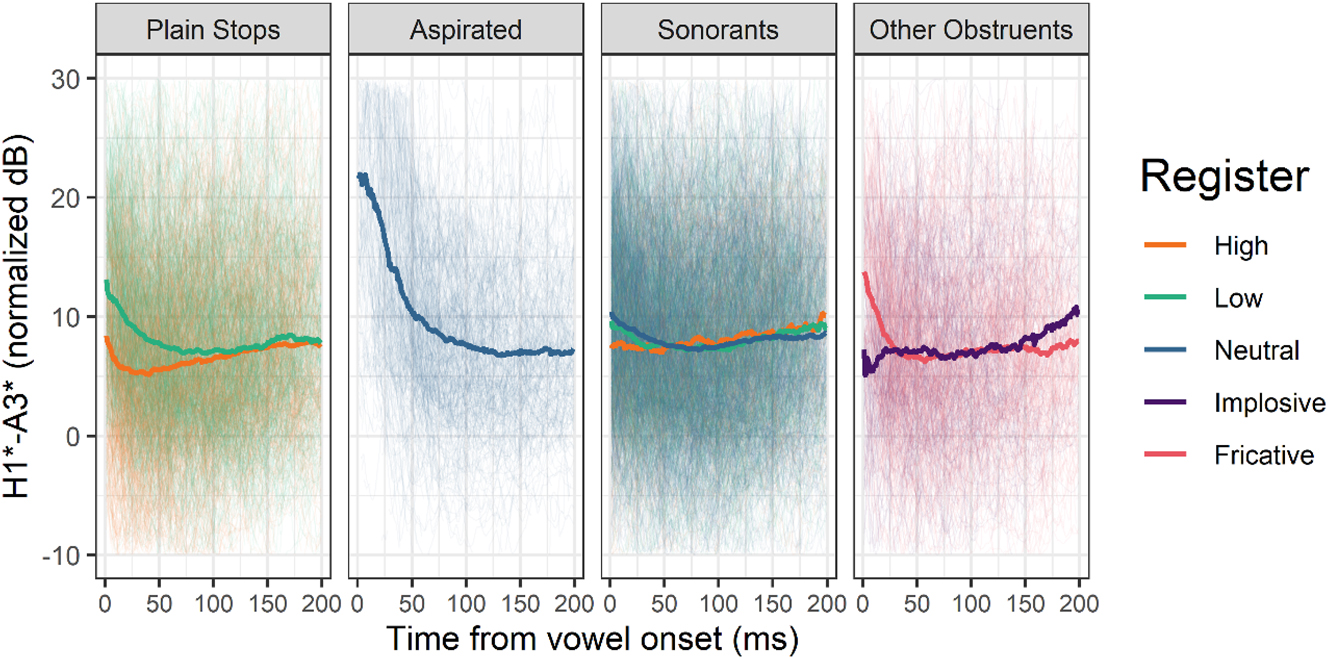

H1*-A3*, another spectral slope indicator, exhibits larger and more significant register differences in Figure 7, with a significantly steeper slope in the low register after plain stops (RegisterLow: β = 6.095 dB, t = 3.986, p = 0.003, see Table 7 of Appendix II). However, these results should be taken with a grain of salt as 15.8 % of H1*-A3* measures had to be excluded because of tracking errors. H1*-A3* differences are more limited after the different types of sonorants, even if low register sonorants seem a bit breathier than high register ones. Just as for H1*-H2*, H1*-A3* values are very high after aspirated stops, and they seem to indicate some breathiness after fricative /s/ and a tense voice after implosive /ɗ/, which reflects the effect of their respective laryngeal settings.

Normalized H1*-A3* of the first 200 ms of vowels following various types of onsets. Thick lines represent means, thin lines individual observations. Aspirates /tʰ, kʰ/, the implosive /ɗ/ and the fricative /s/ do not contrast in register and are included for comparison.

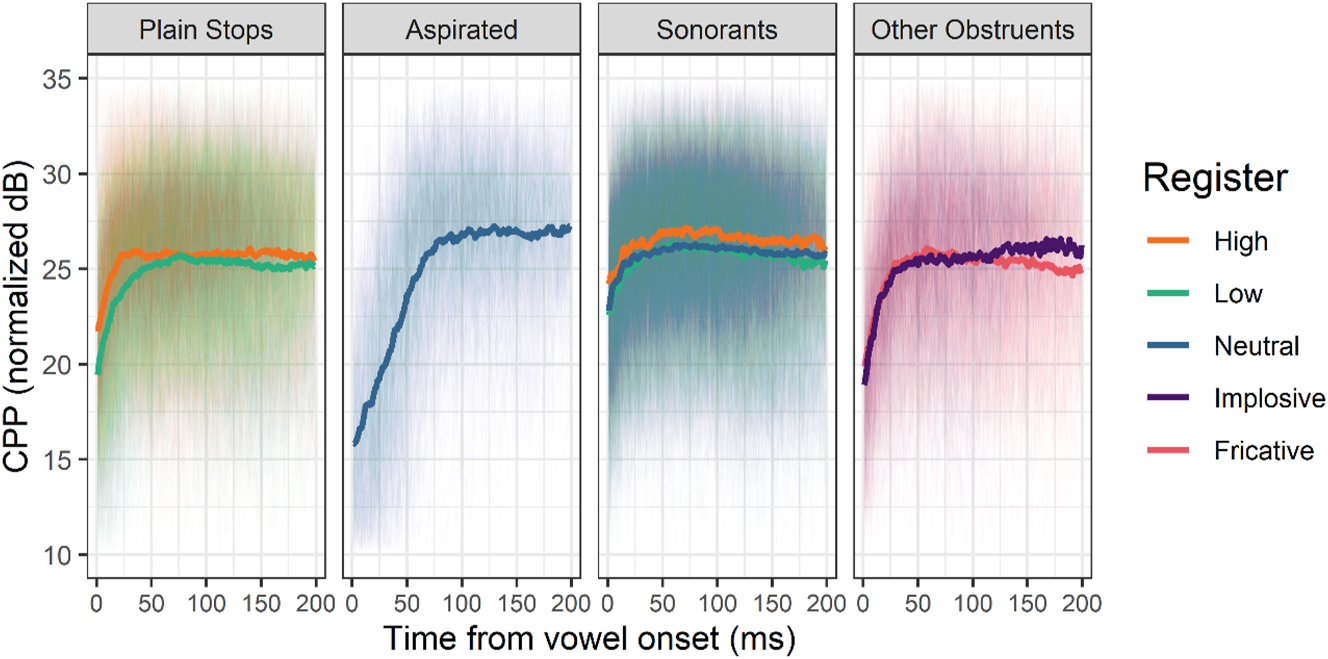

The last voice quality indicator is cepstral peak prominence (CPP), which correlates positively with periodic glottal cycles and negatively with spectral noise. We see in Figure 8 that it is slightly higher in the high register for the first 50 ms after plain stops, indicating a more modal phonation. This difference does not reach statistical significance in dentals but is more robust in velars (RegisterLow: β = −1.826 dB, t = −2.282, p = 0.087, RegisterLow:PlaceVelar: β = −2.418 dB, t = −4.327, p = 0.013, see Table 8 in Appendix II). Note that similar results are obtained even if we run models with values averaged from measurement windows spanning later portions of the vowel (20–30 ms and 30–40 ms).

Normalized CPP of the first 200 ms of vowels following various types of onsets. Thick lines represent means, thin lines individual observations. Aspirates /tʰ, kʰ/, the implosive /ɗ/ and the fricative /s/ do not contrast in register and are included for comparison.

There are no clear CPP differences between the three types of sonorants either. As for aspirated stops, fricatives and implosives, they all have a low initial CPP, indicating a perturbation of regular phonation at vowel onset because of the laryngeal settings of these consonants.

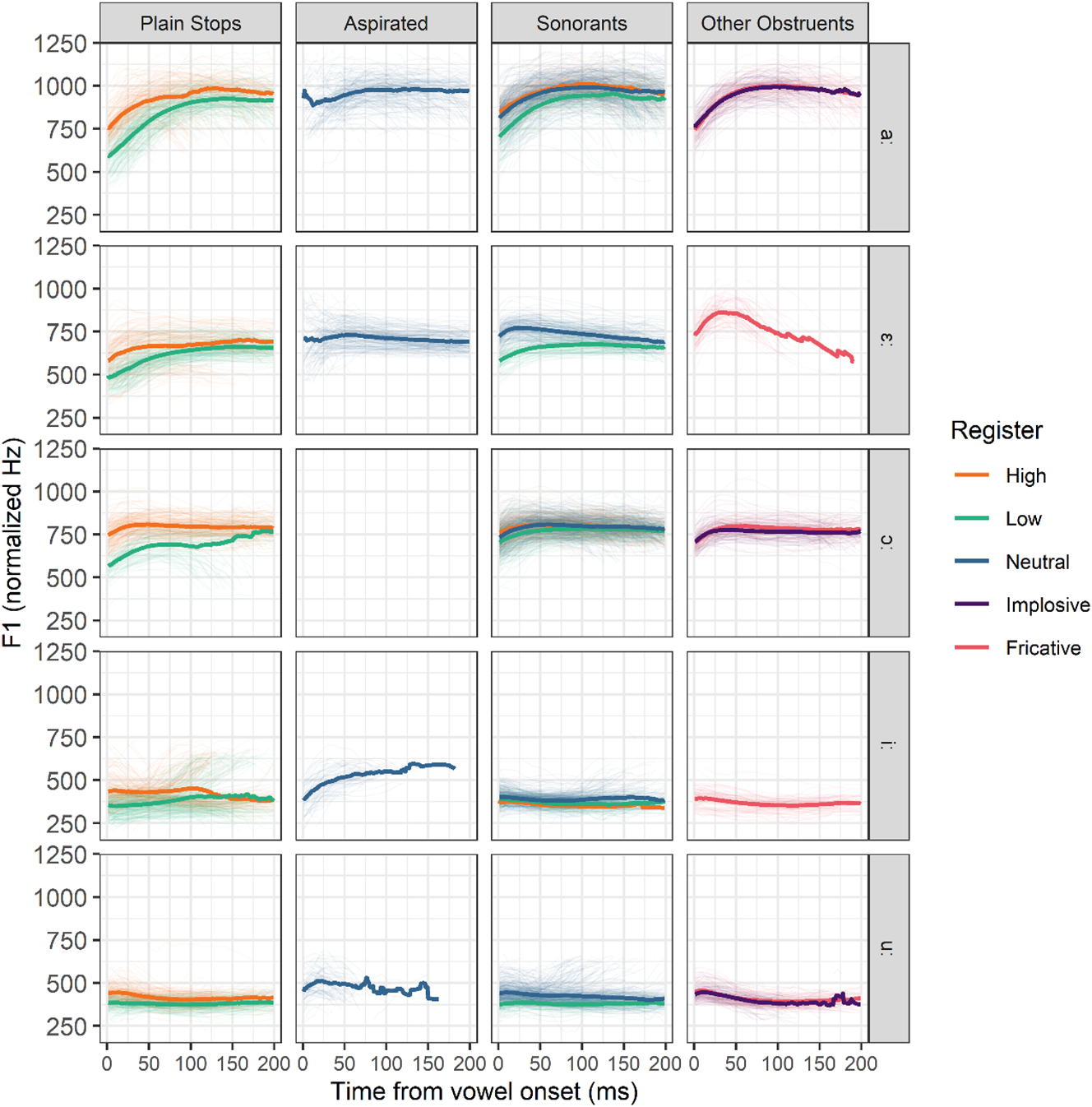

Turning to formants, F1 differences between registers are robust after plain stops, as can be seen in Figure 9. Overall, low register vowels have a lower F1 than high register vowels following plain stops (RegisterLow: β = −222.563 Hz, t = −3.036, p = 0.039, see Table 9 in Appendix II). Differences between registers appear greater in open and mid vowels in Figure 9 but these additional effects are not significant. Register differences in F1 are negligible after sonorants, except in /aː/. Aspirates, fricative /s/ and implosive /ɗ/ seem to mostly pattern with high register plain stops.

Normalized F1 of the first 200 ms of vowels following various types of onsets. Thick lines represent means, thin lines individual observations. Aspirates /tʰ, kʰ/, the implosive /ɗ/ and the fricative /s/ do not contrast in register and are included for comparison.

There are also systematic register differences in F2 after plain stops (Figure 10). Low register vowels have a higher F2 over their first 50 ms (RegisterLow: β = 154.073 Hz, t = 5.054, p = 0.001, see Table 10 in Appendix II). Register differences in F2 appear negligible in sonorants, and aspirates, fricative /s/ and implosive /ɗ/ mostly pattern with high register stops.

Normalized F2 of the first 200 ms of vowels following various types of onsets. Thick lines represent means, thin lines individual observations. Aspirates /tʰ, kʰ/, the implosive /ɗ/ and the fricative /s/ do not contrast in register and are included for comparison.

2.2.3 Production weights

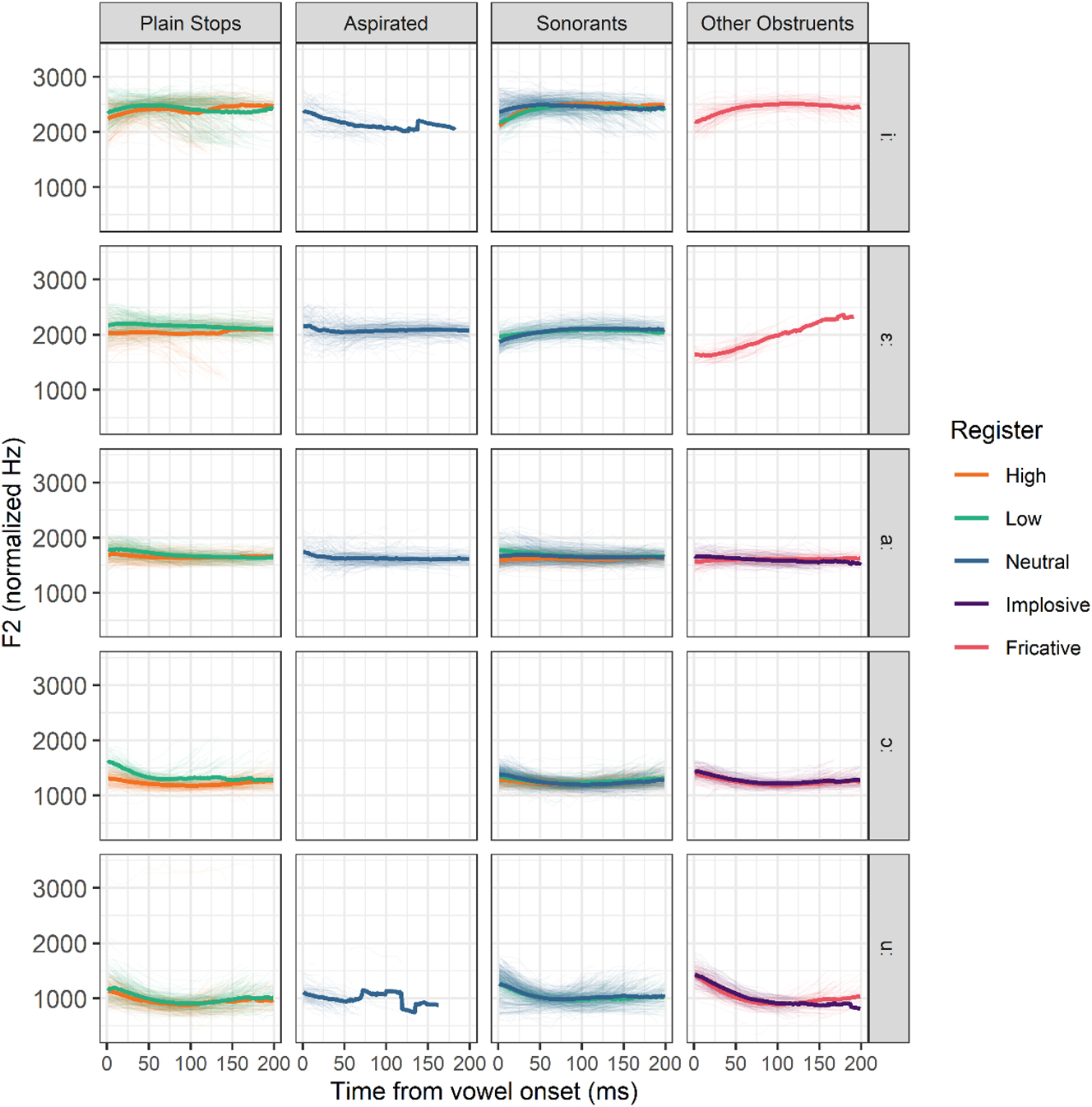

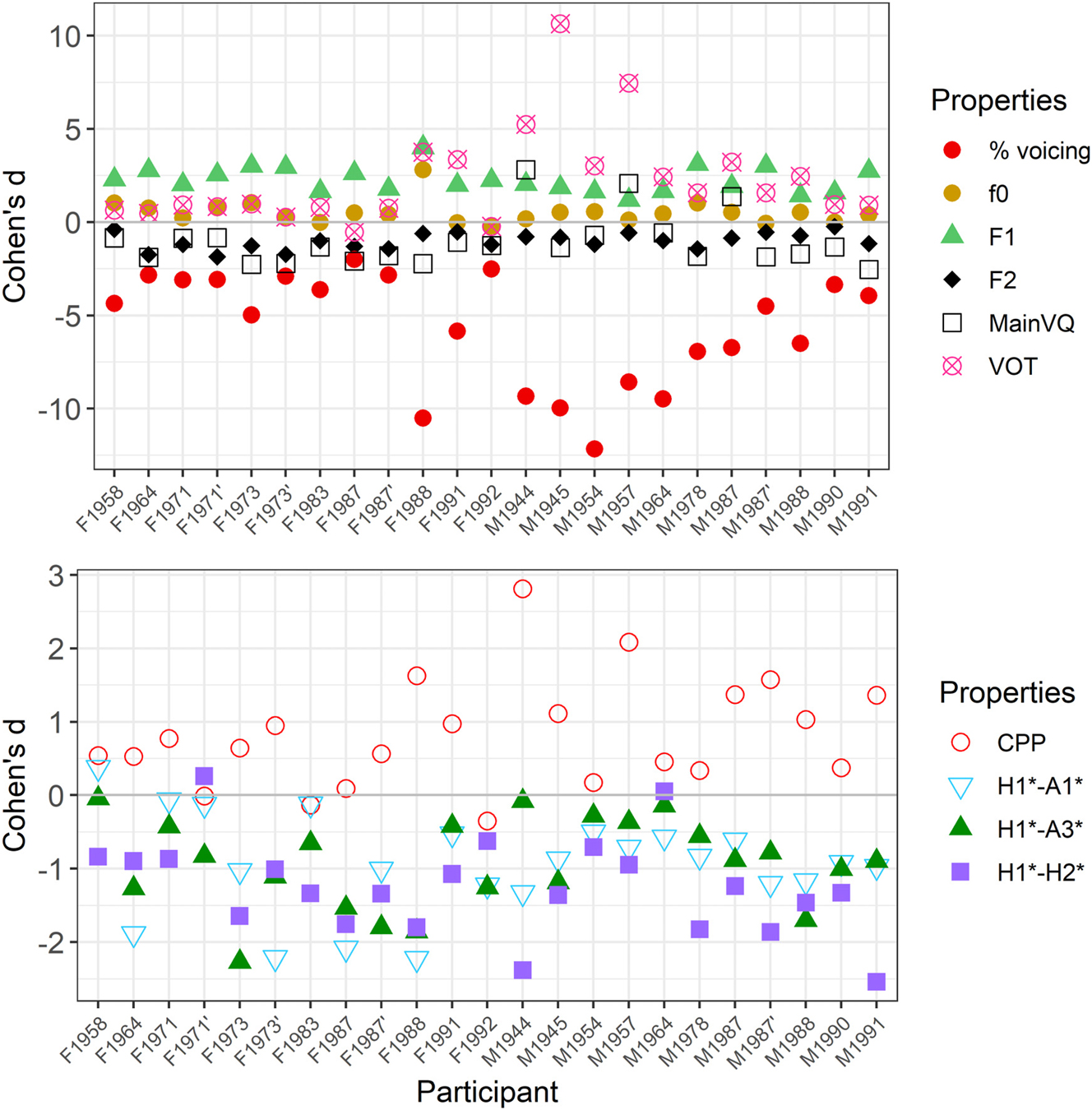

The aggregated results presented above conceal a certain amount of interspeaker variation. Figure 11 therefore provides individual cue weights for each acoustic property after plain stops. As can be seen in the top panel, onset voicing is still a crucial phonetic property in Mnong Râlâm. The heaviest cue is either VOT or the proportion of closure voicing (duration of the voiced closure/total closure duration) in all participants except F1987. However, women have much weaker voicing contrasts than men, especially older ones. Moreover, while there is still a robust voicing contrast in all speakers, register properties have non-negligible weights. F1 is the strongest register cue overall, but most speakers also have large weights for F2 and voice quality. The role of f0 seems much more limited, its weight gravitating around 0.

Cohen’s d’s of each acoustic property associated with voicing and register. Top panel: all properties, with MainVQ indicating the Cohen’s d’s of the strongest voice quality property of each speaker. Bottom panel: detailed Cohen’s d’s of the four measured voice quality properties. Speakers are organized by sex (F/M) and year of birth.

Closing in on voice quality cues, in the bottom panel of Figure 11, we see that there is important interspeaker variation as to what cue has the heaviest weight. H1*-H2* is an important voice quality cue for most speakers but is especially robust in younger speakers. CPP also plays a role, especially in men, while H1*-A1* is stronger in women (H1*-A3* is similar to H1*-A1* but a bit weaker in most speakers). As medial surface thickness of the vocal folds and resting glottal opening are modeled to be good predictors of spectral noise and spectral slope measures (Zhang 2016) and are correlated with sex (Hanson 1995; Patel et al. 2012; Yamauchi et al. 2014), anatomical differences between genders are likely to play a role in some of this variation. However, in the absence of research linking actual laryngeal production with spectral measures, the exact mechanisms involved remain speculative. In any case, Figure 11 shows that the mixed models of the previous section, that are based on aggregated data, slightly underestimate the role of voice quality modulations in the register contrast.

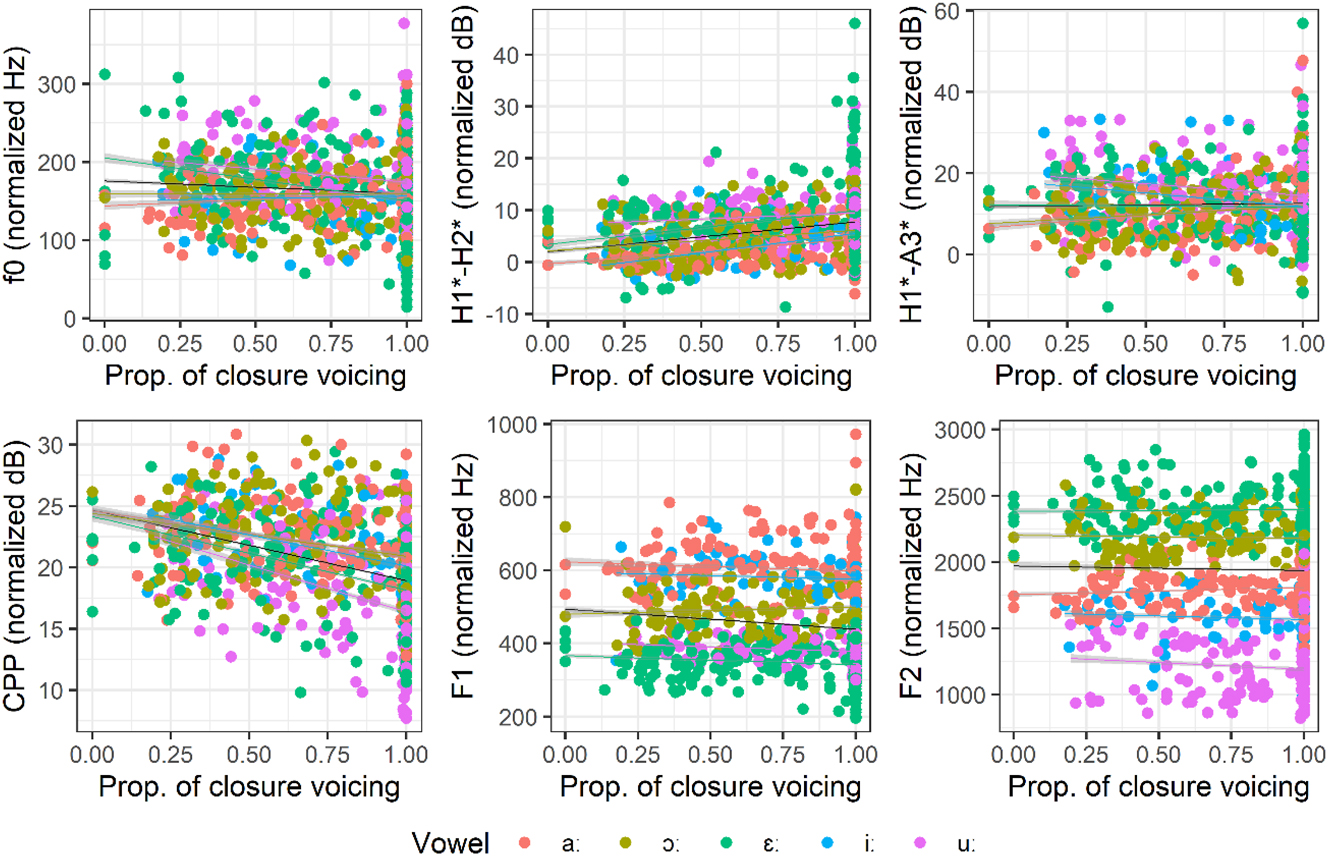

2.2.4 Trade-off between closure voicing and acoustic properties of register

As the results above show that voicing and register are largely redundant in Râlâm, it is important to determine if they are correlated and in what direction. In Figure 12, the main acoustic properties of register are plotted as a function of the proportion of closure voicing in individual voiced stops. When pooling all vowels together, there is no meaningful correlation between the proportion of voicing and H1*-A3* and F2, but the other four indicators show significant correlations. Effects are rather small and vary a bit by vowel, but overall, a larger proportion of closure voicing is associated with acoustic properties characteristic of the low register (a lower f0, a higher H1*-H2*, a lower CPP and a lower F1). This indicates that robust closure voicing co-occurs with salient low register properties. As such, there is no trade-off between closure voicing and register in Mnong Râlâm. Register does not replace voicing; rather, robust voicing is accompanied by robust register cues.

Acoustic properties of register after phonologically voiced stops, averaged over the first 10 ms of vowels. Black regression line represents correlations for all vowels, while colored regression lines show correlations by vowel.

2.2.5 Summary of acoustic results

The results presented above portray a language in which plain voiced stops show significant signs of devoicing but in which full devoicing is still rare. In fact, closure voicing appears to be the dominant cue distinguishing the two stop series in all but one speaker (F1987). However, despite this limited devoicing, there is clear evidence of registral developments. Register is mostly realized through formant differences, with F1 weighing much more than F2: vowel onsets are higher and more fronted after voiced than voiceless stops, resulting in moderate ongliding. This ongliding appears slightly greater in open and mid vowels than in close ones, but is not as dramatic as in other register languages. Impressionistically, it is audible in low register /aː/ (which is realized as [εaː]) but is more discrete in other vowels.

Other acoustic properties show more subtle patterns. Voice quality differences are not negligible, but individual variation makes them appear less significant than they actually are in the statistical models of §2.2.2 because the cues that best reflect them vary across speakers. CPP is more important in men, while H1*-A1* and H1*-A3* weigh more in women. H1*-H2* differences, on the other hand, seem to be age-dependent and are more robust in younger than older speakers. Finally, f0 is lower after voiced velar stops than voiceless velar stops, but there is no significant difference after dental stops.

Registral differences after other onsets were not tested statistically but there is limited evidence for register spreading through sonorants. Measures made in vowels following aspirates, the fricative /s/ and the implosive /ɗ/ confirm that they have particular laryngeal settings. Aspirates and /s/ are produced with a wider glottis than plain stops and sonorants, resulting in a breathier voice quality, while /ɗ/ is produced with slightly tighter glottis than high register stops.

3 Perception experiment

An identification experiment was conducted in the communal house of the hamlet of Buôn Dơng, about 200 m from the venue of the production study, in July 2022. The goal of the experiment was to test which of the naturally occurring acoustic cues uncovered in the previous section play the greatest role in the perception of voicing/register in Mnong Râlâm by asking a diverse group of listeners to identify stimuli varying along continua of voicing, F1, F2 and voice quality, the properties that had the greatest weights in the production experiment.

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Stimuli

Stimuli were synthesized with Klattgrid synthesis implemented in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2010). Two minimal pairs were synthesized: /taː/ ‘at’ ∼ /daː/ ‘wild duck’ and /tuː/ ‘tomb’ ∼ /duː/ ‘to return’. As the production results showed largely redundant voicing and register, /d/ will be used to refer to the low register plain voiced stop in the rest of this section, without presuming of the perceptual weight of the various properties.

We manipulated the acoustic parameters that had the heaviest weights in the acoustic study: voice quality, F1, F2 and voicing. We did not manipulate f0, as it is not significant in dental stops and as adding a fifth synthesized acoustic property would have made the experiment too long. Stimuli were synthesized with a middle-aged male voice and were based on the natural productions of a male speaker born in 1987. Practically, this means that formant targets are lower than the averages presented in §2.2.2 and that we prioritized H1*-H2* and CPP as voice quality cues, as they have the heaviest production weights in younger men. Vowel duration was set to 300 ms. Three-step continua were generated for each property using the following parameters:

Voicing. Three laryngeal settings were generated: (1) a stop with full closure voicing (70 ms), (2) a voiced stop with a voiceless release: voicing over the first 40 ms of its closure, 30 ms of voicelessness at the end of the closure and 10 ms of aspiration after the release, and (3) a stop with a 70 ms voiceless closure and 10 ms of aspiration after the release.

Voice quality. Voice quality was manipulated by varying the open phase of the glottal waveform (or open quotient, OQ, in Klattgrid), a parameter that affects spectral tilt. At vowel onset, the breathy step had an OQ of 0.58, the middle step had an OQ of 0.5 and the modal step had an OQ of 0.43. All 3 synthesized steps then reached an OQ target of 0.5 at 150 ms. Since the Mnong Râlâm low register is not very breathy, it was not necessary to boost the breathiness of low register stimuli by adding breathiness amplitude, contrary to what was done in identification studies conducted on other languages by the same team (Brunelle et al. 2020, 2024]; Tạ et al. 2019).

F1. For /aː/, targets at vowel onset were 500, 625 and 700 Hz. All /aː/ stimuli then reached 700 Hz at 150 ms and gradually dropped to 650 Hz at vowel end. For /uː/, targets at vowel onset were 400, 450 and 500 Hz. All /uː/ stimuli then dropped to 375 Hz at 150 ms and remained stable until vowel end.

F2. For /aː/, targets at vowel onset were 1,400, 1,450 and 1,500 Hz. All /aː/ stimuli then reached 1,450 Hz at 150 ms and gradually dropped to 1,400 Hz at vowel end. For /uː/, targets at vowel onset were 1,200, 1,275 and 1,350 Hz. All /uː/ stimuli then dropped to 950 Hz at 150 ms and remained stable until vowel end.

f0. Pitch did not vary across stimuli. It started at 120 Hz and dropped linearly to 110 Hz at vowel end in all syllables.

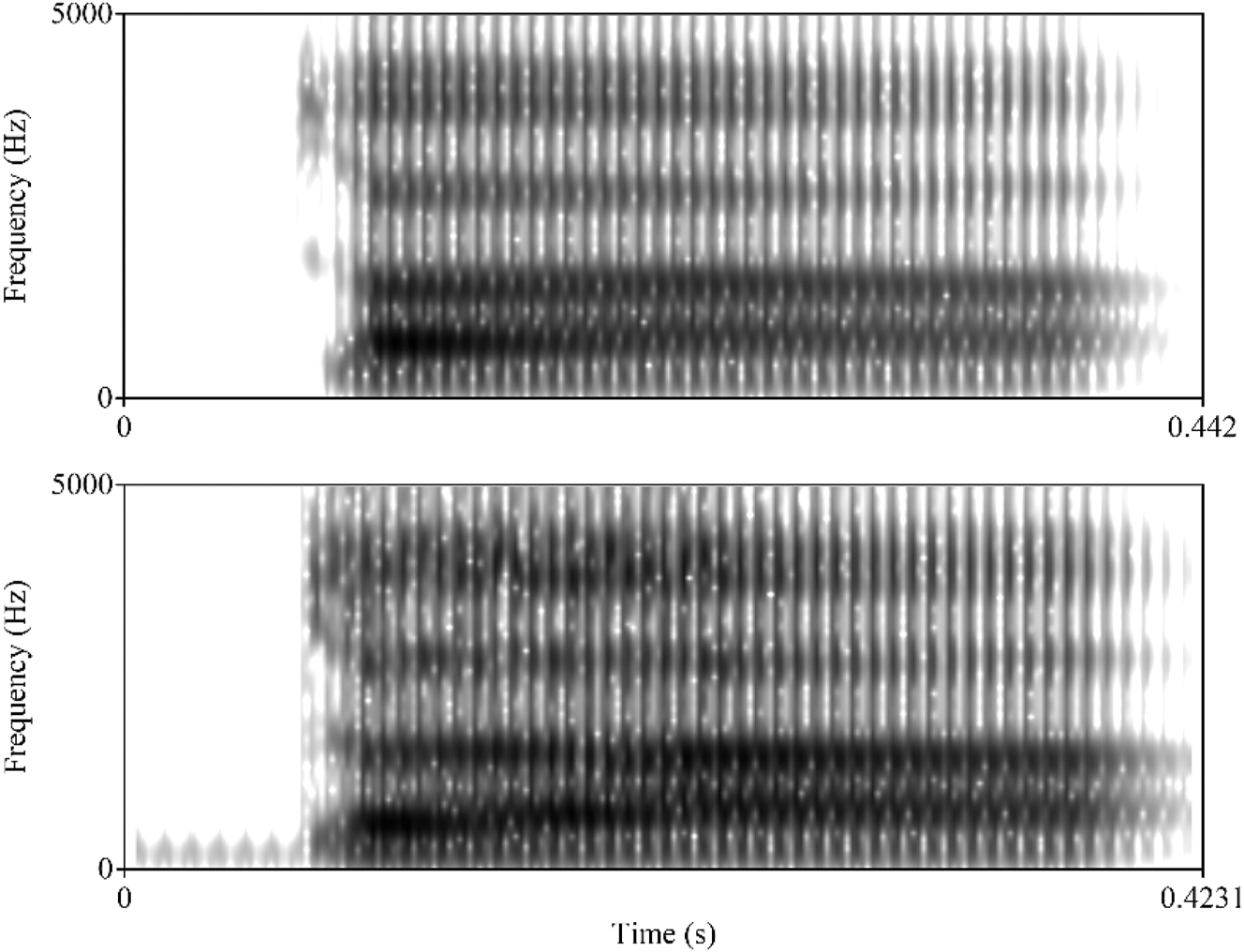

All possible combinations of these acoustic values were synthesized, yielding 81 stimuli (3 voicing steps X 3 voice quality steps X 3 F1 steps X 3 F2 steps). Spectrograms of stimuli representing high register /taː/ and low register /daː/ are given in Figure 13. The reliability of the synthesis parameters was checked by measuring the stimuli with PraatSauce (Kirby 2018). The distribution of the stimuli along the most relevant acoustic dimensions is given in Figure 14.

Spectrograms of sample stimuli. Top: Stimulus mirroring natural productions of high register /taː/ (targets at vowel onset: OQ 0.43, F1 700 Hz, F2 1,400 Hz). Bottom: Stimulus mirroring natural productions of low register /daː/ with voicing (targets at vowel onset: OQ 0.58, F1 550 Hz, F2 1,500 Hz).

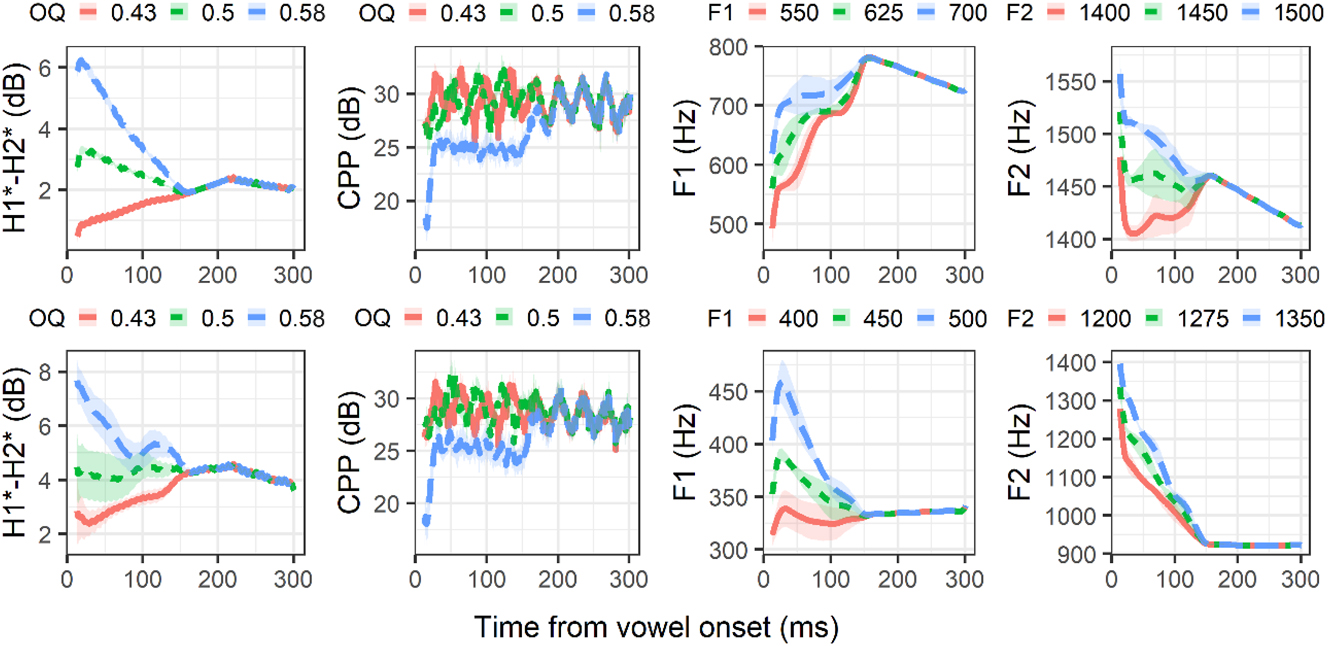

Mean values of the acoustic parameters manipulated in the stimuli used for the identification experiment. Top panel: /taː∼daː/. Bottom panel /tuː∼duː/. The ribbons show one standard deviation above and below the mean.

3.1.2 Participants and procedure

A total of 53 participants took part in the identification experiment (32 women, 21 men). They were all born between 1944 and 2003. None of the participants reported hearing problems, and none were obvious to the experimenters (even if it can be assumed that older listeners have normal aged-related hearing loss). Besides Mnong, all listeners spoke Vietnamese and 33 spoke Rade with variable fluency. They were all born in the district of Yang Tao, except one male participant who was born in the neighboring city of Buôn Ma Thuột. Eight of them had lived in other regions of Vietnam for more than a few months (Buôn Ma Thuột, Tây Ninh, Bình Dương, Hồ Chí Minh City). Three female participants were excluded because they were not able to complete the experiment. Out of the 50 listeners, 18 had participated in the production experiment three years earlier.

The procedure took place in a community house where up to three participants completed the task simultaneously. The experiment was conducted in OpenSesame on Mac or PC laptops and sounds were played through Sennheiser 280D PRO headphones. Participants had to listen to stimuli and to identify them by pressing one of two keyboard buttons associated with images representing response choices. There were three training phases: one with three repetitions of the two stimuli most closely mirroring natural productions (with feedback), one with five repetitions of the same two near-natural stimuli (without feedback), and one with ten random stimuli. Training responses are not reported here. Participants then had to identify each set of eighty-one stimuli three times, in alternating blocks. As few participants could read Mnong, visual instructions accompanied by Vietnamese text were provided.

3.1.3 Analysis

Mixed logistic regressions were used to analyze the identification results, by syllable. The dependent variable was the response provided by participants. The fixed effects were the types of voicing (negative, voiceless release and voiceless) as well as voice quality (OQ), F1 and F2 steps. Random slopes for each main effect by participant were also included. Models were simplified using the same top-down approach as in §2.1.3: interactions were dropped one by one, starting with that with the lowest F-value, as long as the resulting models had a lower Akaike information criterion (AIC) score than the previous model, or a higher or equal but not significantly different AIC.

3.2 Results

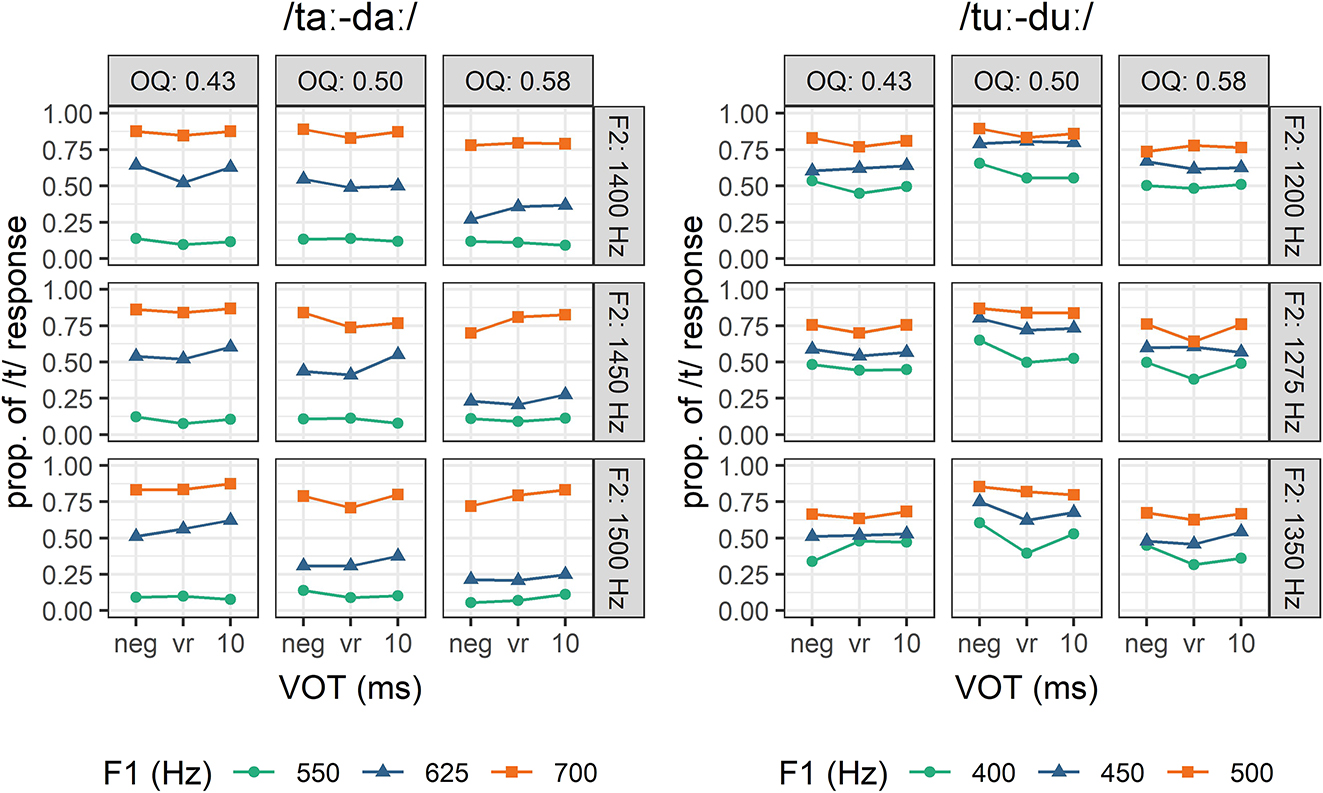

The proportion of /t/ (or high register) responses given by all participants is aggregated in Figure 15. The only obvious result is that tokens with a higher F1 are more associated with the high register, but that this effect is much stronger in /aː/ than /uː/ stimuli, reflecting the larger F1 difference between registers in open than close vowels in the production results and in the stimuli. Response patterns conditioned by F2, voice quality and voicing are visible in specific boxes, but since they are not as salient, they are explored statistically below.

Proportion of high register/voiceless responses (/t/) for each type of stimulus, by F1, voicing (neg: fully voiced, vr: voiceless release, 10: voiceless with short lag VOT), OQ (voice quality) and F2, for all listeners. Left panel: /aː/ stimuli. Right panel: /uː/ stimuli.

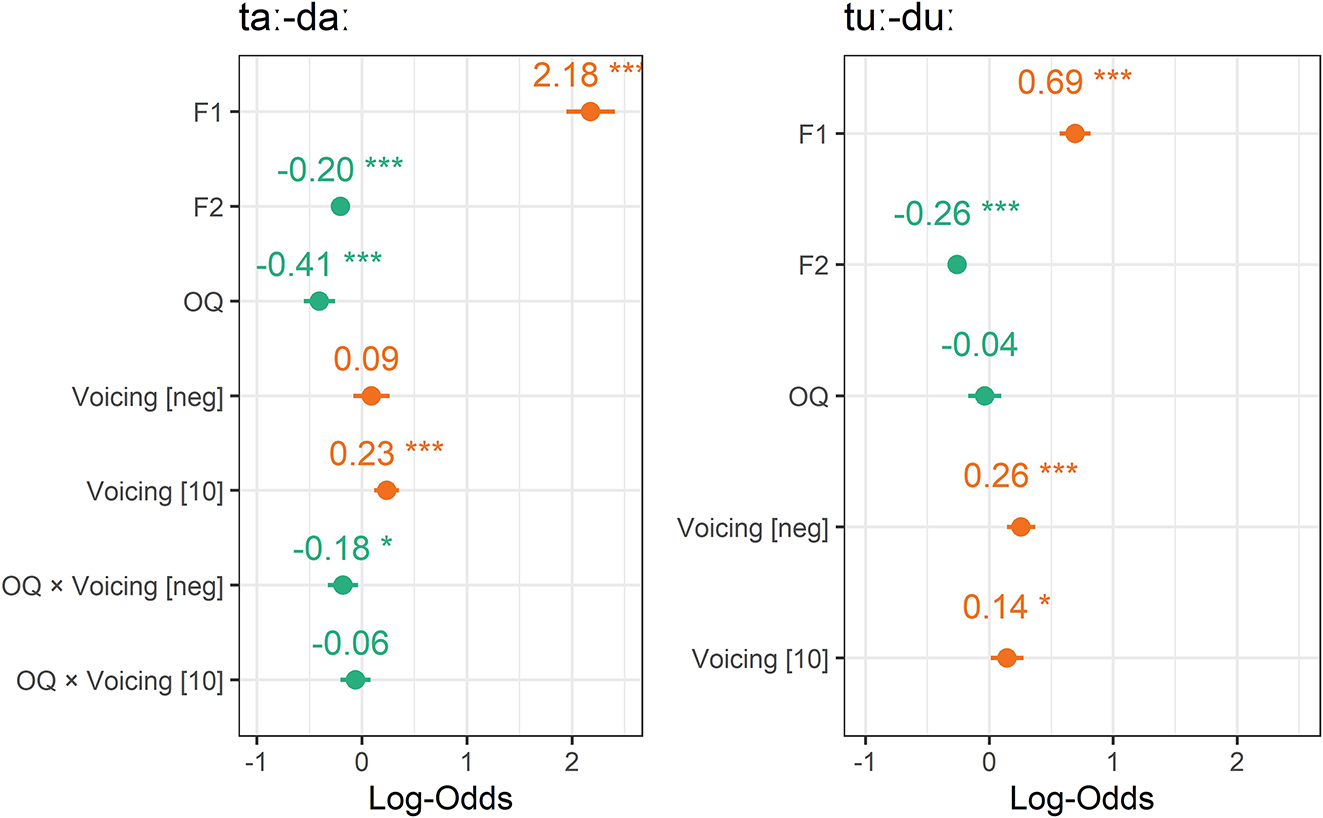

The results of the logistic regressions are graphically represented in Figure 16 (full models are reported in Tables 11 and 12, Appendix III). They confirm that a higher F1 increases the proportion of high register responses and that this effect is greater in /aː/ than /uː/. F2 also significantly affects responses: stimuli with a higher F2 are more associated with the low register but this effect is weaker than that of F1. Unexpectedly, voice quality (OQ) is an important factor in stimuli with /aː/ but does not play a role in /uː/, despite the similar OQ values used for the two sets of stimuli (they have similar H1*-H2* and CPP measures, as can be checked in Figure 14). A greater open quotient, resulting in a breathier/laxer vowel, is associated to the low register in /aː/ but has no effect in /uː/. Turning to voicing, voiceless stimuli (Voicing[10]) have more chances of being associated with the high register than stimuli with a voiceless release in both /aː/ and /uː/ stimuli, but tokens with a fully voiced closure are unexpectedly more associated with the high register than tokens with a voiceless release when the vowel is /uː/. There is also a weak interaction of voice quality (OQ) and voicing in /aː/ stimuli: when a stimulus is fully voiced, an increase in breathiness tends to be even more associated with the low register than when it has a voiceless release.

Coefficients and statistical significance of independent variables in logistic regression models conducted on the responses for /aː/ stimuli (left) and /uː/ stimuli (right). Orange coefficients indicate that an increase in a factor biases responses towards high register responses. Green coefficients indicate that an increase in a factor biases responses towards the low register. Full model summaries are provided in Tables 11 and 12, Appendix III.

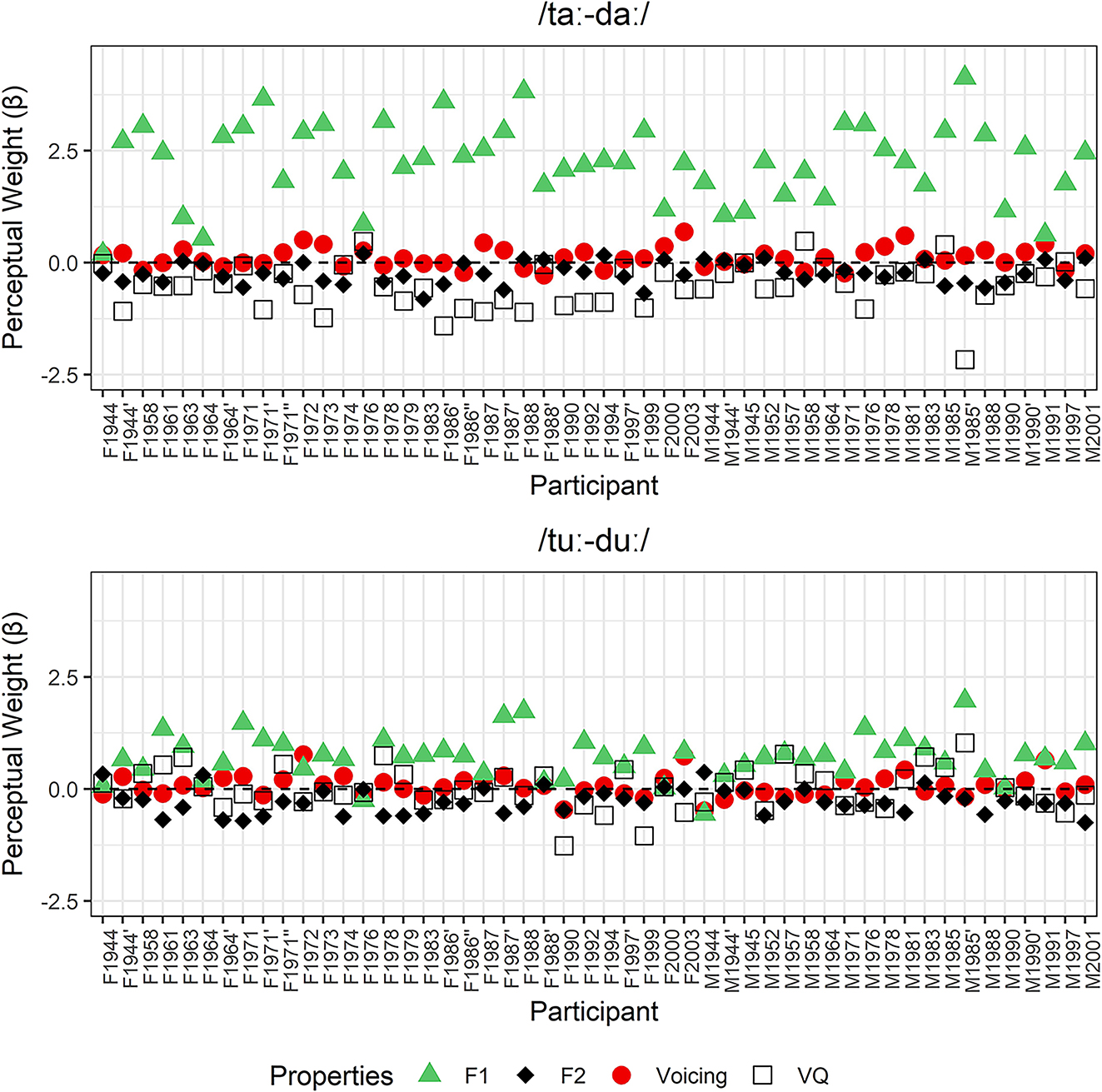

We saw in §2 that there is non-negligible individual variation in the acoustic realization of voicing and register in Mnong Râlâm. Could the same type of variation be found in identification responses? This was assessed by fitting logistic regressions on individual speakers’ responses and by using their log-odds estimates as an indicator of perceptual weight. These regressions include no interactions and no random effects because there are only 243 observations per syllable (3 repetitions of each of the 81 stimuli). As such, they are not as reliable as the aggregated models presented in Figures 15 and 16. Moreover, Voicing was coded as a continuous numerical variable (negative VOT = 0; voiceless release = 1, 10 ms VOT = 2) rather than a categorical factor in order to obtain a single variable estimate.

Individual perceptual weights are reported in Figure 17. There is significant individual variation, but contrary to production weights, there is no evidence for structured age or gender patterns in the identification tasks. Almost all participants primarily made use of F1 for identification, with higher log-odds in /aː/ stimuli than /uː/ ones. Voice quality (OQ) played a more limited role in most speakers in /aː/ stimuli but was negligible in /uː/ ones. When looking at individual data rather than aggregated data, F2 and Voicing had consistently low weights.

Log-odd estimates of each perceptual property by dialect and speaker. Top panel: /a/ stimuli. Bottom panel: /u/ stimuli.

These results confirm that F1 is the primary perceptual property of the Mnong Râlâm voicing/register contrast across speakers. The absence of socially structured variation in perception weights rules out the possibility of a correlation between production and perception cues. Despite variation in the production cue weights, all listeners primarily rely on F1 for identification. Voicing and F2 play significant but more limited roles in identification. Finally, despite its equal salience in the two series of stimuli, voice quality is used much more systematically for the identification of /aː/ than /uː/ stimuli.

4 Discussion and conclusion

Our production results confirm that Mnong Râlâm has not yet lost its historical voicing contrast in obstruents. Eleven speakers out of 23 did not produce fully devoiced voiced stops tokens at all, and out of those who did, only three, all women, fully devoiced more than 25 % of tokens. However, partial devoicing is quite prevalent. In women, the most common realization of voicing in voiced stops is the presence of closure voicing followed by a voiceless release (partial devoicing accompanied by a short lag VOT), and these voiceless release stops are also common in younger men. Older men, on the other hand, tend to fully voice their closures, with occasional partial devoicing. The fact that older men have a more categorical closure voicing than other groups could suggest that the community is undergoing a change away from voicing. In this sense, Mnong Râlâm appears more advanced on the devoicing path than Northern Raglai, a Chamic language spoken 150 km away, that maintains quasi-systematic full closure voicing (Brunelle et al. 2022). It is nonetheless more conservative than other languages of the area, like Jarai, Southern Raglai (both Chamic) and closely-related Chrau, in which voiced stops are predominantly devoiced, even if they maintain residual closure voicing as an optional property (Brunelle et al. 2022, 2024], Tạ et al. 2022).

Despite its robustness, Mnong Râlâm obstruent voicing is redundant with a well-developed register system that is largely realized through F1 modulations resulting in a weak ongliding at the beginning of vowels. In the low register, open and mid vowels often start with falling onglides [eεː εaː, oɔː]. In the high register, by contrast, there is a limited falling F1 at the beginning of closed vowels, but it does not result in audible onglides. Similar F1 modulations are found in other register languages of the area, but in a more salient manner (Brunelle et al. 2020, 2022], 2024]; Tạ et al. 2022). Other acoustic properties, like F2 and voice quality, play a real, if more limited role in the register contrast and are again much less salient than in nearby languages (Brunelle et al. 2020, 2022], 2024]; Tạ et al. 2022). As for f0, it is at best a negligible property in the Mnong Râlâm register contrast (especially in dentals), just like in Jarai and Raglai (Brunelle et al. 2022, 2024]), but contrary to Chru and Chrau, in which it plays a significant ancillary role (Brunelle et al. 2020; Tạ et al. 2022). Overall, Mnong Râlâm seems to be a transitional case between languages that preserve a robust voicing contrast and only have limited register cues, like Northern Raglai, and languages with salient register cues and limited residual voicing. As such, its register properties are too salient to be a mere automatic consequence of onset voicing but remain much less salient than those of other register languages of south-central Vietnam.

The identification of the Mnong Râlâm voicing/register contrast is largely based on F1, with F2, voice quality and voicing type operating as secondary properties. That said, there are some perceptual differences between vowels: F1 is more reliable in /aː/ than in /uː/ (which mirrors its greater acoustic salience in low vowels), listeners seem more sensitive to full closure voicing in /uː/ than in /aː/, and voice quality seems perceptually more salient in /aː/ than in /uː/. However, on average, the perceptual weights of cues associated with register are weaker in Mnong Râlâm than in other languages of the area, echoing the overall weaker salience of their production cue weights (Brunelle et al. 2020, 2022], 2024]; Tạ et al. 2022). Considering the production results, the limited perceptual role of closure voicing is surprising, and may indicate that despite its prevalence in production, voicing is already treated by listeners as an inherently unstable cue that shows too much variation across speakers to be fully reliable.

Put together, the acoustic and identification results yield the general picture of a language that preserves closure voicing in reflexes of historical voiced stops, but in which partial devoicing is the dominant pattern and full devoicing is not uncommon. A register system primarily based on ongliding is also found alongside this unstable voicing distinction. While it is less salient than in other Chamic and Austroasiatic languages of the area, it appears to be stable as it does not exhibit structured variation along sex or age groups. The relatively limited salience of the registral properties of Mnong Râlâm is paralleled by the fact that the register contrast has not been generalized to onsets other than plain stops. Register properties only spread to syllables headed by onset sonorants in a superficial coarticulatory manner.

It would be tempting to hypothesize that Mnong Râlâm recently developed a register system to compensate for the instability of closure voicing induced by voiceless releases. However, there is evidence against such a scenario. First, younger participants do not have stronger production or perception cue weights for vowel-based register properties than older participants. The only phonetic property that appears to exhibit an age gradient is closure voicing. This suggests that vowel-based register developed and stabilized before the oldest speakers in our sample were born. What appears to be changing in the community is the relatively rapid erosion of obstruent voicing, that is far more advanced in younger women than in older men. This pattern is similar to what was found in Chru, another language in which register seems to have recently taken over the contrastive load of voicing (Brunelle et al. 2020), but one should keep in mind that even in languages that have full-fledged register systems, men and older speakers tend to exhibit more frequent residual voicing in low register stops (Brunelle et al. 2022, 2024]). A second reason to remain circumspect about the possibility that Mnong Râlâm registrogenesis is recent is the presence of fully formed register systems in most, if not all South Bahnaric languages. Proto-South-Bahnaric has been reconstructed with a voicing contrast (and no register), based on early descriptions of South Bahnaric languages that did not mention the presence of register (Sidwell 2000). However, besides Mnong Râlâm there is now evidence for register in Phong/Bunong (Butler 2010; Butler 2015; Phillips 1962; Phillips 1973; Vogel and Filippi 2006), Stiêng (Bon 2014; Lê 2000; Lê 2015), Tamun (Lê and Phan 2013) and Chrau (Tạ et al. 2022; Trấn 2008). The only remaining variety of South Bahnaric that has never been described as registral is Koho-Srê (Dournes 1950; Manley 1972; Olsen 2014; Olsen 2015), but an elicitation session conducted by the first and third authors with two speakers in Điom A (province of Lâm Đồng, Vietnam) suggests that this may be an oversight. It might therefore be necessary to reconstruct register all the way to Proto-South-Bahnaric. If this is correct, the redundancy between voicing and register could have been a property of Mnong for generations, if not centuries. It is even possible that register is the permanent stable contrastive element while the prevalence of voicing in different age and sex groups varies over time.

For these reasons, Mnong Râlâm may not be a good test case for registrogenetic scenarios: the production of its register could have evolved in significant ways since register first developed. For example, differences originally conditioned by larynx lowering, like F1 and voice quality modulations, could now be realized through lingual articulations or glottal settings very different from the articulations that led to the original registrogenesis. From a synchronic perspective, the acoustic properties of Mnong Râlâm register are compatible with several articulatory strategies proposed in previous literature. The lower F1 in the low register could be accounted for either by a lowering of the larynx or by a raising of the tongue body two gestures resulting in a longer posterior resonator. Anticipation of both of these articulations should also favor closure voicing by increasing the size of the supraglottal cavity and favoring the maintenance of a strong transglottal airflow (Westbury 1983; Westbury and Keating 1986). The higher F2 associated with the low register, though subtle, is more difficult to attribute to larynx lowering and appears easier to explain by direct lingual movement: a fronted tongue would induce a higher F2 and would also result in an anticipatory expansion of the pharyngeal cavity favorable to obstruent voicing. The weak f0 differences between registers likewise militate against an important role of larynx lowering, as the tilt of the angle between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages accompanying this articulation should shorten the vocal folds and result in a lower f0 (Honda et al. 1999). Finally, the voice quality differences between the two registers could be attributed to direct glottal control rather than a more global register articulation.

Even if registrogenesis is not a recent change, and regardless of current articulatory strategies, the simultaneous presence of voicing and register in contemporary Mnong Râlâm suggests that from a historical perspective, registral properties do not arise as a direct consequence of the devoicing of voiced stops but develop (or at least can develop) before the loss of voicing. This is in line with traditional models of (trans)phonologization in which a secondary property of a contrast is exaggerated before the loss of the primary property (Hagège and Haudricourt 1978; Huffman 1976; Hyman 1976).

Regardless of the way in which the current contrast took shape, the relation between closure voicing and register in Mnong Râlâm is likely to be bidirectional. On the one hand, it is long-established that obstruent voicing lowers f0 and raises F1 in most languages (House and Fairbanks 1953; Rousselot 1901–1908). Mainland Southeast Asian languages in which these effects are attested in the absence of tone or register contrasts include Northern Raglai and Ban Hin Tum Eastern Khmu (Brunelle et al. 2022; Maspong 2023). On the other hand, the light perceptual weight of voicing and its individual variability in production suggest that register now bears most of the burden of contrast in Mnong Râlâm, and that despite its prevalence, voicing has become a secondary property even in the phonetic sense. In the absence of a gesture actively preventing voicing in stops (such as glottal opening or tensing of the vocal folds), hyperarticulation of register may very well favor closure voicing, as many of the articulatory gestures susceptible be involved in register production increase the volume of the supraglottal cavity and boost transglottal airflow. The correlation between the proportion of closure voicing and the acoustic indicators associated with the low register in §2.2.4 could therefore be explained as an effect of register production on closure voicing rather than the opposite. In the end, register and voicing should probably be conceived, diachronically and synchronically, as highly compatible and non-mutually exclusive properties that share both articulatory and phonological properties. Articulatory research on the production of register and a better comprehension of the relation between voicing and voice quality are needed for these hypotheses to be tested.

Funding source: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

Award Identifier / Grant number: 435-2017-0498 and 435-2022-0047

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Provincial authorities of Đắk Lắk province for granting us research authorizations, as well as the district authorities of the Lăk district for facilitating our research. Special thanks to H Hê Bkrông and H Wăn Du for helping us with recruitment and local logistics. This work would not have been possible without them. We are also indebted to all our participants for their patience and willingness to take part in our experiments. We acknowledge the contributions of Sabrina McCullough, Sue-Ann Richer and Jeanne Brown, who annotated and processed the acoustic recordings.

-

Research ethics: This research was approved by the Office of Research Ethics and Integrity of the University of Ottawa, file # S-02-23-8921.

-

Author contributions: Marc Brunelle is primarily responsible for the design of the experimental protocol, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work and the write-up. Đinh Lư Giang contributed to the design of the experiment, the acquisition of the data and obtained fieldwork authorizations. Tạ Thành Tấn contributed to the design of the perception experiment and the acquisition of the perception data.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Research funding: This project was funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100000155, grants 435-2017-0498 and 435-2022-0047).

Appendix I: Mnong wordlist

| Mnong | English | Vietnamese |

|---|---|---|

| tiː | hand, arm | tay |

| tɛː (waːc) | k.o. small bird | loại chim nhỏ |

| taː (ti:) | to teach someone | dạy bảo |

| tɔː | to show | chỉ |

| tuː | grave | mộ mả |

| thɛː | to supply, to distribute | phân phối, cung cấp |

| thaː | to release | thả rông |

| (daʔ) diː | if | nếu |

| diːr | to avoid | tránh |

| dɛː | female 3 p.s. pronoun | cô ấy, em ấy, chị ấy |

| adaː | goose | vịt xiêm |

| dɔː | budding (corn, banana) | hoa chuối, bắp non |

| duː | to go back | về |

| ɗaːl | to meet | gặp |

| (na:r) ɗɔː | yesterday | hôm qua |

| ɗuːŋ | coconut | dừa |

| siː | iron | sắt |

| sɛːj | rope, string | dây |

| saː | to eat | ăn |

| sɔː | grandchild | cháu |

| suː | blankets | chăn |

| (nah) niːn | to tease, to joke | chọc, nói đùa |

| nɛː | pestle | chày |

| naː | bow | cung |

| nɔː | rice straw | rơm lúa |

| təmnuː | thigh (of animal) | bắp đùi |

| liː (la:j) | well-behaved, not fussy | ngoan |

| lɛː | to wake someone up | đánh thức |

| laː | kidney | thận |

| lɔː | meat | thịt |

| (liː) luː | unclear (idea, memory) | mờ mờ |

| plɔː | numb and sore (hands and legs) | đau tay chân vì làm việc nhiều |

| blɔː | mute, dumb | câm |

| riː raː | bushy | um tùm |

| grɛː | to imitate, to follow | theo, bắt chước |

| ʔara | duck | vịt cỏ |

| rɔː | dry | khô |

| (ɟe:) ruː | already, completive particle | (đã) rồi |

| praː | to try | thử |

| prɔː | six | sáu |

| briː | fields around village or forest | ruộng, rừng, rẫy |

| ɟraː | to kick | đạp chân |

| brɔː | to trade | đi buôn |

| ɟruː | deep | sâu |

| kiːl | difficult, hard | khó |

| kɛː | flea (buffalo or cow) | con ve hút máu trâu |

| kaː | fish | cá |

| kɔː | neck | cổ |

| (peh) kuː | sickle | loại lưỡi hái còng |

| khɛː | month, moon | tháng, mặt trăng |

| khiːr khaːr | arid, deserted | khô càn |

| khuːŋ ŋat | k.o. spirit | linh hồn, ma |

| giː gwa: | crooked (legs) | (chân) không thẳng |

| gɛː | thin | gấy |

| gaːr | Mnong Gar clan | M’nông Gar |

| maː guː | stupid | ngu ngốc |

| riː ŋiː | silent | im lặng |

| ŋaː | to lose | mất |

| ŋɔː | dark | tối |

| ŋuːl | area | khu vực |

Appendix II: Linear mixed models

Table of estimates for mixed model on VOT in Mnong plain stops with positive VOT. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 13.078 | 1.391 | 8.584 | 9.403 | 0.000 |

| VoicingVoiced | −1.148 | 1.392 | 5.024 | −0.825 | 0.447 |

| Vowelεː | −0.357 | 1.675 | 4.682 | −0.213 | 0.840 |

| Voweliː | −2.821 | 1.650 | 4.587 | −1.710 | 0.153 |

| Vowelɔː | −2.906 | 1.777 | 4.358 | −1.635 | 0.171 |

| Voweluː | −2.081 | 1.659 | 4.496 | −1.254 | 0.271 |

| PlaceVelar | 5.497 | 1.384 | 4.868 | 3.972 | 0.011 |

| VoicingVoiced:Vowelεː | 3.460 | 1.956 | 4.902 | 1.769 | 0.138 |

| VoicingVoiced:Voweliː | 5.389 | 1.912 | 5.157 | 2.818 | 0.036 |

| VoicingVoiced:Vowelɔː | 3.565 | 2.382 | 4.796 | 1.496 | 0.197 |

| VoicingVoiced:Voweluː | 3.197 | 1.971 | 5.049 | 1.622 | 0.165 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelεː | 0.664 | 1.953 | 4.844 | 0.340 | 0.748 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweliː | 3.523 | 1.934 | 5.267 | 1.822 | 0.125 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelɔː | 5.771 | 2.341 | 4.459 | 2.465 | 0.063 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweluː | 4.249 | 1.966 | 4.937 | 2.162 | 0.084 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized f0 over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 165.850 | 8.588 | 6.754 | 19.313 | 0.000 |

| RegisterLow | −9.628 | 10.609 | 4.003 | −0.908 | 0.415 |

| Voweliː | 48.658 | 10.026 | 3.972 | 4.853 | 0.008 |

| Vowelaː | −32.789 | 10.074 | 3.972 | −3.255 | 0.032 |

| Vowelɛː | −18.017 | 10.324 | 4.371 | −1.745 | 0.150 |

| Voweluː | 15.201 | 10.118 | 4.042 | 1.502 | 0.207 |

| PlaceVelar | 7.334 | 10.620 | 4.020 | 0.691 | 0.528 |

| RegisterLow:Voweliː | −25.625 | 13.035 | 3.963 | −1.966 | 0.121 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelaː | 36.652 | 13.478 | 3.969 | 2.719 | 0.053 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelɛː | 28.232 | 13.585 | 4.094 | 2.078 | 0.105 |

| RegisterLow:Voweluː | 26.791 | 13.491 | 3.984 | 1.986 | 0.118 |

| RegisterLow:Placevelar | −53.992 | 7.369 | 3.996 | −7.327 | 0.002 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweliː | −1.108 | 13.343 | 3.981 | −0.083 | 0.938 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelaː | 39.984 | 13.504 | 4.000 | 2.961 | 0.042 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelɛː | 32.868 | 13.584 | 4.094 | 2.420 | 0.071 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweluː | 10.754 | 13.508 | 4.006 | 0.796 | 0.471 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized H1*-H2* over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.697 | 0.925 | 12.236 | 0.753 | 0.466 |

| RegisterLow | 2.772 | 1.432 | 9.046 | 1.936 | 0.085 |

| Voweliː | 1.259 | 1.148 | 9.016 | 1.097 | 0.301 |

| Vowelaː | −0.149 | 1.150 | 9.077 | −0.130 | 0.900 |

| Vowelɛː | −1.127 | 1.156 | 9.277 | −0.975 | 0.354 |

| Voweluː | 2.141 | 1.149 | 9.056 | 1.864 | 0.095 |

| PlaceVelar | 1.444 | 0.532 | 9.075 | 2.713 | 0.024 |

| RegisterLow:Voweliː | 3.159 | 1.762 | 9.011 | 1.793 | 0.106 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelaː | −0.747 | 1.835 | 9.036 | −0.407 | 0.693 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelɛː | 1.705 | 1.838 | 9.096 | 0.928 | 0.377 |

| RegisterLow:Voweluː | 2.742 | 1.835 | 9.041 | 1.494 | 0.169 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized H1*-A1* over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 12.961 | 1.215 | 4.376 | 10.669 | 0.000 |

| RegisterLow | 1.507 | 1.689 | 4.092 | 0.892 | 0.422 |

| Voweliː | −6.047 | 1.583 | 3.927 | −3.820 | 0.019 |

| Vowelaː | −2.763 | 1.590 | 3.918 | −1.738 | 0.159 |

| Vowelɛː | −8.696 | 1.624 | 4.269 | −5.354 | 0.005 |

| Voweluː | −4.253 | 1.606 | 4.084 | −2.648 | 0.056 |

| PlaceVelar | −0.220 | 1.676 | 3.965 | −0.132 | 0.902 |

| RegisterLow:Voweliː | 4.130 | 2.075 | 4.044 | 1.991 | 0.117 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelaː | 2.041 | 2.149 | 4.076 | 0.950 | 0.395 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelɛː | 4.733 | 2.166 | 4.211 | 2.185 | 0.091 |

| RegisterLow:Voweluː | 4.156 | 2.149 | 4.084 | 1.934 | 0.124 |

| RegisterLow:PlaceVelar | −2.369 | 1.183 | 4.211 | −2.004 | 0.112 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweliː | 0.632 | 2.113 | 3.981 | 0.299 | 0.780 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelaː | −1.619 | 2.142 | 4.029 | −0.756 | 0.492 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelɛː | 2.753 | 2.155 | 4.127 | 1.277 | 0.269 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweluː | 1.578 | 2.140 | 4.013 | 0.737 | 0.502 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized H1*-A3* over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 7.798 | 1.003 | 12.258 | 7.773 | 0.000 |

| RegisterLow | 6.095 | 1.529 | 8.635 | 3.986 | 0.003 |

| Voweliː | −1.681 | 1.222 | 8.498 | −1.376 | 0.204 |

| Vowelaː | −1.960 | 1.230 | 8.712 | −1.594 | 0.147 |

| Vowelɛː | −1.566 | 1.250 | 9.262 | −1.253 | 0.241 |

| Voweluː | −0.531 | 1.226 | 8.605 | −0.433 | 0.676 |

| PlaceVelar | 1.349 | 0.572 | 8.893 | 2.358 | 0.043 |

| RegisterLow:Voweliː | −0.841 | 1.880 | 8.561 | −0.448 | 0.666 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelaː | −1.677 | 1.960 | 8.630 | −0.855 | 0.415 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelɛː | −2.625 | 1.972 | 8.825 | −1.331 | 0.216 |

| RegisterLow:Voweluː | 2.179 | 1.960 | 8.610 | 1.112 | 0.296 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized CPP over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 23.353 | 0.631 | 5.934 | 37.003 | 0.000 |

| RegisterLow | −1.826 | 0.800 | 3.880 | −2.282 | 0.087 |

| Voweliː | 0.035 | 0.756 | 3.843 | 0.047 | 0.965 |

| Vowelaː | −0.422 | 0.760 | 3.862 | −0.555 | 0.610 |

| Vowelɛː | −0.664 | 0.776 | 4.178 | −0.857 | 0.438 |

| Voweluː | −1.117 | 0.759 | 3.840 | −1.471 | 0.218 |

| PlaceVelar | −0.196 | 0.797 | 3.831 | −0.246 | 0.818 |

| RegisterLow:Voweliː | −1.020 | 0.986 | 3.883 | −1.035 | 0.361 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelaː | 1.580 | 1.019 | 3.887 | 1.551 | 0.198 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelɛː | 1.673 | 1.026 | 3.997 | 1.631 | 0.178 |

| RegisterLow:Voweluː | 0.054 | 1.019 | 3.882 | 0.053 | 0.960 |

| RegisterLow:PlaceVelar | −2.418 | 0.559 | 3.965 | −4.327 | 0.013 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweliː | −0.615 | 1.006 | 3.860 | −0.611 | 0.575 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelaː | 0.822 | 1.017 | 3.856 | 0.809 | 0.466 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelɛː | 1.271 | 1.024 | 3.960 | 1.241 | 0.283 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweluː | −2.365 | 1.017 | 3.853 | −2.326 | 0.083 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized F1 over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 805.542 | 52.113 | 4.077 | 15.457 | 0.000 |

| RegisterLow | −222.563 | 73.314 | 3.993 | −3.036 | 0.039 |

| Voweliː | −333.900 | 69.383 | 3.985 | −4.812 | 0.009 |

| Vowelaː | −27.567 | 69.714 | 3.984 | −0.395 | 0.713 |

| Vowelɛː | −259.938 | 69.783 | 4.000 | −3.725 | 0.020 |

| Voweluː | −349.426 | 69.736 | 3.989 | −5.011 | 0.007 |

| Placevelar | −102.536 | 73.274 | 3.984 | −1.399 | 0.235 |

| RegisterLow:Voweliː | 134.852 | 90.297 | 3.991 | 1.493 | 0.210 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelaː | 69.187 | 93.329 | 3.992 | 0.741 | 0.500 |

| RegisterLow:Vowelɛː | 152.944 | 93.361 | 3.998 | 1.638 | 0.177 |

| RegisterLow:Voweluː | 182.811 | 93.332 | 3.993 | 1.959 | 0.122 |

| RegisterLow:PlaceVelar | −48.403 | 50.951 | 3.997 | −0.950 | 0.396 |

| Placevelar:Voweliː | 42.146 | 92.298 | 3.986 | 0.457 | 0.672 |

| Placevelar:Vowelaː | 99.911 | 93.299 | 3.987 | 1.071 | 0.345 |

| Placevelar:Vowelɛː | 182.320 | 93.331 | 3.992 | 1.953 | 0.123 |

| Placevelar:Voweluː | 86.955 | 93.301 | 3.987 | 0.932 | 0.404 |

Table of estimates for mixed model on mean normalized F2 over the first 10 sampling points after Mnong plain stops. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | df | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1,395.538 | 50.029 | 9.768 | 27.895 | 0.000 |

| RegisterLow | 154.073 | 30.487 | 9.000 | 5.054 | 0.001 |

| PlaceVelar | −143.615 | 81.951 | 8.940 | −1.752 | 0.114 |

| Voweliː | 734.439 | 60.300 | 8.979 | 12.180 | 0.000 |

| Vowelaː | 251.044 | 65.807 | 8.971 | 3.815 | 0.004 |

| Vowelɛː | 539.605 | 65.904 | 9.024 | 8.188 | 0.000 |

| Voweluː | −107.116 | 66.048 | 9.102 | −1.622 | 0.139 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweliː | 435.954 | 100.918 | 8.930 | 4.320 | 0.002 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelaː | 205.792 | 105.121 | 8.958 | 1.958 | 0.082 |

| PlaceVelar:Vowelɛː | 348.180 | 105.146 | 8.967 | 3.311 | 0.009 |

| PlaceVelar:Voweluː | −190.740 | 105.238 | 8.998 | −1.812 | 0.103 |

Appendix III: Mixed binary logistic regressions

Table of estimates of the final logistic regression model for /aː/. Estimates represent the log odds of high register responses. OQ, F1 and F2 are centered. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.487 | 0.089 | −5.449 | 0.000 |

| F1 | 2.177 | 0.117 | 18.534 | 0.000 |

| F2 | −0.204 | 0.033 | −6.187 | 0.000 |

| OQ | −0.406 | 0.076 | −5.341 | 0.000 |

| Voicingneg | 0.089 | 0.088 | 1.012 | 0.312 |

| Voicing10 | 0.234 | 0.061 | 3.874 | 0.000 |

| OQ:Voicingneg | −0.181 | 0.073 | −2.459 | 0.014 |

| OQ:Voicing10 | −0.063 | 0.073 | −0.859 | 0.390 |

Table of estimates of the final logistic regression model for /uː/. Estimates represent the log odds of high register responses. OQ, F1 and F2 are centered. Significant factors and interactions are bolded.

| Estimate | Std. error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.514 | 0.109 | 4.696 | 0.000 |

| F1 | 0.692 | 0.063 | 10.907 | 0.000 |

| F2 | −0.262 | 0.037 | −7.004 | 0.000 |

| OQ | −0.037 | 0.068 | −0.544 | 0.586 |

| Voicingneg | 0.255 | 0.058 | 4.393 | 0.000 |

| Voicing10 | 0.143 | 0.067 | 2.124 | 0.034 |

References

Abramson, Arthur S., Therapan Luangthongkum & Patrick W. Nye. 2004. Voice register in Suai (Kuai): An analysis of perceptual and acoustic data. Phonetica 61. 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1159/000082561.Suche in Google Scholar

Abramson, Arthur S., Patrick W. Nye & Therapan Luangthongkum. 2007. Voice register in Khmu’: Experiments in production and perception. Phonetica 64. 80–104. https://doi.org/10.1159/000107911.Suche in Google Scholar

Abramson, Arthur S., Mark K. Tiede & Therapan Luangthongkum. 2015. Voice register in Mon: Acoustics and electroglottography. Phonetica 72. 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441728.Suche in Google Scholar

Adisasmito-Smith, Niken. 2004. Phonetic influences of Javanese on Indonesian. Ithaca: Cornell University PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Blood, Henry. 1976. The Phonemes of Uon Njun Mnong Rơlơm. Mon-Khmer Studies 5. 4–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Boersma, Paul & David Weenink. 2010. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer.Suche in Google Scholar

Bon, Noëllie. 2014. Une grammaire de la langue stieng, langue en danger du Cambodge et du Vietnam. Lyon: Université Lyon PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Brunelle, Marc. 2005. Register and tone in Eastern Cham: Evidence from a word game. Mon-Khmer Studies 35. 121–132.Suche in Google Scholar

Brunelle, Marc. 2010. The role of larynx height in the Javanese tense ∼ lax stop contrast. In Rafael, Mercado, Eric, Potsdam & Lisa, Travis (eds.), Austronesian contributions to linguistic theory: Selected proceedings of AFLA, 7–24. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.167.03bruSuche in Google Scholar

Brunelle, Marc, Jeanne Brown & Thị Thu Hà Phạm. 2022. Northern Raglai voicing and its relation to southern Raglai register: Evidence for early stages of registrogenesis. Phonetica 79. 151–188. https://doi.org/10.1515/phon-2022-2019.Suche in Google Scholar

Brunelle, Marc, Leb Ke, Thành Tấn Tạ & Lư Giang Đinh. 2024. Voicing or register in Jarai dialects? Implications for the reconstruction of Proto-Chamic and for registrogenesis. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025100324000021.Suche in Google Scholar

Brunelle, Marc & Văn Hẳn Phú. 2019. Colloquial Eastern Cham. In Alice Vittrant & Justin Watkins (eds.), The Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, 522–557. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110401981-012Suche in Google Scholar

Brunelle, Marc, Thành Tấn Tạ, James Kirby & Lư Giang Đinh. 2019. Obstruent devoicing and registrogenesis in Chru. In Sasha Calhoun, Paola Escudero, Marija Tabain & Paul Warren (eds.), Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Canberra: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc, 517–521.Suche in Google Scholar