Abstract

This study investigates the link between terrorist attacks and public interest in radical Islam and violent extremism, using monthly data from 150 countries between 2004 and 2015. Employing a dynamic common correlated effects (DCCE) estimator to account for potential cross-country correlations, our analysis reveals that attacks carried out in the name of Islam significantly drive online searches for sensitive keywords. Specifically, terms suggesting violent actions, such as “beheadings,” and explicitly jihad-related terms show stronger correlations, indicating heightened interest in the terrorists’ actions and messages. Our findings suggest that terrorist attacks not only occur in areas where public attention to terrorism is already heightened but also intensify interest in violent extremism within those regions. This amplification may contribute to terrorists’ objectives by increasing the public visibility they seek.

1 Introduction

Terrorists strive to capture public attention to recruit new followers and disseminate their message, ultimately bolstering their capacity to inflict harm (Nelson and Scott 1992). Understanding how public interest in violent ideologies relates to terrorist attacks is crucial to preventing the escalation of radicalization into violence. However, gauging the popularity of terrorists and their ideologies is challenging for multiple reasons. News coverage of terrorism does not reliably indicate the public’s active interest or opinions, which can be heavily shaped by biased media sources (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2004). Furthermore, curiosity about and support for extremist ideologies are often understated and considered taboo, complicating efforts to measure these sentiments through surveys or experimental methods (Stephens-Davidowitz 2014).

In this paper, we examine the relationship between public interest in violent extremism and terrorist attacks, with a focus on Islamist terrorism. This specific focus allows us to identify a range of distinctive keywords associated with radical Islam. Building on the classification of keywords developed by Ahmed and Lloyd George (2016), we selected 47 sensitive online queries and gathered their monthly Google search volumes globally from 2004 to 2015. These keywords include terms indicative of curiosity about radical Islam, expressions of sympathy towards terrorist ideologies, and phrases explicitly related to violent jihadist actions, such as the killing of infidels. Data on terrorist attacks were sourced from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD). Since the GTD does not specify the origins of the attacks, we undertook additional efforts to document the backgrounds and motivations of the terrorist groups involved. Our comprehensive database comprises detailed information on 21,710 attacks carried out worldwide by self-proclaimed Islamist groups in the name of Islam.

We provide evidence of a positive correlation between online searches for sensitive keywords and Islamist attacks. The association is robust to controlling for cross-country dependence, which is especially crucial in this context as a globally common shock, such as the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers, might spillover and have varying impacts across different countries. Upon looking into specific keywords, we find that attacks are more significantly and sizably associated with “extreme” queries, particularly those relating to violence, such as “beheadings”, or those explicitly related to the jihad, such as “Abdullah Azzam”, a Sunni scholar and founding member of Al Qaeda, also known as the “Father of Global Jihad” (Edwards 2017). This result survives several robustness checks and placebo tests. When we extend the analysis to incorporate spatial lags, our results indicate that Google searches in neighboring countries are positively and significantly correlated with attacks. This suggests that when an Islamist attack occurs in a given country, individuals in surrounding countries tend to increase their searches for sensitive keywords. Interestingly, while the spatial lag for extreme keywords is not statistically significant in the global sample, it becomes both statistically significant and larger in magnitude when restricting the analysis to countries that have experienced an Islamist attack. Overall, these findings highlight the role of geographic proximity in shaping online search behavior, particularly in regions with a history of Islamist terrorism. We also expanded our analysis by including temporal lags of Google searches: the coefficient for Google searches in the previous month is positive and significant, suggesting that past search activity is positively associated with subsequent Islamist attacks.

While we cannot claim causality in interpreting our results, the empirical analysis contributes to the understanding of the relationship between terrorism and the active interest in violent extremism in several ways. Previous studies suggest that the media coverage of terrorist attacks feeds violent extremism, as the attention of the public encourages terrorists to plan new attacks. Our approach offers a way to measure the public’s attention to extremist ideas and documents its relationship with terrorists’ missions. The link between the occurrence of the attacks and searches for violent and extreme keywords is striking. This suggests that terrorists choose to attack in places where there is a high level of interest and consideration for their claims and operations. In turn, these attacks nurture public interest in violent extremism in those regions potentially aiding terrorists in garnering the public attention they seek.

This paper bridges two strands of literature. The first strand deals with the relationship between media and terrorism (El Ouadghiri and Peillex 2018; Gentzkow and Shapiro 2004; Jetter 2017, 2019; Rohner and Frey 2007). Our study builds on this body of research by linking it to the broader empirical literature on the determinants of terrorism, aiming to uncover the underlying drivers of terrorist activities. Previous research has explored the relationship between terrorism and underdevelopment (Feridun and Sezgin 2008), poverty (Caruso and Schneider 2013), education (Bassetti, Caruso, and Schneider 2018), declining social capital (Helfstein 2014), natural resource rents (Ajide and Alimi 2020), fiscal decentralization (Arzaghi and Gaibulloev 2024), immigration (Bove and Böhmelt 2016), and political exclusion (Choi and Piazza 2016). Our work contributes to this body of literature by using Google searches to address the challenge of detecting the popularity and celebrity status of terrorists. Moreover, we show that the public’s active attention to terrorists’ claims, such as intentional searches of specific keywords, rather than passive news consumption, is strongly correlated with terrorist attacks. This result aligns with recent evidence that terrorist attacks provoke enduring public reactions (Bove, Efthyvoulou, and Pickard 2024). These responses can manifest not only as heightened interest in terrorist messaging and fear of further attacks but also as reinforced national identity and increased support for national and supranational institutions (Efthyvoulou, Pickard, and Bove 2024). Additionally, our finding that the severity of attacks, measured by the number of casualties and injuries, generates stronger public interest in terrorist activities further corroborates the insights from Bove, Efthyvoulou, and Pickard 2024; Efthyvoulou, Pickard, and Bove 2024, who document that attacks with a higher number of victims elicit stronger and more prolonged public reactions.

The second strand encompasses studies using online searches to track hidden or difficult to measure social phenomena such as racism (Doleac and Stein 2013; Giulietti, Tonin, and Vlassopoulos 2019; Stephens-Davidowitz 2014), contraceptive use and abortion (Kearney and Levine 2015), religiosity (Bentzen 2019), pornography (MacInnis and Hodson 2015), and prosocial attitudes (Guriev and Melnikov 2016). We connect to this literature by introducing the use of online searches in the study of radicalization and terrorism. Moreover, we contribute by adopting an econometric approach that accounts for cross-sectional dependence, which addresses some of the criticisms of using Google searches in research.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: in the next section, we describe our data on online searches of sensitive keywords and terrorist episodes. We then explain our econometric approach in Section 3. Section 4 presents the analysis of the relationship between the online interest in Islamist extremism and terrorist attacks and the robustness checks. In Section 5, we briefly summarize and discuss our main findings. Section 6 concludes.

2 Data

2.1 Measuring Interest in Radical Islam and Violent Extremism

As of January 2019, almost 4.4 billion people were active Internet users, roughly corresponding to 59 % of the global population.[1] With around 90 % market share worldwide between 2010 and 2015, Google is by far the world’s leading search engine.[2] Starting from January 2004, the company has made available information on the queries that people search on the engine with a tool called Google Trends (hereafter GT).[3] The empirical evidence shows that GT consistently and strongly detect many phenomena for which conventional data are publicly available with a delay, or at a lower frequency. For example, queries consistently detect economic behaviors such as job searches (Baker and Fradkin 2017), the issuance of bad checks (Eksi, Gurdal, and Orman 2017), deposit reallocation (Fecht, Thum, and Weber 2019), and the use of Uber services (Berger, Chen, and Frey 2018), to name a few.

However, it is in the detection of usually undercover interests and behaviors that Google searches play a crucial role. Online searches are generally conducted in private, elude social control, and allow people to express socially taboo, anti-social, or even criminal interests and attitudes that they would hardly reveal in public. For example, MacInnis and Hodson (2015) use GT to study how interest in pornography relates to religiosity and conservatism across American states. Google-based measures of racism strongly predict black mortality (Chae et al. 2015), black homeownership (Harris and Yelowitz 2018), access to public services (Giulietti, Tonin, and Vlassopoulos 2019), and the performance of Barak Obama in 2008 and 2012 U.S. presidential elections (Stephens-Davidowitz 2014). Google data have also proved helpful in detecting or predicting contraceptive use and abortion (Kearney and Levine 2015), suicides (Ma-Kellams et al. 2015), drug abuse (Perdue, Hawdon, and Thames 2018), and the propagation of sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis (Young et al. 2018) and HIV (Young and Zhang 2018).

Along these lines, the interest in anti-system groups is a typically hidden social pattern that Google searches can help uncover. Research into the relationship between the Internet and terrorism has so far focused on the role of social networking sites (Aly et al. 2016; Weimann 2015). Tracking jihadi propaganda on social media is useful for detecting extremists’ communication and enacting counter-terrorism measures (Zeitzoff 2017). However, radicalized individuals’ activities on platforms like Facebook and Twitter do not necessarily capture the attention of the general public in Islamist terrorism. People likely radicalize as a result of the spreading of feelings sympathetic to extremists across society, a phenomenon that eludes detection through social media (Ahmed and Lloyd George 2016). Search engines, by contrast, can help to detect the active attention of the public to extremist ideas (Jetter 2019).

In our empirical analysis, we use a list of keywords that, according to the Centre on Religion & Geopolitics (CRG), are likely to lead to extremist content if entered into a search engine. The CRG first developed a set of words and phrases that might be used in research on radical Islam or in deliberate attempts to access violent extremist content. The list was then employed as a basis to ascertain further potentially associated keywords through specific tools such as Google Keyword Planner, Google Suggest phrases, and Google-related searches. The final list comprised 143 keywords.

Based on the search frequency data and a qualitative assessment, the CRG then selected a set of 47 keywords. The set is the sum of two subgroups. The first includes popular keywords that were searched on average at a minimum frequency of 500 times per month. The second group includes keywords explicitly related to violent extremism. Ahmed and Lloyd George (2016) conducted a search engine result page (SERP) analysis of the keywords to ascertain the extent to which they return “extreme” content. Though being non-violent and mostly related to political Islam, keywords belonging to the first group return extremist content in a remarkable share of cases, anticipating the risk of unintentional exposure to jihadi propaganda. The second set comprises keywords that, though being less popular, carry a higher potential for risk. Overall, 44 % of the material was explicitly violent. In contrast, counter-narrative content outperformed extremist material in only 11 % of the results generated.[4]

Several sites aiming to present legitimate Islamic culture were also found to host extremist material. For example, Kalamullah.com and WorldofIslam.info – which can be retrieved by entering our selection of keywords into a search engine – contain resources for ordinary Muslims and those interested in Islam, such as online versions of the Quran, collections of Hadith literature, and a variety of Islamic books. However, these sites also provide jihadi manuals and audio lectures by known jihadis. Overall, the Google searches for the chosen set of keywords returned a vast array of fundamentalist material spanning from non-violent extremism to explicitly violent jihadism.

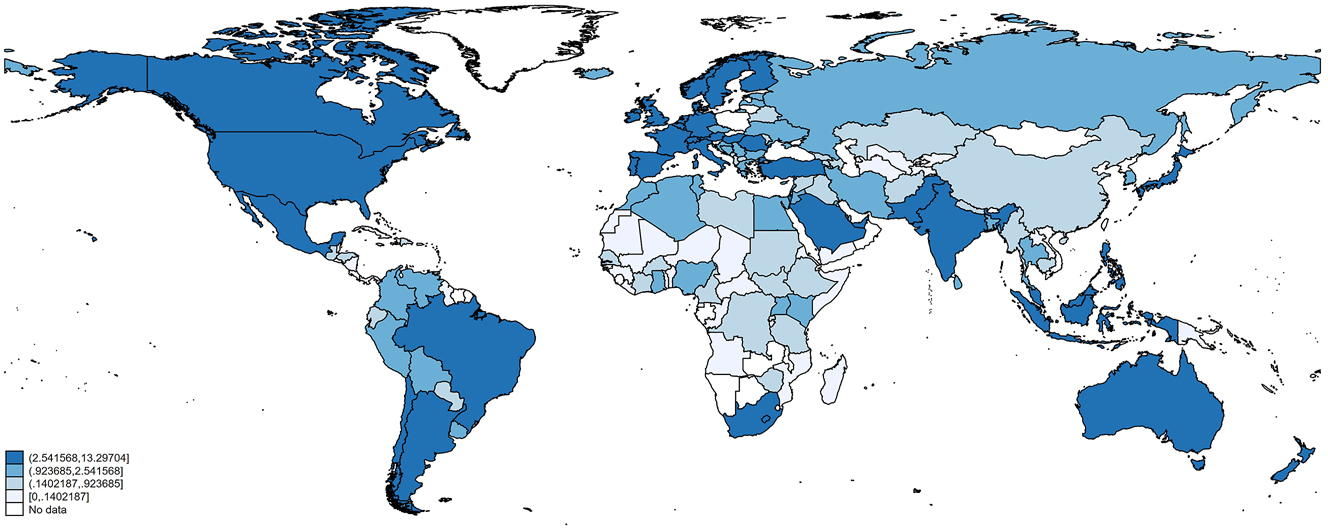

We use the GT for the 47 keywords to measure the active interest in radical Islam in 149 countries over the period 2004–2015. Figure 1 shows on a map the normalized volume of searches for the keywords worldwide. While Google is the predominant search engine in most countries, there are some notable exceptions, e.g., China. This could go in the direction of weakening the link we expect to detect between online searches, measured through GT, and terrorist attacks.

Google trends monthly averages for the mean of the 47 search terms. Notes: The intervals plotted correspond to the quartiles of the distribution of the monthly GTs for the average of the 47 keywords.

A variety of people may be searching for keywords that return extremist content, from academics to journalists. We do not claim to be measuring the online search activity of perspective terrorists. Instead, we assume that Google searches measure the interest of the public in radical Islam and violent extremism. Previous studies employing Google searches to assess the hypothetical outcomes of social phenomena all share the assumption that trends for specific keywords can proxy the incidence of hidden social patterns in the population (e.g., Stephens-Davidowitz 2014; Kearney and Levine 2015; Guriev and Melnikov 2016).

Table 1 reports the list of keywords. We provide a glossary with a brief description of their meaning in Appendix A.1.

List of the 47 keywords.

| Most popular | Most extreme |

|---|---|

| Apostasy | Abdullah Azzam |

| Apostate | Amaq Agency |

| Apostates | Apostate Islam |

| Ayman al-Zawahiri | Apostates in Islam |

| Caliphate | Beheadings |

| Crusader | Crusader Army |

| Crusaders | Crusaders against Islam |

| Dabiq | Dabiq Pdf |

| Dabiq Magazine | How to do Jihad |

| Ibn Taymiyyah | Ibn Taymiyyah Jihad |

| Islamic State | Inspire Magazine |

| Jihad | Jewish Coalition |

| Jihad meaning | Jihad for Ummah |

| Kafir | Jihad in the Quran |

| Khalifah Meaning | Khalifah |

| Khilafah | Khilafah Syria |

| Kuffar | Killing Apostates |

| Martyr | Killing Infidels |

| Martyrdom in Islam | Killing Kuffar |

| Martyrs | Mujahid |

| Mujahideen | Preparing for Jihad |

| Shahada | Rafidah |

| Suicide vest | Soldiers of the Caliphate |

| Taghut |

2.2 Terrorist Attacks

Data on terrorist attacks are drawn from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) at the University of Maryland. The database collects information on the attacks perpetrated around the world from 1970 through 2018. Including more than 190,000 cases over the whole period, and 80,694 over our period of analysis (2004–2015), the GTD is the most comprehensive unclassified database on terrorist attacks.[5] Differently from other databases on terrorism, the GTD includes systematic data on domestic as well as transnational and international terrorist incidents. For each attack, the database provides information on several variables, among which the date and location, the weapons used, the nature of the target, the number of casualties (distinguishing victims into deaths and wounded), and, when available, the group or individual responsible for the attack.

We make an additional effort to collect further information on the 999 terrorist groups identified in the GTD that have been active in the 2004–2015 period. We classify groups according to their ideology or intent. Inspecting each terrorist event allows us to enrich the GTD database by further categorizing the attacks according to the ideology, religious background, and motivation of the perpetrating group. Out of 80,694 events, it is possible to identify the group’s background in 34,907 cases (43.3 % of cases). Religious fundamentalist organizations have caused two-thirds of these events, and 97.8 % of the attacks with a religious identity have been perpetrated by self-proclaiming Islamist groups, corresponding to 21,710 registered attacks. We document the distribution of terrorist attacks with identified authors across religions in Table A.1 in Appendix A.2.

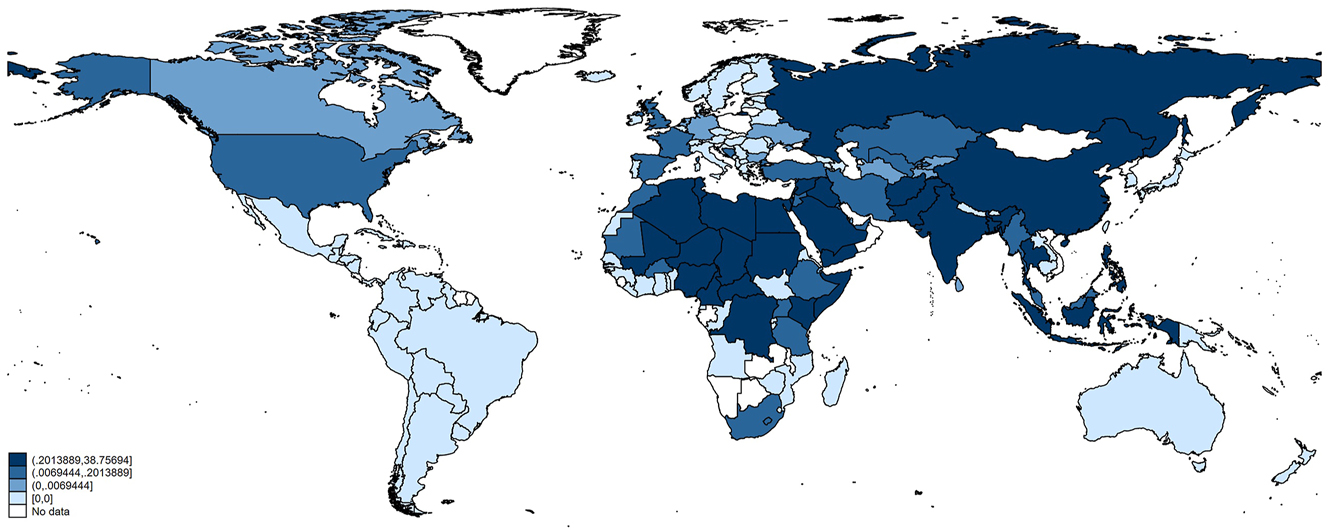

Figure 2 reports the incidence of Islamist attacks. They are widespread globally: more than 60 countries in the world have been hit at least once in the 2004–2015 period.

Average monthly islamist attacks. Notes: The intervals plotted correspond to the quartiles of the distribution of average monthly islamist attacks.

3 Econometric Approach

We collect data on all countries that faced at least one terrorist attack of any kind over the period 2004–2015. The sample includes 149 countries, with data collected at monthly frequency. However, given that there were no Islamist attacks in many countries, as evident from Figure 2, we present results both in the full sample and in the subset of 63 countries in which at least one Islamist attack took place. Our panel is characterized by a wide cross-sectional dimension, but also a long time span, thanks to the availability of monthly data for 12 years (t = 144).

The breadth of our sample calls for a thorough consideration of the characteristics of our data for two reasons. First, including common confounders of terrorism would improve the quality of our analysis, but proves to be difficult. Many of these variables, e.g., an index of income inequality, GDP per capita, educational attainment, or the share of the Muslim population, are either not available monthly or generally present little time variability. In the latter case, the country-fixed effects included in the estimating equation are a good proxy for these omitted variables. While this approach provides some partial solution to the omitted variables problem, we still need to better control for the properties of our series. Second, the maps discussed in Section 2 clearly show a spatial clustering of the Islamist attacks and the GT. Searches for sensitive keywords might increase not only in the country hit by a terrorist attack but also in the neighboring countries, where the media are likely to give wide coverage to terrorists, thereby involving the attention of the public.[6] The existence of this geographical dependence is confirmed by the cross-section dependence (CD) test statistic (Pesaran 2004), which shows a positive cross-country correlation of 0.190 for Islamist attacks and 0.228 for GT. The econometric specification will therefore take into account these patterns. We also test for the presence of trends in our data, finding that our variables of interest are stationary: we can safely rule out any spurious correlation driven by trends in our data.[7] Finally, we might suspect that both Islamist attacks and web searches of online content depend on their past values, e.g., the likelihood of a terrorist attack at time t is higher in a country with a history of terrorist attacks, like Afghanistan. We thus perform the Wooldridge (2002) test for serial correlation in panel data, which confirms the presence of first order autocorrelation in the residuals.

To account for these features of our data we choose the dynamic common correlated effects model (DCCE) by Chudik and Pesaran (2015). This is a dynamic model, i.e. a model that accounts for autocorrelation, which also controls for cross-sectional dependence. This approach is a novelty in the literature on media and terrorism, as well as for studies that use online searches to track hidden behaviors. This methodological contribution is important as it allows to attenuate one possible critique to the use of GT across countries, namely the fact that they are an index normalized at country-level. We thus estimate the following model:

where IA

ct

is the number of Islamist attacks perpetrated in country c at time t; α

c

are the country fixed effects; IAct−1 is the lagged value of IA; GT

ct

is an aggregate measure of Google searches, obtained as the mean of the 47 keywords search volumes in country c at time t;

We delve deep into our results by considering alternative measures of GTs. First, we use the first factor of a principal component analysis (PCA) of the 47 keywords.[8] We then consider different sub-aggregations of keywords. A first natural classification is the one into “popular” and “extreme” keywords, as proposed by Ahmed and Lloyd George (2016). We add to this distinction several alternative aggregations to capture different aspects of online searches for Islamist and extremist content.

To investigate how terrorist attacks and search activity in neighboring countries influence attacks within each country, we enhance our model by incorporating spatial lags of both the Islamist attacks variable and Google searches for our selected sets of keywords. Using a contiguity matrix, we construct spatially lagged versions of both the dependent and independent variables and integrate these additional regressors into the DCCE estimation.

Additionally, we expand our analysis by including temporal lags in Google searches. Incorporating lags of our explanatory variable results in a situation where the rank condition for the matrix of cross-products of cross-sectional averages is not satisfied. Consequently, only mean group estimates remain consistent, while unit-specific estimates become inconsistent. Since the mean group estimates are still valid, we can fully interpret this set of results.

A further avenue to deepen our analysis focuses on the outcomes of the attacks. We present evidence on the relationship between Google searches for sensitive keywords and some measures of the damage caused by terrorists' missions. As a final robustness check, we provide several placebo tests to control further for the possibility that our results capture a spurious correlation, either working on the dependent or the explanatory variables. First, we consider the overall number of attacks, irrespective of the religious or ideological motivation behind them. We expect the latter to be poorly or not at all correlated to the GT for our keywords. Then, we follow D’Amuri and Marcucci (2017) and use a neutral word, such as “dos”, and check its relationship with Islamist attacks.

3.1 Alternative Econometric Specifications

We discuss the difference between the DCCE estimator employed in our analysis and other popular alternatives. The first and most obvious option is the standard fixed effects (FE) model:

where IA ct is the number of Islamist attacks perpetrated in country c at time t, α c are the country fixed effects, and GT ct is the aggregate measure of Google searches.

Recent developments in econometric methods suggest that with panel times series data, with a large dimension of observations over cross-sectional units (N) and time periods (T), the assumption of homogeneity of slope parameters is often inappropriate (Pesaran and Smith 1995; Pesaran, Shin, and Smith 1999). In such a case, the coefficients differ randomly across countries:

where f

t

is an unobserved common factor and γ

c

is a heterogeneous factor loading. The heterogeneous coefficients β

c

are randomly distributed around a common mean such that β

c

= β + v

c

, v

c

∼ IID(0, Ω

v

), where Ω

v

is the variance–covariance matrix. The error term ɛ

ct

is composed of an unobserved common factor with heterogeneous factor loadings

An additional feature of the panel times series data is the existence of cross-sectional dependence. To account for this issue, Pesaran (2006) proposes the common correlated effects (CCE) estimator. The CCE builds on the MG setting in equation (3) and can be consistently estimated by including among the explanatory variables the cross-section averages of

The dynamic DCCE by Chudik and Pesaran (2015), which we adopt in our main analysis, is a generalization of this approach it incorporates dynamic patterns in the data.

4 Results

We begin our discussion of results with a comparison of the DCCE estimator with more widely adopted estimators in Table 2. We report the results obtained with a standard fixed effects model in column 1. There is a positive and significant correlation between the average search volume of the 47 keywords and the occurrence of Islamist terrorist attacks, both in the sample of 149 countries that faced a terrorist attack of any kind in the period under consideration (Panel A) and in the subsample of 63 countries hit by an Islamist attack (Panel B). Column 2 shows the results using the mean group (MG) estimator, which allows for slope heterogeneity across countries: the coefficient for GT is not significant. Nonetheless, the CD statistic points towards the presence of unaccounted cross-section dependence, thus suggesting that neither the FE nor the MG estimator are appropriate in our context.

Alternative econometric specifications.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | FE | MG | CCE | DCCE |

| GT t | 0.076** | 0.052 | 0.083*** | 0.048** |

| (0.033) | (0.171) | (0.030) | (0.019) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.062*** | |||

| (0.012) | ||||

| Constant | 0.865*** | |||

| (0.070) | ||||

|

|

||||

| Wooldridge test for autocor. in panel data | 8.540*** | 7.182*** | 5.103** | 0.003 |

| (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.025) | (0.955) | |

| CD statistic | 14.609*** | −0.483 | −0.498 | |

| (0.000) | (0.629) | (0.618) | ||

| R2 | 0.000 | 0.973 | 0.990 | 0.826 |

| R2 (MG) | 0.020 | 0.786 | 0.825 | |

| # Observations | 21,456 | 21,456 | 21,456 | 21,158 |

| # Countries | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

|

|

||||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | FE | MG | CCE | DCCE |

|

|

||||

| GT t | 0.129* | 0.124 | 0.195*** | 0.108*** |

| (0.066) | (0.407) | (0.066) | (0.041) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.145*** | |||

| (0.025) | ||||

| Constant | 2.071*** | |||

| (0.176) | ||||

|

|

||||

| Wooldridge test for autocor. in panel data | 8.372*** | 7.116*** | 5.113** | 0.005 |

| (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.027) | (0.946) | |

| CD statistic | 34.712*** | −1.109 | −1.220 | |

| (0.000) | (0.268) | (0.223) | ||

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.973 | 0.991 | 0.826 |

| R2 (MG) | 0.020 | 0.786 | 0.825 | |

| # Observations | 9,072 | 9,072 | 9,072 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

The dependent variable is the number of islamist attacks. GT is the mean of the Google Trends for the 47 English keywords. Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

With the common correlated effects (CCE) estimator (Pesaran 2006), reported in column 3, Google searches display a positive and significant coefficient. The CD statistic suggests that the CCE handles the cross-section dependence properly. However, the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data suggests that we can not reject the null hypothesis. For this reason, we move to the DCCE model in column 4, which is our main specification reported in Table 3 column 1. Again, the coefficient of interest keeps its significance level. Moreover, it is worth discussing the magnitude of the estimated coefficient: a one-standard-deviation increase in Google searches corresponds to a change in the Islamist attacks equivalent to approximately 12.4 % of its mean, indicating a moderate effect size in relative terms. This number increases to 14.3 % in the subsample of countries hit by Islamist attacks.[9]

Alternative definitions of GTs.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | Mean | Factor | Popular | Extreme |

| GT t | 0.048** | 0.083*** | 0.020** | 0.031** |

| (0.019) | (0.031) | (0.009) | (0.012) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.061*** |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.013) | |

|

|

||||

| R2 | 0.826 | 0.818 | 0.828 | 0.803 |

| # Observations | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 |

| # Countries | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

|

|

||||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | Mean | Factor | Popular | Extreme |

|

|

||||

| GT t | 0.108*** | 0.187*** | 0.042** | 0.080*** |

| (0.041) | (0.069) | (0.019) | (0.030) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.145*** | 0.147*** | 0.145*** | 0.144*** |

| (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.026) | |

|

|

||||

| R2 | 0.826 | 0.814 | 0.829 | 0.801 |

| # Observations | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

DCCE estimates. The dependent variable is the number of Islamist attacks. Mean is the unweighted mean of the GTs for the 47 keywords, Factor is the first factor from a PCA on the 47 keywords. For the Popular and Extreme groupings, see Table 1. Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

We present our main results using alternative measures of the volume of Google searches in Table 3.[10] Column 1 in Panel A reports our preferred specification, with the mean value of the 47 keywords. In column 2, we present the results with the first factor of a principal component analysis (PCA) of the 47 different keywords. We observe a positive and statistically significant coefficient for GT. The lagged value of the dependent variable, IA, also displays a positive and significant coefficient, as expected: while investigating the relationship between Islamist attacks and Google searches, we cannot neglect the existence of attacks in the previous period.

To explore the relationship between Google searches and the attacks in greater depth, we differentiate between keywords. Our goal here is to distinctly focus on terms that may indicate a genuine interest in radical ideology instead of merely reflecting a heightened attention to terrorism news and events. First, we adopt the classification of “popular” and “extreme” keywords as proposed by Ahmed and Lloyd George (2016), which is reported in Table 1. We compute the average volume of Google searches for the two groups. Both “popular” and “extreme” keywords significantly and positively relate to the attacks, with extreme keywords displaying a larger coefficient.

Panel B of Table 3 shows the results on the subsample of 63 countries that experienced at least one Islamist attack in the period under consideration. Across different specifications, results reported in Panel B confirm those on the full sample: the sign and statistical significance of coefficients do not change, but we notice a slight increase in their size. As countries that did not face attacks perpetrated in the name of Islam are now excluded from the sample, the specification in Panel B likely captures the relationship between the interest of the public to Islamist extremism and Islamist attacks more neatly. Not surprisingly, the estimated coefficients are slightly larger in this subsample.

To better understand the positive correlation between Google searches and terrorist attacks perpetrated by self-proclaiming Islamist organizations, we distinguish the keywords into six groups according to their meaning. The first two categories include keywords referring to ISIS and Al Qaeda, respectively. In the third group, we focus on apostasy: in radical Islam, apostasy is not necessarily understood as the personal choice of renouncing a religious belief. Instead, it is often considered a public act of political secession from the Muslim community. This view makes apostates one of the favorite targets of jihadi propaganda (Torres Soriano 2010). The fourth group comprises keywords evoking violent actions, such as “beheadings”. The fifth and sixth categories contain terms related to religious doctrines and the history of political Islam, respectively.[11] For each group, we compute the average volume of Google searches and assess its relationship with terrorist attacks perpetrated in the name of Islam.

Panel A of Table 4 reports results in all countries that faced an attack. The sets of keywords related to the two most prominent Islamist terrorist groups, Al Qaeda and ISIS, are not significant. Queries referring to the concept of apostasy in Islam, such as “kafir” and “kuffar”, significantly and positively correlate with the attacks. The index of violent keywords, including queries like “beheadings” and “killing infidels”, significantly and positively relates to the attacks. The aggregations of keywords comprising the doctrinal and historical terms are instead not statistically significant.[12] Panel B of Table 4 reports the results on the subsample of countries affected by Islamist attacks in the period under consideration. Again we observe an increase in the size of the estimated coefficients.

Alternative aggregations of GTs.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | ISIS | Al Qaeda | Infidels | Violent | Religion | History |

| GT t | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005* | 0.035*** | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.014) | (0.006) | (0.002) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.060*** | 0.065*** | 0.063*** | 0.062*** | 0.064*** | 0.061*** |

| (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |

|

|

||||||

| R2 | 0.815 | 0.793 | 0.794 | 0.814 | 0.790 | 0.825 |

| # Observations | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 |

| # Countries | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

|

|

||||||

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | ISIS | Al Qaeda | Infidels | Violent | Religion | History |

|

|

||||||

| GT | −0.009 | 0.004 | 0.011* | 0.088** | 0.012 | 0.002 |

| (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.006) | (0.035) | (0.012) | (0.005) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.140*** | 0.154*** | 0.149*** | 0.149*** | 0.150*** | 0.142*** |

| (0.025) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.027) | (0.026) | |

|

|

||||||

| R2 | 0.820 | 0.794 | 0.798 | 0.809 | 0.796 | 0.826 |

| # Observations | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

DCCE estimates. The dependent variable is the number of Islamist attacks. For the definition of the different groupings, see Table A.2. Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

We extend our analysis by incorporating spatial lags of our variables of interest. Specifically, we enhance our model by including spatial lags of the Islamist attacks variable and Google searches to examine how terrorist attacks and search activity in neighboring countries influence each focal country. Using a contiguity matrix, we construct spatially lagged versions of both the dependent and independent variables and integrate these additional regressors into the DCCE estimation. The results are presented in Table 5.

Introducing spatial lags.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | Mean | Popular | Extreme |

| GT t | 0.059*** | 0.023** | 0.040*** |

| (0.021) | (0.010) | (0.016) | |

| GTt,s−1 | 0.171* | 0.084* | 0.113 |

| (0.096) | (0.044) | (0.069) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.053*** | 0.054*** | 0.049*** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| IAt,s−1 | 0.048 | 0.050 | 0.055 |

| (0.043) | (0.044) | (0.036) | |

|

|

|||

| R2 | 0.838 | 0.838 | 0.830 |

| #Observations | 20,874 | 20,874 | 20,874 |

| # Countries | 147 | 147 | 147 |

|

|

|||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | Mean | Popular | Extreme |

|

|

|||

| GT t | 0.125*** | 0.052** | 0.092*** |

| (0.047) | (0.022) | (0.033) | |

| GTt,s−1 | 0.441** | 0.209** | 0.346** |

| (0.205) | (0.101) | (0.162) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.125*** | 0.126*** | 0.118*** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.024) | |

| IAt,s−1 | 0.021 | 0.039 | 0.057 |

| (0.084) | (0.085) | (0.071) | |

|

|

|||

| R2 | 0.826 | 0.827 | 0.805 |

| #Observations | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

DCCE estimates. The dependent variable is the number of islamist attacks. Mean is the unweighted mean of the GTs for the 47 keywords, for the Popular and Extreme groupings, see Table 1. Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

This analysis reveals two key insights. First, we find no statistically significant relationship between Islamist attacks in neighboring countries and the occurrence of an attack in a given focal country. In other words, the likelihood of experiencing an Islamist attack in country i does not appear to be influenced by attacks in contiguous countries.

However, this null result contrasts sharply with the effect of Google search activity in neighboring countries. The spatial lag of Google searches is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that when an Islamist attack occurs in country i, individuals in surrounding countries tend to increase their searches for sensitive keywords. More relevant is the finding that if we consider popular and extreme keywords separately, the spatial lag for extreme words is not statistically significant in the global sample, but it becomes statistically significant and larger in magnitude if we focus on the subsample of countries that experienced an Islamist attack. Overall, these findings indicate that geographic proximity plays a crucial role in shaping online search behavior, particularly in regions where Islamist attacks are more prevalent.

Another way in which we can expand our analysis is by including temporal lags of the Google searches. The results reported in Table 6 show that including Google searches at time t − 1 does not substantially alter our main findings regarding the contemporaneous Google searches and the lag of the dependent variable. The coefficient for Google searches in the previous month is positive and significant, suggesting that past search activity is positively associated with subsequent Islamist attacks. However, when we differentiate between popular and extreme keywords, we do not find any statistically significant effects. Notably, the significance of contemporaneous Google searches remains robust, particularly for extreme keywords.

Introducing temporal lags of Google searches.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | Mean | Popular | Extreme |

| GT t | 0.047* | 0.019* | 0.031** |

| (0.025) | (0.011) | (0.014) | |

| GTt−1 | 0.073* | 0.032 | 0.025 |

| (0.041) | (0.020) | (0.020) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.061*** | 0.060*** | 0.060*** |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.013) | |

|

|

|||

| R2 | 0.823 | 0.826 | 0.803 |

| #Observations | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 |

| # Countries | 149 | 149 | 149 |

|

|

|||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | Mean | Popular | Extreme |

|

|

|||

| GT t | 0.105** | 0.042* | 0.078** |

| (0.052) | (0.024) | (0.033) | |

| GTt−1 | 0.176* | 0.075 | 0.049 |

| (0.096) | (0.048) | (0.045) | |

| IAt−1 | 0.142*** | 0.140*** | 0.143*** |

| (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.026) | |

|

|

|||

| R2 | 0.824 | 0.828 | 0.801 |

| #Observations | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

DCCE estimates. The dependent variable is the number of islamist attacks. Mean is the unweighted mean of the GTs for the 47 keywords, for the Popular and Extreme groupings, see Table 1. Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

Finally, we explore how Google searches for our sensitive keywords relate to indicators of the outcomes of terrorist missions. To this end, we repeat the analysis using the number of killed, wounded, and overall affected people as dependent variables.[13] We report the results in Table 7: GT are positive and significant when considering the number of wounded and affected people, both on the full set of countries (Panel A) and in the subset of countries affected by an Islamist attack (Panel B). This suggests that larger attacks, that involve more victims, trigger more interest on the web.

Robustness with different measures of violence.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | y = killed | y = wounded | y = victims |

| GT t | 0.014 | 0.014* | 0.019* |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.011) | |

| y t−1 | 0.053*** | 0.047*** | 0.058*** |

| (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.012) | |

|

|

|||

| R2 | 0.881 | 0.907 | 0.880 |

| # Observations | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 |

| # Countries | 149 | 149 | 149 |

|

|

|||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | y = killed | y = wounded | y = victims |

|

|

|||

| GT | 0.034 | 0.034* | 0.045* |

| (0.021) | (0.018) | (0.026) | |

| y t−1 | 0.124*** | 0.112*** | 0.136*** |

| (0.025) | (0.023) | (0.026) | |

|

|

|||

| R2 | 0.880 | 0.907 | 0.879 |

| # Observations | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

DCCE estimates. The dependent variable is respectively, the log of killed persons, the log of wounded persons, the log of total victims (equal to the sum of killed and wounded). Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

As a further robustness check, we discuss two placebo tests for the main findings reported in column 1 of Table 3. First, we test whether Google searches are significantly and positively correlated with non-Islamist attacks. In Column 1 of Table 8, we report results using all kinds of attacks as dependent variable, including those perpetrated by non-Islamist terrorists. In columns 2, we remove Islamist attacks from the pool. We do not find any significant correlation between these attacks and searches for our sensitive keywords.

Placebo tests.

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries hit by any terrorist attack | y = all attacks | y = non-Islamist attacks | y = Islamist attacks | |

| GT t | 0.007 | −0.013 | ||

| (0.063) | (0.054) | |||

| dos t | 0.001 | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| google t | −0.047 | |||

| (0.106) | ||||

| y t−1 | 0.138*** | 0.138*** | 0.059*** | 0.059*** |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |

|

|

||||

| R2 | 0.663 | 0.671 | 0.815 | 0.794 |

| # Observations | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 | 21,158 |

| # Countries | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

|

|

||||

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Countries hit by Islamist attacks | y = all attacks | y = non-Islamist attacks | y = Islamist attacks | |

|

|

||||

| GT t | 0.066 | 0.015 | ||

| (0.141) | (0.118) | |||

| dos t | −0.001 | |||

| (0.002) | ||||

| google t | −0.135 | |||

| (0.264) | ||||

| y t−1 | 0.254*** | 0.254*** | 0.140*** | 0.138*** |

| (0.031) | (0.033) | (0.026) | (0.025) | |

|

|

||||

| R2 | 0.663 | 0.671 | 0.820 | 0.795 |

| # Observations | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 | 8,946 |

| # Countries | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 |

-

DCCE estimates. Columns 1–4 present placebo tests adopting alternative dependent variables. Columns 5 and 6 present placebo tests adopting different explanatory variables. The dependent variable is the total number of terrorist attacks (columns 1–2), the number of non-Islamist attacks (columns 3–4), while in columns 5 and 6 is the standard measure adopted throught the empirical analysis, the number of Islamist attacks. Standard errors in parentheses, ***, **, and * denote, respectively, 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels.

As a second exercise, we consider a term that is completely unrelated to the Islamist attacks. We follow D’Amuri and Marcucci (2017) and choose the term “dos”, which is an acronym for Disk Operating System.[14] We expect Google searches for the term “dos” to be unrelated to Islamist attacks. As reported in column 3 of Table 8, the coefficient is not statistically significant. We also repeat the exercise with the GT for “google” finding again that it is not correlated with the occurrence of the attacks. Panel B shows that the results of the placebo tests do not change when only considering the subsample of countries affected by Islamist attacks.

5 Discussion

Our panel analysis reveals a systematic relationship between Islamist attacks and online searches for a set of sensitive keywords over the period 2004–2015 worldwide: online searches are significantly and positively correlated to attacks. Different kinds of users may search for some of the keywords we employ in the empirical analysis, from students who want to deepen their knowledge of political Islam to journalists and scholars interested in researching violent extremism. Online searches may also detect the celebrity of terrorist organizations. However, we also use keywords explicitly denoting an interest in fanaticism and violence that might be searched by sympathizers of the jihad.

Distinguishing between keywords allows us to understand better the positive relationship between Google searches and the attacks. We divide our set of 47 keywords into two groups. The first group contains keywords with an average monthly frequency higher than 500 searches in the UK. Such searches are not explicitly violent and mostly regard political Islam. The SERP analysis conducted by Ahmed and Lloyd George (2016), however, shows that these seemingly non extremist searches often return extreme content aimed at explicitly promoting radicalization among Internet users. The second group contains more extreme queries, which are mostly related to violent extremism and systematically lead to fundamentalist, militant, and explicitly violent content (Ahmed and Lloyd George 2016).

We find that the online searches for both groups of queries are significantly associated with the attacks. The coefficient for the popular keywords signals that the celebrity of terrorists among the public is significantly and positively correlated with the attacks.

When we incorporate spatial lags to examine how terrorist attacks and search activity in neighboring countries influence attacks within each country, we find no statistically significant relationship between Islamist attacks in neighboring countries and the occurrence of an attack in a given focal country. However, the spatial lag of Google searches is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that when an Islamist attack occurs in a certain country, individuals in surrounding countries tend to increase their searches for sensitive keywords. More notably, when distinguishing between popular and extreme keywords, we find that the spatial lag for extreme words is not statistically significant in the global sample but becomes statistically significant and larger in magnitude when restricting the analysis to the subsample of countries that have previously experienced an Islamist attack. Overall, these findings highlight the role of geographic proximity in shaping online search behavior, particularly in regions with a history of Islamist terrorism.

When we expand our analysis, including temporal lags of the Google searches at time t − 1, we find that this does not substantially alter our main findings regarding contemporaneous Google searches and the lag of the dependent variable. The coefficient for Google searches in the previous month is positive and significant, suggesting that past search activity is positively associated with subsequent Islamist attacks. However, when we differentiate between popular and extreme keywords, we do not find any statistically significant effects. Notably, the significance of contemporaneous Google searches remains robust, particularly for extreme keywords.

Our finding that larger attacks–those resulting in a higher number of casualties and injuries–generate greater online interest aligns with recent evidence on the varying intensity of public responses to the severity of terrorist attacks (Bove, Efthyvoulou, and Pickard 2024; Efthyvoulou, Pickard, and Bove 2024). Specifically, Bove, Efthyvoulou, and Pickard 2024 have provided evidence that large-scale attacks elicit more prolonged public reactions, whereas the impact of smaller-scale incidents tends to fade within a month. Expanding on this, Efthyvoulou, Pickard, and Bove 2024 have documented that the emotional response to terrorism extends beyond immediate fear, reinforcing national identity–particularly when attacks involve a higher number of victims and are perpetrated by Islamic extremists–strengthening the sense of national belonging in the UK.

A key limitation of this analysis–shared by all studies that rely on Google searches to track hidden behaviors–is the inability to perform sentiment analysis. More broadly, obtaining individual–level insights into the motivations behind online searches or determining which specific websites users visit after receiving Google’s suggested results is impossible. Our approach allows us to track searches for sensitive keywords, such as “jihad,” but more explicit queries–like “how to join jihad,” “jihad is good,” or “fight against jihad” and “revenge against jihad”–generate search volumes too low to be reliably analyzed.

Consequently, our interpretation of the positive correlation between Google searches and terrorist attacks is inherently constrained and requires a degree of speculative reasoning. While we primarily interpret the increase in search volume as a reflection of heightened interest in terrorist activities, we cannot disentangle this effect from alternative explanations–such as the amplification of fear, as documented by Bove, Efthyvoulou, and Pickard (2024), or the activation of negative reciprocity mechanisms (Fehr and Gatcher 2010).

For instance, individuals may be motivated to search for terrorism-related content out of a desire for retaliation, potentially seeking ways to counteract terrorist interests through their actions. Unfortunately, the underlying sentiments driving these searches remain inaccessible and cannot be incorporated into any analysis based on Google Trends data.

A promising direction for future research could be to investigate the relationship between terrorist attacks and behaviors indicative of negative reciprocity, offering insights into whether the public exhibits a desire for retaliation in the aftermath of such events. While online searches explicitly linked to retaliatory intent are unlikely to generate search volumes large enough for systematic analysis, this line of inquiry could be extended to examine the potential impact of exposure to attacks on voting behavior. Specifically, future research could explore whether terrorist attacks lead to increased support for political parties advocating stronger counterterrorism measures–suggesting that electoral preferences may, at least in part, be shaped by a perceived need for retribution.

To date, evidence suggests that Israeli voters exposed to rocket attacks from the Gaza Strip tend to increase their support for right–wing parties (e.g., Getmanski and Zeitzoff 2014). However, systematic research on whether voters exhibit a similar retaliatory response to perceived threats in broader contexts–such as Western Europe and the U.S.–remains limited.

Another potential limitation is that Google may not be the primary search engine in some regions. However, incorporating this factor into our empirical analysis presents significant methodological challenges that would compromise the reliability of our estimates. The main issue is the lack of consistent and reliable statistics on the use of alternative search engines across countries during our study period (2004–2015). While available market share data indicate that Google was the dominant platform in most countries, we lack precise information on search engine preferences in regions where Google was less prevalent due to cultural or political factors, such as China and Russia.

Additionally, while Google search data are publicly accessible, the same does not apply to other platforms like Baidu or Yandex, making it impossible to assess whether search volumes for specific keywords follow similar patterns across different search engines. As a result, any analysis that interacts online searches with an index of Google usage in each country would be inherently unreliable. Addressing this issue in future research will depend on data availability, particularly from platforms operating in countries where government control over media and online information remains stringent.

While being aware of these limitations, which prevent further interpretation of the correlations we find, we believe our choice of using Google searches has some advantages. First, Google searches do track general interest in some keywords, with Google being the first landing page for almost all users when searching the web. Other platforms, e.g., Twitter, would not be as representative. Second, the SERP analysis by Ahmed and Lloyd George (2016) on the keywords we consider in the present analysis ensures that these terms are sensitive, as users can end up inadvertently on extremist online pages. Keeping in mind this caveat, the positive correlation we find is consistent with previous evidence suggesting that media coverage and celebrity encourage terrorists to plan new missions (Frey and Osterloh 2018; Jetter 2017, 2019; Jetter and Walker 2018). The significant and positive coefficient of the queries for the extreme keywords, on the other hand, supports the interpretation that online searches may detect not only the celebrity, but also the popularity of the extremist message. The spreading of curiosity and sympathy for radical Islam and violent extremism may signal the formation of a fertile ground for radicalization. The fact that, through search engines, guileless citizens and potential sympathizers easily come into contact with the jihadi propaganda may further nurture extremism triggering a cycle of radicalization.

Rearranging the keywords into different groups based on their meaning allows us to understand the relationship between the interest in Islamist extremism and the attacks more in depth. This part of the analysis reveals that attacks are more significantly and sizably associated to keywords evoking violent actions, such as “beheadings”, or explicitly related to the jihad, such as “Abdullah Azzam”. Beheading was a method of execution in pre-modern Islamic law. Jihadist organizations use beheading as a method of killing captives. Since 2002, groups such as Al Qaeda and ISIS have been mass broadcasting beheading videos as a form of propaganda (Campbell 2007). Abdullah Azzam was a Sunni scholar, also known as the “Father of Global Jihad” (Edwards 2017). Despite having laid the foundations of Al Qaeda and being considered as the spiritual mentor of Osama Bin Laden, Azzam is not as known to the general public as his disciple. He died assassinated in 1989, well before the first spectacular actions of Al Qaeda, and his name mostly circulates among researchers and sympathizers of the global jihad doctrine (Maliach 2010). The finding that the online searches for such specific keywords significantly correlate with the occurrence of Islamist attacks is striking and calls for a more profound investigation into the transmission mechanisms that could allow the popularity of extremist groups to turn into support and feed radicalization.

It is impossible to acquire individual-level information on the sentiments behind these searches or on the specific websites visited following Google’s suggestions in response to a given search. Consequently, our interpretation of the positive correlation between Google searches and terrorist attacks is limited in its scope. Nonetheless, our work contributes to the understanding of the relationship between terrorism and the public’s active interest in radical content. Previous studies suggest that media coverage of violent actions fuels further attacks by encouraging terrorists to plan new missions due to the increased public attention. Our approach provides a method to uncover public interest in violent extremism and demonstrates that people’s curiosity about terrorist messages is significantly associated with terrorist attacks. The correlation is even stronger for searches that likely indicate a propensity for violence and support for jihad. Measuring this attraction to extremist content could aid in detecting and potentially preventing the spread of sympathy for terrorist ideologies.

6 Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we propose a novel approach to examine the relationship between public interest in radical Islam and terrorist attacks. Our empirical analysis demonstrates a significant correlation between online searches for specific sensitive keywords and the occurrence of Islamist attacks. Using various model specifications, we show that Google searches for these keywords are positively correlated with terrorist attacks in a global panel spanning from 2004 to 2015. The magnitude of the estimated coefficient is also meaningful, as a one-standard-deviation increase in Google searches corresponds to a change in the Islamist attacks equivalent to approximately 12.4 % of its mean in the full sample and 14.3 % for the subsample of countries that have already experienced Islamist attacks.

By incorporating spatial lags into our DCCE estimation, we find that when an Islamist attack occurs in country i, individuals in neighboring countries tend to increase their searches for sensitive keywords. Moreover, when distinguishing between popular and extreme keywords, we observe that the spatial lag for extreme words is statistically significant only within the subsample of countries that have previously experienced an Islamist attack, underscoring the influence of geographic proximity on online search behavior, particularly in regions with a history of Islamist terrorism. Including temporal lags of the Google searches at time t − 1 does not substantially alter the main findings regarding contemporaneous Google searches and the lag of the dependent variable. The coefficient for Google searches in the previous month is positive and significant, suggesting that past search activity is positively associated with subsequent Islamist attacks.

Our findings contribute to the expanding literature on the interplay between media and terrorism. While previous studies have primarily focused on the role of social media and press coverage in terrorist activities, we broaden this perspective by emphasizing the importance of the general online landscape accessible through search engines. This study introduces a new method for detecting public interest in radical Islam and violent extremism. Existing literature indicates that terrorist attacks are more likely when terrorists anticipate significant media coverage, as public attention can help attract followers and foster radicalization among potential sympathizers (Nelson and Scott 1992). We reveal that public interest in radical Islam and violent extremism is systematically and robustly correlated with attacks committed by self-proclaimed Islamist groups.

Previous research on radicalization has predominantly focused on detecting jihadi propaganda on social networking sites. Our study highlights the necessity of also examining the decentralized dissemination of information across the World Wide Web. Monitoring the broader online landscape is crucial for detecting active public interest in extremist ideas. Understanding how interest in violent extremism spreads among Internet users is essential, not only because it measures public exposure to violent and illegal content but also because it may indicate a latent sympathy for terrorist ideologies that could facilitate radicalization. Given the established impact of media coverage on the popularity of terrorists, our results underscore the need for further investigation into the potential for a “cycle of violence.” If terrorists attack when interest in their ideologies is high, and these attacks subsequently amplify public attention, media coverage of terrorist actions could inadvertently strengthen the incentives to plan new violent initiatives.

A.1 Glossary

The definitions provided hereafter are sourced from the ARDA (Association of Religion Data Archives)[15] and Wikipedia, and are marked by an (A) and (W), respectively.

Abdullah Azzam: (1941–1989) also known as Father of Global Jihad, was a Palestinian Sunni Islamic scholar, theologian, and founding member of Al Qaeda. (W)

Amaq Agency: is a news outlet linked to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), it is often the “first point of publication for claims of responsibility by the group”. (W)

Apostasy: Departing or falling away from a religious faith. (A)

Apostates in Islam: Apostasy in Islam is commonly defined as the conscious abandonment of Islam by a Muslim in word or through deed. It includes the act of converting to another religion or non-acceptance of faith to be irreligious, by a person who was born in a Muslim family or who had previously accepted Islam. The definition of apostasy from Islam, and whether and how it should be punished are matters of controversy among Islamic scholars. (W)

Ayman al-Zawahiri: (1951–2022) has been the leader of Al Qaeda (assumed office in 2011). (W)

Caliphate: an Islamic state under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (Arabic: khalı̄fah), a person considered a religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of the entire ummah (community). (W)

Crusades: Medieval military campaigns of the eleventh through fifteenth centuries waged by Christians to recapture Jerusalem from Muslims. (A)

Dabiq Magazine: an online magazine used by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) for Islamic radicalization and recruitment. It was first published in July 2014 (until July 2016) in a number of different languages including English. (W)

Ibn Taymiyyah: (1263–1328) a medieval Sunni Muslim theologian. His iconoclastic views on widely accepted Sunni doctrines such as the veneration of saints and the visitation to their tomb-shrines made him unpopular with the majority of the orthodox religious scholars of the time, under whose orders he was imprisoned several times. He has become one of the most influential medieval writers in contemporary Islam, where his rejection of some aspects of classical Islamic tradition are believed to have had considerable influence on contemporary Wahhabism, Salafism, and Jihadism. His controversial fatwa allowing jihad against other Muslims is referenced by Al Qaeda and other jihadi groups. (W).

Inspire Magazine: an English language online magazine reported to be published by the organization Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) since 2010. (W)

Islamic State: a type of government primarily based on the application of shari’a (Islamic law), dispensation of justice, maintenance of law and order. From the early years of Islam, numerous governments have been founded as “Islamic”. However, the term “Islamic state” has taken on a more specific connotation since the 20th century. The concept of the modern Islamic state has been articulated and promoted by ideologues such as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Israr Ahmed or Sayyid Qutb. Like the earlier notion of the caliphate, the modern Islamic state is rooted in Islamic law. It is modeled after the rule of Muhammad. However, unlike caliph-led governments which were imperial despotisms or monarchies (Arabic: malik), a modern Islamic state can incorporate modern political institutions such as elections, parliamentary rule, judicial review, and popular sovereignty. (W)

Jihad: A term derived from Arabic that means “to struggle”. For Muslims, there are two types of Jihads: the greater struggle is the internal spiritual battle between the believer and his/her nature, and the lesser struggle is the physical battle against the enemies of Islam. Muslim extremists and critics of Islam emphasize jihad as a “holy war”, while most Muslims do not. (A)

Jewish Coalition: The Republican Jewish Coalition (RJC), formerly the National Jewish Coalition, founded in 1985, is a 501(c)(4) political lobbying group in the United States that promotes Jewish Republicans. The RJC is one of the most important voices on conservative political issues for the Jewish-American community. The organization has more than 47 chapters throughout the United States. (W)

Kafir: is an Arabic term meaning “infidel”, “rejector”, “disbeliever”, “unbeliever”, “nonbeliever”. The term refers to a person who rejects or disbelieves in God or the tenets of Islam, denying the dominion and authority of God, and is thus often translated as “infidel”. (W)

Khalifah: a name or title which means “successor”, “deputy” or “steward”. It most commonly refers to the leader of a Caliphate, but is also used as a title among various Islamic religious groups and orders. (W)

Khilafah: arabic word for Caliphate (see).

Kuffar: synonym of Kafir (see).

Martyr: In Judaism, Christianity and Islam, a martyr is someone who dies, typically premature and violently, for a sacred cause. During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, martyrdom became a terrorist strategy for suicide bombers in Israel, Iraq, the United States, and other countries. (A)

Mujahid (pl. Mujahideen): the term for one engaged in Jihad (literally, “struggle”). Its widespread use in English began with reference to the guerrilla-type military groups led by the Islamist Afghan fighters in the Soviet–Afghan War, and now extends to other jihadist groups in various countries. (W)

Shahada: is the profession of faith, one of the five pillars of Islam. A Muslim recites the following Islamic creed: “There is no God but God and Muhammad is the messenger of God”. (A)

Rafidah: is an Arabic word meaning “rejectors”, “rejectionists”, “those who reject” or “those who refuse”. The term is used contemporarily in a derogatory manner by Sunni Muslims, who refer to Shias as such because Shias do not recognize Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman as the legitimate successors of Muhammad, and hold Ali as to be the first successor. (W)

Suicide vest: an explosive belt (also called suicide belt); is an improvised explosive device, a belt or a vest packed with explosives and armed with a detonator, worn by suicide bombers. (W)

Taghut: an Islamic terminology denoting a focus of worship other than Allah. In traditional theology, the term often connotes idols, Satan and jinn. The term is also applied to earthly tyrannical power. The term may refer to any person or group accused of being anti-Islamic and an agent of Western cultural imperialism. The term was introduced to modern political discourse since the usage surrounding Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini during the 1979 Iranian Revolution, through accusations made both by and against Khomeini. (W)

A.2 Additional Tables

Religious ideology behind terrorist attacks (2004–2015).

| Religion | Freq. | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 359 | 1.03 % |

| Induism | 39 | 0.11 % |

| Islam | 21,711 | 62.20 % |

| Judaism | 64 | 0.18 % |

| Not religious | 12,710 | 36.41 % |

| Other | 24 | 0.07 % |

| Total | 34,907 | 100.00 % |

Definition of the alternative aggregations of GTs.

| ISIS | Amaq Agency, Caliphate, Dabiq, Dabiq Magazine, Dabiq Pdf, Islamic State. |

| Al Qaeda | Abdullah Azzam, Ayman al-Zawahiri, Inspire Magazine. |

| Infidels | Apostate Islam, Apostates in Islam, Kafir, Kuffar, Taghut. |

| Violent | Beheadings, How to do Jihad, Jihad, Jihad for Ummah, Jihad in the Quran, Killing Apostates, Killing Infidels, Killing Kuffar, Martyrdom in Islam, Mujahid, Mujahideen, Preparing for Jihad, Suicide vest. |

| Religion | Apostasy, Apostate, Apostates, Martyr, Martyrs. |

| History | Caliphate, Crusader, Crusaders, Jihad, Jihad meaning, Martyr, Martyrs. |

-

Each aggregation is obtained as the mean of Google Trends for the keywords listed, either in English or in Arabic.

References

Ahmed, M., and F. Lloyd George. 2016. A War of Keywords. How Extremists are Exploiting the Internet and What to Do About it. London, UK: Tech. rept. Centre for Religion & Geopolitics and Digitalis.Search in Google Scholar

Ajide, K. B., and O. Y. Alimi. 2020. “Natural Resource Rents, Inequality, and Terrorism in Africa.” Defence and Peace Economics 33 (6): 712–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1879412.Search in Google Scholar

Aly, Anne, Stuart Macdonald, Lee Jarvis, and Thomas Chen. 2016. Violent Extremism Online: New Perspectives on Terrorism and the Internet. New York, USA: Routledge.10.4324/9781315692029Search in Google Scholar

Arzaghi, M., and K. Gaibulloev. 2024. “Does Fiscal Decentralization Mitigate Domestic Terrorism?” Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 30 (3): 273–291, https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2024-0018.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, S. R., and A. Fradkin. 2017. “The Impact of Unemployment Insurance on Job Search: Evidence from Google Search Data.” Review of Economics and Statistics 99 (5): 756–68. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00674.Search in Google Scholar

Bassetti, T., R. Caruso, and F. Schneider. 2018. “The Tree of Political Violence: A GMERT Analysis.” Empirical Economics 54: 839–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-016-1214-1.Search in Google Scholar

Bentzen, J. S. 2019. “Acts of God? Religiosity and Natural Disasters across Subnational World Districts.” The Economic Journal 129 (622): 2295–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/uez008.Search in Google Scholar

Berger, T., C. Chen, and C. B. Frey. 2018. “Drivers of Disruption? Estimating the Uber Effect.” European Economic Review 110: 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.05.006.Search in Google Scholar

Bove, V., and T. Böhmelt. 2016. “Does Immigration Induce Terrorism?” Journal of Politics 2 (78): 572–88. https://doi.org/10.1086/684679.Search in Google Scholar

Bove, V., G. Efthyvoulou, and H. Pickard. 2024. “Are the Effects of Terrorism Short-Lived?” British Journal of Political Science 2 (54): 536–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123423000352.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, L. J. 2007. “The Use of Beheadings by Fundamentalist Islam.” Global Crime 7 (3–4): 586–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570601073384.Search in Google Scholar

Caruso, R., and F. Schneider. 2013. “Brutality of Jihadist Terrorism: A Contest Theory Perspective and Empirical Evidence in the Period 2002–2010.” Journal of Policy Modeling 35 (5): 695–6.10.1016/j.jpolmod.2012.12.005Search in Google Scholar

Chae, D. H., S. Clouston, M. L. Hatzenbuehler, M. R. Kramer, H. L. F. Cooper, S. M. Wilson, S. I. Stephens-Davidowitz, R. S. Gold, and B. G. Link. 2015. “Association between an Internet-Based Measure of Area Racism and Black Mortality.” PLoS One 10 (4): e0122963. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122963.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, H., and H. Varian. 2012. “Predicting the Present with Google Trends.” Economic Record 88 (S1): 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00809.x.Search in Google Scholar

Chitika, Insights. 2013. The Value of Google Result Positioning. Westborough: Chitika Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, S.-W., and J. A. Piazza. 2016. “Ethnic Groups, Political Exclusion and Domestic Terrorism.” Defence and Peace Economics 27 (1): 37–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2014.987579.Search in Google Scholar

Chudik, Alexander, and M. Hashem Pesaran. 2015. “Common Correlated Effects Estimation of Heterogeneous Dynamic Panel Data Models with Weakly Exogenous Regressors.” Journal of Econometrics 188 (2): 393–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2015.03.007.Search in Google Scholar

D’Amuri, Francesco, and Juri Marcucci. 2017. “The Predictive Power of Google Searches in Forecasting US Unemployment.” International Journal of Forecasting 33 (4): 801–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2017.03.004.Search in Google Scholar

Dickey, D. A., and W. A. Fuller. 1979. “Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 74 (366a): 427–31, https://doi.org/10.2307/2286348.Search in Google Scholar

Doleac, J. L., and L. C. D. Stein. 2013. “The Visible Hand: Race and Online Market Outcomes.” The Economic Journal 123 (572): F469–F492. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12082.Search in Google Scholar

Edwards, D. B. 2017. Caravan of Martyrs. Sacrifice and Suicide Bombing in Afghanistan. Oakland, California: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Efthyvoulou, G., H. Pickard, and V. Bove. 2024. “Terrorist Violence and the Fuzzy Frontier: National and Supranational Identities in Britain.” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewae003.Search in Google Scholar

Eksi, O., M. Y. Gurdal, and C. Orman. 2017. “Fines versus Prison for the Issuance of Bad Checks: Evidence from a Policy Shift in Turkey.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 143: 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

El Ouadghiri, I., and J. Peillex. 2018. “Public Attention to “Islamic Terrorism” and Stock Market Returns.” Journal of Comparative Economics 46 (4): 936–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2018.07.014.Search in Google Scholar

Fecht, F., S. Thum, and P. Weber. 2019. “Fear, Deposit Insurance Schemes, and Deposit Reallocation in the German Banking System.” Journal of Banking and Finance 105: 151–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.05.005.Search in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and S. Gatcher. 2010. “Fairness and Retaliation: The Economics of Reciprocity.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 3 (14): 159–81.10.1257/jep.14.3.159Search in Google Scholar

Feridun, M., and S. Sezgin. 2008. “Regional Underdevelopment and Terrorism: The Case of South Eastern Turkey.” Defence and Peace Economics 19 (3): 225–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690801972196.Search in Google Scholar

Frey, B. S., and M. Osterloh. 2018. “Strategies to Deal with Terrorism.” CESifo Economic Studies 64 (4): 698–711, https://doi.org/10.1093/cesifo/ifx013.Search in Google Scholar

Gentzkow, M. A., and J. M. Shapiro. 2004. “Media, Education and Anti-americanism in the Muslim World.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (3): 117–33. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330042162313.Search in Google Scholar

Getmanski, A., and T. Zeitzoff. 2014. “Ethnic Groups, Political Exclusion and Domestic Terrorism.” American Political Science Review 3 (108): 588–604.10.1017/S0003055414000288Search in Google Scholar

Giulietti, C., M. Tonin, and M. Vlassopoulos. 2019. “Racial Discrimination in Local Public Services: A Field Experiment in the United States.” Journal of the European Economic Association 17 (1): 165–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx045.Search in Google Scholar

Guriev, S., and N. Melnikov. 2016. “War, Inflation, and Social Capital.” American Economic Review 106 (5): 230–5. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161067.Search in Google Scholar

Harris, T. F., and A. Yelowitz. 2018. “Racial Climate and Homeownership.” Journal of Housing Economics 40: 41–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2017.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Helfstein, S. 2014. “Social Capital and Terrorism.” Defence and Peace Economics 25 (4): 363–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2013.763505.Search in Google Scholar

Im, Kyung So, M. Hashem Pesaran, and Yongcheol Shin. 2003. “Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels.” Journal of Econometrics 115 (1): 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(03)00092-7.Search in Google Scholar

Jetter, M. 2017. “The Effect of Media Attention on Terrorism.” Journal of Public Economics 153: 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.07.008.Search in Google Scholar

Jetter, M., and J. K. Walker. 2018. The Effect of Media Coverage on Mass Shootings. Bonn, Germany: IZA Discussion Paper No. 11900.10.2139/ssrn.3286159Search in Google Scholar