Abstract

Ion exchange membranes are widely used in chemical power sources, including fuel cells, redox batteries, reverse electrodialysis devices and lithium-ion batteries. The general requirements for them are high ionic conductivity and selectivity of transport processes. Heterogeneous membranes are much cheaper but less selective due to the secondary porosity with large pore size. The composition of grafted membranes is almost identical to heterogeneous ones. But they are more selective due to the lack of secondary porosity. The conductivity of ion exchange membranes can be improved by their modification via nanoparticle incorporation. Hybrid membranes exhibit suppressed transport of co-ions and fuel gases. Highly selective composite membranes can be synthesized by incorporating nanoparticles with modified surface. Furthermore, the increase in the conductivity of hybrid membranes at low humidity is a significant advantage for fuel cell application. Proton-conducting membranes in the lithium form intercalated with aprotic solvents can be used in lithium-ion batteries and make them more safe. In this review, we summarize recent progress in the synthesis, and modification and transport properties of ion exchange membranes, their transport properties, methods of preparation and modification. Their application in fuel cells, reverse electrodialysis devices and lithium-ion batteries is also reviewed.

Introduction

Energy is among the oldest and simultaneously most demanded products. None of modern production processes nor human everyday life would be possible without energy. The energy demand doubles every 30 years [1]. In addition, the mankind enters every new century with a new major energy source. Today the question is of what will be the major energy source by the 22nd century. This seems to be renewable energy sources such as solar batteries, wind generators, and tidal energy [2], [3], [4]. However, these sources cannot operate continuously. Therefore, energy storage devices are needed to maintain the energy supply. Among these devices, metal-ion batteries, redox batteries, and the hydrogen cycle based on fuel cells [5], [6], [7], [8], [9] are the most promising. In a certain sense, fuel cells can be considered as a primary or even a renewable energy source, when hydrogen obtained via reforming of natural gas [10], biomass [11], [12], [13], [14], or biomass-derived alcohols [15], [16], [17] is used as the fuel.

Ion exchange membrane is the necessary component in all these devices. It should provide directed transport of protons or metal cations driven by electrochemical potential gradient and prevent the transport of electrons, fuel, and oxidants [3]. Therefore, a desired membrane should exhibit high ionic conductivity and selectivity. Meanwhile, new energy sources have been developed also. For example, reverse electrodialysis based on the energy of mixing of fresh and salt water has received considerable attention in recent years [18], [19], [20]. This may seem not quite reasonable, since numerous desalination plants using reverse osmosis [21] or electrodialysis [22] are installed, which provide strictly opposite processes. However, rivers inevitably run into the seas and it appears pertinent to use this process for the design of a renewable energy source [23]. The use of reverse electrodialysis is not always expedient because of the high cost of water pretreatment needed to maintain the power density. Therefore, an alternative way is to integrate reverse electrodialysis into the existing power systems for additional energy generation [24], [25], [26]. The ion exchange membranes used in reverse electrodialysis should also have high ionic conductivity, selective transport of ions of one sign, and low electronic conductivity [27].

In this review, we summarize recent progress in the synthesis and modification of ion-exchange membranes, their transport properties, methods of preparation and modification. Their application in fuel cells and lithium-ion batteries is also reviewed.

Perfluorinated ion exchange membranes

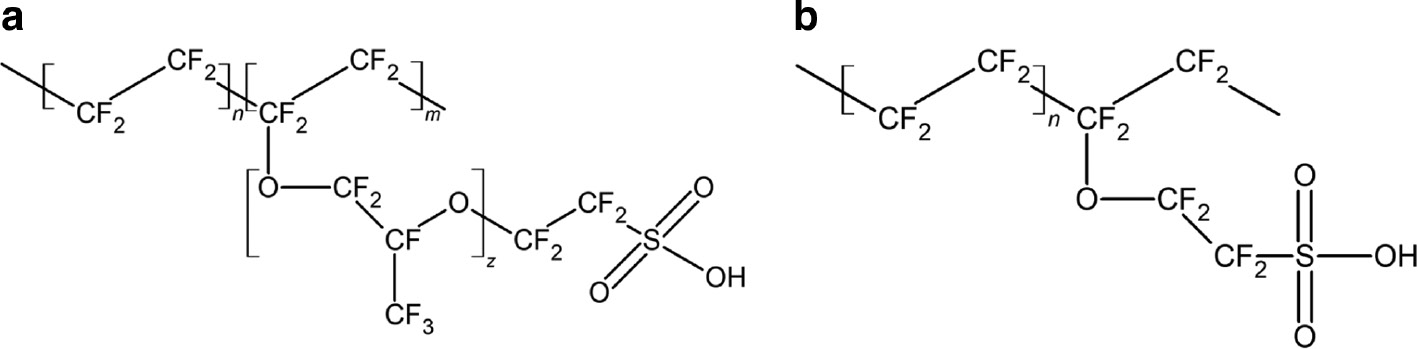

Perfluorinated cation exchange membranes are most often used in fuel cells due to high chemical stability, conductivity, and selectivity [28], [29], [30]. This set of properties are determined by their chemical structure (Fig. 1). The perfluorinated chains are responsible for the thermal and chemical stability of membranes, while the –SO3H functional groups determine their ion-exchange and conductive properties [31]. Other functional groups such as –PO3H and –COOH are introduced into cation exchange membranes much more rarely [31], [32], [33], [34]. Anion exchange membranes usually contain different –NR3 alkylammonium moieties as functional groups [35], [36], [37].

Chemical structure of perfluorinated cation exchange membranes with a long (Nafion®, а) and short (Aquivion®, b) side chains.

The most extensively studied Nafion® membranes are composed of a polytetrafluoroethylene backbone with perfluoropolyether side chains terminated by sulfonate groups (Fig. 1а) [38], [39]. It is noteworthy that relatively few studies are devoted to the synthesis of these membranes. The first stage of this synthesis is the copolymerization of tetrafluoroethylene and perfluorovinyl ether with sulfonyl acid fluoride [40], [41], [42], [43], [44] in a fluorocarbon solvent using radical initiators [45], [46]. The process stops at the conversion degree of 20–25% because of considerable rise of viscosity. In some cases, copolymerization is carried out in aqueous emulsions [47]. Recently, the preparation of such polymers at high pressure has been reported [48]. The membranes can be extruded from a polymer melt or cast from a solution. After that, they are subjected to alkaline hydrolysis and are finally converted to the proton form by treatment with acid followed by washing.

The functional groups are located on relatively long side chains. Their segmental mobility induces self-organization in the membrane; as a result, hydrophobic perfluorinated chains form the membrane matrix, while hydrophilic sulfonate groups are arranged into clusters [35], [49], [50]. On contact with the surrounding moistened gas or solution, these clusters actively absorb water, thus being increased in size and form pores filled with water. Usually on contact with water, membranes with equivalent weight of about 1300 g/mol and ion exchange capacity of about 1 mg-equiv./g absorb up to 17–18 water molecules per functional group [31], [51]. The functional groups dissociate almost completely. The fixed –SO3 − groups impart a negative charge to pore (cluster) walls, while the cations pass to the aqueous solution inside the pores, thus providing the ionic conductivity. When hydrated, the characteristic size of membrane pore is 4–5 nm. The ion transport across the membrane prompts the idea that the pores are interconnected by more narrow channels (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that this cluster-channel or cluster-network model was developed for Nafion® membranes [52], [53], but it is usually extended to all ion exchange membranes [35].

![Fig. 2:

Scheme of cluster-channel or cluster-network system in the cation exchange membrane. (1) membrane matrix consisting of perfluorinated chains, (2) functional –SO3

− groups, (3) Debye layer, (4) electrically neutral solution [54].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1208/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1208_fig_002.jpg)

Scheme of cluster-channel or cluster-network system in the cation exchange membrane. (1) membrane matrix consisting of perfluorinated chains, (2) functional –SO3 − groups, (3) Debye layer, (4) electrically neutral solution [54].

As a result of electrostatic interactions with negatively charged pore walls, most of the cations (counter-ions) are concentrated in a thin (about 1–2 nm) Debye layer near the membrane pore wall (Fig. 2). This layer is responsible for the ionic conductivity of membranes in contact with water or water vapor [55]. At the pore center, there is a so-called “electrically neutral solution” with a slight excess of counter-ions. Usually it is assumed that its composition is close to that of the solution contacting with the membrane [56] which can contribute to the membrane conductivity. However, in this case, there are co-ions (anions) at the pore centers which provide low anionic conductivity of cation exchange membrane. The selectivity of transport processes is expressed as the transport numbers (the fraction of the total electrical current carried by ions of the given charge) [30], [57].

Membranes used in a fuel cell contact with the water vapor only. In this case, it can be assumed that the electrically neutral solution contains no anions and the liquid inside the pores is presented by pure water. However, water can dissolve gases or methanol feeding the cell. This determines the possibility of their transport across the membrane without energy generation (crossover) [58], [59]. In this case, the selectivity is characterized by the ratio of the transport rate of these molecules to the membrane conductivity.

The presence of pure water inside the pores for membranes with high water uptake is confirmed by the endothermic peak of water crystallization near 0°C on the DSC-curves [60]. However, this crystallization can be observed only at high water uptake. For example, for the H+-form of the membrane, it should be more than 18–20 water molecules per sulfonate group [61]. So high water uptake was attained for grafted membranes based on polyethylene and sulfonated polystyrene. Meanwhile, for a large majority of perfluorinated membranes, water uptake is much lower. Even if there is a small amount of almost pure water in the pore centers, this water freezes markedly below 0°C due to a low nucleus radius.

In recent years, considerable attention has been paid to the Aquivion type membranes with short side chains (Fig. 1b), which have high conductivity and selectivity [62], [63], [64]. However, a comparative study of the Nafion® and Aquivion® perfluorinated membranes [65] demonstrates that the major advantages of short side-chain membranes are mainly due to lower equivalent weight. At the moment, their cost is about 1.5 times higher than that of the Nafion membranes with the same thickness. Moreover, some membranes of this type have lower selectivity at a high conductivity [66]. It is possible, however, that this is determined by the preparation method.

Grafted membranes

A very high cost limits application of perfluorinated membranes [67]. Therefore, heterogeneous membranes containing ion-exchange resins (e.g. polystyrene sulfonate) and an inert binder, most often polyethylene, are much more popular [35]. They are usually obtained by hot rolling or pressing. Therefore, these membranes contain an additional system of larger pores (secondary porosity) with the size about 1 μm and have a bimodal pore size distribution [68]. These pores can contain much more co-ions or dissolved molecules. The contribution of the conductive Debye layer to the volume of such pores is negligibly low. Therefore, heterogeneous membranes are usually less selective [69], [70]. Recently, another reason for the low selectivity of heterogeneous membranes was also shown [71]. Large pores can be formed at the contacts of the reinforcing fabric with ion-exchange material. The situation is worse when there are protrusions of the fabric filaments above the surface. In this case, the relatively great length of these non-selective open-ended macropores allows easy transport of co-ions from the external solution into the membrane depth.

An appealing idea is to design ion exchange membranes similar to heterogeneous ones in their composition, but devoid of macroporosity. This approach can be implemented by graft polymerization of vinyl monomers on irradiated polymer films [72], [73]. For example, γ-irradiation of a polyethylene film results in the radical generation. Usually, the radicals have short lifetimes, but in a polymer film they are stabilized because of low mobility. Therefore, grafting can be carried out even several months after irradiation. Grafting is accomplished by immersion of the irradiated film into the monomer and is associated with radical copolymerization. Most often, grafted ion exchange materials are synthesized using styrene, which readily undergoes further chemical modification [74]. Grafted styrene polymerizes in the poreless membrane matrix, thus pushing its chains apart, which prevents the formation of the secondary “macroporosity”, usually observed in heterogeneous membranes. The subsequent sulfonation of polystyrene gives highly acidic cation exchange membranes with a broad range of ion exchange capacities and water uptakes [61], [75], [76]. A method has been proposed for the synthesis of ion exchange membranes based on polymethylpentene [77] containing a large number of tertiary carbon atoms in the polymer structure. In this case, UV radiation can be used for activation instead of γ-radiation, which makes the synthesis of grafted materials much simpler. In addition, divinylbenzene cross-linking can be carried out for both methods, which allows targeted control over the membrane selectivity and solvation degree [78], [79]. The designed grafted films based on styrene copolymer with UV-activated polymethylpentene were used for the synthesis of highly alkaline anion exchange membranes using chloromethylation and quaternization [80].

In order to compare the conductivity and selectivity of the obtained membranes with those of commercial samples, the potentiometric transport numbers were plotted versus ionic conductivity of membranes under equivalent conditions [78], [81]. It can be seen from the data presented in Fig. 3a that the cation exchange membranes obtained by graft polymerization match the best homogeneous perfluorinated membranes [78]. Fairly high characteristics were also attained for the anion exchange membranes based on graft copolymers of polystyrene with UV-irradiated polymethylpentene (Fig. 3b) [79].

![Fig. 3:

Selectivity versus ionic conductivity for various cation exchange (a) and anion exchange (b) membranes: (1) membranes based on functionalized polystyrene–polymethylpentene graft copolymer; (2) homogeneous and pseudo-homogeneous commercial membranes; (3) heterogeneous commercial membranes; (4) cation exchange membranes based on sulfonated polystyrene–polyethylene graft copolymer [77], [79].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1208/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1208_fig_003.jpg)

Selectivity versus ionic conductivity for various cation exchange (a) and anion exchange (b) membranes: (1) membranes based on functionalized polystyrene–polymethylpentene graft copolymer; (2) homogeneous and pseudo-homogeneous commercial membranes; (3) heterogeneous commercial membranes; (4) cation exchange membranes based on sulfonated polystyrene–polyethylene graft copolymer [77], [79].

An alternative approach to the preparation of ion exchange membranes is associated with polymer film stretching, resulting in the formation of numerous small pores [82]. A broad range of polymers, including polyethylene, polyvinylidene fluoride, and even Teflon were treated [83]. This approach cannot prevent the secondary porosity; however, the membranes based on stretched polymer film exhibit high conductivity and selectivity [84], [85].

Modification of membrane materials

A promising approach to produce new membrane materials with improved performance involves modification of commercially available membranes. This can be done by surface treatment, including profiling [85], [86] or surface deposition of other materials [57]. In particular, studies describing successive deposition of thin layers of anionic and cationic polyelectrolytes on the surface have become popular over the past couple of years. This gives membranes with high fouling resistance and selectivity for cations of different charge [57], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92].

A widely used approach is the formation of inorganic-organic hybrid or composite membranes. There are several reviews discussing this method [93], [94], [95], [96], [97]. Initially, studies in this field were aimed at increasing the conductivity of membranes for fuel cells [98], [99], [100], [101]. Synthesis of a small amount of inorganic additives directly in the membrane pores is the most efficient [102], [103]. According to the limited elasticity model, pores are expanded upon nanoparticle incorporation, which leads to simultaneous expansion of the channels that connect the pores and determine the membrane conductivity [104]. As the additive concentration increases, its particles are enlarged. The force needed for further pore expansion increases according to the Hooke law. Therefore, the osmotic pressure created by the cations in the pore solution is insufficient for efficient pore expansion. This results in decrease in the membrane water uptake and conductivity [104].

Incorporation of nanoparticles with acidic surface seems to be more favorable. It should contribute to the membrane conductivity by the formation of additional charge carriers as well as increase in the membrane water uptake due to their hydrophilic surface [54], [95], [105], [106]. Furthermore, negative charge formation near the surface of these particles may result in the second Debye layer formation. It would increase the membrane selectivity as a result of displacement of anions and non-polar gas molecules from the pores [7]. This was observed for acid salts of heteropolyacids incorporated in the membrane pores [105], [107]. Meanwhile, selectivity can also increase upon incorporation of particles with basic surface due to the formation of strong hydrogen or coordination bonds between them and the membrane functional groups. This should markedly decrease the membrane water uptake and, hence, decrease the volume of electrically neutral solution at the pore centers and increase the membrane selectivity [108].

The effect of inorganic filler surface acidity was studied for polymethylpentene-based membranes with grafted polystyrene sulfate containing ZrO2, TiO2, and SiO2 nanoparticles with increasing acid properties [109]. Upon SiO2 incorporation, the ion exchange capacity is retained while the conductivity increases. However, simultaneously with increasing water uptake, the selectivity decreases. Dissociation of slightly acidic silica surface is suppressed by the –SO3H group dissociation and the second Debye layer does not form. On going to TiO2 and especially to ZrO2, the ion exchange capacity and conductivity of membranes substantially drop. However, the membrane selectivity markedly increases. Thus, incorporation of basic oxides acts similarly to membrane cross-linking with simultaneous decrease in the ion exchange capacity [109]. A similar effect is induced by modification with basic polyelectrolytes [110]. Low gas [111] and alcohol [112] permeability were noted among the advantages of hybrid membranes in many studies.

Usual membranes rapidly lose conductivity at low humidity because of dehydration and decrease in the size of pores and channels [113]. At the same time, the conductivity of hybrid membranes is often much higher [95]. For example, the conductivity of the perfluorinated MF-4SK membranes containing SiO2 and heteropolyacid is 2.5 orders of magnitude higher than that of the initial material [105].

Application of ion exchange membranes in power generation

Among the applications of ion exchange membranes in modern power generation, fuel cells (FCs) should be mentioned, first of all. A majority of commercial fuel cells are based on proton-conducting ion exchange membranes [3]. As noted above, this area is mainly occupied by perfluorinated sulfonated cation exchange membranes [114], which have high conductivity, selectivity, and chemical stability [62]. Fuel cells based on the Aquivion® type membranes show higher transport performance and allow operation at temperatures up to 130°C [65], [115]. The absence of an ester group and tertiary carbon in the side chain provide a better chemical stability and strength of the membranes. Moreover, lower gas permeability of these membranes was also highlighted [115].

Composite membranes have shown considerable benefits for applications [116], [117]. Improved fuel cell performance is due to their higher conductivity [118], lower gas permeability [111], and/or possibility of operation at elevated temperatures [119]. The latter issue is very important, as the platinum catalysts used in fuel cells irreversibly sorb CO, which is inevitably present in the relatively cheap hydrogen produced by natural gas or alcohol reforming [120]. At temperatures above 120°C this problem is much less severe [28]. However, data on the hybrid membrane application at high temperatures are scarce, and this advantage looks questionable. Many authors noted lower methanol permeability of hybrid membranes when used in direct methanol FCs [121], [122], [123], [124].

Among the fluorine-free membranes used in fuel cells, sulfonated poly(ether ether ketones) are noteworthy [125], [126], [127]. The interest in these compounds is mainly caused by their low cost. Therefore, poly(ether ether ketones) are often used to develop methods for membrane modification [128], [129], [130]. The practical interest in these materials is rather low, because of their relatively low stability.

Membranes based on polybenzimidazoles and polyarylenes are more promising. These materials have high thermal stability and can operate at temperatures up to 200°C [131]. However, their anion-exchange groups are weakly basic and conductivity of these membranes is relatively low. For the use in fuel cells, these membranes are doped with phosphoric acid [132], [133], [134], [135], which gives charge carriers and plays the same role as water in sulfonated cation exchange membranes. It forms the conduction system, providing the proton transport by Grotthuss mechanism [136]. Most likely, charge carriers are proton vacancies (H2РO4 − ions), which are formed upon proton hopping from phosphoric acid to the nitrogen atom of polybenzimidazole matrix. Therefore, these membranes are not prone to desolvation, and their operation temperature is restricted by stability of their matrix. Their main drawback is washing out of phosphoric acid during fuel cell operation, and poor mechanical properties in the solvated state at high temperatures. In addition, high corrosivity of phosphoric acid solution formed during FC operation imposes strict requirements to materials used for FC fabrication. The introduction of inorganic nanoparticles rarely increases the conductivity of polybenzimidazoles, because they themselves are, in essence, a good “dopant” for phosphoric acid. More often, the introduction of fillers prevents washing out of phosphoric acid [132]. Also, if additional nitrogen-containing basic groups are grafted onto the filler surface, the material sorbs an additional amount of phosphoric acid, which increases the conductivity [137].

Membranes composed of polymer matrices based on stretched polyvinylidene fluoride, ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, and polypropylene with polystyrene sulfate-filled pores also showed good fuel cell performance [84]. However, they can hardly be used in FC applications due to relatively low oxidative stability as well as grafted membranes described above. Meanwhile, owing to their high transport characteristics, grafted membranes are promising in reverse electrodialysis units, which generate electricity by mixing fresh and salt water [73]. The electricity generation with the use of RED is financially feasible if the membrane cost is below 4.3 €/m2 [138]. As far as we know, there are no commercially available grafted ion-exchange membranes. It is difficult to compare their cost with those of the homogeneous or pseudo-homogeneous membranes used in reverse electrodialysis plants today. At a present price of several tens of dollars per square meter of membrane, the financial viability of the RED process is determined by its efficiency, which is higher for grafted membranes because of their higher selectivity.

Nowadays, liquid electrolytes based on aprotic organic solvents and lithium salts with bulky anions are most often used in metal-ion batteries [139], [140]. However, they tend to be reduced during cycling to form a film, which increases the internal battery resistance and decreases its efficiency. One more problem is a sharp decrease in the conductivity due to electrolyte freezing or a pronounced increase in its viscosity at low temperatures [141]. Furthermore, when lithium metal is used as the anode, its dendrites may grow through the electrolyte, leading to a short circuit. Therefore, in recent years, considerable research has been focused on the application of ion exchange membranes as electrolytes for lithium – [142], [143] and sodium-ion batteries [144]. In this case, membranes are used in the lithium or sodium form, respectively, and are solvated by organic solvents or their mixtures. This results in high conductivity of electrolytes, in particular, at low temperatures [145].

Efficient hydrogen production from biomass or alcohols is a basic problem for the use of fuel cells as a renewable energy source in the hydrogen cycle [11]. Also, as noted above, low-temperature FC application requires high-purity hydrogen, which can be produced by filtration through metallic membranes based on palladium alloys [146], [147]. One problem is the relatively low throughput of these membranes. The permeability can be increased by using thin films of palladium alloys deposited on a thin ceramic substrate, which ensures their strength [146], [147], [148].

Membranes based on non-precious metals, first of all, vanadium [149], [150], and porous non-metallic membranes [151], [152] are being actively developed. Although the last ones do not provide sufficient hydrogen purity. A promising method is the use of membrane catalysis processes in which hydrogen is produced from biomass [11] or alcohols on the same palladium alloy membranes [120], [147], [153], [154]. This not only gives high-purity hydrogen, but can also increase the conversion above the equilibrium value as a result of removal of one reaction product [155]. High-purity hydrogen can be obtained by electrolysis also [156].

Certainly, the above does not exhaust the potential applications of ion exchange membranes. Various types of redox flow batteries are developed [157], [158]. Electrodialysis units based on heterogeneous [159], [160], [161], in particular hybrid, membranes [162] are widely used for water desalination or preconcentration of solutions. Perfluorinated membranes are used for chlorine production by electrolysis [163], for sensors [164], [165], and for some other applications [166], [167]. However, these issues are beyond the scope of this review.

Conclusions

Among the currently used ion exchange membranes, the best transport properties are demonstrated by homogeneous materials based on perfluorosulfonic acids, distinguished by high conductivity and selectivity. However, Nafion® type membranes are expensive; furthermore, temperature rise and decrease in the water uptake lead to a sharp drop in their conductivity, which has a detrimental effect on the performance of devices using these membranes. Thus, substantial efforts are currently devoted to the alternative material development. Development of membranes with a short side chain is in progress. Among the alternative membrane materials that are developed, mention should be made of polybenzimidazoles, which are distinguished by high thermal stability.

A drawback of cheaper heterogeneous membranes is low selectivity caused by features of their microstructure. However, grafted membranes, with composition being close to that of some heterogeneous membranes, are much more selective.

Membrane modification by nanoparticle incorporation can result, in some cases, in a considerable improvement of a number of membrane properties, among which one can mention increase in the proton conductivity and transport selectivity. This determines the possibility of a broad practical use of hybrid membranes for the design of electrochemical devices with improved performance.

Funding: This work in part of sections “Perfluorinated ion exchange membranes” and “Grafted membranes” was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 17-79-30054), other parts were supported by IGIC RAS state assignment.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry (Mendeleev-21), held in Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation, 9–13 September 2019.

References

[1] J. E. Girard. Principles of Environmental Chemistry, p. 712, Burtlett, Burlington, USA (2014).Suche in Google Scholar

[2] J. Widén, N. Carpman, V. Castellucci, D. Lingfors, J. Olauson, F. Remouit, M. Bergkvist, M. Grabbe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 44, 356 (2015).10.1016/j.rser.2014.12.019Suche in Google Scholar

[3] A. B. Yaroslavtsev, I. A. Stenina, T. L. Kulova, A. M. Skundin, A. V. Desyatov. in Comprehensive Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, D. L. Andrews, R. H. Lipson, T. Nann, (Eds.), V.5 Application of Nanoscience, D. S. Bradshaw (Ed.), pp. 165–206, Elsevier, Academic Press, Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York, Oxford, Paris, San Diego, San Francisco, Singapore, Sydney, Tokio (2019).10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.10426-6Suche in Google Scholar

[4] N. Pearre, K. Adye, L. Swan. Appl. Energy. 242, 69 (2019).10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.03.073Suche in Google Scholar

[5] F. Zhang, P. Zhao, M. Niu, J. Maddy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 41, 14535 (2016).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.05.293Suche in Google Scholar

[6] M. Kaur, K. Pal. J. Energy Storage. 23, 234 (2019).10.1016/j.est.2019.03.020Suche in Google Scholar

[7] I. A. Stenina, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Pure Appl. Chem. 89, 1185 (2017).10.1515/pac-2016-1204Suche in Google Scholar

[8] A. R. Dehghani-Sanij, E. Tharumalingam, M. B. Dusseault, R. Fraser. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 104, 192 (2019).10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.023Suche in Google Scholar

[9] P. Arévalo, D. Benavides, J. Lata-García, F. Jurado. Sustain. Cities Soc. 52, 101773 (2020).10.1016/j.scs.2019.101773Suche in Google Scholar

[10] N. L. Basov, M. M. Ermilova, N. V. Orekhova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. Chem. Rev. 82, 352 (2013).10.1070/RC2013v082n04ABEH004324Suche in Google Scholar

[11] M. Ni, D. Y. C. Leung, M. K. H. Leung, K. Sumathy. Fuel Process. Technol. 87, 461 (2006).10.1016/j.fuproc.2005.11.003Suche in Google Scholar

[12] M. V. Tsodikov, O. V. Arapova, G. I. Konstantinov, O. V. Bukhtenko, J. G. Ellert, S. A. Nikolaev, A. Y. Vasil’kov. Chem. Eng. J. 309, 628 (2017).10.1016/j.cej.2016.10.031Suche in Google Scholar

[13] A. Mudhoo, P. C. Torres-Mayang, T. Forster-Carneiro, P. Sivagurunathan, G. Kumar, D. Komilis, A. Sánchez. Waste Manage. 79, 580 (2018).10.1016/j.wasman.2018.08.028Suche in Google Scholar

[14] B. Pandey, Y. K. Prajapati, P. N. Sheth. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 44, 25384 (2019).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.08.031Suche in Google Scholar

[15] A. A. Lytkina, N. V. Orekhova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Inorg. Mater. 54, 1315 (2018).10.1134/S0020168518130034Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Y. Gao, J. Jiang, Yu. Meng, F. Yan, A. Aihemaiti. Energy Convers. Manage. 171, 133 (2018).10.1016/j.enconman.2018.05.083Suche in Google Scholar

[17] A. A. Lytkina, N. V. Orekhova, M. M. Ermilova, I. S. Petriev, M. G. Baryshev, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 44, 13310 (2019).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.03.205Suche in Google Scholar

[18] K. Nijmeijer, S. Metz. Sustain. Sci. Eng. 2, 95 (2010).10.1016/S1871-2711(09)00205-0Suche in Google Scholar

[19] A. B. Ribeiro, E. P. Mateus, N. Couto. in Electrokinetics Across Disciplines and Continents. New Strategies for Sustainable Development, A. B. Ribeiro, E. P. Mateus, N. Couto (Eds.), pp. 57–80, Springer, Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London (2015).10.1007/978-3-319-20179-5Suche in Google Scholar

[20] R. A. Tufa, S. Pawlowski, J. Veerman, K. Bouzek, E. Fontananova, G. di Profio, S. Velizarov, J. G. Crespo, K. Nijmeijere, E. Curcio. Appl. Energy. 225, 290 (2018).10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.04.111Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Y. Zhang, T. Rottiers, B. Meesschaert, L. Pinoy, B. Van der Bruggen. in Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes, A. Basile, A. Cassano, A. Figoli (eds.), pp. 1–19, Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam (2018).10.1016/B978-0-12-813545-7.00001-5Suche in Google Scholar

[22] A. Campione, L. Gurreri, M. Ciofalo, G. Micale, A. Tamburini, A. Cipollina. Desalination. 434, 121 (2018).10.1016/j.desal.2017.12.044Suche in Google Scholar

[23] A. Daniilidis, D. A. Vermaas, R. Herber, K. Nijmeijer. Renew. Energy. 64, 123 (2014).10.1016/j.renene.2013.11.001Suche in Google Scholar

[24] A. Tamburini, M. Tedesco, A. Cipollina, G. Micale, M. Ciofalo, M. Papapetrou, W. Van Baak, A. Piacentino. Appl. Energy. 206, 1334 (2017).10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.10.008Suche in Google Scholar

[25] R. A. Tufa, J. Hnát, M. Němeček, R. Kodým, E. Curcio, K. Bouzek. J. Cleaner Prod. 203, 418 (2018).10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.269Suche in Google Scholar

[26] M. Vanoppen, E. Criel, G. Walpot, D. A. Vermaas, A. Verliefde. npj Clean Water. 1, 9 (2018).10.1038/s41545-018-0010-1Suche in Google Scholar

[27] E. Güler, R. Elizen, D. A. Vermaas, M. Saakes, K. Nijmeijer. J. Membr. Sci. 446, 266 (2013).10.1016/j.memsci.2013.06.045Suche in Google Scholar

[28] A. B. Yaroslavtsev, Y. A. Dobrovolsky, L. A. Frolova, E. V. Gerasimova, E. A. Sanginov, N. S. Shaglaeva. Russ. Chem. Rev. 81, 191 (2012).10.1070/RC2012v081n03ABEH004290Suche in Google Scholar

[29] J. Ran, L. Wu, Y. He, Zh. Yang, Y. Wang, Ch. Jiang, L. Ge, E. Bakangura, T. Xu. J. Membr. Sci. 522, 267 (2017).10.1016/j.memsci.2016.09.033Suche in Google Scholar

[30] I. A. Stenina, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Inorg. Mater. 53, 253 (2017).10.1134/S0020168517030104Suche in Google Scholar

[31] A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Polym. Sci. Ser. A. 55, 674 (2013).10.1134/S0965545X13110060Suche in Google Scholar

[32] J. E. Hensley, J. D. Way. J. Power Sources. 172, 57 (2007).10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.12.014Suche in Google Scholar

[33] V. I. Volkov, E. V. Volkov, S. V. Timofeev, E. A. Sanginov, A. A. Pavlov, E. Y. Safronova, I. A. Stenina, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 55, 318 (2010).10.1134/S0036023610030022Suche in Google Scholar

[34] C. Alter, B. Neumann, H. Stammler, B. Hoge. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 48235 (2019).10.1002/app.48235Suche in Google Scholar

[35] V. V. Nikonenko, A. B. Yaroslavtsev, G. Pourcelly. in Ionic Interactions in Natural and Synthetic Macromolecules, A. Ciferri, A. Perico (Eds.), pp. 267–335, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey (2012).10.1002/9781118165850.ch9Suche in Google Scholar

[36] M. A. Vandiver, S. Seifert, M. W. Liberatore, A. M. Herring. ECS Trans. 50, 2119 (2013).10.1149/05002.2119ecstSuche in Google Scholar

[37] A. G. Divekar, N. C. Buggy, P. J. Dudenas, A. Kusoglu, S. Seifert, B. S. Pivovar, A. M. Herring. ECS Trans. 92, 715 (2019).10.1149/09208.0715ecstSuche in Google Scholar

[38] K. A. Mauritz, R. B. Moore. Chem. Rev. 104, 4535 (2004).10.1021/cr0207123Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] R. Souzy, B. Ameduri. Prog. Polym. Sci. 30, 644 (2005).10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2005.03.004Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Perfluorinated Ionomer Membranes, A. Eisenberg, H. L. Yeager (Eds.), p. 500, Am. Chem. Soc., Washington (1982).Suche in Google Scholar

[41] S. S. Ivanchev, S. V. Myakin. Russ. Chem. Rev. 79, 101 (2010).10.1070/RC2010v079n02ABEH004070Suche in Google Scholar

[42] S. S. Ivanchev, V. S. Likhomanov, O. N. Primachenko, S. Ya. Khaikin, V. G. Barabanov, V. V. Kornilov, A. S. Odinokov, Y. V. Kulvelis, V. T. Lebedev, V. A. Trunov. Pet. Chem. 52, 453 (2012).10.1134/S0965544112070067Suche in Google Scholar

[43] O. Gronwald, N. Uematsu, N. Hoshi, M. Ikeda, J. Yamaki. J. Fluorine Chem. 129, 535 (2008).10.1016/j.jfluchem.2008.04.002Suche in Google Scholar

[44] M. Colpaert, M. Zatoń, G. Lopez, D. J. Jones, B. Améduri. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 43, 16986 (2018).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.03.153Suche in Google Scholar

[45] A. S. Odinokov, O. S. Bazanova, L. F. Sokolov, V. G. Barabanov, S. V. Timofeev. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 82, 112 (2009).10.1134/S1070427209010212Suche in Google Scholar

[46] M. Yandrasits, S. Hamrock. in Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference, K. Matyjaszewski, M. Möller (Eds.), pp. 601–619, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2012).10.1016/B978-0-444-53349-4.00283-1Suche in Google Scholar

[47] S. J. Hamrock, L. M. Rivard, G. G. I. Moore, H. T. Freemyer. US Patent 7348088, Filed 19 December 2002, Issued 24 June 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] E. V. Polunin, Y. E. Pogodina, I. A. Prikhno, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mendeleev Commun. 29, 661 (2019).10.1016/j.mencom.2019.11.019Suche in Google Scholar

[49] S. P. Fernandez Bordín, H. E. Andrada, A. C. Carreras, G. E. Castellano, R. G. Oliveira, V. M. Galvan Josa. Polym. 155, 58 (2018).10.1016/j.polymer.2018.09.014Suche in Google Scholar

[50] S. Fujinami, T. Hoshino, T. Nakatani, T. Miyajim, T. Hikima, M. Takata. Polym. 180, 121699 (2019).10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121699Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Y. Li, Q. T. Nguyen, C. L. Buquet, D. Langevin, M. Legras, S. Marais. J. Membr. Sci. 439, 1 (2013).10.1016/j.memsci.2013.03.040Suche in Google Scholar

[52] W. Y. Hsu, T. D. Gierke. J. Membr. Sci. 13, 307 (1983).10.1016/S0376-7388(00)81563-XSuche in Google Scholar

[53] T. Awatani, H. Midorikawa, N. Kojima, J. Ye, C. Marcott. Electrochem. Commun. 30, 5 (2013).10.1016/j.elecom.2013.01.021Suche in Google Scholar

[54] A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Nanotechnol. Russ. 7, 437 (2012).10.1134/S1995078012050175Suche in Google Scholar

[55] A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. Chem. Rev. 85, 1255 (2016).10.1070/RCR4634Suche in Google Scholar

[56] A. B. Yaroslavtsev, V. V. Nikonenko, V. I. Zabolotsky. Uspekhi khimii. 72, 438 (2003).10.1070/RC2003v072n05ABEH000797Suche in Google Scholar

[57] T. Luo, S. Abdu, M. Wessling. J. Membr. Sci. 555, 429 (2018).10.1016/j.memsci.2018.03.051Suche in Google Scholar

[58] J. Catalano, T. Myezwa, M. G. De Angelis, M. Giacinti Baschetti, G. C. Sarti. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 37, 6308 (2012).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.07.047Suche in Google Scholar

[59] I. A. Stenina, E. Y. Safronova, A. V. Levchenko, Y. A. Dobrovolsky, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Therm. Eng. 63, 385 (2016).10.1134/S0040601516060070Suche in Google Scholar

[60] D. V. Golubenko, E. Yu. Safronova, A. B. Ilyin, N. V. Shevlyakova, V. A. Tverskoi, G. Pourcelly, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mendeleev Commun. 27, 380 (2017).10.1016/j.mencom.2017.07.020Suche in Google Scholar

[61] D. V. Golubenko, E. Y. Safronova, A. B. Ilyin, N. V. Shevlyakova, V. A. Tverskoi, L. Dammak, D. Grande, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mater. Chem. Phys. 197, 192 (2017).10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.05.015Suche in Google Scholar

[62] V. Arcella, A. Ghielmi, G. Tommasi. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 984, 226 (2003).10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06002.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] V. Arcella, C. Troglia, A. Ghielmi. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 44, 7646 (2005).10.1021/ie058008aSuche in Google Scholar

[64] K. D. Kreuer, M. Schuster, B. Obliers, O. Diat, U. Traub, A. Fuchs, U. Klock, S. J. Paddison, J. Maier. J. Power Sources. 178, 499 (2008).10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.11.011Suche in Google Scholar

[65] E. Y. Safronova, A. K. Osipov, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Pet. Chem. 58, 130 (2018).10.1134/S0965544118020044Suche in Google Scholar

[66] I. A. Prikhno, K. A. Ivanova, G. M. Don, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mendeleev Commun. 28, 657 (2018).10.1016/j.mencom.2018.11.033Suche in Google Scholar

[67] R. S. L. Yee, R. A. Rozendal, K. Zhang, B. P. Ladewig. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 90, 950 (2012).10.1016/j.cherd.2011.10.015Suche in Google Scholar

[68] N. Kononenko, V. Nikonenko, D. Grande, C. Larchet, L. Dammak, M. Fomenko, Y. Volfkovich. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 246, 196 (2017).10.1016/j.cis.2017.05.007Suche in Google Scholar

[69] P. Y. Apel, O. V. Bobreshova, A. V. Volkov, V. V. Volkov, V. V. Nikonenko, I. A. Stenina, A. N. Filippov, Y. P. Yampolsky, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Membr. Membr. Technol. 1, 45 (2019).10.1134/S2517751619020021Suche in Google Scholar

[70] T. Sata. Ion Exchange Membranes – Preparation, Characterization, Modification and Application, p. 324, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge (2004).Suche in Google Scholar

[71] V. Sarapulova, I. Shkorkina, S. Mareev, N. Pismenskaya, N. Kononenko, C. Larchet, L. Dammak, V. Nikonenko. Membranes. 9, 84 (2019)10.3390/membranes9070084Suche in Google Scholar

[72] M. M. Nasef, E. S. A. Hegazy. Prog. Polym. Sci. 29, 499 (2004).10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2004.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

[73] E. Y. Safronova, D. V. Golubenko, N. V. Shevlyakova, M. G. D’yakova, V. A. Tverskoi, L. Dammak, D. Grande, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. J. Membr. Sci. 515, 196 (2016).10.1016/j.memsci.2016.05.006Suche in Google Scholar

[74] M. M. Nasef, O. Güven. Prog. Polym. Sci. 37, 1597 (2012).10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.07.004Suche in Google Scholar

[75] M. M. Nasef, H. Saidi. J. Membr. Sci. 216, 27 (2003).10.1016/S0376-7388(03)00027-9Suche in Google Scholar

[76] B. Gupta, F. N. Büchi, M. Staub, D. Grman, G. G. Scherer. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 34, 1873 (1996).10.1002/(SICI)1099-0518(19960730)34:10<1873::AID-POLA4>3.0.CO;2-QSuche in Google Scholar

[77] D. V. Golubenko, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mendeleev Commun. 27, 572 (2017).10.1016/j.mencom.2017.11.011Suche in Google Scholar

[78] D. V. Golubenko, G. Pourcelly, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Separ. Purif. Technol. 207, 329 (2018).10.1016/j.seppur.2018.06.041Suche in Google Scholar

[79] S. A. Kang, J. Shin, G. Fei, B. S. Ko, C. Y. Kim, Y. C. Nho. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B. 268, 3458 (2010).10.1016/j.nimb.2010.07.017Suche in Google Scholar

[80] D. V. Golubenko, B. Van der Bruggen, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 48656 (2019).10.1002/app.48656Suche in Google Scholar

[81] H. B. Park, J. Kamcev, L. M. Robeson, M. Elimelech, B. D. Freeman. Science. 356, 1138 (2017).10.1126/science.aab0530Suche in Google Scholar

[82] E. F. Abdrashitov, V. C. Bokun, D. A. Kritskaya, E. A. Sanginov, A. N. Ponomarev, Y. A. Dobrovolsky. Solid State Ionics. 251, 9 (2013).10.1016/j.ssi.2013.06.006Suche in Google Scholar

[83] E. F. Abdrashitov, D. A. Kritskaya, V. C. Bokun, A. N. Ponomarev. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 11, 167 (2017).10.1134/S199079311701002XSuche in Google Scholar

[84] A. N. Ponomarev, E. F. Abdrashitov, D. A. Kritskaya, V. C. Bokun, E. A. Sanginov, Y. A. Dobrovolskii. Russ. J. Electrochem. 53, 589 (2017).10.1134/S1023193517060143Suche in Google Scholar

[85] D. A. Kritskaya, E. F. Abdrashitov, V. C. Bokun, A. N. Ponomarev. Pet. Chem. 58, 309 (2018).10.1134/S0965544118040059Suche in Google Scholar

[86] S. Pawlowski, J. G. Crespo, S. Velizarov. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 165 (2019).10.3390/ijms20010165Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[87] V. Vasil’eva, E. Goleva, N. Pismenskaya, A. Kozmai, V. Nikonenko. Sep. Purif. Technol. 210, 48 (2019).10.1016/j.seppur.2018.07.065Suche in Google Scholar

[88] M. Reig, H. Farrokhzad, B. van der Bruggen, O. Gibert, J. L. Cortina. Desalination. 375, 1 (2015).10.1016/j.desal.2015.07.023Suche in Google Scholar

[89] L. Ge, A. N. Mondal, X. Liu, B. Wu, D. Yu, Q. Li, J. Miao, Q. Ge, T. Xu. J. Membr. Sci. 536, 11 (2017).10.1016/j.memsci.2017.04.055Suche in Google Scholar

[90] M. Ahmad, C. Tang, L. Yang, A. Yaroshchuk, M. L. Bruening. J. Membr. Sci. 578, 209 (2019).10.1016/j.memsci.2019.02.018Suche in Google Scholar

[91] X. Zhang, Y. Xu, X. Zhang, H. Wu, J. Shen, R. Chen, Y. Xiong, J. Li, S. Guo. Prog. Polym. Sci. 89, 76 (2019).10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.10.002Suche in Google Scholar

[92] C. Jiang, D. Zhang, A. S. Muhammad, M. M. Hossain, Z. Ge, Y. He, H. Feng, T. Xu. J. Membr. Sci. 580, 327 (2019).10.1016/j.memsci.2019.03.035Suche in Google Scholar

[93] T. Xu. J. Membr. Sci. 263, 1 (2005).10.1016/j.memsci.2005.05.002Suche in Google Scholar

[94] A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Inorg. Mater. 48, 1193 (2012).10.1134/S0020168512130055Suche in Google Scholar

[95] A. B. Yaroslavtsev, Y. P. Yampolskii. Mendeleev Commun. 24, 319 (2014).10.1016/j.mencom.2014.11.001Suche in Google Scholar

[96] C. Y. Wong, W. Y. Wong, K. Ramya, M. Khalid, A. A. H. Kadhum. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 44, 6116 (2019).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.01.084Suche in Google Scholar

[97] M. R. Esfahani, S. A. Aktij, Z. Dabaghian, M. D. Firouzjaei, A. Rahimpour, J. Eke, I. C. Escobar, M. Abolhassani, L. F. Greenlee, A. R. Esfahani, A. Sadmani, N. Koutahzadeh. Sep. Purif. Technol. 213, 465 (2019).10.1016/j.seppur.2018.12.050Suche in Google Scholar

[98] D. J. Jones, J. Roziere. in Handbook of Fuel Cells – Fundamentals, Technology and Applications, W. Vielstich, H. A. Gasteiger, A. Lamm (Eds.), Vol. 3, p. 447, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester (2003).Suche in Google Scholar

[99] Y. P. Ying, S. K. Kamarudin, M. S. Masdar. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 43, 16068 (2018).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.06.171Suche in Google Scholar

[100] M. B. Karimi, F. Mohammadi, K. Hooshyari. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 44, 28919 (2019).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.09.096Suche in Google Scholar

[101] E. Ogungbemi, O. Ijaodola, F. N. Khatib, T. Wilberforce, Z. El Hassan, J. Thompson, M. Ramadan, A. G. Olabid. Energy. 172, 155 (2019).10.1016/j.energy.2019.01.034Suche in Google Scholar

[102] I. A. Stenina, E. Yu. Voropaeva, A. A. Ilyina, A. B. Yaroslavtsev Polym. Adv. Technol. 20, 566 (2009).10.1002/pat.1384Suche in Google Scholar

[103] L. Liu, W. Chen, Y. Li. J. Membr. Sci. 549, 393 (2018).10.1016/j.memsci.2017.12.025Suche in Google Scholar

[104] A. B. Yaroslavtsev, Yu. A. Karavanova, E. Yu. Safronova. Petr. Chem. 51, 473 (2011).10.1134/S0965544111070140Suche in Google Scholar

[105] E. Y. Safronova, I. A. Stenina, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 55, 13 (2010).10.1134/S0036023610010031Suche in Google Scholar

[106] K. Oh, O. Kwon, B. Son, D. H. Lee, S. Shanmugam. J. Membr. Sci. 583, 103 (2019).10.1016/j.memsci.2019.04.031Suche in Google Scholar

[107] E. V. Gerasimova, A. A. Volodin, A. E. Ukshe, Yu. A. Dobrovolsky, E. Y. Safronova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Catal. Today 193, 81 (2012).10.1016/j.cattod.2012.06.018Suche in Google Scholar

[108] A. G. Mikheev, E. Y. Safronova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev, G. Y. Yurkov. Mendeleev Commun. 23, 66 (2013).10.1016/j.mencom.2013.03.002Suche in Google Scholar

[109] D. V. Golubenko, R. R. Shaydullin, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Colloid Polym. Sci. 297, 741 (2019).10.1007/s00396-019-04499-1Suche in Google Scholar

[110] I. A. Stenina, A. A. Il’ina, I. Yu. Pinus, V. G. Sergeev, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. Chem. Bull. 57, 2261 (2008)10.1007/s11172-008-0317-zSuche in Google Scholar

[111] A. R. Kim, M. Vinothkannan, D. J. Yoo. Composites, Part B 130, 103 (2017).10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.07.042Suche in Google Scholar

[112] Z. Zakaria, S. K. Kamarudin, S. N. Timmiati, Nanoscale Res. Lett. 14, 28 (2019).10.1186/s11671-018-2836-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[113] T. D. Gierke, G. E. Munn, F. C. Wilson. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 19, 1687 (1981).10.1002/pol.1981.180191103Suche in Google Scholar

[114] I. A. Stenina, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Membr. Membr. Technol. 1, 137 (2019).10.1134/S2517751619030065Suche in Google Scholar

[115] J. Li, M. Pana, H. Tang RSC Adv. 4, 3944 (2014).10.1039/C3RA43735CSuche in Google Scholar

[116] E. Y. Safronova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Petr. Chem. 56, 281 (2016).10.1134/S0965544116040083Suche in Google Scholar

[117] J.-S. Park, M.-S. Shin, C.-S. Kim. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 5, 43 (2017).10.1016/j.coelec.2017.10.020Suche in Google Scholar

[118] K. S. Roelofs, T. Hirth, T. Schiestel. J. Membr. Sci. 346, 215 (2010).10.1016/j.memsci.2009.09.041Suche in Google Scholar

[119] M. Amjadi, S. Rowshanzamir, S. J. Peighambardoust, M. G. Hosseini, M. H. Eikani. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35, 9252 (2010).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

[120] E. Y. Mironova, A. A. Lytkina, M. M. Ermilova, M. N. Efimov, L. M. Zemtsov, N. V. Orekhova, G. P. Karpacheva, G. N. Bondarenko, A. B. Yaroslavtsev, D. N. Muraviev. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 3557 (2015).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.11.082Suche in Google Scholar

[121] H. Ahmad, S. K. Kamarudin, U. A. Hasran, W. R. W. Daud. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35, 2160 (2010).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.12.054Suche in Google Scholar

[122] H. Ahmad, S. K. Kamarudin, U. A. Hasran, W. R. W. Daud. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 36, 14668 (2011).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.08.044Suche in Google Scholar

[123] A. K. Sahu, S. Meenakshi, S. D. Bhat, A. Shahid, P. Sridhar, S. Pitchumani, A. K. Shukla. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, F702 (2012).10.1149/2.036211jesSuche in Google Scholar

[124] F. Lufrano, V. Baglio, O. Di Blasi, P. Staiti, V. Antonucci, A. S. Aricò. Solid State Ionics 216, 90 (2012).10.1016/j.ssi.2012.03.015Suche in Google Scholar

[125] K. Kreuer. Solid State Ionics 97, 1 (1997).10.1016/S0167-2738(97)00082-9Suche in Google Scholar

[126] K. D. Kreuer. J. Membr. Sci. 185, 29 (2001).10.1016/S0376-7388(00)00632-3Suche in Google Scholar

[127] H. Lade, V. Kumar, G. Arthanareeswaran, A. F. Ismail. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 1063 (2017).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.10.038Suche in Google Scholar

[128] G. Alberti, M. Casciola, E. D’Alessandro, M. Pica. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 1910 (2004).10.1039/b400467aSuche in Google Scholar

[129] S. A. Novikova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev, G. Y. Yurkov. Inorg. Mater. 46, 793 (2010).10.1134/S0020168510070198Suche in Google Scholar

[130] D. J. Kim, M. J. Jo, S. Y. Nam. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 21, 36 (2015).10.1016/j.jiec.2014.04.030Suche in Google Scholar

[131] M. A. Hickner, H. Ghassemi, Y. S. Kim, B. R. Einsla, J. E. McGrath. Chem. Rev. 104, 4587 (2004).10.1021/cr020711aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[132] A. A. Lysova, I. I. Ponomarev, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Solid State Ionics 188, 132 (2011).10.1016/j.ssi.2010.10.010Suche in Google Scholar

[133] A. A. Lysova, I. I. Ponomarev, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 57, 1 (2012).10.1134/S0036023612010147Suche in Google Scholar

[134] L.-C. Jheng, S. L.-C. Hsu, T.-Y. Tsai, W. J.-Y. Chang. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 4225 (2014).10.1039/c3ta14631fSuche in Google Scholar

[135] K. Hwang, J.-H. Kim, S.-Y. Kim, H. Byun. Energies (Basel, Switz.) 7, 1721 (2014).10.3390/en7031721Suche in Google Scholar

[136] A. A. Lysova, I. A. Stenina, A. O. Volkov, I. I. Ponomarev, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Solid State Ionics 329, 25 (2019).10.1016/j.ssi.2018.11.012Suche in Google Scholar

[137] A. A. Lysova, I. I. Ponomarev, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mendeleev Commun. 29, 403 (2019).10.1016/j.mencom.2019.07.015Suche in Google Scholar

[138] A. Daniilidis, R. Herber, D. A. Vermaas. Appl. Energy. 119, 257 (2014).10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.12.066Suche in Google Scholar

[139] K. Xu, Chem. Rev. 104, 4303 (2004).10.1021/cr030203gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[140] K. Vignarooban, R. Kushagra, A. Elango, P. Badami, B. E. Mellander, X. Xu, T. G. Tucker, C. Nam, A. M. Kannan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 41, 2829 (2016).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.12.090Suche in Google Scholar

[141] G. Zhu, K. Wen, W. Lv, X. Zhou, Y. Liang, F. Yang, Z. Chen, M. Zou, J. Li, Y. Zhang, W. He. J. Power Sources 300, 29 (2015).10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.09.056Suche in Google Scholar

[142] D. Y. Voropaeva, D V. Golubenko, S. A. Novikova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Nanotechnol. Russ. 13, 256 (2018).10.1134/S1995078018030199Suche in Google Scholar

[143] D. Y. Voropaeva, S. A. Novikova, T. L. Kulova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Ionics, 24, 1685 (2018).10.1007/s11581-017-2333-1Suche in Google Scholar

[144] D. Y. Voropaeva, S. A. Novikova, T. L. Kulova, A. M. Skundin, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Solid State Ionics 324, 28 (2018).10.1016/j.ssi.2018.06.002Suche in Google Scholar

[145] V. Subramani, A. Basile, T. N. Veziroglu. Compendium of Hydrogen Energy, p. 550, Woodhead Publ., Cambridge (2015).Suche in Google Scholar

[146] M. R. Rahimpour, F. Samimi, A. Babapoor, T. Tohidian, S. Mohebi. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 121, 24 (2017).10.1016/j.cep.2017.07.021Suche in Google Scholar

[147] A. Iulianelli, P. Ribeirinha, A. Mendes, A. Basile. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 29, 355 (2014).10.1016/j.rser.2013.08.032Suche in Google Scholar

[148] D. Alique, D. Martinez-Diaz, R. Sanz, J. A. Calles. Membranes 8, 5 (2018).10.3390/membranes8010005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[149] V. N. Alimov, I. V. Bobylev, A. O. Busnyuk, M. E. Notkin, E. Y. Peredistov, A. I. Livshits. J. Membr. Sci. 549, 428 (2018).10.1016/j.memsci.2017.12.017Suche in Google Scholar

[150] V. N. Alimov, I. V. Bobylev, A. O. Busnyuk, S. N. Kolgatin, S. R. Kuzenov, E. Y. Peredistov, A. I. Livshits. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43, 13318 (2018).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.05.121Suche in Google Scholar

[151] S. S. Hashim, M. R. Somalu, K. S. Loh, S. Liu, W. Zhou, J. Sunarso. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43, 15281 (2018).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.06.045Suche in Google Scholar

[152] F. Gallucci, E. Fernandez, P. Corengi, M. S. Annaland. Chem. Eng. Sci. 92, 40 (2013).10.1016/j.ces.2013.01.008Suche in Google Scholar

[153] A. A. Lytkina, N. V. Orekhova, M. M. Ermilova, M. N. Efimov, A. B. Yaroslavtsev, S. V. Belenov, V. E. Guterman. Catal. Today 268, 60 (2016).10.1016/j.cattod.2016.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

[154] A. A. Lytkina, N. V. Orekhova, M. M. Ermilova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43, 198 (2018).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.10.182Suche in Google Scholar

[155] N. L. Basov, M. M. Ermilova, N. V. Orekhova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Russ. Chem. Rev. 82, 352 (2013).10.1070/RC2013v082n04ABEH004324Suche in Google Scholar

[156] S. A. Grigoriev, V. I. Porembsky, V. N. Fateev. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 31, 171 (2006).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2005.04.038Suche in Google Scholar

[157] X. Li, H. Zhang, Z. Mai, H. Zhang, I. Vankelecom. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 1147 (2011).10.1039/c0ee00770fSuche in Google Scholar

[158] W. Wang, Q. Luo, B. Li, X. Wei, L. Li, Z. Yang. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 970 (2013).10.1002/adfm.201200694Suche in Google Scholar

[159] M. Sadrzadeh, T. Mohammadi. Desalination 221, 440 (2008).10.1016/j.desal.2007.01.103Suche in Google Scholar

[160] Y. Tanaka. in Prog. Filtr. Sep., S. Tarleton (Ed.), pp. 207–284, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2015).10.1016/B978-0-12-384746-1.00006-9Suche in Google Scholar

[161] J. G. Hong, B. Zhang, S. Glabman, N. Uzal, X. Dou, H. Zhang, X. Wei, Y. Chen, J. Membr. Sci. 486, 71 (2015).10.1016/j.memsci.2015.02.039Suche in Google Scholar

[162] D. V. Golubenko, Y. A. Karavanova, S. S. Melnikov, A. R. Achoh, G. Pourcelly, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. J. Membr. Sci. 563, 777 (2018).10.1016/j.memsci.2018.06.024Suche in Google Scholar

[163] M. Paidar, V. Fateev, K. Bouzek. Electrochim. Acta 209, 737 (2016).10.1016/j.electacta.2016.05.209Suche in Google Scholar

[164] O. V. Bobreshova, A. V. Parshina, K. A. Polumestnaya, K. Y. Yankina, E. Y. Safronova, A. B. Yaroslavtsev. Mendeleev Commun. 22, 83 (2012).10.1016/j.mencom.2012.03.010Suche in Google Scholar

[165] E. Safronova, D. Safronov, A. Lysova, A. Parshina, O. Bobreshova, G. Pourcelly, A. Yaroslavtsev. Sens. Actuators, B 240, 1016 (2017).10.1016/j.snb.2016.09.010Suche in Google Scholar

[166] A. Van Der Wal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 4904 (2013).10.1021/es3053202Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[167] T. B. H. Schroeder, A. Guha, A. Lamoureux, G. Vanrenterghem, D. Sept, M. Shtein, J. Yang, M. Mayer. Nature 552, 214 (2017).10.1038/nature24670Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2020 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- Research papers from the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Conference papers of the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Unusual behavior of bimetallic nanoparticles in catalytic processes of hydrogenation and selective oxidation

- Soft chemistry of pure silver as unique plasmonic metal of the Periodic Table of Elements

- Catalytic hydrogenation with parahydrogen: a bridge from homogeneous to heterogeneous catalysis

- Azidophenylselenylation of glycals towards 2-azido-2-deoxy-selenoglycosides and their application in oligosaccharide synthesis

- Bis-γ-carbolines as new potential multitarget agents for Alzheimer’s disease

- Octafluorobiphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate as a ligand for metal-organic frameworks: progress and perspectives

- Some aspects of the formation and structural features of low nuclearity heterometallic carboxylates

- Particular kinetic patterns of heavy oil feedstock hydroconversion in the presence of dispersed nanosize MoS2

- Concentration profiles around and chemical composition within growing multicomponent bubble in presence of curvature and viscous effects

- Application of gold nanoparticles in the methods of optical molecular absorption spectroscopy: main effecting factors

- Membrane materials for energy production and storage

- New types of the hybrid functional materials based on cage metal complexes for (electro) catalytic hydrogen production

- Conference paper of the 15th Eurasia Conference on Chemical Sciences

- Discovery of bioactive drug candidates from some Turkish medicinal plants-neuroprotective potential of Iris pseudacorus L.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- Research papers from the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Conference papers of the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Unusual behavior of bimetallic nanoparticles in catalytic processes of hydrogenation and selective oxidation

- Soft chemistry of pure silver as unique plasmonic metal of the Periodic Table of Elements

- Catalytic hydrogenation with parahydrogen: a bridge from homogeneous to heterogeneous catalysis

- Azidophenylselenylation of glycals towards 2-azido-2-deoxy-selenoglycosides and their application in oligosaccharide synthesis

- Bis-γ-carbolines as new potential multitarget agents for Alzheimer’s disease

- Octafluorobiphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate as a ligand for metal-organic frameworks: progress and perspectives

- Some aspects of the formation and structural features of low nuclearity heterometallic carboxylates

- Particular kinetic patterns of heavy oil feedstock hydroconversion in the presence of dispersed nanosize MoS2

- Concentration profiles around and chemical composition within growing multicomponent bubble in presence of curvature and viscous effects

- Application of gold nanoparticles in the methods of optical molecular absorption spectroscopy: main effecting factors

- Membrane materials for energy production and storage

- New types of the hybrid functional materials based on cage metal complexes for (electro) catalytic hydrogen production

- Conference paper of the 15th Eurasia Conference on Chemical Sciences

- Discovery of bioactive drug candidates from some Turkish medicinal plants-neuroprotective potential of Iris pseudacorus L.