Abstract

Successful using of cage metal complexes (clathrochelates) and the functional hybrid materials based on them as promising electro- and (pre)catalysts for hydrogen and syngas production is highlighted in this microreview. The designed polyaromatic-terminated iron, cobalt and ruthenium clathrochelates, adsorbed on carbon materials, were found to be the efficient electrocatalysts of the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), including those in polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) water electrolysers. The clathrochelate-electrocatalayzed performances of HER 2H+/H2 in these semi-industrial electrolysers are encouraging being similar to those for the best known to date molecular catalysts and for the promising non-platinum solid-state HER electrocatalysts as well. Electrocatalytic activity of the above clathrochelates was found to be affected by the number of the terminal polyaromatic group(s) per a clathrochelate molecule and the lowest Tafel slopes were obtained with hexaphenanthrene macrobicyclic complexes. The use of suitable carbon materials of a high surface area, as the substrates for their efficient immobilization, allowed to substantially increase an electrocatalytic activity of the corresponding clathrochelate-containing carbon paper-based cathodes. In the case of the reaction of dry reforming of methane (DRM) into syngas of a stoichiometry CO/H2 1:1, the designed metal(II) clathrochelates with terminal polar groups are only the precursors (precatalysts) of single atom catalysts, where each of their catalytically active single sites is included in a matrix of its former encapsulating ligand. Choice of their designed ligands allowed an efficient immobilization of the corresponding cage metal complexes on the surface of a given highly porous ceramic material as a substrate and caused increasing of a surface concentration of the catalytically active centers (and, therefore, that of the catalytic activity of hybrid materials modified with these clathrochelates). Thus designed cage metal complexes and hybrid materials based on them operate under the principals of “green chemistry” and can be considered as efficient alternatives to some classical inorganic and molecular (pre)catalysts of these industrial processes.

Introduction

A great technological challenge for our global future is the search for a safe, green and renewable energy source [1]. If not found, increase in energy demand derived from economical and population growth will soon result in even higher carbon dioxide emissions. This impact on climate change can have dramatic consequences for mankind. So, the creation of new generation of catalytic materials for highly selective conversion of carboniferous fossil fuels and, first of all, methane, as most abundant component of natural gas, into hydrogen-containing mixtures of the products of their transformations (in particular, giving a syngas [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]) seems to be also very important task of the modern hydrogen energy and the compressive chemical industry as well. On the other hand, hydrogen is a potential alternative to carboniferous fossil fuels if obtained from an appropriate source. Carbon intensity can be decreased significantly if water, with solar light as an energy input, is the primary carbon-neutral H2 source [1]. However, the wide use of various electrochemical systems (fuel cells, electrolysers, etc.) in hydrogen energy, high-tech industries, green hybrid and hydrogen-based transports and other different fields of modern social and economic life cause a substantial increase in a consumption of precious metals, which are currently used as electrocatalysts for hydrogen production. Their high cost significantly limits wide-spread use of the above electrocatalytic systems in hydrogen energy. The use of cheap and abundant non-platinum metal compounds in the fuel cells, electrolysers and electrochemical hydrogen compressors/concentrators in nuclear energetics will make hydrogen energetic devices more available than ever. So, one of the most important task of modern hydrogen energy is the search of highly efficient catalytic systems, effectively producing hydrogen from aqueous solutions. During last decades, the electrocatalytic reduction of H+ ions into molecular hydrogen with the molecular 3d-transition metal compounds (first of all, the cobalt complexes) as catalysts has been widely used [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23] for hydrogen production of H2 as ecologically friendly fuel; the results of these studies are highlighted in several reviews [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. Quasiaromatic d-metal clathrochelates [31], [32] are cheap, synthetically available and environmental-friendly compounds with both the chemical and thermodynamical stability in at least two oxidation states, as well as in the wide range of redox potentials, pH and temperature. They display a high rate of electron transfer, and their redox potentials may be tuned using the functionalizing substituents at their cage frameworks; the rational design of these cage electro(pre)catalysts allow obtaining those with the lowest overpotential of the redox reaction 2H+/H2. The use of such a functionalizing substituents with terminal polyaromatic groups allows an efficient immobilization of thus designed clathrochelate molecules as the electro(pre)catalysts via their strong physical sorption on a surface of carbon materials or that of working electrodes to give the long-lived catalytic systems possessing a high efficiency in hydrogen production 2H+/H2, while those with terminal polar groups can be effectively immobilized on ceramic (oxide) supports, thus giving the hybrid clathrochelate-containing systems for catalytic production of syngas (and, therefore, of molecular hydrogen).

Moreover, the hybrid polynuclear cage metal compounds, as well as their chelate and macrocyclic analogs [22], [23], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], pave the way towards efficient photocatalytic devices for hydrogen production. The hybrid cobalt and iron cage complexes appear to be good candidates for H2-evolving catalysts, and they may provide a good basis for the design of photocatalysts that function in water as both the solvent and the sustainable proton source. A molecular link between the sensitizer and the H2-evolving catalyst seems to provide an advantage for the photocatalytic activity: its structural modifications may allow for a better tuning of the electron transfer between the light-harvesting unit and the catalytic center to increase an efficiency of the system. The functionalized sulfide clathrochelate electrocatalysts and those with terminal thiol groups seem to be prospective for their immobilization on a surface of chalogenide quantum dots and, therefore, for the corresponding photocatalytic systems with these dots as photosensitizers.

Clathrochelate-based electrocatalyst of the HER 2H+/H2

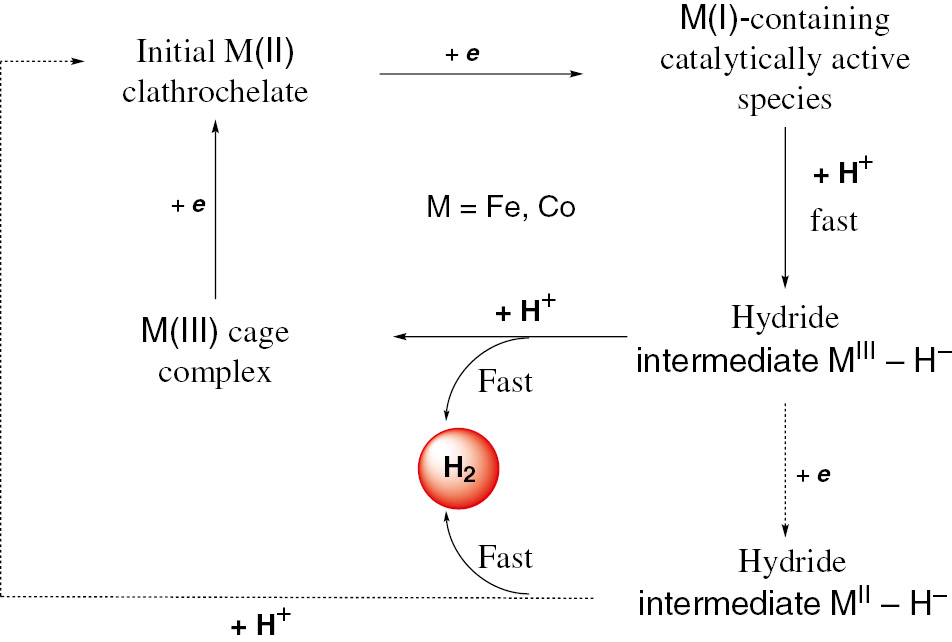

For the first time, the boron-capped cobalt tris-dioximate clathrochelates 1–4 shown in Fig. 1 have been proposed [38] as potent efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen production from acidic media and their electrochemically generated reduced cobalt(I)-containing derivatives are deduced in this work to be the catalytically active intermediates of the HER 2H+/H2, giving the corresponding Co(III)–H hydride intermediates [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [39], which have been theoretically studied [40], [41]. Plausible general catalytic cycle of the clathrochelate-electrocatalyzed HER, based on a formation of the former cobalt(I)-encapsulating intermediate, is shown in Fig. 2. As the above probable catalytic cycle for electrochemical hydrogen production includes the formation cobalt(I, II, and III)-containing clathrochelate species, the detailed study of their electronic structure has been performed [42]. The nature of their encapsulating ligands is found in this work to affect the redox characteristics of their caged metallocenters, allowing them to adopt the unusual catalytically active oxidation states. The combined theoretical (DFT) and spectral (EPR and XPS) studies have been employed [43] to assess the electronic structure of the clathrochelate catalysts 5–7 (Fig. 3) of the HER, which has been subsequently coupled in this work to the cyclic voltammetry data; the electrochemical kinetics of these systems has been also studied [43]. Its data for these cobalt clathrochelates exhibited two quasi-reversible electron transfer processes, assigned to the redox Co3+/2+ and Co2+/+ couples. In all the cases, the standard electrochemical rate constants of one-electron transfers close to 10−3 cm s−1, which are the characteristic values for the quasireversible processes were found. Their electroactivity towards the HER has been determined [43] by addition of sulfuric acid to the electrochemical cell and a cobalt clathrochelate with the most electron-withdrawing groups is reported to possess the lowest overpotential for the hydrogen-producing process 2H+/H2. This suggests that the difference in the electrocatalytic activity of the above cage complexes 5–7 is substantially affected by the electromeric characteristics of their apical and ribbed substituents. So, in order to design the macrobicyclic electrocatalysts of this type, displaying a lower overpotential of the HER, such an electron-withdrawing substituents are proposed [43] to be inserted into their encapsulating ligands.

First cobalt clathrochelate electrocatalysts of the HER.

Proposed scheme of the clathrochelate-electrocatalyzed HER.

Chemical drawings of the electrocatalytically active cobalt clathrochelates.

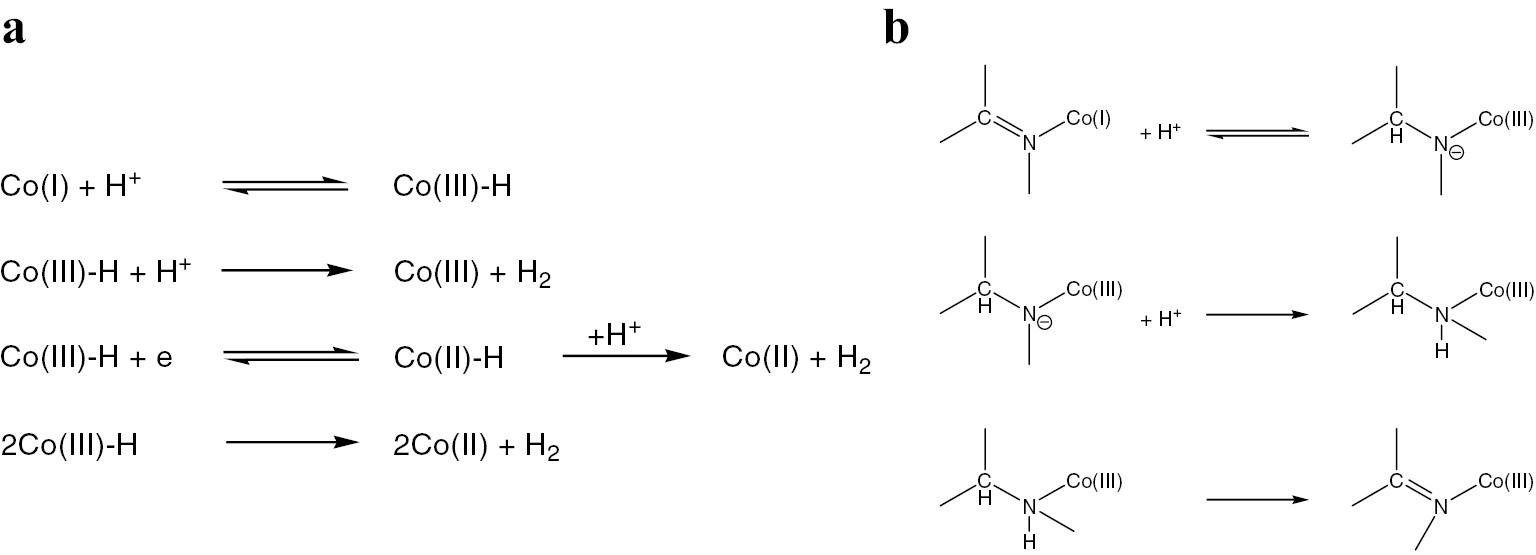

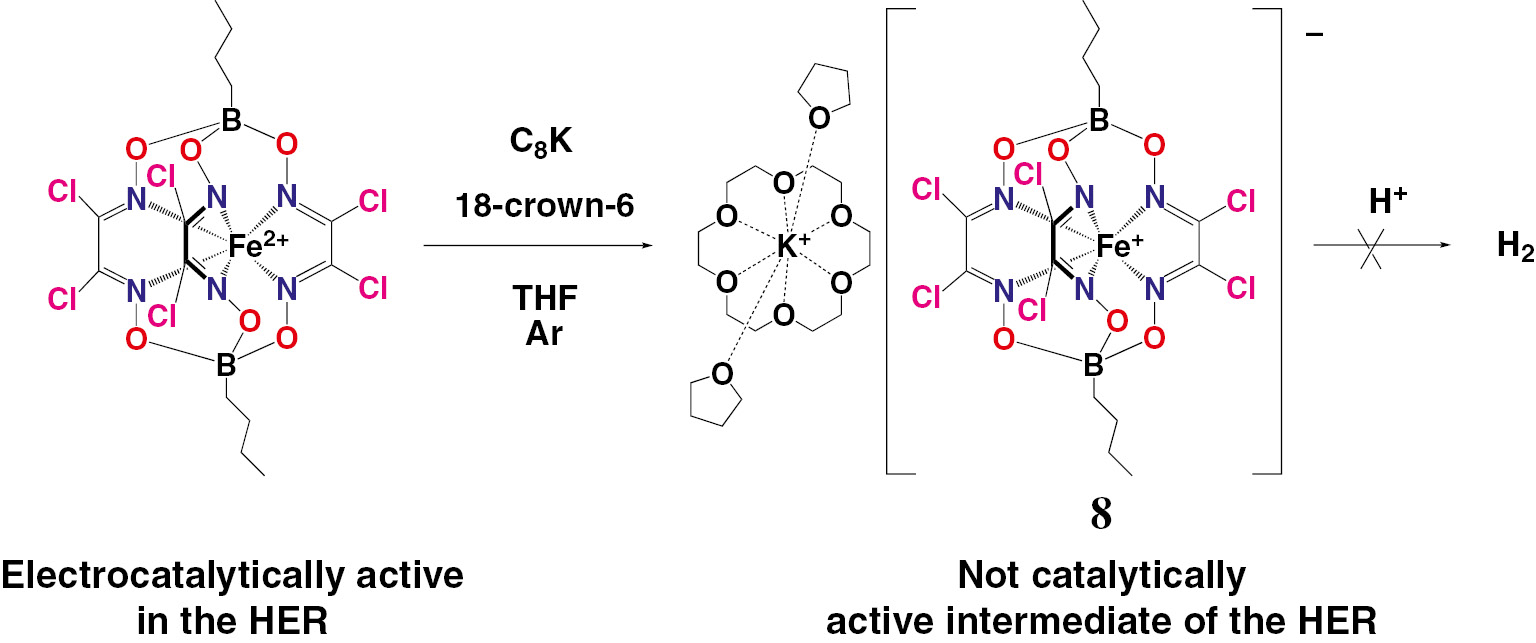

However, the exact catalytic mechanism of the HER in the case of the cage cobalt and iron complexes remains an open question [44], [45], [46]. In the case of cobalt clathrochelates, a plausible mechanism of their electrocatalytic activity is proposed [44] to be either a purely metal-centered activation of H+ ions or an intimate cooperation between the macrobicyclic ligand and the encapsulated cobalt ion for the formation of H2. Among the different scenarios discussed, the reaction mechanism might be similar to those proposed for the well-known cobaloxime complexes (Fig. 4a), the reactive site might be localized on the polyazomethine quasiaromatic caging ligands (Fig. 4b), or possibly possess an even more complex character, including both the encapsulated metallocenter and the caging ligand [44]. On the other hand, it was unambiguously shown [44], [45] that an electrochemical reduction of these cobalt clathrochelates in the presence of an acid causes electrodeposition of the cobalt-containing nanoparticles on the electrode surface, which then act as very active catalysts for the production of H2 from water. For the iron cage complexes (see below), the precise electrocatalytic mechanism (as a truly molecular homogenous or a nanoparticles-forming heterogenous process) is also unknown, but the recent results [48] demonstrated an unrivalled stability of a remarkably robust iron(I) clathrochelate 8 (Scheme 1) under strongly acidic conditions. The same chemical behaviour is also reported [48] for its cobalt(I)-encapsulating clathrochelate analog 10 (Scheme 2), for the first time, was obtained [49] by a chemical reduction of its cobalt(II)-encapsulating precursor 9. The above results allowed to reassess the origins of the electrocatalytic activity of similar cobalt and iron cage complexes shown previously to be catalytically active in the HER (including hydrogen production in water electrolysers): most probably, they are the precursors of the corresponding metal-containing nanoparticles or those of an atomic level.

Formation of the cobalt–hydride intermediates (a) and of the corresponding ligand-supported species (b).

Synthesis and reactivity of an iron(I) hexachloroclathrochelate.

Synthesis and reactivity of an cobalt(I) hexachloroclathrochelate.

Indeed, as follows from the electrochemical data [44], the fluoroboron-capped tris-α-benzildioximate cobalt clathrochelate 11 (Fig. 3) serves only as a molecular precatalysts for electrodeposition of the cobalt-containing electrocatalytically active nanoparticles on the electrode surface. Those efficiently catalyze a hydrogen evolution from aqueous solutions at pH 7 at a modest cathodic potential [44]. Then, the boron-capped cobalt tris-dioximates 3, 11 and 12 shown in Figs. 1 and 3 have been used [45] as precatalysts of the catalytic HER in acidic aqueous solutions. The performed electrochemical study of the above cage complexes revealed the formation of cobalt-based nanoparticles on a surface of the corresponding working electrode. The potential for their electrochemical deposition is reported [45] to be affected by chemical nature of the ribbed and apical substituents at a macrobicyclic framework.

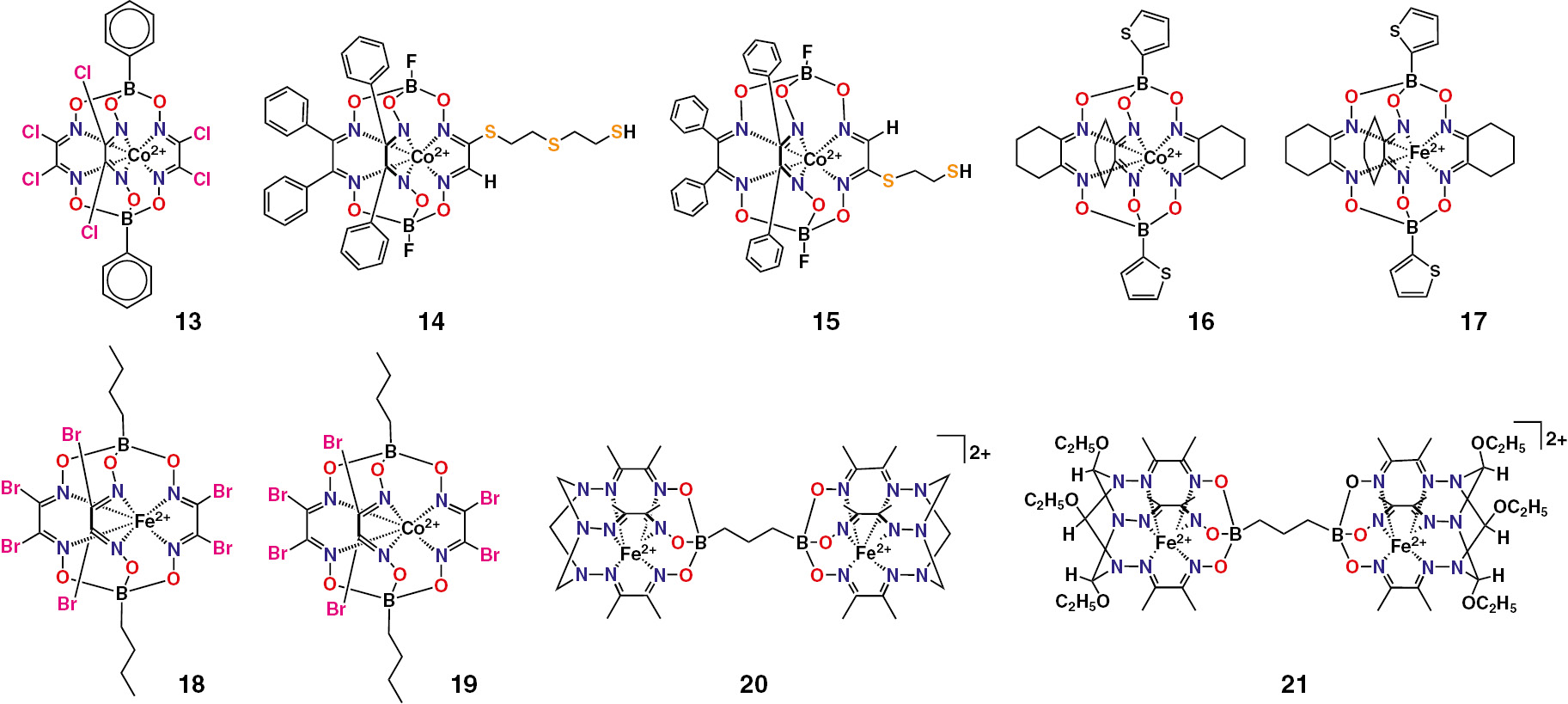

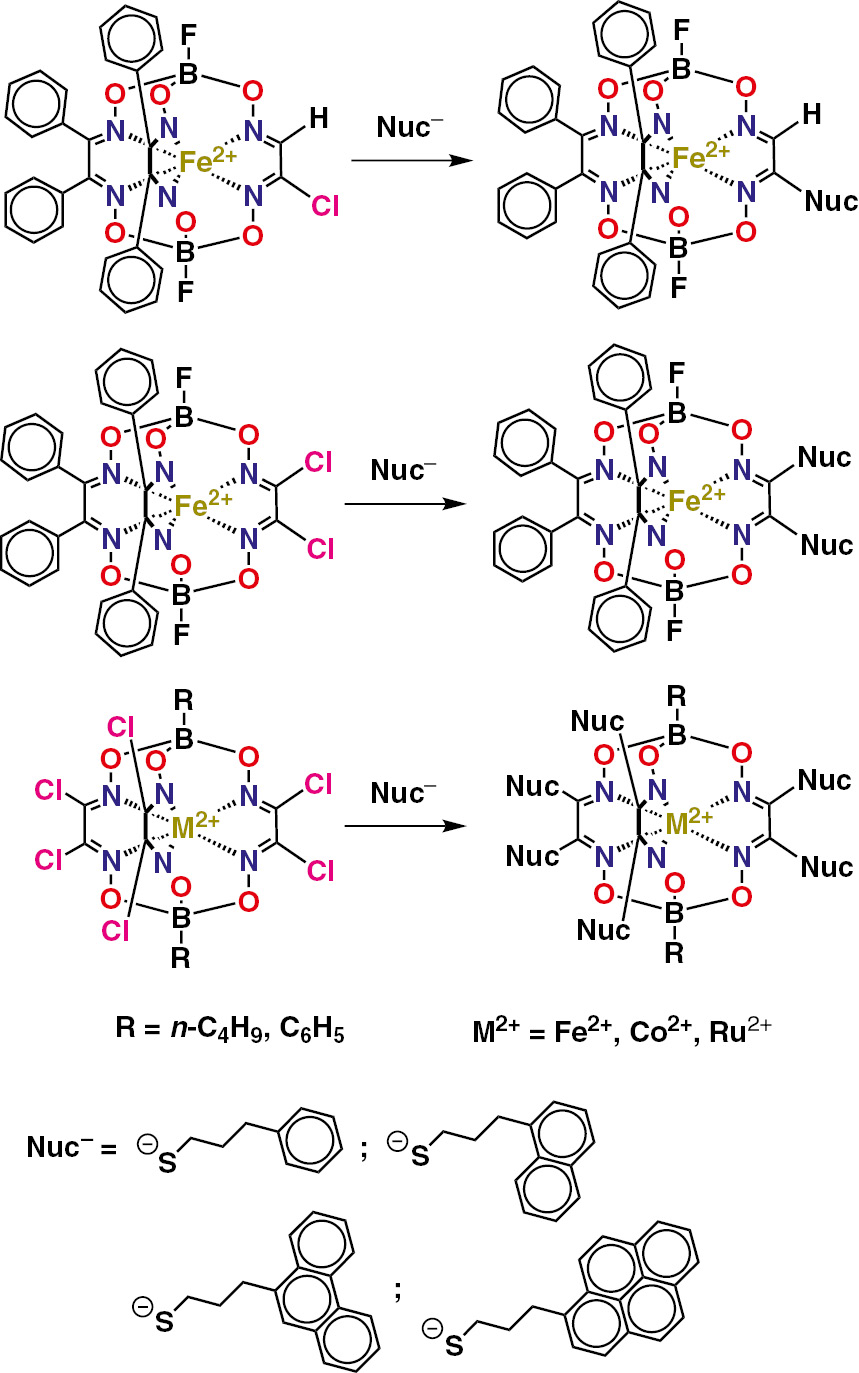

The n-butyl- and phenylboron-capped tris-dioximate cobalt(II) hexachloroclathrochelates 9 and 13 (Scheme 2 and Fig. 5) are reported [50] to give the electrocatalytic systems, producing of molecular hydrogen from H+ ions at very low overpotentials of the HER 2H+/H2. The electrocatalytic properties of the cobalt clathrochelate-based electrocatalysts 14 and 15 of the HER from acidic media have been studied [51]. The efficiency of this redox reaction has been increased [51] by immobilization of these cage complexes with terminal thiol group(s) on a surface of the working gold electrode; the examples of such an immobilization are shown in Scheme 3. The macrobicyclic 2-thiopheneboron-capped iron and cobalt(II) tris-dioximates 16 and 17 were found [52] to give the highly active electrocatalytic systems for hydrogen production from H+ ions. The boron-capped iron and cobalt(II) hexabromoclathrochelates 18 and 19 are also reported [53] to be an electrocatalitycally active in various hydrogen producing systems. The iron(II) α-oximehydrazonate bis-clathrochelates 20 and 21 have been tested [54] as prospective electrocatalytically active compounds for hydrogen production from H+ ions.

Chemical drawings of the iron and cobalt(II) mono- and bis-clathrochelates under discussion.

Preparation of the thiol-terminated cobalt(II) clathrochelates and their immobilization on a gold electrode.

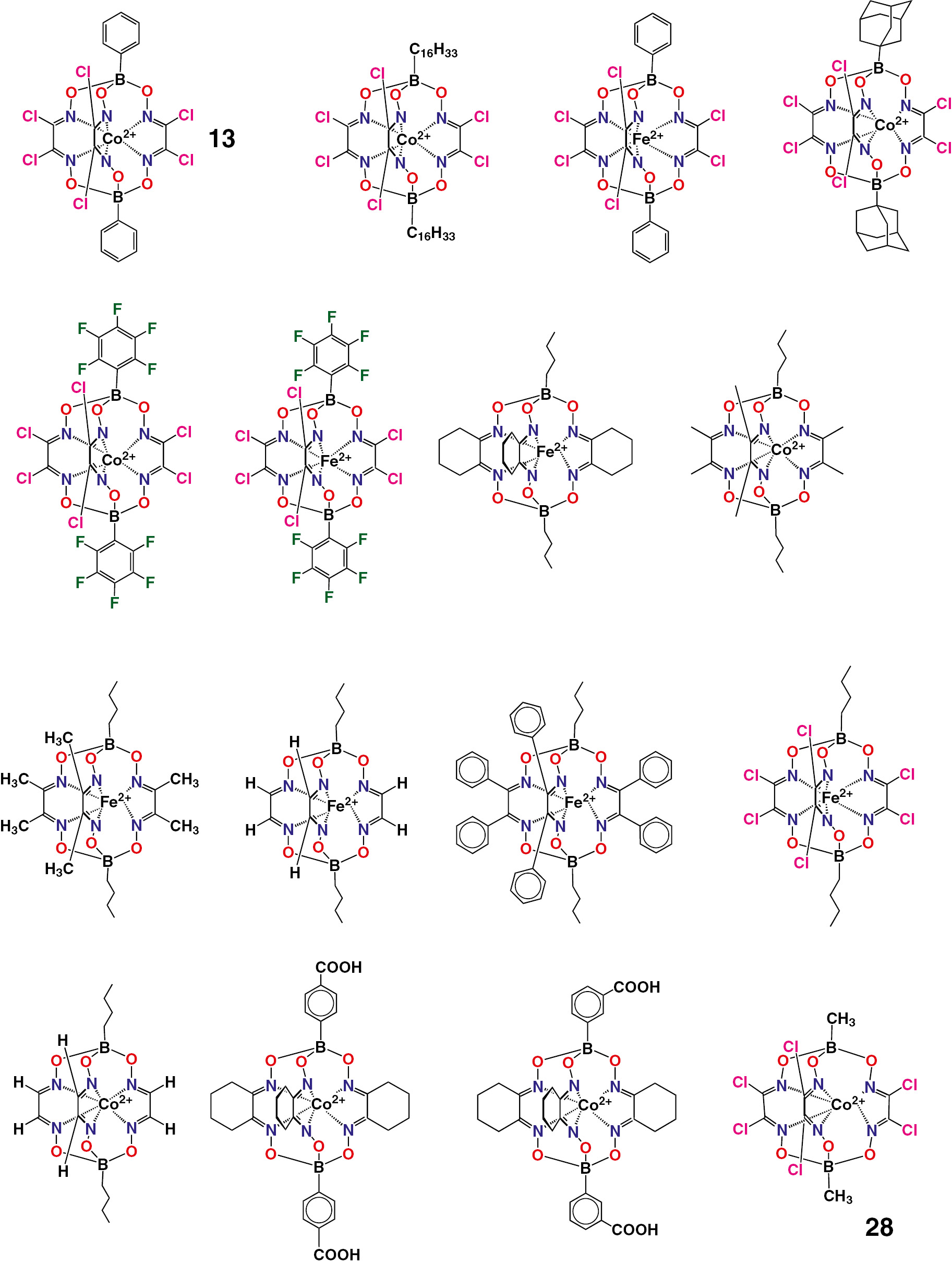

Chemical drawings of a series of the iron and cobalt(II) clathrochelates tested [55] as the cathode materials for electrocatalytic hydrogen production in the semi-industrial water electrolysers are shown in Fig. 6. They were tested in the above electrolysers, either as impregnated in their fine-crystalline form, or an immobilized on the carbonaceous substrates as the cathode materials of these electrolysers. In particular, aiming to use the immobilized iron- and cobalt-containing electrocatalysts, the derivatives of abundant biometals, instead of metallic platinum, new non-platinum hexachloroclathrochelate-based electrode materials for electrocatalytic hydrogen production have been tested [55] in water electrolysers. The use of a solution – dissolution technique was found in this work to allow a formation of the strongly physically adsorbed self-assembled monolayers on a surface of the corresponding carbon material (even inside its pores). So, in this case, the relative surface concentration of the catalytically active metallocenters might be higher than that of the clathrochelate-impregnated cathode; even at the high current density values, a decrease in the difference between the cathodes with an immobilized and an impregnated clathrochelate complexes has been observed [55].

Chemical drawings of the electrocatalytically active iron and cobalt(II) clathrochelates.

Iron(II) clathrochelates shown in Scheme 4 have been designed [56] for their efficient physical adsorption on carbonaceous substrates; the general scheme of an immobilization of the (poly)aromatic-terminated metal(II) clathrochelates on the carbon materials of practical interest is shown in Fig. 7. Electrochemistry of thus designed mono-, di- and hexafunctionalized iron(II) cage complexes with terminal (poly)aromatic group(s) in their ribbed substituent(s) has been studied [57] by CV method in a wide range of the potential, thus allowing to clarify the nature and character of the metal- and ligand-centered redox processes of their cathodic reduction and anodic oxidation. These polyaromatic-terminated clathrochelates were also immobilized [57] on a surface of the carbonaceous substrates, such as activated carbon (AC) and reduced graphene oxide (RGO); an adsorption of the n-butylboron-capped hexaphenanthrene iron(II) clathrochelate 27, as well as that of its mono- and difunctionalized analogs, have been studied using UV-vis method. Such a physical adsorption is reported [57] to be a structure-dependent process, which is strongly affected by the nature of a clathrochelate molecule {in particular, by the number of its terminal (poly)aromatic group(s)}. This effect is explained [57] by peculiarities of a macrostructure of the above carbon materials: the wedge-shaped pores are presented in a macrostructure of RGO, both the size and the form of which is favorable for the physical adsorption of bulky molecules of the hexaphenanthrenyl-terminated macrobicyclic complexes, while the size and the form of mesopores of AC are favorable for that of the difunctionalized iron(II) clathrochelate.

Synthesis of the (poly)aromatic-terminated metal(II) clathrochelates.

Immobilization of the polyaromatic-terminated metal(II) clathrochelates on carbonaceous substrates.

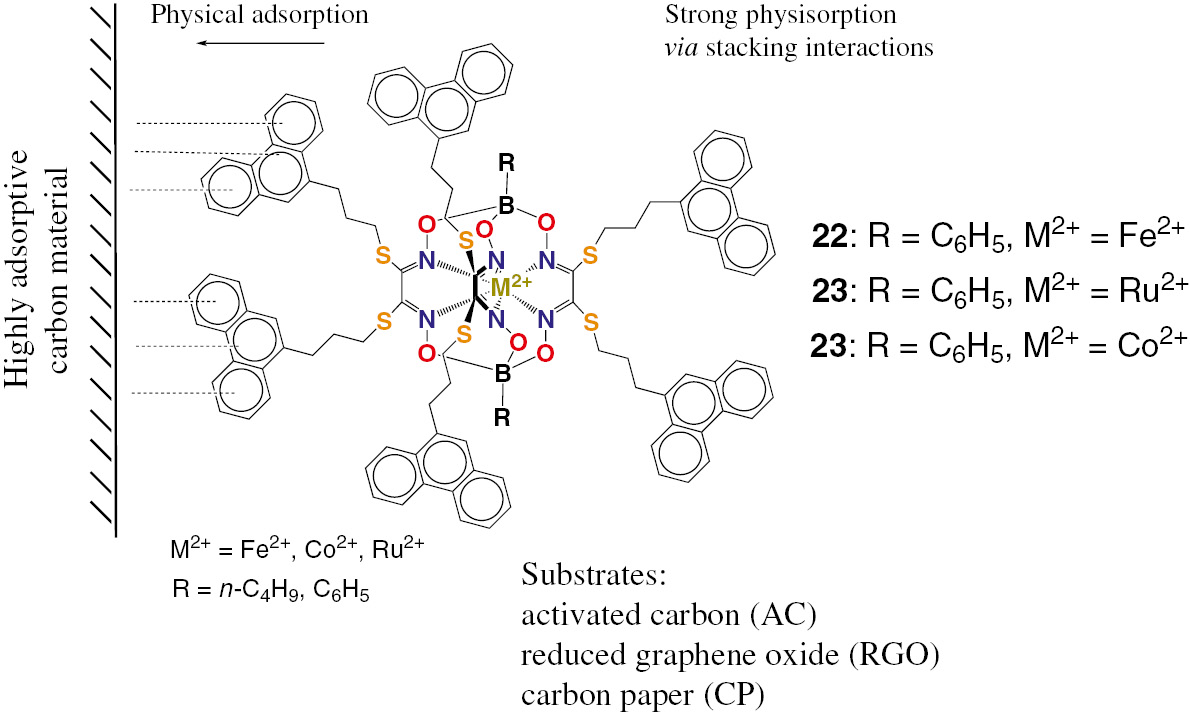

A series of the iron, cobalt and ruthenium(II) clathrochelate analogs 22–24 (Fig. 7), the derivatives of the same macrobicyclic ligand with six terminal phenanthrenyl groups, known as one of the most efficient adsorbate, have been prepared [58]; their detailed CV study over a wide range of potential scan rates, as well as the study of their immobilization on three carbonaceous substrates, AC, RGO and carbon paper (CP), known to be the most common cathode materials, have been also performed in this work. The cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 22–24 were found [58] to contain the single irreversible (or quasiirreversible) cathodic reduction wave and two anodic oxidation waves assigned to the metal-centered M2+/+ reduction and M2+/3+ oxidation processes and to a ligand-centered oxidation of their terminal phenanthrenyl groups, respectively.

Adsorption of the phenylboron-capped metal(II) hexaphenanthrene clathrochelates 22–24 on the above carbon materials, as well as that of their mono-, di- and hexafunctionalized iron(II)-encapsulating analogs 25–27 (Fig. 8) on CP, have been studied [58], [59] using UV-vis spectrophotometry. For the former complexes, the values of a free Gibbs energy are relatively low, similar to each other and characteristic of physical adsorption processes via the stacking and Van-der-Waals interactions. Their limiting specific adsorption on AC is substantially lower than that on RGO and was found [58] to increase with an increase in a Shannon radius of the encapsulated metal ion. The adsorption equilibrium constants K for RGO are higher than those on AC. The values of their limiting specific adsorption on AC are substantially higher than those on CP, while the corresponding values of the adsorption constant K are lower. So, the adsorbed quantities of hexaphenanthrene metal(II) clathrochelates per weight unit of adsorbent were found [58] to be higher for AC than those for CP, while the relative energies of their supramolecular interactions with the CP surface are higher than those with the AC surface. Adsorption on CP in a row of the mono-, di- and hexafuntionalized iron(II) cage complexes is reported [59] to increase with an increase in the number of their functionalizing ribbed substituents per clathrochelate molecule.

Chemical drawings of the phenanthrenyl-terminated iron(II) clathrochelates.

The n-butylboron-capped iron(II) hexaphenanthrenylsulfide clathrochelate 27 (Fig. 8) has been either immobilized or impregnated on the cathode of gas diffusion electrode and its electrochemical activity with regard to the HER has been tested [56] in a PEM water electrolysis cell for hydrogen production. The effective immobilization of this (pre)catalyst on the surface of appropriate carbon electrode material is reported [56] to be successfully implemented for improving an efficiency of the corresponding clathrochelate-based hydrogen-producing system.

Performances of the HER in PEM water electrolysis cells with the polyaromatic-terminated iron(II) clathrochelates 25–27 as electro(pre)catalysts, the molecules of which are beared with a different number of the terminal phenanthrenyl groups (Fig. 8), have been compared [60] with that containing a metallic platinum as a standard. It was found [60] that these compounds still cannot fully complete with metallic platinum for the moment, but their performances are already encouraging. The electrocatalytic activity of three iron(II) clathrochelate analogs shown in Fig. 8 in the HER is described to be affected by the number of terminal phenathrenyl group(s) per clathrochelate molecule. The lowest Tafel slopes, which are characteristics of the HER mechanism and kinetics, were obtained with a hexaphenanthrene macrobicyclic complex 24 that is reported [60] to be a most efficient (pre)catalyst among these polyaromatic-terminated iron(II) clathrochelates.

The results of a testing [60] of the phenylboron-capped iron, cobalt and ruthenium cage complexes 22–24 shown in Fig. 7, the molecules of which have been designed for their efficient physisorption on carbon materials, in the semi-industrial water electrolysers, suggest the good performances of the corresponding clathrochelate-electro(pre)catalyzed hydrogen productions 2H+/H2, which are reported to be similar to those for the best known to date molecular catalysts used in an electrolysis cell, and to those of the promising non-platinum solid-state HER electrocatalysts as well. The use of the suitable carbon materials of a high surface area, such as activated carbon and reduced graphene oxide, as substrates for their efficient immobilization, caused a substantial increase in an electrocatalytic activity of the corresponding clathrochelate-containing CP-based cathodes of these electrolysers [60].

Clathrochelate-based photocatalysts for water splitting

Characterization of two photoelectrodes, including that surface-modified with a methylboron-capped cobalt hexachloroclathrochelate 28, and the study of their application to the hydrogen evolution reaction have been performed [61]. These photoelectrodes were prepared using a doped precursor Rh:SrTiO3 and its cobalt(II) clathrochelate-containing derivative Rh:SrTiO3–28 and the photoelectrochemical kinetics of the HER has been analyzed for these functionalized photoelectrodes based on strontium titanate under visible light irradiation. The kinetics of the photoelectrochemical water dissociation has been studied in this work using the open circuit photovoltage decay (OCPD) and photoelectrochemical impedance spectroscopy (PEIS) methods. Under open circuit conditions, the above cobalt cage complex is found [61] did not substantially affect the HER kinetics compared to the initial Rh:SrTiO3 semiconductor. But when a reverse bias was applied [61], a significant difference caused by presence of the clathrochelate has been observed. The rate constants of the charge transfer and the recombination processes were found [61] to be both affected. Therefore, the macrobicyclic cobalt-encapsulated species not only increased the rate of charge transfer, but also they are described [61] to play a role of the recombination centres for photoexcited minority carriers. The space charge capacitance has been determined [61] under the inversion conditions. Only under strong reverse bias it was found that, whereas the bulk Rh:SrTiO3 has a p-type conductivity, the surfaces of both the bare Rh:SrTiO3 and its cobalt clathrochelate-containing derivative Rh:SrTiO3–28 were found in this work to possess the properties of a n-type semiconductor.

Clathrochelate-based precatalysts for oxidative methane conversion

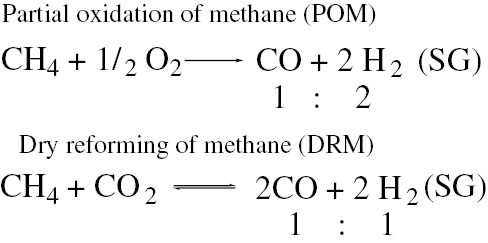

Two modern industrial methods of H2 production (Scheme 5) – the reactions of partial oxidation and dry reforming of methane (POM and DRM, respectively) – include the intermediate step of syngas formation. These methods are highlighted [62] as most prospective, environmental-friendly and cost-effective processes for syngas production.

Modern processes of oxidative methane conversion.

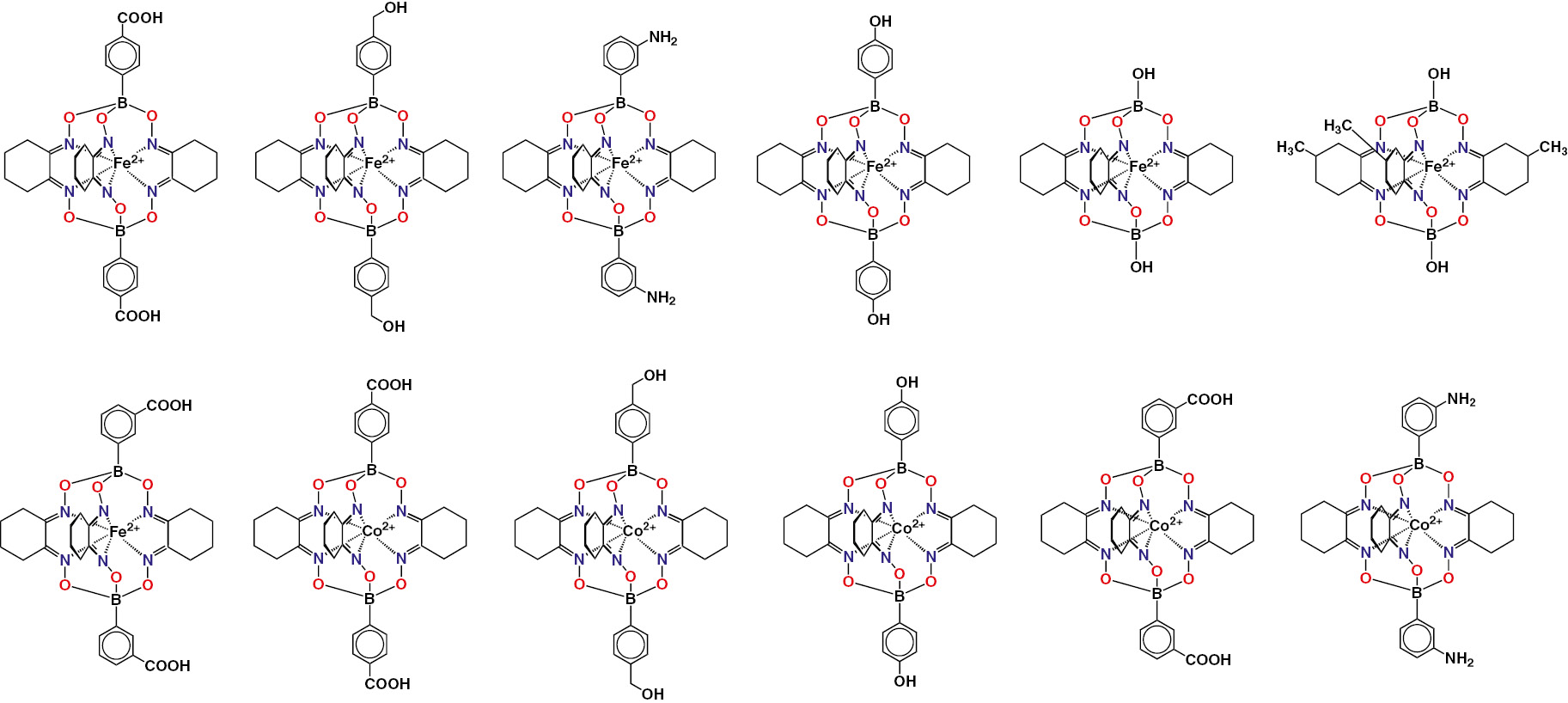

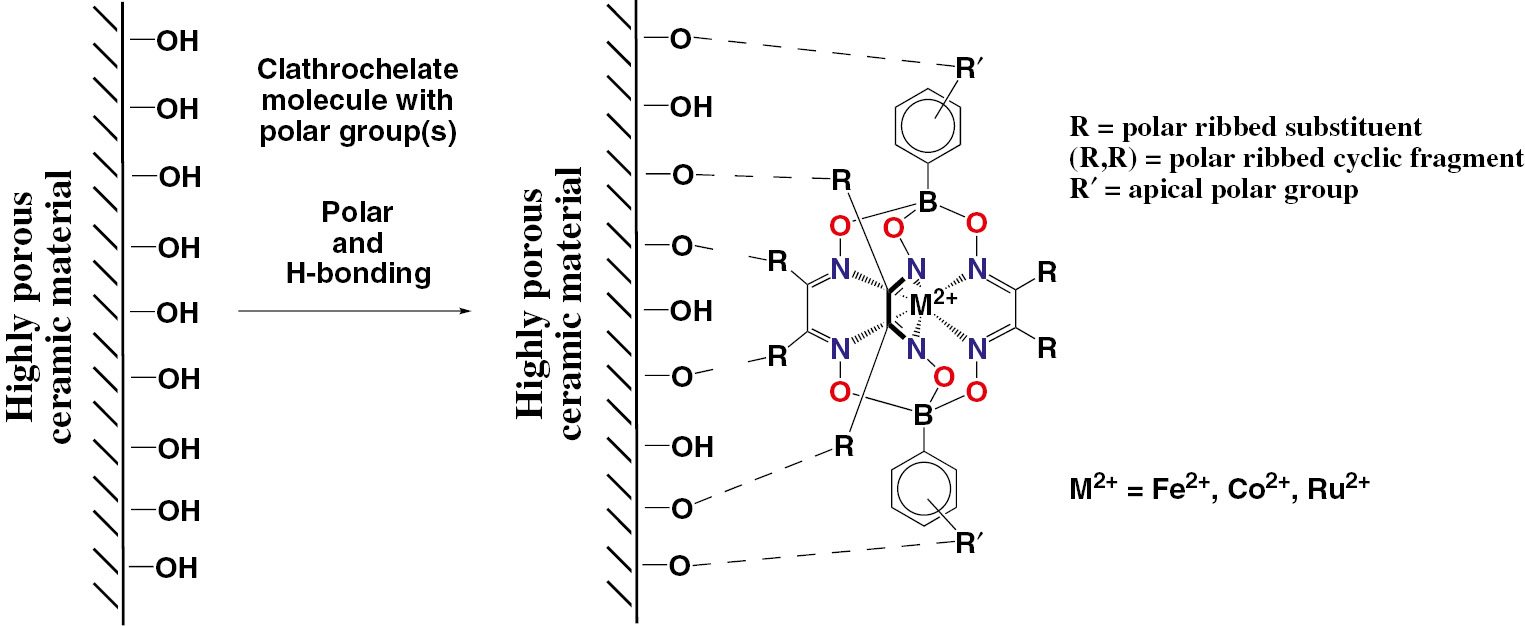

Chemical drawings of the clathrochelate iron and cobalt(II) complexes with terminal reactive (polar) groups, designed for their efficient adsorption on ceramic materials, are collected in Fig. 9; the general procedure of their template synthesis is shown in Scheme 6. Immobilization of the metal(II) clathrochelates on the surface of a highly porous ceramic material via, either their supramolecular interactions, or their covalent bonding, can be illustrated by Fig. 10 [28].

Chemical drawings of the iron and cobalt(II) clathrochelates with polar groups.

Synthesis of the metal(II) clathrochelates with terminal polar groups.

Immobilization of the metal(II) clathrochelates with terminal polar groups on a surface of ceramic materials.

The iron, cobalt and ruthenium clathrochelates 29–31 shown in Fig. 11, the molecules of which contain the terminal polar groups, have been immobilized [63] on a surface of highly porous ceramic material used as the support and a cobalt cage complex 32 without such a groups (as a control). The obtained hybrid clathrochelate-containing materials have been tested for a syngas production from CH4 using the above POM and DRM processes. These clathrochelate-based systems were found [63] do not catalyze the partial oxidation of CH4, while that based on an immobilized ruthenium(II) clathrochelate 31 was revealed as the active and selective catalytic material of dry reforming of CH4+CO2 mixture at the optimal temperatures close to 900°C into a syngas containing the equimolar amounts of H2 and CO (Fig. 12).

Chemical drawings of the tested iron, cobalt and ruthenium(II) clathrochelates.

Proceeding of DRM in the presence of a ruthenium-containing highly porous ceramic catalyst with an immobilized ruthenium(II) clathrochelate 31.

The obtained [63] results suggest that these metal(II) clathrochelates are only the precursors of single atom catalysts, in the case of which each of their catalytically active single sites is included in a matrix of its former encapsulating ligand that underwent a thermal decomposition under the reaction conditions used. Choice of their macrobicyclic ligands, designed for an efficient immobilization of their cage complexes on a surface of all the fibers of a given highly porous ceramic support, allowed to increase a surface concentration of the catalytically active centers (and, therefore, that a catalytic activity of a given ceramic material modified with these clathrochelates). Immobilization of the ruthenium(II) clathrochelate 31 as a precatalyst on the surface of a highly porous ceramic material used as the support allowed to obtain the active and selective catalytic material for the conversion of CH4+CO2 mixture into a syngas containing the equimolar amounts of H2 and CO.

Conclusions

Thus, the designed cage complexes with an encapsulated metal ion (clathrochelates) and the functional hybrid materials based on then were obtained and successful implemented as electro- and (pre)catalysis for molecular hydrogen and syngas production. These polyaromatic-terminated iron, cobalt and ruthenium clathrochelates, adsorbed on carbon cathode materials, were found to be the efficient electrocatalysts of the electrocatalytic HER, including those in PEM water electrolysers. They still cannot fully complete with metallic platinum for the moment, but their performances in these semi-industrial electrolysers are already encouraging. Their electrocatalytic activity in the HER was found to be affected by the number of the terminal polyaromatic group(s) per clathrochelate molecule. The lowest Tafel slopes, which are characteristics of the HER mechanism and kinetics, were obtained with the hexaphenanthrenyl-terminated macrobicyclic complexes. They possess the good performances of hydrogen production, which are similar to those for the best known to date molecular catalysts used in a PEM electrolysis cell and to those of the promising non-platinum solid-state HER electrocatalysts as well. The use of the suitable carbon materials of a high surface area, such as activated carbon and reduced graphene oxide, as the substrates for their efficient immobilization, allowed to substantially increase an electrocatalytic activity of the corresponding clathrochelate-containing carbon paper-based cathodes. In the case of the reaction of dry reforming of methane into syngas of a stoichiometry CO/H2 1:1, the designed metal(II) clathrochelates with terminal polar groups are only the precursors (precatalysts) of single atom catalysts, where each of their catalytically active single sites is included in a matrix of its former encapsulating ligand that underwent a thermal decomposition under the reaction conditions used. Choice of their designed ligands maintained an efficient immobilization of the corresponding cage metal complexes on the surface of highly porous ceramic material and allowed to increase a surface concentration of the catalytically active centers and, therefore, the catalytic activity of hybride materials modified with these clathrochelates. The obtained cage metal complexes and hybrid materials based on them operate under the principles of “green chemistry” and can be considered as efficient alternatives to some classical inorganic and molecular (pre)catalysts of these industrial processes.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry (Mendeleev-21), held in Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation, 9–13 September 2019.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed in the framework of Kurnakov Institute of General and Inorganic Chemistry RAS state assignment and financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100006769, grant 17-13-01468) and by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100002261, grant 18-29-23007). A.G.D. also thanks the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation for the financial support in the framework of the State task “Leading researchers to a permanent position”, project 4.6718.2017/ВУ (profile FSZE-2017-0008).

References

[1] A. J. Esswein, D. G. Nocera. Chem. Rev. 107, 4022 (2007).10.1021/cr050193eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, D. A. Komissarenko, G. N. Mazo, O. A. Shlyakhtin, K. V. Parkhomenko, A. A. Kiennemann, A.-C. Roger, A. V. Ishmurzin, I. I. Moiseev. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 489, 140 (2015).10.1016/j.apcata.2014.10.027Suche in Google Scholar

[3] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, V. K. Ivanov, M. A. Bykov, I. E. Mukhin, M. M. Lidzhiev, E. V. Rogaleva, I. I. Moiseev. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 461, 73 (2015).10.1134/S0012501615040028Suche in Google Scholar

[4] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, G. N. Mazo, D. A. Komissarenko, O. A. Shlyakhtin, I. E. Mukhin, N. A. Spesivtsev, I. I. Moiseev. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 462, 99 (2015).10.1134/S0012501615050012Suche in Google Scholar

[5] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, D. A. Komissarenko, K. V. Parkhomenko, A.-C. Roger, O. A. Shlyakhtin, G. N. Mazo, I. I. Moiseev. Fuel Process. Technol. 148, 128 (2016).10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.02.018Suche in Google Scholar

[6] I. V. Zagaynov, A. S. Loktev, A. L. Arashanova, S. V. Kutsev, V. K. Ivanov, A. G. Dedov, I. I. Moiseev. Chem. Eng. J. 290, 193 (2016).10.1016/j.cej.2016.01.066Suche in Google Scholar

[7] I. V. Zagaynov, A. S. Loktev, I. E. Mukhin, A. G. Dedov, I. I. Moiseev. Mendeleev Commun. 27, 509 (2017).10.1016/j.mencom.2017.09.027Suche in Google Scholar

[8] I. V. Zagaynov, A. S. Loktev, I. E. Mukhin, A. A. Konovalov, A. G. Dedov, I. I. Moiseev. Mendeleev Commun. 29, 22 (2019).10.1016/j.mencom.2019.01.006Suche in Google Scholar

[9] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, I. E. Mukhin, A. A. Karavaev, S. I. Tyumenova, A. E. Baranchikov, V. K. Ivanov, K. I. Maslakov, M. A. Bykov, I. I. Moiseev. Petroleum Chem. 58, 203 (2018).10.1134/S0965544118030052Suche in Google Scholar

[10] A. G. Dedov, O. A. Shlyakhtin, A. S. Loktev, G. N. Mazo, S. A. Malyshev, I. I. Moiseev. Dokl. Chem. 484, 16 (2019).10.1134/S0012500819010075Suche in Google Scholar

[11] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, V. P. Danilov, O. N. Krasnobaeva, T. A. Nosova, I. E. Mukhin, S. I. Tyumenova, A. E. Baranchikov, V. K. Ivanov, M. A. Bykov, I. I. Moiseev. Petroleum Chem. 58, 418 (2018).10.1134/S0965544118050055Suche in Google Scholar

[12] A. G. Dedov, A. S. Loktev, I. E. Mukhin, A. E. Baranchikov, V. K. Ivanov, M. A. Bykov, E. V. Solodova, I. I. Moiseev. Petroleum Chem. 59, 385 (2019).10.1134/S0965544119040042Suche in Google Scholar

[13] P. A. Jacques, V. Artero, J. Pecaut, M. Fontecave. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 20627 (2009).10.1073/pnas.0907775106Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] B. D. Stubbert, J. C. Peters, H. B. Gray. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18070 (2011).10.1021/ja2078015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] F. Lakadamyali, M. Kato, N. M. Muresan, E. Reisner. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9381 (2012).10.1002/anie.201204180Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] C. C. L. McCrory, C. Uyeda, J. C. Peters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3164 (2012).10.1021/ja210661kSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] X. Hu, B. S. Brunschwig, J. C. Peters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 8988 (2007).10.1021/ja067876bSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] X. Hu, B. M. Cossairt, B. S. Brunschwig, N. S. Lewis, J. C. Peters. Chem. Commun. 37, 4723 (2005).10.1039/b509188hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] M. Razavet, V. Artero, M. Fontecave. Inorg. Chem. 44, 4786 (2005).10.1021/ic050167zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] B. Carole, V. Artero, M. Fontecave. Inorg. Chem. 46, 1817 (2007).10.1021/ic061625mSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] J. P. Bigi, T. E. Hanna, W. H. Harman, A. Chang, C. J. Chang. Chem. Commun. 46, 958 (2010).10.1039/B915846DSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] W. R. McNamara, Z. Han, C.-J. Yin, W. W. Brennessel, P. L. Holland, R. Eisenberg. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 15594 (2012).10.1073/pnas.1120757109Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] C.-F. Leung, Y.-Z. Chen, H.-Q. Yu, S.-M. Yiu, C.-C. Ko, T.-C. Lau. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 36, 11640 (2011).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.06.062Suche in Google Scholar

[24] J. L. Dempsey, B. S. Brunschwig, J. R. Winkler, H. B. Gray. Accounts Chem. Res. A 42, 1995 (2009).10.1021/ar900253eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] V. S. Thoi, Y. Sun, J. R. Long, C. J. Chang. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2388 (2013).10.1039/C2CS35272ASuche in Google Scholar

[26] V. Artero, M. Fontecave. Coord. Chem. Rev. 249, 1518 (2005).10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.014Suche in Google Scholar

[27] V. Artero, M. Chavarot-Kerlidou, M. Fontecave. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7238 (2011).10.1002/anie.201007987Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] S. Losse, J. G. Vos, S. Rau. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 2492 (2010).10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.004Suche in Google Scholar

[29] M. T. D. Nguyen, A. Ranjbari, L. Catala, F. Brisset, P. Millet, A. Aukauloo. Coord. Chem. Rev. 256, 2435 (2012).10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.040Suche in Google Scholar

[30] V. S. Thoi, Y. Sun, J. R. Long, C. J. Chang. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2388 (2013).10.1039/C2CS35272ASuche in Google Scholar

[31] Y. Z. Voloshin, N. A. Kostromina, R. Kraemer. Clathrochelates: Synthesis, Structure and Properties, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2002).Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Y. Z. Voloshin, I. G. Belaya, R. Kraemer. Cage Metal Complexes: Clathrochelates Revisited, Springer, Heidelberg (2017).10.1007/978-3-319-56420-3Suche in Google Scholar

[33] H. Ozawa, M. Haga, K. Sakai. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4926 (2006).10.1021/ja058087hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] M. Wang, Y. Na, M. Gorlov, L. Sun. Dalton Trans. 33, 6458 (2009).10.1039/b903809dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] S. Varma, C. E. Castillo, T. Stoll, J. Fortage, A. G. Blackman, F. Molton, A. Deronzier, M. N. Collomb. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 17544 (2013).10.1039/c3cp52641kSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] P. Du, J. Schneider, G. Luo, W. W. Brennessel, R. Eisenberg. Inorg. Chem. 48, 4952 (2009).10.1021/ic900389zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] C. S. Letko, J. A. Panetier, M. Head-Gordon, T. D. Tilley. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9364 (2014).10.1021/ja5019755Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] O. Pantani, S. Naskar, R. Guillot, P. Millet, E. Anxolabéhère-Mallart, A. Aukauloo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 9948 (2008).10.1002/anie.200803643Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] G. N. Schrauzer, R. J. Holland. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 1505 (1971).10.1021/ja00735a040Suche in Google Scholar

[40] J. T. Muckerman, E. Fujita. Chem. Commun. 47, 12456 (2011).10.1039/c1cc15330gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] B. H. Solis, S. Hammes-Schiffer. Inorg. Chem. 50, 11252 (2011).10.1021/ic201842vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] D. I. Kochubey, V. V. Kaichev, A. A. Saraev, S. V. Tomyn, A. S. Belov, Y. Z. Voloshin. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 2753 (2013).10.1021/jp3085606Suche in Google Scholar

[43] M. Antuch, A. Ranjbari, S. A. Grigoriev, J. Al-Cheikh, A. Villagrá, L. Assaud, Y. Z. Voloshin, P. Millet. Electrochim. Acta 245, 1065 (2017).10.1016/j.electacta.2017.03.005Suche in Google Scholar

[44] E. Anxolabéhère-Mallart, C. Costentin, M. Fournier, S. Nowak, M. Robert, J. M. Savéant, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6104 (2012).10.1021/ja301134eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] S. El Ghachtouli, M. Fournier, S. Cherdo, R. Guillot, M. F. Charlot, E. Anxolabéhère-Mallart, M. Robert, A. Aukauloo. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 17073 (2013).10.1021/jp405134aSuche in Google Scholar

[46] D. C. Lacy, G. M. Roberts, J. C. Peters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4860 (2015).10.1021/jacs.5b01838Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] C. Costentin, H. Dridi, J. M. Saveant, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13727 (2014).10.1021/ja505845tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Y. Z. Voloshin, V. V. Novikov, Y. V. Nelyubina, A. S. Belov, D. M. Roitershtein, A. Savitsky, A. Mokhir, J. Sutter, M. E. Miehlich, K. Meyer. Chem. Commun. 54, 3436 (2018).10.1039/C7CC09611ASuche in Google Scholar

[49] Y. Z. Voloshin, O. A. Varzatskii, I. I. Vorontsov, M. Yu. Antipin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3400 (2005).10.1002/anie.200463070Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Y. Z. Voloshin, A. V. Dolganov, O. A. Varzatskii, Y. N. Bubnov. Chem. Commun. 47, 7737 (2011).10.1039/c1cc12239hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Y. Z. Voloshin, A. S. Belov, A. V. Vologzhanina, G. G. Aleksandrov, A. V. Dolganov, V. V. Novikov, O. A. Varzatskii, Y. N. Bubnov. Dalton Trans. 41, 6078 (2012).10.1039/c2dt12513gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] A. V. Dolganov, A. S. Belov, V. V. Novikov, A. V. Vologzhanina, A. Mokhir, Y. N. Bubnov, Y. Z. Voloshin. Dalton Trans. 42, 4373 (2013).10.1039/c3dt33073gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] A. V. Dolganov, A. S. Belov, V. V. Novikov, A. V. Vologzhanina, G. V. Romanenko, Y. G. Budnikova, G. E. Zelinskii, M. I. Buzin, Y. Z. Voloshin. Dalton Trans. 44, 2476 (2015).10.1039/C4DT03082FSuche in Google Scholar

[54] A. V. Dolganov, I. G. Belaya, Y. Z. Voloshin. Electrochim. Acta, 125, 302 (2014).10.1016/j.electacta.2014.01.060Suche in Google Scholar

[55] S. A. Grigoriev, A. S. Pushkarev, I. V. Pushkareva, P. Millet, A. S. Belov, V. V. Novikov, I. G. Belaya, Y. Z. Voloshin. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42, 27845 (2017).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.05.048Suche in Google Scholar

[56] O. A. Varzatsky, D. A. Oranskiy, S. V. Vakarov, N. V. Chornenka, A. S. Belov, A. V. Vologzhanina, A. A. Pavlov, S. A. Grigoriev, A. S. Pushkarev, P. Millet, V. N. Kalinichenko, Y. Z. Voloshin, A. G. Dedov. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42, 27894 (2017).10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.05.092Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Y. Z. Voloshin, N. V. Chornenka, O. A. Varzatskii, A. S. Belov, S. A. Grigoriev, A. S. Pushkarev, P. Millet, V. N. Kalinichenko, I. G. Belaya, M. G. Bugaenko, A. G. Dedov. Electrochim. Acta 269, 590 (2018).10.1016/j.electacta.2018.03.030Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Y. Z. Voloshin, N. V. Chornenka, A. S. Belov, S. A. Grigoriev, A. S. Pushkarev, P. Millet, V. N. Kalinichenko, D. A. Oranskiy, A. G. Dedov. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, H598 (2019).10.1149/2.0391913jesSuche in Google Scholar

[59] Y. Z. Voloshin, N. V. Chornenka, A. S. Belov, S. A. Grigoriev, A. S. Pushkarev, P. Millet, V. N. Kalinichenko, I. G. Belaya, M. G. Bugaenko, A. G. Dedov. Macroheterocycles 11, 449 (2018).10.6060/mhc181008vSuche in Google Scholar

[60] Y. Z. Voloshin, V. M. Buznik, A. G. Dedov. ХХI Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry, Abstracts Book of 2a, Saint Petersburg, 43 (2019).Suche in Google Scholar

[61] M. Antuch, P. Millet, A. Iwase, A. Kudo, S. A. Grigoriev, Y. Z. Voloshin. Electrochim. Acta 258, 255 (2017).10.1016/j.electacta.2017.10.018Suche in Google Scholar

[62] I. I. Moiseev, A. S. Loktev, O. A. Shlyakhtin, G. N. Mazo, A. G. Dedov, Petroleum Chem. 9, 169 (2019).Suche in Google Scholar

[63] A. G. Dedov, Y. Z. Voloshin, A. S. Belov, A. S. Loktev, A. S. Bespalov, V. M. Buznik, Mendeleev Commun. 29, 669 (2019).10.1016/j.mencom.2019.11.022Suche in Google Scholar

©2020 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- Research papers from the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Conference papers of the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Unusual behavior of bimetallic nanoparticles in catalytic processes of hydrogenation and selective oxidation

- Soft chemistry of pure silver as unique plasmonic metal of the Periodic Table of Elements

- Catalytic hydrogenation with parahydrogen: a bridge from homogeneous to heterogeneous catalysis

- Azidophenylselenylation of glycals towards 2-azido-2-deoxy-selenoglycosides and their application in oligosaccharide synthesis

- Bis-γ-carbolines as new potential multitarget agents for Alzheimer’s disease

- Octafluorobiphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate as a ligand for metal-organic frameworks: progress and perspectives

- Some aspects of the formation and structural features of low nuclearity heterometallic carboxylates

- Particular kinetic patterns of heavy oil feedstock hydroconversion in the presence of dispersed nanosize MoS2

- Concentration profiles around and chemical composition within growing multicomponent bubble in presence of curvature and viscous effects

- Application of gold nanoparticles in the methods of optical molecular absorption spectroscopy: main effecting factors

- Membrane materials for energy production and storage

- New types of the hybrid functional materials based on cage metal complexes for (electro) catalytic hydrogen production

- Conference paper of the 15th Eurasia Conference on Chemical Sciences

- Discovery of bioactive drug candidates from some Turkish medicinal plants-neuroprotective potential of Iris pseudacorus L.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- Research papers from the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Conference papers of the 21st Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry

- Unusual behavior of bimetallic nanoparticles in catalytic processes of hydrogenation and selective oxidation

- Soft chemistry of pure silver as unique plasmonic metal of the Periodic Table of Elements

- Catalytic hydrogenation with parahydrogen: a bridge from homogeneous to heterogeneous catalysis

- Azidophenylselenylation of glycals towards 2-azido-2-deoxy-selenoglycosides and their application in oligosaccharide synthesis

- Bis-γ-carbolines as new potential multitarget agents for Alzheimer’s disease

- Octafluorobiphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate as a ligand for metal-organic frameworks: progress and perspectives

- Some aspects of the formation and structural features of low nuclearity heterometallic carboxylates

- Particular kinetic patterns of heavy oil feedstock hydroconversion in the presence of dispersed nanosize MoS2

- Concentration profiles around and chemical composition within growing multicomponent bubble in presence of curvature and viscous effects

- Application of gold nanoparticles in the methods of optical molecular absorption spectroscopy: main effecting factors

- Membrane materials for energy production and storage

- New types of the hybrid functional materials based on cage metal complexes for (electro) catalytic hydrogen production

- Conference paper of the 15th Eurasia Conference on Chemical Sciences

- Discovery of bioactive drug candidates from some Turkish medicinal plants-neuroprotective potential of Iris pseudacorus L.