Abstract

Ever since cartoons were created as a medium of political and social commentary, they have been used to both criticize and uplift religious communities. The anti-Catholic cartoons of Thomas Nast and Jack Chick are easily recognizable, but interestingly, among twenty-first-century Catholic communities in Europe and the United States, Catholics themselves have been creating caricatures of Pope Francis, a more left-leaning pope in favor of reinforcing post-Second Vatican Council modernizations. These digital cartoons are tangible examples of a radically traditional antagonistic Catholic counter-public. This study delves into how radical traditional Catholic communities, who argue that pre-Vatican II traditions are a more authentic form of Catholicism than that encouraged by the current Pope Francis, are using cartoons to voice their agenda. By drawing from discourse theoretical analysis and hermeneutics, we identify four themes of criticism and discontent surrounding the pope: exposing his “bad agency,” ridiculing papal values, unveiling Francis’ “polarized and unbalanced” behavior, and expressing his predatory attitude toward representatives of Catholic traditionalism. Ultimately, we see these cartoons as the product of an antagonistic and anti-Pope Francis force internal to the Church, hypermediation without sources to public actions, and the digital milieu based on modernity in technology.

1 Introduction

Throughout the two millennia history of the Roman Catholic Church, cartoons have served as a form of anti-Catholic criticism from outside of the Church. Whether as a form of blatant anti-Catholicism, or combined with xenophobia aimed at Irish, Italian, Latinx, or Slavic communities, these cartoons serve as visual documentation of popular attitudes surrounding Catholic communities. These cartoons, however, are strikingly different from those released since Pope Francis’s election in March 2013, created by Catholics who consider themselves part of the Roman Catholic Church, yet disagree with the current pope and do not consider him the true leader of the Catholic Church. There is a clear distinction between non-Catholic anti-Catholicism, as in the case of anti-Irish cartoonist Thomas Nast and internal critiques of Catholic orthodoxy and traditionalism produced by members of the Church itself. This article attempts to unpack how these contemporary digital cartoons reflect internal Church polemics and can serve as sources to examine radically traditional, or Tridentine, Catholic subcultures.

Starting from Leonardo da Vinci’s artistic explorations of deformity and Martin Luther’s massive use of visual propaganda, cartoons had been viewed as a visual means of resistance to the Catholic authority and its social order.[1] Thus, as early as the sixteenth century, a genre of popular cartoons influencing public opinion on significant political and religious matters had taken shape. The most common trope in this genre involves simultaneously parodying individuals and using allusions.[2] While scholar Francis Betten argues that few men made such an extensive use of the art of printing for the promotion of his anti-Catholic doctrine as did Martin Luther,[3] anti-Catholic cartoons have existed since the inception of the art form. Further evidence of this traces back to the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829 in England and the high church Oxford Movement.

In the 1830s and 1840s, Punch published three decades of anti-Catholic cartoons centered on the “Papal Aggression” of 1850, in which Pope Pius IX restored the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England since the reign of Henry VIII with Cardinal Wiseman as the first Archbishop of Westminster.[4] In the mid to late nineteenth century around the same time that Punch was publishing its cartoons, Thomas Nast combined growing anti-Catholic with anti-Irish sentiment, caused in part by a growing culture clash with Irish immigration in the early 1800s.[5] Although Nast is called the father of modern political cartoons,[6] evangelist and cartoonist Jack T. Chick is best known today for producing “Chick tracts,” or 24-page anti-Catholic black-and-white comic books.[7] These anti-Catholic cartoons, however, represent one type of external political satire aimed at religious institutions. This article focuses on another form of political satire internal to religious institutions, situating this study within the field of political cartoons.

1.1 Evolution of Religion Cartoons in Use

Digital media and its associated visual cultures represent one channel through which people come to value or devalue religious institutions.[8] Ever since digital spaces came to be they have affected religious institutions and practices,[9] and while it may feel compelling to situate this study of anti-Pope Francis cartoons within Digital Religion Studies (at the intersection of Internet and media, religion, and cultural studies), the authors are not focusing on how these cartoons are affecting digital spaces of practice and worship (as in the case of live-streamed Masses during the COVID-19 pandemic) but on how cartoons shared on a publicly accessible website (Gloria.tv) represent religiously affiliated political propaganda internal to the religious institution itself. Religion and secularism and part of all digital visual culture, from internet memes[10] to religious advertisements,[11] but not all comments on the political stability and organization of religious institutions. Political cartoons serve as a key genre of media content for expressing conflicting opinions[12] for four basic functions, as cited by Chicago Tribune’s cartoonist Dick Locher: entertainment, aggression reduction, agenda setting, and framing.[13]

In modern times, religious cartoons resonating across a wide range of the Western world were associated, among others, with minority Christian denominations and the satirical cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. On the one hand, the so-called “Mormon problem” (Mormon polygamy and their social and political control in the West) shows that constant attention to and dissection of cartoons may contribute to the removal of controversial religious practices.[14] On the other hand, public pushback concerning cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad published by the Danish Jyllands-Posten indicates how complex the social ramifications of blasphemous humor are.[15] The Danish cartoons scandal lit the fuse for acts of violence but also introduced “a new vocabulary for thinking about global and domestic relations among faith groups and the importance of religion in international relations.”[16] Following the domestication strategy, they made Islam read-only in familiar Western associations.[17] Ultimately, the scandal resonated throughout the world, demonstrating the progressive mediatization of religion.[18]

The case of Charlie Hebdo shows that the advent of a hybrid media environment strengthened the tension toward religious satire in cartoons and accelerated new perspectives of mediated piety associated with digital activism and viral pictures. When considering digital activism, the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris, following the publication of the satirical cartoons of Muhammad, transferred the attention of both media outlets and individuals into digital mourning, expressed with the hashtag #jesuischarlie.[19] Speaking the viral declaration “Je suis Charlie” (“I am Charlie”) was a “performance of affective citizenship in the name of social cohesion.” Simultaneously, it forced the process of constructing “affect aliens.”[20] As a result, digital cartoons have opened up the debate on accommodating the alien in a shared symbolic space.

1.2 Turning Up the Antagonism

The work published to date that critically reflects cartoons concerning religion is strikingly similar to studying antagonism in terms of discourse theory.[21] It means that antagonism results here from the fundamental distinction of the political sphere into political and politics.[22] The former refers to an “ontological dimension of radical negativity,”[23] while the latter concerns “the ensemble of practices and institutions whose aim is to organize human coexistence.”[24] Therefore, the social space is based on conflicts between the parties present in it, which result from natural differences in opinions, interests, and aspirations.

Since a full consent situation is not practically achievable in this context, differences can only be overcome by consensus. In the absence of such a consensus, the clash between different sides may lead to antagonism, understood as a “confrontation between non-negotiable moral values or essential forms of identification.”[25] Laclau and Mouffe argue that when antagonism of this form appears, the parties mutually contradict their opponents’ recognition and only a small boundary separates them from denying each other their raisons d’etre.[26] When one of the parties wins, it articulates its hegemonic practices and, in an extreme way, suppresses the discourses of its opponents.

1.3 Pope Francis as a Discursive Opponent

Laclau and Mouffe’s approach to discourse relates to the context of liberal democracy.[27] It turns out, however, that it describes the situation we are investigating quite well. In the global Catholic Church, there are many different trends and conflicting positions regarding the pope and the way he exercises his papal office. The collegiality of bishops, understood as the beginnings of public opinion in the Church,[28] allows us to look at this institution in the light of discourse theory. In this context, the pope becomes the subject of a conflict whose dynamics are expressed in discursive practices.

We have a very special situation here. This discourse involves strictly religious propaganda, characteristic of authoritarian systems and thus rejecting democratic compromise; however, it is being carried out in a politically democratic environment that guarantees freedom of speech. The Catholic Church authorities have no legal means of silencing or meaningfully punishing the creators of these cartoons.

The conflict here is generally founded on two differing visions of Catholicism. We will use the language of Mouffe,[29] who defines it as holding to “non-negotiable values” in the field of religious truth about God. These past few years of Francis’ pontificate also show an increase in tensions between the two viewpoints. One of these groups represents Catholicism before the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). It is based on the exclusivity of the Church as the perfect community of believers in Christ immersed in the practices of the pre-conciliar Latin liturgy, including traditional devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary and the saints.[30] This trend clearly distances itself from participation in ecumenical and inter-religious dialogue. For these Catholics, every pope is the vicar of Christ on Earth and the only person responsible to God for the Catholic Church and its teachings: it is the pope who upholds God’s unchanging law. Nevertheless, in practice, they express a generally ambiguous attitude toward the current popes of the post-Vatican II era.

On the one hand, criticizing Benedict’s decision to step down from the Petrine office without returning to his position as cardinal, they recognize very positive actions in the pontificate of this pope. These include the partial return to the Latin language during papal liturgies, the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum from July 2007 releasing the Tridentine Mass, and the removal of ex-communication from the bishops of the Confraternity of St. Pius X.

On the other hand, they contest Pope Francis by seeing him as a bad agent of modernism in the Catholic Church. In doing so, they point out that Francis is revoking the mandates given by Benedict, bringing the Tridentine Mass to the margins, and proposing social inclusivity and religious pluralism that contradicts traditional Church teaching. For some of this group, there is even talk of sedevacantism emerging from the election of Pope Francis in violation of the 2013 conclave rules.

The second group was formed as a result of the decisions of the Second Vatican Council. It assumes that a Christian’s life is a pilgrimage entirely embedded in specific contexts that determine the way in which the basic principles of the faith are negotiated.[31] Salvation occurs in the community of the Church to which all people belong in various ways, and this includes followers of other Christian denominations and religions.[32] This viewpoint perceives the pope’s role mostly as being a leader, historically associated with the ministry of the Bishop of Rome. Thus, the pope is not the guardian of the objective law of God; rather, he interprets the Gospel in the context of current Christian life. The liturgy is based on rituals spoken in national languages. This group’s attitude toward other Christian denominations and other religions is a result of dialogue.

In its most radical mode, part of the traditional group takes the form of so-called “Catholic resistance” or “filial resistance” and regards the post-Vatican II Church and the pontificate of Pope Francis:

“Resistance” is not a purely verbal declaration of faith but an act of love towards the Church, which leads to practical consequences. Those who resist are separated from the one who has caused the division in the Church, they criticize him openly, they correct him.[33]

Thus, the resistance strategy describes an action of formative criticism originating in the common care for the unity of the religious institution. We can explore its shades by quoting its representative regarding limitations on the Latin mass: “Persistence, presence, making attempts to influence the bishops are, it seems, necessary things in the current situation.”[34] Therefore, constructive criticism and applied persuasion constitute the basis of the described resistance.

1.4 Gloria.tv Context

We provide answers to the research questions by analyzing source material manually obtained from the English version of the Gloria.tv website. The collected materials are then embedded in the MAXQDA software environment, where the final analysis takes place. The sample includes 452 digital cartoons published between January 22, 2018, and July 27, 2021. The first date indicates the inauguration of the cartoon series, and the second relates to cartoons commenting on the publication of the papal document Traditionis Custodes, which contained new norms regarding the celebration of the pre-conciliar mass. Each of the cartoons is accompanied by a bubble in which appears the characters from the illustrations or a commentary on the contents.

In this study, we analyze a body of digital cartoons commissioned by Gloria.tv. The selection of this case study was based on the platform’s importance in circulating content among Catholics who are reluctant toward Pope Francis and the institutions of the Catholic Church implementing the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

The Gloria.tv platform, founded in Switzerland in 2005 by Catholic priests Reto Nay and Markus Doppelbauer, has changed its headquarters many times. One reason for this is its anti-Semitic rhetoric. Since 2017, Gloria.tv has been edited in Dover, USA, and since 2019, it has been hosted by Church Social Media Inc. Gloria.tv is a peculiar case of a multilingual video portal. It develops a strict counter-public against Pope Francis. In addition to its videos and links to other YouTube videos, it publishes and makes available texts and cartoons aimed at exposing post-conciliar abuses in the Catholic Church and Francis’ “bad agency.” In this way, the platform can be seen both as existing in an environment that antagonizes church content and as a source of resistance against the pope himself.

Although the multilingual platform is populated with posts from people across the world, the account news posts most frequently. En.news is based in Los Angeles, California, and was started on April 27, 2017. The ultra-conservative cartoon branch of en.news – en.cartoon – is where this study draws all of its cartoons. Founded on January 17, 2018, the account shares digitally made cartoons with copyright belonging to glovia.tv. En.cartoon’s following is second largest on Gloria.tv at 74 followers, second only to en.news which has 206 followers. As of May 10, 2023, 697 pictures (mostly cartoons) were posted. Despite how widely these cartoons are then disseminated on the web, the number of people clicking on posts is small (with most posts receiving 1.1k to 1.4k engagements).

Most Gloria.tv accounts posting content are based in North America, specifically the United States and Canada. One of the accounts is Canon212, which joined Gloria.tv on September 4, 2020, and runs Canon212.com, News of the Church and the World. This news outlet, christened by a Patriarchal Cross as its logo, is traditionalist Catholic in the content it posts along with affiliated with the American Far-Right politically. Some of the creator’s recent articles include, “Is it Possible that Francis, Vatican II & America Magazine were Deep State CIA Operations?” and “Gay St. Paul the Apostle Francis Church yanks ‘God is Trans’ exhibit after archdiocese launches probe.” Other accounts that post frequently include La verdad prevalence (California), Knights4Christ (Colorado), and John333 (based in Canada). Almost all of these accounts were created within the last three years.

As en.cartoon is based in the United States along with en.news, these cartoons are a visual representation of American intra-Catholic resistance. In the United States, radical traditionalist Catholics are also increasingly aligning themselves with Far-Right American conservatism and by extension, Christian nationalism. Examining these cartoons will isolate what messaging about Pope Francis is being disseminated to the United States and beyond and will also shed light on current intra-religious disputes with the Catholic Church in the United States.

1.5 Methods and Research Question

We base our study on a combination of discourse theoretical analysis (DTA)[35] and hermeneutics.[36] Regarding the former method, we assume that the production of cartoons is an expression of the articulation of specific discourses that antagonize potential recipients through heterodoxy in looking at the pope. In relation to the latter method, we aim to find the precise meaning hidden in the diffusion of this heterodoxy.

The selected methods carry specific epistemological assumptions. DTA represents a macro textual and macro contextual approach to discourse.[37] First, it is based on the belief that the object of discourse functions in the social space as articulated by discourse participants thrown into a specific social context. In the case of our study, Pope Francis is therefore an expression of the articulation of the editors and cartoonists of Gloria.tv, who, as a rule, operate based on their suspicions regarding whatever is new in the Church. Since DTA does not have a specific procedure and is highly arbitral,[38] we implemented it in two stages. First, we started qualitative content analysis on the data, with iterative cycles of breaking down the digital cartoons into 166 codes in-vivo collected in the MAXQDA software. These in-vivo codes answered the position of Pope Francis and the types of resistance to his person and agency.

The DTA second assumption implies that there is a clash between the participants.[39] Because the discourse is always just partially fixed, the state of tension resulting from the articulation of opposing aspirations and ideas creates a dynamic environment of antagonism between the participants of the process. In our case, we narrowed the in-vivo codes to general nodal points, linking the different categories into content clusters with similar meanings related to the Pope. Within these clusters, we tried to discern how the Pope is articulated and in position to whom. What is important, the articulation of an analytical framework consisting of nodal points was not the simple summary of the most common codes. We evaluated the codes manually in order to identify nodal points as specific elements of the discourse that stabilized its articulation. This was possible because the DTA relates to a democratic space where the existence of the “other” is not in itself questioned. At most, it appears in the form of extreme antagonism.

In the case of resistance, we supplemented this approach with hermeneutics, treating the discursive practices that pursue destructive judging against the pope as textual exegesis[40] adapted to the digital environment.[41] Our aim here was to evaluate each of 452 digital cartoons through the application of data hermeneutics based on the procedures of (1) approaching a relatively small dataset, and (2) a close data reading that helped to open up the meaning of the cartoons. Respecting that the digital environment has its own ontology, we approached the general process of information flow realization through material digital cartoons[42] with correspondence to sequentiality and taking the literal meaning of a text seriously in the analysis.[43] This meant that several times returning to close reading concerned the digital form of cartoons on three successive levels: semantic, reflective, and ontological.[44] Then, we used memos obtained from this process to supplement the DTA.

In this article, we undertake an analysis of digital cartoons about Pope Francis available on the traditionalist Catholic web platform, Gloria.tv focused on addressing one central question:

RQ1: How is Catholic resistance articulated in digital cartoons?

To address this question, we build on research from the field of communication and specifically studies on cartoons present in printed press and digital media. Then, we link that with the contextualization of Catholic resistance seen from the perspective of discourse theory, which highly exposes the idea of antagonism.

2 Results

The cartoons published by Gloria.tv were examined discursively and hermeneutically to answer questions about the articulation of resistance. In the abductive reasoning process, we established nodal points of the most relevant issues present in codes. We included this result within the five nodal points (NPs), which scaffold the studied discourse and give it certain stability: (NP1) the pope rules and uses others based on 37 codes; (NP2) the pope functions in various contexts of LGBT issues based on 12 codes; (NP3) the pope supports idolatry based on 20 codes; (NP4) the pope displays immaturity based on 17 codes; and (NP5) the pope is destroying everything based on 40 codes. The 40 codes did not support any of the nodal points meaning that they appeared in the content but did not refer to nodal points, understood as central terms responsible for stabilizing the discourse. While Table 1 indicates the main categories collected under the umbrella of each nodal point, the specific features of each of these NPs require additional discussion.

The first ten categories included in the nodal points of the discourse

| NP2 the pope functions in various contexts of LGBTQIA+ issues | NP3 the pope supports idolatry | NP4 the pope is characterized by immaturity | NP5 the pope is destroying everything | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cardinals praising pope’s actions | 68 | LGBTQIA+ symbol | 50 | Pope supports idolatry | 49 | Pope is immature | 35 | Pope supports tradition destroyers and destroys tradition | 33 |

| 2 | Cardinals concerned about the pope’s actions | 31 | Pope supports LGBTQIA+ | 22 | Pope is a heretics | 17 | Clapping cardinal supporter | 22 | Pope tearing down Church (dividing with shovel, smashing) | 32 |

| 3 | The pope is a despot | 17 | Insulting gays | 3 | Pope acts for the sake of applause | 21 | The church is being destroyed | 24 | ||

| 4 | Ordinary priests are afraid of the pope | 16 | St. Basil the Great condemns cardinal molester of men | 2 | Pope supports other faiths and religions | 12 | Pope cloaks himself before politicians | 8 | Traditional liturgy is being contested | 20 |

| 5 | Kicking out the opponent’s cardinal | 11 | St. Paul performs traditional wedding | 1 | Francis’ inculturation | 6 | Pope lies | 5 | Pope plans assault on celibacy | 15 |

| 6 | Pope’s action on global warming | 7 | Slaughter of innocents averted with transgenderism | 1 | Church is a dump of heresy | 3 | St. Peter is wringing his hands over Francis | 2 | Pope violates the Eucharist | 13 |

| 7 | Ordinary people are not with Francis | 6 | St. Nicholas Flue announces that church allows perversions | 1 | Jesus chastises/punishes pope | 3 | Pope is a clown | 2 | The Church during and after a pandemic | 11 |

| 8 | Ordinary people do not follow the pope | 6 | St. Peter Damian attacks sodomy | 1 | Virus the new god of Francis | 1 | Mary saves the pope | 1 | The devil is winning in the Church | 11 |

| 9 | Pope doesn’t listen to cardinals | 6 | St. Augustine later condemns homosexuality | 1 | Pope confesses to pakmas | 1 | Pope wants vaccine for schism | 1 | Pope glorifies the Reformation | 9 |

| 10 | Pope harms cardinal(s) | 6 | St. Catherine condemns homosexuality | 1 | Devil has occupied the altar | 1 | Pope doesn’t read anything | 1 | Pope has become a politician, buried the office | 8 |

2.1 Nodal Points

A discourse inherently possesses contingency. For the social and religious phenomena that are articulated here, their stabilizers in the form of NPs give consistency to all the ideas they contain and the strategies accompanying this articulation.

The first of these NPs, NP1 the pope rules and uses others, refers to a key characteristic feature of the pope, which is his agency within a certain hierarchy. It states that the pope oversees the people of the Church, whom he rules ruthlessly. At the same time, this is done within the political establishment he serves. A pope rarely works alone, and in many of these cartoons, Francis’ agency takes place in the presence of or with the support or mediation of the cardinals. Operating in the company of at least one other person indicates that he delegates assignments; he is a figure focused on authority through collective actions. Within NP1, the weakness of the pope’s support group is exposed. The cardinals who work with him are often depicted as claquers and financial embezzlers (e.g., Cardinal Marx and Becciu), or small clowns (as in the case of Cardinal Tagle).

NP2 focuses on the idea that the pope functions in various contexts of LGBTQIA+ issues. However, this theme has a dual dimension. On the one hand, it relies on images and texts that reveal Francis’ support for sexual minorities and their social and religious rights. On the other hand, it exposes the symbol of the LGBTQIA+ movement as identifying specific people and values. By displaying a rainbow flag on a character’s cheek or sock, the cartoon creators identify representatives of minorities and values that contradict conventional Catholic moral teachings and the traditional vision of the family.

NP3, the pope supports idolatry, refers to the ways in which Francis tries to combine Catholicism with multiculturalism and religious diversity. Within this theme, Francis’ deep sensitivity to the possibility of experiencing the faith in non-European terms is reduced to idolatry. Inculturation, especially present in the figure of Pachamama (Mother Earth), serves as an argument that the pope worships foreign gods. However, the fact is that the creators of the portal are expressing Eurocentrism and racism.

The discourse set by NP4 that the pope is characterized by immaturity is the basis for personal attacks on Francis. This theme is associated with the specific portrayal of Francis as surrounding himself with flatterers, being a power-hungry tyrant, a liar (with Pinocchio’s nose), a narcissist, a haughty man, and a hypocrite, even suspected of being mentally ill, who only talks about dialogue and, in fact, hates opposition. Finally, NP5, the pope is destroying everything, flows from two interconnected elements. The first is that the pope is destroying the Church’s traditions and everything connected with it. It is about those who oppose Francis in defense of tradition, the prophecies of saints that reveal the future apostasy of the Church from God, and his depreciating the old rite of the mass. The second element indicates that innovations announced or implemented by the pope will end in a catastrophic collapse of the Catholic Church.

These NPs not only stabilize the discourse present in the Gloria.tv cartoons, but also facilitate the process of its radicalization, which consists in the articulation of resistance. For each NP, the dynamic of this process takes on a specific character, which, in combination with hermeneutics, serves to articulate their meaning.

2.2 Hermeneutics

The hermeneutical approach adopted for analyzing the cartoons led to two distinct collections of arrangements. On one hand, utilizing hermeneutics in social study, with a focus on the digital phenomenon of religious cartoons, presents a challenge due to the usage of vague and fluid categories from philosophical hermeneutics. This creates a contradiction between subjective and objective ontology, posing a real problem for cross-disciplinary research encompassing media studies and theology. On the other hand, embracing hermeneutics and integrating it into its circle allow for the establishment of new perspectives beyond rough and static data-driven categories. This aids in comprehending the overall context of the study. Rather than explaining the data, they assist in elucidating our approach to the social reality and the content of the investigated Roman Catholic Church’s papacy. As a result, this procedure leads to a twofold description that highlights the general tendencies of the analyzed social reality, particularly its religious aspects.

First, digital cartoons from the ultra-conservative Gloria.tv site defend the stance that the Church’s tradition and doctrine should be understood fundamentally, i.e., as eternal, timeless, and changeless. Its most important elements are the absolute character of the commandments and principles of moral theology, a literal reading of the punishment of hell, and the Latin liturgy as an unchanging liturgy. Under this view, only traditional Catholics possess an objective, and unchangeable truth and is based on logic in the sense of mathematical logic. From this follows that any dialogue is a compromise. Any inconsistency is viewed as evidence of an error. As far as the life of the Church is concerned, ecumenism is the act of gently inducing other Christians to return to the bosom of Catholicism (ecumenism of return).

Second, the cartoons on Gloria.tv reject Francis’ position that tradition is the Church’s memory; rather, it is seen as alive and as serving the Church in a dialogue that is genuine, not apparent. According to Francis, man, as an individual, unique in his own life, is at the center of everything: moral norms are auxiliary and external to him. Additionally, the pope assumes that every man is a creature of God and is therefore surrounded by God’s grace. From this perspective, Francis looks at other religions as subjects of dialogue.

2.3 The Antagonism as Resistance

The discursive and hermeneutical approaches demonstrate that cartoons express the articulation of classical intra-religious disputes. The theological arguments have already been expressed, clearly pointing to a post-polemic situation. Both sides have dug into their positions and have begun fighting for victory. Their actions go beyond the democratic division indicated at the start of the discussion into non-negotiable political and negotiable politics. Ultimately, the democratic consensus and the democratic counter, as outlined by Mouffe, are being bypassed.[45] It means that, in this particular case, extreme antagonism is revealed in a specific form. A resistance takes over, whereby a group opposes any version of the world other than its own and articulates ideas and images that negate the right for its opponents to exist and work.

In the studied cartoons, resistance leads directly to the articulation of crushing criticism toward Francis by exposing three schemas: illustrating the Pope’s bad agency in the Church; extreme ridicule of the values represented by Francis; and the contortion of the pope’s characterization as a bipolar (despot/clown) and emotionally unstable individual. When the pope is depicted as an extreme predator, his opponents are cast as victims.

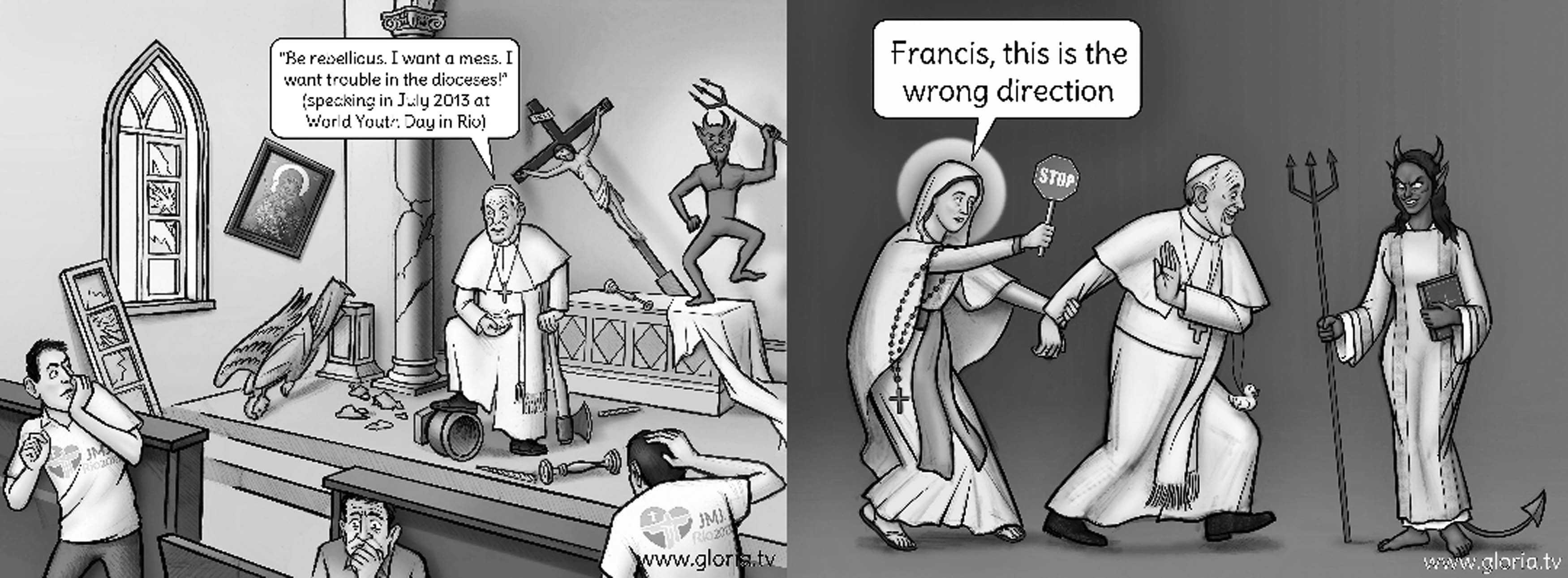

As the examples in Figure 1 show, Francis’ authority is contested by the schema of bad agency, which results from the extreme view that the current pope is now the devil’s servant. Francis is not directly identified with the figure of the antichrist as present in Christianity in any of the analyzed themes. The digital cartoons, however, illustrate the discursive mechanism of contrast that St. Peter’s successor is cooperating with the devil and places the satanic over the holy. This contrast plays out on three levels.[46]

Examples of the pope’s bad agency.

Extreme ridicule of the values that Francis represents occurs also through the discursive mechanism of contrast. Figure 2 illustrates this in relation to Francis’ promotion of inculturation and respect for sexual minorities. In the first cartoon, the element of Mother Earth is reduced to the pope and the wild packmas dancing in the spotlight. On the other side is the Holy Family leaving the circus. The contrast occurs here through an evident diminishing of religious symbolism. On the one hand, the first symbol is taken out of context and reduced to idolatry. On the other hand, the second symbol is expanded to the point of being a figure of true religion resisting false new cults.

Examples of ridiculing the values held by the pope.

The second cartoon contrasts effeminate male figures (a stand-in for LGBTQIA+ individuals) confronting a traditional extended family. The contrast used in this strategy amounts to a juxtaposition of exaggerated stereotypes that stigmatizes and ridicules minorities. On one side, there are representatives of a sexual minority who are extremely fearful and effeminate. Their adversary on the other side is a Catholic family, unrealistically full of children, organized and ready to act. These exaggerated digital cartoons depict the pope as diverting attention from traditional values in favor of minority aberrations.

Here, the criticism toward Francis is presented in the context of personality traits. Figure 3 illustrates the extreme position in which Francis reveals himself. In situations of subordination, e.g., toward politicians and representatives of other religions, the pope is shown as playing the role of a clown. The second image, on the other hand, depicts him as having a despotic and deceptive nature. It reveals criticism within the Church, expressed by a mosquito with the inscription of the Gloria.tv portal (Figure 3).

Examples illustrating the pope’s extreme behavior.

Examples illustrating the pope’s supposed mental problems.

The pope’s personality issues are also presented in an extreme way through references to his experiences with psychoanalysis (Figure 4). He is portrayed as a person who needs help (depicted lying on a therapist’s couch) or as a subject of serious medical treatment (sitting incapacitated in a straitjacket).

The last of the criticism strategies indicates that Francis is a predator who is eradicating his opponents inside of the Roman Catholic Church, specifically opponents which align themselves with traditionalist, or Tridentine, Catholicism. Figure 5 illustrates two diagrams in which this mechanism is used. In the case of ordinary believers, including priests and nuns, the pope uses physical violence to separate them from the traditional rite of the mass. In the first of the memes, the document Summorum Pontificum, an apostolic letter from Pope Benedict XVI issued in July 2007 to allow priests to celebrate the Traditional Latin Mass or Tridentine Mass, and a page showing a kneeler, a symbol of traditional devotion (specifically the pre-Vatican II tradition of receiving the Eucharist on the tongue while kneeling), are crossed out. The Latin Mass is one of the central liturgical issues in question for radical traditionalist Catholics, and Pope Francis has already begun taking concrete action to curb it. On July 16, 2021, the Congregation for the Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, with the approval of Pope Francis, published Traditionis custodes. The decree restricts where and by whom Latin Masses can be celebrated, prohibiting the celebration of the Mass and sacraments in the old rite following the liturgical books Rituale Romanum and Pontificale Romanum. This decree and its implications represent a new progression in the Catholic Church’s liturgy wars.

Examples illustrating the pope’s predatory nature.

In this first cartoon, Francis is shown to exert dictatorial control over other Church leadership through the threat of physical violence. Additionally, this theme reinforces the racism within the cartoon. Pope Benedict XVI is portrayed with his head cut off on a platter just like John the Baptist, while Cardinal Sarah has his head impaled like a slave who has tried to escape from a captor. The tools of evil action (censorship of leaflets, the slinging of clerics, and the beheading of a predecessor) reinforce the stigmatization of Francis. These point to an ongoing life-and-death struggle in which Francis assumes the role of a bad agent. Moreover, they try to prove that the Pope is an actor, ready to commit any crimes in the name of his beliefs.

3 Discussion and Conclusion

In this discursive and hermeneutic study, we have analyzed the radical traditionalist Catholic resistance articulated in digital cartoons about Pope Francis. In response to RQ1, we can state that this method of articulating intra-Catholic resistance utilizes digital cartoons to purport four arguments aiming to distort Pope Francis’ image: exposing Francis’ bad agency, ridiculing papal values, exposing Francis’ extreme behavior and imbalance, and exposing Francis’ predatory attitude toward representatives of Church tradition. Each of these arguments sparks ethical concerns about Francis occupying the seat of power in the Catholic Church. Further investigation into comments in response to these cartoons reflect more Catholics praying and hoping for his removal from the position or death.

We can see that these cartoons were created from strikingly different reasons from what de Mattei calls “filial resistance” and an “act of love towards the Church.”[47] While radical traditionalist Catholics creating these cartoons intend for them to be tools advocating for a more traditionalist Church, and to achieve this instability surrounding Pope Francis’s authority, their actions solidify an ideological war within the Catholic Church. This resonates with the typical approach to use satire as a form that provides social control by effectively attracting attention.[48] Thus, traditional Catholic resistance may be understood as a specific antagonistic clash in at least three ways. In reflecting on the possibilities of exercising democratic consensus[49] proposes operating within a continuum from social agonism to social antagonism, with the former referring to a mechanism compatible with the voice of marginalized minorities. Our study shows that such a continuum also includes the so-called “Catholic resistance,” a dogmatic religious dimension that creates a state of counterattack, by far increasing antagonism. The cartoons were created within a democratic regime, meaning in an environment of free discourse, open to consensus, and freedom of expression. Thus, we draw the conclusion that it is only because it is articulated within a democratic society that the discourse of the digital cartoons under study will not cause a religious war.

At the same time, these digital cartoons are a testimony to a strictly religious controversy, situated in the post-polemic phase of Catholic doctrinal debate. They express ideas of traditional Catholic opponents through exaggerated contrast by using allusions to Pope Francis, his comrades, and the entire Vatican II Council. This characteristic diffusion of heterodoxy and exposition of anti-values should be seen as a result of the blockades within the Church itself. Pope Francis exposed his obligations toward the Second Vatican Council when taking into account the Church’s current approach. Quoting Pope Francis himself will help us to better understand this:

This is Magisterium: the Council is the Magisterium of the Church. Either you are with the Church and therefore you follow the Council, and if you do not follow the Council or you interpret it in your own way, as you wish, you are not with the Church.[50]

Thus, the context of the production of the analyzed cartoons is significantly organized in opposition to the pope’s directives and his agency toward limiting access to the Latin mass. Such limitations, typically including different social limits[51] encourage the papal counter-publics.

Contrary to studies pointing to Francis’ positive achievements,[52] no success appears in the discourse of digital cartoons in the present study sample. This indicates that Gloria.tv is interested in the conflict. From a certain perspective, this corresponds with actions on the way to the abolition of religious controversies.[53] Criticizing the pope is supposed to be an intervention persuading him and his followers to change their bad agency. The problem here is that the bad agency mechanism attributed to Francis has already appeared in the discourse on the pope on the web[54] and shows a character analogous to classical studies on depreciation.[55] Bad agency, therefore, overshadows a call to change. Consequently, this has nothing in common with other actions such as, for example, “Cardinals’ doubts,” which were a manifestation calling for the pope to clarify his teaching.[56]

Yet, the exposition regarding the pope’s predatory attitude toward the followers of the traditional Church establishment introduces a new direction of resistance, where strategic offense-giving is essentially associated with digital practices playing on gender and sexual identity. This goes along the lines of hypermediation, which, in the area of religion and digital space, is particularly evident in “anti-gender movements: Christian- inspired groups that oppose same-sex unions and promote traditional family values.”[57] The issue, however, is the extent of the intervention by the content creators. They intensify satirical practices in the present papal situation by using this digital cartoon genre. However, they also omit the typical anti-gender movement’s translation of old Catholic ideology into protests that overturn the status quo.[58] Thus, their Catholic resistance is hypermediated in a limited way. The essence of satirical cartoons is not in determining who is right – this activity has long ceased. At this stage, the dispute relates to articulating another heteronomous position toward the pope. Controversies and contrasts are also tools for achieving the indicated goal, as the traditionalist group is convinced that it possesses the absolute truth. Such a case turns out to be another type of “cultic milieu.”[59] When comparing this with Campbell’s original concept, on the one hand, they represent a cultural underground where counter-papacy views can prosper. On the other, they are not Campbell’s “seekers” of new cults and mysticism. On the contrary, they are renovators of the Church’s old and original approach. What makes them unique, though, is their ability to operate in the digital world and digital culture. They utilize digital innovations and at the same time refuse to support the internal modernization of their Church. This shows their ability to remain opposing watchdogs[60] with disruptive digital criticism skills. Yet, it also shows that they are creating a new kind of digital milieu. It is highly antagonistic but, compared to other radical spaces on the internet, it excludes physical violence.[61]

Ultimately, when exploring Catholic resistance through digital cartoons, we see that it has much in common with the previous approaches to contesting religious authority through satirical content. The novelty here is that, thrown into the digital environment, the papacy is challenged within a liminal space containing layers of antagonistic counter-public, hypermediation without sources to public actions, and the digital milieu that is based on modernity in technology but excludes it in religious ideas.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their formative suggestions and comments.

-

Funding information: This article is written as an outcome of the project “Papal Authority Transformed by Changes in Communication” funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (no. 2019/35/B/HS2/00016) under the scheme Opus 18.

-

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

-

Data availability statement: The data from the research are available at https://doi.org/10.18150/SIKTKG.

References

Ashfaq, Ayesha and Adnan Bin Hussein. “Political Cartoonists Versus Readers: Role of Political Cartoonists in Building Public Opinion and Readers’ Expectations Towards Print Media Cartoons in Pakistan.” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4, no. 3 (2013), 265–72.10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n3p265Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Sherry and Joel Campbell. “Mitt Romney’s Religion: A Five Factor Model for Analysis of Media Representation of Mormon Identity.” Journal of Media and Religion 9, no. 2 (2010), 99–121. 10.1080/15348421003738801.Search in Google Scholar

Bellar, Wendi, Heidi A. Campbell, Kyong James Cho, Andrea Terry, Ruth Tsuria, Aya Yadlin-Segal, and Jordan Ziemer. “Reading Religion in Internet Memes.” Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 2, no. 2 (2013), 1–39. 10.1163/21659214-90000031.Search in Google Scholar

Benoit, William L. and Kevin A. Stein. “Kategoria of Cartoons on the Catholic Church Sexual Abuse Scandal.” In The Rhetoric of Pope John Paul II, edited by Joseph R. Blaney and Joseph P. Zompetti, 23–35. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

Betten, Francis S. “The Cartoon in Luther’s Warfare against the Church.” The Catholic Historical Review 11, no. 2 (1925), 252–64.Search in Google Scholar

Borer, Michael Ian and Adam Murphree. “Framing Catholicism: Jack Chick’s Anti-Catholic Cartoons and the Flexible Boundaries of the Culture Wars.” Religion and American Culture 18, no. 1 (2008), 95–112. 10.1525/rac.2008.18.1.95.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Collin. “The Cult, The Cultic Milieu and Secularization.” Sociological Yearbook of Religion in Britain, no. 5 (1972), 119–36.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Heidi A. “Religious Authority and the Blogosphere.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 15, no. 2 (2010), 251–76. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2010.01519.x.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Heidi A. “Religious Communication and Technology.” Annals of the International Communication Association 41, no. 3–4 (2017), 228–34. 10.1080/23808985.2017.1374200.Search in Google Scholar

Carpentier, Nico. The Discursive-Material Knot: Cyprus in Conflict and Community Media Participation. New York: Pater Lang, 2017.10.3726/978-1-4331-3754-9Search in Google Scholar

Carpentier, Nico, Benjamin De Cleen, and Leen Van Brussel. “Introduction.” In Communication and Discourse Theory: Selected Works of the Brussels Discourse Theory Group, edited by Leen Van Brussel, Nico Carpentier, and Benjamin De Cleen, 3–31. Bristol, Chicago: Intelect, 2019.10.2307/j.ctv36xvhx4.3Search in Google Scholar

Cloutier, David. “Pope Francis and American Economics.” Horizons 42, no. 1 (June 2015), 122–28. 10.1017/hor.2015.47.Search in Google Scholar

DeSousa, Michael A. and Martin J. Medhurst. “The Editorial Cartoon as Visual Rhetoric: Rethinking Boss Tweed.” Journal of Visual Verbal Languaging 2, no. 2 (1982), 43–52.10.1080/23796529.1982.11674355Search in Google Scholar

Van Dijk, Teun A. Racism and the Press. London: Routledge, 1991.Search in Google Scholar

Evolvi, Giulia. Blogging My Religion: Secular, Muslim, and Catholic Media Spaces in Europe. London and New York: Routledge, 2019.10.4324/9780203710067Search in Google Scholar

Evolvi, Giulia. “Religion and the Internet: Digital Religion, (hyper)mediated Spaces, and Materiality.” Zeitschrift Für Religion, Gesellschaft Und Politik 6, no. 1 (2022), 9–25. 10.1007/s41682-021-00087-9.Search in Google Scholar

Evolvi, Giulia. “The Theory of Hypermediation: Anti-Gender Christian Groups and Digital Religion.” Journal of Media and Religion 21, no. 2 (2022), 69–88. 10.1080/15348423.2022.2059302.Search in Google Scholar

Filimonov, Kirill and Jakob Svensson. “(re)Articulating Feminism: A Discourse Analysis of Sweden’s Feminist Initiative Election Campaign.” Nordicom Review 37 (2016), 1–16. 10.1515/nor-2016-0017.Search in Google Scholar

Flamini, Roland. “Pope Francis: Resurrecting Catholicism’s Image?” World Affairs; Washington 176, no. 3 (October 2013), 25–33.Search in Google Scholar

Floridi, Luciano. “Is Semantic Information Meaningful Data?” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 70, no. 2 (2007), 351–70. 10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x.Search in Google Scholar

Francis. “Address to Participants in the Meeting Promoted by the National Catechetical Office of the Italian Episcopal Conference,” January 30, 2021. https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2021/january/documents/papa-francesco_20210130_ufficio-catechistico-cei.html.Search in Google Scholar

Gallagher, John A. “Pope Francis’ Potential Impact on American Bioethics.” Christian Bioethics: Non-Ecumenical Studies in Medical Morality 21, no. 1 (April 1, 2015), 11–34. 10.1093/cb/cbu048.Search in Google Scholar

Garbagnoli, Sara. “«L’ideologia Del Genere»: L’irresistibile Ascesa Di Un’invenzione Retorica Vaticana Contro La Denaturalizzazione Dell’ordine Sessuale [‘The Ideology of Gender’: The Irresistible Rise of a Vatican Rhetorical Invention against the Denaturalization of the Sexual Order].” AG About Gender - International Journal of Gender Studies 3, no. 6 (2014), 250–63. 10.15167/2279-5057/ag.2014.3.6.224.Search in Google Scholar

Gerbaudo, Paolo. “From Data Analytics to Data Hermeneutics. Online Political Discussions, Digital Methods and the Continuing Relevance of Interpretive Approaches.” Digital Culture & Society 2, no. 2 (2016), 95–111. 10.25969/mediarep/1012.Search in Google Scholar

Guzek, Damian. “Discovering the Digital Authority: Twitter as Reporting Tool for Papal Activities.” Online – Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 9 (2015), 63–80.Search in Google Scholar

Guzek, Damian. “Religious Memory on Facebook in Times of Refugee Crisis.” Social Compass 66, no. 1 (2019), 75–93. 10.1177/0037768618815782.Search in Google Scholar

Halloran, Fiona Deans. Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons. 1st ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.10.5149/9780807837351_halloran.4Search in Google Scholar

Hjarvard, Stig. “The Mediatization of Religion: A Theory of the Media as Agents of Religious Change.” Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook 6, no. 1 (2008), 9–26. 10.1386/nl.6.1.9_1.Search in Google Scholar

Hjarvard, Stig. “Three Forms of Mediatized Religion. Changing the Public Face of Religion.” In Mediatization and Religion Nordic Perspectives, edited by Stig Hjarvard and Mia Lövheim, 21–44. Göteborg: NORDICOM, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Hofmann, Werner. Caricature: From Leonardo to Picasso. New York: Crown Publishers, 1957.10.2307/773676Search in Google Scholar

Horsfield, Peter. “The Ethics of Virtual Reality: The Digital and its Predecessors.” Media Development 50, no. 2 (2003), 48–59.Search in Google Scholar

Hussain, Ali J. “The Media’s Role in a Clash of Misconceptions: The Case of the Danish Muhammad Cartoons.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 12, no. 4 (2007), 112–30. 10.1177/1081180X07307190.Search in Google Scholar

Justice, Benjamin. “Thomas Nast and the Public School of the 1870s.” History of Education Quarterly 45, no. 2 (2005), 171–206. 10.1111/j.1748-5959.2005.tb00034.x.Search in Google Scholar

Kaplan, Jeffrey S. and Heléne Lööw, eds. The Cultic Milieu: Oppositional Subcultures in an Age of Globalization. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2002. https://rowman.com/ISBN/9780759102040/The-Cultic-Milieu-Oppositional-Subcultures-in-an-Age-of-Globalization.Search in Google Scholar

Kenny, Kevin. The American Irish: A History. London and New York: Routledge, 2014.10.4324/9781315842530Search in Google Scholar

Klausen, Jytte. The Cartoons That Shook the World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

Kornat, Marek. “Perspektywa Straszliwa I Niewyobrażalna. Prof. Marek Kornat O “synodalności‘ [A Frightening and Unimaginable Prospect. Prof. Marek Kornat on’Synodality”].” PCH24.pl, October 13, 2021. https://pch24.pl/perspektywa-straszliwa-i-niewyobrazalna-prof-marek-kornat-o-synodalnosci/.Search in Google Scholar

Laclau, Ernesto. “Metaphor and Social Antagonisms.” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 249–57. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.Search in Google Scholar

Laclau, Ernesto and Chantal Mouffe. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London; New York: Verso, 1985.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Benjamin and Kim Knott. “More Grist to the Mill? Reciprocal Radicalisation and Reactions to Terrorism in the Far-Right Digital Milieu.” Perspectives on Terrorism 14, no. 3 (2020), 98–115. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26918303.10.1080/19434472.2020.1850842Search in Google Scholar

Lefebvre, Marcel. I Accuse the Council. 2nd ed. Kansas: Angelus Press, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

Lundmark, Evelina and Stephen LeDrew. “Unorganized Atheism and the Secular Movement: Reddit as a Site for Studying ‘lived Atheism.’” Social Compass 66, no. 1 (2019), 112–29. 10.1177/0037768618816096.Search in Google Scholar

Mallia, Karen L. “From the Sacred to the Profane: A Critical Analysis of the Changing Nature of Religious Imagery in Advertising.” Journal of Media and Religion 8, no. 3 (2009), 172–90. 10.1080/15348420903091162.Search in Google Scholar

de Mattei, Roberto. Love for the Papacy and Filial Resistance to the Pope in the History of the Church. Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

McNees, Eleanor. “‘Punch’ and the Pope: Three Decades of Anti-Catholic Caricature.” Victorian Periodicals Review 37, no. 1 (2004), 18–45.Search in Google Scholar

Mouffe, Chantal. Agonistics: Thinking The World Politically. London, New York: Verso, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

O’Collins, Gerald. Catholicism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.10.1093/actrade/9780199545919.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Payne, Robert. “‘Je Suis Charlie’: Viral Circulation and the Ambivalence of Affective Citizenship.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 21, no. 3 (2018), 277–92. 10.1177/1367877916675193.Search in Google Scholar

Pettegree, Andrew. Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe – and Started the Protestant Reformation. New York: Penguin Press, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

Romele, Alberto, Marta Severo, and Paolo Furia. “Digital Hermeneutics: From Interpreting with Machines to Interpretational Machines.” AI & Society 35, no. 1 (2020), 73–86. 10.1007/s00146-018-0856-2.Search in Google Scholar

Ricoeur, Paul. “Existence and Hermeneutics.” In The Conflict of Interpretations: Essays in Hermeneutics, edited by Paul Ricoeur, 3–26. London: Continuum, 2004.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Siegfried J. (2010). “Literary Studies from Hermeneutics to Media Culture Studies.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 12, no. 1 (2010), 2–10. 10.7771/1481-4374.1569.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Carl. The Concept of the Political, edited by Tracy B. Strong and Leo Strauss, translated by George Schwab. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Shikes, Ralph E. The Indignant Eye: The Artist as Social Critic in Prints and Drawings from the Fifteenth Century to Picasso. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969.Search in Google Scholar

Smudde, Peter. “Pope Francis and the ‘Dubia Cardinals’: An Examination of the Roles of High- and Low-Context Cultures in the Case of Amoris Laetitia.” Journal of Communication & Religion 42, no. 3 (2019), 24–38.Search in Google Scholar

Stępniak, Krzysztof. “Advertising in Communication of the Catholic Church. The Case of Poland.” Central European Journal of Communication 13, no. 27 (2020), 409–25.10.51480/1899-5101.13.3(27).6Search in Google Scholar

Sturges, Paul. “Limits to Freedom of Expression? Considerations Arising from the Danish Cartoons Affair.” IFLA Journal 32, no. 3 (2006), 181–88. 10.1177/0340035206070164.Search in Google Scholar

Sumiala, Johanna. “‘Je Suis Charlie’ and the Digital Mediascape: The Politics of Death in the Charlie Hebdo Mourning Rituals.” Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 11, no. 1 (2017), 111–26. 10.1515/jef-2017-0007.Search in Google Scholar

Sumiala, Johanna, Katja Valaskavi, Minttu Tikka, and Jukka Huhtamäki, eds. Hybrid Media Events: The Charlie Hebdo Attacks and the Global Circulation of Terrorist Violence. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2018.10.1108/9781787148512Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, Valerie A., Diane Halstead, and Paula J. Haynes. “Consumer Responses to Christian Religious Symbols in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 39, no. 2 (2010), 79–92. 10.2753/JOA0091-3367390206.Search in Google Scholar

Torfing, Jacob. New Theories of Discourse: Laclau, Mouffe and Zizek. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

Tsuria, Ruth. “The Space between Us: Considering Online Media for Interreligious Dialogue.” Religion 50, no. 3 (2020), 437–54. 10.1080/0048721X.2020.1754598.Search in Google Scholar

Vatican Council. “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in The Modern World Gaudium et Spes.” Libreria Editrice Vaticana, December 7, 1965. https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, S.-F. (2008). “A Hermeneutic Approach to the Notion of Information in IS.” In Knowledge-Based Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems: 12th International Conference, KES 2008, Zagreb, Croatia, September 3–5, 2008, Proceedings, Part II, edited by I. Lovrek, R. J. Howlett, and L. C. Jain, 340–45. Springer.10.1007/978-3-540-85565-1_43Search in Google Scholar

Wernet, Andreas. “Hermeneutics and Objective Hermeneutics.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by Uwe Flick, 235–46. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2014. 10.4135/9781446282243.n16.Search in Google Scholar

Wimmer, Andreas and Thomas Soehl. “Blocked Acculturation: Cultural Heterodoxy among Europe’s Immigrants.” American Journal of Sociology 120, no. 1 (2014), 146–86. 10.1086/677207.Search in Google Scholar

Woźnica, Anna and Jan Słomka. “Radical Nature of Pope Francis’s Ecclesiology.” Teologia W Polsce, no. 1 (2021), 107–22. 10.31743/twp.2021.15.1.04.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Topical issue: Political Theology and the State of Exception: Critical Readings on the Centenary of “Political Theology” and “Roman Catholicism and Political Form” by Carl Schmitt, edited by Guillermo Andrés Duque Silva

- With Schmitt, Against Schmitt, and Beyond Schmitt: Exception and Sovereign Decision to 100 Years of Political Theology I and Roman Catholicism and Political Form

- Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology of Revolution

- The Metaphysical Contention of Political Theology

- Secularism as Theopolitics: Jalāl ud-Dīn Akbar and the Theological Underpinnings of the State in South Asia

- Apophatic Confrontation: von Balthasar’s Thought on Kenosis and Community as a Veiled Response to the “Trend” of Political Theology

- Weak Decisionism and Political Polytheology: The Neutralization of Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology by Hans Blumenberg and the Ritter School

- Topical issue: Religion and Spirituality in Everyday Life, edited by Joana Bahia, Cecilia Bastos, and María Pilar García Bossio

- If You Have Faith, Exu Responds on-line: The Day-to-Day Life of Quimbanda on Social Networks

- Media and the Sacralization of Leaders and Events: The Construction of a Religious Public Sphere

- Exploring Twenty-First-Century Catholic Traditionalist Resistance Movement through Digital Cartoons of Pope Francis

- Contemporary Filiality and Popular Religion: An Ethnographic Study of Filiality Among Chinese University Students and their Parents

- Ritual Sweat Bath in a Cross-Cultural Perspective

- Regular Articles

- Naturalism Fails an Empirical Test: Darwin’s “Dangerous” Idea in Retrospect

- Talking about God from the Meaning of Life: Contributions from the Thought of Juan Antonio Estrada

- Symbolic Theology and Resistance in the Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Paul Tillich

- Developing a Methodology for Hymnal Revision within a Contemporary, Multi-Ethnic Framework: A Proposal

- Development and Validation of Secularity Scale for Muslims

- God Does Not Work in Us Without Us: On the Understanding of Divine–Human Cooperation in the Thought of Martin Luther

Articles in the same Issue

- Topical issue: Political Theology and the State of Exception: Critical Readings on the Centenary of “Political Theology” and “Roman Catholicism and Political Form” by Carl Schmitt, edited by Guillermo Andrés Duque Silva

- With Schmitt, Against Schmitt, and Beyond Schmitt: Exception and Sovereign Decision to 100 Years of Political Theology I and Roman Catholicism and Political Form

- Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology of Revolution

- The Metaphysical Contention of Political Theology

- Secularism as Theopolitics: Jalāl ud-Dīn Akbar and the Theological Underpinnings of the State in South Asia

- Apophatic Confrontation: von Balthasar’s Thought on Kenosis and Community as a Veiled Response to the “Trend” of Political Theology

- Weak Decisionism and Political Polytheology: The Neutralization of Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology by Hans Blumenberg and the Ritter School

- Topical issue: Religion and Spirituality in Everyday Life, edited by Joana Bahia, Cecilia Bastos, and María Pilar García Bossio

- If You Have Faith, Exu Responds on-line: The Day-to-Day Life of Quimbanda on Social Networks

- Media and the Sacralization of Leaders and Events: The Construction of a Religious Public Sphere

- Exploring Twenty-First-Century Catholic Traditionalist Resistance Movement through Digital Cartoons of Pope Francis

- Contemporary Filiality and Popular Religion: An Ethnographic Study of Filiality Among Chinese University Students and their Parents

- Ritual Sweat Bath in a Cross-Cultural Perspective

- Regular Articles

- Naturalism Fails an Empirical Test: Darwin’s “Dangerous” Idea in Retrospect

- Talking about God from the Meaning of Life: Contributions from the Thought of Juan Antonio Estrada

- Symbolic Theology and Resistance in the Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Paul Tillich

- Developing a Methodology for Hymnal Revision within a Contemporary, Multi-Ethnic Framework: A Proposal

- Development and Validation of Secularity Scale for Muslims

- God Does Not Work in Us Without Us: On the Understanding of Divine–Human Cooperation in the Thought of Martin Luther