Abstract

Purpose

This article aims to problematize influencers’ emotional ecologies regarding their digital work as content generators and the emotional ecologies recorded in the food practices they share on their profiles.

Design/methodology/approach

Semi-structured digital interviews and a digital ethnography process in the feeds of the influencers who responded to the interview.

Findings

We find some similarities in the emotional ecologies we analyze. The influencers’ posts reference emotional ecologies such as love for sharing content, eating with others, and cooking, and tiredness referred to planning the meal, cooking, and liking/enjoying concerning eating with others and sharing content. While in the interviews, it has been possible to elucidate the emergence of the logic of pleasure and happiness about showing/reflecting, sharing content, and inspiring and transmitting something to the other, and satisfaction combined with indifference or tiredness, in some cases, concerning the work itself as influencers.

Practical implications

Analyzing digital consumption and the influencer phenomenon today provides us with tools to think about the current and future society. In the context of technological advances and digitalization processes, it is necessary to open the dialogue to discuss digital labor changes, new workspaces, workers’ relationships with companies/brands/corporations, and the involvement of bodies and emotions there.

Social implications

It problematizes the effects of digital consumption, food digital practices, and influencers’s work in everyday social practices.

Originality/value

This article addresses the criteria that organize the structuration regime of sensibilities on Instagram regarding food practices and the generation of content based on the figures of Argentinian food influencers.

1 Introduction

Historically, social theory has attempted to unravel the social structuration process (Giddens 1984). Thus, today, it is imperative to address the practices of the digitalized world and the current emotionalization processes as they shape the new social reality. Although the dimensions that express the 4.0 revolution at a global level are multiple, on this occasion, we start by considering the importance of addressing the social structuration process from food.

Eating is a complex phenomenon combining biological and social elements, understood as the processes of definition, transmission, and sharing of food, as well as incorporating nutrients and senses (Fischler 1995). In this sense, in addition to genetic and biological variables, there are sociocultural variables such as social class, age, gender, identity, or ethnic group that influence and determine our daily food choices and preferences (Contreras and Gracia-Arnáiz 2005). This is how this practice becomes a key piece in addressing forms of social structuration.

In this writing, we will focus on the content and information about food established on digital platforms such as Instagram, from the figure of the food influencer and the implication of bodies/emotions in that space. An influencer is a person who has become popular on social networks, specifically on Instagram, by producing information on a particular topic and making a profit from that work. According to a statistical report by Statista (2023), influencer marketing has become one of the most popular and effective forms of online marketing. The value of the global influencer marketing market stood at US$21.1 billion in 2023, having more than tripled since 2019 (Statista 2023).

Because of the rise of influencers and their expansion in recent years, and considering the impact that applications and social networks have on sensations, emotions, and sensibilities (Scribano 2023), this work is part of a master’s thesis in Social Sciences Research, which develops a journey that addresses the criteria that organize the structuring regime of sensibilities around food practices and the generation of content on Instagram, during the period 2020–2022, in Argentina. To achieve this objective, a qualitative approach methodology based on a digital ethnography process on Instagram was used, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with food influencers on the platform.

This article proposes to problematize the emotions that emerge from the interviews and the digital ethnography process on the Instagram profiles of 25 food influencers from Argentina.

Also, the aim is to tension emotional ecologies regarding food practices influencers share on their profiles (product of ethnography) and emotional ecologies regarding the digital work they do as content generators (product of interviews).

Emotional ecology is understood as a set of emotions perceived in specific contexts, which are connected in some way and can only be understood concerning each other. These emotions structure everyday social relations as the experience cannot be expressed in an absolute way with a single practice of feeling (Scribano 2020a).

2 Transmission of digital food knowledge: the case of influencers

As we mentioned in the introduction, the planet is currently adopting a new production paradigm, characterized by a process of digital transformation and technological progress, which some authors call revolution 4.0 (Fuchs 2014; Fussey and Roth 2020; Nagao Menezes 2020; Scribano and Lisdero 2019). There are multiple effects resulting from the technological changes that have occurred: new social practices and work modalities (Fumagalli et al. 2019; Scribano and Lisdero 2019), changes in the ways of feeling and knowing the world (Scribano 2023), new forms of social interaction and relationship with the environment (Alakeson et al. 2003), among others. For our research purposes, we will point out here how eating as a social phenomenon and the management of information about food have been changing, focusing on the changes resulting from access to new technologies and the current process of digitalization of life.

One aspect of the changes in eating and what is eaten is the variation in the transmission of food knowledge. The latter involves the requirements to carry out the practices of provisioning, conservation, cooking, recycling, food control, and physical care of the body, among others. Historically, This knowledge has been transmitted orally and domestically through cookbooks, magazines, and television programs.

In Argentina, in the last century, the phenomenon of Petrona Carrizo de Gandulfo, better known as “Doña Petrona”, stands out. She was a cooking teacher and a pioneering television cook in Argentina. Petrona Carrizo de Gandulfo (1898–1992) became known for her radio appearances, the written press, and subsequent television dissemination (Caldo 2016). Her famous book “El libro de Doña Petrona C. de Gandulfo” was first published in 1934 and continued to be republished even after her death. It is considered one of the best-selling books in Argentina, along with the Bible. In this regard, Pite (2016) wrote a book entitled “La mesa está servida. Doña Petrona C. de Gandulfo y la domesticidad en la Argentina del siglo XX”, in which she highlights the value of Doña Petrona’s productions in making it possible to “shed light on the omnipresent (and little studied) domestic roles that women have played as a consequence of the sexual division of labor throughout the 20th century” (Pite 2016:16). In line with Pite, Doña Petrona’s work: the instructions, assessments and classifications that are woven there, become critical pieces to understand the society of the time, from the daily eating practices and the transmission of knowledge of protocol and ceremony, manners, and culinary knowledge.

In addition to cookbooks, cooking magazines and television programs have proliferated in our country as channels for transmitting information about food and cooking. Among the recognized television programs, the following stand out: “Buenas tardes, mucho gusto”, hosted by Petrona Carrizo de Gandulfo, starting in the 1950s; the “Utilisima” series; “Gato DumasCocinero”; “Cocineros Argentinos”, which is very popular; Canal elgourmet; among others. On another occasion, it is worth going over the changes in how recipes are presented. These spaces are shown, and different foods and cultures are presented, among other modifications that cooking magazines and television formats have undergone as time goes by.

However, domestic food practices are mostly daily, time-consuming, and are carried out by women (Aguirre et al. 2015; Charles and Kerr 1986; Gracia Arnaiz 1996; Mennell et al. 1992). Several authors have problematized this responsibility, which is usually part of a set of domestic activities that fall on women, within the framework of what has been conceptualized as reproductive work. Along these lines and returning to the axis of distribution of knowledge and information, Gracia-Arnaiz (1996) argues that food knowledge has generally been transmitted by women, despite their massive incorporation into the labor market and the introduction of services outside the domestic sphere.

Today, it is essential to highlight the importance of thinking about the changes in the transmission of this food knowledge based on the technological transformations resulting from the democratization of the use of mobile devices and the massiveness of digital applications. In this line, Deborah Lupton (2021) argues that media coverage of food that previously depended on a limited number of professionals: cookbooks and television cooking shows by renowned chefs, restaurant critics and food writers, since the beginning of the 21st century has involved new media formats such as blogs, social networking sites, the use of hashtags and influencers that have transformed the creation of content and its subsequent sharing.

Currently, digital consumption, the proliferation of information about food on social networks, and the popularity of influencers who produce senses and meanings about food and culinary practices have modified daily food practices, thus establishing a politics of sensibilities regarding food in general, food choices and the organization of life (Mairano 2024). Regarding these practices, Borkenhagen (2017) exposes the emergence of open-source cuisine as a phenomenon in which chefs share their knowledge in public spaces such as personal blogs, online culinary forums and social media platforms, which implies a change in the sharing customs of the culinary industry. There are also other debates on the subject, to mention a few; we point out the contributions to the transmission of culinary secrets (Lee and Tao 2021), culinary criticism on Instagram (Feldman 2021), recipe sharing on blogs (Lofgren 2013), anorexia and food pornography in cyberspace (Lavis 2017), influence of social networks on the development of overweight and obesity (Powell et al. 2015), veganism and gender in blogs (Hart 2018), weight and body shapes in digital media (Lupton 2017), everyday culinary practices (Kirkwood 2018), among others.

Now, addressing changes in the format of information dissemination becomes necessary since when we innovate technological resources, “not only the content and the form are modified but also the explanatory and demonstrative level of the didactic performance” (Caldo 2016: 319). Likewise, as Schneider and Eli (2021) argue in their work “Fieldwork in online foodscapes: How to bring an ethnographic approach to studies of digital food and digital eating”, the digitalization of food and eating as a multidirectional and interactive process, not only shapes food and eating, but also constructs the meaning given to the digital.

It should be noted that our interest in problematizing the emotions woven into food content, along with the emotions of influencers when carrying out their work as such, results from the impact that applications and social networks have on sensations, emotions and sensibilities (Scribano 2023). In the context of emotionalization of life, the massiveness of images distributed in digital media directly influences the perceptions of those who consume the content and online interaction (Abell and Biswas 2023; Deighton-Smith and Bell 2018). Specifically concerning food choices, digital media highlight moralities and evaluations about food by addressing consumers (MacGregor et al. 2021).

That said, we will focus on one of the central figures of current digital media: “the influencer”, which implies a person who has become popular on social medi, by generating content and information on a particular topic, and who makes a profit from that work, in a context in which influencer marketing is increasingly used as a strategic tool by marketing specialists in various industries (Abell and Biswas 2023). Likewise, they are considered a reference to be a reliable trend creator in one or more niches (De Veirman et al. 2017)

Influencers can be established celebrities who continue to build their brands using social media. However, they can also be unknown people, known as “micro-celebrities”, who establish their public profiles using social media (Lupton 2020). Therefore, there are different types of influencers depending on the number of followers, the geocultural context where they are inserted, their reach, their specificities of working with brands, the management of their personal brand, among others.

Below is a brief overview of some works that address the emergence of influencers in digital media and their relationship with the transmission of knowledge.

First, we highlight some studies on the reach of Instagrammers in Ecuador and influencers from Peru and Colombia, by Gonzalez-Carrion and Aguaded (2019) respectively. The first work seeks to identify which are the most influential Instagrammers in Ecuador, and analyze their profiles based on a content analysis, language analysis and the interaction generated from their profiles, based on qualitative and quantitative mixed methodologies. They used techniques such as non-participant observation, the Alianzo Ranking tool and interviews with experts. The second study aims to evaluate the forms of interaction among the main Instagrammers of Peru and Colombia, based on the Heepsy tools to establish the influencers with the most significant influence within the platform and through the Fan Page Karma and Social Blade monitoring tools to know their interaction. Next, regarding specific content influencers, Gomes Coelho and Cipiniuk (2019) present a work that aims to describe and analyze the phenomenon of digital influencers who promote products for the fashion market based on ethnographic methodologies on Instagram, which involves the content analysis of specific influencer profiles.

Similarly, Jerrentrup (2023) addresses how older fashion influencers appropriate the Instagram medium and how they build a positive identity in a network that focuses on youth and external aspects. The author concludes that older influencers can benefit their recipients and society as a whole, as they can push the fashion industry to be more inclusive and move away from the typical ideal of beauty. Likewise, Sanchez de Bustamante and Justo Von Lurzer (2021) address how the meanings and assessments of the “entrepreneurial mother” are constructed as influencers of motherhood in digital media, and Hijos (2018) addresses the participation of women in running and the representations built around it based on an analysis of advertisements, images and videos of brands and influencers on social networks. For his part, Saez (2022) analyzes the phenomenon of Booktubers, bookstagrammers and booktokers in Argentina, which relate to literary circulation and book recommendations on social media, based on the reconstruction of the trajectory of 5 influencers. Martynowskyj and Ferreiro (2021) address the discourses on sexuality reproduced from Argentine sexologists’ Instagram accounts as referents in sexology and Instagrammers of sexual education, based on a digital ethnography on the platform.

In the political sphere, Fernández Gómez et al. (2018) researched Twitter using the content analysis technique on 790 messages from ten Spanish influencers with a high impact on the platform. There, they set out to find out how influencers use Twitter to spread a particular political ideology in their messages while cultivating their brand and seeking to continue increasing their notoriety and number of followers. Moreover, focusing on the logic of food, we must mention the study by Lee and Tao (2021), who investigated the modes of transmission of culinary knowledge and secrets of a group of pastry chefs on Instagram based on a mixed methodology that consisted of visual analysis of publications and interviews with elite pastry chefs over two years; and the contribution of MacGregor et al. (2021) in their article “Promoting a healthier, younger you: The media marketing of anti-ageing superfoods”, where they propose to consider the pedagogical role played by various media, including news, advertising and infotainment, regarding dietary advice in contemporary society. From their research, the authors were able to observe that digital media became a medium through which knowledge helped instruct consumers to manage their lives (MacGregor et al. 2021). Also noteworthy are the contributions of Navarro-Beltrá and Herrero Ruiz (2020), on the success of gastronomic influencers through engagement and the study on discursive practices of food influencers by Luque García (2020). For his part,

From a marketing logic, for some authors, influencers imply an updated version of the traditional opinion leader. In these terms, Dinh et al. (2023) argue that influencers as opinion leaders have the desirable characteristics that companies look for and are ideal for e-commerce: they influence the behaviour of audiences and have the potential to persuade people to buy while maintaining a specific commitment. In a similar line of inquiry, De Veirman et al. (2017) present an analysis of two experimental studies of influencers on Instagram that address the particularities that make the leadership of an influencer on a brand, focusing on the impact they generate on the audience and the true influence. There, they highlight two dimensions that make up the popularity and the potential and influence of these people: the number of followers they have and the number of people they also follow. On the other hand, the contribution of Fernández Gómez et al. (2018) describes how the influencer emerges as a marketing tool by combining their work as a prescriber with the management of their brand. In a similar line of inquiry, Abell and Biswas (2023) examine how publishing food-related content on social media sites (Facebook and Instagram) can influence digital participation and the likelihood of trying a recommended product. Based on the research carried out, the authors were able to observe that images of people next to healthy foods increase people’s interaction and identification with the influencer, as well as the likelihood that they will try a suggested product.

Similarly, Jimenez-Castillo and Sanchez-Fernandez (2019) carried out a quantitative study with a sample of 280 followers of active influencers in Spain to evaluate the effectiveness of influencer marketing. The study’s results show that influencers’ perceived influence power not only helps generate interaction but also increases the expected value and purchase intention concerning the recommended brands. On the other hand, in conclusion, it is worth noting the contributions of Hudders and De Jans (2022) regarding the place of gender in influencer culture. The authors argue that today, many online influencers are women. Their research entitled “Gender effects in influencer marketing: an experimental study on the efficacy of endorsements by same-versus other-gender social media influencers on Instagram” aimed to examine how the influencer’s gender affects the persuasiveness of the content published by the influencer. From this, they observed a more effective same-gender endorsement for the women who participated in the study due to a more incredible feeling of similarity and more significant interaction compared to the male influencer.

As can be seen, the studies presented here coincide in the purposes of analyzing the influence of these celebrities or influencers, the representation, and meanings they give to a particular topic; others carry out case studies of specific influencers; they also address the engagement they produce from a more marketing perspective. However, these do not aim to account for the perceptions and emotions of influencers regarding their work nor to delve into the sensibilities woven from the content they publish. Thus, this work aims to approach these emotions that emerge from the content they publish and their own emotions when generating content by understanding that addressing the emotional dimension constitutes a vehicle toward a better understanding of reality and modifications at the work level.

3 Methodological strategy

As mentioned above, this article is part of a master’s thesis in Social Science Research. Twenty-five semi-structured, virtual, and self-managed interviews were conducted with food influencers, and a digital ethnography was conducted on the Instagram feeds of those influencers who responded to the interview. The interviews allowed us to get in touch with their narratives, investigate the forms, activities, marketing, and content they share, and get to know the emotions associated with their work on the social network. The digital ethnography, which consisted of observing and recording influencers’ profiles, allowed us to identify the different practices and content presented around food.

This article takes a unique approach to problematizing influencers’ emotional ecologies within this framework. It focuses on the emotional aspects of their digital work as content generators and the emotional ecologies recorded in the food practices that influencers share on their profiles. The first aspect is explored through semi-structured digital interviews while the second is revealed through the digital ethnography process in the feeds of the influencers who responded to the interview.

4 Emotions ecologies on Instagram

Emotions are a fundamental part of analyzing social reality, since as practices that guide action and cognition (Hochschild 1990; Scribano 2012), they explain social behavior (Bericat 2016). They are constituted by an interplay between individual agency, biology, biography, and society (Luna Zamora 2005) guiding and involving the person in their social environment (Illouz 2009). Accounting for emotion means understanding the situation and social relationship that produces it (Kemper 1978), given that most emotions derive from real, anticipated, imagined, or remembered results of relational interaction (Bericat 2016). This is how the conceptualization of emotions that we address, in connection with corporality, becomes central to unraveling the processes of social structuration.

To delve into the characteristics of a specific sensitive regime, the connections between experiences, sociabilities, and sensibilities must be addressed, as forms of expression of the same. Experiences refer to how each person experiences and feels the world with others, and sociabilities imply the interactions of agents to live and coexist. The articulation/connection between these individual emotions and the socialites in which they develop are strained and twisted with sensibilities (Scribano 2010). Knowing these connections and forms of expression of the experiences/sociabilities/sensibilities of the digitalized world that are structured concerning food, allows us to think about how certain forms of presentation of the person are outlined (Goffman 2017), how ways of being and existing in bodies are enabled/conditioned (Sibilia 2013) and how emotional, feeling and exhibition rules prevail (Hochschild 1979), which define what should be felt and how those feelings should be expressed, in a specific space-time context.

Two sections will be presented below where the emotions that emerged from the analysis of the interviews with influencers and the digital ethnography process are exemplified.

4.1 Influencers’ emotions regarding digital work

This section presents the emotions of influencers regarding their work as content generators. These emerged from the in-depth interviews conducted. The interviews were conducted on three topics: emotions regarding photographing or filming food, when publishing food content, and when receiving likes.

Regarding the question about emotions when photographing and filming food, emotions such as pleasure, joy/fun, and, in some cases, tiredness and anxiety emerge.

People like photography. What was once a hobby becomes work, and pleasure arises from the act of photographing in general. This pleasure is related to the aesthetics of photography, dishes, presentations, and ways of eating.

On the other hand, joy and fun are expressed concerning the exhibition or representation of something through published content. Joy in sharing something and expressing emotions towards their followers, the audience on the other side of the screen. As two interviewees say: “If I had to say a emotion it would be joy, I like to be able to show through photos, real food, homemade, that transmits joy/love” (Interview 21, our translation); “I feel like it looks appetizing and makes others want to try making the recipe” (Interview 25, our translation).

However, on the other hand, the influencers also expressed their tiredness or laziness when taking photos or videos of food because they consider it “part of a daily process”, which takes time and is something more than their job. Also, because “sometimes it makes you tired or lazy” or “they want to finish the photo so they can eat”. This can be seen in several phrases, as can be seen in the following statement from one of the interviewees: “I feel a little lazy but I like it” (Interview 12, our translation).

The second dimension refers to the emotions that arise when publishing food content. There, the emergence of emotions such as happiness, pleasure, and gratification stands out. The emotions of happiness, in connection with “feeling good,” “I like it,” and “I love it” emerge as the most predominant, just as they arose when photographing.

Happiness adheres to the logic of showing through publications. Some interviewees said they were happy to contribute ideas and knowledge when publishing something: “Happy, it is super gratifying to feel that I contribute my grain of sand to facilitate organization in the kitchen” (Interview 3, our translation) and “Happy to be able to help with my recipes” (Interview 16, our translation).

On the other hand, for most influencers, pleasure was associated with the desire to share recipes and to inspire or transmit something through their publications. Phrases such as “I love publishing what I cook and inspiring others to cook” are examples. “The pleasure of being able to share a recipe made with a lot of love” (Interview 2, our translation) and “Also conveying that everyone can do it” (Interview 25, our translation) are also examples.

Thirdly, regarding what you experience when receiving likes, the predominant emotion is satisfaction, while indifference is the counterpart of this.

Some influencers said that it gave them satisfaction since likes are recognition and praise for their work. People who expressed this thought it was a sign that the work was being valued or that the published content was applicable. Here, too, joy and happiness are presiding over the emotions of the influencers, accompanied by satisfaction: “People like what I do and that gives me feedback to continue and improve” (Interview 4, our translation) and “I feel it as a compliment and support for my work” (Interview 3, our translation).

Some people expressed that they experience anxiety when publishing content due to the uncertainty that arises from not knowing if something will be liked or not at the time of publishing it: “I don’t care, it does give me anxiety (?) maybe at the time of publishing, of not knowing if something will go well or badly” (Interview 6, our translation).

However, others argue that receiving likes is part of their job, that they ignore it, and that “they don’t care”. In addition, it is essential to highlight that some influencers claim to prefer views or comments to likes because these two channels better show the other’s interest in the uploaded content. Some answers such as: “I don’t pay much attention to likes.I like receiving comments from people who made a recipe and it turned out well and they liked it (Interview 7, our translation), “I don’t pay much attention to likes, but I do pay attention to views, to how many people watched the video for how long. I like it when something goes really well but I don’t get too frustrated if it goes badly” (Interview 8, our translation), are examples of this. These contrasts in discourse can be observed from this expression of an interviewee: “It’s satisfying to see that someone likes what I do, but it doesn’t move me. I don’t give it that much importance today” (Interview 14, our translation).

4.2 Emotions concerning eating practices

As we have outlined, we will now present a unique analysis of the emotions that are embedded within the narratives of influencers in their publications. This analysis, based on our careful observation and recording of eating practices in the posts of influencers, reveals a distinct expression of vivencialities and sociabilities related to food.

In the narratives of the influencers, the prevalence of three emotions stands out: a) love, b) tiredness, and c) enjoyment, in connection with liking.

Love appears linked to three practices: cooking, sharing content, and eating with others. The following phrases taken from the posts of the influencers are examples of this:

Cooking

“Soft and marbled cake recipes SOFT CAKE (Mega spongy with a texture like a cloud) orange

with ingredients that we all have at home and very easy to make

with ingredients that we all have at home and very easy to make  Have you fallen in love yet? I’ve been in love with it for a while since I tried it for the first time

Have you fallen in love yet? I’ve been in love with it for a while since I tried it for the first time  ” (Record 21, our translation); “My love for doughs and boleros has no limits” (Record 6, our translation).

” (Record 21, our translation); “My love for doughs and boleros has no limits” (Record 6, our translation).Sharing content

“

Comprehensive program “Transform your habits”. A program that is born from love and the immense desire we have to accompany you to heal the relationship with your body and food” (Record 24, our translation); “Oatmeal cookie recipe. I love making cookies to give as gifts. A gift made with our hands, handcrafted and personalized seems to me a beautiful gesture of love.” (Record 16, our translation).

Comprehensive program “Transform your habits”. A program that is born from love and the immense desire we have to accompany you to heal the relationship with your body and food” (Record 24, our translation); “Oatmeal cookie recipe. I love making cookies to give as gifts. A gift made with our hands, handcrafted and personalized seems to me a beautiful gesture of love.” (Record 16, our translation).Eating with others

“Barbecue in Villa 31 that was broadcast on YouTube and other posts cooking on the beach in a kamado: summer love is the barbecue on the beach of Chapadmalal with cool people” (Record 1, our translation).

From these fragments, we can observe the unavoidable relationship between food and love. Thus, love appears related to food from different dimensions: cooking with love; falling in love with food and recipes; giving love through cooking; and transmitting/sharing information or recipes from love.

Regarding tiredness, this is related to planning the meal, tied to thinking about what to eat and cooking. Cooking causes tiredness and, in addition, it takes time. Examples of this are this publication where a recipe for cocoa waffles is presented:

Thinking about cooking/planning

“This is not a recipe for Sunday, but I recommend that you save it for the week when you are already tired of thinking about what to cook” (Record 3, our translation);

And this one that refers to the advertisement of some products to make a lunch that quickly solves the meal:

Cooking

“EXPRESS LUNCH MADE IN MOTORHOME

There are days when you just want to rest and enjoy the scenery, that is why my friend Mochi from @genteamigadistribuidora gave me these products so that I can solve the meal in minutes” (Record 25, our translation).

There are days when you just want to rest and enjoy the scenery, that is why my friend Mochi from @genteamigadistribuidora gave me these products so that I can solve the meal in minutes” (Record 25, our translation).It is important to note that the recipes or ideas presented in the posts are not for the weekend, but for those days when one is tired and does not have much time to devote to cooking, shopping, and other food-related activities.

On the other hand, enjoyment, in connection with liking, is expressed concerning sharing recipes and ideas, eating with others, and cooking:

Sharing content

“Express creamy chocolate cake recipe

I hope that when you make it you like it as much as I like to share each of my recipes and tips with you

I hope that when you make it you like it as much as I like to share each of my recipes and tips with you  ” (Record 22, our translation).

” (Record 22, our translation).Cooking

“Post with two recipes that I had promised! Enjoy it

send me your photos! (Record 17, our translation);

send me your photos! (Record 17, our translation);“STUFFED ZUCCHINI Works for any other vegetable

. If there is something I like, it is re-inventing traditional recipes and making them vegan

. If there is something I like, it is re-inventing traditional recipes and making them vegan  Let’s eat more plants

Let’s eat more plants  Let’s make the veggie version of everything

Let’s make the veggie version of everything  ” (Record 5, our translation).

” (Record 5, our translation).Eating with others

“Cooking unites, summons, conquers and enchants. It unites even if you don’t know how to cook. It unites aromas, flavors, anecdotes. Snacks that extend like conversations and become a tea dinner, a brunch or a snack. Because when we enjoy ourselves, we always have room and time for another slice of cake. In the middle of cooking and nature

we contemplate with all our senses, we take warm and genuine smiles” (Record 16, our translation).

we contemplate with all our senses, we take warm and genuine smiles” (Record 16, our translation).

Based on these reflections, the prevalence of three related emotions stands out: tiredness, love, and enjoyment/liking, which are linked to practices such as sharing content, cooking, eating with others, planning meals, and thinking about what to eat.

Our analysis of emotions reveals a complex interconnection between each influencer’s ways of experiencing the practice of eating and cooking, in connection with sociabilities, and the establishment of specific digital sensibilities regarding food. This intricate web forms the politics of digital sensibilities.

4.3 Emotions in tension

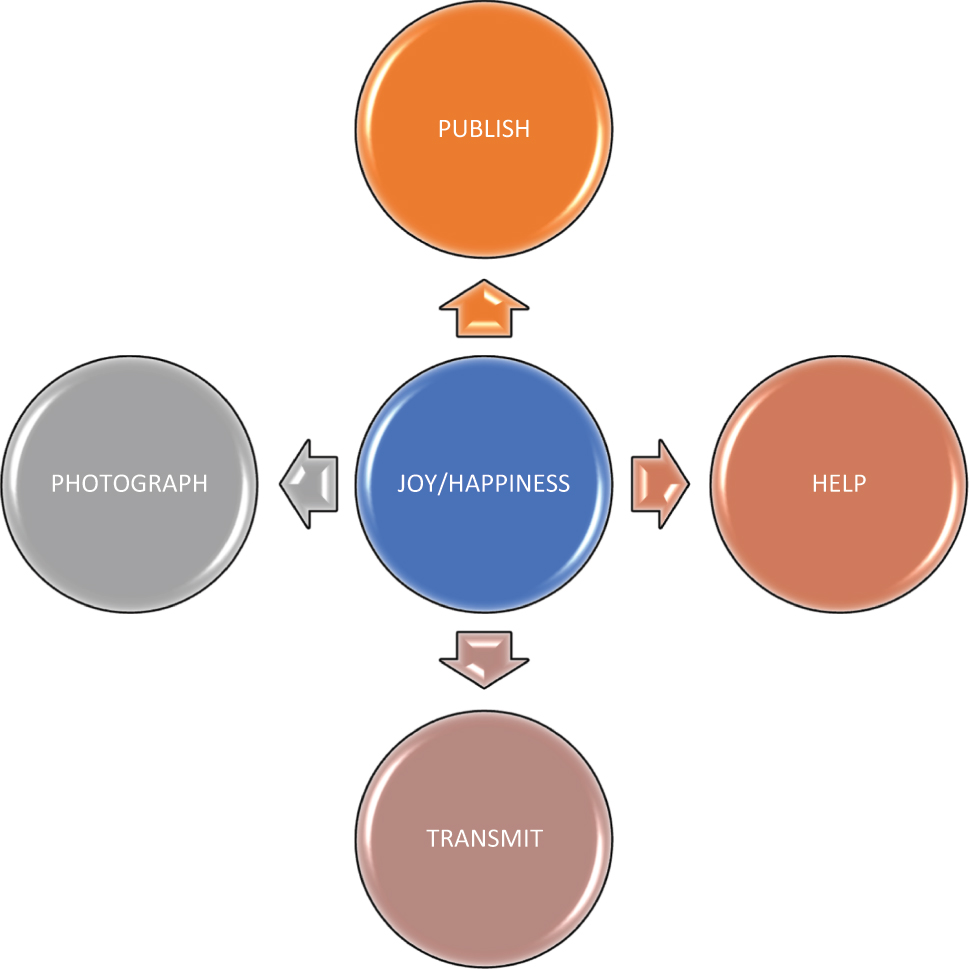

As observed in the previous analysis, many of the emotions that emerged from the interviews with influencers also appear in the content they publish on their Instagram profiles but refer to different practices or activities. This is how some possible connections between emotions and practices in tension in both registers are presented below in graphic form.

In Figure 1, we can see that enjoyment not only emerges in the narratives of the posts, associated with eating and cooking, but it is also an emotion that appears in some of the activities that influencers carry out, such as sharing content and photographs, tasks inherent to work as such.

Practices connected with enjoyment and liking.

From the Sociology of Bodies/Emotions, we connect enjoyment with consumption and the spectacularization of such, as a triad that expresses the construction of normalized societies in the Global South and the establishment of a certain political economy of morality (Scribano 2013). Here we can see how the imperative logic of enjoyment concerning food, interacts with the practice of showing/displaying that enjoyment on networks and with the constant consumption of objects/information/ideas through them. Two aspects of analysis can be established: the expression of enjoyment as a spectacularization of life, on the one hand, and immediate consumption together with the exhibition of it from social media profiles, on the other. These two, find in digital platforms, especially Instagram, a special setting for their establishment and reproduction. Instagram, being a highly visual network, where showing is the central axis of its operation, plays a significant role in the exhibition of enjoyment and immediate consumption.

Figure 2 presents four practices that are connected to joy and happiness. These four, helping, transmitting, photography, and publishing, are related to each other and, at the same time, are part of the influencer’s work to generate content and communicate it to their audience on social networks. Here, we can see that just as photography and sharing content involve enjoyment, these also appear connected to happiness.

Practices connected with joy and happinness.

Joy and happiness, in this case, refer to photography to help, transmit, and publish by showing something through the image and being able to inspire others. Let us take into account Aristotle’s conceptualization of happiness. We can see an intrinsic connection between making beautiful things, showing/reflecting beauty, and doing good things with the logic of transmitting sensations and inspiring others. Two practices in their connection imply imperatives about ways of being in particular bodies and life choices that refer to what is conceived as goodness and beauty.

In Figure 3, the practices that are connected to tiredness are highlighted. This appears in the interviews linked to photography (considering the different guidelines that must be considered to take high-quality food photographs) and in the publications related to planning and cooking.

Practices concerning tiredness.

Publishing a post can require dozens of steps, days or weeks of planning, and multiple skills, while the only thing seen from the platform is perfectly framed images of food (Hysmith 2022).

Tiredness also emerges in influencers’ narratives as a reason why it is necessary to provide ideas for recipes or meals to make and save in moments when “you are tired of cooking and thinking about what to eat.” These ideas are for when “you are tired of always performing, preparing and organizing,” but these ideas also imply planning, organizing, and optimizing time, so they can be understood as the obverse and reverse of the same problem.

Figure 4 expresses the practices that Love is related to cooking, eating with others, and sharing content.

Practices connected with love.

Love assumes a central space in the social construction of society, in the elaboration of subjectivity, in the articulation between agents, and in the energies that awaken emotions (Scribano 2020b). Love, as a social practice, implies action, movement, and reciprocity.

As Thomas (1923) argued, in the desires theory of personality formation, love is a central emotional expression that is related to the desire for response. It manifests itself in the tendency to seek and give signs of appreciation concerning other individuals, so that this desire is overdetermined to other desires and interferes with the normal organization of life, constituting the main source of altruism.

From this perspective, Love implies the necessary “reciprocity” generated by giving and feeling this emotion. Considering influencers’ different appeals to this emotion, such as sharing content, eating with others, and cooking, allows us to put in tension and make visible how this emotion is commercialized on the Instagram network through its monetization. The publications describe that influencers constantly resort to Love to obtain money from their followers, framed in a commercial logic because producing content and sharing it on their profiles implies paid work. Also, Love is related to the search for the gratification of these figures through comments, like buttons (in the shape of a heart) or continuous video reproductions, which monetize and commodify that emotion. We say that the logic of giving/generating Love is commodified because what prevails is not an act of selfless reciprocity but a search for what we could call “commodified reciprocity”, which is obtained from the like, reproduction, or comment on each publication.

In Figure 5, pleasure appears in the interviews linked to photography and publishing content practices. However, it also emerges in the publications to express the pleasure of sharing things through the platform. Likewise, pleasure is linked to the aesthetics of photography, dishes presentations, and ways of eating, which establishes the parameters for a culinary aesthetic.

Practices related to pleasure.

Figures 6–8 show three emotions connected to the practice of receiving likes: indifference, anxiety, and satisfaction. In this case, as in the analysis of tiredness, specific emotional ecologies are also stressed, on the one hand, emotions of indifference or anxiety, and on the other more positive side such as satisfaction. They can be thought of as opposite emotional states, but considering the analysis as a whole, these emotions account for the ambiguity produced by the remuneration of the influencer’s work.

Anxiety about receiving likes.

Satisfaction about receiving likes.

Indifference about receiving likes.

In summary, the figures express the connections between the analysis findings from digital ethnography and the interviews, focusing on specific interrelations in emotions. It can be observed how in the influencers’ posts, references to emotional ecologies such as love for sharing content, eating with others and cooking, tiredness referred to planning the meal, cooking, and liking/enjoying concerning eating with others and sharing content prevail. While in the interviews, it has been possible to elucidate the emergence of the logic of pleasure and happiness about showing/reflecting, sharing content and inspiring and transmitting something to the other, and satisfaction combined with indifference or tiredness, in some cases, concerning the work itself as influencers. As can be seen, some connections are established in the analysis of emotions: sharing content/showing, photographing, cooking, inspiring, and eating with others refer to an emotional ecology governed by love, pleasure, enjoyment, and happiness while planning and working as influencers refer to an emotional ecology where satisfaction, tiredness, anxiety and, to a certain extent, indifference are stressed.

Based on these activities and the subsequent analysis, we were able to reflect on the emotional ecologies that are combined with the transmission of food knowledge through digital media such as Instagram. In this case, the specificity of Instagram as a digital platform, the use of hashtags, and the work of influencers as content generators are vehicles for the current transmission of certain food knowledge, its valuation, and morality through images, advertisements, live broadcasts, and videos.

Based on the above, the influencer feels pleasure, love, happiness, and joy for generating this transmission of food knowledge. However, his work-generating content makes him tired and anxious due to his activities and working conditions. His work is around the clock, and perhaps it is interesting to think about the effects of creating his/her brand, which is his/her own life, his/her person, to guarantee a better functioning of the market, consumption, and marketing in capitalist society.

In this way, we can also see how the structuring regime of sensibilities concerning food is organized on Instagram. The lifestyles of the social group involved are reproduced on the platform, and from there, a specific sensibility is woven regarding cooking, eating healthy, organizing food, planning it, optimizing time, managing mealtimes, giving love through cooking, enjoying eating with others, exercising, among others. However, in line with Boragnio (2022), there are various ways to carry out these practices based on what is possible and accessible according to the available resources. From an intersectional and class perspective, we realize that not all people have the structural conditions that allow them to make these food choices and preferences that influencers convey.

In the context of worsening hunger and poverty, thousands of people cannot plan what to eat or with whom, and even less, they cannot organize meals that are subject to both state assistance and the solidarity of peers. Therefore, when we say that a specific process of structuring sensibilities regarding food is established on the Internet, we refer to the distinction that is made between those who can choose this way of eating and organizing food and those who cannot.

5 Concluding remarks

This article aims to put into tension the emotions of food influencers regarding their work as content generators, based on digital interviews, and emotions framed in the posts of these influencers regarding the transmission of food knowledge and food practices, based on a digital ethnography.

To do so, first, a brief tour of the means of transmission of food knowledge in Argentina was presented, including influencers and digital platforms such as Instagram. Next, some works on these figures were given, from different thematic areas, to outline the importance of thinking about what influencers feel, how they experience their work, and the sensibilities they wolve.

Then, the analysis established connections between the emotional ecologies related to food practices and content generation. As we have pointed out, this problematization results from a master’s thesis in social science research. Re-analyzing these emotional ecologies raises new concerns and questions, such as the one that refers to the similarities and differences between emotions, we find in Instagram posts and those that influencers recounted in the interviews conducted.

Moreover, it is crucial to critically analyze the influencer phenomenon in the context of technological advances and digitalization processes. This is essential for understanding the changing nature of labour, the emergence of new workspaces, the evolving relationship of workers with companies/brands/corporations, and the role of bodies and emotions in these contexts.

References

Abell, Annika & Dipayan Biswas. 2023. Digital engagement on social media: How food image content influences social media and influencer marketing outcomes. Journal of Interactive Marketing 58(1). 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/10949968221128556.Suche in Google Scholar

Aguirre, Patricia, Díaz Córdova, Diego & Gabriela Polischer. 2015. Cocinar y comer en Argentina hoy. [Cooking and eating in Argentina today in Spanish language]. Argentine: FUNDASAP, Sociedad Argentina de Pediatría.Suche in Google Scholar

Alakeson, Vidhya, Tim Aidrich, James Goodman & Britt Jorgensen. 2003. Making the net work: Sustainable development in a digital society. United States: Stylus Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Bericat, Eduardo. 2016. The sociology of emotions: Four decades of progress. Current Sociology 64(3). 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392115588355.Suche in Google Scholar

Boragnio, Aldana & Angélica De S & ena y Jeanie Maritza Herra Najera. 2022. Ayuda, Solidarismo y bienestar: sensibilidades en torno a “dar de comer” en iniciativas populares argentinas durante la pandemia de covid-19. In Sensibilidades, subjetividades y pobreza en América Latina, 45–66. CLACSO.Suche in Google Scholar

Borkenhagen, Chad. 2017. Death of the secret recipe: “Open source cooking” and field organization in the culinary arts. Poetics 61. 53–66.10.1016/j.poetic.2017.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

Caldo, Paula. 2016. En la radio, en el libro y en la televisión, Petrona enseña a cocinar. La transmisión del saber culinario, Argentina (1928–1960). Educaã§ã£o Unisinos 20(3). 319–327. https://doi.org/10.4013/edu.2016.203.05.Suche in Google Scholar

Contreras, Jesus & Gracia-Arnaiz, Mabel. 2005. Alimentación y cultura: Perspectivas antropológicas. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel.Suche in Google Scholar

Charles, Nickie & Marion Kerr. 1986. Eating properly, the family and state benefit. Sociology 20(3). 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038586020003008.Suche in Google Scholar

Deighton-Smith, Nova & Beth T. Bell. 2018. Objectifying fitness: A content and thematic analysis of #fitspiration images on social media. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 7(4). 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000143.Suche in Google Scholar

De Veirman, Marijke, Veroline Cauberghe & Liselot Hudders. 2017. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising 36(5). 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035.Suche in Google Scholar

Dinh, Thi Cam Tu, Mengqi Wang & Yoonjae Lee. 2023. How does the fear of missing out moderate the effect of social media influencers on their followers’ purchase intention? Sage Open 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231197259.Suche in Google Scholar

Feldman, Zeena. 2021. Good food’ in an Instagram age: Rethinking hierarchies of culture, criticism and taste. European Journal of Cultural Studies 24(6). 1340–1359. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211055733.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández Gómez, Jorge David, Victor Hernández-Santaolalla & Paloma Sanz-Marcos. 2018. Influencers, marca personal e ideología política en Twitter. Cuadernos.info 42. 19–37. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.42.1348.Suche in Google Scholar

Fischler, Claude. 1995. El (h)omnívoro El gusto, la cocina y el cuerpo [The (h)omnivore Taste, cooking and the body in Spanish language]. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.Suche in Google Scholar

Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Social Media a critical introduction. Nueva York: Sage Publishing.10.4135/9781446270066Suche in Google Scholar

Fumagalli, Andrea, Stefano Lucarelli, Elena Musolino & Giulia Rocch. 2019. El trabajo (labour) digital en la economía de plataforma: el caso de Facebook. Hipertextos 6(9). 12–41.Suche in Google Scholar

Fussey, Pete & Silke Roth. 2020. Digitizing sociology: Continuity and change in the Internet era. Sociology 54(4). 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520918562.Suche in Google Scholar

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. La constitución de la sociedad: bases para la teoría de la estructuración [The constitution of society: bases for the theory of structuring in Spanish language]. Cambridge: Politiy press.Suche in Google Scholar

Goffman, Erving. 2017. La presentación de la persona en la vida cotidiana [The presentation of the person in everyday life in Spanish language]. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.Suche in Google Scholar

Gomes Coelho, Olivia Blank & Alberto Cipiniuk. 2019. Quem influencia as influenciadoras digitais? Comunicação, tendência e moda no Instagram 12(24). 7–22.10.5965/1982615x12242019007Suche in Google Scholar

Gonzalez-Carrion, Erika Lucia & Ignacio Aguaded. 2019. Los instagramers más influyentes de Ecuador. Universitas, Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas (31). 159–174. https://doi.org/10.17163/uni.n31.2019.08.Suche in Google Scholar

Gracia-Arnaiz, Mabel. 1996. Paradojas de la alimentación contemporánea [Paradoxes of contemporary nutrition in Spanish language]. Barcelona: Icaria.Suche in Google Scholar

Hart, Dana. 2018. Faux-meat and masculinity: The gendering of food on three vegan blogs. Canadian Food Studies La Revue Canadienne Des études Sur l’alimentation 5(1). 133–155.10.15353/cfs-rcea.v5i1.233Suche in Google Scholar

Hijós, María Nemesia. 2018. Influencers, mujeres y running: Algunas consideraciones para entender los nuevos consumos deportivos y los estilos de vida saludable. Lúdica Pedagógica 1(27). 45–58. https://doi.org/10.17227/ludica.num27-9442.Suche in Google Scholar

Hochschild, Arlie Russel. 1979. Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology 85(3). 551–575. https://doi.org/10.1086/227049.Suche in Google Scholar

Hochschild, Arlie Rusel. 1990. Ideology and emotion management: A perspective and path for future research. In Theodore D. Kemper (ed.), Research agendas in the sociology of emotions, 117–142. New York: State University of New York Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hudders, Liselot & Steffi De Jans. 2022. Gender effects in influencer marketing: An experimental study on the efficacy of endorsements by same- vs. other-gender social media influencers on Instagram. International Journal of Advertising 41(1). 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1997455.Suche in Google Scholar

Hysmith, Katherine C. 2022. My life and labor as an Instagram influencer turned Instagram scholar. In Emily Contois & Zenia Kish (eds.), Food Instagram: Identity, influence, and negotiation, 191–204. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.10.5622/illinois/9780252044465.003.0013Suche in Google Scholar

Illouz, Eva. 2009. Emotions, imagination and consumption: A new research agenda. Journal of Consumer Culture 9(3). 377–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509342053.Suche in Google Scholar

Jerrentrup, Maja. 2023. The Grand Style. Encountering elderly influencers. Aisthesis 16(1). 147–158. https://doi.org/10.36253/Aisthesis-14379.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiménez-Castillo, David & Raquel Sánchez-Fernández. 2019. The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management 49. 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Kemper, Theodore D. 1978. A social interactional theory of emotions. New York: Wiley.Suche in Google Scholar

Kirkwood, Katherine. 2018. Integrating digital media into everyday culinary practices. Communication Research and Practice 4(3). 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2018.1451210.Suche in Google Scholar

Lavis, Anna. 2017. Food porn, pro-anorexia and the viscerality of virtual affect: Exploring eating in cyberspace. Geoforum 84. 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.05.014.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Kai-Sean & Chen-Wai Tao. 2021. Secretless pastry chefs on Instagram: The disclosure of culinary secrets on social media. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33(2). 650–669. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2020-0895.Suche in Google Scholar

Lofgren, Jennifer. 2013. Food blogging and food-related media convergence. M/C Journal 16(3). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.638.Suche in Google Scholar

Luna-Zamora, Rogelio. 2005. Sociología del miedo. Un estudio sobre las ánimas, diablos y elementos naturales [Sociology of fear. A study of souls, devils and natural elements. In Spanish language]. México: University of Guadalajara.Suche in Google Scholar

Lupton, Deborah. 2017. Digital media and body weight, shape, and size: An introduction and review. Fat Studies 6(2). 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21604851.2017.1243392.Suche in Google Scholar

Lupton, Deborah. 2020. Understanding digital food cultures. In Deborah Lupton & Zeena Feldman (eds.), Digital food cultures, 1–16. United Kingdom: Routledge.10.4324/9780429402135-1Suche in Google Scholar

Lupton, Deborah. 2021. Afterword: Future methods for digital food studies. In Jonatan Leer & Stinne Gunder Strøm Krogager (eds.), Research methods in digital food studies, 220–226. United Kingdom: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Luque García, Diego André. 2020. Construcción de identidad en la red social Instagram a través de prácticas discursivas: caso Influencers, categoría comida. Ecuador: Universidad Casa Grande.Suche in Google Scholar

MacGregor, Casimir, Alan Petersen & Christine Parker. 2021. Promoting a healthier, younger you: The media marketing of anti-ageing superfoods. Journal of Consumer Culture 21(2). 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540518773825.Suche in Google Scholar

Mairano, Maria Victoria. 2024. Emotions and food digital practices on Instagram, between the algorithms and the big data. In Adrian Scribano & Maximiliano Korstanje (eds.), AI and Emotions in digital society, 75–95. United States: IGI Global.10.4018/979-8-3693-0802-8.ch004Suche in Google Scholar

Martynowskyj, Estefania & Constanza María Ferrario. 2021. “¿Probaste el sexo virtual?”: discurso sexológico y cultura digital en épocas de covid-19. Revista de Ciencias Sociales IV(174). 223–243. https://doi.org/10.15517/rcs.v0i174.52175.Suche in Google Scholar

Mennell, Stephen, Anne Murcott & Anneke H. Van Otterloo. 1992. The sociology of food: Eating, diet and culture. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Nagao Menezes, Daniel Francisco. 2020. Las perspectivas del trabajo en la sociedad 4.0. Revista Nacional de Administración 11(1). 11–19. https://doi.org/10.22458/rna.v11i1.3011.Suche in Google Scholar

Navarro-Beltra, Marian & Laura Herrero Ruiz. 2020. El Engagement generado por los influencers gastronómicos: el caso de Instagram. In Javier Sierra Sánchez y Almudena Barrientos Báez (ed.). Cosmovisión de la comunicación en redes sociales en la era postdigital, 357–374. España: Mc Graw Hill.Suche in Google Scholar

Pite, Rebekah. 2016. La mesa está servida. Doña Petrona C. de Gandulfo y la domesticidad en la Argentina del siglo XX [. La mesa está servida. Doña Petrona C. de Gandulfo y la domesticidad en la Argentina del siglo XX in Spanish language]. Buenos Aires: Edhasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Powell, Katie, John Wilcox, Angie Clonan, Paul Bissell, Louise Preston, Marian Peacock & Michelle Holdworth. 2015. The role of social networks in the development of overweight and obesity among adults: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 15. 996. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2314-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Saez, Victoria. 2022. De lectores a “influencers”: Booktubers, bookstagrammers y booktokers y la circulación de la literatura en redes sociales en Argentina. Pilquen: Sección Ciencias Sociales 25(2). 20–46.Suche in Google Scholar

Sanchez de Bustamante, Marina, Justo Von Lurzer & María Carolina. 2021. Influencers y Mompreneurs: una exploración por el repertorio digital de la maternidad. Artemis 31(1). 222–236. https://doi.org/10.22478/ufpb.1807-8214.2021v31n1.60141.Suche in Google Scholar

Schneider, Tanja & Karin Eli. 2021. Fieldwork in online foodscapes: How to bring an ethnographic approach to studies of digital food and digital eating. In Jonatan Leer & Stinne Gunder Strøm Krogager (eds.), Research methods in digital food studies, 71–85. United Kingdom: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian. 2010. Cuerpo, Emociones y Teoría Social Clásica. Hacia una sociología del conocimiento de los estudios sociales sobre los cuerpos y las emociones. In Jose Luis Grosso & Maria Eugenia Boito (eds.). Cuerpos y Emociones desde América Latina. Córdoba: UNCa.Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian. 2012. Sociología de los cuerpos/emociones. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios sobre Cuerpos, Emociones y Sociedad 10(4). 91–111.Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian. 2013. Una aproximación conceptual a la moral del disfrute: normalización, consumo y espectáculo. RBSE – Revista Brasileira de Sociologia da Emoção 12(36). 738–750.Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian. 2020a. La vida como Tangram: Hacia multiplicidades de ecologías emocionales. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios sobre Cuerpos, Emociones y Sociedad 33(12). 4–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian. 2020b. Love as a collective action. Latin America, emotions and interstitial practices. United Kingdom: Routledge.10.4324/9780429283703Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian. 2023. Emotions in a digital world: Social Research 4.0. United Kingdom: Routledge.10.4324/9781003319771Suche in Google Scholar

Scribano, Adrian & Pedro Lisdero. 2019. Digital labor, society and politics of sensibilities. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-12306-2Suche in Google Scholar

Sibilia, Paula. 2013. El artista como espectáculo: autenticidad y performance en la sociedad mediática. Dixit(18). 4–19. https://doi.org/10.22235/d.v0i18.360.Suche in Google Scholar

STATISTA. 2023. Influencer marketing worldwide. Statistics & Facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/2496/influence-marketing/#topicOverview.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomas, W. I. 1923. The wishes. In The Unadjusted Girl with cases and standpoint for behavior analysis, 1–40. Boston: Little Brown and Company.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Emotions, society, and influencers in the digital era

- Research Articles

- Influencing eating choices, manipulating emotions, & the influencer: an ethnography

- Emotions of food influencers regarding digital work and the transmission of food knowledge on Instagram

- What makes a super influencer? Testing the origin of fame theory in China

- “How come I don’t look like that”: the negative impact of wishful identification with influencers on follower Well-being

- Mexican queer influencers: corporeal-emotional social reconfigurations

- Social media influencers and followers’ loneliness: the mediating roles of parasocial relationship, sense of belonging, and social support

- Content creators as social influencers: predicting online video posting behaviors

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Emotions, society, and influencers in the digital era

- Research Articles

- Influencing eating choices, manipulating emotions, & the influencer: an ethnography

- Emotions of food influencers regarding digital work and the transmission of food knowledge on Instagram

- What makes a super influencer? Testing the origin of fame theory in China

- “How come I don’t look like that”: the negative impact of wishful identification with influencers on follower Well-being

- Mexican queer influencers: corporeal-emotional social reconfigurations

- Social media influencers and followers’ loneliness: the mediating roles of parasocial relationship, sense of belonging, and social support

- Content creators as social influencers: predicting online video posting behaviors