Abstract

Purpose

Building on Social Comparison Theory and Parasocial Relationship Theory, this study is designed to investigate how followers’ wishful identification with YouTube influencers is associated with their psychological well-being and how parasocial relationships with influencers moderate this association.

Design/methodology/approach

Influencer-fan data (N = 504) is collected through a Qualtrics survey in collaboration with a real-life influencer on YouTube. Hayes Process Modeling was used to conduct mediation and moderation analyses.

Findings

Results indicate that enjoyment of influencers’ videos positively leads to followers’ wishful identification, which negatively impacts their well-being. The parasocial relationship with the influencer was found to be a significant moderator on the negative relationship between wishful identification and follower well-being in the models with vlog-oriented videos and skincare videos as independent variables.

Practical implications

This study provides guidance for influencers regarding the behaviors to lower the negative psychological impact of their videos on viewers. While influencer content creation is a thriving business, the association between influencer-following and viewer’ mental health issues should not be overlooked.

Social implications

From the viewers’ perspectives, awareness of social media comparison with influencers and the filtered effects of social media communication are also discussed.

Originality/value

As influencers continue to gain prominence on social media, their influence on followers extends beyond providing information, entertainment, companionship, and product endorsements. This study examines the negative effects of influencer content on viewers’ psychological well-being, particularly through mechanisms of social comparison and parasocial relationships.

1 Introduction

Social media influencers are inevitable in today’s digital life. Travel influencers give us a closer look at experiences in another country through their lenses. Food influencers offer dietary advice to people who need special care. Fitness influencers accompany us during workouts and sometimes save us the expense and effort of hiring a personal trainer. Fashion influencers provide endless recommendations on the next season’s trendy outfits. In the modern digital age, no matter what you wish to purchase, you can always find an influencer who specializes in reviewing products of that industry. Previous research on the effects of social media influencers are focused on their economic impact (e.g. Bi and Zhang 2022), some questions remain unanswered: Are social media influencers making us happier or less happy? What factors contribute to that impact? What types of influencers’ content are making us happier or less happy? Literature gives us a mixed result. Influencers, most of the time, have higher physical attractiveness than non-influencers, which is one of the reasons for their popularity on visual digital platforms. However, research has found that they can exert a negative influence on their follower regarding body dissatisfaction and appearance comparison (Prichard et al. 2023). On the other side, following influencers who promote self-love and body positivity can increase audience senses of self-worth and positive perception of their looks (Fiorvanti et al. 2023).

To answer these questions, this study is designed in collaboration with a real-life YouTube influencer CeciCchen, to study the impact of her videos on the psychological well-being of her followers. The study aims to disentangle the relationship between product review influencers and their followers’ psychological wellbeing through the lenses of parasocial relationships, the one-sided relationship between influencer and followers, and wishful identification, followers’ desire to behave and present like an influencer.

This study is unique in the following aspects. First, the data collection is administered directly through a real influencer, granting the research a higher possibility to reach real-life followers of influencers than collecting data from crowdsourcing agencies like Amazon Mechanic Turk, Qualtrics, or Survey Monkey. Second, the study aims to clarify the mediating and moderating roles that parasocial relationships and wishful identification play in the impact of influencers on viewers’ well-being. Third, the study calls for influencers’ attention to reflect on their practices with not only a traffic-centric perspective but also an ethical concern about how their content can impact the mental health and well-being of their viewers.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Social comparison in the age of influencers

Social comparison is the act of a person comparing themselves with others to evaluate themselves or improve themselves (Suls et al. 2002). In order to coordinate behaviors, relationships, and overall society, humans use social comparison to better understand what others behave and feel (Baldwin and Mussweiler 2018; Helgeson and Mickelson 1995; Katja et al. 2011). This is especially important in societies that promote collectivism and punish deviance from societal norms (Baldwin and Mussweiler 2018; Helgeson and Michelson 1995). Social media is like a digital society that fosters and rewards conforming to norms (O’Hagan et al. 2018; Ovard Johnson 2020; Yoo et al. 2014). Over the past two decades, social media use has risen (Hall and Liu 2022). Increased use of social media allows for a digital venue for social comparisons to take place from the comfort of your own home. Increased use of social media is a factor positively associated with increased social comparison with friends.

Social media is a digital venue where individuals can view content created by their social circle, as well as other members of the general public. For people such as influencers, this digital landscape can serve as an environment to create and cultivate their own desirable and marketable commercialized brands (Bakker 2018). As such, the opportunities for influencer-focused social comparison increases. The exposure to influencers’ content both on their individual pages and through various marketing formats gives users more opportunity to view images carefully created by influencers. Viewing images of influencers has been found to increase viewers’ negative mood, body satisfaction, and appearance comparison (Prichard et al. 2023). When viewing sexualized influencer images, these negative comparison factors were higher than when viewing fashion-based imagery (Prichard et al. 2023). Previous research has also revealed that social media influencers can diminish consumer well-being through the mediation of Fear of Missing Out (Barari 2023). The glamorized feature of influencer might also foster followers’ problematic engagement with influencers, such as obsession with a certain influencer and feelings of disconnection if not consistently checking an influencer’s account (Farivar et al. 2022). Influencers often showcase an idealized version of themselves on social media. This self-presentation can create unrealistic standards for viewer comparison. Increased negative social comparison of users towards influencers was positively associated with users’ subsequent impulse purchasing (Mundel et al. 2023). This was mediated by both anxiety and social media addiction.

2.2 Wishful identification, parasocial relationship, and viewer well-being

Various persuasive elements can increase the impact that an influencer has on its viewing audience (Moyer-Gusé 2008). Two such elements include wishful identification (WI) and parasocial relationships (PSR) (Notonegoro and Aruan 2024). Parasocial relationships are growing increasingly prevalent in modern society. As of 2017, roughly 60 % of adolescents reported viewing their favorite media figure as a relationship partner, leading to increased parasocial interactions and emotional intensity towards the figure (Gleason et al. 2017). Young boys viewed these relationships like mentorships while young girls viewed these relationships as akin to friendships (Gleason et al. 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of PSRs increased, in part due to the restrictions hindering the maintenance of in-person relationships. The increased population reliance on social and digital media to create connections fostered a form of social surrogacy increasing parasocial interactions (Jarzyna 2021).

Social media use has been found to influence a person’s creation of parasocial relationships with celebrities (Tolbert and Drogos 2019). While PSRs can increase feelings of connectedness they can also negatively impact user mental health (Hoffner and Bond 2022). User dependence on such relationships is positively related to loneliness (Baek et al. 2013). Depending on if an influencer a person has a PSR with promotes healthy or unhealthy behaviors can also impact viewer behaviors as being healthy or unhealthy (Hoffner and Bond 2022). Viewers with PSRs also have been linked to experience depression, anxiety towards body image, and lower self-esteem (Seekis et al. 2020). Conversely viewing and having parasocial relationships with influencers who promote self-love and positive body image can increase these factors in viewers (Fiorvanti et al. 2023). Parasocial relationships and WI with a television or film character have been found to affect viewers’ positive and negative behavior depending on which traits are presented by the character (Bond and Drogos 2014).

Users of social media often also experience WI towards celebrities and influencers (Hu et al. 2020). Wishful identification refers to a person’s desire to behave or present like a media figure (Feilitzen and Linne 1975). Factors including trust, perceived physical attractiveness, perceived social attractiveness, and popularity can increase the likelihood a viewer will experience wishful identification with an influencer (Kim et al. 2023). One study showed that gender impacted the traits a person wishfully identified with (Hoffner and Bond 2022). Men identified more with male characters who were perceived as intelligent, violent, and successful (Hoffner and Bond 2022). Women on the other hand identified more with female characters that they deemed successful, attractive, and admired (Hoffner and Bond 2022). Wishful identification also can impact views on body image (Greenwood 2009; van Drimmelen 2023). One study found that women who experience WI with their favorite female character in a television or film are predicted to experience body shame (Greenwood 2009). In addition, body surveillance was positively associated with wishful identification of female media characters (Greenwood 2009). Another study found that social comparison and wishful identification mediate the relationship between viewers watching fitness influencers’ content and viewer body satisfaction with viewers who experienced higher levels of wishful identification having lower reported body satisfaction (Drimmelen 2023).

Wishful identification and PSR have been found to have an effect on one another. Studies have shown that WI has a positive influence on PSR (Notonegoro and Aruan 2024). Wishful identification and PSR have also been found to be mediators in the relationship between exposure to celebrities and viewer attitudes and behaviors (Bond and Drogos 2014). Audiences, however, identify with influencers and trust them more than they do celebrities (Schouten et al. 2021). The nature of influencers being their own brand allows them to interact more directly with fans in a way that can foster connections. Schouten et al. found that wishful identification and trust served as mediating factors in the relationship between a type of endorser and a form of advertising’s overall effectiveness (2021). Influencers however do not only market for companies but market their overall individual brand making their own character attributes and traits seem desirable (Vasconcelos and Ruo 2021). This desire to be more like an influencer can impact viewer well-being. Based on these findings from previous literature, we propose the following research question and hypotheses:

RQ1:

What are the relationships among viewers’ enjoyment of an influencer’s videos, their wishful identification with the influencer, and their psychological well-being?

H1:

Viewers’ enjoyment of an influencer’s videos is positively associated with their wishful identification with the influencer.

H2:

Viewers’ wishful identification with the influencer is negatively associated with their psychological well-being.

H3:

Viewers’ enjoyment of an influencer’s videos is negatively associated with their psychological well-being.

H4:

Viewers’ parasocial relationship with the influencer moderates the impact of their wishful identification with the influencer on their psychological well-being.

H5:

Viewers’ parasocial relationship with the influencer moderates the impact of their enjoyment of an influencer’s videos on their psychological well-being.

2.3 Video types preference and viewer well-being

Influencers publish various types of content, including vlogs, product reviews, lifestyle advice, tutorials on making food, and political commentaries. Discrepancies might exist regarding the impact of different types of influencer-published content on viewers’ tendency of wishful identification, the construction of parasocial relationships with the influencer, and their psychological well-being.

Existing research has described the relationship between vlogs and well-being, through direct (Berryman and Kavka 2018; Goedhart et al. 2022; Jacobs and Kelemi 2020) or indirect (Schmuck 2021; Hoek et al. 2020) relationships. The focus of relevant research includes social well-being (Schmuck 2021), psychological well-being (Goedhart et al. 2022; Jacobs and Kelemi 2020), and mental well-being (Berryman and Kavka 2018). Schmuck (2021) found that videos created by vloggers followed by adolescents between the ages of 10 and 14 can have a negative impact on the social well-being of adolescents. Research has also confirmed a negative association between watching influencers’ vlogs and adolescents ’ development of fear of missing out (FoMO), which further negatively impacted their social well-being (Goedhart et al. 2022).

On the other hand, influencers’ vlogs can generate a positive impact as well. Research has found that cocreated vlogs with community partners can generate meaningful interactions with teenagers living in disadvantaged circumstances (Goedhart et al. 2022). This study among residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, showed that co-creating vlogs on healthy food helped teenagers embrace a healthier lifestyle. It was also found that co-creating vlogs helped women in the community learn digital skills, and enhance their sense of satisfaction. In addition, other studies have also looked at the role of female YouTube vloggers on viewers’ well-being and self-awareness. Evidence showed that in the early stages, vloggers from South Africa developed fixed definitions of beauty, insecurities about their own hair styling, and damage from long-term hair straightening (Jacobs and Kelemi 2020). Jacobs and Kelemi (2020) highlighted that as vloggers continue to change their standards as they grow, and reach self-acceptance and self-actualization, their followers, along with them, gain support from their recorded vlogs. The significance of this study lies in the process by which black female viewers gain self-esteem and confidence and achieve better psychological well-being from watching natural hair stories and learning about how to deal with curly hair (Jacobs and Kelemi 2020). Meanwhile, the research explored the economic and emotional effects of vloggers posting videos expressing negative emotions (Berryman and Kavka 2018). Empirical results showed that negative emotional vlogs can cement a close relationship with followers and enhance authenticity while the vlogger engages in self-disclosure. In a way, it helped build a community with viewers who need mental well-being support and raised awareness of their lives and well-being (Berryman and Kavka 2018).

Product-reviewing video is a popular genre in influencers’ content-creation. Driving sales and consumption of products is one of the main effect of influencers’ media content, and it brings commissions back to influencers as a result. However, it is not only about the money, but also relationship building. The relationship between influencers and viewers is complex. Many studies have explored the fields of feminism (Duan 2020), fashion decisions (Aslam et al. 2022; Quelhas-Brito et al. 2020) and body image (Feijoo et al. 2022; Pan et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2021) from different perspectives. One study found that patterns of collaborations between female empowerment bloggers and women’s products included narrative discourses about female empowerment (Duan 2020). They resonate through deliberate self-disclosure. The proposition of “big women” will increase the courage of female fans to break stereotypes and be themselves, and enhance the power of confidence in their own abilities (Duan 2020). In this way, fans and influencers are able to build intimacy. The study by Aslam et al. (2022) found that compared with other persuaders, followers found influencers are more sincere, informative, and trustworthy. Viewers believe their suggestions, so their buying intention and shopping attitudes are positive under the impact of the influencers (Aslam et al. 2022). Research focusing on social media fashion influencers has shown that fashion influencers can exert fashion leadership over fans during self-expression, and followers rely on the fashion trends provided by them to guide their fashion decisions (Quelhas-Brito et al. 2020). In addition to this, there is a relationship between the idealized body image of social media users and the mental health of young female viewers. The result shows that when there is little difference between the idealized body image and oneself, it has a positive effect on the audience’s mental health and physical satisfaction, which helps to stimulate the motivation of fans to improve themselves (Zhang et al. 2021). However, the frequency of exposure to the relevant content did not have a significant effect on them. At the same time, self-discrepancy (Zhang et al. 2021) and social comparison tendencies (Pan et al. 2022) would play important roles. This mutual effect is more obvious among young followers. Internet celebrities’ eating habits and physical features will also affect their self-esteem and other habits, and further affect their personal well-being (Feijoo et al. 2022).

Aside from vlogs and product-reveiw videos, one perticular genre of videos is also worthy of scholarly attention, which is skincare videos, including invasive or non-invasive skincare measures. Influencers on social media can share their skincare tutorials as a way to empower viewers with the tools to “look better”. However, viewers might also feel under the pressure of “having to look better” to purchase expensive skincare products or devices. Skincare recommendation might also overlap with giving medical advices, while most influencers on social media are not certified dermatologist. Beauty influencers can not only establish their platform as an interface for the brand to interact with its potential audience but also impact followers on a spiritual and conceptual level. Lu and colleagues (2024) conducted a comparative study on the characteristics and types of video influencers, including beauty influencers and technical influencers. The results showed that the visual beauty, authenticity, and physical attractiveness of the videos posted by beauty influencers significantly changed the hedonic value of followers (Lu et al. 2024). Makeup and skincare can be seen as an intrinsic motivation that has a direct impact on self-esteem, manifesting relationships, creativity, mastery, and more in the process (Tran et al. 2020). Sometimes makeup and skincare might make women move closer to the standard aesthetic, avoid the production of guilt feelings, and help to maintain positive emotions and gain confidence (Tran et al. 2020). Social media influencers are making the beauty industry more relevant to everyday life while increasing cultural diversity. The beauty knowledge, attraction and affinity displayed by the influencer can be defined by the followers as a confident display, satisfying the followers’ pursuit of practicality and establishing a more sincere relationship (Hermans et al. 2022). The presence of influencer who have undergone plastic surgery in their followers’ attention lists increases their acceptance of cosmetic surgery and lowers the threshold for normalizing plastic surgery (Hermans et al. 2022). It found that frequent exposure to relevant content makes them produce a look-centric imitation mentality, hoping to obtain the same cosmetic appearance as the influencer through the same surgery (Hermans et al. 2022).

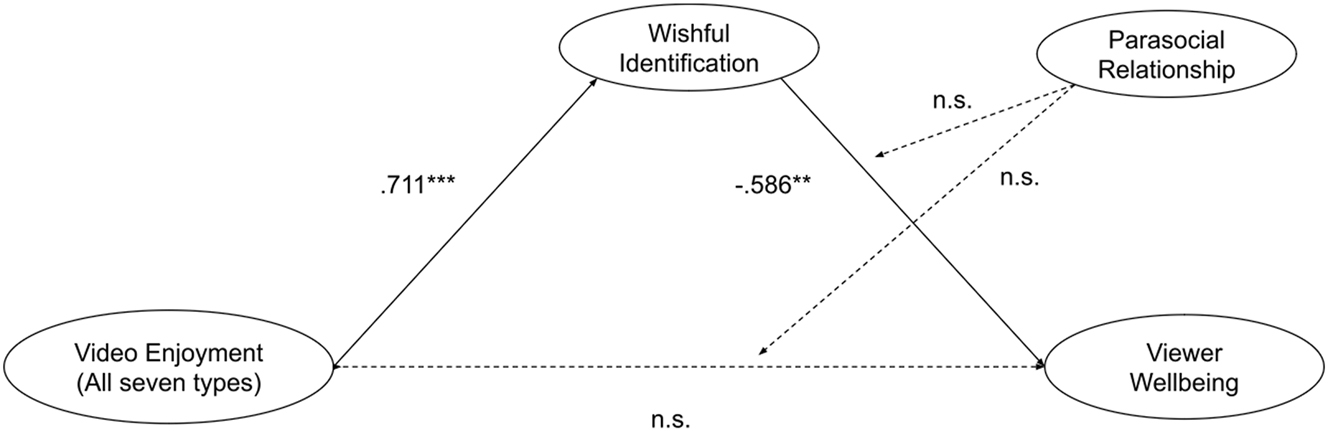

Proposed research model.

Based on previous research on the impact of various influencer-created content types on viewers, we propose the following research model (Figure 1) and research question:

RQ2:

How do viewers’ preference for different types of influencer-created videos impact their wishful identification, parasocial relationship, and psychological well-being?

3 Methods

3.1 Sampling

To test the research question and the hypotheses, an online questionnaire was created on Qualtrics. The data collection was completed in collaboration with a real-life YouTube influencer CeciCchen, who specializes in reviewing beauty and fashion items and has 73.7 k followers on YouTube on April 8th, 2024. She currently resides in the US and her videos are in Chinese, targeting mandarin-speaking Chinese communities living in the US. The questionnaire was in Chinese. She asked her followers to complete the questionnaire in her video published on Feb 5th, 2024, and announced a lucky draw of winners to receive gift cards of gifts if her viewers completed the survey before Feb 24th, 2024. With IRB approval, a total of 1000 USD was granted to gift 20 of her viewers. A total of 779 participants completed the survey. However, 275 of the recruited participants had a significant number of questions incomplete before leaving the survey. Thus, the final sample size of the study is N = 504. Regarding sample demographics, please see Table 1.

Sample Demographics.

| Variable | Categories | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 | 1.2 % |

| Female | 486 | 96.4 % | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 3 | 0.6 % | |

| Age | 19–24 | 76 | 15.1 % |

| 25–34 | 309 | 61.3 % | |

| 35–44 | 92 | 18.3 % | |

| Above 44 | 7 | 1.4 % | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 20 | 4.0 % | |

| Income | Below 3,000 RMB | 48 | 9.5 % |

| 3,000–5,000RMB | 67 | 13.3 % | |

| 5,000–8,000RMB | 81 | 16.1 % | |

| 8,000–15,000 RMB | 102 | 20.2 % | |

| 15,000–25,000RMB | 65 | 12.9 % | |

| 25,000–40,000 RMB | 61 | 12.15 | |

| 40,000–60,000 RMB | 23 | 4.6 % | |

| 60,000–120,000 RMB | 20 | 4 % | |

| More than 120,000 RMB | 21 | 4.2 % | |

| Education | High School Diploma | 13 | 2.6 % |

| Bachelor Diploma | 271 | 53.8 % | |

| Graduate Diploma | 165 | 32.7 % | |

| Doctoral Diploma | 27 | 5.4 % |

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Video enjoyment/preference

To assess participants’ different levels of preference for different types of video, seven questions were asked: “How do you like the following categories of videos” - “Shopping haul videos”, “vlogs (life recording videos)”, “skincare videos”, “GRWM (get ready with me) videos”, “monthly favorites”, “sales recommendations”, and “cosmetic empty bottle videos” (M = 6.03, SD = 0.71, α = 0.79).

3.2.2 Wishful identification

To evaluate participants’ wishful identification with the YouTuber, a 7-point scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree” was employed across 5 items, including: “I think Ceci is the kind of guy I want to be.” “In some ways, I would like to be more like Ceci.” “I wish I could be like Ceci at work.” “I wish I could be like Ceci in life.” and “In some ways, Ceci is someone I want to emulate.” The scale is modified from the scale used by Hoffner and Bond (2022) (M = 5.56, SD = 1.14, α = 0.94).

3.2.3 Parasocial relationship

To examine participants’ parasocial relationship with the YouTuber, a 7-point scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree” was used on 10 items. The scale is modified from the scale used by Rosaen and Dibble (2016). The items include: “When you watch my videos, I make you feel like your friend.”, “I make you feel accompanied when you watch my videos.”, “You can look forward to seeing my next video.”, “If I stop posting for a while, you’ll miss me.”, and “You feel like I am dependable as your friend.” (M = 5.98, SD = 0.84, α = 0.94).

3.2.4 Viewer wellbeing

To investigate participants’ psychological wellbeing, six questions were asked on a 7-point scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”, including: “How have you been in the past year?” - “very optimistic about the future”, “full of interest in the people and things around”, “overall very happy”, “always feel lonely (reversed)”, “not interested in new people and things (reversed)”, and “I feel bad most of the time (reversed).” The scale is adapted from the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) (Tennant et al. 2007). (M = 5.01, SD = 1.11, α = 0.84).

3.2.5 Control variables

Control variables were utilized to deepen the understanding of the relationship between endogenous and exogenous variables. For this aim, demographic factors of gender, education level, and income were measured.

3.3 Statistical strategies

After running reliability tests of measured scales, composites were made for each latent variable. Correlation analyses were performed to test the relationship among variables. Afterward, mediated moderation analyses were performed based on the proposed path diagram through SPSS PROCESS Modeling v4 by Andrew F. Hayes. Finally, to test the discrepancy among different video types, three separate mediated moderation analyses were performed using three different independent variables of video enjoyment/preference.

4 Results

4.1 Correlations

In an examination of the relationship among key variables, a Pearson’s correlation was conducted. Results indicated significant and positive correlations among the tested variables. See Table 2 for detailed correlation results.

Correlation test Results.

| Variables | VE/P | WI | PSR | VW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video enjoyment/Preference | 1 | |||

| Wishful identification | 0.456** | 1 | ||

| Parasocial relationship | 0.557** | 0.678** | 1 | |

| Viewer wellbeing | 0.215** | 0.024 | 0.217** | 1 |

-

Note: p < 0.001***. p < 0.01**. p < 0.05*.

4.2 Mediated moderation analysis

To test the mediation of wishful identification between video enjoyment/preference and viewer well-being, and the moderation of parasocial relationship, Hayes PROCESS Model 4 tests were performed on SPSS with 5,000 bootstrap samples of 95 % confidence intervals. First, we tested the model using a composite of all seven video enjoyment/preference measures. The moderated mediation effect was significant, B = 0.0466, SE = 0.0338, 95 % CI [0.0075, 0.1406]. Results indicated that higher enjoyment of a variety of types of influencer videos is positively associated with wishful identification B = 0.7113, SE = 0.0652, 95 % CI [0.5832, 0.8393], which further leads to a lower level of viewer well-being B = −0.5860, SE = 0.2224, 95 % CI [−1.0230, −0.1490], supporting both H1 and H2. The direct effect of video enjoyment/preference on viewer well-being was not significant, partially rejecting H3, nor was the moderating effect of parasocial relationships, partially rejecting H4 and H5. Regarding control variables, out of the three control variables, income, education, and gender, only income was significantly associated with viewer well-being B = 0.1115, SE = 0.0235, 95 % CI [0.0653, 0.1577]. See Figure 2 for detailed results.

Hayes PROCESS Modeling results for all video types.

To further answer RQ2 and test the proposed model based on different types of videos that the participants prefer to watch, the independent variable video enjoyment/preference is divided into three variables: vlog-oriented videos, product-oriented videos, and skincare videos. Vlog-oriented video preference is a composite variable including preference for vlogs and “Get Ready With Me” style videos, which are focused on chitchatting and life recording of the influencer. The moderated mediation model was significant, B = 0.0341, SE = 0.0201, 95 % CI [0.0100, 0.0881]. Vlog-oriented video preference was significantly impacting wishful identification B = 0.4704, SE = 0.0471, 95 % CI [0.3778, 0.5629], which was further negatively associated with viewer wellbeing B = −0.6225, SE = 0.2199, 95 % CI [−1.0547, −0.1904]. The parasocial relationship with the influencer was a positive moderator of the relationship between wishful identification and viewer wellbeing B = 0.0726, SE = 0.0354, 95 % CI [0.0031, 0.1421], partially supporting H4. Income, out of the three control variables, income was the only significant predictor of viewer wellbeing B = 0.1138, SE = 0.0237, 95 % CI [0.0674, 0.1604]. See Figure 3 for detailed results.

Hayes PROCESS Modeling results for vlog-oriented videos.

Regarding the impact of product-oriented video preference on viewer wellbeing, the research model was tested with the independent variable being a composite of four measures on video preference for shopping hauls, monthly favorites, sales recommendations, and empty bottle videos featuring products that have been recently used up by the influencer. The moderated mediation effect was significant, B = 0.0389, SE = 0.0234, 95 % CI [0.0044, 0.1006]. Results indicated that enjoyment of product-oriented videos is positively associated with wishful identification B = 0.5617, SE = 0.0681, 95 % CI [0.4279, 0.6955], which further leads to a lower level of viewer well-being B = −0.5961, SE = 0.2210, 95 % CI [−1.0303, −0.1618]. The direct effect of product-oriented video preference on viewer well-being was not significant, nor was the moderating effect of parasocial relationships. Regarding control variables, out of the three control variables, income, education, and gender, only income was significantly associated with viewer well-being B = 0.1110, SE = 0.0236, 95 % CI [0.0647, 0.1573]. See Figure 4 for detailed results.

Hayes PROCESS Modeling results for product-oriented videos.

Last but not least, a separate test was performed on skin care video preference. Skincare-themed videos created by the collaborated influencer feature content beyond just moisturizers, such as non-invasive cosmetic procedures (for example, microneedling) and skin improvement tools that help with skin elasticity. The moderated mediation model was significant, B = 0.0230, SE = 0.0118, 95 % CI [0.0001, 0.0485]. Vlog-oriented video preference was significantly impacting wishful identification B = 0.3128, SE = 0.0412, 95 % CI [0.2318, 0.3938], which was further negatively associated with viewer wellbeing B = −0.6298, SE = 0.2196, 95 % CI [−1.0614, −0.1982]. The parasocial relationship with the influencer was a positive moderator of the relationship between wishful identification and viewer wellbeing B = 0.0736, SE = 0.0353, 95 % CI [0.0043, 0.1430], partially supporting H4. Income, out of the three control variables, was the only significant predictor of viewer wellbeing B = 0.1102, SE = 0.0238, 95 % CI [0.0636, 0.1569]. See Figure 5 for detailed results. See Table 3 for a summary of hypotheses-testing results.

Hayes PROCESS Modeling results for product-oriented videos.

Hypotheses-testing results.

| Hypotheses | All videos | Vlogs | Product-oriented videos | Skincare videos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 VE → WI | Supported | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H2 WI → PWB | Supported | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| H3 VE → PWB | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

| H4 PSR × WI → PWB | Rejected | Supported | Rejected | Supported |

| H5 PSR × VE → PWB | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected | Rejected |

-

VE = video enjoyment, WI = wishful identification, PWB = psychological well-being, PSR = parasocial relationship.

5 Discussion

This study is designed with three research purposes: first, to find out how influencers’ videos exert direct and indirect impact on viewer’ well-being; second, to investigate the mediating and moderating roles of wishful identification and parasocial relationship; and third, to clarity the discrepancies of various types of videos in the process of such impact. With influencer-fan data, results indicate that influencers’ videos have a negative and indirect, rather than direct, impact on viewers’ well-being through wishful identification. Parasocial relationship acts as a moderator to lessen such negative impacts. The moderating effect works only for research models on vlog-oriented videos and skincare videos, but not for the research model on product-oriented videos.

This study extends the current understanding of Social Comparison Theory by pointing out that different types of influencer-created videos have varied effects on priming followers’ tendency of engagement in social comparison. Parasocial relationships, traditionally viewed as a mediator in social media influencer research (e.g. Conde and Casais 2023; Lim and Lee 2023), play a crucial role in shaping how followers engage with influencer content. While mediation analysis highlights the indirect impact of influencers’ content on followers’ behavior, studying them as moderators can offer deeper insights. As moderators, parasocial relationships could influence the strength or direction of the relationship between influencer content and audience outcomes, such as trust, purchase intent, or emotional response. Examining parasocial relationships in this capacity allows us to explore how varying degrees of emotional attachment may enhance or diminish the effects of influencer messaging, providing a more nuanced understanding of their impact.

The negative indirect relationship between the enjoyment of influencers’ videos and viewers’ well-being through the mediation of wishful identification indicates that the motivation and intention of watching influencers’ videos play important roles in how viewers psychologically react to influencers’ content. The motivations and effects for social media content consumption vary. Some might actively look for entertainment, information, and company, others might unconsciously compare themselves with people that they saw on social media. If the viewers have the latter intention, it is very likely that they experience negative reactions for the following reasons. First, social media content creation is a selective process. Influencers are not able to capture all the moments of their life to display on social media. Rather, a lot of times, they capture the highlights that are more glamorous or attention-crabbing. This might be due to traffic-driven purposes or simply because those moments are more worthy of posting compared with mundane everyday lives. Second, social media influencers might be naturally more attractive in physical features. In addition, with the empowerment of filters, beautifying cameras, and Photoshop, they might look even more attractive than in real life. Thus, social media contains a higher density of physically more attractive people. Without awareness of this issue, viewers with wishful identification tendencies are more likely to suffer from body shame (Greenwood 2009) and appearance comparison (Prichard et al. 2023).

The parasocial relationship with the collaborated influencer was found as a moderating variable to lessen the negative effects of wishful identification on viewers’ well-being. This means that even with the tendency of “wanting to look like this or live like this”, as long as the viewers consider the influencer as a close friend, they do not experience negative psychological changes. This calls for influencers’ attention to ethical content creation, as the research outcomes prove that relationship-building not only contributes to the economic impact of content creation (Bi and Zhang 2022) but also to the positive psychological well-being of their viewers. The parasocial relationship might also be the key element that separates benevolent envy and malicious envy experienced by the viewers. When dividing the model by video types: vlog-oriented videos, product-oriented videos, and skincare videos, wishful identification derived from skincare videos has the largest negative impact on viewers’ well-being. By frequently showcasing and promoting unrealistic beauty standards, these videos may lead viewers to feel inadequate or dissatisfied with their appearance. The constant exposure to such content can subtly encourage individuals to seek invasive procedures as a solution to perceived imperfections. This normalization of cosmetic surgery may further exacerbate issues related to body image and self-esteem, contributing to a cycle of comparison and pressure to conform to these beauty ideals, thus negatively affecting mental health in the long run. This result is in line with previous research on how influencer-created content regarding plastic surgeries can normalize such procedure among their followers (Hermans et al. 2022). Thus, influencers should maintain higher ethical standards in content creation, especially when recommending skincare and medical procedures. Their content can negatively impact followers’ psychological well-being by promoting unrealistic beauty standards or encouraging risky treatments. Ethical responsibility is important to ensure that the information shared promotes health and safety, rather than exploiting followers’ insecurities for profit.

6 Limitations

This study is by no means perfect. The limitations of the study include the following. First, the study is in collaboration with an influencer who specializes in beauty and fashion. Future researchers are encouraged to test the research model with data collected from influencers in other industries, for example, fitness influencers and opinion leaders providing dietary recommendations. Second, this study relies on cross-sectional data, while it offers additional information to and confirmation of the research model if a longitudinal dataset is recruited. Third, the negative connection between wishful identification and viewer well-being is worth further explanation, future researchers are recommended to dive deeper into the psychological insights within this phenomenon and explore relationships with constructs such as envy and self-esteem.

References

Aslam, Wajeeha, Sadia Mehfooz Khan, Imtiaz Arif & Sohaib Uz Zaman. 2022. Vlogger’s reputation: Connecting trust and perceived usefulness of vloggers’ recommendation with intention to shop online. Journal of Creative Communications 17(1). 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/09732586211048034.Search in Google Scholar

Baek, Young Min, Young Bae & Hyunmi Jang. 2013. Social and parasocial relationships on social network sites and their differential relationships with users’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 16(7). 512–517. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0510.Search in Google Scholar

Baldwin, Matthew & Thomas Mussweiler. 2018. The culture of social comparison. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(39). E9067–E9074. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721555115.Search in Google Scholar

Bakker, Diederich. 2018. Conceptualising influencer marketing. Journal of Emerging Trends in Marketing and Management 1(1). 79–87.Search in Google Scholar

Barari, M. 2023. Unveiling the dark side of influencer marketing: How social media influencers (human vs virtual) diminish followers’ well-being. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 41(8). 1162–1177. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-05-2023-0191.Search in Google Scholar

Berryman, Rachel & Misha Kavka. 2018. Crying on YouTube: Vlogs, self-exposure and the productivity of negative affect. Convergence 24(1). 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736981.Search in Google Scholar

Bond, Bradley J. & Kristin L. Drogos. 2014. Sex on the shore: Wishful identification and parasocial relationships as mediators in the relationship between Jersey shore exposure and emerging adults’ sexual attitudes and behaviors. Media Psychology 17(1). 102–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.872039.Search in Google Scholar

Bi, Nicky Chang & Ruonan Zhang. 2022. “I will buy what my ‘friend’ recommends”: The effects of parasocial relationships, influencer credibility and self-esteem on purchase intentions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17(2). 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrim-08-2021-0214.Search in Google Scholar

Conde, Rita & Beatriz Casais. 2023. Micro, macro and mega-influencers on instagram: The power of persuasion via the parasocial relationship. Journal of Business Research 158. 113708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113708.Search in Google Scholar

Duan, Xu. 2020. “The Big Women”: A textual analysis of Chinese viewers’ perception toward femvertising vlogs. Global Media and China 5(3). 228–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436420934194.Search in Google Scholar

Farivar, S., F. Wang & O. Turel. 2022. Followers’ problematic engagement with influencers on social media: An attachment theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior 133. 107288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107288.Search in Google Scholar

Feijoo, Beatriz, Adela López-Martínez & Patricia Núñez-Gómez. 2022. Body and diet as sales pitches: Spanish teenagers’ perceptions about influencers’ impact on ideal physical appearance. Profesional de la Información/Information Professional 31(4). e310412.10.3145/epi.2022.jul.12Search in Google Scholar

Feilitzen, Cecilia & Olga Linné. 1975. Identifying with television characters. Journal of Communication 25(4). 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1975.tb00638.x.Search in Google Scholar

Fioravanti, Giulia, Andrea Svicher, Giulia Ceragioli, Viola Bruni & Silvia Casale. 2023. Examining the impact of daily exposure to body-positive and fitspiration Instagram content on young women’s mood and body image: An intensive longitudinal study. New Media & Society 25(12). 3266–3288. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211038904.Search in Google Scholar

Gleason, Tracy R., Sally A. Theran & Emily M. Newberg. 2017. Parasocial interactions and relationships in early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology 8. 255. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255.Search in Google Scholar

Greenwood, Dara. 2009. Idealized TV friends and young women’s body concerns. Body Image 6(2). 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Goedhart, Nicole S., Eva Lems, Teun Zuiderent-Jerak, Carina ACM Pittens, Jacqueline E. W. Broerse & Christine Dedding. 2022. Fun, engaging and easily shareable? Exploring the value of co-creating vlogs with citizens from disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Action Research 20(1). 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503211044011.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Jeffrey A. & Dong Liu. 2022. Social media use, social displacement, and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology 46. 101339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101339.Search in Google Scholar

Helgeson, Vicki S. & Kristin D. Mickelson. 1995. Motives for social comparison. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21(11). 1200–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672952111008.Search in Google Scholar

Hermans, Anne-Mette, Sophie C. Boerman & Jolanda Veldhuis. 2022. Follow, filter, filler? Social media usage and cosmetic procedure intention, acceptance, and normalization among young adults. Body Image 43. 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.10.004.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffner, Cynthia A. & Bradley J. Bond. 2022. Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology 45. 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101306.Search in Google Scholar

Hoek, Rhianne W., Esther Rozendaal, Hein T. Van Schie, Eva A. Van Reijmersdal & Moniek Buijzen. 2020. Testing the effectiveness of a disclosure in activating children’s advertising literacy in the context of embedded advertising in vlogs. Frontiers in Psychology 11. 479351. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00451.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Lixia, Qingfei Min, Shengnan Han & Zhiyong Liu. 2020. Understanding followers’ stickiness to digital influencers: The effect of psychological responses. International Journal of Information Management 54. 102169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102169.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, Liezille & Anelisa Kelemi. 2020. Natural hair chronicles of black female vloggers: Influences on their psychological well-being. Journal of Psychology in Africa 30(4). 342–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1796046.Search in Google Scholar

Jarzyna, Carol Laurent. 2021. Parasocial interaction, the COVID-19 quarantine, and digital age media. Hu Arenas 4. 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00156-0.Search in Google Scholar

Katja, Corcoran, Crusius Jan & Thomas Mussweiler. 2011. Social comparison: Motives, standards, and mechanisms. In D. Chadee (ed.), Theories in social psychology, 119–139. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Hyung-Min, Minseong Kim & Inje Cho. 2023. Home-based workouts in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: The influence of fitness YouTubers’ attributes on intentions to exercise. Internet Research 33(3). 1157–1178. https://doi.org/10.1108/intr-03-2021-0179.Search in Google Scholar

Lim, R. E. & S. Y. Lee. 2023. “You are a virtual influencer!”: Understanding the impact of origin disclosure and emotional narratives on parasocial relationships and virtual influencer credibility. Computers in Human Behavior 148. 107897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107897.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Hsiao-Han, Ching-Fu Chen & Yi-Wen Tai. 2024. Exploring the roles of vlogger characteristics and video attributes on followers’ value perceptions and behavioral intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 77. 103686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103686.Search in Google Scholar

Moyer-Gusé, Emily. 2008. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory 18(3). 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x.Search in Google Scholar

Mundel, Juan, Anan Wan & Jing Yang. 2023. Processes underlying social comparison with influencers and subsequent impulsive buying: The roles of social anxiety and social media addiction. Journal of Marketing Communications 30(7). 834–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2023.2183426.Search in Google Scholar

Notonegoro, Raya & Daniel Tumpal Hamonangan Aruan. 2024. From screen to shopping cart: The effect of congruence, wishful identification, and source credibility on live streaming shopping in Indonesia. Jurnal Manajemen dan Pemasaran Jasa 17(1). 169–186. https://doi.org/10.25105/v17i1.18994.Search in Google Scholar

O’Hagan, Louise, Hannah Barton & Andrew Power. 2018. Cybertrends: An exploratory study of why individuals conform on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology and society, 79–89. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315160962-7Search in Google Scholar

Ovard Johnson, Sarah. 2020. Social media conformity and self esteem among college students. https://scholar.dominican.edu/scw/SCW2020/conference-presentations/67/ (accessed May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Pan, Wenjing, Zhe Mu & Zheng Tang. 2022. Social media influencer viewing and intentions to change appearance: A large scale cross-sectional survey on female social media users in China. Frontiers in Psychology 13. 846390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846390.Search in Google Scholar

Prichard, Ivanka, Brydie Taylor & Marika Tiggemann. 2023. Comparing and self-objectifying: The effect of sexualized imagery posted by Instagram Influencers on women’s body image. Body Image 46. 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.07.002.Search in Google Scholar

Quelhas-Brito, Pedro, Amélia Brandão, Mahesh Gadekar & Sofia Castelo Branco. 2020. Diffusing fashion information by social media fashion influencers: Understanding antecedents and consequences. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 24(2). 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfmm-09-2019-0214.Search in Google Scholar

Rosaen, Sarah & Jayson Dibble. 2016. Clarifying the role of attachment and social compensation on parasocial relationships with television characters. Communication Studies 67(2). 147–162.10.1080/10510974.2015.1121898Search in Google Scholar

Schmuck, Desirée. 2021. Following social media influencers in early adolescence: Fear of missing out, social well-being and supportive communication with parents. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 26(5). 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab008.Search in Google Scholar

Schouten, Alexander P., Loes Janssen & Maegan Verspaget. 2021. Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. Leveraged marketing communications, 208–231. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003155249-12Search in Google Scholar

Seekis, Veya, Graham L. Bradley & Amanda L. Duffy. 2020. Appearance-related social networking sites and body image in young women: Testing an objectification-social comparison model. Psychology of Women Quarterly 44(3). 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684320920826.Search in Google Scholar

Suls, Jerry, Rene Martin & Ladd Wheeler. 2002. Social comparison: Why, with whom, and with what effect? Current Directions in Psychological Science 11(5). 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00191.Search in Google Scholar

Tennant, Ruth, Louise Hiller, Ruth Fishwick, Stephen Platt, Stephen Joseph, Weich Scott, Jane Parkinson, Jenny Secker & Sarah Stewart-Brown. 2007. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 5. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.Search in Google Scholar

Tolbert, Amanda N. & Kristin L. Drogos. 2019. Tweens’ wishful identification and parasocial relationships with YouTubers. Frontiers in Psychology 10. 2781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02781.Search in Google Scholar

Tran, Alison, Robert Rosales & Lynn Copes. 2020. Paint a better mood? Effects of makeup use on YouTube beauty influencers’ self-esteem. Sage Open 10(2). 2158244020933591. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020933591.Search in Google Scholar

van Drimmelen, Manon. 2023. Fitfluencers on GymTok : The effect of fitfluencers’ content on body satisfaction and intention to exercise, and the role of social comparison and wishful identification [Dissertation, Tilburg University. Communication and Cognition]. In Master thesis; Degree granted by Tilburg University. TSHD. Communication and Cognition; Supervisor(s): I.I.M. Vanwesenbeeck, 99. Available at: http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=161566.Search in Google Scholar

Vasconcelos, Liliana & Orlando Lima Rua. 2021. Personal branding on social media: The role of influencers. E–Revista de Estudos Interculturais 3(9). https://doi.org/10.34630/EREI.V3I9.4232.Search in Google Scholar

Yoo, Jaeheung, Saesol Choi, Munkee Choi & Jaejeung Rho. 2014. Why people use Twitter: Social conformity and social value perspectives. Online Information Review 38(2). 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-11-2012-0210.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Xiaoxiao, Wuchang Zhu, Shaojing Sun & Jingxi Chen. 2021. Does influencer popularity actually matter? An experimental investigation of the effect of influencers on body satisfaction and mood among young Chinese females: The case of RED (Xiaohongshu). Frontiers in Psychology 12. 756010. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.756010.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Emotions, society, and influencers in the digital era

- Research Articles

- Influencing eating choices, manipulating emotions, & the influencer: an ethnography

- Emotions of food influencers regarding digital work and the transmission of food knowledge on Instagram

- What makes a super influencer? Testing the origin of fame theory in China

- “How come I don’t look like that”: the negative impact of wishful identification with influencers on follower Well-being

- Mexican queer influencers: corporeal-emotional social reconfigurations

- Social media influencers and followers’ loneliness: the mediating roles of parasocial relationship, sense of belonging, and social support

- Content creators as social influencers: predicting online video posting behaviors

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Emotions, society, and influencers in the digital era

- Research Articles

- Influencing eating choices, manipulating emotions, & the influencer: an ethnography

- Emotions of food influencers regarding digital work and the transmission of food knowledge on Instagram

- What makes a super influencer? Testing the origin of fame theory in China

- “How come I don’t look like that”: the negative impact of wishful identification with influencers on follower Well-being

- Mexican queer influencers: corporeal-emotional social reconfigurations

- Social media influencers and followers’ loneliness: the mediating roles of parasocial relationship, sense of belonging, and social support

- Content creators as social influencers: predicting online video posting behaviors