Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a significant social and public health issue with far-reaching consequences for individuals, their families, workplaces, and society. Despite its impact, the effects of IPV on victims’ work environments remain underexplored. This study aimed to review empirical evidence on how IPV affects the health and wellbeing of employed men and women, their working lives, and their work environments, as well as the types of support employers provide in OECD countries.

Methods

A descriptive systematic review was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO to identify empirical studies examining the impact of IPV on employees’ health, working lives, and the workplace environment. Twenty-two empirical articles, published between 2014 and 2025, met the inclusion criteria. These criteria specified that the studies must address IPV experienced in the home and its effects on the victim’s working life, workplace environment, and overall health and wellbeing. Furthermore, the studies were required to consider the support and assistance provided by employers to employees affected by IPV.

Conclusion

The findings indicate that IPV is widespread, with a higher reported prevalence among female employees. Victims – both male and female – experienced various forms of abuse, including physical, psychological, sexual, and digital violence, resulting in injuries, stress, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. IPV also had a detrimental impact on victims’ work environments, often leaving them emotionally exhausted and unable to sustain performance levels, which in turn led to the redistribution of their workload among colleagues. Moreover, IPV disrupted victims’ working lives by undermining career identity, damaging professional reputations, restricting opportunities for career advancement, and necessitating extended periods of sick leave – ultimately hindering their ability to establish robust employment careers, secure references, and maintain professional credibility. Support from employers varies both across and within countries, ranging from legal protections and workplace policies to human resources guidance, safety planning, counselling, and flexible working arrangements.

1 Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious social and public health issue that causes physical and psychological suffering for individuals and families and has broader negative impacts on society. Approximately 27% of women aged 15–49 worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence in a close relationship at some point in their lives. The extent of IPV from a global perspective varies across countries, with women in low-income countries being particularly affected [1]. There are no global statistics on men’s exposure to IPV. However, it is estimated that one in ten men in the United States will be psychologically or sexually abused by someone in an intimate relationship at some point in their lives [2]. In Sweden, a survey found that 20% of women and 10% of men were estimated to have been exposed to IPV in adulthood [3]. This means that many people have met or worked with someone during their working life who is, or has been, a victim of IPV. No legislation compels employers to investigate whether an employee is exposed to violence in a close relationship. Yet it is important from a work environment perspective that managers, occupational health services, and human resources (HR) actively ask about exposure to violence and have preparedness and are coordinated on how to support employees who are exposed to IPV at home or in the workplace [4].

IPV is defined as interpersonal violence directed at individuals, which refers to behaviours within an intimate relationship that result in physical, psychological, or sexual harm. It includes acts, such as physical aggression, psychological abuse, sexual coercion, or controlling behaviours, involves violence by either a current or a former partner [5], and consists of acts of violence that escalate and become more severe over time. As violence often occurs at home, it can be difficult for outsiders to detect [6].

A Mexican study, for instance [7], investigated the extent and nature of Mexican men’s work-related violence against their partners. The study consisted of 100 men who were part of an intervention programme for perpetrators of violence. Forty-two per cent of the sample reported fighting with their partners/ex-partners on the phone while they were at work. More than a quarter reported work-related violent behaviours that involved interfering with their partner’s ability to go to work. Of the sample, 27% disturbed their partner’s sleep and 25% told their female partner to quit their job or to reduce their working hours to be at home. The study did not show that the women stopped working because of their partner. However, 52% of the men answered “yes” when asked if they had engaged in work-related interference with their partner, indicating that a significant proportion of men in the study admitted using certain behaviours or tactics that interfered with or affected their partner’s ability to work [7].

The impact of IPV in workplaces in low- and middle-income countries was examined involving a total of 16,921 male and female employees from 257 companies in Ghana, South Sudan, Bolivia, and Paraguay [8]. The study found that all companies surveyed had some employees who were victims of IPV, with the consequences affecting both victims and perpetrators. Consequences included absenteeism, delays, and factors that affected employees’ work performance, which in turn led to production loss and economic costs for businesses. These findings highlight the need for governments, businesses, and communities to address IPV [8]. Another study evaluated the impact of a 10-month workplace intervention in a garment factory in India. The aim was to promote gender equality, with a focus on IPV against women as part of the intervention. Several tools were used, including information displays, leaflets, and information from experts in the field. Results showed that after 12 months, men and women from the intervention group expressed more gender-equal attitudes and were less likely to report acceptance of violence in their intimate relationships. Participants also had increased knowledge of domestic violence support services compared with the control group. The authors did not ask about participants’ experiences of IPV, so it was not possible to conclude how many of those who participated had experienced IPV themselves. Notwithstanding, the study found that the intervention was equally effective for men and women in gaining knowledge about IPV and gender-equal attitudes [9].

In the Philippines [10], a study examined the role of organisational support for employees who experienced IPV, whether at home or in the workplace. The study did not elaborate on the type of support offered by employers. However, it found that when employees who had experienced IPV themselves were supported by their workplaces, they found it easier to cope with the negative work-related consequences of IPV.

It is suggested that victims of IPV suffer multiple negative consequences, such as social isolation and health problems [10]. Some researchers argue that workplaces can play a key role in reducing the impact of IPV and increasing employee safety by providing information and support, and being prepared to respond effectively when employees are affected [11]. As such, there is a need for studies that synthesise the state of knowledge in the field of IPV and working life. Therefore, this study aimed to descriptively review the empirical evidence on the effects of IPV on the health and wellbeing of employed men and women, and their working life and work environment, as well as to identify what type of support employers give to their employees. The following research questions were addressed:

RQ1: What is the prevalence of domestic violence among working women and men in OECD countries?

RQ2: What are the consequences of domestic violence for the working environment and the health and wellbeing of employed victims?

RQ3: What help and support do employers offer to workers who are victims of IPV?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

A descriptive systematic review design was utilised in this study.

2.2 Search strategy

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in the databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO, beginning on March 24, 2024, and updated through March 2025. The search strategy included key terms related to IPV, workplace factors, health outcomes, and organisational responses. Specifically, the searches combined keywords such as “IPV,” “domestic violence,” “partner abuse,” and “intimate partner aggression” with terms like “consequences,” “effects,” “outcomes,” “impact,” “repercussion,” and “costs.” These were further combined with workplace-related terms, including “employ,” “working life,” “work conditions,” “workplace,” and “work environment,” along with terms describing the workforce, such as “employee,” “worker,” “staff,” and “personnel.” Health-related keywords included “mental health,” “physical health,” “wellbeing,” and “health outcome.” Additionally, organisational terms such as “place of work,” “organisation,” “company,” and “workplace” were incorporated, as well as terms relating to responses and policies like “policy,” “intervention,” “prevention,” “guidelines,” “assistance,” “support,” and “response.” Boolean operators were applied to combine these keywords effectively to maximise relevant search results while avoiding duplication and irrelevant records. The search terms were carefully reviewed to ensure clarity and comprehensiveness across all databases.

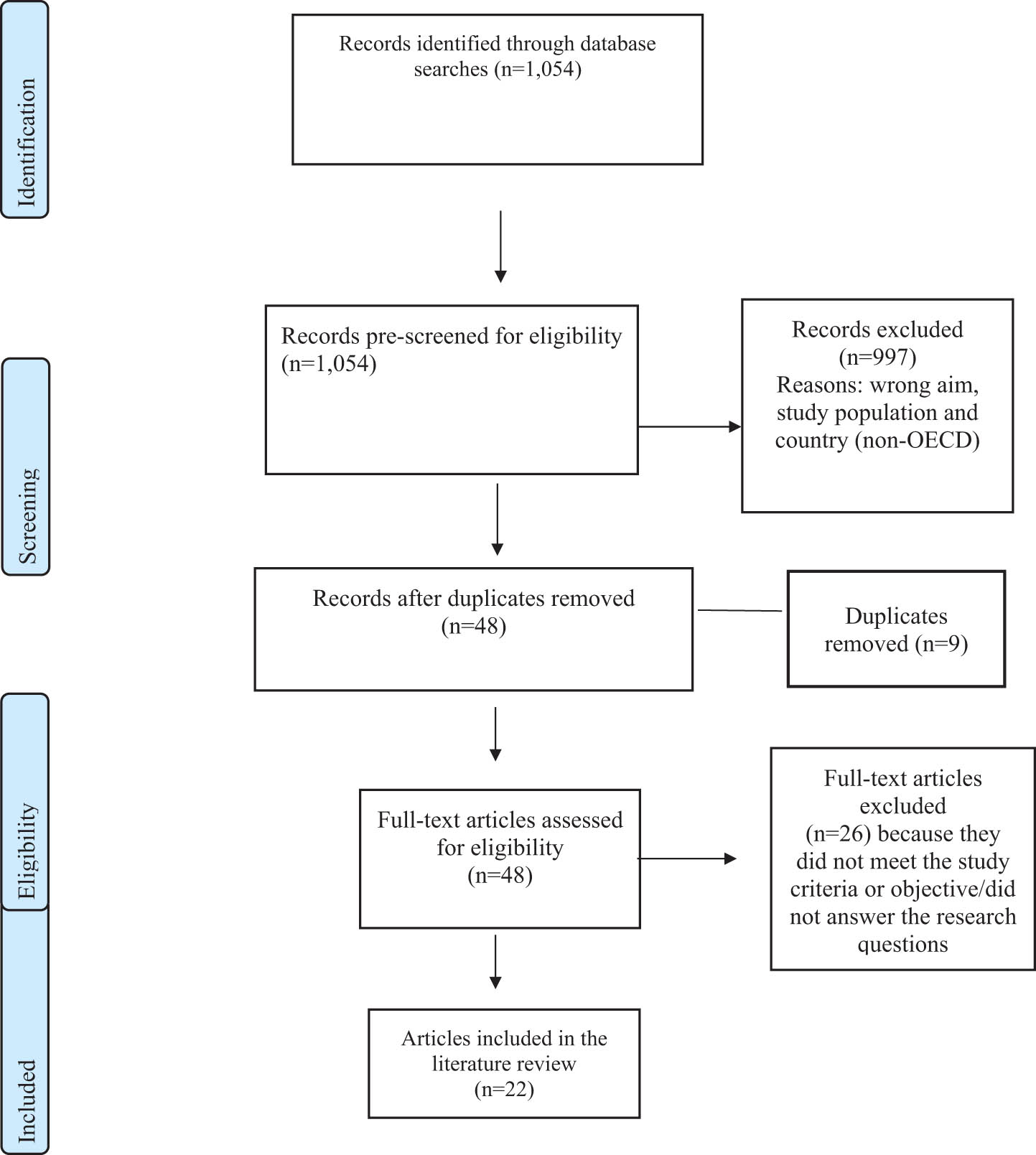

All search combinations were generated for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries as a whole and for individual OECD member countries. The review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. The PRISMA flowchart is presented in Figure 1. The eligibility criteria included peer-reviewed articles conducted in OECD countries, written in English, and published between 2014 and 2025. Participants in the study had to be working men or women and 18 years and older. The studies had to be about IPV and its impact on health, wellbeing, working life and the work environment, or the support and help offered by employers when employees are subjected to IPV. Articles were excluded if they were literature reviews, not peer-reviewed, published before 2014, conducted in non-OECD countries, or not written in English, and if the study participants were younger than 18 years or not in gainful employment. Studies were also excluded if they pertained to violence between biological family members, or if they dealt with support other than from employers.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of the screening process and selection of the included articles.

2.3 Article selection and assessment

A total of 1,054 articles were identified in all databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO) and were pre-screened for eligibility. Of the 1,054 articles, 997 were excluded because they were not conducted in OECD countries, or because the target population was younger than 18 years, or the articles did not address the work or health consequences of IPV for employed individuals. Articles pertaining to workplace violence between colleagues were also excluded. The remaining 57 articles were retrieved and exported to Zotero for screening, and nine duplicates were removed. In total, 48 articles were carefully read in full text, and 26 were excluded because they did not sufficiently address the study’s purpose and answer the research questions.

Altogether 22 articles remained and were included in the literature review (see Figure 1). The first and last authors (V.F. and G.M.) worked independently to select the studies, based on the title and abstract, for potential eligibility, according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Any disagreement among the evaluators was discussed and resolved by consensus with the second author (J.S.). The authors worked independently during the data extraction from the selected studies. The authors used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist to evaluate the quality of the studies [13] (see Table S1, Supplementary file).

3 Results

A total of 1,054 articles were retrieved, of which 997 were excluded as they did not meet the previously stated inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 57 articles screened, only 22, published between 2014 and 2025, were included in the descriptive review. The majority of the reviewed studies (n = 14) were conducted in the United States [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Three were conducted in Australia [29,30,31], two in Canada [11,31], two in New Zealand [30,32], and one in the United Kingdom [33]. One study was conducted across two countries – the United States and Canada – and included data from both [34]. Geographically, most studies originated from the Americas (United States and Canada), with two from Australasia (New Zealand) and one from Europe (United Kingdom). Of the included studies, 12 employed quantitative methods [14,15,17,21,22,23,24,25,27,28,30,34], 5 used qualitative methods [18,19,20,31,32], and 5 adopted a mixed-methods approach [11,16,26,29,33]. Sample sizes ranged from 4 participants [20] to 3,854 [27] (Table 1).

Studies included in the review

| Author(s), year/country | Aim | Sample/methods | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blodgett and Lanigan, 2018/USA [14] | To investigate the prevalence and consequences of IPV in the workplace in US companies | Quantitative survey, convenience sample consisting of employees from 32 different companies (n = 1,390). Two-thirds were women. Descriptive statistics, chi-square test, and logistic regression analysis | Over half of the women and a quarter of the men reported experiencing IPV at some point in their lives. A total of 16% of participants reported having experienced IPV in the past 12 months. Women with a history of violence were at higher risk of experiencing violence in a close relationship, with the highest risk group being women with a history of physical or sexual abuse in childhood. The same women reported missing workdays, experience work delays, and the perpetrator showed up at their workplace |

| Laharnar et al., 2015/USA [19] | To examine the implementation and use of Oregon’s IPV employee leave law | Qualitative semi-structured interviews on a sample of Oregon government managers of employees who had experienced IPV in the past year (n = 10) and Oregon government employees who reported having experienced IPV in the past year (n = 17) | The effects of IPV on victims’ work and the workplace were reported. Of the participants, 93% reported positive reactions when disclosing IPV exposure, while 52% reported negative reactions (lack of information, confidentiality, and support) from managers. Three years after implementation, 74% of participants were unaware that the law existed, and 65% of those exposed to IPV would have benefitted if they had known about the law. Main obstacles to implementation: managers were uneducated about IPV and the meaning of the law. Employees had job anxiety and fear of poor pay and stigma. Effective implementation and support of the law were needed to avoid negative consequences for IPV sufferers and the entire workplace. The authors concluded that there was a need for increased awareness of IPV in the workplace and for supervisor training |

| Thematic analysis | |||

| Showalter and McCloskey, 2021/USA [26] | To examine the experiences of work instability of IPV victims, and their experiences of workplace disruptions, including disruptions through technology. In addition, the study sought to establish what formal employer policies IPV victims were aware of, and which workplace support they perceived as helpful or harmful | Data from a mixed-method study. Qualitative cross-sectional study and semi-structured interviews | Survivors of IPV risked losing their only source of independence from their abusive partner when they were unable to go to work, or needed to take unpaid leave because of their experiences of violence. Workplace policies that supported IPV victims and prevented them from missing paid work hours or losing their jobs were crucial to the long-term wellbeing of these women and their families |

| Sample: women ≥18 years old who were exposed to IPV and received support from a social service in the Midwestern United States in 2017–2018 (n = 19). Analysis: narrative method and constant comparative analysis, through grounded theory | |||

| Reibling et al., 2020/USA [25] | To describe physicians’ own experiences as victims of IPV from a current or former partner and identify the nature and conditions of violence associated with their experiences | Survey administered to four groups of medical professionals in the United States between 2015 and 2016 (n = 400; 175 women and 225 men) | IPV was reported by 24% of respondents, with the most common forms of violence being verbal, physical, sexual, or stalking. The violence was most common among older participants (66–89 years), those who had experienced childhood abuse, worked less than full-time, and those who had been diagnosed with personality disorders. Women and Asian Americans reported a slightly higher occurrence of IPV than the rest of the respondents |

| Data was analysed through chi-square comparison test and logistic regression analysis | |||

| Pachner et al., 2022/USA [24] | To examine the relationship between IPV workplace disruptions and workplace support, comparing Black and White women. The study also examined what type of workplace support had a significant effect on IPV workplace disruptions, and what helped victims maintain their employment | Cross-sectional quantitative survey (n = 39 women total; 19 White and 20 Black) conducted both online and on-site with the researcher. Women ≥18 years who had been employed at some point during their experiences of IPV but who had not experienced cyberstalking on the online platform used by some respondents | Black and White women received different types of support and responses from colleagues and managers when experiencing IPV. Black women tended to receive support for single workplace disruptions, while white women received more varied help and support for multiple disruptions. Fundamental support systems had a protective effect on victims’ work outcomes |

| Bivariate analysis | |||

| Carrington and Williamson, 2022/New Zealand [32] | To describe the Domestic Violence Workplace (DVFREE) programme based on the specific context of New Zealand, and to provide practical recommendations on how and why employers can support employees experiencing domestic violence | Two case studies (one training 470 managers in using the DVFREE protocol; the other an in-person family violence awareness project for 3,800 employees) illustrating two concrete examples of how DVFREE was implemented and worked in practice. The studies describe how DVFREE has impacted workplaces and employees exposed to IPV | DVFREE is described as a structured and useful programme. Recommendations include that participants were aware of risk factors and provided guidance to employees on relevant questions to ask to understand the employees’ situation, such as warning signs of risk of deadly violence. Understanding employees who were exposed to violence and their conflicting feelings about whether or not to receive help was part of the process. The study highlights the importance of respecting employee confidentiality and clearly defining the boundaries |

| Kumar and Casey, 2017/USA [18] | To examine how women contrast IPV with their work, where they access resources, rediscover their self-esteem, experience success, and make changes in their personal lives | Qualitative in-depth interviews with middle-class American women aged ≥ 25, who had left an abusive relationship over 5 years previously and who had held a full-time job for over a year at the time they left the violent relationship (n = 10). Ricoeur’s data analysis | Work played a crucial role in enabling women to begin the process of empowerment. By highlighting the interdependence and positive effects of work on personal issues, social workers and human resource professionals can create interventions with long-term benefits. There was a complex relationship between women’s exposure to IPV and their tolerance of abusive work relationships. This dynamic could worsen their experiences of violence, as the employer’s control over them mirrored the dynamics of the abusive relationship, binding them to the organisation in a similar way (as in their abusive relationships) |

| Maskin et al., 2019/USA [22] | To examine gender-based associations between different types of exposure to IPV (physical, psychological, and sexual violence) and employee market outcomes (absence, sick leave, and job satisfaction) among male and female post-9/11 veterans | Quantitative design, web-based survey consisting of data on male and female post-9/11 veterans (n = 407) who had been exposed to IPV in the past 6 months, 52% of whom were women. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis | Sexual violence was significantly associated with absenteeism and sick leave for women, but not for men. Physical violence was significantly associated with sick leave for men, but not for women. Regarding psychological violence, there was a marginal association with absenteeism and job satisfaction, regardless of gender. All types of IPV measured in the study (psychological, physical, and sexual) had a significant impact on both women’s and men’s overall workability. The results indicated the need for targeted workplace interventions to support men and women exposed to IPV |

| Kulkarni and Ross, 2016/USA [16] | To examine employees’ disclosures of IPV in the workplace, including whom they tended to disclose the violence to as well as their experiences of workplace support and response | Mixed method – web survey, open and closed questions | Approximately one in five employees reported exposure to IPV during their working life. When an employee was exposed to IPV, they were more than twice as likely to tell their colleagues about the violence than to tell a manager or the HR department. Twenty percent of employees experienced unhelpful reactions from the workplace. To address IPV throughout the organisation, all employees need to receive information and training about IPV and support in the event of exposure to violence, and clear IPV policies need to be in place in the workplace. It is important to promote an organisational culture that supports employees exposed to IPV to access important resources, and that promotes employee safety/productivity |

| Female and male employees of a large company in the south-eastern United States (n = 535). Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics; qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis | |||

| Fitz-Gibbon et al., 2023/Australia [29] | To examine employees’ experiences of workplace support in relation to exposure to IPV. The study examines IPV victims’ perspectives on the 2018 Leave Act and highlights important aspects to consider before implementing the new legislation on paid leave that will be introduced in 2022 | Mixed method, web survey with open and closed questions and semi-structured interviews. Employed women and men 18 years and older (n = 302); 92% women. Interviews: n = 42 | The IPV leave provision has a functional and symbolic role that demonstrates that the workplace has a responsibility to support employees who are exposed to IPV. The paid leave law sends a message about victims’ need for financial support, both during and after a violent incident. It also reduces shame and anxiety among employees in the workplace |

| Thematic analysis and quasi-statistics | Findings indicated that, for the IPV leave law to be effective, workplaces need to have organisational cultures that are supportive, not oppressive. However, workplaces with little understanding of IPV, that require their employees to provide documentation to access the leave, risk missing the point of the law | ||

| Giesbrecht, 2022/Canada [11] | To investigate how workplaces were affected when employees experienced IPV | Mixed method web-based survey with open and closed questions, focus groups and interviews with employees (n = 437; 81% women) in Saskatchewan, Canada | The prevalence of IPV was widespread among the employees included in the study. Half of all respondents stated that they had experienced IPV; 83% of these reported that the violence affected them at work in at least one way. For some, the consequences of the violence resulted in losing their jobs. Others stated that they had been subjected to various forms of violence by a former or current partner. Some respondents, though reporting that they experienced IPV, did not identify themselves as victims, which indicates the need for increased knowledge and understanding in society about what IPV actually means |

| Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis | |||

| Giesbrecht, 2022/Canada [31] | To examine how IPV affects workplaces, and to provide suggestions for workplace support. The following workplaces were included: non-profit municipal organisations, health and medical authorities, labour unions, post-secondary schools, agriculture, finance, public safety, anti-violence agencies, and newly arrived people and organisations for newly arrived people | Qualitative design (focus group interviews and individual interviews) with victims of IPV, employees, managers, and unionised HR staff (n = 27) | The study had three themes: the effects of IPV in the workplace, workplace interventions, and suggestions for IPV policies for organisations. There was a need for workplace training and information for employees to recognise IPV and know where (and whom) to turn to. Organisational policies regarding IPV were important in providing clear guidance on the roles and responsibilities of managers, employers, and employees, both for those experiencing IPV and for the employees. Having a clear direction increased trust between colleagues and their willingness to help each other when signs of IPV were detected in the workplace |

| Employees from anti-violence organisations | Thematic analysis | ||

| Chan-Serafin et al., 2023 Australia [30] | To examine the extent to which organizations applied HR practices to support employees exposed to IPV | Quantitative study of Australian HR consisting of HR professionals and line managers (n = 414); and an archival study based on 2 years of data from the WGEA on 4,186 Australian organisations | Organisations with female leaders were more likely to adopt IPV-related HR practices compared with organisations led by men. Female leaders were more likely to support and implement practices related to IPV. This was linked to expectations and gender roles. The authors argued that organisations need to consider the gender of their leadership when implementing HR practices to support employees exposed to IPV. Also, they said that, by implementing HR practices linked to IPV, workplaces could help reduce the effects of IPV on employee wellbeing, career development, and job performance |

| Data analysis included descriptive statistics and zero-order correlation measures | |||

| Leblanc et al., 2014/USA and Canada [34] | To investigate the effects of physical and psychological violence in close relationships on women’s work performance | Study 1: Quantitative web-based survey of full-time employed women not exposed to IPV and living with their partner, and battered women who had worked full-time for at least 6 months and had lived with their partner while employed (n = 50) | Aggression from an intimate partner was related to withdrawal from work. Women who were physically abused reported greater consequences for their work than non-abused women. There was an association between physical aggression from a partner and cognitive distraction, partial absence, and intention to quit the job |

| Descriptive statistics, intercorrelation and reliability coefficients | |||

| Study 2: Quantitative web-based survey of women who had had a job in the past 6 months while living with a partner, or who had had a long-term relationship with a partner (n = 249). Descriptive statistics, intercorrelation and reliability coefficients | |||

| Kulkarni et al., 2018/USA [17] | To investigate how IPV in the work environment affects employees’ health-related quality of life, with a particular focus on gender differences | Quantitative web survey. Employees from a large company in the south-western United States – managers and frontline staff (n = 535); 57% of the sample were women | Female employees reported almost threefold poorer health-related quality of life compared with male employees. In addition, 14% of the sample had experienced one or more violent behaviours from their partner related to being restricted and/or disturbed at work |

| Linear regression analysis | |||

| Branicki et al., 2023/Australia [28] | To examine how listed companies in Australia manage IPV through programmes, policies and initiatives that support employees who experience IPV | Longitudinal quantitative study | There was greater responsiveness to IPV among large companies, with a higher proportion of female middle managers. Companies with more financial resources had more advanced conversations with employees about gender issues. While most companies had some high-level policy commitment and offered some form of assistance to employees experiencing IPV, relatively few companies had deeper IPV commitments, or resources that went beyond unpaid leave and flexible working hours |

| Data collection through the Australian WGEA database and Thomson-Reuters datastream. The data include policies and procedures of 191 Australian listed companies between 2016 and 2019, which together employ 1.5 million employees | |||

| Descriptive and regression analysis | |||

| Lantrip et al., 2015/USA [20] | To examine the effects of IPV on several aspects of women’s career development over time. In the study, the concept of career development encompassed the process by which women shape and change their professional identities, career choices, and work experiences over time | Multiple case studies, semi-structured in-depth individual interviews. Each participant was interviewed on three occasions | Living in a violent relationship was disruptive and affected the women’s career development in several ways, with IPV having a negative impact in the following areas: career planning, daily work activities, career identity, professional reputation, and opportunities for career development. Career identity relates to how women perceived their place and role in their professional lives over time, with long-term goals and ambitions. The women’s professional identity had to do with how the women identified with their profession or occupation, knowledge and values linked to a specific professional role. The abuse continued to affect the women’s physical and mental health as well as financial stability and support networks, which affected their careers over time |

| Interviews with staff at sheltered housing and review of written reflections from the women’s journals. Purposive sampling consisting of women aged ≥ 45 with experience of exposure to physical and psychological violence (n = 4) | |||

| Data were analysed using content analysis | |||

| Marçal et al., 2023/USA [21] | To examine how three state-level policy protections (the right to reasonable accommodation, confidentiality, and protection against dismissal for workplace disruption) are related to IPV. The study examined whether the policy protections are associated with increased employment and housing stability among a sample of mothers with exposure to IPV | Quantitative cross-sectional study (n = 1,296). State labour force data (for 37 US states) were compiled and merged with Fragile Families data to establish which mothers lived in states providing the policy coverage addressed in the study | All three policy protections were associated with increased likelihood of having a job, while none of them were related to increasing women’s opportunities to obtain housing |

| Multilevel regression analysis | |||

| Isola et al., 2023/USA [15] | To examine the relationship between IPV, absence from work as a result of partner interference in the victim’s work, and family-supportive supervision at work | Quantitative web-based survey of female participants living with a partner in a long-term or marital relationship, with a full-time job (n = 249) | Women exposed to IPV whose partners interfered with their work had less absence from work when they received family support guidance at work |

| Descriptive statistics, intercorrelation measures, scale reliability | Organisations have a unique opportunity to reduce the negative effects of IPV, not only for IPV victims but also for other employees who are indirectly affected. Organisations have a legal, ethical, and practical responsibility to create a work environment that is safe for their employees | ||

| Sheridan et al., 2019/UK [33] | To investigate and compare 49 cases of stalking that began in the workplace and 92 cases of stalking that began elsewhere and spread to the workplace | Mixed method: Web survey, including open and closed questions. Sample of employed men and women with experience of being stalked (n = 141). Of the sample, 87% were women, 12% men, and 1% transsexual | Stalking had consequences for both victims and workplaces, when stalking occurred in the workplace; everything from discomfort to exposure to sexual and physical abuse, and career interruption was reported. A small proportion of participants reported the stalking to their managers, with only half of them being satisfied with the response/help they received |

| Bivariate analysis | |||

| Showalter et al., 2024/USA [27] | To examine the protective effect, in IPV, of confidentiality and leave policies in the workplace for mothers | Quantitative longitudinal cohort study | Workplace policies included flexible leave or the ability to take time off work to manage IPV (e.g., to attend court hearings, safety planning, and medical care). Employees benefitted from confidentiality policies because the employer valued their privacy, thus limiting workplace gossip. Supportive workplace policies were effective in reducing the consequences of IPV |

| Women exposed to IPV and employed mothers (n = 1,893) | |||

| Mixed group of employed and unemployed mothers (n = 1,961) | |||

| Descriptive statistics, linear regression | |||

| LeBlanc et al., 2014/USA [23] | To evaluate the effectiveness of the RRR training programme aimed at improving employees’ and employers’ knowledge and skills related to IPV. The study also aimed to assess whether the training increased participants’ ability to recognise signs of IPV, respond effectively by helping victims, and refer those in need to help | Quantitative pre-post study (n = 157) | The RRR training led to an increased knowledge of IPV among participants. The majority of participants reported that the training led to an improved ability to refer employees and provide them with information about IPV and refer those in need to the local authorities. The training was effective in immediately promoting and strengthening employers’ and employees’ knowledge about, and ability to recognise and respond to IPV in the workplace |

| The sample consisted of employees and employers from different companies (aviation, general business, health care, social services) who had undergone RRR training at their workplace for 1 year | The study concluded that Interventions delivered at the community level in the socio-ecological framework (e.g., workplaces) are important for achieving social change and counteracting IPV | ||

| Bivariate analysis |

DVFREE, Domestic Violence Workplace; HR, human resources/human resources (department); IPV, intimate partner violence; RRR, Recognize, Respond, Refer (training programme); WGEA, Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

The included studies employed varying research designs and sample sizes, leading to differences in how the prevalence of IPV among employed men and women was measured and reported. As a result, the findings indicated a wide range of IPV prevalence across sexes. One study that included both women and men found that over half of the female participants and a quarter of the male participants had experienced IPV at some point in their lives. Among the 1,390 participants, 74 women and 14 men reported experiencing IPV within the past 12 months. Furthermore, 47% of victims reported physical injuries resulting from the violence, with such injuries being more commonly reported by women [14]. Another study conducted in Oregon, USA, involved interviews with 17 female state employees who had experienced IPV in the previous year. Of these, 26% reported feeling threatened or stalked, as their partners or ex-partners harassed them by repeatedly telephoning them at work or physically appearing at their workplace. A separate study from the United States [26] reported that women experienced IPV and workplace disruption through digital abuse perpetrated by partners or ex-partners. Six in ten women reported experiencing workplace stalking by their current or former partners. In another study [25], 24% of 400 respondents reported experiencing IPV. The most frequently reported forms of violence were verbal (15%), physical (8%), sexual (4%), and stalking (4%). Exposure to IPV by current partners was reported by 28.6% of women and 20.4% of men. IPV was found to be most prevalent among participants with a history of childhood abuse, those working less than full-time, or those diagnosed with personality disorders. Gender-based associations between different forms of IPV exposure and employment outcomes were examined in another study, which assessed participants’ absence and attendance at work, as well as job satisfaction in relation to IPV. The authors found that, among 522 respondents, 52% of women and 48% of men reported experiences of violence [20]. A study conducted within a large company in the south-eastern United States reported that, among 535 employed women and men, approximately one in five workers had been exposed to IPV during their working lives. Of those exposed, 85% were women and 21% were men [16].

A Canadian study [11] investigated how workplaces were affected when employees experienced IPV and found that, among 437 participants (89% of whom were women), 83% reported that the violence had impacted their work. This was primarily due to difficulties with concentration or the need to take sick leave because they were too distressed to work. In another study by the same author [31], which involved interviews with employees, managers, and HR personnel, 10 out of 27 respondents – nine women and one man – reported experiencing various forms of IPV, including psychological, physical, sexual, and financial abuse, controlling behaviours, harassment, and stalking. A previously mentioned study involving 535 employees from a large company in the south-eastern United States [16] further explored IPV in the workplace. It found that 14% of participants – predominantly women – had experienced one or more violent behaviours from their partners, specifically restrictive or disruptive behaviours in relation to their work. Examples included partners physically preventing victims from attending work or threatening to force them to leave their jobs. Some victimised women reported that their partners sabotaged their cars, refused to help with childcare, stole keys or money, or refused to provide transport to work. Other forms of interference included lying about the health or safety of the children, pressuring victims to quit their jobs, or coming to the workplace to harass them.

The association between IPV and workplace absenteeism, particularly in cases where the partner interfered with the victim’s employment, was explored in one study involving 249 employed women [15]. Of these, 73% had experienced at least one form of violence (psychological or physical), 68 had experienced both, and one had experienced only psychological violence. The study identified a three-way interaction between IPV, partner interference, and family-supportive supervision in relation to absence frequency. Specifically, IPV victims whose partners interfered with their work exhibited lower absence frequency only when they received high – compared to low – levels of family-supportive supervision. Notably, such supervision was only associated with reduced absence when both IPV and partner interference were present. The authors argued that these findings highlight a unique opportunity for organisations to mitigate the negative effects of IPV and partner interference – not only for the direct victims but also for colleagues who may be indirectly affected [15]. Another study [33], which included 141 employed men and women, found that 40% had been stalked by an ex-partner, with 92% of those reporting that the stalking occurred at their workplace.

In total, seven studies in this review examined the impact of IPV on employees’ health and wellbeing. The mental health consequences reported included nervousness, stress, mental illness, depression, and anxiety [19]. Employed victims also experienced exhaustion, forgetfulness, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [26]. Other reported symptoms included paranoia at work, poor attention to detail, a sense of detachment or lack of focus, difficulty staying awake, and muscle pain [26]. Many victims described feeling constantly tired and lacking concentration, which negatively affected their work performance. Some were emotionally exhausted from trying to remain productive at work while dealing with ongoing abuse [31]. Working women were found to have three times worse health-related quality of life compared to their male colleagues, with reported effects including anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, reduced vitality, physical pain, and elevated stress levels [17]. Depression and PTSD were prevalent among both male and female participants [22]. Additional health problems and chronic conditions were also reported, including daily physical pain from previous injuries, head trauma leading to memory and cognitive impairments, and difficulties focusing – all of which hindered work performance [20].

Both male and female victims reported physical symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, shortness of breath, stomach issues, and reduced sex drive [33]. Some participants indicated that pre-existing conditions – such as asthma or skin irritations – had worsened, and that their use of alcohol, drugs, or tobacco had increased. In the same study, among 92 respondents, 87% reported experiencing depression, sleep disturbances, low self-confidence, isolation, and loneliness. Over half reported panic attacks, trust issues, difficulties with intimacy, suicidal ideation or attempts, and increased use of drugs, cigarettes, or prescription medication. Some also reported disordered eating [33].

Several studies in this review also addressed the consequences of IPV on the broader work environment, particularly in relation to workplace stalking behaviours [14,19,26,33]. Victims reported that IPV incidents occurring in the workplace disrupted their ability to perform their duties. Their working lives were affected when partners followed them to work, waited outside the premises, or monitored their activities. Some partners harassed victims by calling their mobile or office phones repeatedly, or by sending frequent text messages. In some cases, perpetrators sent multiple emails throughout the day or used social media to send unsolicited messages to victims or their colleagues, thereby interfering with workplace productivity [14,19,26,33]. Such behaviours placed not only the victims but also their co-workers at risk, as perpetrators sometimes contacted or even threatened colleagues, creating an unsafe work environment. Business productivity was jeopardised due to increased absenteeism, reduced concentration, and the emotional burden carried by affected employees [14]. Blodgett and Lanigan [14] reported that, in some cases, perpetrators contacted the victim’s supervisors or colleagues in ways that were threatening or humiliating. Other consequences for victims included missing over a week of work due to injury, fear of escalating violence, being physically restrained, or experiencing emotional distress. Managers noted that IPV created challenges in the workplace, including increased workloads due to the need to redistribute the victim’s tasks, and last-minute changes to work schedules when victims had to take sudden leave [19]. Victims often lost work time or became unemployed as a result of their partner’s violent behaviour. Many missed workdays due to physical injuries, emotional distress, or difficulties managing childcare responsibilities. It was also common for victims to arrive late or leave work early. IPV affected their work output, leading to slower performance, reduced motivation, and diminished ambition [26]. Many victims reported feeling anxious about disclosing their situation to colleagues for fear of stigma or altered perceptions. Some also lost job opportunities, which hindered career progression [29].

The impact of violence on victims’ careers was demonstrated across several studies. For example, perpetrators sabotaged victims’ educational opportunities and professional relationships or obstructed their prospects for promotion. Pachner et al. found that IPV diminished victims’ confidence in their ability to work and hindered their capacity to achieve long-term career goals due to lost working days or weeks [24]. The effects of IPV in the workplace frequently led to increased absenteeism or reduced productivity, which employers often perceived as performance issues. Consequently, victims were sometimes subjected to performance reviews, disciplinary procedures, and, in some cases, termination of employment [32].

Many victims were reluctant to seek help from their employers, fearing that disclosure would negatively affect their job performance evaluations or professional credibility. Some chose not to disclose their experiences of IPV at work due to controlling supervisors, hostile colleagues, or oppressive workplace cultures; some women described feeling vulnerable and emotionally tethered to the organisation in ways reminiscent of abusive relationships [18].

Psychological, physical, and sexual abuse reported by victims had a significant impact on the overall work capacity of both women and men. Sexual violence was associated with increased absenteeism among women, but not men, while exposure to psychological violence reduced job satisfaction for both genders [31]. Moreover, IPV was linked to various negative outcomes in victims’ work environments, including impaired concentration and inability to perform to their full potential. It was common for victims to call in sick due to emotional distress, and many feared that colleagues would discover their personal difficulties. Giesbrecht [11] found that some victims left work early or feigned illness because they were too upset to continue working.

The findings indicated that IPV posed significant risks not only to victims but also to their co-workers. Perpetrators sometimes directly threatened victims in the workplace, indirectly affecting colleagues. One study reported cases where perpetrators followed victims to their place of work or to colleagues’ homes, with one incident involving the perpetrator damaging a colleague’s vehicle when they were driving the victim home. Stalking and harassment by current or former partners also disrupted co-workers’ ability to perform their duties and increased their anxiety and fear [31].

Women who experienced physical abuse from their partners were more likely to report work-related impacts than those who did not suffer physical abuse. These women reported high levels of distraction at work, suggesting that stress and emotional strain impaired their focus and productivity. Physical abuse was also associated with increased absenteeism, leaving work early, taking extended breaks, or intentions to leave employment altogether [34]. Victims of IPV frequently experienced a decline in work performance, took sick leave, changed jobs, or lost income due to reduced working hours, job loss, or career changes [33]. Living in an abusive relationship was disruptive and adversely affected female victims’ career development in multiple ways, including career planning, daily work activities, career identity, professional reputation, and access to development opportunities. Perpetrators employed abusive tactics to prevent women from applying for jobs or controlled which applications they submitted. Furthermore, abused women often suffered daily physical pain and head injuries that impaired memory and concentration, complicating their ability to perform certain types of work [20].

Regarding help and support offered by employers to victims of IPV, only 15 studies described the nature of support provided to employees experiencing IPV. Of these, eight were conducted in the United States, four in Australia, and one each in New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The included studies revealed that both the United States and Australia have enacted laws to support employees who are victims of IPV [19]. For example, the Employment Protection Act, implemented in Oregon in 2007, permits employees to take unpaid leave if exposed to IPV. This law applies to employees who are victims themselves or to parents or guardians of a minor child who has experienced violence, sexual assault, criminal harassment, or stalking. Employees working for organisations with more than five employees are entitled to take such leave. The legislation also allows employees to attend counselling, seek medical treatment, or participate in court hearings without fear of losing their jobs. Laharnar et al. [19] examined the implementation and utilisation of Oregon’s IPV leave law from two perspectives: Oregon state employees who had experienced IPV and state managers overseeing such employees. Their findings revealed that three years post-implementation, 74% of participants were unaware of the law’s existence, and 65% of those exposed to IPV would have benefitted had they known about it. The primary barriers to effective implementation related to managers’ lack of education regarding IPV and misunderstanding of the law’s provisions [19]. Other studies reported that employers created flexible working arrangements tailored to victims’ needs, such as modifying schedules, allowing tasks to be completed later, or altering the physical location of work to ensure employee safety [29]. Employers also implemented workplace safety procedures to protect victims from their abusers and informed relevant staff about the victim’s safety requirements [29]. In the United States, employer support for IPV victims included providing safety measures, legal assistance, and access to employee assistance programmes designed to prevent victims from losing paid work hours or their jobs – factors critical to the long-term wellbeing of affected women and their families [26]. Additionally, managers and colleagues were often reported to listen attentively to victims, showing genuine concern [24]. Support strategies included easing workloads, providing information about IPV, offering relationship advice, maintaining confidentiality, asking victims what help they desired, and granting paid time off. However, the same study found disparities in support based on race: Black and White women received different types and levels of assistance. Black women tended to receive support primarily for isolated incidents causing workplace disruption, whereas White women received more comprehensive support addressing multiple disruptions. White women were also more likely to be asked about their wellbeing and offered practical help, such as colleagues taking the initiative to contact counselling services, helplines, or shelters [24].

Workplace interventions aimed at supporting employees exposed to violence included measures such as managers controlling employees’ external phone calls to prevent harassment or threats from partners/ex-partners. Support from managers, HR personnel, or colleagues often involved listening to victims, providing comfort, or assisting with securing alternative housing [18]. Some studies reported managerial provision of counselling or referrals to professional services, alongside staff training on appropriate responses should perpetrators appear at the workplace [31,33]. Importantly, employees often reported feeling trusted by their managers and colleagues. Emotional and practical support from co-workers and managers was also noted among victimised women in the United States [17]. In New Zealand, the “Domestic Violence Free (DVFREE)” programme, run by Shine Aotearoa New Zealand, seeks to help workplaces address IPV. The programme fosters a safe working environment where employees feel supported and encouraged to seek help, thereby promoting a culture of safety, awareness, and support [32]. In Canada, workplace support often involves family-oriented programmes providing access to counselling, therapy, IPV information, and workplace safety planning [31]. However, many workplaces in Canada – including non-profit organisations, healthcare agencies, unions, post-secondary institutions, agriculture, finance, public safety, anti-violence organisations, and newcomer support services – lacked formal IPV policies, and where policies existed, employees were often unaware of them [31]. In Orlando, Florida, the Recognize, Respond, Refer (RRR) programme was developed to mitigate IPV’s workplace consequences. Based on the socio-ecological framework, the programme engaged individuals at multiple levels and trained employers and employees to recognise and respond appropriately to IPV. Evaluated across 157 companies spanning aviation, healthcare, social services, and general operations, the programme increased knowledge of intimate partner abuse, willingness to assist victims, and ability to refer them to essential resources. The evaluation indicated that workplace training can catalyse broader organisational changes [23]. In Australia, a study examining the role of HR in supporting IPV-exposed employees surveyed 414 HR professionals and first-line managers. Counselling (70%), flexible work arrangements (65%), and leave for victims of violence (53%) were the most common practices. However, few organisations offered supervisor training on recognising victims of violence (18%) or supporting victims to disclose IPV at work (15%) [30]. Another study highlighted the importance of family-supportive supervision, a management approach encouraging employees to discuss personal or family issues affecting their work, thereby creating a more supportive work environment [15]. An analysis of 191 publicly traded Australian companies, collectively employing 1.5 million people, revealed that 58% had some policy or formal strategy addressing IPV, while 95% offered some form of support to affected employees. Common supports included paid or unpaid leave and flexible working arrangements. Many workplaces also assisted employees in accessing relevant IPV support services [28].

Regarding legal protections, a study of 37 US states found that 46% offered reasonable accommodation rights, allowing IPV victims to take time off work to address violence-related issues such as medical treatment or legal proceedings. However, definitions of “reasonable accommodation” varied considerably: Oregon required all employers to provide safety information, job relocation, or schedule adjustments, whereas New Hampshire limited accommodations to state employees. Additionally, 19.5% of states had confidentiality policies safeguarding victimised employees’ privacy regarding personal and legal matters, and 32% prohibited employers from terminating employees for IPV-related work disruptions. In North Carolina, for example, employers cannot fire, demote, deny promotion, or discipline employees for taking a reasonable time off to seek help related to IPV [21]. The effectiveness of workplace confidentiality and leave policies in the United States was also studied. Results showed that privacy policies benefitted employees by reducing workplace gossip. Workplaces implementing both privacy and leave policies provided particularly strong protections, correlating with a significant reduction in abuse [27].

4 Discussion

This review aimed to identify the impact of IPV on the work environment, working life, health, and wellbeing of victims across OECD countries. Additionally, it sought to illuminate how employers support and assist employees exposed to domestic violence. The findings indicate that IPV is widespread and affects both male and female employees [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,22,25,33]. Both working men and women are subjected to physical, psychological, and sexual violence [16,25]. In most of the samples studied, women were overrepresented compared with men [11,12,13,14,16,17,18,33]. Women were also described as particularly vulnerable to IPV, with the violence reported to be more physical and severe than that experienced by men [14], consistent with previous findings by other authors [35,36,37]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognises violence against women as a significant global public health issue, which may partly explain the overrepresentation of women in the reviewed samples. Furthermore, this overrepresentation may be attributable to the inclusion of female-dominated organisations in many of the studies [37]. Conversely, some studies found no gender differences in the risk of psychological violence [14] or violence involving stalking behaviours [14,19]. In line with prior research, this review also revealed considerable variation in the extent of IPV reported. Differences in research design, sample size, and measurement methods contributed to disparities in how IPV prevalence among employed men and women was reported. These observations align with earlier studies indicating variability in IPV exposure across research contexts [38]. Possible explanations for these variations include differing definitions of IPV, variations in sampling methods, data collection procedures, temporal perspectives, and analytical techniques. Additionally, the reviewed studies reflected diverse contexts of violence exposure, with some focusing solely on IPV victims, while others included individuals who were both victims and perpetrators.

It is important to note that such methodological differences and definitions of violence may have influenced the variability in reported IPV prevalence. For example, some respondents in the reviewed studies did not self-identify as victims despite reporting multiple experiences of IPV [16]. Previous research suggests that abused women may exhibit greater acceptance of wife beating, potentially indicating that some victims normalise violence or perceive it as a typical aspect of daily life [37]. This could explain why certain participants did not identify as victims despite having experienced partner violence [17]. Similarly, empirical evidence suggests that many male victims struggle to identify themselves as abuse victims at the hands of female partners [38,39,40,41]. While it is not possible to conclusively determine whether this accounts for the lower reported rates of male victimisation in workplaces, it may contribute to underreporting due to societal norms or feelings of shame [38,39,40,41]. The review’s findings further demonstrated that IPV has significant physical and psychological consequences for the health and wellbeing of employed victims. Psychological effects included stress, depression, PTSD, reduced self-confidence, and trust issues [22,33]. Physical symptoms encompassed headaches, sleep deprivation, muscle pain, and gastrointestinal problems [33]. Many victims also experienced shame and guilt for remaining in abusive relationships [18]. Regarding occupational consequences, IPV was associated with constant fatigue, exhaustion, and impaired concentration, negatively affecting work performance [31]. Exposure to IPV has also been linked to increased substance use and suicidal ideation or attempts. These impacts often persist long after the violence ceases, with some victims experiencing enduring cognitive impairment [20]. One study reported that IPV causes both immediate [41] and chronic physical and psychological harm [40,42,43].

The findings suggest that IPV generates emotional exhaustion as victims attempt to maintain work performance while enduring abuse. Victims frequently reported fatigue and difficulties concentrating at work, which could be particularly hazardous in occupations requiring sustained attention. This underscores the health and safety risks IPV poses, not only to individuals but also to colleagues and others within the work environment [31]. Comparable results have been observed previously in Mexico, where abusive men engaged in workplace-related tactics such as threats and physical violence against their partners [7]. Additionally, in a study carried out in India, many perpetrators prevented their partners from attending work, emotionally traumatised them during work hours, or harassed them via phone calls while they were at work [9].

Several employees, predominantly women, reported violence directly targeting their work lives. For instance, partners sabotaged vehicles, stole keys or money, refused transport to work, or physically followed victims to their workplace, monitoring and harassing them via text messages or social media. In some cases, abusers contacted workplace managers or colleagues [16]. Such behaviours disrupted the workplace, jeopardising the safety of victims and their coworkers and threatening productivity. Managers sometimes had to rearrange schedules at short notice to support victims and mitigate risks, imposing increased workloads on other staff [14,19,24,33]. Overall, the studies revealed that IPV negatively affects victims’ working lives and work environments, thereby influencing colleagues’ productivity and the organisation as a whole [14,16,18]. These findings align with research from non-OECD countries associating IPV with absenteeism, tardiness, and consequent economic losses for businesses [8].

Support and assistance provided by employers to employees exposed to IPV varied considerably between (and within) OECD countries. In the United States and Australia, legislation exists to facilitate time off for affected employees [19,29]. However, implementation differs; some workplaces require documentation certifying the need for leave due to IPV [19]. In the United States, inconsistencies in policy definitions and interpretations mean employer support varies by region [21]. Generally, support was offered via workplace policies and programmes [28], HR supervision [30,15], routine enquiry about violence, flexible scheduling, and counselling services [33]. Beyond formal measures, employers also supported employees by listening to their concerns [26] or providing transport to ensure safe commuting [29]. This concurs with previous research emphasising the importance of an organisational culture that adopts a zero-tolerance stance towards IPV and fosters a supportive environment for victims. Evidence suggests that such workplace support can play a pivotal role in mitigating the adverse work-related effects of IPV [10].

The review also identified specific workplace programmes designed to assist IPV victims. For example, New Zealand’s DVFREE programme offers practical tools and resources to manage IPV effectively in the workplace, promoting a culture of safety, awareness, and support [32]. In the United States, the RRR training programme aims to enhance employers’ and employees’ capacity to recognise and respond to IPV promptly [23]. Outside the OECD, an Indian study reported a successful intervention promoting gender equality and raising awareness of violence against women within the workplace [9].

This review possesses several strengths and limitations. It is among the first to comprehensively assess IPV’s impact on workplace environments affecting both male and female victims across OECD countries, incorporating studies of diverse sample sizes, methodologies, and geographical settings. The review also highlights a significant gap in empirical research on this topic within Europe, despite the well-documented health, wellbeing, and occupational consequences of IPV. Moreover, it has not been easy to contrast the results of this literature review due to a lack of comparable studies from other world regions that have empirically examined the impact of IPV on workplace environments. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, only articles written in English were included, which may have influenced the findings. Second, grey literature was excluded, as the focus was limited to peer-reviewed research publications. Finally, the search was restricted to studies published up to May 2025; therefore, more recent literature may contain findings not captured in this review.

Several key areas for future research and policy development emerge from this review. Firstly, the dominance of studies from the United States underscores the need for region-specific research, especially within Europe, to account for cultural and legislative variation. Secondly, the impact of IPV extends beyond victims to colleagues and the wider workplace, necessitating further investigation into productivity losses and organisational costs, alongside the wellbeing of affected coworkers. Thirdly, qualitative research is vital to better understand the effectiveness of existing workplace support and how such assistance is perceived by recipients. Finally, men’s experiences of IPV and their views on workplace support remain underexplored and warrant attention. These gaps carry important policy implications. Policymakers should prioritise culturally and legally tailored interventions based on region-specific evidence. Given the broader organisational impact of IPV, comprehensive workplace strategies are needed to support victims and colleagues indirectly affected. Additionally, policies should emphasise the evaluation and ongoing enhancement of workplace support services, informed by qualitative data on employee experiences. Crucially, recognising and addressing men’s exposure to IPV within policy frameworks is essential to develop inclusive support systems that serve all employees, irrespective of gender.

5 Conclusions

The findings of the review indicate that the prevalence of IPV is widespread and that more female than male employees are victims of IPV. In addition, the employed men and women were exposed to physical, psychological, sexual, and digital violence, which was associated with injuries, stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. The findings indicated that IPV had an impact on the victims’ work environment as these employees were emotionally exhausted from trying to focus and perform well at work despite their exposure to, and fear of, IPV. Consequently, much of their work was passed on to their colleagues. Furthermore, IPV affected the victims’ working life in aspects such as career identity, professional reputation, and opportunities for career development, and the need to take long-term sick leave, which made it difficult for the victims to build a strong employment history, references, and professional credibility. Help and support from employers varied between and within OECD member countries, with support being provided in the form of laws, workplace policies, workplace programmes, and support through HR guidance, safety planning, counselling, and flexible schedules for the victims.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. V.F., J.S., and G.M. contributed equally to the process of writing the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

-

Clinical trial number: Not applicable.

-

Data availability statement: No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Sardinha L, Maheu Giroux M, Stöckl H, Meyer SR, García Moreno C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):803–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Nationellt centrum för kvinnofrid [Internet]. Våld i nära relationer. Uppsala: NCK; 2023. https://www.nck.uu.se/kunskapsbanken/amnesguider/vald-i-nara-relationer/vald-i-nara-relationer/.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sveriges kommuner och regioner [Internet]. Våld i nära relation – stöd till dig som chef: Stödmaterial för arbetsgivare. Stockholm: SKR; 2020. https://skr.se/download/18.3e4bda3818beb99b39ee0f4/1700574145547/Vald-i-nara-relation-stod-for-dig-som-chef-uppdaterad-november2023.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[5] World Health Organization [Internet]. Intimate partner violence. Geneva: WHO; 2022. https://apps.who.int/violence-info/intimate-partner-violence/.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Socialstyrelsen. Våld i nära relationer: Handbok för socialtjänsten, hälso- och sjukvården och tandvården. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Galvez G, Mankowski ES, Glass N. Work-related intimate partner violence, acculturation, and socioeconomic status among employed Mexican men enrolled in batterer intervention programs. Violence Women. 2015;21(10):1218–36. 10.1177/1077801215592719.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Duvvury N, Vara-Horna A, Brendel C, Chadha M. Productivity impacts of intimate partner violence: Evidence from Africa and South America. SAGE Open. 2023;13(4). 10.1177/21582440231205524.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Krishnan S, Gambhir S, Luecke E, Jagannathan L. Impact of a workplace intervention on attitudes and practices related to gender equity in Bengaluru, India. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(9):1169–84. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1156140.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Tolentino LR, Garcia PRJM, Restubog SLD, Scott KL, Aquino K. Does domestic intimate partner aggression affect career outcomes? The role of perceived organizational support. Hum Resour Manag. 2017;56(4):593–611. 10.1002/hrm.21791.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Giesbrecht CJ. Toward an effective workplace response to intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(3–4):1158–78. 10.1177/0886260520921865.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative) Checklist [Internet]. Oxford: CASP; 2018. [cited 2025 Mar 1] https://casp-uk.net/checklists/casp-qualitative-studies-checklist-fillable.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Blodgett C, Lanigan JD. The prevalence and consequences of intimate partner violence intrusion in the workplace. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2018;27(1):15–34. 10.1080/10926771.2017.1330297.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Isola C, Granger S, Turner N, LeBlanc MM, Barling J. Intersection of intimate partner violence, partner interference, and family supportive supervision on victims’ work withdrawal. Occup Health Sci. 2023;7:483–508. 10.1007/s41542-023-00150-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Kulkarni S, Ross TC. Exploring employee intimate partner violence (IPV) disclosures in the workplace. J Workplace Behav Health. 2016;31(4):204–21. 10.1080/15555240.2016.1213637.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Kulkarni SJ, Mennicke AM, Woods SJ. Intimate partner violence in the workplace: Exploring gender differences in current health-related quality of life. Violence Vict. 2018;33(3):519–32. 10.1891/0886-6708.v33.i3.519.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Kumar S, Casey A. Work and intimate partner violence: Powerful role of work in the empowerment process for middle-class women in abusive relationships. Community Work Fam. 2017;23(1):1–18. 10.1080/13668803.2017.1365693.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Laharnar N, Perrin N, Hanson G, Anger WK, Glass N. Workplace domestic violence leave laws: Implementation, use, implications. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2015;8(2):109–28. 10.1108/IJWHM-03-2014-0006.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Lantrip KR, Luginbuhl PJ, Chronister KM, Lindstrom L. Broken dreams: Impact of partner violence on the career development process for professional women. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(5):591–605. 10.1007/s10896-015-9699-5.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Marçal KE, Showalter K, Maguire-Jack K. The impact of state workplace protections on socioeconomic outcomes of IPV survivors. J Fam Violence. 2023;39(6):1–9. 10.1007/s10896-023-00542-6.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Maskin RM, Iverson KM, Vogt D, Smith BN. Associations between intimate partner violence victimization and employment outcomes among male and female post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(4):406–14. 10.1037/tra0000368.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Navarro JN, Jasinski JL, Wick C. Working for change: Empowering employees and employers to “Recognize, Respond, and Refer” for intimate partner abuse. J Workplace Behav Health. 2014;29(3):224–39. 10.1080/15555240.2014.933704.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Pachner TM, Showalter K, Maffett P. The effects of workplace support on workplace disruptions: Differences between white and Black survivors of intimate partner violence. Violence Women. 2022;28(14):3400–14. 10.1177/10778012211060858.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Reibling ET, Distelberg B, Guptill M, Hernandez BC. Intimate partner violence experienced by physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;25(3):311–20. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5216.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Showalter K, McCloskey RJ. A qualitative study of intimate partner violence and employment instability. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(23–24):NP12730–55. 10.1177/0886260520903140.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Showalter K, Marçal K, Maguire-Jack K, Eubank KM, Machinga RO, Park Y. The protective effect of employment policies on intimate partner violence. J Workplace Behav Health. 2024;40(1):15–29. 10.1080/15555240.2024.2312101.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Branicki L, Kalfa S, Pullen A, Brammer S. Corporate responses to intimate partner violence. J Bus Ethics. 2023;187:657–77. 10.1007/s10551-023-05461-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Fitz-Gibbon K, Pfitzner N, McNicol E. Domestic and family violence leave across Australian workplaces: Examining victim-survivor experiences of workplace supports and the importance of cultural change. J Criminol. 2023;56(2–3):294–312. 10.1177/26338076221148203.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chan-Serafin S, Sanders K, Wang L, Restubog SLD. The adoption of human resource practices to support employees affected by intimate partner violence: Women representation in leadership matters. Hum Resour Manag. 2023;62(5):745–64. 10.1002/hrm.22157.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Giesbrecht CJ. The impact of intimate partner violence in the workplace: Results of a Saskatchewan survey. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(3–4):1960–73. 10.1177/0886260520921875.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Carrington H, Williamson R. Responding to domestic violence within the workplace: Reflections and recommendations from the DVFREE workplace initiative in Aotearoa New Zealand. Labour Ind. 2022;32(4):404–28. 10.1080/10301763.2022.2148849.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Sheridan L, North AC, Scott AJ. Stalking in the workplace. J Threat Assess Manag. 2019;6(2):61–75. 10.1037/tam0000124.Search in Google Scholar

[34] LeBlanc MM, Barling J, Turner N. Intimate partner aggression and women’s work outcomes. J Occup Health Psychol. 2014;19(4):399–412. 10.1037/a0037184.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Nationellt centrum för kvinnofrid. Våld och hälsa: En befolkningsundersökning om kvinnors och mäns våldsutsatthet samt kopplingen till hälsa. Uppsala: NCK; 2014. https://kunskapsbanken.nck.uu.se/nckkb/nck/publik/fil/visa/418/NCK-rapport_prevalens_Vald_och_halsa_www.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Sanz-Barbero B, Barón N, Vives-Cases C. Prevalence, associated factors and health impact of intimate partner violence against women in different life stages. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0221049. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221049.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] World Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Summary report. Geneva: WHO; 2005. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43310/9241593512_eng.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Nyberg L, Cederberg D. När män utsätts för våld i en nära relation – hur ser det ut då? En genomgång av internationell forskning. Västra Götaland: Kompetenscentrum om våld i nära relationer; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Hogan KF, Clarke V, Ward T. The impact of masculine ideologies on heterosexual men’s experiences of intimate partner violence: A qualitative exploration. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2024;33(1):123–42. 10.1080/10926771.2022.2061881.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Macassa G, Wijk K, Rashid M, Hiswåls AS, Daca C, Soares J. Interpersonal violence is associated with self-reported stress, anxiety and depression among men in east-central Sweden: Results of a population-based survey. Medicina. 2023;59(2):1–17. 10.3390/medicina59020235.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central