Abstract

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a pathological body dissatisfaction characterised by delusional beliefs of a flaw in appearance paired with obsessive-compulsive rituals. This disorder has a high prevalence in adolescence. This study examines the current state of treatment for BDD in adolescents in the UK to establish a baseline of current treatment, and to identify specific areas for further research. A systematic literature review of two databases was carried out and resultant papers were organised using an amended version of the current UK management standards. Six papers met the eligibility criteria and cognitive behavioural therapy was reported as the most effective current treatment. In drawing together the key findings, three areas for further research were highlighted that are of relevance to a broad range of clinicians working in BDD management in adolescence. These included inquiry into mental health professionals’ perspectives, a review of the rate of remission rates, and research into the extent to which schools can influence adolescents’ ideas about body image. The significance of BDD is not reflected in the current literature base. Education of professionals and the wider community is warranted, as is the drive for improved awareness and an increase in the availability of treatment.

1 Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a chronic psychiatric condition, where patients are abnormally preoccupied with perceived defects in parts of their bodies. BDD results from the complex relationship between biological predisposing factors and environmental stressors [1,2]. Over the last two decades, there has been a sharp increase in the prevalence of BDD, particularly in adolescence [3]. It has been hypothesised that the rising prevalence of BDD among adolescents is due to the increased use of social media, which precipitates comparison and body dissatisfaction [4,5]. For example, Facebook and Instagram are strongly associated with body image dissatisfaction, a precursor of BDD [6]. Psycho-social factors underpin BDD and these factors are reinforced through sociocultural beauty tropes [7], such as subconscious tendencies to categorise people as “attractive” or “unattractive” [8], inherent biases on feature symmetry and skin homogeneity [9], and links between feeling attractive and self-esteem [10]. Due to these factors, a degree of body dissatisfaction exists within society, leading to possible negative evaluations of a person’s own body [11].

Unsurprisingly, it is often the same features that make an “attractive” face that become the subject of discontent, with skin homogeneity being one of the most significant areas of concern [12]. In extreme cases, body dissatisfaction can become pathological, with a perceived flaw in appearance consuming a person’s life, leading to social withdrawal and even suicidality. Patients with BDD show a preference for symmetry and partake in repetitive compulsions [13]; however, there is a lack of compelling evidence to demonstrate the correlation between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and BDD from a neurobiological standpoint [14]. Similarly, the appearance-related concerns in patients with BDD have been described as ego-syntonic in nature, suggesting that they are less likely to be intrusive thoughts as seen in OCD, and more closely linked to overvalued ideas as seen in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [13].

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), outlines the diagnostic criteria for BDD [15]. These criteria, which are outlined below, are commonly used to aid the clinical diagnosis of BDD.

Preoccupation with one or more perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others.

Repetitive behaviours such as mirror checking, excessive grooming, skin picking, camouflaging, and reassurance seeking.

Clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Preoccupation is not better explained by concerns with body fat or weight in an individual whose symptoms meet diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder.

There are issues within the hierarchical organisation of the DSM-5, as it states that a diagnosis of BDD should not be made if the presentation can be accounted for by another disorder, such as an eating disorder [16]. This highlights the link between BDD and eating disorders, as well as the somewhat diminished position of BDD. Additionally, the DSM-5 emphasises the importance of identifying the patient’s level of insight into their condition, noting that over a third of patients have delusional BDD beliefs [15]. The presence of delusional beliefs differentiates BDD from other body dissatisfaction disorders, where the concern is often proportionate to reality [2,11]. Due to insufficient insight, patients with BDD rarely present to psychiatric services.

Although mental health expertise is required to determine the severity of BDD, simple screening tools, such as the BDD Questionnaire, are easily administered and interpreted to identify and diagnose BDD [17]. In the general adult population, the prevalence of BDD is 1.9%, which is higher than the prevalence of other body image disorders with greater public awareness, such as anorexia nervosa (0.3%) and bulimia nervosa (1%) [18]. It is suspected that the true prevalence of BDD is much higher than current estimates due to embarrassment and shame over the perceived “flaw,” which drives secrecy and fear of judgment [19]. BDD disproportionately affects adolescents, with over two-thirds of patients being diagnosed before they turn eighteen [19]. One-fifth of adolescents with BDD reported dropping out of school, severely impacting their learning, social life, and future career [20]. The diagnosis of BDD in adolescence is associated with high comorbidity with other psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and OCD, and therefore, a large proportion of adolescents with BDD are hospitalised [20].

Treatment of BDD is challenging and spans cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), pharmacology, and dermatology [21,22]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend offering CBT as the first-line treatment for adolescents with BDD, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) used as second-line treatment [23]. Other management strategies have emerged with the development of psychodermatology [24], a relatively new field that addresses the bio-psycho-social interactions between skin and mind. Although the availability of these services is increasing, it is still insufficient to meet patient demand, particularly for adolescent patients [25]. Further treatment may be informed by the suggested alignment of BDD and ASD [22], which proposes that therapies such as inference-based therapy and motivational interviewing could help increase engagement and maintain treatment adherence [26].

Greater insight is needed into the management of BDD in adolescence, as there are notable gaps in treatment evidence [27]. Therefore, a systematic literature review was conducted to examine the current state of treatment for BDD in adolescents in the UK, to establish a baseline of current treatment, and to identify specific areas for further research. The UK was selected as the context, as this is where the researchers are based. This enquiry is structured around the PICO model as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [28]. PICO stands for: Patient or problem; Intervention; Comparison, and Outcome(s) and the application of this model is shown in Table 1.

PICO framing

| PICO domains | Areas of enquiry |

|---|---|

| Patient or problem | The management of BDD in adolescents |

| Intervention | The treatment options available in the UK |

| Comparison | Treatment options as outlined in literature in relation to UK BDD guidelines |

| Outcomes | Effective current treatment options and areas for further research |

2 Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The PRISMA statement consists of a checklist that acts as guidance on how to conduct, authorise, or report such a review. Following this resource ensures that a minimum standard of quality is met, facilitating repeatability, review updates, and contributing to the medical educational knowledge [29].

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were decided based on a variety of factors. The language was restricted to English, as this was the researchers’ primary language and due to a lack of access of reliable translating software. The study design was also restricted to peer reviewed journal articles to maximise the reliability of the subsequent information. The content of the articles was restricted to those that dealt specifically with BDD, as opposed to the wider category of OCD or obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (OCRD). Each disorder within OCD or OCRD has unique pathophysiology, triggers and treatment, despite the overlapping symptomology of obsessions and compulsions; however, for clarity of purpose, the screening worked to ensure that sources were clearly focussed on BDD. Similarly, while aspects of eating disorders overlap with BDD, papers were excluded if they only focussed on eating disorders, without reference to BDD. This approach allowed for investigation of overlaps and specificity.

Articles were included where the focus was on the treatment, established or novel, of individuals aged between 10 and 19, using the World Health Organisation’s definition of adolescence [30]. Papers reporting on prevalence, pathophysiology, or risk factors were excluded as they did not meet the scope of the study. The researchers were based in the UK and NICE is the body that provides guidelines for clinicians in the UK, so only UK-based articles were included to maximise relevance. The NICE guidelines for Body Dysmorphia [23] were last updated in November 2005, which is used as the starting date for this review. The search was conducted in August 2024, so only papers published between November 2005 and August 2024 have been included. A summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria is displayed in Table 2, which outlines the eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Language is English | Language is not in English |

| Peer reviewed journal articles | Not peer reviewed journal articles – e.g. books, conference papers |

| BDD specifically | Not solely focussed on OCD, OCRD, eating disorders, or body image dissatisfaction |

| Treatment specific | Not related to treatment e.g. prevalence, pathophysiology, risk factors |

| November 2005 to January 2024 | Outside of the specified date range |

| Age range 10–19 | Outside of the specified age range |

| Published in the UK | Not published in the UK |

2.2 Search strategy

In accordance with guidance from Cochrane [28] and the PRISMA statement [29], at least two databases should be searched during systematic reviews. The two databases searched as part of this research were PubMed and PsychInfo (Table 3). These databases were selected due to their alignment with the area of enquiry. Other databases were excluded as they were too generic (JSTOR, Web of Science), underpowered (DOAJ, Embase), or niche (Statista, Box of Broadcasts). PubMed was selected as it is the largest and widest source of medical journal articles, whereas PsychInfo was selected as this database is more specific to psychodermatology, the specialty of interest related to this topic.

Information sources

| Database | Provider/interface | Date accessed |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | National Centre for Biotechnology Information, at the U.S. National Library of Medicine, located at the National Institute of Health | 01/08/24 |

| PsychINFO | American Psychological Association | 08/08/24 |

This systematic review involved a Boolean search using the following keywords formed of derivatives of “Management,” “Body Dysmorphic Disorder,” and “Adolescence.” Furthermore, these were used in combination with a series of Boolean “AND/OR” operators and asterisk wildcards which are summarised in Table 4.

Search synonyms

| Management | BDD | Adolescents |

|---|---|---|

| Manag* | BDD | Adolescen* |

| Therapy* | Dysmorphophobia | Teen* |

| Treat* | Body Dysmorphia | Youth |

| Assess* | Body Dysmorph* | |

| Intervention |

2.3 Screening procedure

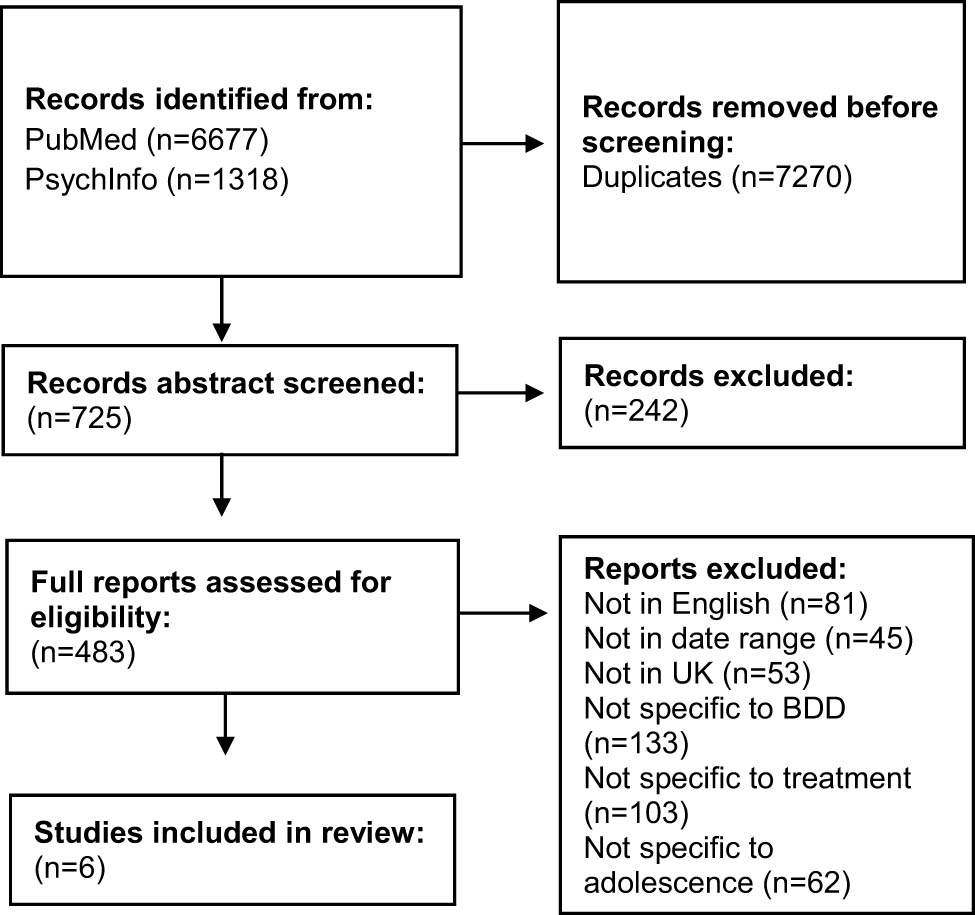

The citations from the search engines of each electronic database were downloaded and imported into the EndNote 20.4. In total, 7,995 articles were identified. EndNote highlighted 7,270 duplicate articles – all which were removed. All remaining articles were then manually screened by author, year, and title, and further duplicates were removed. The abstracts of the identified articles were then manually screened for relevance. After this process all remaining articles were examined in relation to the eligibility criteria, resulting in the final selection of work.

2.4 Data collection and extraction

Data collection and extraction from each article was conducted by one reviewer and confirmed by a second. Each record was assessed rigorously following the eligibility criteria (Table 2).

The data outcomes for each research article are as follows:

Characteristics of all included studies: title, author, date published, study design, and primary outcome measure.

Characteristics of participants included in study: number of participants, demographics, and recruitment process.

Key findings and conclusions derived from the results.

2.5 Quality assessment

To assess the risk of bias, appraisal of each article was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) evidence-based critical appraisal tools – due to their universal usage and trustworthiness. After consideration of study design, the appropriate appraisal tool was applied to each article to ensure an element of standardisation. The JBI tool for randomised control trials has been recently updated to mirror best practice in risk of bias assessment and the case series and case studies tool have been approved as a reliable mechanism of assessment of methodological quality [31,32].

2.6 Data presentation

Current clinical practice in the UK uses the Stepped Care Model to manage BDD [23]. After analysis, a simplified version of the Stepped Care Model was used to frame the findings of this review. Steps 3–6 of the NICE Stepped Care Model were combined as they were variations on treatments. This allowed for data to be discussed under three headings specific to the research focus (Table 5).

Simplified NICE stepped care model

| NICE stepped care model | Core headings |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Awareness and recognition | Awareness and recognition of BDD in adolescents |

| Step 2: Recognition and assessment | Screening and assessment of BDD in adolescents |

| Step 3: Management and initial treatment of OCD or BDD | Treatment options for BDD in adolescents |

| Step 4: OCD or BDD with comorbidity or poor response to initial treatment | |

| Step 5: OCD or BDD with significant comorbidity or more severely impaired functioning and/or treatment resistance, partial response or relapse | |

| Step 6: OCD or BDD with risk to life, severe self-neglect, or severe distress or disability |

2.7 Limitations

This systematic literature review was carried out by two researchers with no funding, leading to limitations related to time and resource constraints. The protocol for this systematic review was not registered, thus increasing the probability of unplanned duplication. However, there was no deviation from the planned protocol and the PRISMA guidelines were adhered to strictly to ensure validity of the method.

3 Results

In adherence to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic literature reviews, the selection process is displayed in Figure 1, which shows the number of papers collected, screened, and excluded. The systematic search resulted in six articles that met the stated eligibility criteria.

A flow diagram to illustrate the selection process.

Of the six papers, three investigated the effectiveness of CBT in adolescence, of which one was a case series which inferred the rationale for the other two studies: A randomised control trial and a follow up study. One was a retrospective case note review of access to treatment specific to BDD in adolescence, and two were narrative literature reviews written from the nursing perspective: One analysing the practical challenges of implementing the NICE guidelines and the other synthesising all current treatment approaches [23]. Data extraction was done in adherence to the defined outcomes. In Table 6, the characteristics of selected studies, primary outcome measure, and key findings are displayed.

Study characteristics

| Title | Author (s) | Year | Key finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementing the NICE OCD/BDD guidelines* | Lovelle and Bee [33] | 2008 | Several barriers to the implementation of the NICE guidelines, including lack of awareness of BDD, low evidence-base, and lack of resources for stepped care system |

| CBT for adolescents with BDD: A case series* | Krebs et al. [34] | 2012 | Four out of six participants were treatment responders, with an average of 44% improvement from baseline post treatment and average of 57% improvement from baseline after 3 or 6 months follow up |

| A pilot randomised controlled trial of CBT for adolescents with BDD* | Mataix-Cols et al. [35] | 2015 | Treatment group showed significantly greater improvement than the control group, both at post treatment and 2 months follow up. Also, improvement of insight, reduced depression, and improvement in quality of life |

| Long-term outcomes of CBT for adolescent BDD* | Krebs et al. [36] | 2017 | Symptom severity remained stable over the 12 months follow up, indicating outcomes from CBT are durable long term, with minimal therapist input. Treatment response increased from 35 to 50% at 12 months follow up |

| BDD in children and young people* | Watson and Ban [37] | 2021 | CBT is first line but emphasis on encouraging engagement is important. SSRIs should be used with caution due to increased suicidality in young people. Public health interventions such as education in school could be an avenue to prevent the development of BDD |

| Access to evidence-based treatments for young people with BDD* | Krebs et al. [38] | 2023 | Currently significant barriers for young people to access CBT specific to BDD due to misdiagnosis and shortage of trained clinicians. Fewer than half of patients with BDD had received CBT for BDD whereas three-quarters of those with OCD had received OCD specific CBT |

*Researchers who study BDD often utilise the Yale Brown Body Dysmorphia Scale for BDD, which has been proven to be a reliable indicator of severity while being sensitive to change [39]. This is useful to determine the effectiveness of interventions.

The characteristics of the participants enrolled in each study are outlined in Table 7. In total, 119 participants were included in this systematic review, taking into consideration that Krebs et al. [36] utilised the same participants as Mataix-Cols [35]. Other than Krebs et al. [34], most of the studies had a female bias, perhaps reflecting the higher prevalence of BDD amongst women. The studies did not specify other demographics of participants such as race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, so it is difficult to assess generalisability.

Participant characteristics

| Study title (author, year) | No. | Sex | Ave. Age | Age of BDD onset | Recruitment method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT for adolescents with BDD: A case series (Krebs et al., 2012) [34] | 6 | 3 F, 3 M | 15.83 | NA | Recruited from a specialist OCRD Clinic (n = 5) and Anxiety Disorders Clinic (N = 1) |

| A pilot randomised controlled trial of CBT for adolescents with BDD (Mataix-Cols et al., 2015) [35] | 30 | 26 F, 4 M | 16 SD = 1.7 | 12.5 SD = 1.9 | Recruited from patients referred to the National and Specialist OCD, BDD, and Related Disorders Clinic. Also, through media and social media |

| Long-term outcomes of CBT for Adolescent BDD (Krebs et al., 2017) [36] | 26 | Not clear | Not clear | Not clear | Participants from above study from both CBT and control groups |

| Access to evidence-based treatments for young people with BDD (Krebs et al., 2023) [38] | 83 | 58 F, 25 M | 15.59 SD = 1.31 | 12.64 SD = 2.74 | Reviewed consecutive referrals to the National and Specialist OCD, BDD, and Related Disorders Clinic between Jan 2015 and May 2022 |

SD = standard deviation.

The two narrative literature reviews have been excluded from this table due to the nature of the study which means they do not have any participants.

3.1 Quality assessment

After using the JBI Risk of Bias Assessment to critically appraise the papers, all selected studies were deemed good quality and therefore, appropriate to include for analysis. Only one study identified was a true randomised control trial – the highest level of research quality. Although all papers identified were deemed appropriate quality after critical appraisal, some papers were of lower “quality” as they were narrative literature reviews, which is a less rigorous approach compared to a systematic review. Three of the papers were written by Krebs, and the paper by Mataix-Cols et al. also listed Krebs as an author. This suggests that all four studies were conducted by the same research group in the same research environment, implying some level of inter-researcher reliability, and a possible lack of generalisability to the wider population due to exposure to the same patient population. The studies themselves had a small sample size across the four studies. While this discrete population and specific environment may suggest some limitations, it should also be recognised that as a specialist unit, the data here were collected by an expert team.

4 Discussion

The analysis of findings is presented here using three headings drawn from the NICE Stepped Care Model [23]. The original model has six steps, but we combined steps 3–6 as they were variations on treatments (Table 5). This left three areas of discussion:

Awareness and recognition of BDD in adolescence

Screening and assessment of BDD in adolescence

Treatment for BDD in adolescents

4.1 Awareness and recognition of BDD in adolescence

The findings show that sufferers of BDD delay getting help by up to 20 years, perhaps due to associated stigma [33]. The population particularly impacted by this stigma are adolescent boys [35]. In recent epidemiological studies, there is a female dominance in the community for BDD; however, in psychiatric settings, the prevalence between sexes is equal [18]. It was suggested that school-based education about body image ideals and perfectionism might help prevent the development of body image related disorders such as BDD through raising awareness, reducing stigma, detecting sufferers earlier, and improving support pathways [36,37,40].

4.2 Screening and assessment of BDD in adolescence

The literature reported a significant shortage of trained clinicians, and that misdiagnosis of BDD was commonplace [38]. The literature also identified that BDD is only fleetingly mentioned in curricula and called for the integration of BDD training into the core curriculum for clinical training programmes [38]. It was also reported that there were very few training courses on identifying BDD which specifically address young people’s needs [33] and recommended that local healthcare providers work to increase the availability and accessibility of resources. Screening in non-mental health settings such as cosmetic surgeries or dermatological clinics was also identified as playing a role [18] especially since delusional BDD beliefs have significantly high risk of patients seeking cosmetic surgery [36].

4.3 Treatment options for adolescents with BDD

Three studies were found to have investigated the effectiveness of CBT for BDD [34–36], one of which found that adolescents who received CBT showed a statistically significant improvement post treatment and at 2 months follow up [35]. Another paper suggested that depression may be secondary to the BDD symptoms, and that treating BDD suppresses depression severity [34]. A follow up study concluded that developmentally tailored CBT is an effective treatment for adolescents with BDD long term [36]. Despite this, it was reported that there are significant barriers for adolescents accessing CBT, mainly due to a lack of awareness and resources [37] and low levels of patient engagement [37]. Pharmacological treatment, namely, SSRIs such as sertraline or fluvoxamine were found to be of some use, if used with caution and under regular monitoring [33]. None of the studies specifically discussed psychodermatology clinics as places of treatment

4.4 Triangulating findings

In drawing together the topics reported above, three areas for further research were identified (Table 8).

Areas for further research

| Research topic/question | Proposed methodology |

|---|---|

| What are the mental health professionals’ perspectives on the current state of management of BDD in adolescence? [33,38] | Focus groups with mental health professionals in different roles and at different levels of training to gather a consensus on their experiences and needs related to managing BDD in adolescence |

| What is the rate of BDD remission in relation to CBT treatment? Is it possible to assess rates of remission against each additional hour of CBT? [33–36] | Identify individuals with different disease severity starting CBT for BDD. Ask them to complete an approved tool for BDD severity before starting CBT and after each session. Plot the number of sessions vs severity scores to identify the number of hours of CBT to result in significant disease remission |

| To what extent are schools able to influence teenagers’ ideas about body image? [37] | Organise a teaching session on body image, with students filling out questionnaires on their experiences and ideas immediately before, immediately after, and a few months after the teaching session |

5 Conclusion

Although all six of the identified papers supported current best-practice of psychological intervention as first-line treatment, several issues were raised regarding lack of awareness, lack of training, poor resource allocation, and insufficient rigorous evidence in the field. With the disproportional impact of BDD on adolescents and the rapid acceleration in prevalence, this is an avenue that demands more research. The identified papers revealed issues in the current state of management of BDD for adolescents in the UK. It was found that there is a societal stigma towards BDD, which results in delayed help seeking by up to two decades [33]. This stigma was found to be propelled by the growth of social media which has normalised body dissatisfaction – a significant risk factor for developing BDD [37]. Misdiagnosis of BDD was found to be commonplace because BDD is not a part of the core curriculum for mental health professionals working with adolescence, leading to a lack of trained staff to manage this increasingly prevalent condition [33,38]. Therefore, it was reported that when sufferers finally build the courage to seek help, they may not be met with understanding or appropriate support. If psychological support is inadequate to disrupt a patient’s delusional beliefs, they are far more likely to request cosmetic procedures, causing unnecessary patient harm [36]. Despite the issues raised, three papers affirmed that psychological therapy, specifically CBT with exposure with response prevention, is an effective tool to reduce the severity of BDD in adolescence [34–36].

The NICE Stepped Care Model [23] provides guidance for the management of adults, adolescence, and young people with BDD and OCD in the UK. The identified literature criticised this grouping, identifying that BDD is diagnostically distinct from OCD [33]. It was also revealed that the guidelines are based on significantly limited evidence, especially for young people where both the number and quality of studies were negligible [33]. This systematic review echoes this sentiment, as the search only revealed one novel randomised control trial.

In drawing together the key findings, this systematic review identifies three areas of further research. These include inquiry into mental health professionals’ perspectives on the current state of BDD management in adolescence, a review of the rate of BDD remission in relation to CBT treatment, and research into the extent to which schools are able to influence teenagers’ ideas about body image.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the reviewer’s valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Both authors accepted the responsibility for the content of the manuscript and consented to its submission, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. The authors contributions were as follow: conceptualisation: T.G. and E.B., methodology: T.G. and E.B., investigation and resources: T.G., data curation: T.G. and E.B., writing – original draft: T.G., writing – review and editing: T.G. and E.B., visualisation: E.B. and T.G., supervision: E.B., project administration: E.B.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Weiffenbach A, Kundu RV. Body dysmorphic disorder: etiology and pathophysiology. In: Vashi NA, editor. Beauty and body dysmorphic disorder: A clinician’s guide. Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. 115–25.10.1007/978-3-319-17867-7_8Search in Google Scholar

[2] Cororve MB, Gleaves DH. Body dysmorphic disorder: a review of conceptualizations, assessment, and treatment strategies. Obsessive-Compulsive Disord Tourette’s Syndr. 2022 Apr;1:13–34.10.4324/9780203822937-2Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kaur A, Kaur A, Singla G. Rising dysmorphia among adolescents: A cause for concern. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020 Feb;9(2):567–70.10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_738_19Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Rizwan B, Zaki M, Javaid S, Jabeen Z, Mehmood M, Riaz M, et al. Increase in body dysmorphia and eating disorders among adolescents due to social media: Increase in Body Dysmorphia and Eating Disorders Among Adolescents. Pak Biomed J. 2022 Mar;5(3):148–52.10.54393/pbmj.v5i1.205Search in Google Scholar

[5] Revranche M, Biscond M, Husky MM. Investigating the relationship between social media use and body image among adolescents: A systematic review. L’encephale. 2021 Nov;48(2):206–18.10.1016/j.encep.2021.08.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Jiotsa B, Naccache B, Duval M, Rocher B, Grall-Bronnec M. Social media use and body image disorders: Association between frequency of comparing one’s own physical appearance to that of people being followed on social media and body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2021 Mar;18(6):2880.10.3390/ijerph18062880Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Thornborrow T, Evans EH, Tovee MJ, Boothroyd LG. Sociocultural drivers of body image and eating disorder risk in rural Nicaraguan women. J Eat Disord. 2022 Sep;10(1):133.10.1186/s40337-022-00656-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Vashi NA. Obsession with perfection: Body dysmorphia. Clin Derm. 2016 Nov;34(6):788–91.10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.04.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Little AC, Jones BC, DeBruine LM. Facial attractiveness: evolutionary based research. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2011 Jun;366(1571):1638–59.10.1098/rstb.2010.0404Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] O’Connor KM, Gladstone E. Beauty and social capital: Being attractive shapes social networks. Soc Netw. 2018 Jan;52:42–7.10.1016/j.socnet.2017.05.003Search in Google Scholar

[11] Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Nov;53(5):985–93.10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9Search in Google Scholar

[12] Schut C, Dalgard FJ, Bewley A, Evers AW, Gieler U, Lien L, et al. Body dysmorphia in common skin diseases: results of an observational, cross‐sectional multicentre study among dermatological outpatients in 17 European countries. Brit J Derm. 2022 Jul;187(1):115–25.10.1111/bjd.21021Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Hong K, Nezgovorova V, Hollander E. New perspectives in the treatment of body dysmorphic disorder. F1000Research. 2018;7:361.10.12688/f1000research.13700.1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] McCurdy-McKinnon D, Feusner JD. Neurobiology of body dysmorphic disorder: heritability/genetics, brain circuitry, and visual processing. In: Phillips KA, editor. Body dysmorphic disorder: Advances in research and clinical practice. 2017. p. 253–56.10.1093/med/9780190254131.003.0020Search in Google Scholar

[15] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596Search in Google Scholar

[16] Mitchison D, Crino R, Hay P. The presence, predictive utility, and clinical significance of body dysmorphic symptoms in women with eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2013;1:20.10.1186/2050-2974-1-20Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Türk CB, Maymone MB, Kroumpouzos G. Body dysmorphic disorder: A critical appraisal of diagnostic, screening, and assessment tools. Clinics Derm. 2023 Jan;41(1):16–27.10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Veale D, Gledhill LJ, Christodoulou P, Hodsoll J. Body dysmorphic disorder in different settings: A systematic review and estimated weighted prevalence. Body Image. 2016 Sep;18:168–86.10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.07.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Bjornsson AS, Didie ER, Grant JE, Menard W, Stalker E, Phillips KA. Age at onset and clinical correlates in body dysmorphic disorder. Comp Psych. 2013 Oct;54(7):893–903.10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Phillips KA, Kelly MM. Body dysmorphic disorder: clinical overview and relationship to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Focus. 2020 Oct;19(4):413–9.10.1176/appi.focus.20210012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Drummond L, Fineberg N, Heyman I, Veale D, Jessop R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(5):570–5.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Enander J, Ljótsson B, Anderhell L, Runeborg M, Flygare O, Cottman O, et al. Long-term outcome of therapist-guided internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD-NET): A naturalistic 2-year follow-up after a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e024307. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024307.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Body dysmorphic disorder: Clinical guideline. London: NICE; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Jafferany M, Franca K. Psychodermatology: basics concepts. Acta Dermato-venereologica. 2016 Jul;96(217):35–7.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Massoud SH, Alassaf J, Ahmed A, Taylor RE, Bewley A. UK psychodermatology services in 2019: service provision has improved but is still very poor nationally. Clin Exper Derm. 2021 Aug;46(6):1046–51.10.1111/ced.14641Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Phillips KA, Menard W, Fay C. Gender similarities and differences in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Comp Psychiatry. 2006 Mar;47(2):77–87.10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Krebs G, Rautio D, Fernández de la Cruz L, Hartmann AS, Jassi A, Martin A, et al. Practitioner Review: Assessment and treatment of body dysmorphic disorder in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2024 May;65(8):1119–31.10.1111/jcpp.13984Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated August 2024). Chichester: Cochrane; 2024. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj. 2021 Mar;372:n71.10.1136/bmj.n71Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] World Health Organization. A clinical case definition for post COVID-19 condition in children and adolescents by expert consensus. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Barker TH, Stone JC, Sears K, Klugar M, Tufanaru C, Leonardi-Bee J, et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(3):494–506. 10.11124/JBIES-21-856.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evidence. Synthesis. 2020;18(10):2127–33. 10.11124/JBIES-18-653.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Lovell K, Bee P. Implementing the NICE OCD/BDD guidelines. Psychol Psychotherapy: Theory, Res Pract. 2008 Dec;81(4):365–76.10.1348/147608308X320107Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Krebs G, Turner C, Heyman I, Mataix-Cols D. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder: A case series. Behav Cog Psych. 2012;40(4):452–61. 10.1017/S1352465812000023.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Mataix-Cols D, de la Cruz LF, Isomura K, Anson M, Turner C, Monzani B, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2015;54(11):895–904. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Krebs G, de la Cruz LF, Monzani B, Bowyer L, Anson M, Cadman J, et al. Long-term outcomes of cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Ther. 2017;48(4):462–73. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.12.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Watson C, Ban S. Body dysmorphic disorder in children and young people. Brit J Nurs. 2021;30(3):160–4. 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.3.160.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Krebs G, Rifkin-Zybutz R, Clark B, Jassi A. Access to evidence-based treatments for young people with body dysmorphic disorder. Arch Dis Child. 2023;108(8):684–5. 10.1136/archdischild-2022-323754.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Phillips KA, Pinto A, Hart AS, Coles ME, Eisen JL, Menard W, et al. A comparison of insight in body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Psych Res. 2012;46(10):1293–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Yager J, Devlin MJ, Halmi KA, Herzog DB, Mitchell III JE, Powers P, et al. Guideline watch (August 2012): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Focus. 2014;2(4):416–31. 10.1176/appi.focus.12.4.416.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Relationship between body mass index and quality of life, use of dietary and physical activity self-management strategies, and mental health in individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome

- Evaluating the challenges and opportunities for diabetes care policy in Nigeria

- Body mass index is associated with subjective workload and REM sleep timing in young healthy adults

- Prediction of hypoglycaemia in subjects with type 1 diabetes during physical activity

- Investigation by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale of daytime sleepiness in professional drivers during work hours

- Understanding public awareness of fall epidemiology in the United States: A national cross-sectional study

- Impact of Covid-19 stress on urban poor in Sylhet Division, Bangladesh: A perception-based assessment

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, relationship satisfaction, and socioeconomic status: United States

- Psychological factors influencing oocyte donation: A study of Indian donors

- Cervical cancer in eastern Kenya (2018–2020): Impact of awareness and risk perception on screening practices

- Older LGBTQ+ and blockchain in healthcare: A value sensitive design perspective

- Trends and disparities in HPV vaccination among U.S. adolescents, 2018–2023

- Do cell towers help increase vaccine uptake? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire

- In search of the world’s most popular painkiller: An infodemiological analysis of Google Trend statistics from 2004 to 2023

- Brain fog in chronic pain: A concept analysis of social media postings

- Association between multidimensional poverty intensity and maternal mortality ratio in Madagascar: Analysis of regional disparities

- A “disorder that exacerbates all other crises” or “a word we use to shut you up”? A critical policy analysis of NGOs’ discourses on COVID-19 misinformation

- Smartphone use and stroop performance in a university workforce: A survey-experiment

- Review Articles

- The management of body dysmorphic disorder in adolescents: A systematic literature review

- Navigating challenges and maximizing potential: Handling complications and constraints in minimally invasive surgery

- Examining the scarcity of oncology healthcare providers in cancer management: A case study of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

- Dietary strategies for irritable bowel syndrome: A narrative review of effectiveness, emerging dietary trends, and global variability

- The impact of intimate partner violence on victims’ work, health, and wellbeing in OECD countries (2014–2025): A descriptive systematic review

- Nutrition literacy in pregnant women: a systematic review

- Short Communications

- Experience of patients in Germany with the post-COVID-19 vaccination syndrome

- Five linguistic misrepresentations of Huntington’s disease

- Letter to the Editor

- PCOS self-management challenges transcend BMI: A call for equitable support strategies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Relationship between body mass index and quality of life, use of dietary and physical activity self-management strategies, and mental health in individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome

- Evaluating the challenges and opportunities for diabetes care policy in Nigeria

- Body mass index is associated with subjective workload and REM sleep timing in young healthy adults

- Prediction of hypoglycaemia in subjects with type 1 diabetes during physical activity

- Investigation by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale of daytime sleepiness in professional drivers during work hours

- Understanding public awareness of fall epidemiology in the United States: A national cross-sectional study

- Impact of Covid-19 stress on urban poor in Sylhet Division, Bangladesh: A perception-based assessment

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, relationship satisfaction, and socioeconomic status: United States

- Psychological factors influencing oocyte donation: A study of Indian donors

- Cervical cancer in eastern Kenya (2018–2020): Impact of awareness and risk perception on screening practices

- Older LGBTQ+ and blockchain in healthcare: A value sensitive design perspective

- Trends and disparities in HPV vaccination among U.S. adolescents, 2018–2023

- Do cell towers help increase vaccine uptake? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire

- In search of the world’s most popular painkiller: An infodemiological analysis of Google Trend statistics from 2004 to 2023

- Brain fog in chronic pain: A concept analysis of social media postings

- Association between multidimensional poverty intensity and maternal mortality ratio in Madagascar: Analysis of regional disparities

- A “disorder that exacerbates all other crises” or “a word we use to shut you up”? A critical policy analysis of NGOs’ discourses on COVID-19 misinformation

- Smartphone use and stroop performance in a university workforce: A survey-experiment

- Review Articles

- The management of body dysmorphic disorder in adolescents: A systematic literature review

- Navigating challenges and maximizing potential: Handling complications and constraints in minimally invasive surgery

- Examining the scarcity of oncology healthcare providers in cancer management: A case study of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

- Dietary strategies for irritable bowel syndrome: A narrative review of effectiveness, emerging dietary trends, and global variability

- The impact of intimate partner violence on victims’ work, health, and wellbeing in OECD countries (2014–2025): A descriptive systematic review

- Nutrition literacy in pregnant women: a systematic review

- Short Communications

- Experience of patients in Germany with the post-COVID-19 vaccination syndrome

- Five linguistic misrepresentations of Huntington’s disease

- Letter to the Editor

- PCOS self-management challenges transcend BMI: A call for equitable support strategies