Abstract

The development of human resources is a significant issue in the global nonprofit context, and Japan is no exception with its relatively small philanthropic sector. In such countries, the government can be regarded as a potential resource provider. Nevertheless, thus far the Japanese government’s support for the nonprofit sector has been limited to taxation and corporate law. However, the act on utilization of funds related to dormant deposits to promote public interest activities by the private sector became the first policy measure related to nonprofit human resource development, especially focusing on the program officer (PO)’s roles via nonprofit sectorial capacity-building. In order to maximize this political opportunity, it is indispensable to fundamentally address the questions identifying what competencies and responsibilities are expected from POs and what kind of individuals are engaged. This research conducted exploratory research to elucidate this in Japan, gaining insights for advancing future human resource development policies. The results illustrated that POs were well-educated and had experience working in various sectors. Moreover, years of experience had a statistically significant relationship with their roles and the competencies they considered important. Furthermore, the results highlighted the limited training opportunities for POs and suggested that sector-related policies influence the environment in which POs develop and operate. This study indicates the importance of developing human resources in the nonprofit sector by collaborating beyond sectors and sheds light on the opportunities to utilize government policy measures for nonprofit capacity-building.

1 Introduction

Nonprofit human resource development (HRD) needs adequate financial resources and training opportunities. However, obtaining and managing them sustainably remains challenging in the current insecure global financial situation. In regards to the size of their philanthropic sectors, the amount of individual charitable contribution flowing into the nonprofit sector markedly contrasts between the U.S. and Japan, with the U.S. allocating 1.55 % of GDP to funding in 2020, compared to Japan’s 0.23 %. Donations totaled 324.1 billion USD in the U.S., approximately 34 times higher than those in Japan (Japan Fundraising Association 2021). Even though the U.S. maintains one of the largest philanthropic resources, many nonprofit organizations (NPOs) struggle to allocate funds for HRD (Carpenter et al. 2013; Stahl 2013).

Considering this, how can HRD be implemented effectively in a country like Japan, where the nonprofit sector is relatively underdeveloped? One possible resource provider is the government acting through strategic collaboration. The implementation of the act on utilization of funds related to dormant deposits to promote public interest activities by the private sector (Dormant Deposits Utilization Act [DDUA]) in Japan, which employs a significant amount of quasi-public deposit funds, is one of the few notable indicators in the nonprofit sector of a recent policy trend toward allowing personnel expenditures, primarily related to HRD and sector capacity-building.

Yet, to assess whether government support and policies are effectively developing competent POs – who are essential to creating social impacts through grantmaking for NPO activities – it is crucial to identify the expected competencies and responsibilities of POs, as well as the profiles of those in these roles. While PO’s roles and skill development have been discussed in a practical setting, knowledge and anecdotal perspectives from a few of the experienced officers have been prominent. Further research is needed on this, and as the first step of this process, this study conducted exploratory research to capture the demographics, responsibilities, and competencies of POs active in the Japanese nonprofit sector, thereby gaining insights for advancing future HRD policies and obtaining policy suggestions for HRD in the civil sector.

As social issues become increasingly complex, NPOs are facing many challenges, including budget cuts, globalization, and diversification of program needs. The government at all levels becomes less engaged in direct service delivery and relies on NPOs (Pynes 2009), which places the socio-democratic and welfare infrastructure at risk. However, unlike the for-profit sectors and public administration, the nonprofit sector is characterized by its complex fundraising and resource management system; hence, the development of highly qualified and competent personnel capable for this role is urgently needed.

In the following sections, we review the literature on what roles “POs” have and what personality and competencies are required as professional fundraisers in civil society. Subsequently, we present a unique questionnaire which illustrates the current real-world PO responsibilities and professional competencies.

2 Literature Review: Nonprofit HRD and POs

HRD has attracted researchers’ and practitioners’ attention in nonprofit management since the 1990s (Knies et al. 2024) and has been discussed in hundreds of empirical and conceptual articles from multiple angles, such as employment and human resource administration (Ban et al. 2003; Carpenter et al. 2015), career and talent development (Stahl 2013; Stewart and Kuenzi 2018), and competencies and leadership (DeSimone and Roberts 2023; Genis 2008; Ronquillo et al. 2013). While private companies only need to achieve a single bottom line, NPOs are characterized to achieve their mission (Knies et al. 2024) by considering double- or triple-bottom lines. Thus, HRD in NPOs cannot be adopted directly from private sector management practices. In fact, Knies et al. (2024) compared the HRD strategies of NPOs with those of for-profit entities and found that although NPOs use strategies to enhance competencies and opportunities, they do not use financial incentives because they undermine the intrinsic motivation of mission- and purpose-driven staff. In addition, while many NPOs depend on the capital for HRD from philanthropic foundations and donors via grants and charitable donations, Stahl (2013) indicated that these sources were under-supported. Research exhibited that NPOs only assigned 2 percent or less of the budget for staff development (Carpenter et al. 2013). Baluch and Ridder (2021) conducted a systematic review of strategic human resource management. Although it accounted for the impact of the external pressures on HRD in NPOs, external pressures, namely governmental nonprofit policies, were outside the scope of their analysis.

POs play an essential role in optimizing the impact of grants. The term “program officer” first appeared in the Ford Foundation’s annual report in 1966; however, even before 1965, similar positions and roles were held by “associate directors” (Makita 2007, p. 28). Carpenter et al. (2015, p. 76) described their responsibilities as coordinating various grantmaking programs simultaneously and reviewing grant proposals while assessing organizational goals, plans, and capacity. Furthermore, Carpenter et al. (2015) mentioned that staff members of social change-oriented organizations, including POs, need to have multiple leadership competencies. For instance, while the PO is primarily responsible for grantmaking, they are also required to take responsibility for advocacy by developing and tracking knowledge of trends regarding social and community issues and play a range of roles in communication and marketing by building strategic relationships with other stakeholders (Carpenter et al. 2015). This diversity of roles follows Orosz’s (2000) view that what a PO does could never be captured by terms such as philanthropist, funder, or grantmaker. Further research on PO competencies has led to the Program Officer Competency Model (POCM) (Dorothy A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy 2021), which identifies 19 PO competencies in four categories based on a systematic review of PO job descriptions and reports (Table 1).

Core competency dimensions for effective PO performance.

| Cross-cutting | Relationships & field-building | Proposals & due diligence | Strategy, evaluation, & leaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive practice | Communication | Proposal solicitation, review & analysis | Strategy development & implementation |

| Grantmaking philosophy & approach | Collaboration | Risk management | Evaluation design & management |

| Analytical thinking | Grantee-grantmaker relationships | Financial analysis | Sharing learning |

| Ethics & accountability | Grantee capacity building | Organizational assessment | Monitoring & reporting |

| Advancing learning | Sector knowledge | Power dynamics |

-

This table was created by the authors based on “Program officer competency model (POCM)” (Dorothy, A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy 2021).

3 Case: DDUA in Japan

3.1 Background and System of Using Dormant Deposits for Charitable Purposes in Japan

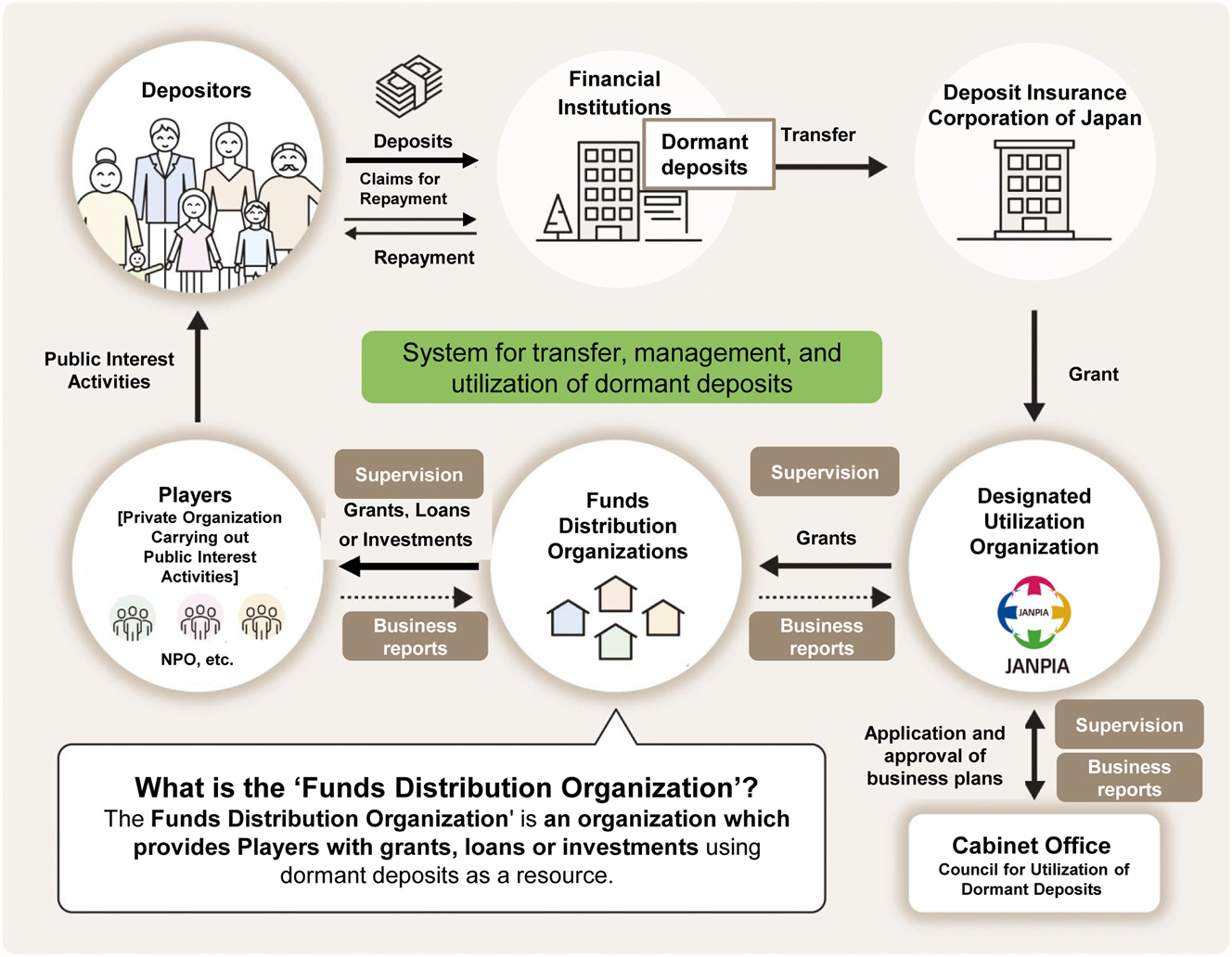

The dormant deposits have been utilized for charitable purposes in the U.K., Ireland, and Korea in the 2000s; Japan followed these countries and enacted the DDUA in 2018. Dormant deposits are those that have exhibited no transactional activities (e.g., deposit and withdrawal) for 10 years or more (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan 2018). In Japan, dormant deposits amount to approximately 140 billion JPY annually (2019–2022 average) (Cabinet Office and Government of Japan 2023). While the U.S., France, and Australia utilize dormant deposits by integrating them into national and/or state budgets, the U.K., Ireland, Korea, and Japan assigned an organization dedicated to funds allocation. The Japan Network for Public Interest Activities (JANPIA) was assigned as the Designated Utilization Organization (DUO) and has been allocating funds since 2018. JANPIA was allocated approximately 9.3 billion JPY in 2022 for the organization’s operating expenses and grant allocations (JANPIA 2022). JANPIA approves grant applications from grantmaking foundations and nonprofit intermediary organizations, which are called “Funds Distribution Organizations” (FDOs) in the policy, to ensure they can provide grants to local or designated civil activities. An overview of the policy system is depicted in Figure 1.

System of dormant deposit utilization. Note. The image was cited from “What is utilization of dormant deposits”? By JANPIA 2019 (https://www.janpia.or.jp/en/common/pdf/top_20190816.pdf). A New Policy Supporting PO as Part of the Dormant Fund Distribution. Content and data as of the end of 2019. The content updated at: https://www.janpia.or.jp/en/common/pdf/about_janpia.pdf

3.2 A New Policy Supporting PO as Part of the Dormant Fund Distribution

The conceptualization of philanthropy in Japan has been reported in the literature (Hayashi and Yamaoka 1984; Onishi 2017; Yamamoto 1998). While the legal and political sides of nonprofit sector development have been noted since the 1990s (Yamamoto 1998), they have lagged significantly behind those of other Western countries. Moreover, no ministry or department of the central government has authority over policies related to the entire nonprofit sector.

Most policies in the Japanese legal and policy system related to the nonprofit sector have been limited to taxation and corporate status for nonprofit corporations (Hatsutani 2001; Salamon and Anheier 1997; Salamon et al. 1999; Yamamoto 1998). In the late 2000s, the Japanese government expanded financial assistance for nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations via ODA from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and privatization of care services for people with disabilities and older adults. After 2009, while we observed that several policies encompassed the entire nonprofit sector for advancing collaboration with the nonprofit sector due to government policy agenda and the Tohoku Earthquake under the leadership of the Democratic Party of Japan, our review process clarifies that the scope of Japan’s nonprofit policy is narrow, necessitating systematic research that considers other related policies from a broader perspective. Against this background, a debate recently occurred on the issue of hiring and developing capacities of POs under the DDUA.

A unique aspect of this policy is that the training lectures for POs are officially organized by the DUO and are required for POs of FDOs to use the funds for grantmaking. The use of dormant deposits for PO personnel costs, including hiring costs and salary, was initially controversial; however, after much discussion among the legislators, bureaucrats, nonprofit experts, and practitioners, personnel costs were approved, with the explicit condition that POs subject to personnel costs must attend training as a guarantee of practice quality. The government needs to determine whether the policy’s contribution of personnel costs will have positive impacts. However, the controversy surrounding this policy highlighted the lack of awareness and understanding of the importance of the role of POs, and we must more accurately investigate their characteristics for policy improvement.

4 Methodology

To develop the survey design for capturing PO trends, we followed the methodological guidance provided by Dillman et al. (2014). However, the grantmaking foundations’ list, which the Japan Foundation Center (JFC) developed, was not fully comprehensive. Although Japan has legal entities referred to as foundations, not all of them are grantmaking organizations and there are other organizations which carry out grantmaking projects as different nonprofit legal entities. For these reasons, it has been difficult to determine how many people are working as POs, let alone the number of actual grantmaking organizations. Since the notion of the PO has not been thoroughly recognized in the Japanese nonprofit sector, there was also the possibility that people who performed grant work did not call themselves POs or did grant work under other positions. Considering these circumstances, we utilized nonprobability sampling to produce results relatively quickly to gain insights by conducting internet-based snowball sampling via networks of POs working for nationwide, local, or international grant programs and major and traditional charitable foundations with which we have practical and professional connections. The survey was designed for individuals working primarily on project grants aimed at solving social problems, not on research grants. This survey gathered responses from 106 participants.

To ensure the robustness and uniqueness of the data, we conducted a pre-test with six experienced practitioners selected from different kinds of grantmaking projects in terms of area, theme, grant amount, and mission. The pre-test taught us the necessity to clarify the terminology, reconsider the volume of the survey and wording choice, and reorganize the order of questions. We developed our questionnaire and conducted the survey between September 10 and October 7, 2022, in the form of a web-based questionnaire targeting those who provide grants and other types of funding to NPOs.

If respondents from the same organization provided inconsistent information, the response of the highest-ranking position holder among the respondents was adopted. Responses that contained errors or were logically inconsistent were either excluded from the tabulation, treated as missing values, or corrected based on publicly available information.

5 Analysis and Results

5.1 Sample Descriptions

This section provides a fundamental description of the respondents. As presented in Table 2, they comprised 62 (58.5 %) males and 43 (40.6 %) females. Respondents in their 40s (41.5 %) were the most common. Approximately 90 % of respondents were university graduates (59.4 %) and graduate school graduates (30.2 %). The respondents were considered to be highly educated, despite the university enrollment rate in Japan being only 56.6 % in 2022 (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science & Technology 2022).

Descriptive statistics of POs-demographics, experience, and performance indicators.

| Variable | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 62 | 58.5 % |

| Female | 43 | 40.6 % | |

| Not identified | 1 | 0.9 % | |

|

|

|||

| Total | 106 | 100 % | |

|

|

|||

| Age | 20s | 3 | 2.8 % |

| 30s | 27 | 25.5 % | |

| 40s | 44 | 41.5 % | |

| 50s | 18 | 17.0 % | |

| 60s | 13 | 12.3 % | |

| 70s | 1 | 0.9 % | |

|

|

|||

| Total | 106 | 100 % | |

|

|

|||

| Educational background | Junior high school | 1 | 0.9 % |

| High school | 5 | 4.7 % | |

| Vocational school | 4 | 3.8 % | |

| University | 63 | 59.4 % | |

| Graduate school | 32 | 30.2 % | |

| Other | 1 | 0.9 % | |

|

|

|||

| Total | 106 | 100 % | |

|

|

|||

| PO working experices | Less than 1 year | 15 | 14.2 % |

| 1–3 years | 43 | 40.6 % | |

| 3–5 years | 10 | 9.4 % | |

| 5–10 years | 18 | 17.0 % | |

| 10–15 years | 12 | 11.3 % | |

| 15–20 years | 4 | 3.8 % | |

| 20 or more years | 4 | 3.8 % | |

|

|

|||

| Total | 106 | 100 % | |

|

|

|||

| Working experience in the nonprofit sector before becoming a PO | None | 34 | 32.1 % |

| Less than 1 year | 3 | 2.8 % | |

| 1-3 years | 13 | 12.3 % | |

| 3-5 years | 12 | 11.3 % | |

| 5-10 years | 21 | 19.8 % | |

| 10-15 years | 11 | 10.4 % | |

| 15-20 years | 5 | 4.7 % | |

| 20 or more years | 7 | 6.6 % | |

|

|

|||

| Total | 106 | 100 % | |

|

|

|||

| Median grant amount for projects that respondents are in charge for | ∼500,000 JPY | 6 | 5.7 % |

| 5000,000∼1 million JPY | 7 | 6.6 % | |

| 1 to 3 million JPY | 20 | 18.9 % | |

| 3 to 5 million JPY | 18 | 17.0 % | |

| 5 to 8 million JPY | 17 | 16.0 % | |

| 8 to 10 million JPY | 10 | 9.4 % | |

| 10 to 20 million JPY | 15 | 14.2 % | |

| 20 to 50 million JPY | 5 | 4.7 % | |

| 50 to 100 million JPY | 6 | 5.7 % | |

| 100 million or more | 2 | 1.9 % | |

|

|

|||

| Total | 106 | 100 % | |

As for years of PO working experience, more than half (54.8 %) had worked as POs for less than three years, while some (18.9 %) had worked as experienced POs for more than 10 years. Thirty-four (32.1 %) respondents had no experience in the nonprofit sector before becoming a PO, but more than half (52.8 %) had worked in the sector for more than three years. As presented in Table 2, 18.9 % of respondents handled grants of 1–3 million JPY, 17.0 % of 3–5 million JPY, and 16.0 % of 8–10 million JPY. The amount of money handled varied considerably across POs; although some POs handled grants of more than 100 million JPY, others handled grants of less than 500,000 JPY (Figure 2).

Median, minimum, and maximum grant amounts handled by POs.

Respondents’ PO responsibilities are presented in Table 3. In terms of the percentage of PO work time spent on each category, the median for non-financial support was 25 %, more than any other work category. However, the standard deviation was also high. The median values for program development and modification, grant application recruitment and reception, and application review were higher than the other work categories. Moreover, the minimum value for each category was 0 %, which may indicate differences in the kind of work POs perform.

Percentage of time spent by POs on key tasks.

| Variable | Mean | Median | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program development and modification | 13.64 | 10 | 12.45 | 0 | 70 |

| Grant application recruitment and reception | 9.6 | 10 | 7.98 | 0 | 40 |

| Application review | 10.41 | 9 | 10.62 | 0 | 70 |

| Program monitoring | 7.36 | 5 | 7.81 | 0 | 40 |

| Nonfinancial support | 28.79 | 25 | 19.65 | 0 | 90 |

| Audit at the end of the grant | 2.92 | 0.5 | 4.05 | 0 | 20 |

| Follow-up after the grant | 4.82 | 4 | 6.20 | 0 | 30 |

| Managerial tasks on foundation’s administration and supervision | 6.05 | 5 | 8.45 | 0 | 50 |

| Managerial tasks on foundation’s staff development | 3.98 | 3 | 5.01 | 0 | 50 |

| Foundation’s PR, advertisement, and fundraising | 5.71 | 5 | 7.79 | 0 | 50 |

| Other duties | 6.72 | 5 | 9.24 | 0 | 50 |

When asked whether POs had received systematic professional training in PO practice at their current organization prior to engaging in grantmaking, 83 % responded that they had not. In contrast, 31.1 % voluntarily received training outside their organization, and 23.6 % received training under the direction of their organization. However, 45.3 % received no training.

Regarding having someone to consult when facing dilemmas or problems in their practice as POs, 58.5 % answered that there was someone within or outside their organization, 27.4 % answered within their organization, and 8.5 % answered outside their organization, while 5.7 % answered that there was no one they could consult.

5.2 Statistical Analysis of Years of PO Experience and PO Duties

In addition to the basic findings on the current situation of POs, the research purpose is derived from the PO training using dormant deposits to develop their skills and competencies. Therefore, we conducted statistical inference to examine what POs in Japan actually recognize as PO competencies and duties and whether there is a difference between those who started working in PO duties after the use of dormant deposits began and those who had been working in PO duties before that.

For the competencies of POs, we used the POCM and asked POs to select which competencies were considered important from multiple answers. Many were recognized as necessary, but the top three choices were the ability to communicate with stakeholders (49 respondents), the ability to promote collaboration with people within and outside the organization (30 respondents), and analytical thinking (28 respondents) (Figure 3).

Important PO Competencies (N).

The respondents were divided into two groups (those with less than [54.8 %] and more than [45.3 %] three years of experience) to analyze whether PO duties and roles differ depending on the duration of PO experience (Table 4).

Group statistics of PO duties and duration of PO experience.

| Variable | Category | N | Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program development and modification | Less than 3 years | 58 | 12.12 | 12.52 | 1.64 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 15.48 | 12.24 | 1.77 | |

| Grant application recruitment and reception | Less than 3 years | 58 | 9.53 | 8.56 | 1.12 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 9.69 | 7.32 | 1.06 | |

| Application review | Less than 3 years | 58 | 7.31 | 7.38 | 0.97 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 14.15 | 12.64 | 1.83 | |

| Program monitoring | Less than 3 years | 58 | 8.14 | 8.94 | 1.17 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 6.42 | 6.13 | 0.89 | |

| Nonfinancial support | Less than 3 years | 58 | 35.60 | 21.09 | 2.77 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 20.56 | 14.01 | 2.02 | |

| Audit at the end of the grant | Less than 3 years | 58 | 1.93 | 3.56 | 0.47 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 4.13 | 4.32 | 0.62 | |

| Follow-up after the grant | Less than 3 years | 58 | 4.97 | 7.71 | 1.01 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 4.65 | 3.70 | 0.53 | |

| Managerial tasks on foundation’s administration and supervision | Less than 3 years | 58 | 5.26 | 8.98 | 1.18 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 7.00 | 7.75 | 1.12 | |

| Managerial tasks on foundation’s staff development | Less than 3 years | 58 | 2.93 | 3.80 | 0.50 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 5.25 | 5.96 | 0.86 | |

| Foundation’s PR, advertisement, and fundraising | Less than 3 years | 58 | 4.86 | 8.25 | 1.08 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 6.73 | 7.15 | 1.03 | |

| Other duties | Less than 3 years | 58 | 7.34 | 9.37 | 1.23 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 5.96 | 9.13 | 1.32 |

Table 5 displays the results of the t-test analysis of the relationship between the percentage of time spent on PO tasks and years of PO experience. When comparing the percentage of time spent on PO tasks by years of PO experience, POs with more than three years of PO experience were more likely to spend time on review (p = 0.001), audit (p = 0.005), and personnel training (p = 0.017). Those with less than three years’ experience (p < 0.001) spent significantly more time on non-financial support.

T-test results on the relationship between the percentage of time spent on PO tasks and years of PO experience.

| Levene’s test for equality of variances | t-test for equality of means | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. | Sig. | Mean difference | Std. error differences | 95 % Confidence interval of the differences | |||

| (1-Tailed) | (2-Tailed) | Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Program development and modification | Equal variances assumed | 0.10 | 0.75 | −1.39 | 104.00 | 0.08 | 0.17 | −3.36 | 2.42 | −8.15 | 1.44 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.39 | 101.12 | 0.08 | 0.17 | −3.36 | 2.41 | −8.14 | 1.43 | |||

| Grant application recruitment and reception | Equal variances assumed | 2.60 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 104.00 | 0.46 | 0.92 | −0.15 | 1.57 | −3.26 | 2.95 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.10 | 103.88 | 0.46 | 0.92 | −0.15 | 1.54 | −3.21 | 2.91 | |||

| Application review | Equal variances assumed | 6.77 | 0.01 | −3.47 | 104.00 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −6.84 | 1.97 | −10.75 | −2.93 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −3.31 | 72.48 | <0.001 | 0.001*** | −6.84 | 2.07 | −10.95 | −2.72 | |||

| Program monitoring | Equal variances assumed | 4.37 | 0.04 | 1.13 | 104.00 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 1.72 | 1.52 | −1.30 | 4.74 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 1.17 | 100.73 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 1.72 | 1.47 | −1.20 | 4.64 | |||

| Nonfinancial support | Equal variances assumed | 9.69 | 0.00 | 4.23 | 104.00 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 15.04 | 3.56 | 7.99 | 22.10 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 4.39 | 99.64 | <0.001 | <0.001*** | 15.04 | 3.43 | 8.24 | 21.85 | |||

| Audit at the end of the grant | Equal variances assumed | 1.76 | 0.19 | −2.87 | 104.00 | 0.00 | 0.005** | −2.19 | 0.77 | −3.71 | −0.68 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −2.82 | 91.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −2.19 | 0.78 | −3.74 | −0.65 | |||

| Follow-up after the grant | Equal variances assumed | 16.38 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 104.00 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 0.32 | 1.21 | −2.09 | 2.73 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 0.28 | 85.14 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 1.14 | −1.96 | 2.60 | |||

| Managerial tasks on foundation’s administration and supervision | Equal variances assumed | 0.00 | 0.99 | −1.06 | 104.00 | 0.15 | 0.29 | −1.74 | 1.65 | −5.01 | 1.53 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.07 | 103.79 | 0.14 | 0.29 | −1.74 | 1.63 | −4.97 | 1.48 | |||

| Managerial tasks on foundation’s staff development | Equal variances assumed | 1.75 | 0.19 | −2.43 | 104.00 | 0.01 | 0.017* | −2.32 | 0.96 | −4.21 | −0.43 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −2.33 | 76.81 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −2.32 | 0.99 | −4.30 | −0.34 | |||

| Foundation’s PR, advertisement, and fundraising | Equal variances assumed | 0.01 | 0.93 | −1.23 | 104.00 | 0.11 | 0.22 | −1.87 | 1.52 | −4.87 | 1.14 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.25 | 103.75 | 0.11 | 0.22 | −1.87 | 1.50 | −4.83 | 1.10 | |||

| Other duties | Equal variances assumed | 2.42 | 0.12 | 0.77 | 104.00 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 1.39 | 1.81 | −2.20 | 4.97 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 0.77 | 101.21 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 1.39 | 1.80 | −2.19 | 4.96 | |||

-

p < 0.001***, p < 0.01**, p < 0.05*.

5.3 Statistical Analysis of Years of PO Experience and Competencies

For each of the 19 PO competency items, respondents were asked which competencies they considered important, and the number of their selections was used for comparison. From the summary statistics (Table 6), the means of the two groups were 11.2 for less than three years and 13.9 for more than three years.

Group statistics for number of PO competencies selected and length of PO experience.

| Variable | Category | N | Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PO competencies selected | Less than 3 years | 58 | 11.21 | 4.87 | 0.64 |

| More than 3 years | 48 | 13.92 | 4.68 | 0.68 |

The results of the t-test also depicted that respondents with more PO experience selected more competency items as important (p = 0.005) (Table 7).

T-test results on the relationship between the number of PO competencies selected and years of PO experience.

| Levene’s test for equality of variances | t-test for equality of means | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. | Sig. | Mean difference | Std. error differences | 95 % Confidence interval of the differences | |||

| (1-Tailed) | (2-Tailed) | Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Number of PO competencies selected | Equal variances assumed | 0.40 | 0.53 | −2.90 | 104.00 | 0.00 | 0.005** | −2.71 | 0.93 | −4.56 | −0.86 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −2.91 | 101.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.71 | 0.93 | −4.55 | −0.87 | |||

-

p < 0.001***, p < 0.01**, p < 0.05*

6 Discussion for PO HRD and Policy Implication

The literature review has already demonstrated that the responsibilities of POs are diverse, and it is assumed that a certain level of skill and ability is required for such multi-tasking and context-dependent work. The results of this survey supported this condition by revealing the facts of their characteristics. This section discusses the findings related to both PO duties and PO competencies in the Japanese nonprofit sector and provides guidance on how we can apply these findings to develop the government’s HRD policy.

For PO duties, this research found that Japanese POs take multiple responsibilities under the title of PO. In general, while the Japanese nonprofit sector is often strongly associated with charity and volunteerism, this research clearly depicts that POs require a variety of professional knowledge and skills to assume their duties. Regarding the difference in time spent on PO tasks according to years of experience, the results presented that those with less than three years of experience provided more non-financial support to the grantees. This result indicated that a relatively new type of PO population may have emerged, given the diversification of funding resources. In particular, the DDUA articulated the need for POs to strengthen the capacity of grantees and maximize their impact. POs engaged in dormant fund utilization are required to provide both financial (grantmaking) and non-financial support as part of their PO duties. Given that the survey results illustrated that 54.7 % of respondents had less than three years of PO experience, the initiation of dormant fund utilization would have resulted in expanding the PO labor market and diversifying and extending PO roles to include advisers and consultants, which generally require a high level of problem solving and critical thinking skills. Still, some factors that constituted non-financial support included contradictory ideas such as auditing versus relationship building. This analysis highlights the need to strategically consider how to sustain an expanded PO job market and capitalize on the talent connected to this sector via the DDUA.

According to the PO competencies, POCM and other research studies (Carpenter et al. 2015; Orosz 2000), POs must have a variety of competencies. Interestingly, even though PO competencies have not been comprehensively organized and clarified in Japan, the more years of experience a PO has, the more competencies they perceive as crucial. Conversely, the fact that some of the competency items were not selected is also worth considering; further investigation is needed to clarify whether this is due to the difference between PO roles in the U.S., where the POCM was developed, and Japan. Moreover, the relationship between PO duties and competencies in Japanese grantmaking foundations should be examined.

Finally, for the implication for the PO HRD, this research illustrated that POs have few opportunities to participate in training programs that include on-the-job training from colleagues and senior POs in their organizations to enhance their knowledge and skills. Furthermore, this study depicted considerable variation in the amount of grants POs handle. When considering HRD programs, it is necessary to recognize the various patterns that enable each PO to demonstrate its competencies and values while contributing to the achievement of the organization’s mission and vision. However, PO training opportunities remain limited. While a basic training program is offered as a prerequisite under the DDUA, this type of training could be superficial if the characteristics of a PO are not clearly defined. In addition, as Martinie et al. (2019) mentioned, collective learning among the POs is necessary, and professional PO’s community and networks must be needed in Japan. The network may foster social capital among the POs, and Bixler and Springer (2018) indicated that social capital may benefit all levels of government by reducing transaction costs between the nonprofit and public sector agencies because of their cognitive bonding and by gaining access to resources that network membership can provide.

7 Limitations and Future Research

Consideration of PO development policies is not limited to the nonprofit sector but is also related to public policies and practices. The DDUA is a piece of legislation guided by a member of the Diet which will be reviewed every few years. The Cabinet Office is responsible for the oversight of this unique policy which sees the government and Diet members deeply involved in the nonprofit sector. While the findings of this research depict just the beginning of future policy development, it opens a gateway to deepen understanding of Japanese POs’ demographics, roles, and responsibilities among the NPO practitioners, POs, and government officials, which will contribute to improving government-funded HRD strategies. This perspective can apply to other countries with small philanthropic sectors to allow collaboration with government to capacitate NPO human resources. We intend to continue investigating how to deepen the state of POs in Japan and nurture POs who are highly skilled and motivated to lead social change via grantmaking.

This research focused on the length of POs’ work experience. However, the characteristics of POs are not limited to this aspect; organizational characteristics include size, funding area, stakeholders, purpose, and funding resources. As this study could not cover all these aspects, future analyses are needed to capture the status of POs comprehensively. Only some Japanese grantmaking foundations have used dormant deposits. This research suggests that developing PO human resources might improve the nonprofit ecosystem. However, comparing the PO workforces of non-dormant deposit recipients is necessary to evaluate the positive and negative effects of the policy.

References

Baluch, A. M., and H.-G. Ridder. 2021. “Mapping the Research Landscape of Strategic Human Resource Management in Nonprofit Organizations: A Systematic Review and Avenues for Future Research.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50 (3): 598–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020939653.Search in Google Scholar

Ban, C., A. Drahnak-Faller, and M. Towers. 2003. “Human Resource Challenges in Human Service and Community Development Organizations: Recruitment and Retention of Professional Staff.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 23 (2): 133–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X03023002004.Search in Google Scholar

Bixler, R. P., and D. W. Springer. 2018. “Nonprofit Social Capital as an Indicator of a Healthy Nonprofit Sector.” Nonprofit Policy Forum 9 (3): 20180017. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2018-0017.Search in Google Scholar

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. 2018. “Outline of the Act on Utilization of Funds Related to Dormant Deposits to Promote Social Purpose Activities (Tentative).” https://www5.cao.go.jp/kyumin_yokin/english/201803outline_e.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. 2023. “The Partial Revision (Draft) of the Basic Policy on the Utilization of Funds Related to Grants Funded by Dormant Deposits (Basic Policy).” https://public-comment.e-gov.go.jp/servlet/PcmFileDownload?seqNo=0000259358.Search in Google Scholar

Carpenter, H. L., A. Clarke, and R. Gregg. 2013. “Nonprofit Needs Assessment: A Profile of Michigan’s Most Urgent Professional Development Needs.” https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/jcppubs/4/.Search in Google Scholar

Carpenter, H. L., D. Meehan, and S. Pingel. 2015. The Talent Development Platform: Putting People First in Social Change Organizations. Jossey-Bass.10.1002/9781119207542Search in Google Scholar

DeSimone, J. R., and L. A. Roberts. 2023. “Nonprofit Leadership Dispositions.” SN Business & Economics 3 (2): 50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00420-9.Search in Google Scholar

Dillman, D. A., J. D. Smyth, and L. M. Christian. 2014. Internet, Phone, Mail, and mixed-mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed. Wiley.10.1002/9781394260645Search in Google Scholar

Dorothy A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy. 2021. “Program Officer Competency Model.” https://johnsoncenter.org/blog/introducing-the-program-officer-competency-model/.Search in Google Scholar

Genis, M. 2008. “So Many Leadership Programs, so Little Change: Why Many Leadership Development Efforts Fall Short.” Journal for Nonprofit Management 12 (1): 32–40.Search in Google Scholar

Hatsutani, I. 2001. NPO no Seisaku no Riron to Tenkai. [Theory and development of NPO policy]. Osaka University Press. (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Hayashi, Y., and Yamaoka, Y. 1984. Nihon no Zaidan: Sono Fukei to Tenbou [Japanese Foundations: Genealogy and Prospects]. Chuokouronsya. (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Japan Fundraising Association. 2021. Giving Japan 2021. Japan Fundraising Association.Search in Google Scholar

Japan Network for Public Interest Activities. 2019. What is “Utilization of Dormant Deposits”? https://www.janpia.or.jp/en/common/pdf/top_20190816.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Knies, E., P. Boselie, J. Gould-Williams, and W. Vandenabeele. 2024. “Strategic Human Resource Management and Public Sector Performance: Context Matters.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 35 (14): 2432–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1407088.Search in Google Scholar

Makita, T. 2007. Program officer: Jyoseikinhaibun to shakaiteki kachi no sohatsu. [Program officer: Grantmaking and social value creation]. Gakuyo Shobou. (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Martinie, A., J. Love, M. Kelly, K. Dueck, and S. Strunk. 2019. “Below the Waterline: Developing a Transformational Learning Collaborative for Foundation Program Officers.” Foundation Review 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1468.Search in Google Scholar

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Japan. 2022. School Basic Survey. https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/toukei/chousa01/kihon/1267995.htm (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Onishi, T. 2017. “Institutionalizing Japanese Philanthropy Beyond National and Sectoral Borders: Coevolution of Philanthropy and Corporate Philanthropy from the 1970s to 1990s.” International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (2): 697–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9809-x.Search in Google Scholar

Orosz, J. J. 2000. The Insider’s Guide to Grantmaking: How Foundations Find, Fund, and Manage Effective Programs. (T. Makita et al., Trans.). Akashi Shoten. (Original work published 2000). (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Pynes, J. E. 2009. Human Resources Management for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Strategic Approach, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Ronquillo, J. C., W. E. Hein, and H. Carpenter. 2013. “Reviewing the Literature on Leadership in Nonprofit Organizations.” In Human Resource Management in the Nonprofit Sector: Passion, Purpose, and Professionalism, edited by J. B. Ronald, and L. C. Cary, 97–116. Edward Elger Publishing.10.4337/9780857937308.00011Search in Google Scholar

Salamon, L. M., and H. K. Anheier. 1997. Defining the Nonprofit Sector: A cross-national Analysis. Manchester University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Salamon, L. M., H. K. Anheier, S. Toepler, and S. W. Sokolowski. 1999. Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the Nonprofit Sector. Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.Search in Google Scholar

Stahl, R. M. 2013. “Talent Philanthropy: Investing in Nonprofit People to Advance Nonprofit Performance.” The Foundation Review 5 (3): 34–49. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1169.Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, A. J., and K. Kuenzi. 2018. “The Nonprofit Career Ladder: Exploring Career Paths as Leadership Development for Future Nonprofit Executives.” Public Personnel Management 47 (4): 359–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026018783022.Search in Google Scholar

Yamamoto, T. 1998. “Chapter 5: the State and the Nonprofit Sector in Japan.” In The Nonprofit Sector in Japan, edited by T. Yamamoto, 119–44. Manchester University Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction to Nonprofit Policy Forum Special Issue Dedicated to 2023 ARNOVA Asia: Embracing Diversity in Nonprofit Research and Scholarly Community in Asia

- Editorial

- Memorial Essay for Professor Naoto Yamauchi

- Research Articles

- Balancing up, Down, and in: NGO Perspectives During Nepal’s Covid-19 Crisis

- Community Leadership in a Dynamic Perspective: An Exploratory Study of Community Foundations in Hong Kong During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Intersecting Identities: Exploring Worker-Member Perspectives on Government-Certified Worker-Run Social Cooperatives in South Korea

- The Role of Public Education in NGO Advocacy in the Authoritarian Context: A Case Study of Chinese ENGOs

- Policy Brief

- Steering a Restrictive Course: Rebooting China’s Charity Law

- Research Note

- What are Program Officer’s Responsibilities and Competencies? An Exploratory Research on Human Resource Development Policy for Effective Grantmaking

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction to Nonprofit Policy Forum Special Issue Dedicated to 2023 ARNOVA Asia: Embracing Diversity in Nonprofit Research and Scholarly Community in Asia

- Editorial

- Memorial Essay for Professor Naoto Yamauchi

- Research Articles

- Balancing up, Down, and in: NGO Perspectives During Nepal’s Covid-19 Crisis

- Community Leadership in a Dynamic Perspective: An Exploratory Study of Community Foundations in Hong Kong During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Intersecting Identities: Exploring Worker-Member Perspectives on Government-Certified Worker-Run Social Cooperatives in South Korea

- The Role of Public Education in NGO Advocacy in the Authoritarian Context: A Case Study of Chinese ENGOs

- Policy Brief

- Steering a Restrictive Course: Rebooting China’s Charity Law

- Research Note

- What are Program Officer’s Responsibilities and Competencies? An Exploratory Research on Human Resource Development Policy for Effective Grantmaking