Abstract

This study examines the role of public education in the advocacy strategies of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) under authoritarian constraints, using Chinese environmental NGOs (ENGOs) as a case. Despite the increasing use of social media, the advocacy function of public education remains underexplored in such contexts. Drawing on content analysis of 2,961 social media posts from 20 ENGOs and 12 in-depth interviews, we find that ENGOs primarily use social media to disseminate information and gain “safe attention,” while largely underutilizing their interactive potential. Public education is viewed as a long-term goal, but is not strategically integrated into broader advocacy efforts due to limited resources and political sensitivity. Building on attention-based advocacy theory, we propose a strategic attention management approach, recommending that NGOs adopt differentiated strategies: community-based education anchored in offline legitimacy for resource-limited organizations, and large-scale, frame-sensitive communication for those with greater capacity. This study contributes to NGO advocacy literature by conceptualizing public education as a form of indirect advocacy and highlighting the need for nuanced attention strategies in authoritarian contexts.

1 Introduction

Advocacy has been a relatively overlooked area in research on China’s third sector, in contrast to more extensive attention in Western contexts (Almog-Bar and Schmid 2014). This neglect is largely attributed to China’s authoritarian political system, which imposes strict controls on non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (see note a) (Qiaoan and Saxonberg 2022). However, as Guo and Saxton (2020) suggest, the emergence of social media has created new possibilities for NGO advocacy. Social media can help NGOs gain and accumulate public attention, which can then be transformed into advocacy outcomes. This creates a noteworthy tension between the opportunities afforded by social media and the constraints imposed by China’s political environment. Examining how NGOs engage in advocacy within this context can yield important insights and enrich the limited body of literature on advocacy in non-Western, authoritarian settings.

Most research studying NGO advocacy has predominantly focused on direct lobbying strategies aimed at influencing policymakers (Guo and Saxton 2014; Ward et al. 2023). However, this focus may not fully capture the reality of NGO practices in China, where public education is crucial in NGO activities (Zhan and Tang 2013). While public education is considered an important tactic within advocacy strategies (Saxton et al. 2015), this practical trend reflects the unique challenges and opportunities faced by Chinese NGOs in their advocacy efforts.

In this study, we define public education as employed by NGOs as a strategy to enhance public awareness and capacity for engagement on specific issues through systematically disseminating knowledge, developing skills, and promoting behavioral change. This definition aligns with the broader framework proposed by Andrews and Edwards (2005), who classify “public awareness strategy” (including education, media attention, and outreach) as one core strategy employed by environmental organizations. While their terminology emphasizes “awareness,” the concept encompasses strategies targeting the public through different channels.

Relating to NGO advocacy, we argue that public education, as an indirect and long-term advocacy tactic targeting shaping public opinion and raising awareness (Saxton et al. 2015), should gain more attention in an authoritarian context like China since direct approaches are restricted (Huang 2022; Xu and Byrne 2021).

As a result, this research aims to understand public education as a part of advocacy through a case study of Chinese environmental NGOs (ENGOs). We focus on Chinese ENGOs in this research, which have played a vital role in developing China’s third sector as one of the earliest NGO categories emerging in China. Compared to other types of organizations, their stronger engagement and impact in advocacy (Xia 2024), along with their long-standing history and broad spectrum of activities, offer a particularly rich dataset for analysis. More importantly, ENGOs in China have been at the forefront of utilizing public education (Yang and Taylor 2010). Environmental issues often require widespread public awareness and participation to effect change, making them an ideal subject for examining public education strategies.

Based on these gaps, this research aims to answer the following two questions:

RQ1.

What is public education’s role in Chinese ENGOs’ advocacy strategies?

RQ2.

How do Chinese ENGOs conduct public education in the social media age?

The two questions investigate how Chinese ENGOs utilize social media for public education and how it relates to advocacy strategies under authoritarianism. They are designed to be complementary: RQ1 examines how public education is conceptually understood and strategically positioned by practitioners, while RQ2 explores how it is operationalized through actual social media practices. Together, they enable a more nuanced understanding of how public education is both conceptualized and practiced, and how it might be improved to better support advocacy in constrained political environments.

To answer the research questions respectively and collectively, we conducted a qualitative case study by conducting in-depth interviews with ENGO staff and collecting social media data. Practitioner interviews (RQ1) explore the motivations, challenges, and organizational logic behind Chinese ENGOs’ strategies, particularly concerning advocacy, while social media content analysis (RQ2) identifies the specific strategies and content types these organizations employ in public education. By doing so, we can identify not only the concrete public education strategies employed by Chinese ENGOs, but also the underlying organizational rationales and contextual constraints that shape their adoption, especially regarding their integration (or lack thereof) into broader advocacy strategies.

This study finds that while Chinese ENGOs consider public education a core organizational mission and widely use social media for this purpose, it is not well integrated with other advocacy strategies. Social media is mainly used to convey information and seek “safe attention,” but its interactive potential remains underutilized. Organizational resource limitations and perceived political risks shape both strategic intention and actual practices, resulting in a cautious and fragmented approach to public education in advocacy. Based on these findings, we suggest that ENGOs adopt a strategic attention management approach by distinguishing between small-scale, community-based public education aligned with offline advocacy and large-scale, frame-sensitive communication targeting broader public awareness.

This study contributes to the NGO advocacy literature in two ways. First, it theorizes public education as a distinct form of indirect advocacy strategy, particularly relevant under authoritarian constraints where direct lobbying is limited. Drawing on Guo and Zhang’s (2014) explanatory model and Guo and Saxton’s (2010) typology of advocacy strategies, it offers a contextualized framework for understanding how Chinese ENGOs navigate political limitations. Second, the study extends Guo and Saxton’s (2020) attention-based theory by examining how ENGOs strategically manage public attention through social media in pursuit of advocacy goals.

The rest of this paper begins with a literature review on NGO advocacy and public education in China, combining key theoretical perspectives and empirical findings. Drawing on this review, we develop theoretical frameworks for analyzing NGO advocacy strategies in the social media era, with focus on public education initiatives. We then outline our methodological approach, providing detailed explanation of the research design. Finally, we discuss our results in relation to existing literature and our theoretical framework, followed by conclusions highlighting the significance of our findings, acknowledging limitations, and suggesting directions for future research.

2 Literature Review

By reviewing the previous literature on NGO advocacy and advocacy studies in China, we clarify key concepts and highlight the importance of studying public education strategy as a part of advocacy in the Chinese context. Then, we proposed theoretical frameworks based on previous studies for subsequent analysis.

2.1 NGO Advocacy and Strategies

Advocacy is widely recognized as one of the core functions fulfilled by NGOs in civil society (Guo and Saxton 2020, p. 3). Despite its well-acknowledged importance, regarding the definition of NGO advocacy (more frequently referred to as “nonprofit advocacy” in previous literature), there is a theoretical discrepancy between the narrow and broader definition without consensus (Guo and Saxton 2020, p. 4). Some studies adopt a narrower definition focusing on direct lobbying aimed at the government. However, there exists a broader definition of advocacy. This definition states that, in addition to direct lobbying, “grassroots lobbying” aimed at the public and educational efforts aimed at influencing public opinion should also be included in advocacy. While both definitions have merit, the broader perspective more accurately reflects the diverse strategies employed by NGOs, particularly in restrictive political environments. For this study, we adopt Reid’s comprehensive definition of advocacy as “a wide range of expression or action on a cause, i.e. or policy” (Guo and Saxton 2020; Reid 2000, p. 1).

Scholars have developed various frameworks to categorize advocacy strategies, which helps clarify the role of public education in advocacy. One categorization appropriate for this study distinguishes insider and outsider strategies (Gormley and Cymrot 2006; Mosley 2011). The former focuses directly on authoritative agencies, while the latter expands the conflict beyond the decision-makers. Based on this, Guo and Saxton (2010) developed 11 tactics of insider and outsider strategy, where public education is defined as a part of the outsider strategy (Table 1). While Mosley et al. (2023) highlight the importance of organizations’ flexibility in selecting and combining different strategies, current research aims to understand the determinants of current strategy selection and combination (Ward et al. 2023).

Typology of the nonprofit advocacy strategy.

| Insider strategy | Outsider strategy |

|---|---|

| Direct lobbying | Public education |

| Judicial advocacy | Research |

| Administrative advocacy | Media advocacy |

| Expert testimony | Grassroots lobbying |

| Public events and direct action | |

| Coalition building | |

| Voter registration and education |

-

Source: Guo and Saxton 2020.

Among these diverse advocacy strategies, public education deserves particular attention, especially in contexts where direct lobbying approaches may be constrained or less effective. The following sections explore the role of public education as a component of advocacy efforts and its significance in the Chinese context.

2.2 Public Education as an Important Part of Advocacy

In another perspective proposed by Ward et al. (2023), advocacy targeting public opinion can be seen as a venue, except for legislative, administrative, and judicial venues. In this sense, public education can be defined as an advocacy strategy that promotes change by shaping public opinion and mobilizing citizen participation. Empirical studies further confirm that public support is a critical determinant contributing to the success of advocacy efforts (Willems and Beyers 2023).

Although public education is widely recognized as an integral component of advocacy efforts, significant research gaps remain, particularly in the Chinese context. While Guo and Saxton (2014) found that public education strategy is a predominant advocacy tactic in social media, some advocacy studies often fail to identify the advocacy venues being examined, paying little attention to a single strategy or venue (Ward et al. 2023). This gap highlights the need for more focused research on specific advocacy tactics and their effectiveness in different political contexts, especially in authoritarian regimes such as China, where direct lobbying might be seen as challenging state authority.

To evaluate the public education strategy on social media, we draw insights from NGO social media studies and environmental education studies.

In studying social media use by NGOs, Lovejoy and Saxton (2012) provide the most frequently cited theoretical model, referred to as “the hierarchy of engagement model.” Their methodology involves categorizing social media content based on communicative purpose, identifying three primary functions: conveying information, building community, and calling for action. While this model offers a broad framework for understanding NGO social media engagement and was used by scholars for a wide range of research questions (Campbell and Lambright 2020), it requires adaptation for specifically analyzing public education content.

For Chinese ENGOs, public education predominantly takes the form of environmental education. Therefore, we referred to related literature on environmental education. The Tbilisi Declaration of 1977 established the grounding picture of environmental education, pointing out that it is expected to provide opportunities for everyone to cultivate the awareness, knowledge, attitudes, skills, and participation necessary to protect and improve the environment (UNESCO 1978). Based on this, Monroe et al. (2008) developed a framework for environmental education strategies based on purposes, and it can be applied to communication, education, and formal and nonformal initiatives by different participants. This framework includes conveying information, building understanding, improving skills, and enabling sustainable actions. These four categories are not mutually exclusive but rather form a nested relationship, where each subsequent category can build upon and incorporate elements of the previous ones. This framework is particularly relevant to our study of ENGOs’ social media use, as it provides a structured approach to analyzing public education content and strategies in digital environments.

Our analytical framework (Figure 1) integrates both approaches by adopting Lovejoy and Saxton’s (2012) content-coding methodology while using Monroe et al.’s (2008) four educational purposes as the coding categories. This integration is supported by research showing that social media can enhance environmental education by expanding outreach options (Ardoin, Bowers, and Gaillard 2020; Chung et al. 2020; Ho et al. 2018) and can facilitate dialogues that create participatory learning environments (Bortree and Seltzer 2009; Kent and Taylor 2021; Lovejoy and Saxton 2012). This framework allows us to analyze how ENGOs use social media for public education by categorizing content according to its educational purpose.

A framework for analyzing public education on social media. Source: created by the authors, based on Lovejoy and Saxton (2012), and Monroe et al.’s (2008).

2.3 NGO Advocacy in China

For Chinese ENGOs, advocacy has undoubtedly been a long-standing focus due to its political environment (Popović 2020). As indicated by Ward et al. (2023), scholars have studied nonprofit advocacy in three aspects: antecedents, process, and outcome. This research framework is equally applicable to Chinese NGO advocacy. In extant research, most studies focus on antecedents, exploring the factors that shape NGO advocacy behavior. Among these, institutional factors have consistently been considered crucial in influencing Chinese NGO advocacy activities (Li et al. 2017; Zhan and Tang 2013). These studies primarily concentrate on how NGOs manage their relationships with the government to better achieve their goals through direct lobbying strategies. However, in contexts where civil society is perceived as potentially threatening to government authority, only a limited number of trusted advocacy organizations are permitted to participate in policy discussions (Popović 2020). This might explain why many studies focus on case studies of how specific organizations influence policy processes (Xia 2024; Zhang 2017; Zhuang et al. 2022). In these studies, the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) is frequently used to analyze the advocacy process and outcome, highlighting how actors with shared beliefs form coalitions to influence policy change (Li et al. 2024). Li et al. (2024)’s systematic literature review on 112 studies using ACF shows that in China, policy change often results from hierarchical intervention rather than coalition negotiation. This highlights the importance of examining indirect advocacy strategies, such as public education, that are often employed alongside or outside formal policy engagement in constrained institutional settings.

More recently, however, some studies have begun to examine the process dimension of advocacy from the aspect of framing (Dai and Spires 2018; Qiaoan and Saxonberg 2022). For instance, Qiaoan and Saxonberg (2022) apply frame analysis to study the policy advocacy process of environmental organizations in China, emphasizing that successful advocacy strategies require constructing argumentative frames that align with China’s dominant master frames (harmony, nationalism, and developmentalism) to gain recognition and support from decision-makers.

Despite limited performance in direct policy advocacy, Chinese ENGOs are deemed as active in public education (Hsu 2014; Yang and Taylor 2010; Zhan and Tang 2013), especially when public education faces a less restrictive environment than other kinds of activities, such as helping pollution victims (Li et al. 2018). However, as pointed out before, some studies have been limited to a narrow definition of advocacy, excluding public education from the advocacy category, thus neglecting its role in advocacy (Yang and Taylor 2010; Zhan and Tang 2013). For example, Yang and Taylor (2010) differentiate between public education and advocacy, conceptualizing them as separate activities. This narrow conceptualization fails to capture the strategic use of public education as an indirect form of advocacy, potentially underestimating the scope and impact of NGO advocacy activities in China.

Several studies have recognized the significant role of public education as an advocacy strategy. Before the rise of social media, scholars noted that NGOs could conduct advocacy by mobilizing the public through conventional media channels. Zeng (2007) highlighted the fact that NGOs used conventional media to publicly communicate their views, which led to the development of societal discussions and interactions with the government, finally resulting in policy changes. With the advent of social media, NGO advocacy strategies have undergone a significant transformation, offering new opportunities for public education and engagement (Guo and Saxton 2020). Mao (2021) employed the ACF to analyze the policy advocacy roles of two ENGOs in a pneumoconiosis issue, highlighting social media as a crucial platform for influencing public opinion in advocacy. In examining ENGOs’ pathways to influence, Popović (2020) underscored the importance of voice strategy in social media as opposed to impact through direct access to the government. These studies align with Guo and Saxton’s (2020) perspective that social media provides a key venue for shaping public opinion, enabling NGOs to accumulate greater public attention, and leading to the advocacy outcome. Nonetheless, these studies have not adequately emphasized the distinctive role of public education strategy in social media.

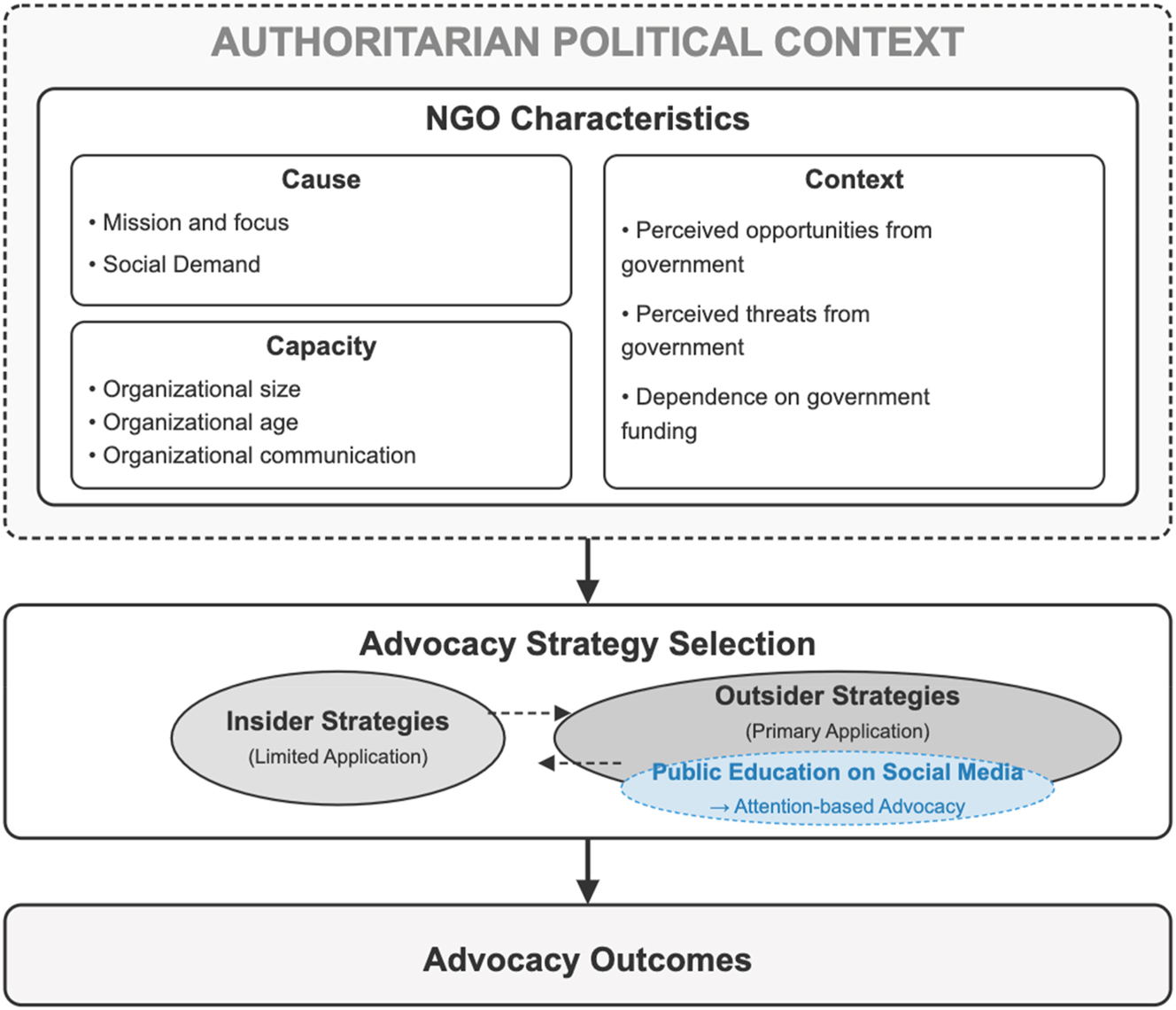

To construct our theoretical framework on NGO advocacy in China with an emphasis on public education, we primarily drew upon seminal studies in the field, including the works of Guo and Saxton (2010, 2020) and Guo and Zhang (2014), which address NGO advocacy strategies, and their application in the social media era.

Regarding the factors that shape advocacy activities, particularly in non-Western contexts, we draw upon Guo and Zhang’s (2014) three-factor explanatory model of nonprofit advocacy, which was developed through research in Singapore, a non-liberal democratic regime. This model provides a systematic framework for understanding how organizational cause, capacity, and contextual factors collectively influence the scope and intensity of advocacy. The validity of this model can be supported by various studies across different contexts. For instance, human service organizations tend to favor insider strategies over outsider strategies, which can be explained through institutional theory and resource dependence theory, relating to capacity and context (Almog-Bar and Schmid 2014). In the Chinese context, Zhan and Tang (2013) found that organizations with more financial resources and better relationships with the government are more likely to strengthen insider strategies. Popović’s (2020) case study revealed that outsider strategies aimed at gaining public support are crucial for successful advocacy by Chinese ENGOs. Dai and Spires (2018) identified three advocacy strategies employed by ENGOs: cultivating stable relationships with the government, gaining media exposure, and choosing appropriate framing strategies. These studies emphasize the importance of moderate, non-confrontational strategies in Chinese NGO advocacy, reflecting the influence of China’s distinct political and social environment on NGO advocacy activities.

In the social media context, Guo and Saxton (2014) found that NPOs’ social media advocacy favored “a mass approach” emphasizing outsider strategies including public education and grassroots lobbying, which means that using social media for advocacy would work less well with direct lobbying. Although it was based in the U.S., it can provide insights into the case in China, where online scrutiny may lead to more restricted social media advocacy.

Drawing from these studies, we posit that Chinese ENGOs likely engage in public education on social media while simultaneously employing complementary outsider strategies to strengthen public opinion influence. These strategies may include conducting research to enhance the credibility of their public education efforts or collaborating with media outlets, as media coverage is recognized as a crucial pathway for ENGOs to gain legitimacy. However, due to China’s stringent control over online discourse, advocacy strategies employed on social networks may not align well with insider strategies.

Finally, Guo and Saxton (2020) proposed an “attention-based theory of nonprofit advocacy”, which emphasizes that attention is the foundation of social media advocacy. This theory comprehensively accounts for the characteristics of social media platforms, examining the factors that influence an organization’s ability to garner attention at both the organizational and message levels. While our study does not quantify these attention metrics, we aim to analyze social media advocacy strategies in the Chinese context through the lens of “attention.”

To conclude, our theoretical framework (Figure 2) integrates multiple complementary perspectives. By combining Guo and Saxton’s (2010) framework of nonprofit advocacy strategies with Guo and Zhang’s (2014) three-factor explanatory model, we propose a comprehensive approach to understanding public education’s role within advocacy efforts. This combination allows us to analyze why this role has developed and offer recommendations for future research directions. Specifically, by referencing Guo and Saxton’s attention-based theory of nonprofit advocacy, we aim to explore how public education functions within advocacy strategies in the context of social media engagement.

An integrated framework for understanding NGO advocacy in China. Source: Created by the authors, based on Guo and Saxton (2014), Guo and Saxton (2010, 2020).

3 Methodology

Due to the under-researched nature of ENGO’s social media advocacy employing public education as a means, a qualitative approach was chosen to address these gaps in the existing research. Then, a case study method is particularly appropriate for this research as it allows for an in-depth exploration of “how” questions and is well-suited to examining under-explored phenomena (Yin 2014). Moreover, as suggested by Campbell and Lambright’s (2020), prior studies on the use of social media by NGOs were primarily quantitative and lacked interpretation, hypothesis, and subsequent examination of outcomes.

We collected our data from two key aspects: in-depth interviews with ENGO staff (RQ1) and social media content by ENGOs (RQ2). Interviews can provide first-hand data that enables an understanding of the formulation and challenges of these strategies from the insider perspective, shedding light on their relationship with other advocacy strategies. Furthermore, leadership is also an important factor in shaping advocacy strategies (He 2023). On the other hand, social media data provides a basic picture of public education strategies. By combining two sets of data, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the social media practices in public education by ENGOs, overcoming the limitations of a single-source data collection method, and enhancing the reliability and persuasiveness of research findings.

3.1 Sampling Method

We adopted purposeful sampling regarding the selection of Chinese ENGOs. We chose purposive sampling for the following reasons. First, as the research questions of this study are open-ended and require in-depth investigation, we aimed to include only active organizations with a certain level of social media presence. Second, purposive sampling allows us to select information-rich cases that can provide valuable insights into the phenomenon of interest. Third, given the exploratory nature of this study, purposive sampling enables us to identify and include ENGOs that exhibit diverse characteristics, such as their focus areas and organizational size.

Based on these considerations, we developed specific criteria for selecting ENGOs for our study. From the perspective of data accessibility, we aim to focus on ENGOs that maintain an active presence on both Weibo and WeChat, the two most prevalent social media platforms in China. Accounts with insufficient activity levels fail to provide adequate data support for the study.

We first checked the overall social media use situation of Chinese ENGOs. First, we referred to the Heyi Institute, a database of Chinese ENGOs, which is one of the most comprehensive NGO directories and has also been used as a data source by other scholars (Zhang and Skoric 2020). Using a VBA program, we collected the names, types, focused issues, and organizational areas of all ENGOs depicted on this map. After eliminating duplicate entries, we compiled a list of 3,043 ENGOs. Of 3,043 ENGOs, 234 (7.6 %) have both WeChat and Weibo accounts. Followers can reflect the size of the organization’s audience and its probable degree of activity (Chen and Fu 2016; Saxton et al. 2015). Since the followers of the WeChat account are not visible to the public, Weibo followers were employed as a selection criterion. 103 organizations are found to have more than 10,000 followers, and 131 organizations have less than 10,000 followers. Then, we selected 10 organizations from each of these two groups for in-depth analysis, resulting in a total of 20 organizations. The selection criteria included the organization’s level of activity and the diversity of environmental issues they focused on, ensuring a representative and varied sample. We prioritized organizations that maintained a regular and up-to-date social media presence, enabling us to closely examine and analyze their social media usage patterns. In addition, our objective was to incorporate organizations that addressed various environmental issues, including climate change, biodiversity conservation, and water resource management. In this way, we can thoroughly comprehend how Chinese ENGOs effectively utilize social media platforms.

Subsequently, we contacted these 20 organizations for interview requests. Ultimately, five organizations agreed to participate in our interviews. Among these five, two organizations had a high level of social media exposure, while the other three had lower visibility on social media platforms.

3.2 Data Collection and Analysis

3.2.1 Social Media Data

First, social media content from the 20 organizations on Weibo and WeChat in the form of microblogs and articles within a specified timeframe in 2023, with Weibo being collected for one month (Nov. 1 – Dec.1) and WeChat for 2 months (Oct.1 – Dec.1). A one-month period can grant enough data and represent the operations of a social media account. We adopted a two-month timeframe for WeChat to gather enough data because the posting frequency of WeChat articles is usually lower than on Weibo. Meanwhile, these two timeframes have been applied by Lovejoy and Saxton (2012) and Xu and Zhang (2022), respectively, adding to their validity. To acquire data, a Python script was used to crawl the social media data. Finally, we collected 2,961 pieces of data.

Sina Weibo and Tencent WeChat are to be studied as they are the two most popular social media sites in China and are generally regarded as utilized by NGOs the most (Wang et al. 2019). Weibo, frequently referred to as “Twitter in China,” is conceptually more like Twitter. Users can post microblogs within 140 characteristics, and other users can either like, share, or comment on these microblogs. WeChat, more acknowledged as an instant message mobile application, provides a public account function and a “personal moment” function being embedded. Organizations and individuals can apply for a public account to publish articles to users who subscribe to the account, and subscribers can read and share content at their “moment”.

For analysis, we employed a mixed-method content analysis, which is frequently adopted by research studying NGO social media use (e.g. Lovejoy and Saxton 2012; Guo and Saxton 2014; Campbell and Lambright 2020). We employed a theory-guided mixed coding approach, integrating deductive and inductive coding strategies (see the framework in Figure 1) (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). Initially, we established primary coding categories based on Monroe et al.’s (2008) environmental education framework (deductive approach); subsequently, within these main categories, we inductively identified specific content types and patterns (inductive approach); finally, we conducted frequency analysis across categories to provide quantitative insights into the prevalence of various strategies.

During the coding process, we developed a detailed codebook with explicit examples and boundary conditions to ensure coding consistency and reliability. We first determined whether content fell within the public education domain based on: 1) whether the content aimed to convey environmental knowledge, cultivate environmental protection skills, or promote environmental behaviors; 2) whether the content targeted the general public rather than specific policy-makers; 3) whether the content contained educational elements (such as explanations, guidance, expositions) rather than purely informational notifications. We excluded the following content categories from our analysis: purely notification-based content (such as event time and venue announcements); partner relationship-building content (including appreciation letters and collaboration invitations); organization management-related content (such as recruitment notices and financial disclosures); and purely organizational promotional content (including organizational introductions and brand promotion materials).

Furthermore, our collected data encompassed both original content and reposted content. Of the 2,961 social media items, original content constituted 67.3 % (1,993 items), while reposted content comprised 32.7 % (968 items). We incorporated reposted content into our analysis because NGOs’ selective reposting itself reflects their public education strategic orientation.

To further enhance coding reliability, we engaged two independent coders to re-code 300 randomly selected items (approximately 10 % of the sample) and calculated the inter-coder reliability coefficient (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.87), indicating the high reliability of the coding results. For inconsistencies that emerged during the coding process, consensus was reached through coder discussions, and the codebook was adjusted accordingly to improve clarity for subsequent coding.

3.2.2 Interviews with ENGOs

We conducted 12 semi-structured interviews with 5 ENGOs from Feb 2024 to May 2024, including the founders and core staff responsible for operating the social media. The interviews were recorded and then coded and transcribed in MAXQDA. To analyze the interview data, we adopted a coding technique from the interpretive grounded theory and initiated an open and axial coding process (Sebastian 2019). Throughout the coding process, we adopted the constant comparative method to ensure the concept’s validity. Finally, we generated the selective coding as our main findings.

4 Findings and Discussion

In this section, we answer the two research questions. We first frame the role of public education as a component of advocacy strategy through the interview data. Then, we presented findings on analyzing the public education strategies on social media used by NGOs. Figure 3 integrates the research findings with our integrated framework as shown in Figure 2.

NGO advocacy in China. Source: Created by the authors.

In discussing the findings, the findings for answering RQ1 also help us interpret the patterns identified in response to RQ2. That is to say, they help explain the gap between strategic intention and implementation, revealing how organizational reasoning and contextual constraints shape communication practices.

4.1 Public Education as a Component of Advocacy Strategy

The interview results showed an ambiguous relationship between public education and advocacy strategies. Overall, we found that social media-based public education effectively expands ENGOs’ influence and reach in the Chinese context. However, the potential of social media to attract attention acts as a double-edged sword for ENGOs: while it offers unprecedented opportunities for outreach in public education practices, as pointed out by Guo and Saxton (2020), it also requires a cautious approach due to perceived risks in an authoritarian context. Interestingly, media advocacy (one of the outsider strategies) can help mitigate these risks. However, offline public education is more effective than its social media counterpart when it comes to aligning well with other advocacy tactics. We discussed the findings within the framework as shown in Figure 2.

4.1.1 Cause

Firstly, interviewees generally view public education as Chinese ENGOs’ core activity and primary organizational objective. This perspective stems from their experience as members of ENGO networks. Regarding public education on social media, organizations primarily adopt two strategic viewpoints, which are complementary but emphasized differently based on the organization’s missions and focus.

Organizations adopting the first viewpoint see social media as an extension of offline public education, perceiving it as an archive of organizational activities. For instance, Organization E documents all its activities on its WeChat public account, facilitating stakeholders’ review of past events. This approach allows organizations to maintain a digital record of their efforts and provide transparency to their supporters and partners. The second viewpoint considers social media as a platform for attracting public attention, viewing it as a tool for expanding influence. This perspective aligns with Guo and Saxton’s (2020) attention-based advocacy framework. Organizations holding this view aim to strategically use social media to increase their visibility and engage with a broader audience.

We still feel that social media is very important. It has changed the way we do things. I don’t see it as just a special channel, but rather as the very way we operate now. (A)

However, despite the potential of public education on social media being recognized, our interview results suggest that this potential seems to have a limited connection to other advocacy strategies and tactics. ENGOs tend to view this influence as a long-term goal rather than directly associating it with specific environmental events. In other words, these organizations tend to consider social media public education separately from their overall advocacy strategies.

We believe public education is a long-term endeavor, and doing project-based science communication on social media can be quite fulfilling. (D)

Connecting social media with any policy-related issue might not be a good choice. Some organizations made such mistakes. (A)

Interestingly, excessive attention on social media often leads some organizations to maintain a cautious attitude. This finding aligns with previous research (Dai and Spires 2018), which indicates that ENGOs need to carefully choose moderate and neutral language to avoid potential risks.

However, this tension between engagement and caution might be mitigated through coverage from traditional media outlets’ social media accounts. ENGOs may find that having their messages filtered through established media channels provides a layer of legitimacy and protection, allowing them to reach their audience while minimizing the risks associated with social media engagement. Yet, for other outsider tactics such as grassroots lobbying, ENGOs tend to disconnect these from their social media strategies.

In contrast, offline public education seems to form closer strategic links with insider advocacy strategies. Organization C shared how community-based offline public education forms closer strategic links with other strategies. Organization C shared its experience of utilizing community-based public education as a starting point to promote waste sorting legislation. Through conducting offline public education activities in hundreds of communities across City S, Organization C gradually established collaborative relationships with local governmental bodies, mainly the street-level and district-level environmental protection departments.

4.1.2 Capacity and Context: Resource Limitation and High Perceived Risk

Secondly, practitioners expressed concerns about conducting public education on social media, further explaining the gap between social media public education and other advocacy strategies. These challenges stem from organizational resource constraints and high perceived risk.

Why do some ENGOs struggle to develop a clear and effective public education strategy on social media? Our findings suggest that the availability of organizational resources, especially human resources, is a key factor shaping their strategic planning and implementation of social media strategies. While social media use by NGOs seems to be cost-effective, our interviews reveal two kinds of costs: human resources and risk costs.

For ENGOs with limited staff and volunteer capacity, maintaining an active social media presence and creating engaging educational content can be highly challenging. As one respondent from Organization E noted, “We often find ourselves overwhelmed by the daily operations and have little time or energy left for strategic thinking or innovation.” In contrast, it is shown that ENGOs with more resources and dedicated social media teams tend to have more formalized strategies and diverse content formats.

It is easier for ENGOs with higher exposure to recruit volunteers to generate social media outputs, most of whom are university students. Nevertheless, this surplus of volunteer resources also necessitates additional efforts from full-time staff, who are well-versed in the organization’s content, to effectively manage and organize.

We have so many volunteers that sometimes I’m even worried about leaving them idle. But the thing is, like 70–80% of the volunteers are short-term. They might not be familiar with the content at times, so we still must spend time teaching them. (B)

Organizations with less social media presence face a considerable barrier in allocating the necessary human resources to maintain an active presence on social media platforms.

In practice, ENGOs lack a clear strategy for public education and face many internal and external challenges. For the initial purpose of ENGOs, the role of social media was to expand the influence and create a more scaled voice. However, they gradually found that this role is quite limited in the competitive cyberspace. Concerns about the limited target audience, shortage of organizational resources, and potential pressure of censorship collectively influenced their social media usage, leading them to primarily extend their offline efforts and amplify their voice within a smaller scope. Yet, although one-way dissemination is prevalent in their social media content, they consider their community-building and dialogue within a small scope successful, highlighting the potential of social media space in terms of civic engagement.

The ENGO staff also expressed significant concerns about the perceived risks associated with censorship and the massive dissemination of information. While NGOs indicated that, as environmental organizations, they are less likely to address highly sensitive topics, the pervasive nature of internet censorship, often referred to as “red lines,” remains a major concern. ENGOs fear unintentionally crossing these boundaries and facing negative repercussions, leading to self-censorship and a conservative approach to social media content creation. Organization B shared an example where a certain organization was suspended by the government due to an unintentional connection with a politically sensitive figure.

On the other hand, while recognizing the efficacy of social media in increasing public awareness, they also expressed concern that the rapid spread of information could amplify even slight mistakes, perhaps leading to irreparable consequences. For example, they acknowledged that the short video form might bring unprecedented success, like the Icebucket Challenge in 2014 (Pressgrove et al. 2018), which experienced an explosive spread on social media worldwide, raising awareness about the disease ALS among the public. Nevertheless, this very potential for viral spread intensifies their concern regarding the inherent risks associated with such strategies. The potential consequences could endanger the organization’s ability to sustain its operations and threaten its long-term viability.

For example, short videos are everywhere these days, like WeChat Video Channels and TikTok. But the thing is, making videos comes with high costs and risks. We need a big enough budget to hire professional teams to create these videos, rather than just shooting something on our phones and posting it. You know, like that CEO of company A who got into trouble after posting a video. This stuff spreads so fast that sometimes you can’t even react before it causes problems.

For ENGOs of our size, actually engaging with anything policy-related on social media feels a bit risky. As your account gains more followers, even though more people are watching, the hidden risks are also increasing. Of course, environmental protection is a relatively safe topic, but sometimes you unknowingly cross a red line. It’s not just about policy sensitivities; the public can be quite sensitive, too. Take the issue of plant-based meat, for example. The mainstream voices on our social media are very opposed to it, and sometimes conspiracy theories get involved.

As a result, these perceived challenges and risks can partly explain why social media public education is driven away from advocacy.

4.2 The Strategy Adopted by Chinese ENGOs in Public Education

In this section, we presented the findings of the content analysis of social media data on public education. Upon identifying the content types and publication strategies, we further examined how these patterns reflect and reinforce the findings derived from the interview data.

First, we identified 1,777 out of 2,961 pieces of social media data that are involved with public education. The high proportion (60 %) of public education content reveals that Chinese ENGOs prioritize public education on social media, consistent with practitioners’ perspectives on this strategy as a core organizational mission. Then, through our theory-guided mixed coding approach, we identified 13 distinct categories of social media public education content, organized under four primary educational purposes as shown in Table 2. This classification system provides a comprehensive taxonomy of ENGOs’ public education strategies on social media, with each category described according to its specific content characteristics and primary educational function.

Social media public education content functions.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Conveying information (62.7 %) | |

|

|

|

| Scientific knowledge dissemination | Sharing environmental scientific knowledge, research outcomes, data analysis, and reports |

| Policy and regulation interpretation | Interpreting environmental policies, laws, regulations, and standards |

| Environmental news reporting | Disseminating current environmental events, news, and updates |

| Nature display | Sharing images or videos of natural landscapes, ecosystems, and biodiversity |

|

|

|

| Building understanding (9.9 %) | |

|

|

|

| Environmental issue analysis | In-depth explanation of environmental problems’ causes, impacts, and connections, including case studies |

| Diverse perspectives sharing | Showing different stakeholders’ (experts, communities, government) views and experiences on environmental issues |

| Historical comparison | Displaying environmental changes over time, promoting understanding of long-term trends |

|

|

|

| Improving skills (7.4 %) | |

|

|

|

| Practical skills instruction | Teaching daily environmental skills like waste sorting, energy and water conservation |

| Environmental monitoring guidance | Introducing environmental monitoring tools and methods, such as guidelines for identifying invasive species |

| Problem assessment and solution | Helping audiences evaluate environmental information and providing steps and methods to solve specific environmental problems |

|

|

|

| Enabling sustainable actions (18.5 %) | |

|

|

|

| Participation opportunities | Recruiting participants for environmental volunteer activities and providing environmental projects and platforms that can be joined |

| Action result demonstration | Showcasing positive outcomes and impacts of environmental actions |

| Collective action organization | Coordinating and organizing collective environmental actions, encouraging long-term environmental behavior through reward mechanisms |

-

Source: Created by the authors.

Based on these coding results, we identified several patterns of public education conducted by ENGOs on social media platforms. First, the predominant focus on conveying information about environmental issues, as evidenced by over 50 % of the content, can be explained by the findings revealed in interviews. On one hand, low-interactivity content (especially “nature display”) helps reduce the demand for human resources while ensuring a baseline level of activity on social media platforms. On the other hand, this strategy reflects a cautious approach to risk management by avoiding dialogic content or opinion-based discussions, organizations minimize the likelihood of triggering sensitive reactions from either the state or the public.

Additionally, ENGOs also focus on improving skills or enabling sustainable actions by promoting various online and offline activities (approximately 25 %). These strategies are regarded as the most promising and effective (Monroe et al. 2008). It is worth noting that although social media inherently guarantees interactivity from a technical standpoint, realizing such interactivity is determined by the nature of the content itself. ENGOs can effectively utilize the interactive characteristics of social media when they focus their efforts on promoting activities. Although only approximately 25 % of content focuses on improving skills or enabling sustainable actions, this proportion reflects how some Chinese ENGOs are attempting to transcend online-offline boundaries and construct more meaningful public engagement models. As illustrated in the interview with Organization C (see the previous section), community-level offline public education can gradually establish connections with policy advocacy strategies. Such online-offline interaction strategies indicate that some environmental organizations are exploring pathways beyond one-way information dissemination, seeking to mobilize and organize actual environmental actions through social media.

However, ENGOs’ investment in building understanding among the public regarding environmental issues is relatively limited. The limited investment of ENGOs in building public understanding, which involves complex environmental issue analyses, stakeholder perspectives, and historical comparisons, is closely related to their social media risk management strategies. Interestingly, the 25 % of content focused on improving skills and enabling sustainable actions precisely illustrates this point. For these organizations, social media content directly linked with offline activities significantly reduces potential risks compared to abstract online discussions. Offline activities, typically pre-approved, inherently possess a certain ‘legitimacy’, while purely online discussions are more likely to touch upon sensitive social and political dimensions. Consequently, these organizations tend to utilize social media as a mobilization and dissemination platform for offline environmental actions, rather than discussing complex environmental issues.

Overall, ENGOs’ approach to public education predominantly focuses on conveying one-way information, with less emphasis on the other three strategies, particularly in terms of fostering deeper understanding. The overreliance on one-way content dissemination also reflects ENGOs’ limited exploitation of social media’s interactivity.

By linking the interview insights (RQ1) with the content analysis results (RQ2), we identified certain alignments and gaps between strategic intentions and actual practices. While ENGOs conceptualize public education as a long-term, risk-conscious, and legitimacy-seeking strategy, this is directly reflected in their overreliance on one-way, low-interaction content such as nature displays or factual reporting. Conversely, areas requiring deeper public engagement, such as issue analysis or stakeholder dialogue, are underrepresented, in line with the organizations’ expressed concerns over resource constraints and political sensitivity. Thus, what ENGOs believe they should do and what they can safely and feasibly do converge in some areas (e.g., promoting offline actions), but diverge sharply in others (e.g., facilitating public discussion online). This interrelation clarifies how strategic reasoning is filtered through institutional and resource realities in practice.

In the next section, we build upon this analysis by discussing how ENGOs manage the tension between outreach and restraint through the lens of strategic attention-seeking in social media advocacy.

4.3 Toward Better Advocacy Outcomes: Strategic Attention Management

Despite ENGO staff members viewing “long-term public awareness raising” as an organizational goal, they rarely incorporate public education strategically into their overall advocacy strategies, although they might adopt the media advocacy tactic. However, a significant gap still exists between public education on social media, as well as the entire outsider strategy, and insider strategies (Guo and Saxton 2010).

To address these problems, we draw on attention-based advocacy theory (Guo and Saxton 2020) to offer strategic recommendations for securing attention in social media–based advocacy, with a focus on public education. Guo and Saxton (2020) emphasize that for advocacy-oriented nonprofits, the key prerequisite for effective action is the ability to gain and sustain public attention, and then leverage attention through online-offline collaboration. However, based on our findings, we argue that NGOs should adopt a more strategic approach to managing attention by distinguishing between two types of public education efforts in the Chinese context: (1) those tightly aligned with offline advocacy to attract targeted, small-scale attention, and (2) those aimed at broader dissemination and innovation to generate large-scale attention independent of immediate policy demands. Recognizing these distinct approaches, organizations can then more effectively leverage public education to gain and manage attention strategically.

As a foundational strategy, we recommend that NGOs with limited resources and low tolerance for political risk prioritize attracting targeted, small-scale attention through public education on social media. This approach begins with offline activities that have received official approval, such as educational events, workshops, or volunteering initiatives, which can then be extended onto social media through pre-event announcements, real-time updates, and post-event summaries or action plans. By embedding social media efforts within the legitimacy of offline activities, organizations can reduce political sensitivity and strengthen their credibility in the digital space. This strategy also allows NGOs to gradually build a highly engaged, mutually supportive community of stakeholders. As shown in recent research (Lai and Wang 2023), community-level voices are central to voluntary action in China. Sharing stories, feedback, and experiences from offline participants fosters a sense of collective identity and trust. Importantly, this approach can activate multiple layers of public education, moving from basic awareness raising to deeper understanding and skill-based participation. While our content analysis revealed a general lack of in-depth issue framing, partly due to perceived risks, community-based strategies offer a relatively safe space for more interactive, dialogic communication. They also require less staff capacity, since content naturally emerges from existing activities. At the same time, such community-building lays the groundwork for broader involvement in policy-related issues, as revealed in a case study by Ji and Han (2023). As Li et al. (2024) also point out, China’s fragmented and multi-level governance allows NGOs and community actors to form localized, issue-based alliances, often in cooperation with government allies. These coalitions are typically low-conflict and focused on concrete policy problems, making them more viable under authoritarian conditions. Although these alliances may not formally resemble traditional advocacy coalitions, they can function similarly at the community level. Community-based public education efforts, grounded in approved offline activities and extended through social media, may thus offer NGOs a practical and low-risk entry point into such informal coalitions.

Building on this foundation, organizations with more robust resources and risk management capacities can adopt a second, more expansive strategy: conducting large-scale, content-driven public education campaigns via social media independent of offline events, even extending to trending platforms like TikTok. While this approach offers greater potential to reach broader audiences, it also entails higher risks due to the lack of offline legitimacy as a buffer. Therefore, particular attention must be paid to message framing. Organizations are advised to focus on politically neutral but substantively engaging themes, such as green lifestyles, environmental practices, or community well-being, topics that align with widely accepted master frames in Chinese society, including harmony, nationalism, and developmentalism (Qiaoan and Saxonberg 2022). When carefully crafted, politically safe content can still facilitate long-term goals by cultivating environmental awareness, shaping collective discourse, and maintaining organizational visibility. As Zhuang et al. (2022) argue, policy influence under authoritarianism often unfolds over decades, and sustained public education is a necessary step along that path.

In sum, we propose a strategic attention management approach that adapts to varying organizational capacities and levels of political risk. While social media offers important opportunities for public education, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its effectiveness depends on how deliberately organizations manage attention, integrate online and offline efforts, and tailor their messaging to the political environment.

5 Conclusions

To conclude, this research examines public education through social media by Chinese ENGOs from two perspectives. First, by in-depth interviews from the organization’s perspective, this study found that public education on social media, though commonly utilized, is not well aligned with other advocacy strategies, except for the media advocacy tactic (Guo and Saxton 2010), which could increase the legitimacy of policy-mentioning. While this aligns with Guo and Saxton’s (2014) study that advocacy on social media mainly involves a mass approach (U.S. case), Chinese ENGOs are more restricted to public education on social media. This means the authoritarian context poses challenges to social media advocacy. Then, our analysis of social media data revealed that the current strategies are quite limited in terms of utilizing dialogue and community-building characteristics to enhance participation in public education, which can be explained by the findings from the interviews.

By adopting the theoretical framework as shown in Figure 2, we further discussed why Chinese ENGOs’ public education via social media fails to align well with other advocacy strategies. We found that although ENGOs consider public education as their mission, they failed to conduct public education better via social media. Then, in terms of capacity and context, it was also found that organizational capacity and perceived risks were the main factors influencing public education via social media. Compared with Guo and Zhang’s (2014) study on the Singapore case using this model, where perceived risks do not have significant impacts on organizations, the findings further reveal that social media may not be an answer to advocacy development under the authoritarian regime, especially on social media. Finally, by referring to Guo and Saxton’s (2020) attention-based theory of nonprofit advocacy, we proposed that Chinese ENGOs should gain strategic attention by separating strategies between getting targeted attention and large-scale attention.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the advocacy literature by theorizing public education as a distinct form of indirect advocacy strategy. In authoritarian contexts where direct lobbying is restricted, public education may serve as a crucial alternative channel for influence. To conceptualize this, we integrate Guo and Saxton’s (2010) typology of advocacy strategies with Guo and Zhang’s (2014) three-factor explanatory model, providing a contextualized framework (Figures 2 and 3) for understanding how public education operates under political constraints. This framework also expands Guo and Saxton’s (2020) attention-based theory by incorporating the challenges Chinese ENGOs face in gaining and managing public attention. Methodologically, this study develops a refined framework for analyzing public education content on social media (Figure 1), combining Lovejoy and Saxton’s (2012) content typology with Monroe et al.’s (2008) model of educational purposes.

Furthermore, this research could also provide valuable insights into NGO advocacy in other countries, particularly where direct lobbying and advocacy efforts are limited. In many contexts, NGOs face significant constraints in their ability to engage in traditional forms of advocacy, such as directly influencing policymakers or participating in formal political processes. In these situations, public education and outsider strategies may become increasingly important tools for NGOs to raise awareness, mobilize support, and indirectly influence decision-making. By examining the experiences of Chinese ENGOs and their use of public education strategies within a constrained political environment, our findings could offer insights and practical suggestions for NGOs operating in similar contexts around the world. This research may also contribute to a broader understanding of how civil society participants adapt their strategies in response to complex political landscapes and advance their causes despite limitations on direct advocacy.

Practically, we pointed out that the public education strategy adopted by ENGOs is quite limited and hasn’t been explored to a strategic level due to internal resource scarcity and the external political environment. Considering public education is an integral part of ENGO missions, we suggest that ENGOs should form a strategic plan and fully exploit the participation function of social media, thus using social media to a level beyond mere one-way dissemination.

While this study sheds light on how Chinese ENGOs conduct public education through social media and their contributions to advocacy literature, several limitations should be acknowledged. Through reflecting on the constraints, this paper will also provide recommendations for further research.

First, although this study focused on public education as an advocacy strategy, it emphasizes analyzing the current situation and its role in NGO advocacy; it did not evaluate the effectiveness of public education. In addition, this study emphasizes a qualitative perspective while analyzing the social media data to understand the research question more deeply. Future research could include the number of shares, reads, and likes of social media messages in the variables section to determine which form of social media public education has the most effective effect.

Second, we applied the framework in environmental education as we consider environmental education by ENGOs as public education within advocacy strategies. Although we believe the conclusions can be applied to other types of Chinese NGOs, it remains necessary to examine the advocacy strategies of some sensitive groups, such as LGBT groups, which face greater challenges on social media platforms (Ren and Gui 2024). These groups often operate in a more constrained environment and may have limited access to certain communication channels, potentially affecting their ability to effectively engage in public education and advocacy efforts.

Notes

a. Previous literature would more frequently use the term “non-profit organizations” (NPOs), while the term “non-governmental organizations” (NGOs) is more prevalent in China. NPOs and NGOs have their distinctions from an academic perspective, but they are interchangeable under most circumstances in practice and most studies. Therefore, the term NPO & NGO will be used interchangeably in this paper while referring to some previous studies. Similarly, “NGO advocacy” and “nonprofit advocacy” will be treated as equivalent terms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their invaluable suggestions and constructive feedback, which significantly improved the quality and clarity of this paper. Their insightful comments and critiques have been instrumental in refining our research and strengthening our arguments. We also deeply appreciate the ARNOVA members who provided thoughtful comments and engaging discussions when we presented an earlier version of this work at the ARNOVA-Asia Conference in July 2023. Their perspectives and questions have greatly contributed to developing our ideas and refining our research approach.

References

Almog-Bar, M., and H. Schmid. 2014. “Advocacy Activities of Nonprofit Human Service Organizations: A Critical Review.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43 (1): 11–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013483212.Search in Google Scholar

Andrews, K., and B. Edwards. 2005. “The Organizational Structure of Local Environmentalism.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 10 (2): 213–34.10.17813/maiq.10.2.028028u600744073Search in Google Scholar

Ardoin, N. M., A. W. Bowers, and E. Gaillard. 2020. “Environmental Education Outcomes for Conservation: A Systematic Review.” Biological Conservation 241: 108224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224.Search in Google Scholar

Bortree, D. S., and T. Seltzer. 2009. “Dialogic Strategies and Outcomes: An Analysis of Environmental Advocacy Groups’ Facebook Profiles.” Public Relations Review 35 (3): 317–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, D. A., and K. T. Lambright. 2020. “Terms of Engagement: Facebook and Twitter Use Among Nonprofit Human Service Organizations.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 30 (4): 545–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21403.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Y.-R. R., and J. S. Fu. 2016. “How to Be Heard on Microblogs? Nonprofit Organizations’ Follower Networks and Post Features for Information Diffusion in China.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (7): 978–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2015.1086013.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, C.-H., D. K. W. Chiu, K. K. W. Ho, and C. H. Au. 2020. “Applying Social Media to Environmental Education: Is it More Impactful Than Traditional Media?” Information Discovery and Delivery 48 (4): 255–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/idd-04-2020-0047.Search in Google Scholar

Dai, J., and A. J. Spires. 2018. “Advocacy in an Authoritarian State: How Grassroots Environmental NGOs Influence Local Governments in China.” The China Journal 79: 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1086/693440.Search in Google Scholar

Gormley, W. T., and H. Cymrot. 2006. “The Strategic Choices of Child Advocacy Groups.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 35 (1): 102–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764005282484.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, C., and G. D. Saxton. 2010. “Voice-In, Voice-Out: Constituent Participation and Nonprofit Advocacy.” Nonprofit Policy Forum, https://doi.org/10.2202/2154-3348.1000.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, C., and G. D. Saxton. 2014. “Tweeting Social Change: How Social Media Are Changing Nonprofit Advocacy.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43 (1): 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012471585.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, C., and G. D. Saxton. 2020. The Quest for Attention: Nonprofit Advocacy in a Social Media Age. Stanford Business Books, an imprint of Stanford University Press.10.1515/9781503613089Search in Google Scholar

Guo, C., and Z. Zhang. 2014. “Understanding Nonprofit Advocacy in Non-western Settings: A Framework and Empirical Evidence from Singapore.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 25 (5): 1151–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9468-8.Search in Google Scholar

He, C. 2023. “The Impact of Government Relationship on Operations for Chinese Environmental NGOs.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 34 (4): 872–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00352-8.Search in Google Scholar

Ho, K. K. W., T. Takagi, S. Ye, C. Au, and D. Chiu. 2018. “Pre-ICIS Workshop Proceedings 2018.” In The Use of Social Media for Engaging People with Environmentally Friendly Lifestyle: A Conceptual Model. Association for Information Systems.Search in Google Scholar

Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.Search in Google Scholar

Hsu, J. Y. J. 2014. “Chinese Non-governmental Organisations and Civil Society: A Review of the Literature: NGOs and Civil Society in China.” Geography Compass 8 (2): 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12117.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, S. 2022. “NGO as Sympathy Vendor or Public Advocate? A Case Study of NGOs’ Participation in Internet Fundraising Campaigns in China.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 33 (5): 1064–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00463-w.Search in Google Scholar

Ji, W., and Q. Han. 2023. “社会组织何以能推动公共政策改善? Z市孤独症儿童随班就读“零拒绝”政策倡导案例分析 [How Can Social Organizations Promote Public Policy Improvement? A Case Study on Advocacy for the “Zero Rejection” Policy on Inclusive Education for Children with Autism in Z City].” 都市社会工作研究 13: 133–53.Search in Google Scholar

Kent, M. L., and M. Taylor. 2021. “Fostering Dialogic Engagement: Toward an Architecture of Social Media for Social Change.” Social Media + Society 7 (1): 205630512098446. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984462.Search in Google Scholar

Lai, T., and W. Wang. 2023. “Attribution of Community Emergency Volunteer Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study of Community Residents in Shanghai, China.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 34 (2): 239–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00448-1.Search in Google Scholar

Li, H., C. W. Lo, and S. Tang. 2017. “Nonprofit Policy Advocacy under Authoritarianism.” Public Administration Review 77 (1): 103–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12585.Search in Google Scholar

Li, W., J. Pierce, F. Chen, and F. Wang. 2024. “The Politics of China’s Policy Processes: A Comparative Review of the Advocacy Coalition Framework’s Applications to Mainland China.” Politics & Policy 52 (4), https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12574.Search in Google Scholar

Li, H., S.-Y. Tang, and C. W.-H. Lo. 2018. “The Institutional Antecedents of Managerial Networking in Chinese Environmental NGOs.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47 (2): 325–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764017747733.Search in Google Scholar

Lovejoy, K., and G. D. Saxton. 2012. “Information, Community, and Action: How Nonprofit Organizations Use Social Media*.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17 (3): 337–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01576.x.Search in Google Scholar

Mao, Y. 2021. “从环境议题看社会组织的政策倡导角色:基于倡导联盟框架的分析 [The Policy Advocacy Role of Social Organizations in Environmental Issues: An Analysis Based on the Advocacy Coalition Framework].” 青少年研究与实践 36 (3): 71–80.Search in Google Scholar

Monroe, M. C., E. Andrews, and K. Biedenweg. 2008. “A Framework for Environmental Education Strategies.” Applied Environmental Education and Communication 6 (3–4): 205–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15330150801944416.Search in Google Scholar

Mosley, J. E. 2011. “Institutionalization, Privatization, and Political Opportunity: What Tactical Choices Reveal about the Policy Advocacy of Human Service Nonprofits.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40 (3): 435–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009346335.Search in Google Scholar

Mosley, J. E., D. F. Suárez, and H. Hwang. 2023. “Conceptualizing Organizational Advocacy across the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector: Goals, Tactics, and Motivation.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 52 (1_suppl): 187S–211S. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221103247.Search in Google Scholar

Popović, E. 2020. “Advocacy Groups in China’s Environmental Policymaking: Pathways to Influence.” Journal of Environmental Management 261: 109928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109928.Search in Google Scholar

Pressgrove, G., B. W. McKeever, and S. M. Jang. 2018. “What Is Contagious? Exploring Why Content Goes Viral on Twitter: A Case Study of the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge.” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 23 (1): e1586. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1586.Search in Google Scholar

Qiaoan, R., and S. Saxonberg. 2022. “Framing in the Authoritarian Context: Policy Advocacy by Environmental Movement Organisations in China.” Social Movement Studies 24 (1): 22–38, https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2022.2144202.Search in Google Scholar

Reid, E. (2000). Structuring the Inquiry into Advocacy (E. Reid, Ed.; Vol. 1). The Urban Institute.Search in Google Scholar

Ren, X., and T. Gui. 2024. “Where the Rainbow Rises: The Strategic Adaptations of China’s LGBT NGOs to Restricted Civic Space.” Journal of Contemporary China 33 (145): 101–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2022.2131378.Search in Google Scholar

Saxton, G. D., J. N. Niyirora, C. Guo, and R. D. Waters. 2015. “#AdvocatingForChange: The Strategic Use of Hashtags in Social Media Advocacy.” Advances in Social Work 16 (1): 154–69.10.18060/17952Search in Google Scholar

Sebastian, K. 2019. “Distinguishing between the Strains Grounded Theory.” Journal for Social Thought 3 (1).Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 1978. Final Report: Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education, Tbilisi (USSR), 14–26 October 1977. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000032763 Search in Google Scholar

Wang, X., J. Zhang, and L. Luo. 2019. “中国公益组织的社会化媒体使用及效果研究 [Chinese NPOs’Social Media Use and Impact Measurement].” 北京航空航天大学学报(社会科学版) 32 (6): 59–68.Search in Google Scholar

Ward, K. D., D. P. Mason, G. Park, and R. Fyall. 2023. “Exploring Nonprofit Advocacy Research Methods and Design: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 52 (5): 1210–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221131747.Search in Google Scholar

Willems, E., and J. Beyers. 2023. “Public Support and Advocacy Success across the Legislative Process.” European Journal of Political Research 62 (2): 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12544.Search in Google Scholar

Xia, Y. 2024. “Environmental Advocacy in a Globalising China: Non-governmental Organisation Engagement with the Green Belt and Road Initiative.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 54 (4): 667–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2023.2267062.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, J., and J. Byrne. 2021. “Explaining the Evolution of China’s Government–Environmental NGO Relations since the 1990s: A Conceptual Framework and Case Study.” Asian Studies Review 45 (4): 615–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2020.1828824.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, J., and H. Zhang. 2022. “Activating beyond Informing: Action-Oriented Utilization of WeChat by Chinese Environmental NGOs.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (7): 3776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073776.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, A., and M. Taylor. 2010. “Relationship-building by Chinese ENGOs’ Websites: Education, Not Activation.” Public Relations Review 36 (4): 342–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.07.001.Search in Google Scholar

Yin, R. K. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Zeng, F. 2007. “环保NGO的议题建构与公共表达: 以自然之友建构保护藏羚羊议题为个案 [Media Agenda Building and Public Expression in NGO:A Case Study of Tibetan Antelopes Protection in China].” 国际新闻界 2007 (10): 14–8.Search in Google Scholar

Zhan, X., and S.-Y. Tang. 2013. “Political Opportunities, Resource Constraints and Policy Adocacy of Environmental NGOs in China.” Public Administration 91 (2): 381–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02011.x.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, C. 2017. “Nothing about Us without Us’: The Emerging Disability Movement and Advocacy in China.” Disability & Society 32 (7): 1096–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1321229.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, N., and M. M. Skoric. 2020. “Getting Their Voice Heard: Chinese Environmental NGO’s Weibo Activity and Information Sharing.” Environmental Communication 14 (6): 844–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2020.1758184.Search in Google Scholar

Zhuang, H., J. A. Zinda, and J. P. Lassoie. 2022. ““Crouching Tiger, Hidden Power”: A 25-year Strategic Advocacy Voyage of an Environmental NGO in China.” The Journal of Environment & Development 31 (4): 331–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/10704965221121743.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction to Nonprofit Policy Forum Special Issue Dedicated to 2023 ARNOVA Asia: Embracing Diversity in Nonprofit Research and Scholarly Community in Asia

- Editorial

- Memorial Essay for Professor Naoto Yamauchi

- Research Articles

- Balancing up, Down, and in: NGO Perspectives During Nepal’s Covid-19 Crisis

- Community Leadership in a Dynamic Perspective: An Exploratory Study of Community Foundations in Hong Kong During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Intersecting Identities: Exploring Worker-Member Perspectives on Government-Certified Worker-Run Social Cooperatives in South Korea

- The Role of Public Education in NGO Advocacy in the Authoritarian Context: A Case Study of Chinese ENGOs

- Policy Brief

- Steering a Restrictive Course: Rebooting China’s Charity Law

- Research Note

- What are Program Officer’s Responsibilities and Competencies? An Exploratory Research on Human Resource Development Policy for Effective Grantmaking

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction to Nonprofit Policy Forum Special Issue Dedicated to 2023 ARNOVA Asia: Embracing Diversity in Nonprofit Research and Scholarly Community in Asia

- Editorial

- Memorial Essay for Professor Naoto Yamauchi

- Research Articles

- Balancing up, Down, and in: NGO Perspectives During Nepal’s Covid-19 Crisis

- Community Leadership in a Dynamic Perspective: An Exploratory Study of Community Foundations in Hong Kong During the COVID-19 Pandemic