Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and debilitating autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS) in which a CNS-driven immune response destroys myelin, leading to wide range of symptoms including numbness and tingling, vision problems, mobility impairment, etc. Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells in the CNS, which are generated from oligodendroglial progenitor cells (OPCs) via differentiation. However, for multiple reasons, OPCs fail to differentiate to oligodendrocytes in MS and as a result, stimulating the differentiation of OPCs to oligodendrocytes is considered beneficial for MS. The β-hydroxy β-methylbutyrate (HMB) is a widely-used muscle-building supplement in human and recently it has been shown that low-dose HMB is capable of stimulating the differentiation of cultured OPCs to oligodendrocytes for remyelination. Moreover, other causes of autoimmune demyelination are the decrease and/or suppression of Foxp3-expressing anti-autoimmune regulatory T cells (Tregs) and upregulation of autoimmune T-helper 1(Th1) and Th17 cells. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is an animal model of MS in which the autoimmune demyelination is nicely visible. It has been reported that in EAE mice, oral HMB upregulates Tregs and decreases Th1 and Th17 responses, leading to remyelination in the CNS. Here, we analyze these newly-described features of HMB, highlighting the putative promyelinating nature of this supplement.

Introduction

Myelin sheath is basically a lipid rich plasma membrane 1], [2], [3 for the formation of multi-layered coatings around the axon [4]. Therefore, myelin coatings keep a neuron healthy and preserve the conduction of electrical impulse through the axon. It is believed that the ideal lining by myelin is contingent on the types and proportions of lipids and proteins and myelin water fraction. Neurological dysfunction occurs when the myelin sheath is harmed and axonal padding is disturbed, resulting in the slowing down of nerve impulses along the axon. Despite intense investigations, no effective drug is available to take care of demyelination.

HMB is a popular nutritional supplement among the health and fitness community for its potential to positively modulate exercise routine and muscle growth. In addition to helping the body-building community, HMB intake is known to improve protein balance and reduce muscle wasting in cancer [5], acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [6], and aging [7]. Recent studies have identified neuroprotective functions of HMB in which HMB stimulates the maturation of myelin progenitor cells to myelin forming cells. In an animal model of autoimmune demyelination as well, oral administration of HMB stimulates remyelination of the CNS.

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic autoimmune disease with demyelination, neuronal loss, and scarring, disables around 2.8 million people worldwide usually between the ages 18–40 8], [9], [10], [11. It is known for decades that females are twice more susceptible than males to be affected by MS 12], [13], [14. As women are more prone to MS, pregnancy is a huge concern when related to MS [15]. The underlying cause of MS is not known, but the reasons are thought to be in connection with genetic and environmental factors [10, 11]. However, inflammation in the CNS plays an important role 16], [17], [18], [19], [20, which causes various motor, sensory, and visual symptoms. Cognitive impairment is likely to occur in people with MS, and that compromises the ability to do day-to-day functions. The targets of MS attacks are the myelinated axons in the CNS, and it can cause varying degrees of damage to both myelin and axons [3, 21, 22].

Diagnosis of MS can be performed with the following clinical tools: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), evoked potentials, and monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid. MRI testing has become the primary diagnostic and monitoring device for MS [23]. Evoked potentials evaluate the efferent and afferent CNS circuits. There are three main types of MS: relapsing-remitting, secondary progressive, or primary progressive disease [24]. Most people exhibit relapsing-remitting MS, which has alternating periods of dysfunction and then having relative stability. Every relapse causes the MS to intensify. During each stability stage, the neurons rebuild their myelin sheath, but it does not go back to the normal way. Each relapse also exhibits different and new symptoms. Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis is usually what relapsing-remitting MS patients progress into years after their diagnosis [25, 26]. It is when the disease starts to become progressive without any relapses. Only a small portion of individuals are diagnosed with primary progressive multiple sclerosis phenotype [26]. This is when there is a slow progression of MS apparent from the start of the disease. These individuals do not have moments of stability as myelin-producing cells and myelin sheaths are being constantly attacked.

Oligodendrocytes and oligodendroglial progenitor cells (OPC)

Oligodendrocytes (OLs) are a very special type of cells in the CNS that form myelin. OLs are characterized or identified by specific markers such as myelin basic protein (MBP), proteolipid protein (PLP), 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), and galactocerebroside (GalC) 27], [28], [29. These are small cell bodies of approximately 6–8 μm in diameter that have nuclei containing a large number of chromatins. Also, cellular extensions of OLs lack fibers and are filled with cytoplasmic granules. Most OLs are capable of making about 20–60 myelinating processes with lengths between about 20 and 200 µm [30]. Myelin is a lipid membrane that wraps and insulates axons, which allows for fast-working action potentials. OLs induce many sodium channels along the axon at the nodes of Ranvier to start the saltatory conductions [31]. On the other hand, oligodendroglial progenitor cells (OPCs) are the cells that generate OLs. OPCs are also called NG2 cells or polydendrocytes because these cells express NG2 proteoglycan on the surface and have many processes [32]. While NG2 is known to stimulate the proliferation of OPC via increasing growth factor signaling [33], another cell surface ganglioside molecule A2B5 probably increases the self-renewal property of these cells [34]. Several studies have demonstrated that OPCs have an important role in remyelination, as these cells have a unique ability to proliferate and differentiate after demyelination following any insult and injury. Therefore, OPCs are key to understanding how myelin production occurs and how regeneration is able to occur in myelin when destruction happens.

Demyelination in MS

From a pathological standpoint, MS is identified by the presence of diffuse, discrete demyelinated areas, called plaques. Demyelination involves myelin lamella stripping and using phagocytes to remove myelin fragments [35]. During demyelination, the ionic conduction through the neuron is reduced, ultimately leading to axonal loss. Therefore, demyelination is assumed as an important pathological hallmark of MS [36]. There are different mechanisms involved in the demyelination process in MS. MS involves autoreactive T cells entering the CNS to start an inflammatory cascade triggering demyelination and axonal loss [37]. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which are important for defense against pathogens; B cells, a type of white blood cell making antibodies; and macrophages, a type of white blood cell that surrounds and kills microorganisms, are major components of the inflammatory infiltrate into the lesions of both MS and EAE [38]. Research on demyelination in MS has been performed on animals such as mice by inducing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an autoimmune model of MS 39], [40], [41. Several studies from EAE animals have shown that nitric oxide and different proinflammatory cytokines play an important role in demyelination [22, 41, 42]. Although nitric oxide has many beneficial functions, excessive nitric oxide produced during inflammatory insults is toxic for myelin and myelin-producing OLs [43, 44].

Role of OPC in remyelination

Myelination is a sequence of events that include the proliferation and the movement of OPCs in white matter tracts. OPCs are abundant in the CNS and during any insult or injury, OPCs are recruited to the site of injury with an ultimate goal to remyelinate demyelinated axons. However, OPCs expressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGF-Rα), ganglioside A2B5, proteoglycan NG2, polysialic acid-neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM), and fatty-acid-binding protein (FABP)7, are usually proliferative cells. OPCs generate OLs via maturation when OPCs acquire an elaborate morphology and lose their capacity of proliferation and migration [45, 46]. Neurobiologists have classified maturation of OPCs into different steps such as late OPC (preoligodendrocytes), immature OL (pre-myelinating) and mature OL (myelinating) [45, 46].

In MS lesions, there are few surviving OLs that can contribute to remyelination. Therefore, OPCs need to be recruited and differentiated to OLs in chronic MS lesions. If the recruitment process is too slow or inefficient, remyelination does not occur. If too slow, the OPCs reach the axons after the ‘remyelination-permissive window’ and cannot differentiate into OLs [47]. If there is not enough OPCs, the density in the lesions is below the threshold required for differentiation. Because OPC proliferation in MS lesions is little, that is mainly why there are repeated OPC differentiation [48]. The repeated demyelination/remyelination decreases the lesional OPC pool. In MS, OLs not being capable of remyelinating enough correlates with the progression of the disease.

Muscle-building supplement HMB

Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) is used as a supplement for muscle-building for physically active people. HMB is found in local GNC stores as a body-building supplement. Bodybuilders consume HMB regularly to increase muscle size and muscle strength while also exercising, and to better exercise performance. HMB is known to decrease muscle protein degradation [49]. Moreover, HMB is able to increase the integrity of the myocyte cell membrane, sarcolemma [49] and activate the mTOR kinase pathway [50]. The mTOR kinase pathway is a protein kinase that controls mRNA translation efficiency. HMB improves the proliferation of muscle stem cells [49]. There is also evidence that HMB lowers the expression level of TNFα [51], a marker of inflammatory responses that occur during the recovery period. Studies have shown that HMB does have an effect on muscle strength [52]. It has also been described that HMB is more effective in untrained individuals who had periods of high physical stress. That is because people with training already have adapted to training, so the effects are reduced. Because of multiple reasons such as the increase of satellite cells and in cholesterol synthesis, there is increased tissue repair in individuals. As HMB has qualities such as resistance to fatigue and regenerative capacity [53], it is better for individuals with illnesses that cause motor problems and fatigue to use this as a supplement. HMB treatment leads to increase in fat-free mass associated with decrease in fat mass in a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study among 42 highly-trained combat sports athletes [54]. HMB does not exhibit any side effect even after long-term use. Therefore, HMB is considered as a safe supplement in humans.

Maturation of OPC by HMB

Normally, OPCs should differentiate into OLs. Yet in MS, OPCs fail to differentiate into OLs [31]. For this reason, there could be therapeutic benefits for MS if there was an increase in the maturation of OPCs to OLs by any nontoxic compound/drug. HMB has been tested to study if it stimulates the maturation of OPCs into OLs. Increase in oligodendrocyte markers such as MBP, PLP, MOG, and CNPase along with subsequent reduction of NG2 and A2B5, markers of OPCs, is a reliable way to study the maturation of OPCs to OLs [27, 55], [56], [57. HMB treatment rapidly upregulates MBP and PLP and downregulates NG2 and A2B5 in OPCs, indicating differentiation into OLs [57].

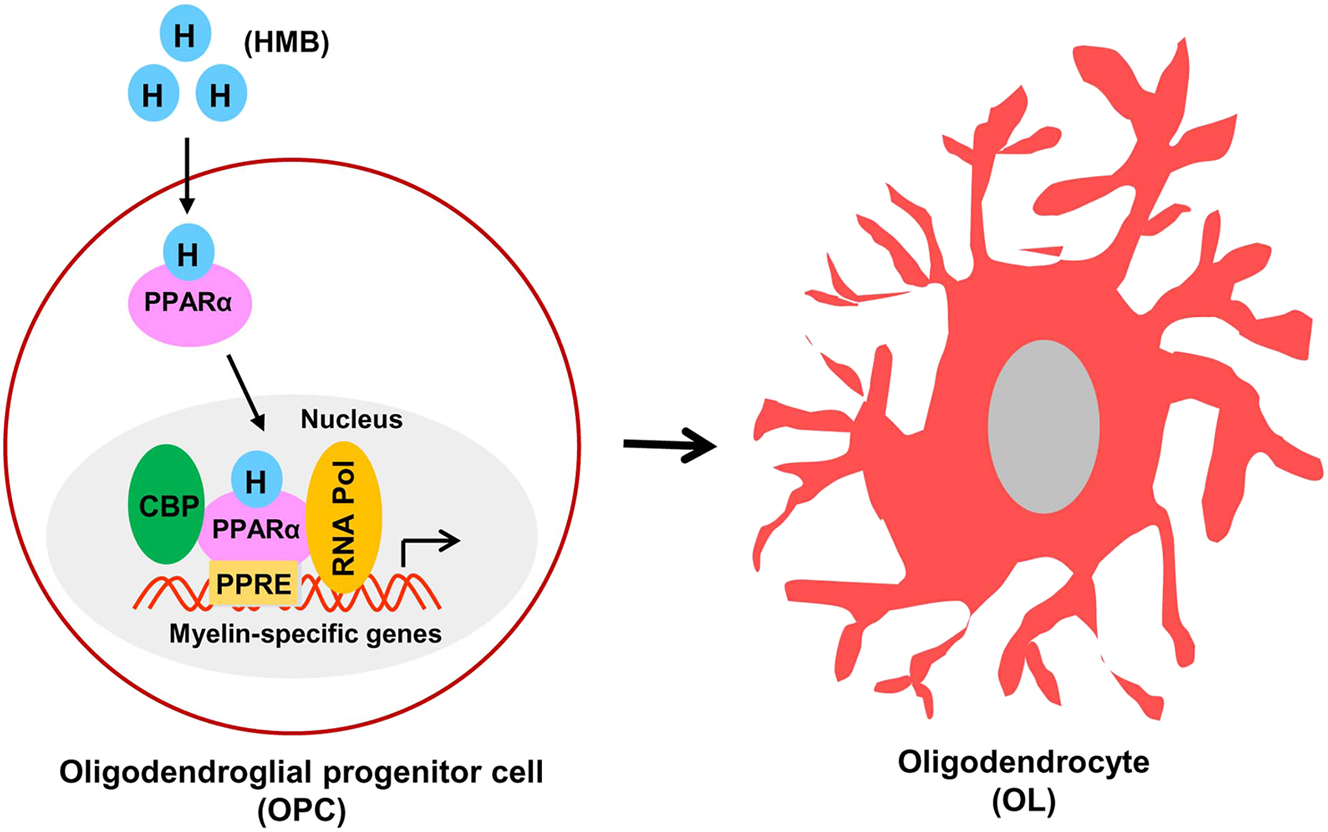

While investigating underlying mechanisms, Jana et al. [57] have analyzed gene promoters of different OPC- and OL-associated markers and seen the presence of one or more peroxisome proliferator responsive element (PPRE) in the promoters of MBP, PLP and MOG genes, but not NG2 and A2B5 genes. Although the major role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), nuclear hormone receptor family of transcription factors [58, 59], is to control the metabolism of lipids [60, 61], one recent study has shown the involvement of PPARα in HMB-mediated differentiation of OPCs [57]. Interestingly, HMB binds to the ligand-binding domain of PPARα [62] and in cultured OPCs, it leads to nuclear localization of PPARα, but not PPARβ [57]. The role of PPARα is further validated by the results that PPARα agonist GW7647, but neither PPARβ agonist GW0742 nor PPARγ agonist GW1929, stimulates the maturation of OPCs into OLs [57]. Similarly, PPARα antagonist GW6471, but neither PPARβ antagonist GSK0660 nor PPARγ antagonist GW9662, inhibits HMB-induced maturation of OPCs. Accordingly, HMB remains unable to stimulate the differentiation of OPCs isolated from PPARα−/− mice into OLs [57]. It has been also shown that HMB treatment causes the recruitment of PPARα, but neither PPARβ nor PPARγ, in cultured OPCs. Although there are two prominent histone acetyl transferases (p300 and CREB-binding protein or CBP) 63], [64], [65, HMB retains CBP, but not p300, to the PPRE of myelin gene promoter in OPCs [57]. It has been also delineated that a complex of PPARα, CBP and RNA polymerase II is involved in the transcription of myelin genes in HMB-treated OPCs (Figure 1). Therefore, this newly-described promyelinating function of HMB is dependent on the transcriptional activity of PPARα (Figure 1).

Maturation of OPC to OL by HMB. HMB stimulates the translocation of PPARα from cytoplasm to nucleus, which then binds to PPRE present in the promoter of myelin-specific genes. CBP and RNA polymerase also bind to PPRE to drive the transcription of myelin-specific proteins, ultimately leading to the maturation to OL.

Stimulation of remyelination in an animal model of MS by HMB

As demyelination in the CNS is a major feature in MS [66], and EAE serves as an animal model of MS [17, 67, 68], studies have also tested the effect of HMB on demyelination and the disease process of EAE. In MS as well as EAE, spinal cord is affected the most and accordingly, myelin staining by Luxol fast blue identifies widespread demyelination zones in the white matter of EAE mice [69, 70]. However, oral HMB markedly improves the myelin level in spinal cord of EAE mice [71]. The mRNA levels of myelin markers such as MBP and PLP is also normalized in the spinal cord of EAE mice by HMB treatment [71]. The ultimate goal of neuroprotective therapies of MS is to decrease functional impairments. Accordingly, oral HMB has been shown to suppresses clinical symptoms of EAE in mice [71]. Since the autoimmune component plays an important role in the pathogenesis of EAE in mice, the effect of HMB has been also tested on immunomodulatory subtype of T lymphocytes in EAE. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are viewed as a necessary immunomodulatory subtype of T lymphocytes, which become defective during the autoimmune attacks 72], [73], [74. It is also believed that due to downregulation of Tregs, there is upregulation of effector Th1 and Th17 cells in EAE and MS 75], [76], [77. Interestingly, oral HMB also stimulates the anti-autoimmune Treg response and attenuates the autoimmune Th1 and Th17 responses in EAE mice [71].

Conclusions

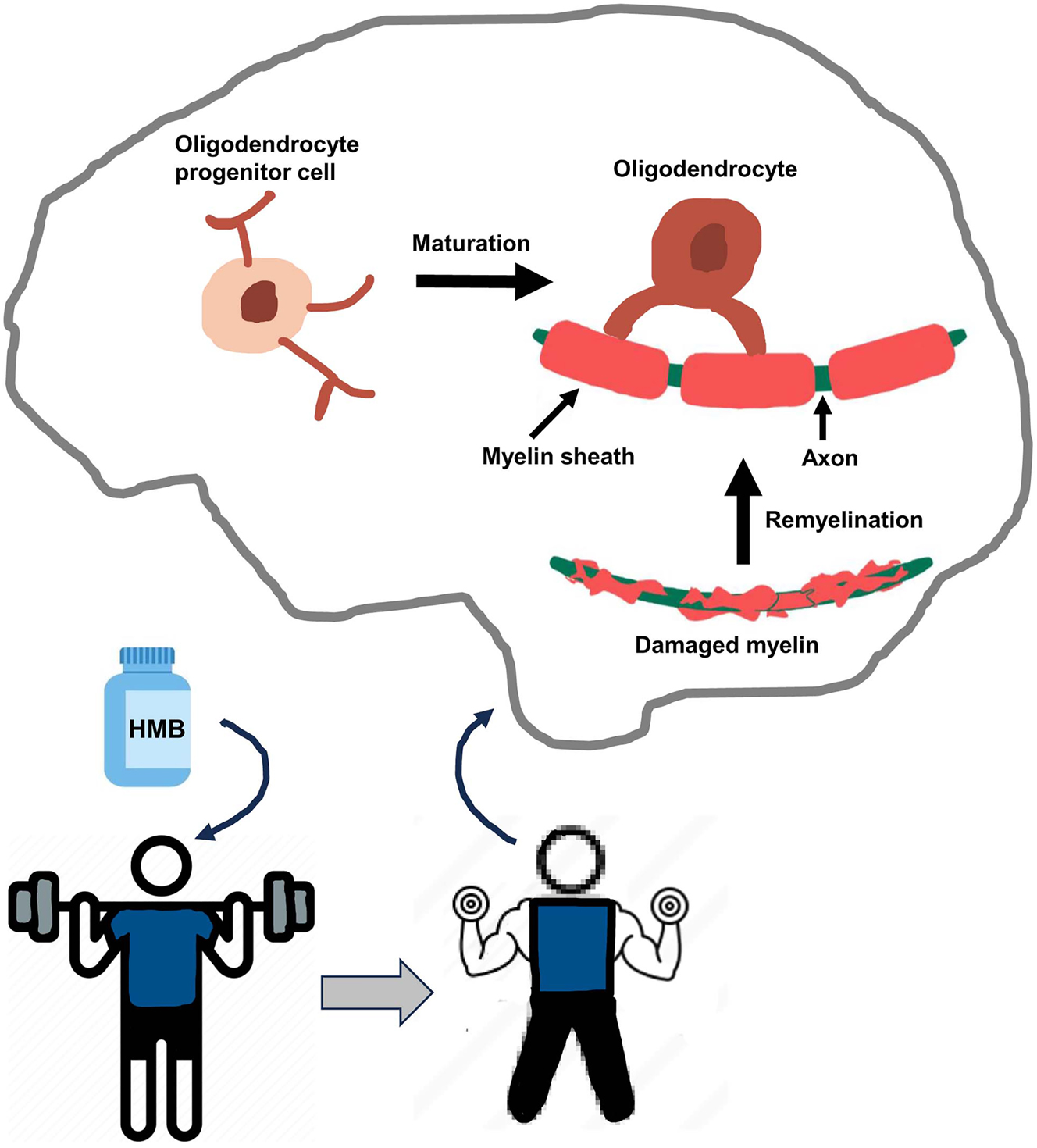

Currently, there is no effective treatment for remyelination and as a result, available treatments only control demyelination symptoms of MS to a certain extent to provide some relief from the pain and suffering due to this disease. Furthermore, FDA has not yet approved any medicine for treating primary progressive MS. HMB is a popular nutritional supplement among fitness lovers for its efficacy in supporting exercise routine and muscle growth. Additionally, HMB is reported to improve protein balance and reduce muscle wasting in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [6], cancer [5], and aging [7]. As compared with the placebo, HMB supplementation has been also reported to reduce total cholesterol (5.8 %, p<0.03), decrease LDL cholesterol (7.3 %, p<0.01) and lower systolic blood pressure (4.4 mm Hg, p<0.05) [78]. Therefore, it is stimulating to identify the likelihood that low dose of HMB may have remyelinating efficacy in MS (Figure 2). First, HMB stimulates the differentiation of cultured OPCs to OLs. Second, oral HMB increases myelination of demyelinated spinal cord in EAE mice. Third, HMB also reduces clinical symptoms of autoimmune demyelination in EAE mice. Moreover, HMB treatment suppresses autoimmune Th1 and Th17 signaling and augments/restores anti-autoimmune Treg signaling in EAE mice. If cultured OPC results and mouse EAE results are translated, oral HMB may stimulate remyelination via upregulation of OPC maturation, suppression of Th1/Th17 signaling, and restoration of Treg signaling. Since HMB has demonstrated nice safety and tolerability records in different clinical trials, this muscle-building friend may be considered to be repurposed for remyelination in MS (Figure 2). Although there is no evidence of direct crosstalk between muscles and myelin, exercise is known to support muscle strengthening and growth. Recently, it has been described that exercise stimulates the activation of PPARα in the brain [79, 80]. Since PPARα is involved in the maturation of OPCs via direct transcriptional upregulation of myelin-specific genes [57], muscle strengthening via exercise should be helpful for the maturation of OPCs and hence myelination (Figure 2).

Schematic presentation of remyelination by body-building supplement HMB. While HMB and exercise help in body building, it also leads to the maturation of OPC to OL in the CNS, resulting in remyelination.

Funding source: Center for Information Technology

Award Identifier / Grant number: AT10980

Funding source: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Award Identifier / Grant number: 1I01BX005002

Award Identifier / Grant number: 1IK6 BX004982

Award Identifier / Grant number: I01BX005613

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: We did not use large language models and AI and machine learning tools while writing this review.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by a grant (AT10980) from NIH and merit awards (1I01BX005002 and I01BX005613) from US Department of Veterans Affairs. Moreover, Dr. Pahan is the recipient of a Research Career Scientist Award (1IK6 BX004982) from the Department of Veterans Affairs. However, the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

-

Data availability: Data availability is not applicable since it is a review based on published papers.

References

1. Hartline, DK. What is myelin? Neuron Glia Biol 2008;4:153–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1740925x09990263.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Smith, T. The capsules or sheaths of Bacillus actinoides. J Exp Med 1921;34:593–8. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.34.6.593.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Jana, A, Pahan, K. Sphingolipids in multiple sclerosis. NeuroMol Med 2010;12:351–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12017-010-8128-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Sanders, FK, Whitteridge, D. Conduction velocity and myelin thickness in regenerating nerve fibres. J Physiol 1946;105:152–74. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1946.sp004160.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Molfino, A, Gioia, G, Rossi Fanelli, F, Muscaritoli, M. Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation in health and disease: a systematic review of randomized trials. Amino Acids 2013;45:1273–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-013-1592-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Clark, RH, Feleke, G, Din, M, Yasmin, T, Singh, G, Khan, FA, et al.. Nutritional treatment for acquired immunodeficiency virus-associated wasting using beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate, glutamine, and arginine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. JPEN, J Parenter Enter Nutr 2000;24:133–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607100024003133.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Vukovich, MD, Stubbs, NB, Bohlken, RM. Body composition in 70-year-old adults responds to dietary beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate similarly to that of young adults. J Nutr 2001;131:2049–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/131.7.2049.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Pahan, K. Multiple sclerosis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Clin Cell Immunol 2013;4. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9899.1000e113.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Pahan, K. Prospects of cinnamon in multiple sclerosis. J Mult Scler 2015;2:1000149. https://doi.org/10.4172/2376-0389.1000149.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Duquette, P, Pleines, J, Girard, M, Charest, L, Senecal-Quevillon, M, Masse, C. The increased susceptibility of women to multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 1992;19:466–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0317167100041664.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Martin, R, McFarland, HF, McFarlin, DE. Immunological aspects of demyelinating diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 1992;10:153–87. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001101.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Dasgupta, S, Jana, M, Liu, X, Pahan, K. Myelin basic protein-primed T cells of female but not male mice induce nitric-oxide synthase and proinflammatory cytokines in microglia: implications for gender bias in multiple sclerosis. J Biol Chem 2005;280:32609–17. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m500299200.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. McGinley, MP, Goldschmidt, CH, Rae-Grant, AD. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis: a review. JAMA 2021;325:765–79. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.26858.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Brahmachari, S, Pahan, K. Gender-specific expression of beta1 integrin of VLA-4 in myelin basic protein-primed T cells: implications for gender bias in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2010;184:6103–13. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0804356.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Wang, Y, Wang, J, Feng, J. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy: pathogenesis, influencing factors, and treatment options. Autoimmun Rev 2023;22:103449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103449.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Mondal, S, Jana, M, Dasarathi, S, Roy, A, Pahan, K. Aspirin ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through interleukin-11-mediated protection of regulatory T cells. Sci Signal 2018;11. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aar8278.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Mondal, S, Kundu, M, Jana, M, Roy, A, Rangasamy, SB, Modi, KK, et al.. IL-12 p40 monomer is different from other IL-12 family members to selectively inhibit IL-12Rbeta1 internalization and suppress EAE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:21557–67. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2000653117.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Mondal, S, Martinson, JA, Ghosh, S, Watson, R, Pahan, K. Protection of Tregs, suppression of Th1 and Th17 cells, and amelioration of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by a physically-modified saline. PLoS One 2012;7:e51869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051869.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Mondal, S, Pahan, K. Cinnamon ameliorates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in mice via regulatory T cells: implications for multiple sclerosis therapy. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116566.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Brahmachari, S, Pahan, K. Role of cytokine p40 family in multiple sclerosis. Minerva Med 2008;99:105–18.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Haki, M, Al-Biati, HA, Al-Tameemi, ZS, Ali, IS, Al-Hussaniy, HA. Review of multiple sclerosis: epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medicine 2024;103:e37297. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000037297.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Pahan, K. Neuroimmune pharmacological control of EAE. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2010;5:165–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-010-9219-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Jakimovski, D, Bittner, S, Zivadinov, R, Morrow, SA, Benedict, RH, Zipp, F, et al.. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2024;403:183–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01473-3.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Coutinho Costa, VG, Araujo, SE, Alves-Leon, SV, Gomes, FCA. Central nervous system demyelinating diseases: glial cells at the hub of pathology. Front Immunol 2023;14:1135540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1135540.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Cree, BAC, Arnold, DL, Chataway, J, Chitnis, T, Fox, RJ, Pozo Ramajo, A, et al.. Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: new insights. Neurology 2021;97:378–88. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000012323.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Kuhlmann, T, Moccia, M, Coetzee, T, Cohen, JA, Correale, J, Graves, J, et al.. Multiple sclerosis progression: time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol 2023;22:78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00289-7.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Jana, A, Pahan, K. Oxidative stress kills human primary oligodendrocytes via neutral sphingomyelinase: implications for multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2007;2:184–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-007-9066-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Mondal, S, Rangasamy, SB, Ghosh, S, Watson, RL, Pahan, K. Nebulization of RNS60, a physically-modified saline, attenuates the adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in mice: implications for multiple sclerosis therapy. Neurochem Res 2017;42:1555–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-017-2214-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Rangachari, M, Kuchroo, VK. Using EAE to better understand principles of immune function and autoimmune pathology. J Autoimmun 2013;45:31–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2013.06.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Simons, M, Nave, KA. Oligodendrocytes: myelination and axonal support. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2015;8:a020479. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020479.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Bradl, M, Lassmann, H. Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol 2010;119:37–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-009-0601-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Bergles, DE, Richardson, WD. Oligodendrocyte development and plasticity. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2015;8:a020453. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020453.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Sakry, D, Trotter, J. The role of the NG2 proteoglycan in OPC and CNS network function. Brain Res 2016;1638:161–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Figarella-Branger, D, Colin, C, Baeza-Kallee, N, Tchoghandjian, A. A2B5 expression in central nervous system and gliomas. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23094670.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Hoftberger, R, Lassmann, H. Inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system. Handb Clin Neurol 2017;145:263–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-802395-2.00019-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Friese, MA, Schattling, B, Fugger, L. Mechanisms of neurodegeneration and axonal dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:225–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.37.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Dobson, R, Giovannoni, G. Multiple sclerosis – a review. Eur J Neurol 2019;26:27–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13819.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Lubetzki, C, Stankoff, B. Demyelination in multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;122:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-52001-2.00004-2.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Dasgupta, S, Jana, M, Zhou, Y, Fung, YK, Ghosh, S, Pahan, K. Antineuroinflammatory effect of NF-kappaB essential modifier-binding domain peptides in the adoptive transfer model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2004;173:1344–54. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1344.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Dasgupta, S, Roy, A, Jana, M, Hartley, DM, Pahan, K. Gemfibrozil ameliorates relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Mol Pharmacol 2007;72:934–46. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.106.033787.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Hooper, DC, Spitsin, S, Kean, RB, Champion, JM, Dickson, GM, Chaudhry, I, et al.. Uric acid, a natural scavenger of peroxynitrite, in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:675–80. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.2.675.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Mondal, S, Roy, A, Pahan, K. Functional blocking monoclonal antibodies against IL-12p40 homodimer inhibit adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2009;182:5013–23. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0801734.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Saha, RN, Pahan, K. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in glial cells. Antioxid Redox Signaling 2006;8:929–47. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2006.8.929.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Saha, RN, Pahan, K. Signals for the induction of nitric oxide synthase in astrocytes. Neurochem Int 2006;49:154–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2006.04.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Elbaz, B, Popko, B. Molecular control of oligodendrocyte development. Trends Neurosci 2019;42:263–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2019.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Kuhn, S, Gritti, L, Crooks, D, Dombrowski, Y. Oligodendrocytes in development, myelin generation and beyond. Cells 2019;8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8111424.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Tepavcevic, V, Lubetzki, C. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell recruitment and remyelination in multiple sclerosis: the more, the merrier? Brain 2022;145:4178–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac307.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Duncan, ID, Radcliff, AB, Heidari, M, Kidd, G, August, BK, Wierenga, LA. The adult oligodendrocyte can participate in remyelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E11807–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808064115.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Kaczka, P, Michalczyk, MM, Jastrzab, R, Gawelczyk, M, Kubicka, K. Mechanism of action and the effect of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation on different types of physical performance – a systematic review. J Hum Kinet 2019;68:211–22. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0070.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Kim, D, Kim, J. Effects of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation on recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage: a mini-review. Phys Act Nutr 2022;26:41–5.10.20463/pan.2022.0023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Prado, CM, Orsso, CE, Pereira, SL, Atherton, PJ, Deutz, NEP. Effects of beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation on muscle mass, function, and other outcomes in patients with cancer: a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022;13:1623–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12952.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Lin, Z, Zhao, A, He, J. Effect of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) on the muscle strength in the elderly population: a meta-analysis. Front Nutr 2022;9:914866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.914866.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Holecek, M. Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation and skeletal muscle in healthy and muscle-wasting conditions. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017;8:529–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12208.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Durkalec-Michalski, K, Jeszka, J, Podgorski, T. The effect of a 12-week beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation on highly-trained combat sports athletes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Nutrients 2017;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070753.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Jana, M, Pahan, K. Redox regulation of cytokine-mediated inhibition of myelin gene expression in human primary oligodendrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 2005;39:823–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Jana, M, Pahan, K. Down-regulation of myelin gene expression in human oligodendrocytes by nitric oxide: implications for demyelination in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Cell Immunol 2013;4. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9899.1000157.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Jana, M, Prieto, S, Gorai, S, Dasarathy, S, Kundu, M, Pahan, K. Muscle-building supplement beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate stimulates the maturation of oligodendroglial progenitor cells to oligodendrocytes. J Neurochem 2024;168:1340–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.16084.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Georgiadi, A, Kersten, S. Mechanisms of gene regulation by fatty acids. Adv Nutr 2012;3:127–34. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.111.001602.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Alex, S, Lange, K, Amolo, T, Grinstead, JS, Haakonsson, AK, Szalowska, E, et al.. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate angiopoietin-like 4 synthesis in human colon adenocarcinoma cells by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Mol Cell Biol 2013;33:1303–16. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00858-12.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Pahan, K. Lipid-lowering drugs. Cell Mol Life Sci 2006;63:1165–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-005-5406-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Roy, A, Pahan, K. PPARalpha signaling in the hippocampus: crosstalk between fat and memory. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2015;10:30–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-014-9582-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Paidi, RK, Raha, S, Roy, A, Pahan, K. Muscle-building supplement beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate binds to PPARalpha to improve hippocampal functions in mice. Cell Rep 2023;42:112717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112717.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Saha, RN, Ghosh, A, Palencia, CA, Fung, YK, Dudek, SM, Pahan, K. TNF-alpha preconditioning protects neurons via neuron-specific up-regulation of CREB-binding protein. J Immunol 2009;183:2068–78. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0801892.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Saha, RN, Pahan, K. HATs and HDACs in neurodegeneration: a tale of disconcerted acetylation homeostasis. Cell Death Differ 2006;13:539–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401769.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Tyteca, S, Legube, G, Trouche, D. To die or not to die: a HAT trick. Mol Cell 2006;24:807–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Robinson, AP, Harp, CT, Noronha, A, Miller, SD. The experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS: utility for understanding disease pathophysiology and treatment. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;122:173–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52001-2.00008-X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67. Baxter, AG. The origin and application of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Rev Immunol 2007;7:904–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2190.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Brahmachari, S, Pahan, K. Sodium benzoate, a food additive and a metabolite of cinnamon, modifies T cells at multiple steps and inhibits adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2007;179:275–83. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.275.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Dasgupta, S, Zhou, Y, Jana, M, Banik, NL, Pahan, K. Sodium phenylacetate inhibits adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL/J mice at multiple steps. J Immunol 2003;170:3874–82. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3874.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Mondal, S, Sheinin, M, Rangasamy, SB, Pahan, K. Amelioration of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by gemfibrozil in mice via PPARbeta/delta: implications for multiple sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci 2024;18:1375531. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2024.1375531.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Sheinin, M, Mondal, S, Roy, A, Gorai, S, Rangasamy, SB, Poddar, J, et al.. Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice by beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate, a body-building supplement in humans. J Immunol 2023;211:187–98. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2200267.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72. Brahmachari, S, Pahan, K. Suppression of regulatory T cells by IL-12p40 homodimer via nitric oxide. J Immunol 2009;183:2045–58. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0800276.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Brahmachari, S, Pahan, K. Myelin basic protein priming reduces the expression of Foxp3 in T cells via nitric oxide. J Immunol 2010;184:1799–809. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0804394.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

74. Kleinewietfeld, M, Hafler, DA. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune neuroinflammation. Immunol Rev 2014;259:231–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12169.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Rostami, A, Ciric, B. Role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of CNS inflammatory demyelination. J Neurol Sci 2013;333:76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76. Danikowski, KM, Jayaraman, S, Prabhakar, BS. Regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis. J Neuroinflammation 2017;14:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-017-0892-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77. Pahan, S, Pahan, K. Mode of action of aspirin in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. DNA Cell Biol 2019;38:593–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/dna.2019.4814.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78. Nissen, S, Sharp, RL, Panton, L, Vukovich, M, Trappe, S, Fuller, JCJr. beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation in humans is safe and may decrease cardiovascular risk factors. J Nutr 2000;130:1937–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/130.8.1937.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Dutta, D, Paidi, RK, Raha, S, Roy, A, Chandra, S, Pahan, K. Treadmill exercise reduces alpha-synuclein spreading via PPARalpha. Cell Rep 2022;40:111058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111058.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80. Rangasamy, SB, Jana, M, Dasarathi, S, Kundu, M, Pahan, K. Treadmill workout activates PPARalpha in the hippocampus to upregulate ADAM10, decrease plaques and improve cognitive functions in 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 2023;109:204–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.01.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Brief Report

- Elevated cerebral oxygen extraction in patients with post-COVID conditions

- Review Articles

- Build muscles and protect myelin

- Cannabis use, oral dysbiosis, and neurological disorders

- Sedation with midazolam in the NICU: implications on neurodevelopment

- The challenges to detect, quantify, and characterize viral reservoirs in the current antiretroviral era

- Research Articles

- Biodegradable cannabidiol: a potential nanotherapeutic for neuropathic pain

- Motivational dysregulation with melanocortin 4 receptor haploinsufficiency

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Brief Report

- Elevated cerebral oxygen extraction in patients with post-COVID conditions

- Review Articles

- Build muscles and protect myelin

- Cannabis use, oral dysbiosis, and neurological disorders

- Sedation with midazolam in the NICU: implications on neurodevelopment

- The challenges to detect, quantify, and characterize viral reservoirs in the current antiretroviral era

- Research Articles

- Biodegradable cannabidiol: a potential nanotherapeutic for neuropathic pain

- Motivational dysregulation with melanocortin 4 receptor haploinsufficiency