Abstract

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a promising pharmaceutical agent to treat pain, inflammation, and seizures without the psychoactive effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). While CBD is highly lipophilic and can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), its bioavailability is limited and clearance is quick, limiting its effectiveness in the brain. To improve its effectiveness, we developed a unique nanoformulation consisting of CBD encapsulated within the biodegradable and biocompatible polymer, methoxy polyethylene glycol-poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (mPEG-PLGA). mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles exhibited negligible cytotoxicity over a range of concentrations in CCK-8 assays performed in human astrocytes and brain microvascular endothelial cells. Furthermore, in an in-vitro BBB model, they exhibited rapid BBB permeability without harming BBB integrity. An in vivo Chronic Constriction Injury animal pain model was employed to study the efficacy of mPEG-PLGA-CBD in doses 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg, and it was found that 45–55 nm CBD nanoparticles with an encapsulation efficiency of 65 % can cross the BBB. Additionally, 3 and 10 mg/kg mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation provided prolonged analgesia in rats on day 2 and -4 post-injection, which we propose is attributed to the sustained and controlled release of CBD. Future studies are required to understand the pharmacokinetics of this nanoformulation.

Introduction

Cannabidiol (CBD), one of over 100 naturally occurring cannabinoids from cannabis sativa, has been identified as a promising pharmaceutical agent due to its non-psychoactive effects [1]. It has shown anti-inflammatory, cell proliferation, apoptosis, analgesic, and anti-epileptic properties [2–7]. Till date, the FDA has approved one cannabis-derived CBD drug, Epidiolex, used in treating childhood seizures [8]. However, CBD’s clinical and scientific understanding is limited, and its use in medicinal treatments faces challenges such as multiple pharmacokinetics profiles, limited bioavailability, and potential polymorphisms. These issues could lead to unpredictable efficacies, drug-drug interactions at higher doses, or even greater side effects [9]. Out of these issues, the bioavailability of CBD is quite challenging due to its lipophilic nature, which makes it difficult to be absorbed into the bloodstream. Studies by Huestis et al. show that oral administration of oil-based CBD extract has a bioavailability of 4–20 % [10, 11].

Despite these issues, cannabinoids can be highly beneficial in neuropathic pain management. Neuropathic pain, defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system” [12, 13], is classified as a type of chronic pain lasting more than three months [14], and has a prevalence rate of 8–10 % in U.S. adults [15]. Conventional analgesics (such as opioids), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have limited efficacy in treating neuropathic pain and can be dangerous to the patient, causing serious side effects [16–19]. Therefore, development of new effective drug therapy for chronic pain management is necessary.

One such drug therapy for neuropathic pain could be CBD nanoformulation, using specifically a polymeric-based nanocarrier called block-co-polymer mPEG-PLGA, which gives rise to a particle with a PLGA core, and a mPEG decorated surface [20]. CBD can be highly beneficial in treating neuropathic pain symptoms. Studies have shown treatment with CBD significantly increased mechanical and thermal threshold in chronic neuropathic pain-induced rats when compared to rats receiving vehicles [21–25]. Some of the mechanisms by which CBD exerts its analgesic effects are discussed below.

CB1 and CB2 are G-protein coupled receptors, CB1 is found in the CNS (basal ganglia, frontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum) while CB2 is present in the immune cells and considered a peripheral receptor. CBD acts as a negative allosteric modulator in the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors [26]. Its mechanism of action is that it causes inhibition of anandamide hydrolysis [27] and increases anandamide levels for CB1 and TRPV1 binding. These effects were proven by a study carried out by Nascimento and authors, who showed that the selective FAAH inhibitor (URB597) improved the CBD effect, while the CBD effect was inhibited by blocking of CB1 receptors by AM251; capsazepine, which is a TRPV1 antagonist also increased the anti-nociceptive effects [28].

CBD exerts its mechanism of action not only by its action on the endocannabinoid receptors but also on various other receptors like serotoninergic 5-HT1A receptors [29], TRPV1 receptor, and PPARy receptor [30]. CBD acts as an inverse agonist at G-protein receptors (3, 6 and 12), which are involved in the development of neuropathic pain [31, 32]. CBD activates various forms of the transient receptor potential (TRP) like TRPA1, TRPV1, and TRPV2/4 (as explained above) [33] and acts as a negative allosteric modulator at the serotonin receptor (5HT).

In a recent study, Wang et al. [34] studied the role of FKBP5 in neuropathic pain. FKBP5 is an immunophilin protein that promotes inflammation by facilitating the assembly of IKK (IkB kinase) and activates NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells). NF-kB is an important transcription factor that further activates pro-inflammatory factors like IL-1β, NO, TNF-α, and IL-6. They found that CBD binds to the FKBP5 protein and antagonizes its effect, thus playing a significant role in reducing neuropathic pain [34].

There are various types of nanoparticles such as lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, silica nanoparticles, etc. Out of these, polymeric nanoparticles (PNP) have been widely employed because of the polymeric core. Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) is a commonly used polymer in drug delivery applications, as it is biodegradable and biocompatible, has minimum systemic toxicity, and offers a considerable amount of tunability for disease-specific optimization. FDA has approved PLGA to be used in medical applications [35]. After the nanoparticle is in systemic circulation it is subjected to opsonization by the opsonin proteins and leads to phagocytosis. Pegylation, i.e., coating nanoparticles with a hydrophilic copolymer polyethyleneglycol (PEG), has proven to be beneficial in protecting the nanoparticles against the phagocytic cells and protein absorption to the surface, they promote mucoadhesion of nanoparticles, enhance nanoparticles stability in the digestive fluids, and increases their circulation time [36, 37].

The PLGA nanoparticles are normally in the size range of 10–400 nm [38]. Nanes et al., suggested that dense PEG coating can improve the penetration of polymeric nanoparticles across the BBB. PEGylation also reduces the reticuloendothelial system uptake and clearance of nanoparticles, thus increasing the circulation time, and allowing for more efficient penetration across the BBB [39]. From the literature review, mPEG-PLGA is extremely safe to use in nanoformulation. According to some studies, local tissue reactions may occur at the site of application but these reactions are very mild [40, 41]. mPEG-PLGA is a biodegradable material that degrades in vivo either enzymatically or non-enzymatically and produces biocompatible, toxicologically safe by-products. The improved bioavailability, enhanced circulation time, minimum toxicity, and small diameter of the prepared nanoparticles makes PEG-PLGA polymer ideal for our nanoformulation.

Therefore, for this study, we have developed a CBD nanoparticle for intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration in rats with chronic neuropathic pain. We hypothesized that encapsulating CBD within a polymeric nanoparticle (mPEG-PLGA) would improve its pharmacokinetic profile such as its stability and bioavailability across the BBB, thus enhancing its efficacy in treating neuropathic pain and that the sustained release of drug from the nanoparticle would allow for a prolonged therapeutic effect (Figure 1).

Schematic representation of CBD nanoparticle (drawn by the author).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Primary cultures of both human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (BMVEC) (Cat# ACBRI-376) and Normal Human Astrocytes (NHA) (Cat# ACBRI-371) were obtained from Applied Cell Biology Research Institute (ACBRI) Kirkland, WA. BMVEC were cultured in CS-C complete serum-free medium (ABCRI, Cat SF-4Z0-500) with attachment factors (ABCRI, Cat # 4Z0-210), 5 % Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1 % antibiotic–antimycotic, endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS) (15MG; BD Biosciences) and Passage Reagent GroupTM (ABCRI, Cat # 4Z0-800). NHAs were cultured in CS-C complete serum-free medium (ABCRI, Cat SF-4Z0-500), supplemented with 10 mg/mL human EGF, 10 mg/mL insulin, 25 mg/mL progesterone, 50 mg/mL transferrin, 50 mg/mL gentamicin, 50 mg/mL amphotericin, and 10 % FBS, and characterized by >99 % of these cells being positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Both BMVEC and NHA were obtained at passage 2 for each experiment and were used for all experimental paradigms between 2 and 8 passages: within the 6 to 27 cumulative population doublings.

Materials

CBD was obtained from PRISM HEMP (>99 % CBD-pure isolate 25 g, 99.93 % Lot 4A) and contained less than 0.3 % tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether-block-poly(lactide-co-glycolide) with a PEG average of Mn 2,000 and PLGA average of Mn 11,500. Lactide: glycolide 50:50 obtained from SIGMA-ALDRICH, Co.

Nanoparticles synthesis

mPEG-PLGA CBD nanoparticles were fabricated by using the oil-water emulsion evaporation technique [35]. The aqueous phase consisted of 5 % F127 (500 µL/1.5 µL, distilled H2O). The organic phase consisted of mPEG-PLGA (5 mg) CBD (7.2 mg) in 500 μL ethyl acetate combined with 50 µL of Cy5 dye (3,3-diethylthiadicarbocyanine iodide) (0.5 mg/mL, methylene chloride). The aqueous phase was heated briefly and then combined with the organic phase using probe sonication for 3 min at 30 % amplification. The organic solvent was evaporated under airflow with continuous stirring for 30 min. The CBD nanoparticles were purified by centrifugation using 30 K MWCO Spin-X tubes for 20 min at 4,000 rpm. The retentate (nanoparticles) was resuspended in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) or culture media (NHA/BMVEC) to a total volume of 2 mL. All the sample preparations were analyzed in triplicate (n=3), using three independent batches, and tested at room temperature.

Nanoparticle characterization

The nanoparticles were characterized by their size and surface charge using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential analysis using HORIBA SZ-100 and 90Plus zeta sizer [35, 42]. The encapsulation efficiency of CBD in our nanoparticles was determined using HPLC-UV (Waters 2795). The size and morphology of the mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [42]. The in-vitro drug release and the stability assays were also performed [43]. For detailed nanoparticle characterization see Appendix A in Supplementary Material.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using CCK-8 (Cell Counting Kit-8) assay (Dojindo laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 100 µL (5,000 cells/well) of cell suspension was added to each well in a 96-well microplate. After a 24 h incubation, the test drug mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation was added in concentrations ranging from 0.0000035 μg to 3,500 μg. The next day, the media was replaced with fresh 100 µL media, and 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. The plate was then read at 480 nm using an absorbance plate reader. The cell viability was normalized against untreated control cells and percentage cell viability was calculated using the Equation (1):

where, Absorbance negative control=untreated control (Cells+media+CCK-8)

Absorbance sample=Cells+Test drug+Media+CCK-8

Absorbance blank=Media (no cells)+CCK-8

LC50 determination

Cell viability readings were used to determine the LC50 value of CBD and the nanoformulation at different concentrations for both NHA and BMVEC cell lines. n=3 replicates were performed for each sample on each cell line for each experiment, and each experiment was repeated three times. The values and errors reported were calculated from these measurements after curves were fitted with a 4-variable sigmoidal curve to calculate the LC50 values. For the curve fitting, we used a simple linear regression curve (Graph Pad Inc, Prism version 8.0). Statistical analysis was used to provide the error analysis for the calculated LC50 values derived from the fitted curves.

Cellular uptake

BMVEC and NHA were treated with mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles containing Cy5 dye and incubated at 37 °C for 1, 2, and 24 h post-treatment. Cells were then fixed using 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, followed by washing using PBS three times. Nuclear staining was achieved by incubation with DAPI for 5 min (0.1/mL). Cells were then washed 3 times with 1× PBS and cell imaging was performed using the Discover – ECHO Revolve generation 2 microscope. Fluorescent intensity was quantitated by ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

In vitro BBB model

The in vitro transwell model of the BBB [44, 45] was used in this study that uses BMVEC and NHA cell types, which are known to constitute the human BBB (see Appendix B in Supplementary Material). All the experiments were repeated 3 times, n=3.

Transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements

TEER measurements are done using the Millicell-ERS microelectrodes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Millicell-ERS Electrodes were sterilized using 95 % alcohol and rinsed in distilled water prior to measurement. A constant distance of 0.6 cm was always maintained between the electrodes during TEER measurement. An increase in TEER is indicative of tightness of the BBB, while a decrease in TEER is indicative of a leaky BBB.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran fluorescein was used to confirm the paracellular permeability associated with the TEER measurement. FITC-dextran (40,000 MW, 1 mg/mL; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to the upper compartments of the transwell cultures. The media was harvested at 1 h post addition of FITC Dextran, and the amount of fluorescence was quantitated using a fluorescence microplate reader at 492 nm (excitation) and 520 nm (emission) wavelengths. The fluorescence intensity was expressed as RFU (Relative Mean Fluorescence Units), and the permeability was calculated using Equation (2).

where, VA is the volume of the basolateral compartment.

CA is the concentration in the lower chamber.

S is the surface area of the insert (0.3 cm2), T=time, and CL=FITC concentration (100 %).

BBB permeability assay

Permeability of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles across the BBB is performed by entrapping tracking dye Cy5 into the nanoparticles. Free CBD and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation are added to the upper chamber of the BBB model to evaluate the ability of free CBD and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles to cross the BBB. The BBB model was incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Fractions (100 µL) of media were collected from the upper chamber, and 200 µL fractions were collected from the lower chamber at predetermined time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h) post treatment. The volume of the media harvested was replenished by the addition of an equal volume (200 µL) of fresh media in the upper chamber. Acetonitrile was added to these fractions in a 1:1 ratio and the samples were centrifuged at 14 g for 30 min. The samples were subsequently analyzed using emission spectroscopy using a spectrofluorometer (Biotek).

In vivo CCI model

Male Sprague-Dawley rats, 200–300 g body weight were used for the sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury (CCI) model of neuropathic pain. mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles were tested in three concentrations 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg. For measuring nociception thermal analgesia and mechanical allodynia tests were performed. The experimental model and tests are explained in detail in Appendix C in Supplementary Material.

Brain tissue isolation & storage

Brains were processed and stored according to established published protocols [46]. Briefly, the brain was hemi-dissected, and the right and left hemispheres were stored separately prior to RNA isolation. Brain tissue regions (hippocampus, thalamus, ventral tegmental area (VTA), periaqueductal gray (PAG)) were frozen immediately in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction.

RNA extraction

Tissue RNA was extracted by an acid guanidinium-thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method, using TRIzol® reagent. TRIzol® reagent (500 μL) was added to the brain samples weighing 10–30 mg and homogenized in beadBug microtube homogenizer (benchmark Scientific model D1030) for 60 s at 3,500 rpm. The samples were transferred to a 1.5 mL tube and 100 μL of chloroform was added. After 10 min at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The colorless layer was carefully transferred to a new 1.5 mL tube and 300 μL of isopropanol was added, the tubes were stored at −80 °C overnight. The next day the tubes were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The RNA was precipitated as a pellet and was washed twice with 1 mL of 75 % ethanol followed by air drying for 5 min and re-constitution with 25 μL of DEPC H20. The amount of RNA was quantified using a Nano-Drop ND-1000 spectrophotometer and the isolated RNA was stored at −80 °C.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, 500 ng of the total RNA that was extracted as described above was utilized for the All-in-One Universal RT Master Mix synthesis kit (Lamba Biotech). One microliter of the resultant cDNA from the RT reaction was employed as the template in PCR reactions using well-validated PCR primers obtained from IDT-Integrated DNA Technologies. The primer sequences can be found in Table 1. We used the SYBR® Green master mix that contained dNTPs, MgCl2, and DNA polymerase (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The final primer concentration used in the PCR was 0.1 µM. The following were the PCR conditions: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 40 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; the final extension was at 72 °C for 5 min. Gene expression was calculated using the comparative CT method. To account for variations in RNA input quantity, measurements were performed on an endogenous reference gene, β-actin. The threshold cycle (Ct) of each sample was determined, the relative level of a transcript (2ΔCt) was calculated by obtaining ΔCt (test Ct−β-actin Ct), and transcript accumulation index (TAI) was calculated as TAI=2−ΔΔCT [47].

Primers with their gene accession number and sequences.

| Primer | Full name | Gene accession# | Forward sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reverse sequence (3′ to 5′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gpr158 | G protein-coupled receptor 158 | NM_001170326.1 | CAT GAG GAT GCT GGC AGT AAT A | CAA GAT ATC CCG CTC CAA GTT |

| HDAC5 | Histone deacetylase 5 | NM_053450.1 | AGT ACC ACA CCC TGC TCT AT | AGC ATG GCG TAC ATC TTC TG |

CBD quantification in various anatomical brain regions

Brain tissue samples were homogenized in beadBug microtube homogenizer (benchmark Scientific model D1030) for 60 s at 3,500 rpm. The samples were prepared according to the method described in paper [48]. The amount of CBD in the prepared samples were quantified using HPLC system (Waters 2795), with the same method as described above (in encapsulation efficiency). The CBD calibration curve was plotted and used to quantify CBD concentration.

Statistical analysis

Data is expressed as mean±SEM. Statistical comparisons were made between treated, untreated cultures and animal groups using a two-tailed t-test, one-way and two-way ANOVA, with multiple comparisons using post-hoc Dunnett’s test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) software.

Results

Nanoparticle characterization

The particles were spherical in shape when characterized by TEM analysis (Figure 2A). The diameter and surface charge of the nanoparticles is mentioned in Table 2. Incorporating Cy5 within the nanoparticles together with CBD did not negatively alter the diameter of the nanoparticles. The diameter of our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles was <100 nm (Figure 2B), which is ideal for passage across the BBB [49].

Nanoparticle characterization and in vitro drug release. (A) TEM images of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle. (B) Size distribution for mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles (CBD NP), CBD-Cy5 nanoparticles, and nanoparticles alone (mPEG-PLGA NP). (C) In vitro drug release of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles at pH 5.5 (black/circle) and 7.4 (pink/square), there was 53 % drug release at pH 5.5 and 48 % at pH 7.4 at 6 h, (D) 99 % drug release at pH 5.5 and 96 % drug release at pH 7.4 over 72 h. Note: The ordinate and abscissa values are different for the two graphs.

Nanoparticle characterization; size, surface charge, encapsulation, loading efficiency (EE and LE), and polydispersity index (PDI).

| Diameter, nm | SD (±) | Zeta potential, mV | SD (±) | EE, % | SD (±) | LE, % | SD (±) | PDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mPEG-PLGA NP | 55.1 | 4.4 | −23.6 | 4.7 | – | – | 0.219 | ||

| mPEG-PLGA-CBD NP | 45.4 | 7.0 | −2.5 | 2.8 | 62.9 % | 2 | 90.5 % | 3.3 | 0.18 |

| CBD-Cy5 NP | 52.7 | 8.4 | −2.25 | 2.19 | 62.9 % | 2 | 90.5 % | 3.3 | 0.182 |

The encapsulation efficiency for our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles is 63 %, where 4.52 mg of CBD from the total 7.2 mg of CBD was encapsulated within the nanoparticles with a loading efficiency of 90 %.

In vitro drug release

mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles demonstrated different drug release profiles at different pH which is due to the pH sensitivity of PLGA degradation. Since the particles are expected to be taken up into the cells by endocytosis, studying the drug release at different pH is important. Endosomes and lysosomes have a pH range of 6.5 (early endosomes) and 5.5 (late-stage endosomes and lysosomes) (Figure 2C), so the pH sensitive release suggests a more rapid drug release once the particles are taken up into the cell. The difference in the release rate at both pH is subtle and may not provide a significant benefit. The CBD release rate at systemic pH 7.4 (Figure 2D) does indicate some drug leakage during systemic circulation. In vivo bio-distribution of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles is necessary to understand the circulation time of the nanoparticle; also, different routes of administration can be explored to minimize the systemic circulation time.

Nanoparticle stability study

Our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles were stable for a period of 14 days when suspended in PBS (1×) and FBS (5 %) at 5 and 37 °C (see Supplementary Figure 2). A slight decrease in hydrodynamic diameter was observed when particles were stored in FBS, which is a general property of PLGA nanoparticles, they initially tend to shrink at about 5 days and then return to near original size, before expanding as they degrade. The nanoparticles were incubated in serum to model the proteins present during circulation, the major proteins present in serum are α-, β-, and γ-globulins and albumin. We examined the stability of our nanoformulation in serum since the nanoformulation is administered systemically in vivo. Our nanoparticles showed a consistent size over time at 37 °C with serum indicating that particles themselves do not aggregate nor do they form a protein corona. This suggests potential for prolonged circulation of particles in vivo.

In vitro cytotoxicity

For both NHA and BMVEC cells, mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle in the concentration 0.35 and 3.5 μg/mL was statistically non-significant to control, indicating at these concentrations cell viability was 100 % as that of the control (Figure 3A and B).

(A) NHA viability, (B) BMVEC viability. The graph is plotted as CBD nanoparticle (mPEG-PLGA-CBD) concentrations vs. % cell viability. The cell viability at concentrations 0.35 μg/mL and 3.5 μg/mL are similar to the control. In both NHA cell (A) (F=25.04) and BMVEC cells (B) (F=32.71), the cell viability at the highest CBD-NP concentration 350 μg/mL and 3,500 μg/mL where significantly toxic as compared to the control and therefore the cutoff value of CBD-NP concentration used was 35 μg/mL where cell viability was at 65 % as compared to control. Statistical analysis is performed using one-way ANOVA and error bars are plotted as ±SEM. (C) Confocal images representing cellular uptake of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles by (C; A) NHA and (C; B) BMVEC cells at various time points (t=h) 0, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4, where blue is the DAPI signal (nucleus), and red is the intracellular Cy5 signal (trapped within the nanoparticles along with CBD). Magnification at 33.3 %, scale bar 242 pixels.

LC50 calculation

The LC50 values calculated using the Prism software. (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) are summarized in Table 3. The data suggests that there is negligible toxicity at 3.5 μg/mL, thus this was the dose used for BBB permeability/integrity experiments as well as the gene expression analysis studies. mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation showed significant toxicity over 350 μg/mL concentration.

LC50 values.

| LC50 | Simple linear regression equation | R2 | LC50, μg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHA | Y=0.6698*X+0.1887 | 0.8972 | 74.36 μg/mL |

| BMVEC | Y=0.3946*X+6.051 | 0.7349 | 111.37 μg/mL |

Cellular uptake

The cellular uptake signal coming from Cy5 dye was observed at 30 min post-incubation, with maximum cellular uptake signal at 4 h. These results confirm the cellular uptake of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles into the NHA and BMVEC cells (Figure 3C). For % cell viability of mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles see Supplementary Figure 5.

BBB integrity and permeability

The in vitro BBB model (Figure 4A, [42]) was used to validate the effect of CBD and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles on BBB integrity and permeability. Our results showed that treatment with free CBD resulted in a small but significant decrease in TEER across the BBB (13 %, p=0.0015) indicating that free CBD treatment negatively impacted the BBB integrity and thus increased BBB permeability, whereas treatment with empty mPEG-PLGA nanoparticle and the mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation caused a significant increase in TEER by 23 % (p=0.0332) and 7 % (ns), respectively, indicating a slight increase in BBB tightness, suggesting that the nanoformulation preserves the integrity of the BBB while still allowing for CBD to transverse to the basolateral compartment and may thus facilitate a more controlled release of CBD across the BBB (Figure 4B). There was a significant increase in Dextran FITC permeability across the BBB treated with CBD alone (p=0.0110, unpaired t-test) indicating CBD treatment would permeate due to the leaky membrane.

Effect of CBD on BBB integrity and permeability. (A) In vitro BBB model showing the crossing of nanoparticles across the membrane. (B) Integrity of BBB with free CBD (3.5 μg), empty nanoparticle, and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle (3.5 μg) was measured using TEER. According to one-way ANOVA, there was a significant difference between control and treatment groups (F (3,8)=14.22, p=0.0014), and unpaired t-test determined the % change in TEER for CBD was significantly lower (14 %) as compared to untreated control (t=7.729 df=4, p=0.0015) and for mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles was significantly higher (23 %) as compared to untreated control (t=3.181, df=4, p=0.0335). (C) The apparent permeability of CBD across BBB. According to one-way ANOVA, the data is statistically significant (F=10.96, p=0.0033). Unpaired t-test demonstrates there is a significant increase in FITC permeability across the BBB treated with CBD (3.5 μg) (t=4.478, df=4, p=0.0110) whereas BBB treated with empty nanoparticle and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle (3.5 μg) were non-significant as compared to control. (D) The permeability of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles across BBB by measuring fluorescence intensity of encapsulated Cy5 dye at time points: 0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 3 h, and 24 h (x-axis). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (F (5,6), p<0.0001). The error bars are plotted as ±SEM. UT control (untreated control).

BBB co-cultures treated with mPEG-PLGA nanoparticle alone and the mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation showed no significant change in the FITC permeability as compared to untreated control, indicating mPEG-PLGA nanoformulation and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation did not have any significant effect on the BBB integrity i.e., the BBB remained intact (Figure 4C).

Ability of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation to transverse the BBB

The mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation was added to the apical chamber of the BBB, and after 3 h post addition 41 % nanoformulation was able to transverse across the BBB into the basolateral chamber and 65 % after 24 h, respectively (Figure 4D). Our data demonstrates that the CBD mPEG-PLGA nanoformulation rapidly traversed the BBB, suggesting it is suitable for CBD delivery to the brain, although HPLC-UV analysis would be necessary to quantify the amount of CBD that accumulates.

mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle injection alleviates thermal hyperalgesia

CCI-operated rats developed thermal hyperalgesia in the ipsilateral (right) hind paw as compared to sham-operated rats (see Supplementary Figure 3). The rats received treatment in doses of 1/3/10 mg/kg free CBD and CBD nanoformulation. The dose was calculated based on the amount of CBD entrapped within the nanoparticle: 4.2 mg CBD was encapsulated in a 2 mL nanoformulation suspension. The volume injected into animals was calculated based on the animal’s weight, the equivalent dose (1/3/10), and the amount of encapsulated CBD in nanoparticles. The same amount of free CBD was dissolved in the vehicle and the volume injected was calculated same as for CBD nanoformulation.

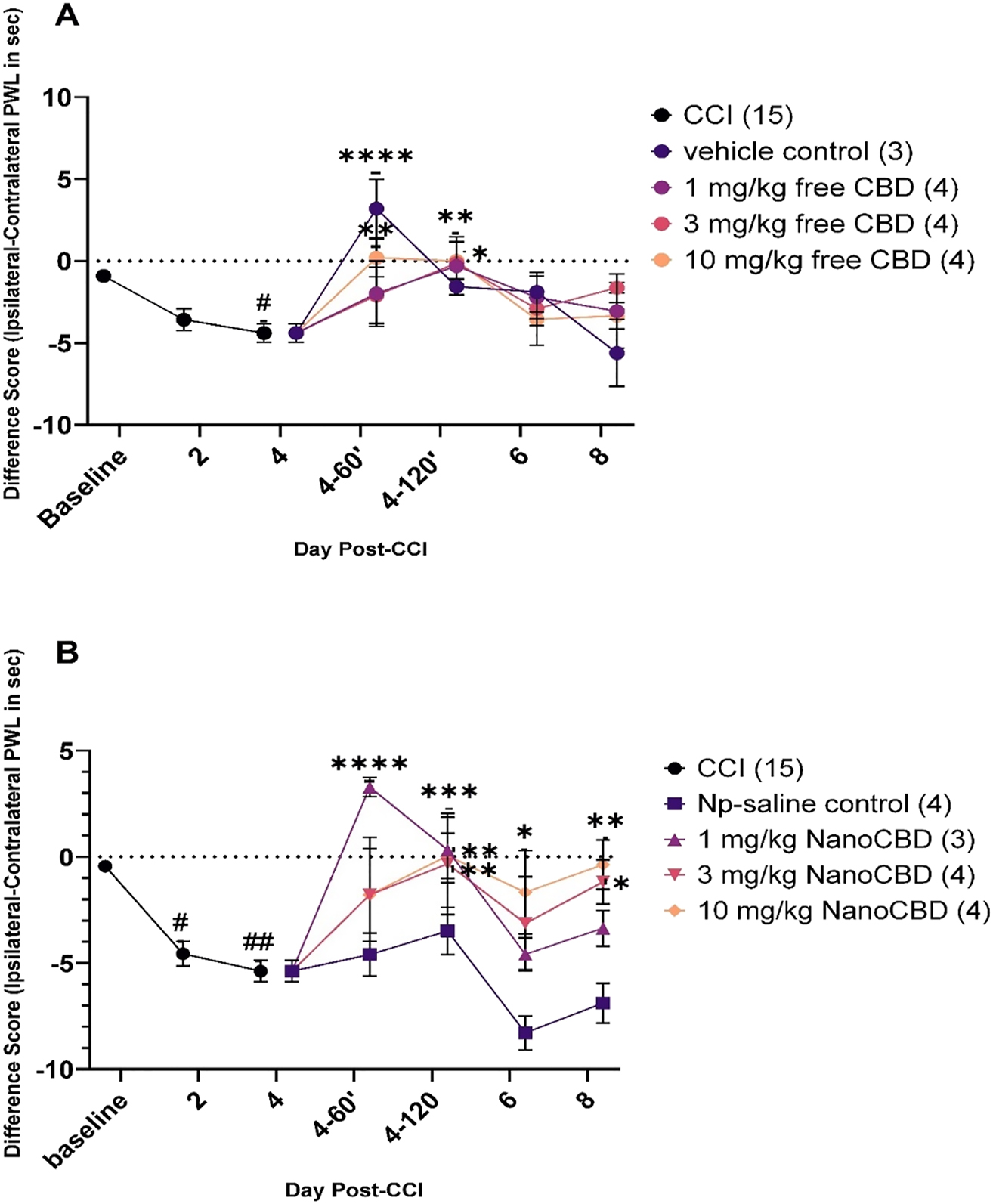

All rats receiving CCI surgery developed thermal hyperalgesia; the difference scores at days-2 and -4 (before treatment with CBD or mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation) were significantly different from baseline values (Figure 5A and B). Treatment with free CBD, 1 mg/kg CBD significantly provided analgesia to animals at 120′ post-injection as compared to the pre-injection difference score on day-4 post-CCI (p=0.0175) (Figure 5A). CBD at 3 mg/kg on day 4-120′ also significantly reduced hyperalgesia (p=0.0123), and 10 mg/kg CBD provided analgesia to animals on day 4-60′ and 4-120′ (1 h and 2 h post-injection) when compared to day-4 post-CCI (p=0.0060 and p=0.0093, respectively) (Figure 5A). The mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation significantly alleviated thermal hyperalgesia for a longer time than free CBD. On day 4, at 60′(day 4-60′) and 120′(day 4-120′) post-injection, there was significance between the difference scores at day-4 in the group that received 1 mg/kg mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation (p<0.001 and p=0.002, respectively), whereas 3 mg/kg mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation significantly reduced hyperalgesia at 120′ post-injection on day 4 (p=0.0024), as well as on day-8 (p=0.0154) as compared to the difference score on day-4 (pre-injection values) (Figure 5B). mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle (10 mg/kg) when injected on day-4 post-CCI resulted in a significant reduction in hyperalgesia at 120′ post-injection on day-4 (p=0.0009), as well as on day-6 (p=0.0404) and on day-8 (p=0.0026) when compared with the difference score of day-4 within the group (Figure 5B). Thus, free CBD in all tested doses had an analgesic effect that lasted for 2 h post-injection, whereas the mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation (3 and 10 mg/kg) provided a longer analgesic effect that lasted through day-8 post-CCI (4 days post-single injection).

Effect of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation (NanoCBD) and free CBD on thermal hyperalgesia induced by chronic constriction injury (CCI). Thermal hyperalgesia is expressed as the difference score (ipsilateral − contralateral paw withdrawal score in sec) to a noxious stimulus. Baseline latencies were determined before experimental treatment for all animals as the means of three separate trials, taken one, two-, and three-days pre-surgery (days -3, -2, and -1). All the rats underwent CCI surgery on the right hind paw on day 0. On day-4 post-CCI the rats received intraperitoneal injection of either CBD alone or mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation (NanoCBD) in one of three doses (1, 3, 10 mg/kg) with their respective controls. Statistical significance was determined with ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (A) Rats developed thermal hyperalgesia day-4 post-CCI surgery, #p=0.0120. On day-4 after the nociceptive behavior testing, rats were injected with CBD in doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg and vehicle control. On day 4-60′, 10 mg/kg CBD alleviated hyperalgesia as compared to difference score for day-4 (pre-injection), **p=0.0060. On day 4-120′, 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg CBD had a similar effect, *p=0.0175, *p=0.0123 and **p=0.0093. (B) Rats in this group also developed thermal hyperalgesia on day -2 and -4 post-CCI surgery (p=#0.0250, ##0.0023) and on day-4 after the nociceptive recording animals received treatment with mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation (NanoCBD) by i.p. injection in doses of 1, 3, 10 mg/kg and nanoparticle-saline control. 1 mg/kg NanoCBD resulted in a significant reduction in hyperalgesia on day 4-60′ and 4-120′ post-CCI, ****p<0.0001 and *p=0.0022. 3 mg/kg NanoCBD had an analgesic effect on day 4-120′ **p=0.0024 and on day-8 post-CCI *p=0.0154. 10 mg/kg NanoCBD also alleviated hypersensitivity on day 4-120′ ***p=0.0009, on day-6 *p=0.0404 and on day-8 **p=0.0026 post-CCI. All the error bars were plotted as±SEM and the number of rats in a group is indicated in parentheses.

Effect of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation on mechanical allodynia

Allodynia developed in CCI-operated rats as compared to sham-operated rats (see Supplementary Figure 4). Mechanical allodynia and hypersensitivity were measured using von Frey monofilaments 1 g and 15 g (force), respectively, on days-4 and -8 after the surgeries in the hind paw. A significant increase in response (hind paw withdrawals) to monofilament application was seen in the ipsilateral hind paw of CCI rats compared to sham rats with both 1 and 15 g force. With 1 g on day-4, the CCI group developed allodynia compared to sham (p=0.0165) (Supplementary Figure 4A), and with 15 g, hypersensitivity developed on day-4 and day-8 (p=0.0011 and 0.0193) (Supplementary Figure 4B). Mechanical allodynia and hypersensitivity measurements were taken on CCI rats before and after surgery and post-injection to determine the extent of allodynia and hypersensitivity that developed over time after treatment (Figure 6). All the animals developed allodynia and hypersensitivity after the CCI surgery. The significant value in each animal group with 1 and 15 g is p <0.0001 in Figure 6, where significance was determined from day-4 (pre-injection) vs. the baseline for the respective group. The treatment with 1 and 10 mg/kg CBD provided an analgesic effect and significantly reduced allodynia on day 4-120′ (2 h post-injection) (p=0.0308 and 0.0008, respectively) compared to day-4 post-CCI with 1 g force (Figure 6A). CBD alone in doses 1 and 10 mg/kg significantly reduced hypersensitivity on day 4-120′ (p=0.0067 and 0.0439, respectively) compared to day-4 post-CCI with 15 g force (Figure 6B). NanoCBD (mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation; 3 and 10 mg/kg) given on day-4 post-surgery had a significant reduction in allodynia on day-4-120′ post-surgery (p=0.0036) and in doses 1 and 10 mg/kg NanoCBD on day-8 post-surgery (p=0.0079 and 0.0003, respectively) with 1 g force (Figure 6C). mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation 10 mg/kg alleviated 15 g force-induced hypersensitivity on day 4-120′(p=0.0002) and provided a long-term reduction in hypersensitivity with doses 1 and 10 mg/kg on day-8 post-CCI compared to day-4 post-CCI (p=0.0096 and 0.0108, respectively) (Figure 6D).

Effect of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation on allodynia. On days -3 and -1 before CCI surgery the values were recorded to obtain baseline scores. After CCI surgery, allodynia was measured on day-4 followed by i.p injection with free CBD or mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation in 1, 3, 10 mg/kg doses with their respective controls. Statistical analysis was performed using 2-way ANOVA, and in case of significant results planned analysis was performed using Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests; a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All the scores were adjusted to baseline and plotted as % response rate. All the animals on day-4 (pre-injection) panels A, B, C and D had an increase in allodynia compared to baseline (pre-surgery) ****p<0.0001. (A) 1 and 10 mg/kg CBD alone showed significant decrease in % response rate with 1 g force (*p=0.308 and ***p=0.0008) compared to day-4 (pre-injection). (B) CBD alone at 1 and 10 mg/kg significantly reduced allodynia at 4-120′ (2 h post-injection) with 15 g force (*p=0.0067 and *p=0.0439, respectively) compared to day-4 (pre-injection). (C) 3 and 10 mg/kg NanoCBD (mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation) showed a significant reduction in allodynia on day-4-120′ with 1 g force, **p=0.0036. NanoCBD at 1 and 10 mg/kg provided a prolonged analgesic effect observable on day-8 post-CCI (day-4 post-injection), **p=0.0079 and ***p=0.0003, respectively, compared to day-4 (pre-injection), while 3 mg/kg NanoCBD did not show any significance reduction. (D) With 15 g force 10 mg/kg NanoCBD significantly reduced allodynia on day 4-120′ ***p=0.0002 post-injection, and 1 and 10 mg/kg NanoCBD provided prolonged reduction in % response rate on day-8 (day-2 post-injection) (**p=0.0096 and *p=0.0108, respectively) compared to day-4 pre-injection. The error bars are plotted as ±SEM and the number of rats per group is indicated in parentheses.

Biodistribution of free CBD vs. mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation in various rat brain regions

The quantitative assessment of the distribution of free CBD vs. mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation at 1 and 3 mg/kg, was conducted across distinct rat brain regions including right and left hippocampus, thalamus, periaqueductal gray (PAG), and ventral tegmental area (VTA). The results, plotted in Figure 7, illustrate the biodistribution of mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation was slightly higher in brain regions left hippocampus, PAG, and both right and left thalamus as compared to free CBD.

(A) CBD calibration curve, (B) biodistribution of CBD and CBD nanoformulation 1 mg/kg, (C) 3 mg/kg. Graphs are plotted between brain regions and area (mAu).

Gene expression analysis

We examined the gene expression levels of two relevant key modulators of neuropathic pain, Gpr158 and HDAC-5, both in the hippocampus and periaqueductal gray (PAG) regions of the rat brain at 5 days post i.p. administration of the 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, and 10 mg/kg mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation injection.

GPR158: CBD treatment (1/3/10 mg/kg) had a significant increase in G protein-coupled receptor 158 (Gpr158) gene expression by 7.0-fold (TAI=6.79±4.1), 0.7-fold (TAI=1.73±1.4), and 0.2-fold (TAI=1.2±0.12) in the right hippocampus (p=0.0124) (Figure 8A); 5.1-fold (TAI=6.27±4.2), 3-fold (TAI=4.03±4.5) in the left hippocampus (p=0.0147) (Figure 8B); and 10.3-fold (TAI=11.3±3.2), 0.7-fold (TAI=1.79±1.2) and 1-fold (TAI=2.01±1.3) in PAG regions (p=0.0353) (Figure 8C) compared to control (TAI=1.0), while CBD nanoformulation had no significant increase.

Gene expression with free CBD and mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle (CBD-NP) at doses 1/3/10 mg/kg. Gpr158 expression in (A) right hippocampus, (B) left hippocampus and (C) PAG brain region. HDAC5 expression in (D) right hippocampus, (E) left hippocampus and (F) PAG brain region. Error bars are plotted as ±SEM.

HDAC-5: An important regulator of neuropathic pain had increased gene expression in rats treated with free CBD. In the right hippocampal region (Figure 8D), 1 and 3 mg/kg CBD increased histone deacetylase 5 (HDAC-5) expression levels by 1.5-fold (TAI=2.48±1.1) and 0.5-fold (TAI=1.53±0.5). In the left hippocampal region (Figure 8E) with 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg CBD there was an increase of 4-fold (4.97±5.0), 2.9-fold (TAI=3.87±0.18), and 0.6-fold (1.65±0.49) and in the PAG region (Figure 8F) by 2.4-fold (TAI=3.43±3.3), 0.9-fold (TAI=1.85±0.9), and 0.7-fold (TAI=1.68±0.8) with respective to control animals (TAI=1.0). Whereas CBD nanoformulation in the right hippocampus in 3 mg/kg dose had a significant (p=0.0249) decrease in HDAC-5 gene expression by 0.3-fold (TAI=0.73±0.4), and in the other regions in doses 1, 3, 10 mg/kg had no significant change in the gene expression compared to control animals (TAI=1.0).

Discussion

mPEG-PLGA polymer was selected based on the rationale that polymeric nanoparticles enhance circulation time as opposed to free drug, which allows for increased accumulation of the drug in the target tissue. We have further evaluated the cytotoxicity of mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles by CCK-8 assay in our cell lines (BMVEC and NHA) and have found mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles to result in cell viability more than 50 % in doses up to 250 µg. For reference the cell viability graphs are added to the supplementary document (Figure 5). Table 2 shows that mPEG-PLGA polymer allowed encapsulation of 62.9 % drug (4.2 mg CBD from total 7.2 mg CBD) within the nanoparticles. Optimization may be possible to reduce the amount of unencapsulated drug and increase encapsulation efficiency. As evident from Figure 7, mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation exhibited a heightened degree of biodistribution to the brain tissue as compared to free CBD. mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles have also been shown to improve the cellular uptake of encapsulated drugs, and we observed same in our cellular uptake study, having a similar effect as the enhanced circulation time [50].

The optimal range for BBB permeability for nanoparticles is 50 nm [51] to 100 nm [49], with particles over 100 nm unable to pass through the brain extracellular space [52], while particles smaller than 5.5 nm are subjected to rapid renal clearance and thus will have less circulation time [53]. Our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles, with sizes less than 100 nm (Table 2), align with this optimal range and they efficiently crossed in vitro BBB model (Figure 4). The surface charge of the mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticle was −2.5 which was less than the mPEG-PLGA nanoparticle alone (−23.6), which could be due to CBD intercalating into the PEG chains, masking the net negative charge of the polymer. This may be important in enhancing the permeability of nanoparticles across negatively charged surface glycocalyx and basement membrane [54].

Furthermore, the size of our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation was stable for up to 14 days, which could be a property of PEG chains protecting the nanoparticles against protein degradation and it further increases the circulation time, and improves penetration across BBB [39].

The mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation was assessed in a CCI neuropathic pain model in doses 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg. A maximum of 10 mg/kg dose was selected based on the limitation of the total amount of CBD entrapped in the nanoparticles and the maximum intraperitoneal injection volume for the rats (<5 mL, NIH guidelines). Also, according to the literature, the most common dose of CBD used across in vivo studies was 5–20 mg/kg (0.4–1.6 mg/kg human equivalent dose). High levels of CBD used in in vivo studies did not result in a reduction in inflammation and additionally, the duration of CBD treatment did not necessarily predict efficacy [55]. The time points set to study the analgesic effect by thermal and mechanical allodynia measurements were 60 min (1 h) and 120 min (2 h) post injection and day -2 and -4 post-injection to study the prolonged effects. These timepoints were selected based on a study where two doses of CBD (1 and 20 mg/kg) were found to be dose-dependently absorbed, with its maximum absorption at 2 h after application [56].

The in vivo data (Figures 5 and 6) clearly shows that our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation had a dose-dependent increase in analgesic effect on day -6 and -8 post-CCI as compared to CBD alone, indicating that our nanoformulation provided prolonged analgesia through controlled and sustained release of CBD over time. This together with our biodistribution data in Figure 7 indicates enhanced bioavailability of our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoparticles.

Furthermore, we studied the effect of CBD and CBD nanoformulation on changes in gene expression in the hippocampus and PAG region because these regions are involved in propagation and modulation of pain [57]. The gene expression analysis was carried out on GPR158 and HDAC5 genes. According to the literature, GPR158 is upregulated in neuropathic pain and is involved in abnormal generation of action potential and also alters pain threshold [58]. HDAC5 upregulates spinal neuronal sensitization in neuropathic pain [59]. Figure 8 shows that our gene expression analysis data for the above-mentioned genes is in line with published findings. The upregulation of genes seen in CBD group was not surprising since these animals (euthanized on day-9 post-CCI) were once again experiencing pain behaviors at days 6 and 8 post-CCI, i.e., the CBD analgesic effect was transient, whereas there was a decrease in the mRNA expression levels for nociceptive genes in the animals treated with CBD nanoformulation. Thus, this shows long-term therapeutic analgesic effect of CBD nanoformulation in our study.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated potential benefits of using mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation over free CBD in alleviating neuropathic pain. Encapsulating CBD within a polymeric shell (mPEG-PLGA) has shown several advantages, such as small diameter ideal for crossing blood-brain barrier, protection against systemic degradation, increase circulation time of nanoparticles to ensure their delivery to the target tissue, use of lower dose of CBD to potentiate a prolonged therapeutic response. The data from CCI animals clearly shows mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation in doses 3 and 10 mg/kg provided a prolonged analgesic effect on day-6 and -8 post CCI (day-2 and -4 post-injection) compared to free CBD, which showed a short-term, transient effect. This supports that the mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformuation has a controlled and sustained release of CBD over time. However, an in vivo pharmacokinetics study is required to support our findings.

The downregulation of the studied genes with our mPEG-PLGA-CBD nanoformulation provides an insight for the long-term therapeutic effect of CBD, but further studies are needed to clearly understand the mechanism of CBD.

Funding source: National Institute of Drug Abuse

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant # 5R01DA047410-02

Funding source: University at Buffalo, Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research (CeCaR)

Award Identifier / Grant number: Unassigned

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the pilot grant from the Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research (CeCaR) that supports high-quality translational cannabis research at the University at Buffalo awarded to SM and TA.

-

Research ethics: Our Institutional IACUC Review Board approved the animal studies.

-

Informed consent: No human subjects – so Informed consent not needed.

-

Author contributions: Sana Qayum: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft preparation. Rebecca R. Schmitt: Methodology, writing – review and editing. Janvhi Suresh Machhar: Investigation, validation. Fnu Sonali: Validation. Caroline Bass: Supervision. Vijaya Prakash Krishnan Muthaiah: Supervision. Tracey A. Ignatowski: Methodology, validation, writing – review and editing, supervision. Supriya D. Mahajan: Supervision, writing – review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Funding support by NIH- National Institute of Drug Abuse (Grant # 5R01DA047410-02) and University at Buffalo's Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research (CeCaR) Award to SM is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Thiele, EA, Marsh, ED, French, JA, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M, Benbadis, SR, Joshi, C, et al.. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;391:1085–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30136-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Vučković, S, Srebro, D, Vujović, KS, Vučetić, Č, Prostran, M. Cannabinoids and pain: new insights from old molecules. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01259.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Milando, R, Friedman, A. Cannabinoids: potential role in inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019;20:167–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-018-0410-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Calapai, F, Cardia, L, Sorbara, EE, Navarra, M, Gangemi, S, Calapai, G, et al.. Cannabinoids, blood-brain barrier, and brain disposition. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12030265.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Costa, B, Trovato, AE, Comelli, F, Giagnoni, G, Colleoni, M. The non-psychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an orally effective therapeutic agent in rat chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;556:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Mlost, J, Bryk, M, Starowicz, K. Cannabidiol for pain treatment: focus on pharmacology and mechanism of action. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21228870.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Milando, R, Friedman, A. Cannabinoids: potential role in inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019;20:167–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-018-0410-5.Suche in Google Scholar

8. FDA. FDA and cannabis: research and drug approval process: FDA; 2023. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process#:∼:text=The%20agency%20has%2C%20however%2C%20approved,from%20a%20licensed%20healthcare%20provider.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Millar, SA, Maguire, RF, Yates, AS, O’Sullivan, SE. Towards better delivery of cannabidiol (CBD). Pharmaceuticals 2020;13:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13090219.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Huestis, MA. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodivers 2007;4:1770–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.200790152.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Štukelj, R, Benčina, M, Fanetti, M, Valant, M, Drab, M, kralj-iglic, V, et al.. Synthesis of stable cannabidiol (CBD) nanoparticles in suspension. Mater Tehnol 2019;53:543–9. https://doi.org/10.17222/mit.2018.253.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Harvey, AM. Classification of chronic pain – descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Clin J Pain 1995;11:1–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-199506000-00024.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Pain IAftSo. Neuropathic pain: IASP; 2017. Available from: www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy#Neuropathicpain.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Pain IAftSo. Definition of chronic neuropathic pain: IASP; 1974–2024. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/advocacy/definitions-of-chronic-pain-syndromes/.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Dowell, D, Ragan, KR, Jones, CM, Baldwin, GT, Chou, R. CDC clinical Practice Guideline for prescribing opioids for pain – United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep) 2022;71:1–95. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Angst Martin, S, Clark, JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology 2006;104:570–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200603000-00025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Berrocoso, E, Rey-Brea, R, Fernández-Arévalo, M, Micó, JA, Martín-Banderas, L. Single oral dose of cannabinoid derivate loaded PLGA nanocarriers relieves neuropathic pain for eleven days. Nanomedicine 2017;13:2623–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2017.07.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Mu, A, Weinberg, E, Moulin, DE, Clarke, H. Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain: review of the Canadian Pain Society consensus statement. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:844–52.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Dworkin, RH, O’Connor, AB, Audette, J, Baron, R, Gourlay, GK, Haanpää, ML, et al.. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:S3–14. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2009.0649.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Martín-Banderas, L, Alvarez-Fuentes, J, Durán-Lobato, M, Prados, J, Melguizo, C, Fernández-Arévalo, M, et al.. Cannabinoid derivate-loaded PLGA nanocarriers for oral administration: formulation, characterization, and cytotoxicity studies. Int J Nanomed 2012;7:5793–806. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s34633.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Xiong, W, Cui, T, Cheng, K, Yang, F, Chen, SR, Willenbring, D, et al.. Cannabinoids suppress inflammatory and neuropathic pain by targeting α3 glycine receptors. J Exp Med 2012;209:1121–34. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20120242.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Harris, HM, Sufka, KJ, Gul, W, ElSohly, MA. Effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on cisplatin-induced neuropathy in mice. Planta Med 2016;82:1169–72. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-106303.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. King, KM, Myers, AM, Soroka-Monzo, AJ, Tuma, RF, Tallarida, RJ, Walker, EA, et al.. Single and combined effects of Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol in a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:2832–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13887.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Abraham, AD, Leung, EJY, Wong, BA, Rivera, ZMG, Kruse, LC, Clark, JJ, et al.. Orally consumed cannabinoids provide long-lasting relief of allodynia in a mouse model of chronic neuropathic pain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45:1105–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0585-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Silva-Cardoso, GK, Lazarini-Lopes, W, Hallak, JE, Crippa, JA, Zuardi, AW, Garcia-Cairasco, N, et al.. Cannabidiol effectively reverses mechanical and thermal allodynia, hyperalgesia, and anxious behaviors in a neuropathic pain model: possible role of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors. Neuropharmacology 2021;197:108712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108712.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Thomas, BF, Gilliam, AF, Burch, DF, Roche, MJ, Seltzman, HH. Comparative receptor binding analyses of cannabinoid agonists and antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998;285:285–92.10.1016/S0022-3565(24)37365-3Suche in Google Scholar

27. Bisogno, T, Hanus, L, De Petrocellis, L, Tchilibon, S, Ponde, DE, Brandi, I, et al.. Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. Br J Pharmacol 2001;134:845–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0704327.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Crivelaro do Nascimento, G, Ferrari, DP, Guimaraes, FS, Del Bel, EA, Bortolanza, M, Ferreira-Junior, NC. Cannabidiol increases the nociceptive threshold in a preclinical model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2020;163:107808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107808.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Russo, EB, Burnett, A, Hall, B, Parker, KK. Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors. Neurochem Res 2005;30:1037–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. O’Sullivan, SE. An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol 2016;173:1899–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Laun, AS, Song, ZH. GPR3 and GPR6, novel molecular targets for cannabidiol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;490:17–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.165.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Brown, KJ, Laun, AS, Song, ZH. Cannabidiol, a novel inverse agonist for GPR12. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;493:451–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. De Petrocellis, L, Ligresti, A, Moriello, AS, Allarà, M, Bisogno, T, Petrosino, S, et al.. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 2011;163:1479–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01166.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Wang, X, Lin, C, Jin, S, Wang, Y, Peng, Y, Wang, X. Cannabidiol alleviates neuroinflammation and attenuates neuropathic pain via targeting FKBP5. Brain Behav Immun 2023;111:365–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.05.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Hernández-Giottonini, KY, Rodríguez-Córdova, RJ, Gutiérrez-Valenzuela, CA, Peñuñuri-Miranda, O, Zavala-Rivera, P, Guerrero-Germán, P, et al.. PLGA nanoparticle preparations by emulsification and nanoprecipitation techniques: effects of formulation parameters. RSC Adv 2020;10:4218–31. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ra10857b.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Tobío, M, Sánchez, A, Vila, A, Soriano, II, Evora, C, Vila-Jato, JL, et al.. The role of PEG on the stability in digestive fluids and in vivo fate of PEG-PLA nanoparticles following oral administration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2000;18:315–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00157-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Owens, DE3rd, Peppas, NA. Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 2006;307:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Zhou, Y, Peng, Z, Seven, ES, Leblanc, RM. Crossing the blood-brain barrier with nanoparticles. J Contr Release 2018;270:290–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.12.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Nance, EA, Woodworth, GF, Sailor, KA, Shih, TY, Xu, Q, Swaminathan, G, et al.. A dense poly(ethylene glycol) coating improves penetration of large polymeric nanoparticles within brain tissue. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:149ra19. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003594.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Dailey, LA, Jekel, N, Fink, L, Gessler, T, Schmehl, T, Wittmar, M, et al.. Investigation of the proinflammatory potential of biodegradable nanoparticle drug delivery systems in the lung. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2006;215:100–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2006.01.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Makadia, HK, Siegel, SJ. Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers 2011;3:1377–97. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym3031377.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Schmitt, RR, Mahajan, SD, Pliss, A, Prasad, PN. Small molecule based EGFR targeting of biodegradable nanoparticles containing temozolomide and Cy5 dye for greatly enhanced image-guided glioblastoma therapy. Nanomedicine 2022;41:102513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2021.102513.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Fraguas-Sánchez, AI, Torres-Suárez, AI, Cohen, M, Delie, F, Bastida-Ruiz, D, Yart, L, et al.. PLGA nanoparticles for the intraperitoneal administration of CBD in the treatment of ovarian cancer: in vitro and in ovo assessment. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12050439.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Persidsky, Y, Stins, M, Way, D, Witte, MH, Weinand, M, Kim, KS, et al.. A model for monocyte migration through the blood-brain barrier during HIV-1 encephalitis. J Immunol 1997;158:3499–510. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.158.7.3499.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Persidsky, Y, Ghorpade, A, Rasmussen, J, Limoges, J, Liu, XJ, Stins, M, et al.. Microglial and astrocyte chemokines regulate monocyte migration through the blood-brain barrier in human immunodeficiency virus-1 encephalitis. Am J Pathol 1999;155:1599–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65476-4.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Waldvogel, H, Bullock, JY, Synek, BJ, Curtis, MA, van Roon-Mom, W, Faull, R. The collection and processing of human brain tissue for research. Cell Tissue Bank 2008;9:169–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10561-008-9068-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Livak, KJ, Schmittgen, TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001;25:402–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Brookes, A, Jewell, A, Feng, W, Bradshaw, TD, Butler, J, Gershkovich, P. Oral lipid-based formulations alter delivery of cannabidiol to different anatomical regions in the brain. Int J Pharm 2023;635:122651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.122651.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Patel, T, Zhou, J, Piepmeier, JM, Saltzman, WM. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012;64:701–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2011.12.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Tsou, YH, Zhang, XQ, Zhu, H, Syed, S, Xu, X. Drug delivery to the brain across the blood-brain barrier using nanomaterials. Small 2017;13:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201701921.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Yokel, RA. Physicochemical properties of engineered nanomaterials that influence their nervous system distribution and effects. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med 2016;12:2081–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2016.05.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Thorne, RG, Nicholson, C. In vivo diffusion analysis with quantum dots and dextrans predicts the width of brain extracellular space. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:5567–72. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0509425103.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Soo Choi, H, Liu, W, Misra, P, Tanaka, E, Zimmer, JP, Itty, IB, et al.. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol 2007;25:1165–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1340.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Zhang, L, Fan, J, Li, G, Yin, Z, Fu, BM. Transcellular model for neutral and charged nanoparticles across an in vitro blood-brain barrier. Cardiovasc Eng Technol 2020;11:607–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13239-020-00496-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Henshaw, FR, Dewsbury, LS, Lim, CK, Steiner, GZ. The effects of cannabinoids on pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines: a systematic review of in vivo studies. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2021;6:177–95. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2020.0105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Dumbraveanu, C, Strommer, K, Wonnemann, M, Choconta, JL, Neumann, A, Kress, M, et al.. Pharmacokinetics of orally applied cannabinoids and medical Marijuana extracts in mouse nervous tissue and plasma: relevance for pain treatment. Pharmaceutics 2023;15:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15030853.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Guindon, J, Hohmann, AG. The endocannabinoid system and pain. CNS Neurol Disord: Drug Targets 2009;8:403–21. https://doi.org/10.2174/187152709789824660.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Stephens, KE, Zhou, W, Renfro, Z, Ji, Z, Ji, H, Guan, Y, et al.. Global gene expression and chromatin accessibility of the peripheral nervous system in animal models of persistent pain. J Neuroinflammation 2021;18:185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-021-02228-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Gu, P, Pan, Z, Wang, XM, Sun, L, Tai, LW, Cheung, CW. Histone deacetylase 5 (HDAC5) regulates neuropathic pain through SRY-related HMG-box 10 (SOX10)-dependent mechanism in mice. Pain 2018;159:526–39. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001125.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nipt-2024-0008).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Brief Report

- Elevated cerebral oxygen extraction in patients with post-COVID conditions

- Review Articles

- Build muscles and protect myelin

- Cannabis use, oral dysbiosis, and neurological disorders

- Sedation with midazolam in the NICU: implications on neurodevelopment

- The challenges to detect, quantify, and characterize viral reservoirs in the current antiretroviral era

- Research Articles

- Biodegradable cannabidiol: a potential nanotherapeutic for neuropathic pain

- Motivational dysregulation with melanocortin 4 receptor haploinsufficiency

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Brief Report

- Elevated cerebral oxygen extraction in patients with post-COVID conditions

- Review Articles

- Build muscles and protect myelin

- Cannabis use, oral dysbiosis, and neurological disorders

- Sedation with midazolam in the NICU: implications on neurodevelopment

- The challenges to detect, quantify, and characterize viral reservoirs in the current antiretroviral era

- Research Articles

- Biodegradable cannabidiol: a potential nanotherapeutic for neuropathic pain

- Motivational dysregulation with melanocortin 4 receptor haploinsufficiency