Abstract

Although parity-time (PT)-symmetric systems can exhibit real spectra in the exact PT-symmetry regime, PT-symmetry is actually not a necessary condition for the real spectra. Here, we show that non-PT-symmetric photonic crystals (PCs) carrying Dirac-like cone dispersions can always exhibit real spectra as long as the average non-Hermiticity strength within the unit cell for the eigenstates is zero. By building a non-Hermitian Hamiltonian model, we find that the real spectra of the non-PT-symmetric system can be explained using the concept of pseudo-Hermiticity. We demonstrate using effective medium theories that, in the long-wavelength limit, such non-PT-symmetric PCs behave like the so-called complex conjugate medium (CCM) whose refractive index is real but whose permittivity and permeability are complex numbers. The real refractive index for this effective CCM is guaranteed by the real spectrum of the PCs, and the complex permittivity and permeability come from non-PT-symmetric loss-gain distributions. We show some interesting phenomena associated with CCM, such as the lasing effect.

1 Introduction

Hermitian Hamiltonian can describe ideal closed physical systems, in which the total energy is conserved and eigenfrequencies are purely real. However, nonconservative elements are ubiquitous in classical wave systems, and we need to introduce the concept of non-Hermiticity to describe such systems. In the past decades, there is a surge of interest in studying the physics of non-Hermitian systems [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] and the parity-time (PT)-symmetric system, which was first introduced in quantum mechanics [1], is the most popular one. A Hamiltonian H is said to be PT-symmetric if [H, PT]=0, where the operator P represents a space reflection and the operator T represents a time reversal. PT-symmetric systems have been realized in optics and photonics [8], [9], [10]. In an optical system, the loss-gain (represented by the imaginary part of the refractive index) distribution is PT-symmetric if the complex-valued refractive index satisfies n(x)=n*(−x).

The most intriguing property of a PT-symmetric Hamiltonian is that it can exhibit real spectra in the exact PT-symmetry regime [2]. As we change the parameters of the Hamiltonian, such as the loss-gain strength, it may go into the broken PT-symmetry regime, and the eigenvalues form complex conjugate pairs. The symmetry-breaking point, marking the phase transition in the eigenvalue spectrum, is the exceptional point (EP) [11], [12]. However, PT-symmetry is not a necessary condition for achieving a real spectrum [13] and some studies about realizing real spectra in non-PT-symmetric systems have been presented recently [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. It has been proven that the necessary condition for the real spectrum is pseudo-Hermiticity [13]. A Hamiltonian H satisfying ηHη−1=H†, where η is an invertible linear Hermitian operator, is defined as pseudo-Hermitian Hamiltonian (see Supplementary Note 1 for details). Real spectra realized in non-PT-symmetric systems can be explained using the concept of pseudo-Hermiticity.

Achieving the real spectra in a non-PT-symmetric photonic crystals (PC) is highly desirable as, from an effective medium (EM) theory (EMT) point of view [19], realizing the real spectra in certain regions of the Brillouin zone can lead to new applications. For example, one can then realize a complex conjugate medium (CCM) [20], [21], [22], which carries many unusual phenomena, including coherent perfect absorption and lasing [23], and negative refraction [24]. The refractive index of CCM is a real number, but the permittivity and permeability can both be complex numbers in general [20]. From the EMT point of view, achieving a CCM using a PC requires the non-Hermitian PC to exhibit real frequency bands near the Brillouin zone center (Γ point) as the effective refractive index is real.

To understand the underlying physics, we build a two-band non-Hermitian Hamiltonian model for non-PT-symmetric PCs. We show that the model Hamiltonian is pseudo-Hermitian as long as the average non-Hermiticity strength (to be defined below) within the unit cell for the relevant states is zero and this condition can always be achieved in PCs that have Dirac-like cone dispersions. Consequently, real spectra can be realized in a particular frequency range, implying that the effective refractive index is real. In the long-wavelength limit, the scattering properties of such an inhomogeneous PC behave indeed like a homogeneous CCM.

2 Two-band non-Hermitian Hamiltonian model

As shown in Figure 1A (inset), we consider a two-dimensional (2D) PC with rods arranged in a square lattice in the x−y plane. Within the unit cell with a lattice constant a, the rod (domain A, the blue region) having a radius rc and relative permittivity εA=εcr+iγ is embedded in a background medium (domain B, the gray region) with relative permittivity εB=εbr+iℓrγ. We set εbr=1 in the calculation and the relative permeability μ of both media as 1.0. The positive (negative) sign of γ indicates that the rod consists of a lossy (active) medium. A positive sign of ℓr indicates that the rod and background are either both lossy or both active, whereas a negative sign means that one is lossy and the other is active.

Properties of the Dirac-like cone.

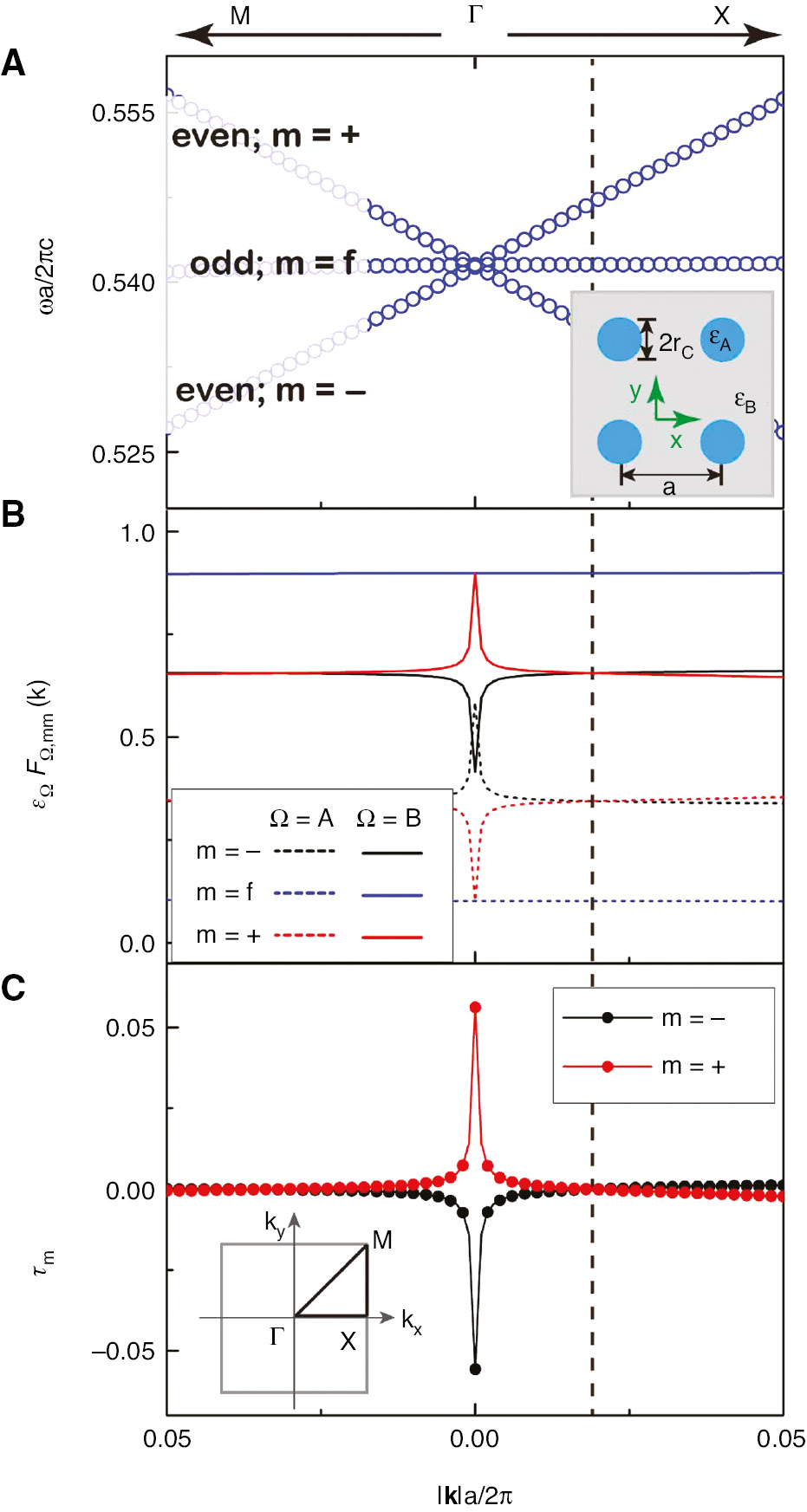

(A) Band dispersions of Hermitian PC (γ=0) calculated using COMSOL. (B) Eigenmode profiles of top band m=+ (even mode), flat band m=f (odd mode), and bottom band m=−(even mode). (C) Average non-Hermiticity τm when gain-to-loss ratio ℓr=−0.15235. The vertical dashed line denotes the intersection: FΩ,++=FΩ,−−. (A, inset) Schematic of 2D PC constructed with cylinders (the blue areas); the gray area denotes air. (C, inset) First Brillouin zone of the square lattice. The parameters used are rc=0.1999a, εA=12.5+iγ, and εB=1+iγℓr.

We study the PC in the transverse-magnetic polarization, where electric field

where c is the speed of light and ωkn and pkn are the eigenfrequencies and eigenvectors of the non-Hermitian system (γ≠0), respectively. The matrices in Equation (1) are

where Ω denotes the rod (|r|<rc) or air (|r|>rc) domain. FΩ,mm′ (m≠m′) expresses the overlapping between two different eigenmodes in the domain Ω, and FΩ,mm expresses the amplitude distribution of the eigenmode m in the domain Ω.

where εA=εcr denotes the relative permittivity of the rod domain and εB=εbr=1 represents the relative permittivity of the air domain. For convenience, we can omit the subscript k for simplicity and rewrite Equation (1) as H·pn=Wnpn, where Wn=(ωn/c)2 and

From Equation (2), we know that the function FΩ,mm′ involves the spatial integrations of eigenfunctions of Hermitian systems; hence, the symmetry of the eigenmode profile plays an important role here. In our system, we choose the center of the rod as origin. The even/odd symmetry characters are labeled in Figure 1A [27], [29]. As the two linearly dispersive bands (m=±) are even, whereas the flat band (m=f) is an odd mode, the matrix elements FΩ,+f and FΩ,−f are all zero, implying that there is no coupling between the flat band and the linear bands. Therefore, we can decouple the flat band from the Hamiltonian model and write the Hamiltonian as a 2×2 matrix (see Supplementary Note 3 for details):

where

is a real number, representing the average non-Hermiticity of state m within the primitive unit cell, and

is a complex number, representing an overlapping between the two eigenmodes. According to Equation (5), the values of τ± depend not only on the distributions of non-Hermiticity (described by ℓr) in the unit cell but also on the eigenmode profiles (as described by FΩ,mm). The average non-Hermiticity τ± is very important, as it can determine whether we can obtain the real spectra in a non-Hermitian PC (see Supplementary Note 4). To see this, we set the average non-Hermiticity τ±=0; then, the Hamiltonian (4) becomes

where β=1+γ2|κ|2 is a real number.

Near the Γ point, we can expand the eigenfrequencies of the two linear bands for a small k≡|k| into

where Cg=2ωdvg/c2, Wd=(ωd/c)2, and ωd is the Dirac-like point frequency. The band slope vg can be obtained from numerical results in Figure 1A, where we assume vg is a constant along all directions in the wave vector space, which is an excellent approximation of a conical dispersion at k=0 for a system with C4v symmetry [29]. The corresponding eigenvalues are

EPs appear when the value under the square root is zero and form a ring in the wave vector space with a radius

Before proceeding to the next subsection, the Hamiltonian (7) deserves more comments. Using the linear operator

the Hamiltonian (7) satisfies

Implying that the Hamiltonian is pseudo-Hermitian and the operator η transforms the system with non-Hermiticity γ into its complex conjugate-paired system −γ. Unlike the traditional PT-symmetric system, the loss-gain distribution of our PC system is not PT-symmetric in real space, n(x)≠n*(−x).

3 Results

3.1 Realizing the pseudo-Hermitian condition using a Dirac-like cone

The previous section shows that, by setting the average non-Hermiticity τ±=0, the non-Hermitian Hamiltonian will become pseudo-Hermitian, and we can obtain the real spectra. For a PT-symmetric PC, τ±=0 is automatically satisfied as the distributions of loss and gain within the unit cell are equal (see Supplementary Note 2 for details) [30]. However, for a non-PT-symmetric PC, achieving τ±=0 is not an easy task. Now, we will show that, for a PC exhibiting a Dirac-like cone in the Brillouin zone center, we can always achieve the pseudo-Hermitian condition τ±=0.

The eigenmode

for both m=+ and m=−. Equation (12) shows that, to determine the value of ℓr, we must tune the system parameters so that the system satisfies FΩ,++=FΩ,−−.

The band dispersions near the Dirac-like cone are shown in Figure 1A, and the quantities εΩFΩ,mm of the three bands are plotted in Figure 1B. We can see that there is an intersection (FΩ,++=FΩ,−−) at kxa/2π=0.019 (marked by the dashed line), and then Equation (12) can be used to determine the gain-to-loss ratio, which is found to be ℓr=−0.15235. Physically, the existence of such an intersection is guaranteed by the band inversion in the Dirac-like cone [25]. The condition FΩ,++=FΩ,−− can always be achieved near the Dirac-like cone (see Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Figure S1 for details); therefore, τ±=0 is realized at kxa/2π=0.019 as shown in Figure 1C. Note that the quantity FΩ,mm should be a function of k, but near the Dirac-like cone (except the Γ point), this quantity is almost a constant (as shown in Figure 1B), as the eigenmodes of the same point group are almost unchanged when the change of k is small. We can therefore assume that the values τm, and κ are independent of k in the considered Brillouin zone region. As shown in Figure 1C, by tuning ℓr=−0.15235, we can obtain τ±≈0 near the Dirac-like cone (except very close to the Γ point, where τ−≈−τ+). We can demonstrate that the pseudo-Hermitian condition at the Γ point is τ−=−τ+, which is less demanding than other points, as the symmetry at the Γ point is higher than that at other k points (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). Therefore, the pseudo-Hermitian criterion is approximately fulfilled for all the k points near the Dirac-like cone.

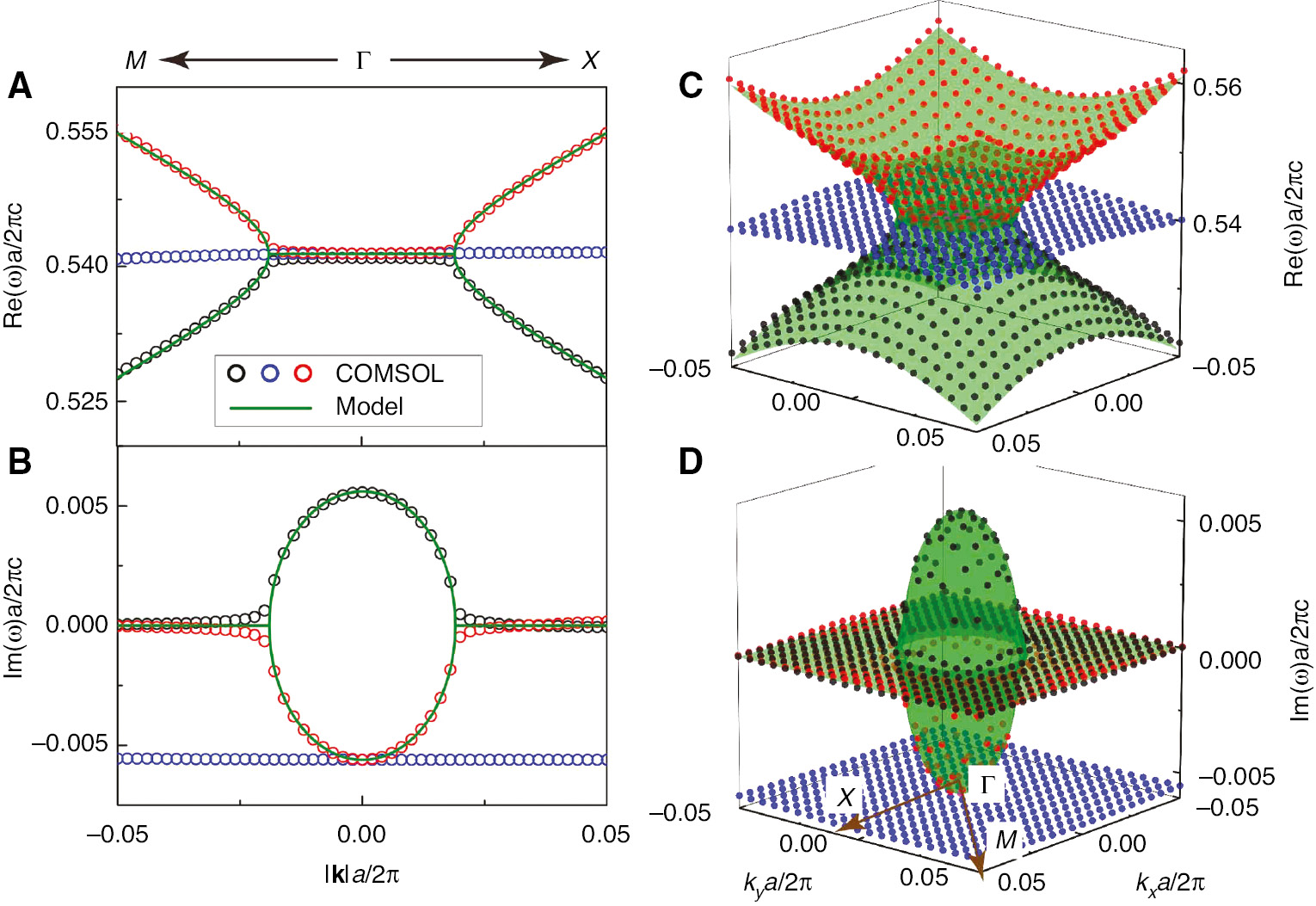

Now, we can calculate the band structures of a PC with loss-gain ratio ℓr=−0.15235 to verify the validity of the pseudo-Hermitian Hamiltonian shown in Equation (7). We choose a non-Hermitian strength γ=+0.367 and plot the complex band structure along the M−Γ−X direction in Figure 2A and B. The analytical results are shown by solid green lines, and the numerically results are calculated using COMSOL by open circles. The validity of our non-Hermitian Hamiltonian model is demonstrated by the good agreement between the two sets of results. We can see that EPs appear in both Γ−X and Γ−M directions. To show that these EPs form a ring in k space, we plot the three-dimensional complex band structure in Figure 2C and D using Equation (9) and COMSOL as shown by green surfaces (analytical results) and filled dots (numerical results), respectively. The analytical model (9) predicts that k=kc=0.019(2π/a) form a ring of EPs, which is verified by COMSOL results. The eigenfrequencies inside the ring form complex-conjugate pairs, and outside the ring, we obtain the entirely real spectra.

Band dispersions of pseudo-Hermitian bands.

The real parts (A and C) and the imaginary parts (B and D) of the complex eigenfrequencies along the M−Γ−X direction and in the 2D Bloch k space. Open circles and solid dots are calculated using COMSOL, whereas green solid lines and green surfaces are calculated using the analytical model (vg=0.295c and |κ|2=0.00318). The bands outside the ring are entirely real. The parameters of 2D PC are rc=0.1999a, εA=12.5+iγ, εB=1+iγℓr, γ=+0.367, and ℓr=−0.15235.

However, entirely real spectra do not mean loss-gain compensation. To see this, we compare the system with non-Hermiticity γ+=+0.367 with its complex conjugate-paired system γ−=−0.367. If we replace γ+ by γ−, the eigenfrequencies described by Equation (9) are the same, but the Hamiltonians (7) are different as described by Equation (11). In other words, these two systems (γ+ and γ−) possess the same band dispersion, but the eigenfunctions are different (see Supplementary Note 7 for details); hence, they can display different scattering behaviors, as we will show later.

3.2 Real spectra and CCM

The optical properties of an Hermitian PC carrying a Dirac-like cone in the Brillouin zone center can be described using an effective refractive index medium in which the effective permittivity and permeability are simultaneously zero at the Dirac-like point frequency. We have shown in the previous subsection that, by setting the average non-Hermiticity as zero, the spectra are real outside the ring of the EPs. It is interesting to see what type of EM corresponds to the non-PT-symmetric PC with real spectra. In this section, we will establish the EMT of non-Hermitian PC for describing the physics near the Γ point and study the related scattering properties.

We calculate the effective parameters using a boundary field averaging method [31]. Assuming that the wave

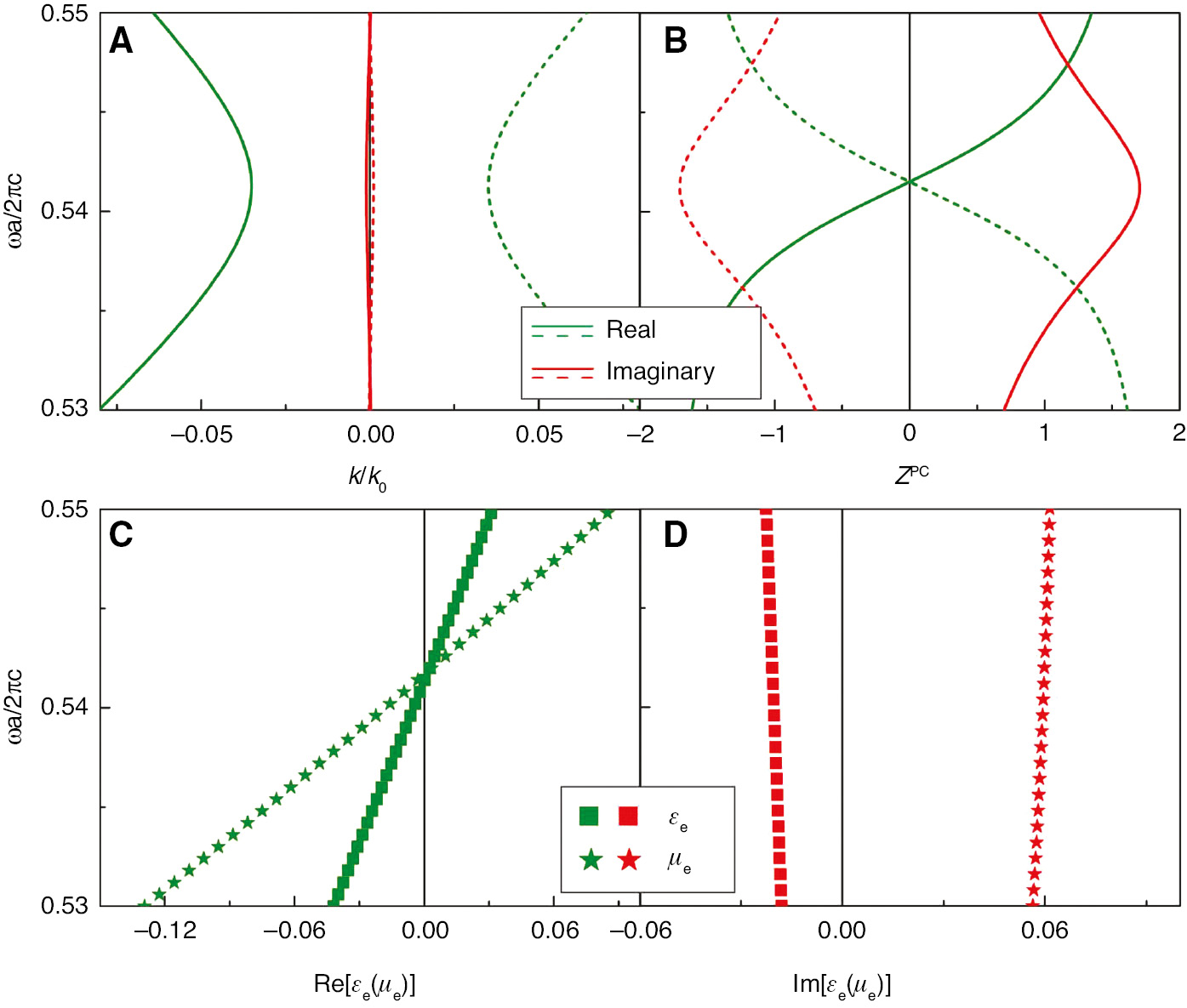

where EPC and HPC are obtained from the eigenfields at the incident boundary I (the boundary of the unit cell along y direction). When we calculate effective parameters of the non-Hermitian PC as functions of frequency, the frequencies should take real-valued numbers, as in actual experiments the incident light comes with a real frequency. Therefore, within the PC, the eigenfields EPC and HPC are obtained by solving the “complex-valued k(ω) vs. real-valued ω” band structures [32]. In Figure 3A, we plot the “complex-valued k(ω)” band structure of the non-Hermitian 2D PC calculated using COMSOL. We note that the imaginary parts of the bands (red lines) are almost zero, and for real bands, the “complex-valued k(ω)” band structure should agree well with the “complex-valued ω(k) vs. real-valued k” band structure (see Supplementary Figure S7 for details). In Figure 3B, we plot ZPC defined in Equation (13) for the bands with positive (dashed lines) and negative (solid lines) wave vectors, respectively, in Figure 3A. The effective permittivity and permeability can be calculated as follows:

Effective parameters obtained from the real spectra as shown in Figure 2.

(A) Complex-valued k(ω)/k0 band and (B) averaged field ratio ZPC calculated numerically from COMSOL. Bands with positive and negative wave vectors are represented by dashed and solid lines, respectively. The real (green) and imaginary (red) parts of the effective parameters εe and μe are plotted in squares and stars, respectively (C and D).

We plot the real and imaginary parts of εe(μe) by squares (stars) in Figure 3C and D, respectively. Note that the effective parameters obtained from the two bands (k and -k) are the same.

It is known that, for the Hermitian case, the effective parameters of the PC are real and approach zero near the Dirac-like point frequency, indicating that the PC can be treated as a zero refractive index medium [25]. When we introduce loss and gain into the PC, the effective parameters εe and μe obtain imaginary parts as shown in Figure 3D. However, we note that the effective refractive index ne2=εeμe=(k/k0)2 is a real number, where k0 is the wave vector in air. This automatically indicates that the inhomogeneous PCs behave like the homogeneous CCM whose refractive index is real but whose permittivity and permeability are complex numbers. The real effective refractive index does not necessarily imply a simple loss-gain compensation, as εe and μe have imaginary parts. Also, it can be proven that

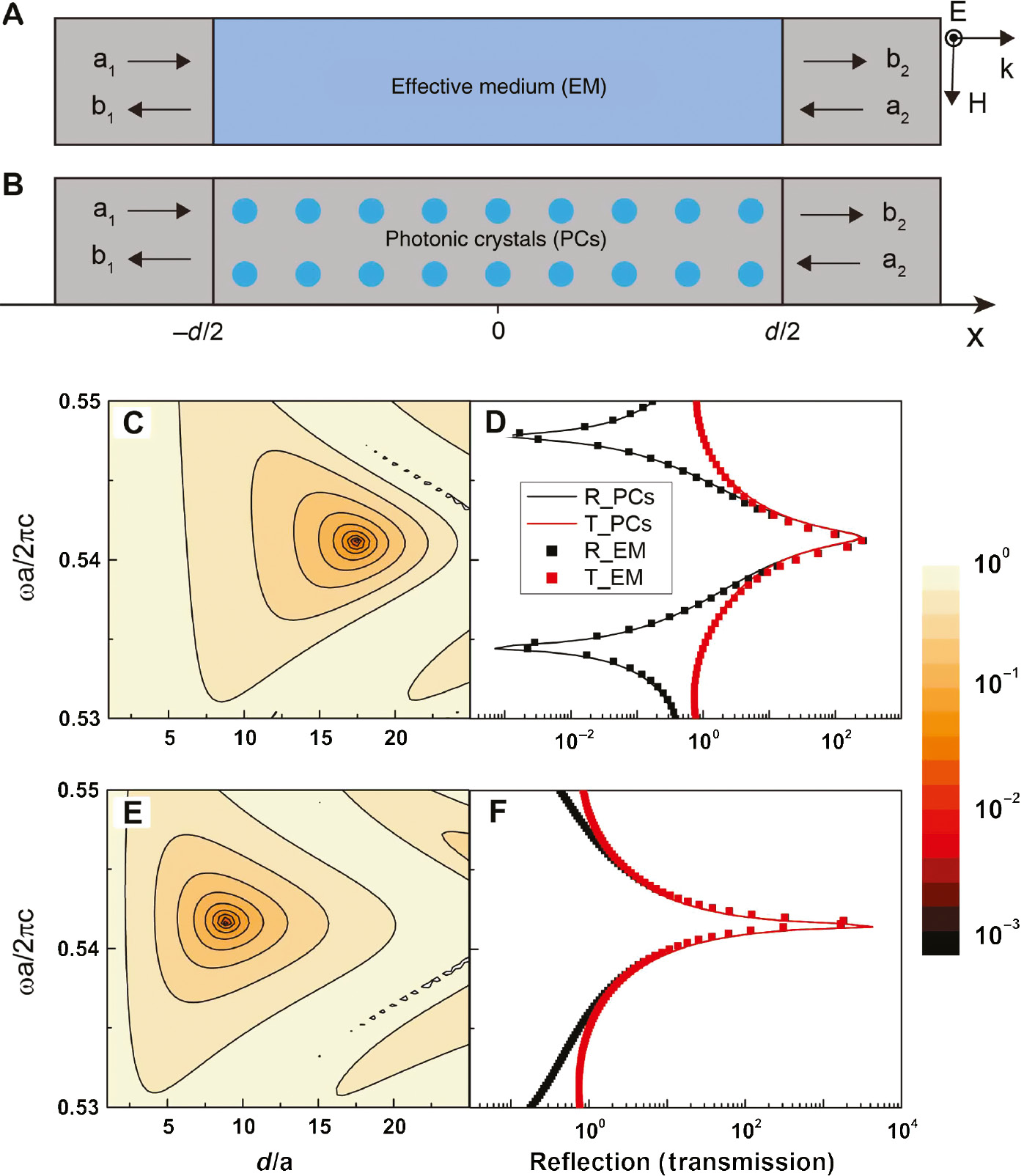

The complex conjugate-paired systems (γ+ and γ−) have dramatically different effects on the scattering properties of electromagnetic waves. To demonstrate this, we consider a slab with thickness d formed by the homogeneous EM with the parameters εe and μe, as shown in Figure 4A. We assume that plane waves propagate along the x direction with an electric field polarized along the z direction and that the EM slab (blue region) is embedded in air (gray region). The electric field in the air can be written as E(x)= a1exp(ik0x)+b1exp(−ik0x) for x<−d/2 and as E(x)=b2exp(ik0x)+a2exp(−ik0x) for x>d/2. The amplitudes of incoming-propagating waves (a1, a2)T and outcoming-propagating waves (b2, b1)T are related by a scattering matrix [23].

Scattering properties of CCM with effective parameters as shown in Figure 3.

Schematics of wave scattering in (A) EM slab and (B) PC slab. The contour plot of the value 1/Max|λ±| in the (ω, d) plane for EM slab with parameters (C)

where r and t represent the transmission and reflection coefficients of the slab for normal incident plane waves. The elements in S are

where k=k0ne is the wave vector in the slab. The corresponding eigenvalues of the S matrix are

These eigenvalues can be used to determine the S matrix poles (1/Max|λ±|→0) where lasing occurs. For a slab composed of CCM [Im(ne)=Im(k/k0)=0], kd is a real number. For the S matrix to have poles, we require M22=0; therefore, we obtain

To satisfy Equation (19), μe must be an imaginary number. Figure 3C and D shows the effective parameters of PCs with non-Hermiticity γ+=+0.367. We find

Figure 4C and E shows the contour plots of 1/Max|λ±| in the (ωa/2πc, d/a) plane for EM slab with

4 Discussion

In this work, we find that a non-PT-symmetric PC can have real spectra when the average non-Hermiticity within the unit cell is zero. We showed that the pseudo-Hermitian condition (τ±=0) can always be fulfilled in two-component PCs carrying Dirac-like cones with bands arising from monopolar and dipolar resonances. These non-Hermitian PCs carrying Dirac-like cones can be used to realize CCM near the Dirac-like point frequency, where a real spectrum guarantees a real refractive index and the non-Hermiticity guarantees complex permittivity and permeability.

Funding source: Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee

Award Identifier / Grant number: AoE/P-02/12, N_HKUST608/17, 16303119, and C6013-18G

Funding statement: This work was supported by the Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, Hong Kong (grant nos. AoE/P-02/12, N_HKUST608/17, 16303119, and C6013-18G, Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100002920) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 11761161002, 61775243, Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100001809). K.D. acknowledges the funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. We would like to thank Prof. Zhao Qing Zhang and Dr. Ruoyang Zhang for helpful discussions.

References

[1] Bender CM, Boettcher S. Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Phys Rev Lett 1998;80:5243–6.10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.5243Search in Google Scholar

[2] Bender CM, Brody DC, Jones HF. Complex extension of quantum mechanics. Phys Rev Lett 2002;89:270401.10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.270401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Mostafazadeh A. Exact PT-symmetry is equivalent to Hermiticity. J Phys A Math Gen 2003;36:7081–91.10.1088/0305-4470/36/25/312Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bender CM. Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Rep Prog Phys 2007;70:947–1018.10.1088/0034-4885/70/6/R03Search in Google Scholar

[5] Rotter I. A non-Hermitian Hamilton operator and the physics of open quantum systems. J Phys A Math Theor 2009;42:153001.10.1088/1751-8113/42/15/153001Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mostafazadeh A. Pseudo-Hermitian representation of quantum mechanics. Int J Geomet Methods Mod Phys 2010;7:1191–306.10.1142/S0219887810004816Search in Google Scholar

[7] Moiseyev N. Non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.10.1017/CBO9780511976186Search in Google Scholar

[8] Makris KG, El-Ganainy R, Christodoulides DN, Musslimani ZH. Beam dynamics in PT-symmetric optical lattices. Phys Rev Lett 2008;100:103904.10.1109/CLEOE-IQEC.2013.6801815Search in Google Scholar

[9] Rüter CE, Makris KG, El-Ganainy R, Christodoulides DN, Segev M, Kip D. Observation of parity-time symmetry in optics. Nat Phys 2010;6:192–5.10.1038/nphys1515Search in Google Scholar

[10] Regensburger A, Bersch C, Miri M-A, Onishchukov G, Christodoulides DN, Peschel U. Parity-time synthetic photonic lattices. Nature 2012;488:167–71.10.1038/nature11298Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Heiss WD. The physics of exceptional points. J Phys A Math Theor 2012;45:444016.10.1088/1751-8113/45/44/444016Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ding K, Ma G, Xiao M, Zhang ZQ, Chan CT. Emergence, coalescence, and topological properties of multiple exceptional points and their experimental realization. Phys Rev X 2016;6:021007.10.1103/PhysRevX.6.021007Search in Google Scholar

[13] Mostafazadeh A. Pseudo-Hermiticity versus PT symmetry: the necessary condition for the reality of the spectrum of a non-Hermitian Hamiltonian. J Math Phys 2002;43:205–14.10.1063/1.1418246Search in Google Scholar

[14] Cannata F, Junker G, Trost J. Schrodinger operators with complex potential but real spectrum. Phys Lett A 1998;246:219–26.10.1016/S0375-9601(98)00517-9Search in Google Scholar

[15] Tsoy EN, Allayarov IM, Abdullaev FK. Stable localized modes in asymmetric waveguides with gain and loss. Opt Lett 2014;39:4215–8.10.1364/OL.39.004215Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Makris KG, Musslimani ZH, Christodoulides DN, Rotter S. Constant-intensity waves and their modulation instability in non-Hermitian potentials. Nat Commun 2015;6:7257.10.1038/ncomms8257Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Nixon S, Yang J. All-real spectra in optical systems with arbitrary gain-and-loss distributions. Phys Rev A 2016;93:031802.10.1103/PhysRevA.93.031802Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hang C, Gabadadze G, Huang G. Realization of non-PT-symmetric optical potentials with all-real spectra in a coherent atomic system. Phys Rev A 2017;95:023833.10.1103/PhysRevA.95.023833Search in Google Scholar

[19] Choy TC. Effective medium theory: principles and applications. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2015.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198705093.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

[20] Dragoman D. Complex conjugate media: alternative configurations for miniaturized lasers. Opt Commun 2011;284:2095–8.10.1016/j.optcom.2010.12.069Search in Google Scholar

[21] Imran A, Illahi A. On the effects of complex conjugate medium on TM scattering by a strip. J Electromagn Anal Appl 2011;3:267–70.10.4236/jemaa.2011.37043Search in Google Scholar

[22] Basiri A, Vitebskiy I, Kottos T. Light scattering in pseudopassive media with uniformly balanced gain and loss. Phys Rev A 2015;91:063843.10.1103/PhysRevA.91.063843Search in Google Scholar

[23] Bai P, Ding K, Wang G. Simultaneous realization of a coherent perfect absorber and laser by zero-index media with both gain and loss. Phys Rev A 2016;94:063841.10.1103/PhysRevA.94.063841Search in Google Scholar

[24] Xu Y, Fu Y, Chen H. Electromagnetic wave propagations in conjugate metamaterials. Opt Express 2017;25:4952.10.1364/OE.25.004952Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Huang X, Lai Y, Hang ZH, Zheng H, Chan CT. Dirac cones induced by accidental degeneracy in photonic crystals and zero-refractive-index materials. Nat Mater 2011;10:582–6.10.1038/nmat3030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Zhen B, Hsu CW, Igarashi Y. Spawning rings of exceptional points out of Dirac cones. Nature 2015;525:354–8.10.1038/nature14889Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Sakoda K. Optical properties of photonic crystals. In: Number 80 in Springer Series in Optical Sciences, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2005.10.1007/b138376Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ding K, Zhang ZQ, Chan CT. Coalescence of exceptional points and phase diagrams for one-dimensional PT-symmetric photonic crystals. Phys Rev B 2015;92:235310.10.1103/PhysRevB.92.235310Search in Google Scholar

[29] Sakoda K. Proof of the universality of mode symmetries in creating photonic Dirac cones. Opt Express 2012;20:25181.10.1364/OE.20.025181Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Szameit A, Rechtsman MC, Bahat-Treidel O, Segev M. PT-symmetry in honeycomb photonic lattices. Phys Rev A 2011;84:021806.10.1103/PhysRevA.84.021806Search in Google Scholar

[31] Andryieuski A, Ha S, Sukhorukov AA, Kivshar YS, Lavrinenko AV. Bloch-mode analysis for retrieving effective parameters of metamaterials. Phys Rev B 2012;86:035127.10.1103/PhysRevB.86.035127Search in Google Scholar

[32] Davanco M, Urzhumov Y, Shvets G. The complex Bloch bands of a 2D plasmonic crystal displaying isotropic negative refraction. Opt Express 2007;15:9681.10.1364/OE.15.009681Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0389).

©2019 C.T. Chan et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Reviews

- Optical binding of nanoparticles

- Recent advances in nano-photonic techniques for pharmaceutical drug monitoring with emphasis on Raman spectroscopy

- Optically responsive delivery platforms: from the design considerations to biomedical applications

- Research Articles

- Beyond dipolar Huygens’ metasurfaces for full-phase coverage and unity transmittance

- Bound states in the continuum and strong phase resonances in integrated Gires-Tournois interferometer

- Improving the efficiency of silicon solar cells using in situ fabricated perovskite quantum dots as luminescence downshifting materials

- Structural and optical impacts of AlGaN undershells on coaxial GaInN/GaN multiple-quantum-shells nanowires

- Surface-plasmon-polariton-driven narrow-linewidth magneto-optics in Ni nanodisk arrays

- Broadband multi-wavelength optical sensing based on photothermal effect of 2D MXene films

- Tailoring the spatial localization of bound state in the continuum in plasmonic-dielectric hybrid system

- High-speed multiplane structured illumination microscopy of living cells using an image-splitting prism

- Si metasurface half-wave plates demonstrated on a 12-inch CMOS platform

- Implementation of on-chip multi-channel focusing wavelength demultiplexer with regularized digital metamaterials

- Imprinted plasmonic measuring nanocylinders for nanoscale volumes of materials

- Hydrophobin HGFI–based fibre-optic biosensor for detection of antigen–antibody interaction

- Enhanced terahertz emission from imprinted halide perovskite nanostructures

- Realization of complex conjugate media using non-PT-symmetric photonic crystals

- Selective tuning of optical modes in a silicon comb-like photonic crystal cavity

- Phase-coupled simultaneous coherent perfect absorption and controllable hot-electron photodetection in Schottky junction metamaterial

- Landau quantisation of photonic spin Hall effect in monolayer black phosphorus

- Near-field spectrum retrieving through non-degenerate coupling emission

Articles in the same Issue

- Reviews

- Optical binding of nanoparticles

- Recent advances in nano-photonic techniques for pharmaceutical drug monitoring with emphasis on Raman spectroscopy

- Optically responsive delivery platforms: from the design considerations to biomedical applications

- Research Articles

- Beyond dipolar Huygens’ metasurfaces for full-phase coverage and unity transmittance

- Bound states in the continuum and strong phase resonances in integrated Gires-Tournois interferometer

- Improving the efficiency of silicon solar cells using in situ fabricated perovskite quantum dots as luminescence downshifting materials

- Structural and optical impacts of AlGaN undershells on coaxial GaInN/GaN multiple-quantum-shells nanowires

- Surface-plasmon-polariton-driven narrow-linewidth magneto-optics in Ni nanodisk arrays

- Broadband multi-wavelength optical sensing based on photothermal effect of 2D MXene films

- Tailoring the spatial localization of bound state in the continuum in plasmonic-dielectric hybrid system

- High-speed multiplane structured illumination microscopy of living cells using an image-splitting prism

- Si metasurface half-wave plates demonstrated on a 12-inch CMOS platform

- Implementation of on-chip multi-channel focusing wavelength demultiplexer with regularized digital metamaterials

- Imprinted plasmonic measuring nanocylinders for nanoscale volumes of materials

- Hydrophobin HGFI–based fibre-optic biosensor for detection of antigen–antibody interaction

- Enhanced terahertz emission from imprinted halide perovskite nanostructures

- Realization of complex conjugate media using non-PT-symmetric photonic crystals

- Selective tuning of optical modes in a silicon comb-like photonic crystal cavity

- Phase-coupled simultaneous coherent perfect absorption and controllable hot-electron photodetection in Schottky junction metamaterial

- Landau quantisation of photonic spin Hall effect in monolayer black phosphorus

- Near-field spectrum retrieving through non-degenerate coupling emission